Nava Atlas's Blog, page 86

April 21, 2018

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings (August 8, 1896 – December 14, 1953) born in Washington D.C., began writing as a child. Her best known work is The Yearling, the story of a boy who adopts an orphaned fawn. It won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1939 and was subsequently made into a successful movie.

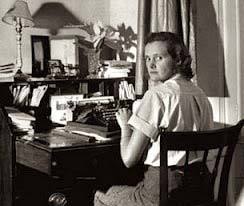

She’s also known for her writings about her adopted home in Cross Creek, Florida, where she bought an orange grove in the late 1920s and lived for many decades. She was fascinated by the people and local culture, and gathered her observations into a memoir, Cross Creek, and a compilation of recipes, Cross Creek Cookery, both published in 1942. Writing was her passion, something she did since childhood, but she often found it a torment:

“Writing is agony. I stay at my typewriter for eight hours every day when I’m working and keep as free as possible from all distractions for the rest of the day. I aim to do six pages a day but I’m satisfied with three. Often there are only a few lines to show.”

Early life

Marjorie’s father was an attorney for the U.S. Patent Office. Growing up outside Washington, D.C., the family lived on a farm. There, and in the nearby hills of Maryland and Virginia, Marjorie acquired the love of nature that would later permeate her writings. She began to sell stories under the name “Felicity” at age 11. As a teen, she had sketches and stories published in newspapers, and in 1912 won a McCalls writing contest for her piece “The Reincarnation of Miss Hetty.”

Marjorie attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison, pursuing a degree in English. She graduated in 1918, and one year later married her college sweetheart, Charles Rawlings who she described as a “big blond newspaperman who grew up on Lake Ontario and wrote about yachting.”

The two moved to Louisville, Kentucky, and both wrote for the Louisville Courier-Journal. The couple soon moved to Charles’ hometown, Rochester, New York, and they both began writing for the Rochester Journal. Rawlings had her own column at the paper, titled “Songs of the Housewife.”

While supporting herself through newspaper work she attempted to write fiction for magazines. Mostly, she collected rejections:

“I tried to write what I thought they [popular magazines] would be most likely to buy and all that brought me was rejection slips. Then in 1928 I had an opportunity to buy an orange grove in Florida and I bought it, left the newspaper and settled down to give all my time to fiction. Still the stories didn’t sell, so I gave up … But then I thought—just one more. An I wrote a story that seemed far from ‘commercial,’ that—it seemed to me—no editor would want to buy but that had meaning for me. It sold like a shot and I’ve had no trouble selling since, though I never have tried to write ‘commercially.’”

See also: Quotes by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

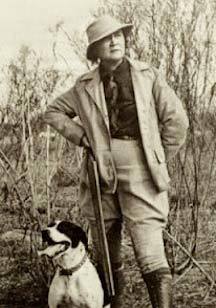

Cross Creek

In 1926, Marjorie and Charles visited his brother in the northern part of Florida, and there she had an epiphany. While out on a hunting trip, she became a bit lost, and it was a metaphor for her life.

“Sitting on a log, my gunshots unanswered, trying to think of my directions, with no life, no movement anywhere, no sound but the single note of a thrush, I became conscious of a peace, an isolation, and strangely, a safety beyond any previous experience.”

Two years later, after receiving a modest inheritance from her mother, Rawlings and her husband moved to Florida and purchased a 72-acre orange grove and farm in the north Florida hamlet of Cross Creek. She described it as “remote land of fertile hummock and unfenced pasture and ancient wood and orange grove, four miles from the nearest village.

It was during her time in Cross Creek that Rawlings would finally find herself as the writer she longed to be, but as the couple was making the move, she despaired:

“I had tried to write on the job but could not. When I came here I put all thought of popular writing behind me. I was determined to try to interpret the people I had come to love. If I failed, I would write no more.”

The orange grove was intended to support her writing, but that was a tall order. There were all sorts of challenges: Mosquitos, drunken farm hands, frosts that ruined the orange crops, termites, and wayward farm animals.

Success and upheaval

Marjorie was attracted to the eccentric locals of Cross Creek, but they were wary and at first resisted her eager questions and interest. Eventually they warmed to her, and she began recording detailed descriptions of the people, their dialect, the flora and fauna, and recipes. In 1931, after years of rejection, Scribner’s Magazine published two of her short stories, clearly inspired by Cross Creek and its residents. The pieces, “Cracker Chidlings” and “Jacob’s Ladder” were poorly received by the locals.

The year 1933 brought both success and pain for the rising author. Rawlings’ first novel, South Moon Under, was published and well received, validating her pursuit in writing about rural Florida life. It was chosen for the Book-of-the-Month Club selection and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

The recognition and income from the novel’s success brought about an opposite reaction from her husband; he grew jealous and began criticizing her work, eventually moving out. He was also sick of the rough existence on the orange grove. She filed for divorce in 1933.

After her divorce, Rawlings punged into fiction writing. She immersed herself in her surroundings, embarking on a boat trip with a friend down the Florida St. Johns River. The trip recharged Rawlings and fueled her with new ideas and inspiration for her writing. By now, it was her writing that was supporting the orange grove, rather than the other way around.

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ page on Amazon

The Yearling & Cross Creek

Perhaps recognized as Rawlings’ best-known piece of fiction, The Yearling was published in 1938. It tells the tale of a young Florida boy, Jody, and his pet deer, who he is forced to shoot after it’s caught eating his family’s crops. The Yearling was an instant bestseller and won a Pulitzer Prize in 1939.

The Yearling might now be seen as a “young adult” novel, though at the time, this wasn’t yet its own genre; yet it’s a book for all ages. The story can be read on its own merit, or seen as a parable.

In 1941, Rawlings was remarried to Norton Baskin. A year later, she published Cross Creek. In addition to the regular and book club editions, it was released in a special armed forces edition to be sent to servicemen during World War II. An autobiographical account of her relationships with her Floridian neighbors, it was followed by Cross Creek Cookery (1942). She loved to cook and entertain, finding the process a lot less painful than writing, which she sometimes described as “agony.”

In 1943, Rawlings faced a libel suit surrounding Cross Creek. It was filed by her neighbor, who felt that Rawling had insulted the family that “Jacob’s Ladder” was allegedly inspired by. Rawlings eventually won the case and enjoyed a brief moment of satisfaction, but the verdict was overturned in appellate court and she was ordered to pay damages in the amount of $1. Other than Cross Creek Cookery, no other sequel would ever be published, due to the drama surrounding the lawsuit.

You might also like: Culinary Widsom from Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

A cook at heart

Cross Creek Cookery was published in 1942, right on the heels of Cross Creek. A collection of recipes and lore reflecting the cuisine of her adopted home, some of its offerings aren’t for the feint of heart or the vegetarian-inclined. It includes recipes like ‘possum pie, alligator-tail steak, and turtle meat and eggs. Marjorie sometimes found writing a painful and laborious process, but she adored cooking.

“Food imaginatively and lovingly prepared, and eaten in good company, warms the being with something more than the mere intake of calories. I cannot conceive of cooking for friends or family, under reasonable conditions, as being a chore.”

She loved holding forth with her kitchen and entertaining tips, and you can glean some of them in her inimitable forthright style in Culinary Wisdom from Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings.

Prominent friendships

Aside from a friendship with the legendary editor Maxwell Perkins, Rawlings had friendships with fellow writers Ernest Hemingway, Robert Frost, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Margaret Mitchell, and Zora Neale Hurston. Second husband Norton Baskin later wrote of her,

“Marjorie was the shyest person I have ever known. This was always strange to me, as she could stand up to anybody in any department of endeavor, but time after time, when she was asked to go some place or to do something, she would accept only if I would go with her.”

Final novel & films

Rawlings’ last novel, The Sojourner, was published just before her death in 1953. Set in Michigan, this character study of a man and his relationship with his family was well received. Her last years were spent in a town just south of St. Augustine, Florida, where her husband owned a restaurant, but she left her heart in Cross Creek and its orange groves. As she wrote, she had merely been a tenant in a land owned by the redbirds and whippoorwills and blue jays.

