Nava Atlas's Blog, page 90

March 10, 2018

Madeleine L’Engle: “A Wrinkle in Time was Almost Never Published”

I would challenge anyone to come up with a story that better illustrates the fine line between rejection and acceptance than Madeleine L’Engle’s: “A Wrinkle in Time was almost never published,” she wrote. “You can’t name a major publisher who didn’t reject it. When we’d run through forty-odd publishers, my agent sent it back. We gave up.” Most editors thought it too dark and complex for children.

After some time, L’Engle made contact with John Farrar of Farrar Straus Giroux through a friend of her mother’s, and the rest is publishing history. Published in 1962, A Wrinkle in Time is still in print with millions of copies having been sold. It has the distinction of having won some of the most prestigious publishing awards, as well as being one of the most frequently banned books of all time.

Translating A Wrinkle in Time to film

The first attempt to translate Wrinkle into film was in 2003, when a Canadian film company produced what was intended to be a TV mini-series. Instead, the episodes were combined into a three-hour block and aired on ABC-TV. Though previously it had won Best Feature Film in the Toronto Film Festival, the televised version wasn’t well received by critics — or the author. L’Engle said in an interview: “I have glimpsed it … I expected it to be bad, and it is.”

The big-budget, star-studded 2018 film version of A Wrinkle in Time has also received its share of mixed reviews. CNET wrote that for all the visual spectacle, it lacks “the sense of wonder and discovery that should accompany such a film. The movie is supposed to be an epic adventure, but instead it feels like a taxi ride to somewhere with beautiful scenery in between.” It’s interesting to ponder what the author would have thought of the Hollywood Blockbuster treatment of her quirky, groundbreaking sci-fi/fantasy novel for kids.

Scene from A Wrinkle in Time, 2018

No matter what the budget is or how nobel the intentions, it’s so rare that a film really captures the spirit of a classic novel that the author intended. It does happen, but those instances are few and far between. Still, it’s very cool that a novel that was nearly relegated to oblivion still continues to resonate. The moral of this story, though is … read the book. Or at least, read it before you see the film, so that you can hold the source material as the author intended, close to your heart.

Here are some passages from her memoir, A Circle of Quiet (1972), in which she recalls the bitter years when A Wrinkle in Timeas well as her other books were met with nothing but rejection:

Madeleine L’Engle on Keeping the Faith

“When my book was rejected by publisher after publisher, I cried out in my journal. I wrote, after an early rejection, ‘X turned down Wrinkle, turned it down with one hand while saying that he loved it, but didn’t quite dare do it, as it isn’t really classifiable, and am wondering if I’ll have to go through the usual hell with this that I seem to go through with everything that I write. But this book I’m sure of…'”

“… I was, perhaps, out of joint with time. Two of my books for children were rejected for reasons which would be considered absurd today. Publisher after publisher turned down Meet the Austins because it begins with a death. Publisher after publisher turned down A Wrinkle in Time because it deals overtly with the problem of evil, and it was too difficult for children, and was it a children’s or adult’ book, anyhow?

My adult novels were rejected, too. A Winter’s Love was too moral: the married protagonist refuses an affair because of the strength of her responsibility towards marriage. Then, shortly before my fortieth birthday, both Meet the Austins and an adult novel, The Lost Innocent, had been in publishing houses long enough to get my hopes up …

On my birthday, I was, as usual, out in the Tower working on a book. The children were in school. My husband was at work and would be getting the mail. He called, saying, ‘I’m sorry to have to tell you this on your birthday, but you’d never trust me again if I kept it from you. [Such-and such editor] has rejected The Lost Innocent.‘

This seemed like an obvious sign from heaven. I should stop trying to write. All during the decade of my thirties (the 1950s) I went through spasms of guilt because I spent so much time writing, because I wasn’t like a good New England housewife and mother … So the rejection on the fortieth birthday seemed an unmistakable command: Stop this foolishness and learn to make cherry pie.”

More about A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle

Paving the way for more complex children’s literature

Fortunately, L’Engle didn’t “stop the foolishness;” she kept writing, of course, and with her persistence and belief in her power to tell stories, finally found that one editor who was willing to take the chance on her quirky, profound novel

Might L’Engle’s books have paved the way for the acceptance of children’s literature that’s more complex, even dark? Have these kinds of books become more palatable to publishers? That seems to be the case. Evidently, children have long proven themselves ready for these themes, borne out most abundantly by the unparalleled success of the Harry Potter series.

Much has been made of the initial rejections of the first installment of J.K. Rowling’s blockbuster series, but hers were the more usual numbers of rejections before an agent, then a publisher recognized the talent and passion of this then-unknown writer. Her path wasn’t smooth, to be sure, but it may have been much rougher had it not been for authors like Madeleine L’Engle who came before her.

After A Wrinkle in Time came out and was an immediate smash success, the editors who has turned it down were filled with regrets: “After the unexpected success of Wrinkle,” L’Engle recalled, “I was invited to quite a lot of literary bashes and was frequently approached by publishers who had rejected it. ‘I wish you had sent the book to us.’ I could usually respond, ‘But I did.'”

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle on Amazon

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Madeleine L’Engle: “A Wrinkle in Time was Almost Never Published” appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 7, 2018

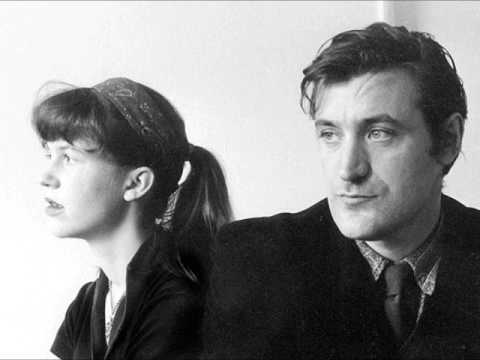

The Tragic Relationship of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes

Sylvia Plath (1932 – 1963) was a gifted writer of poetry and fiction whose life ended all too young by suicide. Attractive, smart, and talented, she seemed to have what it took to succeed. But it was during her years at Smith College, where she was well-liked and academically adept, that she attempted her first suicide. Journal entries in her diary later revealed how much Plath struggled from that time onward, up until her suicide.

Many of the truths behind her final years were exposed after her death, discovered in letters revealing the dark secrets of her tragic relationship with Ted Hughes. Her body of poetic work, much of it published posthumously, also reveals much about her state of mind during the brief journey of her adult life.

