Nava Atlas's Blog, page 94

January 31, 2018

6 Female Journalists of the World War II Era

These six female journalists of the World War II era, who reported on and documented from the field, pushed gender-defined barriers and fought for what they believed in, paving the way for women correspondents who came after them. They contributed to history with their groundbreaking work and bravery as journalists, photographers, and correspondents during World War II. At right, Ruth Baldwin Cowan’s WW II press credentials. See more about her later in this post.

Photo from TIME

Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971) breaks through the scene with many accomplishments of “firsts.” She is best known for being the first American female war correspondent, and the first foreign photographer permitted to take photos of the Soviet five-year plan. In 1929, Bourke-White became the associate editor and staff photographer for Fortune magazine and later in 1936 became the first female photojournalist for Life magazine.

As the first female war correspondent of World War II, in 1941 she traveled to the Soviet Union as Germany broke its pact of non-aggression and was the only foreign photographer in Moscow when German forces invaded. Her recognition is also noticed in both India and Pakistan for her photographs of Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi.

See the Classic Cameras Used by LIFE’s

First Female Staff Photographer

Dickey Chapelle (1919–1965) was an American photojournalist known for her work with National Geographic as a war correspondent from World War II through the Vietnam War. Fearless when it came to covering a story, Chapelle was jailed for two months during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 when she was captured by Russia after she went undercover as a spy.

Earning the respect from both the military and journalistic community, Chapelle learned to jump with paratroopers, having often traveled with the troops. Although one of her “firsts” is of a sad circumstance, she was the first female correspondent to be killed in the Vietnam War. She was buried with full military honors, a rarity for civil journalists.

See the brilliant photos by the first American

female war photographer

Marjory Collins (1912-1985) was an American photojournalist best known for her coverage of the home front during World War II. She described herself as a “rebel looking for a cause.” She began her career in NYC in the 1930’s working for PM and U.S. Camera magazine.

Post WWII, Collins combined her passions of writing and photography and worked internationally as a freelance photographer. A devote feminist and activist, she founded the journal Prime Time “for and by older women.”

Ruth Baldwin Cowan (1901–1993) began her career as a weekend movie reviewer, but quickly became a reporter for the San Antonio Evening News. Ruth Baldwin Cowan dropped her first name and began freelancing forThe Houston Chronicle and soon the United Press under the pseudonym Baldwin Cowan to conceal her gender, since the publications strictly forbid hiring women.

When her identity was outed, she was soon let go but quickly contacted the Associate Press, who hired her promptly. She worked for the Associate Press for the next 27 years, covering Washington’s social life, Eleanor Roosevelt’s press conferences and a multitude of human interest stories, but she is best known for her work as an overseas correspondent during World War II. Read her obituary here.

Martha Gellhorn (1908–1998) was an American journalist, novelist, and travel writer who is now considered one of the greatest war correspondents of the twentieth century. During 60-year career, she reported on nearly every major world conflict, from the Spanish Civil War, to the rise of Adolf Hitler, through the outbreak of WWII, and the Vietnam War.

While she may be known as the third wife of the novelist Ernest Hemingway, her journalistic accomplishments far outshine the brief marriage. In attempt to witness the Normandy landings, Gellhorn hid in a hospital ship bathroom and impersonated as a stretcher bearer to gain access. She was the only woman to land at Normandy on D-Day in 1944, and among the first journalists to report from Dachau concentration camp after it was liberated in 1945.

Quotes by Gellhorn here on Literary Ladies Guide

The Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism

Marguerite Higgins Hall 1920–1966 was an American reporter and war correspondent, covering World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War working for the New York Herald Tribune and Newsday. After witnessing the Hangang Bridge bombing in Seoul, she was denied entry to U.S. military headquarters in Suwon, South Korea after arriving by raft with her colleagues.

She was ordered out of the country by the General, but after making an appeal to his superior, the Herald Tribune received a telegram stating “The ban on women correspondents in Korea has been lifted. Marguerite Higgins is held in highest professional esteem by everyone.” This was a major breakthrough for all female war journalists. Higgins was also the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for Foreign Correspondence in 1951 for her coverage of the Korean War. See more about Hall’s Pulitzer Prize.

You might also like:

10 Pioneering African-American Female Journalists

If you’d like more on this subject, try to find the film No Job for a Woman, the 2011 documentary that focuses on Martha Gellhorn, Ruth Cowan, and Dickey Chappelle, and their fight for the right to report on World War II. Unfortunately, it’s almost impossible to find this film to stream online. Check for it at your local public or university library.

The post 6 Female Journalists of the World War II Era appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 30, 2018

Books by Beatrix Potter: The Tale of Peter Rabbit and More

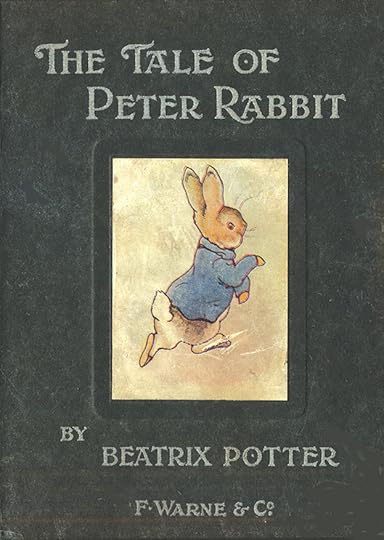

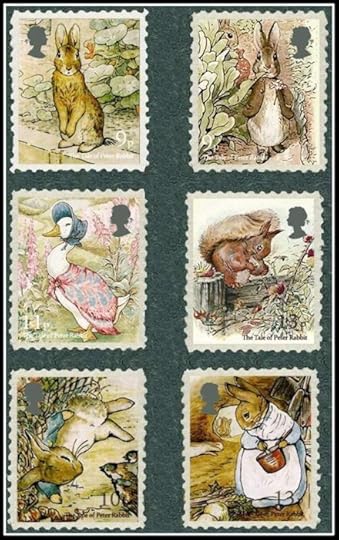

Beatrix Potter (1866 – 1943) the British author and illustrator of children’s books, took her inspiration from a childhood spent in nature and with animals, plus a vivid imagination. Best known for The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), Beatrix both wrote and illustrated this popular children’s book, which was originally self-published. The book was inspired by Beatrix’s two childhood pet rabbits, Benjamin Bouncer and Peter Piper.

As a child, Beatrix was encouraged to pursue her passion for drawing and painting, gathering inspiration from her natural surroundings and family pets. Beatrix and her brother would illustrate postcards when they went on holiday to Scotland, sending letters back home to friends.

