Nava Atlas's Blog, page 89

March 19, 2018

Comedy, American Style by Jesse Redmon Fauset (1933)

Comedy, American Style by Jesse Redmon Fauset (1882 – 1961) was the last novel by this influential author, poet, and editor associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Published in 1933, the title is completely ironic; this story is, if anything, more of a tragedy.

In this story, Jessie Fauset explores themes of racial identity, self-hatred, and the concept of “passing” in the deeply biased American culture. The main character, Olivia Cary, is domineering mother who wants her children to pass as white, which leads to to dire consequences for the family.

When it was first published, reviews of Comedy, American Style were mixed. Some critics thought Fauset’s writing style rather prissy. Olivia was compared with tragic heroines like Lady Macbeth and Emma Bovary. There were many positive views, as well. Comedy offered, some thought, a more realistic view of the concept of “passing” than Imitation of Life (a big bestseller that same year, 1933) by Fannie Hurst, a Jewish author.

Here’s an original review that was published in a leading black newspaper in 1933, the year in which the book came out. It’s a fascinating perspective on the work of an author being rediscovered decades after her virtual disappearance from the literary scene.

A 1933 review of Comedy, American Style

From The Pittsburgh Courier, December 9, 1933: Jessie Fauset, who, without a doubt, has carved for herself a niche in American literature, scores with this absorbing novel about the eternal color question — inter-racial and intra-racial — in America. Being a woman of color herself, and having lived in the “land of the free and the home of the brave” practically all her life, Miss Fauset is thoroughly qualified to handle this question of color prejudice found in a class of [black][ society little known to white America.

When Olivia was deeply hurt in her childhood by two incidents, she definitely decided that after she grew up she would “pass” over into the white world. So intent was she on being white that for a long time she preferred the company of common white mill hands and drug clerks to that of refined, educated, and cultured people of color.

But Olivia was a reasoning person, and thought that if she could not marry a truly white man of good standing, culture, and education, she would marry one who apparently was white and they could lose their identity, and though their children, go on over to the other side.

You might also like: Plum Bun by Jessie Redmon Fauset

With that in mind, Olivia accepts the attentions of Christopher Cary, a promising young doctor, who was as white as she in color, and later married him. She married him without love, only because he was white in color.

Olivia felt absolutely sure that her children would be “white.” Had not her own brother and sister of her mother’s second marriage been white? What had she to fear on this score?

When her first two children were born she rejoiced to know that she had been right. Their whiteness was an assured fact. “Olivia had been positive that all of her Negro blood had been wrought by her white blood to a consistency as pure … as limpid as that which flowed through the heart of the whitest woman she knew.”

She thought that she had lost through her children the sum total of that black blood she so hated. But she rejoiced too soon, reckoning without Mother Nature, who figuratively laughed in glee when Olivia’s third baby was born.

Comedy, American Style by Jessie Redmon Fauset on Amazon

Olivia’s intense hatred of all people of color, her sinister influence over her family, and the resulting tragedy make this book a thoroughly human tale well worth reading. The theme used affords excellent material for the plot, which is developed skillfully and brought to a logical conclusion.

The characterizations are good. There is Olivia Cary with her warped nature, arousing contempt with her passion to be white; Phebe Grant, with her womanly sweetness and understanding; Marise Davies, the beautiful brown girl, whose dancing feet carry her to the heights of acclaim; Oliver Cary, handsome, sensitive, talented brown boy, whose accident of color earns for him his mother’s hatred; Teresa Cary, beautiful, though weak and vacillating, an easy prey for her domineering mother.

Learn more about Jessie Redmon Fauset

More about Comedy, American Style by Jessie Redmon Fauset

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Read for free on Internet Archive

The Forgotten Work of Jessie Redmon Fauset

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Comedy, American Style by Jesse Redmon Fauset (1933) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 18, 2018

Classic African-American Women Authors on Literary Ladies Guide

Here’s an introduction to classic African-American women authors. Fortunately, there are many more women of color writing and being published today who will join the ranks of classic authors. Those listed below are, like all the Literary Ladies on this site, are those who have passed on. You’ll find a listing of the biographies, books, quotes, poetry, and more, presented on this site.

This page will continue to grow as more posts are added about these writers as well as biographies of other classic African-American women authors. In addition to information about the individual authors listed below, you might also enjoy:

Renaissance Women: 12 Female Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

10 Pioneering African-American Women Journalists

Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou (1928 – 2014) was an American author, actress, screenwriter, dancer, poet, and civil rights activist. During her lifetime, she published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, and several books of poetry. She received dozens of awards and more than thirty honorary doctoral degrees.

Books by Maya Angelou on this site

The Heart of a Woman

More about Maya Angelou on this site

Biography

Maya Angelou Quotes To Live By

10 Fascinating Facts About Maya Angelou

Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917 – 2000) was an American poet whose works included sonnets and ballads as well as blues rhythm in free verse. She also created lyrical poems, some of which were book-length.

Books by Gwendolyn Brooks on this site

Annie Allen (1949)

The Bean Eaters (1960)

Primer for Blacks (1980)

More about Gwendolyn Brooks on this site

Biography

Quotes on Writing and Life

5 Things to Love About Gwendolyn Brooks

The Poet as Working Mother

Poetic Quotes from Maud Martha

A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun (biography)

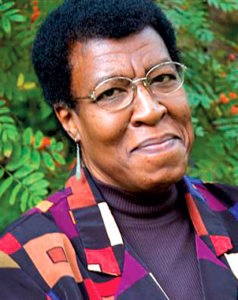

Octavia Butler

Octavia Estelle Butler (1947 – 2006) was an American author of science fiction. In the white male-dominated genre of science fiction, she broke ground not only as a woman, but as an African-American. Her otherworldly novels and stories grapple with issues of race, class, and gender.

Books by Octavia Butler on this site

Adulthood Rites (1988)

Parable of the Sower (1993)

Parable of the Talents (1998)

More about Octavia Butler on this site

Biography

Octavia Butler Quotes on Writing and Human Nature

12 Fast Facts About Octavia Butler

Jessie Redmon Fauset

Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882 – 1961) was an American editor, poet, essayist, and novelist who was deeply involved with the Harlem Renaissance literary movement. In 1919 became the literary editor of the NAACP magazine The Crisis, and in that capacity helped launch the careers of a number of significant writers.