The beginning

Plath first met poet Ted Hughes on February 25, 1956, at a party in Cambridge, England. In a 1961 BBC interview, Plath describes how she met him:

“I happened to be at Cambridge. I was sent there by the [US] government on a government grant. And I’d read some of Ted’s poems in this magazine and I was very impressed and I wanted to meet him. I went to this little celebration and that’s actually where we met… Then we saw a great deal of each other. Ted came back to Cambridge and suddenly we found ourselves getting married a few months later… We kept writing poems to each other. Then it just grew out of that, I guess, a feeling that we both were writing so much and having such a fine time doing it, we decided that this should keep on.”

The couple married on June 16, 1956, and honeymooned in Benidorm, Spain. The following year, Plath and Hughes moved to the Massachusetts, where Plath taught at her alma mater, Smith College. It was a challenge for her to find the time and energy to write when she was teaching. By the end of 1959 after another move and extensive travel, the couple moved back to London.

The couple had their first daughter, Frieda, on April 1st, 1960. The next year, Plath miscarried their second child. It was later revealed in a letter to her therapist, that Plath wrote of Hughes beating her two days before the miscarriage. Several of her poems, including “Parliament Hill Fields,” address the loss. In 1962, their son Nicholas was born.

And this is when things got complicated.

See also: 10 of Sylvia Plath’s Best Loved Poems

Hughes’ affair

In May of 1962 Assia Wevill and her third husband, Canadian poet David Wevill, were invited to spend a weekend with Plath and Hughes, who were then living in the village of North Tawton in Devon, England. It was on that weekend, as Hughes later wrote in a poem, that “The dreamer in me fell in love with her,” and a few short weeks later he begins his affair with Assia Wevill.

A few months after meeting Assia, Plath and Hughes took a holiday in Ireland. On the fourth day, Hughes disappeared to London to meet Wevill, with whom he embarked on a 10 day trip through Spain, the same place where Plath and Hughes had honeymooned. Upon his arrival back home, the marriage unraveled when he refused to end his affair with Wevill. Plath and Hughes separated in July of 1962. Just before and several times after, Plath attempted to end her life.

Plath lived in a flat with her children during the gloomy winter of 1962 – 1963, basically functioning as a single parent to her baby son and toddler daughter. As is well known, she committed suicide by gassing herself in her kitchen while her children slept soundly in a room nearby. The months between her discovery of Hughes’ affair and her death were remarkably productive, and much of the poetry she produced during this period was published posthumously.

Letters revealed

In 2017, a series of confidential letters from Plath to her psychiatrist, Dr. Ruth Barnhouse, came to light in which she alleged that Hughes was physically and psychologically abusive in the last years of their marriage.

The uncovered letters were written by Plath a week before her suicide. The discovery reignited flames that long engulfed one of the most famed and disastrous literary marriages.

The letters sent to Dr. Barnhouse (the inspiration for Dr. Nolan in Plath’s autobiographical novel The Bell Jar) are considered the only uncensored accounts of her last few months alive. At the same time, she was also producing some of her most enduring poetry, including the collection Ariel (posthumously published in 1965).

Through nine letters Plath reveals Hughes’ infidelity with Wevill. Also included in the collection are medical records from 1954, correspondence with Plath’s friends and interviews with Barnhouse about her therapy sessions with the poet. The archive came to light after an antiquarian bookseller put it up for sale for $875,000.

Plath’s writes her account of the physical abuse she endured shortly before miscarrying her second child in 1961, in a letter dated September 22, 1962 — the same month the couple separated. Several of Plath’s poems address her miscarriage, including Parliament Hill Fields: “Already your doll grip lets go.”

See also: Sylvia Plath’s Suicide Note: Death Knell, or Cry for Help?

Speculation and reaction

The relationship of Hughes and Assia Wevill was fraught and troubled. In a tragic twist of fate, the stresses of scrutiny over her continued relationship with Hughes, the disapproval of his family, and his continued infidelity took their toll on her. In March 1969, Assia Wevill dragged a bed into the kitchen of her Clapham flat, dissolved sleeping tablets in a glass of water and gave the drink to her daughter (generally believed to be Hughes’ child) before finishing the rest herself. Mirroring Plath’s suicide method, she then turned on the gas stove and got into bed with her daughter; they never woke up.

It took decades for Hughes to speak out about his relationship with Plath. The collection “Birthday Letters” (1998) was his response to the feminist critics who spoke out against Hughes over his treatment of Plath, especially in the 1970s. He even had “Murderer!” shouted at him during public readings.

In 1970 Hughes was remarried to Carol Hughes, with whom he remained until his death. In response to the letters that surfaced in 2017 claiming Hughes’ abuse toward Plath, Carol Hughes went on record to say,“The claims allegedly made by Sylvia Plath in unpublished letters to her former psychiatrist, suggesting that she was beaten by her husband, Ted Hughes, days before she miscarried their second child are as absurd as they are shocking to anyone who knew Ted well.”

Posthumously published

When Plath committed suicide, she was still married to Hughes, though the couple was separated. Thus, he inherited her literary estate. Much of Plath’s work was unpublished while she was alive, and Hughes decided to publish some of the collections she left behind.

In 1965 he released Ariel, a collection of poems Plath wrote expressing her battle with the darkness of depression, and of her relationship with Hughes. He was accused of altering the order of the poems in an attempt to save his reputation. Through the 1970s Hughes continued to release Plath’s poems, but was met with criticism over his selections and decisions of what works to release.

The couple’s son, Nicholas followed his mother’s tragic path, committing suicide on March 16th, 2009.

Introspective Quotes by Sylvia Plath

See more on Plath’s released letters:

The Letters of Sylvia Plath Volume 1 review – why Plath can’t win in a world of male privilege

Ted Hughes’ widow criticises ‘offensive’ biography

‘Dearest Teddy’: Sylvia Plath’s love letters to Ted Hughes published for the first time

Why Do We Struggle to Believe Ted Hughes Abused Sylvia Plath?

Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes’s daughter Frieda: Why I’m becoming a counsellor

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Tragic Relationship of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Quotes From Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston (1891 – 1960) was a memoirist, novelist, and folklorist who was an active member of the Harlem Renaissance literary movement. She was the first black student to study at Barnard college, and later in her career received a Guggenheim Fellowship. Her most influential works include Their Eyes Were Watching God, Tell My Horse, Mules and Men, and Moses, Man of the Mountain.

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) is Hurston’s best known work. Always somewhat controversial, discussions and perceptions of the novel have evolved over the decades since it was first published. The story follows Janie Crawford as she matures from a voiceless teenager to a woman with greater control over her own destiny. The book was largely forgotten by the time of Hurston’s death in 1960, but re-emerged as a classic of twentieth-century literature and a staple in women’s studies courses. Here’s a sampling of quotes from Their Eyes Were Watching God:

“There are years that ask questions and years that answer.”

