Nava Atlas's Blog, page 75

December 22, 2018

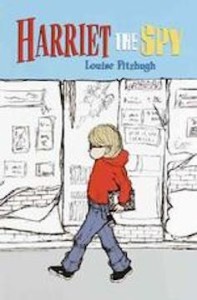

Quotes from Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh

Louise Fitzhugh (1928 – 1974 hailed from Memphis, Tennessee. She had a varied education, studying art in Italy and France as well as New York City, where she took courses at the Art Students League and at Cooper Union. It may not be surprising that she studied child psychology, art, and literature, as these seem to entwine in the books she produced.

It was Harriet the Spy (1964) that put her on the literary map and cemented her legacy. A brief description from the 1964 HarperCollins edition:

“Harriet is determined to grow up to be Harriet M. Welsch, the famous writer; and in order to get a head start on her career, she spends part of every day on her spy route “observing” and noting down, in her singular, caustic, comic way, everything of interest to her.

The first blow falls when Ole Golly leaves, the second when Harriet’s schoolmates find and read her notebook. Their anger and retaliation, Harriet’s unexpected responses, and the ingenious methods her teachers and parents use to help turn Harriet the Spy into Harriet M. Wesch combine to make a touching and unusual story.”

This hugely popular children’s classic novel has been both beloved and banned through the years, though it has never been ignored. Here are some quotes from this enduring book, beloved by generations of readers.

. . . . . . . . . .

“Don’t mess with anybody on a Monday. It’s a bad, bad day.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“People who love work, love life.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There are as many ways to live as there are people.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Little lies that make people feel better are not bad, like thanking someone for a meal they made even if you hated it, or telling a sick person they look better when they don’t, or someone with a hideous new hat that it’s lovely. But to yourself you must tell the truth.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She found that when she didn’t have a notebook it was hard for her to think. The thoughts came slowly, as though they had to squeeze through a tiny door to get to her, whereas when she wrote, they flowed out faster than she could put them down. She sat very stupidly with a blank mind until finally ‘I feel different’ came slowly to her mind.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Louise Fitzhugh

. . . . . . . . . .

“When people don’t do anything they don’t think anything, and when people don’t think anything there’s nothing to think about them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She hated math. She hated math with every bone in her body. She spent so much time hating it that she never had time to do it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Life is a struggle and a good spy goes in there and fights.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“‘I want to remember everything. And I want to know everything.’

‘Well, you must realize, Harriet, knowing everything won’t do you a bit of good unless you use it to put beauty in this world. True or false?’

‘True.’

‘Of course it is.'”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I feel all the same things when I do things alone as when Ole Golly was here. The bath feels hot, the bed feels soft, but I feel there’s a funny little hole in me that wasn’t there before, like a splinter in your finger, but this is somewhere above my stomach.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Harriet was scribbling furiously in her notebook.

‘What are you writing?’ Sport asked

‘I’m taking notes on all those people who are sitting over there.’

‘Why?’

‘ Aw, Sport” — Harriet was exasperated — ‘because I’ve seen them and I want to remember them.'”

. . . . . . . . . .

“When somebody goes away there’s things you want to tell them. When somebody dies maybe that’s the worst thing. You want to tell them things that happen after.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I wonder if when you dream about somebody they dream about you.”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Harriet the Spy

and Harriet the Spy on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“When is it too old to have fun? You can’t be too old to spy except if you were fifty you might fall off a fire escape, but you could spy around on the ground a lot.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“What was sickening about a tomato sandwich? Harriet felt the taste in her mouth. Were they crazy? It was the best taste in the world. Her mouth watered at the memory of the mayonnaise.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“When she picked up her lunch the bag felt very light. She reached inside and there was only crumpled paper. They had taken her tomato sandwich. Someone had taken it. She couldn’t get over it. This was completely against the rules of the school. No one was supposed to steal your tomato sandwich.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I am going to finish up these memoirs and sell them to the book of the month selection then my mother will get the book in the mail as a surprise. Then I will be so rich and famous that people will bow in the streets and say there goes Harriet M. Welsch — she is very famous you know. Rachel Hennessey will plotz.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There are as many ways to live in this world as there are people in this world, and each one deserves a closer look.”

“‘What does it feel like to get paid for what you write?’ What would he say? She waited breathlessly.

‘It’s heaven, baby, sheer heaven.'”

. . . . . . . . . .

“This stuff is beyond crap. It is what crap wants to be when it grows up.”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Harriet the Spy

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Wikipedia

Unapologetically Harriet, the Misfit Spy on NPR

Harriet the Spy on Amazon

Film version of Harriet the Spy

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 19, 2018

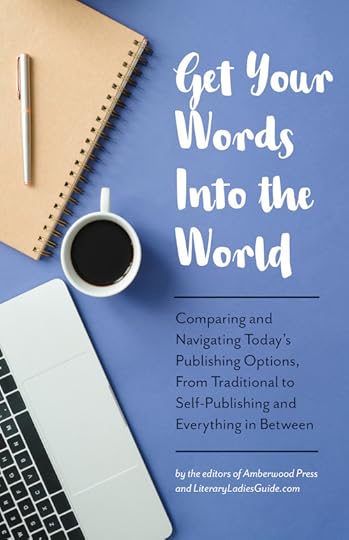

Get Your Words Into the World

Literary Ladies Guide is pleased to announce the publication of Get Your Words Into the World: Comparing and Navigating Today’s Publishing Options, From Traditional to Self-Publishing and Everything in Between. This concise guide will help you sort out what path might be best for you and presents lots of free resources and links, whether you’re looking for an agent, thinking of being an “indie author,” or tempted to try short-run printing.

You’ll find plenty of “how to write a book” books, plus plenty of advice on websites. There’s also tons of advice on marketing your book once it’s produced. This book tackles the in-between part — navigating the various publishing options available in today’s ever-changing publishing landscape.

This book assumes that you have a book project that’s well in progress or just about ready to find a home in print or digital publishing. Think of this as a map that lays out how to choose not only between traditional and self-publishing and all the variants of these options as well.

We’ll cover how to find an agent, explain what hybrid publishing is about, and introduce the best routes to e-book and print-on-demand publishing.

Find your publishing path

Going from writer to author doesn’t represent an end, but is the beginning of a new path — one that can be filled with success and fulfillment or challenges and pitfalls. Or sometimes both at once! Becoming an Author with a capital A brings with it some distinctive baggage—sometimes an entire set of matched luggage.

