Nava Atlas's Blog, page 84

May 31, 2018

Harper Lee

Harper Lee (April 28, 1926 –February 19, 2016) was an American author best known for the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel To Kill a Mockingbird (1960). Born in Monroeville, Alabama, she was originally named Nelle Harper Lee.

Few novels have had the cultural impact of To Kill a Mockingbird, which has sold tens of millions of copies, and has been translated into more than 40 languages. Lee drew from her upbringing in a small southern town to tell an indelible American story.

Early years and education

Lee was the youngest of four children — two sisters and a brother. Her father, Amasa Coleman Lee, was a lawyer and member of the Alabama state legislature. Her mother, Frances Finch, rarely left the house; it’s now believed that she suffered from untreated bipolar disorder.

Truman Capote (then named Truman Persons) was a childhood friend and the inspiration for Dill, the eccentric neighbor boy in Mockingbird. Truman lived with his mother’s relatives in Monroeville after being virtually abandoned by his own parents.

Lee enjoyed writing throughout her childhood and developed an interest in English literature in high school. Her college studies began in 1944 at the all-female Huntingdon College in Montgomery, Alabama. Ever the tomboy, Lee didn’t share her classmates’ interest in dating and fashion, and stayed focused on her studies.

After transferring to the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa, Lee began writing for the college newspaper as well as its humor publication, the Rammer Jammer. She eventually became the editor of the latter.

Lee was accepted into the university’s law school in her junior year, which gave students the opportunity to begin studies toward a law degree while still undergraduates. But following her first year in the program, she announced to her family that she felt that writing, not law, was her true calling.

Becoming a New Yorker

In 1949, 23-year-old Lee moved to New York City. She worked as a ticket agent for Eastern Airlines and for British Overseas Air Corp (BOAC). She reconnected with her old pal Truman Capote, who was finding his place in the literary world, and became friends with Michael Martin Brown, a Broadway composer and lyricist, and his wife Joy.

Michael and Joy Brown became Lee’s angels: For Christmas 1956, they offered to support her for an entire year so that she could quit her day jobs and write full time. The Browns also helped her get a literary agent, who got an editor at J.B. Lippincott Company to acquire her manuscript. The story, set in a small Alabama town, would slowly and painstakingly take shape to become To Kill a Mockingbird. Jean Louise “Scout” Finch, the story’s main character, was a tomboyish yet sensitive girl who had much in common with the young Nelle Harper Lee.

Work With Truman Capote

Once her manuscript was finally completed, Lee worked as a research assistant for Truman Capote for an article he was writing for The New Yorker. The sensational murder of four members of the Clutter family in a small Kansas farming community would eventually become the groundbreaking “nonfiction novel” In Cold Blood.

Lee was disappointed by the lack of acknowledgment she received from Capote for her role in researching and assistance on In Cold Blood, and it caused a rift between them. Their estrangement deepened as Capote drifted deeper into drug culture.

Harper Lee page on Amazon

To Kill a Mockingbird

To Kill a Mockingbird was published in June of 1960 to instant acclaim and success. A coming-of-age story set in Maycomb, small Southern town, it’s told from the perspective of Jean Louise “Scout” Finch Scout’s father, Atticus Finch, is an attorney with integrity and wisdom to spare.

Scout and her older brother Jem are being raised by Atticus, a widower, and Calpurnia, their African-American housekeeper. Dill (the character inspired by Truman Capote) comes to town during the summers to stay with his aunt. He, Scout, and Jem plot ways to lure their mysterious neighbor, Arthur “Boo” Radley, out of his house so they can get a look at him.

One of the central aspects of the story is Atticus’s legal representation of a black man, Tom Robinson, who is accused of raping Mayella Ewell, a white woman. She and her father Bob Ewell, are considered the town’s “white trash.” The children learn that even plenty of proof that Tom is innocent isn’t enough for the all-white jury. Scout’s eyes are opened to the complexity of human nature, and its capacity for good and evil.

To Kill a Mockingbird was a popular as well as a critical success, lauded for capturing the complex social fabric of Southern life and examining unsettling issues of race and class in America. In addition to the Pulitzer Prize, the book won numerous other awards and was a selection of a number of book clubs.

The book made Harper Lee famous and also quite wealthy, though it didn’t change much about her frugal lifestyle. She shared a modest home with her oldest sister Alice, an attorney who oversaw many of Lee’s legal and financial affairs. She spent little on herself and generously donated to various charities and to the local Methodist church.

No one was more surprised by the incredible success of To Kill a Mockingbird than the author herself. In a 1964 interview, she said:

“I never expected any sort of success with Mockingbird. I didn’t expect the book to sell in the first place. I was hoping for a quick and merciful death at the hands of reviewers, but at the same time I sort of hoped that maybe someone would like it enough to give me encouragement. Public encouragement. I hoped for a little, as I said, but I got rather a whole lot, and in some ways this was just about as frightening as the quick, merciful death I’d expected.”

You might also like:

Quotes from to Kill a Mockingbird

Film version

The 1962 film version of To Kill a Mockingbird cemented the novel’s reputation and success. With Gregory Peck as Atticus and two children from Alabama — Mary Badham and Phillip Alford — as Scout and Jem, the film was completely true to the spirit of the novel. Peck won an Academy Award for Best Actor.

Harper Lee originally wanted the role of Atticus Finch to go to Spencer Tracy, even writing him a letter to ask that he star in the film. He was unavailable, but as it turned out, there couldn’t have been a more fitting actor to portray Atticus than Gregory Peck. Lee came to came to adore him, and the two remained friends until Peck’s death in 2003.

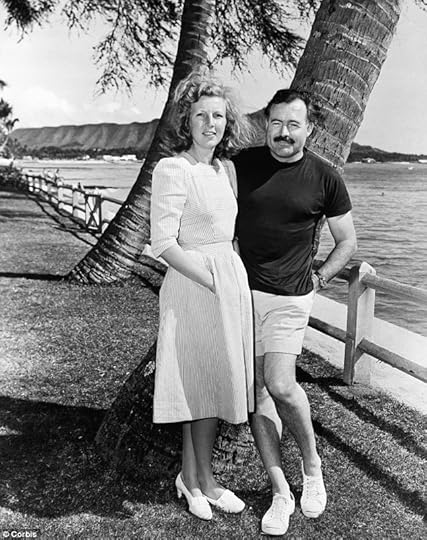

Gregory Peck with Harper Lee

Later Years

By the 1970s Harper Lee seemed to have had enough of public life. She retreated from view, gave few interviews, and divided her time between New York City and Monroeville.

In 2007 Harper Lee had a stroke and was dealing with various other health issues including the decline of her hearing, and eyesight, and short-term memory. After the stroke, she moved into an assisted living facility in Monroeville.

Go Set a Watchman

Go Set a Watchman was the original manuscript for what was to become To Kill a Mockingbird. It followed the lives of the characters from To Kill a Mockingbird at a later age. Scout was portrayed as a young woman in her twenties returning from New York City to her hometown in the south. Her editor astutely requested that she review the story so that it’s told from the perspective of Scout as a child. Lee spent the next two years revising the story.

Many years later, Go Set a Watchman was discovered by her lawyer, Tonja Carter, in a safe deposit box. HarperCollins announced its publication in July, 2015. Controversy immediately ensued. Some wondered if the author, then 88, was coerced in any way. Lee issued this statement through her attorney: “I’m alive and kicking and happy as hell with the reactions to Watchman.”

Go Set a Watchman on Amazon

What was most upsetting to readers was that the saintly Atticus of Mockingbird was portrayed in Watchman as a racist with ties to the Ku Klux Klan.

