Nava Atlas's Blog, page 87

April 9, 2018

Onions in the Stew by Betty MacDonald

Onions in the Stew by Betty MacDonald (1954) is a humorous memoir about the author’s life in Washington State with her family. Taking place in the mid-twentieth century, the events described take place from 1942 to 1954.

Betty, a divorced working mother, lives with her two preteen daughters in her mother’s home. After she meets and marries Donald MacDonald, they find it difficult to find one in Seattle or its suburbs, and finally settle on a property on nearby Vashon Island.

The tale follows the familiar trope of city folks finding themselves in way over their heads when moving to the country, and all the little disasters that follow when buying a house that turns out to be a money pit. In the hands of Betty MacDonald, who made her name with the first of her series of memoirs, The Egg and I (1945), it all becomes wryly good-natured fun. The title comes from a poem by Charles Divine:

“Some said it was Bohemia, this little haunt we knew

When hearts were high and fortunes low, and onions in the stew.”

Here’s a description of the book by John P. Marquand for Book of the Month Club News, provided when the book was released in 1955:

Red-ink budgets, balky plumbing, and noodles

Anyone who can write with genuine joy, gusto, and enthusiasm regarding the vicissitudes of home, husband, dogs, and children commands an enormous audience. This of course has been the deserved good fortune of Betty MacDonald ever since The Egg and I appeared in 1945. She is a girl who seems to enjoy every moment of living, not matter how or where.

She has coped with red-ink budgets, balky plumbing, and nothing in the kitchen but noodles. She has lived through dog fights, measles, and all the usual and unusual cataclysms of nature. But even when domestic morale has sunk to the bottom of the barrel, she and everyone around her have had a wonderful time.

Because of her ability to tell a good story, this joie de vivre is communicated to all who read her pages. Her latest book, in my opinion, her best to date. Onions in the Stew is a homely title, but then it is a homely book, brimming over with incidents of everyday life — some of which we have experienced ourselves, others which Betty MacDonald enables us to live vicariously and with unalloyed delight.

You might also like: The Egg and I by Betty MacDonald

City folks on the frontier

Onions in the Stew is a saga of domestic life on Vashon Island, which lies in Puget Sound within commuting distance of the city of Seattle, Washington. If one thinks that Vashon Island — complete with Betty MacDonald, her husband Don, her daughters Anne and Josh, and the family dog Tudor — resembles anything in New York Harbor, they are in error.

The American Northwest is still a land of rugged plenty that has not lost all its frontier quality. Its Douglas fir trees are not lumbered out yet; its shores are washed by the marrow-chilling North Pacific; its forests and farm lands are watered by almost constant winter rainfall. Mount Rainier, when you can see it through the rainclouds, broods over a world of plenty; and a perpetual conflict between nature and human encroachment lends life there a comedy value which only Betty MacDonald so far has been able to interpret.

She knows that you can never tell exactly what nature may do in the vicinity of Seattle. Plant a sapling on your front lawn and almost overnight it becomes a giant.

If you are not careful with vines and shrubbery, they smother your house while your back is turned. Small fruits, particularly berries, grow in such lavish profusion that they threaten with nervous breakdown. Deer and raccoon wander vaguely over lawns and gardens, and on the beaches are peculiar shellfish, including a clam-like creature known as a geoduck that can move through sand with the speed of an express train.

Onions in the Stew by Betty MacDonald on Amazon

Ludicrous details of keeping a home

Vashon Island is inhabited by many friendly and interesting neighbors; the MacDonald House can only be reached by beach or by trail; and the whole area seems to abound in dogs, all of who appear to have incurred the intense dislike of Tudor.

Seeing these phenomena through the eyes of Mrs. MacDonald causes one to grow wiser in the ways of the Northwest — but never sadder. No one can tell a better story than she when it involves the ludicrous details that go into keeping a home together.

It is impossible to forget the MacDonald’s pursuit of the washing machine which they thought was resting safely in a rowboat near their sea wall, or Tudor’s classic fight with one of his bitterest enemies, or the family’s capture of a geoduck. The variety of the MacDonald life is as abundant as Betty MacDonald’s good nature.

Aside from being consistently entertained, readers of Onions in the Stew will also gain a strong sense of inner satisfaction … it teaches us that happiness can flourish in very unexpected quarters as long as it is nourished by comradeship and love and humor, and that for some of us, at any rate, a lot is still right in the world.

— review by John P. Marquand for Book of the Month Club News

How Onions in the Stew by Betty MacDonald Begins …

Chapter 1: No money and no furniture

For twelve years we MacDonalds have been living on an island in Puget Sound. There is no getting away from it, life on an island is different from life in the St. Francis Hotel but you can get used to it, can even grow to like it. “C’est la guerre,” we used to say looking wistfully toward the lights of the big comfortable warm city just across the way. Now, as November (or July) settles around the house like a wet sponge, we say placidly to each other, “I love it here. I wouldn’t live anywhere else.”

I cannot say that everyone should live as we do, but you might be happy on an island if you can face up to the following:

1. Dinner guests are often still with you seven days, weeks, months later and slipping in the lawn swing is fun (I keep telling Don) if you take two sleeping pills and remember that the raccoons are just trying to be friends.

2. Any definite appointment, such as childbirth or jury duty, acts as an automatic signal for the ferryboats to stop running.

3. Finding island property is easy, especially up here in the Northwest where most of the time even the people are completely surrounded by water. Financing is something else again. Bankers are urban and everything not visible from a bank is “too far out.”

4. A telephone call from a relative beginning “Hello dear, we’ve been thinking of you …” means you are going to get somebody’s children.

5. Any dinner can be stretched by the addition of noodles to something.

6. If you miss the last ferry — the 1:05 A.M. — you have to sit on the dock all night, but the time will come when you will be grateful for that large body of water between you and those thirteen parking tickets.

7. Anyone contemplating island dwelling must be physically strong and it is an added advantage if you aren’t too bright.

Learn more about Betty MacDonald

More about Onions in the Stew by Betty MacDonald

Reader discussion on Goodreads

The post Onions in the Stew by Betty MacDonald appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 5, 2018

Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti

Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti (1830 – 1894) is the best known poem by this Victorian-era British poet. It was published in her first volume of poetry, Goblin Market and Other Poems, in 1863. This very long narrative poem is set in an imaginary world, describing the strange adventures of sisters Laura and Lizzie and their encounters with evil goblin merchants.

One of the main themes of this poem is temptation, illustrated by Laura’s tasting of enchanted forbidden fruit. It also explores sacrifice, sexuality, and salvation. According to Discovering Literature: Romantics and Victorians:

“When Laura exchanges a lock of her golden hair for the chance to taste the goblins’ enchanted ‘fruit forbidden,’ she deteriorates until she is ‘knocking at Death’s door.’ Her sister Lizzie offers to pay the goblins ‘a silver penny’ for more of their wares, which she hopes will act as an antidote to Laura’s malady. The goblins violently attack Lizzie, smearing their fruits ‘against her mouth’ in a vain attempt ‘to make her eat.’ After the goblins are ‘worn out by her resistance,’ Lizzie returns home, and Laura kisses the juices from her sister’s face and is restored.”

The fruit in the poem has been interpreted in a number of ways. It has often been seen, in its most obvious sense, as symbolic of sexual temptation. Interesting Literature describes Laura:

“as the fallen woman who succumbs to masculine wiles and is ruined as a result (though she is, of course, happily married at the end of the poem). But this ‘temptation’ invites further analysis and interpretation. Some critics have drawn parallels between Laura’s addiction to the exotic fruit in the poem and the experience of drug addiction. In Victorian Britain, opium-addiction was a real social problem, opium being, like the fruits of ‘Goblin Market’, both sweet and bitter …”

For a detailed, nearly line-by-line analysis, see Goblin Market on Poem Analysis. Or, if you’d like to simply enjoy the poem and interpret it in your own way, read on …

Christina’s brother, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, illustrated the original edition

Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti

Morning and evening

Maids heard the goblins cry:

‘Come buy our orchard fruits,

Come buy, come buy:

Apples and quinces,

Lemons and oranges,

Plump unpecked cherries,

Melons and raspberries,

Bloom-down-cheeked peaches,

Swart-headed mulberries

Wild free-born cranberries,

Crab-apples, dewberries,

Pine-apples, blackberries,

Apricots, strawberries;—

All ripe together

In summer weather,—

Morns that pass by,

Fair eves that fly;

Come buy, come buy:

Our grapes fresh from the vine

Pomegranates full and fine,

Dates and sharp bullaces,

Rare pears and greengages,

Damsons and bilberries,

Taste them and try:

Currants and gooseberries,

Bright-fire-like barberries,

Figs to fill your mouth,

Citrons from the South,

Sweet to tongue and sound to eye;

Come buy, come buy.’