When crossing the threshold from writer to author, there’s a sense of having reached a much longed-for destination. But as the French author Colette wrote, “Sit down and put down everything that comes into your head and then you’re a writer. But an author is one who can judge his own stuff’s worth, without pity, and destroy most of it.”

The truth is that you need not become an author to be a writer, and for some, being a writer is enough. But most everyone who writes longs to see their words in print. It’s a journey that can take you to some incredible places if you have the courage to take the first steps onto the path!

Here’s what you’ll find in this guide:

TRADITIONAL PUBLISHING

HOW TO FIND AN AGENT

SUBMITTING DIRECTLY TO PUBLISHERS WITHOUT AN AGENT

AMAZON PUBLISHING

SELF-PUBLISHING

SELF-PUBLISHER SERVICES

THE À LA CARTE ROUTE TO SELF-PUBLISHING

PRINT ON DEMAND

SHORT-RUN BOOK PRINTERS

START A SMALL PRESS

CROWDFUNDING

HYBRID PUBLISHING

POETRY COLLECTIONS AND CHAPBOOKS

BOOK MARKETING IN BRIEF

LEARNING FROM PITFALLS AND DISAPPOINTMENTS

Get Your Words Into the World e-book on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Get Your Words Into the World is available on Amazon as a Kindle e-book and will be available in paperback in January, 2019. If you don’t have a Kindle device, you can download a free Kindle app which allows you to view Kindle books on your computer!

File Size: 906 KB

Print Length: 64 pages

Publication Date: December 16, 2018

Sold by: Amazon Digital Services LLC

Language: English

ASIN: B07LFLKPZ5

Lending

Screen Reader

Enhanced Typesetting

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Get Your Words Into the World appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 17, 2018

10 Poems by Phillis Wheatley from Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773)

When Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral by Phillis Wheatley was published in 1773, it marked several significant accomplishments. It was the first book by a slave to be published in the Colonies, and only the third book by a woman in the American colonies to be published.

Phillis (not her original name) was brought to the North America in 1761 as part of the slave trade. She was bought from the slave market by John Wheatley of Boston, who gave her as a personal servant to his wife, Susanna. She was given the surname of the family, as was customary at the time.

Still just a child when she was made a house slave to the Wheatleys, Phillis displayed impressive intellectual ability. Susanna had her educated along with their daughters, and within a short time, Phillis she was able to read the Bible and write English fluently. This was all the more remarkable at a time when slaves were discouraged from learning to read and write, if not altogether forbidden.

In 1773 Phillis traveled to London with her master’s son, Nathaniel. There, she was admired for her literary talent and poise. Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon, a friend of Susanna Wheatley family, funded the publication of Phillis’s book.

Prior to this journey, Boston publishers had refused to consider the collection for publication, so Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was published in London in late 1773. Phillis was about twenty years old at the time. Here’s a selection of 10 poems from this volume, her only published collection.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Phillis Wheatley, first African-American Poet

. . . . . . . . . .

The author’s Preface

THE following POEMS were written originally for the Amusement of the Author, as they were the Products of her leisure Moments. She had no Intention ever to have published them; nor would they now have made their Appearance, but at the Importunity of many of her best, and most generous Friends; to whom she considers herself, as under the greatest Obligations.

As her Attempts in Poetry are now sent into the World, it is hoped the Critic will not severely censure their Defects; and we presume they have too much Merit to be cast aside with Contempt, as worthless and trifling Effusions.

As to the Disadvantages she has laboured under, with Regard to Learning, nothing needs to be offered, as her Master’s Letter in the following Page will sufficiently show the Difficulties in this Respect she had to encounter.

With all their Imperfections, the Poems are now humbly submitted to the

Perusal of the Public.

On Being Brought from Africa to America.

‘Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

On Virtue.

O Thou bright jewel in my aim I strive

To comprehend thee. Thine own words declare

Wisdom is higher than a fool can reach.

I cease to wonder, and no more attempt

Thine height t’explore, or fathom thy profound.

But, O my soul, sink not into despair,

Virtue is near thee, and with gentle hand

Would now embrace thee, hovers o’er thine head.

Fain would the heav’n-born soul with her converse,

Then seek, then court her for her promis’d bliss.

Auspicious queen, thine heav’nly pinions spread,

And lead celestial Chastity along;

Lo! now her sacred retinue descends,

Array’d in glory from the orbs above.

Attend me, Virtue, thro’ my youthful years!

O leave me not to the false joys of time!

But guide my steps to endless life and bliss.

Greatness, or Goodness, say what I shall call thee,

To give an higher appellation still,

Teach me a better strain, a nobler lay,

O thou, enthron’d with Cherubs in the realms of day!

A Farewell to America.

I.

Adieu, New-England’s smiling meads,

Adieu, th’ flow’ry plain:

I leave thine op’ning charms, O spring,

And tempt the roaring main.

II.

In vain for me the flow’rets rise,

And boast their gaudy pride,

While here beneath the northern skies

I mourn for health deny’d.

III.

Celestial maid of rosy hue,

Oh let me feel thy reign!

I languish till thy face I view,

Thy vanish’d joys regain.

IV.

Susannah mourns, nor can I bear

To see the crystal shower

Or mark the tender falling tear

At sad departure’s hour;

V.

Not regarding can I see

Her soul with grief opprest

But let no sighs, no groans for me

Steal from her pensive breast.

VI.

In vain the feather’d warblers sing

In vain the garden blooms

And on the bosom of the spring

Breathes out her sweet perfumes.

VII.

While for Britannia’s distant shore

We weep the liquid plain,

And with astonish’d eyes explore

The wide-extended main.

VIII.

Lo! Health appears! celestial dame!

Complacent and serene,

With Hebe’s mantle oe’r her frame,

With soul-delighting mien.

IX.

To mark the vale where London lies

With misty vapors crown’d

Which cloud Aurora’s thousand dyes,

And veil her charms around.

X.

Why, Phoebus, moves thy car so slow?

So slow thy rising ray?

Give us the famous town to view,

Thou glorious King of day!

XI.

For thee, Britannia, I resign

New-England’s smiling fields;

To view again her charms divine,

What joy the prospect yields!

XII.

But thou! Temptation hence away,

With all thy fatal train,

Nor once seduce my soul away,

By thine enchanting strain.

