Nava Atlas's Blog, page 88

March 29, 2018

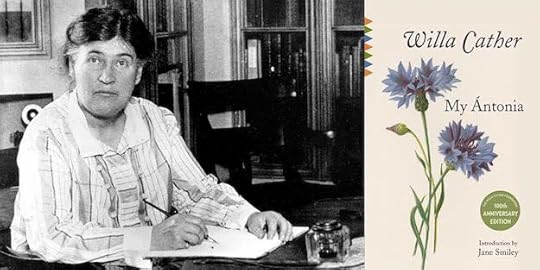

Willa Cather

Willa Silbert Cather (December 7, 1873 – April 24, 1947), author of classic American fiction, was born in Winchester, Virginia. At nine years of age, her family moved from the staid, conservative life of Virginia society to Red Cloud, Nebraska. Growing up among hardworking European immigrants who worked the land inspired some of her best-known works.

In this untamed landscape, young Willa Cather rode her pony about to get to know her foreign-born neighbors who were homesteading on the Great Plains. She observed their struggles to conquer an unforgiving land with its extremes of droughts, blizzards, storms, and prairie fires.

Though it would be some time before she turned her hand to fiction, her Norwegian, Swedish, and German neighbors were the basis of characters in her best known novels, including O Pioneers! and My Antonia. Cather’s respect for the immigrants’ devotion to the land is reflected in these stories and their characters.

Formative years

Willa graduated from Red Cloud High School in 1890, and went on to the University of Nebraska in Lincoln. Because she had spent time with the local doctor in Red Cloud, her intention was to study medicine. While pursuing her studies, she also edited the University’s magazine, and began reviewing plays in local papers.

Recognizing her talent for writing, her college classmates secretly submitted an essay she wrote to the Nebraska State Journal. Seeing her work in print promptly changed her plans: “Up to that time I had planned to specialize in medicine … But what youthful vanity can be unaffected by the sight of itself in print! It was a kind of hypnotic effect.”

In 1892, a short story titled “Peter” was published in a Boston publication. Similarly, without her knowledge, this story was submitted to The Mahogany Tree, a Boston-based literary magazine, by her English professor.

Like many authors before and since, Willa first worked as a journalist, starting with a position at the aforementioned Nebraska State Journal as she completed her college studies in the 1890s. Her first post-graduation position was on the editorial staff of McClure’s magazine in New York City, where she worked her way up to managing editor.

She credited the fast pace of newspaper and magazine production for helping to work off what she described as the “purple flurry” of her early writing attempts.

You might also like: Cather on the Art of Fiction

Productive years

Cather’s publishing debut came as a poet, with a collection titled April Highlights (1903). It remained her only volume of poetry.

The Troll Garden (1905), a collection of short stories, was Cather’s first published book of fiction, completed in her early days in New York City. After putting in six years as an editor, Alexander’s Bridge, her first novel, was published in 1912. After that, she devote her full efforts to writing fiction.

When New England author Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909) became Willa Cather’s mentor, she urged her to shed her fixation on writing like Henry James and instead mine memories of her youth in Red Cloud for inspiration. The prairies and immigrant families of Cather’s childhood home inspired the classics she’s best remembered for.

O Pioneers!, The Song of the Lark, and My Ántonia came in quick succession in the nineteen-teens. Several novels, all well received, came out in the twenties. One of Ours (1922) received a Pulitzer Prize the following year. Death Comes for the Archbishop, considered one of her finest, was published in 1927.

In these post WWI-years, Cather was distressed by the growth of materialism and the loss of the pioneering spirit of the country that had informed so many of her most successful works.

Her last novel, Sapphira and the Slave Girl (1940), was possibly her least well-reviewed novel, but it was the capstone of a truly stellar career in American letters.

Edith Lewis

Even as a child, Cather recognized her masculine aspect. She went through a phase of wearing her hair completely shorn, wearing boys’ clothing, and asking to be called “William.” As a teen, she often signed her name as “William Cather, Jr.”

She fell in love with a few young women in her youth, though she was never open about discussing her sexuality. A product of her time, she may have felt it could harm her career. To her credit, she didn’t marry a man just to keep up appearances.

Edith Lewis, like Cather, was an editor at McClure’s Magazine. The two women became life partners and lived together in New York City for 40 years. Lewis served as a personal editor to Cather. She outlived Cather by many years, and served as her literary executor. They are buried together in Jaffrey, New Hampshire.

See also: My Antonia by Willa Cather

An artist of distinction

Cather’s novels, known for their stark beauty and spare language, reflect her philosophy that writing is an art as well as a craft (and a skill) that can be honed and polished. She advised aspiring writers to spill out all their overwrought, adjective-laden prose, allowing clearer focus and language to come through in one’s writing. Cather’s considerable wisdom has been fully preserved, especially in the numerous interviews she granted — despite her professed disdain for the press and with fame in general.

Willa Cather died at age 73 of a cerebral hemorrhage in New York City, where she had lived for many years.

Willa Cather page on Amazon

More about Willa Cather on this site

Cather On the Art of Fiction

Review by Cather of Kate Chopin’s The Awakening

5 Pieces of Writing Wisdom from Willa Cather

Willa Cather Loved and Hated Fame & the Press

Dear Literary Ladies: How can I write, when I have so little time?

Dear Literary Ladies: How can I find my unique writing voice?

Major Works

The Troll Garden (1905)

Alexander’s Bridge (1912)

O Pioneers! (1913)

The Song of the Lark (1915)

My Ántonia (1918)

A Lost Lady (1923)

My Mortal Enemy (1926)

The Professor’s House (1925)

Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927)

Shadows on the Rock (1931)

Lucy Gayheart (1935)

Sapphira and the Slave Girl (1940)

Autobiographies and Biographies about Willa Cather

Willa Cather in Europe: Her Own Story of the First Journey

Willa Cather: A Literary Life by James Woodress

The World of Willa Cather by Mildred R. Bennett

Willa Cather Living: A Personal Record by Edith Lewis

More Information

Cather on Wikipedia

The Willa Cather Foundation

Willa Cather: A Longer Biographical Sketch

PBS Documentary on Willa Cather: The Road is All

Reader discussions of Willa Cather’s books on Goodreads

Read and listen online

Cather public domain works on Project Gutenberg

Audio recordings of Cather’s public domain works on Librivox

Film adaptations of Cather’s books

O Pioneers! (1992)

My Antonia (1995)

The Song of the Lark (2006)

Articles, News, Etc.

