Nava Atlas's Blog, page 82

July 26, 2018

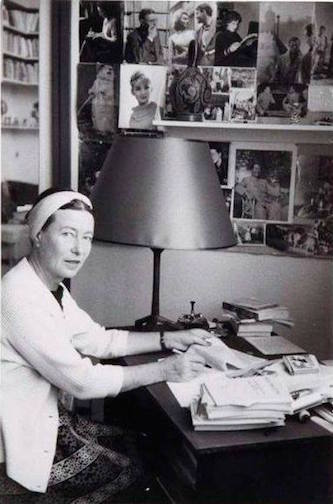

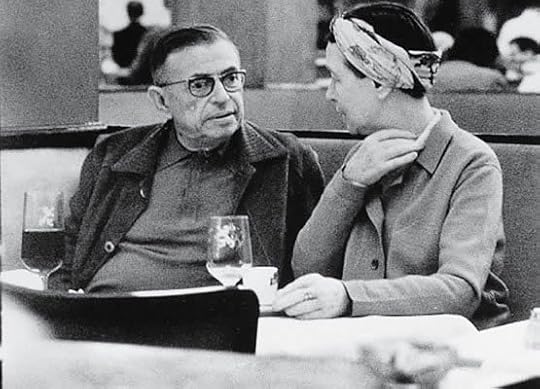

Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre: An Existential Love Story

The two intellectuals known as the mother of modern feminism and father of existentialism shared a half-century partnership that defied the conventions of their time and ours.

From 1929, when Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre met in the same elite graduate program in philosophy, to when they were buried side-by-side in the Cimetiere du Montparnasse, they shared each other’s work and lives without ever sharing a home.

The love affair

De Beauvoir and Sartre were classmates and competitors at the Sorbonne in 1929, studying for the aggregate in philosophy, a prestigious graduate degree. Although Sartre’s marks surpassed de Beauvoir’s, she was, at 21, the youngest person ever to pass the exam.

In October of that year, the two began their romantic partnership, an experiment in personal responsibility and open-heartedness. De Beauvoir, who had defied social pressures earlier in life by renouncing the Catholic faith, flouted expectation yet again by turning down a marriage proposal from Sartre.

Instead, the couple came to an agreement that rejected what they considered bourgeois hypocrisy – that is, the patriarchal expectation that married men engage in extramarital affairs and lie to their wives, who, in turn, stoically feign ignorance. Rather than pretending at monogamy, the lovers each had the freedom to pursue sexual and romantic relationships outside their own. The only condition was total transparency.

An open relationship

The pair never married or shared a home. Instead, they met daily in Parisian cafés to talk, write, edit each other’s work, and often, share details of their secondary liaisons. Their intellectual and emotional intimacy persisted for 51 years, through Sartre’s traumatic service and capture in World War II and long after the sexual component of the philosophers’ “soul marriage” had faded away.

Simone de Beauvoir, who Sartre playfully referred to as “The Beaver,” never published a piece of writing without her partner’s input until after his death. Likewise, he referred to her as a “filter” for his books, and some scholars have even made the case that she wrote some of them for him.

More about Simone de Beauvoir’s life and work

Trouble in paradise

De Beauvoir and Sartre’s partnership and unconventional relationship had high visibility within the tightly-knit social circle that was the center of both their social and professional lives. As part of the Parisian intellectual community, their circumstances created a keenly-felt pressure to present a harmonious front.

Scholars and journalists often accuse de Beauvoir of publicly masking painful bouts of jealousy. While her inner emotional life is unclear, what’s evident is the manipulative, often dishonest, and arguably cruel treatment to which both Sartre and de Beauvoir subjected much-younger female consorts.

Dangerous liaisons

Take, for example, 16-year-old Bianca Bienenfeld, a student of de Beauvoir’s who was 14 years her junior. Soon after the two women began their affair, de Beauvoir introduced her lover to Sartre. He promptly made it his mission to seduce Bienenfeld. After a romantic entanglement between the three of them, de Beauvoir told Sartre to end it, which he abruptly did in a letter.

Bienenfeld, who was Jewish, later narrowly escaped the Nazi occupation of France. Neither de Beauvoir nor Sartre tried to find her. When she read “Letters to Sartre” and saw the flippant tone the pair took toward her, she said, “Their perversity was carefully concealed beneath Sartre’s meek and mild exterior and the Beaver’s serious and austere appearance. In fact, they were acting out a commonplace version of ‘Dangerous Liaisons.’”

You might also like: Philosophical Quotes by Simone de Beauvoir

An appetite for conquest

Bienenfeld may be an extreme example, but she’s not atypical. Sartre tended to treat younger romantic prospects (all of whom were female) more as conquests than partners, spending months or years persuading them to get into bed with him and then bouncing off to regale “the Beaver” with details. He would pay his mistresses’ rent to ensure they were nearby while trying to keep them ignorant of each other. De Beauvoir was sometimes among the deceived, but at other times she was his accomplice in deception.

For her part, de Beauvoir’s outside relationships appear more amorous and tended to be longer-term. There was Nelson Algren, the American novelist, with whom she shared a decade of transatlantic love letters, addressing him as her “beloved husband.” He was a thinly veiled character in her 1954 novel, The Mandarins.

She even lived with Claude Lanzmann, a French filmmaker, for the bulk of the 1950s. But these were her relationships with men. When it came to her same-gender partnerships, de Beauvoir tended to be more exploitative. There was the painful entanglement with Bienenfeld described earlier, for example, and an affair with Natalie Sorokine, a 17-year-old student, which cost de Beauvoir her teaching license.

Iconic but flawed

If we can learn anything from looking back on Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre’s romantic lives and partnerships, it’s that an incredible intellect and a world-changing body of work don’t render a person free of flaws. The love they had for each other is as undeniable as the harm that befell many who became entangled with it.

Still, we can count among the many questions that de Beauvoir raised in her life and writing: When free of gendered and oppressive social expectations, what does love look like?

“We were two of a kind, and our relationship would endure as long as we did: but it could not make up entirely for the fleeting riches to be had from encounters with different people.” — Simone de Beauvoir, on her relationship with Sartre

— Contributed by Hannah Brown

The post Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre: An Existential Love Story appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 21, 2018

Giant by Edna Ferber (1952)

When Giant by Edna Ferber was published in 1952, some critics, especially those in the Southern U.S., weren’t impressed. In fact, the book made them hopping mad. Ferber’s books, considered by some as dramatic pot-boilers, often managed to weave in themes of racism and injustice and that didn’t sit too well in areas where racism was prevalent.