“Some people could look at a mud puddle and see an ocean with ships.”

“Love is like the sea. It’s a moving thing, but still and all, it takes its shape from the shore it meets, and it’s different with every shore.”

“All gods who receive homage are cruel. All gods dispense suffering without reason. Otherwise they would not be worshipped. Through indiscriminate suffering men know fear and fear is the most divine emotion. It is the stones for altars and the beginning of wisdom. Half gods are worshipped in wine and flowers. Real gods require blood.”

“There is a basin in the mind where words float around on thought and thought on sound and sight. Then there is a depth of thought untouched by words, and deeper still a gulf of formless feelings untouched by thought.”

“She had an inside and an outside now and suddenly she knew how not to mix them.”

You might also like: Zora Neale Hurston Quotes and Life Lessons

“She didn’t read books so she didn’t know that she was the world and the heavens boiled down to a drop.”

“So she sat on the porch and watched the moon rise. Soon its amber fluid was drenching the earth, and quenching the thirst of the day.”

“Here was peace. She pulled in her horizon like a great fish-net. Pulled it from around the waist of the world and draped it over her shoulder. So much of life in its meshes! She called in her soul to come and see.”

“Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board. For some they come in with the tide. For others they sail forever on the horizon, never out of sight, never landing until the Watcher turns his eyes away in resignation, his dreams mocked to death by Time.”

“It was not death she feared. It was misunderstanding.”

“There is two things everybody got to find out for theirselves. They got to find out about love and they got to find out about living.”

See also: Zora Neale Hurston: Books, Publishing, and Publishers

“She had waited all her life for something, and it had killed her when it found her.”

“The familiar people and things had failed her so she hung over the gate and looked up the road towards way off. She knew now that marriage did not make love. Janie’s first dream was dead, so she became a woman.”

“The morning air was like a new dress. That made her feel the apron tied around her waist. She flung it on a low bush beside the road and walked on, picking flowers and making a bouquet…From now on until death she was going to have flower dust and springtime sprinkled over everything.”

“An envious heart makes a treacherous ear. They done ‘heard’ bout just what they hope done happened.”

“If you’re silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.”

“Love makes your soul crawl out from its hiding place.”

“No hour is ever eternity, but it has its right to weep.”

“But any man who walks in the way of power and property is bound to meet hate.”

“Janie saw her life like a great tree in leaf with the things suffered, things enjoyed, things done and undone. Dawn and doom was in the branches.”

“Of course he wasn’t dead. He could never be dead until she herself had finished feeling and thinking. The kiss of his memory made pictures of love and light against the wall. Here was peace. She pulled in her horizon like a great fish-net. Pulled it from around the waist of the world and draped it over her shoulder. So much of life in its meshes! She called in her soul to come and see.”

“She was a rut in the road. Plenty of life beneath the surface but it was kept beaten down by the wheels”

You might like: Two 1937 reviews of

Their Eyes Were Watching God Review

“The wind came back with triple fury, and put out the light for the last time. They sat in company with the others in other shanties, their eyes straining against crude walls and their souls asking if He meant to measure their puny might against His. They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.”

“She was stretched on her back beneath the pear tree soaking in the alto chant of the visiting bees, the gold of the sun and the panting breath of the breeze when the inaudible voice of it all came to her. She saw a dust-bearing bee sink into the sanctum of a bloom; the thousand sister-calyxes arch to meet the love embrace and the ecstatic shiver of the tree from root to tiniest branch creaming in every blossom and frothing with delight. So this was a marriage!”

“He drifted off into sleep and Janie looked down on him and felt a self-crushing love. So her soul crawled out from its hiding place.”

“Somebody wanted her to play. Somebody thought it natural for her to play. That was even nice. She looked him over and got little thrills from every one of his good points.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes From Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 6, 2018

The Heart of a Woman by Maya Angelou

Marguerite Annie Johnson Angelou (1928 – 2014), widely known as Maya Angelou, was an American author, actress, screenwriter, dancer, poet, and civil rights activist. This celebrated, inspiring, and prolific woman is best known for a multitude of accomplishments.

During her lifetime, she published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, and several books of poetry. The Heart of a Woman is the fourth book in her seven part series of autobiographies. She has received dozens of awards and more than thirty honorary doctoral degrees over the course of her professional life that spanned over 50 years long.

Following is a description of The Heart of a Woman, from the 1981 Random House edition: The Heart of a Woman is the fourth volume of Maya Angelou’s autobiography, which began so auspiciously with I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings. She is now clearly embarked on one of the more significant and important personal narratives of our time.

In The Heart of a Woman she leaves California with her son, Guy, to go to New York. There she enters the society and world of black artists and writers. Not since her childhood has she lived in an almost black environment, and she is surprised at the obsession her new friends have with the white world around them.

See also: 10 Fascinating Facts About Maya Angelou

She stays for awhile with John and Grace Killens and begins to read her writing at the Harlem Writers Guild. She continues to sing, most notably at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem, but more and more she begins to take part in the struggle black Americans are making for their rightful place in the world. She helps organize a benefit cabaret for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and then is appointed Martin Luther King’s Northern Coordinator.

Shortly after that, through her friend Abbey Lincoln, she takes one of the lead parts in Genet’s The Black (it was a remarkable cast, including Godfrey Cambridge, Roscoe Lee Brown, James Earl Jones, Cicely Tyson, Raymond St. Jacques, and Lou Gossett), and even writes music for the production.

In the meantime her personal life has taken a tempestuous turn. She has left the New York bail bondsman she was intending to marry and has fallen in love with a South African freedom fighter named Vusumzi Make, who sweeps her off her feet and eventually takes her to London and then to Cairo, where, as her marriage begins to break up, she becomes the first female editor of the English-language magazine.

The Heart of a Woman is filled with unforgettable vignettes of famous characters, from Billie Holiday to Malcolm X, but perhaps most important of all is the story of Maya Angelou’s relationship with her son. Because this book chronicles, finally, the joys and burdens of a black mother in America and how the son she had cherished so intensely and worked for so devotedly finally grows to be a man.

The Heart of a Woman by Maya Angelou on Amazon

The complete list of Maya Angelou’s seven part autobiography series:

I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings (1969)

Gather Together In My Name (1974)

Singin’ and Swingin’ and Gettin’ Merry Like Christmas (1976)

The Heart of A Woman (1981)

All God’s Children Need Traveling Shoes (1986)

A Song Flung Up to Heaven (2002)

Mom & Me & Mom (2013)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Heart of a Woman by Maya Angelou appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 5, 2018

The Little Book of Feminist Saints by Julia Pierpont & Manjit Thapp

The Little Book of Feminist Saints by Julia Pierpont & Manjit Thapp is an inspiring, beautifully illustrated collection that honors one hundred exceptional women throughout history and around the world. It’s being published just in time for International Women’s Day on March 8, 2018.

