Nava Atlas's Blog, page 95

January 18, 2018

Reading Aloud to Children: Creating Lifelong Book Lovers

Establishing a read-aloud ritual can be one of the most gratifying ways to enjoy well-spent family time. If raising children leaves you with little energy or patience for personal reading, take comfort in knowing that reading aloud to kids can be as nourishing for the reader as it is for the listener(s). And literacy experts agree that reading aloud to children from an early age helps assure their becoming avid readers later on.

Don’t limit reading aloud to preschoolers—school-age children and sometimes even teens love being read to. Add whatever embellishments you’d like—a warm beverage, a specific setting, lots of cuddling—to ensure a prominent place in your child’s memory for this time-honored ritual.

Jim Trelease is the author of The Read Aloud Handbook, which came out in and is revised and updated every few years. He writes, ““The single most important activity for building the knowledge required for eventual success in reading is reading aloud to children.” In his “30 Do’s to Remember When Reading Aloud” he offers great tips and benefits. Here are the first five:

1 Begin reading to children as soon as possible. The younger you start them, the easier and better it is.

2 With infants through toddlers, it’s important to include books that contain repetitions; as they mature, add predictable and rhyming books.

3 During repeat readings of a predictable book, occasionally stop at a key phrase and allow the child to provide the words.

4 Read as often as you and the child (or students) have time for.

5 Set aside at least one traditional time each day for a story.

Read the rest here in this online brochure.

Here are a few more tips to inspire you to read aloud to your children:

Revisit heroines you loved as a child

Reading these books to your own children is a thrill, especially when you can introduce them to heroines you loved as a child. Remember Jo March and the rest of the Little Women, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm? Revel in their tales of spunk and courage while sharing them with your daughters. There’s no reason not to read them out on boys, too. Few children can resist Pippi Longstocking, Pollyanna, or Anne of Green Gables.

It’s never too late for a classic

Discovering classics that somehow passed you by is a delight, too. If you somehow missed Peter Pan, Bambi, Alice in Wonderland, The Secret Garden, and others as you grew up, share them with your children. Not merely great children’s books, but great books altogether, the rich language of classics, experienced aloud, stimulates your imagination as much as your children’s.

Fairy and folk tales, myths, and fables

These make wondrous read-alouds, and their universal themes can be experienced on many levels. Start with the folk stories from your own cultural background, then move on to those of cultures that interest your family.

The Heroine’s Bookshelf by Erin Blakemore on Amazon

Resources

The Heroine’s Bookshelf: Life Lessons, from Jane Austen to Laura Ingalls Wilder by Erin Blakemore pairs literature’s most beloved heroines (including Jo March, Francie Nolan, and Scout Finch) with their creators to impart wisdom for life’s challenges. These intertwined pairs will inspire you to re-read your old favorites with your daughters.

The Read-Aloud Handbook by Jim Trelease is a definitive volume on this subject. Updated every few years, it makes an inspiring case for reading aloud, and supplies a thorough list of the best read-aloud books for several age groups.

The New York Times’ Parent’s Guide to the Best Books for Children by Eden Ross Lipson is a guide to children’s literature from picture books through young adult novels, with special recommendations for books that make good read-alouds.

Once Upon a Heroine: 450 Books for Girls to Love by Alison Cooper-Mullin and Jennifer Marmaduke Coye explores classic and contemporary literature for girls.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Reading Aloud to Children: Creating Lifelong Book Lovers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 17, 2018

The Awakening by Kate Chopin: an analysis

Following is an analysis by Sarah Wyman of The Awakening by Kate Chopin, an 1899 novella telling the story of a young mother who undergoes a dramatic period of change as she “awakens” to the restrictions of her traditional societal role and to her full potential as a woman. Many times, we find Edna Pontellier awake in situations that signify more metaphorical awakenings to new knowledge and sensual experience.

Consequently, Chopin’s work came under immediate attack when published and was banned from bookstores and libraries. The author died virtually forgotten, yet The Awakening has been rediscovered and holds a secure and prominent position as a watershed text in U.S. literature and feminist studies.

Edna’s first depicted episode of awakening, literally, comes at the expense of a good night’s sleep, and leaves her crying and frustrated but unable to articulate the source of her emotional response to a callous, if affectionate, husband. From this powerless starting point, Edna will experience a series of discoveries about her world and her self that inspire her to experiment and explore, but leave her ultimately defeated. Vacationing at Grand Isle on the Gulf of Mexico, she undergoes life-changing transformations.

The restrictions of marriage and motherhood

Marriage and motherhood constitute unsupportable restrictions for Edna. Léonce, her well-respected, businessman husband, clearly objectifies Edna when she returns from a sunny beach day: “You are burnt beyond recognition,” [Léonce] added, looking at his wife as one looks at a valuable piece of personal property. He turns Edna into a thing or a commodity through his perception of her and his desire to control her actions.

You might also enjoy

Willa Cather’s review of The Awakening

Acting rebellious, Edna defies social convention in various ways. Back in New Orleans, she stops holding her Tuesday evening “at-homes;” she stomps on her wedding ring; and she moves out of her house into a smaller space of her own. She refuses to attend a family wedding and remembers her own as an “accident,” a revolt against her father and sister’s wishes.

Simultaneously, she witnesses the growth of her own spiritual life: “There was with her a feeling of having descended in the social scale, with a corresponding sense of having risen in the spiritual.” None of these minor outrages, even the collapse of her marriage, were Léonce to let her go, would necessarily have precipitated her suicide. The dilemma of how to mother her children appropriately, with the risk of subjecting them to the public shame she brings upon herself, seems to be the decisive factor.

A feminist framework

Chopin problematizes traditional roles and expectations for men and women by illustrating the dilemmas that arise when one troubles the waters by behaving in non-conformist ways. Hélène Cixous’ famous critique of the western binary system of gender definition (and conceptualizations that issue from it) provides an interesting framework with which to look at the novel.

The French feminist illustrates basic, two-part description of “patriarchal binary thought” with these contrasts:

Activity / Passivity

Sun / Moon

Culture / Nature

Head / Emotions

Intelligible / Sensitive

Logos / Pathos

On which side (left/right) would you place “male” and on which side “female,” according to typical definitions in our culture? The list continues… add your own.

Thinking / Feeling

Demanding / Suggesting

Directing / Manipulating

Teaching / Nurturing

Action / Passion

Mind / Nature

War / Love

Freedom / Security

Defining / Describing

Pointing / Indicating

Linear / Associative

Strong / Reliable

Muscley / Shapely

Sweat / Perspire

Triumph / Succeed

Command / Comply

Of course, such simple dichotomies (or 2-part systems of thought) are “reductive” or “essentializing” (in the words of many critics). These terms simplify complicated characteristics, fitting generalized features into neat boxes. There are gray areas between any polar opposites, and no one belongs, fully, to either of these artificial categories. Contemporary critics and theorists tend to think more in terms of a “continuum of gender and sexuality” or a vast range of possibilities between so-called male and female characteristics. This newer theory originates, in part, with Judith Butler’s work during the 1980s, particularly Gender Trouble.