A 2011 re-evaluation of the novel in The Texas Observer had this to say: “Though it now boggles the mind, when Edna Ferber’s classic potboiler Giant was first published in 1952, it scandalized Texans from the Pecos to the Sabine. Critics ripped the novel, a hard-nosed satire of Lone Star mores, and Ferber herself to shreds in papers across the state. The Houston Press suggested she be lynched. And The Dallas Morning News headline on Lon Tinkle’s review read ‘Ferber Goes Both Native and Berserk: Parody, Not Portrait, of Texas Life.’ Reviewers outside the state also thought she’d been a trifle tough on Texas.”

It was nevertheless a huge bestseller (as were most of Ferber’s books) and in 1956 became a blockbuster film. Giant was as big and sprawling as a film as it was as a book. The saga of a wealthy Texas ranching family starred Rock Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor, and James Dean (in his final film role before his untimely death).

The book naturally received plenty of positive reviews, including the one following:

From the original review by W. W. Baker of Giant by Edna Ferber in The Kansas City Times, September, 1952: Since her first novel was published in 1911, Edna Ferber has turned her attention to such typically American matters at the show boat, small-town and farm life, and the traveling saleswoman. Now, tongue in cheek and pen in hand, she goes beyond matters American and delves into the modern-dan folklore of that strange land to the south known as Texas.

The result is Giant, a title aptly applied to the subject and to the length of the book. It tells the story of a Virginia girl (by way of Ohio) who marries a Texas ranch overlord, proprietor of a modest estate of some 2.5 million acres.

It is a well-drawn plot, with the usual Ferber niceties; the characters, though mostly of the race known as Texan, emerge as essentially human beings, as lovable or unlikable as Miss Ferber’s people usually are. The only real quarrel might be with the style of writing, about as smooth as a jeep ride over one of those Texas ranch roads; but perhaps that merely adds to the over-all effect of an essentially penetrating and understanding novel of a country made up of geographical bigness and, on occasion, human pettiness.

Giant by Edna Ferber on Amazon

A Ranch Bride

Leslie Benedict arrives at Reata ranch a bride of only a few days. There is the 50-room house in the midst of ran land heat; the filth of the Mexican dwellings; the herds of cattle, much better cared for than their Mexican cowboys; there are the neighbors, the nearest one ninety miles away, and there is Luz Benedict, her husbands unmarried sister, betrothed to the ranch and mistress of the big house.

The enormity of it all, and the conflict with Luz, stun this bookish girl from the east. Two children are born to the Benedicts, a boy as un-Texan as it is possible to be, and a girl who rides with the best of them, yet is of a different and more modern generation of Texans. Slowly the mystery of Texas penetrates Leslie’s mind, as she watches her children grow and the ranch shrink, threatened by the new get-rich-quick catalyst, oil. Her love for her husband lasts through it all, the one permanent, sustaining thing she found in this strange world.

In time Leslie begins to understand Texas and Texans, a race of men that deals in superlatives and millions, obsessed with size, not quality. In time, too, she realizes what seems to happen to the human mind and spirit; they, too, seem to shrink with the ranchland.

You may also enjoy: Show Boat by Edna Ferber (1926)

Fly a DC-6

Giant opens as the Benedicts and their friends (including an unemployed king and queen) head, in their private DC-6, for the fabulous opening-day celebration of the fabulous new Hermoso airport, built by the fabulous Jett Rink. Jett is of the new rich, a wildcatting oil baron whose story is strangely tied in with the of the Benedicts. Even here there is a last vicious triumph by Jett, who, as a penniless ranch laborer, had sworn her would get the Benedicts; then the story flashes back to Leslie’s arrival in Texas, and the events leading up to the night in Hermoso.

The characters are created as masterfully as would be expected of the writer of “Show Boat,” “So Big,” “Cimarron” and the Emma McChesney stories. Leslie herself is the inquiring intellectual, unable to accepts things on the surface as Benedict would want her to. Her husband is the blustering rancher, good at heart, yet callous to the feudal state of his Mexicans who never will earn the right to be called Texans, although their labor had done much to create Texas.

The other Benedicts – Luz, Uncle Bawley (a cattleman allergic to cattle), and the two children – are as real as a touch of Ferber irony allows to be. And there are the neighbors, ranchers described most aptly as Texans all.

Best Since “Cimarron”

Giant is probably the best Ferber production since Cimarron (1930). It’s one of four novels about Texas scheduled for autumn publication, opening up a new filed previously tapped only by the writers of cowboy fiction.

Texas, though many a citizen would deny it, is only another segment of American. Its people an customs, in fiction, should fall in live with the people and customs of other sections which go to make up the unwritable great American novel. Miss Ferber has taken a stride in the direction of making them fall in line.

On the other hand, should her strides now take her toward Texas itself, she is well advised to keep alert and avoid isolated spots and trees which support a rope. Reports from the Lone Stare state indicate a controversy over the best mode of revenge on the author, which Carl Victor Little of the Houston Press planning a hanging party on publication day next Monday, and a Beaumont Enterprise reader recommending shooting.

See also: Edna Ferber Quotes on Writing and Living

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Giant by Edna Ferber (1952) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 17, 2018

Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter by Simone de Beauvoir

Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter by Simone de Beauvoir (1959) is the first of a multi-part autobiography series by a great intellectual and literary figures of the twentieth century. It depicts her early years growing up in a bourgeois French family, her adolescent rebellion against the convention and religious doctrine, and college education at the Sorbonne. Toward the end of this memoir, she strikes out as part of an intellectual set in Paris in the 1920s, and cements her lifelong open relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre.

Simone de Beauvoir’s friendships, early lovers, teachers, and mentors come to life in this vivid portrait of a fascinating and brilliant women. It begins like this:

“I was born at four o’clock in the morning on the ninth of January 1908, in a room fitted with white-enameled furniture and overlooking the Boulevard Raspail. In the family photographs taken the following summer there are ladies in long dresses and ostrich feather hats and gentlemen wearing boaters and panamas, all smiling at a baby: they are my parents, my grandfather, uncles, aunts; and the baby is me. My father was thirty, my mother twenty-one, and I was their first child.”

Following is a review of the English translation of Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, from when it came out in the U.S.:

From the original review by John Barkham in the Tucson Daily Citizen, June 6, 1959: Both as a woman and as an intellectual, Simone de Beauvoir is very much sui generis. Men have played a part in her life, but mostly on an intellectual plane. The truth is that Simone de Beauvoir had a mind superior to that of all the men she knew — except one. That one, Jean-Paul Sartre, was destined to play a significant role in her life.

Her formidable qualities of mind and insatiable intellectual curiosity made her something of a problem to her strictly bourgeois family. In this opening volume of her autobiography — a serious, revealing, and extraordinarily vivid book — she describes in detail her years growing up in a family that would have preferred a boy.

