Nava Atlas's Blog, page 91

March 1, 2018

Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks (June 7, 1917 – December 3, 2000) was an American poet whose works included sonnets and ballads as well as blues rhythm in free verse. She also created lyrical poems, some of which were book-length. Though her work reflected urban African-American life, its underlying themes were universal to the human experience. Brooks’ lifetime output encompassed more than twenty books, including children’s books.

Brooks was born in Topeka, Kansas; her family moved to Chicago during the period known as the Great Migration, when African-Americans moved in great numbers to Northern cities. She started writing and reading classic authors and poets when she was young. Her first poem was published in a children’s magazine when she was 13 years old. Having been expelled from several schools merely because she was African-American, these experiences informed her views on race, and eventually influenced her work as a writer.

The Chicago Defender

As a young adult, Brooks worked as a secretary while trying to get her work published. Some of her first poems were published in the legendary African-American newspaper, The Chicago Defender. She also participated in poetry workshops, which helped her writing career get off the ground.

Major works, and a Pulitzer Prize

In 1945 broke into book publishing with the well-received A Street In Bronzeville, referring to an area in the Chicago’s South Side. This collection led to her winning a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Annie Allen (1949) earned a Pulitzer Prize in 1950, making her the first African-American to win this award. The book follows the life of Annie, an African-American girl, from birth to womanhood. The poems reflect on the violence and racism that are part of Annie’s milieu, yet end with her hopes for a better world than the one she has inhabited. Like some of Brooks’ other books, this one isn’t easy to find.

The Bean Eaters (1960) was another well-received collection of poems. Critics such as the one who wrote this review noted her ability to tap into both specific and universal experiences: “Her poems are clear, not because they are childishly simple but because they strike at the thought and feelings common to mature people.”

In the Mecca (1968) refers to an 1891 apartment building in the Chicago’s South Side, a fortress-like structure that deteriorated into a slum. The first half of the book is a long poem about this environment, the second half consists of individual poems, the best known of which are “Malcolm X” and “Boy Breaking Glass.” It was nominated for the National Book Award for Poetry.

Maud Martha (1951) was Brooks’ only novel. It wasn’t widely read when first published, but has gained respect over the years as a story that speaks to the challenges and joys in a mid-century black woman’s life, centering on universal themes.

See also: Gwendolyn Brooks Quotes on Writing and Life

Poet Laureate of Illinois and other awards

In 1968, Brooks was named Poet Laureate for the state of Illinois. From 1985 to 1986 she was Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. Her work continued to be recognized for its excellence with prestigious awards, including those from the American Academy of Arts and Letters award, the Frost Medal, National Endowment for the Arts, The Shelley Memorial Award, and others.

A teaching career

Gwendolyn Brooks taught as part of her career, leading classes at Columbia College in Chicago, Northeastern Illinois University, Columbia University, and the University of Wisconsin. When she became a professor of English at Chicago State University in 1990, she the position until her death in 2000.

A writing mother

Throughout her career in the writing field, Gwendolyn Brooks maintained a family life, with a husband (whom she married in 1939) and their two children. When she was awarded the Pulitzer prize in 1950, Brooks already had a young son, Hank, and about a year and a half later her daughter Nora was born.

In the 2017 biography of Gwendolyn Brooks, A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun, author Angela Jackson tells of the challenges the poet faced as a writer and mother. Shortly after Nora was born, for example, Brooks was supposed to travel to receive an award, but could’t find a babysitter for the children. Nora later recollected that her mother limited travels until she and her brother were a little older. According to Jackson:

“This is not to say she did not struggle between motherhood and writing. In December, 1951, when Hank was eleven and Nora a three-month-old infant, Gwendolyn confided in a letter to Langston Hughes that her duties and responsibilities as a mother were so overwhelming that she felt she was without time ‘to call my soul my own.’ She barely had a moment for herself, much less to write.”

Read more about how Brooks negotiated the balance between family life and writing in Gwendolyn Brooks: The Poet as Working Mother.

Legacy

Gwendolyn Brooks used her poetic voice to spread tolerance and understanding the black experience in America. A prolific writer, she produced hundreds of poems, had twenty books published, and was recognized and honored with multiple prestigious awards during her lifetime. Yet despite her standing as a great American poet, many of her books are not easy to come by. It’s our hope that a wise publisher will change that, so that she can be more readily studied and appreciated. Gwendolyn Brooks died of cancer at the age of 83, in 2000.

You might also like:

6 Classic African-American Authors You Should Know More About

Quotes on Writing and Life

5 Things to Love About Gwendolyn Brooks

The Poet as Working Mother

Poetic Quotes from Maud Martha

Major Works (selected)

A Street in Bronzeville (1945)

Annie Allen (1949)

Maud Martha (1951)

Bronzeville Boys and Girls (1956)

The Bean Eaters (1960)

Selected Poems (1963)

In the Mecca (1968)

Riot (1969)

Primer for Blacks (1980)

Young Poet’s Primer (1980)

To Disembark (1981)

The Near-Johannesburg Boy and Other Poems (1986)

Blacks (1987)

Winnie (1988)

Children Coming Home (1991)

Autobiographies, Biographies, and Literary Criticism

A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun by Angela Jackson

Conversations with Gwendolyn Brooks – Edited by Gloria Wade Gayles

The World of Gwendolyn Brooks

Report From Part One: An Autobiography

A Life of Gwendolyn Brooks by George Kent

On Gwendolyn Brooks: Reliant Contemplation by Stephen Caldwell Write

The Poetry of Gwendolyn Brooks – an Analysis by David Wheeler

Maud Martha: A Critical Collection by Bryant and Blakely

Gwendolyn Brooks with her husband and son, Milwaukee, 1945

More Information

Wikipedia

Library of Congress Online Resources

The Poetry Foundation

Modern American Poetry: Gwendolyn Brooks

Her books on Amazon

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Articles, News, Etc.

Confronting the Warpland

Poetry Foundation: From the Archive

The Roads Taken

Sweet Bombs

Visit

Gwendolyn Brooks Grave – Lincoln Cemetery, Blue Island, IL

Gwendolyn Brooks Cultural Center – Western Illinois University, Macomb, IL

Gwendolyn Brooks Center – Chicago State University, Chicago, IL

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Gwendolyn Brooks appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 28, 2018

10 Poems by Georgia Douglas Johnson

Though she was considered an important member of the Harlem Renaissance, Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880 – 1966) wasn’t a New York City resident during the movement. Instead, she and her family lived in Washington, D.C. Their house on S Street NW came to be known as the “S Street Salon” — a kind of satellite for writers of the Harlem Renaissance while visiting the nation’s (very segregated) capital.

