Nava Atlas's Blog, page 2

August 13, 2025

The Lives of Iconic Women Poets in Documentaries & Biopics

Presented here is a collection of documentaries and biopics exploring the lives of iconic women poets: Maya Angelou, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Julia de Burgos, Emily Dickinson, Ingrid Jonker, and Sylvia Plath.

On the surface, it wouldn’t seem like a full-length film about a poet would be anything to write home about, so to speak. But behind their deep, soulful lines were complex lives, not always spent at a desk.

Best of all, most of the films in this roundup can be viewed gratis on YouTube by following the links provided.

. . . . . . . . . .

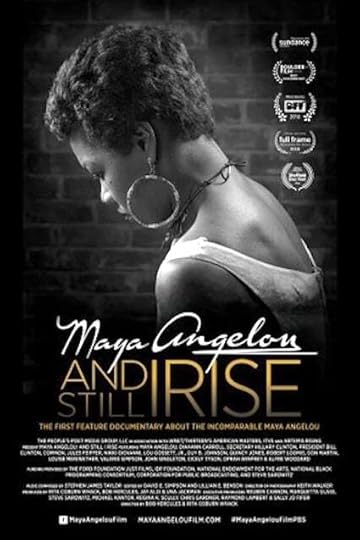

Maya Angelou: And Still I Rise

This 2017 documentary about Maya Angelou, who personifies the “Phenomenal Woman” of her famous poem, is available to view gratis on YouTube. The description from the producer, BBC One:

“Documentary portrait of the trail-blazing activist, poet and writer Maya Angelou. Born in 1928, she enthused generations with her bold and inspirational championing of the African-American experience that pushed boundaries and redefined the way people think about race and culture.

Maya Angelou was captured on film just before she died in 2014, and this documentary celebrates her life and work, weaving her words with rare and intimate archival photographs and videos.

It reveals hidden episodes of her exuberant life during some of America’s defining moments, from her upbringing in the Depression-era south to her work with Malcolm X in Ghana and her inaugural speech for President Bill Clinton, the film takes us on an incredible journey through the life of a true American icon. Contributors include Bill Clinton, Oprah Winfrey, Quincy Jones, Hillary Clinton, and Maya Angelou’s son Guy Johnson.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Burning Candles:The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay

Burning Candles: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay is a documentary celebrating the iconic American poet. It’s available to view gratis on YouTube. From the producer’s description of the 2009 film:

“Encouraged to read the classics at home, she was too rebellious to make a success of formal education, but she won poetry prizes from an early age, including the Pulitzer Prize in 1923, and went on to use verse as a medium for her feminist activism. She also wrote verse-dramas and a highly praised opera, The King’s Henchman.

Millay was a prominent social figure of New York City’s Greenwich Village just as it was becoming known as a bohemian writer’s colony, and she was noted for her uninhibited lifestyle, forming many passing relationships with both men and women. She was also a social and political activist and those relationships included prominent anti-war activists.

She became a prominent feminist of her time; her poetry and her example, both subversive, inspired a generation of American women. Her career as a poet was meteoric. She became a performance artist super-star, reading her poetry to rapt audiences across the country.”

. . . . . . . . . .

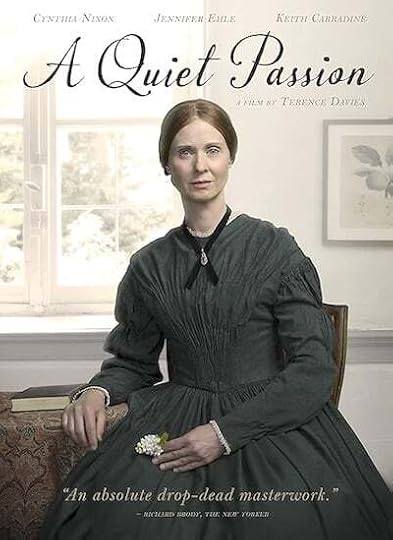

Film critics loved Terence Davies’s A Quiet Passion, but Emily Dickinson fans gave this 2016 biopic mixed reviews, as you can see in the Amazon reviews.Though it’s a beautifully photographed film, one wonders how much “poetic license” was taken with the story of the brilliant poet who rarely strayed from her family’s Amherst home.

Some viewers objected to how Emily and her family are portrayed in the film, feeling that it took too many liberties. I’m more on the thumbs-down side of this film. It took me bit of adjustment to accept as the poet, having become used to seeing her as Miranda on Sex and the City. Her performance can be commended, but scenes of Emily’s illness and what seem like seizures seemed over the top.

At the very least, the film can nudge us to read more of Emily Dickinson’s breathtaking poetry. Here are 10 of her well-loved poems, a mere fraction of her incredible output.

. . . . . . . . .

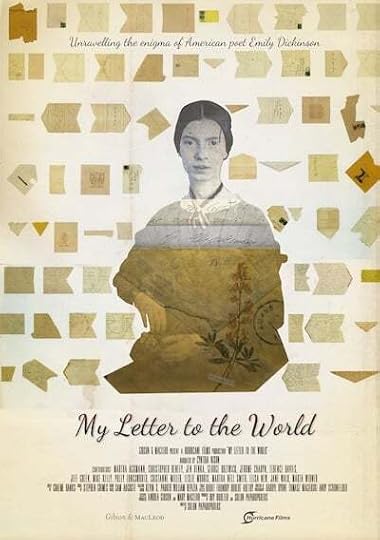

My Letter to the World (Emily Dickinson)

If you prefer a documentary to a fictionalization like the one above, My Letter to the World came out in 2018, not long after A Quiet Passion, above. The same producers of the latter created this documentary. From Music Box Films:

“An in-depth exploration of the life and work of the great American poet Emily Dickinson, narrated by Cynthia Nixon. Bringing to light new theories about Dickinson’s personal relationships and most revered work, this feature documentary rewrites the widely accepted narrative of the poet as a strange recluse in white, and breathes new life into the Dickinson legacy over 130 years after her death.”

Watch the trailer of My Letter to the World.

. . . . . . . . .

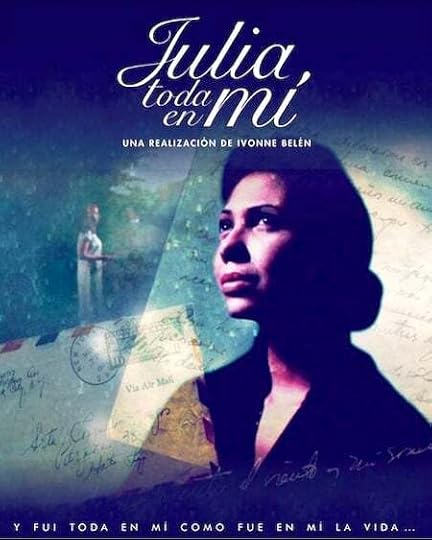

Julia, Todo en Mí (Julia de Burgos)

This 2002 film is a docudrama — part documentary, part re-enacted — about the esteemed Puerto Rican poet Julia de Burgos. A lovely Spanish language film with English subtitles, it’s available to watch for free on YouTube. Here, the description is translated by Google Translate & edited by yours truly (a student of Spanish!):

“Julia, All in Me offers a poetic journey through the life, literary work, and humanistic thought of Puerto Rican Julia de Burgos, who Nobel Prize winner Pablo Neruda prophesied as “one of the great poets of the Americas.” The story of Julia de Burgos is told in her own voice, through fragments of the letters she wrote to her sister Consuelo, from her voluntary exile in New York and Cuba from 1940 until her early death in 1953.

Historical moments—the Spanish Civil War, World War II, the social and political climate in Puerto Rico, New York, Cuba, and Europe—are intertwined with Julia’s loves and passions, described with a revelatory vision that transcends time. This moving epistolary testimony is intertwined with the participation of personalities from Puerto Rico and abroad, who read her poems and pay a beautiful tribute to the island nations distinguished poet Julia de Burgos.”

Enjoy this selection of poems by Julia de Burgos in their original Spanish and in English translation.

. . . . . . . . .

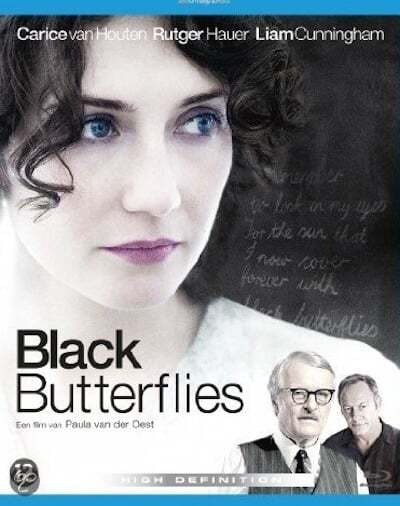

Black Butterflies (Ingrid Jonker)

Ingrid Jonker (1933 – 1965) was a South African poet and founder of the emerging counterculture literary movement of her time. Her views and work strongly opposed the apartheid government of the time. From the producers, here’s a brief description of Black Butterflies, a fictionalized biopic (2012):

“Poetry, politics, madness, and desire collide in the true story of the woman hailed as South Africa’s Sylvia Plath. In 1960s Cape Town, as Apartheid steals the expressive rights of blacks and whites alike, young Ingrid Jonker finds her freedom scrawling verse while frittering through a series of stormy affairs.