LGBT History: Famous Women Who Loved Women

A Lecture on Cather

Willa Cather vs. Scott Fitzgerald

January 2, 1896: Willa Cather to “Push”

Will Cather Was Skeptical of Analytics

Media Studies Experience: An Afternoon with Willa Cather

Willa Cather, Pioneer — an appreciation by Jane Smiley

Visit and research

Cather’s Childhood Home – Red Cloud, NE

Cather Homes and Places – Red Cloud, NE and Gore, VA

The Willa Cather Archive – University of Nebraska, Lincoln

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Willa Cather appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 28, 2018

Edith Wharton

Edith Wharton (January 24, 1862 – August 11, 1937), was born Edith Newbold Jones in New York City. One of the Grande Dames of American letters, everything about her, from her wealthy background to her stately demeanor suggests a woman in possession of herself. However, beneath the surface was a deep insecurity about her talent and abilities, one she gradually overcame in a substantial way.

Most of us have heard the expression “Keeping up with the Joneses.” But it might come as a surprise that this doesn’t refer to a hypothetical family, but Edith Wharton’s parents, George Frederic Jones and Lucretia Rhinelander Jones.

A privileged childhood

Born into the rarified late nineteenth-century world of wealth and privilege, her formative years consisted of riding, balls, coming-out parties, teas, and extended stays in Europe. When Edith was just four years old, she traveled throughout Europe with her parents, with stays in Spain, Germany, Italy, and France. Upon returning to New York, she was educated by private tutors.

Despite having homes in New York City and Newport, and the kind of money that gained them access to the finer things in life, culture and learning weren’t particularly valued by the Jones family. And though Edith lacked for nothing, it was a less-than-ideal upbringing for a bookish, dreamy girl.

Edith Wharton at around eight years of age; painting by Edward May Harrison, 1870

Writing wasn’t proper for a society girl

As a fledgling writer, she received out-and-out disapproval from those closest to her, including her mother and society friends, who thought that literary pursuits were beneath a person of her class. From society gadfly Edward “Teddy” Wharton, husband from her failed marriage, she received nothing but indifference.

Insecurity about her talent and abilities plagued her for years, and she admitted to suffering from terrible shyness.

You might also like: Edith Wharton’s Struggles with Self-Doubt

Tiptoeing into publishing

Like many authors, Edith started out by writing shorter pieces and poetry. Fast and Loose, a little-known novella, was published in 1877 when she was only fourteen; Verses, a collection of poems, was privately printed the following year. Her poems were first published nationally in Scribner’s Magazine, and in 1891, they published the first of many of her short stories.

She tiptoed into the publishing of books with The Decoration of Houses (1897). Another in this genre, Italian Villas and Their Gardens came a bit later (1904).

Her early literary reputation was built on small successes, as well as the welcome friendship and constructive critique of one who did believe in her talent, Walter Berry, a lifelong confident for whom she carried a torch (and whose grave in Paris is next to hers).

Wharton’s first collection of short stories was titled The Greater Inclination (1899). Its publication helped her to finally accept herself as a professional writer and not a dilettante. She vowed to turn away from the “distractions of a busy and sociable life, full of friends and travel and gardening for the discipline of the daily task.” As she wrote in her memoir, this is when she went from being “a drifting amateur in to a professional,” and most importantly, “gained what I lacked most—self confidence.”

The House of Mirth

Her first novel, The House of Mirth (1905), was an instant bestseller. Wharton exulted to her publisher Charles Scribner, “It is a very beautiful thought that 80,000 people should want to read The House of Mirth, and if the number should ascend to 100,000 I fear my pleasure would exceed the bounds of decency.”

How delighted she would be if the word reached her in the Great Beyond, that The House of Mirth is still in print, as is Ethan Frome, The Age of Innocence, The Custom of the Country, as well many of her other titles.

Teddy Wharton and The Mount

In April of 1885, Edith Jones married Edward “Teddy” Robbins Wharton in New York City. Some years later, she designed and built The Mount, an imposing mansion with extensive grounds in Lenox, MA. She lived there with Teddy Wharton from 1902 to 1911. Due to his drinking and struggles with mental illness, theirs was an unhappy marriage. Upon the couple’s divorce in 1913, Wharton moved to France.

Wharton fans will love visiting The Mount

A move to France and refugee relief work

Edith became deeply involved in refugee relief work during World War I. She wrote reports for American newspapers and organized the American Hostel for Refugees. Among her other accomplishments were employing skilled 90 women who had been thrown out of work; feeding and housing hundreds of child refugees from Belgium, establishing hostels for other refugees; and assisting wounded soldiers and struggling families.

For her war relief efforts, Wharton received one of France’s highest honors, the Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Belgium named her a Chevalier of the Order of Leopold.

Edith Wharton surrounded by World War I soldiers

Pulitzer Prize for The Age of Innocence, and later years

After the war, she continued her prodigious literary output and became part of a vaunted literary circle that included her close friend, Henry James.

The Pulitzer Prize for the Novel for fiction was awarded to Wharton for The Age of Innocence (1921), making her the first woman to achieve this distinction. Two years later she also became the first woman ever to receive an honorary doctorate (conferred upon her by Yale University). It was the last time she returned to the U.S.

Even at the height of her fame and literary prowess, Edith struggled with censorship. Ladies’ Home Journal criticized her story “The Day of the Funeral” as “too strong” for their readership. She once wrote:

“Brains & culture seem non-existent from one end of the social scale to the other, & half the morons yell for filth, & the other half continue to put pants on piano-legs.”

Her remaining years were spent in France, where she died from a stroke at the age of seventy five in 1937.

More about Edith Wharton on this site

Edith Wharton Needed Approval, Just Like the Rest of Us

Edith Wharton’s Struggles with Self-Doubt

Edith Wharton’s Reflections on Her Writing Life

Visiting The Mount — Edith Wharton’s Home in Lenox, MA

Dear Literary Ladies: How should I deal with reviews of my work?

Edith Wharton’s Introduction to Ethan Frome

Perceptive Quotes by Edith Wharton

4 Noted Women Authors as World War I Nurses and Relief Workers

Edith Wharton’s obituary

Major Works

Edith Wharton wrote some forty works of fiction, including and numerous novellas and short stories in addition to longer novels. These are her best known.

The Greater Inclination (1899)

The House of Mirth (1905)

Ethan Frome (1911)

The Reef (1912)

The Custom of the Country (1913)

The Age of Innocence (1920)

The Buccaneers (1938; posthumous)

Notable nonfiction

The Decoration of Houses (1897)

Italian Villas and Their Gardens (1904)

In Morocco (1920)

Autobiography and Biographies

A Backward Glance (1934) by Edith Wharton

Edith Wharton: A Biography by R.W.B. Lewis

Edith Wharton by Hermione Lee

The Brave Escape of Edith Wharton by Connie Nordhielm Wooldridge

More Information

Wikipedia

The Edith Wharton Society

Reader discussions of Wharton’s books on Goodreads

Articles, News, Etc.