The novel sparked many debates. It won over many fans hungry for more about the beloved characters of Mockingbird, but also broke the hearts of readers who disliked the revisionist view of Atticus. Another thing the book broke was sales records. It sold 720,000 copies in the first 36 hours of sales. Reviews were far more mixed than they had been for Mockingbird. It gave comfort to some readers but not others that in the end, Go Set a Watchman wasn’t a sequel to To Kill a Mockingbird, but an early draft of the book that it would evolve into.

Legacy

Though Harper Lee spent only a handful of years in the public eye, her contribution to literature and culture can’t be overstated. In addition to the 1961 Pulitzer Prize for To Kill a Mockingbird, she received countless awards, including the Alabama Humanities Award (2002) and the Presidential Medal of Freedom (2007) In 2007, she was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Harper Lee died in her sleep on February 19, 2016, in her hometown of Monroeville and was buried in Hillcrest Cemetery. She was 89.

More about Harper Lee on this site

Quotes from To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Dear Literary Ladies: What’s scarier, failure or success?

Major Works

To Kill a Mockingbird

Go Set a Watchman

More information

Wikipedia

Encyclopedia of Alabama

biography.com

19 Things You Never Knew About Harper Lee and To Kill a Mockingbird

Reader discussion of Harper Lee’s books on Goodreads

Biographies

Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee by Charles J. Shields

Film adaptation

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

Research and visit

Monroe County Museum

Harper Lee letters, Emory University

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Harper Lee appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 28, 2018

Betty Smith

Betty Smith (December 15, 1896 – January 17, 1972), an American novelist and playwright, is best remembered for her evocative coming-of-age story, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Born Elizabeth Wehner, she shared a birthdate — December 15 — with the heroine of that beloved novel, Francie Nolan, though the author’s birth year was five years earlier than Francie’s.

Betty herself had a rough childhood, growing up in the tenements of Brooklyn at the dawn of the 1900s. The family moved several times before settling in a top-floor tenement on Grand Street that served as the model for the Nolan family’s flat in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

Her immigrant parents struggled in their impoverished new environment. Katie, her mother was tough as nails, yet passed on to Betty (who in her youth called Lizzie ) a love of storytelling. Her father, about whom little is known other than his alcoholism, died when she was nineteen. Betty borrowed from her own life to put to good use in her novels, drawing from the various jobs she held, her personal life, and her family ties.

A young mother and an education

In The Heroine’s Bookshelf, Erin Blakemore encapsulates Betty’s formative years:

Faced with a painful home life, Lizzie was eager to create her own family. Her parents forced her to leave school and start working at age fourteen, and insecure, resentful Lizzie quickly moved to associate herself with education and upward mobility. Brooklyn’s settlement houses were her social center: there, she danced, debated, studied, and met George Smith, a driven young man who wanted to get out of Brooklyn as much as she did.

When he moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan to study law, she followed. But life as a young wife was no easier than it was during the lean years of her childhood … The intervening years had brought two daughters, Nancy and Mary. Now a young mother, Lizzie felt even more pressure to educate herself. She petitioned to attend the local high school, an unusual request for a married woman. But though she worked hard, life constantly interrupted her studies.

Worse still, the man she had followed to this far-off place became more distant with each passing year. It seemed that George’s burgeoning legal practice and rising political career had no place for a naïve, heavily accented wife. But Lizzie had aspirations of her own. She turned a blind eye to George’s affairs and focused instead on her new plan: to become a writer.

Now, Lizzie became Betty Smith the aspiring writer. When her two daughters entered grade school, she began her studies she the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. As a student she excelled, winning the prestigious Avery Hopwood Award in dramatic writing, and enjoying an education in journalism, literature, and drama.

Betty’s marriage unraveled as the couple’s lives continued to diverge. Their attempts to reconcile proved futile, and they separated for good in 1933. George Smith would go on to serve in the U.S. Senate and had a successful legal career.

Immersed in theater

Betty followed her studies at the University of Michigan with three years at the Yale Drama School in New Haven. While there, she wrote and published seven one-act plays. Overwhelmed with the cost of tuition and the care of her children (it’s unclear why her successful ex-husband wasn’t doing more to support them), Betty returned to New York City with them and moved in with her mother.

It was in the depths of the Depression that Betty fortuitously found a position in the Works Projects Administration. She was assigned to the Federal Theatre Project as a play reader, and in May of 1936, she was transferred to Chapel Hill, North Carolina. By then, she had become an accomplished playwright, and by the end of her career, had written some seventy plays. More awards would come her way, including the Rockefeller Fellowship in drama and a Dramatists Guild-Rockefeller Fellowship in playwriting.

Betty Smith’s lasting legacy is A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

It was during her Chapel Hill years that began working on her first novel. At first titled They Lived in Brooklyn, it was rejected by a number of publishers before Harper and Brothers accepted it. It was released in 1943 released with the title A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Even before its 1943 publication, Twentieth Century Fox snapped up film rights. What followed was nothing short of astounding success, quickly selling millions of copies and was translated into multiple languages. Betty Smith became a public figure.

Francie Nolan was a modern heroine for the times. Somewhat plain and awkward, growing by dint of sheer determination and hard work rather than genius or dazzling personality. Francie endures loss and hardship, yet savors the small joys and triumphs of her world in a corner of Brooklyn. Comparing Betty’s life with that of Francie’s, it’s easy to see the parallels.

Just days before the book that made her famous was published, Betty married Joseph Piper Jones, a columnist for the Chapel Hill Weekly.

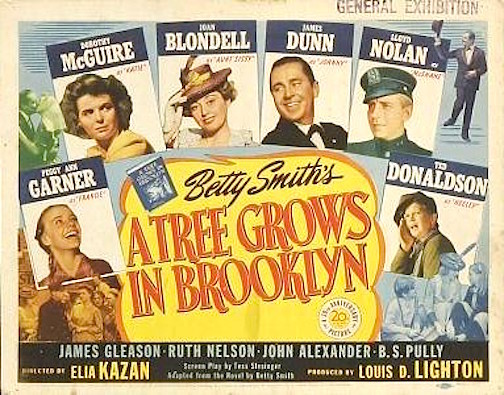

Betty Smith helped write the film adaptation of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

Screenwriting, and another change in partners

In 1945, Smith helped write the screenplay for the film version of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, though it was somewhat altered and compressed compared with the timeline of the book. She also assisted in the screen adaptation for Joy in the Morning. In 1951, she helped write and put together the musical version of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

It was that same year that Betty and Joseph Piper Jones divorced. Not long after, she married Robert Voris Finch, whom she had met during her studies at Yale. He died in 1959, after which Betty remained unmarried.

Legacy

Though known as a novelist and playwright, Betty was also as a cultural historian. Her novels and plays are richly detailed records of life in the early twentieth century. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn is considered one of the great American novels of the twentieth century. Though she left Brooklyn as a young woman, it never left her. She said of her place of origin:

“Brooklyn is not a city. It is a faith. You cannot become a Brooklynite. You have to be born one. I was born in Brooklyn. For a long time I wanted to write about it the way I knew it. One day I bought a ream of paper and started to write.”

She died of pneumonia in 1972 at the age of 75, in Shelton, Connecticut.

You might also like: Memorable Quotes from A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

More about Betty Smith on this site

Betty Smith’s “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” on the Screen

Memorable Quotes from A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

Books by Betty Smith: A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and More

Major Works

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1943)

Joy in the Morning (1947)

Maggie-Now (1958)

Tomorrow Will Be Better (1963)

Biographies about Betty Smith

Betty Smith: Life of the Author of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

by Valerie Raleigh Yow

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Betty Smith’s books on Goodreads

Film adaptations

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945)

Joy in the Morning (1965)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Betty Smith appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 27, 2018

Quotes From To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Harper Lee (1926 – 2016) was an American author, best known for the Pulitzer Prize-winning book To Kill A Mockingbird (1960). Her second novel, Go Set A Watchman (2015), was initially considered to be a sequel, as it follows the continuing story of the Finch family, but was later revealed to be an early draft of To Kill A Mockingbird.