Amid escalating quarrels with her lovers and her rigid father, a parliament censorship minister, the poet witnesses an unconscionable event that will alter the course of both her artistic and personal lives … As a woman governed by equal parts genius and mercurial gloom, Jonker could inspire passion but never, it seems, love — a sad truth critically conveyed by van Houten. Jonker’s inner turmoil mirrored her country’s upheaval, but van der Oest is never heavy-handed with her parallels of the poet and the South African maelstrom happening around her.”

Like several other films in this roundup, it’s available to watch in full on YouTube, gratis.

. . . . . . . . .

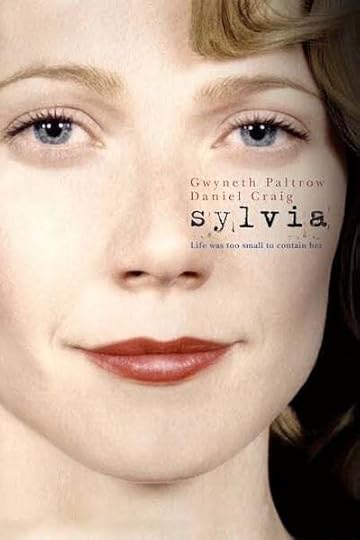

Sylvia (Sylvia Plath)

Of course, I have to mention Sylvia, the 2002 biopic starring Gwyneth Paltrow. She was a great casting choice for the brilliant American poet Sylvia Plath (with Daniel Craig as Ted Hughes, her husband and fellow poet in their awful marriage), but the film received tepid reviews at best, and audiences had mixed reactions. In this lengthy article, the screenwriter details the difficulties of bringing Plath’s tragic life to film.

It’s now quite difficult to find the film online, though holdouts with DVD players might have more luck finding it through their local library systems. Here’s the official trailer.

There don’t seem to be any documentaries of a full scale — that is, 90 minutes or so — about Sylvia Plath. This one from 1988, part of the Voices and Visions series nearly does the job at 56 minutes. It’s available to watch on YouTube. However, its production values make it a bit dated and dull, so if you do want to watch it, do so with lowered expectations.

The post The Lives of Iconic Women Poets in Documentaries & Biopics appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 10, 2025

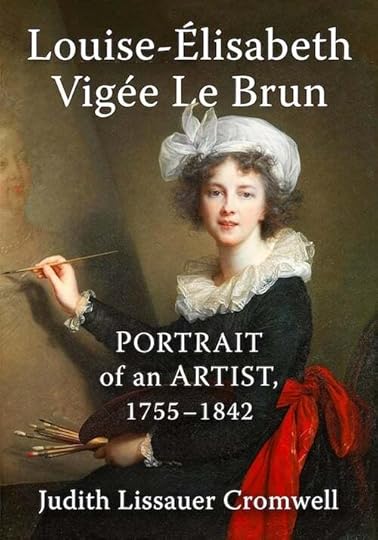

10 Fascinating Facts About Louise-Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

The latest biography from historian Judith Lissauer Cromwell, Louise-Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun: Portrait of an Artist, 1755–1842 (McFarland, 2025), follows the remarkable life of this painter whose portraits of European royalty and nobility hang in many of the world’s most important museums.

As a young woman in the male-dominated society of 18th-century France, Louise-Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun was denied an artistic education and forced to nurture her passion outside of conventional schooling. Vigée Le Brun’s vibrant art, in addition to her charm and beauty, caught the attention of Queen Marie-Antoinette, who honored her as her chosen painter.

At the pinnacle of her fame and fortune, however, the Revolution forced Vigée Le Brun to flee, leaving everything behind except her only child, a daughter.

Drawn from Vigée Le Brun’s memoirs, archival research, and reexamination of the judgment of her contemporaries, this biography paints a fascinating picture of a single working mother who survived because of her cachet, charisma, and artistic talent.

Cast on a storm-tossed continent, solely reliant on her palette, she produced some of her major works during her twelve-year exile, returning to France to continue her work after Napoleon had restored stability. Vigée Le Brun’s story is one of triumph, adversity, perseverance and ultimately, peace.

Judith Lissauer Cromwell has contributed 10 fascinating facts about Louise-Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, a painter whose life and work merits wider recognition.

Vigée Le Brun was a feminine icon in her day

Famed throughout Europe and North America for her portraits, Vigée Le Brun, a lover of art, music, letters, and nature, had traveled widely. She knew everybody who mattered in the European world of culture and politics and had painted many of them.

. . . . . . . . . .

Portrait of Quieen Marie Antoinette

by Louise-Elisabeth Vigee-Lebrun, Versailles Museum

. . . . . . . . . .

She was Queen Marie-Antoinette’s favorite artistMarie-Antoinette’s exacting mother, the Empress of Austria, wanted a formal portrait of her daughter as Queen of France. Several prominent male artists had, over a ten-year period, failed to please. Desperate, Marie-Antoinette decided to try a young female artist who had become the fashion in Paris. Vigée Le Brun’s Marie-Antoinette in Full Court Dress succeeded. This joint triumph created a bond between queen and artist.

Vigée Le Brun painted many portraits of Marie-Antoinette. Some went to the queen’s friends in foreign countries, others to French embassies in foreign capitals. King Louis XVI presented a formal portrait of himself and of Marie-Antoinette (by Vigée Le Brun) to the US Congress to mark the birth of the new nation. Exposure as the French queen’s painter brought her universal fame.

Vigée Le Brun was basically self-taughtBarred from a traditional art education because of her gender, Vigeé Le Brun relied on herself to nurture her passion for painting and her ambition to be a great artist. She developed her unique style by studying master painters.

. . . . . . . . . .

At age twenty, the painter made a marriage of convenience to a prominent Parisian art dealer, mainly to escape an unhappy home life. He was not “a bad man,” Vigée Le Brun tells us, “his nature showed a great mixture of sweetness and vivacity; he treated everyone very kindly…a likeable person. But his reckless passion for women of ill repute, combined with his lust for gambling, resulted in the loss of his fortune and mine, which he fully controlled.”

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun divorced his wife during her exile, which allowed the painter full control of her earnings so that when she returned to France, Vigée Le Brun had enough to live on comfortably.

. . . . . . . . . .

Louise-Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun: Portrait of an Artist, 1755–1842

is available wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . .

Her pretty face, attractive figure and sense of fashion, her charm and gift for making friends, but above all her talent and determination to succeed, propelled the young painter into the top echelons of scintillating Old Régime society.

The only artist with a salon in the heyday of Paris salons, Vigée Le Brun’s salon attracted prominent members of the bohemian world of arts and letters and aristocrats bored by the stiff formality of Versailles. It did not matter if the simple food ran out, or a prince of the blood had to sit on the floor because there were not enough chairs; music, laughter, and good conversation satisfied everyone.

She was fashion-forward

Frustrated by the Versailles court’s formal, ornate, and uniform dress with its stiff corsetry, its blank rouged faces under elaborately coiffed hair, Vigée Le Brun persuaded her sitters to wear simple, pliant, muslin dresses and shawls, unpowdered, naturally arranged hair, and minimal makeup. Vigée Le Brun made an effort to get to know her subjects so that she could portray them as vital human beings.

Having helped to promote a simpler way of dressing in Paris, Europe’s fashion capital, Vigée Le Brun introduced her style to St. Petersburg, where she spent half of her twelve-year exile. The new fashion became so popular that aristocratic ladies were able to convince an extremely reluctant Catherine the Great to allow it at official court functions.

Vigée Le Brun suffered vicious calumny

The public’s love of reading salacious gossip about the rich and famous stimulated the fertile imagination of pamphleteers. Pre-revolutionary Paris buzzed with made-up tales, especially about Marie-Antoinette and, since she and Vigée Le Brun were as much friends as two women of such disparate social levels could be, some of the fabricated mud flung at the queen spattered onto her favorite painter.

Vigée Le Brun could ill afford to ignore the slander because, as a female artist, her credibility depended on keeping her spotless reputation. The lies Parisian pamphleteers spread about Vigée Le Brun were a major reason for her flight from Paris as the Revolution ramped up.

. . . . . . . . . .

Julie Le Brun by Louise Elisabeth Vigee Le Brun

(image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Open Access)

. . . . . . . . . .

Vigée Le Brun adored her only child. She took pretty little Julie with her into exile, lavished love and attention on her, and made sure she had an excellent education. At age nineteen Julie fell in love with a handsome nonentity. Vigée Le Brun opposed their marriage; the ensuing fracas revealed Julie’s less attractive qualities and caused an irreparable rift with her mother. The marriage ended badly; and syphilis led to Julie’s early death.

Vigée Le Brun wrote her memoirs

Reflecting on her legacy towards the end of her life, on the cruel and unmerited slander she, as a successful woman in a man’s world, had suffered, Vigée le Brun decided to seize control of her life story by creating her last self-portrait. Souvenirs recounts Vigée Le Brun’s life as she wanted posterity to know it; Souvenirs also presents posterity with Vigée Le Brun’s last, vivid, and richly colored depiction of the Old Régime.

Her paintings have two-fold importance

Today, Vigée Le Brun’s paintings hang in some of the world’s most important galleries, not only for their artistic value but also because she immortalized many of Europe’s movers and shakers at a time when the West stood at the cusp of the modern age.

. . . . . . . . . . .

About the author, Judith Lissauer Cromwell: After a successful corporate career, Judith returned to academia as an independent historian and biographer of powerful women. Her experience as a magna cum laude graduate of Smith College, holder of a doctorate in modern European history with academic distinction from New York University, veteran of corporate America, mother, and grandmother, enrich Cromwell’s perspective on strong women in history.