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings died on December 14, 1953. She donated most of her manuscripts to the University of Florida at Gainesville, where she had briefly taught a creative writing course.

Rawlings’ Cross Creek house and farm yard were listed in the National Registry of Historic Places in1970, Today the property is designated as The Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Historic State Park.

In 1983, Cross Creek was adapted into a film starring Mary Steenburgen. The Yearling, first made into a film in 1946, was remade into a TV film in 1994.

More about Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings on this site

A Talk with Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings (1941)

Culinary Wisdom from Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

Dear Literary Ladies: Does one need connections to get published?

Major works

South Moon Under

The Yearling

The Secret River

Short Stories by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

Cross Creek

Cross Creek Cookery

The Sojourner

Biographies about Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

Selected Letters of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

Frontier Eden: The Literary Career of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

by Gordon E. Bigelow

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings: Sojourner at Cross Creek

by Elizabeth Silverthorne

More information

Wikipedia

Reader discussions of Rawlings’ books on Goodreads

Visit Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’s home

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Historic State Park

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 19, 2018

P.L. Travers

P.L. (Pamela Lyndon) Travers (August 9, 1899 – April 23, 1996) had a vivid imagination even as a child, inspired by her love of reading — fairy tales included. She’s best remembered for the Mary Poppins series of books.

Mary Poppins, one of the best-loved characters in children’s literature, came from a little story she made up while babysitting two young children. It first became a book, then a series, and the basis of the renowned 1964 Disney musical film, which greatly displeased the author. Travers wrote other children’s books, as well as books for adults, many focused on mythology.

Early life

Born Helen Lyndon Goff in Queensland, Australia, her mother was Margaret Agnes Morehead, the sister of the Premier of Queensland. Her father, Travers Goff, was an alcoholic and unsuccessful bank manager. He died when Helen was 7.

Nicknamed as Lyndon during her childhood, she moved with her sisters and mother to New South Wales in Australia after her father’s death. They were financially supported by her great aunt, who later become the inspiration for her book Aunt Sass.

Childhood woven by fairy tales

Ever the imaginative child, Travers loved fairy tales and animals, in particular birds; she often referred to herself as a hen. She had a love of Irish mythology, said to have stemmed from the stories her father told her when she was a child. During her teen years, her writing talents took flight, and eventually her poetry was published in Australian periodicals.

In the early 1920s, she was published in the literary magazine The Bulletin. It was during this time she adopted the stage name Pamela and gained a reputation as a dancer and Shakespearean actress, supporting herself as a journalist. She toured Australia and New Zealand with Allan Wilkie‘s Shakespearean Company. In 1924, she left to pursue her literary passions in England, having little support from her family to pursue a career in acting.

Her voyage to England gave her the inspiration for a series of several travel articles that she sold to Australian publications, boosting her finances to continue her pursuit as a writer.

In 1931, she and her friend Madge Burnand (playwright and the former editor of Punch, a satirical British magazine) moved from their shared flat in London to a cottage in Sussex. This is where she began to write her legacy, Mary Poppins.

P.L. Travers as Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1924

Literary career launched in England

England embraced Travers, and she began publishing articles in various papers, including poems in The Irish Statesman. The editor George William Russell, pseudonymously known as AE, took a keen interest in Travers’ writing and a friendship quickly developed.

Through her connection to Russell, she became friends with poet William Butler Yeats and studied mythology with G.I. Gurdjieff.

Mary Poppins

Mary Poppins was published in 1934 to instant success. The book kicked off a successful series with the magical nanny as the central character. In the first book, she’s blown to Number 17 Cherry Tree Lane, London by the by the East wind, and becomes part of the Banks family’s household to take care of the children. If your idea of Mary Poppins comes from how Julie Andrews portrayed her in the 1964 film, you’d be in for a surprise if you haven’t read the books. She a much darker and peppery character. Here’s how she’s described in a Classic of the Month column in the Guardian:

“Mary Poppins is not nice. She arrives, to be the nanny for the four Banks children, riding a puff of wind; she understands, and can be understood by, animals; she can take you round the world in about two minutes; and the medicine she gives you will taste like whatever your heart desires (lime-juice cordial for Jane Banks; milk for the infant Banks twins) – but a spoonful of sugar, to quote the very sugary movie, is nowhere in sight.

Mary Poppins may grant your fondest wishes, but her manner is entirely medicinal … All disapproving incomprehension, she refuses to acknowledge the magic for which she seems to be responsible — leaving the possibility wide open that the collection of more or less unconnected adventures the children have with this otherwise prosaic working-class nanny, who likes nothing better than to gaze at her reflection and admire her new gloves or hat, are nothing more than the wish fulfillment fantasies of overactive juvenile imaginations.”

The next book in the series, Mary Poppins Comes Back, came out the following year (1935), but then there would be an 8-year gap before the next, Mary Poppins Opens the Door (1943). This was followed by Mary Poppins in the Park (1952), Mary Poppins From A to Z (1962), Mary Poppins in the Kitchen (1975), Mary Poppins in Cherry Tree Lane (1982), and finally, Mary Poppins and the House Next Door (1988).

Fearing she wouldn’t be taken seriously as an author, despite the success of her Mary Poppins books, she wrote young adult novels, a play, as well as essays and lectures on mythology. In 1966, already after the highly successful Disney film was produced, she remained busy, serving as a writer-in-residence at Radcliffe College and Smith College.

In 1977, Travers was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.

See also: Quote by P.L. Travers

Disagreements with Disney

In 1964, Mary Poppins was produced into a Disney film. In 2013, the film Saving Mr. Banks starring Emma Thompson and Tom Hanks was created to tell the story of the making of Mary Poppins and the fraught relationship between Travers and Walt Disney. Here’s an excerpt from a Smithsonian Magazine article on how this “based on a true story” might have been slightly sugar-coated:

“The new movie proclaims it is ‘based on a true story,’ a cheery phrase that cleverly balances truth-telling and let’s-pretend. Saving Mr. Banks is not a documentary, but a highly entertaining feature film loosely based on the deeply antagonistic collaboration between two very strong-willed artists.”

Travers was skeptical when she was first approached by Disney in 1945. She resisted for many years, demanding the film be live action and not animated. In 1959, she finally agreed to sell the rights to Mary Poppins. But even after serving as a consultant during the production period, she was quite dissatisfied with the final film. Still, Saving Mr. Banks is an entertaining film, though it’s been said that in real life, Travers was even more of a pill than the portrayal by Emma Thompson.

P.L. Travers page on Amazon

Idle time is food for the devil

Never one to rest on her laurels, she stayed busy until the end of her life. She had plans to write Goodbye, Mary Poppins, but withdrew the proposal after an outcry from both her children audience and publishers.

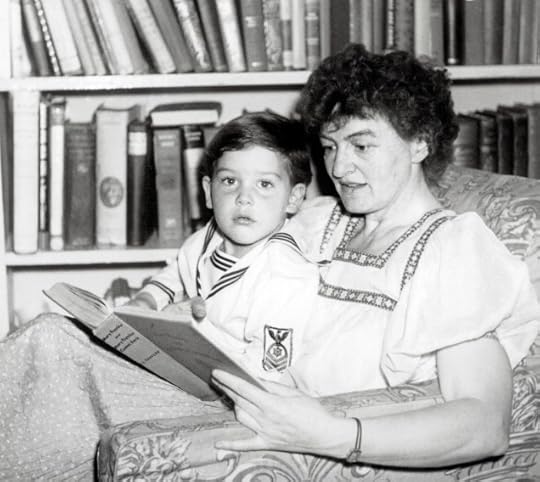

Travers never married, but adopted a son, Camillus, in 1939. He was one of twin Irish boys.

She died in London at age 96 in 1996, due to complications from an epileptic seizure.