Her parents were reasonably well-to-do Parisians, who tried to raise her as a a dutiful daughter and an obedient Catholic. Simone obliged in the first instance but her intelligence made it impossible for her to comply in the second.

You might also like:

17 Quotes from The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir

Challenging beliefs early on

The first thing that strikes the reader of this engrossing book is that its author apparently possesses powers of total recall. She can remember minute details of events that occurred when she was three years old. She was only five when her questioning mind led her to wonder why “the all-powerful Christ child should prefer to come down the chimney like a common sweep at Christmas.” Her parents felt impelled to confess the deception.

Ever since, de Beauvoir has questioned face values and challenged beliefs. During World War I she became a pacifist after seeing some of the horrors of war in her country. “Peace was more important to me than victory,” she recalled. In her teens she had been taught “the vanity of vanity, the futility of futility.” This doctrine of meek acceptance, too, she discarded.

Simone de Beauvoir page on Amazon

Meeting Sartre

As a student at the Sorbonne she began to mix with a group of brilliant left wing intellectuals, the leader of whom was Sartre. She wasn’t quite sure what she believed in, beyond the fact that she detested the extreme right. Sartre attracted her enormously. “It was the first time in my life that I had felt intellectually inferior to anyone else.”

“From now on, I’m going to take you under my wing,” Sartre told me when he had brought me the news that I had passed (Sorbonne). He had a liking for feminine friendships. During the fortnight of the oral examinations we hardly ever left each other except to sleep. I was now beginning to feel that time not spent in his company was time wasted …

“Whatever happened, I would have to try to preserve what was best in me: my love of personal freedom, my passion for life, my curiosity, my determination to be a writer. Not only did he give me encouragement but he also intended to give me active help in achieving this ambition.”

An accomplished woman

In her twenty-first year, the book ends.

It is rare indeed that a woman of Simone de Beauvoir’s attainment bares her mind and hear. Everything in these pages has, of course, been filtered through the cool detachment of her memory, but one cannot withhold admiration for her unshakable poise, her zest for new ideas, the effortless ease with which she faces every challenge from whatever quarter it may come.

Yet this is not an austere self-portrait of a bluestocking; on the contrary, it breathes life, warmth, and a desire to know.

More about Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter by Simone de Beauvoir

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Review on Whispering Gums

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter by Simone de Beauvoir appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 15, 2018

Patricia Highsmith

Patricia Highsmith (January 19, 1921 – February 4, 1995) was an American writer known for novels and short stories best described as psychological thrillers. She wove murder, crime, and intrigue through her plots, which were often driven by sociopathic antiheroes.

Born Mary Patricia Plangman in Fort Worth Texas, her parents divorced just days before her birth. She acquired the name Highsmith when her mother remarried a few years later. Recalling her unhappy childhood as “a little hell,” she disliked her mother and stepfather, who argued constantly. Perhaps that figured into her dim view of human nature, as by age eight she was reading studies of mental illness. Finding them fascinating, some of what she learned may have been tucked away for use in her writing.

Highsmith attended Barnard College in New York City, where she majored in English, focusing on playwriting and composition. For some years after graduating, she worked as a scriptwriter for comic books.

Strangers on a Train

She burst onto the the literary scene when her first novel, Strangers on a Train, was published in 1950. It was followed just a year later by the 1951 film version directed by Alfred Hitchcock. With that, her reputation was secured.

Her prolific output was dominated by thrillers that didn’t shy away from the dark places of the human psyche. She seemed to especially like creating plot lines that exposed torturous relationships between men (not in the romantic sense). She wasn’t influenced by other crime and mystery authors, preferring to get her inspiration from reading about crimes in the press.

Sociopaths, murderers, and Ripley

Sociopaths and murderers populate Highsmith’s most enduring works, which, in addition to the aforementioned Strangers on a Train, include the “Ripliad” — five novels featuring Tom Ripley, starting with The Talented Mr. Ripley. Tom Ripley is a likable sort of fellow, setting aside the fact that he murders his best friend and then goes about Europe impersonating him.

Highsmith once said, “I rather like criminals and find them extremely interesting, unless they are monotonously and stupidly brutal.

Several film adaptations emerged from that series. The first was The American Friend (1977) starring Dennis Hopper and based on Ripley’s Game. the most successful of which was the 1999 film of the same name starring Matt Damon and Jude Law. Fascinated by the criminal mind, she specialized in creating morally corrupt characters who often managed to escape punishment. “Is there anything more artificial and boring than justice?” she pondered. “I invent stories, it is not my aim to morally re-arm the reader — I want to entertain.”

Patricia Highsmith page on Amazon

The misanthrope

Highsmith was bisexual; her relationships with men and women never lasted more than a few years. She never married or had children. She was an alcoholic, and was sometimes cruel to her intimates, though plenty of people found her engaging and fascinating.

Often described as a misanthrope who preferred animals (especially cats) to people. In her 1975 collection of short stories, The Animal Lovers Book of Beastly Murders, humans are killed by animals. She was known to say, “My imagination functions much better when I don’t have to speak to people.”

The Price of Salt

Early in her career, Highsmith took a hiatus from criminals and murderers to write The Price of Salt (1952) under the pseudonym Claire Morgan. It was first time a published book about a lesbian love affair didn’t end in tragedy — quite a breakthrough for its time. The book sold nearly a million copies. Many decades after its publication, the novel has been adapted for the screen (the 2015 film version is titled Carol), and stars Rooney Mara and Cate Blanchett.

Legacy

Patricia Highsmith won numerous accolades for her work. She received awards from organizations like the Mystery Writers of America, and won the praise of fellow authors. Graham Greene described her as a “writer who has created a world of her own — a world claustrophobic and irrational which we enter each time with a sense of personal danger.” About Greene, she said: “I have Graham Greene’s telephone number, but I wouldn’t dream of using it. I don’t seek out writers because we all want to be alone.”

The London Times Literary Supplement described her in 1975 as “the crime writer who comes closest to giving crime a good name.”

Highsmith moved to Europe in 1963. She lived her later years in Italy, France, and Switzerland, and criticized Americans of being too provincial and not understanding the rest of the world. She died at age 74 in Switzerland of unknown cause.

