Nava Atlas's Blog, page 96

January 2, 2018

Beatrix Potter

Beatrix Potter (July 28, 1866 – December 22, 1943) was a British author and illustrator of beloved children’s books. Her inspiration came from the nature and animals that surrounded her as a child and sprouted an imagination that would delight the world forever.

Beatrix was the daughter of a stuffy, wealthy, conservative couple who cared only about appearance and social status. They cared little for their daughter, and yet, constricted her activities as much as possible so that she had little contact with the world outside their South Kensington mansion and grounds. She wasn’t even allowed to school, nor have any friends her own age. For much of her childhood, her only friend and companion was her brother, Bertram, who was six years younger than she.

An early fascination with the natural world

And so, even though this childhood of isolation and being raised by strict nurses and governesses couldn’t have been easy, Beatrix’s loneliness fueled her fascination with the natural world and animals.

Family holidays in Scotland and the English Lake District allowed Beatrix and her brother plenty of outdoor discovery time, which they did with gusto. As Alison Lurie described it in Don’t Tell the Grownups: Subversive Children’s Literature:

“The children could explore the surrounding gardens and woods and fields and streams, the village lanes and farmyards, without interference … Everything about the countryside fascinated the Potter children. They collected plants, birds’ eggs, and insects; they made pets of mice, rabbits, an owl, and a hedgehog. Both Beatrix and Bertram were naturally gifted artists, and they filled sketchbooks with drawings of whatever they saw.

Beatrix’s watercolors of caterpillars and flowers, made at age eight and nine … show the same charm, delicacy, and accuracy of observation that were to characterize her published books. She also had a gift for fantasy and soon began making up stories set in the local landscape.”

Bertram grew up and unlike his sister, went to school, leaving her ever more isolated. To her parents’ disappointment, she grew in to a plain, shy, and awkward young woman. She sat alone in corners when compelled to go to high society parties, preferring to attend the Natural History Museum to spend time drawing what she saw there — fossils, bugs, and taxidermied animals.

“I cannot rest, I must draw, however poor the result,” she wrote in her journal, “and when I have a bad time come over me, it is a stronger desire than ever.”

At loose ends at age 30

All the self-training and evident skill Beatrix exhibited didn’t help her one she entered adulthood. Her botanical drawings; her discovery of unfamiliar species of fungi; and even a scientific paper she researched and wrote were spurned by the all-male bastion of the botanical community.

And so, Beatrix found herself, at age 30, still unmarried, still under her parents’ stifling rules, plain, dowdy, and with few prospects. “It is not surprising,” writes Lurie, “that during this period of her life she was often ill, suffering from faintness, rheumatic pains, and recurring depression and fatigue.”

To console herself, she continued to do animal drawings, especially of mice and rabbits, and incorporated them into letters she sent to children of her acquaintances.

The birth of Peter Rabbit

The young recipients of her letters were so delighted with her drawings that she began thinking of getting a book published. She returned to a tale she had created in 1893 for the son of her former governess, The Tale of Peter Rabbit. The simple story tells of a mischievous rabbit who becomes the bane of Mr. McGregor and his garden. In 1900, she sent it out to six publishers, all of whom rejected it.

The following year, Beatrix published it herself, ordering 250 copies, which sold out quickly. Finally, in 1902, Frederick Warne & Company published it, and the rest truly publishing history: Peter Rabbit was an instant success, reprinted endlessly, translated into 36 languages, with tens of million copies sold ever since. It’s still one of the best-selling books ever.

A savvy businesswoman

There were a few touches the author insisted on that made her little book rather revolutionary for its time: She insisted that it be a small book, sized perfectly for tiny hands. Many of that era’s books for children were enormous, heavy, ponderous affairs. Next, she wanted to keep the price low, just a shilling, so it would be affordable.

Beatrix was savvy enough to be one of the first authors to merchandise a character. It the year or so after the book was commercially published she patented a Peter Rabbit doll in 1903 and created a Peter Rabbit board game. Following in years to come were toys, dishes, and clothing. Once technology advanced, after the author’s death, there were film and television adaptations as well.

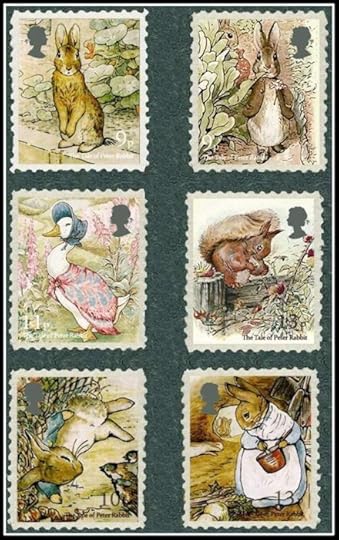

Influenced by fairy tales, fantasy, and religious imagery, Beatrix also illustrated other writers’ work, and as illustrations for Christmas cards. Her illustrations and stories of whimsical animal characters are still a favorite today and can be found in the children’s section of any bookstore or library.

A little bit subversive

The Tale of Peter Rabbit, like the Potter books that came after, were exquisitely illustrated. Yes, the animals wore clothes and were slightly anthopomorphized, but they were filled with delicately rendered backgrounds of the natural world. Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail and Peter lived in the roots of a tree with their mother, who warned them not to go to Mr. McGregor’s garden, because “Your Father had an accident there; he was put in a pie by Mrs. McGregor.” Yikes, how’s that for a dose of reality for young children?

But of course, Peter doesn’t listen. He ventures into the garden and feasts on lettuces, French beans, and radishes. Mr. McGregor makes him a target. Even though Peter’s good siblings get bread and blackberries and milk for supper, he has learned that a little naughtiness (through exploration of the world) can be good for the spirit. That seems to be the underlying message in many of the Beatrix Potter books.

Including Peter Rabbit, Beatrix Potter produced 24 books for young children. All exhibit the lovingly detailed illustrations, slightly naughty characters, and attention to the natural world that made Peter Rabbit such a phenomenon. Tom Kitten, Squirrel Nutkin, Benjamin Bunny, and Little Pig Robinson and many other beloved characters have starred in the little books that have been beloved by children for generations.