Among her colleagues were many of the leading lights and fellow poets of the Renaissance: Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, Alain Locke, and many of the noted women writers of the Harlem Renaissance. She hosted them and many others at her family’s Washington, D.C. home.

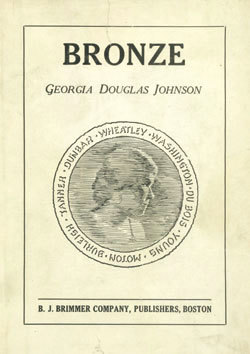

Georgia’s first poems were published in the NAACP’s magazineThe Crisis. in 1916. She published four poetry collections: The Heart of a Woman (1918), Bronze (1922), An Autumn Love Cycle (1928), and after a long gap, Share My World (1962). As a mixed-race woman, her poems addressed issues of bias and prejudice. She also wrote many that were intensely personal. The constraining roles of devoted wife and mother clashing with the desire to be a creative artist were explored in her poetry.

Jessie Redmon Fauset, an important editor of the era and a poet in her own right helped Georgia select the works for The Heart of a Woman collection. The Heart of a Woman was indeed the influence for Maya Angelou‘s memoir of the same title. In addition to poetry, Georgia wrote nearly thirty plays. Though some of her work was destroyed around the time of her death, there was a large enough body left to prove her talent and standing as an important member of the Harlem Renaissance. Here are 10 poems by Georgia Douglas Johnson, who deserves to be read and studied.

The Heart of a Woman

The heart of a woman goes forth with the dawn,

As a lone bird, soft winging, so restlessly on,

Afar o’er life’s turrets and vales does it roam

In the wake of those echoes the heart calls home.

The heart of a woman falls back with the night,

And enters some alien cage in its plight,

And tries to forget it has dreamed of the stars

While it breaks, breaks, breaks on the sheltering bars.

Common Dust

And who shall separate the dust

What later we shall be:

Whose keen discerning eye will scan

And solve the mystery?

The high, the low, the rich, the poor,

The black, the white, the red,

And all the chromatique between,

Of whom shall it be said:

Here lies the dust of Africa;

Here are the sons of Rome;

Here lies the one unlabelled,

The world at large his home!

Can one then separate the dust?

Will mankind lie apart,

When life has settled back again

The same as from the start?

I Want to Die While You Love Me

I want to die while you love me,

While yet you hold me fair,

While laughter lies upon my lips

And lights are in my hair.

I want to die while you love me,

And bear to that still bed,

Your kisses turbulent, unspent

To warm me when I’m dead.

I want to die while you love me

Oh, who would care to live

Till love has nothing more to ask

And nothing more to give!

I want to die while you love me

And never, never see

The glory of this perfect day

Grow dim or cease to be.

Your World

Your world is as big as you make it.

I know, for I used to abide

In the narrowest nest in a corner,

My wings pressing close to my side.

But I sighted the distant horizon

Where the skyline encircled the sea

And I throbbed with a burning desire

To travel this immensity.

I battered the cordons around me

And cradled my wings on the breeze,

Then soared to the uttermost reaches

With rapture, with power, with ease!

You might also enjoy

Renaissance Women: 12 Female Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

Prejudice

These fell miasmic rings of mist, with ghoulish menace bound,

Like noose-horizons tightening my little world around,

They still the soaring will to wing, to dance, to speed away,

And fling the soul insurgent back into its shell of clay:

Beneath incrusted silences, a seething Etna lies,

The fire of whose furnaces may sleep — but never dies!

Credo

I believe in the ultimate justice of Fate;

That the races of men front the sun in their turn;

That each soul holds the title to infinite wealth

In fee to the will as it masters itself;

That the heart of humanity sounds the same tone

In impious jungle, or sky-kneeling fane.

I believe that the key to the life-mystery

Lies deeper than reason and further than death.

I believe that the rhythmical conscience within

Is guidance enough for the conduct of men.

Hope

Frail children of sorrow, dethroned by a hue,

The shadows are flecked by the rose sifting through,

The world has its motion, all things pass away;

No night is omnipotent, there must be day!

The oak tarries long in the depths of the seed

But swift is the season of nettle and weed,

Abide yet awhile in the mellowing shade

And rise with the hour for which you were made.

The cycle of seasons, the tidals of man,

Revolve in the orb of the infinite plan;

We move to the rhythm of ages long done,

And each has his hour — to dwell in the sun!

Interracial

Let’s build bridges here and there

Or sometimes, just a spiral stair

That we may come somewhat abreast

And sense what cannot be exprest,

And by these measures can be found

A meeting place—a common ground

Nearer the reaches of the heart

Where truth revealed, stands clear, apart;

With understanding come to know

What laughing lips will never show:

How tears and torturing distress

May masquerade as happiness:

Then you will know when my heart’s aching

And I when yours is slowly breaking.

Commune—The altars will reveal . . .

We then shall be impulsed to kneel

And send a prayer upon its way

For those who wear the thorns today.

Oh, let’s build bridges everywhere

And span the gulf of challenge there.

Little Son

The very acme of my woe,

The pivot of my pride,

My consolation, and my hope

Deferred, but not denied.

The substance of my every dream,

The riddle of my plight,

The very world epitomized

In turmoil and delight.

Black Woman

Don’t knock at the door, little child,

I cannot let you in,

You know not what a world this is

Of cruelty and sin.

Wait in the still eternity

Until I come to you,

The world is cruel, cruel, child,

I cannot let you in!

Don’t knock at my heart, little one,

I cannot bear the pain

Of turning deaf-ear to your call

Time and time again!

You do not know the monster men

Inhabiting the earth,

Be still, be still, my precious child,

I must not give you birth!