Books by Jessie Redmon Fauset on this site

Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral (1928)

More about Jessie Redmon Fauset on this site

Biography

6 Poems by Jessie Redmon Fauset

Literary Midwife: Jessie Redmon Fauset

Quotes by Jessie Redmon Fauset

Lorraine Hansberry

Lorraine Hansberry (1930 – 1965) was an American playwright and author. Her play, A Raisin in the Sun, was the first play written by an African-American woman to be brought to broadway. At the age of 29, Hansberry became the youngest American and the first African-American playwright to win the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for Best Play.

More about Lorraine Hansberry on this site

Biography

Quotes by Lorraine Hansberry, Author of A Raisin in the Sun

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston (1891 – 1960) was an African-American novelist, memoirist, and folklorist. With her determined intelligence and bold personality, she quickly became a big name in the Harlem Renaissance movement of the 1920s. She and her work were all but forgotten by the time of her death, though interest in her work has blossomed through the efforts of Alice Walker.

Books by Zora Neale Hurston on this site

Mules and Men (1935)

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

Tell My Horse (1938)

Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939)

I Love Myself When I Am Laughing (posthumous anthology, 1979)

Every Tongue Got to Confess (posthumous anthology, 2001)

More about Zora Neale Hurston on this site

Zora Neale Hurston Quotes and Life Lessons

5 Quotes from “How it Feels to Be Colored Me”

“Crazy for This Democracy”

Quotes from Their Eyes Were Watching God

What White Publishers Won’t Print

1934 Interview with Zora Neale Hurston

Fannie Hurst and Zora Neale Hurston, a Literary Friendship

Zora and Money Matters

Zora Neale Hurston’s “Sweat”: An Ecofeminist Master Class in Dialect and Symbolism

Zora on Books, Publishing, and Publishers

Nella Larsen

Nella Larsen (1891 – 1964) was an American author associated with the Harlem Renaissance movement. Her body of writing was modest, but she was considered a respected voice of her time. Recently, there has been renewed interest in Larsen, the first African-American woman to graduate from library school and to receive the Guggenheim Fellowship for creative writing.

Books by Nella Larsen on this site

Quicksand (1928)

Passing (1929)

More about Nella Larsen on this site

Insightful Quotes from Passing by Nella Larsen

Quotes from Quicksand and Others by Nella Larsen

Passing (1929): An Introduction

In Search of Nella Larsen by George Hutchinson

Audre Lorde

Audre Geraldine Lorde (1934 – 1992) was a self-identified “black lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” who grew up in New York City. She used her platform as a writer to spread ideas and experiences about the intersecting oppressions faced by many, especially women of color.

More about Audre Lorde on this site

Biography

Poetry & Politics: Quotes by Audre Lorde

5 Reasons to Love Audre Lorde

Five Politically-Inspired Quotes by Audre Lorde

10 Thought-Provoking Quotes from Sister Outsider

Ann Petry

Ann Petry (1908 – 1997) was the first African-American woman to produce a book whose sales topped one million. Her book, The Street, ended up selling a million and a half copies.

Books by Ann Petry on this site

The Street (1946)

Country Place (1947)

The Narrows (1953)

More about Ann Petry on this site

Ann Petry Talks of Race Problems

Ann Petry obituary (1997)

6 Interesting Facts About Ann Petry

Quotes from The Street by Ann Petry

Ann Petry, Author of ‘The Street,’ Dies At 88

Dorothy West

Dorothy West (1907 – 1998) was an American author and editor associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Though her body of work wasn’t large, it was well respected. She was known for her depictions of upper-class African-American families and communities.

Books by Dorothy West on this site

The Wedding

The Richer, The Poorer

More about Dorothy West on this site

Biography

Dorothy West Quotes on Identity and Experience

The Wedding: A mini-series (1998)

Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley (ca 1753 – December 5, 1784) was born in Senegal / Gambia, Africa. She was America’s first African-American poet and one of the first women to be published in colonial America. She was also the first slave in the U.S. to have a book of poetry published.

More about Phillis Wheatley on this site

Biography

The post Classic African-American Women Authors on Literary Ladies Guide appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 15, 2018

Quicksand by Nella Larsen (1928)

Quicksand by Nella Larsen (1928) was the first novel by this author associated with the Harlem Renaissance. A story with autobiographical elements, it was largely well received, though not a big seller. Helga Crane, the main character, like Nella Larsen, is the mixed-race daughter of a white Danish mother and a black father.

The plot takes her back and forth from Denmark, “Naxos” (a thinly veiled version of the Tuskegee Institute, where Larsen worked briefly), and Harlem. Wherever Helga goes, she fails to find a community in which she can be comfortable with who she is.

Nella Larsen’s fictional young women of mixed race — in this book and in Passing — grapple for a sense of identity and belonging, mirroring her own life. Larsen never felt quite at home in either the European community of her mother, nor in either the black world or the white in the U.S., at a time when the “color line” was strictly drawn.

Quicksand is an appropriate title for the book. Apart from societal conditions over which she has no control, some of the messes that Helga sinks into are of her own making.

Following are portions of two reviews from 1928, the year in which Passing was published. It’s fascinating to view the work from the perspective of that time, rather than the long lens of the decades gone by.

1928 review from The New York Age

This review from the New York Age, an important black newspaper, is dated June 23, 1928:

Quicksand by Nella Larsen is a novel of frustration, which presents a peculiar study in the psychology of her heroine, whose life is a failure though no one’s fails but her ow innate perverseness. Helga Crane was the daughter of a Danish mother and a [black] father, and her temperament alternated between the two different strains, with the disastrous result that she could adopt neither permanently nor even find refuge in a middle of the road course.

Repelling the growing interest of the educator who she discovered too late was the man she really loved, she went to Denmark and disappointed her mother’s family by refusing to marry a Danish artist, who became fascinated by her. Her return to New York opened her eyes too late, for the man she loved had married her friend and proved faithful to his choice.

The incident of her accidental attendance at a religions revival meeting, with its cataclysmic effect, and her hasty marriage to the unlettered preacher, inconsistent as they sound, are made to appear as the inevitable outcome of the emotional conflict within her.

Her submersion into the road of the unwilling mother of numerous progeny, whom she had to rear in primitive surroundings, is invested with a sense of human tragedy.

Quicksand & Passing by Nella Larsen on Amazon

Another 1928 review

This review from the Reading (PA) Times, is dated May 14, 1928:

Here again is the old theme of mixed blood, [black] and Scandinavian this time, with the North, South, Chicago, Harlem, and even Denmark for the backgrounds.

The story has to do with Helga Crane, a daughter of a Danish woman and a nameless [black] man. She suffers the discriminations dealt to Negroes in Chicago and her education and the instincts she inherited from her mother make her feel those abuses more acutely.