Evening by evening

Among the brookside rushes,

Laura bowed her head to hear,

Lizzie veiled her blushes:

Crouching close together

In the cooling weather,

With clasping arms and cautioning lips,

With tingling cheeks and finger tips.

‘Lie close,’ Laura said,

Pricking up her golden head:

‘We must not look at goblin men,

We must not buy their fruits:

Who knows upon what soil they fed

Their hungry thirsty roots?’

‘Come buy,’ call the goblins

Hobbling down the glen.

‘Oh,’ cried Lizzie, ‘Laura, Laura,

You should not peep at goblin men.’

Lizzie covered up her eyes,

Covered close lest they should look;

Laura reared her glossy head,

And whispered like the restless brook:

‘Look, Lizzie, look, Lizzie,

Down the glen tramp little men.

One hauls a basket,

One bears a plate,

One lugs a golden dish

Of many pounds weight.

How fair the vine must grow

Whose grapes are so luscious;

How warm the wind must blow

Through those fruit bushes.’

‘No,’ said Lizzie, ‘No, no, no;

Their offers should not charm us,

Their evil gifts would harm us.’

She thrust a dimpled finger

In each ear, shut eyes and ran:

Curious Laura chose to linger

Wondering at each merchant man.

One had a cat’s face,

One whisked a tail,

One tramped at a rat’s pace,

One crawled like a snail,

One like a wombat prowled obtuse and furry,

One like a ratel tumbled hurry skurry.

She heard a voice like voice of doves

Cooing all together:

They sounded kind and full of loves

In the pleasant weather.

Laura stretched her gleaming neck

Like a rush-imbedded swan,

Like a lily from the beck,

Like a moonlit poplar branch,

Like a vessel at the launch

When its last restraint is gone.

Backwards up the mossy glen

Turned and trooped the goblin men,

With their shrill repeated cry,

‘Come buy, come buy.’

When they reached where Laura was

They stood stock still upon the moss,

Leering at each other,

Brother with queer brother;

Signalling each other,

Brother with sly brother.

One set his basket down,

One reared his plate;

One began to weave a crown

Of tendrils, leaves, and rough nuts brown

(Men sell not such in any town);

One heaved the golden weight

Of dish and fruit to offer her:

‘Come buy, come buy,’ was still their cry.

Laura stared but did not stir,

Longed but had no money:

The whisk-tailed merchant bade her taste

In tones as smooth as honey,

The cat-faced purr’d,

The rat-faced spoke a word

Of welcome, and the snail-paced even was heard;

One parrot-voiced and jolly

Cried ‘Pretty Goblin’ still for ‘Pretty Polly;’—

One whistled like a bird.

But sweet-tooth Laura spoke in haste:

‘Good folk, I have no coin;

To take were to purloin:

I have no copper in my purse,

I have no silver either,

And all my gold is on the furze

That shakes in windy weather

Above the rusty heather.’

‘You have much gold upon your head,’

They answered all together:

‘Buy from us with a golden curl.’

She clipped a precious golden lock,

She dropped a tear more rare than pearl,

Then sucked their fruit globes fair or red:

Sweeter than honey from the rock,

Stronger than man-rejoicing wine,

Clearer than water flowed that juice;

She never tasted such before,

How should it cloy with length of use?

She sucked and sucked and sucked the more

Fruits which that unknown orchard bore;

She sucked until her lips were sore;

Then flung the emptied rinds away

But gathered up one kernel stone,

And knew not was it night or day

As she turned home alone.

Lizzie met her at the gate

Full of wise upbraidings:

‘Dear, you should not stay so late,

Twilight is not good for maidens;

Should not loiter in the glen

In the haunts of goblin men.

Do you not remember Jeanie,

How she met them in the moonlight,

Took their gifts both choice and many,

Ate their fruits and wore their flowers

Plucked from bowers

Where summer ripens at all hours?

But ever in the noonlight

She pined and pined away;

Sought them by night and day,

Found them no more, but dwindled and grew grey;

Then fell with the first snow,

While to this day no grass will grow

Where she lies low:

I planted daisies there a year ago

That never blow.

You should not loiter so.’

‘Nay, hush,’ said Laura:

‘Nay, hush, my sister:

I ate and ate my fill,

Yet my mouth waters still;

To-morrow night I will

Buy more:’ and kissed her:

‘Have done with sorrow;

I’ll bring you plums to-morrow

Fresh on their mother twigs,

Cherries worth getting;

You cannot think what figs

My teeth have met in,

What melons icy-cold

Piled on a dish of gold

Too huge for me to hold,

What peaches with a velvet nap,

Pellucid grapes without one seed:

Odorous indeed must be the mead

Whereon they grow, and pure the wave they drink

With lilies at the brink,

And sugar-sweet their sap.’

Golden head by golden head,

Like two pigeons in one nest

Folded in each other’s wings,

They lay down in their curtained bed:

Like two blossoms on one stem,

Like two flakes of new-fall’n snow,

Like two wands of ivory 190

Tipped with gold for awful kings.

Moon and stars gazed in at them,

Wind sang to them lullaby,

Lumbering owls forbore to fly,

Not a bat flapped to and fro

Round their rest:

Cheek to cheek and breast to breast

Locked together in one nest.

Early in the morning

When the first cock crowed his warning,

Neat like bees, as sweet and busy,

Laura rose with Lizzie:

Fetched in honey, milked the cows,

Aired and set to rights the house,

Kneaded cakes of whitest wheat,

Cakes for dainty mouths to eat,

Next churned butter, whipped up cream,

Fed their poultry, sat and sewed;

Talked as modest maidens should:

Lizzie with an open heart,

Laura in an absent dream,

One content, one sick in part;

One warbling for the mere bright day’s delight,

One longing for the night.

At length slow evening came:

They went with pitchers to the reedy brook;

Lizzie most placid in her look,

Laura most like a leaping flame.

They drew the gurgling water from its deep;

Lizzie plucked purple and rich golden flags,

Then turning homeward said: ‘The sunset flushes

Those furthest loftiest crags;

Come, Laura, not another maiden lags,

No wilful squirrel wags,

The beasts and birds are fast asleep.’

But Laura loitered still among the rushes

And said the bank was steep.

And said the hour was early still

The dew not fall’n, the wind not chill:

Listening ever, but not catching

The customary cry,

‘Come buy, come buy,’

With its iterated jingle

Of sugar-baited words:

Not for all her watching

Once discerning even one goblin

Racing, whisking, tumbling, hobbling;

Let alone the herds

That used to tramp along the glen,

In groups or single,

Of brisk fruit-merchant men.

Till Lizzie urged, ‘O Laura, come;

I hear the fruit-call but I dare not look:

You should not loiter longer at this brook:

Come with me home.

The stars rise, the moon bends her arc,

Each glowworm winks her spark,

Let us get home before the night grows dark:

For clouds may gather

Though this is summer weather,

Put out the lights and drench us through;

Then if we lost our way what should we do?’

Laura turned cold as stone

To find her sister heard that cry alone,

That goblin cry,

‘Come buy our fruits, come buy.’

Must she then buy no more such dainty fruit?

Must she no more such succous pasture find,

Gone deaf and blind?

Her tree of life drooped from the root:

She said not one word in her heart’s sore ache;

But peering thro’ the dimness, nought discerning,

Trudged home, her pitcher dripping all the way;

So crept to bed, and lay

Silent till Lizzie slept;

Then sat up in a passionate yearning,

And gnashed her teeth for baulked desire, and wept

As if her heart would break.

Day after day, night after night,

Laura kept watch in vain

In sullen silence of exceeding pain.

She never caught again the goblin cry:

‘Come buy, come buy;’—

She never spied the goblin men

Hawking their fruits along the glen:

But when the noon waxed bright

Her hair grew thin and grey;

She dwindled, as the fair full moon doth turn

To swift decay and burn

Her fire away.

One day remembering her kernel-stone

She set it by a wall that faced the south;

Dewed it with tears, hoped for a root,

Watched for a waxing shoot,

But there came none;

It never saw the sun,

It never felt the trickling moisture run:

While with sunk eyes and faded mouth

She dreamed of melons, as a traveller sees

False waves in desert drouth

With shade of leaf-crowned trees,

And burns the thirstier in the sandful breeze.

She no more swept the house,

Tended the fowls or cows,

Fetched honey, kneaded cakes of wheat,

Brought water from the brook:

But sat down listless in the chimney-nook

And would not eat.