XIII.

Thrice happy they, whose heavenly shield

Secures their souls from harm,

And fell Temptation on the field

Of all its pow’r disarms.

. . . . . . . . . .

Phillis Wheatley: Complete Writings on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . . .

On Imagination.

Thy various works, imperial queen, we see,

How bright their forms! how deck’d with pomp by thee!

Thy wond’rous acts in beauteous order stand,

And all attest how potent is thine hand.

From Helicon’s refulgent heights attend,

Ye sacred choir, and my attempts befriend:

To tell her glories with a faithful tongue,

Ye blooming graces, triumph in my song.

Now here, now there, the roving Fancy flies,

Till some lov’d object strikes her wand’ring eyes,

Whose silken fetters all the senses bind,

And soft captivity involves the mind.

Imagination! who can sing thy force?

Or who describe the swiftness of thy course?

Soaring through air to find the bright abode,

Th’ empyreal palace of the thund’ring God,

We on thy pinions can surpass the wind,

And leave the rolling universe behind:

From star to star the mental optics rove,

Measure the skies, and range the realms above.

There in one view we grasp the mighty whole,

Or with new worlds amaze th’ unbounded soul.

Though Winter frowns to Fancy’s raptur’d eyes

The fields may flourish, and gay scenes arise;

The frozen deeps may break their iron bands,

And bid their waters murmur o’er the sands.

Fair Flora may resume her fragrant reign,

And with her flow’ry riches deck the plain;

Sylvanus may diffuse his honours round,

And all the forest may with leaves be crown’d:

Show’rs may descend, and dews their gems disclose,

And nectar sparkle on the blooming rose.

Such is thy pow’r, nor are thine orders vain,

O thou the leader of the mental train:

In full perfection all thy works are wrought,

And thine the sceptre o’er the realms of thought.

Before thy throne the subject-passions bow,

Of subject-passions sov’reign ruler thou;

At thy command joy rushes on the heart,

And through the glowing veins the spirits dart.

Fancy might now her silken pinions try

To rise from earth, and sweep th’ expanse on high:

From Tithon’s bed now might Aurora rise,

Her cheeks all glowing with celestial dies,

While a pure stream of light o’erflows the skies.

The monarch of the day I might behold,

And all the mountains tipt with radiant gold,

But I reluctant leave the pleasing views,

Which Fancy dresses to delight the Muse;

Winter austere forbids me to aspire,

And northern tempests damp the rising fire;

They chill the tides of Fancy’s flowing sea,

Cease then, my song, cease the unequal lay.

To S. M., a Young African Painter, on Seeing His Works.

To show the lab’ring bosom’s deep intent,

And thought in living characters to paint,

When first thy pencil did those beauties give,

And breathing figures learnt from thee to live,

How did those prospects give my soul delight,

A new creation rushing on my sight?

Still, wond’rous youth! each noble path pursue;

On deathless glories fix thine ardent view:

Still may the painter’s and the poet’s fire,

To aid thy pencil and thy verse conspire!

And may the charms of each seraphic theme

Conduct thy footsteps to immortal fame!

High to the blissful wonders of the skies

Elate thy soul, and raise thy wishful eyes.

Thrice happy, when exalted to survey

That splendid city, crown’d with endless day,

Whose twice six gates on radiant hinges ring:

Celestial Salem blooms in endless spring.

Calm and serene thy moments glide along,

And may the muse inspire each future song!

Still, with the sweets of contemplation bless’d,

May peace with balmy wings your soul invest!

But when these shades of time are chas’d away,

And darkness ends in everlasting day,

On what seraphic pinions shall we move,

And view the landscapes in the realms above?

There shall thy tongue in heav’nly murmurs flow,

And there my muse with heav’nly transport glow;

No more to tell of Damon’s tender sighs,

Or rising radiance of Aurora’s eyes;

For nobler themes demand a nobler strain,

And purer language on th’ ethereal plain.

Cease, gentle Muse! the solemn gloom of night

Now seals the fair creation from my sight.

To the University of Cambridge, in New England.

WHILE an intrinsic ardor prompts to write,

The muses promise to assist my pen;

‘Twas not long since I left my native shore

The land of errors, and Egyptian gloom:

Father of mercy, ’twas thy gracious hand

Brought me in safety from those dark abodes.

Students, to you ’tis giv’n to scan the heights

Above, to traverse the ethereal space,

And mark the systems of revolving worlds.

Still more, ye sons of science ye receive

The blissful news by messengers from heav’n,

How Jesus’ blood for your redemption flows.

See him with hands out-stretcht upon the cross;

Immense compassion in his bosom glows;

He hears revilers, nor resents their scorn:

What matchless mercy in the Son of God!

When the whole human race by sin had fall’n,

He deign’d to die that they might rise again,

And share with him in the sublimest skies,

Life without death, and glory without end.

Improve your privileges while they stay,

Ye pupils, and each hour redeem, that bears

Or good or bad report of you to heav’n.

Let sin, that baneful evil to the soul,

By you be shun’d, nor once remit your guard;

Suppress the deadly serpent in its egg.

Ye blooming plants of human race divine,

An Ethiop tells you ’tis your greatest foe;

Its transient sweetness turns to endless pain,

And in immense perdition sinks the soul.

On the Death of a young Lady of Five Years of Age.

FROM dark abodes to fair etherial light

Th’ enraptur’d innocent has wing’d her flight;

On the kind bosom of eternal love

She finds unknown beatitude above.

This known, ye parents, nor her loss deplore,

She feels the iron hand of pain no more;

The dispensations of unerring grace,

Should turn your sorrows into grateful praise;

Let then no tears for her henceforward flow,

No more distress’d in our dark vale below,

Her morning sun, which rose divinely bright,

Was quickly mantled with the gloom of night;

But hear in heav’n’s blest bow’rs your Nancy fair,

And learn to imitate her language there.

“Thou, Lord, whom I behold with glory crown’d,

“By what sweet name, and in what tuneful sound

“Wilt thou be prais’d? Seraphic pow’rs are faint

“Infinite love and majesty to paint.

“To thee let all their graceful voices raise,

“And saints and angels join their songs of praise.”

Perfect in bliss she from her heav’nly home

Looks down, and smiling beckons you to come;

Why then, fond parents, why these fruitless groans?

Restrain your tears, and cease your plaintive moans.