As one of the nation’s most celebrated writers, she remained unpublished and largely out of the public eye during the fifty five-year period between To Kill A Mockingbird and Go Set a Watchman. A book once described by Oprah Winfrey as “our national novel,” To Kill A Mockingbird has remained celebrated and highly regarded through the years. Here are some outstanding quotes from To Kill A Mockingbird, truly a Great American Novel.

“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view … Until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it.”

“Until I feared I would lose it, I never loved to read. One does not love breathing.”

“People generally see what they look for, and hear what they listen for.”

“The one thing that doesn’t abide by majority rule is a person’s conscience.”

“Atticus told me to delete the adjectives and I’d have the facts.”

“I think there’s just one kind of folks. Folks.”

“People in their right minds never take pride in their talents.

“As you grow older, you’ll see white men cheat black men every day of your life, but let me tell you something and don’t you forget it—whenever a white man does that to a black man, no matter who he is, how rich he is, or how fine a family he comes from, that white man is trash.”

“It was times like these when I thought my father, who hated guns and had never been to any wars, was the bravest man who ever lived.”

You may also enjoy: Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee by Charles J. Shields

“Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

“With him, life was routine; without him, life was unbearable.”

“It’s never an insult to be called what somebody thinks is a bad name. It just shows you how poor that person is, it doesn’t hurt you.”

“Simply because we were licked a hundred years before we started is no reason for us not to try to win.”

“You can choose your friends but you sho’ can’t choose your family, an’ they’re still kin to you no matter whether you acknowledge ’em or not, and it makes you look right silly when you don’t.”

“There are just some kind of men who-who’re so busy worrying about the next world they’ve never learned to live in this one, and you can look down the street and see the results.”

“Before I can live with other folks I’ve got to live with myself. The one thing that doesn’t abide by majority rule is a person’s conscience.”

“Are you proud of yourself tonight that you have insulted a total stranger whose circumstances you know nothing about?”

“Shoot all the blue jays you want, if you can hit ’em, but remember it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee on Amazon

“It’s not necessary to tell all you know. It’s not ladylike — in the second place, folks don’t like to have someone around knowin’ more than they do. It aggravates them. Your not gonna change any of them by talkin’ right, they’ve got to want to learn themselves, and when they don’t want to learn there’s nothing you can do but keep your mouth shut or talk their language.”

“There’s a lot of ugly things in this world, son. I wish I could keep ’em all away from you. That’s never possible.”

“Bad language is a stage all children go through, and it dies with time when they learn they’re not attracting attention with it.”

“Courage is not a man with a gun in his hand. It’s knowing you’re licked before you begin but you begin anyway and you see it through no matter what. You rarely win, but sometimes you do.”

“Try fighting with your head for a change… it’s a good one, even if it does resist learning.”

“Cry about the simple hell people give other people — without even thinking. Cry about the hell white people give colored folks, without even stopping to think that they’re people too.”

More about Harper Lee:

Review: Harper Lee’s ‘Go Set a Watchman’ Gives Atticus Finch a Dark Side

Harper Lee, Author of ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ Dies at 89

Harper Lee’s Will, Unsealed, Only Adds More Mystery to Her Life

The Life, Death and Career of Harper Lee

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes From To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 25, 2018

E. Nesbit

E. Nesbit (August 15, 1858 – May 4, 1924), born Edith Nesbit, was an English novelist, short story writer, and poet best known for her imaginative books for children. Born in Kennington, Surrey, her father. a chemist, died before she was four. A sister’s poor health compelled the family to move almost continually until she was in her late teens. An imaginative yet nervous child, the family’s peripatetic ways would have an impact on the stories she would later write.

At eighteen, Edith married Hubert Bland. Though the couple had five children, the marriage was an unstable one, marked by Bland’s philandering and inability to make a living. She published under the name E. Nesbit, producing more than 40 books for children, and many more on which she collaborated. She also wrote eleven novels for adults, and many short stories.

She’s often credited with modernizing the classic children’s adventure story, infusing realism even when her tales included imaginary creatures or places. In that sense, she set the stage for the genre of contemporary fantasy. Nesbit was a politically active, ascribing to Marxism. She cofounded the Fabian Society, a socialist group that was later connected with the British Labor Party.

An introduction to E. Nesbit and her work

The following biography, which contains much bibliographic material about E. Nesbit’s best-known books, is adapted from her autobiography Long Ago When I was Young (Franklin Watts, 1966). It was written by Mary Noel Streatfeild (herself the author of a classic children’s book series known as the “shoes” books, which began in 1936 with Ballet Shoes):

The “E” stood for Edith, but she was always called Daisy. From the time she was seven until she was twelve she had no settled home. She was sent to boarding schools in Brighton and Sussex and in Stamford and Lincolnshire. Then, since the Nesbits were living in France, she was sent to a family in Pau who ha one little girl.

Then, as the family were still in France, to two different schools near Dinan and finally, when she was not het twelve, to a school in Germany. In one way or another all the schools were ill-chosen for the type of child she was. The school in Germany she loathed so violently that she — the most nervous of children — actually tried to run away from it. For a girl of eleven it took courage of a striking order.

Fortunately, though E. Nesbit died in 1924, some of her children lived on long after her and it was from this source that it was possible for her biographers to get an idea of what the young E. Nesbit was like. In her own reminiscences, Long Ago When I Was Young, she describes how nervous and sensitive a child she was, and also how temperamental.

She was one of those mercurial children — and was to be a mercurial grown-up — who is up in the sky at one moment and groveling as if in the mud the next. How much of herself and her storm-tossed childhood is in her books?

A curious writer

It is on the whole just the opposite side of the picture that comes out in her stories. Perhaps it was as a present to her child-self that E. Nesbit gave her fictional families such strong roots. Usually there is a clearly described permanent home. And, though the wildest adventures take place — some in everyday work and some in the world of magic — they are almost always shown in the context of a normal family life.

E. Nesbit was a curious writer. It was as if she hugged her characters, both children and magic creatures, to herself saying: “That’s all I’m going to tell you about that lot. Now I’ll tell you something new.” She wrote three books, for instance, about the Bastable children —The Treasure Seekers, The Wouldbegoods, and The New Treasure Seekers. When she got to the end of the latter, she had Oswald, who was supposed to have written the book, write: “It is the last story the present author means ever to be the author of.” And it was.

E. Nesbit page on Amazon

Five Children and It

Then there was the magic trilogy, Five Children and It, The Phoenix and the Carpet, and The Story of the Amulet. In these books, readers met Robert, Anthea, Jane, Cyril, and the baby called The Lamb. It was first the Psammead and the Phoenix who Nesbit placed in the foreground.

This was deliberately and carefully done so that she, who created in the Bastables — one of the most vivid families in all of children’s literature — could be sure that the children in this trilogy were so faintly drawn that none of us would recognize them if we met them in the street, whereas nobody could miss either the Psammead or the Phoenix.

The Railway Children

There is nothing remotely alike about E. Nesbit’s much-loved holiday home in France and Three Chimneys, the cottage in England in which the children in The Railway Children lived, but there is a connection in the reference to running wild. Until the railway children’s father was sent to prison they had lived a conventional existence — watched and looked after every moment of the day. The author writes:

“They were just ordinary suburban children and they lived with their Father and Mother in an ordinary red-brick-fronted villa, with coloured glass in the front door, a tiled passage that was called a hall, a bathroom with hot and cold water, electric bells, French windows, and a good deal of white paint, and ‘every modern convenience’ as the house agents would say.”