The post 10 Poems by Georgia Douglas Johnson appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

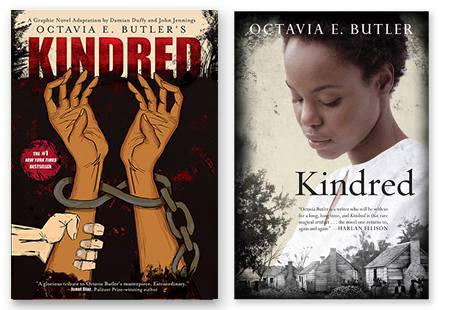

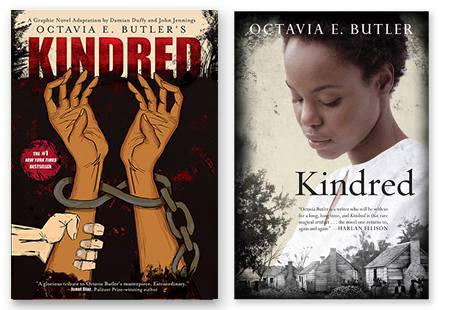

12 Fast Facts About Octavia Butler

Octavia Estelle Butler (1947 – 2006) was a pioneering African-American female author of science fiction at a time when the genre was male-dominated. Best known for her novel Kindred and the Patternist series, Butler developed her determination to become a writer at an early age . She was drawn to science fiction magazines like Amazing Stories, whose contents inspired unlimited possibilities and endless imagination. Here are some lesser-known facts about Octavia Butler:

Supported herself with odd jobs, including potato chip inspector

Butler would wake at 2 a.m. to write before going to work as a potato chip inspector. She credits many of her odd jobs with providing interesting details for her writing.

Kindred was inspired by her mother

Kindred follows the story of a writer who travels back in time to the antebellum south and meets her ancestors, a white plantation owner and a black slave.

Butler’s own mother was a housemaid, and many of Butler’s earliest memories were of the degradations her mother endured as a domestic. “I got to see her not hearing insults and going in back doors, and even though I was a little kid, I realized it was humiliating,” Butler said in an interview.

Never drove a car

In part due to her dyslexia, Butler never drove and remained a loyal public transportation user.

Awarded a MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship

She was the first science fiction author to be awarded this grant, female to boot!

Was 6 feet tall by the age of 15

Her height contributed to much of Butler’s shyness and reservation.

You might also enjoy: Octavia Butler Quotes on Writing and Human Nature

Raised by women

Butler’s father died when she was an infant, and was raised by her mother and maternal grandmother.

Her childhood nickname was “Junie”

Sharing the same name as her mother, she was referred to as “Junior” which later was shortened to “Junie.”

Moved to Seattle with 300 boxes of books

After her mother’s death, Butler relocated to Lake Forest Park, Washington in 1999. She brought with her 300 boxes of books. They were part of her growing collection that she was gifted by her mother, who brought home the tattered copies from the homes she cleaned.

Friends with Samual R. Delany

At the age of 23, Butler attended the Clarion Science Fiction Workshop where she met and became lifelong friends with fellow sci-fi author Samuel R. Delany.

Knew her own destiny by age 9

After watching the 1945 movie Devil Girl From Mars on television, it hit her. She thought to herself, “I can write a better story than that,” and eventually, she did.

See also: Octavia Butler’s Best Advice For Beginning Writers

A wanderlust spirit

Butler traveled extensively, including to Peru and hiking Huayna Picchu, the tallest mountain peak in Machu Picchu.

Unconfirmed cause of death

On February 24, 2006, Octavia E. Butler died in her Seattle home at the young age of 58. It’s been noted that she battled with a variety of health issues, such as severe hypertension, but the actual cause of death was never clarified.

More information:

Octavia E. Butler website

Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through this review, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 12 Fast Facts About Octavia Butler appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Fast Facts About Octavia Butler

Octavia Estelle Butler (1947 – 2006) was a pioneering African-American female author of science fiction at a time when the genre was male-dominated. Best known for her novel Kindred and the Patternist series, Butler developed her determination to become a writer at an early age . She was drawn to science fiction magazines like Amazing Stories, whose contents inspired unlimited possibilities and endless imagination. Here are some lesser-known facts about Octavia Butler:

Supported herself with odd jobs, including potato chip inspector

Butler would wake at 2 a.m. to write before going to work as a potato chip inspector. She credits many of her odd jobs with providing interesting details for her writing.

Kindred was inspired by her mother

Kindred follows the story of a writer who travels back in time to the antebellum south and meets her ancestors, a white plantation owner and a black slave.

Butler’s own mother was a housemaid, and many of Butler’s earliest memories were of the degradations her mother endured as a domestic. “I got to see her not hearing insults and going in back doors, and even though I was a little kid, I realized it was humiliating,” Butler said in an interview.

Never drove a car

In part due to her dyslexia, Butler never drove and remained a loyal public transportation user.

A line of jewelry was inspired after her work

Rachel Stewart created a line of necklaces called “Kindred” and “Wild Seed”, and earrings called “Lillith’s Brood” all inspired by characters in Butler’s works.

You might also enjoy: Octavia Butler Quotes on Writing and Human Nature

Raised by women

Butler’s father died when she was an infant, and was raised by her mother and maternal grandmother.

Her childhood nickname was “Junie”

Sharing the same name as her mother, she was referred to as “Junior” which later was shortened to “Junie.”

Moved to Seattle with 300 boxes of books

After her mother’s death, Butler relocated to Lake Forest Park, Washington in 1999. She brought with her 300 boxes of books. They were part of her growing collection that she was gifted by her mother, who brought home the tattered copies from the homes she cleaned.

Friends with Samual R. Delany

At the age of 23, Butler attended the Clarion Science Fiction Workshop where she met and became lifelong friends with fellow sci-fi author Samuel R. Delany.

Knew her own destiny by age 9

After watching the 1945 movie Devil Girl From Mars on television, it hit her. She thought to herself, “I can write a better story than that,” and eventually, she did.

See also: Octavia Butler’s Best Advice For Beginning Writers

A wanderlust spirit

Butler traveled extensively, including to Peru and hiking Huayna Picchu, the tallest mountain peak in Machu Picchu.

Unconfirmed cause of death

On February 24, 2006, Octavia E. Butler died in her Seattle home at the young age of 58. It’s been noted that she battled with a variety of health issues, such as severe hypertension, but the actual cause of death was never clarified.