Freed from a world of sin, and snares, and pain,

Why would you wish your daughter back again?

No—bow resign’d. Let hope your grief control,

And check the rising tumult of the soul.

Calm in the prosperous, and adverse day,

Adore the God who gives and takes away;

Eye him in all, his holy name revere,

Upright your actions, and your hearts sincere,

Till having sail’d through life’s tempestuous sea,

And from its rocks, and boist’rous billows free,

Yourselves, safe landed on the blissful shore,

Shall join your happy babe to part no more.

To a LADY and her Children, on the Death

of her Son and their Brother.

O’ERWHELMING sorrow now demands my song:

From death the overwhelming sorrow sprung.

What flowing tears? What hearts with grief opprest?

What sighs on sighs heave the fond parent’s breast?

The brother weeps, the hapless sisters join

Th’ increasing woe, and swell the crystal brine;

The poor, who once his gen’rous bounty fed,

Droop, and bewail their benefactor dead.

In death the friend, the kind companion lies,

And in one death what various comfort dies!

Th’ unhappy mother sees the sanguine rill

Forget to flow, and nature’s wheels stand still,

But see from earth his spirit far remov’d,

And know no grief recals your best-belov’d:

He, upon pinions swifter than the wind,

Has left mortality’s sad scenes behind

For joys to this terrestial state unknown,

And glories richer than the monarch’s crown.

Of virtue’s steady course the prize behold!

What blissful wonders to his mind unfold!

But of celestial joys I sing in vain:

Attempt not, muse, the too advent’rous strain.

No more in briny show’rs, ye friends around,

Or bathe his clay, or waste them on the ground:

Still do you weep, still wish for his return?

How cruel thus to wish, and thus to mourn?

No more for him the streams of sorrow pour,

But haste to join him on the heav’nly shore,

On harps of gold to tune immortal lays,

And to your God immortal anthems raise.

An Hymn to the Morning

ATTEND my lays, ye ever honour’d nine,

Assist my labours, and my strains refine;

In smoothest numbers pour the notes along,

For bright Aurora now demands my song.

Aurora hail, and all the thousand dies,

Which deck thy progress through the vaulted skies:

The morn awakes, and wide extends her rays,

On ev’ry leaf the gentle zephyr plays;

Harmonious lays the feather’d race resume,

Dart the bright eye, and shake the painted plume.

Ye shady groves, your verdant gloom display

To shield your poet from the burning day:

Calliope awake the sacred lyre,

While thy fair sisters fan the pleasing fire:

The bow’rs, the gales, the variegated skies

In all their pleasures in my bosom rise.

See in the east th’ illustrious king of day!

His rising radiance drives the shades away—

But Oh! I feel his fervid beams too strong,

And scarce begun, concludes th’ abortive song.

An Hymn to the Evening

SOON as the sun forsook the eastern main

The pealing thunder shook the heav’nly plain;

Majestic grandeur! From the zephyr’s wing,

Exhales the incense of the blooming spring.

Soft purl the streams, the birds renew their notes,

And through the air their mingled music floats.

Through all the heav’ns what beauteous dies are spread!

But the west glories in the deepest red:

So may our breasts with ev’ry virtue glow,

The living temples of our God below!

Fill’d with the praise of him who gives the light,

And draws the sable curtains of the night,

Let placid slumbers sooth each weary mind,

At morn to wake more heav’nly, more refin’d;

So shall the labours of the day begin

More pure, more guarded from the snares of sin.

Night’s leaden sceptre seals my drowsy eyes,

Then cease, my song, till fair Aurora rise.

More …

Read Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) in its entirety on Project Gutenberg

An analysis of Phillis Wheatley’s poems

On Phillis Wheatley – Poetry Foundation

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 10 Poems by Phillis Wheatley from Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 16, 2018

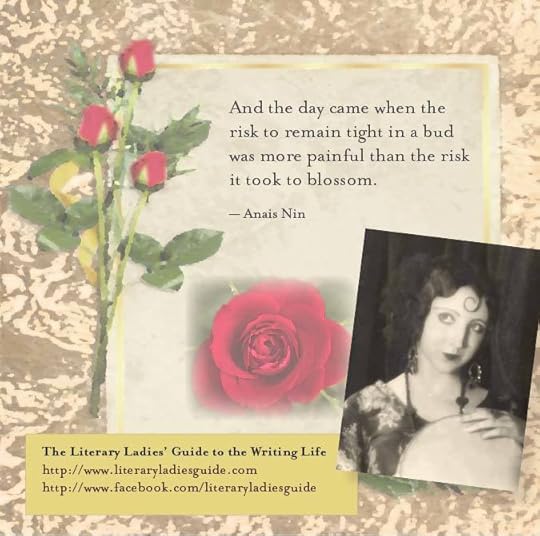

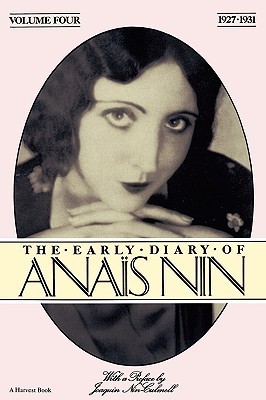

Anaïs Nin

Anaïs Nin (February 21, 1903 – January 14, 1977) embodied the practice of writing as a grand passion and a path to delving deeply into the self. In this sense, she foreshadowed the immediacy of today’s world of self-revelatory memoir. She was a splendid and prolific essayist as well.

Best known for her multi-volume series, The Diary of Anaïs Nin, she wrote these journals over the span of more than thirty years (not including her Early Diaries series).

Born in France, her full original name was Angela Anaïs Juana Antolina Rosa Edelmira Nin y Culmell. Her father, Joaquin Nin, a composer, deserted the family when Anaïs was about 11 years old. He and her mother, Rosa Culmell y Vigaraud, were of Cuban descent with traces of French, Spanish, and Danish ancestry.

Anaïs spent her teens in the U.S., starting out in Catholic school. She dropped out, became self-educated, and worked as a model and dancer before returning to Europe in the 1920s.

Writing shaped her life

From the earliest of her diaries, written while still in her teens, to one of her last essays, published just a year before her death in 1977, it’s clear that writing was what she believed shaped her life and gave it meaning.