Considering Edna Pontillier and Adèle Ratignolle

Think about Edna when we first meet her, and as she develops through the course of the novel. How does she fit traditional gender roles for women, and how does she branch away from such expectations? This question constitutes a major theme of the novel. We can look at Edna specifically in her role as a mother. SUNY-New Paltz graduate student Marissa Caston made an important connection between The Awakening and Cixous’ thoughts on mothering with this compelling, if dated quote from “The Laugh of the Medusa”:

In women there is always more or less of the mother who makes everything all right, who nourishes, and who stand up against separation; a force that will not be cut off but will knock the wind out of the codes.

Obviously, Edna is not a traditional “mother-woman” like her foil character Adèle Ratignolle. A foil character is one basically similar to the protagonist, yet differing in certain ways that serve to illuminate the protagonist more brightly or clearly (as in a tin-foil reflection). For example, Adèle is the quintessential mother-woman, an “angel in the house,” beautiful, earthy, usually pregnant, utterly ensconced in her domestic role as mother and nurturer. She does not question her position, nor complain of her duties.

In contrast to Adèle, Edna’s divergence from expected actions and behaviors becomes all the more striking. Their conversation on mothering is a key to the novel. Edna explains, “I would give my life for my children: but I wouldn’t give myself.” Perhaps she implies that a selfless or unfulfilled mother is no mother at all. One could interpret this statement multiple ways.

Full text of The Awakening by Kate Chopin (1899)

A rich array of characters

In a somewhat mechanical manner, various characters demonstrate or activate particular aspects of Edna’s awakening. The pianist Mademoiselle (Miss) Reisz models the independent woman as artist, utterly unconcerned with personal appearance or public scrutiny. She encourages Edna to sketch, to cultivate her own creativity. The novel does not put forth a woman who can be both an artist and a mother. Mademoiselle Reisz may even appear less “feminine” because she does not depend on a man, has no children, and takes no heed of social mores.

Two men factor as lovers in Edna’s sexual awakening. Robert Lebrun sees Edna as a person and provides a more equal meeting of the minds than her marriage can. Edna credits Robert with awakening her that summer at Grand Isle. He seems to love her generously, yet his desires are tinged with a possessiveness Edna cannot abide. She rejects outright the possibility of marriage, saying, “I am no longer one of Mr. Pontellier’s possessions to dispose of or not. I give myself where I choose.

If he were here to say, ‘Here, Robert, take her and be happy; she is yours,’ I should laugh at you both.” At this point, Edna has been sexually involved with Alcee Arobin, the town Casanova, who “detected her latent sensuality” and with whom she has a purely carnal, adulterous relationship. In contrast, she loves Robert and finds great comfort in him. Nevertheless, she no longer trusts in any sort of permanence in any relationship.

Ultimately, only Dr. Mandalet, well acquainted with human affairs of the heart, seems to understand Edna and may possibly have led her to some alternate solution than suicide. She explains to him at the story’s end, “perhaps it is better to wake up after all, even to suffer, rather than to remain a dupe to illusions all one’s life.” The kind doctor encourages her to confide in him saying, “I know I would understand, and I tell you there are not many who would – not many, my dear.” If only she had given this male ally a chance, and shared her dilemma with him.

Questions of ethnicity

The novel treats questions of ethnicity in interesting ways. Edna’s new, maverick way of life aside, she feels an outsider in both her Grand Isle and New Orleans communities because she is a Protestant rather than a Catholic Creole like her husband and acquaintances.

Via the omniscient narrator, Chopin condemns racist attitudes in her portrayal of Adèle’s deeply prejudiced view of Mexicans and African-Americans, particularly the degrading image of the young girl operating the foot pedal of the sewing machine for Madame LeBrun. As a rule in the text, skin color is assumed to be white and only specified otherwise in terms of difference.

Stylistic features and motifs

As an interesting stylistic feature, the novel incorporates episodes written in the Darwinian Naturalist vein, particularly those involving attention to the female, sexual drive. At various moments, Edna is pictured in an animalistic way, as a sharp-toothed creature of instinct. After waking at Madame Antoine’s house, she blooms sensually and tears at the bread with her teeth. When Robert leaves and she begins to understand her passion for him, she similarly bites her handkerchief. She sticks her pointed nails into Arobin’s palm, and she reminds him of “some beautiful, sleek animal waking up in the sun” (emphasis mine).

The motifs of swimming, of birds, of the lyric line si tu savais (if you only knew) all seem to converge in the final scene of the novel. Edna wades out into the sea where she experienced her first sensual awakening and, later, her powerful achievement of learning to swim. Birth and death converge as she immerses herself in water, the feminine element, par excellence. A few critics including Sandra Gilbert, argue that Edna does not commit suicide. What do you think?

— Contributed by Sarah Wyman, Associate Professor of English, SUNY-New Paltz

More about The Awakening by Kate Chopin

Wikipedia

Kate Chopin’s The Awakening: Struggle Against Society and Nature

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Related post: 10 Classic Banned Books by Women Authors

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Awakening by Kate Chopin: an analysis appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 16, 2018

The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman: an analysis

This analysis by Sarah Wyman of The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1892) highlights a long short story (or short novella) considered a feminist classic.

This story starts with a mystery: the house seems to have “something queer about it.”

As we read on, it becomes clear that the house is not the only thing strange about this story. The secluded, rented country home and the attic room the narrator inhabits come to represent or symbolize her situation and her very self. She lives under her physician/husband’s care as a patient (deemed abnormal), subjected to the “rest cure” as a treatment for what appears to be postpartum depression.

More broadly, we could see the prison-like room she inhabits (with barred windows, a gate on the stairs, rings in the walls, and a nailed-down bed) as symbolic of her situation as an upper-middle-class woman of a particular time and place (19th century USA). Living under patriarchal rule, she is discouraged from self-expression and productivity via work and writing.

Fiction in the form of first-person diaries

Gilman writes in the form of first-person diary entries penned by the narrator. We as readers are positioned as eavesdroppers, listening in on a conversation the narrator conducts with herself. This rhetorical choice lends a sense of immediacy to the writing. Sometimes, the narrator recounts an event that transpired earlier in the day or recent past. More often, however, and increasingly as the text evolves, she narrates in the present tense.

We thus witness the workings of her unusual mind, even as it comes up with new thoughts and discoveries: “I wonder – I begin to think – I wish John would take me away from here!” (section 4). Ironically, as the narrator claims to improve physically and emotionally, her condition, according to the norms of psychological behavior, worsens. The language reflects this deterioration and dissonance, becoming more highly charged, the syntax more fragmented, the interruptions more frequent. The narrator eventually loses her grip on the reality we all share and lurches into the world of her own creative imagination or hallucination.

Ultimately, the narrator manages to project herself into the persona of the woman she sees in the wallpaper. Standing beside her, we would likely see no such being. Yet, the narrator and woman trapped in the wallpaper pattern become one and the same. By extension, they symbolize all women living under this particular form of oppression.

See Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1913 essay

“Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper”

“Suicidal” wallpaper

The gruesome details of the “suicidal” wallpaper pattern set an ominous tone, even of paranoia: “There is a recurrent spot where the pattern lolls like a broken neck and two bulbous eyes stare at you upside down” (section 2). The violence of her grotesque descriptions seems to express extreme frustration. Such imagery could indicate an image of her very self as a monster, since she either refuses or fails to play the “good mother” role or the type of 19th century feminine perfection: an angel in the house.

The narrator’s relationship with her physician/husband John proves to be a key to her highly symbolic situation. Utterly condescending, he often addresses her as though she were a child, demanding, for example, “What is it, little girl?”(section 5). He seems to have imprisoned her.

Writing itself becomes for her both work and rebellion, for he has denied her this outlet, this access to creative production and expression, and this means of finding a voice and thus establishing an identity. Nevertheless, she manages to achieve all these necessities, through her increasingly secretive journaling.

One could call the narrator an artist of the self, as the writing she carries out creates a world, which in turn, defines her very being. The text turns meta-discursive, or the writing comments reflexively on itself as she writes, “I don’t know why I should write this./ I don’t want to./ I don’t feel able./…it is such a relief!” (section 4).

An ironic conclusion

The conclusion proves additionally ironic with the infantilized image of her “creeping” or crawling, like a baby. Somehow, she has constructed a reality she can bear to inhabit. Yet, she has become utterly estranged from herself (one definition of being psychotic).

Many readers see the narrator as Jane herself in her final cry to John, “I’ve got out at last, in spite of you and Jane! And I’ve pulled off most of the paper, so you can’t put me back!” One could read the tight-leashed, yet high-voiced narrator at the end as either utterly defeated or triumphant, in that she has garnered the freedom to express a finally authentic, independent self.

— Contributed by Sarah Wyman, Associate Professor of English, SUNY-New Paltz

How The Yellow Wallpaper begins

It is very seldom that mere ordinary people like John and myself secure ancestral halls for the summer.

A colonial mansion, a hereditary estate, I would say a haunted house, and reach the height of romantic felicity—but that would be asking too much of fate!

Still I will proudly declare that there is something queer about it.

Else, why should it be let so cheaply? And why have stood so long untenanted?

John laughs at me, of course, but one expects that in marriage.

John is practical in the extreme. He has no patience with faith, an intense horror of superstition, and he scoffs openly at any talk of things not to be felt and seen and put down in figures.

John is a physician, and PERHAPS—(I would not say it to a living soul, of course, but this is dead paper and a great relief to my mind)—PERHAPS that is one reason I do not get well faster.

You see he does not believe I am sick!

And what can one do?

If a physician of high standing, and one’s own husband, assures friends and relatives that there is really nothing the matter with one but temporary nervous depression—a slight hysterical tendency—what is one to do?

Read the full text of The Yellow Wallpaper on this site.

You might also enjoy:

Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman: an analysis

The post The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman: an analysis appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 15, 2018

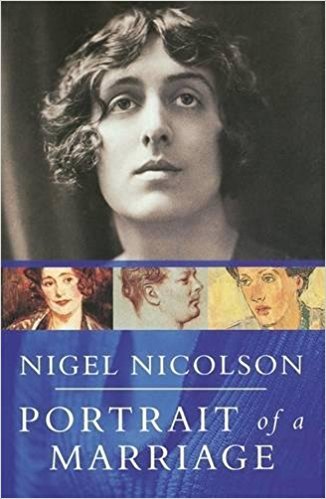

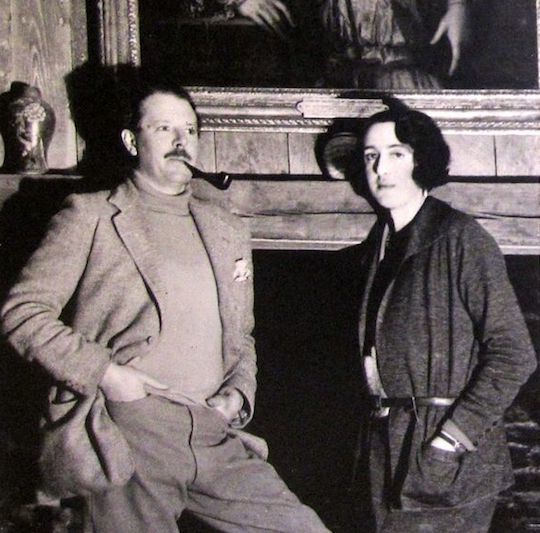

Portrait of a Marriage: Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson

Portrait of a Marriage: Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson by one of the couple’s sons, Nigel Nicolson, is the story of an unusual marriage. Vita, a novelist and poet was known for her role in the Bloomsbury circle and her intense friendship with Virginia Woolf; Harold was a diplomat and scholar. Though neither admitted it to the other when they were courting and in the early days of their marriage, both were primarily attracted to members of their own sex. Ultimately, they allowed one another the freedom to pursue other affairs during the course of their long marriage.

In Portrait of a Marriage, Nigel Nicolson publishes his mother’s memoir and adds his own commentary, which resulted from what he learned from his parents’ letters. Vita’s love affairs with a number of women (which resulted in much drama) and Harold’s discreet relationships with men didn’t hinder this successful, loving marriage and the happiness of their two sons, Nigel and Benedict. Nigel’s insightful Portrait of a Marriage shines a light on a fascinating couple.

From the 1973 Weidenfeld and Nicolson edition of Portrait of a Marriage: Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson, by Nigel Nicolson:

The view of a son

“Now that I know everything, I love her more as my father did, because she was tempted, because she was weak. She was a rebel … rejecting the conventions that marriage demands exclusive love, and that women should love only men, and men only women … Yes, she may have been mad, as she later said, but it was a magnificent folly. She may have been cruel, but it was cruelty on a heroic scale.

How can I despise the violence of such a passion? How could she regret that the knowledge of it should reach the ears of a new generation, one so infinitely more compassionate than her own?”

So writes Nigel Nicolson of his mother, Vita Sackville-West, in reaction to her confession — an attempt to purge her heart and mind of a love for another woman — written in 1920, when she was 28 and in the eighth year of her marriage to Harold Nicolson.

Portrait of a Marriage by Nigel Nicolson on Amazon

“The strangest and most successful union”

Sir Harold, distinguished writer, scholar, diplomat, and statesman, was a social, extroverted being; Vita, a poet and novelist, was the product of mingled Spanish and English blood, once described as “romantic, secret, and undomesticated.” They both thought marriage “unnatural,” but realized that, “as a happy marriage is ‘the greatest of human benefits,’ husband and wife must strive hard for its success. Each must be supple enough, subtle enough, to mould their characters and behaviour to fit the other’s facet to facet, convex to concave.”

Which is precisely what they managed, achieving in time “the strangest and most successful union that two gifted people have ever enjoyed.”

A mother’s passions and a son’s perspective

This autobiography — “a document unique in the vast literature of love” — describes Vita’s sumptuous childhood at Knole, her long love affair with a girl that coincided with her long engagement to Harold, and her elopement, after seven years of marriage, with Violet Trefusis.

She tells the story of this shattering experience with complete candor, partly to clear her heart of a passion which was growing cold, and partly because she believed, in 1920, that one day society would accept that women can love women, men can loved men, and that a marriage as deeply rooted as hers could survive and actually be enriched by infidelity.