Tender Lizzie could not bear

To watch her sister’s cankerous care

Yet not to share.

She night and morning

Caught the goblins’ cry:

‘Come buy our orchard fruits,

Come buy, come buy:’—

Beside the brook, along the glen,

She heard the tramp of goblin men,

The voice and stir

Poor Laura could not hear;

Longed to buy fruit to comfort her,

But feared to pay too dear.

She thought of Jeanie in her grave,

Who should have been a bride;

But who for joys brides hope to have

Fell sick and died

In her gay prime,

In earliest Winter time

With the first glazing rime,

With the first snow-fall of crisp Winter time.

Till Laura dwindling

Seemed knocking at Death’s door:

Then Lizzie weighed no more

Better and worse;

But put a silver penny in her purse,

Kissed Laura, crossed the heath with clumps of furze

At twilight, halted by the brook:

And for the first time in her life

Began to listen and look.

Laughed every goblin

When they spied her peeping:

Came towards her hobbling,

Flying, running, leaping,

Puffing and blowing,

Chuckling, clapping, crowing,

Clucking and gobbling,

Mopping and mowing,

Full of airs and graces,

Pulling wry faces,

Demure grimaces,

Cat-like and rat-like,

Ratel- and wombat-like,

Snail-paced in a hurry,

Parrot-voiced and whistler,

Helter skelter, hurry skurry,

Chattering like magpies,

Fluttering like pigeons,

Gliding like fishes,—

Hugged her and kissed her:

Squeezed and caressed her:

Stretched up their dishes,

Panniers, and plates:

‘Look at our apples

Russet and dun,

Bob at our cherries,

Bite at our peaches,

Citrons and dates,

Grapes for the asking,

Pears red with basking

Out in the sun,

Plums on their twigs;

Pluck them and suck them,

Pomegranates, figs.’—

‘Good folk,’ said Lizzie,

Mindful of Jeanie:

‘Give me much and many:’—

Held out her apron,

Tossed them her penny.

‘Nay, take a seat with us,

Honour and eat with us,’

They answered grinning:

‘Our feast is but beginning.

Night yet is early,

Warm and dew-pearly,

Wakeful and starry:

Such fruits as these

No man can carry;

Half their bloom would fly,

Half their dew would dry,

Half their flavour would pass by.

Sit down and feast with us,

Be welcome guest with us,

Cheer you and rest with us.’—

‘Thank you,’ said Lizzie: ‘But one waits

At home alone for me:

So without further parleying,

If you will not sell me any

Of your fruits though much and many,

Give me back my silver penny

I tossed you for a fee.’—

They began to scratch their pates,;

No longer wagging, purring,

But visibly demurring,

Grunting and snarling.

One called her proud,

Cross-grained, uncivil;

Their tones waxed loud,

Their looks were evil.

Lashing their tails

They trod and hustled her,

Elbowed and jostled her,

Clawed with their nails,

Barking, mewing, hissing, mocking,

Tore her gown and soiled her stocking,

Twitched her hair out by the roots,

Stamped upon her tender feet,

Held her hands and squeezed their fruits

Against her mouth to make her eat.

White and golden Lizzie stood,

Like a lily in a flood,—

Like a rock of blue-veined stone

Lashed by tides obstreperously,—

Like a beacon left alone

In a hoary roaring sea,

Sending up a golden fire,—

Like a fruit-crowned orange-tree

White with blossoms honey-sweet

Sore beset by wasp and bee,—

Like a royal virgin town

Topped with gilded dome and spire

Close beleaguered by a fleet 420

Mad to tug her standard down.

One may lead a horse to water,

Twenty cannot make him drink.

Though the goblins cuffed and caught her,

Coaxed and fought her,

Bullied and besought her,

Scratched her, pinched her black as ink,

Kicked and knocked her,

Mauled and mocked her,

Lizzie uttered not a word;

Would not open lip from lip

Lest they should cram a mouthful in:

But laughed in heart to feel the drip

Of juice that syrupped all her face,

And lodged in dimples of her chin,

And streaked her neck which quaked like curd.

At last the evil people,

Worn out by her resistance,

Flung back her penny, kicked their fruit

Along whichever road they took,

Not leaving root or stone or shoot;

Some writhed into the ground,

Some dived into the brook

With ring and ripple,

Some scudded on the gale without a sound,

Some vanished in the distance.

In a smart, ache, tingle,

Lizzie went her way;

Knew not was it night or day;

Sprang up the bank, tore thro’ the furze,

Threaded copse and dingle,

And heard her penny jingle

Bouncing in her purse,—

Its bounce was music to her ear.

She ran and ran

As if she feared some goblin man

Dogged her with gibe or curse

Or something worse:

But not one goblin skurried after,

Nor was she pricked by fear;

The kind heart made her windy-paced

That urged her home quite out of breath with haste

And inward laughter.

She cried ‘Laura,’ up the garden,

‘Did you miss me?

Come and kiss me.

Never mind my bruises,

Hug me, kiss me, suck my juices

Squeezed from goblin fruits for you,

Goblin pulp and goblin dew.

Eat me, drink me, love me;

Laura, make much of me:

For your sake I have braved the glen

And had to do with goblin merchant men.’

Laura started from her chair,

Flung her arms up in the air,

Clutched her hair:

‘Lizzie, Lizzie, have you tasted

For my sake the fruit forbidden?

Must your light like mine be hidden,

Your young life like mine be wasted,

Undone in mine undoing,

And ruined in my ruin,

Thirsty, cankered, goblin-ridden?’—

She clung about her sister,

Kissed and kissed and kissed her:

Tears once again

Refreshed her shrunken eyes,

Dropping like rain

After long sultry drouth;

Shaking with aguish fear, and pain,

She kissed and kissed her with a hungry mouth.

Her lips began to scorch,

That juice was wormwood to her tongue,

She loathed the feast:

Writhing as one possessed she leaped and sung,

Rent all her robe, and wrung

Her hands in lamentable haste,

And beat her breast.

Her locks streamed like the torch

Borne by a racer at full speed,

Or like the mane of horses in their flight,

Or like an eagle when she stems the light

Straight toward the sun,

Or like a caged thing freed,

Or like a flying flag when armies run.

Swift fire spread through her veins, knocked at her heart,

Met the fire smouldering there

And overbore its lesser flame;

She gorged on bitterness without a name:

Ah! fool, to choose such part

Of soul-consuming care!

Sense failed in the mortal strife:

Like the watch-tower of a town

Which an earthquake shatters down,

Like a lightning-stricken mast,

Like a wind-uprooted tree

Spun about,

Like a foam-topped waterspout

Cast down headlong in the sea,

She fell at last;

Pleasure past and anguish past,

Is it death or is it life?

Life out of death.

That night long Lizzie watched by her,

Counted her pulse’s flagging stir,

Felt for her breath,

Held water to her lips, and cooled her face

With tears and fanning leaves:

But when the first birds chirped about their eaves,

And early reapers plodded to the place

Of golden sheaves,

And dew-wet grass

Bowed in the morning winds so brisk to pass,

And new buds with new day

Opened of cup-like lilies on the stream,

Laura awoke as from a dream,

Laughed in the innocent old way,

Hugged Lizzie but not twice or thrice;

Her gleaming locks showed not one thread of grey,

Her breath was sweet as May

And light danced in her eyes.

Days, weeks, months, years

Afterwards, when both were wives

With children of their own;

Their mother-hearts beset with fears,

Their lives bound up in tender lives;

Laura would call the little ones

And tell them of her early prime,

Those pleasant days long gone

Of not-returning time:

Would talk about the haunted glen,

The wicked, quaint fruit-merchant men,

Their fruits like honey to the throat

But poison in the blood;

(Men sell not such in any town:)

Would tell them how her sister stood

In deadly peril to do her good,

And win the fiery antidote:

Then joining hands to little hands

Would bid them cling together,

‘For there is no friend like a sister

In calm or stormy weather;

To cheer one on the tedious way,

To fetch one if one goes astray,

To lift one if one totters down,

To strengthen whilst one stands.’