In 1893, while on holiday, after having run out of things to write about, she wrote a story to the children of friend about “four little rabbits whose names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail and Peter.” It would later become one of the most famous children’s letters ever written, and laid the groundwork for Beatrix Potter’s success as a writer, artist, and storyteller.

In 1901, the story of Peter Rabbit was initially rejected by several publishers, until Beatrix decided to publish the book herself. She printed 250 copies for family and friends. Publishing company Frederick Warne & Co. noticed the success of her self-printed copies, and agreed to publish The Tale of Peter Rabbit if Beatrix re-illustrated the book in color. It was an immediate bestseller. In all, she wrote and illustrated 24 children’s books; the following list of Beatrix Potter books are among the best known.

The Tale of Peter Rabbit

This best-selling children’s book has been translated in 36 different languages with over 45 million copies sold. The character of Peter Rabbit has generated merchandise for both children and adults alike, with the first Peter Rabbit doll patented by Beatrix Potter in 1903. The story is of a young rabbit, Peter, advised by his widowed mother to avoid the vegetable garden of a man named Mr. McGregor. His mother reminds Peter of his fathers demise, where he was “put into a pie by Mrs. McGregor.” Rebellious by nature, Peter sneaks into the garden only to over-indulge on the bountiful produce and is nearly caught by Mr. McGregor. The children’s book is beautifully illustrated and imaginative of the life of a family of rabbits.

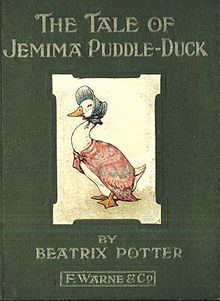

The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck

Similarly to The Tale of Peter Rabbit, both in reader popularity and with spinoff merchandise,The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck (1908) was both written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter. The book is of a domestic duck named Jemima, whose eggs are repeatedly confiscated by the farmers wife, who believes Jemima to be “a poor sitter.” Jemima attempts to find a place far from the farm to lay her eggs, confiding in a sly fox who invites her to do so in a nest at his home.

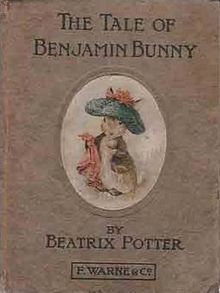

The Tale of Benjamin Bunny

A sequel to the successful Peter Rabbit, the story tells of Peter Rabbit returning to Mr. McGregor’s garden with his cousin Benjamin to retrieve clothing he lost while on his first escapade in the garden. The character of Benjamin returned in Beatrix’s book The Tale of Flopsy Bunnies and Mr. Tod as an adult rabbit. In 1992 Benjamin Bunny was adapted as an episode of The World of Peter Rabbit and Friends on BBC.

Beatrix Potter books on Amazon

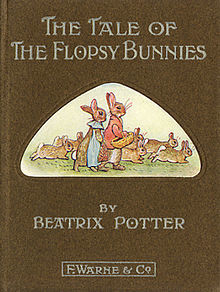

The Tale of the Flopsy Bunnies

After writing two full-length tales of bunnies, Beatrix yearned for a change in story. Unable to deny the popularity of her rabbit stories and illustrations, Beatrix grabbed plot elements and characters from The Tale of Peter Rabbit and The Tale of Benjamin Bunny to develop The Tale of Flopsy Bunnies (1909). Her illustrations for this book were inspired by the flowerbeds and garden of archways of her aunt and uncles home in Wales.

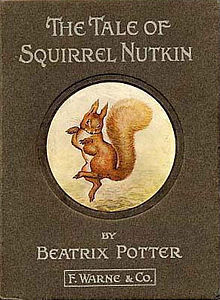

The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin

Published in 1903, The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin the story follows an ill-mannered red squirrel named Nutkin. Similarly to the inspiration of the Peter Rabbit tales, the origins of Squirrel Nutkin are traced to letters Beatrix wrote to Norah Moore, the daughter of the former governess, Annie Carter Moore. A shortened version of the tale appeared in the 1971 ballet film, The Tales of Beatrix Potter.

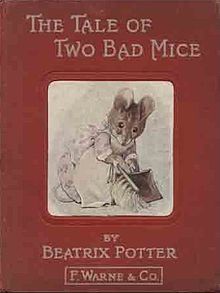

The Tale of Two Bad Mice

Inspired by two mice caught in a cage-trap in her cousins home, and in a dollhouse being constructed by her editor and publisher Norman Warne for his niece. As the tale developed, the two fell in love. The story is of two mice who vandalize a dollhouse, destroying the dining room after finding food. The tales theme of rebellion and destruction is analyzed as a reflection of Beatrix’s own desire to separate and free herself from her parent’s scrutiny and disdain over her relationship with Norman Wane, whom she did later marry despite her parents wishes.

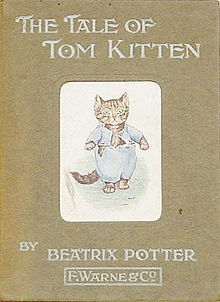

The Tale of Tom Kitten

The Tale of Tom Kitten (1907) is to teach children of manners and respectful obedience. The story follows the character Tabitha Twitchit, a cat who invites her friends over for tea. After dutifully washing and dressing her three kittens, they soon soil their outfits after romping around in the garden. Banishing the kittens upstairs to the bedroom until the tea party is over, the “dignity and repose of the tea party” is threatened to be ruined after the kittens disobediently cause a ruckus upstairs.

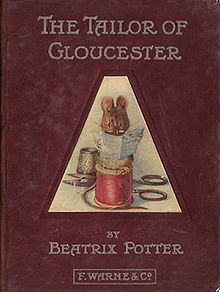

The Tailor of Gloucester

The Tailor of Gloucester (1902) was privately printed by Beatrix Potter in 1902, and later published by Frederick Warne & Co. in 1903. Potter has declared this book to be her favorite. The story is about a tailor who saves a mouse from his cat, who later goes on to finish the tailors work on a waistcoat out of gratitude. It is based on a real-life incident between the tailor John Pritchard, a Gloucester tailor commissioned to make a new suit for the mayor. He returned to his shop one early Monday morning to find the suit finished (all except for one buttonhole) with a note saying “No more twist.” Beatrix sketched the Gloucester street the tailors shop resided for her book.

