Nava Atlas's Blog, page 93

February 13, 2018

Little Lord Fauntleroy by Frances Hodgson Burnett

Little Lord Fauntleroy by Frances Hodgson Burnett was the British-American author’s first novel for children. The story was published as a serial in the St. Nicholas Magazine from November 1885 through October 1886 and released as a book later in 1886. The novel’s illustrations would later inspire fashion trends throughout Europe and America — often to the chagrin of little boys who were compelled to wear them.

The story follows the journey of a little boy who goes to live with his bitter grandfather in England, after he unexpectedly inherits a lofty British title and a great deal of wealth. Burnett skillfully threads the story with timeless themes of family and kindness, creating a classic book relatable across all ages.

The inspiration for the Little Lord

Burnett, her husband, and son left Knoxville, Tennessee, for a European trip abroad while pregnant with her second child. Their expenses were to be partly covered by earnings from her writing, giving the family time to travel before settling in Paris, where her younger son Vivian was born.

While Burnett’s husband, Dr. Swan Burnett, set up his practice, Burnett supported the family with her writing. Vivian, nicknamed “Little Calamity,” is thought to have inspired the character of Little Lord Fauntleroy. To save money, Burnett tried her hand at sewing, becoming the boys’ personal seamstress, designing and sewing their clothing. The result of her crafting led to the uniform worn by the fictional little lord, and soon spread as a fashion sensation across Europe and America.

Much of Vivian’s personality and early achievements (he took his first steps at nine months) are attributed to the development of Burnett’s Little Lord character. After the serialization, the book was an immediate hit, with ten thousand copies sold in a week; the English edition also broke through as a best-seller. William Ewart Gladstone, the British prime minister, proclaimed that “the book will have great effect in bringing about added good feeling between the two nations.”

You might also like:

4 Classic Books by Frances Hodgson Burnett

A lawsuit, and successful stage adaptations

While Burnett may be most notably known for The Secret Garden and A Little Princess, the tale of this little lord generated stage and film adaptations, and resulted in a lawsuit. In 1888, Burnett discovered her story had been plagiarized as a play. She sued (and won), and went on to produce her own theatrical version of her book. The play opened May 14, 1888 and was performed in London, France, Boston, and New York City. Decades later, film and television adaptations developed as well, helping ensuring the tale’s legacy.

How the story begins …

The first few opening paragraphs from chapter one of the charming story are as follows:

Cedric himself knew nothing whatever about it. It had never been even mentioned to him. He knew that his papa had been an Englishman, because his mamma had told him so; but then his papa had died when he was so little a boy that he could not remember very much about him, except that he was big, and had blue eyes and a long mustache, and that it was a splendid thing to be carried around the room on his shoulder. Since his papa’s death, Cedric had found out that it was best not to talk to his mamma about him. When his father was ill, Cedric had been sent away, and when he had returned, everything was over; and his mother, who had been very ill, too, was only just beginning to sit in her chair by the window. She was pale and thin, and all the dimples had gone from her pretty face, and her eyes looked large and mournful, and she was dressed in black.

“Dearest,” said Cedric (his papa had called her that always, and so the little boy had learned to say it),—“dearest, is my papa better?”

He felt her arms tremble, and so he turned his curly head and looked in her face. There was something in it that made him feel that he was going to cry.

“Dearest,” he said, “is he well?”

Then suddenly his loving little heart told him that he’d better put both his arms around her neck and kiss her again and again, and keep his soft cheek close to hers; and he did so, and she laid her face on his shoulder and cried bitterly, holding him as if she could never let him go again.

“Yes, he is well,” she sobbed; “he is quite, quite well, but we—we have no one left but each other. No one at all.”

Then, little as he was, he understood that his big, handsome young papa would not come back any more; that he was dead, as he had heard of other people being, although he could not comprehend exactly what strange thing had brought all this sadness about.

Frances Hodgson Burnett’s books on Amazon

More about Little Lord Fauntleroy by Frances Hodgson Burnett

Wikipedia

Review on American Heritage

Full text version on Project Gutenburg

Reader discussion on Goodreads

1936 film adaptation of Little Lord Fauntleroy

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Little Lord Fauntleroy by Frances Hodgson Burnett appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 12, 2018

4 Noted Women Authors as World War I Nurses & Relief Workers

What writers like to do most is to write — ideally in a quiet place, and most often, by themselves. So what motivated these four authors — Edith Wharton, Agatha Christie, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, and Enid Bagnold — to leave their comfortable homes and writing desks, and get involved in war efforts, as nurses and refugee and relief workers?

Each of them, two Brits and two Americans, has a unique story of their involvement in World War I, in Britain and France. At right, the young Enid Bagnold as a Volunteer Aid Detachment nurse.

Edith Wharton: Heroine of war refugees

Edith Wharton (1862 – 1937) was a wealthy heiress and a product of New York high society, never wanting for anything — except perhaps happiness. She was nonetheless socially conscious and became more of an observer of the upper crust than an adherent to it.

After her divorce from Teddy Wharton in 1913, Wharton moved to France, which was on the brink of entering World War I. Upon the outbreak of the war, she immediately plunged into relief work. Among her accomplishments were employing skilled 90 women who had been thrown out of work; feeding and housing hundreds of child refugees, establishing hostels for other refugees; and assisting wounded soldiers and struggling families.

Edith Wharton with WWI soldiers (photo: edithwharton.org)

She wrote: “There is hardly a form of human misery that has not come our way and wrung our hearts with the longing to do more and give more.” An account of some of her expeiences, My Work Among the Women Workers of Paris, was published in the November 28, 1915 edition of The New York Times.

For her war relief efforts, Wharton received one of France’s highest honors, the Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Belgium named her a Chevalier of the Order of Leopold.

For all her compassion for war refugees, wounded soldiers, and orphaned children, Edith Wharton wasn’t perfect and made no secret of her antisemitism. It’s hard to square those two sides of her, though it’s apparently true that they coexisted in one talented, energetic, and complicated woman.

Agatha Christie: Volunteer nurse

Soon after Agatha Christie (1890 – 1976) married an officer in the the Britain’s Royal Flying Corps, her new husband was deployed. She, too, joined in the efforts in 1914. While Archie Christie battled German forces, Agatha worked as a volunteer nurse in the VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment). She clocked in more than 3,000 hours of unpaid work assisting physicians and apothecaries. serving in these capacities until 1918.

Her work encompassed attending operations and amputations. It was grueling work, but she was told by a fellow nurse: “Everything in life one gets used to and if you can last it out, you’ll have no trouble.”