But when the children came to live in Three Chimneys, all these things vanished. There were no modern conveniences at all, not even running water. But what child cares about such things? What was thrilling for the children was that there was no school and no one to look after them. Mother supported her children just as Nesbit had supported hers, by writing, so she had to leave them to their own resources. All of every day was theirs to use exactly as they liked.

They had no raft on a pond on which to travel and explore, as had Nesbit and her brothers during the summer holiday in France, but they had a railway — and oh, what a joy that was.

The House of Arden and Harding’s Luck

It is almost certain that when Nesbit wrote The House of Arden she interned to tell a magic story around the two Arden children, Elfrida and Edred. The magic creatures were the Warps; there were three of them; all moles of Sussex origin, though what they spoke was a dialect of their own.

One year after she had introduced Elfrida and Edred she published Harding’s Luck, but this time Dickie, their cousin was the hero. Harding’s Luck, in spite of Dickie and several other good characters, is not considered one of Nesbit’s best books. But Dickie, both as lame Dickie from Deptford and as Richard Arden in the Past, is one of her best-drawn characters.

Legacy

When an author dies, as E. Nesbit did in 1924, too often their books are forgotten. This did not happen in her case, for the books have gone on, loved by generation after generation of children. Not all her books were great, but enough were for her name to belong forever to children’s literature. (—Noel Streatfeild, London, 1966)

Nesbit was an influence, directly or indirectly on writers who came after her, especially those who placed ordinary children in magical situations. These included P.L. Travers (author of Mary Poppins), C.S. Lewis, J.K. Rowling, and Diana Wynne Jones. In more contemporary fan fiction, Oswald Bastable, grown up from Nesbit’s The Treasure Seekers was the main character in a series of steampunk novels by Michael Moorcock. Four Children and It (2012) by Jacqueline Wilson is a contemporary sequel to the Five Children and It trilogy.

Some, like Gore Vidal, have argued that E. Nesbit wrote about children rather than for children, in a similar sense as Lewis Carroll did. Certainly, her books have an appeal to children of all ages, and are always ripe for rediscovery.

Major Works

In addition to the novels for children listed below, E. Nesbit produced numbers story collections, novels for adults, nonfiction, and poetry. For a more complete listing of her works, follow this link.

Bastable series

The Story of the Treasure Seekers (1899)

The Wouldbegoods (1901)

The New Treasure Seekers (1904)

Oswald Bastable and Others (1905)

Psammead series

Five Children and It (1902)

The Phoenix and the Carpet (1904)

The Story of the Amulet (1906)

The House of Arden series

The House of Arden (1908)

Harding’s Luck (1909)

Other novels for children

The Railway Children (1906)

The Enchanted Castle (1907)

The Magic City (1910)

The Wonderful Garden (1911)

Biographies and Autobiographies

Long Ago When I Was Young by E. Nesbit (1966; posthumous)

The Life and Loves of Edith Nesbit by Eleanor Fitzsimons (2018)

Film adaptations

The Railway Children (multiple adaptatio

More information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of E. Nesbit’s books on Goodreads

The Writing of E. Nesbit by Gore Vidal

Five Children and a Philandering Husband: E. Nesbit’s Private Life

Read and listen online

E. Nesbit’s books on Project Gutenberg

Audio versions on Librivox

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post E. Nesbit appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 22, 2018

In the Great Green Room: The Brilliant and Bold Life of Margaret Wise Brown

In the Great Green Room: The Brilliant and Bold Life of Margaret Wise Brown by Amy Gary is life story of the talented woman who created the classic children’s books Goodnight Moon and The Runaway Bunny. Though Margaret Wise Brown was only forty-two when she died unexpectedly, around one hundred books she wrote were published in her lifetime, and dozens more manuscripts were found after her death.

Margaret was not only a prolific writer, but an influential editor who helped usher in the golden age of children’s books in the mid-twentieth century. Imaginative, adventurous, and bold, she was a publishing legend most of us know little about and whose legacy shouldn’t be forgotten. This biography illuminates her fascinating life story.

Description of In the Great Green Room from the Flatiron Books edition, © 2016: The extraordinary life of the woman behind the beloved children’s classic Goodnight Moon and The Runaway Bunny comes alive in this fascinating biography of Margaret Wise Brown. Margaret’s books have sold millions of copies all over the world, but few people know that she was at the center of a children’s book publishing revolution. Her whimsy and imagination fueled a steady stream of stories, songs, an poems, and she was renowned for her prolific writing an business savvy, as well as her stunning beauty and endless thirst for adventure.

Margaret started her writing career by helping to shape the curious for the Bank Street School for Children, making it her mission to create stories that would rise above traditional fairy tales and allowed girls to see themselves as equals to boys. At the same time, she also experimented endlessly with her own writing. Margaret would spend days researching subjects, picking daisies, gazing at clouds, and observing nature, all in an effort to precisely capture a child’s sense of awe and wonder as he or she discovered the world.

In the Great Green Room by Amy Gary on Amazon

Clever, quirky, and incredibly talented, Margaret embraced life with passion, lived extravagantly off her royalties, went on rabbit hunts, and carried on long and troubled love affairs with both men and women.

Among them were the two great loves in Margaret’s life, one of whom was a gender-bending poet and ex-wife of John Barrymore. She went by the stage name Michael Strange, and she and Margaret had a tempestuous yet secret relationship. At one point they lived next door to one another so they could be together.

After the dissolution of their relationship and Michael’s death, Margaret became engaged to a younger man who happened to be the son of a Rockefeller and a Carnegie. But before they could marry Margaret died unexpectedly at the age of forty-two, leaving behind a cache of unpublished work and a timeless collection of books that would fo on to become classics in children’s literature.

Author Amy Gary captures the eccentric and exceptional life of Margaret Wise Brown and, drawing on newly discovered personal letters and diaries, reveals an intimate portrait to a creative genius whose unrivaled talent breathed new life into the literary world.

About Amy Gary

In 1990, Amy Gary discovered hundreds of unpublished works by Margaret Wise Brown in Margaret’s sister’s attic. Since then, Gary has catalogued, elite, and researched all of Brown’s writings. She has been covered in Vanity Fair, Entertainment Weekly, and on NPR, among other media outlets. She was formerly the director of publishing at Lucasfilm and headed the publishing department at Pixar Studios. Visit her on the web AmyGary.com.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post In the Great Green Room: The Brilliant and Bold Life of Margaret Wise Brown appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf (January 21, 1882 – March 28, 1941), born Adeline Virginia Stephen in London, epitomized rare literary genius. Despite debilitating battles with mental breakdowns, Woolf produced a body of work considered among the most groundbreaking in twentieth century literature. Her father was a literary critic, and her mother a renowned beauty and artists’ model. Her mother’s sudden death when she was 13 may have been the catalyst for the first of her recurrent nervous breakdowns.

As a young woman, Woolf developed her writer’s voice with a number of literary pursuits. She reviewed books for the Times Literary Supplement, wrote scores of articles and essays, and for a short time, taught English and history at Morley College in London (she herself had never earned a degree).

She wrote criticism and essays while her literary reputation modestly and steadily increased. Woolf started her first novel, originally titled Melymbrosia, in 1907. After seven and a half years of toil, it was finally published as The Voyage Out in 1915.