An independent (married) woman

Having become famous and wealthy already after her first few books, her editor fell in love with her. Norman Warne, a parter in the Frederick Warne company, proposed to her and she accepted. Her ever-aggravating parents objected, because the gentle Mr. Warne wasn’t “gentleman” enough for them, because he was in “the trades.” She was learning to ignore them.Tragically, Norman Warne died of leukemia before the two were married.

Beatrix was devastated, but the experience helped her to finally stand up to her parents and their irrational whims. She bought her own farm in England’s Lake District with her royalties. She spent an increasing amount at Hill Top farm, and continued to buy land.

In 1913, she married William Heelis, a local lawyer. Her parents once again objected, of course, but she was finally free of them, and moved to the farm full-time.

Beatrix Potter’s books on Amazon

A shift to farming and preservation

The last 30 years of her life were mainly devoted to her farm life. She gardened, raised sheep, and became an avid preservationist. To preserve the beautiful lands of England’s Lake Country, she sought to bring as much of it as possible to the care and ownership of the National Trust. And she left her own property to the National Trust as well. It was transferred after the death of her husband in 1945; Beatrix died in 1943 at the age of 77.

Today, Hill Top is open to visitors who can experience the magic of Beatrix Potter’s farm, gardens, and the surrounding countryside much as this beloved author left them.

Hill Top is one of several

women author’s homes you can visit in England

Major Works

Beatrix Potter wrote and illustrated 24 books for children. Here are just a few of the best known.

The Tale of Peter Rabbit

The Tale of Benjamin Bunny

The Tale of Little Pig Robinson

The Tale of the Flopsy Bunnies

The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin

The Tale of Tom Kitten

Autobiographies and Biographies about Beatrix Potter

Beatrix Potter: A Journal

Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature by Linda Lear

At Home with Beatrix Potter: The Creator of Peter Rabbit by Susan Denyer

Beatrix Potter: Artist, Storyteller and Countrywoman by Judy Taylor

More Information

Wikipedia

The Tales of Peter Rabbit

Beatrix Potter Society

About Beatrix Potter on Peterrabit.com

Beatrix Potter page on Amazon

Articles & News

The Rabbit That Inspired Beatrix Potter

Between the Rows: A Gardening Life

How Beatrix Potter Self-Published Peter Rabbit

Beatrix Potter’s Tales Get a Modern Twist

Lessons Beatrix Potter Taught Me

Your Handwriting Fascinates Me and Your Praise Charms Me

Lit Loves: The Truly Fascinating Beatrix Potter

15 Things You May Not Know About Beatrix Potter

The Bittersweet Announcement of a New Beatrix Potter Book (2016)

Trailer of Peter Rabbit film (2018)

Visit

The Hill Top – Sawrey, Ambleside, UK

The World of Beatrix Potter Attraction – Bowness-on-Windermere, UK

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Beatrix Potter appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

December 31, 2017

Without the Veil Between — Anne Brontë: A Fine and Subtle Spirit by DM Denton

An introduction to and excerpt from Without the Veil Between: Anne Brontë: A Fine and Subtle Spirit — a novel by DM Denton

When I set out, well over two years ago, to write a fiction about Anne Brontë, youngest sister of Charlotte and Emily, I doubted I would find enough material to produce something longer than a novella. Before the first part was finished, I was convinced there was more than enough for a novel.

My objective didn’t change as pages filled and multiplied. I wanted to present Anne as a vital person and writer in her own right, as crucial to the Brontë story and literary legacy as her more famous and — in her brother Branwell’s case — infamous siblings were. As anyone who ventures off the Brontë beaten path might, I soon realized Anne had a very independent, intelligent, inspiring story to explore, take to my heart and soul, and tell.

Without the Veil Between follows Anne through the last seven years of her life. It begins in 1842 while she is still governess for the Robinson family of Thorpe Green, away from Haworth and her family most of the time, with opportunities to travel to York and Scarborough, places she develops deep affection for. Although, as with her siblings, circumstances eventually bring her back home, she is not deterred in her quest for individual purpose and integrity. She stands as firm in her ambitions as Charlotte does and is a powerful conciliator in light of Emily’s resistance to the publication of their poetry and novels.

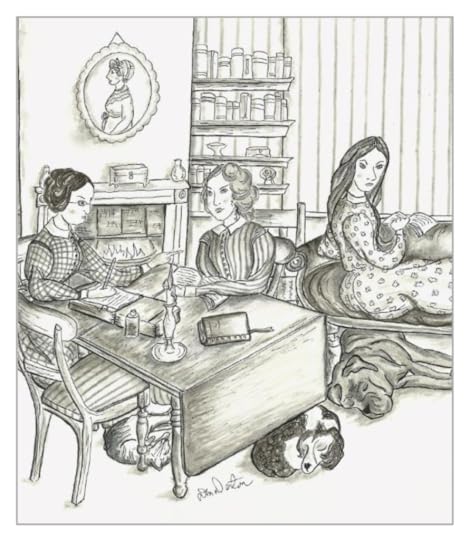

Illustration by DM Denton

from Without the Veil Between

Anne Brontë: A Fine and Subtle Spirit — available on Amazon

Excerpt from Without the Veil Between, Anne Brontë: A Fine and Subtle Spirit Published by All Things That Matter Press Copyright 2017 by DM Denton

Haworth, April 1848

“I have to tell you,” Charlotte interrupted her reading and Anne’s. “I don’t like this one as much as Agnes Grey.”

Anne waited for Emily to differ, but her sister didn’t react as she squatted in front of the hearth to poke at its failing fire.

“Not only has it been such trouble for you to write, when published it will bring you more. It will lay you bare.”

“Then what difference could Smith and Elder make to it?”

“They might—I know you don’t want to hear it—suggest how to smooth it over … tone it down … make it more palatable … more—”

“Entertaining?” Anne wasn’t asking for a reply.