It’s not a stretch to speculate that Agatha Christie’s work with the wounded (both in body and spirit) as a World War I nurse informed some of the emotional detail of physical violence, death and trauma that ran through her mysteries and thrillers. But it’s interesting to note that her plot lines avoided blood and gore; death was cerebral and sometimes artful. She seemed to prefer “clean” deaths by poisoning. Some of her knowledge of poisons may have come from her training in the apothecary arts.

Agatha Christie didn’t wish to relive her World War I experiences to any great extent. One can speculate that it was a traumatic time, but these were also the years in which she was involved with Archie, whose existence she preferred not to address after their divorce.

Dorothy Canfield Fisher: Relief worker

By the time World War I broke out, Vermont-based novelist and educator Dorothy Canfield Fisher (1879 – 1958) had long been affiliated with French issues. In a 1916 letter to a friend she wrote that she and her husband “have been feeling more and more dissatisfied with what we are doing to help out in the war, and that we have decided to do further.”

Upon the outbreak of World War I, the Fishers embarked for France with their children to participate in relief work. To assist refugee children, she established the Bidart Home for Children, and organized an effort to print books in Braille for blinded combat veterans.

Fisher’s husband served in the American Voluntary Ambulance Corps in France at this time. In February of 1919, Red Cross Magazine described her wartime activities: “She took a family of refugee children under her charge to the Pyrenees; she helped establish two hospitals for children under the Red Cross, one specially devoted to tuberculous children. Her ardent activities included a home for the children of munition workers near Paris.”

The Fishers returned to the U.S. after the war, and Dorothy Fisher spearheaded the U.S. committee that would lead to the pardoning of conscientious objectors in 1921. She also helped create channels for assistance to Jewish immigrants. In addition to her literary legacy, for which she’s more respected than famous, Fisher much good with her war relief efforts. However, her legacy has come under scrutiny; some allege that she was involved in Vermont’s eugenics movement. The jury is still out on this one; read more about this controversy.

Enid Bagnold: Another volunteer nurse and chronicler

During World War I, Enid Bagnold (1889 – 1981) was a member of the British Women’s Services. She served for about a year and a half in the V.A.D. (Voluntary Aid Detachment) as a nurse’s aide, much her countrywoman, Agatha Christie, did around the same time. Her early books, A Diary Without Dates (1917), a memoir, and The Happy Foreigner (1920), a novel, reflect upon her experiences in The Great War.

Her duties were to attend to the non-medical needs of wounded British soldiers recovering from wounds in the Royal Herbert Hospital, just a few miles southeast of London. Some of the injuries she witnessed were absolutely horrific. A Diary Without Dates was written almost as a dreamlike prose-poem, portraying the suffering of soldiers, many of whom faced mutilation, wrenching pain, and death. Thus, it became a timeless commentary on the traumas of war.

Her negative commentary on the doctors and nurses she worked with led to her dismissal. She also depicted visitors as voyeurs whose charitable acts served to bolster themselves rather than soothe the suffering troops.

Later, this crusty author would become best known for the 1935 children’s novel National Velvet and the 1955 stage play The Chalk Garden.

The post 4 Noted Women Authors as World War I Nurses & Relief Workers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 11, 2018

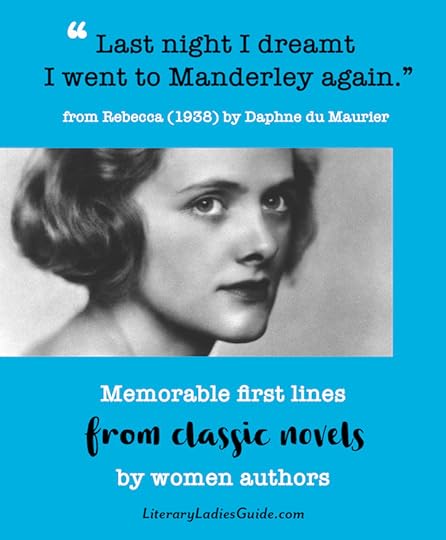

Memorable First Lines from Classic Novels by Women Authors

There are lots of wonderful novels that don’t grab you with the first sentence (or even the first paragraph or two), but when a book’s first line is great, that bodes well for the story ahead. Here are some memorable first lines from classic novels by women authors. What have we left out? Let us know in the comments below and we’ll add more.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife. — Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice (1813)

You will rejoice to hear that no disaster has accompanied the commencement of an enterprise which you have regarded with such evil forebodings. — Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (1818)

In the first place, Cranford is in possession of the Amazons; all the holders of houses, above a certain rent, are women. —Elizabeth Gaskell, Cranford (1853)

“Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents,” grumbled Jo, lying on the rug. — Louisa May Alcott, Little Women (1868)

Miss Brooke had that kind of beauty which seems to be thrown into relief by poor dress. — George Eliot, Middlemarch (1871)

I had the story, bit by bit, from various people, and, as generally happens in such cases, each time it was a different story. — Edith Wharton, Ethan Frome (1911)

When Mary Lennox was sent to Misselthwaite Manor to live with her uncle everybody said she was the most disagreeable-looking child ever seen.” — Francis Hodgson Burnett, The Secret Garden (1911)

One January day, thirty years ago, the little town of Hanover, anchored on a windy Nebraska tableland, was trying not to be blown away. — Willa Cather, O Pioneers! (1913)

Scarlett O’Hara was not beautiful, but men seldom realized it when caught by her charms as the Tarelton twins were. — Margaret Mitchell, Gone With the Wind (1936)

Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board. — Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. — Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca (1938)

I write this sitting in the kitchen sink. — Dodie Smith, I Capture the Castle (1948)

What she liked was candy buttons, and books, and painted music (deep blue, or delicate silver) and the west sky, so altering, viewed from the steps of the back porch; and dandelions. — Gwendolyn Brooks, Maud Martha (1953)

It was a queer sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York. — Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar (1963)

The post Memorable First Lines from Classic Novels by Women Authors appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 9, 2018

The Battle of The Villa Fiorita by Rumer Godden (1963)

In The Battle of the Villa Fiorita, a 1963 novel by Rumer Godden, this prolific author delves into a universal dilemma — does a mother have the right to pursue love, or should she set those needs aside for the sake of her children? This story, which centers on Fanny Clavering and her youngest children, Hugh and Caddie, explores this theme. When the children learn that their mother has run off with a new and enticing man, they begin their quest which culminates in the titled “battle.”

Looking at love, infidelity, and divorce through the eyes of adolescents gives this story its charm, and Rumer Godden, in her usual, skillful way, creates characters about whose fate the reader grows to care about. Her evocative descriptions of the English countryside and the Villa Fiorita on Lake Guarda in Italy demonstrate her talent at evoking a sense of place, something she became famous for in her India novels.

