Nava Atlas's Blog, page 78

October 23, 2018

Marilla of Green Gables by Sarah McCoy

Marilla of Green Gables is a 2018 novel by Sarah McCoy, an imaginative historical journey that imagines the life of Marilla Cuthbert long before she and her brother Matthew adopt Anne Shirley, better known to readers asAnne of Green Gables.

The release of novels like this one, that draw on beloved characters created by women authors, or that reimagine the life of the authors themselves, prove that our classic Literary Ladies live on in many forms, are still relevant, and resonate with contemporary readers.

From the publisher, William Morrow: For anyone who loves the original Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery and longs for more stories from Prince Edward Island, Marilla of Green Gables, a new novel by New York Times Bestselling author Sarah McCoy (William Morrow, October 23, 2018) will be an incredibly rewarding rewarding return to the beloved stories.

Anyone who has devoured the original series knows Marilla as the stern yet loving spinster (as unmarried women were then termed), who, along with her bachelor brother Matthew who adopt the plucky and imaginative orphan Anne, even though they had requested a boy to help around the farm. This new novel is a beautifully wrought imagining of how Marilla got to be who she was, with a deliciously feminist spin.

Marilla of Green Gables is a marvelously entertaining and moving historical novel, set in rural Prince Edward Island in the nineteenth century. It follows the young life of Marilla Cuthbert, and the choices that will open her life to the possibility of heartbreak — and unimaginable greatness.

Plucky and ambitious, in the new novel Marilla Cuthbert is thirteen years old when her world is turned upside down. Her beloved mother dies in childbirth, and Marilla suddenly must bear the responsibilities of a farm wife: cooking, sewing, keeping house, and overseeing the day-to-day life of Green Gables with her brother, and father.

Her one connection to the wider world is Aunt Elizabeth “Izzy” Johnson, her mother’s sister, who managed to escape from Avonlea to the bustling city of St. Catharines. An opinionated spinster, Aunt Izzy’s talent as a seamstress has allowed her to build a thriving business and make her own way in the world.

Emboldened by her aunt, Marilla dares to venture beyond the safety of Green Gables and discovers new friends and new opportunities. She raises funds for an orphanage run by the Sisters of Charity in nearby Nova Scotia. She embarks on a romance with the charming son of a neighbor, who offers her a possibility of future happiness — but Marilla is in no rush to trade one farm life for another.

She soon finds herself caught up in the dangerous work of politics, and abolition — jeopardizing all she cherishes, including her bond with her new beau.

Marilla must face a reckoning between her dreams of making a difference in the wider world and the small-town reality of life at Green Gables.

About the author: Sarah McCoy is a New York Times, USA Today, and international bestselling author. McCoy’s work has been featured in Real Simple, The Millions, Your Health Monthly, Huffington Post and other publications. She has taught English writing at Old Dominion University and at the University of Texas at El Paso. She lives with her husband, an orthopedic sports surgeon, and their dog, Gilbert, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Visit her at SarahMcCoy.com.

You might also enjoy: Marilla of Green Gables: A Future Feminist

Marilla of Green Gables by Sarah McCoy is available on Amazon.com

and wherever books are sold

PRAISE for MARILLA OF GREEN GABLES

“Prepare to meet Marilla, a captivating heroine who will transport you back to the treasured world of Anne of Green Gables. Rich in historical detail, this charming novel vividly explores love, loss, friendship, and the coming-to-self of a girl on the cusp of womanhood.”

— Sue Monk Kidd, author of The Secret Life of Bees

“L.M. Montgomery’s Marilla Cuthbert flares to life in Sarah McCoy’s enchanting novel of Avonlea. Her story of wrenching family sacrifice and the enduring pleasures of home, is as much a love letter to the world of Green Gables as it is a breath of fresh air. Hats off to McCoy for enlivening this classic with such heart and grace.”

— Paula McLain, author of The Paris Wife and Love and Ruin

“Another girl once came of age at Green Gables. Spunky, smart, buffeted by tides of duty and ambition, loss and love, young Marilla finds her voice in Sarah McCoy’s beautiful rendering of a beloved place, a complex woman, and a long-ago time. Deftly and tenderly told, Marilla of Green Gables is a must read for anyone who adored Avonlea and Anne and ever wondered, what came before?”

—Lisa Wingate,New York Times bestselling author of Before We Were Yours

“Sarah McCoy has given readers a precious gift: the opportunity to step back into the world of Avonlea, and the chance to get to know Marilla Cuthbert as a leading lady in her own right. In McCoy’s skillful and sensitive hands, Marilla emerges as a heroine of depth, complexity, and heart. I savored my time with this cast of old friends, enjoying the dilemma of whether to speed through these compelling pages or to pause and relish everything about the lovely world imagined within them.”

— Allison Pataki, New York Timesbestselling author

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Marilla of Green Gables by Sarah McCoy appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Marilla of Green Gables: A Future Feminist

Sarah McCoy, author of Marilla of Green Gables (2018) explores the formidable yet loving Marilla Cuthbert (who raises the irrepressible orphan Anne Shirley, better known as Anne of Green Gables) in this meditation on family, community, and character:

It’s clear from the first chapter of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s acclaimed Anne of Green Gables who is in charge: Marilla Cuthbert.

My mother first read this novel to me, and I didn’t bat an eyelash at the clear delineation of matriarchal power. I grew up in a military household. My father was an officer frequently away on TDY (Temporary Duty), deployments, and long hours at his army post. So from the beginning, my mother ruled the roost, and we were not the anomaly.

For most I knew, a no-nonsense queen commander was the standard. It wasn’t until I was much older that I first questioned why the rest of the country hadn’t caught on — no woman president, four-star general or chief justice, not to mention a female priest, pastor, or pope.

But as far as Montgomery’s fictional Avonlea was concerned, women were boss. Anne of Green Gables opens with Marilla sending her brother Matthew to the train depot to collect an orphan, and it is only by Marilla’s authority that the child, Anne Shirley, is allowed to stay on at Green Gables.

I’ve read Montgomery’s Anne novels forward and backward. While most scholars are quick to identify Anne as the early feminist, with closer examination, it’s unquestionably Marilla that Montgomery empowers, far before our modern feminism was coined. Given Montgomery’s matriarchal family history, this does not surprise.

Learn more about Marilla of Green Gables by Sarah McCoy

Marilla of Green Gables is available on Amazon

and wherever books are sold

Montgomery’s mother died when she was an infant. Her father moved west to what is now the Saskatchewan Province, remarried, and had a new family. So for all intents and purposes, Montgomery was an orphan who found refuge under the roofs of her maternal grandmother and aunts in Cavendish, Prince Edward Island. For her, it was the women that created and controlled the worlds she knew. The death of her mother, Clara, was the catalytic start. The void Clara left behind was too large for her father to fill. It took a village of women to raise her, as mirrored in her famous Avonlea.

Growing up, I felt like I knew that village. My mother is one of three girls and a boy. My titis (aunties), tio (uncle) and abuelitos (grandparents) were consistent, commanding forces of good in my life. We were blessed to be stationed in locations that allowed us to be together and when we weren’t, my extended family would often gather for long visits—weeks, holidays, whole summers. Family vacations to our Puerto Rican village of Aibonito were a staple.

I joke that we are related to nearly everyone in town, and that’s no hyperbole. Everyone is a great titi, great tio, or distant cousin. So Montgomery’s Avonlea structure was familiar to me. My Aibonito was the only place I felt wholly grounded and tied to a lineage. I counted on it for stability during a military childhood continually in flux and missing parts (my father).

In particular, I was extremely close with my titis and abuelita. There was an entire woman’s world, distinct from the rest of my loving family and magical—or seemingly so to my girlhood self. The women daily gathered in the kitchen to cook and tell secrets. My abuelita taught me to crack a coconut, fry chicken, play Spades, and crochet anything I could dream up, all round the old wooden chopping table. There too, my titis taught me to laugh generously, love fiercely, wear bright red lipstick (because it’s fun), and to sing my own song, even if I didn’t know the words. All of these lessons and more were the structure on which my adult character was built.

I can’t imagine how different I would be if any of those women had been absent—never mind the most principal, my mother, as with Montgomery’s. But I can say with certainty that like Montgomery’s aunts and grandparents, all of mine would’ve rallied around to raise me. There would’ve been no question as to where or how I fit in the genealogical history. I had a tribe of powerful women to ensure I never lacked role models.