“… you don’t write for yourself or for others. You write out of a deep inner necessity. If you are a writer, you have to write, just as you have to breathe, or if you’re a singer you have to sing. But you’re not aware of doing it for someone. This need to write was for me as strong as the need to live. I needed to live, but I also needed to record what I lived. It was a second life, it was my way of living in a more heightened way.”

(— from “The Artist as Magician,” an interview, 1973)

An early self-publisher & author of erotica

Early on in her writing career, Anaïs was unable to find a publisher for her work, unable to find any that would take a risk on Under a Glass Bell, a collection of eight short stories. She and her then-husband, Hugh Guiler founded Gemor Press in 1944 and printed an edition.

Three years later, a British publisher agreed to republish the collection, expanded by two novellas and Nin’s famous prose poem, “House of Incest.” Nin’s friend and lover Gore Vidal used his clout to encourage his publisher, Dutton, to publish the collection in the U.S. in 1945.

Nin also broke ground as a writer of female erotica —The Delta of Venus and Little Birds most notably, which were published posthumously. She wrote the pieces in Delta for a dollar a page in the 1940s.The last of the Diaries was published in the 1980s, also after her death.

. . . . . . . . . .

Anaïs Nin page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

A prolific love life

Anaïs had many well-known love affairs, most famously with Henry Miller and his wife, June Miller, which she wrote of, fittingly, in Henry and June. She was also involved with Gore Vidal, Edmund Wilson, and Otto Rank.

Her first husband was Hugh Guiler, with whom she had an open marriage. She was still married to him when she married Rupert Pole, and eventually the first marriage was annulled.

The Diaries

Though it’s generally believed that she wrote her Diaries with an eye toward eventual publication, it wasn’t until the 1960s that they were published and acclaimed as feminist classics, portraying one woman’s lifelong voyage of self-discovery.

The Diaries were largely written in the years 1931 to 1974. Her personal quest for self-knowledge ended up becoming an in-depth, honest look at the universal issues affecting women in all walks of life. “It’s all right for a woman to be, above all, human. I am a woman first of all,” she wrote.

By the standards of today’s confessional media, Nin’s frank writings may no longer seem as revolutionary as they did just a generation ago. In the final volume of the Diaries (Volume Seven, 1966-1974), she delights in sharing snippets from the countless letters of gratitude she received from women everywhere, in all walks of life, for example:

“The Diaries wakened me, made me relive my life, enjoy it, find new aspects to dream about; you gave me a second life.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Anaïs Nin’s Diaries: From the Personal to the Universal

. . . . . . . . . .

The meaning of the Diary — in her own words

“Having been told so often how wrong it is to write about one’s self—how I should take the self out of the Diary—I never expected the consequences. Because I gave of myself, many women felt I spoke for them, liberated them from secrecy and reticence.

I did not expect to get letters from women working in offices, on farms, married and lonely in little towns, nurses, librarians, students, runaways, dropouts, pregnant women without husbands, women in the middle of a divorce. Suddenly I was discovering a world.

The dominant theme of the letters was loneliness and lack of confidence in whatever the writers undertook. The miracle was that my diary made them eloquent, confessional…I discovered women with talents never used before. One woman sent me her first drawing made after reading the Diary. The Diary cured depression, opened secret chambers.

There was no ego in the Diary, there was only a voice which spoke for thousands, made links, bonds, friendships. All the clichés about self-absorption were destroyed. There was no one self. We were all one. The more I developed my self, the less mine it became. If all of us were willing to expose this self, we would feel neither alone nor unique.

I was so tired of the platitudes hurled at me. The two most misinterpreted words in the world: narcissism and ego. The simple truth was that some of us recognized the need to develop, grow, expend—occupations which are the opposite of those two words. To desire to grow means you are not satisfied with the self as it is, and the ego is exacting, not indulgent.”

— Anaïs Nin, from The Diary of Anaïs Nin, Volume Seven, 1966-1974

A feminist icon

After achieving worldwide recognition after the first volume of the Diaries in 1966, Nin became a feminist icon, was a frequent speaker on college campuses and at feminist events. Later in her life, she distanced herself from the more militant, political factions of the second-wave feminist movement.

Anaïs Nin died of cancer on January 14, 1977, in Los Angeles, California.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: Anaïs Nin Quotes on Writing, Life, and Love

More about Anaïs Nin on this site

The Young Anaïs Nin: Compelled to Write; So Unsure of Herself

Nin on Why She Published the Delta of Venus

Nin’s Diaries: From the Personal to the Universal

Nin Quotes on Writing, Life, and Love

Anaïs Nin on Writing to Give Depth and Meaning to Life

Major Works

The Early Diary of Anaïs Nin (four volumes)

The Diary of Anaïs Nin (seven volumes)

Henry and June

Delta of Venus

Little Birds

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays

Incest: From a Journal of Love

Biographies

Anaïs Nin: A Biography by Deirdre Bair

Anaïs: The Erotic Life of Anaïs Nin by Noel Riley Fitch

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Nin’s books on Goodreads

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Anaïs Nin appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 14, 2018

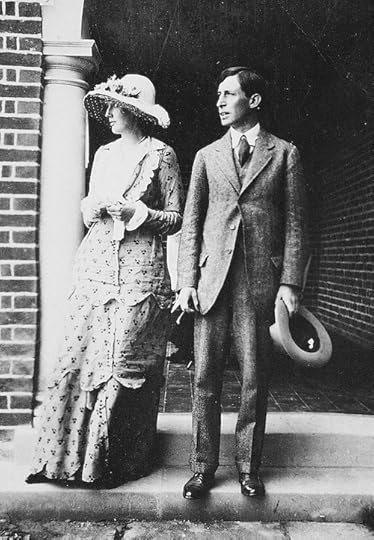

Becoming Virginia Woolf: How Leonard Woolf Wooed Virginia Stephen

Virginia Stephen first met Leonard Woolf while visiting her brother Thoby at Trinity College at Cambridge in 1900. She wore a white dress and carried a parasol, looking like “the most Victorian of Victorian young ladies,” as Leonard described her. Leonard and Virginia Woolf, as she would later be known, were destined to be together, though it took considerable persistence and many proposals on his part before she agreed to marry him.

According to The American Reader, “Virginia and her elder sister, Vanessa, were described by Leonard Woolf as ‘young women of astonishing beauty …. It was almost impossible for a man not to fall in love with them.’” Brilliant as well as exquisitely beautiful, Virginia attracted many admirers, both male and female.