ThoughThe Battle of the Villa Fiorita isn’t as well known as many of Godden’s works, it shares a common trait with a number of her other novels — it was made into a film. The film of the same name was released two years later, in 1965. Rumer Godden’s new releases, which came at a regular clip, were generally loved by readers and reviewed kindly by critics. This review from the time of its release in 1963 is no exception.

Two children trying to save a broken marriage

From the original review of The Battle of The Villa Fiorita by Rumer Godden, The Shiner (Texas) Gazette, October 1963: This charming novel is about two English children who pick up the pieces of a broken marriage.

The children are Hugh Clavering, just turned 14, and his sister Caddie, 11. They have been brought up in one of those polite, semi-suburban, upper-middle class English villages where all the women seem to be dressed in tweeds, sweaters, and strings of pearls. This elegantly humdrum scene is chosen as the location of a movie, brining in strangers and the air of another world.

The children’s mother, Fanny Clavering, bored with her impeccable but somewhat stuffy husband, is swept off her feet by a glamorous movie director, Rob Quillet.

Fanny gives her husband grounds for divorce, of which he promptly avails himself. And she in turn runs off with Rob Quillet to the Villa Fiorita, on the shores of the Lago di Garda, in Italy.

The Battle of the Villa Fiorita by Rumer Godden on Amazon

The winds make Garda less flowery than such other North Italian lakes as Como and Maggiore, but the Villa and its surroundings nevertheless seem a romantic paradise after England — clear skies, warm sun, blue water, Italian food. Fanny and Rob intend to marry as soon as legal technicalities allow.

Meanwhile, the children are settled in a cheerless London flat until their schools open. It is there that Caddie has her inspiration: “Let’s go to this place in Italy and fetch her.” Escaping from their father, Hugh and Caddie make their way across Europe by themselves.

Young as they are, they are self-reliant and resourceful. Caddie finances the trip by selling her most cherished possession, a pony. Thus they have some money, but a lot of it is in the form of a single 10,000 lire note, which they cannot change at the refreshment counters.

See also: Black Narcissus by Rumer Godden

Dirty, hungry, weary from the valiant journey, they arrive at last at the gates of the Villa Fiorita. The “battle” then begins. Rob Quillet is a forceful character as well as an attractive one. He is very much in love with Fanny — as she is with him — and he is by no means inclined to let the children take her away.

There are other characters too — among them Pia, Rob’s half-Italian daughter by a previous marriage, who is about the age of the English children but with an amusing Continental veneer of sophistication. And there are the earthy Italian servants.

Here is a book set in fairytale surroundings, with real suspense and conflict among characters who are all vivid and likable human beings.

More about The Battle of The Villa Fiorita by Rumer Godden

Reader discussion on Goodreads

1965 film version of The Battle of The Villa Fiorita

Review on The Literary Sisters

Review on Desperate Reader

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Battle of The Villa Fiorita by Rumer Godden (1963) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 8, 2018

“Paul’s Case: A Study in Temperament” by Willa Cather (1905)

“Paul’s Case: A Study in Temperament” is a short story by Willa Cather, first published in McClure’s Magazine in 1905. That year, it also appeared in a collection of Cather’s stories, The Troll Garden. This analysis of “Paul’s Case” is by Sarah Wyman, Associate Professor of English at SUNY-New Paltz:

You probably know someone who reminds you of Paul, someone who does not seem to fit in with others in society. Paul’s mannerisms are tense and nervous. He appears antisocial with his classmates, confrontational with his teachers, and emotionally estranged from his family.

A departure from male gender constructs

The early twentieth-century middle class Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania community in which he lives offers neither inspiration nor role models to whom he can relate. Paul seems detached from the real world, and puts on a show of sorts in order to cope. The narrator describes him in terms that emphasize his sense of drama, “His eyes were remarkable for a certain hysterical brilliancy, and he continually used them in a conscious, theatrical way, peculiarly offensive in a boy.”

The text suggests a degree of anxiety, as Paul veers from typical male gender constructs. Hysterical, from hyster (womb or uterus), for example, refers to an explicitly female condition, a diagnosis that ties illness or abnormality to gender.

“Paul’s Case” appears as a short story in

The Troll Garden and Selected Stories (1905)

A contrast between home life and the world of theater

Cather builds the major contrast of the story between Paul’s Cordelia Street neighborhood and the transporting realm of the theater. She paints a crushingly dismal picture of the deadened home life Paul cannot abide:

The nearer he approached his house, the more absolutely unequal Paul felt to the sight of it all: his ugly sleeping chamber; the cold bathroom with the grimy zinc tub, the cracked mirror, the dripping spigots; his father, at the top of the stairs, his hairy legs sticking out from his nightshirt, his feet thrust into carpet slippers…. Paul stopped short before the door.

Such a deadened life does not give Paul what he needs. The world of the theater, however, where he takes an after school job, brings Paul great joy and leads him into another dimension where he comes alive.

It was at the theatre and at Carnegie Hall that Paul really lived; the rest was but a sleep and a forgetting. This was Paul’s fairy tale, and it had for him all the allurement of a secret love. The moment he inhaled the gassy, painty, dusty odor behind the scenes, he breathed like a prisoner set free, and felt within him the possibility of doing or saying splendid, brilliant, poetic things. The moment the cracked orchestra beat out the overture from Martha, or jerked at the serenade from Rigoletto, all stupid and ugly things slid from him, and his senses were deliciously, yet delicately fired.

Read the full text of “Paul’s Case”

Even a mediocre orchestra that “beats” and “jerks” out music proves enough to electrify Paul’s sensibilities and transport him to the sustaining world of imagination and sensuality that counters his emotionally impoverished existence. Paul’s mother had died soon after his birth, and his father figures as a terrifying threat. In order to avoid his father’s wrath, Paul carries out a sort of self-burial, hiding in the basement.

When he chooses his method of self-destruction, he refuses his father’s gun but goes for an even more violent, confrontational end with a train. Perhaps Paul selects his sole friend, the actor Charley Edwards, as an alternative father-figure. The matronly opera singer he follows represents Romance for him, not in the figure of an alluring female, but rather a substitute mother figure who might have supplied the nurturing love Paul lacks.

An artist of the self

Paul’s outsider characteristics, coupled with the private performance he stages when he runs away to New York City, make him seem an artist of the self. His escape to the city is carefully “rehearsed” and once there, he sets the stage with material objects, fancy dress and flowers, as though preparing for a performance. In his hotel room, leased with stolen cash, “Everything was quite perfect; he was exactly the kind of boy he had always wanted to be.”