See also: Anne of Green Gables, a 1908 review

Similar again to Montgomery, many Latin American families adhere to a patriarchal structure and mine was no different. Still going strong in his late eighties, my abuelo (grandpa) is one of the most noble, loving people on earth. I adore him. Speaking from my singular experience, I’ve noticed that most Latino men are adored by the women in their families. That adoration is freely given and freely accepted, thereby making it a unique kind of power. The paralleling qualities to Victorian mores are not lost on me. Perhaps that’s why I always read between the lines of Montgomery’s fictional landscape.

At Green Gables, she was safe to challenge the accepted sentiment that men were to be revered as ‘head of the household’; when in fact, it was women who controlled a majority of the ins and outs of daily living. For propriety’s sake and as a reverend’s wife, it would’ve been nearly impossible for Montgomery to publicly voice early feminist opinion, so she cleverly wove it into her books. This seemed readily apparent to me, even as a child. After all, I too lived in a world where we honored the traditions of our household: men were venerated— in paid respects if not entirely in authority.

My abuelita did not shirk at my young age when she candidly explained that she had three baby girls in succession (my mother being the third), but would not stop until she had a son for my abuelo. The price for that treasured boy was my grandmother’s ability to conceive again. So cumbersome was my uncle’s birth that she had to have an emergency hysterectomy following his delivery. The moral of the story? He was worth it. I often wondered if she would’ve said the same had the fourth child been female.

In the alternative universe of Green Gables, a boy orphan was also desired, but Anne Shirley showed up at the door. I read this as Montgomery’s way of indirectly discussing the significance of women—and girls who would one day become women. Art, education, politics, religion, nature, fashion, food, family, and farm life: all of these are celebrated in her novels as being distinctly under the feminine thumb.

The sister-less Montgomery and Anne Shirley (myself, too) joined forces with Marilla Cuthbert, Rachel Lynde, Diana Barry, Minnie May, Ruby Gillis, and many more female characters in a collective literary sisterhood. It reminded me of the work of modern feminist author, Meg Wolitzer: “Sisterhood,” Wolitzer wrote in her novel The Female Persuasion, “is about being together with other women in a cause that allows all women to make the individual choices they want.”

Learn more about the author of the original Anne of Green Gables series,

L.M. (Lucy Maud) Montgomery

This is the very definition of the Montgomery’s Avonlea society—an echo of the present in the past. The village women of Avonlea united to empower each other in making conscious, individual decisions. From Anne’s famous smashing of the slate over Gilbert Blythe’s head to Marilla’s brewing of red currant wine despite the reverend’s disapproval, and Diana’s excessive imbibing of it; the choices create the stories that make up the chapters of the novel. True to life, though fictional, they are part of the greater feminist narrative.

In her published diaries, Montgomery described how her grandmother, aunts, and female cousins would assemble to prepare meals, sew, have tea, and decide the plans of the day, the month, and even the year. Then they’d return to their respective farms (miles apart) and implemented those collective plans as they deemed best for their nuclear families. The individual women governed all within the communal house, physically and emblematically, even while the prim culture of the period asserted that their husbands were sovereign. Here, too, Montgomery’s attitude proves far ahead of her time.

She does not recourse to man bashing in her writings. Quite the opposite. As with my own household, the women adored the men. Anne Shirley loved Gilbert Blythe and Gilbert Blythe loved the opinionated Anne Shirley. Marilla Cuthbert cherished her shy, older brother Matthew and he, his stubborn, younger sister. And I assert in my novel Marilla of Green Gables that Marilla deeply loved John Blythe.

In fact, all the characters that Montgomery created are searching earnestly for a heart’s companion—be it male or female, in ardor or bosom friendship. They long for their kindred spirits and will stand to fight if anyone they love is treated unjustly. Through her stories, we clearly see that Montgomery is a champion of strong villages comprised of people living equality and honorably. I witnessed the quest for this in my own childhood and as a modern woman, I continue to seek it out.

This past June, former First Lady Michelle Obama, author of Becoming, spoke at the American Library Association’s Annual Conference in New Orleans. She emphasized the significance of strong female friendships and fostering networks of nurturing women. She entreated the crowd of readers to “Build your village wherever you are!”

A village like Avonlea. Yes, we must. The appeal is as salient now as it was 110 years ago when the women of Green Gables were first introduced. Art may imitate life, but I also believe that life can imitate art. If we advocate for the principles we admire in our characters, they can act as a catalyst for change in our realities. I, for one, am counting on it. And I believe Lucy Maud Montgomery was too in the character of Marilla Cuthbert.

About the author: Sarah McCoy is a New York Times, USA Today, and international bestselling author. McCoy’s work has been featured in Real Simple, The Millions, Your Health Monthly, Huffington Post and other publications. She has taught English writing at Old Dominion University and at the University of Texas at El Paso. She lives with her husband, an orthopedic sports surgeon, and their dog, Gilbert, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Visit her at SarahMcCoy.com.

You might also enjoy

Beyond Beauty: The Natural World in Anne of Green Gables

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Marilla of Green Gables: A Future Feminist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 22, 2018

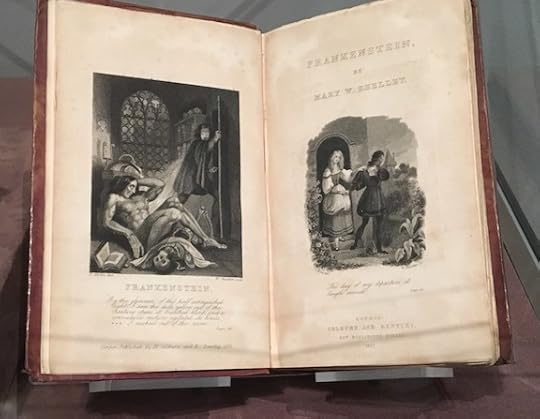

The Morgan Library and Museum Presents: It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200

Fans of the hugely influential 1818 novel Frankenstein and admirers of its author, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley will be thrilled to know that The Morgan Library and Museum is celebrating the 200th anniversary of its publication. If you live in or will be visiting New York City this fall, plan to see It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200, which will be on view through January 9, 2019. A number of events and programs will be held during this time as well, to extend the depth and breadth of this visual exploration. For more on the curation and development of this exhibit, see our related post, It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200.

Learn more about the exhibit here, and note some of the programs and events, including films and gallery talks. The show is introduced as follows:

“Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus — in which a chemistry student makes a living being out of corpses — has compelled our attention since it was first published in 1818. This exhibit explores its adaptability to stage and screen, its sources in Gothic art and Enlightenment Science, and the haunted life of its creator.”

How Frankenstein came to be

Frankenstein has long been acknowledged as one of the most important forerunners of modern science fiction. The genesis of the novel is well known to Mary Shelley nerds: In 1814, the teenaged Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin and the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (a disciple of her father’s) fell in love.

Later that year, the pair eloped to Europe, starting a chain of events that would alter both of their lives. Mary became part of Shelley’s literary circle. In 1816, during a visit to Lord Byron in Switzerland, the group of writers challenged themselves to a task of writing a “ghost story,” as this genre of the supernatural seemed to be in vogue.

An idea didn’t come easily to Mary, but when it did, it wholly possessed her: “I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.” She was just eighteen at the time, and when it was published, she was barely twenty-one. It bears noting that in the story, Victor Frankenstein is the creator of the monster, who is referred to primarily as “the creature.”

On view is the 1831 edition of Frankenstein, in which Mary Shelley finally came out of anonymity. It’s in this edition that she related the entire story of how she came to write Frankenstein.

The exhibit: It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200

The exhibit is thoughtfully arranged in two spaces: One explores the influences that may have impacted and made it possible for Mary, a relatively sheltered young woman from England, to have given birth to such a tale. The path to its publication and immediate aftermath are also traced. The second space takes a look at how the novel took root in the public imagination with staged plays and operas in the 19th century and film in the twentieth.

Some non-flash photography of some portions of the exhibit is allowed, and I’ve shared a few selected images following. But there is so much more to see! For anyone who has never visited The Morgan, you’re in for a treat. Though it’s a well-visited place, it’s also an oasis of calm in near midtown Manhattan, and a respite from the crowdedness of other museums. Make sure to allow for extra time to enjoy the other exhibits that are running concurrently to It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200.

It was a thrill to come upon this iconic portrait of Mary Shelley from 1831. She was at the height of her fame, and already a widow — Shelley had drowned in 1822. And of the several children she had borne, only one son survived.

Mary grew up in an era of scientific and technological discovery. Despite the fact that her early life is described as sheltered, she was part of an enlightened and educated family. It’s quite possible that she learned of some of the experiments and breakthroughs of her time.