In this luminous volume, New York Times bestselling writer Julia Pierpont and British artist Manjit Thapp match short, vibrant and surprising biographies with stunning full-color portraits of secular female ‘saints’: champions of strength and progress.

These women broke ground, broke ceilings, and broke molds. Reaching all around the world, from 630 B.C. to the present day, each woman is assigned their own special day so that readers can open any page to find daily inspiration and lasting delight. The feminist ‘saints’ include, among others:

Maya Angelou

Jane Austen

Ruby Bridges

Rachel Carson

Shirley Chisholm

Hillary Clinton

Marie Curie & Irene Joliot Curie

Isadora Duncan

Amelia Earhart

Artemisia Gentileschi

Grace Hopper

Dolores Huerta

Frida Kahlo

Billie Jean King

Audre Lorde

Wilma Mankiller

Toni Morrison

Michelle Obama

Sandra Day O’Connor

Sally Ride

Eleanor Roosevelt

Margaret Sanger

Sappho

Nina Simone

Gloria Steinem

Kanno Sugako

Harriet Tubman

Mae West

Virginia Woolf

Malala Yousafzai

Here’s an excerpt from The Little Book of Feminist Saints:

Maya Angelou

B. 1928, U.S.

MATRON SAINT OF STORYTELLERS

Feast Day: April 4

“In times of strife and extreme stress, I was likely to retreat to mutism. Mutism is so addictive. And I don’t think its powers ever go away.”

A surprising admission for a woman who, by age forty, had lived in Egypt, in Ghana, and all around the United States; who’d worked as a professional dancer, a prostitute, an activist, a singer, a lecturer; and who would become a prolific writer.

Severe childhood trauma triggered Maya Angelou’s mutism at the age of eight: she’d been raped, and after her testimony in court, her rapist had been violently murdered. Her muteness lasted for nearly five years before lifting—but its dark appeal never left her.

“It’s always there saying, ‘You can always come back to me. You have nothing to do—just stop talking.” Angelou resisted the urge.

At forty-one, she published her first and best-known book, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, which tells the story of that early trauma. In plays, in poems, in autobiographies and spoken-word albums and children’s books, she would tell stories for the rest of her life.

“The writer has to take the most used, most familiar objects—nouns, pronouns, verbs, adverbs—ball them together and make them bounce, turn them a certain way and make people get into a romantic mood; and another way, into a bellicose mood,” she said at age seventy-five. “I’m most happy to be a writer.”

The Little Book of Feminist Saints is available on Amazon U.S. and Amazon U.K., and wherever books are sold.

About the author and illustrator

Julia Pierpont (Author) is the author of the New York Times bestseller Among the Ten Thousand Things, winner of the Prix Fitzgerald in France. She is a graduate of Barnard College and the MFA program at New York University. Her writing has appeared in the Guardian, New Yorker, New York Times Book Review and Guernica. She lives and teaches in New York.

Manjit Thapp (Illustrator) is an illustrator from the United Kingdom. She graduated with a BA in illustration from Camberwell College of Arts in 2016. Her illustrations combine both traditional and digital media, and her work has been featured by Instagram, Dazed, Vogue India and Wonderland Magazine. Find out more https://www.manjitthapp.co.uk/about/ or on Instagram @manjitthapp.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Little Book of Feminist Saints by Julia Pierpont & Manjit Thapp appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 4, 2018

Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American author, poet, and art collector. She’s considered one of the most significant writers of the early twentieth century. Though some consider her writing incoherent or absurd, others view it as a singular voice.

Born into a well-to-do family Jewish family in Pennsylvania, Stein went to college at Radcliffe and then studied medicine for four years at Johns Hopkins University.

Stein lived most of her adult life in Paris, where she moved in 1903. She and her brother Leo Stein amassed an important art collection; the two lived together in Paris for some years, but after she met her life partner, Alice B. Toklas, a rift grew between the sibling. Leo resented Toklas and called her “a kind of abnormal vampire.”

“The Lost Generation”

Stein met Alice B. Toklas on September 8, 1907, the day after the latte arrived in Paris from her native San Francisco. Their apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus became an intellectual hub. It served as a salon, where Stein famously championed notable artists before and after they became famous, including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, and Juan Gris.

She coined the term “The Lost Generation” to describe the expatriate writers of the 1920s, notably, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. Other writers who frequented rue de Fleurus included Thornton Wilder, Sherwood Anderson, and James Joyce. Stein, formidable as she was, served as a nurturing, encouraging figure.

Her relationship with Hemingway was complicated. He helped her type one of her most important works, The Making of Americans, which was finally published in 1925 after having been written some twenty years earlier. On the other hand, in his posthumous memoir of his Paris years, Hemingway maligns her and her relationship with Toklas.

From most accounts, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas were a most devoted couple. Toklas was a legendary cook, and played the wifely role as Stein held court with the writers and artists who frequented their salon. The two remained together until Stein’s death, after which Toklas took upon herself the role of widow, doing what she could to preserve her life partner’s legacy.

You might also like: Gertrude Stein Quotes to Perplex and Delight

Experiments in poetry and prose

Her poems were unlike any others — each almost like a piece of abstract art to experience throughout the senses. Stein’s most popular work was The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, which is written as though through Alice’s point of view. Aside from poetry and novels, Stein also wrote plays, operas, and gave many lectures.

Her experiments in prose, which may have originated with automatic writings, were highly influential. According to The Penguin Companion to American Literature:

These experiments may be seen in various stages of development in Three Lives (1909), Tender Buttons (1914), and Geography and Plays (1922). These books gave her a reputations for extreme unintelligibility, and she became in the eyes of many the leader of the avant garde in American writing.

Her syntactical manipulations perhaps blinded her first readers to the homespun quality of her feelings about place and country — she was the only modernist who was always ‘patriotic’…

The really radical departure in her stylistic experimentation was her attempt to develop a ‘cubist’ literature, a prose independent of meaningful associations, relying merely on sound-orchestration.

Stein and Toklas

The Making of Americans and The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas

The Making of Americans: Being a History of a Family’s Progress (1925) is her most weighty work, It this 900-plus-page modernist novel she presents a history of American life in excruciating detail through the accounts of the fictional Hersland and Dehning family. She disrupts the novelistic space with meditations on the process of writing.