What Would Edith Wharton Think of Our Modern Home Decor Tastes

A Visit to the Cemetery Where Edith Wharton Buried Her Beloved Dogs

12 Must-Read Collections of Famous Authors’ Letters

Handwritten Manuscript Pages From Classic Novels:

Edith Wharton’s manuscript from The House of Mirth

Virginia Woolf, Edith Wharton, and a Case of Anxiety of Influence

Read and listen online

Wharton’s public domain works on Project Gutenberg

Audio recordings of Wharton’s public domain works on Librivox

Selected film adaptations of Edith Wharton’s works

The Age of Innocence (1943)

The Age of Innocence (1993)

Ethan Frome (1993)

The House of Mirth (2000)

Visit and research

The Mount – Lenox, MA, USA

Edith Wharton Collection – Beineke Library at Yale University, New Haven, CT

Edith Wharton gravesite in Versailles, France

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Edith Wharton appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 27, 2018

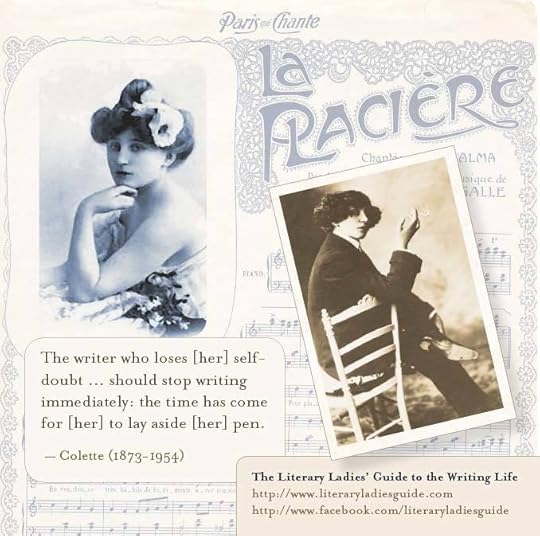

Colette (Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette)

Colette (January 28, 1873 – August 3, 1954) was a French author whose full original name was Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette. She was as known for her writing and performing as she was for her scandalous lifestyle. As a child, her mother Sido was her greatest inspiration, and allowed the young Colette to drink deeply from the well of life to gain courage and individuality.

Her stories of strong females were often based on her own experiences, and were more sexually explicit than most fiction of their time. Colette was a practicing journalist in the midst of her writing career.

Strong females and honest sexuality

In 1900, Colette began publishing the series of Claudine stories that defined the teenage girl of the era, exploring her sexual and mischievous sides. The problem: Her first husband, Willy, took the credit as well as the earnings for these popular stories.

Willy, whose real name was Henry Gauthier-Villars, was much older than herself. The marriage was a disaster — not only did he compelled her to write the Claudine stories, but then published them under his name. Claudine at School (1900) was the first of them efforts to be published, and was an immediate success. More Claudine books followed.

Freed from the nefarious Willy

Once she divorced the nefarious Willy, Colette published Retreat from Love (1907), her first solo novel. Once she broke free of her first husband, her sprit soared. Colette worked as a journalist and moonlighted as a music hall performer, all the while continuing to write fiction. This was also the period in which she conducted a series of affairs with women. All the while, she kept the lessons she gleaned from her complicated possessive mother — to be resilient and independent.

Short and Sweet Quotes by Colette

More marriages, and a child

Colette had her first and only child, a daughter, at age forty. The girl was named Colette, but acquired the odd nickname Bel-Gazou. It has been said that Colette was an abominable, neglectful mother.

She married her daughter’s father, Henry de Jouvenel, a journalist and politician, with whom she was mismatched. The marriage failed quickly, but not before she seduced her 16-year-old stepson. She was then 47. It wasn’t until she was in her early 50s that she met her match. What started as a heated affair with Maurice Goudeket, who much younger than herself, became a lasting, sweet relationship characterized by mutual devotion.

A prolific life of letters

Colette’s love life was passionate and volatile, but nothing stopped her from a voluminous writing output. In both ways, she followed the footsteps of her fellow Frenchwoman, George Sand, whom she admired. It was the vagaries of love, its joys, complications, heartaches, and sensual pleasures, that gave her a bounty of material to work with.

Gigi, perhaps her best-known works (which inspired a popular film), is a story of a French girl training to be a courtesan, but who falls in love with a wealthy gentleman. Its stage adaptation, created by her American friend Anita Loos, was greeted with critical acclaim with then unknown Audrey Hepburn playing the main character. It was also made into a popular 1985 film with Leslie Caron in the title role.

Other masterpieces, in addition to the aforementioned Claudine books, include Chéri (which inspired the 2009 film starring Michelle Pfeiffer), The Vagabond (the author’s personal favorite), The Ripening Seed, and Mitsou. Sido was an homage to her mother.

Colette page on Amazon

Later years

Colette conducted her life with no regrets, and disdained the restraint society had on female, expression. In her later years, Colette suffered from arthritis and rarely left her Paris apartment. In 1948, she was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Memoir became a favored literary form as she reflected on her life as she grew older.

To say that Colette was prolific is an understatement to describe her vast output of novels, plays, stories. Less known is that she also produced film and radio scripts and even an opera libretto (L’enfant et les sortilèges by Maurice Ravel).

Upon her death in 1954, Colette was one of the world’s most renowned women of letters and was given a state funeral, the first for a woman in France.

See also: The Vagabond by Colette, her favorite among her novels

More about Colette on this site

Short and Sweet Quotes by Colette

Major works

Colette was incredibly prolific; this list represents her most widely translated and read novels, though produced numerous other works of fiction and nonfiction.