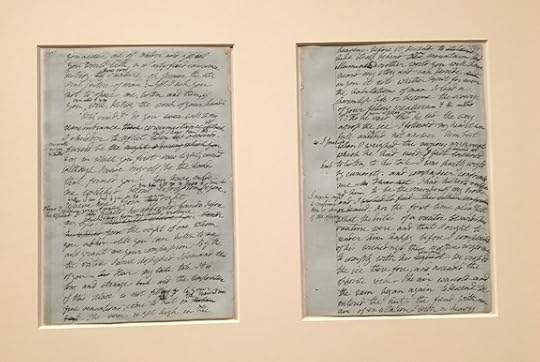

Most of Mary Shelley’s original manuscript from 1816 – 1817 has survived. A few sample pages to view as part of the exhibit; it’s incredibly intimate to see the author’s own hand, and even more fascinating with the addition of Percy Shelley’s editorial suggestions.

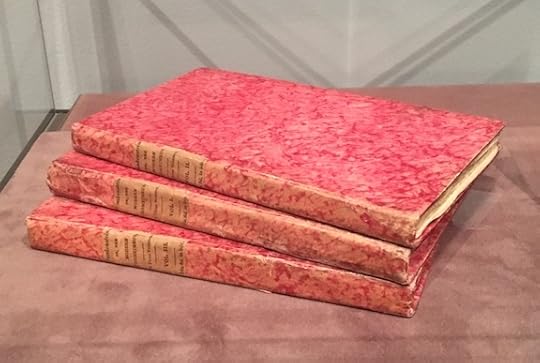

Frankenstein was published in three volumes, as was the style in that era. Something I learned, according to The Morgan: “Sir Timothy [Percy Shelley’s father] loathed his son and daughter-in-law and forbade her to publish under the Shelley name. Nonetheless. she wrote productively for some years after as “the author of Frankenstein.” The initial print run was 500 copies; probably quite respectable at the time, but a fraction of what the book would eventually sell.

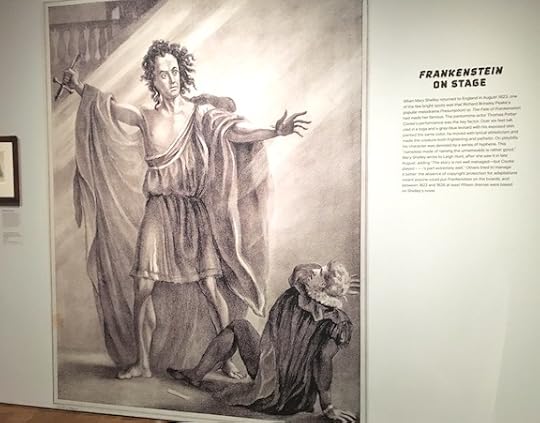

Frankenstein was first staged in London in 1823 and made its author famous. According to The Morgan: “The monster was portrayed by an expressive pantomime actor. Audiences loved it. More than a dozen other theatrical productions appeared, followed by the film version, less than a century after the novel.”

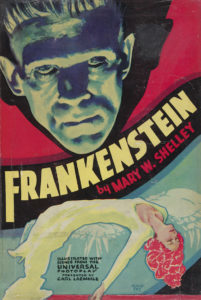

Frankenstein, or, the Modern Prometheus, New York: Grosset and Dunlap, [1931].

Courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum and Universal Studios Licensing LLC, © 1931

Universal Pictures Company, Inc. Photograph by Janny Chiu

Because the 1931 film starring Boris Karloff became so iconic, it’s less known that the Edison Studios produced the first movie version of Frankenstein in 1910. None of the films have truly captured the simple story and emotional depth at the heart of Mary’s book, though. And so the monster, a Halloween cliché, has taken on a life of its own apart from the original book.

Quoting The Morgan: “James Whale’s 1931 film made Boris Karloff the face of Frankenstein for generations of viewers, and versions in other media — comic books, illustrations, prints, and posters — testify that Mary Shelley’s ‘hideous progeny’ is very much alive.”

There’s an abundance of film clips, posters, and other memorabilia to see in this section of the exhibit, in which photography wasn’t allowed. You can even see the fright wig worn by Elsa Lancaster in Bride of Frankenstein, the highly successful sequel to the original film.

The Morgan’s gift shop has plenty of Mary Shelley and Frankenstein-related literature to browse through!

The post The Morgan Library and Museum Presents: It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200 appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 19, 2018

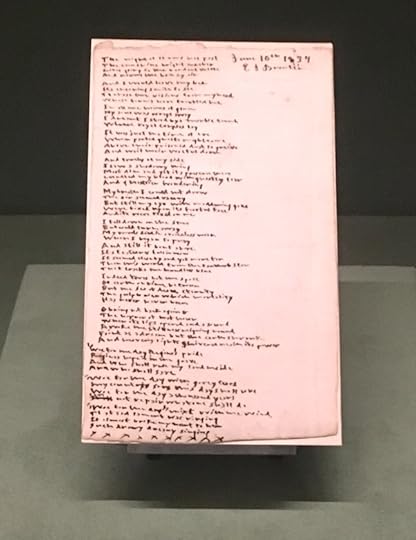

The Night of Storms Has Passed: A Ghostly Poem by Emily Brontë

On a recent visit to The Morgan Library in New York City, I spotted a tiny autograph manuscript of the poem, “The Night of Storms has Passed,” by Emily Brontë, dated June 10, 1837. It was written in tiny, barely legible script on a card perhaps 3 by 4 inches. Written when she was about to turn nineteen years old (she was born July 30, 1818), it was unpublished in her lifetime, but has since been included in collected poems by Emily, perhaps the most inscrutable of the Brontë sisters. The text accompanying the poem read as follows:

A Graveyard Wail by the Teenage Emily Brontë

“A month before she turned nineteen, Emily Brontë wrote this poem about a ghost that opens its lips to emit a lament that mixes eerily with the sound of the wind. She copied an earlier draft, fitting fifty-eight lines onto a scrap a little smaller than an index card. In 1846, when she and her sisters self-published a book of poetry (choosing male pseudonyms to mask their identity), Brontë chose not to include this composition, it remained unpublished in her lifetime.”

The poem has been occasionally included in posthumous collections of Brontë poetry, but is still a rather buried treasure from the pen of Emily Brontë.

You might also like: The Brontë Sisters’ Path to Publication

The Night of Storms Has Passed by Emily Brontë

The night of storms has past

The sunshine bright and clear

Gives glory to the verdant waste

And warms the breezy air

And I would leave my bed

Its cheering smile to see

To chase the visions from my head

Whose forms have troubled me

In all the hours of gloom

My soul was wrapt away

I dreamt I stood by a marble tomb

Where royal corpses lay

It was just the time of eve

When parted ghosts might come

Above their prisoned dust to grieve

And wail their woeful doom

And truly at my side

I saw a shadowy thing

Most dim and yet its presence there

Curdled my blood with ghastly fear

And ghastlier wondering

My breath I could not draw

The air seemed ranny*

But still my eyes with maddening gaze

Were fixed upon its fearful face

And its were fixed on me …

I fell down on the stone

But could not turn away

My words died in a voiceless moan

When I began to pray

And still it bent above

Its features full in view

It seemed close by and yet more far

Then this world from the farthest star

That tracks the boundless blue

Indeed ’twas not the space

Of earth or time between

But the sea of death’s eternity

The gulf o’er which mortality

Has never never been

O bring not back again

The horror of that hour

When its lips opened

And a sound

Awoke the stillness reigning round

Faint as a dream but the Earth shrank

And heavens lights shivered

‘Neath its power

* In some transcriptions of this poem, the word is “uncanny,” though it’s difficult to know which, if either, word was intended by Emily Brontë.

RELATED POSTS

Emily Brontë’s Poetry: A 19th-Century Analysis

No Coward Soul is Mine: 5 Poems by Emily Brontë

The Complete Poems of Emily Brontë on Amazon

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Night of Storms Has Passed: A Ghostly Poem by Emily Brontë appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 18, 2018

Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read

The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s was a fertile decade for African-American creatives of all kinds — writers, musicians, playwrights, and artists. Though like many movements it was male-dominated, many women rose to prominence. We explore some of those who made a lasting impact in Renaissance Women: 12 Female Writers of the Harlem Renaissance, some of whom will also appear in the following list. Here we present women poets of the Harlem Renaissance that have been somewhat or largely forgotten —but whose words and lives should continue to be celebrated.