More about Beatrix Potter on this site

Visit 5 ClassicWomen Authors’ Homes In England

Beatrix Potter’s Gardening Life by Marta McDowell

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Books by Beatrix Potter: The Tale of Peter Rabbit and More appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 29, 2018

Life, Love, Freedom, and Dragons: Quotes by Ursula Le Guin

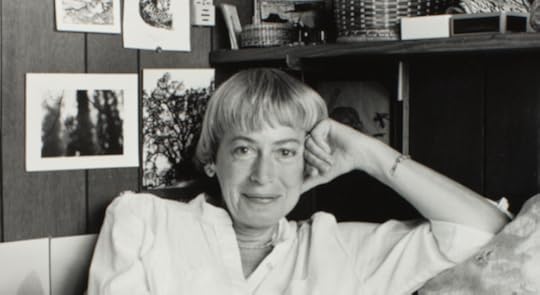

Best known for her literary works in genres of science fiction and fantasy, the American novelist Ursula K. Le Guin (1929 – 2018) also authored children’s books, short stories and poetry. Her skill in the genres of the fantastic is said to have been influenced from her childhood, and inspired her master’s degree in romance literature of the middle ages and Renaissance.

She instilled cultural exploration as a vital part to the genre of her works, her characters vibrantly bursting from the page as scientists, anthropologists, diplomats and travelers. Best described as “fiery” and with having “immense energy” by those who knew her, a passion for life, love, freedom and mythology shines through in these gathered quotes by Ursula Le Guin.

Life’s journey

“It is good to have an end to journey toward; but it is the journey that matters, in the end.” — The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969

“The only thing that makes life possible is permanent, intolerable uncertainty: not knowing what comes next.” —The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969

“There’s a point, around the age of twenty, when you have to choose whether to be like everybody else the rest of your life, or to make a virtue of your peculiarities.” ― The Dispossessed, 1974

“If you evade suffering you also evade the chance of joy. Pleasure you may get, or pleasures, but you will not be fulfilled. You will not know what it is to come home.” ― The Dispossessed, 1974

“And day to day, life’s a hard job, you get tired, you lose the pattern. You need distance, interval. The way to see how beautiful the earth is, is to see it as the moon. The way to see how beautiful life is, is from the vantage point of death.” — The Dispossessed, 1974

“… when I die, I can breathe back the breath that made me live. I can give back to the world all that I didn’t do. All that I might have been and couldn’t be. All the choices I didn’t make. All the things I lost and spent and wasted. I can give them back to the world. To the lives that haven’t been lived yet. That will be my gift back to the world that gave me the life I did live, the love I loved, the breath I breathed.” ― The Other Wind, 2001

“To see that your life is a story while you’re in the middle of living it may be a help to living it well.” ― Gifts, 2004

“When I was young, I had to choose between the life of being and the life of doing. And I leapt at the latter like a trout to a fly. But each deed you do, each act, binds you to itself and to its consequences, and makes you act again and yet again. Then very seldom do you come upon a space, a time like this, between act and act, when you may stop and simply be. Or wonder who, after all, you are.” ― The Farthest Shore, 1972

Photo by William Anthony

“Life rises out of death, death rises out of life; in being opposite they yearn to each other, they give birth to each other and are forever reborn. And with them, all is reborn, the flower of the apple tree, the light of the stars. In life is death. In death is rebirth. What then is life without death? Life unchanging, everlasting, eternal?-What is it but death-death without rebirth?” ― The Farthest Shore, 1972

“I never knew anybody . . . who found life simple. I think a life or a time looks simple when you leave out the details.” ― The Birthday of the World and Other Stories, 2002

“Things don’t have purposes, as if the universe were a machine, where every part has a useful function. What’s the function of a galaxy? I don’t know if our life has a purpose and I don’t see that it matters. What does matter is that we’re a part. Like a thread in a cloth or a grass-blade in a field. It is and we are. What we do is like wind blowing on the grass.” ― The Lathe of Heaven, 1971

Freedom and truth

“The direction of escape is toward freedom. So what is ‘escapism’ an accusation of?” ― No Time to Spare: Thinking about what Matters, 2017

“Distrust everything I say. I am telling the truth.” ―The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969

“Change is freedom, change is life. It’s always easier not to think for oneself. Find a nice safe hierarchy and settle in. Don’t make changes, don’t risk disapproval, don’t upset your syndics. It’s always easiest to let yourself be governed.” ― The Dispossessed, 1974

“But need alone is not enough to set power free: there must be knowledge.” ― A Wizard of Earthsea, 1968

“Truth is a matter of the imagination.” ― The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969

“Freedom is a heavy load, a great and strange burden for the spirit to undertake. It is not easy. It is not a gift given, but a choice made, and the choice may be a hard one. The road goes upward towards the light; but the laden traveler may never reach the end of it.” ― The Tombs of Atuan, 1970

“Belief is the wound that knowledge heals.” — The Telling, 2000

Love

“Love doesn’t just sit there, like a stone, it has to be made, like bread; remade all the time, made new.” ― The Lathe of Heaven, 1971

What is love of one’s country; is it hate of one’s uncountry? Then it’s not a good thing. Is it simply self-love? That’s a good thing, but one mustn’t make a virtue of it, or a profession.” — The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969

“A profound love between two people involves, after all, the power and chance of doing profound hurt.” — The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969

The metaphor of dragons

“People who deny the existence of dragons are often eaten by dragons. From within.” — The Wave in the Mind: Talks & Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination, 2004

“But it is one thing to read about dragons and another to meet them.” ― A Wizard of Earthsea, 1968

“And though I came to forget or regret all I have ever done, yet I would remember that once I saw the dragons aloft on the wind at sunset above the western isles; and I would be content.” ― The Farthest Shore, 1972

Evil

“It is very hard for evil to take hold of the unconsenting soul.” ― A Wizard of Earthsea, 1968

“The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting. This is the treason of the artist; a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain.” ― The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, 1973

Change and uncertainty

“You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.” ― The Dispossessed, 1974

“To learn which questions are unanswerable, and not to answer them: this skill is most needful in times of stress and darkness.” — The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969

“We’re each of us alone, to be sure. What can you do but hold your hand out in the dark?” ― The Wind’s Twelve Quarters, 1975

You might also like:

Quotes by Ursula Le Guin on Writing, Reading, and Storytelling

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Life, Love, Freedom, and Dragons: Quotes by Ursula Le Guin appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

Classical Principles for Modern Design by Thomas Jayne

Classical Principles for Modern Design: Lessons from Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman’s The Decoration of Houses by Thomas Jayne (The Monacelli Press, 2018) shines a new light on the influence of Edith Wharton’s first published book. To the reading public, it may be a surprise that the Pulitzer Prize-winning author co-wrote one of the most influential books on interior design.

Before Edith Wharton gingerly stepped into the realm of fiction, she collaborated with architect Ogden Codman on The Decoration of Houses. First published in 1897, Wharton and Codman overturned the era of heavy-handed Victorian home decor. Their directives called for a more streamlined, comfortable approach that didn’t drown the architecture of rooms and emphasized symmetry and balance.