More about P.L. Travers on this site

Quotes by P.L. Travers, author of Mary Poppins

Major Works

Mary Poppins (1934)

Mary Poppins Comes Back (1935)

Mary Poppins Opens the Door (1943)

Mary Poppins in the Park (1952)

Mary Poppins from A to Z (1962)

Mary Poppins in the Kitchen (1975)

Mary Poppins in Cherry Tree Lane (1982)

Mary Poppins and the House Next Door (1988)

What the Bee Knows: Reflections on Myth

Biographies about P.L. Travers

Mary Poppins, She Wrote: The Life of P.L. Travers by Valerie Lawson

A Lively Oracle: A Centennial Celebration of P.L. Travers by Ellen Dooling Draper

More Information

P.L. Travers on Wikipedia

P.L. Travers page on Amazon

Reader discussion of P.L. Travers works on Goodreads

Film adaptation

Mary Poppins (1964)

Visit and research

Birthplace of P.L. Travers and Mary Poppins Festival – Maryborough, Australia

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post P.L. Travers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 18, 2018

A Country Doctor by Sarah Orne Jewett (1884)

A Country Doctor by Sarah Orne Jewett is an 1884 novel by this American author noted for regional fiction set in Maine. Nan, the main character, is a young woman wants to become a doctor, something that was quite out of the ordinary at the time this novel was published.

The story follows a central character in a narrative, unlike the linked sketches in her best-known book, The Country of the Pointed Firs. But like those linked stories, it’s more episodic than plot-driven.

Jewett was inspired by her own father, who was indeed a country doctor. In her formative years, she learned about human nature by accompanying her father as he did his calls to neighboring farms and villages in South Berwick, Maine. The following review came out as the book was published in 1884, and gives a contemporaneous view of the story about a woman with the ambition to become a doctor:

Longing for a larger, freer life

From the original review in The Morning News, Wilmington, DE, June 30, 1884: A Country Doctor by Sarah Orne Jewett, is an uneventful narrative of New England life. Adeline Thatcher was one of those New England girls who are born with a distinct longing for a larger, freer life.

She left the home farm and went to one of the more considerable New England towns, became a dressmaker, married a young physician whose family prided itself upon its age and position, quarreled with the members of this family, and upon her husband’s sudden death fled with her baby to her old home, where she arrived just in time to die. It is the life of this baby girl, thus left wit her old grandmother, that occupies these pages.

Deciding to become a physician

A good country physician, who lived in the neighboring village, exercised joint moral guardianship with the grandmother over the child, and when the grandmother died the little girl was taken into his home and was educated under his wise and loving direction. Finally, when the question of her future presses upon her for settlement, she decides, not rashly nor suddenly, but as a natural consequence of many preceding circumstances, to become a physician.

Afterward she visits her father’s family, is there beset with the question of love and household life, but after some reflection and without struggle adheres to her original purpose, for the execution of which she is now fairly well trained.

A Country Doctor by Sarah Orne Jewett on Amazon

How women rightfully become physicians

This is the story. It is not an argument going to show that certain women ought to become physicians; it is rather an explanation of how women now and then rightfully do become physicians. But the charm of the book lies in the manner of doing it rather than in the thing done.

The New England farm life; the unambitious, self-contained and thoughtful life of the good doctor; the quaint, prim, and yet cheery society of old Dunport, with its delightful contrasts of home-staying, methodical women and ocean-bred, roomy-minded men; the growth of the little girl under social conditions which are in fact hard and narrow into a broad-minded, generous, resolute woman, solely through the paternal protection and intellectual companionship of the old doctor; these are the pictures and delineations of life that make the book vivid and real.

Sketches of New England peculiarities

The little episode of the evening passed in Mr. Martin Dyer’s kitchen by the brothers Jake and Martin, when their ancient prejudice led them to take down the stove and bring the old fireplace again into use, upon the exculpatory plea that the stove ought to be ready “to be carried to the corners in the morning to be exchanged or repaired,” and that “it was well to keep out the damp,” is a refreshingly quaint and genuine and humorous picture of New England peculiarities; and Marilla, the antique “girl” of Dr. Leslie’s household service that is fast disappearing, but which will always be respected by those who can perceive the actual obedience and tried fidelity underlying its unimportant assumptions of family equality.

It is these sympathetic and accurate delineations of New England life that have given Miss Jewett her reputation, and in this longer story we still find that the greater charm resides in her appreciation of and capacity to reproduce essential features in the unique and fruitful civilization of rural New England.

See also: The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah Orne Jewett

More about A Country Doctor by Sarah Orne Jewett

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Full text on American Literature

Audio version on Librivox

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing.

The post A Country Doctor by Sarah Orne Jewett (1884) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 17, 2018

The Death of Emily Brontë

Though Emily Brontë (1818 – 1848), the British author and poet, only lived to age thirty, she left the classic novel Wuthering Height, which was to be her legacy. The sister of Charlotte and Anne Brontë, she was the fifth child born to Maria Branwell Brontë and Reverend Patrick Brontë.

In many ways, Emily was a more enigmatic figure than her sisters. An 1885 article in the Chicago Tribune stated that “Emily Brontë was perhaps the most original of the Brontë children in character; and it is thought by many that she was possessed of an even more striking genius than Charlotte. She was of a peculiarly reserved nature, and never during her life made any friend outside her family.”

An 1883 biography, Emily Brontë, by Agnes Mary Frances Robinson paints a vivid portrait of Emily’s final illness and death from tuberculosis (then called consumption). Their brother Branwell had died just three months earlier (two other Brontë sisters had died in childhood), and Anne would succumb to tuberculosis about six months later, leaving Charlotte as the only surviving Brontë sibling. She too wasn’t destined for a long life.

Here’s a somewhat abbreviated portion of the chapter on the death of Emily Brontë following her illness. To read the chapter in its entirety, follow the link at the end.

An alarming cough

Already by the 29th of October of this melancholy year of 1848 Emily’s cough and cold had made such progress as to alarm her careful elder sister. Before Branwell’s death she had been, to all appearance, the one strong member of a delicate family. By the side of fragile Anne (already, did they but know it, advanced in tubercular consumption), of shattered Branwell, of Charlotte, ever nervous and ailing, this tall, muscular Emily had appeared a tower of strength.

Working early and late, seldom tired and never complaining, finding her best relaxation in long, rough walks on the moors, she seemed unlikely to give them any poignant anxiety. But the seeds of phthisis lay deep down beneath this fair show of life and strength; the shock of sorrow which she experienced for her brother’s death developed them with alarming rapidity.

The weariness of absence had always proved too much for Emily’s strength. Away from home we have seen how she pined and sickened. Exile made her thin and wan, menaced the very springs of life. And now she must endure an inevitable and unending absence, an exile from which there could be no return.

The strain was too tight, the wrench too sharp: Emily could not bear it and live. In such a loss as hers, bereaved of a helpless sufferer, the mourning of those who remain is embittered and quickened a hundred times a day when the blank minutes come round for which the customary duties are missing, when the unwelcome leisure hangs round the weary soul like a shapeless and encumbering garment. It was Emily who had chiefly devoted herself to Branwell. He being dead, the motive of her life seemed gone.

Emily Brontë’s poetry: A 19th-century analysis

Emily thought herself hardy

Had she been stronger, had she been more careful of herself at the beginning of her illness, she would doubtless have recovered, and we shall never know the difference in our literature which a little precaution might have made. But Emily was accustomed to consider herself hardy; she was so used to wait upon others that to lie down and be waited on would have appeared to her ignominious and absurd. Both her independence and her unselfishness made her very chary of giving trouble.

It is, moreover, extremely probable that she never realized the extent of her own illness; consumption is seldom a malady that despairs; attacking the body it leaves the spirit free, the spirit which cannot realize a danger by which it is not injured. A little later on when it was Anne’s turn to suffer, she is choosing her spring bonnet four days before her death. Which of us does not remember some such pathetic tale of the heart-wringing, vain confidence of those far gone in phthisis, who bear on their faces the marks of death for all eyes but their own to read?