Yet, he is only a failed quasi-artist, one who can take in and appreciate the artificially constructed but cannot create his own life as a sustainable work of art. To him, the world of art museums and concert halls is a means to evade dull reality. Paul cannot distinguish between the power of money (which allows for his escape) and of authentic spiritual transcendence, that which he feels when transported by others’ art, but cannot maintain or generate himself. His moments of creativity — putting on this show, and presenting himself as a dandy throughout the story — fail to generate a lasting sense of belonging or peace.

Oblique reference to gay identity

Many read Paul as a homosexual youth, living in a society that would not allow the expression of his orientation. Willa Cather was a lesbian at a time and in a culture when public acknowledgement of such feelings was taboo. Various textual details point obliquely and overtly to the source of his great fear, that which seems to lurk in the corner for him.

“Paul had done things that were not pretty to watch, he knew” is one expression of some aspect of himself that seems to haunt him. When Cather employs terms such as gay and faggot, ones that carried connotations of homosexuality even in 1905, she underscores this implication. His all-night interactions with the freshman from Yale seem cryptically described as well and may allude to a homosexual encounter.

Throughout the story, Cather uses images of water in all its manifestations from “treacherous waters” to whirling snowflakes, to weave a tight texture of language. The accumulation of watery imagery serves as a sort of metaphorical foreshadowing of the more intense moments of figurative drowning and ultimately, death. Paul had been “drowning” at home: “the tepid waters of Cordelia Street were to close over him finally and forever”; “The memory of successive summers on the front stoop fell upon him like a weight of black water.”

The moment of crisis

The moment of crisis, that which motivates Paul towards his radical action of departure, is revealed in retrospect with a clever inversion of traditional, linear narration. The plot development comes across as fated as a Greek tragedy: “when they had shut him out of the theater and concert hall, when they had taken away his bone, the whole thing was virtually determined.” At the moment of death or oblivion, if you prefer, he summons a vision of the “blue of Adriatic water” again evoking the fated Greek nature of the plot.

Before his demise, Paul buries or drowns a defiant carnation in the snow. The flower could symbolize his originality, his artfulness, his seeking after beauty, all sorts of things. A few readers argue that Paul does not in fact die, but rather achieves a final sense of belonging in the cosmos. This interpretation is up to you.

While Paul is not a particularly likable character, clearly flawed, deeply unhappy, the writer does a tremendous job of bringing us to know him in a few short pages. Although the story purports to be an objective, even clinical “study,” according to the title, the narrator’s tone seems sympathetic. Many readers share a sympathetic attitude towards this frustrated youth as he struggles to make his life a work of art.

— Contributed by Sarah Wyman, Associate Professor of English, SUNY-New Paltz

More about “Paul’s Case”:

Willa Cather Foundation

“Paul’s Case: A Study in Temperament” on Wikipedia

“Paul’s Case: A Study in Temperament” on Goodreads

“Paul’s Case” — a short film starring Eric Roberts (1980)

“Paul’s Case” — a short film starring Eric Roberts (1980)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post “Paul’s Case: A Study in Temperament” by Willa Cather (1905) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 7, 2018

4 Classic Books by Frances Hodgson Burnett: The Secret Garden & More

Frances Hodgson Burnett (1849 – 1924) was a British-American novelist and playwright. Born in Cheetham, England, Burnett emigrated to the U.S. with her mother and siblings when she was in her teens, settling in rural Tennessee. At 19, Burnett started publishing stories in magazines to help support her family.

Over the course of her decades-long writing career, Burnett wrote over fifty books and thirteen plays. While many were forgotten, here are four books by Frances Hodgson Burnett that have become timeless classics:

The Secret Garden

Considered Burnett’s most widely known novel, The Secret Garden was published in 1911, after an original version was first serialized in The American Magazine in 1910. The story follows the journey of Mary Lennox, a sickly and unloved 10-year-old girl born to wealthy British parents in India.

After a cholera epidemic kills her parents, Mary is sent to England to live with her uncle in an isolated, mysterious house. The tale tells of the spoiled and sulky young girl slowly shedding her sour demeanor as she discovers a secret locked-up garden. Soon Mary develops a friendship with a disabled boy named Colin whom she finds hidden in one of the manors bedrooms. The Secret Garden is a tale spun by the power that kindness and love can yield, painting powerful imagery of the damages that neglect and selfishness can produce.

During Burnett’s prolific career, The Secret Garden was a mere footnote among her other works. It wasn’t until after her death in 1924 that the book rose in popularity. It was then that it was marketed as a children’s book. Several film adaptations of the book have been created, including a Japanese anime version and a 40-episode YouTube series titled The Misselthwaite Archives coined after Misselthwaite Manor, the name of the estate Mary moves to in England.

A Little Princess

Published as a novel in 1905, A Little Princess was inspired by Burnett’s 1888 serialized novella Sara Crewe: or, What Happened at Miss Minchin’s. In 1902, Burnett composed a play inspired by the Sara Crewe story, called The Little Un-fairy Princess. Her publisher than asked her to expand the story into a novel with “the things and people that had been left out before.”

The novel was published in 1905 with the full title A Little Princess: Being the Whole Story of Sara Crewe Now Being Told for the First Time. The story begins with young Sara and her father, Captain Ralph Crewe, arriving in London after living abroad in India. Coming from a wealth of riches, Captain Crewe sends Sara to boarding school, believing it will be the best education and route for his daughter. The wealth of her family causes the headmaster of the school, Miss Minchin, to become tainted by jealousy and feign kindness towards Sara, which the young girl sees right through.

Much the opposite of the main character in The Secret Garden, despite her rich upbringing and spoils, Sara is brave, kind, and intelligent, and soon her classmates begin to referring to her as a princess. After receiving devastating news of her father’s death, Sara is left with nothing — which Miss Minchin cruelly uses to her advantage, locking the young girl away in the attic to work off her tuition and debts.

Throughout her ordeals she holds her head high, and remains kind and charitable to those even less fortunate than herself, and knows that whatever her outward circumstances, she is always a princess inside.

Little Lord Fauntleroy

Little Lord Fauntleroy was the first story that put Burnett on the literary map, first published as a serialization in 1885, then as a book in 1886. The story is of a young boy, Cedric Errol, living in poverty in New York City with his widowed mother. One day they receive a visitor with a message that reveals to Cedric and his mother that he is the heir to the Earl of Dorincourt, making him Lord Fauntleroy. The mother and son move to England to embrace their newfound fortune, but soon discover Cedric’s grandfather, the old Earl, is a bitter old man with a lingering distrust towards all.

The story follows the patient,kind boy, and his ability to transform his grouchy old grandfather, which benefits not only the castle but the entire region of the earldom.