In her preface to Black Sister: Poetry by Black American Women, 1746 – 1980, Erlene Stetson wrote:

“Black women poets have made a unique contribution to the American literary tradition. This contribution is shaped by their experience both as blacks and as women, an experience whose pressure they have resisted and at the same time as they have recognized its strategic survival value in life and exploited its symbolic power in their art.”

In her introduction to Shadowed Dreams: Women’s Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance, editor Maureen Honey elaborated

“Poetry was the preferred form of most Afro-American women writers during the 1920s. Well known in intellectual circles of their day and widely published, women poets achieved the respect of their peers and popularity with a middle-class audience.”

What happened to some of the women poets of the Harlem Renaissance era was what happened to many of the talents of that time. The Great Depression of the 1930s ended or curtailed the artistic aspirations of many African-Americans. Some were able to later pick up where they left off; others never could recapture the magic of the 1920s. Still, a number of the women poets of the Harlem Renaissance excelled in other fields, especially as educators, social activists, and editors.

Gwendolyn B. Bennett (1902 – 1981) was a multitalented poet, short story writer, visual artist, and journalist. Pride in African heritage and the influence of African dance and music were threads that ran through her work. In the mid-1920s, Her poetry and artwork were published in the The Crisis, NAACP’s journal, Opportunity magazine, and Alaine Locke’s New Negro. Some of her best-known poems included “Moon Tonight,” “Heritage,” “To Usward,” and “Fantasy.” Her published short stories included “Wedding Day” and “Tokens.”

During the Depression, she worked as an administrator on the New York City Works Progress Administration Federal Arts Project (1935-1941), and dedicated herself to advancing the careers of young black artists. More about Gwendolyn B. Bennett at Biography.com.

Carrie Williams Clifford (1882 – 1958) was a fascinating figure from the civil rights movement of the early 1900s, as well as having been an accomplished poet. In her 1911 collection, Race Rhymes, she modestly stated:

“The author makes no claim to unusual poetic excellence or literary brilliance. She is seeking to call attention to a condition, which she, at least, considers serious. Knowing that this may often be done more impressively through rhyme that in an elegant prose, she has taken this method to accomplish this end … The theme of the group here presented — the uplift of humanity — is the loftiest that can animate the heart and pen of man … she sends these lines forth with the prayer that they may change some heart, or right some wrong.”

Her second collection, The Widening Light (1922), contained one of her best known and most poignant poems, “The Black Draftee from Dixie.” More about Carrie Williams Clifford at Poem Hunter.

Clarissa M. Scott Delaney (1901 – 1927) had the distinction of being born at Tuskegee Institute, where her father worked as a secretary to the African-American leader and educator Booker T. Washington. Before her untimely death at age twenty-six, she published poetry and articles in Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life. Professionally, she was a teacher at Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C. There she worked with Angelina Weld Grimké, another poet of the period; the two were good friends.

Delaney’s biography on Black Renaissance states: “During her brief writing life, she only had four poems published. She had a flair for language, good use of metaphors of nature, and she expressed her intensely felt emotions. She had an eye for unique detail, and she undoubtedly would have written more and her work would have matured had she lived longer.”

Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875 – 1935) was a multifaceted writer, poet, journalist, and teacher. She used her pen to advocate for the rights of women and African-Americans during the height of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, and beyond into the Depression era of the 1930s.

In her searingly honest essays, she wrote of the hardships of growing up mixed-race in Louisiana and explored the complex issues faced by women of color. She was also considered one of the premier poets of the Harlem Renaissance. More about Alice Moore Dunbar Nelson, including links to several of her poems, on The Poetry Foundation.

Jessie Redmon Fauset (April 27, 1882 – April 30, 1961) was an American editor, poet, essayist, and novelist. Her literary output included four novels, the best known of which was Plum Bun. but her tenure as the literary editor of the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, was significant.

With a keen eye for talent, she introduced readers to Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Jean Toomer, Claude McKay, and other notable authors and poets of the era. Considered one of the seven “midwives” of the Harlem Renaissance movement, she herself was an accomplished poet, here are 6 poems by Jessie Redmon Fauset to explore. And more about Jessie Fauset here on Literary Ladies Guide.

Angelina Weld Grimké (1880 – 1958) was an American journalist, essayist, playwright and poet whose work was extensively published in The Crisis, the influential journal of the NAACP, and other Harlem Renaissance anthologies. She was the great-niece of the abolitionist Grimké sisters, one of whom was also named Angelina.

Her play, Rachel (1920) was one of the first staged staged productions of a work by a woman of color. She lived a quiet life and her subtle love poems to women hint at a life not fully expressed. Angelina Weld Grimké considered hugely important to the growth of the Harlem Renaissance movement, yet her personal work and contributions are under-appreciated. More about Angelina Weld Grimké at Black History Now.

Ariel Williams Holloway (1905 – 1973) set out to be a concert pianist, having earned degrees in music from Fisk University and Oberlin College. Despite her formal training, she found that her professional aspiration was closed to African-American women. Instead, she taught music at the high school and college level around the South, and in 1939, became the first supervisor of music in the Mobile, Alabama public school system. She held this post until her death.

Though she was never a New Yorker, Williams had her poems published in Opportunity, and The Crisis, the leading journals of the Harlem Renaissance, between 1926 and 1935. Later, she published a volume of verse, Shape Them into Dreams (Exposition Press, 1955). “Northboun,’” a short poem written in dialect about the Great Migration, originally published in Opportunity in 1926, won an important prize and is considered her best-known work of poetry. More about Ariel Williams Holloway.

Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880 – 1966) was best known as a poet active during the Harlem Renaissance era, though she also was an avid musician, and teacher, and an anti-lynching activist. She was one of the first African-American female playwrights and produced four books of poetry.

Her poem “The Heart of a Woman” (1916) influenced Maya Angelou, whose 1981 memoir of the same name pays direct homage to this work by Johnson. Threads running through her work included family, motherhood, and navigating life in America as a woman of color. More about Georgia Douglas Johnson here on Literary Ladies Guide; and here are 10 Poems by Georgia Douglas Johnson.

Helene Johnson (1906 – 1995) was only 21 when her poem “Bottled” was published in Vanity Fair in 1927. It was considered innovative and unconventional. Like her cousin Dorothy West, she moved to Harlem in the 1920s and befriended other literary figures like Zora Neale Hurston.

Readers began to take notice when Johnson’s poem “Bottled” containing innovative slang and unconventional rhythms was published in Vanity Fair, in the May edition of 1927. A short poem called “Ah My Race” is also one of her best known. Her last published poems appeared in Challenge: A Literary Quarterly, in 1935. Though she stopped publishing, she continued to write a poem a day for the rest of her long life. More about Helene Johnson here on Literary Ladies Guide; and here is a selection of her poems.

May Miller (1899 – 1995) was one of the most widely published female playwrights and poets of the Harlem Renaissance era, having published seven volumes of poetry. She began writing poetry at an early age, and though it was her first love, her accomplishments branched out widely. She was the first African-American student to attend Johns Hopkins University, and would subsequently become one of the pioneers in the field of sociology.

Miller augmented her work as a writer with a distinguished career as a teacher and lecturer in a number of prestigious institutions. Learn more about May Miller.

Effie Lee Newsome (1885–1979) was best known for her poetry for children. Her writings were widely published in the NAACP’s The Crisis, and the Urban League’s Opportunity. She was also the editor of the children’s column “Little Page” in the Crisis.

Her poetry encouraged younger readers to appreciate their worth and beauty — it has been written that her poetry was a forerunner of the 1960’s Black is Beautiful movement. Later in her career, she worked as a children’s librarian in Ohio, continuing to promote books and literature to young readers. More about Effie Lee Newsome on poets.org.

Esther Popel (1896–1958), writer, teacher, and activist, wrote poetry that didn’t shy away from bitterness as her words reflected on injustice, racial prejudice, and violence against black Americans. While a senior in high school, Popel self-published her first book of poetry, Thoughtless Thinks by a Thinkless Thaughter (1915). Like many of her contemporaries of the Harlem Renaissance, she published in The Crisis and Opportunity, winning several awards for her work.

Having been well-educated herself, she lobbied for opportunities for women of color and served on the board of the National Association of College Women for two decades. See more about Esther Popel on My Poetic Side.

Anne Spencer (1882 – 1975) was born on a Virginia plantation. Though she endured a turbulent early life, she remained close to her mother, who saw to it that Anne received a good education. Once married, her mother took over Anne’s household responsibilities so that she could pursue a life of the mind and develop collegial relationships with the prominent intellects of the time. The eminent James Weldon Johnson became her mentor, and he saw to it that her poetry was published.