Charlotte is worried

To those who look on, there is no worse agony than to watch the brave bearing of these others unconscious of the sudden grave at their feet. Charlotte and Anne looked on and trembled. On the 29th of October, Charlotte, still delicate from the bilious fever which had prostrated her on the day of Branwell’s death, writes these words already full of foreboding: “I feel much more uneasy about my sister than myself just now. Emily’s cold and cough are very obstinate. I fear she has pain in her chest, and I sometimes catch a shortness in her breathing when she has moved at all quickly. She looks very thin and pale. Her reserved nature occasions me great uneasiness of mind. It is useless to question her; you get no answer. It is still more useless to recommend remedies; they are never adopted.”

It was, in fact, an acute inflammation of the lungs which this unfortunate sufferer was trying to subdue by force of courage. To persons of strong will it is difficult to realise that their disease is not in their own control. To be ill, is with them an act of acquiescence; they have consented to the demands of their feeble body. When necessity demands the sacrifice, it seems to them so easy to deny themselves the rest, the indulgence. They set their will against their weakness and mean to conquer. They will not give up.

A vain struggle

Emily would not give up. She felt herself doubly necessary to the household in this hour of trial. Charlotte was still very weak and ailing. Anne, her dear little sister, was unusually delicate and frail. Even her father had not quite escaped. That she, Emily, who had always been relied upon for strength and courage and endurance, should show herself unworthy of the trust when she was most sorely needed; that she, so inclined to take all duties on herself, so necessary to the daily management of the house, should throw up her charge in this moment of trial, cast away her arms in the moment of battle, and give her fellow-sufferers the extra burden of her weakness; such a thing was impossible to her.

So the vain struggle went on. She would resign no one of her duties, and it was not till within the last weeks of her life that she would so much as suffer the servant to rise before her in the morning and take the early work. She would not endure to hear of remedies; declaring that she was not ill, that she would soon be well, in the pathetic self-delusion of high-spirited weakness.

And Charlotte and Anne, for whose sake she made this sacrifice, suffered terribly thereby. Willingly, thankfully would they have taken all her duties upon them; they burned to be up and doing. But—seeing how weak she was—they dare not cross her; they had to sit still and endure to see her labour for their comfort with faltering and death-cold hands …

“No poisoning doctor” should come near

… “No poisoning doctor” should come near her, Emily declared with the irritability of her disease. It was an insult to her will, her resolute endeavours. She was not, would not, be ill, and could therefore need no cure. Perhaps she felt, deep in her heart, the conviction that her complaint was mortal; that a delay in the sentence was all that care and skill could give; for she had seen Maria and Elizabeth fade and die, and only lately the physicians had not saved her brother.

But Charlotte, naturally, did not feel the same. Unknown to Emily, she wrote to a great London doctor drawing up a statement of the case and symptoms as minute and careful as she could give. But either this diagnosis by guesswork was too imperfect, or the physician saw that there was no hope; for his opinion was expressed too obscurely to be of any use. He sent a bottle of medicine, but Emily would not take it.

A period of hope and fear

December came, and still the wondering, anxious sisters knew not what to think. By this time Mr. Brontë also had perceived the danger of Emily’s state, and he was very anxious. Yet she still denied that she was ill with anything more grave than a passing weakness; and the pain in her side and chest appeared to diminish.

Sometimes the little household was tempted to take her at her word, and believe that soon, with the spring, she would recover; and then, hearing her cough, listening to the gasping breath with which she climbed the short staircase, looking on the extreme emaciation of her form, the wasted hands, the hollow eyes, their hearts would suddenly fail. Life was a daily contradiction of hope and fear.

The Brontë Sister’s Path to Publication

Emily still doing for herself and others

The days drew on towards Christmas; it was already the middle of December, and still Emily was about the house, able to wait upon herself, to sew for the others, to take an active share in the duties of the day. She always fed the dogs herself. One Monday evening, it must have been about the 14th of December, she rose as usual to give the creatures their supper. She got up, walking slowly, holding out in her thin hands an apronful of broken meat and bread.

But when she reached the flagged passage the cold took her; she staggered on the uneven pavement and fell against the wall. Her sisters, who had been sadly following her, unseen, came forwards much alarmed and begged her to desist; but, smiling wanly, she went on and gave Floss and Keeper their last supper from her hands.

A turn for the worse

The next morning she was worse. Before her waking, her watching sisters heard the low, unconscious moaning that tells of suffering continued even in sleep; and they feared for what the coming year might hold in store. Of the nearness of the end they did not dream. Charlotte had been out over the moors, searching every glen and hollow for a sprig of heather, however pale and dry, to take to her moor-loving sister. But Emily looked on the flower laid on her pillow with indifferent eyes. She was already estranged and alienate from life.

Nevertheless she persisted in rising, dressing herself alone, and doing everything for herself. A fire had been lit in the room, and Emily sat on the hearth to comb her hair. She was thinner than ever now — the tall, loose-jointed “slinky” girl — her hair in its plenteous dark abundance was all of her that was not marked by the branding finger of death. She sat on the hearth combing her long brown hair. But soon the comb slipped from her feeble grasp into the cinders.

She, the intrepid, active Emily, watched it burn and smoulder, too weak to lift it, while the nauseous, hateful odour of burnt bone rose into her face. At last the servant came in: “Martha,” she said, “my comb’s down there; I was too weak to stoop and pick it up.”

I have seen that old, broken comb, with a large piece burned out of it; and have thought it, I own, more pathetic than the bones of the eleven thousand virgins at Cologne, or the time-blackened Holy Face of Lucca. Sad, chance confession of human weakness; mournful counterpart of that chainless soul which to the end maintained its fortitude and rebellion. The flesh is weak. Since I saw that relic, the strenuous verse of Emily Brontë’s last poem has seemed to me far more heroic, far more moving; remembering in what clinging and prisoning garments that free spirit was confined.

The flesh was weak, but Emily would grant it no indulgence. She finished her dressing, and came very slowly, with dizzy head and tottering steps, downstairs into the little bare parlour where Anne was working and Charlotte writing a letter.

Emily took up some work and tried to sew. Her catching breath, her drawn and altered face were ominous of the end. But still a little hope flickered in those sisterly hearts. “She grows daily weaker,” wrote Charlotte, on that memorable Tuesday morning; seeing surely no portent that this—this! was to be the last of the days and the hours of her weakness.

The chord of life snapped

The morning drew on to noon, and Emily grew worse. She could no longer speak, but—gasping in a husky whisper—she said: “If you will send for a doctor. I will see him now!” Alas, it was too late. The shortness of breath and rending pain increased; even Emily could no longer conceal them. Towards two o’clock her sisters begged her, in an agony, to let them put her to bed. “No, no,” she cried; tormented with the feverish restlessness that comes before the last, most quiet peace. She tried to rise, leaning with one hand upon the sofa. And thus the chord of life snapped. She was dead.

She was twenty-nine years old. They buried her, a few days after, under the church pavement; under the slab of stone where their mother lay, and Maria and Elizabeth and Branwell …

They followed her to her grave—her old father, Charlotte, the dying Anne; and as they left the doors, they were joined by another mourner, Keeper, Emily’s dog. He walked in front of all, first in the rank of mourners; and perhaps no other creature had known the dead woman quite so well.

“We feel she is at peace”

When they had lain her to sleep in the dark, airless vault under the church, and when they had crossed the bleak churchyard, and had entered the empty house again, Keeper went straight to the door of the room where his mistress used to sleep, and lay down across the threshold. There he howled piteously for many days; knowing not that no lamentations could wake her any more. Over the little parlor below a great calm had settled.

“Why should we be otherwise than calm,” says Charlotte, writing to her friend on the 21st of December. “The anguish of seeing her suffer is over; the spectacle of the pains of death is gone by; the funeral day is past. We feel she is at peace. No need now to tremble for the hard frost and the keen wind. Emily does not feel them.”

(This is an edited version of Chapter 18 of Emily Brontë by Agnes Mary Frances Robinson. Here is the chapter in full.)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Death of Emily Brontë appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 16, 2018

Emily Brontë’s Poetry: A 19th-Century Analysis

Emily Brontë is best remembered for her haunting and passionate novel Wuthering Heights, but she has also been recognized as a brilliant poet. Among the three sisters, Emily Brontë’s poetry has been acknowledged as more skillful and moving than that of Charlotte or Anne.