The costume worn by Lord Fauntleroy inspired a fad of formal dress wear for middle-class American children. The classic “Fauntleroy suit” was a velvet jacket and matching knee pants, worn with a fancy blouse with a ruffled collar. The character of Cedric is said to be inspired by Burnett’s youngest son, Vivian, and the clothing illustrated in the book inspired by the costumes she tailored for both her sons.

In 1888, Burnett discovered a plagiarized version of her novel had been turned into a play, and successfully sued. She then wrote her own theatrical version of Little Lord Fauntleroy, which opened May 14, 1888 in London, and soon restaged in France, Boston, and New York City.

The Lost Prince

Published in 1915, The Lost Prince is the story of a young boy named Marco Loristan and his father, Stefan. Stefan, a Samavian patriot, is working to overthrow the unfavorable dictatorship in the kingdom. The pair, in exile from Samavia, move to London where Marco strikes up a unique friendship with a street urchin named The Rat.

The two boys imagine fighting for their home country of Samavia and concoct a plan to restore The Lost Prince, a mythical figure who is the rightful heir to rule Samavia. The two embark on a secret mission to travel across Europe to deliver a message to a secret society that “The Lamp is Lighted,” a signal to those who have been stock-piling supplies.

Following a common theme among Burnett’s books, the novel is a classic children’s book highlighting the virtue of self-discipline, earned respect, and parental love and faith in a child’s ability.

More about Frances Hodgson Burnett’s books on this site

Quotes from A Little Princess

Quotes from The Secret Garden

Book Description of A Little Princess

Illustrations from Sara Crewe

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 4 Classic Books by Frances Hodgson Burnett: The Secret Garden & More appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 6, 2018

Emily of New Moon by L.M. Montgomery (1923)

Emily of New Moon by L.M. Montgomery, published in 1923, is the start of a trilogy of novels about Emily Byrd Starr that invites comparison with the beloved Anne of Green Gables series. These books, as is true for many of L.M. Montgomery’s writings, are meant for “children of all ages.”

When Emily’s father dies of consumption (what is now called tuberculosis), she is orphaned. She is sent to live at New Moon Farm to live with her aunts, Elizabeth and Laura Murray (typical literary spinsters) and cousin Jimmy. There she makes friends with Ilse, Perry, and Teddy, each of whom has a dream based on their particular gift. Emily wishes passionately to be a writer; Ilse wants to be a speaker, Perry seems destined to be a politician, and Teddy is a talented artist.

A girl who loves to write

Emily has a conflict with her Aunt Elizabeth, who’s not on board with her desire to write. Each of her friends is also having an issue with a parent. Emily finds an ally in an elderly schoolteacher, who encourages her writing while being a helpful and honest critic.

In terms of personality, Maud Montgomery considered Emily more of a reflection of herself and her own personality than Anne. Like herself, Emily was a loyal and dedicated friend, loved learning, and appreciated nature. Emily of New Moon was followed by Emily Climbs (1925) and Emily’s Quest (1927). The books follow her through her school years into adulthood when she becomes a successful author.

See also: Anne of Green Gables (1908)

Though the Emily series wasn’t as wildly successful as the Anne of Green Gables books, it has had its generations of devoted readers. There’s no greater proof of this than the fact that the books have never been out of print since they were first published! The series of books have also been translated into a number of languages.

Unlike the Anne series, the Emily books haven’t been the subject of numerous film or TV adaptations, though there was a Canadian televised series that aired on CBC from 1998 to 2000. The following 1923 review is typical of the reception to the book — generally favorable, not as wildly so, but inviting comparisons with the more sober, black-haired Emily to her predecessor, Anne.

Maud Montgomery’s tales gently weave in truths about the limited choices for girls and women of the time. Both the Anne and Emily series display Maud Montgomery’s gift for storytelling and sly humor.

Legions of readers have been devoted to Anne, while others prefer the more contained Emily, who is grounded in her passionate ambition to become a writer. The Emily trilogy shows her in the act of writing, living, and breathing writing, and working to improve her craft. That single-minded devotion to the art of writing is a rarity in children’s literature.

Emily of New Moon on Amazon

An original 1923 review of Emily of New Moon

From the original review of Emily of New Moon by L.M. Montgomery in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September, 1923: Anne of Green Gables is still queen of the long line of orphans who have cast their lot with spinsters, built air castles, and in the end won the affection of their frigid benefactors.

Emily of New Moon is almost as delightful a character. And when the author leaves her in the early teens one hopes for another Emily book, just as a few years ago popular demand made Anne grow up.

There isn’t a great deal of originality in Emily of New Moon. Instead of the little red-haired heroine, we have a black-haired one, and in place of amusing incident, where Anne dyed her hated locks green, we have Emily hacking away with the scissors in order to gratify a yearning for bangs.

This book is the old “Once upon a time there was a little girl” sort of story, but the formula appears to have worn well. When the story opens, Emily lives with her father in a little house in the country. The father dies and the child is left to face the proud Murrays, her mother’s people. These relatives never forgave Juliet Murray for marrying a poor newspaperman.

They unbend at funerals, though, and arrive at Emily’s home in their best black satins. No one is anxious for Emily to live with them, so they draw lots for the little girl, and fate sends her to live at New Moon in Blair Water on Prince Edward Island with her Aunt Elizabeth, Aunt Laura, and Cousin Jimmy.

Through loneliness and a natural urge to write, Emily puts all her thoughts into letters to her dead father, which she scribbles on old bills and hides in the garret. In this diary, particularly, the author displays her keen knowledge of a child’s mind. While many of the letters are wistful, showing the young person’s struggle to comprehend grownups, through them all are flashes of humor, and amusing misspellings.

Emily is confident that she is a genius, and the author brings the story to a close with a friendly school teacher giving the young girl a helping hand toward her goal of becoming a famous author.

More about Emily of New Moon by L.M. Montgomery

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Review on Book Snob

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Emily of New Moon by L.M. Montgomery (1923) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 4, 2018

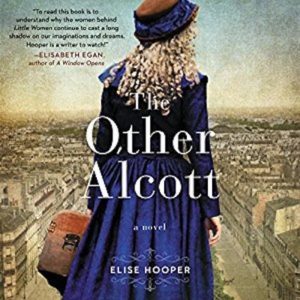

A Conversation with Elise Hooper, Author of The Other Alcott

Many of us grew up reading and re-reading Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. But while most fans cheer on Jo March, based on Louisa herself, Amy March is often the least favorite sister. Now, it’s time to learn the truth about the “real Amy” — Louisa’s sister, May. In The Other Alcott, a captivating work of historical fiction, Elise Hooper gives readers a glimpse into the youngest Alcott’s artistic pursuits and her side of the sibling rivalry. Here’s an in-depth conversation with Elise Hooper, the author of this intriguing work of historical fiction.