Prolific and experimental

Virginia Woolf was determined to create a new form of literature that was more internal, a savoring of experience, and a departure from traditional storytelling. Yet she was never confident. She constantly second-guessed herself, her diary filled with lines like this one from a 1919 entry: “Is the time coming when I can endure to read my own writing in print without blushing— shivering and wishing to take cover?” Upon completing works, she was most always dissatisfied.

And yet, she went on. Night and Day was published in 1919, followed by Jacob’s Room (1922). The latter was a stream of consciousness novel that, according to the Penguin Companion to English Literature, “makes no attempt to preserve the outlines of chronological events, but breaks down experience into a series of rapidly dissolving impressions that merge yet are never drowned in formlessness.”

Mrs. Dalloway (1925), perhaps one of her best-known works, takes place in one day of the main character’s life, fleshing it out in flashbacks taking place within her consciousness. In To the Lighthouse (1927), Woolf explores the concept of time and change as it relates to personality. Orlando (1928) takes the main character through several lifetimes, changing genders as he/she moves through time. Woolf’s friend and love interest Vita Sackville-West was acknowledged to be the inspiration for the character of Orlando.

The Waves (1931) is arguably the most stylized of her novels, and with The Years (1937), Woolf adopts a more traditional, less internal structure.

Orlando by Virginia Woolf: Gender and Sexuality Through Time

Hogarth Press

With her husband Leonard Woolf, she founded Hogarth Press. It started as a hobby, to print fine small editions of literary works. The press gradually grew to accommodate some notable authors from their Bloomsbury circle and beyond, and enjoyed some bestseller successes, notably, the novels of Vita Sackville-West. Some of Virginia Woolf’s novels were published by the press once it gained prestige—a case of publishing close to the vest, rather than self-publishing. She also acted as editor and sometimes marketer for the press, much to her chagrin.

Virginia Woolf wants you to write “for the good of the world”

Struggles with mental illness

It’s now widely believed that she suffered from bipolar disorder. There were scant options for treatment at this time, and so, during particularly bad bouts of mania or depression, she withdrew, unable to participate in her active social life, and found it nearly impossible, to focus on writing.

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: Manic Depression and the Life of Virginia Woolf, author and psychiatrist Peter Dally writes: “Virginia’s need to write was, among other things, to make sense out of mental chaos and gain control of madness. Through her novels she made her inner world less frightening. Writing was often agony but it provided the ‘strongest pleasure’ she knew.” Dally discerned a pattern by which Woolf appeared excited yet stable when starting a new book; then, when shaping and revising, her mood gave way to exhaustion and depression.

She referred to herself as “mad,” experiencing hallucinatory voices and visions that hinted at mental illness even above and beyond the cyclical manias and depressions. “My own brain is to me the most unaccountable of machinery—always buzzing, humming, soaring roaring diving, and then buried in mud,” she wrote in a 1932 letter. “And why? What’s this passion for?”

It was also later learned that she had endured sexual abuse at the hands of her step-brothers. More of this is detailed in Virginia Woolf: The Impact of Childhood Sexual Abuse on Her Life and Work by Louise DeSalvo.

Leonard Woolf and the Bloomsbury Circle

Virginia was nurtured by husband Leonard Woolf and beloved by her Bloomsbury colleagues. What has come to be known as the Bloomsbury Circle was a group of British colleagues that included writers, artists, critics, and intellectuals. In addition to herself and her husband, other members included her sister, Vanessa Bell, an artist, Clive Bell, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, E.M. Forester, and others.

Leonard Woolf was ever vigilant of his wife’s mental state; he cared for and protected her as best as anyone could. This was clearly a marriage of minds, if not a typical union, and there’s little doubt that he helped create the best possible scenario for her thrive and produce, under the circumstances.

Insight into the writer’s mind

Woolf left much insight into the writer’s mind as a diarist and essayist, along with her numerous books of fiction and nonfiction. She encouraged women to write about whatever fascinated them, and to dare to be dreamers and creators, as encapsulated in A Room of One’s Own, one of her best-known works of nonfiction.

Some time after his wife’s death, Leonard Woolf edited her diaries, which offer one of the most intimate glimpses available of the creative process at its finest, despite soaring highs and crashing lows. An edited version of the five-volume diaries, A Writer’s Diary, can serve as a bedside companion to anyone who wishes to witness the unfolding of genius. Eudora Welty was but one writer who felt her influence: “ Any day you open it to will be tragic, and yet all the marvelous things she says about her work, about working, leave you filled with joy that’s stronger than your misery for her. Remember— ‘I’m not very far along, but I think I have my statues against the sky’? Isn’t that beautiful?”

Death by suicide

As is well known, Virginia Woolf’s inner demons got the best of her. She walked into the river Ouse with stones in her pockets and succumbed to suicide by drowning in 1941, at the age of 59.

More about Virginia Woolf on this site

Virginia Woolf wants you to write “For the good of the world.”

Virginia Woolf — the most self-critical author of all time?

Virginia Woolf’s 1941 suicide note

Quotes on Living and Writing

Major Works

The Voyage Out (1915)

Night and Day (1919)

The Years

Jacob’s Room

The Waves

To the Lighthouse

Mrs. Dalloway

Orlando

A Room of One’s Own

Autobiographies and Biographies about Virginia Woolf

Moments of Being

A Writer’s Diary

Virginia Woolf: A Biography by Quentin Bell

Virginia Woolf: An Inner Life by Dr. Julia Briggs

Virginia Woolf by Alexandra Harris

Virginia Woolf: The Impact of Childhood Sexual Abuse

on Her Life and Work by Louise DeSalvo

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussions of Woolf’s books on Goodreads

Selected film adaptations of Virginia Woolf’s works

Orlando (1993)

Mrs. Dalloway (1998)

Visit

Monk’s House – Lewes, Sussex, UK

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Virginia Woolf appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 19, 2018

Charlotte Temple by Susanna Rowson (1790)

Charlotte Temple by Susanna Rowson (1762 – 1824, sometimes known as Susanna Haswell Rowson) was the best-known work by this American-British author. It was also America’s first best-selling novel. First published in England in 1790 as Charlotte: a Tale of Truth, it was retitled Charlotte Temple in 1797. With its classic theme of seduction and remorse, it sparked a great deal of controversy in its time. Yet it remained the most widely read novels of the first half of the nineteenth century.

Other than Charlotte Temple, Susanna Rowson’s prolific body of writings (which also included other novels as well as plays, poems, and school textbooks) has been largely forgotten. Though contemporary readers give this novel mixed reviews, judging from comments on Goodreads, Charlotte Temple has endured as an example of early American literature.

For all the novel’s faults, the following mid-twentieth re-evaluation might just tempt today’s readers to give it a try.

A 20th-century look at an 18th-century novel

From the original review in the Columbus (IN) Herald, June 6, 1958: Susanna Rowson, who wrote Charlotte Temple, had a far more romantic life story than her heroine. She was the daughter of William Haswell, an officer of the British navy. When she was eight years old she went with him to America. Their ship had wrecked off Lowell’s Island in Massachusetts. There they lived until the start of the Revolutionary War when a patriotic call of duty recalled Lieutenant Haswell to England.

Susanna was married in London in 1786 to William Rowson. In 1793 — three years after Charlotte Temple was published — she and her husband sailed to America, but the rumor that our streets were paved with gold did not prove true. William Rowson went bankrupt, after which his wife made the family living as an actress.

Susanna Rowson on the true story behind the novel

After three years of acting on the American stage, Susanna found that school teaching an writing plays and novels were more profitable and less strenuous than acting. From the amount of writing she did, she must have been an exceedingly busy woman. She herself had this to say about her most popular book:

“This is a true story. The heroine’s real name was Stanley and she was the granddaughter of the Earl of Derby. Her betrayer was Colonel John Montressor of the English Army, a relative of the author’s. Charlotte’s grave is in Trinity Churchyard, New York, but a few feet from Broadway.