She also…

Was 6 feet tall by the age of 15

Was the first science fiction author to be awarded a MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship

More information:

Octavia E. Butler website

Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through this review, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Fast Facts About Octavia Butler appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 27, 2018

Classic Quotes from Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott (1832 – 1888) is best known as the author of Little Women and its sequels, including Jo’s Boys and Little Men, though the scope of her work goes far beyond these beloved books. She is also known for promoting women’s rights and campaigning for women’s suffrage. Here are quotes from Little Women that remind us why we keep returning to the classic novel, time and again:

“I am not afraid of storms, for I am learning how to sail my ship.”

“I’ve got the key to my castle in the air, but whether I can unlock the door remains to be seen.”

“Love is a great beautifier.”

“My child, the troubles and temptations of your life are beginning, and may be many; but you can overcome and outlive them all if you learn to feel the strength and tenderness of your Heavenly Father as you do that of your earthly one. The more you love and trust Him, the nearer you will feel to Him, and the less you will depend on human power and wisdom. His love and care never tire or change, can never be taken from you, but may become the source of lifelong peace, happiness, and strength. Believe this heartily, and go to God with all your little cares, and hopes, and sins, and sorrows, as freely and confidingly as you come to your mother.”

You might also like: Louisa May Alcott’s Civil War Journals

“Watch and pray, dear, never get tired of trying, and never think it is impossible to conquer your fault.”

“…for love casts out fear, and gratitude can conquer pride.”

I want to do something splendid…something heroic or wonderful that won’t be forgotten after I’m dead. I don’t know what, but I’m on the watch for it and mean to astonish you all someday.”

“Be comforted, dear soul! There is always light behind the clouds.”

“I’ve got the key to my castle in the air, but whether I can unlock the door remains to be seen”

“I’d rather take coffee than compliments right now.”

“I want to do something splendid… Something heroic or wonderful that won’t be forgotten after I’m dead… I think I shall write books.”

See also: How Louisa May Alcott Came To Write Little Women

“The power of finding beauty in the humblest things makes home happy and life lovely.”

“Don’t try and make me grow up before my time … ”

“I find it poor logic to say that because women are good, women should vote. Men do not vote because they are good; they vote because they are male, and women should vote, not because we are angels and men are animals, but because we are human beings and citizens of this country.”

See Little Women by Louisa May Alcott on Amazon

You might also enjoy:

Wisdom From Louisa May Alcott

Illustrations for Little Women

10 Writers Who Were Inspired by Jo March

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Classic Quotes from Little Women by Louisa May Alcott appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 26, 2018

12 Classic Feminist Authors to Discover or Rediscover

While this is by no means an exhaustive list of classic feminist authors, it’s easy to argue that these women writers (who are no longer with us) were all visionaries in their unique ways. Fortunately, many more women writing today weave their feminist views into their fiction and nonfiction works. It’s safe to say that they stand on the shoulders of those presented here in order of birth from George Sand through Octavia Butler. Are there any others you would have included in this list? Who are today’s leading feminist authors?

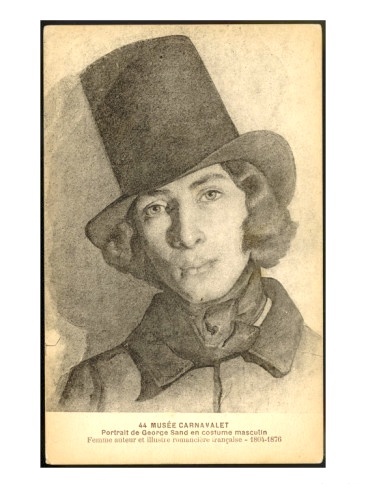

George Sand (Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin; 1804 – 1876), the prolific French author, started her own newspaper right around the time of the French revolution of 1848 to disseminate her progressive and socialist views. Women had no legal rights at the time, and she felt strongly that no society could advance under those circumstances.

George Sand enjoyed dressing in men’s clothing, smoking in public, traveling alone, and having lots of lovers — all things that were frowned upon for women of her time. though she had plenty of critics, she gave them as good as she got, and in the end, had legions of admirers. Though her books aren’t widely read in English translation, it’s worth getting to know her for the fearless way she lived, loved, and wrote.

Louisa May Alcott (1832 – 1888) promoted women’s rights and campaigned for women’s suffrage when she wasn’t at her writing desk. She believed in her right to write and to make money from her profession. Her views were espoused by her lead characters, strong young women who wanted more from life than to get married and have babies. “Nothing is impossible to a determined woman,” was a line from one of her novels, but also a view she firmly held.

Though the fictional Jo March did disappoint a bit by marrying conventionally and running a school, her ambition to be a writer inspired a number of real-life women writers. Read more about how Louisa May Alcott’s feminism explains her timelessness.

Kate Chopin (1850 – 1904) was an American author who was nearly forgotten upon her death, but is now admired as one of the foremothers of 20th century feminist literature. In her fiction, she focused on women’s struggles to forge an identity of their own, especially within the rigid constraints of Southern culture.

The Awakening, her 1899 novella and best known work, came under attack when it was published and was widely banned from bookstores and libraries. It was later rediscovered and has taken a prominent place in the canon of American feminist literature.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860 – 1935) was an American author of fiction and nonfiction, praised for her feminist works that pushed for equal treatment of and respect for women. Her semi-autobiographical novella (or long short story) The Yellow Wallpaper, tells of a woman who, in a depressive state, is banned from any creative activity. This drives her to near madness.

Gilman’s trilogy of utopian feminist novels starting with Herland, as well as her treatise on Women and Economics were ahead of their time. In 1994 she was welcomed into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and named one of the most influential women of the twentieth century.

Miles Franklin (1879 – 1954) was an Australian novelist and feminist activist. My Brilliant Career (1901), her best known work, was also her first novel, telling the story of a teenage girl growing up in Australia eager to break free as her own person. Franklin herself was a teenager when she wrote this insightful and delightfully rebellious book, which sealed her reputation. The lead character, Sybilla, observes: “It came home to me as a great blow that it was only men who could take the world by its ears and conquer their fate, while women, metaphorically speaking, were forced to sit with tied hands and patiently suffer as the waves of fate tossed them hither and thither, battering and bruising without mercy.”

In 1906, she moved to the U.S. to work with the National Women’s Trade Union League of America, and continued to be active in social causes after returning to her native land.