She is the author of the biographies Dorothea Lieven: A Russian Princess in London and Paris, 1785-1857; Florence Nightingale, Feminist; and Good Queen Anne: Appraising the Life and Reign of the Last Stuart Monarch. Her latest biography, Louise-Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun: Portrait of an Artist, 1755-1842 provides a fresh and balanced perspective on the life of a renowned, yet often overlooked, painter. Learn more about Judith’s work at JudithCromwell.com.

. . . . . . . . . .

Comtesse de la Châtre (Marie Charlotte Louise Perrette Aglaé Bontemps, 1762–1848)

by Louise-Elisabeth Vigee Le Brun

(image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Open Access)

What inspired you to write about Vigée Le Brun?

I had never heard of Vigée Le Brun until New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art held a retrospective of her work. Reviewers praised the exhibit, so I went to see it. Vigée Le Brun’s

paintings were riveting, her brief introductory biography intriguing. This remarkable woman, I vowed to myself, would be the subject of my next book.

Why is Vigée Le Brun, the most sought after portraitist in late 18th and early 19th century Europe, not well-known today?

Until the present day, art historians (mostly male) have generally tended to ignore female artists. Because of her association with Marie Antoinette and the court at Versailles, Vigée Le Brun became famous as a court painter. Certainly, she focused on the aristocracy and the French

court before the Revolution, but both before and after the Revolution, her work, indeed, some of her most celebrated paintings, are not of aristocrats.

What is the most surprising thing you discovered about Vigée Le Brun?

The tremendous hurdles she faced in achieving her goal to become a great artist. What a multi-faceted woman she was. How the political events she lived through affected her even though she had little to no interest in politics. Her resilience; how she managed to continue her brilliant career during twelve years of exile far from her beloved family and homeland.

Why have you focused on only fifty of Vigée Le Brun’s paintings when her complete oeuvre includes around eight hundred? How did you decide which paintings to include in your biography?

Rather than cramming into the book as many illustrations as possible from Vigée Le Brun’s copious work, I decided to highlight paintings that are either especially important in her life or exemplify her most illustrious efforts.

Why does Vigée Le Brun’s art, life, and legacy matter to readers today?

Despite incredible odds, she achieved her childhood goal of becoming a great artist early in life. Aside from her art and the fame it brought her, Vigée Le Brun’s diverse interests, not to mention her looks, charm, and social position (everyone who mattered in the world of culture, society, and politics knew her) made Vigée Le Brun a feminine icon. Dedication to her art brought Vigée Le Brun solace in times of stress and happiness regardless of life’s knocks.

Which museums hold a selection of Vigée Le Brun’s paintings? Where should readers go to see her art in person?

New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Louvre (Paris) currently have some of Vigée Le Brun’s paintings on view; The Hermitage, (St.Petersburg, Russia); the National Gallery, (London); and the Versailles et Trianon museums (Versailles, outside Paris) all own several of Vigée Le Brun’s paintings.

The post 10 Fascinating Facts About Louise-Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 30, 2025

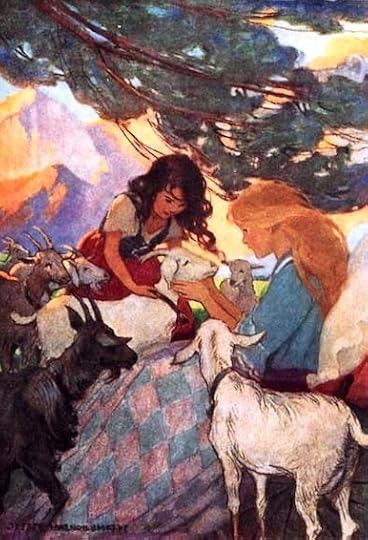

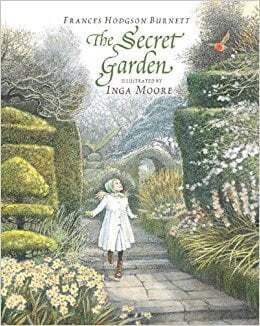

The Healing Effects of Nature in Heidi and The Secret Garden

Johanna Spyri and Frances Hodgson Burnett illustrate the effects of nature on well-being through the symbolism and imagery of nature in their novels, Heidi and The Secret Garden. In both of these beloved classic novels, the authors show how the characters’ interactions with nature sets them on transformative journeys that help heal physical ailments and mental distress.

Spyri’s Heidi (1881) follows a young girl who has lost her parents and is taken to the Swiss Alps to stay with her grandfather. Mary Bernath, literature professor at Bloomsburg State University, writes that “Heidi’s home in the Alps is an idyllic place, far from the modern world and its concerns.”

After a short time, she is sent to the city of Frankfurt to be a companion to Klara, a slightly older girl who is unable to walk. While in Frankfurt, Heidi falls ill and yearns to return to the natural world of the Alps.

Burnett’s The Secret Garden (1911) shares with Heidi a theme of nature playing a role in healing various physical and psychological ailments. It has “remained a timeless classic for its themes of friendship and the power of nature to heal the body and spirit,” according to Literary Ladies Guide.

The Secret Garden’s Mary is an orphan, like Heidi. She loses her parents to a cholera epidemic in colonial India and must return to England to stay with a remote uncle at his estate. There, Mary unlocks a neglected garden, and as she “cares for the plants in the garden with the help of her cousin Colin Craven, its restorative powers help her overcome her grief.” (Garden Museum).

Each protagonist goes through a unique journey. Heidi withers in Frankfurt and thrives in the Alps. Mary’s discovery of the garden in the heart of her uncle’s estate helps her find peace and health through the environment. When discussing these characters’ journeys, Nava Atlas stated that “they had to develop a determined spirit, overcome obstacles, and gain a sense of independence.”

Both stories contain the trope in which an invalid returns to health by strengthening their relationship with nature.

. . . . . . . . .

Klara visits Heidi — illustration by Jessie Wilcox Smith

. . . . . . . . .

Johanna Spyri uses goats to symbolize a relationship with nature and to suggest that the interaction can uplift mental well-being. In Frankfurt, Heidi was “under the constant scolding of the housekeeper, who would not let her cry, the child was repressing her homesickness and unhappiness, and she began walking in her sleep.”

When she is able to return to the Alps from Frankfurt, she’s ecstatic to see her friends and grandfather. When Peter arrives with the goats, “Heidi was delighted to see them all again. She put her arm around one and patted another. The animals pushed her this way and that with their affectionate nudgings.” While Heidi is delighted to be reunited with her human and animal friends, the goats’ affection demonstrates a symbiotic relationship. Heidi’s excitement at the reunion greatly contrasts with her depressed state in Frankfurt.

Burnett uses a robin to symbolize Mary’s relationship with nature. In The Secret Garden, the robin has a more discreet role but still provides emotional support to Mary. When she sees this robin while outside playing, it becomes a kind of a companion to her. Seeing the robin again reminds her “of the first time she had seen him. He had been swinging on a treetop then and she had been standing in the orchard.

Emma House, curator of The Secret Garden exhibit at the Garden Museum, commented that “the robin has sort of a practical use because he helps find the key and the opening to the garden … by using the robin to find the garden, she is keeping the garden in the children’s world.”

The robin has a less direct presence in Mary’s life, since she sees it from afar, whereas Heidi interacts directly with the goats. In both novels, the animals help the characters heal from past experiences. In Heidi’s case, the goats provide excitement and joy after her homesick and miserable stay in Frankfurt. For Mary, the robin is familiar and safe, leading her to a world where she can heal from her traumas.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Plant Symbolism in Heidi & The Secret GardenSpyri uses plants, especially flowers, to symbolize nature’s ability to assist healing. After Heidi’s return, Klara visits her in the Alps for few weeks; during this time, Klara learns to walk. The girls explain “how Klara’s desire to see the flowers had induced her to take the first walk, and so by degrees one thing had led to another.”

Here, the flowers that inspired Klara to walk are symbolic of her growing connection with nature. This journey happens by small degrees over an extended period, demonstrating a relationship with natural world that’s most effective over time, rather than a one-time cure.

In The Secret Garden, Colin, who is unable to walk, goes through a transformation that can be compared with Klara’s. Shortly before learning to walk, Colin is in the garden, planting a rose. His “thin white hands shook a little and Colin’s flush grew deeper as he set the rose in the moulds and held it while old Ben made firm the earth.”

After spending time in the garden, the rose acts as a symbol of Colin’s newfound relationship with the natural world, and enjoying its benefits. At first he can barely leave his bed; then he is able to spend time in the garden, and is finally being able to stand and walk.

While Klara and Colin are in different environments, they undergo similar transformations. Richard Almond, a professor at Stanford College of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, states that “Klara’s recovery is like Colin’s … where multiple influences, including that of nature, contribute to the overcoming of developmental blocks.”

In her analysis of The Secret Garden, Janet Grafton, English professor at Vancouver Island University, states that “Burnett’s belief in the connection between environment and health are inherent and implacable.”

This is represented in both novels through the children’s journey in nature, where they are compelled to eventually take, their first steps. Atlas stated in our interview that “The wonders of the natural world in both books offer a promise of health, strength, and happiness.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Heidi and Peter — illustration by Jessie Wilcox Smith

. . . . . . . . . .