Anne, who was also a political activist, one of those bright-burning lights that was dimmed by the Depression. She was unable to publish after 1931 and her works were never in a stand-alone collection. But she lived to age ninety-three and never stopped writing. Today, her life and legacy have been preserved at the Anne Spencer Museum.

An excellent resource is Shadowed Dreams: Women’s Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance, edited by Maureen Honey (Rutgers University Press, 1989). In it, you’ll find these and many other lesser-known writers of the era.

OTHER POETIC VOICES TO REDISCOVER

Anita Scott Coleman

Mae Virginia Cowdery

Edythe Mae Gordon

Gertrude Parthenia McBrown

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 17, 2018

Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist

In 1893, a deputy sheriff knocked on Matilda Joslyn Gage’s door in Fayetteville, New York. He served her with a supreme writ, court papers summoning her to appear before a judge for breaking the law.

“All of the crimes which I was not guilty of rushed through my mind,” she wrote later, “but I failed to remember that I was a born criminal—a woman.” Her crime: registering to vote. The verdict: guilty as charged.

Matilda Joslyn Gage was born in 1826 in Cicero, New York, near Syracuse. She lived all her life in the Syracuse area but also spent time with her adult children who lived in Dakota Territory. Her home in Fayetteville, New York, is now a museum.

The following excerpt is from Angelica Shirley Carpenter’s biography Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist, published in September 2018 by the South Dakota Historical Society Press, lightly edited for publication here. Reprinted by permission. Sources may be found in the book.

The National Citizen and Ballot Box

In April 1878 Matilda Joslyn Gage bought an Ohio women’s suffrage newspaper, the Ballot Box. Moving it to Syracuse, she renamed it the National Citizen and Ballot Box. As editor and publisher, Matilda did most of the writing, but Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, as corresponding editors, wrote letters to what soon became the official newspaper of the National Woman Suffrage Association.

The monthly publication, “the cheapest paper in the country, $1 a year,” offered three and a half pages of news and a half page of advertisements. Matilda inherited two thousand subscribers.

The National Citizen published letters and firsthand accounts of women’s experiences. Editorials offered a feminist perspective on marriage customs, rape, labor laws, taxes, the status of women in foreign countries, and the church. Matilda wrote a column, “Women, Past and Present,” and covered conventions extensively, knowing that many of her readers could not afford to attend. She printed selections from the History of Woman Suffrage [a book she was writing with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, with Susan B. Anthony as business manager for the project] as they were completed, asking readers to send in corrections.

Matilda Joslyn Gage in 1881 (photo courtesy of the Gage Foundation)

Suffering often from poor health, Matilda kept working on the History and wrote for other publications, too, including a newspaper in San Francisco. When six young girls were arrested for streetwalking in Fayetteville, she protested to the local newspaper. Two of the girls were just fifteen; the men who had hired them were “village respectables” who were not named in court or charged.

As usual, Matilda’s opinion was more liberal than that of her colleagues. She viewed prostitution as an economic rather than a moral issue, the product of unjust labor laws and the lack of education for women.

“Women of every class, condition, rank and name, will find this paper their friend, it matters not how wretched, degraded, fallen they may be,” she said on the front page of each issue of the National Citizen and Ballot Box.

In her paper she described a mother of ten who was jailed for stealing food for her children, and a man who got a shorter sentence for beating his wife than he would have received for beating a horse (six months for a wife, two years for a horse). She reported on women living collectively and starting cooperative businesses, and she advocated for boarding houses for working women. Leaders of the women’s movement who fought to open universities and professions to women took less interest than Matilda in the rights of female factory workers, but The National Citizen fought for these women, too.

Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist on Amazon

The paper was not completely serious. One article told of a Russian sect which required husbands to confess sins to wives once a week.

“Would not that require the whole week?” Matilda asked.

Matilda, like other feminists, was often called a man-hater. The Vineland Times, a New Jersey paper, criticized the National Citizen: “It is too aggressive, and too bitter against men.”

“As to ‘aggressiveness,’” Matilda responded, “bless your soul, that is the way to carry on a warfare.”

The paper gave Matilda a new forum in which to promote the Native American society she admired. In May 1878 the United States was trying to force citizenship on Native people, who were fighting it.

“Our Indians are in reality foreign powers,” Matilda wrote, “though living among us. With them our country not only has treaty obligations, but pays them, or professes to, annual sums in consideration of such treaties. . . . Compelling them to become citizens would be like the forcible annexation of Cuba, Mexico, or Canada to our government, and as unjust.”

In July Matilda traveled to Rochester, New York, for the thirtieth anniversary celebration of the Seneca Falls women’s rights convention. The convention call said that the meeting would be “largely devoted to reminiscences.” Rochester, known as “The Flower City,” provided beautiful floral decorations for the meeting in the Unitarian church on Fitzhugh Street. Some blossoms drooped in record high temperatures as old friends greeted each other happily, with damp hugs. Fans fluttered and cooling liquids were offered as people gathered under “twining wreaths, running through the low, wire lattice, about the platform, and in hanging clusters of vines from the chandeliers.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton spoke of progress made in the women’s movement and goals still to be achieved. Letters and telegrams from across the country and from Europe, were read aloud. Lucretia Mott expressed joy at the number of young women sitting on the platform for the first time.

“Though in her eighty-sixth year,” the History of Woman Suffrage later described Mott, “her enthusiasm for the cause for which she had so long labored seemed still unabated, and her eye sparkled with humor as of yore while giving some amusing reminiscences of encounters with opponents in the early days.”

Mott yielded the podium to Matilda, watching eagerly as her former protégée proposed a series of resolutions. Three of these, written by Matilda herself, became particularly controversial:

Resolved, That as the duty of every individual is self-development, the lessons self-sacrifice and obedience taught women by the Christian church have been fatal, not only to her own highest interests, but through her have also dwarfed and degraded the race.

Resolved, That the fundamental principle of the Protestant reformation, the right of individual conscience and judgment in the interpretation of scripture, heretofore conceded to and exercised by man alone, should now be claimed by woman, and in her most vital interests she should no longer trust authority, but be guided by her own reason.

Resolved, That it is through the perversion of the religious element in woman, cultivating the emotions at the expense of her reason, playing upon her hopes and fears of the future, holding this life with all its high duties forever in abeyance to that which is to come, that she, and the children she has trained, have been so completely subjugated by priestcraft and superstition.

Then Matilda, along with everyone in the hot, crowded church, listened sadly as Lucretia Mott gave what all knew would be her last speech. Her family had tried to stop her from attending the convention, worried that the trip from Philadelphia, in extreme heat, would prove too much for her. But she had insisted on coming, traveling with a friend, and staying in Rochester with her husband’s nephew, a doctor.

The doctor, fearing that she would be exhausted, called for her to stop before she had finished her closing remarks. Climbing down from the platform, Mott continued speaking as she walked down the aisle, swinging her bonnet by one string, as she often did, and shaking hands on either side. The audience rose simultaneously, out of respect for her.

“Good-by, dear Lucretia!” Frederick Douglass called, speaking for all of them.

After the convention, Matilda’s resolutions created a second kind of heat wave in newspapers and pulpits around the country.

“There was never a clearer illustration,” said The New York World, “of the evil tendencies of the Woman’s Rights movement than in the resolutions adopted at the Rochester convention.”

“Too hazardous,” proclaimed the Rev. A.H. Strong, president of the Baptist Theological Seminary in Rochester. “Bad women would vote.”

“Well, what of it?” Matilda responded, in a National Citizen and Ballot Box editorial, “Have they not equal right with bad men to self-government?”

After three years, paid advertisements to the newspaper decreased. For a time, Matilda subsidized it with her own money, but she could not afford to keep it going. Her last editorial, in October 1881, was called “The End, Not Yet”: “To those who fancy we are near the end of the battle, or that the reformer’s path is strewn with roses, we say them nay. The thick of the fight has just begun; the hottest part of the warfare is yet to come, and those who enter it must be willing to give up father, mother, and comforts for its sake. Neither shall we who carry on the fight, reap the great reward. We are battling for the good of those who shall come after us; they, not ourselves, shall enter into the harvest.”