Photo: Don Freeman

How much of Wharton and Codman’s advice and how many of their principles are still applicable today? In Classical Principles for Modern Design (The Monacelli Press, 2018), Thomas Jayne argues that Wharton and Codman’s ideas about the proportion and planning of space create the most harmonious and livable interiors, whether traditional or contemporary. His authoritative and engaging text traces contemporary ideas about design elements and furnishing rooms back to The Decoration of Houses and shows where his design approach coincides and where it diverges from their views.

The book follows the chapter organization of The Decoration of Houses — chapters on walls, doors, windows, curtains, ceilings and floors, etc. — and adds important new perspectives on the design of kitchens and use of color, both major subjects that Wharton and Codman did not address.

Captured in lush photographs by Don Freeman and others, all speak to Thomas Jayne’s commitment to the primacy of function, quality, and simplicity, derived from the ancient tradition of classical design. As he says, “Tradition is not about what was. Tradition is now.”

Photo: Don Freeman

A brief excerpt from Classical Principles for Modern Design by Thomas Jayne

The following excerpt is from Classical Principles for Modern Design by Thomas Jayne, The Monacelli Press, 2018. Reprinted by permission of the publisher:

First published in 1897, Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman Jr.’s The Decoration of Houses is the level-headed, indispensable book on the subject, about which much has been written over the decades. It’s not an overstatement to say that it is the most important decorating book ever written — and there have been many since.

The Decoration of Houses is like scripture: it is sometimes called the Bible of interior decorating. Like all scared texts, it bears regular reading and rereading to find its meaning. This book is my response, as a practicing decorator, to their work.

Photo: Don Freeman

Wharton is well known to us now as a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist who was sui generis — self-taught and educated, a true autodidact who was able to fully imagine the interior worlds of her largely upper-crust characters. It is with good reason that The House of Mirth, Ethan Frome, and The Age of Innocence are still required reading.

But when The Decoration of Houses came out, Wharton hadn’t yet written a novel, and Codman was just beginning a career as an architect. Codman is certainly the lesser known of the pair, a child of privilege and a distant cousin of Wharton. See brought a practical, working knowledge of design to their collaboration, and interior design was really his strong suit. They first interacted professionally when he was hired to work on her house in Newport, Rhode Island. Years later, he helped her design her Berkshires home, The Mount.

… Wharton and Codman’s book is an elegantly stated argument about the primacy of function, quality, and simplicity, derived from the ancient tradition of classical design.

About Thomas Jayne

AD 100 designer Thomas Jayne is founder and principal of Jayne Design Studio. His interiors reflect his passion and wide-ranging knowledge of classical traditions and his quest to further those traditions within contemporary design. He is the author of the highly successful The Finest Rooms in America: Fifty Influential Interiors from the Eighteenth Century to the Present and American Decoration: A Sense of Place, a monograph on the work of Jayne Design Studio (both published by The Monacelli Press).

You might also like:

Visiting The Mount — Edith Wharton’s home in Lenox, MA

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Classical Principles for Modern Design by Thomas Jayne appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 28, 2018

Quotes by Ursula Le Guin on Writing, Reading, and Storytelling

Ursula K. Le Guin (1929 – 2018) stirred the imagination with her powerful novels and stories. Though known primarily as a masterful and influential writer of science fiction and fantasy, she wrote across many genres. The imaginary worlds she created were commentaries on our own, with the complexities of human nature. She also spoke eloquently about the art and craft of writing, and considered storytelling as a cornerstone of human experience. Here are some favorite quotes by Ursula Le Guin on writing, reading, and storytelling in her inimitable, compelling voice.

“There have been great societies that did not use the wheel, but there have been no societies that did not tell stories.” ―The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction, 1979

“We read books to find out who we are. What other people, real or imaginary, do and think and feel… is an essential guide to our understanding of what we ourselves are and may become.” — UrsulaLeGuin.com

“A writer is a person who cares what words mean, what they say, how they say it. Writers know words are their way towards truth and freedom, and so they use them with care, with thought, with fear, with delight. By using words well they strengthen their souls. Story-tellers and poets spend their lives learning that skill and art of using words well. And their words make the souls of their readers stronger, brighter, deeper.” — “A Few Words to a Young Writer,” 2008

Photo: LitHub

“As you read a book word by word and page by page, you participate in its creation, just as a cellist playing a Bach suite participates, note by note, in the creation, the coming-to-be, the existence, of the music. And, as you read and re-read, the book of course participates in the creation of you, your thoughts and feelings, the size and temper of your soul.” — The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction, 1979

“The book itself is a curious artifact, not showy in its technology but complex and extremely efficient: a really neat little device, compact, often very pleasant to look at and handle, that can last decades, even centuries. It doesn’t have to be plugged in, activated, or performed by a machine; all it needs is light, a human eye, and a human mind. It is not one of a kind, and it is not ephemeral. It lasts. It is reliable. If a book told you something when you were fifteen, it will tell it to you again when you’re fifty, though you may understand it so differently that it seems you’re reading a whole new book.” — “Staying Awake: Notes on the alleged decline of reading,” Harper’s Magazine, February 2008

“I think hard times are coming, when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies, to other ways of being. And even imagine some real grounds for hope. We will need writers who can remember freedom: poets, visionaries — the realists of a larger reality. Right now, I think we need writers who know the difference between production of a market commodity and the practice of an art. The profit motive is often in conflict with the aims of art.” — National Book Awards speech, 2014

“While we read a novel, we are insane — bonkers. We believe in the existence of people who aren’t there, we hear their voices… Sanity returns (in most cases) when the book is closed.”

“The unread story is not a story; it is little black marks on wood pulp. The reader, reading it, makes it live: a live thing, a story.” ― Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places, 1989

“The use of imaginative fiction is to deepen your understanding of your world, and your fellow men, and your own feelings, and your destiny.” ― The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction, 1979

“I want the story to have a rhythm that keeps moving forward. Because that’s the whole point of telling a story. You’re on a journey — you’re going from here to there. It’s got to move. Even if the rhythm is very complicated and subtle, that’s what’s going to carry the reader.” — Paris Review Interviews, 2013

“Rewriting is as hard as composition is — that is, very hard work. But revising — fiddling and polishing — that’s gravy — I love it. I could do it forever. And the computer has made it such a breeze.” — UrsulaLeGuin.com

Ursula K. Le Guin’s books on Amazon

“Hardly anybody ever writes anything nice about introverts. Extroverts rule. This is rather odd when you realize that about nineteen writers out of twenty are introverts. We are been taught to be ashamed of not being ‘outgoing’. But a writer’s job is ingoing.” — The Birthday of the World and Other Stories, 2002