“At least recognize Newby is a shuffling scamp.”

“She does,” Emily admitted listening, “but not without giving him a chance of redemption.”

After months of being upset by Newby’s negligence, Anne could finally smile a little at all the red marks in her personal copy of Agnes Grey. She told herself the best remedy was to move on with a polite yet unyielding expectation of a better result next time. Charlotte continued to argue that Newby had proved himself unreliable and without conscience, and since the success of Jane Eyre had stimulated Smith and Elder’s interest in future writings of its author’s “brothers,” the choice Anne should make was obvious.

Why didn’t Anne agree? The long delay in the release of her and Emily’s novels had been exasperating. Then Newby rushed them into print and, although Anne carefully labored over final corrections, overdue Agnes was born with defects that couldn’t be hidden. The results of Emily’s expectancy weren’t much better. Messrs. Smith and Elder had managed Jane Eyre’s entrance into the world as promised, with little inconvenience to Charlotte, no noticeable pain, and as near-perfect an offspring of her literary efforts as could be expected.

The case for Smith and Elders was persuasively made. Yet Anne knew all along she would persist with Newby to obviously resist Charlotte’s influence. She anticipated her oldest sister harassing her up to and beyond the day she sent The Tenant of Wildfell Hall off to 72 Mortimer Street, London.

The Brontë sisters painted by their brother, Branwell

Emily, Anne, and Charlotte

“I worry about both of you. Em, you haven’t said a word about the response to Wuthering Heights and hardly more about your next one, which doesn’t seem to be progressing at all.”

“I never wanted to publish and will not again.”

“You knew Wuthering was a strange book, but ‘not without evidence of considerable power,’ as one reviewer put it. And another,” Charlotte continued from memory, “‘Impossible to begin and not finish; quite impossible to lay aside afterwards and say nothing about it.’”

“Unlike Agnes Grey.”

“So, Anne, is the coarseness of Tenant your response to the lack of attention gentle Agnes received?”

“It was conceived before I knew Agnes would be received or how.”

“I don’t criticize your effort. But your subject choice is a mistake. You’re too driven by this need to torture yourself, like some kind of penance.”

“I’ve witnessed the degradation human behavior can fall to.”

“Oh, Annie.” Emily was barely audible. “If only you had stayed safely here.”

Anne didn’t need Emily’s prompting to wonder. What if she hadn’t lost her innocence to the torments of Blake Hall and deceptions of Thorpe Green? What if Gondal fantasies and a little of her girlhood at school were the extent of her worldly adventures? What if her conscience had confined itself to home and church responsibilities, visits to the poor and sick with practical and prayerful offerings the extent of her reaching out beyond the protection of family? Why would she write novels if only age, love, and death changed her? Poetry would be enough, a more natural and satisfying means of expression. It suited her pensiveness and piety, could be composed in isolated moments and reflect without analyzing. Poetry was a solitary art; even when read by others, its author could go unnoticed. It was perfect for disappearing into.

Novels wouldn’t leave their authors alone. They needed much attention and were complicated things, requiring names and places, themes and tensions, plotting and resolving and so much in between it was difficult to keep track of where they were going. They were crowded with words and at the mercy of grammar, hard to give up on when months, even years, had been lost to them. Long works of fiction were hard to persevere with, no guarantee anyone would ever read them, or, if they did, with interest and forgiveness.

However, Anne had found a stronger part of herself through their invention. If nothing else, she had achieved independence—cautiously in the first, and, according to Charlotte, irresponsibly in the second—from the Anne Brontë created by circumstance, inhibition, and expectation.

Contributed by DM (Diane) Denton, a native of Western New York, a writer and artist inspired by music, nature, and the contradictions of the human and creative spirit. Her historical fiction A House Near Luccoli, which is set in 17th century Genoa and imagines an intimacy with the charismatic composer Alessandro Stradella, and its sequel To A Strange Somewhere Fled, which takes place in late Restoration England, were published by All Things That Matter Press, as were her Kindle short stories, The Snow White Gift and The Library Next Door. Diane has done the artwork for both her novels’ book covers, and published an illustrated poetry flower journal, A Friendship with Flowers. Visit her on the web at at DM Denton Author & Artist and BardessMDenton.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Without the Veil Between — Anne Brontë: A Fine and Subtle Spirit by DM Denton appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

December 29, 2017

Jane Eyre — 1943 film based on the novel by Charlotte Brontë

How can Charlotte Brontë’s masterwork, be crammed into a time frame of just over an hour and a half? This feat of compression was accomplished by Hollywood for the 1943 film version of Jane Eyre. To clear up any confusion, the film was released at the end of 1943 in Britain, and had its American release of February, 1944.

Nearly a quarter of the film covers young Jane’s torturous experience at the Lowood School, based on the actual place that Charlotte and her sisters attended in Yorkshire. The experience proved fatal for one of the Brontë sisters, Maria, who became gravely ill and died. That was likely the inspiration, if one can call it that, for the character of Helen Burns, one of Jane’s fellow students who becomes a dear friend. Helen is played by a young and lovely Elizabeth Taylor. She’s uncredited in the cast, but her breakthrough role would come soon after as the star of National Velvet (1944).

Peggy Ann Garner as young Jane Eyre

and Elizabeth Taylor as Helen Burns

A gothic mood

The film is dark and moody, even gloomy, with black clouds always swirling, in keeping with the gothic mood of the story. Even interiors are dark and dreary. There are the attendant bursts of overly dramatic background music typical of that era’s films. The casting is great, with Joan Fontaine as Jane Eyre — a character likely very much based on Charlotte Brontë herself — and Orson Welles as the peculiar, brooding, yet ultimately redeemable Mr. Rochester.

The best part of the film is seeing actual passages from the book appear on the screen, such as this one:

“What sort of man was this master of Thornfield — so proud, sardonic, and harsh? Instinctively I felt that his malignant mood had its source in some cruel cross of fate. I was to learn that this was indeed true, and that beneath the harsh mask he assumed lay a tortured soul, fine, gentle, and kindly.”