Spyri uses flowers as a symbol to display the negative effects of separation from the natural world. Upon finding some beautiful flowers in the mountains, Heidi puts them in her apron to bring home: “But the poor flowers, how changed they were! Heidi hardly knew them again. They looked like dry bits of hay, not a single little flower cup stood open.

“Oh grandfather, what’s the matter with them?” exclaimed Heidi in shocked surprise, “They were not like that this morning, why do they look like that now?”

“They like to stand out there in the sun and not to be shut up in an apron,” said her grandfather.

Burnett similarly uses the garden’s change and growth as a symbol the characters’ journeys. When Mary first finds the secret garden, “There were neither leaves nor roses on them now, and Mary did not know whether they were dead or alive, but their thin gray or brown branches and sprays looked like a hazy mantel spreading over everything.”

The garden is in a state of disarray, like Mary’s own state as she copes with the loss of her parents. As she works in the garden, she and the plants grow and heal together.

Initially, “the neglected garden represented lost hopes, secrets, and life in decline,” said Atlas, but it slowly became stronger under Mary’s care. On the other hand, the lively flowers shriveled away when Heidi removed them from their natural surroundings. The authors create change in the plants to reflect the characters’ journeys from illness and health.

Conclusion

In their classic novels, Frances Burnett and Johanna Spyri convey the intricate relationship between humans and nature. As modern technology develops, it becomes increasingly challenging to stay in touch with nature. It has been interesting to ponder how the humans relationship with nature changed since Heidi and The Secret Garden were written.

Now, more than ever, it is important to stay connected nature, as so eloquently conveyed by Johanna Spyri and Frances Burnett in their timeless tales.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Further reading and sourcesAlmond, Barbara, and Richard Almond. “Heidi (Johanna Spyri): The Innocence of the Child as a Therapeutic Force.” Children’s Literature Review, edited by Tom Burns, vol. 115, Gale, 2006.

Atlas, Nava. “Heidi by Johanna Spyri (1881).” Literary Ladies Guide, 22 May 2024

Bernath, Mary G. Heidi. Children’s Literature Review, edited by Tom Burns, vol. 115, Gale, 2006. Gale Literature Resource Center; originally published in Beacham’s Guide to Literature for Young Adults, edited by Kirk H. Beetz and Suzanne Niemeyer, vol. 2, Beacham Publishing, 1990. Accessed 18 April 2024.

Burnett, Frances. The Secret Garden (originally published in 1911) London, Puffin Classics edition, 2015.

Children’s Literature Review. “Heidi.” Children’s Literature Review, edited by Tom Burns, vol. 115, Gale, 2006. Gale Literature Resource Center

Garden Museum. “The Secret Garden.” Garden Museum, 24 Aug. 2022

Grafton, Janet. “Girls and Green Space: Sickness to Health Narratives in Children’s Literature.” Children’s Literature Review, edited by Lawrence J. Trudeau, vol. 215, Gale, 2017. Gale Literature Resource Center. Originally published in Knowing Their Place? Identity and Space in Children’s Literature, edited by Terri Doughty and Dawn Thompson, Cambridge Scholars, 2011

Nejade, Rachel M et al. “What is the impact of nature on human health? A scoping review of the literature.” Journal of global health vol. 12 04099. 16 Dec. 2022,

Silver, Anna Krugovoy. Wuthering Heights and The Secret Garden: A response to Susan E. James.” Connotations, vol. 12, no. 2-3, May 2002, pp. 194+. Gale Literature Resource Center

Spyri, Johanna. Heidi (originally published in 1881). London, Arcturus Publishing Limited 26/27 Bickels Yard edition, 2019.

The post The Healing Effects of Nature in Heidi and The Secret Garden appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

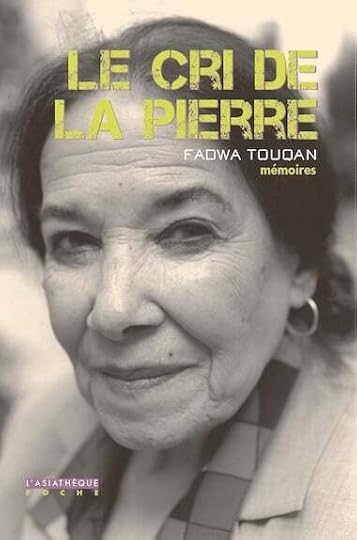

Fadwa Tuqan: From Societal Suppression to Poetess of Palestine

Despite the challenges and pressures that Palestinian women writers have historically faced from displacement, occupation, and societal pressures, prominent writers have emerged steady and strong, whether in Palestine or exiled in the diaspora. Poet Fadwa Tuqan (1917 – 2003) was one of these women.

Palestinian women writers, like other women writers across the globe, did not have it easy, especially those who lived through the Nakba. This was the 1948 catastrophe when more than 700,000 Palestinians were displaced from historical Palestine (modern day Israel) to Gaza, the West Bank, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon.

Added to this displacement were societal pressure and cultural norms that put women at a disadvantage compared to their male peers.

Early life in Nablus

Fadwa Tuqan is now known as “the poetess of Palestine.” She was born in Nablus, a city in northern Palestine, in 1917, into an affluent family who lived in a large home inherited from their ancestors.

Fadwa grew up in a male-dominant household and society, and was shunned by her father — he was hoping his newborn would be a boy. Her mother tried to abort her and threw the “burden” of raising Fadwa onto their housemaid. Her mother took away all her dolls when she was eight, and when Fadwa shared stories using her imagination her mother would brush them off as “nonsense.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

House of Al-Bayk Tuquan, courtesy of Yalla Falasteen

. . . . . . . . . . .

Many of her writings described the environment and male-dominated society she grew up in, where “women were prisoners between walls.” Though her family was wealthy and could easily afford her schooling, her brother Yousef removed her from the education system while she was in elementary school due to “societal pressures;” he found out that a boy who was fond of Fadwa was following her home from school.

Her brother Ibrahim went off to study literature at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon. After his graduation in 1929, he was determined to help his sister continue her studies. He taught Fadwa the art of rhyming in Arabic poetry. She began submitting her poems to literary magazines in Cairo and Beirut under pseudonyms, gaining self-confidence as her work was accepted and published.

Ibrahim Tuqan, who became a reknowned Palestinian poet in his own right, writing the Arab national poem “Mawtini” (now the national anthem of Iraq), was the only one of her brothers that fully supported her.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

In Jerusalem and LondonIn 1939, Fadwa left Nablus to live with Ibrahim in Jerusalem, where she finally broke free of the walls in which her family had confined her for so long. In Jerusalem, Fadwa was introduced to a society of poets, writers, and politicians, became active in literary and cultural clubs, and started going to the library and cinema.

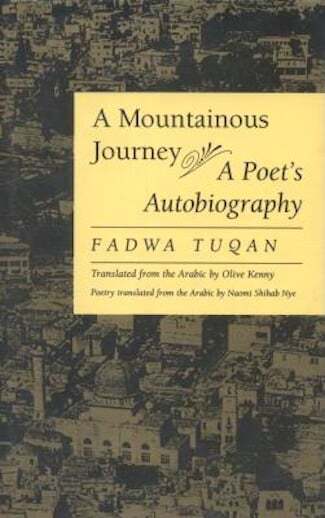

In A Mountainous Journey: A Poet’s Autobiography, Fadwa wrote about her difficult and unfair life, including how she contemplated suicide multiple times. In Jerusalem, she began taking English lessons at an evening school at the YMCA so that she could begin reading and self-studying English Literature.

In 1962, Fadwa moved to London for two years where she took courses in English and Literature at Oxford University continuing her self-development and learning journey.

Upon returning from London, Fadwa decided to claim her autonomy, away from the confines of her family and the society in which she had grown up. She built her own house in the west of Nablus, where she continued to live independently.

As with her poetry, she knew her family would never accept her marriage to a stranger from another country. Her first love was Egyptian lyricist and poet Ibrahim Naja, about whom she had written some of her best poetry. Their relationship remains alive through her poetry for him and the love letters they had exchanged.

. . . . . . . . . . .

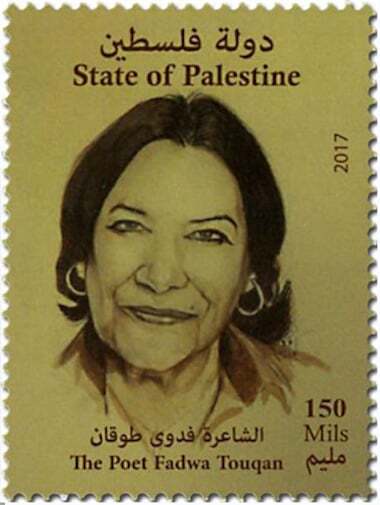

Stamp commemorating Fadwa’s centenary

. . . . . . . . . . .

EXISTENCE

Translated by Michael R. Burch

In solitary life, I was a lost question;

In the encompassing darkness,

my answer was concealed.

You were a bright new star

radiating light from the darkness of the unknown,

revealed by fate.

The other stars rotated around you

—once, twice —

until it came to me,

your unique radiance.

Then the bleak blackness broke

And in the matching tremors

of our two hands

I found my missing answer.

Oh you! Oh you intimate, yet distant!

Don’t you remember the coalescence

Of your spirit in flames?

Of my universe with yours?

Of the two poets?

Despite our great distance,

Existence unites us – Existence!