At the age of 22 — she is a school teacher then — she revolts and flees. Throughout the book she revolts. Even in the last paragraph, after having borne four children as rapidly as the exigencies of nature permits, she revolts at the idea of bringing children into the world to suffer — and goes about preparing to give birth to the fifth.

The real charm of this book lies in Miss Larsen’s delicate achievement in maintaining for a long time an indefinable, wistful feeling — that feeling of longing and at the same time a conscious realization of the impossibility of obtaining — that is contained in the idea of Helga Crane.

… It runs beautifully and artistically through the maze of realities and artificialities; the prim correctness of the school at Naxos; the mad run of Chicago; the intellectual absurdities of Harlem; the cold gentleness of Copenhagen.

Always [there is] a wistful note of longing, of anxiety of futile searching, of an unconscious desire to balance black and white blood into something that is more tangible than a thing than merely is neither black nor white, of a nervous, fretful search for happiness.

Passing, Larsen’s next novel was published just a year later, in 1929. It’s more tightly plotted and paced, showing the growth of an artist who has mastered her craft. Unfortunately, she virtually disappeared from the literary community not long after.

Interest in Nella Larsen’s work has grown since Passing was reissued in 2001. She has been described as “not only the premier novelist of the Harlem Renaissance, but also an important figure in American modernism.” With the growing interest in Passing as a modern classic, Quicksand has also been rediscovered. The two books have been published in one volume in contemporary editions.

RELATED POSTS

Insightful Quotes from Passing by Nella Larsen

Quotes from Quicksand by Nella Larsen

Passing

(1929): An Introduction

In Search of Nella Larsen by George Hutchinson

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quicksand by Nella Larsen (1928) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Nella Larsen

Nella Larsen (April 13, 1891 – March 30, 1964), born Nellie Walker in Chicago was an American author associated with the Harlem Renaissance movement. Her body of writing was modest, but she was considered a respected voice of her time. She was the first African-American woman to graduate from library school and to receive the Guggenheim Fellowship for creative writing. The theme of her life, and in effect, her work, was a sense of never belonging — not to any community, nor even to an immediate family.

Her mother, Marie Hansen, was a white Danish immigrant; her father, Peter Walker, was likely of mixed race and from the Danish West Indies. He may have died when Nella was quite young. Her mother remarried Peter Larsen, another white Danish immigrant, with whom she had another daughter; Nella took his surname. To be the only non-white member of her family put her in a precarious position at the time. The family moved to a mostly white neighborhood, and thus began a life in which Nella never felt a sense of belonging.

In his review of In Search of Nella Larsen by George Hutchinson, Darryl Pinckney wrote, “as a member of a white immigrant family, she had no entrée into the world of the blues or of the black church. If she could never be white like her mother and sister, neither could she ever be black in quite the same way that Langston Hughes and his characters were black. Hers was a netherworld, unrecognizable historically and too painful to dredge up.”

Education and nursing career

Nella attended Fisk University, a historically all-black college in Nashville, Tennessee in 1907. For the first time, she was part of an all-black community. Not having any real connection with the students, who were primarily from the South, she once again felt out of place and dropped out after a year. She then spent four years in Denmark with relatives.

Upon returning to the U.S. in 1914, Nella enrolled in a nursing school program in New York City. After completing the one-year program, she worked as head nurse at the renowned Tuskegee Institute (Alabama). The poor working conditions, coupled with a disappointment with Tuskegee founder Booker T. Washington’s educational philosophy, made this sojourn short-lived. She returned to New York and resumed work as a nurse.

You might also like: Quicksand by Nella Larsen (1928)

Marriage and divorce

Nella Larsen married Elmer Imes, a physicist, in 1919. He was notable as the second African-American to earn a doctorate in physics. The following year, her first short stories were published. The couple moved to Harlem shortly thereafter. A connection with NAACP notables gave her entrée into the world of the Harlem Renaissance. Their peers and colleagues were highly educated blacks, a cultural elite, and with her lack of formal education and mixed ancestry, Nella once again felt a keen sense of being out of place.

During the marriage, Nella sometimes wrote under the name Nella Larsen Imes. The marriage was not a happy one, and the couple divorced in the early 1930s.

Career as a librarian

In the early 20s, Nella volunteered at the legendary Harlem branch of the New York Public Library, which was a hub of cultural activity. She was encouraged by head librarian Ernestine Rose to get training, and received certification from the NYPL’s own school. Pausing her nursing career, she began working as a librarian on the Lower East Side before returning to the Harlem branch.

1925 was a turning point for Nella. Though she had to take a sabbatical from work for health reasons, she used the time to start her first novel, and made an effort to become more engaged in the cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance.

RELATED POSTS

Insightful Quotes from Passing by Nella Larsen

Quotes from Quicksand by Nella Larsen

Passing

(1929): An Introduction

In Search of Nella Larsen by George Hutchinson

Quicksand and Passing

Quicksand (1928) was her first novel, published in 1928. Though it was well-received critically, its sales were modest. The story was partially autobiographical. Like Larsen, Helga Crane, the main character, is the mixed-race daughter of a white Danish mother and a mixed-race father from the Caribbean. She travels back and forth from Denmark, teaches at “Naxos,” a thinly veiled episode base on Larsen’s Tuskegee experience, and lives in Harlem. Everywhere Helga goes, she never finds a comfortable place for herself.

Passing (1929), her second novel, was also well-received, if not a best-seller. It’s the story of two friends, Irene and Clare, both of mixed race. Both have a mostly white appearance, but Clare has crossed over the color line to live as white, even getting married to a white man who turns out to be a bigot. Irene “passes” when convenient, but lives as black, with her black doctor husband and two sons. The women reunite after an absence of twelve years from their friendship, with dramatic consequences.

Both novels are eminently readable and fascinating snapshots of the stringent racial lines of 1920s America. Though Passing came out just a year after Quicksand, it is a more mature and delicately told story.

Nella Larsen’s stories of young women of mixed race growing up in a prejudiced world, grappling for a sense of identity and belonging, mirrored her own life. Larsen struggled mightily for most of her life, never feeling quite at home in either the European community of her mother, nor back in the United States; neither in the black world or the white at a time when the “color line” was strictly drawn.

Leaving the literary world for good

Nella lived on alimony until her ex-husband’s death in 1942, but subsequently returned to nursing and medical administration. She moved to the Lower East Side, abandoned her literary circles, and never ventured back to Harlem. She struggled with depression, and stopped writing. In the course of her lifetime, her work had been all but forgotten. She died at age 72 in Brooklyn in 1964.