To his mother’s autobiography Nigel Nicolson has added the evidence of contemporary diaries and letters to explain in more detail what happened and what resulted. He describes Vita’s family background, starting with her grandmother Pepita, the Spanish dancer, and here even more remarkable mother, Lady Sackville. He traces the growth of his parents’ marriage from its first tumultuous years to the peace of their old age at Sissinghurst Castle. He tells of Vita’s gentle love for Virginia Woolf, and Virginia’s for her.

It is the story of a non-marriage which became a marriage successful beyond their dreams, because it was based on mutual respect and tolerance, and enduring love.

An excerpt from the preface

It is the story of two people who married for love and whose love deepened with each passing year, although each was constantly and by mutual consent unfaithful to the other. Both loved people of their own sex, but not exclusively. Their marriage not only survived infidelity, sexual incompatibility, and long absences, but it became stronger and finer as a result. Each came to give the other full liberty without inquiry or reproach.

Honour was rooted in dishonour. Their marriage succeeded because each found permanent and undiluted happiness only in the company of the other. If their marriage is seen as a harbour, their love affairs were mere ports of call. It was to the harbour that each returned; it was there that both were based.

This book is therefore a panegyric of marriage, although it describes a marriage that was superficially a failure because it was incomplete. They achieved their ideal companionship only after a long struggle, which was still not ended when Vita wrote the last words of her confession, but once achieved it was unalterable and lifelong, and they made of it … the strangest and most successful union that two gifted people have ever enjoyed. ( — Nigel Nicolson, from the Preface of Portrait of a Marriage)

Vita was the inspiration for Virginia Woolf’s Orlando

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Portrait of a Marriage: Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 14, 2018

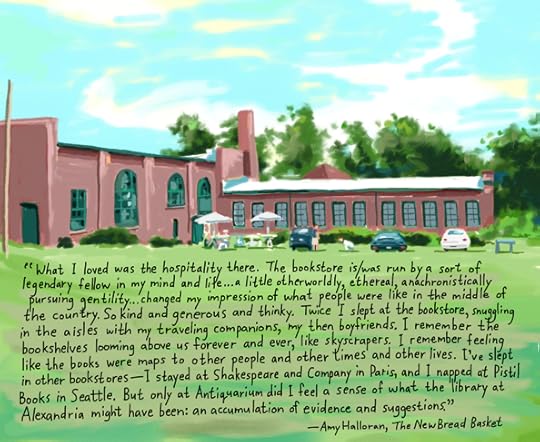

Footnotes From the World’s Greatest Bookstores: 3 Women Writers’ Adventures

Those who write love to read, and those who love to read, love bookstores with a passion. Bob Eckstein, the noted New Yorker cartoonist has created a unique and beautiful book, Footnotes From the World’s Greatest Bookstores: True Tales and Lost Moments from Book Buyers, Booksellers, and Book Lovers.

The 75 meticulously detailed paintings of fantastic bookstores by Eckstein feature some of the most charming and iconic bookstores around the world. The art is embellished with charming, bittersweet, and often humorous anecdotes by writers, thinkers, and dreamers who have visited them. Some of these bookstores have gone by the wayside, many, thankfully, are still open for business. Here, Bob shares the bookstore adventures of three contemporary women authors.

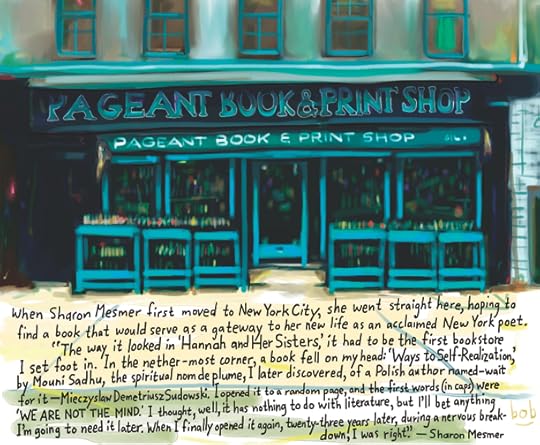

Pageant Book & Print Shop on 12th Street, Manhattan was in business from 1946 to 1999 until it became an online store. It has since returned as a small print shop on 4th Street.

When Sharon Mesmer first moved to New York City, she went straight here, hoping to find a book that would serve as a gateway to her new life as an acclaimed New York poet. “The way it looked in ‘Hannah and Her Sisters,’ it had to be the first bookstore I set foot in.

In the nether-most corner, a book fell on my head: ‘Ways to Self-Realization,’ by Mouni Sadhu, the spiritual nom de plume, I later discovered, of a Polish author named—wait for it—Mieczyslaw Demetriusz Sudowski. I opened it to a random page, and the first words (in caps) were ‘WE ARE NOT THE MIND.’ I thought, well, it has nothing to do with literature, but I’ll bet anything I’m going to need it later. When I finally opened it again, twenty-three years later, during a nervous breakdown, I was right.” (— Sharon Mesmer)

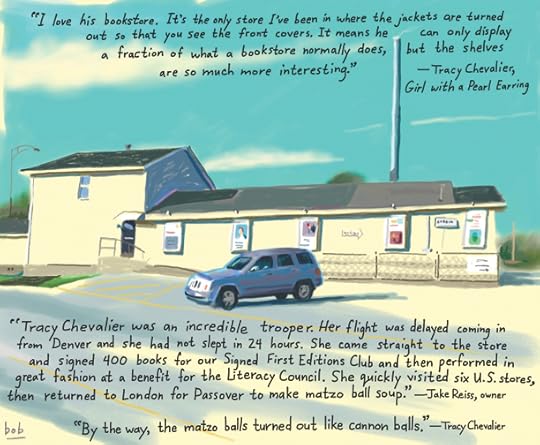

Alabama Booksmith of Birmingham sells only exclusively signed copies. All books are sold at regular retail prices and are displayed by cover instead of just spines.

“Tracy Chevalier was an incredible trooper. Her flight was delayed coming in from Denver and she had not slept in 24 hours. She came straight to the store and signed 400 books for our Signed First Editions Club and then performed in great fashion at a benefit for the Literacy Council. She quickly visited six U.S. stores then returned to London for Passover to make Matzo Ball soup.” – Jake Reiss, owner

“[BTW,] the matzo balls turned out like cannon balls. I love his bookstore. It’s the only store I’ve ever been in where the jackets are turned out so that you see the front covers. It means he can only display a fraction of what a bookstore normally does, but the shelves are so much more interesting.” (– Tracy Chevalier)

The Antiquarium Bookstore is located in Brownville, Nebraska, one of the three ‘Book Towns’ in the United States. Book Towns are rural towns with a large number of used book or antiquarian book stores where bibliophiles gather and literary festivals take place.

“What I loved was the hospitality there. The bookstore is/was run by a sort of legendary fellow in my mind and life…a little otherworldly, ethereal anachronistically pursuing gentility … changed my impression of what people were like in the middle of the country. So kind and generous and thinky.