Grieving a beloved brother; and the Nakba

Fadwa witnessed the Nakba in 1948 and didn’t remain silent. She was part of the Jordanian delegation for a peace conference organized by the World Peace Council in Stockholm and later delegations to Holland, the Soviet Union, and China. After the death of her beloved brother and mentor Ibrahim in 1941, her father urged her to write political and national poetry to steer her away from the emptiness she was feeling after losing Ibrahim.

But she resisted and instead published her first poetry collection in 1946, My Brother Ibrahim, as a way to grieve her loss. It was only after her father’s death in 1948 that she start writing nationalist and resistance poetry without anyone’s influence.

Her resistance poetry had such an impact that Moshe Dayan, commander of the Jerusalem front in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war said that Fadwa’s poetry was the equivalent of facing twenty enemy fighters.

MY SAD CITY

translated by Charlie Huntington

“On the day of Zionist occupation”

The day we saw the death and deception,

The floods fell back,

The windows to heaven closed,

And the city held its breath.

Day the waves retreated, day that

The ugliness of the abyss

Exposed its face to the light.

Hope burned

As an agony of misfortune strangled

My sad city.

Gone are the children and songs;

Not a glimpse, not an echo

The sorrow in my city crawls shamefully,

Staining her steps.

The silence in my city –

Silence like mountains at rest,

Like a dark night, a painful silence

Burdened with the weight of death and defeat.

Alas! Oh, my sad, silent city

Are you thus at harvest time,

Your crops and fruits aflame?

Alas! Oh, what an end!

Alas! Oh, what an end!

Fadwa is considered a feminist of her time; although she was forced to leave elementary school and never completed her education with a degree, she fought her way through her life and career becoming the first Palestinian female poet, publishing eight poetry collections between 1946 and 2000.

Selections of her poetry have been translated into more than five languages, including Hebrew, and her two autobiographies, A Mountainous Journey and The Most Difficult Journey, were translated and published in English in 1990 and 1993 respectively.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

A Mountainous Journey is a compilation of all her journal entries until 1967. In The Most Difficult Journey she speaks of her life under the occupation after the Palestinian Nakba in 1948 and the 1967 Naksa. A documentary of her life was produced by Palestinian Novelist Liana Badr titled Fadwa: A Poetess from Palestine. Her life was featured on Al Jazeera Documentary, and Ilam Media also produced a short film about her after her death. You can watch it here with English subtitles.

On December 12, 2003, Fadwa passed away in her hometown of Nablus, leaving behind a legacy of political activism, literature, and a new path for Palestinian women writers to follow.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Lama Obeid, a writer from Palestine. Her poem “My Father a Refugee” has been published in the anthology To Lay Sun into a Forest, published by Sidhe Press. Lama enjoys experimenting with poetry and fiction, and hopes to become a published author of an anthology and a memoir in the future. Lama also publishes her writing on her Substack, I Come From There.

Further reading

7 Poems by Fadwa Tuqan Fadwa Tuqan’s Legacy as a Feminist Icon A Romantic Feminist Poet and Reluctant Political Witness You may also enjoy: Samira Azzam, Journalist, Broadcaster, and Short Story WriterThe post Fadwa Tuqan: From Societal Suppression to Poetess of Palestine appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 23, 2025

Gertrude Bell, English archeologist, writer & traveler

Gertrude Bell (1868 – 1926) was an English archeologist, writer, and translator. She traveled extensively in the Middle East and advocated for Arab nationalism before settling permanently in Baghdad and contributing to the nation building of the Kingdom of Iraq.

She published several books about her travels and her archeological excavations. She corresponded extensively with many friends, colleagues and policy makers during her whole life.

Gertrude was outspoken and independent from an early age. She studied modern history at Oxford University and developed a passion for archeology and languages. The support of her father, English industrialist Hugh Bell, and the family fortune helped her achieve her passion.

She became fluent in Arabic, Persian (Farsi), French, and other languages, which proved essential to interact with the local population during her travels.

She authored the translation of the poetry collection The Divān of Hafez, published in London in 1897. Hafez, a 14th-century Persian lyric poet, wrote his poems in Persian (Farsi) and Arabic.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Exploring and mapping the Middle EastGertrude spent many years exploring and mapping the Middle East, and participating in several archeological excavations. As she was fluent in Arabic and Persian (Farsi), she established close relations with local inhabitants, local tribes and local policy makers.

She advocated for the creation of independent Arab states and advised the British government against fighting with nationalists. She authored intelligence reports and white papers and, as such, was labelled the first female diplomat in the region.

After settling permanently in Baghdad in 1919, Gertrude became a key player in the nation building of the Kingdom of Iraq. Because of her background as an archeologist, she was appointed the director of the new Department of Antiquities in order to organise and regulate archeological excavations and to prevent the looting of antiquities.

She participated in the creation of the Baghdad Archeological Museum (later renamed Iraq Museum and also known as National Museum of Iraq) and the Baghdad Public Library (later renamed National Library of Iraq), and supported the education of Iraqi women.

Gertrude Bell’s writings

She wrote several books, including:

Persian Pictures (1894), about her first travels to PersiaSyria: The Desert and The Sown (1907) about her trip to Damascus, Jerusalem, Beirut, Antioch and other placesA Thousand and One Churches (with English archeologist William Mitchell Ramsay, 1907) about their excavations in AnatoliaAmurath to Amurath (1911) about her archeological work in MesopotamiaThe Palace and Mosque of Ukhaidir: A Study in early Mohammadan Architecture (1914) about the ruins of Ukhaidir in Mesopotamia. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The Legacy of Gertrude BellGertrude corresponded extensively with many friends, colleagues and policy makers during her whole life, including with fellow British archeologist and diplomat Thomas Edward Lawrence (better known as T. E. Lawrence, and popularly as “Lawrence of Arabia”), a lifelong colleague and friend, and with her stepmother Florence Bell, a writer and playwright who had married her father in 1876 after the death of Gertrude’s mother (who was his first wife).

According to the obituary penned by her colleague David George Hogarth in 1926:

“No woman in recent time has combined her qualities – her taste for arduous and dangerous adventure with her scientific interest and knowledge, her competence in archeology and art, her distinguished literary gift, her sympathy for all sorts and condition of men, her political insight and appreciation of human values, her masculine vigour, hard common sense and practical efficiency – all tempered by feminine charm and a most romantic spirit.”

One year after her death, a selection of her extensive correspondence (out of 2,400 pages of letters) was edited by her stepmother Florence Bell and published in two volumes as The Letters of Gertrude Bell (1927).

Further reading (& viewing) about Gertrude BellThe Incredible Life and Adventures of Gertrude Bell (documentary) The Death of Gertrude Bell Gertrude Bell (Historic UK) The Incredible Gertrude BellContributed by Marie Lebert. Edited by Nava Atlas, Literary Ladies Guide.

The post Gertrude Bell, English archeologist, writer & traveler appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 22, 2025

Mary Louise Booth (1831–1889), abolitionist and translator

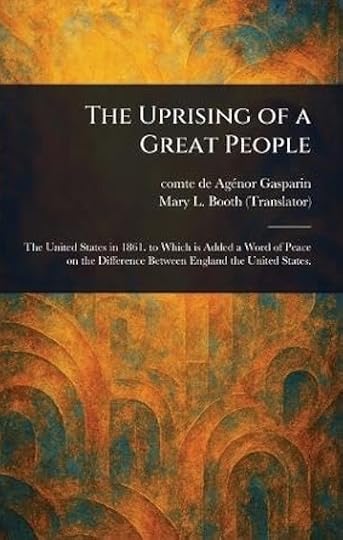

Mary Louise Booth (1831–1889), was an American writer and a prominent translator from French to English. At the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861, she translated the French anti-slavery advocate Agénor de Gasparin’s seminal book Uprising of a Great People (1861) for it to be quickly distributed in the United States.

She became the first editor of the American fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar in 1867.

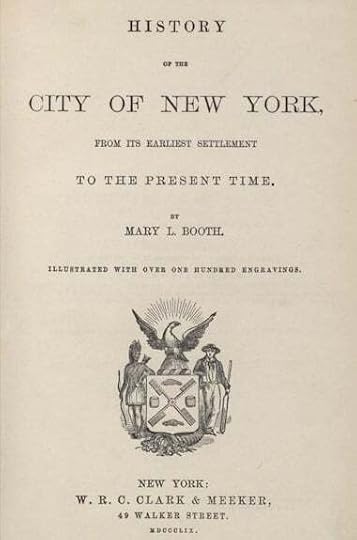

Born in Millville (now Yaphank) in the State of New York, Booth was of French descent on her mother’s side. After moving to New York City at the age of eighteen, she wrote tales and sketches for newspapers and magazines and also worked as a translator. She wrote History of the City of New York (1859), which became a bestseller.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Works translated by Mary Louise Booth

She is estimated to have translated up to forty books. Her first translation from French to English was The Marble-Worker’s Manual (1856), followed by The Clock and Watch Maker’s Manual.

She also translated some works by French writers Joseph Méry, Edmond François Valentin About, and Victor Cousin. She assisted the American translator Orlando Williams Wight in producing a series of translations of French classics.

At the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861, she translated the French statesman and anti-slavery advocate Agénor de Gasparin’s seminal work Uprising of a Great People (original title: Un Grand Peuple qui Se Relève, just published in France) in a very short time by working twenty hours a day for one week. The American English edition was published in a fortnight by Scribner’s, a well-known publisher. The book caused a sensation and she received many appreciative letters for her contribution to abolitionism.