“In reading a novel, any novel, we have to know perfectly well that the whole thing is nonsense, and then, while reading, believe every word of it. Finally, when we’re done with it, we may find — if it’s a good novel — that we’re a bit different from what we were before we read it, that we have been changed a little, as if by having meet a new face, crossed a street we’ve never crossed before.” — The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969

… When people say, did you always want to be a writer? I have to say no! I always was a writer. I didn’t want to be a writer and lead the writer’s life and be glamorous and go to New York. I just wanted to do my job writing, and to do it really well.” — Paris Review Interviews, 2013

“As for ‘write what you know,’ I was regularly told this as a beginner. I think it’s a very good rule and have always obeyed it. I write about imaginary countries, alien societies on other planets, dragons, wizards, the Napa Valley in 22002. I know these things. I know them better than anybody else possibly could, so it’s my duty to testify about them.” — UrsulaLeGuin.com

“Hey, guess what? You’re a woman. You can write like a woman. I saw that women don’t have to write about what men write about, or write what men think they want to read. I saw that women have whole areas of experience men don’t have—and that they’re worth writing and reading about.” — Paris Review Interviews, 2013

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes by Ursula Le Guin on Writing, Reading, and Storytelling appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 26, 2018

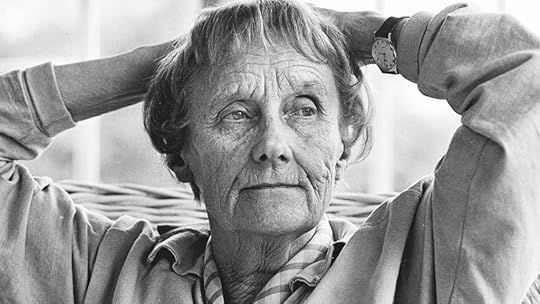

Astrid Lindgren

Astrid Anna Emilia Ericsson Lindgren (November 14, 1907 – January 28, 2002) was a Swedish writer of fiction and screenplays, best known for her children’s book series featuring the independent and strong Pippi Longstocking. As of January 2017, Lindgren is the world’s eighteenth most-translated author, and the fourth most-translated children’s book writer. Her books have sold roughly 144 million copies worldwide.

An Imaginative Childhood

Born on a farm in Sweden, Astrid enjoyed a happy childhood. The daughter of tenant farmer Samuel August Ericsson and homemaker Hanna Jonsson Ericsson, she was the second of four siblings. Raised by her nurturing parents with tales and storytelling, she was taught how to apply her imagination and creativity in the world of literature. It’s been said that many of the characters and settings in Lindgren’s books are inspired by her own childhood, quoted in her obituary in the New York Times.

A natural-born writer, Astrid published her first story in the Vimmerby Times (Vimmerby Tindingen) at age 13. After finishing school, she took a job with the local newspaper and began writing reviews, advertisements, and eventually articles.

Rise to Recognition

Astrid began a relationship with the chief editor of the newspaper, a married father, who proposed to her in 1926 after she became pregnant. She was then 18 years old. Refusing the proposal, she moved to Copenhagen to have her son, Lars. For the following three years, Lars remained in foster care while Lindgren worked in Stockholm, traveling to visit him when she could. At age 3, he moved in with his grandparents in Vimmerby.

In Stockholm, Astrid worked as a secretary at the Royal Swedish Automobile Club, where she met her husband, the office manager Sture Lindgren, in 1928. In 1934 Astrid gave birth to her daughter, Karin Lindgren. When time allowed, the stay-at-home mother of two children wrote short stories for the magazine Landsbygdens Jul (A Country Christmas), bringing in some extra money.

See also: Quotes by Astrid Lindgren

When her daughter Karin was seven years old and recovering from pneumonia, she asked her mother to tell her a story about “Pippi Longstocking.” From that spark, a literary star was born, changing Astrid Lindgren’s life forever. “I didn’t ask her who Pippi Longstocking was,” Mrs. Lindgren told The New Yorker in 1983. “I just began the story, and since it was a strange name it turned out to be a strange girl as well.”

Three years later, stuck in bed rest with an injured leg, Astrid Lindgren began to write the stories of Pippi Longstocking for her daughter’s tenth birthday. After sending copies to the publisher Albert Bonniers Förlag and being rejected, she discovered her love and passion for writing books. Soon after, she wrote Britt-Mari Lättar Sitt Hjärta (Confidences of Britt-Mari). It came second in the publishing house Rabén & Sjögren’s writing competition for girls’ fiction. In 1945 Rabén & Sjögren’s published Pippi Longstocking.

Noteworthy Public Figure

Astrid Lindgren’s success with her published books quickly brought her into the public eye. She became involved in national debates on issues including taxation policies, nuclear power and the treatment of children, refugees and animals. Thus began her adult career of public recognition, granting her many awards and honors.

In 1956, she received the Swedish State Award, and in 1958, the Hans Christian Andersen medal, the highest international award in children’s literature. To mark her 60th birthday in 1967, the Astrid Lindgren Prize was instituted by Rabén & Sjögren. The prize is awarded every year for outstanding authorship in Swedish children’s and young adult literature.

Continuing her growing success, in 1973 she was awarded the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award. In the 1980’s, as large commercial farms replaced family farms, she campaigned for protection and the welfare of farm animals. “Every pig is entitled to a happy pig life,” she wrote in an open letter to Prime Minister Ingvar Carlsson. The law, which was passed in 1988, ensured animals freedom from cramped conditions and access to clean straw. It is known informally as Lex Astrid.

In 1993, Astrid Lindgren was awarded the UNESCO Book Award in 1993, and in 1994 she received the Right Livelihood Award, “For her commitment to justice, non-violence and understanding of minorities as well as her love and caring for nature.”

Success Beyond Her Years

Mrs. Lindgren continued to be a public figure up until her death, passing away on January 28th, 2002, at the age of 91 in her home in Dalagatan. The funeral was held on International Women’s Day on March 8th, 2002 in Stockholm. The streets were filled with mourners, celebrating the inspiring authors life.

But even after her death, she continued to inspire and grow recognition. Shortly after her death in 2002, the Swedish government founded the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, the world’s largest children’s and youth literature prize. In April 2011 the Bank of Sweden announced that one of the new bank notes planned for 2014-15 will bear a portrait of Astrid Lindgren.

More about Astrid Lindgren on this site

Quotes by Astrid Lindgren

Major Works

Pippi Longstocking (1945)

Pippi in the South Seas (1948)

Pippi Goes on Board (1946)

Pippi’s Extraordinary Ordinary Day (1999)

Ronja the Robbers Daughter (1981)

The Tomten and the Fox (1966)

The Children of Noisy Village (1962)

Mio, My Son (1954)

The Brothers Lionheart (1973)

Seacrow Island (1964)

The Six Bullerby Children (1947)

More information on Astrid Lindgren

A short biography

Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award Website

Lindgren’s books on Goodreads

Obituary

Wikipedia

News, articles, etc.