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), which was written by Stein and not Toklas, was less experimental and in fact helped Stein gain a wider readership. Once again, from The Penguin Guide to American Literature:

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, combined with her lecture tour of America in 1934 — out of which came her Lectures in America (1935) — and her ‘mothering’ of American G.I.s during World War II, brought her into public prominence. Her writing took a turn for the lucid, and her naïve posture — which many had thought drollery — combined with a new lucidity, made her a lost leader in the eyes of … aesthetic intellectuals.

Last years

She either thought quite highly of herself and her genius, or else was pulling the wool over everyone’s eyes — with the formidable Gertrude Stein, it was often hard to tell. She wrote, ostensibly writing of herself, “It takes a lot of time to be a genius. You have to sit around so much, doing nothing, really doing nothing.”

Gertrude Stein seemed to enjoy life more than ever in her last hears. Her only children’s book, The World is Round (1939) is a play off of her most famous poetic lines, “A rose is a rose is a rose.”

Also among her last works were Paris France (1940); Picasso (1939), in which her lifelong appreciation of art is crystallized; and Wars I Have Seen (1945). For those just getting acquainted with her work, Selected Writings of Gertrude Stein edited by Carl Van Vechten (1946, 1962) is a good place to start.

Stein died in Paris on July 27, 1946 at the age of 72 from complications from stomach cancer surgery after surgery. She is buried in Paris, in the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

More about Gertrude Stein on this site

Gertrude Stein Quotes to Perplex and Delight

10 Slightly Absurd Quotes by Gertrude Stein

Major Works

Three Lives (1909)

Tender Buttons (1914)

The Making of Americans (1925)

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933)

Everybody’s Autobiography (1938)

Picasso (1939)

Paris France (1940)

Wars I have Seen (1945)

Ida

The World is Round (1909)

Biographies about Gertrude Stein

Gertrude and Alice by Diana Souhami

Stein: In Words and Pictures by Renate Stendhal

Charmed Circle: Gertrude Stein and Her Circle by James R. Mellow

More Information

Wikipedia

The Gertrude Stein Repertory Theatre

Gertrude Stein Society

Reader discussion of Stein’s books

Stein’s book page on Amazon

Articles, News, Etc.

Jewish Hall of Fame

The Material Archive of Stein & Toklas

From Stein to Warhol: Dramatic Readings of Famous Rejection Letters

Stein’s Brow-Furrowing Children’s Book Gets a Royal Reissue

Stein Visits the Poe Museum

Of Genius, Cable Cars and Duck Shoes

Stein in Love

Expat, Art Collector, Writer, and Pure Genius

Stein and Cultural Femicide

Visit Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers – Yale University, New Haven, CT

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Gertrude Stein appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 3, 2018

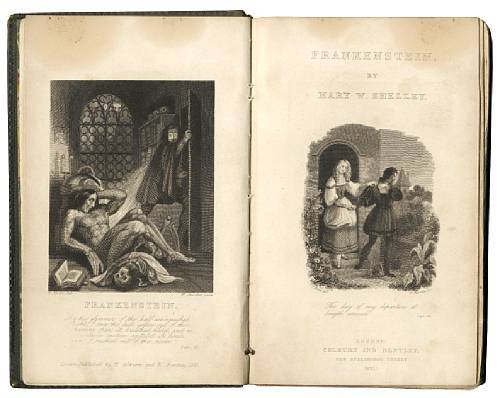

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley: A Synopsis and View from the 19th Century

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797 – 1851), the British author, is best known for the classic thriller, Frankenstein. In the summer of 1814, Mary, at age 17, ran off to Europe with the married poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. There she joined his literary circle, which included Lord Byron. The events that inspired the creation of the tale took place during the couple’s sojourn in Italy. It was published in 1818, when Mary was barely 21 years old.

You can read in Mary Shelley’s own words how she, a sheltered young woman, came to write one of the most haunting tales of all time. For a detailed synopsis of Frankenstein, this excerpt, adapted from Mrs. Shelley (1890) by Lucy Madox Brown Rossetti, provides an excellent outline of the plot, with a late 19th-century perspective:

Frankenstein begins with a series of letters

That a work by a girl of nineteen should have held its place in romantic literature so long is no small tribute to its merit; this work, wrought under the influence of Lord Byron and Percy Shelley, and conceived after drinking in their enthralling conversation, is not unworthy of its origin.

The story of Frankenstein begins with a series of letters of a young man, Robert Walton, writing to his sister, Mrs. Saville in England, from St. Petersburg, where he is about to embark on a voyage in search of the North Pole. He is bent on discovering the secret of the magnet, and is deluded with the hope of a never absent sun.

Encountering a gigantic being

When advanced some distance towards his longed-for goal, Walton writes of a most strange adventure which befalls them in the midst of the ice regions—a gigantic being, of human shape, being drawn over the ice in a sledge by dogs. Not many hours after this strange sight a fresh discovery was made of another man in another sledge, with only one living dog to it: this time the man was seen to be a European, whom the sailors tried to persuade to enter their ship.

A skeletal and bedraggled stranger

On seeing Walton, the stranger, speaking English, asked whither they were bound before he would consent to enter the ship. This naturally caused intense excitement, as the man, reduced to a skeleton, seemed to have but a short time to live. However, on hearing that the vessel was bound northwards, he consented to enter, and with great care he was restored for the time. In answer to an inquiry as to his object … he replied, “To seek one who fled from me.” An affection springs up and increases between Walton and the stranger, till the latter promises to tell his sad and strange story, which he had hitherto intended should die with him.

See also: How Mary Shelley Came to Write Frankenstein (1818)

The story told by the dying man

This commencement leads to the story being told in the form of a long narrative by the dying man, whose name is Victor Frankenstein. The stranger describes himself as of a Genovese family of high distinction, and gives an interesting account of his father and juvenile surroundings, including a playfellow, Elizabeth Lavenga, whom we encounter much later in his history.

All his studies are pursued with zest, till coming upon the works of Cornelius Agrippa he is led with enthusiasm into the ideas of experimental philosophy; a passing remark of “trash” from his father, who does not explain the difference between past and modern science, is not enough to deter him and prevent the fatal consequence of the study he persists in, and thus a pupil of Albertus Magnus appears in the eighteenth century. The effects of a thunderstorm, described from those Mary had recently witnessed, decided him in his resolution, for electricity now was the aim of his research.