“Twice I slept at the bookstore, snuggling in the aisles with my traveling companions, my then boyfriends. I remember the bookshelves looming above us forever and ever, like skyscrapers. I remember feeling like the books were maps to other people and other times and other lives. I’ve slept in other bookstores–I stayed at Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and I napped at Pistil books in Seattle. But only at Antiquarium did I feel a sense of what the library at Alexandria might have been: an accumulation of evidence and suggestions.” (– Amy Halloran)

Bob Eckstein is an award-winning illustrator and writer, New Yorker cartoonist, snowman expert and author of the New York Times bestseller, Footnotes from the World’s Greatest Bookstores. Globe Pequot is coming out with a new edition of his holiday classic, The History of the Snowman in 2018. Visit him on the web at BobEckstein.com.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Footnotes From the World’s Greatest Bookstores: 3 Women Writers’ Adventures appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 13, 2018

Beatrix Potter’s Letters to Children: The Path to Her Books

Twenty-something Beatrix Potter (1866 – 1943) was conflicted. She had two consuming interests at the time: art and the study of fungi. With the exception of letter writing and a journal which she started in 1881—in elaborate code, by the way—becoming a woman of letters was nowhere in sight. What happened to set and redirect the course of her life’s work?

Helen Beatrix Potter was born to wealth, so she didn’t need to earn a living. Her ambitions were more personal, bubbling up from some inner pool. Her parents, Rupert and Helen Leech Potter, both hailed from families whose riches were manufactured, if you will, in Manchester’s booming cotton industry. Born in London to a posh South Kensington address, she and her younger brother, Bertram, were raised in the usual way for children of that social class—by a series of minders starting with nurses, then nannies, and finally governesses.

An avid interest in the natural world

Lessons were held in the upstairs nursery. The nursery was also home to an elaborate parade of pets. At various times, the two children had dogs, birds, lizards, mice, squirrels, a bat, and, of course, rabbits. Beatrix and the six-years-younger Bertram showed early interest in natural history and early aptitude in art. They traveled with their parents (and staff) on long holidays.

Each summer, Rupert Potter would take a lease on a country house in Scotland or, starting in 1882, the Lake District. The children sketched and collected wildflowers, insects, fossils, and mushrooms. While the adolescent Bertram was sent off to a traditional English public school and later to Oxford, Beatrix stayed at home. “I’m glad I did not go to school,” she later wrote, “it would have rubbed off some of the originality (if I had not died of shyness or been killed with over pressure).” She had private art lessons and completed a course of study at a South Kensington art school.

The young Beatrix was often in ill health, capped by a serious case of rheumatic fever in 1887. She considered herself plain and was painfully shy. At age seventeen, she wrote in her journal, “I feel like a cow in a drawing room.” So it is hardly surprising that her interests tended to the solitary.

She had a passion for drawing and a rich imagination. There were consolations— her beloved pets and the world outdoors. She once recalled, “I do not remember a time when I did not try to invent pictures and make for myself a fairyland amongst the wild flowers, the animals, fungi, mosses, woods and streams, all the thousand objects of the countryside.” Reading was a joy and a solace.

Her favorite books and authors

A list of her childhood books—sent in response to a query from the Denver Public Library in the 1920s—included Alice in Wonderland, Black Beauty, Uncle Remus, and Little Women (You can find a link to Potter’s list here). She remembered her Nurse Mackenzie reading aloud from Aesop’s Fables, Hans Christian Anderson, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She also credited this Highland nurse for her lasting belief in fairies. Potter claimed to have learned to read with the weighty tomes of Sir Walter Scott. In her later years she particularly mentioned enjoying the novels of Sarah Orne Jewett and Willa Cather.

You might also enjoy:

Beatrix Potter’s Gardening Life by Marta McDowell

Her last governess and companion, Annie Carter, was only three years her senior. Carter stayed on until Beatrix was eighteen years old. They remained friends. Carter left the Potters’ employ to marry Edwin Moore. The couple settled in Wandsworth, a London borough on the other side of the Thames. Beatrix would often visit, driven there in the family carriage or pony cart. As the Moore family grew—Annie and Edwin eventually had eight children—Beatrix remained close. The Moores’ firstborn was a boy, born on Christmas Eve, 1887. They named him Noel.

Beatrix Potter around the age of 20, at right

Photo courtesy of The Beatrix Potter Society

In 1892 while on a trip to Cornwall with her family, Beatrix Potter sent an unusual letter to Noel Moore. She was twenty-five, he was four. Potter wrote, “I have come a very long way in a puff-puff to a place in Cornwall, where it is very hot, and there are palm trees in the gardens.” The letter continues, 260 words total, in simple language that would have appealed to Noel and his younger brother, Eric, and amused their mother.

Potter described the sights of Falmouth and its working harbor. But in addition to putting her observations into words, she added sketches, vignettes of the train, the Potter family in front of the public gardens, a steamboat on the harbor, tall ships, chickens, dogs, and cats in the neighborhood, and, my personal favorite, a fishing boat at work, with men in the boat above the waves and fish and crabs below. It is the first known picture letter that Beatrix Potter wrote, but it was far from her last.

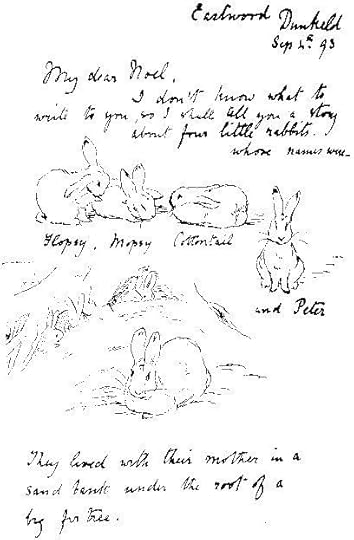

The next that survives, also written to Noel, came the next year in September 1893. It is arguably one of the most famous letters in the English language, certainly in the history of children’s literature. It opens, “My dear Noel, I don’t know what to write to you, so I shall tell you a story about four little rabbits whose names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail, and Peter.” Over eight pages, the letter lays out the entire tale with sixteen illustrations in ink. While Beatrix did own a rabbit named Peter Piper, unlike the letter from Cornwall, this was brand new fiction, custom-made for a real child.

Letter from Beatrix Potter to Noel Moore, 1893

Letters grow into books

She wrote many picture letters to the Moore children over the years and it was their mother — her friend and former governess — who first suggested that Beatrix make them into books. She borrowed the letters back in 1895, copied and amended the stories, and the rest is publication history. More about that here.

About The Tale of Peter Rabbit, she wrote, “I have never quite understood the secret of Peter’s perennial charm. Perhaps it is because he and his friends keep on their way, busily absorbed with their own doings. They were always independent. Like Topsy—they just “grow’d.”

The secret to her success?

Perhaps the secret to Potter’s success was that she also just “grow’d.” Sometimes hurdles were put in her way, other times gates were opened to her. She never seemed to avoid trying out a new path. Potter married William Heelis, a country solicitor, when she was forty-seven. They lived in a small village in the Lake District where she had acquired several farms.