The Claudine stories (1900-1904)

The Vagabond (1910)

Mitsou (1919)

Chéri (1920)

The Last of Chéri (1926)

Sido (1929)

The Other One (1931 translation of La Seconde, 1929)

The Pure and The Impure (1931)

Gigi (1944)

Biographies

Secrets of the Flesh: A Life of Colette by Judith Thurman (1999)

Earthly Paradise: An Autobiography (collected from Colette’s writings, 1975)

Colette: A Taste for Life by Yvonne Mitchell (1975)

More Information

Wikipedia

Obituary – The New York Times, 1954

Reader discussion of Colette’s books on Goodreads

Stage and film adaptations (selected)

Gigi (film, 1958)

Gigi (Broadway musical, 1973)

Duo (1990, French)

Cheri (film, 2009)

Visit Colette’s Home

Musée Colette – St.-Sauveur-en-Puisaye, Burgundy, France

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Colette (Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary

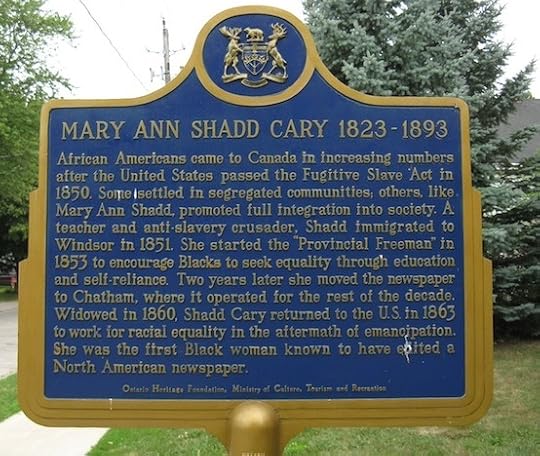

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (October 9, 1823 – 1893) was best known for launching a newspaper, The Provincial Freeman, while living in Windsor, Ontario in Canada, becoming the first woman publisher of any race or background in Canada, and the first African-American woman publisher in all of North America.

As editor and writer for the Freeman, she advocated for the black community in Canada and beyond, working tirelessly to break down the dual barriers of race and gender. She was also an active participant in the women’s suffrage movement in the U.S., and lectured widely on education and self-reliance. Later in life, she became an attorney.

The Shadd family’s journey

The oldest of thirteen siblings, Mary Ann, was inspired by her parents, A.D. and Harriet Shadd. Both parents were deeply involved with the cause of abolition, and her father wrote for the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator. The family’s home in Delaware was a stop on the Underground Railroad for escaped slaves make their way to Northern states and Canada.

In 1840, the Shadds moved their thirteen children from Delaware, where they’d always lived, to Pennsylvania. Delaware, a free state, made it illegal to educate African-American children, so there was no question of staying — education and abolition were the family’s guiding forces.

In Pennsylvania, Mary Ann attended one of the state’s many Quaker schools, and after training to be a teacher, opened a school for African-American children. Another jolt came when Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Now, not only were runaway slaves in greater peril than ever, but free Northern blacks could also be captured and forced into bondage.

The Provincial Freeman

Mary Ann and her brother Isaac fled to Windsor, Canada, just across the border from Detroit. Once settled in Windsor, Mary Ann started another school, this time with integrated classrooms. She also launched The Provincial Freeman. Isaac managed the newspaper’s business affairs, and Reverend Samuel Ringgold Ward, a fugitive slave, was her co-editor. Not long after, the rest of the Shadd family joined Mary Ann and Isaac in Windsor.

The Provincial Freeman was published from 1853 to1861, becoming one of North America’s rare black-owned newspapers. It promoted integration and equality, and featured news stories about culture, education, and politics — many of which Mary Ann wrote or edited.

As founder and co-editor of The Provincial Freeman, she once wrote of herself that she “broke editorial ice,” expressing her sense that she’d cracked a glass ceiling. The paper primarily served the 35,000 black residents of Ontario, but it was also read in many parts of the U.S., where educated blacks were eager to see their lives and views reflected in print. Mary Ann traveled back and forth from the U.S. often, gathering stories for the newspaper. She also lectured on self-reliance and education, and encouraged African-American families to emigrate to Canada.

During the years when she was running the newspaper, she married Thomas Cary, a Canadian widower with three children, and they had two more of their own. Sadly, her husband died in 1860, just a few years into the marriage.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary Statue at BME Freedom Park, Chatham, Ontario

Return to the U.S., becoming an attorney

After publishing what would become the paper’s last issue in 1861, Mary Ann returned to live in the U.S. As the Civil War was breaking out, she felt called to help in the war effort. As a recruiting officer for the Union Army, her mission was to encourage African-American men to enlist in the battle against the Confederacy for the fight to end slavery.

After the war, Mary Ann delved into another new challenge — to study law at Howard University. There was just one problem — the historically black school didn’t allow women into their law school. Mary Ann filed a sex discrimination suit and won. It took many years of study, but at the age of sixty, she got her law degree. Becoming the second black woman attorney in the U.S., she spent the last ten years of her life practicing law.

There didn’t seem to be a moment’s rest for Mary Ann Shadd Cary, encapsulated by her best-known quote, “It is better to wear out than to rust out.” In the post-war years, she taught school and also was deeply involved in women’s suffrage, working with Susan B. Anthony and others in the movement. She died in 1893, at the age of 70.

Photo: Ontario’s Historical Plaques

More information about Mary Ann Shadd Cary

Wikipedia

Mary Ann Shadd Cary on Biography.com

National Women’s Hall of Fame

Civil War Women

Biographies

A Plea for Emigration by Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1852)

Mary Ann Shadd Cary: The Black Press and Protest

in the Nineteenth Century by Jane Rhodes

Visit

The Mary Ann Shadd Cary House , where she lived for some time in Washington, D.C. is located at 1421 W Street, though it isn’t open to the public.

The statue bust honoring Mary Ann Shadd Cary is located in BME Freedom Par k in Chatham, Ontario, where she lived and from where the Provincial Freeman was published for part of its run.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Mary Ann Shadd Cary appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 26, 2018

Insightful Quotes by Lydia Maria Child

Lydia Maria Francis Child (1802 –1880) was an American author, social reformer, journalist, and abolitionist. A native of Medford, Massachusetts, she was educated despite her father’s disapproval. Child’s passion for learning led to her writing many works of fiction and nonfiction, as well as her dedicated advocacy of the rights of women and Native Americans.

Later in life, her views became a bit muddled, but as a mid-19th-century author, she’s still considered influential. Here’s a compilation of honest and insightful quotes by Lydia Maria Child.

“The eye of genius has always a plaintive expression, and its natural language is pathos.”

“You find yourself refreshed in the presence of cheerful people. Why not make an honest effort to confer that pleasure on others? Half the battle is gained if you never allow yourself to say anything gloomy.”

“Belief in oneself is one of the most important bricks in building any successful venture.”

“I was gravely warned by some of my female acquaintances that no woman could expect to be regarded as a lady after she had written a book.”

“That a majority of women do not wish for any important change in their social and civil condition, merely proves that they are the unreflecting slaves of custom.”

“That a majority of women do not wish for any important change in their social and civil condition, merely proves that they are the unreflecting slaves of custom.”

Child is the author of the famous Thanksgiving poem,

Over the River and Through the Wood

“Every human being has, like Socrates, an attendant spirit; and wise are they who obey its signals. If it does not always tell us what to do, it always cautions us what not to do.”

“It is right noble to fight with wickedness and wrong; the mistake is in supposing that spiritual evil can be overcome by physical means.”