Q: Why did you feel compelled to write about May Alcott?

A: I grew up in Massachusetts near Concord and attended drama camp at Orchard House. Along with all of my visits to the Alcott family home, I read many of Louisa May Alcott’s novels, but it was really Little Women that gave shape to my desire to be a writer at a young age, so for my first novel, I wanted to revisit the historical figures who played such a formative role in my own interests.

Many writers have already covered interesting aspects of the Alcotts’ lives so I felt pressure to find a unique path. I researched and researched and experienced a few false starts, but found May’s story largely untold—which is amazing because it’s so compelling! She was such an optimistic figure, despite the many challenges that faced her, and she’s always been overshadowed by her infinitely more famous older sister, making me feel that her story needed to be told. Furthermore, I thought many modern readers would relate to May’s struggle to balance her desire for a career with her search to find love.

Q: Upon reading The Other Alcott, Little Women fans may be surprised at Louisa’s conflicting feelings about the beloved classic. How much of the portrayal of Louisa is true and how much did you fictionalize?

A: To understand Louisa, readers must understand the real circumstances of the Alcotts prior to Little Women being published. Unlike Little Women’s March family who live in a state of genteel poverty, the Alcotts were flat-out impoverished. May’s father, Bronson, refused to accept monetary reward for work, so they relied on the generosity of family members and a small inheritance May’s mother, Abigail, received upon the death of her father.

While struggling to stay afloat financially, the Alcotts moved more than twenty-two times in almost thirty years before eventually settling in Concord, Massachusetts, after Ralph Waldo Emerson offered to support them. Although all of the Alcott sisters grappled with poverty’s challenges, Louisa, in particular, vowed that one day she’d be “rich and famous,” yet for years her various writing endeavors didn’t lead to riches.

It wasn’t until Louisa’s longtime publisher, Mr. Thomas Niles, saw the success of William Taylor Adams’s novels for boys that he proposed a “domestic story” for girls to Louisa. Initially she dismissed the idea, feeling the book would be dull, but eventually Niles wore her down.

More About The Other Alcott by Elise Hooper

Q: Did Louisa really resent the success of Little Women the way she does in The Other Alcott?

A: Louisa had a complicated relationship with Little Women from the start, and I wanted to explore this complexity in my novel. She often called her writing for the juvenile market “rubbish” and declared she only produced it for the money. She became annoyed with the fan mail that focused on marriage and felt “afflicted” by the pressure her publisher placed upon her to marry all of her characters in a “wholesome manner.”

I think most artists can identify with the tension Louisa faced between creating work that satisfied her own need for self-expression and producing work that held the market’s interest. Because the Alcotts depended upon her income, Louisa chose to answer to the market, but I believe she remained uncomfortable with that decision for the rest of her life. All of her journals and letters make her insecurities clear; she is forever tallying up her income in her journal and lamenting writing the juvenile content her audience demanded. Fame and fortune did not live up to her expectations.

But despite her uneasiness with writing for children, it must be noted that she took her young audience seriously and never condescended to her readers. In fact, many of Louisa’s stories tackled fairly adult themes, such as injustice, duty, and self-reliance.

More about how Louisa May Alcott came to write Little Women

Q: Did Louisa really teach herself to write with both hands?

A: Yes, she did! She wanted to be able to write for long stretches of time without stopping, so she simply switched back and forth between her right and left hands while she worked.

Q: In The Other Alcott, Louisa always seems ill. Was her health really that bad?

A: Unfortunately, Louisa was bedeviled by a variety of ailments throughout adulthood. During the American Civil War, she served as a nurse for the Union Army in Washington, D.C., and caught typhoid fever while working at Bellevue Hospital. Although she eventually recovered, doctors used a compound to treat her illness that she later believed gave her mercury poisoning.

Today, doctors suspect Louisa suffered from lupus. But her health woes may have been even more complicated than physical ailments alone. In her documentary Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women, Harriet Reisen speculates that Louisa may have suffered from manic-depressive disorder based on her tendency to immerse herself so completely in her writing that she would neglect to eat and sleep for days at a time. Louisa referred to these manic periods as “falling into a vortex” and would emerge from them depleted and in poor health.

Q: It seems like Bronson Alcott, Louisa and May’s father, could be considered radical for his era. What contributed to his unusual views?

A: Bronson was a unique individual, even by today’s standards. Among other things, he was a philosopher, abolitionist, vegetarian, suffragist, and progressive educator. In fact, today’s kids who love recess can thank Bronson Alcott because he introduced the idea of “physical activity breaks” during the school day well before this was the norm.

When May was a toddler in the early 1840s, he even started a small utopian community in Harvard, Massachusetts, called Fruitlands and moved his family there. Daily life at Fruitlands was a challenge—its residents ate no animal products, bathed in cold water every morning, wore plain tunics and slippers made of linen (to avoid wearing slave-picked cotton), and refused to use any livestock for farming.

Hungry and cold, the community’s residents chafed at the group’s stated goal of being self-reliant. When Bronson started discussing celibacy, Abigail Alcott announced she was leaving and taking Anna, Louisa, Lizzie, and May. The whole Fruitlands experiment fell apart after only seven months, but Bronson stuck with his transcendental philosophy for the rest of his life.

You might also like:

10 Writers Who Were Inspired by Jo March of Little Women

Q: What was transcendentalism and how did this philosophy impact May?

A: Transcendentalism was a philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century rooted in the belief that human nature was inherently good but could be corrupted by society’s institutions, such as organized religion and political parties.

Transcendentalists believed self-reliance and independence to be the ideal state of man. Because of his transcendental philosophy, Bronson Alcott didn’t want to participate in economic systems and refused to receive money in exchange for work.

Luckily for the Alcotts, Mr. Emerson believed Bronson to be a great philosopher and helped the Alcotts in many ways over the years. While May didn’t identify herself as a transcendentalist explicitly, the movement’s beliefs undoubtedly influenced her desire to forge her own path that differed from mainstream society.

Q: Of all of the women artists in The Other Alcott, only Mary Cassatt is a name that most people today recognize. If women began studying art in larger numbers during the late 1800s, why are there not more well-known women artists?

A: While studying art became more accessible to women during the late 1800s, the commercial arena of artistic success still remained mostly closed to women for many reasons. For one, it took years to hone the skills and business connections needed to become a successful painter or sculptor.

Most women did not have decades to develop their talents and build connections with art dealers because they often needed to marry to ensure their own financial well-being. In addition, women lacked access to birth control, and their long-term careers as artists were compromised since marriage ensured periods of creative unproductivity due to childbearing and childrearing.