Yes, gentle and kindly — this she writes before finding out that the man she has fallen in love with has stashed his mentally ill wife in the attic — Bertha Antoinetta Mason is the proverbial madwoman in the attic.

Rushed pacing

There’s Bertha’s first attempt to set the castle ablaze, Edward Rochester’s declaration of love to Jane after spurning a glamorous, gold-digger, and his confession the alter that he already has a wife, after a last-minute “I object!” His plea to Jane to live with him as his wife, her refusal, her departure.

The rest of the movie speeds through the original plot, all but eliminating Jane’s quest to become her own person in the world before considering a return to Thornfield. After all, there are but twenty minutes or so left of the film. For those who don’t know the story, we’ll stop short of giving away spoilers.

Not the best version, but you can watch for free

There are those who love this film, as evidenced by the comments on YouTube, where you can watch this film version of Jane Eyre in its entirety for free. It’s not terrible, but as an adaptation, it doesn’t live up to 1940’s Rebecca nor 1939’s Wuthering Heights, in this genre of moody gothics. It also didn’t receive the kind of accolades or award nominations of these related films.

There are later film adaptations of Jane Eyre that are an improvement over this one , but better yet, read the book or listen to an unabridged version on audio.

More about Jane Eyre — 1943 film

Wikipedia

Jane Eyre on IMDB

Review on Classic Film Freak

Jane Eyre Spotlights Orson Welles’ Perfect Romantic Antihero

The post Jane Eyre — 1943 film based on the novel by Charlotte Brontë appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

December 27, 2017

Rebecca — 1940 Movie Based on the Novel by Daphne du Maurier

The 1940 movie version of Rebecca, based on Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 novel of the same name, was a psychological thriller with nod to the gothic tradition. The black-and-white film, which captured the moody, mysterious feel of the book, was the first American film by director Alfred Hitchcock. Joan Fontaine starred in the role of the naïve young woman who marries a brooding widower Maxim de Winter, portrayed by Laurence Olivier.

Rebecca, the departed first wife of de Winter, is never seen in the film, but casts a powerful shadow over the inhabitants of Manderlay castle. The suspense builds until we learn just why that is. The film was nominated for 11 Academy Awards, and won two, for Best Picture and for Cinematography.

Though it didn’t make an enormous amount of money at the box office, it was exceedingly well-received by critics. Hundreds of reviewers named it the best film of 1940. Even among more contemporary critics, Rebecca has a 100% score on Rotten Tomatoes. Here’s a 1940 review from The Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

From the March, 1940 review of the film version of Rebecca by Herb Cohn in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle: The vengeful ghost of the first Mrs. de Winter has found an ally in Alfred Hitchcock. Rebecca never emulates the ghosts of Marley or Hamlet’s father by becoming visible — she warps the lives of her widowed husband and his innocent young bride with a devilish delight that is as compelling as make-believe can be.

She is an unseen demon who owes her unholy power more to a wizard of the camera than to the vivid imagination of a talented author. The ghost of Rebecca might well be a revelation to Daphne du Maurier herself. She will stand as one of the haunting creations of Hitchcock. For Rebecca is unquestionably the most remarkable film that the British directer has turn out thus far.

But if the conception of the ghost of Manderley Castle is to the credit of Miss du Maurier’s 1938 novel, and the dramatic evaluation of her influence is to the credit of Hitchcock, the expression of that invisible phantom is the triumph of the superb cast that David O. Selznick has assembled. The film tells the grim and yet tender story of Maxim de Winter and the childish bride he brought from Monte Carlo to the sea-battered coast of Cornwall. There, tragedy had blighted his life as the master of Manderley.

Based on the book: Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

For it is through Maxim and the nameless girl he made the second Mrs. de Winter, through Ben, the half-witted handyman, and Mrs. Danvers, the sinister housekeeper who cherished Rebecca in death as in life, that the eerie tone of the du Maurier story is set. Through them Rebecca exerts her mastery of the house.

Joan Fontaine brings a stunning modulation of emotions to the second Mrs. de Winter, a naive but sincere young woman who comes to her husband’s Cornish estate to find that her predecessor, drowned a year before when her skiff was lost off-shore. She is still the castle’s mistress by remote control, every object in its somber halls bearing memories of her stewardship, every servant in the household cleaving to the routine she established.

Rebecca – 1940 movie DVD on Amazon

The shadow of the departed Rebecca comes between her and her husband the moment they lea their Continental honeymoon behind then and drive up the winding road to the steps of Manderley.

Laurence Olivier, fortified by his playing of Heathcliff in 1939’s Wuthering Heights, excels in the role of Maxim de Winter, the stoic man of the world who is struggling under some secret burden. Olivier plays him with determined restraint, preserving the Hitchcock air of mystery throughout, yet making him a pleasant figure with a gracious charm.

Judith Anderson portrays Mrs. Danvers, the mystifying housekeeper who constantly taunts her new mistress with abnormally fond memories of the beauty, the breeding, and the brilliance of Rebecca de Winter.

Rebecca is an example of the quality that comes from carefully polished production, with script writers, director, and actors working in unity. It is an overwhelming human drama, psychologically complex, marvelously exhausting, and cinematically unorthodox. Above all, it’s a brilliant display of storytelling, one that does justice to Daphne du Maurier’s original vision.