Astrid Lindgren’s second world war diaries published in Sweden

How war created Pippi Longstocking

Book Reviews

Review of War Diaries

To Astrid Lindgren: Farewell and Thank You

Biographies

Astrid Lindgren: The Woman Behind Pippi Longstocking by Jens Andersen (2018)

Astrid Lindgren: Storyteller to the World by Johanna Hurwitz (2016)

Astrid Lindgren: A Critical Study by Vivi Blom Edstrom (2000)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Astrid Lindgren appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

Quotes by Astrid Lindgren, Author of Pippi Longstocking

Astrid Lindgren (1907-2002) was an incredible Swedish public figure, author and screenplay writer. Best known for her children’s book series, Pippi Longstocking, Lindgren is the recipient of many honors and awards for her support and role in fighting for children and animal rights. She is the 18th most translated author, and even has a minor planet named after her that was discovered in 1978. Here is a sampling of quotes by the inspiring author.

“Everything great that ever happened in this world happened first in somebody’s imagination.” (Astrid Lindgren 1958, from the speech held at the reception of the H C Andersen Award)

“Don’t let them get you down. Be cheeky. And wild. And wonderful.”

“And so I write the way I myself would like the book to be — if I were a child. I write for the child within me.” (Expressen, December 6th)

Astrid Lindgren’s books on Amazon

“If I have managed to brighten up even one gloomy childhood — then I’m satisfied.”

“A childhood without books — that would be no childhood. That would be like being shut out from the enchanted place where you can go and find the rarest kind of joy.”

“What the world of tomorrow will be like is greatly dependent on the power of imagination in those who are learning to read today.”

“I have never tried that before, so I think I should definitely be able to do that.” (Pippi Longstocking)

Learn more about Astrid Lindgren

“I have been very interested in labor movement. If I could have wished another life, I would have loved to be a pioneer woman in the beginning of labor movement.”

“I have never experienced being madly in love the way most people seem to have been, although it is not something I would miss. Instead I have had an enormous ability to love my children and my grandchildren and my great grandchildren.”

“I don’t mind dying, I’ll gladly do that, but not right now, I need to clean the house first.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes by Astrid Lindgren, Author of Pippi Longstocking appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 24, 2018

Themes and Tips for a Successful Book Club (when you need a change of pace)

These days, I know as many women as not that belong to a book club (or book group, as it’s often known). While book clubs can be rewarding for anyone, male or female, single or part of a family, they’re perfect brief respites from the stresses of life, especially for busy women. Book groups can form strong bonds and have surprising longevity, becoming somewhat of an anchor as the world shifts beneath our feet. There’s something about the combination of good books and good friends that feels quite timeless, and comforting.

Whether your group has been together for two years or two decades, it’s possible to fall into a rut. Are you squeezing out 30 to 45 minutes of discussion on who did or didn’t like the latest novel you chose before digressing into idle chit-chat? If so, you might need a change of pace. Here are some themes and tips for successful book group (aka book club) meetings, especially for times when you need a change of pace and shake things up:

Nonfiction themes

In a book group I belonged to some years ago, some of our fiction selections fell short of expectations in the first months of our meetings. We didn’t know one another very well, and somehow our discussions were falling flat. What helped us gel as a group was switching nonfiction for a while. Our selections included travel memoirs, the simplicity movement, mindfulness, and more.

By focusing more on the themes rather than literary analysis or our opinions about the books, we became more comfortable with discussion, and re-introduced fiction into the mix by and by.

Classic women authors

If you had your fill of male authors in school, consider filling in the blanks of your literary education with books by classic women authors. Willa Cather, Zora Neale Hurston, Pearl S. Buck, Kate Chopin, Carson McCullers, Daphne Du Maurier … the list goes on. See a roster of notable and often undervalued authors of the past at the top of this and every other page on this site, and in our Wish List — the list of classic authors we intend to add to this site.

Reading and eating

This duo of passions can become one delicious ritual. Combine your discussions with a potluck dinner, brunch, or even a high tea. Take this theme to its utmost by choosing books with a culinary thread — rustic French fare with A Year in Provence; earthy Mexican food in Like Water for Chocolate; and speaking of chocolate, Chocolat. A few more recent food-themed novels include The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, The Mistress of Spices, and Pomegranate Soup. There are many others; get more ideas in this list of food in fiction.

Lunch hour book group

Those with truly crowded schedules might want to take a page from a professional women’s book group in Washington, D.C. The group convenes once a month in one of several museum cafés, taking longer-than-usual lunch breaks to discuss Pulitzer Prize-winning books. You need not go full-on Pulitzer, but some unifying theme could help keep this kind of lunch break group focused.

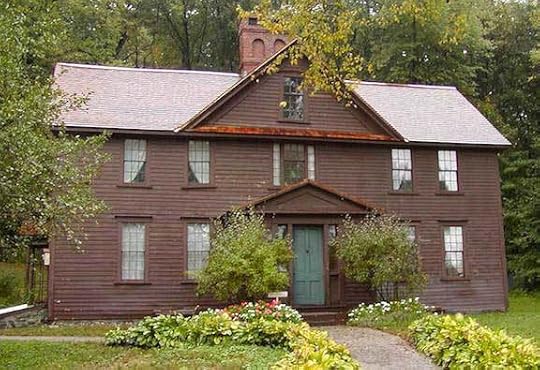

Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House

is one of several women authors’ homes to visit in New England

Book group field trips

Enrich your reading group experiences by taking field trips or occasional pilgrimages to literary sites. Planning this kind of adventure for your group can be a stimulating once-a-year event. Is there a well-known author’s home, a special library, or a college hosting a related exhibit or event? Is a well-known figure you’re reading about connected in some way in an area nearby?

Within a 3-hour range of where my book group lives and meets, are the historic homes of Mark Twain, Edith Wharton, Washington Irving, Pearl S. Buck, Emily Dickinson, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Herman Melville, and others. Yes, you guessed it, New York State and New England.

Do some research and discover which authors lived in or wrote about your region. Read their writings and/or a biography, then plan a voyage to pay homage to your local literary luminaries.

Women’s biographies

One book group I heard tell of reads biographies of accomplished or daring women. Their selections have included bios of Georgia O’Keefe, Amelia Earhart, Billie Holiday. Others you might consider are Cleopatra, Martha Graham, and Eleanor Roosevelt. If you like to read about women authors, see our selected list of 12 Great Biographies of Women Authors.

The lives of the talented and famous were never tidy and not always happy, but they followed their unique paths, even if it meant breaking the rules. Their life stories can be tremendously inspiring.