The post Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 4, 2018

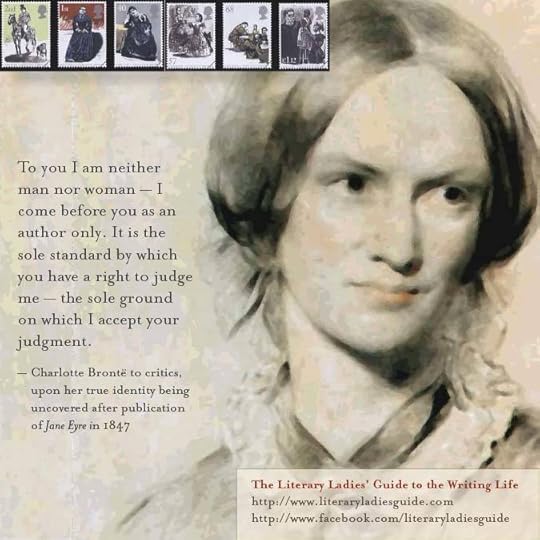

Villette by Charlotte Brontë (1853)

My first impression of Villette by Charlotte Brontë (1853) was the familiarity of the writing — if I had no inclination of the author or book title, but merely “read it blind,” I think I would still know it was Charlotte Brontë. Even though I had never read it before, the style was so familiar because it was so apparently Charlotte.

Because I had read Lyndall Gordon’s amazing biography on Charlotte beforehand, I felt prepared for Villette. I read it with an eye for what it said about Charlotte — her life, her experiences, her opinions — and I think this colored my experience of it. Ultimately, it is a book in which the plot is only secondary.

Lucy Snowe: A woman of storm and shadow

Character reigns supreme over the novel — that of the narrator, Lucy Snowe, as well as those around her. The focus of the book lies primarily with the development of Lucy’s character. Lucy Snowe is a woman of storm and shadow — the first she denies and stifles within herself, the other she uses to hide and protect herself from what she does not want to face.

The metaphors of storms and shadows occur over and over throughout the narrative, reflecting Lucy’s inner world as it describes the outer setting. The stormy nights are the ones in which new discoveries are made, new secrets come to light, and when she must internally struggle with herself and her life’s path.

And the shadows? When I think of what exactly a shadow is, I see how well it fits with Lucy. A shadow is not distinct or clear, it can be altered, it is not a true representation of the real object, and (perhaps most importantly here), it can be interpreted in a myriad of ways.

Figuratively, Lucy hides herself in the shadows, content to stay hidden and keep her true, inner self from others and even partly from herself. She does not even truly open herself to us, her readers. Unlike Jane Eyre, she is more cautious and reserved, less open about details. She does not reveal everything to us, leaving parts of the story unexplained and hidden from view.

You might also like:

Jane Eyre: A Late 19th-Century Analysis

In the story itself Lucy is often invisible, her friends and acquaintances taking center stage while she quietly observes and narrates from the sidelines. She tends to disappear beneath the lives of those around her, unobserved and content to be so. In fact, whole chapters often go by where she hardly makes an entrance.

She also hides in plain sight from each of her friends and acquaintances. Each one sees her differently, interpreting her by a different light, for they see her as she wishes to be seen by them. Therefore, she is never truly seen because she is not seen as she is. She becomes insubstantial, a mere image of herself, as a shadow is only a representation of reality.

I did wonder, how much of this is true of us? Don’t we change our demeanor and personalities based on those we are interacting with; aren’t we different around different people? If that is the case, then when are we truly ourselves? Is it with those we are only the closest to or are our true selves an amalgamation of the various parts we present to others?

A struggle to balance reason and passion

Lyndall Gordon stated that Charlotte’s novels all represent Charlotte’s struggle to balance Reason and Passion, while not becoming overcome by either. After reading that, I saw how true it was in Jane Eyre and I watched for it in Villette. Sure enough, it was there.

Lucy Snowe’s story is affected and altered by the fact that she fights against her nature and her passionate inclinations. This too ties into her desire to stay hidden in shadow. Desperately she tries to stifle the part of herself that yearns for more, focusing on the necessity of “knocking on the head” her longings and desires.

When she starts to feel a passion for Dr. John, she figuratively buries those feelings and their potential by literally burying his letters beneath the earth. Lucy is content to stay in the shadows because she feels safer there- not safe from the threat of others, but safe from herself. She fears the deeper parts within herself, which I think is one of the most tragic aspects of the book, for it alters her life and the person she becomes.

Villette by Charlotte Brontë on Amazon

In Lucy, I think Charlotte is trying to demonstrate to herself, as well as to her readers, the danger of letting logic and reason possess you fully; perhaps this was also Charlotte’s way of reminding herself that it is necessary to let passion and desire in, despite the fears.

I think readers today can still identify with this struggle — of trying to understand ourselves, of wrestling with our natures, of trying to be something we are not. I know that I often fight against who I am, both the negative and the positive, and struggle with the desire to be someone else, that elusive “other” I think I should be.

Both Villette and Jane Eyre resonate with me because I am still defining myself and finding my place in the world, just as Charlotte was and just as her heroines strive to do. As Villette (and Jane Eyre) demonstrates, the process does not require one to have all of the answers or the perfect life plan. Instead, it involves using each experience — with all of its uncertainty and risk- to discover and lay bare what is hidden within me.

Timeless works by Charlotte Brontë

To not hide from who I am, but to allow it into the light. To be open to the potential of new discoveries, and embracing — not hiding from — the fear and trepidation that accompanies each revelation. To be strong enough to recognize and embrace who I am, without denying what I am and what I feel. Jane Eyre demonstrates this by doing it, by being true to herself, by following her inclinations and listening to her inner self. Lucy Snowe demonstrates this by not doing so, by hiding from any expression of her inner self, by denying her passions and desires, by choosing a safe but unfulfilling life over the promise of something more.

With Villette, Charlotte’s works continue to exert a powerful force of brilliant insight, demonstrating just how timeless her works really are. Jane Eyre will always remain my favorite, but I am more pleased than I expected with the experience I had in Villette, and am more of a Brontë fan than ever before.

— Contributed by Jillian Fuller. This post originally ran on Musings of a Bookworm; reprinted by permission.

More about Villette by Charlotte Brontë

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Why Villette is Better than Jane Eyre

Villette on Project Gutenberg

Listen to Villette on Librivox

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Villette by Charlotte Brontë (1853) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 3, 2018

Quotes from The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck

Pearl S. Buck (1892 – 1973) was an American author of fiction and nonfiction, humanitarian, and human rights advocate. She was also the first American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. She had a prolific career, authoring some seventy books. and was also a dedicated activist in human rights, founding the East and West Association in 1941.

Pearl Buck’s second novel, The Good Earth, is her best-known work and remains the one that defined her success as an author. It received both the Pulitzer Prize and the Howells Medal in 1932. Following are quotes from The Good Earth, the classic novel that’s still widely read and studied:

“And roots, if they are to bear fruits, must be kept well in the soil of the land.”

“It is the end of a family — when they begin to sell their land. Out of the land we came and into we must go — and if you will hold your land you can live — no one can rob you of land.”

“Hunger makes thief of any man.”

“And out of his heaviness there stood out strangely but one clear thought and it was a pain to him, and it was this, that he wished he had not taken the two pearls from O-lan that day when she was washing his clothes at the pool, and he would never bear to see Lotus put them in her ears again.”

“But hers was a strange heart, sad in its very nature, and she could never weep and ease it as other women do, for her tears never brought her comfort.”

“When I return to that house it will be with my son in my arms. I shall have a red coat on him and red-flowered trousers and on his head a hat with a small gilded Buddha sewn on the front and on his feet tiger-faced shoes. And I will wear new shoes and a new coat of black sateen and I will go into the kitchen where I spent my days and I will go into the great hall where the Old One sits with her opium, and I will show myself and my son to all of them.”

“The first peaches of spring — the first peaches! Buy, eat, purge your bowels of the poisons of winter!”

“And to him war was a thing like earth and sky and water and why it was no one knew but only that it was.”

You might also enjoy:

1938 Nobel Award for Literature to Pearl Buck

“So Wang Lung sat, and so his age came on him day by day and year by year, and he slept fitfully in the sun as his father had done, and he said to himself that his life was done and he was satisfied with it.”

“It is but another war somewhere. Who knows what all this fighting to and fro is about? But so it has been since I was a lad and so will it be after I am dead and well I know it.”

The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck on Amazon

“Yes, but there was the land. Money and food are eaten and gone, and if there is not sun and rain in proportion, there is again hunger.”

“Then the good land did again its healing work and the sun shone on him and healed him and the warm winds of summer wrapped him about with peace.”

“Wang Lung sat smoking, thinking of the silver as it had lain upon the table. It had come out of the earth, this silver, out of his earth that he ploughed and turned and spent himself upon. He took his life from this earth; drop by drop by his sweat he wrung food from it and from the food, silver. Each time before this that he had taken the silver out to give to anyone, it had been like taking a piece of his life and giving it to someone carelessly. But now for the first time such giving was not pain. He saw, not the silver in the alien hand of a merchant in the town; he saw the silver transmuted into something worth even more than itself—clothes upon the body of his son.”