In the mid-1840s, Charlotte discovered a stash of Emily’s poems and recognized the genius in them. She undertook the task of finding a home for a collaborative book of poems by herself and her two sisters. They took masculine noms de plume (Charlotte, Emily, and Anne were Currer, Ellis, and Acton, respectively, and shared the faux surname Bell).

The book, dryly titled Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell’s Poems was published in 1846 to absolutely no fanfare and humiliating sales of two copies. Charlotte wrote of her efforts in the Biographical Notice of Ellis and Acton Bell, 1850. Undeterred, Charlotte led the charge to find publishers for what were to become some of the landmark works of fiction in the English language.

Emily’s poetry has been admired and reappraised for quite some time. Following is a portion of one such insightful analysis of her poetical work by Mary Robinson, from the 1883 biography, Emily Brontë. You can link to the full article at the end of this post.

No one in the house ever saw what things Emily wrote in the moments of pause from her pastry-making, in those brief sittings under the currants, in those long and lonely watches for her drunken brother. She did not write to be read, but only to relieve a burdened heart.

“One day,” writes Charlotte in 1850, recollecting the near, vanished past, “one day in the autumn of 1845, I accidentally lighted on a manuscript volume of verse in my sister Emily’s handwriting. Of course I was not surprised, knowing that she could and did write verse. I looked it over, and something more than surprise seized me, — a deep conviction that these were not common effusions, not at all like the poetry women generally write. I thought them condensed and terse, vigorous and genuine. To my ear, they had also a peculiar music, wild, melancholy and elevating.”

Very true; these poems with their surplus of imagination, their instinctive music and irregular rightness of form, their sweeping impressiveness, effects of landscape, their scant allusions to dogma or perfidious man, are, indeed, not at all like the poetry women generally write. The hand that painted this single line …

The dim moon struggling in the sky,

… should have shaken hands with Coleridge, the voice might have sung in concert with Blake that sang this single bit of a song:

Hope was but a timid friend;

She sat without the grated den,

Watching how my fate would tend,

Even as selfish-hearted men.

“She was cruel in her fear;

Through the bars, one dreary day,

I looked out to see her there,

And she turned her face away!

Had the poem ended here it would have been perfect, but it and many more of these lyrics have the uncertainty of close that usually marks early work. Often incoherent, too, the pictures of a dream rapidly succeeding each other without logical connection; yet scarcely marred by the incoherence, since the effect they seek to produce is not an emotion, not a conviction, but an impression of beauty, or horror, or ecstasy.

The uncertain outlines are bathed in a vague golden air of imagination, and are shown to us with the magic touch of a Coleridge, a Leopardi—the touch which gives a mood, a scene, with scarce an obvious detail of either mood or scene. We may not understand the purport of the song, we understand the feeling that prompted the song, as, having done with reading ‘Kubla Khan,’ there remains in our mind, not the pictured vision of palace or dancer, but a personal participation in Coleridge’s heightened fancy, a setting-on of reverie, an impression.

Read this poem, written in October, 1845 —

The Philosopher

Enough of thought, philosopher,

Too long hast thou been dreaming

Unlightened, in this chamber drear,

While summer’s sun is beaming!

Space-sweeping soul, what sad refrain

Concludes thy musings once again?

Oh, for the time when I shall sleep

Without identity,

And never care how rain may steep,

Or snow may cover me!

No promised heaven, these wild desires

Could all, or half fulfil;

No threatened hell, with quenchless fires,

Subdue this quenchless will!

So said I, and still say the same;

Still, to my death, will say—

Three gods, within this little frame,

Are warring night and day;

Heaven could not hold them all, and yet

They all are held in me,

And must be mine till I forget

My present entity!

Oh, for the time, when in my breast

Their struggles will be o’er!

Oh, for the day, when I shall rest,

And never suffer more!

I saw a spirit, standing, man,

Where thou dost stand an hour ago,

And round his feet three rivers ran,

Of equal depth, and equal flow

A golden stream, and one like blood,

And one like sapphire seemed to be;

But, where they joined their triple flood

It tumbled in an inky sea.

The spirit sent his dazzling gaze

Down through that ocean’s gloomy night

Then, kindling all, with sudden blaze,

The glad deep sparkled wide and bright—

White as the sun, far, far more fair,

Than its divided sources were!

And even for that spirit, seer,

I’ve watched and sought my life-time long;

Sought him in heaven, hell, earth and air—

An endless search, and always wrong!

Had I but seen his glorious eye

Once light the clouds that ‘wilder me,

I ne’er had raised this coward cry

To cease to think, and cease to be;

I ne’er had called oblivion blest,

Nor, stretching eager hands to death,

Implored to change for senseless rest

This sentient soul, this living breath—

Oh, let me die — that power and will

Their cruel strife may close;

And conquered good, and conquering ill

Be lost in one repose!

You may also enjoy: No Coward Soul is Mine: 5 Poems by Emily Brontë

Some semblance of coherence may, no doubt, be given to this poem by making the three first and the last stanzas to be spoken by the questioner, and the fourth by the philosopher. Even so, the subject has little charm. What we care for is the surprising energy with which the successive images are projected, the earnest ring of the verse, the imagination which invests all its changes. The man and the philosopher are but the clumsy machinery of the magic-lantern, the more kept out of view the better.

“Conquered good and conquering ill!” A thought that must often have risen in Emily’s mind during this year and those succeeding. A gloomy thought, sufficiently strange in a country parson’s daughter; one destined to have a great result in her work.

Of these visions which make the larger half of Emily’s contribution to the tiny book, none has a more eerie grace than this day-dream of the 5th of March, 1844, sampled here by a few verses snatched out of their setting rudely enough:

On a sunny brae, alone I lay

One summer afternoon;

It was the marriage-time of May

With her young lover, June.

****

The trees did wave their plumy crests,

The glad birds carolled clear;

And I, of all the wedding guests,

Was only sullen there.

****

Now, whether it were really so,

I never could be sure,

But as in fit of peevish woe,

I stretched me on the moor,

A thousand thousand gleaming fires

Seemed kindling in the air;

A thousand thousand silvery lyres

Resounded far and near

Methought, the very breath I breathed

Was full of sparks divine,

And all my heather-couch was wreathed

By that celestial shine!

And, while the wide earth echoing rung

To their strange minstrelsy,

The little glittering spirits sung,

Or seemed to sing, to me.”

What they sang is indeed of little moment enough — a strain of the vague pantheistic sentiment common always to poets, but her manner of representing the little airy symphony is charming. It recalls the fairy-like brilliance of the moors at sunset, when the sun, slipping behind a western hill, streams in level rays on to an opposite crest, gilding with pale gold the fawn-coloured faded grass; tangled in the film of lilac seeding grasses, spread, like the bloom on a grape, over all the heath; sparkling on the crisp edges of the heather blooms, pure white, wild-rose colour, shell-tinted, purple; emphasizing every grey-green spur of the undergrowth of ground-lichen; striking every scarlet-splashed, white-budded spray of ling: an iridescent, shimmering, dancing effect of white and pink and purple flowers; of lilac bloom, of grey-green and whitish-grey buds and branches, all crisply moving and dancing together in the breeze on the hilltop. I have quoted that windy night in a line:

The dim moon struggling in the sky.

Here is another verse to show how well she watched from her bedroom’s wide window the grey far-stretching skies above the black far-stretching moors—

And oh, how slow that keen-eyed star

Has tracked the chilly grey;

What, watching yet! how very far

The morning lies away.”

Such direct, vital touches recall well-known passages in Wuthering Heights: Catharine’s pictures of the moors; that exquisite allusion to Gimmerton Chapel bells, not to be heard on the moors in summer when the trees are in leaf, but always heard at Wuthering Heights on quiet days following a great thaw or a season of steady rain.