The most well-known American women artists of the late 1800s — Mary Cassatt and Cecilia Beaux, to name a couple—remained unmarried because they were from wealthy families and possessed the means to be independent. Several of the women in The Other Alcott, including Rosa Bonheur, Anna Klumpke, Anne Whitney, and Adeline Manning, lived in “Boston Marriages” a term used to describe two women living together in a long-term relationship, but these women had the means to eschew traditional marriages and focus on their careers unimpeded by familial responsibilities.

One of the few women who juggled motherhood with her professional career as an artist was Berthe Morisot, a wealthy member of the French aristocracy. She continued to work as an Impressionist painter after the birth of her daughter, Julie, because she could hire help and her husband, also a painter, supported her endeavors. This was unusual. Overall, most women painters found it challenging to maintain professional artistic lives once they married and started families of their own.

A Visit to Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House

Q: What kind of research helped you better understand this family and the era?

A: I started by learning as much about May Alcott and her family as possible. Biographies of the Alcotts are plentiful, especially about Louisa and Bronson, so I immersed myself in secondary sources to get a broad sense of the major milestones in their lives and formative experiences before turning to primary sources. The Alcotts were a family of prolific letter writers and journal keepers, so there was a wide selection of material from which I could experience their individual personalities.

Rereading some of Louisa’s novels, especially Little Women and An Old-Fashioned Girl educated me on Victorian life, from big topics to small details, ranging from Victorian recreational activities to the types of flowers an upper-class family would have on their dining room table.

As I delved deeper into creating my story, I discovered I needed more information on Victorian life, such as steamship and rail travel, so I studied everything from ship menus to railroad timetables. The Seattle Public Library provided countless books about the Impressionists and the Salon, art exhibition catalogs, and out-of-print books about various women artists from the era. I scoured antique maps of Concord, Boston, Rome, London, and Paris and used Google Maps to virtually “walk” some of the neighborhoods that May trod, all while sitting at my computer.

Honestly, writing historical fiction must have been very, very, very time consuming before the Internet came along. Sometimes I stretched the truth, such as when May tries to reach Hunt’s studio during the Great Boston Fire of 1872. In fact, I don’t know where May was during the fire, but Louisa writes about her own experiences watching the conflagration, so I decided to put May in Boston too because the fire significantly impacted her art studies.

The Other Alcott on Amazon

Q: Describe how you wove fictional elements into a real story.

A: When I needed an activity to engage characters, I turned to artifacts and some quintessential Victorian activities and let my imagination loose. For example, how would I set up the moment when May begins to doubt a future with Joshua Bishop? An old photograph by Josiah Johnson Hawes titled Snow Scene on the Northeast Corner of the Boston Common made me realize I could literally put my two characters on a collision course with a sleigh.

When I needed to make May realize how much she cares for Ernest Nieriker, I capitalized on the Victorian bicycle craze and stuck the poor fellow atop a big wheeler, sending him on a bumpy ride. Perhaps one of my favorite historical details came to me as I was researching the Boston Public Gardens and learned the history behind the city’s beloved Swan Boats. Although to the best of my knowledge Louisa never wrote a letter endorsing the widow who wanted to run the family’s Swan Boat business after the death of her husband, it seemed like a cause Louisa would have wholeheartedly embraced, so I worked it into one of her letters to May.

See also: Madeleine B. Stern’s Brilliant Analysis of Little Women

This conversation with Elise Hooper, author of The Other Alcott (2017) is reprinted by permission of the publisher, William Morrow.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post A Conversation with Elise Hooper, Author of The Other Alcott appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 3, 2018

The Other Alcott by Elise Hooper (a novel of May Alcott)

The Other Alcott by Elise Hooper, the author’s debut novel, is a believable imagining of the life of May Alcott. The youngest of the Alcott sisters, she was the inspiration for the character of Amy March in Little Women. May (who, after she married, was known as May Alcott Nieriker) was a talented artist in her own right. As she seeks to establish her own identity apart from the close-knit family, the personality of a dynamic and determined young woman, in many ways ahead of her time, unfolds.

Here is a description of this engaging novel, published in the fall of 2017, reprinted by permission of the publisher, William Morrow:

Many of us grew up knowing the story of the March sisters, heroines of Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. But while most fans cheer on Jo March, based on Louisa herself, Amy March is often the least favorite sister. Now, it’s time to learn the truth about the “real Amy” — Louisa’s sister, May. In The Other Alcott, a captivating work of historical fiction, Elise Hooper gives readers a glimpse into the youngest Alcott’s artistic pursuits and her side of the sibling rivalry.

Author Elise Hooper grew up near the Alcott’s home in Concord, Massachusetts and has been fascinated by the Alcotts (local legends) since her childhood. She remembers visiting Orchard House at age ten and exploring Louisa Alcott’s restored bedroom. There, at a small desk in the corner, was where Louisa had written her classic Little Women in two feverish months.

You might also like:

May Alcott Nieriker: Thoroughly Modern Woman

Hooper recalls backing away from the desk and entering May’s room, the youngest of the Alcott sisters, better known to the world as Amy March from Little Women where pencil sketches of angels and animals adorned the walls. This lesser-known sister, the free spirit, the girl who decorated her walls—was she really the brat she was portrayed to be in her sister’s novel? Elise felt suspicious of Louisa’s account of her. After all, what would our siblings write about us if given the chance?

Almost three decades later as Elise embarked on writing a novel, there was no question what she would write about. Her childhood obsession: the Alcotts. And there was May, the sister she and the rest of us knew very little about. Who was she? What was it like to be portrayed negatively in your sister’s novel for all the world to read?

In The Other Alcott, life for the Alcott family has never been easy, but the most pressing of their financial struggles are eased when Louisa’s Little Women is published. Everyone agrees the novel is charming, but May is struck to the core by the portrayal of selfish, spoiled “Amy March.” Is this what her beloved sister really thinks of her?

See also: A Visit to the Alcott’s Orchard House

(watercolor of the house is by May Alcott)

She begins to question her relationship with her sister as well as her dream to be an artist when her illustrations for Little Women are received poorly by reviewers. This inspires May to embark on a quest to discover her own true identity: as an artist and a woman. Starting with art lessons in Boston and moving on to Rome, London, and Paris, this brave, talented, and determined woman forges a life on her own terms, making her so much more than merely “The Other Alcott.”

The Other Alcott is a distinctive and enjoyable read which will include samples of May Alcott’s original (and panned!) illustrations for Little Women. Here’s just a few of the early artistic efforts from May Alcott, who eventually landed two paintings in the Paris Salon.

About the author

Although a New Englander by birth (and at heart), Elise Hooper lives with her husband and two young daughters in Seattle, where she teaches history and literature. The Other Alcott is her first novel.