More about Rebecca — 1940 film

Wikipedia

Rebecca on Filmsite.org

Rebecca full movie on YouTube

Rebecca on Rotten Tomatoes

An Analysis of Alfred Hitchcock’s Thriller, Rebecca

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Rebecca — 1940 Movie Based on the Novel by Daphne du Maurier appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

December 25, 2017

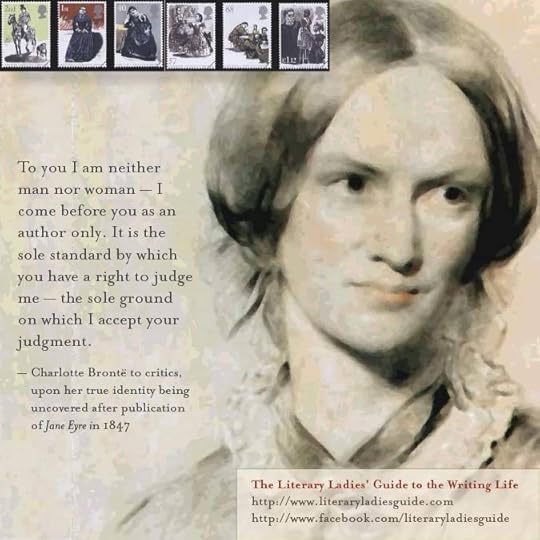

Quotes from Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Jane Eyre is considered a classic of English literature and the masterwork of Charlotte Brontë. Though it was her first published novel, it was the second that she wrote — The Professor was her first, though it was published only after the author’s death. Jane Eyre was published in October, 1847 under Charlotte’s pen name Currer Bell. Though it was met with some controversy, it was also an instant success.

Jane’s love for her employer, the mysterious Mr. Rochester is concurrent with her desire to be an independent woman with dominion over her own strong views and identity. This novel was unusual for its time, with the exploration of the inner world of the narrator at its center. Here are selected quotes from Jane Eyre that speak to the author’s sensibilities and strong opinions.

“I am no bird; and no net ensnares me: I am a free human being with an independent will.”

“I care for myself. The more solitary, the more friendless, the more unsustained I am, the more I will respect myself.”

“I can live alone, if self-respect, and circumstances require me so to do. I need not sell my soul to buy bliss. I have an inward treasure born with me, which can keep me alive if all extraneous delights should be withheld, or offered only at a price I cannot afford to give.”

“Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! — I have as much soul as you — and full as much heart! And if God had gifted me with some beauty and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you.”

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë on Amazon

“I have little left in myself — I must have you. The world may laugh — may call me absurd, selfish — but it does not signify. My very soul demands you: it will be satisfied, or it will take deadly vengeance on its frame.”

“Friends always forget those whom fortune forsakes.”

“Oh! That gentleness! how far more potent is it than force!”

“If all the world hated you and believed you wicked, while your own conscience approved of you and absolved you from guilt, you would not be without friends.”

“I do not think, sir, you have any right to command me, merely because you are older than I, or because you have seen more of the world than I have; your claim to superiority depends on the use you have made of your time and experience.”

“I ask you to pass through life at my side—to be my second self, and best earthly companion.”

“Women are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts, as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, to absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow-minded in their more privileged fellow-creatures to say that they ought to confine themselves to making puddings and knitting stockings, to playing on the piano and embroidering bags. It is thoughtless to condemn them, or laugh at them, if they seek to do more or learn more than custom has pronounced necessary for their sex.”

See also: Charlotte Brontë’s Quotes on the Writing Life

“I have for the first time found what I can truly love — I have found you. You are my sympathy–my better self–my good angel — I am bound to you with a strong attachment. I think you good, gifted, lovely: a fervent, a solemn passion is conceived in my heart; it leans to you, draws you to my centre and spring of life, wrap my existence about you–and, kindling in pure, powerful flame, fuses you and me in one.”

“Some of the best people that ever lived have been as destitute as I am; and if you are a Christian, you ought not to consider poverty a crime.”

“I remembered that the real world was wide, and that a varied field of hopes and fears, of sensations and excitements, awaited those who had the courage to go forth into its expanse, to seek real knowledge of life amidst it’s perils.”

“There is no happiness like that of being loved by your fellow creatures, and feeling that your presence is an addition to their comfort.”

“What necessity is there to dwell on the Past, when the Present is so much surer — the Future so much brighter?”

“It is not violence that best overcomes hate — nor vengeance that most certainly heals injury.”

“It is always the way of events in this life … no sooner have you got settled in a pleasant resting place, than a voice calls out to you to rise and move on, for the hour of repose is expired.”

“Reader, I married him.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

December 20, 2017

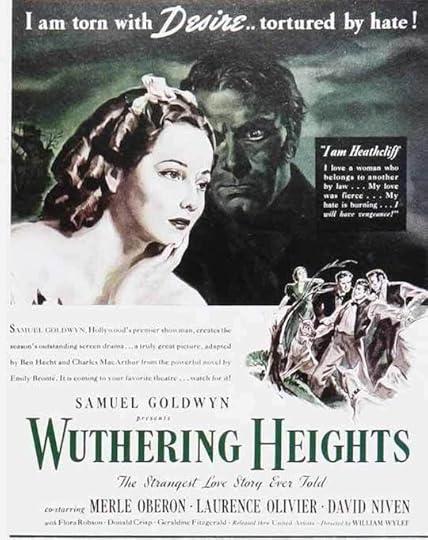

1939 Movie Adaptation of Wuthering Heights

The 1939 movie adaptation of Wuthering Heights, based on the novel by Emily Brontë, is considered an American film classic. Produced by Samuel Goldwyn and directed by William Wyler, the screenplay took some liberties with the original stories to streamline it into a film whose run time is less than two hours. It covers barely half of the novel’s 34 chapters, cutting out the second generation of characters.

Wuthering Heights was nominated for eight Academy Awards, but faces stiff competition that year from Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz. Despite the liberties taken with the story, the film retained the dark, brooding mood of the book, and was generally praised by critics.

Following is a review from the year the film came out:

From the review by Herbert Cohn in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April, 1939: Samuel Goldwyn’s screen version of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, her only novel, has only part of the book’s unhappiness because it relates only part of the story. It has lopped off chunks of Brontë melancholia and occasionally sweetened portions that remained. But Wuthering Heights is capable of overpowering drama; its bitterness becomes even more intense when acted out. It needs such tempering if it is not to out-Brontë Brontë.