Angelica Shirley Carpenter has master’s degrees from the University of Illinois in education and library science. Curator emerita of the Arne Nixon Center for the Study of Children’s Literature at California State University, Fresno, she lives in Fresno. She has published five previous books about authors: Frances Hodgson Burnett (two books), Robert Louis Stevenson, Lewis Carroll, and L. Frank Baum, who was Matilda’s son-in-law. A past president of the International Wizard of Oz Club, she is active in the Lewis Carroll Society of North America and the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. Find out more about her at angelicacarpenter.com.

The post Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 16, 2018

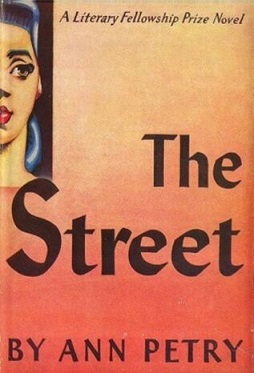

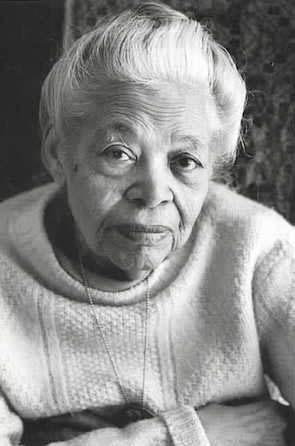

Ann Petry

Ann Petry (October 12, 1908 – April 28, 1997) was the first African-American woman to produce a book (The Street) whose sales topped one million. Ultimately it would sell a million and a half copies. Born Ann Lane, she was raised in Old Saybrook, Connecticut.

Encounters with the pervasive racism that permeated American life in their time were relatively rare — though not entirely absent — in the sheltered life that the Lanes provided for Ann and her siblings. She was a fourth-generation native of Connecticut, and was the daughter of practical, ambitious parents. Her father, Peter Clark Lane, was a pharmacist; her mother, Bertha James Lane, was a podiatrist. For other role models she had an extended family of strong professional women

Though a high school teacher encouraged her to write, Ann went to pharmacy college and received a degree. This was in the early 1930s, when a practical profession was a blessing during the Great Depression. She followed in her father’s footsteps to become a pharmacist in the family drugstore. She was always an avid reader who was particularly taken with Louisa May Alcott’s fictional heroine Jo March as a role model for her writerly aspirations.

A move to Harlem

In 1938, she married George Petry, and the couple moved to Harlem. There she began a writing career in earnest, working as a journalist, columnist, and editor. She took writing courses at Columbia University and drawing and painting courses at Harlem Art Center. She also participated in Harlem’s American Negro Theatre, performing onstage as Tillie Petunia in Abram Hill’s play On Striver’s Row.

Ann was active in social issues as well. She ran an after school program at an elementary school in Harlem, and was an organizer for Negro Women Inc. These experiences opened Ann’s eyes to the challenges facing working class women, whose lives were far more vulnerable than what she had experienced in her genteel upbringing. Witnessing class, race, and economic struggles firsthand was what informed her fiction.

She wrote many short stories for magazines and journals and periodicals, but it was “On Saturday, the Sirens at Noon” — a story that was published in a 1943 issue of The Crisis that proved a major turning point. She received notification after the story appeared to enter the competition for the Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship. She submitted the first few chapters of the book she’d been working on, The Street, and was awarded the fellowship, which came with a handsome cash award.

See more about The Street (1946)

The Street

The Street was published in 1946, and became an overnight sensation. The New York Times called it “a skillfully written and forceful first novel.’’ Its significance was as a novel that explored black women’s experience through the intersection of race, gender, and class.”

Despite its commercial and overall critical success, The Street was not without its detractors. Some African-American critics, including James W. Ivey of The Crisis, objected to Petry’s one-sided portrayal of Harlem as a “seething cesspool of sluts, pimps, juvenile delinquents …” and deemed it “worthless as a picture of Harlem though interesting as a revelation of Mrs. Petry.”

Ann Petry published seven other books, but none was as successful as The Street.

Pointed reflections of black America

Ann Petry’s life was less fraught than that of the characters she wrote about. She was sensitive to the oppression and disadvantages caused by racial bias, and these themes were reflected in her fiction. In an essay, Ann said of her work: “When I write for children, I write about survivors. When I write for adults, I write about the walking wounded.” Ann Petry by Hilary Holladay (1996), encapsulates what she sought to express as a writer of fiction:

“Ann Petry’s fiction deals with prejudices of race, sex, and class, and with the ways in which the American dream of success and plentitude haunts, and finally mocks, those people who fail to achieve it. She writes in rhythmic, deceptively simple prose, frequently underscoring the unsettled, disrupted nature of human relations via setting and environmental detail.

Petry calls her characters “the walking wounded” and her use of naturalism, especially in The Street and Country Place, provides them with realistically portrayed, yet fundamentally unstable, ground on which to make their hobbling way. In 1950, Petry suggested why people want to read fiction that addresses difficult social issues:

Possibly the reading public, and here I include myself, is like the man who kept butting his head against a stone wall and when asked for an explanation said that he went in for this strange practice because it felt so good when he stopped. Perhaps there is a streak of masochism in all of us; or perhaps we feel guilty because of the shortcomings of society and our sense of guilt is partially assuaged when we are accused, in the printed pages of a novel, of having done those things that we ought not to have done — and of having left undone those things we ought to have done.

Because racism and sexism and their consequences remain integral to life in America, Petry’s characterizations of these prejudices in her fiction continue to inspire feelings of masochisms and guilt. Although she did the bulk of her writing midcentury, her novels and stories articulate the same pain and outrage expressed by contemporary chroniclers of sexism and racism.

Petry’s works are thus more timeless — and timely — than one might like them to be. Petry herself has said of The Street, “It just saddens my heart so that if you added crack, it would be the same story today. It’s just so painful and frightening.”

The Street Reissued in 1992

In 1992, The Street was re-released by its original publisher, Houghton Mifflin. Ann Petry fame rose once again, now age 84. She was profiled in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, and other publications. The Street was recognized as an important contribution to African-American literature.

The Hartford Courant, a newspaper relatively close to Ann’s home of Old Saybrook, Connecticut home, quoted Margo Perkins, a teacher of African-American literature at Trinity College on the impact of The Street: “It is one of the first novels to talk about black women’s experience in terms of the intersection of race, class and gender, and it paralleled Richard Wright’s work, which very much focused on black men. It has been reclaimed in the last several years as a very important novel.”

Reviewing the 1992 edition of The Street, the L.A. Times review remarked, “Lutie Johnson is an incandescent spirit trapped in circumstances that constantly conspire to douse her potential. White women view her as a threat and men of every race appraise her as a possible conquest. Whenever she allows herself to be naive enough to forget the rules of the game–that is, that an impoverished black woman alone is considered prey — she is violently reminded of her situation.”

You might also like: 6 Interesting Facts About Ann Petry

Teaching and continuing to write

Sudden fame after The Street’s success proved overwhelming. Petry and her husband left New York City to return to Old Saybrook, purchased a house, and raised their only daughter there. The town where she was grew up remained her home base for the rest of her days, even as she taught and lectured far and wide.

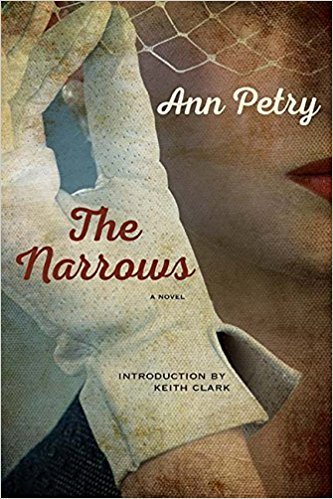

The Street was quickly followed in 1947 with Country Place, a story taking place in the familiar setting of a drugstore. The Narrows (1953) is a novel of an interracial romance.

After this, a few children’s books were produced: The Drugstore Cat (1949), Harriet Tubman: Conductor on the Underground Railroad (1955), and Tituba of Salem Village (1963). She continued to write short stories and even went to Hollywood for a brief sojourn to work on a movie script. Petry published The Narrows in 1953, and finally, a short story collection, Miss Muriel and Other Stories, in 1971.

Later years

Though none of her subsequent works sold in the sheer volume of The Street, nor achieved its notoriety, Ann Petry remained a respected voice, received a number of honorary degrees, and was inducted into the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame. Her work has lately begun to be revisited and studied. Petry died in Old Saybrook in 1997.