After having passed his youth in a happy Swiss home with his parents and dear friends, on the death of his loved mother he starts for the University of Ingolstadt. Here he is rebuked by the professors for his useless studies, until one, Mr. Waldeman, sympathises with him, and explains how Cornelius Agrippa and others, although their studies did not bring the immediate fruit they expected, nevertheless helped on science in other directions, and he advises Frankenstein to pursue his studies in natural philosophy, including mathematics.

Discovering the principle of life

The upshot of this advice is that two years are spent in intense study and thought. He is contemplating a visit to his home, when, making some fresh experiment, he finds that he has discovered the principle of life; this so overcomes him for a time that, oblivious of all else, he is bent on making use of his discovery. He determines to create a being superior to man, so that future generations shall bless him.

In the first place, by the help of chemistry, he has to construct the form which is to be animated. A grave has to be ransacked in the attempt, and Frankenstein describes with loathing some of the details of his work, and shows the danger of overstraining the mind in any one direction—how the virtuous become vicious, and how virtue itself, carried to excess, lapses into vice.

The form is created in nervous fear and fever. Frankenstein being the ideal scientist, devoid of all feeling for art, without any ideal of proportion or beauty, reaches the point where he considers nothing but the infusion of life necessary. All is ready, and in the first hour of the morning he applies his fatal discovery.

The monster is animated

Breath is given, the limbs move, the eyes open, and the colossal being or monster, as he is henceforth called, becomes animated; though copied from statues, its fearful size, its terrible complexion and drawn skin, scarcely concealing arteries and muscles beneath, add to the horror of the expression. Overwhelmed by disgust, his creator can only rush from the room, and finally falls exhausted on his bed, only to wake to find his monster grinning at him. [editor’s note: keep in mind that Victor Frankenstein is the scientist; we’ve come to call the monster by the name Frankenstein, but he’s technically Frankenstein’s monster or creature]

Frankenstein hurries on, but coming across his old friend Henri Clerval at the stage coach, he recalls to mind his father, Elizabeth, his former life and friends. He returns to his rooms with his friend. Reaching his door, he trembles, but opening it, finds himself delivered from his self-created fiend. His frenzy of delight being attributed to madness from overwork, Clerval induces Frankenstein to leave his studies, and, finally (after he had for months endured a terrible illness), to accompany him to his native village.

Mysterious death of Victor Frankenstein’s young brother

Various delays occurring, they are detained too late in the year to pass the dangerous roads on their way home. Health and peace of mind returning to some decree, Frankenstein is about to proceed on his journey homewards, when a letter arrives from his father with the fatal news of the mysterious death of his young brother.

This event hastens still further his return, and gives a renewed gloomy turn to his mind; not only is his loved little brother dead, but the extraordinary event points to some unknown power. From this time Frankenstein’s life is agony. One after another, all whom he loves fall victims to the demon he has created; he is never safe from his presence; in a storm on the Alps he encounters him; in the fearful murders which annihilate his family he always recognizes his hand.

The monster seeks a truce

On one occasion his creation wished to have a truce and to come to terms with his creator. This, after his most fearful treachery had caused the innocent to be sentenced as the perpetrator of his fearful deeds. On meeting Frankenstein he recounts the most pathetic story of his falling away from sympathy with humanity: how, after saving the life of a girl from drowning, he is shot by a young man who rushes up and rescues her from him.

He became the unknown benefactor of a family for some period of time by doing the hard work of the household while they slept. Having taking refuge in a hovel adjoining a corner of their cottage, he hears their pathetic and romantic story, and also learns the language and ways of men; but on his wishing to make their acquaintance the family are so horrified at his appearance that the women faint, the men drive him off with blows, and the whole family leave a neighborhood, the scene of such an apparition.

After these experiences he retaliates, till meeting Frankenstein he proposes these terms: that Frankenstein shall create another being as repulsive as himself to be his companion—in fact, he desires a wife as hideous as he is. These were the conditions, and the lives of all those whom Frankenstein held most dear were in the balance; he hesitated long, but finally consented.

You might also like:

Quotes from Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

For the love of Elizabeth

Everything now had to be put aside to carry out this fearful task — his love of Elizabeth, his father’s entreaties that he should marry her, his hopes, his ambitions, go for nothing. To save those who remain, he must devote himself to his work. To carry out his aim he expresses a wish to visit England, and, with his friend Clerval, descends the Rhine.

After passing London and Oxford and various places of interest, he expresses a desire to be left for a time in solitude, and selects a remote island of the Orkneys, where an uninhabited hut answers the purpose of his laboratory. Here he works unmolested till his fearful task is nearly accomplished, when a fear and loathing possess his soul at the possible result of this second achievement.

A companion for the monster?

Although the demon already created has sworn to abandon the haunts of man and to live in a desert country with his mate, what hold will there be over this second being with an individuality and will of its own? What might be the future consequences to humanity of the existence of such monsters? He forms a resolution to abandon his dreaded work, and at that moment it is confirmed by the sight of his monster grinning at him through the window of the hut in the moonlight.

The loss of a friend, a wife, a father

Not a moment is lost. He tears his just completed work limb from limb. The monster disappears in rage, only to return to threaten eternal revenge on him and his; but the time of weakness is passed; better encounter any evils that may be in store, even for those he loves, than leave a curse to humanity. From that time there is no truce. Clerval is murdered and Frankenstein is seized as the murderer, but respited for worse fate; he is married to Elizabeth, and she is strangled within a few hours.

When goaded to the verge of madness by all these events, and seeing his beloved father reduced to imbecility through their misfortunes, he can make no one believe his self-accusing story; and if they did, what would it avail to pursue a being who could scale the Alps, live among glaciers, and pass unfathomable seas?

Self-imposed torture

Only in sleep and dreams did Frankenstein find forgetfulness of his self-imposed torture, for he lived again with those he had loved; he endured life in his pursuit by imagining his waking hours to be a horrible dream and longing for the night, when sleep should bring him life.

When hopes of meeting his demon failed, some fresh trace would appear to lead him on through habited and uninhabited countries; he tracks him to the verge of the eternal ice, and even there procures a sledge from the wretched and horrified inhabitants of the last dwelling-place of men to pursue the monster, who, on a similar vehicle, had departed, to their delight.

The fatal scientific secret

Onwards, over the eternal ice they pass, the pursued and the pursuer, till consciousness is nearly lost, and Frankenstein is rescued by those to whom he now narrates his history; all except his fatal scientific secret, which is to die with him shortly, for the end cannot be far off.

The story is told; and the friend — for he feels the utmost sympathy with the tortures of Frankenstein — can only attempt to soothe his last days or hours, for he, too, feels the end must be near; but at this crisis in Frankenstein’s existence the expedition cannot proceed northward, for the crew mutiny to return.