The Other Alcott on Amazon

Reviews of The Other Alcott

“Hooper is especially good at depicting the complicated blend of devotion and jealousy so common among siblings… a lively, entertaining read.” — Kirkus Reviews

“Elise Hooper’s debut novel, The Other Alcott, is a delightful, moving book about the strength of women, the impetus of creativity and the indelible bond between sisters. If you loved Little Women (or even if you didn’t), this engaging take on the real-life relationship between the Alcott sisters will fascinate and inspire. More than ever, we need books like this – in celebration of a woman overlooked by history, one whose story helps shed light on our own contemporary search for love, identity and meaning.” — Tara Conklin, New York Times bestselling author of The House Girl

“With its globetrotting, sibling rivalry, old-fashioned courtship, art world intrigue and one very difficult choice, Elise Hooper’s thoroughly modern debut gives a fresh take on one of literature’s most beloved families. To read this book is to understand why the women behind Little Women continue to cast a long shadow our imaginations and dreams. Hooper is a writer to watch!” — Elisabeth Egan, author of A Window Opens

“In The Other Alcott, Elise Hooper has crafted a sweeping and deeply personal tale of a young woman’s struggle to emerge out of her famous sister’s shadow and define herself as an artist and an independent adventurer. You will never look at Little Women or the Alcott family the same way again.” — Laurie Lico Albanese, author of Stolen Beauty

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Other Alcott by Elise Hooper (a novel of May Alcott) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

February 2, 2018

6 Classic African-American Women Authors You Should Know More About

Historically, it was challenge enough for women to become published authors, and until the 1970s or so, this was especially true for African-American women writers facing the dual struggle of race and gender bias. Somewhat of a turning point came during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, during which time talented women found a more supportive and nurturing community. Here are 6 classic African-American women authors, from the Harlem Renaissance era through midcentury (and a bit beyond) worth getting to know — and reading.

Lorraine Hansberry (1930 – 1965) is best known for A Raisin in the Sun, the first play to be written by an African-American woman that was brought to Broadway. She also wrote political essays and worked for the African-American magazine Freedom. Hansberry was a part of and wrote for the Daughters of Bilitis’ magazine The Ladder.

Her insightful commentary on social and race issues in her writings made her stand out and impacted the world of arts and entertainment and beyond. Her autobiography, To Be Young, Gifted and Black, was also quite influential. Though she died quite young at the age of 34, what Hansberry accomplished was impressive. A Raisin in the Sun is a classic of the American stage and is produced in revival on a regular basis. It was also made into the critically acclaimed film of the same name.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917 – 2000) was an American poet whose works included sonnets and ballads as well as blues rhythm in free verse. She also created lyrical poems reflecting African-American life. Her output encompassed more than twenty books in her lifetime, including children’s books.

Born in Topeka, Kansas, Brooks moved with her family to Chicago during the Great Migration. She started reading classic authors and poets when she was young and had her first poem was published in a children’s magazine when she was 13 years old. Her experiences of racial bias informed her views on race, and eventually influenced her work as a writer. Gwendolyn Brooks won a multitude of awards for her work; she was the first African-American woman to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize.

More about Gwendolyn Brooks

Biography

Quotes on Writing and Life

5 Things to Love About Gwendolyn Brooks

The Poet as Working Mother

Zora Neale Hurston (1891 – 1959), with her determined intelligence and humor, quickly became a big name in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. She had a dual career as a writer (producing novels, short stories, plays, and essays) and as an anthropologist.

Zora was the first black student at Barnard College, the women’s college connected with Columbia. There she studied with the noted anthropologist Franz Boas, who recognized her talent for storytelling and her abiding interest in black cultures of the American South and Caribbean.

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) is her best known work, and has become something of a feminist classic, with the heroine of the story searching for independence, identity, and happiness. Despite Zora’s great talent and drive, she was largely forgotten by the time she died in 1960, alone, broke, and ill. It’s fortunate that her life, legacy, and work has been revived to enjoy and study.

More about Zora Neale Hurston

Biography

Quotes and Life Lessons

What White Publishers Won’t Print

A 1934 Interview

5 Quotes from “How it Feels to Be Colored Me”

Nella Larsen (1891 – 1964) may not have produced a large body of writing, but is considered one of the most influential voices of the Harlem Renaissance. She went on to be the first black woman to graduate from library school and to receive the Guggenheim Fellowship for creative writing. When not writing, she worked as a nurse (at the Tuskegee Institute) and a children’s librarian.

As a mixed-race woman whose background included starkly different cultures, the theme of her life, and in effect, her work, was a sense of never belonging — not to any community, nor even to an immediate family. In Nella Larsen’s modest body of work are two short, exquisite novels that have found a new audience today. Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929) are eminently readable and fascinating snapshots of the stringent racial lines of 1920s America.

More about Nella Larsen

Biography

Insightful Quotes from Passing by Nella Larsen

Quotes from Quicksand and Others by Nella Larsen

Passing (1929): An Introduction

Ann Petry (1908 – 1997) was the first African-American woman to produce a book (The Street) whose sales topped one million (ultimately it would sell a million and a half copies). Though she was encouraged her to write while growing up, Ann went to pharmacy college and received a degree during the Depression, when pursuing a practical profession was a must. She followed in her father’s footsteps to become a pharmacist in the family drugstore.

She was always an avid reader who was particularly taken with Louisa May Alcott’s Jo March as a fictional heroine and role model for her literary aspirations. Though none of her subsequent works sold in the sheer volume of The Street, nor achieved its notoriety, Ann Petry remained a respected voice in literature.

More about Ann Petry

Biography

Ann Petry Talks of Race Problems

Ann Petry obituary (1997)

6 Interesting Facts About Ann Petry

Dorothy West (1907 – 1998) started writing as a child and began receiving accolades and awards while still in her teens. She found community in the city, West became part of the Harlem Renaissance and was known by her contemporaries as “The Kid.” Her writing is admired for the detail and examinations of African-American community in the areas of gender, class, and social issues.

Dorothy founded the literary magazine Challenge in 1934, and New Challenge in 1937. Though she continued to write short fiction, her first novel, The Living is Easy, wasn’t published until 1948. Then, there was a gap of many years until her second novel, The Wedding, was published in 1995. She was 85 years old. In 1998, it was adapted into a television mini-series, produced by Oprah Winfrey.

More about Dorothy West

Biography

The Wedding: A mini-series (1998)

Dorothy West Quotes on Identity and Experience

MORE CLASSIC AFRICAN-AMERICAN

AUTHORS ON THIS SITE

Octavia Butler

Jessie Redmon Fauset

Audre Lorde

The post 6 Classic African-American Women Authors You Should Know More About appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.