“You must marry Virginia”

In 1909, Lytton Strachey, a mutual friend of Virginia and Leonard’s proposed to her, and she turned him down. He immediately wrote to Leonard, who was working as a civil servant in Ceylon at the time:

“Your destiny is clearly marked out for you, but will you allow it to work? You must marry Virginia. She’s sitting waiting for you, is there any objection? She’s the only woman in the world with sufficient brains, it’s a miracle that she should exist; but if you’re not careful you’ll lose the opportunity … She’s young, wild, inquisitive, discontended, [sic] and longing to be in love.”

Leonard was intrigued and wrote back. “Do you think Virginia would have me? Wire to me if she accepts. I’ll take the next boat home.” It’s almost as if he expected his friend to make the proposal for him.

Virginia didn’t respond, thinking the offer to be a joke. Nothing more was said until Leonard returned to England at the end of 1911. After his first in-person proposal in January 1912, he resigned from the civil service, partly in the hope that Virginia would accept his proposal.

He moved into the house in Bloomsbury that Virginia shared with her brother and continued to court her, proposing several times.

. . . . . . . . . .

The iconic image of the young Virginia Stephen

. . . . . . . . . .

Reluctant to marry

Virginia’s reluctance to marry was fueled by fear of sex and the attendant emotional involvement. She wasn’t physically attracted to Leonard, and the fact that he was a Jew was, in her eyes, not in his favor.

According to Frank McLynn, author of Famous Letters: Messages & Thoughts that Shaped Our World (1993): “Virginia had mixed feelings about marriage and resented the role prescribed for women in British society.

She was also repelled by the idea of sex with a man, after the trauma of a childhood in which she was molested by her two older half-brothers.” More about this is detailed in Virginia Woolf: The Impact of Childhood Sexual Abuse on Her Life and Work by Louise DeSalvo.

A blunt letter

In a 1912 letter to Leonard, Virginia was blunt about her reservations, not holding back her true feelings:

May 1, 1912

Dearest Leonard,

To deal with the facts (my fingers are so cold I can hardly write) I shall be back about 7 tomorrow, so there will be time to discuss—but what does it mean? you can’t take the leave, I suppose if you are going to resign certainly at the end of it. Anyhow, it shows what a career you’re ruining!

Well then, as to all the rest. It seems to me that I am giving you a great deal of pain—some in the most casual way—and therefore I ought to be as plain with you as I can, because half the time I suspect, you’re in a fog which I don’t see at all. Of course I can’t explain what I feel—these are some of the things that strike me.

The obvious advantages of marriage stand in my way. I say to myself. Anyhow, you’ll be quite happy with him; and he will give you companionship, children, and a busy life—then I say By God, I will not look upon marriage as a profession. The only people who know of it, all think it suitable; and that makes me scrutinise my own motives all the more.

Then, of course, I feel angry sometimes at the strength of your desire. Possibly, your being a Jew comes in also at this point. You seem so foreign. And then I am fearfully unstable. I pass from hot to cold in an instant, without any reason; except that I believe sheer physical effort and exhaustion influence me.

All I can say is that in spite of these feelings which go on chasing each other all day long when I am with you, there is some feeling which is permanent , and growing. You want to know of course whether it will ever make me marry you.

How can I say? I think it will, because there seems no reason why it shouldn’t—But I don’t know what the future will bring. I’m half afraid of myself. I sometimes feel that no one ever has or ever can share something — It’s the thing that makes you call me like a hill, or a rock.

Again, I want everything — love, children, adventure, intimacy, work. (Can you make any sense out of this ramble? I am putting down one thing after another.) So I go from being half in love with you, and wanting you to be with me always, and known everything about me, to the extreme of wildness and aloofness.

I sometimes think that if I married you, I could have everything — and then — it is the sexual side of it that comes between us? As I told you brutally the other day, I feel no physical attraction in you. There are moments — when you kissed me the other day was one—when I feel no more than a rock.

And yet your caring for me as you do almost overwhelms me. It is so real, and so strange. Why should you? What am I really except a pleasant attractive creature? But its [sic] just because you care so much that I feel I’ve got to care before I marry you. I feel I must give you everything and that if I can’t, well, marriage would only be second-best for you as well as for me.

If you can still go on, as before, letting me find my own way, that is what would please me best; and then we must both take the risks. But you have made me very happy too. We both of us want a marriage that is a tremendous living thing, always alive, always hot, not dead and easy in parts as most marriages are. We ask a great deal of life, don’t we? Perhaps we shall get it; then, how splendid!

One doesn’t get much said in a letter does one? I haven’t touched upon the enormous variety of things that have been happening here—but they can wait…

Yrs.

VS

Virginia relents

Leonard must have worn her down. Virginia finally accepted his proposal later that same month. She wrote to her friend Violet Dickinson of the engagement:

“My Violet, I’ve got a confession to make. I’m going to marry Leonard Woolf. He’s a penniless Jew. I’m more happy than anyone ever said was possible – but I insist upon your liking him too. May we both come on Tuesday? Would you rather I come alone? He was a great friend of Thoby’s, went out to India – came back last summer when I saw him, and he has been living here since the winter.”

The two married on August 10, 1912. She was thirty, he was thirty-one.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Just one year later, Virginia attempted to commit suicide with a large dose of verona, a sedative. Doctors discouraged her from having children due to her struggles with mental illness, which, despite her aversion to sex, she found heartbreaking.

Throughout their long marriage, Virginia continued to have other relationships, primarily with women (most famously, with Vita Sackville-West). Leonard seemed to tacitly approve of this arrangement.

A marriage of minds, a tragic end

The marriage of Leonard and Virginia Woolf was a partnership of minds, if not a romantic one, with a great deal of affection and mutual respect. Leonard could not have been a more nurturing husband. He saw Virginia through bouts of mania, depression, and suicide attempts. Most of all, he created a nurturing environment that made it possible for her to create the brilliant body of work that she ultimately produced.