You might also like: Romantic Quotes from The Price of Salt

More about Patricia Highsmith on this site

Romantic Quotes from The Price of Salt

Major Works (fiction)

Strangers on a Train (1950)

The Price of Salt (Claire Morgan, pseudonym, 1952)

The Blunderer (1954)

Deep Water (1957)

A Game for the Living (1958)

This Sweet Sickness (1960)

The Cry of the Owl (1962)

The Two Faces of January (1964)

The Glass Cell (1964)

A Suspension of Mercy (1965)

Those Who Walk Away (1967)

The Tremor of Forgery (1969)

A Dog’s Ransom (1972)

Little Tales of Misogyny (1974)

Edith’s Diary (1977)

The Black House (1981)

Mermaids on the Golf Course (1985)

Small g: a Summer Idyll (1995)

The Ripley Novels (known as “The Ripliad”)

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955)

Ripley Under Ground (1970)

Ripley’s Game (1974)

The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980)

Ripley Under Water (1991)

More about Patricia Highsmith

Highsmith on Wikipedia

Highsmith’s books discussed on Goodreads

The Haunts of Miss Highsmith

My Hero: Patricia Highsmith

Joan Schenkar on Patricia Highsmith (The New Yorker)

NYFF Review: Carol

Biographies

Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith by Andrew Wilson

The Talented Miss Highsmith by Joan Schenkar

Highsmith: A Romance of the 1950s by Marijane Meaker

Archive

The Patricia Highsmith Papers at the Swiss Literary Archives

Selected Film and Television adaptations

More than two dozen film adaptations have been made of Highsmith’s works. Here are a few of the best known:

Strangers on a Train (1951)

The American Friend (1977)

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999)

Ripley’s Game (2003)

Carol (adaptation of The Price of Salt, 2015)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Patricia Highsmith appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 14, 2018

Fannie Hurst

Fannie Hurst (October 18, 1889 – February 23, 1968) was a prolific American novelist and short-story writer. Though largely forgotten today, her work was hugely popular in her heyday, roughly from the 1920s through the early 1950s.

Fannie’s books and short stories featured romantic and sentimental themes, into which were woven social issues that mattered to her. Her writing made her fabulously wealthy and she was acknowledged as one of the highest-paid American writers, male or female.

Early life and career

Fannie was born and raised in Hamilton, Ohio. Her parents were Jewish immigrants from Bavaria. Her financially comfortable parents provided her with many opportunities, and encouraged her talents. Writing was her ambition from childhood. “Nothing really mattered to me except writing,” she once recalled.

She studied at Washington University in St. Louis. After graduating in 1909, she held many odd jobs including shoe factory worker, waitress, salesperson, and actress.

She married a Russian emigre named Jacques Danielson who died young. Their marriage was mostly a secret. The kind of relationship they had was coined into a phrase: “a Fannie Hurst marriage” was a marital arrangement in which the partners maintained their independent lives, including separate residences.

At the start of her writing career she contributed to magazines including the Saturday Evening Post, Century, and Cosmopolitan.

Fannie Hurst’s books on Amazon

Backstreet and Imitation of Life

Back Street (1931) is one of her many works that is arguably among her two best-remembered novels. It’s the story of a woman who devotes her life to being the mistress of a married man. It was twice adapted into a film, first in 1941, then again in 1961.

Imitation of Life (1933) was in keeping with the public debate about race and women’s roles. It’s the story of Bea Pullman, a white single mother, and her African-American maid, Delilah Johnston, also a single mother. Together, they raise their daughters and eventually become business partners. Bea’s business sense and Delilah’s southern recipes combine to form an an empire. The book and the two film versions were beloved as well as controversial.

These and some of Fannie’s novels and short stories were translated into numerous language. Her concern for the social issues woven through her stories and books spanned class, race, gender, and religious identification.

Today, most of her works are out of print and difficult to obtain, with the possible exception of Imitation of Life. It’s possible that despite their laudable themes, the kind of sentimental, tearjerking style she favored doesn’t resonate with modern readers.

From the 1999 biography Fannie by Brooke Kroeger, her career is encapsulated: “She wrote of immigrants and shop girls, love, drama, and trauma, and in no time the title ‘World’s Highest-Paid Short-Story Writer’ attached itself to her name. Hollywood fattened her bank account, making her works into films thirty-one times in forty years.”

You might also like: Conscious Quotes by Fannie Hurst

Famous friends and social activism

Fannie Hurst’s literary connections expanded during the Harlem Renaissance. She herself was Jewish (Jews weren’t exactly considered white at the time), but associated with black authors like Zora Neale Hurston. Zora first served as Fannie’s secretary and driver, and later, the two women became good friends. Fannie was also a patron to Zora, which was helpful to her. Zora was always stretched financially.

Fannie’s reputation declined through the 1950s and 1960s, and she didn’t publish nearly as much as she had earlier. Like her, Zora was virtually forgotten by the time she died, but of the two, it was Zora whose reputation was revived. Now she is revered as a literary icon, while Fannie has not been as lucky.

Fannie was a reformer (or what we call an activist today), advocating and raising money for the relief of Jews in Eastern Europe, and refugees from Nazi Germany. She served on the boards of the Committee on Workman’s Compensation (1940) and the National Housing Commission (1936 – 1937). She was a delegate to the U.N. World Health Organization and was involved in the causes of antivivisection (opposed to operating on live animals for research), workmen’s compensation, among others.

Later years and legacy

Fannie Hurst died in February of 1968 after a brief illness at the age of 78. She was still living in one of the spoils of her lucrative career, a triplex apartment overlooking Central Park in New York City.

At the height of her career she was best known for her novels and short stories, though she also wrote plays and essays. She was known for her personal sense of style, too. Her raven hair and ivory skin gave her a distinctive look. She always added a calla lily with whatever ensemble she dressed in; it became a trademark of sorts.

Having no heirs, she left half of her estate to her alma mater, Washington University, and the other half to Brandeis University. These institutions used the money to endow English department professorships.

Though she was still writing until the end, her stamina and reputation had waned. Unfairly, some of her work was called “trash,” and some critics even conjectured that her work influenced novelists like Jacqueline Susann and Jackie Collins.

Renewed interest in Fannie Hurst has focused on her Jewish background and social consciousness. In the 1990s, her life and work again started to gain serious critical attention. A full-scale biography by Brooke Kroeger was published in 1999, and in 2004, a collection of her stories was published by the Feminist Press to “propel a long overdue revival and reassessment of Hurst’s work,” praising her “depth, intelligence, and artistry as a writer.”

More about Fannie Hurst on this site

Fannie Hurst & Zora Neale Hurston — a Literary Friendship

Conscious Quotes by Fannie Hurst

What goes through your mind when you’re feeling blocked?