Phyllis Rose, in The Norton Book of Women’s Lives, offers a great perspective on why it’s so gratifying to read women’s biographies: “I wanted to know what the possibilities were for women’s lives … I wanted wild women, women who broke loose, women who lived to the fullest.”

Young adult books and children’s classics

When you need a break from 400-page tomes, there’s a lot of great contemporary literature in the Young Adult sector. There’s no shortage of heavy themes here, to be sure, but the books are eminently readable. Time magazine offers this list of the 100 Best Young Adult Books of All Time.

We discussed classics by women authors above; you can also consider the great classics of children’s literature — ones the members of your group never read, and others that haven’t been cracked open in decades, and ripe for revisiting. Among them: Anne of Green Gables, A Little Princess, Little Women, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Reconnect with your inner girl, and rediscover why these classics are so timeless. and if you have any daughters, read these with them — and invite them to join in the meeting!

RELATED POSTS

Reading Aloud to Children: Creating Lifelong Book Lovers

4 Ways to Love Books as a Family

Photo credits

Teacup and books (top), Anete Lusina/Unsplash

Mindfulness book, Breather/Unsplash

Teacup and books (middle), freestock.org/Unsplash

A Little Princess & Anne of Green Gables, Annie Spratt / Unsplash

The post Themes and Tips for a Successful Book Club (when you need a change of pace) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 22, 2018

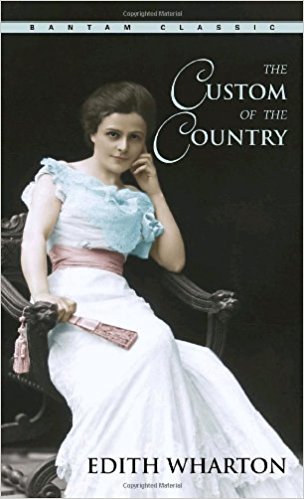

The Custom of the Country by Edith Wharton

The Custom of the Country by Edith Wharton (1913) is the story of Undine Spragg, an ambitious, yet naïve young woman from the American midwest. Raised in the fictional town of Apex, and the product of a family who has risen to a certain financial status through sketchy financial dealings. She strives to rise into New York City society through a succession of marriages and divorces that ultimately lead to her undoing.

Undine Spragg has often been compared to Becky Sharp, the heroine (so to speak) of Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray, minus any of the charm. It has occasionally been supposed whether Edith Wharton, though a woman herself, was a misogyynist. Though The Custom of the Country has been more favorably viewed through the long lens of literary history, its main character, like so many other of Wharton’s fictional females, was devoid of any redeeming qualities.

Though Wharton was considered a significant literary figure from the time her first novel, The House of Mirth (1905) was published, reviewers occasionally expressed their disappointment at her subjects and characters, even as they admired her talent. Here is one such view of The Custom of the Country that appeared when the novel was published in 1913:

From the original Louisville Courier-Journal review of The Custom of the Country by Edith Wharton, November 1913: Despite its many excellent points, Mrs. Wharton’s new novel, The Custom of the Country, makes one again regret that a writer of such brilliance, such insight, such worldly wisdom, should waste time on some of the material she employs. In the America of today — bad as it is, in perhaps acute and ugly stages of transition — her pen could surely find a more significant field for analysis, could discover social processes far more deserving of notation.

Even as Lily Bart of The House of Mirth was a heroine descending the social stairs, so Undine Spragg of this present novel is that pitiable creature, a social climber, making her way up society’s beanstalk.

Insatiable egotism

A direct route to Paradise seemed that ladder when viewed from Undine’s place of upbringing, town called, ironically, Apex. Undine’s history and character is interpreted by Mrs. Wharton as the result of “the custom of the country” which develops insatiable egotism in its vain, beautiful women. Undine Spragg’s beauty and ambition were abetted to the utmost by the money of her excellently portrayed father, Abner Spragg, lift her out of her place of birth and its crude bourgeoisie, into New York’s sacred circles of old families, and eventually into an aristocratic French tribe.

With her trained powers of analysis and presentation, Mrs. Wharton deftly portrays the various social groups of Undine’s remarkable transit. The Apex crowd, the dignified New York circle, the French family with its traditional solidarity and ideals. A flawless realism depicts Undine Spragg with all her ineradicable crudities, her vanity, egotism, feeling for beauty of a material order. Her progress — or descent — is logical in a fearfully veracious manner.

Is the story worth 600 pages?

In fact, with the truth of the novel and its technical excellence, perhaps no fault at all may be found. But thus all the more glaring is the disparity between such successful presentation and the thing portrayed. Certainly the vain, crude, self-indulgent Udine Spragg and those like her, and their foolish, gullible fathers, their assortment of husbands abound in America today.

But after all, are their vulgar careers worth 600 pages from the pen of one of the country’s most gifted fiction writers? To beg the question, perhaps so. There may be a mode of treating such social phenomena, true types of the epoch, of employing them in a significant story.

The Custom of the Country on Amazon

With a far worse specimen, Thackeray immortalized an unscrupulous social adventuress. Ah, but in Becky Sharp (of Vanity Fair) and in the author’s point of view — his creative mood, so to speak — there were advantages. Becky, though devilish, could be so interesting. And Thackeray saw her in that light of true, if terrible satire, of exquisite irony which lifts a portrayal to the plane of notable art.

Mrs. Wharton’s irony savors rather of sarcasm. Her portrayal seldom achieves that fine satire, that humor of pathos distinguishing momentous novels.

More about The Custom of the Country by Edith Wharton

Wikipedia

Reading Guide to The Custom of the Country

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Read online at Project Gutenberg

Audio version on Librivox

Contemporary review on Vulpes Libris

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Custom of the Country by Edith Wharton appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 20, 2018

How Mary Mapes Dodge Came to Write Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates

Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates by Mary Mapes Dodge (1865) is the classic tale of Hans and his sister Gretel (not to be confused with Hansel and Gretel). It takes place in Holland, and though the author created a lovely picture of Dutch life in the early 19th century, she never visited the country until well after the book’s publication.

In the 1946 edition, the Brinker children’s parents are described as a “gallant mother and strange, silent father.” The latter’s condition, as it turns out, is due to a head injury sustained The family is relatable and timeless because they “are very real people with ambitions, hopes and problems that the young reader shares as he or she reads their story. The Brinkers are very poor, but during one eventful winter many wonderful things happen to them.”

The story centers on a period in which the family’s luck turns: “The grand race, the silver skates, the missing thousand guilders — these factors all play their parts in bringing happiness to the little family.” Filled with youthful ambition and honor, the story is also believed to have introduced the idea of the sport of speed skating to American readers.