But not, alas! in such fantasy, in such loving intimacy with nature, might much of Emily’s sorrowful days be passed. Nor was it in her nature that all her dreams should be cheerful. The finest songs, the most peculiarly her own, are all of defiance and mourning, moods so natural to her that she seems to scarcely need the intervention of words in their confession. The wild, melancholy, and elevating music of which Charlotte wisely speaks is strong enough to move our very hearts to sorrow in such verses as the following, things which would not touch us at all were they written in prose; which have no personal note. Yet listen:

Death! that struck when I was most confiding

In my certain faith of joy to be

Strike again, Time’s withered branch dividing

From the fresh root of Eternity!

Leaves, upon Time’s branch, were growing brightly,

Full of sap, and full of silver dew;

Birds beneath its shelter gathered nightly;

Daily round its flowers the wild bees flew.

Sorrow passed, and plucked the golden blossom.

Solemn, haunting with a passion infinitely beyond the mere words, the mere image; because, in some wonderful way, the very music of the verse impresses, reminds us, declares the holy inevitable losses of death.

Read the rest of this analysis on Wikisource, excerpted from Emily Brontë by Mary Robinson, 1883

The Complete Poems of Emily Brontë on Amazon

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Emily Brontë’s Poetry: A 19th-Century Analysis appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 15, 2018

The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah Orne Jewett (1896)

The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah One Jewett (1896) is considered this New England author’s finest work. Neither a novel nor traditional short stories, this book is rather a series of linked sketches of a fictional Maine seaport town called Dunnet Landing.

A quietly evocative writing style conveyed everyday events and quiet emotions, the joys as well as the inevitable losses and hardships experienced the people living in Maine’s coastal fishing villages. Crafting a portrait of a disappearing way of life with this book and the others that she wrote, Jewett helped popularize the genre of regionalism in fiction.

In that way, her work might be seen as a predecessor to the contemporary Maine author Elizabeth Strout, who used a similar device of linked tales in Olive Kitteridge.

Jewett was a mentor, colleague, and friend of Willa Cather, who admired her greatly. In 1925 (some 16 years after Jewett’s death), she wrote, “If I were asked to name three American books which have the possibility of a long, long, life, I should say at once: The Scarlett Letter, Huckleberry Finn, and The Country of the Pointed Firs. I think of no others that confront time and change so serenely. The last book seems to me fairly to shine with reflection of its long joyous future.”

More about Sarah Orne Jewett

Unfortunately, The Country of the Pointed Firs doesn’t stand among the American classics that are still read and studied. Cather modestly left out her own books that have become classics (O Pioneers!, The Song of the Lark, and My Ántonia came out the decade before she made this statement; Death Comes for the Archbishop, considered one of her finest novels, would be published in 1927).

Willa Cather did recognize that The Country of the Pointed Firs was Sarah Orne Jewett’s masterpiece. It was well regarded in its time, and it’s never too late to rediscover a worthy classic. Following is a review that captured the spirit of this book, from the year in which it was published.

An 1896 review of The Country of the Pointed Firs

From the original review of The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah One Jewett in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 6, 1896): Sarah One Jewett’s latest volume, The County of the Pointed Firs, is a delightful book. The title is attractive and you begin, thinking you have a story here, some romance of that quaint Maine coast and its people.

You read, turning page after page, charged with the dainty landscape pictures and with the half-humorous, half-pathetic, yet wholly human and natural sketches of the odd individualities which the author finds among them. You are waiting all the while for the story to begin and the plot to develop, when, lo, the end is reached, and there is no plot, only a series of bright and sunny sketches, flecked here and there, like the landscape, with bits of cloud shadows.

It is a tale of a summer spent in one of the nooks of the Maine coast, away from the currents of tourist travel. The author’s method is so entirely natural and unaffected that you do not suspect the art of it until the last leaf is turned and your are in a condition of pleased surprise to find how you have been beguiled.

The Country of the Pointed Firs on Amazon

Her quick sympathy and abiding regard for the sterling hearted, simple folk about her has helped her to catch impressions that are photographic for clearness and fidelity to nature, while her pictures are as full of warmth and color as a June day on the landlocked, island-studded bay which fronts the country of her sojourn.

There is no searching for queer characters, no straining for dialect effects. The author takes the people as she finds them, those that cross her path every day, and sets them in a series of miniatures that are wonderfully lifelike. You feel that you know them.

You are on a familiar footing with the strong-minded, masterful, yet wholly womanly Mrs. Almira Todd, and take a keen interest in her “her decoctions.” The visiting friend, Mrs. Fosdick, is another exquisite bit of character drawing, while the pictures of Mrs. Todd’s mother, the sweet, simple hearted, lovely old woman, whom you visit at her island farm home, are as fine as a nosegay of mignonette from her old-fashioned garden.

The descriptions of the mustering of the clans of the Bowden family at the old homestead, back among the hills, and of the people encountered there, the ride to and from the rendezvous in the high wagon from the Beggses, is a bit of exceptionally fine literary work, full of mental snapshots that are perfect in their realism. We do not think this author has ever done better work than she has given us in The Country of the Pointed Firs.

How The Country of the Pointed Firs begins …

I. THE RETURN

There was something about the coast town of Dunnet which made it seem more attractive than other maritime villages of eastern Maine. Perhaps it was the simple fact of acquaintance with that neighborhood which made it so attaching, and gave such interest to the rocky shore and dark woods, and the few houses which seemed to be securely wedged and tree-nailed in among the ledges by the Landing. These houses made the most of their seaward view, and there was a gayety and determined floweriness in their bits of garden ground; the small-paned high windows in the peaks of their steep gables were like knowing eyes that watched the harbor and the far sea-line beyond, or looked northward all along the shore and its background of spruces and balsam firs. When one really knows a village like this and its surroundings, it is like becoming acquainted with a single person. The process of falling in love at first sight is as final as it is swift in such a case, but the growth of true friendship may be a lifelong affair.

After a first brief visit made two or three summers before in the course of a yachting cruise, a lover of Dunnet Landing returned to find the unchanged shores of the pointed firs, the same quaintness of the village with its elaborate conventionalities; all that mixture of remoteness, and childish certainty of being the centre of civilization of which her affectionate dreams had told. One evening in June, a single passenger landed upon the steamboat wharf. The tide was high, there was a fine crowd of spectators, and the younger portion of the company followed her with subdued excitement up the narrow street of the salt-aired, white-clapboarded little town.

More about The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah Orne Jewett

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Full text of the Country of the Pointed Firs on Project Gutenberg

Audio recording on Librivox

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing

The post The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah Orne Jewett (1896) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 13, 2018

One of Ours by Willa Cather (1922) – two reviews

One of Ours by Willa Cather is a 1922 novel telling the story of Claude Wheeler, the son of a Nebraska farmer and a religious mother. He drifts through what seems to be a predictable life, devoid of purpose, until he goes to war in Europe. Though it won the 1923 Pulitzer Prize for the Novel, it received mixed reviews.

Critics panned its idealized view of World War I. Acid-penned literary legend H.L. Mencken, for example, wrote that her depiction of war “drops precipitately to the level of a serial in The Lady’s Home Journal … fought out not in France, but on a Hollywood movie-lot.”

Other critics and fellow authors, including Ernest Hemingway, who had actually seen military duty, agreed. They found her view of war as a salvation of Claude’s otherwise meaningless life to be grossly sentimentalized. One of Ours was published the same year as Three Soldiers by John Dos Passos, to which it was often compared unfavorably. Three Soldiers, also a novel, offered an anti-war perspective.

Still, with One of Ours, Willa Cather gained a greater readership, and some critics thought it was a fine piece of writing. Evidently the Pulitzer committee did as well. In a detailed essay titled Willa Cather’s One of Ours and the Iconography of War, Steven Strout noted:

“In 1987 James Woodress, Cather’s foremost biographer, claimed that the harsh response the novel provoked in several reviewers (most notably H. L. Mencken) stemmed from inattentive reading: such reviewers ‘did not read the novel carefully to see that Cather had no illusions about the war’ and ‘simply ignored the fact that the novel is told mostly from Claude’s point of view.'”