“They cannot take the land away from me. the labor of my body and the fruit of the fields I have put into that which cannot be taken away. If I had the silver, they would have taken it. if I had bought with the silver to store it, they would have taken it all. I have the land still, and it is mine.”

“Yet never could he grasp her wholly, and this it was which kept him fevered and thirsty, even if she gave him his will of her.”

“There in that land of mine is buried the first good half of my life and more. It is as though half of me were buried there, and now it is a different life in my house.”

“It seemed to him that now his life was rounded off, and he had done all that he said he would in his life and more than he could ever have dreamed he could.”

See also: Inspirational Quotes by Pearl S. Buck

“When people in the city become fearful, the city life becomes more and more unbearable to Wang Lung who constantly yearns for the land. He even thinks seriously about selling his daughter if only it would enable him to return to his land.”

“Wang Lung forgets the land for awhile when he is sick in love with Lotus. When Lotus comes to his house, he is plagued by various domestic problems, but when the waters in the fields recede and Wang Lung is able to work his land, he is immediately healed of his sickness. Earth is a healing agent for Wang Lung.”

“Wang Lung is so attached to his land that despite the threat his bandit uncle poses to his family, he cannot move to town for fear of living without his land close by.”

More about Pearl Buck on this site

Pearl Buck Talks of her Work

1938 Nobel Award for Literature to Pearl Buck

6 Feminist Quotes by Pearl Buck

Pearl Buck’s 1973 obituary

Inspirational Quotes by Pearl S. Buck

Three Poems from Words of Love by Pearl S. Buck

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 2, 2018

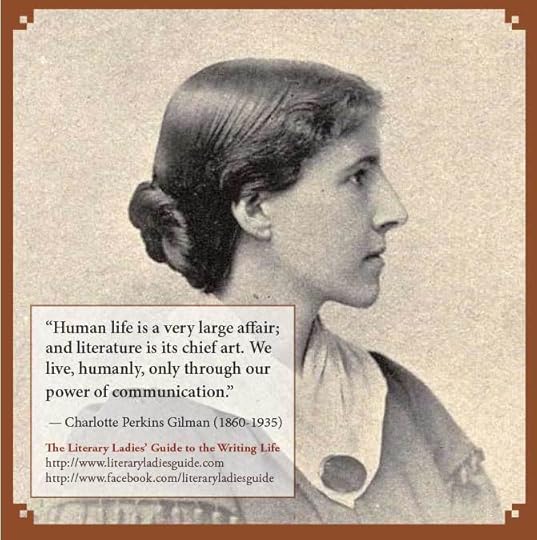

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (July 3, 1860 – August 17, 1935) was an American author of fiction and nonfiction, praised for her feminist works that pushed for equal treatment of women and for breaking out of stereotypical roles.

She was one of the was one of the leading activists in the late 19th and early 20th century American women’s movement. Her nonfiction works on how women’s lives were impacted by social and economic bias are still relevant. Today, she’s best known for the semi-autobiographical work of short fiction, The Yellow Wallpaper.

Early life

Born in Hartford, Connecticut, Charlotte was the daughter of Mary Perkins and Frederic Beecher Perkins. When she was an infant, her father abandoned the family. Mary was unable to support Charlotte and her brother, but fortunately, they were assisted by her father’s family. Among the notable Beechers of Hartford were her great-aunts, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Isabella Beecher Hooker, and Catharine Beecher. All were involved in women’s rights and it’s interesting to ponder how much Charlotte was influenced by them.

Charlotte also spent part of her childhood in Providence, Rhode Island. Her formal education was spotty, ending when she was just fifteen. Her mother showed little affection for her and her brother, yet discouraged them from making friends or reading.

When she was about eighteen, Charlotte reconnected with her absent father, who encouraged her to attend the Rhode Island School of Design. She began taking classes in 1878, and for a time, supported herself as an artist and private tutor.

Battle with postpartum depression

In 1884 Charlotte married Charles Stetson an artist. At first, she refused his proposal, feeling that he wasn’t right for her. As it turned out, she should have followed her instinct. Within their first year she gave birth to their daughter, Katharine Beecher Stetson. She succumbed to a serious bout of post-partum depression, exacerbated by the prevailing attitudes that women were frail creatures given to hysteria.

Stetson wasn’t inclined to allow her to do any activities to further herself, which led to her already depressed state to worsen. This experience was the basis for her 1892 semi-autobiographical novella (or long short story) The Yellow Wallpaper, arguably her best known work. More on this ahead.

Starting to flourish

By 1888, Charlotte left Charles Stetson. It can’t be overstated how rare this was for the time. She and her daughter Katharine moved to Pasadena, California. There she started becoming involved with feminist causes and organizations, and began writing and editing. She immersed herself in suffrage and was also taken up with labor and socialist organizations.

When Charlotte and husband weren’t formally divorced until 1894, he remarried at once. She sent Katharine to live with Charles and his second wife, stating in her memoir that Charles and Katharine had a right to know and love one another. She also felt that Stetson’s new wife would be just as good a mother to Katharine — perhaps even better — as she.

It was during these active, tumultuous years that Charlotte embarked on her path as a serious writer. In 1890, she had her first poem published and wrote more poetry, some fifteen essays, a novella, and what would become her best-known work, The Yellow Wallpaper. The latter first appeared in the New England Magazine in 1892.

During these years, she also became a lecturer, which became an important source not only of income, but of connection with like-minded feminist and social activists. She spoke about the issues that mattered to her: human rights, women’s issues, labor, social reform, and more.

The Yellow Wallpaper (1892)

What would become Charlotte’s most famous work was written in two days in June, 1890 in her Pasadena home. It was first published in the January, 1892 issue of New England Magazine and has since been included in numerous anthologies, including collections of American literature, women’s literature, textbooks, and of course, anthologies of her own work.

Charlotte draws on her personal experience with the postpartum depression she suffered from. For the sake of her health, as advised by her husband and physician, she’s isolated in a room and becomes fixated on its strange and ugly yellow wallpaper. The story is a statement on women’s lack of independence and on being at the mercy of physicians and other patriarchal forces to the detriment of their mental health. You can read the full text here and an analysis here.

Later, in an essay titled “Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper” (1913) Charlotte observed:

“For many years I suffered from a severe and continuous nervous breakdown tending to melancholia — and beyond. During about the third year of this trouble I went, in devout faith and some faint stir of hope, to a noted specialist in nervous diseases, the best known in the country.

This wise man put me to bed and applied the rest cure, to which a still-good physique responded so promptly that he concluded there was nothing much the matter with me, and sent me home with solemn advice to “live as domestic a life as far as possible,” to “have but two hours’ intellectual life a day,” and “never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again” as long as I lived. This was in 1887. I went home and obeyed those directions for some three months, and came so near the borderline of utter mental ruin that I could see over.”

Read the rest of the essay here.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman page on Amazon

Women and Economics (1898)

When Charlotte moved back east in 1893, she made contact with Houghton Gilman, a first cousin who was a Wall Street attorney. The two became romantically involved and were married in 1900. She was apparently much happier and more fulfilled in her second marriage. In the intervening years, Charlotte continued to write, edit, and lecture.

She herself experienced some bias as an unconventional mother and as a divorced wife. She began to think about the social forces that oppressed women — even relatively privileged women. Shedding a light on the economic and social discrimination that forced women into second-class citizenship was the mission of her 1898 book, Women and Economics: A Study of the Economic Relation Between Men and Women as a Factor in Social Revolution. This hugely successful book, which was reprinted many times and translated into seven languages, is unfortunately still relevant today.

This classic treatise explored the roles of women in American society, particularly on the impacts of marriage and motherhood. She argued that motherhood wasn’t exclusive to working outside the home, that domestic tasks ought to be professionalized, and most of all, that women shouldn’t have to be financially dependent on men. It’s now considered a classic treatise from the first-wave feminist movement.

You might also like: Charlotte Perkins Gilman on feminist ideals

A prominent career

The Home: Its Work and Influence (1903) expanded on the themes in Women and Economics, and was equally influential. She pushed for women to rise up in the workforce and to expand their lives beyond homemaking and childbearing.

Charlotte wrote, edited, published, and promoted her own magazine, The Forerunner, from 1909 to 1916. In it she presented some of her fiction, including Herland (1915) which would go on to great renown in the future as a feminist utopian novel.

After closing down The Forerunner, Charlotte wrote hundreds of essays and articles for various publications, and in 1925, began her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, which would be published in 1935, just after her death.