Mary Louise translated other books by anti-slavery advocates, including Agénor de Gasparin’s America before Europe (L’Amérique devant l’Europe) in 1861, politician Augustin Cochin’s Results of Emancipation and Results of Slavery (the two volumes of L’Abolition de l’Esclavage) in 1862, and jurist Édouard René de Laboulaye’s Paris in America (Paris en Amérique) in 1865.

She also translated non-political books, including Agénor de Gasparin’s religious works (written with his wife), Édouard René de Laboulaye’s Fairy Book (Contes Bleus), educator Jean Macé’s Fairy Tales (Contes du Petit-Château), historian Henri Martin’s History of France (Histoire de France”), and philosopher Blaise Pascal’s Provincial Letters (Lettres Provinciales”).

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Mary Louise Booth as editor of Harper’s BazaarShe was the first editor of Harper’s Bazaar, the American fashion magazine created in 1867, and kept the position for more than twenty years until her death in 1889.

Under her leadership, the magazine steadily increased its circulation and influence. After struggling financially for years as a writer and translator, she earned a larger salary than any other woman in America.

Further reading The Long Island History Project Mary Louise Booth is as Good a Friend as Ever Yaphank New York Historical Society, Mary L. Booth BirthplaceContributed by Marie Lebert. Edited by Nava Atlas, Literary Ladies Guide.

The post Mary Louise Booth (1831–1889), abolitionist and translator appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 19, 2025

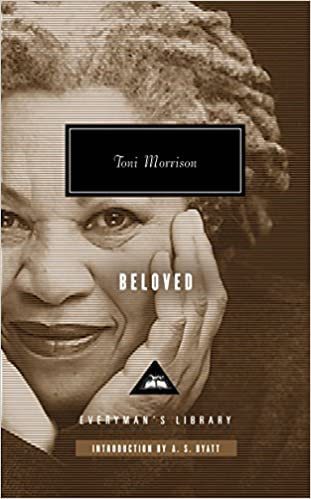

Toni Morrison as Visionary Editor: “Black People Talking to Black People”

Toni Morrison (born Chloe Ardelia Wofford, 1931 – 2019) is celebrated for her groundbreaking novels and nonfiction that examine the Black experience in America.

Her writings have reached millions of readers, and she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993 for the “visionary force and poetic import” of her work. [above right, Toni Morrison’s author photo on The Bluest Eye, 1970; photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

Following is an overview of her career as an editor and publisher, which isn’t as widely known despite being hugely influential in the contemporary realm of Black literature and the publishing world.

A mix of roles: teacher, publisher, and editor

Morrison took on several roles during her career, most obviously as a writer, but also as a teacher, publisher, and editor. She didn’t view them as separate, but as different facets of working with books, and said that she could never imagine just writing.

“I went once with a friend to the country,” she said in an interview at Bryn Mawr, “and we said we would just stay a week or two and write, and both of us brought back blank pieces of paper. I just looked at the deer, you know; nothing happened.”

She described writing as the work she could not live without but also took “huge joy” in her work as an editor. “My effort is not to erase the conflict between editing and writing but to pay full attention to the editing and to pay full attention to the teaching … I don’t think that I’m the kind of person who can write without that kind of mix.”

Her editing career wasn’t initially born out of passion but out of necessity. In the late 1960s her marriage had broken up; she had children to care for and bills to pay. She needed a job and applied to Random House after seeing an ad on the back of the New York Times Book Review.

She started at their Syracuse office in 1967, becoming the first African American woman to do so (and one of only a handful working in publishing generally).

Her work caught the attention of Robert Gottlieb, then editor-in-chief at Knopf, and Jason Epstein, the editorial director. In 1970 she was promoted to trade editor at the Random House New York office.

“Black people talking to Black people”

At the time, the vast majority of fiction published by commercial publishing houses was by white authors. What Morrison called “the shelf” – the tradition of African American literature in America – was scattered and fragmented, and she believed that the general handling of Black authors was poor, with substandard editing and little to no marketing or publicity.

She was determined to make a change, and wanted her presence as an editor to reassure a Black author that “somebody is going to understand what he’s trying to do, in his terms, not in somebody else’s, but in his.”

She focused on writers who had been excluded from and marginalized within mainstream publishing: “We’ve had the first rush of Black entertainment, where Blacks were writing for whites, and whites were encouraging this kind of self-flagellation. Now we can get down to the craft of writing, where Black people are talking to Black people.”

One of her first successes, The Black Book (1974) ,was an anthology of Black history spanning from the earliest days of enslavement through the twentieth century. It used essays, letters, drawings, songs, and photographs to tell the story of Black people by Black people; Morrison called it “a genuine Black history book – one that simply recollected Black Life as lived.”

Breaking new ground in publishing

Morrison’s list grew extensive. She published and promoted a vast range of work by Black authors, including autobiographies by Muhammad Ali and Angela Davis, as well as fiction and poetry by Lucille Clifton, Toni Cade Bambera, June Jordan and Gayl Jones.

What they all shared, in Morrison’s words, was that same vision of The Black Book: “the kind of information you can find between the lines of history. It sort of falls off the page, or it’s a glance and a reference. It’s right there in the intersection where an institution becomes personal, where the historical becomes people with names.”

Her friend Erroll McDonald, executive editor at Pantheon, said that Morrison “had a sense of mission … the books that she tended to acquire were books of political and social moment … So many of the books were responsive to the times. She saw herself as having not only a literary mission but a social mission as well.”

Morrison herself said that she “wasn’t marching. I didn’t go to anything, I didn’t join anything. But I could make sure that there was a published record of those who did march and did put themselves on the line.”

Morrison’s editing was as daring as her writing, and many of the books that she championed and published were groundbreaking in their focus and subject. Gayl Jones’ 1975 novel Corregidora, for example, was a slave narrative that focused on the history of slavery as it impacted generations of Black southern women and their relationships with each other — as opposed to their relationship to whiteness and white people.

To a certain extent it foreshadowed Morrison’s novel Beloved, and echoed her own preoccupations in her writing. It was also incredibly bold and daring for the time, and after reading it Morrison reportedly said that, “no novel about any Black woman could be the same after this.”

. . . . . . . . .

Toni Morrison in her New York home, 1980s.

Photo by Bernard Gottfryd, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . .

Creating connections between Black authorsMorrison fostered a close relationship with those writers she worked with. The correspondence between her and Lucille Clifton (regarding Clifton’s book Generations) reveals the editing process as a dialogue, a creative endeavor between two brilliant women.

She also encouraged connections between the writers she published and promoted. In May 1972, she wrote to thank Clifton for agreeing to read some stories by Toni Cade Bambera: “I think they are stunning – and hope you will too.” Clifton’s words were later published on the back of Bambera’s collection Gorilla, My Love: “She has captured it all, how we really talk …She must love us very much.”

The importance of the art of editing

Morrison believed wholeheartedly in the importance of editing, and of finding not just a good editor but the right one for the work. In an interview with The Paris Review, she said, “The good [editors] make all the difference. It is like a priest or a psychiatrist; if you get the wrong one, then you are better off alone.”

She also believed that, for Black authors, the process of writing and editing was not just an act of creation, but of resistance and pride. Language itself, for Morrison, could be a challenge to racism and prejudice. Asked how Black writers could “write in a world dominated by and informed by their relationship to a white culture” she responded: “By trying to alter language, simply to free it up, not to repress it and confine it, but to open it up. Tease it. Blast its racist straitjacket.”

This was a view that she brought to all her work, and encouraged in the authors that she published. Angela Davis, after working with Morrison on her autobiography, said, “Toni Morrison persuaded me that I could write it the way I wanted to; it could be the story not only of my life but of the movement in which I had become involved.”

For many people, Morrison’s passion and determination were inspiring “Part of her allure for me,” Erroll McDonald said, “is that she described possibilities, not only for writers of color but publishers of color … When you saw her doing what she was doing, you felt hope in a barren landscape.”

Difficulties within the publishing world

Morrison’s position as an editor was never without its challengess. She faced racism within Random House and the wider publishing industry; there was occasional tension with some of her Black colleagues who disagreed with her decisions.

When she published a collection of poetry by the murdered Black writer Henry Dumas, for example, her edition failed to acknowledge prior publications, including in Black World. The editor of Black World at the time, Carole Parks, wrote to Morrison saying, “It’s not just that you have given people absolutely no inkling that a Black publication gave Dumas his first national exposure. It’s that you have at the same time added to the myth that Black genius would languish unappreciated were it not for some white liberal or far-sighted individual like yourself.”

There were also economic and cultural challenges as publishing continued to transition from art form to business. At the 1981 American Writers Congress, at which she gave the keynote speech, Morrison said, “The life of the writing community is under attack … Editors are now judged by the profitability of what they acquire rather than by what they acquire, or the way they acquire it.”

. . . . . . . . .

10 Fascinating Facts about Toni Morrison

. . . . . . . . .

Toni Morrison’s far-reaching legacyToni Morrison resigned from Random House in 1983. In the preface to her novel Beloved, she wrote, “Leaving was a good idea. The books I had edited were not earning scads of money … My enthusiasm, shared by some, was muted by others, reflecting the indifferent sales figures.”

She had already made an immeasurable contribution to Black writing and to Black publishing, and to the “shelf” of Black literature in America and beyond. As Arielle Grey has stated, “the books she edited and published went out into the world and forever changed it.”