Virginia Woolf (1882 – 1941 ) believed in the right and agency of women to write and be heard. Though not many her novels may be considered feminist per se — they formed more of an interior, experimental body of work — A Room of One’s Own is a classic feminist manifesto.

She urged women to let their voices be heard as writers, and reminded us that we who writer are both inheritors and originators. “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction” might be her most famous quote, but she also reminded us that “The extraordinary woman depends on the ordinary woman …”

Pearl S. Buck (1892 – 1973), was a prolific American author of fiction and nonfiction. Her novels, whether set in China or the U.S., offered subtle examinations of women’s roles. As humanitarian and human rights advocate, she brought attention to issues of gender, politics, and race.

In an era when it was drilled into girls that a woman’s place was in the home, she wrote: “An intelligent, energetic, educated woman cannot be kept in four walls — even satin-lined, diamond-studded walls — without discovering sooner or later that they are still a prison cell.” Feminist themes are often woven into her novels. A personal favorite is Pavilion of Women, in which Madame Wu compels her husband to take a concubine so that she can live a live of the mind and spirit.

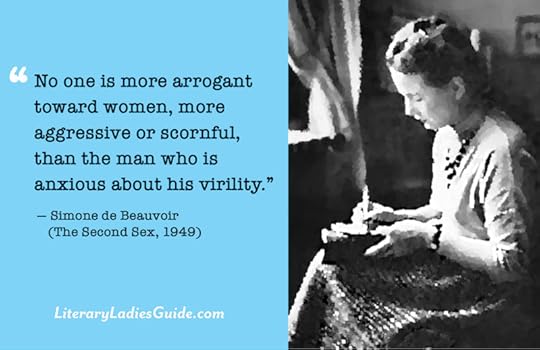

Simone de Beauvoir (1908 – 1986) was a French author, existential philosopher, political activist, feminist, and social theorist. Her most enduring work is The Second Sex, published in 1949. It’s still read and studied to this day as an essential manifesto on women’s oppression and liberation. Filled with ideas deemed radical at the time, the book established her an intellectual force and inspired a generation of women to question the status quo, and better yet, to change it.

This quote from The Second Sex is still sadly pertinent in the time of the #MeToo movement: “No one is more arrogant toward women, more aggressive or scornful, than the man who is anxious about his virility.”

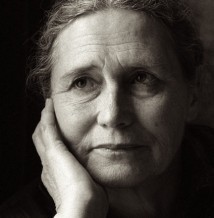

Doris Lessing (1919 – 2013) married and had children young and felt trapped in her role. It was writing that set her free.The Golden Notebook (1962) was her breakthrough novel, earned much attention among second-wave feminists. She later became something of an icon in the feminist movement, and the book is considered a “feminist bible.” She experimented with other forms of fiction, including science fiction, and for her body of work, won a 2007 Nobel Prize.

She didn’t mince words, even when speaking of and to women; this quote from The Golden Notebook is a case in point: “Sometimes I dislike women, I dislike us all, because of our capacity for not-thinking when it suits us; we choose not to think when we are reaching our for happiness.” Lessing used her platform to speak out on political issues important to her; she was particularly outspoken against apartheid in South Africa.

Adrienne Rich (1929 – 2012), the American poet, had a long career as a literary leader whose work articulated the ideas of the second wave feminist movement. Her poetry, according to this post by Sarah Wyman, envisions an alternative to a patriarchal system in which men control the avenues of power and the definitions of female existence.

Further, Wyman notes, “Rich refuses any division between the artistic and political aspects of her poetry as she uses both to explore social relations in a world hostile to female identity and creativity.” There’s lots more insight on Rich’s contributions to feminist literature in Wyman’s analysis of Dream of a Common Language by Adrienne Rich.

Audre Lorde (1934 – 1992) was a self-identified “black lesbian, mother, warrior, poet.” As society progressed with the anti-war, feminist and civil rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s, she moved into increasingly political themes with her poetry, speeches, and essays. Lorde used her platform as a writer, teacher, and speaker to spread ideas and experiences about the intersecting oppressions faced by many people.

As Lorde battled breast cancer, she wrote a feminist analysis of her experience with the disease and a mastectomy. For a sampling of her views, see Ten Thought-Provoking Quotes from Sister Outsider.

Octavia Butler (1947 – 2006) broke barriers as an African-American woman in the white male-dominated genre of science fiction. A self-described feminist, her novels feature strong female leads who are often the ones leading the charge to save humanity from itself. The MacArthur award winner was described by the New York Times as a writer “whose evocative, often troubling novels explore far-reaching issues of race, sex, power, and ultimately, what it meant to be human.”

Even if you’re not generally a sci-fi reader, you’d do well to read Kindred, which is more speculative than sci-fi, and the eerily prescient dystopian duo Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents.

The post 12 Classic Feminist Authors to Discover or Rediscover appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Quotes from Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

Daphne du Maurier (1907 – 1989) was a British novelist, playwright, and short story writer. As the author of romantic suspense thrillers, she’s arguably best known for Rebecca (1938), though Jamaica Inn, My Cousin Rachel, and the short story “The Birds” (which inspired the terrifying 1963 film are close contenders. For Rebecca, du Maurier drew upon on her experience with her own husband, who couldn’t let go of his departed wife. Rebecca was an instant best-seller, and the basis of the classic 1940 film of the same title. Here are some standout quotes from Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier:

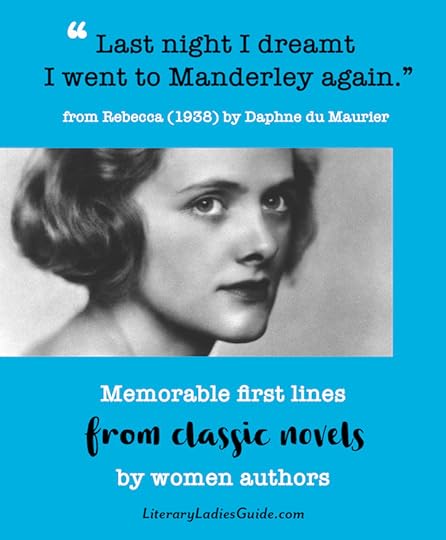

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.”

“If only there could be an invention that bottled up a memory, like scent. And it never faded, and it never got stale. And then, when one wanted it, the bottle could be uncorked, and it would be like living the moment all over again.”