“Home – that blessed word, which opens to the human heart the most perfect glimpse of Heaven, and helps to carry it thither, as on an angel’s wings.”

“Childhood itself is scarcely more lovely than a cheerful, kindly, sunshiny old age.”

“Misfortune is never mournful to the soul that accepts it; for such do always see that every cloud is an angel’s face.”

“None speak of the bravery, the might, or the intellect of Jesus; but the devil is always imagined as a being of acute intellect, political cunning, and the fiercest courage. These universal and instinctive tendencies of the human mind reveal much. ”

“Belief in oneself is one of the most important bricks in building any successful venture.”

“Economy, like grammar, is a very hard and tiresome study, after we are twenty years old.”

“Young ladies should be taught that usefulness is happiness, and that all other things are but incidental.”

“A mind full of piety and knowledge is always rich; it is a bank that never fails; it yields a perpetual dividend of happiness.”

The Frugal Housewife by Lydia Maria Child on Amazon

“In early childhood, you lay the foundation of poverty or riches, in the habits you give your children. Teach them to save everything,—not for their own use, for that would make them selfish—but for some use. Teach them to share everything with their playmates; but never allow them to destroy anything.”

“One great cause of the vanity, extravagance and idleness that are so fast growing upon our young ladies, is the absence of domestic education.”

“If young men and young women are brought up to consider frugality contemptible, and industry degrading, it is vain to expect they will at once become prudent and useful, when the cares of life press heavily upon them.”

“Law is not law, if it violates the principles of eternal justice.”

“In politeness, as in many other things connected with the formation of character, people in general begin outside, when they should begin inside; instead of beginning with the heart, and trusting that to form the manners, they begin with the manners, and trust the heart to chance influences. The golden rule contains the very life and soul of politeness.”

“Flowers have spoken to me more than I can tell in written words. They are the hieroglyphics of angels, loved by all men for the beauty of the character, though few can decypher even fragments of their meaning.”

“The cure for all the ills and wrongs, the cares, the sorrows, and the crimes of humanity, all lie in that one word ”Love.” It is the divine vitality that everywhere produces and restores life.”

“Every human being has… an attendant spirit…. If it does not always tell us what to do, it always cautions us what not to do.”

“I will work in my own way, according to the light that is in me.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Insightful Quotes by Lydia Maria Child appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 24, 2018

Lola Ridge

Lola Ridge (born Rose Emily Ridge (December 12, 1873 – May 19, 1941) was an Irish-American radical poet and editor. “Anything that burns you” was the advice she gave English critic Alice Hunt Bartlett when she asked what poets should be writing in 1925.

“I write about something that I feel intensely. How can you help writing about something you feel intensely?” The New York Times declared her “one of America’s our best poets” when she died but her interest in radicalism, feminism, and experimental poetry wrote her out of literary history.

“An early, great chronicler of New York life,” wrote Robert Pinsky in a Slate column about Ridge in 2011. This year is the 100th anniversary of her first and most important book, The Ghetto and Other Poems, celebrating the Jewish immigrants of the Lower East Side:

They are covering up the pushcarts…

Now all have gone save an old man with mirrors–

Little oval mirrors like tiny pools.

He shuffles up a darkened street

And the moon burnishes his mirrors till they shine like phosphorus…

The moon like a skull,

Staring out of eyeless sockets at the old men trundling home the pushcarts.

Irish-born Ridge grew up in New Zealand, gave parties in the Village for William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, Jean Toomer, and Hart Crane, edited two of the most important modernist magazines, Broom and Others, and wrote ground-breaking poetry.

A year after the publication of The Ghetto and Other Poems, Ridge gave a speech in Chicago called “Woman and the Creative Will,” about how sexually constructed gender roles hinder female development – ten years before Virginia Woolf wrote “A Room of One’s Own.”

Ridge worked on an expanded version of her speech for years until Viking, her publisher, told her it wouldn’t sell. The title poem of her second book, Sun-up and Other Poems, is told in the voice of a bad girl who beats her doll, bites her nurse, wonders “if God has spoiled Jimmy” after he exposes himself, and intimates that her imaginary friend is her bisexual half.

A bigamist as well as an anarchist, Ridge left her son in an orphanage in L.A. soon after her arrival in the U.S., when she went to work for Emma Goldman and Margaret Sanger in New York. Ten years later, she protested Sacco and Vanzetti’s execution in Massachusetts, and faced down a rearing police horse.

Solo and broke in the next decade, she traveled to Baghdad and Mexico – and took a lover at sixty-one. Her five books of poetry contain poems about lynching, execution, race riots, and imprisonment. They also contained imagist poems of great power:

Brooklyn Bridge

Pythoness body — arching

Over the night like an ecstasy —

I feel your coils tightening …

And the world’s lessening breath.

“Nice is the one adjective in the world that is laughable applied to any single thing I have ever written,” Ridge announced in 1932. The Rumpus wrote that she is “a model for poets today inspired by contemporary social movements addressing racial justice, economic inequality, and an array of sexual freedom issues.”

Lola Ridge died in Brooklyn, NY in 1941.

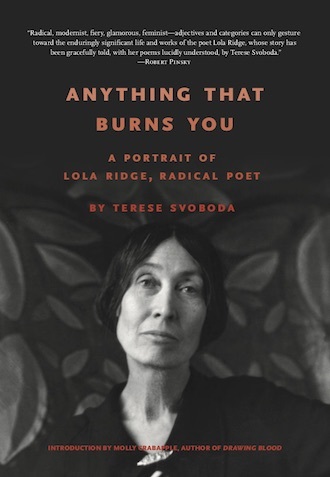

Anything That Burns You: A Portrait of Lola Ridge, Radical Poet on Amazon

Contributed by Guggenheim-winner Terese Svoboda, the author of 18 books of poetry, fiction, memoir and translation. She has most recently published Anything That Burns You: A Portrait of Lola Ridge, Radical Poet (Schaffner Press, 2018). “Terese Svoboda is one of those writers you would be tempted to read regardless of the setting or the period or the plot or even the genre.” — Bloomsbury Review

Terese Svoboda’s biography of Lola Ridge, Anything That Burns You: A Portrait of Lola Ridge, Radical Poet is now available in paperback, with an introduction by radical artist/author Molly Crabapple. “No one who cares about American culture will want to miss this book.” –– Cary Nelson, editor of Anthology of Modern American Poetry.

Major Works

The Ghetto, and Other Poems (1918)

Sun-Up, and Other Poems (1920)

Red Flag (1927)

Firehead (1929)

Dance of Fire (1935)

Collected Early Work of Lola Ridge (2018)

Biographies

Anything That Burns You: A Portrait of Lola Ridge, Radical Poet

by Terese Svoboda (2016, 2018)

More information

Wikipedia

Lola Ridge at Poetry Foundation

Lola Ridge on Poem Hunter

Articles, news, etc.