Charlotte’s daughter is said to have been adopted by a rich man and afterward to to have met the son of her father, unconscious of the relationship, and to have fallen in love with him. Her identity was discovered through a miniature of the girl’s mother, the unfortunate Charlotte, to whom she herself bore a striking resemblance.”

Learn more about Susanna Rowson

The plot of Charlotte Temple

The story is about the betrayal of an innocent maiden. Charlotte, at age fifteen, is a student in an English bearing school when her friendship with her French teacher, Mlle. La Rue, leads her to secret meetings with two British officers who are about to set sail for America to take part in the Revolutionary War.

The night before she is to be allowed to go home to her family — her father is the younger son of an earl — for the celebration of her birthday, she is persuaded to go with the officer with whom she has fallen in love. He promises to marry her when they get to America.

This promise, of course, is not kept. The officer conveniently falls in love with a girl with far more money than poor Charlotte has. And though he makes arrangements for her care and protection, the man through whom these arrangements are made proves false.

Charlotte is made to suffer and pay over an over for her unhappy adventure. In the end, when her family has learned of her whereabouts and her father is hurrying to save her, she gives birth to a baby girl and dies of malnutrition.

Charlotte Temple on Amazon

Full of heavy moralizing

The plot was undoubtedly threadworn even in its day, but few writers have told it with so much suspense. Literary fashions of the late 18th century abound in the book. The ladies are forever fainting at the hint of bad news, or are thrown into hysterias. They never walk in the streets alone, but nearly always in the company of their husbands or some male relative, and they are always “hanging on his arm.”

Charlotte Temple is full of heavy moralizing, especially when concerns with seduction. The moralizing seems to take the place of the heavily sensuous background descriptions that usually soften the modern novelist’s fictional seductions. For instance:

Great heavens! when I think of the miseries that must run the heart of a doting parent when he sees his darling at first seduce from his protection, and afterwards abandoned by the very wretch whose promises of love decoyed her from her paternal roof — when he sees her, poor and wretched, her bosom torn between remorse and crime, and love for her vile betrayer …

Oh, my dear girls, for such only am I writing listen not to the voice of love, unsanctioned by paternal approbation; be assured it is now past days of romance. No woman can be run away with contrary to her own inclination; then kneel own each morning and request high heaven to keep you free from temptation. Or, should it please to suffer you to be tried, pray for fortitude to resist the impulse of inclination when it runs counter to the precepts of religion and virtue.

Trying to resist the seducer

At first, Charlotte virtuously determines never again to see Montraville, her seducer, again. And then must see him again, in order to tell him that she will not see him:

Montraville was tender, ardent, and yet respectful, we are told, and we wonder just how he managed to be so:

“Shall I not see you once more,” he said, “before I leave England? Will you not bless me by an assurance that when we are divided by a vast expanse of sea, I shall not be forgotten?”

Charlotte sighed.

“Why that sigh, my dear Charlotte? Could I flatter myself that a fear for my safety or a wish for my welfare occasioned it, how happy it would make me.”

“I shall ever wish you well, Montraville, but we must meet no more.”

“Oh, say not so, my lovely girl; reflect that when I leave my native land, perhaps a few short weeks may terminate my existence; the perils of the oceans — the dangers of war —”

“I can hear no more,” said Charlotte, in a tremulous voice. “I must leave you.”

“Say you will see me once again.”

“I dare not,” said she.

“Only for one half hour tomorrow. It is my last request and I shall never trouble you again.”

“I know not what to say,” cried Charlotte, struggling to draw her hands from him. “Let me leave you now.”

“And will you come tomorrow?”

“Perhaps I may,” said she.

Not an example of “sin and succeed”

But do not think this is any of your “sin and succeed” literature. Poor Charlotte, through her misplaced fidelity, is first neglected and then driven into the streets, with no one to befriend her. While on the other hand, the completely amoral Mlle. La Rue deliberately breaks with Montraville’s companion, and by the time they arrive in America, she has found herself a rich an respectable husband.

This hardly seems poetic justice, but on the very last page of the book, in very small print, all is made right:

It was said that ten years after these sad events that Mr. and Mrs. Temple were obliged to go to London on particular business and brought their little Lucy with them. They had been walking one morning when on their return they found a poor wretch sitting on the steps at the door. She attempted to arise as they approached, but from extreme weakness was unable, and after several fruitless efforts, fell back in a fit.

But she recovered enough to tell her story it was the former Mlle. La Rue, no longer the rich and powerful Mrs. Crayton — who had refused Charlotte help in her worst troubles — but an outcast, bent on confessing her sins:

“Come near me, Madame, I shall not contaminate you,” she tells Mrs. Temple. “I am the viper that stung your peach. I am she who turned poor Charlotte out to perish in the street.”

Looking at Lucy, she went on, “I see her now, such was the fair bud of innocence that my vile arts blasted ere it was half blown.”

The Temples, being noble-hearted people, give her food and wine, and Mrs. Temple gets her into a hospital where she soon dies, “a striking example that vice, however prosperous, in the end leads only to misery and shame.”

And there the book ends. Though we may smile at its overwrought style and hackneyed characters, it is true that today’s reader might find that once they’ve start reading, it’s a hard story to put it down.

More about Charlotte Temple by Susanna Rowson

Charlotte Temple on Librivox

Charlotte Temple on Project Gutenberg

Text of Charlotte Temple and Study Guide

Reader discussion of Charlotte Temple on Goodreads

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Charlotte Temple by Susanna Rowson (1790) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 18, 2018

Susanna Rowson

Susanna Rowson (n.d., c. 1762 – March 2, 1824) was an American-British author and actress, best known for Charlotte Temple, America’s first bestselling novel. She was born in Portsmouth, England, the only daughter of British Navy Lieutenant William Haswell and Susanna Musgrave Haswell, who died within days of giving birth to her. While stationed in Boston, her father met his second wife, with whom he had three sons. After being appointed a Boston customs officer, the family settled nearby.

The lawyer and statesman James Otis, a family friend, took a great deal of interest in Susanna’s education. From an early age, she adored books and was a precocious reader, devouring Dryden, Pope, Shakespeare, and Spenser. Otis called her his little scholar and instructed her in democratic principles.

The start of a literary career in England

During the American war of independence, the property belonging to Susanna’s father was confiscated, and for some time the family lived under house arrest. In 1778, they all returned to England, their means having been greatly reduced. Susanna worked as a governess until 1786, when she married William Rowson, a hardware merchant who not only came from a theatrical family but who also worked as a trumpeter in the royal horse guards. From all accounts, it appears that the couple had no children.

In that same year, 1786, Susanna, now known as Mrs. Rowson, published Victoria, a tale in two volumes. In 1788, she published The Inquisitor, or Invisible Rambler, a novel in three volumes. It was later reissued in Philadelphia in 1794.

Charlotte Temple

Susanna’s best-known book was the novel Charlotte: a Tale of Truth. Published in London in 1790, it was quite successful, with twenty-five thousand copies sold in a few years. It was republished in Philadelphia, Concord, and New York.

Retitled Charlotte Temple in 1797, it’s considered the first American bestseller — in fact, the bestselling American novel until Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) replaced it with that distinction. With its classic theme of seduction and remorse, it sparked a great deal of controversy in its time.

Books by and about Susanna Rowson on Amazon

Stepping on to the stage

Soon after the publication of Charlotte Temple, William Rowson went bankrupt. Despite the success of her literary work, Susanna began working as a stage actress as an additional means of livelihood. From 1792 to 1793, she, her husband, and her husband’s sister performed in Edinburgh.