“Happiness is not a possession to be prized, it is a quality of thought, a state of mind.”

“I am glad it cannot happen twice, the fever of first love. For it is a fever, and a burden, too, whatever the poets may say.

“Men are simpler than you imagine my sweet child. But what goes on in the twisted, tortuous minds of women would baffle anyone.”

“We can never go back again, that much is certain. The past is still close to us. The things we have tried to forget and put behind us would stir again, and that sense of fear, of furtive unrest, struggling at length to blind unreasoning panic – now mercifully stilled, thank God – might in some manner unforeseen become a living companion as it had before.”

See also: Daphne du Maurier Writing Habits and Styles

“I wondered why it was that places are so much lovelier when one is alone.”

“I believe there is a theory that men and women emerge finer and stronger after suffering, and that to advance in this or any world we must endure ordeal by fire.

“A dreamer, I walked enchanted, and nothing held me back.”

“Boredom is a pleasing antidote for fear.”

“When the leaves rustle, they sound very much like the stealthy movement of a woman in evening dress, and when they shiver suddenly, and fall, and scatter away along the ground, they might be the patter of a woman’s hurrying footsteps, and the mark in the gravel the imprint of a high-heeled shoe.”

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier on Amazon

“You have blotted out the past for me, far more effectively than all the bright lights of Monte Carlo.”

“Happiness is not a possession to be prized, it is a quality of thought, a state of mind of course we have on moments of depression; but there are other moments too, when time, unmeasured by the clock, runs on into eternity.”

“It seemed incredible to me now that I had never understood. I wondered how many people there were in the world who suffered, and continued to suffer, because they could not break out from their own web of shyness and reserve, and in their blindness and folly built up a great distorted wall in front of them that hid the truth. This was what I had done. I had built up false pictures in my mind and sat before them. I had never had the courage to demand the truth.”

“I glanced out of the window, and it was like turning the page of a photograph album. Those roof-tops and that sea were mine no more. They belonged to yesterday, to the past.”

“That was yesterday. Today we pass on, we see it no more, and we are different, changed in some infinitesimal way. We can never be quite the same again.”

“Boredom is a pleasing antidote to fear.”

You might also enjoy:

Memorable First Lines from Classic Novels by Women Authors

Explore more:

Daphne du Maurier obituary

Du Maurier’s Rebecca: A Worthy “Eyre” Apparent

Words of Wisdom and Quotes by Daphne du Maurier

Rebecca: A Review

The inspiration for Rebecca

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 23, 2018

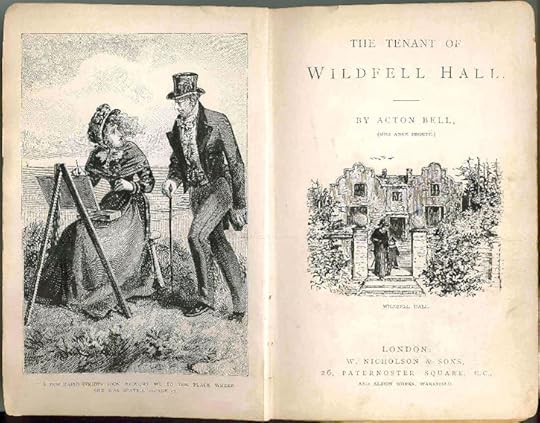

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë: A 19th-Century Introduction

This introduction to The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) by Anne Brontë is excerpted from Life and Works of the Sisters Brontë by Mary A. Ward, a 19th-century British novelist and literary critic.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, first published under Anne’s pseudonym Acton Bell, was an immediate success. It was considered shocking for its time, and in hindsight, one of the earliest feminist novels. It tells of the mysterious Helen Graham, and her arrival at Wildfell Hall with her young son and servant. Through a series of letters from another character, we learn of Helen’s troubled past. Shockingly, Charlotte prevented the republication of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall after Anne’s death, nearly causing its oblivion in literary history.

The following excerpt is abbreviated from Ward’s 1899 book about the Brontë. These passages don’t so much summarize or analyze the book but put Anne in the context of her family and the times in which she lived. It also discusses the effect that the troubling Brontë brother, Branwell, might have had on the sisters’ work:

Putting Anne in context

Anne Brontë serves a twofold purpose in the study of what the Brontës wrote and were. In the first place, her gentle and delicate presence, her sad, short story, her hard life and early death, enter deeply into the poetry and tragedy that have always been entwined with the memory of the Brontës, as women and as writers; in the second, the books and poems that she wrote serve as matter of comparison by which to test the greatness of her two sisters. She is the measure of their genius — like them, yet not with them.

RELATED CONTENT

The Brontë Sisters’ Path to Publication

Without the Veil Between (a novel about Anne Brontë)

A wrong impression of Anne

Many years after Anne’s death her brother-in-law protested against a supposed portrait of her, as giving a totally wrong impression of the ‘dear, gentle Anne Brontë.” “Dear” and “gentle” indeed she seems to have been through life, the youngest and prettiest of the sisters, with a delicate complexion, a slender neck, and small, pleasant features.

Notwithstanding, she possessed in full the Brontë seriousness, the Brontë strength of will. When her father asked her at four years old what a little child like her wanted most, the tiny creature replied — if it were not a Brontë it would be incredible!— “Age and experience.”

Branwell’s mark on the sisters’ work

Much of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and all of Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall show Branwell’s mark, and there are many passages in Charlotte’s books also where those who know the history of the parsonage can hear the voice of those sharp moral repulsions, those dismal moral questionings, to which Branwell’s misconduct and ruin gave rise.

Their brother’s fate was an element in the genius of Emily and Charlotte which they were strong enough to assimilate, which may have done them some harm, and weakened in them certain delicate or sane perceptions, but was ultimately, by the strange alchemy of talent, far more profitable than hurtful, inasmuch as it troubled the waters of the soul, and brought them near to the more desperate realities of our “frail, fall’n humankind.”