Controversial views on race and immigration

Charlotte was so progressive in her views and theories about gender equality that it’s jarring to learn about some of her views on race and immigration. Her views in the 1909 essay A Suggestion on the Negro Problem is incredibly racist; there’s no way to sugar-coat it.

And she held rather nationalistic views for someone so dedicated to equality. She had harsh words at times for immigrants, for example, that they were diluting the “reproductive purity” of Americans of British decent. She famously said of herself “I am an Anglo-Saxon before everything.” She has been labeled a “eugenics feminist.”

Later years and legacy

In 1932, Charlotte was diagnosed with terminal breast cancer. In 1934, her husband died of a sudden cerebral hemorrhage, and she moved to Pasadena to be near her daughter. The following year, she committed suicide by overdosing on chloroform.

Gilman left behind a suicide note stating that she chose chloroform over cancer. Published verbatim in the newspapers, it further read, “When all usefulness is over, when one is assured of unavoidable and imminent death, it is the simplest of human rights to choose a quick and easy death in place of a slow and horrible one.”

Gilman will always be remembered for her visionary feminist writings, lectures, and passion for social justice and women’s rights. During her lifetime she was a tireless activist and lecturer for the causes she was passionate about. In 1994 she was welcomed into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and named one of the most influential women of the twentieth century.

Her legacy continues through her powerful literature. Her works are bold and progressive and relatable to future generations of feminists. Unfortunately, her nationalistic, racist, and anti-immigrant stances means that the good that she did needs to be balanced with the harmful aspects of her thinking.

See also: Books by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

More about Charlotte Perkins Gilman on this site

8 Feminist Quotes

On Feminist Ideals

Gilman’s 1911 Version of “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”

Charlotte Perkins Gilman Quotes

“Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper” (1913)

Women and Economics (1898) — an excerpt

The Giant Wistaria — an analysis

The Yellow Wallpaper — an analysis

Books by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Full texts on this site

The Yellow Wallpaper

The Giant Wistar ia

Major Works

Charlotte Perkins Gilman was incredibly prolific. This represents a tiny fraction of her output, which also included essays, stories, and poetry, not all of which ended up in book form.

The Yellow Wallpaper (1892)

Women and Economics (1898)

What Diantha Did (1909 –1910)

The Crux (1911)

Moving the Mountain (1911)

The Man-Made World; Or, Our Androcentric Culture (1911)

Herland (1915)

With Her in Ourland (1916)

Autobiographies and Biographies

The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: An Autobiography

The Abridged Diaries of Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Biography by Cynthia Davis

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Gilman’s books on Goodreads

The Evolution of Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Read and listen online

Gilman’s books on audio on Librivox.org

Project Gutenberg

8 Feminist Quotes by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Charlotte Perkins Gilman appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 1, 2018

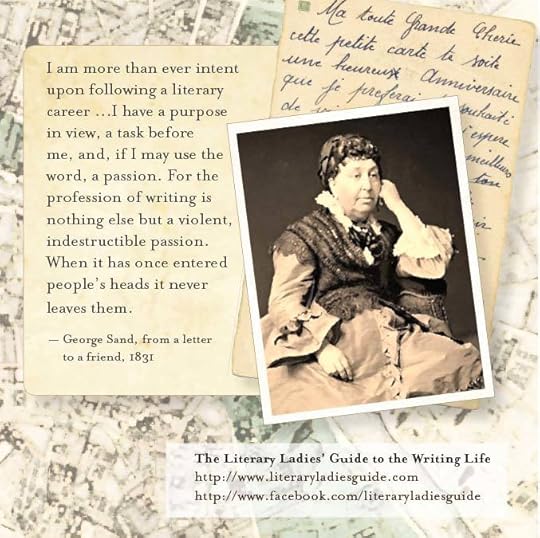

George Sand

George Sand (born Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin; July 1, 1804 – June 8, 1876) was a French novelist, essayist and playwright. She was also known for pushing the envelope on gender roles and the drama in her everyday life, not the least of which were her countless romantic entanglements.

Some put her literary legacy at eighty novels, others at seventy, in addition to several plays and countless shorter works, including: essays, journalistic pieces, and a multi-volume autobiography. It would be nearly impossible for any contemporary writer to emulate such prolific output, but she remains a model for creating a full palette of love, productivity, and family.

Early life and first marriage

In her youth, Aurore, as she was called, lived and studied for a time in a convent. When she returned home, she studied nature and the works of philosophers. Her penchant for wearing men’s clothing later in her life may have been planted by her tutor, who encouraged her to wear trousers and shirts while riding horses, something she loved doing, as it gave her a feeling of freedom.

Aurore was only 19 when she married Casimir Dudevant, the son of a baron and a servant girl. Not a bad sort, though crude, he didn’t live up to her romantic expectations of what a husband should be. She left him eight years later — leaving their two children behind as well. She was off to Paris and started earning her own living by writing articles. Imagine how revolutionary this was for a woman in the early 1830s! It was at this time that she also began associating with other writers, some of whom became her mentors; others, her lovers.

Quotes by George Sand on Life, Love, and Work

Becoming George Sand

When Aurore fell in love with the charming young writer Jules Sandeau, they began collaborating on some writings and were collectively “J. Sand.” Soon after, she began using George Sand as her own pseudonym, starting with her first novel, Indiana (1832). It was a controversial novel from the start, and she enjoyed telling critics just where they could get off in a later edition of the book.

After her affair with Sandeau ended, she took up with Alfred de Musset, a poet. It was during the time of this relationship that she took custody of her daughter, Solange, while her husband, from whom she was legally separated, kept their son, Maurice.

Immensely productive

George Sand made a habit of pleading pity for her “literary agonies.” Despite her complaints, the word “prolific” is woefully inadequate to describe her output. Aside from her published books, she also wielded a journalistic pen to give voice to her concerns for women’s rights and social justice.

She started her own newspaper right around the time of the revolution of 1848 to disseminate her progressive and socialist views. When the revolution began that year, women had no legal rights, and Sand felt strongly that no society could advance under those circumstances. Yet despite how attuned she was to injustice, she managed to remain an optimist.

After publishing Indiana, she went on to write Lélia (1833), Mauprat (1837), Consuelo (1843), Le Meunieer d’Angibault (1845), and many others. Autobiographical works such as Elle et Lui, about her affair with Musset, were also part of her literary output. She ran a small private theater at her Nohant estate, at which she staged the plays she wrote, and sometimes performed in them.

Despite her own protestations to the contrary, George Sand found the discipline to produce an immense body of work. Until her surprisingly mellow older age, she was more adept at self-flagellation than self-congratulation.

George Sand on the Agony and Ecstasy of the Writing Life

Many lovers

You can be sure that the Masterpiece Theatre version of Sand’s life focused more on her adventures in the bedroom than at her desk. Her most notable love interest was legendary composer Frederic Chopin, and her most controversial, with the glamorous actress Marie Dorval.

George Sand was on the whole an adoring mother, but for her, motherhood was often fraught with the kind of drama that colored many of her relationships. Her son Maurice was a major mama’s boy, causing petty jealousy for Sand’s live-in lover, Frédéric Chopin. Could it have been from spite that he unconsciously (or not so unconsciously) fell in love with Sand’s daughter, Solange, when she was a pretty and flirtatious young lady of seventeen?

Her well-known love life, though tumultuous, was something on which she thrived, evidenced by this well-known quote of hers: “There is only one happiness in life, to love and be loved.”

Expressions of the masculine

One of the earliest and best-known cross-dressers, she wore men’s clothing both for comfort (for traveling, which she loved, apparently trousers were more practical than crinolines) and to make a statement. Similarly, she was famed (and mocked) for her public cigar-smoking, and never went far without her hookah.

In Lélia: The Life of George Sand, André Maurois writes touchingly: “Those who came to see the notorious lady who wore trousers and smoked cigars found instead a passionate and dedicated mind that transcended any of her gaudy poses. For in revolting against the conventions of the world, George Sand felt and suffered very much as a woman.”

You might also like: The Mellowing of George Sand

Paving the way for women

George Sand was admired by many of the leading figures of her day, with whom she developed abiding friendships, with or without love affairs. Notable among them were Franz Liszt, Victor Hugo, and George Henry Lewes. Lewes, one of the leading literary critics of the time wrote of her that she was “the most remarkable writer of the present century.” She maintained an abiding friendship and correspondence with fellow author Gustave Flaubert.

Though her oversized biography and persona are perhaps better known in the English-speaking world, her work was much admired by many of her literary contemporaries. It was, however, considered unseemly and completely unfeminine by others. Not to diminish her work, but to some observers, her importance seemed to be more for the courage and originality of her life than her literary output.