In 1793 Susanna and her husband immigrated to the United States, and she continued to act until 1797. She performed in Annapolis, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. It was in Boston that she put this phase of her career to an end, performing in a well-received comedy she herself wrote — Americans in England.

New endeavors

After leaving the stage, Susanna opened The Young Ladies’ Academy, a school for girls in Boston, and returned to writing in different forms. From 1802 to 1805 she edited Boston Weekly Magazine and contributed to a number of other periodicals.

She also wrote many school textbooks, including A Spelling Dictionary (1807). Her school proved successful, and she ran in until 1822, when her health began to fail, forcing her to retire from her multi-faceted work life.

Death and legacy

Susanna Rowson died on March 2, 1824, in Boston, survived by her husband. Other than Charlotte Temple, her literary canon has not been enduring. And modern readers are far more mixed about it, judging from comments on Goodreads, than readers of its time. Though she was the author of America’s first best-selling novel, Susanna Rowson has been all but forgotten. In the 1870 A Memoir of Mrs. Susanna Rowson, its author wrote:

“Mrs. Susanna Rowson was one of the most remarkable women of her day. Her life is as romantic as any creation of her gifted pen and is a beautiful illustration of the potency of a large, glowing heart, and a determined will to rise superior to circumstances and achieve success.”

As a woman who used her literary and theatrical talent to make a living when working women were frowned upon, she deserves a great deal of respect. And though her literary style might not resonate with contemporary readers, a second look might just be in order.

Major works

Novels

Victoria (1786)

The Inquisitor (1788)

Charlotte Temple (1790)

Mentoria, or the Young Ladies’ Friend (1791, 1794)

Rebecca, or the Fille de Chambre (1792; an autobiographical novel)

Trials of the Human Heart (1795)

Reuben and Rachel, or Tales of Old Times (1798)

Sarah, or the Exemplary Wife (1802)

Charlotte’s Daughter, or the Three Orphans (1828; posthumous)

Plays and operas

The Slaves in Algiers (1794 – an opera)

The Female Patriot (1794)

The Volunteers (1795)

Americans in England (1796; later retitled Columbian Daughters)

The American Tar (1796)

Hearts of Oak (1811)

Poetry

Poems on Various Subjects (1788)

The Standard of Liberty (1795)

Miscellaneous Poems (1811)

Biographies

A Memoir of Mrs. Susanna Rowson by Elias Nason (1870)

Read and listen online

Charlotte Temple on Librivox

Charlotte Temple on Project Gutenberg

More information

Wikipedia

Text of Charlotte Temple and Study Guide

Wikisource

Britannica

Reader discussion of Charlotte Temple on Goodreads

Research

Papers of Susanna Rowson

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Susanna Rowson appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 16, 2018

How Betty MacDonald’s Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle Came to the Page

Betty MacDonald (1908 – 1958) was an American author of humorous semi-autobiographical stories and children’s books. The Egg and I, her bestselling 1942 memoir of running a chicken farm in rural Washington State in the late 1920s, catapulted her to international fame. Her Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle books for children were also hugely successful. From Paula Becker’s 2016 biography, Looking for Betty MacDonald: The Egg, the Plague, Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle, and I, here’s the story of how Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle came to the page and became a series:

As sales of The Egg and I soared, Lippincott eagerly sought to capitalize on Betty’s success. Accordingly, fifteen months after Egg made its debut, the publisher introduced Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle. The book was a collection of children’s stories about a wise, kind, magical woman who gently but firmly assisted errant children and their beleaguered parents. Betty dedicated Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle to her daughters, nieces, and nephews, “who are perfect angels and couldn’t possibly have been the inspiration for any of these stories.”

A slew of rejections, and a reversal

Lippincott nearly missed staking its claim in Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s publishing empire. While Betty was revising Egg, she had sent the children’s manuscript to her literary agent, Bernice Baumgarten, and Baumgarten had struggled without success to place it. The children’s book editors who read the stories didn’t understand Betty’s mixture of naturalism and fantasy. The publishers Bobbs-Merrill, Farrar & Rinehart, McBride’s, Messner, and Lippincott all turned the manuscript down. Once Egg began to rocket up the best-seller lists, Lippincott frantically reversed their rejection, and Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle was rushed into print.

A well-timed appearance

As with The Egg and I, Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s appearance was well timed. Children’s book sales had risen sharply during World War II, partly because toys were unavailable or in short supply, their materials being needed for wartime production. The War Production Board restrictions that affected the publishing industry most severely had been lifted by the time Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle launched. Paper and cloth were in readier supply, and children still had a keen appetite for books.

Betty’s youthful storytelling, begun at the insistent prompting of Mary’s icy feet, continued when she was a teenager spinning tales to occupy Dede and Alison. When she had children of her own, making up stories was her natural reflex, and she invented Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle for Anne and Joan.

“I have told Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle stories to children, hundreds of them, from two to twelve. Children like them because they think they are written about a sister, brother, friends, cousins, anyone but them,” Betty wrote to Lippincott’s Mac McKaughan. “I’m sure that one reason I have always loved to tell stories to children is because they are such enthusiastic audiences—they laugh loudly at anything the least bit witty, are terribly sad in the sad parts and grind their teeth with hatred for the wicked characters.”

Looking for Betty MacDonald: The Egg, the Plague, Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle, and I

is available on Amazon and the University of Washington Press

The magic of Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle

Unlike book editors, children had no trouble whatsoever accepting Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle or her world. “Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle has brown sparkly eyes and brown hair which she keeps very long, almost to her knees, so the children can comb it. . . . [Her] skin is a goldy brown and she has a warm, spicy, sugar-cookie smell that is very comforting to children who are sad about something. . . . [S]he wears felt hats which the children poke and twist into witches’ and pirates’ hats and she does not mind at all. . . . [S]he wears very high heels all the time and is glad to let the little girls borrow her shoes,” the book explained.

Among the many attractions of the book were the late Mr. Piggle-Wiggle’s hidden pirate’s treasure; the pets, Wag and Lightfoot (whose offspring were periodically divvied up among the neighborhood children); and Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s willingness to allow little boys and girls to use her house as a cozy club while they baked cookies and enjoyed cambric tea.

The role of children in the author’s life

Betty’s newspaper interviews frequently mentioned the important role that children played in her busy life. She told the Seattle Times that Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle, like The Egg and I, was written while her house “crawled with children. . . . I had so much help that I almost never got it finished. Most of my best writing has been done to the accompaniment of heavy breathing, sniffing, and fat hands poking the wrong key of the typewriter.

“I hope this book sells. If it doesn’t, it will prove that all these years I’ve been boring children instead of amusing them.” It did sell, and Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle was to become one of Betty MacDonald’s most enduring creations, appearing in Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s Magic (1949), Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s Farm (1954), and Hello, Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle (1957).

The wisdom of good behavior

Like Uncle Remus, Mary Poppins, and Nurse Matilda, Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle is an adult who helps children to learn the wisdom of good behavior. She believes that misguided children truly want to behave well once their veil of ignorance is stripped away. Children liked the books’ honestly depicted child characters and guileless acceptance of everyday magic.

Parents appreciated Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s breezy ways of presenting moral lessons and her effective solutions for behavior that was worrisome, trying, or just plain naughty. The Piggle-Wiggle books make both children and parents feel they are “in” on something. Children recognize behaviors that they themselves would never, ever exhibit (wink, wink), and feel superior, even as they identify with the child characters. Betty tosses inside jokes about parental behavior to the adults reading the books aloud.

Unlike many books written in the same era, the Piggle-Wiggle books represent boys and girls equally: both are endowed with characteristics that worry or annoy their parents, and both are equally amenable to Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s peculiar training methods.