When Virginia Woolf committed suicide in March of 1941, her note to Leonard said, “I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The post Becoming Virginia Woolf: How Leonard Woolf Wooed Virginia Stephen appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 12, 2018

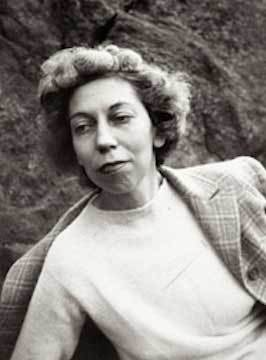

Eudora Welty

Eudora Welty (April 13, 1909 – July 23, 2001) was an American author whose work spanned several genres — novels, short stories, and memoir. Much of her writing focused on realistic human relationships — conflict, community, interaction, and influence. As a Southern writer, a sense of place was an important theme running though her work.

Welty grew up in a close-knit, contented family in Jackson, Mississippi. Her parents instilled a love of education, curiosity, and reading to her and to her brothers, with whom she was close. She was always a star student, from early grades through college. She earned her Bachelor’s degree from the University of Wisconsin.

She did her graduate work at Columbia University School of Business, heeding her father’s suggestion to study advertising. But since she finished her degree just as the depression was worsening, she struggled to find work.

Photography and early writings

The various jobs Welty took during the 1930s — for a radio station, as a society columnist, and publicity agent for the Works Progress Administration — helped make ends meet, but what gave her most satisfaction was taking photographs. She received marginal success in exhibiting them, but few were published, as she desired, until later in her life.

She had a breakthrough success with a short story, “Death of a Traveling Salesman.” It was published in a literary magazine whose editor called it “one of the best stories we have ever read.” After it was published in 1936; after that she found it easier to sell her stories to various publications. The story also caught the attention of Katherine Anne Porter, who became a mentor to her.

Her first collection of short stories, A Curtain of Green and Other Stories, was published in 1941, and featured elements of the so-called Southern grotesque.

She was a private person, and not much is known about her personal life. Though she traveled widely, she always returned to Jackson, Mississippi, and spent her later years living in the home that had belonged to her family.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

10 Inspiring Thoughts on Writing by Eudora Welty

. . . . . . . . . .

A writer in command of her craft

Welty spent much of her life in the Mississippi Delta and the community out of which her most iconic writings grew. Her early novel, Delta Wedding (1946), looks at the world of adult interactions and love through the eyes of a child.

What stands out in Welty’s novels, stories, and memoirs is her ability to capture the texture of community and, to be a bit trite, a sense of place. Her work explores both separateness of the individual and the healing potential of love.

Welty’s writing style varied, simply because she was in command of it. Her stories and novels could be seen as quaint and understated or else wonderfully strange and funny. The Robber Bridegroom (1942), set in Mississippi of the late 1700s, made use of legend. As a whole, many of her works cross the boundaries of nostalgia for a culture that has had its day, and an examination of the inner lives of the characters.

Other works were daring: After Medgar Evers was murdered in Mississippi, she wrote a short story in the voice of the assassin, “Where Is the Voice Coming From?” It was published in The New Yorker.

Other well-know novels included The Ponder Heart (1954), which has comic elements, and Losing Battles (1970), a beautifully drawn portrait of a Southern family.

. . . . . . . . . .

Eudora Welty’s 7 Thoughtful Idea on the Art of Reading

. . . . . . . . . .

Master of the short story form

Among Welty’s most notable works are her short stories. Her skill in this form, which she returned to throughout her career, produced some of her finest pieces of fiction. The Collected Stories of Eudora Welty, a later volume that gathered all of her published short stories, introduced them as follows:

“Although their events and settings varied, and they range as far from Miss Welty’s native Mississippi as Cork and Naples, they spring from a distinctive Southern sensibility, from the author’s response to the place where she has always lived, from long familiarity with the thoughts and feelings of ordinary people around her.

Yet the characters in her stories are anything but ordinary; in the commonplace she perceives what is unique. She is sensitively tuned to their voices and their minds, whether she is in the skin of a beautician, a salesman, or a jazz player.

Time is as important an element in Eudora Welty’s writing as place or character She has said that one cannot live in the South without being conscious of its history. “

RELATED POSTS

Contemplative Quotes by Eudora Welty

Eudora Welty: 7 Thoughtful Ideas on the Art of Reading

An Interview with Eudora Welty

An accomplished photographer

It’s not as widely known that Eudora Welty was an accomplished documentary photographer. She took thousands of photos from the 1930s through the 1950s. Most of her photos depicted Americans of different economic and social classes during the Great Depression and beyond.

The 1989 book Eudora Welty: Photographs collected 250 representative photographs from the few thousand that she took during those decades. Describing her photographic craft, the book notes:

“Although her camera’s view finder compresses much, like the frame in which she conceives her fiction, it finds elements that convey her deep compassion and her artist’s sensibilities.

From the confines of her native Mississippi, these photographs unfold the world of Eudora Welty’s art, reaching, extending, and exploring. In the Deep South of Depression times, when she began writing, she discovered the place into which she had been born and which would always be her subject …

These photographs reveal that both in her fiction and in the pictures she took it has always been in place, in the special qualities of what is local, that she found her impulse. “I was smitten by the identity of place wherever I was,” she said in 1989, “from Mississippi on — I still am.”

This serves as a definitive book of Welty’s photographs, compromising pictures from her personal collection, from the repository of Welty materials at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, and from One Time, One Place, an album of her Depression-era photographs published in 1971.”

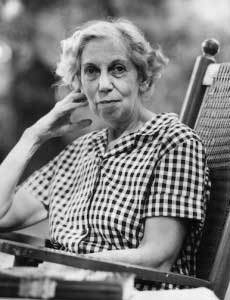

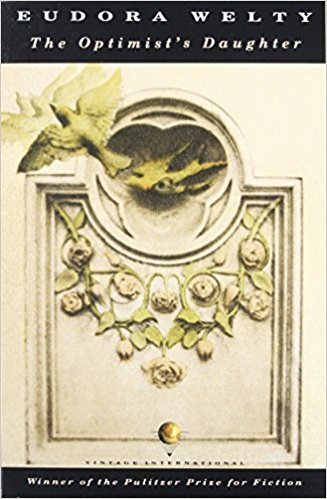

Legacy

Welty won numerous awards for her writing, among them, a Pulitzer Prize (for The Optimist’s Daughter, 1973 — which many critics considered her best novel), an American Book Award, National Medal for Literature, and The Presidential Medal of Freedom. She was a six-time winner of the O. Henry Award for Short Stories.

She also received honorary degrees from Harvard, Yale, and Washington Universities, among others.

Eudora Welty died in 2001 at the age of 92 in Jackson, Mississippi.