Lola Ridge, a Great Irish Writer and Why You’ve Never Heard of Her

Lola Ridge, the Radical Modernist We Won’t Forget Twice

“Anything That Burns You”: Lola Ridge

Archives

Lola Ridge Papers at Smith College

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Lola Ridge appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 23, 2018

17 Feminist Quotes from The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir

Simone de Beauvoir (1908 – 1986) was a French author, existential philosopher, political activist, feminist, and social theorist. Her most enduring work, The Second Sex (1949) is still read and studied as an essential manifesto on women’s oppression and liberation.

Filled with ideas considered radical at the time it was published, the book made her an intellectual force to be reckoned with, and inspired a generation of women to shake up the status quo. Here are quotes from The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir that will make you question how far we’ve come, and how far we still have to go.

“It is perfectly natural for the future woman to feel indignant at the limitations posed upon her by her sex. The real question is not why she should reject them: the problem is rather to understand why she accepts them.”

“Representation of the world, like the world itself, is the work of men; they describe it from their own point of view, which they confuse with absolute truth.”

“Few tasks are more like the torture of Sisyphus than housework, with its endless repetition: the clean becomes soiled, the soiled is made clean, over and over, day after day.”

“The whole of feminine history has been man-made. Just as in America there is no Negro problem, but rather a white problem; just as anti-Semitism is not a Jewish problem, it is our problem; so the woman problem has always been a man problem.”

“Her wings are cut and then she is blamed for not knowing how to fly.”

“One’s life has value so long as one attributes value to the life of others, by means of love, friendship, indignation, compassion.”

“In itself, homosexuality is as limiting as heterosexuality: the ideal should be to be capable of loving a woman or a man; either, a human being, without feeling fear, restraint, or obligation.”

The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir on Amazon

“When we abolish the slavery of half of humanity, together with the whole system of hypocrisy that it implies, then the ‘division’ of humanity will reveal its genuine significance and the human couple will find its true form.”

“All oppression creates a state of war. And this is no exception.”

“Men do not like tomboys, nor bluestockings, nor thinking women; too much audacity, culture, intelligence, or character frightens them.”

“One is not born a genius, one becomes a genius; and the feminine situation has up to the present rendered this becoming practically impossible.”

“On the day when it will be possible for woman to love not in her weakness but in strength, not to escape herself but to find herself, not to abase herself but to assert herself — on that day love will become for her, as for man, a source of life and not of mortal danger.”

You might also like: Philosophical Quotes by Simone de Beavuoir

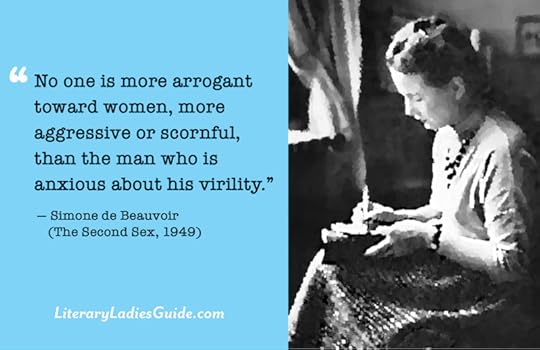

“No one is more arrogant toward women, more aggressive or scornful, than the man who is anxious about his virility.”

“Man is defined as a human being and woman as a female – whenever she behaves as a human being she is said to imitate the male.”

“Without a doubt it is more comfortable to endure blind bondage than to work for one’s liberation; the dead, too, are better suited to the earth than the living.”

“The curse which lies upon marriage is that too often the individuals are joined in their weakness rather than in their strength, each asking from the other instead of finding pleasure in giving.”

“To catch a husband is an art; to hold him is a job.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 17 Feminist Quotes from The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 22, 2018

Lydia Maria Child

Lydia Maria Francis Child (February 11, 1802 – October 20, 1880) was a prolific American author, social reformer, journalist, and abolitionist. Born in Medford, Massachusetts. She was educated despite the disapproval of her father, a baker, who thought she ought not to read at all. But Lydia’s appetite for learning was voracious, and the books she devoured were supplied primarily by her brother Convers Francis, who later became a Unitarian minister and professor at Harvard Divinity School.

When Lydia was twelve, her mother died and she was sent to live with an older married sister in Norridgewock, Maine. There she had contact with native Americans of the Penobscot and Abenaki tribes and visited them in their wigwams.

According to Elaine Showalter, author of A Jury of Her Peers, as a child, Lydia “saw a Penobscot woman who had borne a child and then walked four miles through the snow. She also met the Penobscot chief Captain Neptune.” These early encounters and friendships informed her lifelong passion to advocate on behalf of Native Americans.

First novels and a challenging marriage

Her first novel, Hobomok (1824) was published under the pseudonym “An American,” because she was warned that “no woman could expect to be regarded as a lady after she had written a book.” Set during the colonial period, the story concerns the marriage of a white woman, Mary Conant, to Hobomok, the titled Native American, and how she raised her son in white society after the death of her husband. The mixed marriage theme was quite taboo, and at first, the novel fared poorly.

The North American Review wrote that the novel was “unnatural” and “revolting to every feeling of delicacy.” Lydia was a good self-promoter, though, and through her efforts among the Boston literati, the novel was read and became successful.

From 1826 to 1834, Lydia edited The Juvenile Miscellany, the first American children’s monthly periodical.

Her second novel, The Rebels, or Boston Before the Revolution (1825) was even less favorably reviewed than Homobok had at first been. One critic who was kind to the book was David Lee Child, a brilliant but erratic Boston lawyer and journalist, who was so fast and loose with his writing that he earned the nickname David Libel Child. Reader, she married him.

From the time Lydia hitched her fortunes to David’s in 1928, her life was one of work and worry. She continually had to earn money to pay his legal costs and debts. Like Louisa May Alcott who came slightly after her, she considered writing as a way to make a living, rather than as a means of artistic expression. Lydia desperately needed money, and in addition to writing, she also took in boarders and taught school.

The Frugal Housewife

In 1829, Lydia published The Frugal Housewife, which was “dedicated to those who are not ashamed of economy.” Aside from basic recipes, she also provided advice on basic matters of housekeeping and home repairs. It wasn’t a rarified view of home life, and Lydia was critiqued for her “indelicacy.”

Still the book was wildly successful. Emphasizing frugality in the kitchen and self-reliance in the household, it went through dozens of printings, and was the first domestic cookbook to rival Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery (1796). The Frugal Housewife is still in print.