A mellow old age

George Sand inherited an exquisite estate in Nohant, located in the Indre region of central France, which today is open to visitors. Before settling there permanently in her later years, she used it as a retreat from hectic city life in Paris There she hosted a legion of writers and artists with whom she was friendly, including Delacroix, Turgenev, Flaubert, Liszt, and Balzac.

Aimee MacKenzie wrote in her 1921 introduction to The Gustave Flaubert-George Sand Letters: “In her final retreat at Nohant, surrounded by her affectionate children and grandchildren, diligently writing, botanizing, bathing in her little river, visited by her friends and undistracted by the fiery lovers of the old time, she shows an unguessed wealth of maternal virtue, swift, comprehending sympathy, fortitude, sunny resignation, and a goodness of heart that has ripened into wisdom.”

She located to this idyllic locale permanently for her last years. She loved to work in the garden, and tended to her grandchildren. More about her later golden years can be found in The Mellowing of George Sand: Mother, Grandmother, Gardener.

To her critics, Sand wrote, “The world will know and understand me someday. But if that day does not arrive, it does not greatly matter. I shall have opened the way for other women.” Those who knew her well and admired her acknowledged her dual nature, as Elizabeth Barrett Browning famously wrote, “Thou large-brained woman and large hearted man,” in her poem, George Sand: A Desire.

George Sand died at Nohant on June 8, 1876, not quite 72 years of age.

More about George Sand on this site

George Sand on the Agony and the Ecstasy of the Writing Life

The Mellowing of George Sand

“To George Sand: A Desire” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Indiana by George Sand: The Author Answers Her Critics

Quotes by George Sand on Life, Love, and Work

Major Works (Novels)

This is but a tiny fraction of George Sand’s prodigious, almost ridiculously prolific output. She wrote and published many novels, as well as some one dozen plays and countless essays and other works of nonfiction.

Indiana (1832)

Valentine (1832)

Lélia (1833)

Jacques (1833)

Mauprat (1837)

Consuelo (1842)

La Mare au Diable (1846)

Le Petite Fadette (1849)

Biographies and Autobiographies

Story of My Life: The Autobiography of George Sand

George Sand by Elizabeth Harlan

George Sand: A Biography by Curtis Cate

Lélia: The Life of George Sand by André Maurois

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Sand’s works on Goodreads

Listen and read online

George Sand on Project Gutenberg

Audio versions of Sand’s books on Librivox

Visit George Sand’s home

Nohant – The George Sand estate in Nohant, France

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post George Sand appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Louisa May Alcott

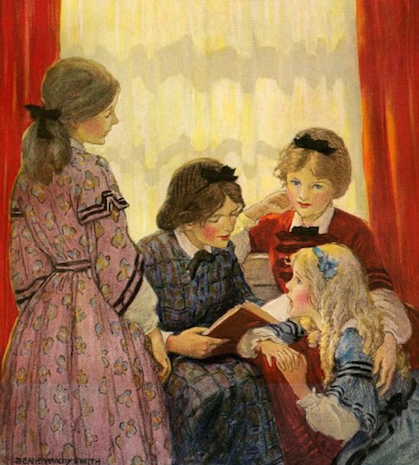

Louisa May Alcott (November 29, 1832 – March 6, 1888) is best known as the author of Little Women and its sequels, including Jo’s Boys and Little Men, though the scope of her work goes far beyond these beloved books. She also wrote essays, poems, and pseudonymous thrillers. Alcott was born in Germantown, Pennsylvania, and grew up in Boston and Concord, Massachusetts.

Alcott’s most beloved heroine, the complicated and talented Jo March, was an idealized version of herself. And she did grow up in a family much like the one she presented in Little Women — once again, idealized and a bit altered — with practical and wise Marmee, a dreamer of a father, and three sisters, May (“Amy”), Anna (“Meg”), and Elizabeth (“Beth”).

Like Louisa, Jo was the aspiring writer among the sisters. What’s less well-known is that Alcott produced a large body of thrillers (otherwise known as gothics or sensational tales) under various pseudonyms, allowing her to support her family while searching for her literary voice. Contrary as they seemed to her own life and values, she seemed to take some perverse pleasure in dark themes, returning to them even after financial need no longer compelled her to do this sort of formula writing.

You may also enjoy

10 Women Writers Who Were Inspired by Jo March

Determined to make a living as a writer

Alcott conducted her career as a professional determined to profit from her pen. Financial need stoked her drive as she became the primary breadwinner in her family at a young age. Inspiration was all around her, as she grew up in the midst of the Transcendentalists. Her father, Bronson Alcott, was one of its most passionate and radical proponents. He was a brilliant social theorist, but a poor provider, causing continuous financial stress for the family.

Louisa admired Charlotte Brontë and longed to gain recognition for her work, much as Brontë had. Though Alcott claimed that her greatest reward was the esteem of the “young folks” who were her readers, she was never modest in her demands to be paid what she felt she was worth, and lived to see her work earn a fortune. Most important to her was to make her family, especially her Marmee, comfortable.

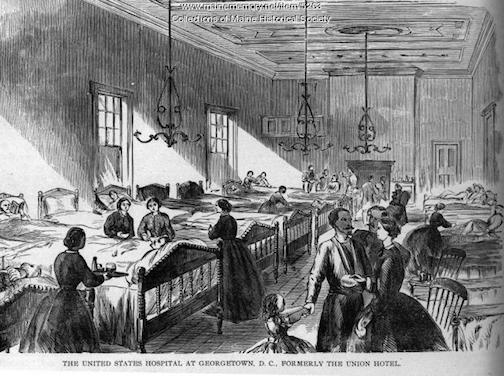

A brief stint as Civil War nurse

During the Civil War, Louisa would have surely taken up arms if women had been allowed to serve as soldiers. But the only way women could serve was to volunteer as nurses, and that’s just what she did. After the crushing defeat of Union forces in Fredericksburg, December 1862, Louisa began her duties as a nurse at the Union Hotel in Georgetown, Washington D.C.

Disease was nearly as much a threat as wounds from the battlefield — not only to the soldiers themselves, but to those who cared for them. Not even a month into her service, Louisa came down with typhoid pneumonia, complete with a horrendous cough and a high fever. Her father came to fetch her and take her home, and she was in a delirium for some time after. More about this in her own civil war journals.

Louisa May Alcott as Civil War nurse

Little Women

Though Alcott had already produced the well-received Moods (the first novel under her real name), Work: A Story of Experience, Hospital Sketches, and countless small pieces under her own name, it was Little Women that really put her on the map. In 1868, her publisher asked that her to try writing a “girls’ story” for their list.

Thinking little of the request, she cranked it out in two and a half months, though her heart wasn’t in it. Neither she nor her publisher thought it was in any way remarkable. Still, the proof of the entire book was ready in a month or so after the author turned in the manuscript, and once it came out, it was an immediate success, so much so, that sequels quickly followed.

More about how Louisa May Alcott came to write Little Women

A staunch feminist and abolitionist

She promoted women’s rights and campaigning for women’s suffrage. Her views were espoused by her lead characters, strong young women who wanted more from life than to get married and have babies. Alcott herself never married nor had children. She and her family were always ardent abolitionists, a view that was not as widely popular in relatively liberal Massachusetts as one would think.

Naïve about her sexuality

Despite all that she’d seen in life, Alcott was he was alarmingly naïve about the nature of her sexuality. She confessed in an 1883 interview: “I am more than half-persuaded that I am a man’s soul, put by some freak of nature into a woman’s body … because I have fallen in love in my life with so many pretty girls and never once the least bit with any man.” Perhaps unknowingly, the repressed nature of her sexuality helped her avoid the circumscribed path of marriage and motherhood, and allowed her to view the institution dispassionately.

Here are some of Louisa May Alcott’s best loved quotes

A brief experience with motherhood

May Alcott Niereker, the youngest Alcott sister, trained as an artist in Europe (subsidized by Alcott’s earnings). There she met a man, married, and had a daughter. She died within a year of giving birth. Alcott wanted to raise the child, and earned the father’s family’s consent do so. Adopted at the age of two, the little girl was her Aunt Louisa’s namesake (and nicknamed Lulu); from all accounts, the nine years they spent together before Alcott’s death were happy ones.

Chronic illness and death

Louisa May Alcott was 55 years old when she died of a stroke in Boston in 1888. Her death came just two days after her father’s. She had long suffered from chronic illness, thought to have been caused by the mercury-laced medicine she took as a cure for the typhoid fever she suffered while serving as a nurse during the civil war. However, modern scholars believe that she may have had an autoimmune disease, perhaps lupus.