Her interests included antique oak furniture, preservation of the countryside, and raising Herdwick sheep. While Beatrix and William Heelis never had children of their own, she continued to write, to draw, and to send picture letters to children of her friends. The latest that survives is dated less than a year before her death.

For the writers among you, let me close with Beatrix Potter’s description of her writing methods:

“I think I write carefully because I enjoy my writing, and enjoy taking pains over it. I have always disliked writing to order; I write to please myself … My usual way of writing is to scribble, and cut out, and write it again and again. The shorter and plainer the better.”

Well said, Miss Potter.

For more about Beatrix Potter’s interests in fungi, there is a good summary on Brain Pickings.

In addition to the books already listed on Beatrix Potter’s biography page here on Literary Ladies, for this article I also consulted:

Beatrix Potter’s Americans: Selected Letters edited by Jane Crowell Morse

Beatrix Potter’s Letters edited by Judy Taylor

Letters to Children from Beatrix Potter edited by Judy Taylor

The Journal of Beatrix Potter: 1881 to 1897 edited by Leslie Linder

Marta McDowell teaches landscape history and horticulture at the New York Botanical Garden and consults for private clients and public gardens. Timber Press has published her recent books including The World of Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Frontier Landscapes that Inspired the Little House Books in September 2017. All the Presidents’ Gardens made the New York Times bestseller list in 2015 and won an American Horticultural Society book award.

Beatrix Potter’s Gardening Life won a 2014 Gold Award from the Garden Writers Association and is in its sixth printing. Marta is working on a revision of her first book, Emily Dickinson’s Gardens, due out in a full color edition by Timber Press in 2019.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Beatrix Potter’s Letters to Children: The Path to Her Books appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 11, 2018

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon by Rebecca West (1941)

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey Through Yugoslavia by Dame Rebecca West is ostensively a travelogue, published as a two-volume set of more than 1,100 pages and half a million words in 1941. Published both in the United Kingdom and the US., the book presents an exhaustive history of the land and people of the Balkans. Publication coincided with the Nazi invasion of Yugoslavia, and West’s intention was to “show the past side by side with the present it created.”

West researched the book during a 6-week 1937 trip she made there with her then-husband, traveling over much of the terrain of the old borders, including Croatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Serbia, and more. Sadly, by the time she fashioned her research into the tome and had it published, she was compelled to add the dedication: “To my friends in Yugoslavia, who are now all dead or enslaved.”

Though often placed in the travel category, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon transcends its genre and is a deep study of culture, politics, and geography of the region as it was at the time. Of course, Yugoslavia no longer exists. The two-book set has appeared on lists of “Best nonfiction books of the twentieth century” and it has been praised by readers and reviewers alike as an unusual and extraordinary work of nonfiction.

Rebecca West’s intellect and prose were always appreciated by her contemporaries and the era’s critics, though in all, her legacy is considered by many underappreciated.

“Were I to go down into the market-place, armed with the powers of witchcraft, and take a peasant by the shoulders and whisper to him, ‘In your lifetime, have you known peace?’ wait for his answer, shake his shoulders and transform him into his father, and ask him the same question, and transform him in his turn to his father, I would never hear the word ‘Yes,’ if I carried my questioning of the dead back for a thousand years. I would always hear, ‘No, there was fear, there were our enemies without, our rulers within, there was prison, there was torture, there was violent death.”

Original covers of the 1941 two-book set

This 1941 review by John Selby (Literary Guideposts) of Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is typical of the praise this classic work received:

Rebecca West could have told the story of what was once Yugoslavia in half the 500,000 words she used in Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, but I am glad she did not.

As this enormous two-volume work stands now, it contains not only the history and the pertinent fact, but the spirit. Miss West is a writer of prose bordering on genius, and an observer of almost fanatical thoroughness.

Miss West spent years poking about Yugoslavia, often with a Yugoslavian whose wife was a peculiarly unfortunate German. These and other characters in the long narrative are foils to the facst which Miss West uncovers. As they move through the flashing Yugoslavian background they reflect on the tangled past of this strangely assorted people.

You Might Also Like:

The Birds Fall Down by Rebecca West

The country may never again be called Yugoslavia, but some of the people will remain essentially the same people the author took such pains to know.

These are an almost incredible people, these Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. They have been shaped by their bare mountains and fertile oases, primarily, but also by those who have tried to subjugate them, and have succeeded only in conquering them.

There was Rome, many centuries ago, and then a period of glory for the Serbs, and then the Byzantine Empire flowing over and from the east. Later Venice and Austria came from the north, and the Turks with fanatical brutality came again from the east.

The Turks remained over the land five centuries, and the Balkan wars which were the prelude to the World war were only the last throes of the struggles against them. Now the Nazis have come from the more distant north, and the strong faces of the people are again set in lines of hard suffering.

Miss West has no illusions about these man and women, but she loves them. It would be hard to read Black Lamb and Grey Falcon without arriving at the same love though the whirl of color the book throws about them.

No writer has produced a stranger combination of history, travel, racial analysis and sympathetic understanding than Rebecca West has in her Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. This huge two-volume work contains all anybody would need to know about what once was Yugoslavia. It probably contains more than the Yugoslavs know themselves. (John Selby, Literary Guideposts syndicated column, 1941)

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon by Rebecca West on Amazon

How it begins …

I raised myself on my elbow and called through the open door into the other wagon-lit: — ‘My dear, I know I have inconvenienced you terribly by making you take your holiday now, and I know you did not really want to come to Yugoslavia at all. But when you get there you will see why it was so important that we should make this journey, and that we should make it now, at Easter. It will all be quite clear, once we are in Yugoslavia.’

There was, however, no reply. My husband had gone to sleep. It was perhaps as well. I could not have gone on to justify my certainty that this train was taking us to a land where everything was comprehensible, where the mode of life was so honest that it put an end to perplexity. I lay back in the darkness and marveled that I should be feeling about Yugoslavia as if it were my mother country, for this was 1937, and I had never seen the place till 1936. Indeed, I could remember the first time I ever spoke the name ‘Yugoslavia,’ and that was only two and a half years before, on October 9, 1934. (excerpted from Black Lamb and Grey Falcon by Rebecca West)

More about Black Lamb and Grey Falcon by Rebecca West

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Excerpt of Part One in The Atlantic

1941 review in The New York Times

The Judgement of Rebecca West (a contemporary view)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Black Lamb and Grey Falcon by Rebecca West (1941) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974-1977 by Adrienne Rich

The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974-1977 (1978) appeared early on in Adrienne Rich’s (1929 – 2012) long career and solidified her position as a leader who articulated the central ideas of the second wave U.S. feminist movement.

These poems, about and for women, envision an alternative to a patriarchal system in which men control the avenues of power and the definitions of female existence. They establish the primary concerns of Rich’s life’s work to promote:

solidarity among women and the power that emerges from their collaboration;

the legitimacy of lesbian existence within a homophobic world;

a re-conceptualization of motherhood as institution

the mind’s relation to the body

and the destructive nature of a dominant culture that renders its marginalized members invisible and silent.

Rich refuses any division between the artistic and political aspects of her poetry as she uses both to explore social relations in a world hostile to female identity and creativity.