Nella Larsen page on Amazon

A revival of interest

Passing was reissued in 2001. Richard Bernstein, a New York Times book critic, wrote: “reading it and knowing that its author wrote very little after it imparts a sense of loss, giving as it does a glimpse of an original and hugely insightful writer whose literary talent developed no further.”

Fortunately, interest in Nella Larsen’s writings, modest though her body of work was, has grown over the years. Academic interest in race, history, and women’s studies has shed a new light on her work, and has been reconsidered in numerous academic studies. According to The Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Fiction (2011), Nella Larsen is described as “not only the premier novelist of the Harlem Renaissance, but also an important figure in American modernism.”

More about Nella Larsen on this site

Insightful Quotes from Passing by Nella Larsen

Quotes from Quicksand and Others by Nella Larsen

Passing (1929): An Introduction

In Search of Nella Larsen by George Hutchinson

Major Works

Quicksand (1928)

Passing (1929)

The Complete Fiction of Nella Larsen

Biographies about Nella Larsen

In Search of Nella Larsen: A Biography of the Color Line by George Hutchinson

Nella Larsen, Novelist of the Harlem Renaissance: A Woman’s Life Unveiled by Thadious M. Davis

More Information

Wikipedia

Nella Larson on Black History Now

Reader discussion of Larsen’s works on Goodreads

Nella Larsen page on Amazon.com

Visit

Nella Larsen Letters, 1928 – The New York Public Library, New York, NY

Nella Larsen’s Grave – Cypress Hills Cemetary, Brooklyn, NY

Listen Online

Quicksand and Passing on Librivox

Nella Larsen photo by Carl Van Vechten

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Nella Larsen appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 14, 2018

Mary McCarthy

Mary McCarthy (June 21, 1912 – October 25, 1989) was an American novelist, political activist and critic, born in Seattle, Washington. She overcame a difficult childhood to become a woman of strength and determination — and occasional controversy.

She began her writing career as a critic, and gained admiration for her honest observations on culture and politics. In 1942 she published her first novel, The Company She Keeps, about a smart young woman going to college and breaking into New York City social circles.

The Group (1954) was arguably her most popular novel — it sat on the New York Times Bestseller list for two years and was made into a popular film. McCarthy’s novels and stories are part autobiography and part fiction, as she draws on her own experiences, traumas, and successes. That, along with her writing style, made her a respected talent in the writing community.

McCarthy had friends and enemies within literary and activist circles — she was allied with Hannah Arendt, for instance, and was locked in a bitter feud with playwright Lillian Hellman, whom she accused of being an outright liar. She died of lung cancer in New York City in 1989.

Early life and education

McCarthy was orphaned at the age of six when both her parents died in the flu epidemic of 1918. She and her brothers, Kevin, Preston, and Sheridan, were raised in unhappy circumstances by her Catholic father’s parents in Minneapolis, Minnesota. An uncle and aunt also made their childhood miserable.

Fortunately, McCarthy and her siblings were eventually taken in by her maternal grandparents in Seattle. During this time, she studied at Forest Ridge School of the Sacred Heart in Seattle, and Annie Wright Seminary in Tacoma, and went on to graduate from Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1933.

Strong beliefs

McCarthy left the Catholic Church and became an atheist as she became an adult. In New York during the 1930’s, she moved in Communist circles.

As part of the Partisan Review circle and as a contributor to The Nation, The New Republic, Harper’s Magazine, and The New York Review of Books, she grabbed attention as a critic — sometimes a scathing one. During the 1940s and 1950s she was critical of McCarthyism and Communism. She opposed the Vietnam War in the 1960s and covered the Watergate scandal hearings in the 1970s.

She visited Vietnam frequently during the Vietnam War, and after being interviewed after her first trip, she declared on British television that there was not a single documented case of the Viet Cong deliberately killing a South Vietnamese woman or child.

You might also like: 12 Must-Read Collections of Famous Authors’ Letters

Personal life

McCarthy married four times. In 1933 she married Harald Johnsrud, an actor and playwright. Next, McCarthy married well-known writer and critic Edmund Wilson in 1938, after leaving her then-lover Philip Rahy. She and Wilson had a son, Reuel Wilson.

In 1946, she married Bowden Broadwater, employee of the New Yorker. Then, finally, in 1961, McCarthy married career diplomat James R. West.

One of McCarthy’s most noteworthy friendships was with Hannah Arendt. After Arendt’s passing, McCarthy became Arendt’s literary executor from 1976 until her own death in 1989. McCarthy also taught at Bard College from 1946 to 1947, and once again between 1986 and 1989. She also taught a winter semester in 1948 at Sarah Lawrence College.

You might also like: Mary McCarthy Quotes with a Critical Eye

Awards and literary life

In the late 1930’s McCarthy’s debut novel The Company She Keeps recieved critical acclaim for bluntly highlighting the social lives of New York intellectuals of the time.

After building a reputation as a satirist and critic, McCarthy enjoyed popular success when the 1963 edition of her novel The Group remained on the New York Times bestseller list for almost two years. The semi-autobiographical novel noted for its frank look at the lives of young women in the years before second-wave feminism took hold.

Her famous feud with fellow writer Lillian Hellman formed the basis for the play Imaginary Friends by Nora Ephron. The feud had simmered since the late 1930s over ideological differences, McCarthy provoked Hellman in 1979 when she famously said on The Dick Cavett Show: “every word [Hellman] writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the’.”

Hellman responded by filing a $2.5 million libel suit against McCarthy, which ended shortly after Hellman died in 1984, in which McCarthy is quoted saying that she “…hadn’t wanted Hellman to die but, rather, to live so that I could see her lose.”

Mary McCarthy’s books on Amazon

The Group

Considered to be the best-known novel written by McCarthy, The Group was published in 1954. It made the New York Times bestseller list in 1963, and remained there for almost two years.

The book follows the lives of eight young female friends just graduated from Vassar College in 1933. The story is fueled by their struggles with a variety of issues: sexism in the workplace, child-rearing, financial difficulties, family crises, and their intimate relationships. As highly-educated women from affluent backgrounds, they strive to carve out a place for themselves in the male-dominated mid-century world.

The novel was banned in Australia, Italy, and Ireland for “being offensive to public morals.” At the time of its release, men questioned McCarthy’s ability to be a professional writer. Notably, Norman Mailer for The New York Review of Books wrote that, “her book fails as a novel by being good but not nearly good enough … she is simply not a good enough woman to write a major novel.”