The Frugal Housewife by Lydia Maria Child on Amazon

The cause of abolition

In the early 1830s, Lydia and David child began to devote themselves to the anti-slavery cause, and in 1833 she published An Appeal for that Class of Americans called Africans, a stirring portrayal of the evils of slavery, and an argument for immediate abolition. This book was influential in winning recruits to the anti-slavery cause.

Lydia remained devoted to the cause of abolition. From 1840 to 1844, Lydia and David edited the Anti-Slavery Standard in New York City. After the Civil War, she worked on behalf of the rights of freed slaves. She also returned to her early interest in the rights of Native Americans.

A strangely tainted legacy

However, her views had become tainted with conservatism and bias. In her 1868 book An Appeal for the Indians she wrote, “How ought we to view the peoples who are less advanced than ourselves?” and professed “considerable repugnance” toward them. It’s unclear why such a passionate social reformer, whose pen flowed so freely, should have ended up in this manner. Elaine Showalter observed:

“It is ironic that Child, who started out as one of the most passionate, defiant, and iconoclastic writers of her generation, especially in her hatred of Calvinism, her resistance to patriarchal tyranny, and her opposition to American oppression of its ‘less advanced’ peoples, should end by repeating the psychological patterns she had so brilliantly analyzed and condemned.

Child’s literary career was marked by debate and duality; in her fiction she structured plots around people with complex choices between two radically different ways of life … but toward the end of her life, Child found herself ‘too old to write imaginative things.'”(from A Jury of Her Peers, 2009)

Despite her creeping conservatism, she was a founding member of the Massachusetts Women’s Suffrage Association and wrote The History of the Conditions of Women in Various Ages and Nations, which influenced the generation of suffragists that came after her.

The messy and contradictory end to her reputation as a reformer notwithstanding,Lydia Maria Child is considered a highly influential 19th-century author and reformer. She died in Wayland, Massachusetts, on October 20, 1880, at age 78.

Child is the author of the famous Thanksgiving poem,

Over the River and Through the Wood

Major works

This is but a partial list of Lydia Maria Child’s profuse output:

Hobomok (1824)

The Rebels (1825)

The (American) Frugal Housewife (1829), one of the earliest American books on domestic economy

The Mother’s Book (1831), a pioneer cookbook republished in England and Germany

The Girls’ Own Book (1831)

History of Women (2 vols., 1832), Good Wives (1833)

The Anti-Slavery Catechism (1836)

Philothea (1836), a romance of the age of Pericles

Letters from New York (2 vols., 1843-1845)

Fact and Fiction (1847)

The Power of Kindness (1851)

Isaac T. Hopper: a True Life (1853)

The Progress of Religious Ideas through Successive Ages (3 vols., 1855)

Autumnal Leaves (1857)

Looking Toward Sunset (1864)

The Freedman’s Book (1865)

A Romance of the Republic (1867)

Aspirations of the World (1878)

More information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Child’s books on Goodreads

Poetry Foundation

History of American Women

Read and listen online

Project Gutenberg

Librivox

Internet Archive

Articles, News, etc.

Lydia Maria Child’s ‘Frugal Housewife’ the Must-Read Book of its Day

Research

Lydia Maria Child papers, Columbia University

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Lydia Maria Child appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 20, 2018

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe (June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896), American author and abolitionist, is best known for the anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She grew up in a large, socially progressive family of ministers, authors, reformers, and educators who were well known in their time.

Among her siblings were the prominent minister Henry Ward Beecher, and educator Catharine Beecher. Harriet showed an early talent for writing and in her early twenties had a steadily paying profession, contributing articles to numerous publications.

Her husband, Calvin Ellis Stowe was a biblical scholar and educator. The two were married in 1836. He was a firm supporter of her talents, but was no help in the household, and not much of a provider. Struggling with divided loyalties, her assertion to her husband in this letter, “If I am to write, I must have a room to myself” neatly presages Virginia Woolf’s declaration that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

A working mother and writer desires to do more

Harriet Beecher Stowe sold anything and everything (sketches, poems, religious tracts, etc.) she could to support her growing family, since her husband was a poor clergyman. Though she bore seven children and struggled in genteel poverty, she found a way to write for profit and purpose. Still, there were always conflicting feelings. In 1841 she wrote to her husband:

“Our children are just coming to the age when everything depends on my efforts. They are delicate in health, and nervous and excitable and need a mother’s whole attention. Can I lawfully divide my attention by literary efforts?”

The book Stowe longed to write “to make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is” was put off from one year to the next:

“As long as the baby sleeps with me nights I can’t do much at anything, but I will do it at last.”

At age 39, still in the midst of tending to her large family, Stowe found a way to disseminate the story she longed to tell, publishing monthly installments of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in an abolitionist newsletter. With each issue, public interest built.

Inspiration for Uncle Tom’s Cabin

However much Stowe longed for money and privacy, it could be argued that being a mother played a pivotal role in creating her magnum opus, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. When she lost her beloved son Samuel Charles to cholera at age 18 months, the grief was crushing. Later she claimed that this loss helped her empathize with slave mothers who whose children were torn from them to be auctioned off.

She wrote in an 1853 letter:

“I wrote what I did because as a woman, as a mother, I was oppressed and broken-hearted with the sorrows and injustice I saw … It is no merit in the sorrowful that they weep, or to the oppressed and smothering that they gasp and struggle, not to me, that I must speak for the oppressed — who cannot speak for themselves.”

Meeting escaped slaves while living in Cincinnati and hearing about their plights was another impetus for Harriet’s desire to use her talent to give slavery a human face, and expose its injustice. The passing of the Fugitive Slave act of 1853 gave her the final push to write the story she so long to tell. Later she would say that she did not actually write it on her own, but merely took dictation from God.

First international bestseller

Stowe became the first American author whose book could claim the distinction of being an international best seller. After the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852, no book sold faster out of the gate; 1.5 million copies were sold worldwide by the end of its first year, and in the entire nineteenth century, only the Bible sold more copies. The book not only helped change the course of history, but changed the business of publishing as it was known.

It may be overstating the case to claim that the book helped to ignite the Civil War, though some historians do believe that this book laid the groundwork. President Abraham Lincoln was quoted as saying when he met Stowe in 1862, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!”

This incident, or at least what the president said to the author, may be a legend. But what is considered true is that the book helped create a shift in pubic opinion about slavery. There was also a swift and serious backlash from slavery apologists as well as theatrical adaptations. Though the public — both in the U.S. and England — bought the book in droves, critics weren’t always kind to the book.

How Harriet Beecher Stowe was inspired to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Financial rewards

Having struggled financially in all her married life, Stowe was amazed by the income she received from the sale of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, telling a friend and fellow abolitionist in an 1853 letter:

“You ask with regard to the remuneration which I have received for my work here in America. Having been poor all my life and expecting to be poor the rest of it, the idea of making money by a book which I wrote just because I couldn’t help it, never occurred to me. It was therefore an agreeable surprise to receive ten thousand dollars as the first-fruits of three month’s sale. I presume as much more is now due.”