More about Ann Petry on this site

Ann Petry Talks of Race Problems

6 Interesting Facts About Ann Petry

Quotes from The Street by Ann Petry

Major Works (fiction)

The Street (1946)

Country Place (1947)

The Narrows (1953)

Miss Muriel and Other Stories (1971)

Other Works (for younger readers)

Tituba of Salem Village

Harriet Tubman: Conductor on the Underground Railroad

The Drugstore Cat

Biographies about Ann Petry

The Radical Fiction of Ann Petry by Keith Clark (2013)

At Home Inside: A Daughter’s Tribute to Ann Petry (2008)

More information

Ann Petry on Wikipedia

Ann Petry: The Hutchins Center for African &

African American Research at Harvard

Ann Petry in the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame

Meet Lutie Johnson on PBS’s American Masters

Articles, News, Etc.

Ann Petry: Brief Life of a Celebrity-Averse Novelist , Harvard Magazine, Jan./Feb. 2014

Letters Illuminate Life of African American Novelist Ann Petry

Research/archives

Ann Petry Papers at Radcliffe College – Schlesinger Library

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Ann Petry appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 15, 2018

10 Classic Indian Women Authors

The most fascinating part of this exploration of classic Indian women authors is that their writings reflected a feminist bent. Given the strong patriarchal culture that still prevails in India and the fact that most of these women started their creative lives in the mid-twentieth century, one can only marvel at the courage and strength of their writings.

Since India has twenty-two recognized languages, this compilation is by no means comprehensive. For the sake of convenience, the authors have been listed in chronological order of their birth years.

Malati Bedekar (1905 – 2001) was among the most prominent of feminist writers of her time in Marathi, who also wrote under the pen name of Vibhavari Shirurkar. Her collection of short stories (Kalyanche Nishwas) and a novel (Hindolyawar) written in the early 1930s dealt with themes too bold for society of those times and created a huge storm over the identity of the unknown author. A few years before her marriage to a writer, Vishram Bedekar, she revealed her true identity. Her books in translation are still listed under her pen name on Amazon.

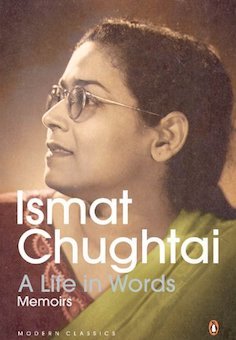

Ismat Chughtai (1915 – 1991) was an Urdu writer who wrote both short stories and novels opting for literary realism. She started writing in the 1930s, and her themes included middle-class morality, female sexuality with a feminist perspective, and class conflict, often involving shades of Marxist thought.

Her short story “Lihaaf” (“The Quilt”) was a pioneer in the theme of touching upon sexuality, till then a tabooed subject in modern Indian literature. The story ventured into the subject of female homosexuality, which attracted a court trial. The author had to make an appearance and defend herself against charges of “obscenity.” Ismat was a recipient of both literary and national awards and her works were turned into well-known films too. Find English translations of Chughtai’s works on Amazon.

M.K. Indira (1917 – 1994) was a distinguished Kannada writer whose education did not go beyond the primary level. In her literary career of twenty-two years, she wrote forty-eight novels, fifteen collections of short stories, one biography, a film appreciation book, and an unfinished autobiography.

Five of her novels were turned into films, of which Phaniyamma, on the life of a child widow, turned into the greatest hit. It won its English translator, Tejaswini Niranjana, many literary awards. Many of Indira’s titles are available on Amazon, but the only one that seems to be in English translation is the aforementioned The Young Widow.

Amrita Pritam (1919 – 2005) was the first eminent Punjabi writer, novelist and poet of twentieth-century India. While her early novels were left-leaning and anti-imperialist, from 1960 her writings became more feminist in nature. During this time, her works were translated into English, Japanese, Mandarin, French and Danish. Many of her novels were turned into films and she won many literary awards including India’s highest, the Jnanpith, in 1982. You’ll find some English translations of Pritam’s work listed on Amazon.

M.K. Binodini Devi (1922 – 2011) was a novelist, short story writer, essayist, lyricist and script writer, who wrote in Meiti, a Tibeto-Burmese language spoken in the state of Manipur. Born into a royal family, she was the first woman graduate from her state.

Binodini was considered a pioneer of the non-doctrinaire thinking of Manipur, deeply rooted in the state’s region with little focus on conventional modernism. Besides film scripts, her works comprised dance ballets on environmental issue. She was also elected to the Legislative Assembly of Manipur. Binodini Devi received many literary and national awards in her time.

Kamala Markandaya (1924 – 2004) wrote in English about the struggles of Indians caught between the conflicting Indian and Western values of their times. Starting as a journalist, her first novel, Nectar in a Sieve, remains her most acclaimed one. In 1948, she opted to move to England and later married a Britisher. She published many more novels from there, and referred to herself as an Indian expatriate. Amazon has a full slate of Markankaya’s works translated into English.

Mahasweta Devi (1926 – 2016) wrote in Bengali and became a voice of the downtrodden, dispossessed and ignored population of India. Her seminal work, Hajar Churashir Maa, became an acclaimed film, as did many of her other works. She was the recipient of innumerable literary and national awards and even the Ramon Magsasay Award for “compassionate crusade through art and activism to claim for tribal peoples, a just and honourable place in India’s national life.” Amazon offers a number of Devi’s works in English translations.

Raghavan Chudamani (1931 – 2010) wrote in Tamil and also short stories in English, in addition to translating other Indian authors into Tamil. On account of a physical disability, she was homeschooled. She was the recipient of a state award from the Tamilnadu government as also literary awards. Amazon has only one novel of hers, Yamini, in translation.

Kamala Das (1934 – 2009) was a leading Malayalam author as also an Indian English poet. She also wrote under her pen name, Madhavi Kutty and is best known for her short stories and her very explicit autobiography, My Story. Her poems have been considered on par with Anne Sexton and she won many literary awards in her lifetime, besides being shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1984.

Indira Goswami (1942 – 2011) who wrote in Assamese under her pen name, Mamoni Raisom Goswami, was known for going beyond the borders of her own state in her writings. She received many literary awards including India’s highest, the Jnanpith and also won the Prince Claude Award from the government of Netherlands. Her novel, Moth Eaten Howdah of a Tusker, was anthologized in the Masterpieces of Indian Literature and also made into a film, Adajya, that garnered several national and international awards. Amazon offers a number of Goswami’s works in English translation.

Melanie P. Kumar is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 10 Classic Indian Women Authors appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 13, 2018

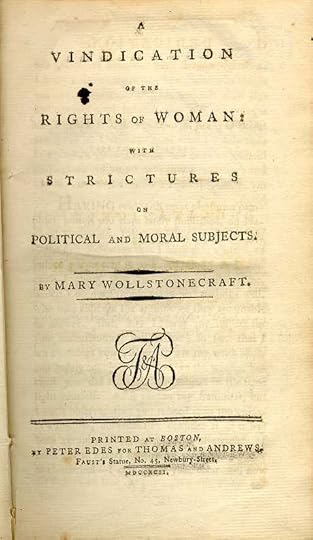

Quotes from A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft

One of the earliest works of feminist philosophical literature, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects was written by Mary Wollstonecraft and published in 1792. Mary Wollstonecraft (not to be confused with her literary daughter, Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein) argues in Vindication for the educational equality of men and women. She argued that men and women are both born with the ability to reason, and therefore power and influential status should be equally available to all.

Wollstonecraft believed that regardless of wealth and social status, males and females should have the same educational opportunities. She sought radical reform of the 18th-century education system, believing that a society where females are offered the same opportunities as males would bring only beneficial change to the future of humanity.

More than two hundred years later, the struggle for gender equality continues, making this a great time for bold feminist thought! Here’s a selection of empowering and radical quotes from A Vindication of the Rights of Woman to stay inspired to keep fighting the good fight!

“Soft phrases, susceptibility of heart, delicacy of sentiment, and refinement of taste are almost synonymous with the epithets of weakness…I wish to show that elegance is inferior to virtue.”

“My own sex, I hope, will excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone.”

“I do not wish them [women] to have power over men; but over themselves.”

“Taught from their infancy that beauty is woman’s scepter, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison.”

“I love man as my fellow; but his scepter, real, or usurped, extends not to me, unless the reason of an individual demands my homage; and even then the submission is to reason, and not to man.”

“I love man as my fellow; but his scepter, real, or usurped, extends not to me, unless the reason of an individual demands my homage; and even then the submission is to reason, and not to man.”

“I earnestly wish to point out in what true dignity and human happiness consists. I wish to persuade women to endeavor to acquire strength, both of mind and body, and to convince them that the soft phrases, susceptibility of heart, delicacy of sentiment, and refinement of taste, are almost synonymous with epithets of weakness, and that those beings are only the objects of pity, and that kind of love which has been termed its sister, will soon become objects of contempt.”