Major Works

Short Story Collections

Just Around the Corner (1914)

Every Soul Hath Its Song (1916)

Gaslight Sonatas (1918)

Humoresque: A Laugh on Life with a Tear Behind It (1919)

The Vertical City (1922)

Song of Life (1927)

Procession (1929)

We are Ten (1937)

Novels (Selected)

Star-Dust: The Story of an American Girl (1921)

Lummox (1923)

Appassionata (1926)

A President is Born (1928)

Five and Ten (1929)

Back Street (1931)

Imitation of Life (1933)

Anitra’s Dance (1934)

Great Laughter (1936)

Lonely Parade (1942)

Hallelujah (1944)

The Hands of Veronica (1947)

Anywoman (1950)

God Must Be Sad (1961)

Fool, Be Still (1964)

Biographies and Autobiographies

Fannie: The Talent for Success of Writer Fannie Hurst by Brooke Kroeger

Anatomy of Me: A Wonderer in Search of Herself by Fannie Hurst

More Information

Wikipedia

Jewish Women’s Archive

The ‘Anatomy’ of Fannie Hurst

Reader discussion of Fannie Hurst’s books on Goodreads

Film adaptations (selected)

Back Street (1941)

Back Street (1961)

Imitation of Life (1934)

Imitation of Life (1959)

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Fannie Hurst appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 12, 2018

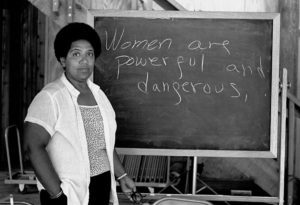

Audre Lorde

Audre Geraldine Lorde (February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) was a self-identified “black lesbian, mother, warrior, poet.” The daughter of West Indian parents, she grew up in New York City. Her love of writing took root at an early age, and she was first published in Seventeen magazine while in high school.

As society progressed with the anti-war, feminist, and civil rights movements, Audre shifted her writing from themes of love to more political and personal matters. She used her platform as a writer to spread ideas about intersecting oppressions and experiences faced especially by women of color.

Early life

Audre Lorde was born to Caribbean immigrant parents in New York City’s Harlem, the youngest of three daughters. By the time she was in eighth grade, she wrote her first poem, despite being so nearsighted that she was legally blind. It was around this time that she dropped the ‘y’ from her birth name, which she explains in her autobiography Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, where she expresses preferring the symmetry of Audre Lorde, a name with two ‘e’-endings.

Having grown up with a rather cold and distant relationship with her parents, Audre turned to poetry to express her emotions. Her difficult relationship with her mother is represented in her later poems such as “Story Books on a Kitchen Table.”

Continuing to express herself through poetry and the arts, Audre Lorde later became the editor of her school magazine at Hunter College High School, a secondary school for intellectually gifted children. When a faculty member rejected a sonnet she’d written about love, she pitched it to Seventeen magazine. They accepted and published it, paying her more than she would make over next decade of her writing career.

Education and start of an academic career

In 1954, Audre spent a year studying at the National University of Mexico, a pivotal time in the poet’s life. It was then that she publicly confirmed her identity as a lesbian and a poet. Upon her return to New York, she attended Hunter College and graduated in 1959. She worked as a librarian and continued writing while earning her master’s degree in library science at Columbia University, graduating in 1961.

In 1968, as a writer-in-resident at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, Audre had another transformative year as an artist. She held workshops with her black undergraduate students, leading discussions in civil and gay rights issues. This was in part the inspiration her book of poetry, Cables to Rage.

In 1970, Audre taught as an English professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. During her eleven years at the college, she fought for the creation of a Black Studies department. In 1981, she began teaching at her undergraduate alma mater, Hunter College.

Photo by Robert Alexander/Archive Photos/Getty Images

See also: Five Politically-Inspired Poems by Audre Lorde

Accomplished warrior

In 1977, Audre Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer, undergoing surgery and later a mastectomy. She kept a detailed journal of her battle with cancer in her prose, The Cancer Journal, published in 1980.

A true warrior at heart, she continued to accomplish much in her life, using her voice and art to fight for what she believed in. In 1981, she became one of the founders of the Women’s Coalition of St. Croix, an organization dedicated to assisting women who have survived sexual abuse. In the late 1980’s, she also helped establish Sisterhood in Support of Sisters in South Africa to benefit black women affected by injustice.

Sponsored by The Black Scholar and the Union of Cuban Writers, Audre Lorde was a part of a group of black female writers invited to Cuba in 1985. Post-Cuban revolution, they discussed whether the status of people of color, lesbians, and gays had truly changed.

The Berlin Years

In 1984, Lorde started a visiting professorship in West Berlin at the Free University of Berlin. During her time in Germany, Lorde became an influential part of the Afro-German movement of that time. Together with a group of black female activists in Berlin, Audre Lorde coined “Afro-German” and gave significant rise to the Black movement in Germany.

Her impact on the movement was highlighted in the documentary Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984-1992. The film was entered into the Berlin Film Festival, and continued to be viewed at festivals as recently as 2016.

A prolific poet

Lorde contributed poetry to many periodicals, anthologies, and other types of books. Some of her accomplishments include founding both the Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press in the late 1980’s with Barbara Smith. She also received multiple awards, including the Walt Whitman Citation of Merit, a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts (1981) and multiple National Book Awards.

A battle with cancer

Audre Lorde eventually succumbed to her battle with breast cancer on November 17, 1992 in St. Croix, U.S.Virgin Islands. Ever the powerful woman, she found inspiration throughout her battle, documented in the 1980 special edition issue of the Cancer Journals. Her story included a feminist analysis of her experience with the disease and her mastectomy.

Before passing away, she changed her name to Gambda Adisa which means “Warrior,” or “she who makes her meaning known.”

You may also enjoy: Poetry and Politics: Quotes by Audre Lorde

More about Audre Lorde on this site

Poetry & Politics: Quotes by Audre Lorde

5 Reasons to Love Audre Lorde

Five Politically-Inspired Quotes by Audre Lorde

10 Thought-Provoking Quotes from Sister Outsider

Major Works

Our Dead Behind Us (1986)

The Black Unicorn (1978)

A Burst of Light (1988)

Coal (1976)

New York Head Shop and Museum (1974)

From a Land Where Other People Live (1973)

The Cancer Journals

Sister Outsider

Autobiographies, Biographies, and Literary Criticism

Audre Lorde: Radical Feminist, Writer & Civil Rights Activist

Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde

More Information

Wikipedia

Audre Lorde: The Poetry Foundation

The Audre Lorde Project

Poets.org

Illinois University Publication

The Lorde Concordance: A Traveling Resurrection of Audre (Our) Lorde

Research

Audre Lorde Berlin: An Online Journey

Audre Lorde Archive: JFK Institute

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Audre Lorde appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 11, 2018

Wise Blood by Flannery O’Connor (1952)

Wise Blood by Flannery O’Connor, first published in 1952, was this author’s first novel. Followed by The Violent Bear it Away, a novel, and A Good Man is Hard to Find, a collection of short stories, it was reissued in a new hardcover in 1962 as a nod how much O’Connor’s audience had grown in the intervening years.