Excerpt by Paula Becker, from Looking for Betty MacDonald: The Egg, the Plague, Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle, and I, pp. 81-83. © 2016. Reprinted with permission of the University of Washington Press.

Visit Paula Becker on the web to learn more.

You might also like: The Egg and I by Betty MacDonald

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post How Betty MacDonald’s Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle Came to the Page appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 14, 2018

8 Literary Love Affairs and Marriages

What do you get when complex, brilliant writers come together in a relationship? From the scenarios of such writers that follow, what results is both a lot of passion and almost certain complication. Some of these couples agreed on non-monogamy, while others suffered from it; some agreed that marriage wasn’t to be part of the bargain, others disdained it.

Of those listed below, only the Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning union seemed like pure bliss — though even in that case, there was a complication — her father was so dead-set against the marriage that he disinherited his daughter. Read on for a capsule of 8 famed literary love affairs and marriages — truly, for better or worse.

Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett

Lillian Hellman, the legendary American playwright, was romantically involved with Dashiell Hammett for thirty years, starting in the 1920s. Though Hammett had been married before they met, and had two daughters, neither he nor Hellman were interested in marriage or monogamy in their relationship. Hammett, a hard-drinking former detective, was best known for the detective novels, notably The Thin Man and The Maltese Falcon. One of Hellman’s impressions of Hammett from their early days:

“The white hair, the white pants, the white shirt made a straight, flat surface in the late sun. I thought: Maybe that’s the handsomest sight I ever saw, that line of a man, the knife for a nose, and the sheet went out of my hand and the wind went out of the sail …”

The couple’s relationship was on-again, off-again. When Dashiell Hammett’s lung cancer started to get the best of him in 1956, Hellman installed a bed on the library floor of her Manhattan brownstone and took care of him until his death in 1961. For more about their relationship, see When Lilly Met Dash.

Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre

Even before they’d met, Simone de Beauvoir, best known for her classic feminist text The Second Sex, was desperate to be accepted into Jean-Paul Sartre’s intellectual circle, which also included Albert Camus and Maurice Merleau-Ponty were part of this world.

Impressed by her intellect, Sartre asked to be introduced to her. Soon, they became a couple and embarked on an open relationship. While they never married, they remained together for over 50 years, connected by their intense intellectual bond. “We have pioneered our own relationship — its freedom, intimacy, and frankness,” as Simone de Beauvoir described it.

As a New Yorker article described their relationship: “They were famous as a couple with independent lives, who met in cafés, where they wrote their books and saw their friends at separate tables, and were free to enjoy other relationships, but who maintained a kind of soul marriage.”

Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway

Martha Gellhorn wrote in a variety of genres, including novels and works of nonfiction, but she became best known as a war correspondent who covered global conflicts for some 60 years. Her relationship with Ernest Hemingway began in the mid-1930s, when they traveled together to cover the Spanish Civil War.

She and Hemingway married in 1940, after his contentious split with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer. Hemingway soon became resentful of Gellhorn’s work, resenting her long journeys to cover the World War II. “Are you a war correspondent, or wife in my bed?” Apparently, she decided she was the former, especially after Hemingway tried to prevent her from going to Normandy. Notoriously restless, critical, and controlling, Hemingway had apparently met his match in Gellhorn, and he didn’t like it. They divorced in 1945.

Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf

Vita Sackville-West had a loving marriage to diplomat Nigel Nicolson. In Portrait of a Marriage, Nigel Nicolson, one of their two sons, combined his mother’s memoir with his own commentary, Vita’s love affairs with a number of women (which resulted in much drama) and Harold’s discreet relationships with men didn’t hinder the longevity of their marriage, nor and the happiness of their family. Granted, Vita’s affairs injected a good deal of drama into the relationship, and it’s possible that her passion nearly got the best of her.

The Letters of Vita Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf documents her relationship with Virginia Woolf, which began in the mid-1920s. “I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia,” wrote Vita to Virginia in a 1926 letter.“You have broken down my defenses. And I really don’t resent it …”

Though there is some debate over whether the two were actually lovers, their romantic liaison ended on good terms in 1929, and the two remained the closest of friends until Virginia’s death by suicide in 1941.

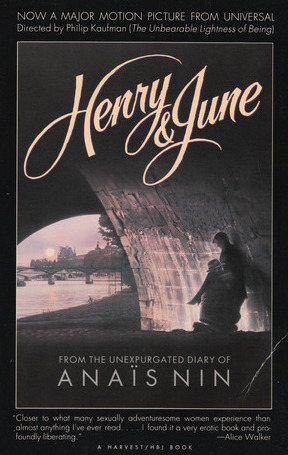

Anaïs Nin and Henry & June Miller

From late 1931 to the end of the following year, Anaïs Nin was swept into a passionate love triangle with the writer Henry Miller and his wife June. Drawn from her Paris journals, she describes the momentous year in which they were entangled. She fell in love with June’s beauty and Henry’s writing.

Soon after June’s departure for New York, Anaïs began a passionate affair with Miller. “What a superb game the three of us are playing,” she wrote. “Who is the demon? Who is the liar? Who is the human being? Who is the cleverest? Who the strongest? Who loves the most?” Learn more in Nin’s book about this episode in her life, Henry and June.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin was seventeen when she met Percy Bysshe Shelley, the writer and poet. Her father was William Godwin, a political philosopher, and Shelley was one of his followers. Mary eloped to France with Shelley, though he was already married. Her father heartily disapproved. After Shelley’s wife committed suicide, the couple married in 1816. From then on, she used the name Mary Shelley.

In the midst of her tumultuous, tragic, and romantic youth, Mary wrote Frankenstein, one of the most memorable stories of all time.

Her own story took even more tragic turns. She and Percy had five children in total, three of whom died before age three. In 1822, on an ocean voyage, Percy Shelley’s craft was lost at sea; his body was recovered days later. The loss was devastating. In an 1824 journal entry she wrote: “At the age of twenty-six I am in the condition of an aged person — all my old friends are gone … & my heart fails when I think by how few ties I hold to the world…”

Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning

Elizabeth Barrett met the love of her life, fellow poet Robert Browning, after he wrote her a fan letter of sorts. Her first collection, Poems (1844) was an immediate success in Europe and the U.S. and made her famous. A Drama of Exile: and Other Poems (1845) cemented her reputation.

It was that same year that the poet Robert Browning wrote to tell her how much he admired her work. A mutual acquaintance arranged for the two to meet, and so began one of the most intensely romantic and lasting love affairs in literary history.

Though their bond was perfectly proper, Elizabeth’s father disinherited her after their secret nuptials. The couple fled to Pisa, Italy, and she never reconciled with her family. The marriage, which produced one son, was a lasting success, immortalized by the famous sonnet by Elizabeth Barrett Browning that begins:

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes

Sylvia Plath first met fellow poet Ted Hughes at a party in Cambridge, England in 1956. They fell headlong in love and married just months later. In due time, the marriage would produce two children, though with the complex personalities involved, it was always a complicated match.

In 1962, the couple invited Canadian poets David and Assia Wevill to spend a weekend with them in their home in village of North Tawton in Devon, England. It was then, as Hughes later wrote in a poem, that “The dreamer in me fell in love with her,” and a few short weeks later he embarked on an affair with Assia.

A few months later, Plath and Hughes took a holiday in Ireland. On the fourth day, Hughes disappeared to London to meet Wevill, with whom he embarked on a 10 day trip through Spain, the same place where Plath and Hughes had honeymooned. Upon his arrival back home, the marriage unraveled when he refused to end his affair. Plath and Hughes separated in July of 1962. Read more about the tragic relationship of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 8 Literary Love Affairs and Marriages appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.