You might also like 10 Life Lessons from Louisa May Alcott

More about Louisa May Alcott on this site

10 Women Writers Who Were Inspired by Jo March

Louisa May Alcott quotes

How Louisa May Alcott’s Feminism Explains Her Timelessness

How Alcott Came to Write Little Women

A Visit to the Alcott’s Orchard House

Sweet Success at Last for Louisa May Alcott

10 Life Lessons from Louisa May Alcott

A Feminist Manifesto — Work: A Story of Experience

A Posthumous Interview with Louisa May Alcott

Madeleine B. Stern’s Brilliant analysis of Little Women

When You Don’t Have Enough Time to Write

The Boundless Hearts of Mothers

Comfort and Guidance in Little Women

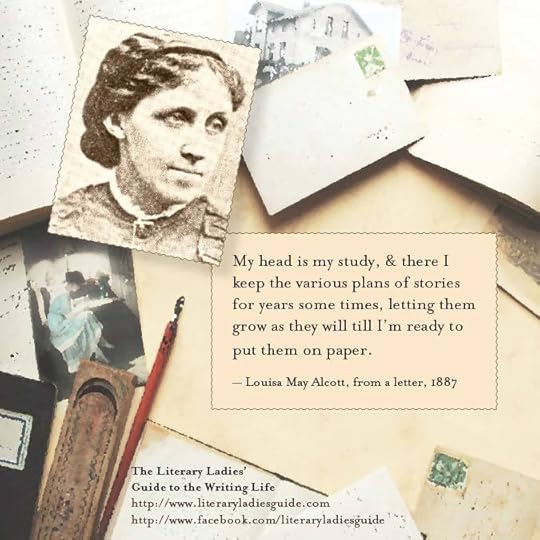

My Head is My Study

“March” by Geraldine Brooks: A Review

Behind a Mask: The Unknown Thrillers of Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott’s Obituary, March 1888

May Alcott Nierker: Thoroughly Modern Woman

Sketch of Childhood

LMA as Civil War Nurse

LMA’s Civil War journals

Dear Literary Ladies: Any Quick Tips for Plot and Character Development?

Dear Literary Ladies: How Can a Writer Improve Her Craft?

Dear Literary Ladies: Isn’t There an Easy Road to Writing Success?

Major Works

Little Women

Jo’s Boys

Little Men

Rose in Bloom

Eight Cousins

Hospital Sketches

An Old-Fashioned Girl

Under the Lilacs

Moods

Work: A Story of Experience

Transcendental Wild Oats (full text)

A Long Fatal Love Chase

Biographies About Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott: A Biography by Madeline B. Stern

The Woman Behind Little Women by Harriet Reisen

Eden’s Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father by John Matteson

Louisa: The Life of Louisa May Alcott by Yonda Zeldis McDonough

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Alcott’s books on Goodreads

Louisa May Alcott page on Amazon.com

LMA’s books on Project Gutenberg

Audio readings of LMA’s books on Librivox

Film and TV adaptations of Louisa May Alcott Works

Little Women (1933)

Little Women (1949)

Little Women (1994)

Little Men (1935)

Little Men (1941)

Little Men (1998)

The Inheritance (1997)

The Inheritance (2003)

An Old Fashioned Thanksgiving (2008)

Visit Louisa May Alcott’s Home

Orchard House – Concord, MA

The Wayside – Concord, MA

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Louisa May Alcott appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Must-Read Novellas by Classic Women Authors

If you’d like a taste of a classic author’s work but don’t have the time or patience to read a tome, consider the novella form. Here we’ll look at novellas by classic women authors that make great introductions to to their work.

What defines a novella? It’s generally based on word count of between 17,000 and 40,000, though it isn’t always so cut and dry. The Awakening by Kate Chopin is often described as a novella, though its outside that parameter. The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman is about 6,000 words, yet has often been published as a stand-alone book (as well as in collections of this author’s stories). In terms of some standard definitions, that doesn’t even qualify as a novelette.

As far as page count, in a paper edition, depends on the size the font is set in, and the trim size of the paper. I personally view a novella as a work that’s under 200 pages in printed form — enough to sink your teeth into, yet never overwhelming.

In the hands of a skillful writer, a lot can be packed into a novella. Let’s go with a simple dictionary definition of the novella — “a work of fiction intermediate in length and complexity between a short story and a novel.” If you have any other suggestions for novellas by women authors of the past, comment below and we’ll add them to this post.

The Lifted Veil by George Eliot (1859)

The Lifted Veil by George Eliot is a shorter work by the British author best known for weighty books like Middlemarch. that departs sharply from the usual realism that’s a hallmark of her fiction. Latimer, the book’s unreliable narrator, is a sensitive intellectual who believes that he can see into the future and read the thoughts of others. It was the first and only of George Eliot’s works to delve into the genre of science fiction; this novella might also be considered horror and makes much use of suspense.

Transcendental Wild Oats by Louisa May Alcott (1873)

Transcendental Wild Oats by Louisa May Alcott is a satire, somewhere in length between a novelette and novella, about her family’s misadventures as part of the Fruitlands community in the 1840s. Alcott thinly disguised the members of the Transcendentalist community, most notably, her father, Amos Bronson Alcott, who was a co-founder of the community. You can read this work in its entirety on this site.

The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1892)

The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman remains a classic in feminist literature. Some might consider it a longer short story rather than a novella, but either way, it feels like it belongs on this list. In her 1913 essay, “Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper,” Gilman revealed that the story was a reflection of the postpartum depression she suffered from, and her hopes that it would enlighten other women who experienced it.

But just as important, it’s a story of a woman whose creativity and freedom are thwarted by the strict gender roles proscribed by her time, culture, and class. You can read the full text here.

The Awakening by Kate Chopin (1899)

The Awakening is a short novel by Kate Chopin, published in 1899. It’s the story of Edna Pontellier, who struggles with her role as wife and mother in the stratified social milieu of New Orleans in the late 1800s. Now considered a feminist classic, it was met with mixed reviews at best upon its original publication. It was banned by many libraries and bookstores, only to be rediscovered, and is now considered a masterpiece of feminist fiction. Here is the full text.

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (1911)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton is admittedly depressing, but so beautifully told that many readers return to it again and again. An original 1911 review sketches the outline of the tale: “Twenty years before the tale opens we learn that Ethan Frome has been crippled in a terrible accident … Ethan had his old parents to take care of and after their death he married the young woman who had helped him to nurse them … In a few years she needed assistance, so a young poor relation, Mattie Silver, came to live with them. Slowly she and Ethan fell in love.” What happens next isn’t “happily ever after.”

Lost Laysen by Margaret Mitchell (1916)

Surprise! Lost Laysen, a novella by Margaret Mitchell, the author of the Gone With the Wind, was found decades after her death. According to the publisher: “The impossible has happened: the world has another story from Margaret Mitchell. Written in 1916, when the author was in her mid-teens, it’s a delight — a fitting predecessor to America’s most beloved epic novel. A spirited tale of love and honor on a doomed south Pacific island called Laysen, Lost Laysen would be justly praised as a charming effort by a remarkable young talent if it were its author’s only work.”

The Ballad of the Sad Café by Carson McCullers (1951)

The Ballad of the Sad Café by Carson McCullers centers around the eccentric Miss Amelia, owner of the formerly thriving café. When a hunchback wanders into town, followed by Amelia’s her shiftless former husband, emotions swell and collide. A review of the story from the year in which it was published offered this praise:

“McCullers with the fine hand of a craftsman and the insight of a poet explores the emotions of jealousy and loneliness in the troubled depths of abnormal personality.” The Ballad of the Sad Café gives a brief but compelling introduction to the work of this classic Southern writer.

The Ponder Heart by Eudora Welty (1954)

The Ponder Heart by Eudora Welty is a 1954 novella originally published in The New Yorker magazine the year before it appeared in book form. Narrated by Edna Earle Ponder, it’s the story of her uncle, Daniel Ponder, a sweet man who is considered a bit “slow.” He has inherited a hefty fortune from his father and wants to give it away. Not surprisingly, his plan is opposed by the extended family. This charming story was turned into a Broadway play as well as a made-for-television film.

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys (1966)

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys is the last work by this Dominican-British author. Considered a prequel and response to Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, the novella presents the perspective of Antoinette Cosway, the sensual Creole heiress who wound up as the “madwoman in the attic.” This short novel became her most successful novel, praised for its spare yet evocative language and its exploration of the power imbalance between men in women, between patriarchal colonizers and the original inhabitants of the Caribbean in the 1830s.