Contemporary reviews by readers on Goodreads are somewhat mixed but largely positive, so it may be interesting to revisit this lesser-known novel by one of America’s great authors. Here are two opposing views from the time the novel was published in September, 1922:

A positive review of One of Ours

From the original review in New York Herald Sun, September, 1922: Willa Cather has one of the necessary ingredients of genius––the capacity for taking infinite pains––in liberal measure. There is never anything slipshod or hasty about her work. It is several yeas since she has published a novel, and two years since her volume of short stories. Now in this she shows not only the brilliancy and power of her earlier stories but also a broader, deeper maturity.

She is dealing gravely with serious things and speaking of them out of a profound and accurate knowledge of life. If her understanding of the makeup of human creatures is not so wide in its scope as that, for example, of Mrs. Watts or Mrs. Deland, she is wise enough to keep out of unknown, or inexperienced territory.

This novel is built upon a large scale, and if there is any room for slight fault finding, it is, perhaps, a little too long. It does not drag, but is sometimes slightly overelaborated. Yet one would regret the omission of any of its incident, as it is all so good in quality even where the particular incident may be redundant. She is never prosy, but she sometimes does hold on to one note a bit longer than necessary.

The story is very definitely that of one young man. Claude Wheeler is more than a leading figure; he is overshadowingly the whole story, all the other characters being entirely subsidiary, of little importance except as they touch upon him and affect him. We are looking at life, almost all the time, through his eyes; he is done from the inside while the others are more externalized, as we see them, for the most part, also through his vision of them. It is a method that has marked advantages, especially in that it keeps the novel a unit.

The story takes Claude from his nineteenth year through his unhappy youth, his uninterrupted education, his mistaken marriage, and the war up to his gallant death in action shortly before the armistice.

He is the second son of very well to do people living on a farm near a minor town in Nebraska. His father is a man of force, but of rather course fiber; not exactly harsh or unkind, but out of sympathy with the finer things of life and capable of small cruelties which seem to him to be comic. He despises his older son, Bayliss, who is a cold, selfish, small souled and physically weak creature, but he can get on with him. He also understands his younger son, Ralph, but Claude is of a different makeup, and there is sympathy between them. Claude is not the kind to fit into any of the accepted grooves as ordained in the custom of his neighborhood. He is an idealist, but withal solid in his idealism. He aspires to something beyond the ambitions of his associates and does not feel that life is very well worth while if it means no more than earning a living.

He is sent to a small and feeble denominational college at Lincoln, and his mother is emphatically pious, a staunch believer of the old school. Not that there is anything fanatic about her, but she is incapable of understanding the mental attitude of the younger generation and fears that the State University is a godless institution, and therefore corrupting. Claude is in sullen rebellion, but at last manages to matriculate as a special student in his history at the university and begins to perk up. He also falls in with enlightening friends––of German ancestry, and some of German birth. But at that point his father decides he wants Claude at home, to run his farm.

Next comes marriage, largely due to the accident of propinquity, with the beautiful but very thin souled Enid. As the one woman who really understood something of him puts it: “If he married Enid, that would be the end. He would go about strong and heavy, like Mr. Royce (Enid’s father), a big machine with the springs broken inside.” And so it turned out. enid finally leaves him to go to China to look after a missionary sister of hers who is ill. But she has completed the wreckage of Claude’s life in most essentials.

Then comes the war, and way out for him. He finds himself, at last, in the trenches, but death is the only real release for such a spirit. Space limits forbid any detailed examination of the war chapters, but they may be recommended as one of the finest and most moving presentations of the American soldier and his reactions in France that has as yet appeared. The larger impression of America in the war is also accurate and grimly critical as well as understanding. Miss Cather knows her Nebraska and the middle Western type with its faults as well as its splendid virtues. The book is a very fine, strong piece of work.

One of Ours by Willa Cather on Amazon

A critical review of One of Ours

From the original review in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 9, 1922: Willa Cather’s One of Ours should be read in conjunction with Three Soldiers by John Dos Passos, because of the tremendous differences between the two novels, although both deal with the reactions of a soul caught in the turmoil of the great war.

Three Soldiers was criticized severely in some quarters for its raw and unpatriotic realism which laid bare the horrors and stupidities of war. That criticism was on the ground of the undesirable propaganda. On this ground no such objection can be raised to Willa Cather’s story. One of Ours shows war to be rather a beautiful thing. Its total effect is that of a recruiting pamphlet or a morale lecture by a YMCA secretary. It holds out the organized international slaughter which started in 1911 as the great event that stirred the world; that brought wider social interests to hitherto narrow souls; that gave new and interesting experiences to the dull farmer’s boy from the Middle West; that brought 2,000,000 men of Puritan America in personal contact with the great things of Europe and the Far East. It constitutes a paean of the Mad War.

As such propaganda, as a justification for the war, One of Ours must be dismissed by all but the relentless militarist or the relentless sentimentalist. There is some excuse in reason for organized war on the ground of patriotism. After all, your own country comes first and if the less-intelligent and less-civilized foreigners insist on fighting or insulting us we must be ready to fight back. We must be prepared or be annihilated. There may be a fallacy in this argument, but on the surface is has the appearance of logic.

But in One of Ours this consideration does not enter. War is found useful, however, because its “educational” value; not to the race but to the individual. Claude Wheeler has grown up on a dull farm in Iowa, has married a dull and uninspiring wife and is apparently scheduled to live the rest of his life and die in perfect dullness. He has had yearnings for better things, for a more joyous and pagan existence, but his surroundings are too much for him. The influences of a Puritan mother, of a stupid, small mid-Western community are all for property and religion and a scheme of life in which beauty and adventure are counted sinful. Internally dissatisfied, he nevertheless gives up.

And then comes the war with its larger patriotic urge. Claude enlists and becomes a lieutenant. He conducts men across the ocean and into the front line trenches. Physically miserable, he finds spiritual satisfaction in leading good men in the good fight. He lives a fuller life in 50 days than was possible in a cycle of Iowa. And he dies a glorious death.

Now, by no stretch of an elastic logic can it be argued that the case has been proven. Whatsoever may be the spiritual advantages accruing to a Claude Wheeler, these cannot ever be enough to justify a war, with its death and misery, in the lines and behind, to those for whom it was not an adventure. However much Claude Wheeler may have needed the uplifting experience, that did not justify his killing of a single stupid German for the leading to his death of a single private soldier of his own company.

Of course the truth is that war, and the army experience, has no such “educational” value as the moral lecturers would have it. The cultural levels of any army is very low and therefore could educate only those who come to it from a level of culture still lower. For that reason Willa Cather wisely picker her protagonist out of an environment of stifling stupidity. That there are many such in the country and in the world is still insufficient reason for inaugurating a general blood-letting for their entertainment and enlightenment.

As a study in the psychology of a morbid farmer’s boy who might have got more fun out of life than he did with a little more daring in his mental make-up, One of Ours makes a better showing. Willa Cather has delineated the planess, hit-or-miss progress of Claude Wheeler’s timid soul with great detail.

For this reason, the story suffers. It has little narrative compulsion about it. The tide of event drifts hither and yon and Claude Wheeler drifts with it. If he would only strike out now and again in the direction he wants to take, there would be more dramatic events, a better story. But he doesn’t. One of Ours is a well written story but of a dull life.

See also: O Pioneers! by Willa Cather

More about One of Ours by Willa Cather

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Full text of One of Ours on Project Gutenberg

Listen to One of Ours on Librivox

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post One of Ours by Willa Cather (1922) – two reviews appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 11, 2018

11 Poems by Helene Johnson

Helene Johnson (July 7, 1906 – July 7, 1995) was an African-American poet during the Harlem Renaissance. She was born in Boston and raised in Brookline, Massachusetts.

The themes of her poems explore the gender and racial politics of the era in which she wrote, primarily in the late 1920s. Following are 11 of Helene Johnson’s poems, worth reflecting on and reconsidering.