More novels and legacy

Stowe suffered devastating losses as a mother. Aside from the aforementioned Samuel Charles, another son drowned while attending college at age 19. A third son, having returned whole from serving for the Union in the Civil War, moved to San Francisco and went missing, never to be heard from again. Stowe was solely in charge of the domestic duties and children, as were all women of her time. Writing was done in the midst of vast responsibilities and intermittent grief. It was a wonder that she was able to be so productive.

Stowe continued to write novels (Dred, The Minister’s Wooing, Oldtown Folks, and The Pearl of Orr’s Island) as well as essays and articles. Though the literary merits of her work have long been debated, there is little dispute that Uncle Tom’s Cabin caused a major shift in public perception of slavery.

Harriet Beecher Stowe died in 1896 in Hartford, CT, at age 85.

Harriet Beecher Stowe page on Amazon

More about Harriet Beecher Stowe on this site

How Harriet Beecher Stowe was inspired to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Motherhood, and Writing

8 Feminist Quotes by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Perceptive and Personal Quotes by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Quotes from the Novels of Harriet Beecher Stowe

Major Works

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852)

Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp (1856)

The Minister’s Wooing (1859)

The Pearl of Orr’s Island (1862)

Oldtown Folks (1869)

Lady Byron Vindicated (1870)

My Wife and I (1871)

Biographies about Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life by Joan D. Hedrick

Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe by Harriet Beecher Stowe

More Information

Wikipedia

The Stowe Society

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Life

Harriet Beecher Stowe on Biography.com

Harriet Beecher Stowe page on Amazon.com

Reader discussion of Stowe’s books on Goodreads

Read and listen online

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s works on Project Gutenberg

Audio versions of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s books on Librivox

Articles & News

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Spiritual Adventurer

Abolition Film Shoots at Stowe House

College Denies Local’s Claim About Where Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”

James Holly vs. Harriet Beecher Stowe

The National and International Impact of Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Visit

The Stowe House – Cincinnati, OH

The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center – Hartford, CT

Uncle Tom’s Cabin – Dresden, Ontario, Canada

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Harriet Beecher Stowe appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir

She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir was originally published in France in 1943 as L’Invitee. The autobiographical, philosophical novel was based on de Beauvoir’s open relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre, and takes place just before and during World War II.

The novel’s main character, Françoise, is based on de Beauvoir herself, and Pierre is a thinly veiled Sartre. A younger woman, Xaviere, enters their lives as they form a ménage a trois. Xaviere is a mash-up of sisters Olga and Wanda Kosakiewicz.

The novels themes are freedom, dependence, sexuality, and the other. And in addition to the trials and tribulations of love and complex relationships, the story incorporates elements of existentialism, the philosophy that embraced by de Beauvoir and Sartre. Central to this philosophy is finding the meaning of life and self through free will, choice, and personal responsibility.

She Came to Stay wasn’t published in the U.S. until 1954 in its English translation. At that point, de Beauvoir had become known for the book that would come to define her — The Second Sex — considered a feminist classic since it first saw print. Here’s an American review of She Came to Stay that recognizes its multifaceted layers as a work of fiction and as a roman a clef:

From the original review of She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir (1954) in the Albany Democrat-Herald, March, 1954. Translated from the French.

When Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex was published, it blew up a storm among reviewers — male reviewers mostly … This attention to Simone de Beauvoir had its value — it has resulted in the publication of her novel, She Came to Stay, titled L’Invitee in the original 1943 Paris edition, one of the best of the French war era and still the most original Existential novel, rivaling Sartre’s Nausea.

A line from Hegel introducing the novel, “Each conscience seeks the death of the other,” is the philosophical key to the physical problem. That problem is the oldest of all — the triangle, Pierre and Françoise, people of the theatre, and Xaviere from Rouen.

The three live in love as one, suffering. Gerbert, an actor, comes in as an intermission for both Françoise and Xaviere. It’s Françoise’s story. Intelligent and beautiful, honest with herself and others, she accepts Pierre’s relationship with Xaviere, accepts the shallow Xaviere into her liaison. She has esteem for Pierre, he has respect for her.

She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir on Amazon

The needs of love

“You don’t realize it,” she said, “and that’s not surprising. You’ve so set your mind on this love of ours, that you’ve put it in safekeeping, beyond time, beyond life, beyond reach. From time to time, you think about it with satisfaction, but what has actually become of it, you never look to see.” She burst into sobs. “But I — I want to look.”

Xaviere, enamored with Parisian ways, can be nothing but unpredictable, capricious. She has “red peasant’s fingers,” beautiful wrists. Pierre is male, competent, a master in the theater and encompasses both women. With psychological sharpness, the author displays the conflict, the three pitted against each other yet unable to split up.

Simone de Beauvoir’s scalpel never hesitates as it cuts through layer after layer. Her lines are dramatic, though never overwrought; her people breathe and talk as in life they must. No philosophical asides are thrust in, although the theme is straight from philosophy — and transferring philosophy to living people and scenes is the most difficult problem a writer may try. the vociferous male reviewers now may take a second look, this time at Simone de Beauvoir, novelist.

You might also like:

Philosophical Quotes by Simone de Beauvoir

Quotes from She Came to Stay

“All she had to do was make the simplest of gestures — open her hands and let go her hold. She lifted one hand and moved the fingers of it; they responded, in surprise and obedience, and this obedience of a thousand little unsuspected muscles was in itself a miracle. Why ask for more?”

“At that moment, there were thousands of women all over the world listening breathlessly to the beating of their own hearts; each woman to her own heart, each woman for herself. How could she believe that she was the center of the world?”

“Day after day, minute after minute, Françoise had fled the danger; but the worst had happened, and she had at last come face to face with this insurmountable obstacle, which she had sensed, under vague forms since her earliest childhood. Behind Xavière’s maniacal pleasure, behind her hatred and jealousy, the abomination loomed, as monstrous and definite as death. Before Françoise’s very eyes, yet apart from her, existed something like a condemnation with no appeal: free, absolute, irreducible, an alien consciousness was rising.”

“Alone. She had acted alone. As alone as in death. One day Pierre would know. But even he would only know her act from the outside. No one could condemn or absolve her. Her act was her very own. “I have done it of my own free will. It was her own will which was being fulfilled, now nothing separated her from herself. She had chosen at last. She had chosen herself.”

More about She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir

In-depth 1954 analysis in Commentary Magazine

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Review on Tin House

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.