Death and legacy

in all, McCarthy wrote some 28 books of fiction and nonfiction and countless articles and essays on numerous subjects. Her Vassar bio (her alma mater) states:

“The breadth of her writing is wide, from drama reviews to the history of art and architecture, from cultural criticism to political analysis and travel observations. She was known for her keen intellect, her wit and courage, and her literary style that was precise, but graceful. From her readers and reviewers, she elicited strong reactions that were frequently negative. She was often referred to as the ‘lady with a switchblade.'”

Mary McCarthy died of lung cancer on October 25, 1989, at NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital in New York City.

See also: Vanity Fair – Vassar, Unzipped

More about Mary McCarthy on this site

Mary McCarthy Quotes with a Critical Eye

Major Works

The Company She Keeps

The Group

Memories of a Catholic Girlhood

The Stones of Florence

Birds of America (1971)

Intellectual Memoirs: New York, 1936-1938

Mask of State: Watergate Portrait

Autobiographies and Biographies

Memoirs of a Catholic Girlhood

Intellectual Memoirs: New York 1936-1938

Seeing Mary Plain: A Life of Mary McCarthy by Frances Kiernan

Writing Dangerously: Mary McCarthy and Her World by Carol Brightman

More Information

Wikipedia

Mary McCarthy Books

Special Collections: Mary McCarthy Online Exhibit

Reader discussion of McCarthy’s books on Goodreads

McCarthy’s Amazon page

Articles, News, Etc.

Remembering Mary McCarthy: A Woman of Intellect and Style

McCarthy’s ‘The Group’ is the Definitive Young Woman’s Sex Narrative

The Paris Review: Mary McCarthy, The Art of Fiction No. 27

Research

McCarthy Archive and Papers –Vassar College

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Mary McCarthy appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

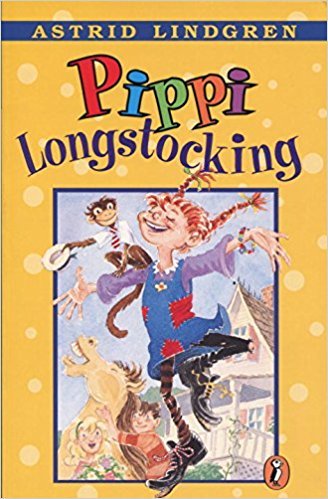

Pippi Longstocking Book Series by Astrid Lindgren

Astrid Lindgren (1907 – 2002) was a Swedish writer of fiction and screenplays, best known for her children’s book series featuring the independent and strong character Pippi Longstocking. As of January 2017, Lindgren was the world’s eighteenth most-translated author, and the fourth most-translated children’s book writer. Her books have sold roughly 144 million copies worldwide.

When her daughter Karin was seven years old and recovering from pneumonia, she asked her mother to tell her a story about “Pippi Longstocking.” From that spark, a literary star was born, ultimately changing Astrid Lindgren’s life forever.

Three years later, stuck in bed rest with an injured leg, Lindgren began to write the stories of Pippi Longstocking for her daughter’s tenth birthday. After an initial rejection, in 1945 Rabén & Sjögren’s published Pippi Longstocking, and the rest is publishing history. Here are the three original books in the Pippi Longstocking series by Astrid Lindgren.

Pippi Longstocking

Published in 1945 by Rabén & Sjögren, translations of the first Pippi Longstocking book have been published in more than 40 languages. The first U.S. edition was published in 1950 by The Viking Press. In 2002 the Norwegian Nobel Institute listed the novel as one of the “Top 100 Works of World Literature.”

The book focuses on the experiences and adventures of Pippi Langstrump, a nine-year-old pigtailed redhead with superhuman strength. Her mother died when she was a baby, and her father, a sea captain, has seemingly vanished at sea. She moves into a big house known as Villa Villekulla, located in a little Swedish village, with her pet monkey Mr. Nilsson, a suitcase filled with pieces of gold, and her unnamed pet horse.

Pippi can do anything she likes — stay up as late as she wants, lift a horse up in the air, buy pounds and pounds of candy. She uses her amazing powers to the good — usually. Children of all ages have fallen in love with this eccentric character from the moment she burst on the literary scene.

See Pippi Longstocking on Amazon.

Pippi Goes On Board

Published in 1946 as the sequel to the original, Pippi Goes On Board follows the adventures of Pippi, who’s been treating her friends Tommy and Annika to wild adventures — like buying and eating seventy-two pounds of candy, and sailing off to an island in the middle of a lake to see what it’s like to be shipwrecked. But then Pippi’s long lost father returns, and she might have to leave Villa Villekulla.

See Pippi Goes on Board on Amazon.

Pippi in the South Seas

Pippi in the South Seas, published in 1948, is a sequel to Pippi Longstocking and Pippi Goes on Board. In this book, a few of Pippi’s newer experiences include her warding off a snobbish tourist who believes Villa Villekulla is for sale and dismisses her as ugly and ridiculous.

She also soon receives word from her father, a sea captain who had seemingly vanished earlier, inviting her to a tropical island inhabited by natives over which he now reigns as king. Pippi and her friends sail to her father’s island kingdom, where they become acquainted with the natives living there, Pippi being hailed as “Princess Pippilotta.”

See Pippi in the South Seas on Amazon.

More on Pippi Longstocking

The Guardian: The naughtiest girl in the world

The Paris Review: Astrid Lindgren, the Gutsy Creator of Pippi Longstocking

Independent: Long live Pippi Longstocking: The girl with red plaits is back

Sunlit Pages: Pippi Longstocking by Astrid Lindgren

Other popular works by Astrid Lindgren

Lindgren wrote dozens of books. This is but a small sampling of the most popular that were translated into English, and which did not feature Pippi!

The Six Bullerby Children (1947)

Mio, My Son (1954)

The Children of Noisy Village (1962)

Seacrow Island (1964)

The Tomten and the Fox (1966)

The Brothers Lionheart (1973)

Ronja the Robbers Daughter (1981)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Pippi Longstocking Book Series by Astrid Lindgren appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 13, 2018

Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley (ca 1753 – December 5, 1784) was born in Senegal / Gambia, Africa. She was America’s first African-American poet and one of the first women to be published in colonial America. She was also the first slave in the U.S. to have a book of poetry published.