The author’s preface

In her preface, the author, Mary Mapes Dodge wrote: “This little work aims to combine instructive features of a book of travels with the interest of a domestic tale. Throughout its pages the descriptions of Dutch localities, customs, and general characteristics have been given with scrupulous care. Many of its incidents are drawn from life, and the story of Raff Brinker is founded strictly upon fact.

… Should this simple narrative serve to give my young readers a just idea of Holland and its resources, or present true pictures of its inhabitants and their everyday life, or free them from certain prejudices concerning that noble and enterprising people, the leading desire in writing it will have been satisfied.”

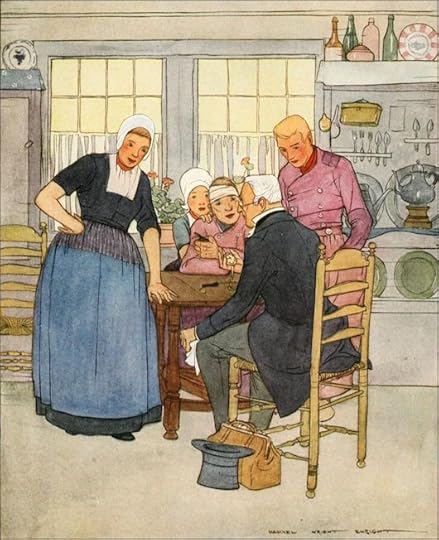

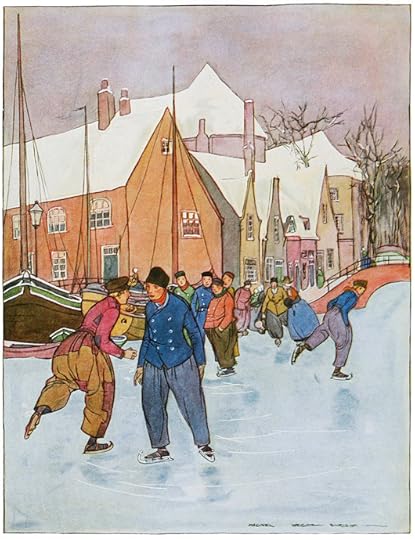

Illustration by Maginel Wright Enright from Hans Brinker

Dutch neighbors provide a spark of inspiration

In the introduction to the 1946 edition, May Lamberton Becker described how Mary Dodge came to write Hans Brinker. She had never been to Holland herself, but after reading Rise of the Dutch Republic and meeting a Dutch couple who were neighbors, she became fascinated. She asked her neighbors what life was like in “the land of pluck,” and they were all too happy to oblige.

A widow with two sons to support, Mary had already established herself as a writer and editor when she began writing Hans Brinker. When it came out in 1865, it followed on the heels of her first full book, The Irvington Stories (1864) which was a modest success. Her publisher at the time was doubtful about the idea of a book about Dutch kids. Nobody, he said, was interested in Holland, least of all children.

Illustration by Maginel Wright Enright from Hans Brinkeer

An instant success and enduring classic

Obviously, he was proven wrong. As soon as Hans Brinker was published, according to May Lamberton Becker, “it went like wildfire and has kept going ever since.” Within four years it had won the most celebrated literary award of the period, the Moynton Prize of the French Academy. Within thirty years it went though more than a hundred editions and appeared six languages.

None of Mary Dodge’s other books or stories would ever equal the success of Hans Brinker, but she made her mark as a progressive and talented editor of children’s literature. In 1873 she became editor of a new monthly magazine for children called St. Nicholas, which proved immensely popular.

She had an eye for talent, and published such classic storytellers as Rudyard Kipling, Louisa May Alcott, and even eminent poets like Tennyson and Longfellow.

A visit to Holland long after the fact

“But with all this,” May Lamberton Becker concluded in the 1946 edition’s introduction, “I think Mrs. Dodge’s happiest moment must have been when, as a world-famous woman, she went to Holland for the first time and found to here delight that it was really just as she had pictured it for young folks, and that little Dutch children loved Hans Brinker as much as children did in the United States.”

The 1946 edition, published some 40 years after Mary Dodge’s death, featured new illustrations by Dutch artist and author Hilda van Stockum, who was born and raised in Holland.

Hans Brinker by Mary Mapes Dodge on Amazon

How it begins: Chapter 1 – Hans and Gretel

On a bright December morning long ago, two thinly clad children were kneeling upon the bank of a frozen canal in Holland.

The sun had not yet appeared, but the gray sky was parted near the horizon, and its edges shone crimson with the coming day. Most of the good Hollanders were enjoying a placid morning nap; even Mynheer von Stoppelnoze, that worthy old Dutchman, was still slumbering “in beautiful repose.”

Now and then some peasant woman, poising a well-filled basket upon her head, came skimming over the glassy surface of the canal; or a lusty boy, skating to his day’s work in the town, cast a good-natured grimace toward the shivering pair as he flew along.

Meanwhile, with a vigorous puff and pull, the brother and sister, for such they were, seemed to be fastening something upon their feet, not skates, certainly, but clumsy pieces of wood narrowed and smoothed at their lower edge, and pierced with holes, through which they were threaded strings of rawhide.

These queer-looking affairs had been made by the boy Hans. His mother was a poor peasant woman, too poor even to think of such a thing as buying skates for her little ones. Rough as these were, they had afforded the children many a happy hour on the ice; and now as with cold, red fingers our young Hollanders tugged at the strings, their solemn faces bending closely over their knees, no vision of impossible iron runners came to dull the satisfaction glowing within …

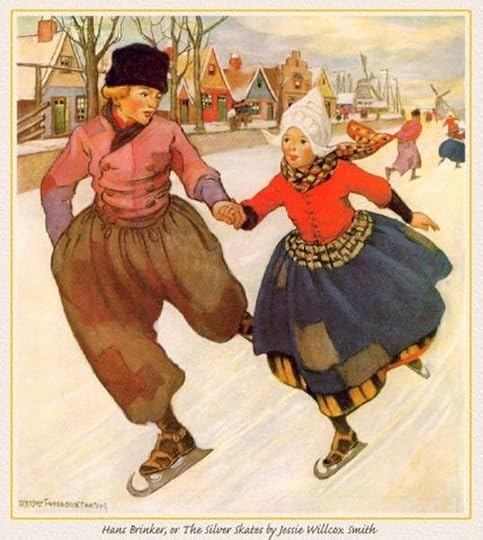

Hans Brinker illustration by Jessie Wilcox Smith

More about Hans Brinker by Mary Mapes Dodge

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Listen on Librivox

Hans Brinker on Project Gutenberg

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post How Mary Mapes Dodge Came to Write Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.