Final battle with the monster

Frankenstein determines to proceed alone; but his strength is ebbing, and Walton foresees his early death. But this is not to pass quietly, for the demon is in no mood that his creator should escape unmolested from his grasp. Now the time is ripe, and, during a momentary absence, Walton is startled by fearful sounds, and then, in the cabin of his dying friend, a sight to appall the bravest; for the fiend is having the death struggle with him — then all is over.

Some last speeches of the demon to Walton are explanatory of his deed, and of his present intention of self-immolation, as he has now slaked his thirst to wreak vengeance for his existence. Then he disappears over the ice to accomplish this last task.

Surely there is enough weird imagination for the subject. Mary Shelley didn’t merely intend to depict the horror of such a monster, but evidently wished also to show what a being, with no naturally bad propensities, might sink to when under the influence of a false position.

Some weak points and incongruities

Some weak points, some incongruities, it would be unreasonable not to expect. Mary Shelley’s facility in writing was great, and having visited some of the most interesting places in the world, with some of the most interesting people, she is saved from the dreary dulness of the dull. Her ideas, also, though sometimes affected, are genuine, not the outcome of some fashionable foible to please a passing faith or superstition.

The last passage in the book is perhaps the weakest. It is scarcely the climax, but an anticlimax. The end of Frankenstein is well conceived, but that of the Demon fails. It is ridiculous to conceive anyone, demon or human, having ended his vengeance, fleeing over the ice to burn himself on a funeral pyre where no fuel could be found. Surely the tortures of the lowest pit of Dante’s Inferno might have sufficed for the occasion.

— adapted from Mrs. Shelley (1890) by Lucy Madox Brown Rossetti, Chapter VII, “Frankenstein”

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley on Amazon

More about Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Full text on Project Gutenberg

The Science of Life and Death in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

How Frankenstein’s Monster Became Human

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Frankenstein by Mary Shelley: A Synopsis and View from the 19th Century appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 2, 2018

Poetic Quotes from Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks

Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks is the only novel by this esteemed and much honored American poet. Published in 1951, its language is both spare and profound; it reads beautifully and poetically without seeming affected. It’s the story of a middle-class, mid-twentieth century black woman leading an ordinary, extraordinary life.

The story opens when Maud Martha is seven, observing the adults around her with wonder and bafflement. The story begins to grip as she enters adulthood, with its dating rituals, love, jealousy, marriage, motherhood, disappointment, loss, contentment and joy. It skims the surface of segregation and bias, and explores familial and neighborly bonds — all within a surprisingly short novel.

Here are selected quotes from Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks, a book that deserves to be rediscovered and treasured:

“What she liked was candy buttons, and books, and painted music (deep blue, or delicate silver) and the west sky; so altering, views from the steps of the back porch; and dandelions.”

“She was going to keep herself to herself. She did not want fame. She did not want to be a ‘star.’ To create — a role, a poem, picture, music, a rapture in stone: great. But not for her. What she wanted was to donate to the world a good Maud Martha. That was the offering, the bit of art, that could not come from any other.”

See also: Annie Allen by Gwendolyn Brooks

“For Russell lacked — what? He was — nice. He was fun to go out with. He did things, he said things, with a flourish. That was what he was. He was a flourish. He was a dazzling, long, and sleepily swishing flourish.”

“The name ‘New York’ glittered in front of her like the silver in the shops on Michigan Boulevard. It was silver, and it was sold, and it was remote: it was behind glads like the silver in the shops. It was not for her. Yet.”

“She toasted rye strips spread with pimento cheese and grated onion. She made cocoa. They ate, drank, and read together. She read Of Human Bondage. He read Sex in the Married Life. They were silent.”

“Could be, she mused, a marriage. The marriage shell, not the romance, or love, it might contain. A marriage, the plainer, the more plateaulike, the better. A marriage made up of Sunday papers and shoeless feet, baking powder biscuits, baby baths, and matinees and laundrymen, and potato plants in the kitchen window.”

“As he played, he kept a lookout for his mother, who usually arrived at seven, or near that hour. When he saw her rounding the corner, his little face underwent a transformation. His eyes lashed into brightness, his lips opened suddenly and became a smile, and his eyebrows climbed toward his hairline in relief and joy.”

A recent biography of Gwendolyn Brooks:

A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun

“Then she thought of her life. Decent childhood, happy Christmases; some shreds of romance, a marriage, pregnancy and the giving birth, her growing child, her experiments in sewing, her books, her conversations with her friends and enemies. ‘It hasn’t been bad,’ she thought.”

“On the whole, she felt, life was more comedy than tragedy. Nearly everything that happened had its comic element, not too well buried, either. Sooner or later one could find something to laugh at in almost every situation. That was what, in the last analysis, could keep folks from going mad.”

“But the sun was shining, and some of the people in the world had been left alive, and it was doubtful whether the ridiculousness of man would ever completely succeed in destroying the world — or, in fact, the basic equanimity of the least and commonest flower: for would its kind not come up again in the spring?”

RELATED POSTS

Gwendolyn Brooks Quotes on Writing and Life

5 Things to Love About Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks: The Poet as Working Mother

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Poetic Quotes from Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 1, 2018

Zora Neale Hurston Books, Quotes, and Other Writings

Zora Neale Hurston (January 7, 1891 – January 28, 1960) was an African-American novelist, memoirist, and folklorist. Born in Notasulga, Alabama, she was raised in Eatonville, Florida. With her determined intelligence and bold personality, she quickly became a big name in the Harlem Renaissance movement of the 1920s.

Having had a remarkable dual career as a writer (producing novels, short stories, plays, and essays) and as an anthropologist, it’s surprising that she died largely alone and forgotten. Yet how fortunate that her rediscovery, spearheaded by Alice Walker, reignited interest in her words and work. Here’s our Literary Ladies Guide to Zora Neale Hurston books, quotes, excerpts and other literary musings that can be found on our site.

Biography

Zora Neale Hurston

Books by Zora Neale Hurston

Note: This list of books is what’s on this site thus far; it will continue to grow.