O’Connor was best known for fiction (primarily short stories) in the form of morally driven narratives populated with flawed characters sometimes described as grotesque. As she herself reminded readers in her essay “The Teaching of Literature”:

“The freak in modern fiction is usually disturbing to us because he keeps us from forgetting that we share in his state. The only time he should be disturbing to us is when he is held up as a whole man.”

This review of Wise Blood from the date of its reissue in 1962, takes note of this, and assures readers that if they had already read the book, a second look would be rewarding:

Adapted from the August 24, 1962 edition of Oakland Tribune: Wise Blood unquestionably deserves a second reading. As a first effort, it has several uncommon qualities. Among them is a sense of economy and selection in the writing. We aren’t asked to ferret out the promising passages from the masses of tedious verbiage.

No less effective is the author’s artistic objectivity and her ability to create a small world and people it with creatures of the imagination. Miss O’Connor’a prose is never excessive, always maintaining a sort of tough precision.

See also A Good Man is Hard to Find: An Analysis

If Miss O’Connor has artistic debts as a writer, they are to Sherwood Anderson. Her novel is filled with a gallery of fascinating grotesques. And while they perhaps do not have the largeness of the citizens of Winesburg, Ohio, they are a haunting lot.

Introducing Hazel Motes

The central figure of Wise Blood is a young man from Tennessee named Hazel Motes. At twenty-two, Hazel is released from the Army and goes to a Southern town to make his way. The obsession that has bade a grotesque figure of Hazel is a religious one. Outwardly, he tries valiantly to deny Christ in a particularly violent way.

Standing on the hood of his ancient car, he loudly addresses unsuspecting crowds as they leave movie theaters. Hazel declares that he is the preacher of a new and different sort of religion, a “Church without Christ.” But he is unable to find converts, and his obsessive denial of Christ — always in fierce battle with his hidden need to return to the conventional teachings of his childhood — takes more violent forms.

Wise Blood by Flannery O’Connor on Amazon

The religious charlatan Asa Hawks

At large in the city, Hazel meets Asa Hawks, a religious fanatic who feigns blindness, and his predatory daughter, Sabbath. Although Hazel believes himself completely at odds with the Christian doctrines of Hawks, he finds himself irresistibly drawn to the old charlatan and his daughter.

Hazel finds another friend of sorts in Enoch, who loves to browse at lengths in supermarkets inspecting the labels of the canned goods and reading the picture stories on the backs of cereal boxes. Enoch is a guard at the city zoo and his great need to belong to the human community brings him to some grimly comic actions. Like those of Hazel, Enoch’s pathetic efforts often evoke a kind of grotesque comedy.

Flannery O’Connor’s people are not drawn from life in the manner with which we are most familiar. Yet in another way they are, for in the authors hands they embody more than the characteristics of individuals. Wise Blood is an unusual and highly satisfying reading experience.

A review of

The Violent Bear it Away by Flannery O’Connor

More about Wise Blood by Flannery O’Connor

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Sin and Symbolism in Wise Blood

The Grotesque in Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Wise Blood by Flannery O’Connor (1952) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 6, 2018

Quotes From Kindred by Octavia E. Butler

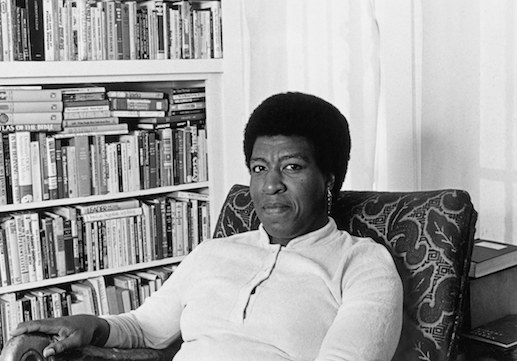

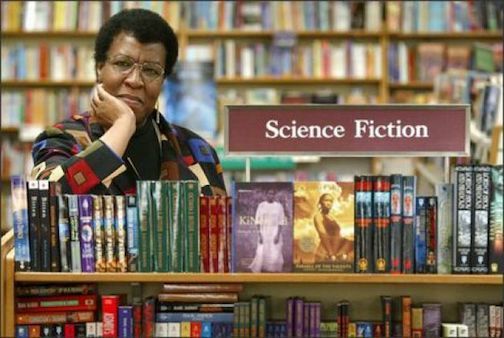

Octavia E. Butler (1947 – 2006) was an American author of science fiction. In the white male-dominated genre of science fiction, she broke ground not only as a woman, but as an African-American.

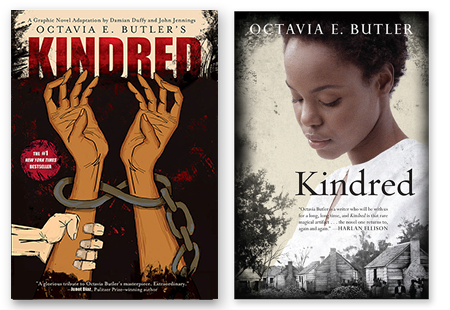

After publishing some short stories, Octavia Butler’s first novel was Patternmaster (1976). It was the first in what would become a four-volume series. But it was Kindred (1979) that really put Octavia Butler on the literary map. It follows the tale of Dana, a contemporary African-American woman who travels back in time to save an ancestor who happens to be a white slave owner. By saving him in his time, she ensures her own survival in the future. Following is a selection of quotes from Kindred, showcasing Octavia Butler’s keen observations of human nature:

“Better to stay alive,” I said. “At least while there’s a chance to get free.” I thought of the sleeping pills in my bag and wondered just how great a hypocrite I was. It was so easy to advise other people to live with their pain.”

“Repressive societies always seemed to understand the danger of ‘wrong’ ideas.”

“…I realized that I knew less about loneliness than I had thought — and much less than I would know when he went away.”

“I’d rather see the others.”

“What others?”

“The ones who make it. The ones living in freedom now.”

“If any do.”

“They do.”

“Some say they do. It’s like dying, though, and going to heaven. Nobody ever comes back to tell you about it.”

You may also like: 12 Fast Facts About Octavia Butler

“As a kind of castaway myself, I was happy to escape into the fictional world of someone else’s trouble.”

“Frankly, it never occurred to me that I needed someone who looked like me to show me the way. I was ignorant and arrogant and persistent and the writing left me no choice at all.”

“ … slavery of any kind fostered strange relationships. Only the overseer drew simple, unconflicting emotions of hatred and fear when he appeared briefly. But then, it was part of the overseer’s job to be hated and feared while the master kept his hands clean.”

“Nothing in my education or knowledge of the future had helped me to escape. Yet in a few years an illiterate runaway named Harriet Tubman would make nineteen trips into this country and lead three hundred fugitives to freedom.”