“Bottled” and “Ah My Race” are arguably her most famous poems. “Bottled” needs an introduction and context, without which it can be misconstrued. It was first published in 1927 in the May issue of Vanity Fair. Katherine R. Lynes in Project Muse offers much insight into the story behind the poem:

“In ‘Bottled,’ Johnson puts authentic and inauthentic into dialogue when she puts an imagined African jungle into a poem set on the real streets of New York City. The speaker of the poem admires the (imagined) cultural adornments and proud dancing of a man in the streets of Harlem. The speaker reports that he dances to jazz, American music that has some of its roots in Africa but is not in and of itself wholly African; she also imagines this man as he would be if he were in Africa. He functions as a cultural object in the poem, a cultural object with contested authenticities. Johnson’s use of a mixture of cultural tropes reveals her awareness of and attentiveness to theories of cultural relativism.”

Read the rest of her analysis at Project Muse.

Bottled

Upstairs on the third floor

Of the 135th Street library

In Harlem, I saw a little

Bottle of sand, brown sand

Just like the kids make pies

Out of down at the beach.

But the label said: “This

Sand was taken from the Sahara desert. ”

Imagine that! The Sahara desert!

Some bozo’s been all the way to Africa to get some sand.

And yesterday on Seventh Avenue

I saw a darky dressed fit to kill

In yellow gloves and swallow tail coat

And swirling a cane. And everyone

Was laughing at him. Me too,

At first, till I saw his face

When he stopped to hear a

Organ grinder grind out some jazz.

Boy! You should a seen that darky’s face!

It just shone. Gee, he was happy!

And he began to dance. No

Charleston or Black Bottom for him.

No sir. He danced just as dignified

And slow. No, not slow either.

Dignified and proud! You couldn’t

Call it slow, not with all the

Cuttin’ up he did. You would a died to see him.

The crowd kept yellin’ but he didn’t hear,

Just kept on dancin’ and twirlin’ that cane

And yellin’ out loud every once in a while.

I know the crowd thought he was coo-coo.

But say, I was where I could see his face,

And somehow, I could see him dancin’ in a jungle,

A real honest-to-cripe jungle, and he wouldn’t have on them

Trick clothes — those yaller shoes and yaller gloves

And swallow-tail coat. He wouldn’t have on nothing.

And he wouldn’t be carrying no cane.

He’d be carrying a spear with a sharp fine point

Like the bayonets we had “over there.”

And the end of it would be dipped in some kind of

Hoo-doo poison. And he’d be dancin’ black and naked and gleaming.

And he’d have rings in his ears and on his nose

And bracelets and necklaces of elephants’ teeth.

Gee, I bet he’d be beautiful then all right.

No one would laugh at him then, I bet.

Say! That man that took that sand from the Sahara desert

And put it in a little bottle on a shelf in the library,

That’s what they done to this shine, ain’t it? Bottled him.

Trick shoes, trick coat, trick cane, trick everything — all glass —

But inside —

Gee, that poor shine!

The Sandman

He catches dust o’ dreams to carry in his sack,

The dust a falling star leaves shining in its track,

He walks the milky-way, then down the dark-staired skies,

His tinkling footsteps hush the world with lullabies.

And when he reaches you, his fragrant gentle hands

Fill deep your drowsy eyes with fairy golden sands.

Sonnet to a Negro in Harlem

You are disdainful and magnificant—

Your perfect body and your pompous gait,

Your dark eyes flashing solemnly with hate,

Small wonder that you are incompetent

To imitate those whom you so despise—

Your shoulders towering high above the throng,

Your head thrown back in rich, barbaric song,

Palm trees and mangoes stretched before your eyes.

Let others toil and sweat for labor’s sake

And wring from grasping hands their need of gold.

Why urge ahead your supercilious feet?

Scorn will efface each footprint that you make.

I love your laughter arrogant and bold.

You are too splendid for this city street.

A Missionary Brings a Young Native to America

All day she heard the mad stampede of feet

Push by her in a thick unbroken haste.

A thousand unknown terrors of the street

Caught at her timid heart, and she could taste

The city of grit upon her tongue. She felt

A steel-spiked wave of brick and light submerge

Her mind in cold immensity. A belt

Of alien tenets choked the songs that surged

Within her when alone each night she knelt

At prayer. And as the moon grew large and white

Above the roof, afraid that she would scream

Aloud her young abandon to the night,

She mumbled Latin litanies and dream

Unholy dreams while waiting for the light.

The Road

Ah, little road all whirry in the breeze,

A leaping clay hill lost among the trees,

The bleeding note of rapture streaming thrush

Caught in a drowsy hush

And stretched out in a single singing line of dusky song.

Ah little road, brown as my race is brown,

Your trodden beauty like our trodden pride,

Dust of the dust, they must not bruise you down.

Rise to one brimming golden, spilling cry!

You might also like

Renaissance Women: 12 Female Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

Metamorphism

Is this the sea?

This calm emotionless bosom,

Serene as the heart of a converted Magdalene ––

Or this?

This lisping, lulling murmur of soft waters

Kissing a white beached shore with tremulous lips;

Blue rivulets of sky gurgling deliciously

O’er pale smooth-stones ––

This too?

This sudden birth of unrestrained splendour,

Tugging with turbulent force at Neptune’s leash;

This passionate abandon,

This strange tempestuous soliloquy of Nature,

All these –– the sea?

Poem

Little brown boy,

Slim, dark, big-eyed,

Crooning love songs to your banjo

Down at the Lafayerre —

Gee, boy, I love the way you hold your head,

High sort of and a bit to one side,

Like a prince, a jazz prince. And I love

Your eyes flashing, and your hands,

And your patent-leathered feet,

And your shoulders jerking the jig-wa.

And I love your teeth flashing,

And the way your hair shines in the spotlight

Like it was the real stuff.

Gee, brown boy, I loves you all over.

I’m glad I’m a jig. I’m glad I can

Understand your dancin’ and your

Singin’, and feel all the happiness

And joy and don’t care in you.

Gee, boy, when you sing, I can close my ears

And hear tom-toms just as plain.

Listen to me, will you, what do I know

About tom-toms? But I like the word, sort of,

Don’t you? It belongs to us.

Gee, boy, I love the way you hold your head,

And the way you sing, and dance,

And everything.

Say, I think you’re wonderful. You’re

Allright with me,

You are.

A Southern Road

Yolk-colored tongue

Parched beneath a burning sky,

A lazy little tune

Hummed up the crest of some

Softs sloping hill.

One streaming line of beauty

Flowering by a forest

Pregnant with tears.

A hidden nest for beauty

Idly flung ny God

In one lonely lingering hour

Before the Sabbath.

A blue-fruited black gum,

Like a tall predella,

Bears a dangling figure,—

Sacrificial dower to the raff, Swinging alone,

A solemn, tortured shadow in the air.

Fulfillment

To climb a hill that hungers for the sky,

To dig my hands wrist deep in pregnant earth,

To watch a young bird, veering, learn to fly,

To give a still, stark poem shining birth.

Ah My Race

Ah my race,

Hungry race,

Throbbing and young —

Ah, my race,

Wonder race,

Sobbing with song,

Ah, my race,

Careless in mirth

Ah, my veiled race,

Fumbling in birth.

He’s About 22, I’m 63

He’s about 22. I’m 63

A pity! He’s so pretty!

He runs up the stairs.

I climb step by step.

We’ve never really met, and yet

If I could stop him, what would I say?

“How’s my young man today?”

Absurd! He’d give the sweet unspecial smile

You give a sweet unspecial child.

At most, some gingham word.

He’s slightly effete, completely elite,

His grace unsurpassed, a young prince at mass.

My cardiac wheezing is frantic and panting.

He’s enchanting!

Why was he born so late,

And I so soon?

A turn of chance

The nearest happenstance,

But move, if you’re that

Upset.

Then I won’t know if I fit,

Whether to sit back and

Sit, or quit altogether.

To wit.

Do I have it, or is it gone?

Do I still belong? Can I bluff?

Suppose he turns schoolboy-tough?

Oh, it’s all too much!

Look, get his name from the mailbox

And see if he’s in the book.

Well, it won’t hurt to look.

Here it is.