“Power”

The first poem, “Power,” describes Marie Curie’s discovery of radiation and her ensuing death, as the poet links the notion of woman’s power with the danger of not knowing how to handle it.

“Power” by Adrienne Rich

Living in the earth-deposits of our history

Today a backhoe divulged out of a crumbling flank of earth

one bottle amber perfect a hundred-year-old

cure for fever or melancholy a tonic

for living on this earth in the winters of this climate

Today I was reading about Marie Curie:

she must have known she suffered from radiation sickness

her body bombarded for years by the element

she had purified

It seems she denied to the end

the source of the cataracts on her eyes

the cracked and suppurating skin of her finger-ends

till she could no longer hold a test-tube or a pencil

She died a famous woman denying

her wounds

denying

her wounds came from the same source as her power

“Phantasia for Elvira Shatayev”

The second poem, “Phantasia for Elvira Shatayev,” celebrates the courage and commitment of a group of woman who perished together on a climbing expedition. In the poem “Origins and History of Consciousness,” Rich equates “The drive / to connect” with “the dream of a common language.” Rich’s notion of a common language stresses a desire for the direct communication of care and concern within a community of speakers and the power that ensues from this achievement.

At this point in Rich’s evolving process — separatist, radical feminist — she reserves dialogue for the shared experience of women. Although they may remain only dreams, such creative acts can bring forth new realities in the face of a damaging, male-dominated culture where women are not full participants.

Dream of a Common Language by Adrienne Rich on Amazon

“Twenty-One Love Poems”

The central cycle of twenty-one sonnet-like lyrics, “Twenty-One Love Poems,” originally appeared as a separate volume. These poems incorporate the personal and the public as they invoke the experience of physical and emotional love between women integrated within a broader social reality. As several critics have commented, the intensely erotic “(The Floating Poem, Unnumbered)” resists the dominant male discourse by breaking the formal pattern and omitting a roman numeral.

Although these works correspond with a period in her life when Rich’s marriage to Harvard Economics professor Alfred Conrad had ended and she was involved in lesbian relationships, (including one with Michelle Cliff that would last until her death), the poems are socially engaged rather than overtly autobiographical or confessional.

Critics’ responses

The critics’ varied response to The Dream of a Common Language sparked debates that increased Rich’s popularity and notoriety in the public sphere. By 1975, Barbara Gelpi and Albert Gelpi had already declared Rich a “pioneer, witness and prophet” of the U.S. women’s movement . (Gelpi and Gelpi 1993, xi). Many celebrated her attention to women’s history, her rhetorical talent, and her outspoken approach to taboo topics.

Others warned against her generalized category of womanhood and condemned what they saw as the continuation of an obsessively anti-male focus on patriarchal power. Sensing this backlash, Rich shifted her lens from the world of men to that of women in both Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (1976) and Dream of a Common Language. Nevertheless, several critics rejected her incorporation of poetry and politics: some declared her work overtly propagandistic, didactic, and dogmatic.

Legacy

At the time of her death, Rich enjoyed an international following. Dream of a Common Language marks a pivotal moment early in her literary career when she leaves traditional forms behind and exhibits the use of her creative intelligence to re-vision the world with “fresh eyes”.” (Rich 1979, 35).

Rich, who was white, won the 1974 National Book Award for Diving into the Wreck. In a characteristic move, she refused the award as an individual but accepted it with fellow nominees Alice Walker, who is black, and Audre Lorde, who was also black, “in the name of all women whose voices have gone and still go unheard in a patriarchal world.” Rich leaves her mark on today’s popular culture as an innovative, anti-racist feminist who maintained her commitment to dialogue as an instrument for change in the world.

Contributed by Sarah Wyman, Associate Professor of English, SUNY-New Paltz

Further Reading

Cooper, Jane Roberta, ed. 1984. Reading Adrienne Rich: Reviews and Re-Visions, 1951-81. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Gelpi, Barbara Charlesworth and Albert Gelpi, eds. 1993. Adrienne Rich’s Poetry and Prose: Poems, Prose, Reviews and Criticism. New York: W.W. Norton.

Keyes, Claire. 1986. The Aesthetics of Power: The Poetry of Adrienne Rich. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Langdell, Cheri Colby. 2004. Adrienne Rich: The Moment of Change. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Martin, Wendy. 1984. An American Triptych: Anne Bradstreet, Emily Dickinson, Adrienne Rich. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Nelson, Cary. 1981. “Meditative Aggressions: Adrienne Rich’s Recent Transactions with History.” In Our Last First Poets: Vision and History in Contemporary American Poetry. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Rich, Adrienne. 1979. “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision 1971.” On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose 1966-1978. New York: Norton.

Vendler, Helen. 1980. Part of Nature, Part of Us: Modern American Poets. Cambridge, MA: Harvard.

Werner, Craig. 1988. Adrienne Rich: The Poet and Her Critics. Chicago: American Library Association.

A shorter version of this essay appears in Women’s Rights: Reflections in Popular Culture. Ed. Ann Savage. Greenwood, 2017, 116 – 117.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974-1977 by Adrienne Rich appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 5, 2018

Frances Hodgson Burnett

Frances Hodgson Burnett (November 24, 1849 – October 29, 1924) was born in Cheetham, England. She emigrated to the U.S. with her mother and siblings when she was in her teens, and started publishing stories in magazines to help support her family.

Victorian literature often had a rags-to-riches theme, or vice versa. Frances Hodgson Burnett’s own life reflected that theme. When she was born in England in 1840, she was one of five children in a household headed by a prosperous tradesman. He died when she was three, and the family’s fortunes plummeted.

See also: Quotes from The Secret Garden

Rags-to-riches in life and literature

Frances’s mother took her and her siblings and emigrated to the U.S., settling in rural Tennessee. Frances always showed an independent streak, was very clever, and had a knack for storytelling. Her girlhood, according to the biography of her life by Ann Thwaite, Waiting for the Party, had its ups and downs. There were parties and picnics, but also great struggles to earn enough money to keep the family afloat.

That’s when Frances started to write. Much like Louisa May Alcott before her, she did so more from a desire to support her family than out of any grand literary ambitions. She sent her first story to a woman’s magazine, stating bluntly: “My object is remuneration.”

She succeeded so well at selling stories to magazines that a steady income was hers to enjoy. Her earnings were enough not only to help her family, but to pay for a trip back to her native England at age 22, the first of many such trips.

Incredibly productive

During her writing career that spanned some fifty years, Burnett produced over fifty books and thirteen stage plays. Most have been forgotten, swept into the literary dustbin that contains the legions of over-sentimental stories that were produced in that era. But she produced three works that endured — Little Lord Fauntleroy, The Secret Garden, and A Little Princess. They each had strong, offbeat characters and rose above the sugary sweetness and morality of children’s tales of the era.

Writing in her garden helped her keep up her spirits in her own life, and contributed to one of her most popular works, The Secret Garden. It’s hard to say which is the more beloved of her works, the latter or A Little Princess. Burnett also helped write the theatrical versions of her books during her lifetime.