“She was strange now, erratic, sometimes needing my friendship, trusting me with her dangerous longings for freedom, her wild plans to run away again; and sometimes hating me, blaming me for her trouble. One.”

See also: Parable of the Sower & Parable of the Talents by Octavia Butler

“Sometimes I wrote things because I couldn’t say them, couldn’t sort out my feelings about them, couldn’t keep them bottled inside me.”

“I didn’t want to depend on someone else’s chance violence again — violence that, if it came, could be more effective than I wanted.”

“I got caught up in one of Kevin’s World War II books — a book of excerpts from the recollections of concentration camp survivors. Stories of beatings, starvation, filth, disease, torture, every possible degradation. As though the Germans had been trying to do in only a few years what the Americans had worked at for nearly two hundred … Like the Nazis, antebellum whites had known quite a bit about torture – quite a bit more than I ever wanted to learn.”

“I’m not sure it’s possible for a lone black woman — or even a black man — to be protected in that place.”

The Theme of Survival in Kindred

“In fact, [the South Africans] were living in the past as far as their race relations went. They lived in ease and comfort supported by huge numbers of blacks whom they kept in poverty and held in contempt.”

“Was that why I was here? Not only to insure the survival of one accident-prone small boy, but to insure my family’s survival, my own birth.”

“He was like me – a kindred spirit crazy enough to keep on trying.”

“He had already found the way to control me – by threatening others.”

“Slavery is a long slow process of dulling.”

‘Strength. Endurance. To survive, my ancestors had to put up with more than I ever could. Much more.”

“And I began to realize why Kevin and I had fitted in so easily into this time. We weren’t really in. We were observers watching a show. We were watching history happen around us. And we were actors. While we waited to go home, we humored the people around us by pretending to be like them. But we were poor actors. We never really got into our roles. We never forgot that we were acting.”

You may also enjoy:

Octavia Butler Quotes on Writing and Human Nature

“She had done the safe thing — had accepted a life of slavery because she was afraid. She was the kind of woman who might have been called ‘mammy’ in some other household. She was the kind of woman who would be held in contempt during the militant nineteen sixties.”

“I had seen people beaten on television and in the movies. I had seen the too-red blood substitute streaked across their backs and heard their well-rehearsed screams. But I hadn’t lain nearby and smelled their sweat or heard them pleading and praying, shamed before their families and themselves. I was probably less prepared for the reality than the child crying not far from me. In fact, she and I were reacting very much alike.”

“I felt as though I were losing my place here in my own time. Rufus’s time was a sharper, stronger reality. The work was harder, the smells and tastes were stronger, the danger was greater, the pain was worse.”

The post Quotes From Kindred by Octavia E. Butler appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 2, 2018

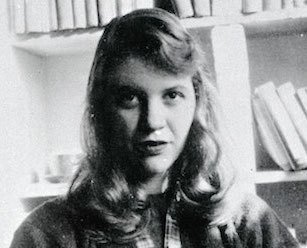

Fascinating Facts About Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath (1932 – 1963) was a gifted poet who on the surface seemed to have it all: ambition, brains, and beauty. But she was beset by a lifelong struggle with depression that led to suicide at the age of thirty.

Because most of her work was published after her untimely death, she wasn’t able to enjoy the fruits of her labors. Yet her place in the American literary canon is well deserved. Here are some facts about Sylvia Plath, some known well, others less so, but all contributing to a fascinating portrait of this beloved poet’s brief life:

She published her first poem at age 9

A week after her eighth birthday, Plath’s father died from complications due to a foot amputation. In the same year, she published her first poem in the Boston Herald’s children’s section. Over the course of the next few years, she continued to publish multiple poems in regional magazines and newspapers. Her first published poem was called “Poem” (Boston Herald, 1941)

“Hear the crickets chirping

In the dewy grass.

Bright little fireflies

Twinkle as they pass.”

She first pursued studio art

When Sylvia Plath initially enrolled at Smith College, her first choice of major was studio art, but after discovering her brilliance in writing, her professors encouraged her to major in English instead. The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery mounted a retrospective of her work in 2017.

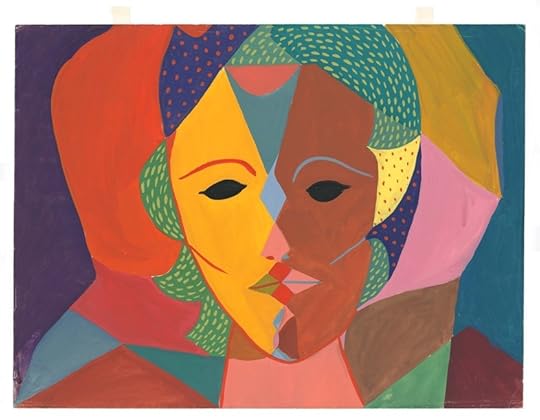

Triple-Face Portrait by Sylvia Plath, c. 1950-1951

Courtesy The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana,

© Estate of Sylvia Plath

She went missing while a student at Smith

In 1950, Plath began attending Smith College and at first, seemed to flourish. She edited The Smith Review, and during the summer after her third year of college was awarded a coveted position as guest editor at Mademoiselle magazine, spending a month in New York City. The experience wasn’t what she had hoped, and it began a downward spiral. Plath made her first suicide attempt in 1953 by crawling under her house and taking her mother’s sleeping pills.

She survived this first suicide attempt after lying unfound in a crawl space for three days, later writing that she “blissfully succumbed to the whirling blackness that I honestly believed was eternal oblivion.” The incident was reported in local papers, reporting her disappearance and recovery:

She was a guest editor for Mademoiselle

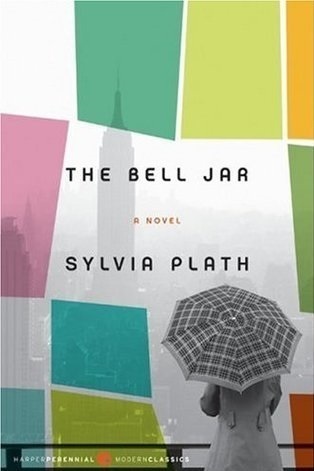

In August of 1952, Sylvia Plath won a fiction writing contest held by Mademoiselle, the New York City based women’s magazine, earning her the position as guest editor in June 1953. Her experiences during this time in NYC later became an episode in her novel The Bell Jar (1963).

She married Ted Hughes less than four months after meeting him

Plath first met poet Ted Hughes on February 25, 1956, at a party in Cambridge, England. She was there on a prestigious Fulbright Scholarship. The couple married on June 16, 1956, and honeymooned in Benidorm, Spain.