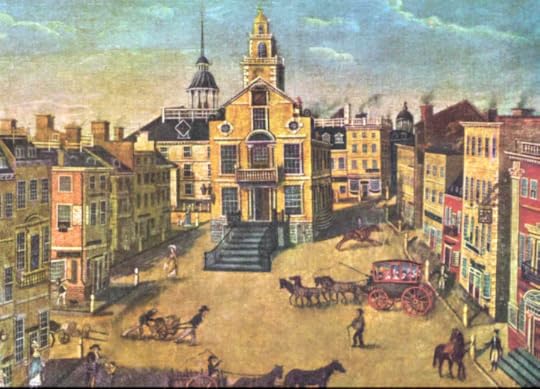

She was kidnapped as part of the slave trade as a young child and brought to North America in 1761. John Wheatley of Boston bought her from the slave market as a personal servant to his wife, Susanna. As was customary at the time, she was given the surname of the family to whom she was in bondage.

The portrait of Phillis Wheatley shown in this post is an engraving attributed to Scipio Moorhead, an enslaved African-American in Boston who was a talented artist. It’s the only existent portrait of her.

Early promise and keen intellect

It was soon apparent that Phillis had remarkable intellectual abilities, and under Susanna’s guidance, was educated along with Wheatley’s daughters. Within a year and a half, she was able to read the Bible and wrote English fluently. This was quite a rarity at a time when slaves were actively discouraged from learning to read and write. In most cases, it was forbidden altogether.

Not only was Phillis encouraged in her literary talents, she also learned Greek, Latin, ancient history and theology. She was able to translate a tale from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, inspiring a poem that would later be published.

First verses and a poetry collection

Phillis began writing verse as she mastered the English language, and when she was between 13 and 14 years old, her first poem was published in The Newport Mercury. Further publication of her poems spread the word of her talent in the colonies.

At age 19, she visited England with a son of the Wheatleys; while there, her poetry brought her a great deal of acclaim. A volume of her poems was published, titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, by Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley of Boston, in New England (London, 1773). An edition was printed in Boston not long after.

Under the influence of the Wheatley’s Puritan household, Phillis had become a devout Christian. This, along with her education in classic languages and literature, had a profound impact on the subject matter and structure of her poetry.

This portrait of Phillis Wheatley was the frontispiece of

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773)

Admired by Washington and Jefferson

In late 1775 she sent verses to General George Washington. In response, he wrote:

“I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me in the elegant lines you inclosed; and, however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyric, the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your poetical talents …”

The verses she shared with the soon-to-be first president of the U.S. were published in Pennsylvania Magazine in April 1776. Thomas Jefferson was also a reader of her poetry, writing that her verses were “beneath criticism.”

Unfortunate circumstances

When Wheatley family was broken up by death in the 1770s, Phillis was freed from slavery. Still, she was devastated by the deaths of Susanna and John. The social structure of the time made it incredibly difficult for her to fend for herself.

In 1778 she met and married John Peters, a free black man, but the union was an unhappy one, likely exacerbated by their impoverished circumstances. During the Revolution, the couple resided in Wilmington, Delaware, then returned to Boston, where they lived in abject poverty.

Phillis was unable to secure a publisher for her second volume of poetry in her short lifetime. However, there were at least four posthumous editions of her poems, and a collection of her letters were printed in 1864, many decades after her death. Phillis died on December 5, 1784, from complications due to childbirth. She was in her early thirties.

Colonial Boston, image courtesy of thehistorycat-us.com

Contemporary view of her poetry

The consensus of modern and contemporary literary critics seems to be that Phillis Wheatley an important American poet, if not a great one. It also has to be taken into account that as a slave, even one that received such an exceedingly rare education there must have been significant constraints on her freedom of expression.

Major Works and Best-Known Poems

“An Elegiac Poem on the Death of George Whitefield, Chaplain to the Countess of Huntingdon” (1770)

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, by Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley, of Boston (London, 1773; Albany, 1793; republished as The Negro Equalled by Few Europeans)

“Elegy Sacred to the Memory of Dr. Samuel Cooper” (1784)

Letters of Phillis Wheatley (Boston, 1864)

More information

Phillis Wheatley on Wikipedia

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral on Wikipedia

Phillis Wheatley on Biography.com

Read Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral on Project Gutenberg

The post Phillis Wheatley appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

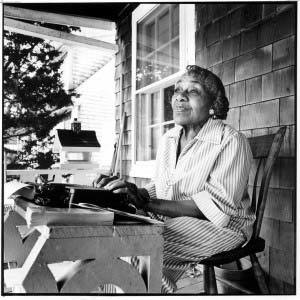

Dorothy West

Dorothy West (June 2, 1907 – August 16, 1998) was an American author and editor associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Born in Boston, she started writing as a child and began receiving accolades and awards while still in her teens. Her writing is admired for its nuanced views of middle and upper middle-class African-American communities and how it comments on gender, class, and social structure through storytelling.

In the 1920s, at age seventeen, Dorothy submitted her first short story, “The Typewriter,” to a writing contest. She traveled to New York City to accept an award for it, and shared first prize with Zora Neale Hurston, who was several years her senior. So impressed was Zora by Dorothy’s precocious talent, that she took her under her wing and introduced her to the world of the Harlem Renaissance. The two maintained a warm friendship for some years. Dorothy was known by her contemporaries as “The Kid,” an affectionate nickname given to her by poet Langston Hughes.

Early life

The daughter of a freed slave, Dorothy enjoyed a well-to-do upbringing. She studied with tutors and attended an exclusive high school. West started writing stories as a child and began to earn recognition for her work as a teenager. Her story, “Promise and Fulfillment,” won a contest and was published in a local newspaper when she was fourteen.

The Great Depression and Beyond

In 1932, Dorothy, Langston Hughes, and twenty other African-Americans went to Russia to film a story of American racism to be called Black and White. The project was dropped, but Dorothy and Langston stayed on and spent more time in Russia.

After a year in Russia, Dorothy learned of her father’s death and returned to the United States. Soon after, in 1934, she founded the literary magazine New Challeng, with her entire savings of forty dollars. The magazine was a showcase for progressive work by African-American authors, including that of Richard Wright (“Blueprint for Negro Writing”) who was her associate editor, Ralph Ellison, and Margaret Walker.

It was difficult to sustain a magazine in the depths of the Great Depression, and Dorothy was compelled to fold it. From then until the mid-forties she worked for the Works Project Administration Federal Writer’s Project and as a welfare investigator and WPA relief worker in Harlem.

She continued to write, producing stories for The New York Daily News through the 1940s, which made her the first African-American writer to be published by this newspaper.