Sara Crewe: or, What Happened at Miss Minchin‘s was serialized in 1887 and published as a novella in 1888. This novella was the predecessor of what developed into A Little Princess. The Lost Prince (1915) also rose above the pack of the usual pablum, though it’s not as well known as the trio of aforementioned books.

Little Lord Fauntleroy

Though she had enjoyed great success in selling stories from the very start of her writing career as a teen, Little Lord Fauntleroy is the story that put Burnett on the literary map. It was serialized in St. Nicholas magazine in 1885 and 1886, and published as a book shortly thereafter.

The novel tells of young Cedric, who lives in poverty with his widowed mother in New York. It’s revealed that he is Lord Fauntleroy, heir to the Earl of Dorincourt. Alison Lurie, in Don’t Tell the Grown-Ups: Subversive Children’s Literature, wrote that it’s a “version of the almost universal childhood fantasy that one doesn’t really belong in this dreary little house or flat with these boring, ordinary people — that one’s real parents are important and exciting and live in a great mansion, if not a castle.”

Burnett based the character of Cedric on her younger son, Vivian. Writes Lurie, “Cedric himself is by no means the prig and sissy he is assumed to be by people who haven’t read the book. Part of the prejudice against him is probably due to the Little Lord Fauntleroy costume, which so many unhappy English and American boys were forced into at the end of the last century …”

A rich woman with spendthrift ways

Even before Little Lord Fauntleroy, Burnett’s stories and now-forgotten novels had made her wealthy. In the eearly 1880s, she and her then-husband and sons lived in Washington, D.C., very near their friend President James Garfield. By the 1890s, she had also bought a home in England.

She was a spendthrift, but also quite generous, using the royalties from her books to buy and rent houses for relatives, and showering gifts on all that she knew. She also indulged in expensive art and clothing, earning the nickname “Fluffy” for her frivolous ways.

Like L.M. Montgomery, who came a generation after her and also grappled with depression and legal troubles, Burnett wished above all to spread joy to readers as well as the people in her life. “There ought to be a tremendous lot of natural splendid happiness in the life of every human being,” she wrote.

Loss of a son and other troubles

Both of Burnett’s marriages ended bitterly, even scandalously, and since she was a famous author, the bad publicity that resulted caused inordinate stress. But she was a devoted mother, and quite enjoyed her sons, Lionel and Vivian.

When Lionel, the older of the two boys, contracted tuberculosis, she bought him costly toys, and did everything possible to keep his spirits up — including hiding from him the fact that he was seriously ill, and taking him from one European sanitorium to another. His death in 1890 at age 16 plunged her into depression, something she had experienced before and would grapple with for the rest of her life.

Death and legacy

Lionel’s death, her marital woes, and depression created a gap in what had been quite a prolific career. By the early 1900s, Burnett’s work had fallen out of favor, as the florid writing style of the 19th century was no longer in vogue. Fortunately, Burnett recovered her spirits to create her most enduring works, A Little Princess (1905), and The Secret Garden (1911) later in her life and career.

Frances Hodgson Burnett died at the age of 74 in Nassau County, Long Island, NY, in 1924, and is buried in Roslyn Cemetery.

You might also like: Quotes from A Little Princess

More about Frances Hodgson Burnett on this site

Illustrations from Sara Crewe (1888)

Quotes from A Secret Garden

Quotes from A Little Princess

Major Works

Frances Hodgson Burnett wrote more than 50 novels, but these are the ones that have endured:

Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886)

Sara Crewe, or What Happened at Miss Minchin’s (1888)

A Little Princess (1905)

The Secret Garden (1911)

The Lost Prince (1915)

Biographies about Frances Hodgson Burnett

Waiting for the Party: The Life of Frances Hodgson Burnett by Ann Thwaite

Frances Hodgson Burnett: Beyond the Secret Garden

by Angelica Shirley Carpenter & Jean Shirley

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of her books on Goodreads

Carson-Newman College – Letters of Frances Hodgson Burnett

Frances Hodgson Burnett, Legend of Children’s Literature

Film adaptations of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s works

The Secret Garden (1949)

The Secret Garden (1975)

The Secret Garden (1993)

A Little Princess (1939)

A Little Princess (1997)

Little Lord Fauntleroy (1936)

Little Lord Fauntleroy (1995)

Read and listen online

Project Gutenberg

Audio versions on Librivox

Visit

The Official Website of Central Park – Burnett Fountain – New York, NY

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Frances Hodgson Burnett appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.

January 3, 2018

My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin (1901)

My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin (1901) was this author’s first novel. Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin went on to become one of the most prominent of Australian authors of her era. She wrote this novel when she was a teenager, and it was published in her twenty-first year.

It’s the story of tomboyish Sybylla Melvyn, a high-strung, imaginative girl from the Australian countryside. When her parents fall on hard times, they send her to live with her grandmother in another part of the country. There she meets Harold Beecham. Convinced that she’s ugly and useless, Sybilla is surprised when the wealthy young man proposes marriage. Sybilla is then farmed out to be a domestic servant for a family to whom her father owes money. Despondent, she has a breakdown and returns to her parents’ home.

Beacham tracks her down and reiterates his proposal. Sybilla, determined to become a writer, once again refuses him and vows never to marry. Will she ever achieve the “brilliant career” that she aspires to? Readers are left to ponder the possibility for themselves, for the story is open-ended.

This description is from the St. Martin’s Press edition of My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin: Originally published in 1901, My Brilliant Career was written when Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin was only sixteen years old. But Miles Franklin was decades ahead of her time, and this book was written for an audience not yet born.

For the character of Sybilla Melvyn, Miles Franklin created someone who voices with incredible charm but deadly accuracy the fears, conflicts, and torments of every young woman coming of age in a man’s world. Red-haired, impetuous, sharp-tongued, Sybilla has ambitions that reach far beyond here small-town life in the Australian outback.

My Brilliant Career (1979 Film) based on the novel

Passionate in her attachments to a world of music and books — a world previously known only in imagination — Sybilla suddenly finds herself in her grandmother’s genteel home, Caddagat. And there, amid often dreamed-of pleasures, she’s meets Harold Beecham, the only man who could ever tempt her with marriage.

Sybilla is a young woman who “being so very plain” knows that she is “not a valuable article in the marriage market,” but “despises the slavery which respectable marriage will bring.” She will never “perpetrate matrimony,” will never be a “participant in that “degradation” — this is astounding stuff from a sixteen-year-old in the outback in 1895.

My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin on Amazon

And yet Sybilla knows the value of love between a man and a woman: “our greatest treasure is a knowledge that there is in creation an individual to whom our existence is necessary — someone who is part of our life as we are part of theirs, someone in whose life we feel assured our death would leave a gap for a day or two. And who can this be but a husband or wife?”

Miles Franklin absorbed and shared the intense nationalism and socialism of her male contemporary mentors, but she revolted then and forever against the role of women in their scheme of things, agains the “dullness and tame hennishness” of their lives. My Brilliant Career presents one of the most encouraging heroines in fiction, because Sybilla knows what her problems are. One can hardly restrain oneself from leaping back in time to tell Miles Franklin, “Sybilla is me.”

More about My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

1979 film version of My Brilliant Career

Review in The Guardian

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin (1901) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life.