The following year, Plath and Hughes moved to the Massachusetts, where she taught at her alma mater, Smith College. It was a challenge for her to find the time and energy to write when she was teaching. By the end of 1959 after another move and extensive travel, the couple moved back to London.

She was a secret collage artist

Although often associated with a darker, perhaps more dramatic spirit, Sylvia Plath also had a wry sense of humor, evidenced in her collages. She would create visual art out of anything she could find, including the American magazines her mother mailed to her in England.

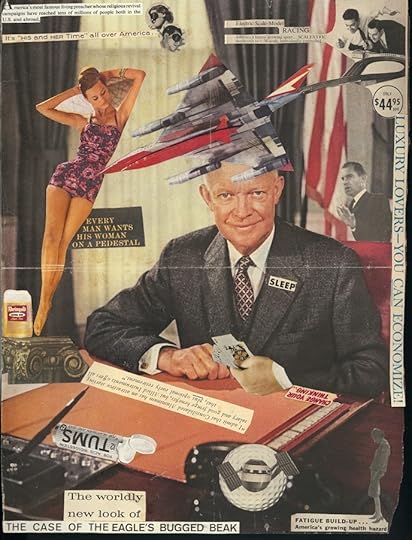

Collage by Sylvia Plath

Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College,

Northampton, Massachusetts, © Estate of Sylvia Plath

The Bell Jar was first published under a pseudonym

The Bell Jar was published in England just prior her suicide in 1963 under a pseudonym, Victoria Lucas. It was published in the U.S. under her real name in 1971. Her only novel, it is semi-autobiographical, portraying the author’s struggles with mental illness.

She committed suicide in the same house W. B. Yeats had once lived

From 1962 to 1963, Plath and her two children lived in the same flat that the Irish poet W. B. Yeats had once occupied; she considered this a good omen for her own writing. As is well known, she committed suicide by gassing herself in her kitchen while her children slept soundly in a room nearby.

Her suicide note consisted of four words

It may be surprising given how extensively and evocatively Plath wrote of death and suicide in her poetry, that she left a note of only four words before taking her own life. Her suicide note said simply “Please call Dr. Horder” — along with this doctor’s phone number. The debate has stirred ever since — was her suicide intentional, or a cry for help? Could this even be considered a suicide note at all?

See also: Sylvia Plath’s Suicide Note: Death Knell, or Cry for Help?

Most of her poetry was published posthumously

The Colossus was published in 1960, while she was still alive The poetry in this collection was intense, personal, and delicately crafted.

Though she had been separated from him at the time of her death, Ted Hughes inherited Plath’s literary estate. Much of Plath’s work was unpublished while she was alive, and Hughes decided to publish some of the collections she left behind.

In 1965 Hughes released Ariel, a collection of poems Plath wrote expressing her battle with the darkness of depression, and of their relationship. Throughout the 1970s Hughes continued to release Plath’s poems, but was met with criticism over his selections and decisions.

The suicide of Hughes’ mistress mirrored Plath’s

Ted Hughes left Sylvia Plath for Assia Wevill in 1962. In time, their relationship became fraught and troubled. In a tragic twist of fate, the stresses of scrutiny over her continued relationship with Hughes, the disapproval of his family, and his continued infidelity took their toll on Assia. She dragged a bed into the kitchen of her Clapham flat, dissolved sleeping tablets in a glass of water and gave the drink to her daughter (generally believed to be Hughes’ child) before finishing the rest herself. Mirroring Plath’s suicide method, she then turned on the gas stove and got into bed with her daughter; both died.

You might also enjoy: The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

The post Fascinating Facts About Sylvia Plath appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 28, 2018

The Theme of Survival in Kindred by Octavia E. Butler

For Octavia E. Butler (1947 – 2006), writing science fiction wasn’t merely a vehicle for escaping into fantasy, but a means to explore universal issues. This is certainly true of Kindred, the 1979 novel that is arguably her most iconic.

In the white male-dominated genre of science fiction, she broke ground not only as a woman, but as an African-American.Her deep and abiding interest in and observation of human nature — even within fantastical realms — is what makes her work so compelling, and complex. And yet her storytelling is flowing and natural. Her novels are tightly plotted page-turners; many of her protagonists are strong and believable black women.

After struggling to gain a foothold in the world of publishing, Butler found a home for some short stories and broke through with her first novel, Patternmaster (1976). It was the first in what would become a four-volume series.

It was Kindred (1979) that really launched Butler’s career. Whereas most of her work, before and after, fits squarely into the sci-fi realm, Kindred falls more into the category of speculative fiction. It tells of a contemporary African-American woman who travels back in time to save an ancestor who happens to be a white slave owner. By saving him in his time, she ensures her own survival in the future.

Slavery from a unique perspective

Kindred looks at the practice of slavery in the American South from the perspective of a black woman in the 1970s. Like many of Butler’s other books, this one engages the reader with themes of race, power, gender, and class through the use of skillful storytelling.

Kindred’s protagonist, Dana Franklin, is an African-American woman writer in her twenties living in 1970s California. She’s repeatedly hurtled back in time to a slave plantation in 1815 Maryland.

Witnessing the first-hand the brutality of slavery, Dana learns the true meaning of survival. Her repeated attempts to escape go beyond her personal desire to return to what she comes to realize is, to say the least, a much easier existence. Because many events in the past have already happened and shaped the course of personal and cultural histories, may be beyond Dana’s ability to alter.

Kindred by Octavia E. Butler on Amazon

Kindred is also available as a graphic novel adaptation

Thus, she needs to navigate a tricky balance. Seeking to do as little harm as possible, she is compelled — repeatedly — to rescue Rufus, a ruthless white slave owner who she comes to learn is her ancestor. Thus, her own future existence depends on ensuring his survival.

Dana is also enormously conflicted about Rufus’s rape and concubinage of Alice, a proud black woman who, as it turns out, is also Dana’s ancestor, one that Dana also needs to ensure her own future. Alice’s attempts to escape have even more dire consequences than Dana’s.

The theme of survival

The theme of escape, while ever-present, is overshadowed by the theme of survival — of the self, family, and community. In the present, Dana has lived a life of freedom, and naturally wants to return to it. Yet through her own attempts she comes to know how difficult escape can be for her black kindred of the past:

“Nothing in my education or knowledge of the future had helped me to escape. Yet in a few years an illiterate runaway named Harriet Tubman would make nineteen trips into this country and lead three hundred fugitives to freedom … Why was I still slave to a man who had repaid me for saving his life by nearly killing me? And why … why was I so frightened now — frightened sick at the thought that sooner or later, I would have to run again?”

More about Kindred by Octavia E. Butler

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Time Travel and Slavery

The Joy (and Fear) of Making Kindred into a Graphic Novel

The post The Theme of Survival in Kindred by Octavia E. Butler appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.