Forgiveness for Hollywood’s tampering

Here is one time that the purists — this department included — cannot complain about Hollywood’s tampering. For the qualities that made the Brontë novel a literary classic — and its tragedy and startling pessimism are among them— are magnificently transferred to the screen. They are not transferred whole, to be sure, sometimes they are represented symbolically, sometimes they are merely in the tone of Cathy’s spitefulness and Heathcliff’s contemptuousness. But they chase way even the tiniest doubt that Mr. Goldwyn has made a classic motion picture from a classic novel.

His Wuthering Heights is magnificent tragic drama. Emily Brontë demands nothing more, though. It deserves a place among the screen’s great, regardless of the present-day popularity of the unhappy authoress of the Yorkshire heaths.

Merle Oberon and Laurence Olivier as Cathy and Heathcliff

Merle Oberon has surpassed herself as the willful and emotionally sensitive Cathy. It has been a role coveted by many great actresses but she has made it one that will be always hers. Laurence Olivier has never had a part to equal that of Heathcliff, the gypsy stableboy whose moods fun from extreme dejection to supreme happiness and whose expressions switch suddenly from painful self-punishment to carefree, almost childish, playfulness. Olivier has made of him an unforgettable figure.

A softening of characters

Part of the change in what Wuthering Heights is in the softening of a few of its characters. Edgar, Cathy’s wealthy suitor, gives David Niven a chance to be the only sympathetic character, a quality he didn’t possess in the book. And Healthcliff’s servant, Jospeh (Leo G. Carroll), an intolerant religious fanatic becomes an unimportant handyman. He, like other secondary figures in the novel, takes on a shallowness in the picture that is part of its general simplification.

Simplification is what Wuthering Heights needed to make it compact drama. Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur have done a smooth job of remodeling, tossing out the second-generation angle of the Cathy and Heathcliff romance, modernizing the dialogue without sacrificing its straightforwardness, imagining a half dozen colorful romantic scenes on the crags and even supplying a modernized spiritual ending that for once, is not off pitch.

Told in flashback

What is left of Wuthering Heights, then, is a flashback story — set on the eerie Yorkshire moors — of two lovers and their spite work. Heathcliff, the gypsy boy who is despised by Cathy’s brother Robert, is the girl’s very soul. But he is a strange, moody fellow who can never make her “the finest lady in all the county.” So she ignores her love for him — and his for her — and marries the wealthy Edgar.

Heathcliff swears vengeance and disappears for several years. When he comes back he is wealthy enough to take his revenge immediately on Cathy’s bankrupt brother. Then he turn to collect his debt from Edgar by winning his sister, Isabella (Geraldine Fitzgerald) as a wife that he intends to make miserable.

Not a pretty story, but one well told

Not a pretty story, but one that is strange, pack with fascination, and with hidden power waiting for clever actors to develop. The cast — with Fora Robson, Donald Crisp, Miss Fitzgerald, and Hugh Williams — knows hbow. And director William Wyler has set a becomingly grim stage for their delicate portrayals of unlovely characters.

Their combined work has resulted in a splendid screen drama, one that is beautifully written and played and sumptuously mounted. Wuthering Heights is a film that should not and must not be missed.

See other screen versions of Wuthering Heights on Amazon

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 1939 Movie Adaptation of Wuthering Heights appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

December 18, 2017

Classic and Contemporary Tips for Developing Characters in Fiction

The heart of any compelling story or novel is its characters. Without memorable characters, a story will fall flat and the reader won’t care. Characters don’t need to be good or even sympathetic, but they do need to be driven by their beliefs and motivations to create a strong narrative arc, and to create and resolve conflict.

If you don’t know where to begin, you may appreciate these tips for developing characters in fiction (from classic and contemporary writers) First, let’s see how three classic authors approached the question of developing characters:

Madeleine L’Engle suggested keeping one’s eyes and ears open: “I don’t suppose it’s possible for a writer to create a wholly imaginary character. Whether we are aware of it or not, we are drawing from every human being we have ever known, have passed casually in the street, sat next to on the subway, stood behind in the check-out line at the supermarket. Perhaps one might say that we draw constantly from our subconscious minds, and undoubtedly this is true, but more important than that is the super-conscious level which comes to our aid in writing — or painting — or composing — or teaching, or listening to a friend.” (from A Circle of Quiet, 1972)

Louisa May Alcott made it sound simple — she observed the characters as they developed, almost letting them be in charge of her, rather than the other way around: “While a story is under way I lie in it, see the people, more plainly than the real ones, round me, hear them talk, & am much interested, surprised, or provoked at their actions,” she wrote in an 1887 letter, “for I seem to have no power to rule them, & can simply record their experiences & performances.” If only it were that easy for the rest of us!

L.M. Montgomery carried a notebook for jotting down her ideas for for plots, incidents, and characters. They were at her disposal when she needed a jumping off point. “Two years ago in the spring of 1905 I was looking over this notebook in search of some suitable idea for a short serial I wanted to write for a certain Sunday School paper and I found a faded entry, written ten years before:

“Elderly couple apply to orphan asylum for a boy. By mistake a girl is sent them.” I thought this would do. I began to block out chapters, devise incidents and “brood up” my heroine. Somehow or other she seemed very real to me and I thought it rather a shame to waste her on an ephemeral little serial. Then the thought came, “Write a book about her. You have the central idea and character. All you have to do is spread it out over enough chapters to amount to a book.” The result of this was Anne of Green Gables. (from her Journals, 1907)

It’s always fascinating to see that accomplished authors of the past dealt with the same kinds of writerly issues we all face. But now, let’s get to more nitty-gritty. Here are a few contemporary views on how to create memorable characters, with tips that are a lot more specific:

Learn the basics with “Character 101”

If you’re a beginner and don’t know where to begin, Vicki Essex breaks it down to the basics in Building Complex, Interesting, Memorable Characters. Just one of her tips is to give your character a code — more of an ethical code rather than a secret code. “This is your character’s iron-clad rule that they will not, under any circumstances, break,” she advises. And there’s lots more good advice on where this came from, when it comes to character development.