But Anne was not strong enough, her gift was not vigorous enough, to enable her thus to transmute experience and grief. The probability is that when she left Thorpe Green in 1845 she was already suffering from that religious melancholy of which Charlotte discovered such piteous evidence among her papers after death. It did not much affect the writing of Agnes Grey, which was completed in 1846, and reflected the minor pains and discomforts of her teaching experience, but it combined with the spectacle of Branwell’s increasing moral and physical decay to produce that bitter mandate of conscience under which she wrote The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

See also: Quotes from Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

How gentle Anne could speak unpalatable truths

“Hers was naturally a sensitive, reserved, and dejected nature. She hated her work, but would pursue it. It was written as a warning,” — so said Charlotte when, in the pathetic Preface of 1850, she was endeavoring to explain to the public how a creature so gentle and so good as Acton Bell should have written such a book as The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

And in the second edition of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, which appeared in 1848, Anne Brontë herself justified her novel in a Preface. The little Preface is a curious document. It has the same determined didactic tone which pervades the book itself, the same narrowness of view, and inflation of expression, an inflation which is really due not to any personal egotism in the writer, but rather to that very gentleness and inexperience which must yet nerve itself under the stimulus of religion to its disagreeable and repulsive task.

… But at the same time she cannot promise to limit her ambition to the giving of innocent pleasure, or to the production of a perfect work of art: “Time and talent so spent I should consider wasted and misapplied.” God has given her unpalatable truths to speak, and she must speak them.

The measure of misconstruction and abuse, therefore, which her book brought upon her she bore, says her sister, “as it was her custom to bear whatever was unpleasant, with mild, steady patience. She was a very sincere and practical Christian, but the tinge of religious melancholy communicated a sad shade to her brief, blameless life.”

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall on Amazon

Nearly as successful as Charlotte’s Jane Eyre

In spite of misconstruction and abuse, however, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall seems to have attained more immediate success than anything else written by the sisters before 1848, except Jane Eyre. It went into a second edition within a very short time of its publication, and Messrs. Newby informed the American publishers with whom they were negotiating that it was the work of the same hand which had produced Jane Eyre, and superior to either Jane Eyre or Wuthering Heights!

It was, indeed, the sharp practice connected with this astonishing judgment which led to the sisters’ hurried journey to London in 1848 — the famous journey when the two little ladies in black revealed themselves to Mr. Smith, and proved to him that they were not one Currer Bell, but two Miss Brontës. It was Anne’s sole journey to London—her only contact with a world that was not Haworth, except that supplied by her school-life at Roehead and her two teaching engagements.

And there was and is a considerable narrative ability, a sheer moral energy in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall which would not be enough, indeed, to keep it alive if it were not the work of a Brontë, but still betray its kinship and source. The scenes of Huntingdon’s wickedness are less interesting but less improbable than the country-house scenes of Jane Eyre; the story of his death has many true and touching passages; the last love-scene is well, even in parts admirably, written.

Watch The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (mini-series) on Amazon

The mark of Branwell

But the book’s truth, so far as it is true, is scarcely the truth of imagination; it is rather the truth of a tract or a report. There can be little doubt that many of the pages are close transcripts from Branwell’s conduct and language — so far as Anne’s slighter personality enabled her to render her brother’s temperament, which was more akin to Emily’s than to her own.

The same material might have been used by Emily or Charlotte; Emily, as we know, did make use of it in Wuthering Heights; but only after it had passed through that ineffable transformation, that mysterious, incommunicable heightening which makes and gives rank in literature.

… It is not as the writer of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall but as the sister of Charlotte and Emily Brontë, that Anne Brontë escapes oblivion — as the frail “little one,” upon whom the other two lavished a tender and protecting care, who was a witness of Emily’s death, and herself, within a few minutes of her own farewell to life, bade Charlotte ‘take courage.’

More about The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

An Entire Mistake: The Suppression of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

Review on Smart Bitches Trashy Books

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë: A 19th-Century Introduction appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë: 19th-Century Introduction

This introduction to The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) by Anne Brontë is excerpted from Life and Works of the Sisters Brontë by Mary A. Ward, a 19th-century British novelist and literary critic.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, first published under Anne’s pseudonym Acton Bell, was an immediate success. It was considered shocking for its time, and in hindsight, one of the earliest feminist novels. It tells of the mysterious Helen Graham, and her arrival at Wildfell Hall with her young son and servant. Through a series of letters from another character, we learn of Helen’s troubled past. Shockingly, Charlotte prevented the republication of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall after Anne’s death, nearly causing its oblivion in literary history.

The following excerpt is abbreviated from Ward’s 1899 book about the Brontë. These passages don’t so much summarize or analyze the book but put Anne in the context of her family and the times in which she lived. It also discusses the effect that the troubling Brontë brother, Branwell, might have had on the sisters’ work:

Putting Anne in context

Anne Brontë serves a twofold purpose in the study of what the Brontës wrote and were. In the first place, her gentle and delicate presence, her sad, short story, her hard life and early death, enter deeply into the poetry and tragedy that have always been entwined with the memory of the Brontës, as women and as writers; in the second, the books and poems that she wrote serve as matter of comparison by which to test the greatness of her two sisters. She is the measure of their genius — like them, yet not with them.

You might also like:

The Brontë Sisters’ Path to Publication

A wrong impression of Anne

Many years after Anne’s death her brother-in-law protested against a supposed portrait of her, as giving a totally wrong impression of the ‘dear, gentle Anne Brontë.” “Dear” and “gentle” indeed she seems to have been through life, the youngest and prettiest of the sisters, with a delicate complexion, a slender neck, and small, pleasant features.

Notwithstanding, she possessed in full the Brontë seriousness, the Brontë strength of will. When her father asked her at four years old what a little child like her wanted most, the tiny creature replied — if it were not a Brontë it would be incredible!— “Age and experience.”

Branwell’s mark on the sisters’ work

Much of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and all of Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall show Branwell’s mark, and there are many passages in Charlotte’s books also where those who know the history of the parsonage can hear the voice of those sharp moral repulsions, those dismal moral questionings, to which Branwell’s misconduct and ruin gave rise.

Their brother’s fate was an element in the genius of Emily and Charlotte which they were strong enough to assimilate, which may have done them some harm, and weakened in them certain delicate or sane perceptions, but was ultimately, by the strange alchemy of talent, far more profitable than hurtful, inasmuch as it troubled the waters of the soul, and brought them near to the more desperate realities of our “frail, fall’n humankind.”