You might also enjoy: Dorothy West Quotes on Identity and Experience

Later years

In 1947 Dorothy moved back to her family’s vacation home in Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard, where she would live for the rest of her life. Once she settled in, she started work on her first novel, The Living is Easy, which was published in 1948.

She had hoped to earn more money from the book through its planned serialization in the Ladies’ Home Journal. However, the magazine called off the project due to the negative reaction of white readers. “I was going to get what at that time was a lot of money. But weeks went by before my agent called again,” she recalled in a 1995 interview for Publishers Weekly. “The Journal had decided to drop the book because a survey indicated that they would lose many subscribers in the South.”

Financially, the cancellation was a hard blow for Dorothy. In need of a job, she found work with the local newspaper, the Martha’s Vineyard Gazette. West was hired to be a billing clerk, but with her literary talent, she would later become one of the paper’s most popular writers.

The Living is Easy & The Wedding

Her first novel, The Living is Easy, was published in 1948. The story followed the life of a young woman from the South pursuing an upper-class lifestyle. Though it was well received critically, it didn’t sell very well.

Her second novel, The Wedding, was published in 1995 to much acclaim and became a national bestseller. It tells of the wedding day of Shelby Coles, a privileged young mixed-race woman, and Meade, a white jazz musician. Complications arise as family members and lost loves arrive, building a layered portrait of five generations of an American family.

A little-known tidbit: Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the former first lady was a neighbor of Dorothy’s on Martha’s Vineyard, and a reader of her column in the local newspaper. Dorothy had started The Wedding in the 1960s, and Jackie encouraged her to finish it. She was then the associate editor at Doubleday, and ended up as the book’s editor. Jackie O died in 1994, a year before the book was published. In her inscription, Dorothy wrote:

“In memory of my editor, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Though there was never such a mismatched pair in appearance, we were perfect partners.”

Upon its publication, Dorothy was 85 years old. Shortly thereafter, in 1998, it was adapted into a television mini-series, produced by Oprah Winfrey. Dorothy died that same year.

The Wedding was produced as a 1998 mini-series

The Richer, the Poorer

Like her two novels, Dorothy’s short stories and essays, collected in The Richer, the Poorer (also published in 1995) centered around upper-middle class black American life. They’re filled with quiet wisdom and grace, as are her essays and autobiographical pieces, which touch on her experiences of growing up in a black middle-class family in Boston.

The collection also includes a piece on her 1933 trip to Moscow and musings on her life in Martha’s Vineyard, the island community off the Massachusetts coast that she loved so dearly.

Death and legacy

Dorothy later spoke of how she had been inspired by the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, which had always been dedicated to showcasing the literary talents of African-Americans. The uphill climb for writers of color in America made it daunting to sustain a literary career, especially for women, and Dorothy had felt that keenly.

Shortly before her death, she won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Lifetime Achievement. She was asked what she wanted to be her legacy. She responded: “That I hung in there. That I didn’t say I can’t.”

Dorothy West died in 1998 at the age of 91, of what were believed to be natural causes.

Dorothy West’s books on Amazon

More about Dorothy West on this site

The Wedding: A mini-series (1998)

Major Works

The Living is Easy

The Wedding

The Richer, The Poorer

The Dorothy West Martha’s Vineyard

Where The Wild Grape Grows: Selected Writings, 1930-1950

Biographies about Dorothy West

Dorothy West’s Paradise: A Biography of Class and Color

by Cherene Sherrard-Johnson

Literary Sisters: Dorothy West and her Circle, A Biography of the

Harlem Renaissance by Verner Mitchell and Cynthia Davis

More Information

Dorothy West on Wikipedia

Renaissance House Facebook

Renaissance House Residency Program

Articles, News, Etc.

Dorothy West and The Harlem Renaissance

Author Dorothy West Is Celebrated at 90

Dorothy West Digital Collection

Dorothy West, Renaissance Wom an

Television adaptation

The Wedding (mini-series), 1998

Visit and research

Dorothy West Home – Oak Bluffs, MA

Papers of Dorothy West – Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study,

Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Dorothy West appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 12, 2018

8 Facts About Daphne du Maurier and Her Literary Life

Daphne du Maurier (1907 – 1989) was a British novelist, playwright, and short story writer. She was born and raised in London, growing up in a creative family connected with the literary and theatrical worlds. Though she’s best remembered for the 1938 romantic thriller Rebecca, it’s noteworthy that she was an incredibly prolific writer of novels, short stories, and biographies.

As her fame grew, she guarded her privacy fiercely. Respecting that, let’s stick with the facts about Daphne du Maurier and her literary life, paying homage to this immensely talented author.

Her first novel was published when she was 22

The Loving Spirit was published in 1931 when Daphne was just 22 years old. The title is taken from a poem by Emily Brontë and tells the story of a family over four generations. This early success helped Daphne sell stories regularly to magazines such as The Bystander and Sunday Review.

The publication of The Loving Spirit caught the attention of Major Frederick Arthur Montague Browning, who immediately sought her out. Daphne married Frederick “Boy” Browning in 1932, and in 1946 became Lady Browning.

Rebecca has never gone out of print

Published in 1938, Rebecca sold more than 3 million copies between 1938 and 1965 and has never gone out of print. It has been adapted for film, television, and the stage. In the U.S., it won the National Book Award for the novel in 1938, as selected by members of the American Booksellers Association.

Hitchcock directed three films based on her books

Alfred Hitchcock adapted three of Daphne’s books for the big screen. Jamaica Inn (1939) was the last film Hitchcock made in his native England before moving to the U.S. Rebecca (1940), a moody thriller, captured its source material beautifully. The film version of The Birds (1963) was more frightening than it had been on the page, utilizing live birds that were specially trained for their parts!

There were even more films based on her books

Film adaptations by other directors based on her novels have included My Cousin Rachel (1952, 2017), The Scapegoat (1959), Frenchman’s Creek (1944, 1998), and Don’t Look Now (1973). This is just a partial list. Rebecca was adapted several times since the 1940 film, mainly in mini-series format for television.

She published nearly forty books

There are a half dozen or so novels and stories for which Daphne is best remembered, probably not coincidentally, those mentioned above that were adapted to film. But she was incredibly prolific — her publishing credits include numerous lesser-known novels and short story collections. She wrote nonfiction as well, including some memoirs of her own family, the talented du Mauriers.

And given her abiding interest in all things Brontë, it’s fitting that among her nonfiction titles is The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë (1960), a portrait of the troubled brother of the literary Brontë sisters that she so admired.