Mules and Men (1935)

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

Tell My Horse (1938)

Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939)

I Love Myself When I Am Laughing (posthumous anthology, 1979)

Every Tongue Got to Confess (posthumous anthology, 2001)

Quotes and Other Excerpts

Zora Neale Hurston Quotes and Life Lessons

5 Quotes from “How it Feels to Be Colored Me”

“Crazy for This Democracy”

Quotes from Their Eyes Were Watching God

What White Publishers Won’t Print

Literary Musings

1934 Interview with Zora Neale Hurston

Fannie Hurst and Zora Neale Hurston, a Literary Friendship

Zora and Money Matters

Zora Neale Hurston’s “Sweat”: An Ecofeminist Master Class in Dialect and Symbolism

Zora on Books, Publishing, and Publishers

The post Zora Neale Hurston Books, Quotes, and Other Writings appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Jessie Redmon Fauset

Jessie Redmon Fauset (April 27, 1882 – April 30, 1961) was an American editor, poet, essayist, and novelist who was deeply involved with the Harlem Renaissance literary movement. Born in Camden County, New Jersey, and raised in Philadelphia, she was the daughter of a Methodist Episcopal minister. Her mother died when she was quite young.

Bright and studious, Jessie Fauset was the first African-American to graduate from the Philadelphia High School for Girls. A stellar student, she wished to continue her studies at Bryn Mawr College, but the institution got around admitting a black student by securing a scholarship for her at Cornell University. There she studied classical languages, and later earned a Master’s degree in French from the University of Pennsylvania.

After graduating in 1905, she wanted to teach in Philadelphia, but found the schools once again unwelcoming to an African-American woman.She taught French in Baltimore and Washington, D.C. schools.

Literary editor of The Crisis

In 1912, Fauset began to submit poems, stories, and essays to the NAACP’s magazine,The Crisis. The magazine’s chief editor, the eminent scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, must have been quite impressed with her work, as he wasn’t easy to please. She was still teaching at the time, but he convinced her to move to New York City and work as the magazine’s literary editor. She accepted and began this new chapter in her life in 1919.

She quickly proved to have a keen eye for talent, introducing readers to Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Jean Toomer, Claude McKay, and other notable authors and poets of the era. Fauset also oversaw the African-American children’s magazine Brownies’ Book, which was also under the auspices of the NAACP and Du Bois. Published monthly from 1920 to 1921, it aimed to instill pride in African-American children about their history and heritage.

She also contributed her own writings — editorials, poetry, short stories, translations from the French of writings by black authors from Europe and Africa, as well as accounts of her worldwide travels. Such was her influence that Fauset has long been considered one of the “midwives” of the Harlem Renaissance literary movement.

Fauset’s first novel, There is Confusion, was published in 1924, coming in the midst of her years as literary editor of The Crisis.

You might also like: 6 Poems by Jessie Redmon Fauset

A prolific poet and essayist

Fauset had the opportunity to publish her own work during her tenure atThe Crisis, which included editorials, stories, and poetry, all of which were appreciated by readers and literary critics. She edited and published the work of many noted Harlem Renaissance figures during her tenure at The Crisis; such was her influence that she’s considered one of the “midwives” of the Harlem Renaissance literary movement.

Some of the subject matter of her poetry was dark and rather grim, which can be sampled in 6 Poems by Jessie Redmon Fauset. “Oblivion” tells of a desire to lie in a deserted, neglected grave far from everyone and everything. Others, like “Dead Fires” and “La Vie C’est la Vie” seem rather fatalistic. It can be argued that the poems were an outlet for the frustration that this talented and capable woman had to endure because of race, but they allude to thwarted love and loneliness as well.

See also Literary Midwife: Jessie Redmon Fauset

More novels, and a return to teaching

After leaving The Crisis in 1926, Fauset wanted to work in publishing. Despite her experience and expertise, she was unable to find work because she was black. She even offered to work from home, but that didn’t help. She returned to teaching, and over the next several years wrote three more novels.

After 1924’s There is Confusion came Plum Bun (1928), The Chinaberry Tree (1931), and Comedy, American Style (1933). Up until the early 1920s, African-Americans were portrayed in stereotypical fashion by white authors in fiction. This inspired Fauset to write a novel portrayed black Americans in a middle-class settings. This was quite revolutionary at the time.

The educated, middle class characters in Fauset’s novels still experienced their share of prejudice, and like many works by black authors of the period, deal with themes of identity and passing.

Her novels received mixed reviews from African-American critics and colleagues. Some praised her for depictiing an aspect of black life that often didn’t see the light of print; others criticized her for an overly bourgeoise point of view. The Chinaberry Tree and Comedy: American Style were published in the depths of the Depression and weren’t as successful as her others. Her prolific pace of writing slowed considerably, and she virtually disappeared from literary circles.

Leaving the literary life to teach

Jessie Fauset seemed to have abandoned the literary life to pursue a teaching career. After her eight years at The Crisis, Fauset began to teach French at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx. She remained at the same school until her retirement in 1944.

You might also like Quotes by Jessie Redmon Fauset

A later-life marriage and legacy

Going back to 1929, Fauset was 47 years old when she married Herbert Harris, an insurance broker, in 1929. They remained together until his death in 1958. In her later years, she moved back to Philadelphia, where she died at age 79 in 1961.

A 2017 article in The New Yorker, The Forgotten Work of Jessie Redmon Fauset, quotes Cheryl A. Wall, author of Women of the Harlem Renaissance as saying, “I think we lose a bit of our literary history if we do not acknowledge the contributions of Jessie Fauset.” There’s ample evidence that Fauset felt the lack of appreciation for her contributions. Further, the article goes on to state, David Levering Lewis wrote of Fauset in When Harlem Was in Vogue: “There is no telling what she would have done had she been a man, given her first-rate mind and formidable efficiency at any task.”

Though she dropped out of the literary scene in the early 1930s, Jessie Fauset should be appreciated for her eye for talent, and supporting emerging voices from the Harlem Renaissance, many of whom are still read today. Though she may not have become as well known as some of those she nurtured and supported, it’s indisputable that she was one of the most important figures of the Harlem Renaissance.

More about Jessie Fauset on this site

6 Poems by Jessie Redmon Fauset

Literary Midwife: Jessie Redmon Fauset

Quotes by Jessie Redmon Fauset

Major works (novels)

There Is Confusion (1924)

Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral (1928)

The Chinaberry Tree (1931)

Comedy, American Style (1933)

Short stories, and essays (very select – her output of short works was enormous)

“Emmy” (1912):

“My House and a Glimpse of My Life Therein,” (1914)

“Double Trouble,” (1923)

“Impressions of the Second Pan-African Congress” (1921)

“What Europe Thought of the Pan-African Congress.” (1921)

More information

Wikipedia

Jessie Redmon Fauset entry at Perspectives in American Literature

Reader discussion of Fauset’s works on Goodreads

Jessie Redmon Fauset page on amazon.com

Articles, news, etc.

Fauset portrait by Laura Wheeler Waring at National Portrait Gallery

Jessie Fauset tells how to face despair

The Forgotten Work of Jessie Redmon Fauset

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Jessie Redmon Fauset appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.