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find more of her writings here and on Literary Ladies Guide.

Further reading

The Cambridge Companion to Toni Morrison, ed. Justine Tally, Cambridge University Press 2008 In Her Own Words: Toni Morrison on Writing, Teaching and Editing , Bryn Mawr Alumnae BulletinToni Morrison: The Art of Fiction, The Paris Review, 1993 Remembering Toni Morrison, a Trailblazing Editor , Vanity Fair, 2019A tribute to Toni Morrison as editor, Virago News, 2021 Toni Morrison as an Editor Changed Book Publishing Forever by Arielle Gray, Medium, 2021The post Toni Morrison as Visionary Editor: “Black People Talking to Black People” appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 4, 2025

Feminist Activists of India Before 1900: A Brief History

This article is reprinted with permission from Unknown Literary Canon. Women were oppressed in patriarchal civilizations the world over. And women the world refused those systems and structures. Women the world over rose up in rebellion against their oppression.

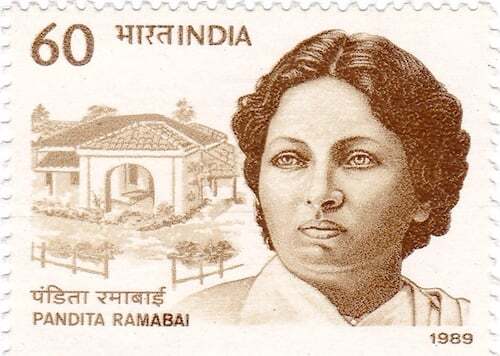

They chaffed against the private domestic sphere before leaving it. They found ways to acquire knowledge that was forbidden to their sex and gender. They defied the odds to take ruling power from men, or ruled alongside and equal to their husbands. (Shown above right, Pandita Ramabai.)

During the colonial/imperialist era, they joined and were welcomed into anti-colonialist movements. Later, they came to together and forged feminist movements to throw off the shackles of domination and oppression that tried to contain and silence them.

In the West, we tend to focus on the feminist movements of the U.S. which inspired the movements in Europe. Most feminist authors we read are American, with a handful of French writers. We miss that the world is large, and women across the world rebelled and struggled against the constraints of patriarchy. Through deepening our collective understanding of the feminisms around the world, creativity can spark like a dialectic, as Audre Lorde said.

As the suffragette movement began in the U.S., feminist writers and activists began their own movement, which grew alongside the anti-colonist and reform movement.

I should like to remind the women present here that no group, no community, no country, has ever got rid of its disability by the generosity of the oppressor. India will not be free until we are strong enough to fore our will on England and the women of India will not attain their full rights by the mere generosity of the men of India. They will have to fight for them and force their will on the menfolk before they can succeed. 1

. . . . . . . . . . .

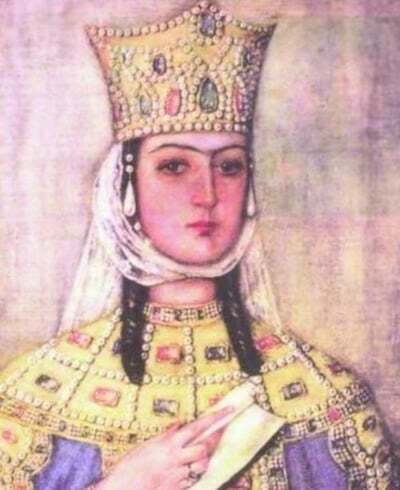

The Queens: Sultan Razia, Nur Jahan,and Rani of Jhansi

Vedic India (1500 to 500 BCE) allowed for some freedoms of gender and for women. However, as that period came to a close, caste took precedence and stratified society narrowly and rigidly. The religion shifted so that righteous actions became tied to caste, caste further tied to family, and the family structure in India was already patriarchal2 — increasing the oppression of women.

The feminist movements of 1800s India looked to both Vedic times and to a few ruling queens, as inspiration for women’s liberation. Sultan Razia, full name Raziyyat-Ud-Dunya Wa Ud-Din, was the first and only female Muslim ruler of the Indian subcontinent. She learned the skill of leadership in ruling in her father’s place when he went to battle.

In 1236, Razia learned that her stepmother planned to execute her. She successfully instigated the public against her stepmother and her son. That her rebellion was supported by the public makes her rule unique. She asked the public to depose her if they were unhappy with her rule. The nobles that supported her expected her to remain a figurehead. Razia had other ideas, taking more power over the four years of her reign. She left the purdah (the private sphere that some women in India traditionally occupied), wore the traditionally male clothing of sultans (Muslim rulers), and made public appearances.

Nur Jahan ruled alongside her husband in the early 1600s3. When her husband became ill, she governed in his place. Scholars believe her political acumen and diplomatic skills rivaled those of more famous rulers. When her husband was captured, she led troops into battle to free him. She signed imperial orders, and coins were issued with her likeness.

Prior to her reign, Nur Jahan was an accomplished architect. She made innovations in the use of marble — which later inspired her stepson, Shah Jahan, who ordered the building of the Taj Mahal.

The Rani of Jhansi (rani means queen) was born Lakshmi Bai. Her complicity in colonization is questionable, but the British viewed her as an enemy. They captured her, but she escaped and became a rebel. Jhansi was a leading figure in the Indian rebellion of 1857, wrote on horseback into battle, and died on the battlefield.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Rassundari Devi

Image: Rassundari Devi Archives, India

“If I am asked to describe my state of mind, I would say it was very much like the sacrificial goat being dragged to the altar, the same hopeless situation, the same agonized screams … People put birds in cages for their own amusement. Well, I was like a caged bird. And I would have to remain in this cage for life. I would never be freed.”

For Rassundari Devi, feminism was a departure and a rebellion without precedent or support. She born to a high caste land-owning family in rural India in 1809 or 1810. Married off when she was only twelve, responsible for the household by the time she was fourteen, she bore twelve children. Women were not typically educated in that time and place, but she tried to learn by sitting outside a classroom while boys were taught the alphabet4.

Her book Amar Jiban (my life) was published in 1868. It’s the story of one woman’s life. An extraordinary book for its time and place, because in writing it, Rassundari Devi told the world that an ordinary woman’s life had worth and merit. Like an early Betty Friedan, she described “the problem that has no name”; that lack of fulfillment and spiritual boredom that came from the repetitive tediousness of domestic labor.

She detailed the struggle to teach herself to read when she was twenty-six. In doing so, Rassundari Devi risked family and societal disapproval and ostracization. She described the process as a form of worship. Her faith was not curtailed to the passive feminine devotion of other women of her era. She read scripture, and she forged her own relationship with the gods.

In doing so, Rassundari Devi broke through the cage that was designed to contain her — broke through the social structures that kept the lives of women domestic and small.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Pandita Ramabai

“My soul thirsted for freedom, for knowledge, for spiritual light; and I am determined that I must seek them at any cost.” 5

Rassundari Devi’s book has survived, but the books of other feminist writers of India have been lost to history. One of those books was authored by Tarabai Shinde. Tarabai was a lower caste (class) woman whose work was explicitly feminist and theoretical: The Comparisons of Men and Women6.

Pandita Ramabai (1858 – 1922) is the best-known of the feminist agitators and rebels of her time. She did not independently chose to leave the private sphere: she was thrust out of it. She helped start local women’s movements, travelled the globe to gain an education and to seek out feminist discourse, authored multiple books, and founding schools for girls.

Before her birth, her father, Anant Shastri Dongre, wanted to teach his wife Sanskrit (the ancient language of Hindu and dharmic scriptures). For this progressive rebellion, he was ostracized and driven away from his home before Pandita’s birth. Desperate for money, the family became nomadic scholars, reciting scriptures for pay. Pandita was taught by her mother, and could recite the 18,000 lines of the Bhagavata Purana from memory7. Pandita lost her family8 to the famines of 1874.

Although Pandita had religious knowledge that would rival that of scholarly man of her time, her family’s experiences made her turn from religion and to the cause of womankind. She had two great advantages: that she learned about social reality and occupied the public sphere because of her nomadic travels, and her deep learning and understanding of Hindu ideology9.

Armed with these weapons of feminist rebellion, she travelled throughout India, agitating and starting women’s movements. She wrote a book arguing against religious practices that hurt women, and for women’s emancipation.

Pandita then traveled to England. Here, she learned English, learned about Christianity. Originally, she wanted to study medicine, but had to drop out because of her deafness. She then travelled to the U.S., where American feminism inspired her to start thinking of setting up schools for girls in India.

To fundraise, she wrote The High Caste Hindu Woman, her most famous work. As the title implies, her views could be narrow because of her high caste and unwillingness to look to women outside of that caste. As well, she advocated from a position of feminine moral superiority — under the presumption that women were morally superior to men10.

How true is the claim of many Western scholars that a civilization should be judged by the conditions of its women! Women are inherently physically weaker than men, and possess innate powers of endurance; men therefore find it very easy to wrest their natural rights and reduce them to a state that suits the men. But, from a moral point of view, physical might is not real strength, nor is it a sign of nobility of character to deprive the weak of their rights . . .

[A]s men gain wisdom and progress further, they begin to disregard women’s lack of strength to honor their good qualities, and elevate them to a high state. Their low opinion of women and of other such matters undergoes a change and gives way to respect. Thus, one can accurately assess a country’s progress from the condition of its women. 11

. . . . . . . . . . .