See also: Daphne du Maurier’s Writing Habits and Style

She was also a playwright

Though Daphne is best remembered for her novels, she also wrote three plays that were produced on the British stage. The first was an adaptation of Rebecca, which opened in 1940 at the Queen’s Theatre in London. Next was The Years Between, staged first at the Manchester Opera House in 1944, and then at Wyndham’s Theatre in 1945. Finally, September Tide opened at the Aldwych Theatre in 1938. All three plays were successful, particularly The Years Between.

She lived in the manor home that inspired Manderlay

Rebecca was set in a sprawling manor called Manabilly on the Cornwall coast of England. Daphne happened to see it when she was a girl and vowed to one day move into it. In 1943, after Rebecca had brought her fame and fortune, she had her husband leased Menabilly for 25 years.

The 70-room Menabilly manor that inspired Manderlay in Rebecca became the author’s beloved home. Here is an account from Daphne’s daughter, Flavia Leng, reminiscing on growing up in the famed home.

She was inspired by the Brontës

Set on the windswept moors, Jamaica Inn takes inspiration from Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë; it also has elements of Thornfield Hall from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). Rebecca has echoes of Jane Eyre, which you can read more about in this in-depth analysis.

Daphne was known to derive inspiration and draw connections between her beloved Cornwall (county in England) and the Yorkshire moors, where the Brontë sisters lived.

Daphne du Maurier page on Amazon

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 8 Facts About Daphne du Maurier and Her Literary Life appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 10, 2018

Madeleine L’Engle: “A Wrinkle in Time Was Almost Never Published”

I would challenge anyone to come up with a story that better illustrates the fine line between rejection and acceptance than Madeleine L’Engle’s: “A Wrinkle in Time was almost never published,” she wrote. “You can’t name a major publisher who didn’t reject it. When we’d run through forty-odd publishers, my agent sent it back. We gave up.” Most editors thought it too dark and complex for children.

After some time, L’Engle made contact with John Farrar of Farrar Straus Giroux through a friend of her mother’s, and the rest is publishing history. Published in 1962, A Wrinkle in Time is still in print, with millions of copies sold worldwide. It has the distinction of having won some of the most prestigious publishing awards, as well as being one of the most frequently banned books of all time.

Translating A Wrinkle in Time to film

The first attempt to translate Wrinkle into film was in 2003, when a Canadian film company produced what was intended to be a TV mini-series. Instead, the episodes were combined into a three-hour block and aired on ABC-TV. Though previously it had won Best Feature Film in the Toronto Film Festival, the televised version wasn’t well received by critics — or the author. L’Engle said in an interview: “I have glimpsed it … I expected it to be bad, and it is.”

The big-budget, star-studded 2018 film version of A Wrinkle in Time has also received its share of mixed reviews. CNET wrote that for all the visual spectacle, it lacks “the sense of wonder and discovery that should accompany such a film. The movie is supposed to be an epic adventure, but instead it feels like a taxi ride to somewhere with beautiful scenery in between.” It’s interesting to ponder what the author would have thought of the Hollywood Blockbuster treatment of her quirky, groundbreaking sci-fi/fantasy novel for kids.

Scene from A Wrinkle in Time, 2018

No matter what the budget is or how nobel the intentions, it’s so rare that a film really captures the spirit of a classic novel that the author intended. It does happen, but those instances are few and far between. Still, it’s very cool that a novel that was nearly relegated to oblivion still continues to resonate. The moral of this story, though is … read the book. Or at least, read it before you see the film, so that you can hold the source material as the author intended, close to your heart.

Here are some passages from her memoir, A Circle of Quiet (1972), in which she recalls the bitter years when A Wrinkle in Timeas well as her other books were met with nothing but rejection:

Madeleine L’Engle on Keeping the Faith

“When my book was rejected by publisher after publisher, I cried out in my journal. I wrote, after an early rejection, ‘X turned down Wrinkle, turned it down with one hand while saying that he loved it, but didn’t quite dare do it, as it isn’t really classifiable, and am wondering if I’ll have to go through the usual hell with this that I seem to go through with everything that I write. But this book I’m sure of…'”

“… I was, perhaps, out of joint with time. Two of my books for children were rejected for reasons which would be considered absurd today. Publisher after publisher turned down Meet the Austins because it begins with a death. Publisher after publisher turned down A Wrinkle in Time because it deals overtly with the problem of evil, and it was too difficult for children, and was it a children’s or adult’ book, anyhow?

My adult novels were rejected, too. A Winter’s Love was too moral: the married protagonist refuses an affair because of the strength of her responsibility towards marriage. Then, shortly before my fortieth birthday, both Meet the Austins and an adult novel, The Lost Innocent, had been in publishing houses long enough to get my hopes up …

On my birthday, I was, as usual, out in the Tower working on a book. The children were in school. My husband was at work and would be getting the mail. He called, saying, ‘I’m sorry to have to tell you this on your birthday, but you’d never trust me again if I kept it from you. [Such-and such editor] has rejected The Lost Innocent.‘

This seemed like an obvious sign from heaven. I should stop trying to write. All during the decade of my thirties (the 1950s) I went through spasms of guilt because I spent so much time writing, because I wasn’t like a good New England housewife and mother … So the rejection on the fortieth birthday seemed an unmistakable command: Stop this foolishness and learn to make cherry pie.”

More about A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle

Paving the way for more complex children’s literature

Fortunately, L’Engle didn’t “stop the foolishness;” she kept writing, of course, and with her persistence and belief in her power to tell stories, finally found that one editor who was willing to take the chance on her quirky, profound novel

Might L’Engle’s books have paved the way for the acceptance of children’s literature that’s more complex, even dark? Have these kinds of books become more palatable to publishers? That seems to be the case. Evidently, children have long proven themselves ready for these themes, borne out most abundantly by the unparalleled success of the Harry Potter series.

Much has been made of the initial rejections of the first installment of J.K. Rowling’s blockbuster series, but hers were the more usual numbers of rejections before an agent, then a publisher recognized the talent and passion of this then-unknown writer. Her path wasn’t smooth, to be sure, but it may have been much rougher had it not been for authors like Madeleine L’Engle who came before her.

After A Wrinkle in Time came out and was an immediate smash success, the editors who has turned it down were filled with regrets: “After the unexpected success of Wrinkle,” L’Engle recalled, “I was invited to quite a lot of literary bashes and was frequently approached by publishers who had rejected it. ‘I wish you had sent the book to us.’ I could usually respond, ‘But I did.'”

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle on Amazon

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Madeleine L’Engle: “A Wrinkle in Time Was Almost Never Published” appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.