But Anne was not strong enough, her gift was not vigorous enough, to enable her thus to transmute experience and grief. The probability is that when she left Thorpe Green in 1845 she was already suffering from that religious melancholy of which Charlotte discovered such piteous evidence among her papers after death. It did not much affect the writing of Agnes Grey, which was completed in 1846, and reflected the minor pains and discomforts of her teaching experience, but it combined with the spectacle of Branwell’s increasing moral and physical decay to produce that bitter mandate of conscience under which she wrote The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

How gentle Anne could speak unpalatable truths

“Hers was naturally a sensitive, reserved, and dejected nature. She hated her work, but would pursue it. It was written as a warning,” — so said Charlotte when, in the pathetic Preface of 1850, she was endeavoring to explain to the public how a creature so gentle and so good as Acton Bell should have written such a book as The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

And in the second edition of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, which appeared in 1848, Anne Brontë herself justified her novel in a Preface. The little Preface is a curious document. It has the same determined didactic tone which pervades the book itself, the same narrowness of view, and inflation of expression, an inflation which is really due not to any personal egotism in the writer, but rather to that very gentleness and inexperience which must yet nerve itself under the stimulus of religion to its disagreeable and repulsive task.

… But at the same time she cannot promise to limit her ambition to the giving of innocent pleasure, or to the production of a perfect work of art: “Time and talent so spent I should consider wasted and misapplied.” God has given her unpalatable truths to speak, and she must speak them.

The measure of misconstruction and abuse, therefore, which her book brought upon her she bore, says her sister, “as it was her custom to bear whatever was unpleasant, with mild, steady patience. She was a very sincere and practical Christian, but the tinge of religious melancholy communicated a sad shade to her brief, blameless life.”

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall on Amazon

Nearly as successful as Charlotte’s Jane Eyre

In spite of misconstruction and abuse, however, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall seems to have attained more immediate success than anything else written by the sisters before 1848, except Jane Eyre. It went into a second edition within a very short time of its publication, and Messrs. Newby informed the American publishers with whom they were negotiating that it was the work of the same hand which had produced Jane Eyre, and superior to either Jane Eyre or Wuthering Heights!

It was, indeed, the sharp practice connected with this astonishing judgment which led to the sisters’ hurried journey to London in 1848 — the famous journey when the two little ladies in black revealed themselves to Mr. Smith, and proved to him that they were not one Currer Bell, but two Miss Brontës. It was Anne’s sole journey to London—her only contact with a world that was not Haworth, except that supplied by her school-life at Roehead and her two teaching engagements.

And there was and is a considerable narrative ability, a sheer moral energy in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall which would not be enough, indeed, to keep it alive if it were not the work of a Brontë, but still betray its kinship and source. The scenes of Huntingdon’s wickedness are less interesting but less improbable than the country-house scenes of Jane Eyre; the story of his death has many true and touching passages; the last love-scene is well, even in parts admirably, written.

Watch The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (mini-series) on Amazon

The mark of Branwell

But the book’s truth, so far as it is true, is scarcely the truth of imagination; it is rather the truth of a tract or a report. There can be little doubt that many of the pages are close transcripts from Branwell’s conduct and language — so far as Anne’s slighter personality enabled her to render her brother’s temperament, which was more akin to Emily’s than to her own.

The same material might have been used by Emily or Charlotte; Emily, as we know, did make use of it in Wuthering Heights; but only after it had passed through that ineffable transformation, that mysterious, incommunicable heightening which makes and gives rank in literature.

… It is not as the writer of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall but as the sister of Charlotte and Emily Brontë, that Anne Brontë escapes oblivion — as the frail “little one,” upon whom the other two lavished a tender and protecting care, who was a witness of Emily’s death, and herself, within a few minutes of her own farewell to life, bade Charlotte ‘take courage.’

More about The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

An Entire Mistake: The Suppression of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

Review on Smart Bitches Trashy Books

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë: 19th-Century Introduction appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 22, 2018

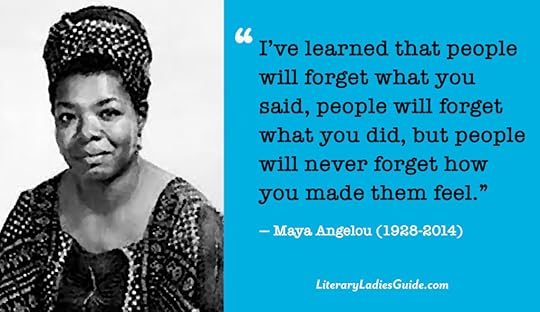

Maya Angelou Quotes To Live By

Maya Angelou (1928 – 2014) was an African-American writer, poet, civil rights activist, memoirist, and much more. She’s best known for I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings (1969), which was among a seven-part autobiographical series. She led a bold, inspiring, accomplished life, and was a true trailblazing woman to be remembered and honored. Here is a compilation of Maya Angelou quotes that we would all do well to live by:

“Try to be a rainbow in someone’s cloud.”

“Determine to live life with flair and laughter.”

“We need joy as we need air. We need love as we need water. We need each other as we need the earth we share.”

“If you have only one smile in you give it to the people you love.”

“We may encounter many defeats but we must not be defeated.”

“Love recognizes no barriers. It jumps hurdles, leaps fences, penetrates walls to arrive at its destination full of hope.”

“I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

“My mission in life is not merely to survive, but to thrive; and to do so with some passion, some compassion, some humor, and some style.”

“If you don’t like something, change it. If you can’t change it, change your attitude.”

“I can be changed by what happens to me. But I refuse to be reduced by it.”

“A wise woman wishes to be no one’s enemy; a wise woman refuses to be anyone’s victim.”

“If you’re always trying to be normal you will never know how amazing you can be.”

“The desire to reach the stars is ambitious. The desire to reach hearts is wise and most possible.”

You might also like: 10 Fascinating Facts About Maya Angelou

“Success is liking yourself, liking what you do, and liking how you do it.”

“Life is not measured by the number of breaths you take but by the moments that take your breath away.”

“I’ve learned that I still have a lot to learn.”

“You can’t use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

“Seek patience and passion in equal amounts. Patience alone will not build the temple. Passion alone will destroy its walls.”

“I’ve learned that making a living is not the same thing as making a life.”

“You did the best that you knew how. Now that you know better, you’ll do better.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Maya Angelou Quotes To Live By appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.