Name your characters

T.J. Ellison, author of best selling thrillers, has a simple tip that can go a long way — name your characters. “As I begin writing a new manuscript, I make a cast list. All the main characters are there, as well as all the secondary characters.” See more about this in her post on How to Build a Character.

Nail your characters’ personality types

Here’s a “novel” approach: use the Myers Briggs Type Indicator to get deeper into the personality of your characters. That’s what Kristen Kieffer describes in My Favorite Method for Building Characters’ Personalities. Using this technique, she doesn’t merely write from the character’s perspective, she becomes the character. They come to life in a way she was never able to accomplish before nailing down their personality type.

Dig deep into each character’s motivation

Ellen Brock believes that characters lack depth when a writer focuses too much on personality. She had some great tips on delving deep into a character’s motivation — what they want, their goals, and their emotional state. Learn more in Creating Deep Realistic Characters.

13 more great tips

Justine Musk offers a treasure trove of inspiration in 13 Ways to Create Compelling Characters, from making the character exceptional at something to giving them “blind spots” that stand in the way of their own self-perception.

See more from our writing advice category — timeless tips from past and present!

Photos: Bigstock

The post Classic and Contemporary Tips for Developing Characters in Fiction appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

December 17, 2017

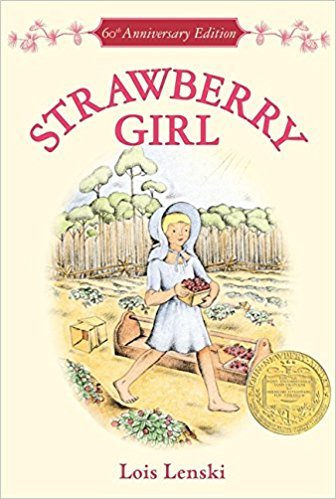

Strawberry Girl by Lois Lenski (1945)

Lois Lenski (1893 – 1974) was an incredibly prolific author and illustrator of children’s books, many featuring regional themes. Children were often shown in terms of the work they did to help their families survive. The series that put her on the map was the Regional Stories, which began with Bayou Suzette. Strawberry Girl (1945) was the second in the series, and the one that Lenski is perhaps best remembered for. She won the 1946 Newbery Medal for this book.

From the 1945 J.B. Lippincott edition of Strawberry Girl written and illustrated by Lois Lenski: Birdie Boyer belonged to a large “strawberry family” in Florida, who lived on a flat woods farm in the lake section of the state. They raised strawberries for a living.

Through all the hazards of the uncertain crop — battling against dry weather and grass-fires, the going hogs and cattle of their neighbors — Birdie dreamed of an education that would include playing the organ. In the end she won not only the title of “strawberry girl,” but book learning as well.

Strawberry Girl by Lois Lenski —

60th anniversary edition on Amazon

This is a story full of enterprise and fun and the excitement of real life in this interesting part of America. Lois Lenski has used her gift for catching the flavor and drama of life in a remote corner of America.

It is the second of a series of regional stories through which she promises to introduce other fascinating and little-known backgrounds to young readers. This story will take a place beside her popular Louisiana story Bayou Suzette in the affection of readers.

The more than eighty illustrations are distinguished for their action and fascinating detail. They add greatly to this true picture of Florida life at a time when old Florida ways were changing to new.

Illustration by Lois Lenski from the 1945 edition of Strawberry Girl

More about Strawberry Girl by Lois Lenski

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Review on Plugged In

Review on The Newbery Project

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Strawberry Girl by Lois Lenski (1945) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

December 16, 2017

Lois Lenski

Lois Lenski (October 14, 1893 – September 11, 1974), American children’s book author and illustrator born in Springfield, Ohio, was best known for realistic depictions of childhood in regional settings around the U.S. As a young girl, she showed an early aptitude for art, and it was in the visual and applied arts in which she pursued an education. After graduating from Ohio State University in 1915, she studied at the Art Students League in New York City on scholarship, followed by the Westminster School of Art in London. While abroad, she spent several months in Italy.

Upon returning to the U.S., Lenski married Arthur Covey, who had been one of her instructors during a brief sojourn at a school for industrial arts. A muralist, he was a widower with two children when the couple married in 1921. The couple settled in Connecticut had one son of their own. Covey was considerably older than Lenski, and felt she should set aside her creative pursuits to care for the home and family. That made her even more determined to pursue her career, and with her own earnings, hired household help in order to have more time for her work.

High school graduation photo, circa 1911

The start of a prolific career

Lenski’s first book, Skipping Village, was published in 1927. A Little Girl of 1900 followed, and launching her career as an author-illustrator of children’s books. Phebe Fairchild, Her Book was the first of numerous books depicting American childhood. One thing was clear — the fictional boys and girls represented in her books reflected the reality of their times, in which children had to work to help their families survive.

Newbery Medal and regional stories

In 1946, Lenski won the 1946 Newbery Medal for Strawberry Girl brought even more attention to her genre of regional books for and about children. Strawberry girl was preceded by Bayou Suzette, and joined by many others, including Blue Ridge Billy, Boom Town Boy, Coal Camp Girl. Through these books, all of which she illustrated, she took readers on journeys all over the United States to give snapshots of how children lived.

Lois Lenski did first-hand research, traveling to all of the areas in which she set her stories. She spent time with families, listens to their stories, and noted their patterns of speech. She did sketches with her drawing pencil, later refining them into the finished illustrations in her books.

Strawberry Girl is perhaps the best known

of Lenski’s dozens of books

Reconsideration of Lois Lenski’s work

In their time, Lenski’s books were considered very innovative, though some critics deemed them a bit grim. Rather than sentimentalizing childhood, they depicted members of working classes and agricultural communities. Librarians and teachers appreciated their gritty realism. The storytelling in these books opened a view into how others lived, creating a means of social awareness for young readers.