“But women are very differently situated with respect to each other – for they are all rivals (…) Is it then surprising that when the sole ambition of woman centres in beauty, and interest gives vanity additional force, perpetual rivalships should ensue? They are all running the same race, and would rise above the virtue of morals, if they did not view each other with a suspicious and even envious eye.”

“Love from its very nature must be transitory. To seek for a secret that would render it constant would be as wild a search as for the philosopher’s stone or the grand panacea: and the discovery would be equally useless, or rather pernicious to mankind. The most holy band of society is friendship.”

“The man who can be contented to live with a pretty and useful companion who has no mind has lost in voluptuous gratifications a taste for more refined pleasures; he has never felt the calm and refreshing satisfaction. . . .of being loved by someone who could understand him.”

Public domain eBook of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

“For any kind of reading I think better than leaving a blank still a blank, because the mind must receive a degree of enlargement and obtain a little strength by a slight exertion of its thinking powers; besides, even the productions that are only addressed to the imagination, raise the reader a little above the gross gratification of appetites, to which the mind has not given a shade of delicacy.”

“And, perhaps, in the education of both sexes, the most difficult task is so to adjust instruction as not to narrow the understanding, whilst the heart is warmed by the generous juices of spring . . . nor to dry up the feelings by employing the mind in investigations remote from life.”

“All the sacred rights of humanity are violated by insisting on blind obedience.”

“It is justice, not charity, that is wanting in the world!”

“Yet women, whose minds are not enlarged by cultivation, or in whom the natural selfishness of sensibility hasn’t been expanded by reflection, are very unfit to manage a family, because they always stretch their power and use tyranny to maintain a superiority that rests on nothing but the arbitrary distinction of fortune.”

“It is easier to list modes of behaviour that are required or forbidden than to set reason to work; but once the mind has been stored with useful knowledge and strengthened by being used, the regulation of the behaviour may safely be left to its guidance without the aid of formal rules.”

“Taxes on the very necessaries of life, enable an endless tribe of idle princes and princesses to pass with stupid pomp before a gaping crowd, who almost worship the very parade which costs them so dear.”

“Happy would it be for women, if they were only flattered by the men who loved them; I mean, who love the individual, not the sex.”

“And having no fear of the devil before my eyes, I venture to call this a suggestion of reason, instead of resting my weakness on the broad shoulders of the first seducer of my frail sex.”

“It is far better to be often deceived than never to trust; to be disappointed in love, than never to love.”

“Consequently, the most perfect education, in my opinion, is such an exercise of the understanding as is best calculated to strengthen the body and form the heart; or, in other words, to enable the individual to attain such habits of virtue as will render it independent. In fact, it is a farce to call any being virtuous whose virtues do not result from the exercise of its own reason.”

“Women are told from their infancy, and taught by the example of their mothers, that a little knowledge of human weakness, justly termed cunning, softness of temper, outward obedience, and a scrupulous attention to a puerile kind of propriety, will obtain for them the protection of man; and should they be beautiful, every thing else is needless, for, at least, twenty years of their lives.”

“So ludicrous, in fact, do these ceremonies appear to me, that I scarcely am able to govern my muscles, when I see a man start with eager, and serious solicitude to lift a handkerchief, or shut a door, when the LADY could have done it herself, had she only moved a pace or two.”

“It appears necessary to go back to first principles in search of the most simple truths, and to dispute with some prevailing prejudice every inch of ground.”

“Men, indeed, appear to me to act in a very unphilosophical manner when they try to secure the good conduct of women by attempting to keep them always in a state of childhood.”

The post Quotes from A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 10, 2018

10 Thought-Provoking Classic Short Stories by Women Authors

A short story is a fantastic way to get a sense of an author’s voice. In some ways, it can be more challenging to create a compelling narrative in a short form than within the span of a novel. Building suspense and getting the reader to care about the characters are true marks of craftsmanship. Here are ten thought-provoking classic short stories by women authors. You’ll be able to read some of them (those in the public domain) right here on this site; others are part of these authors’ short story collections.

Sometimes there’s a fine line between when a short story shades into a novella, as is the case with The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, but we’ve got that covered as well. Make sure to explore our recommendations for Must-Read Novellas by Classic Women Authors.

“The Giant Wistaria” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1891)

In Jillian McKeown’s analysis of “The Giant Wistaria” (1891), she introduces this chilling short ghost story by classic feminist author Charlotte Perkins Gilman:

It’s shocking once you’ve finished “The Giant Wistaria” to realize that it was published in 1891, when it seems as if it were written not so long ago. The story takes place during two time periods, the 1700s and the 1800s. The former century begins with an English family and we’re dropped into the middle of the most scandalous of family dramas — their daughter has just given birth out of wedlock, and the parents are fleeing to England to escape any disgrace to their family name.

Read the full text of “The Giant Wistaria” here.

“Désirée’s Baby” by Kate Chopin (1893)

“Désirée’s Baby” is an 1893 short story by Kate Chopin. This American author, now a fixture in feminist studies, is best known for the classic novella The Awakening. In this brief short story, she explores the hypocrisy, racism, and sexism in upper-crust Creole Louisiana. “Désirée’s Baby” weaves in themes that would come to define her works, including women’s struggle for equality, suppressed emotion, and the vagaries of identity.

First published in the January 1893 issue of Vogue magazine as “The Father of Désirée’s Baby,” it was included in Bayou Folk, a short story collection by Chopin published the following year. You can read the full text of the story here.

“Paul’s Case: A Study in Temperament” by Willa Cather (1905)

“Paul’s Case: A Study in Temperament” is a short story by Willa Cather, first published in McClure’s Magazine in 1905. An analysis of “Paul’s Case” by Sarah Wyman on this site begins:

You probably know someone who reminds you of Paul, someone who does not seem to fit in with others in society. Paul’s mannerisms are tense and nervous. He appears antisocial with his classmates, confrontational with his teachers, and emotionally estranged from his family. Read the full text of “Paul’s Case” here.

“Bliss” by Katherine Mansfield (1918)

Bliss (1918) is a short story by Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923), the New Zealand-born British author recognized for revolutionizing the modern English short story form. Bliss is one of the works that put her on the literary map. Bertha Young, the main character, is a happy yet somewhat naïve young wife. The story takes place during a dinner party she hosts with her husband Harry.

One of the story’s themes is the classic one self-knowledge. But it was more of a rarity to explore queer themes in early twentieth-century literature. Read the full text of “Bliss” here.

“Sweat” by Zora Neale Hurston (1926)

In the introduction to his analysis of “Sweat” by Zora Neale Hurston, Jason Horn states that the scope of this brief piece reaches farther than most novels. Within this small space, Hurston addresses a number of themes, such as the trials of femininity, which she explores with compelling and efficient symbolism. It is nuanced and eloquently compact as Hurston maximizes each word, object, character, and plot point to create an impassioned and enlightening narrative.

This is woven together with an ecocritical/ecofeminist perspective that links the feminine realm with the natural realm, which is then contrasted with the human realm.

“Flowering Judas” by Katherine Anne Porter (1930)

Sarah Wyman’s analysis of “Flowering Judas” by Katherine Anne Porter begins: Taking a cue from Judas who revealed Christ’s identity to his persecutors with a kiss, “Flowering Judas” revolves around the theme of betrayal. Laura, an adventurous young woman from the southwest U.S. has an identity crisis, questioning her own values and her involvement in the Mexican revolution of 1910 – 1920.

Characteristic of Porter’s heroines, Laura is one for whom personal choices have serious political implications. Her inauthentic denial of self and her complicity in another character’s death lead her to rethink her own status as savior or betrayer.

“Tell Me a Riddle” by Tillie Olsen (1961)

Tell Me a Riddle, a collection of four short stories by Tillie Olsen was published after a long gap in this American writer’s oeuvre. The book opens with “I Stand Here Ironing,” a first-person, autobiographical narrative of the frustration of motherhood, isolation, and poverty.

The last piece in the collection, “Tell Me a Riddle,” is arguably Olsen’s best-known work. It’s the story of a working-class couple that also poignantly explores the author’s favored themes of poverty and gender. The slender short story received much critical acclaim. “Tell Me a Riddle” was adapted into a 1980 movie starring Melvyn Douglas and Lila Kedrova. It’s part of the aforementioned short story collection and other collections of Olsen’s short works.

“The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson (1949)