Sarojini Naidu

Sarojini Naidu rebelled early. She choosing to marry a man from a different state in India than her own (so their native languages and cultures were different), and marrying outside of her caste (class; marriages in India are typically arranged strictly within castes). She became a poet and orator before meeting Gandhi and joining the non-cooperation movement against British colonialism.

Sarojini’s anti-colonialism was part of her feminist advocacy. When arguing with anti-colonialists, she framed women as essential “nation builders” without whom the independence movement could not succeed. Through her advocacy, the women’s liberation movement became part of Indian nationalism.

Sarojini also advocated for women’s suffrage in India, helped start the Women’s Indian Association, and helped women organize strikes and non-violent protests. She became the first Indian female president of Indian National Congress, the first modern nationalist movement of the British empire, and today, India’s major liberal political party.

Her sister-in-law, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, was a more radical feminist than Sarojini. Kamaladevi shocked society by choosing to remarry a playwright after she was widowed. She helped found the All-India Women’s Conference. She’s best remembered for her work in promoting the socio-economic status of women through promoting the learning of Indian handicrafts, handlooms, and theatre.

The Reform Movements of the Early 1800s

Prior to the 1857 – 1858 conquest of South Asia, women and men in India had already begun to organize against casteism, poverty, and rape. Reform movements began around the time of Rassundari Devi’s birth. The oppressions that the reformers wanted to reform included: sati (widow burning) widow remarriage, child marriage, women’s property rights, and polygamy.

The reformers argued to raise the age of consent and marriage to 16 or 1812. Reformer K.C. Sen argued that child marriage was a “corruption of scriptures” and impeded India’s advancement. Reformer Dayananda Saraswati wrote that child marriage caused Indians to be “children of children”. He advocated for girls to be educated prior to marriage. In 1872, there was some success in the Marriage Act, which raised the marriageable age for girls to 14, and for boy to 18.

The reformers also advocated for the education of women. Both liberal and orthodox reformers supported the cause. Some believed that education would make women better wives and mothers, and better allow women to teach their children traditional values. Between 1855-1858, a forerunner of the movement, Vidyasagar, opened forty schools for girls.13

The brahmins (highest caste) organized a 1920 meeting for the compulsory education of women (their demand was denied). Rabindranath Tagore — winner of 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature — revolutionized a school for the revival of Indian arts and culture that his father had started. The school not only allowed women, but emphasized the conditions necessary for bringing out the creative in women.14

Women began to graduate from colleges by the 1880s. Some women went further: going to England to study law and establishing medical schools in India.

At the time, most of the reformers were male of high caste (rigid Hindu class system). There’s the shortcoming of movement spurred by men, with little input from women and the lived experiences of women. This led to a greater issue: that the issues that the reformers wanted to address mostly affected higher caste Hindu women, to the exclusion of women from other religions and the lower castes. It’s the same problem that’s plagued women’s movements across the world, and it’s a problem that still troubles India’s modern-day feminist movements.

There was some lower caste reformers, like Jotirao Phulu (1827 – 1890), who opposed child marriage and advocated for women’s education and remarriage. He started several schools: one for the education of girls, two for the education of the lower castes, and one for the education of the children of widows. In his last book, published 1872, Phulu wrote against the stereotypical sexist language, eg., instead of “all men are created equal”, he wrote “each and every man and woman.”15

Why Is This Important

The early feminist movement in India serves as a powerful example of decolonial feminism, of how pre-colonial history and the movement against colonization spark women’s liberation movements. Because the two movements were historically entwined, the feminism of India doesn’t set up women’s liberation into narrow binaries.

As for the feminist activists and advocates of India, and those of the global majority, India’s early feminism can spark inspiration and creativity. The women and men of these movements showed great resilience in the face of adversity, courageously defied tradition, and spoke up and wrote for what they believed in. Their stories aren’t history to be forgotten; they are guides to show us what is possible.

Contributed by Unknown Literary Canon, a newsletter/blog/project that encourages readers to think about equality for all women through the lens of under-known/overlooked literary fiction, literature by lesbian women, and feminist theory.

Notes1 Jawaharlal Nehru, speech at Allahabad, March 31, 1928. From: Jayawardena, Kumari. Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. (Kali for Women, 1986, republished by Verso Books 2016). p 73.

2 “Righteous actions”, or dharma, are the basis of the dharmic religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, etc.). One is born into one’s caste, caste duties are taught within the family — so if a society is casteist, it is necessarily very oriented around the idea of family.

Jayawardena, Kumari. Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. (Kali for Women, 1986, republished by Verso Books 2016). p 74.

3 Lal, Ruby. Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan. (New York: WW Norton & Company, 2018).

4 Naaz, Hira. The Caged Bird Who Sang: The Life and Writing of Rassundari Devi | #IndianWomenInHistory. Feminism in India. March 23, 2017. https://feminisminindia.com/2017/03/2...

5 Kosambi, Meera. Pandita Ramabai’s American Encounter: The Making of a Modern Hindu Woman. 2003.

6 Jayawardena, Kumari. Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. (Kali for Women, 1986, republished by Verso Books 2016). p 90.

7 Celarent, Barbara. The High Caste Hindu Woman by Pandita Ramabai Sarasvati Pandita Ramabai’s America: Conditions of Life in the United States. American Journal of Sociology 117, no. 1 (2011): 353–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/660901.

8 Ibid, p 90 – 91. Pandita’s parents and sister passed away. She and her brother survived.

9 Ibid, p 91.

10 Celarent, Barbara. The High Caste Hindu Woman by Pandita Ramabai Sarasvati Pandita Ramabai’s America: Conditions of Life in the United States. American Journal of Sociology 117, no. 1 (2011): 353–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/660901.

11 Kosambi, Meera. Pandita Ramabai’s American Encounter: The Making of a Modern Hindu Woman. 2003. p 169.

From: https://www.lehigh.edu/~amsp/2006/09/...

12 Jayawardena, Kumari. Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. (Kali for Women, 1986, republished by Verso Books 2016). p 83.

13 Ibid, p 87.

14 Ibid, p 85.

15 Ibid, p. 84.

The post Feminist Activists of India Before 1900: A Brief History appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 1, 2025

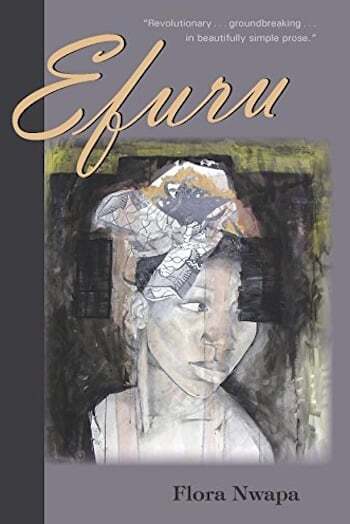

The Works of Flora Nwapa, Mother of Modern African Literature

Chief Florence Nwanzuruahu Nkiru Nwapa (1931 – 1993, familiarly known as Flora Nwapa, was a Nigerian-born author, poet, short story writer, and activist.

She was known as the “Mother of African Literature,” and was the first African woman author whose writing published in England.

Here’s more about her writing, including the influences behind her debut novel, Efuru.

About Flora Nwapa

Florence Nwanzuruahu Nkiru Nwapa was born in Oguta, Nigeria. Born into the Igbo tribe, she was given the otherwise male title of Chief (or ogbuefi). Much of Nwapa’s writing covered what life was like from an Igbo woman’s perspective.

She earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1957. She moved to Scotland and earned a further Diploma in Education at the University of Edinburgh. Her education readied her for a position as Education Officer for Nigeria’s Ministry of Education; Nwapa later taught at the Queen’s School in Enugu until 1962.

Nwapa published her debut novel, Efuru, in 1966. It was the first English-language novel by an African female writer to be published—and widely acclaimed—in Britain. Next came Idu (1970) and Never Again (1975). She also wrote two short story collections, and a poetry volume, Cassava Song and Rice Song (1986).

She founded Tana Press in 1974, and the Florence Nwapa Company in 1977. Nwapa was awarded the title of Chief (or ogbuefi) by her town in 1978. Usually, this honor of achievement was only awarded to Igbo men.

In 1989, Nwapa was appointed a visiting professor of creative writing at the University of Maiduguri in Nigeria. She joined the PEN International Committee in 1991. Nwapa’s last novel, The Lake Goddess, was published after her death (from pneumonia) in 1993.

Flora Nwapa is more than an influential female author: she paved the way for many emerging writers who followed in her footsteps. The Flora Nwapa Society, which provides scholarships and resources, is named in her honor.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Efuru (1966)

Efuru was Flora Nwapa’s debut novel. Its title translates to “daughter of Heaven” in the Igbo language—a culture that wove its way thematically through most of her prose and poetry.

As mentioned earlier, Efuru became the first English-language novel by an African woman to be published in England, partially thanks to its submission to Heinemann Educational Books.

The origin story behind the manuscript might be surprising: without a specific letter to a fellow author, Nwapa might never have decided to publish her debut work at all. She was initially reluctant to publish the novel before sending a copy of the unpublished manuscript to fellow African writer Chinua Achebe. After reading the story, Achebe responded with positive feedback—and one guinea in postage money to submit the manuscript to a publisher in London.

When Heinemann agreed to publish Efuru, a new world opened up for future African writers on an international stage. Efuru draws much of its inspiration from traditional Igbo culture, and served as an important window into culture that was little seen or understood from an international perspective.