Lenski is no longer widely read. In reconsidering her work, modern critics have found her books somewhat didactic and simplistic. Her depictions of people of color have found fault, as well. Still, her work was so unique in its time that it deserves its place in children’s literature. Her prolific output and her bold, appealing artwork showcase her dedication to her craft.

Lenski’s graphic illustration style, whether for her own

or others’ books, was highly recognizable

Later life and legacy

In 1951, Lois Lenski and her husband built a house in Tarpon Springs, Florida, where they spent half of each year. In the 1940s, she had health issues, leading her physician recommended avoiding the harsh New England winters. By the late 1950s, she began receiving honorary doctorates from a number of universities. In 1967, she founded the Lois Lenski Covey Foundation, whose stated mission is “to advance literacy and foster a love of reading among underserved and at-risk children and youth.”

In addition to the dozens of her own books for children that she wrote and illustrated, she also illustrated nearly 60 books by other authors. Her last book for children, Debbie and her Pets, was published in 1971. Her last book, published in 1972, was her autobiography, Journey into Childhood. Lois Lenski died in 1974 at her home in Tarpon Springs, FL at the age of nearly 81.

More about Lois Lenski

Major Works

Regional Stories

Corn-Farm Boy

Prairie School

Bayou Suzette

Strawberry Girl

Houseboat Girl

San Francisco Boy

Texas Tomboy

Cotton in my Sack

Boom Town Boy

Coal Camp Girl

To be a Logger

Mama Hattie’s Girl

Prairie School

Blue Ridge Billy

Judy’s Journey

Shoo-Fly Girl

Deer Valley Girl

Roundabout America Books

We Live in the North

Berries in the Scoop

We Live in the South

Little Sioux Girl

We Live by the River

We Live in the City

We Live in the Country

High-Rise Secret

Other books

Indian Captive: The Story of Mary Jamison

Puritan Adventure

Blueberry Corners

Ocean-Born Mary

Surprise for Mother

Bound Girl of Cobble Hill

Biography and Autobiography

Lois Lenski: Storycatcher by Dr. Bobbie Malone (2106)

Journey Into Childhood by Lois Lenski (1972)

More information

Wikipedia

Reader Discussion of Lenski’s books on Goodreads

Books written and illustrated by Lois Lenski

The Lois Lenski Covey Foundation

Lois Lenski page on Amazon

Meet Lois Lenski (video)

Archives

Lois Lenski left a vast trove of papers behind, and there are several repositories. Here are three of the largest:

Lois Lenski Papers, UNC Greensboro

Lois Lenski Papers, Florida State University

Lois Lenski Children and Young Adult Literature Collection at Buffalo State

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Lois Lenski appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

December 14, 2017

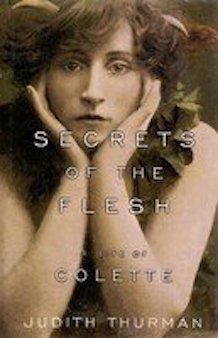

Secrets of the Flesh: A Life of Colette by Judith Thurman

Judith Thurman, author of the National Book Award-winning biography of Isak Dinesen produced thus far the most definitive English language biography of Colette. Given the French author’s stature as a literary figure and feminist icon, along with her colorful life, it is remarkable how few biographies exist about her. Secrets of the Flesh, weighing in at over 600 pages, gives readers a thorough view of Colette’s long and colorful life.

From the 1999 Alfred A. Knopf edition of Secrets of the Flesh: A Life of Colette by Judith Thurman: In 1900, a provincial beauty known as the child bride of a famous Parisian rake captivated the Belle Epoque by writing a story that invented the modern teenage girl. It was the first in a series of wildly popular, critically acclaimed novels (known as the Claudine stories) that, combined with a flamboyant career on the stage, made this former country girl the first superstar of the century.

But for all her celebrity as one of France’s greatest and most notorious novelists and personalities, Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette was a profoundly reticent and self-suspicious creature who fiercely resists being known. Judith Thurman gives us an incomparably nuanced and revealing portrait of the elusive woman, the prodigious writer, and the revered but misunderstood idol.

Having spent her village childhood in the shadow of a queenly, possessive mother who taught her the value of resilience, Colette would go on to embody the image of the modern woman. At twenty, she married the canny but unscrupulous Willy, who not only took credit — and the royalties — for her best-selling Claudine novels, but also kept her enthralled in more primal ways. In 1908, she divorced her Pygmalion and pursued the most public of her many affairs with women.

At forty, she gave birth to her only and much-neglected child. Her second marriage, to her daughter’s father — a brilliant predatory, patrician journalist and politician — faltered, then failed.

Secrets of the Flesh by Judith Thurman on Amazon

At forty-seven, she seduced her adolescent stepson. At menopause, she rediscovered her mother. At fifty-two, she embarked on a torrid adventure with a much younger man that bloomed — against all expectations — into the serene and enduring mutual devotion she had yearned for but never knew. The third husband — Maurice Goudeket, also became the source of her worst anguish when he was arrested by the Gestapo during the occupation.

As Colette redefined the conventions of loving and aging, she continued to write with Olympian vitality. Her principal subject was the bonds of love; her one try faith was the consoling power of sensual pleasure.

She opened a beauty institute and did makeovers in a lab coat; she produced a body of incisive journalism; she wrote enchanting masterpieces like Gigi and Sido, and provocative works like Chéri, Break of Day, The Ripening Seed, and The Pure and the Impure.

Her wartime work remains the most controversial part of her legacy, and Thurman addresses the troubling questions it raises with a typically lucid and tenacious intelligence.

Drawing upon a rich mine of new documents, candid interviews, and unpublished letters, Secrets of the Flesh evokes Colette in the fullness of her contradictions. A work of penetrating psychological insight, historical perspective, and literary discernment, it is sure to reanimate our appreciation of its iconic subject.

Learn more about Colette

More about Secrets of the Flesh: A Life of Colette by Judith Thurman

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Secrets of the Flesh on Audiobook

Review in The New York Times

Review on Salon

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Secrets of the Flesh: A Life of Colette by Judith Thurman appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.