Eudora Welty page on Amazon

More about Eudora Welty on this site

An Interview with Eudora Welty (1946)

Eudora Welty: 7 Thoughtful Ideas on the Art of Reading

10 Inspiring Thoughts on Writing by Eudora Welty

Dear Literary Ladies: How can I tell if what I’m writing is any good?

Major works (novels and short story collections; highly selected)

A Curtain of Green and Other Stories (1941)

The Robber Bridegroom (1942)

Delta Wedding (1946)

The Ponder Heart (1954)

Losing Battles (1970)

The Shoe Bird (1964)

The Golden Apples (1949)

The Optimist’s Daughter (1973)

The Collected Stories of Eudora Welt y (1982)

Memoirs, biographies, and photo collections

On Writing (2002) by Eudora Welty

One Writer’s Beginnings (1998) by Eudora Welty

Eudora Welty: Stories, Essays & Memoir

Eudora Welty: A Biography by Suzanne Marrs

A Daring Life: A Biography of Eudora Welty by Carolyn J. Brown

Eudora Welty: Photographs

More Information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Welty’s books on Goodreads

Visit

Eudora Welty House and Gardens

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Eudora Welty appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 10, 2018

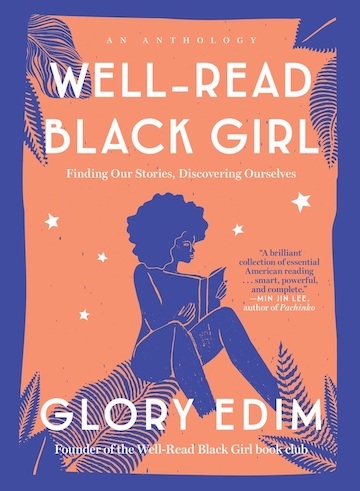

Zora and Me: How I Found Myself by Discovering Zora Neale Hurston

The following essay by Marita Golden is adapted from Well-Read Black Girl: Finding Our Stories, Discovering Ourselves, an anthology edited by Glory Edim:

I saw myself, found myself, and remade myself over and over learning and discovering Zora Neale Hurston. She became and has become a continuing source of possibility and pride for me.

When I think of Zora—and we call her Zora, using her first name only because we want to claim her as sister, mother, friend—I always remember that the Black people chronicled in her novels, folklore, journalism, anthropology, and plays offer to the world a people who are a symphony, not some trembling minor key.

Like Zora I lost my mother at a young age and warred with a father I loved, it seemed, more than life. Like Zora I stepped over the ashes and debris of loss and struck out on my own, carrying grief and anger on my shoulders. Like Zora I lived full to bursting with a universe of dreams and desires to prove to myself and the world. And like Zora everything I proved in the end was made possible by the people who loved me.

“Jump at the sun”

Zora’s mother told her to jump at the sun. My mother told me that one day I would write a book. My father told me stories of Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass years before I learned about them in school. Zora’s voracious appetite for life and experience rebuked, with every barrier she stormed, the idea that Black women are only or forever have to be “the mules of the world.”

In Zora’s blueprint and following her lead, we could be and are artists, anthropologists, philosophers, disturbers of the peace, not afraid to open our mouths or put a foot in that mouth, pull it out, and keep on steppin’.

In her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora allowed me to see the contradictions and complexity of Black life and Black female visions and virtues. Yes, Janie Crawford has “the look,” straight hair, light skin, but her status as sexual trophy offers her no stairway to heaven.

Zora fills her characters’ mouths with the most damning and scathingly satirical colorist comments one could imagine. It was the courageous lambasting of colorist orthodoxy that opened a space for me, a dark brown woman, in the novel.

. . . . . . . . . .

Well-Read Black Girl edited by Glory Edim on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

A master class in the art of living

Zora did not teach me how to write. She taught me how to live, how to laugh, and how to love. Her canon is a master class in the art of living. And it is only through tackling and striding naked and unafraid into the territory, the geography of life and its awful realness and concreteness, that we build an imagination that can find life on a page and withstand the assault of indifference or misinterpretation. Dream a World. Imagine a Life. Be Here Now. That is what Zora mirrored for me to see in myself …

In the 1930s and 1940s, against the backdrop of lynchings and segregation, Zora Neale Hurston proclaimed herself an artist, anthropologist, thinker, novelist, a kind of literary extreme adventurer. Her art was her life, and it made her life a decisive act of art. And unlike a child, her art never let her down, was always obedient, as long as she nurtured it and slammed the door in the face of despair.

I remember reading that in the last days of his life Richard Wright, under surveillance by the French government and the Americans because of his anti-colonial writing, unable to join his wife and daughters in England, wrote over four thousand haikus. Near the end of her life Zora worked as a domestic, struggled to “make ends meet,” yet was nourished by ideas and inspiration for new works.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy these original 1937 reviews of

Their Eyes Were Watching God

. . . . . . . . . .

A writer resurrected

Zora Neale Hurston was one of a legion of Black writers resurrected and reintroduced as a result of the cultural power shifts and changes wrought by the civil rights, Black Power, and women’s movements. Zora was gone, out of print for a while, but you can’t keep a good woman down, and when her time had come, really come (because in her first debut she was ahead of her time), Zora was the drum majorette leading the parade of unleashed Black voices.

How did I discover Zora? How did she become such an integral part of my creative life? I read Alice Walker’s ground- breaking 1975 essay “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” in which she claimed Zora, a fellow Southerner, as her literary ancestor.

And as soon as Their Eyes Were Watching God was reprinted and available, I read it and discovered one of the most revolutionary, authentic, and lyrical voices I had ever encountered. I then read all the books she had written, then gushing into print, and read everything about her that I could find. Her life was as dramatic as the books she wrote, and in everything she wrote she paid homage to the town, the people, and the family that gave her the stories she would relentlessly explore …

Zora made me more than a novelist; she made me a woman of letters, writing fiction and nonfiction because I saw how she sprinted across the borders that supposedly sequestered these genres from each other. Zora wrote until she died, and her writing gave meaning and girth and depth to the life she lived. Not “tragically colored” but magnificently human and brazen and wise and foolish and made of some secret recipe the world had never known.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: Zora Neale Hurston Quotes and Life Lessons

. . . . . . . . . .

She knew I wanted to fly

I see Zora in myself because she knew I wanted to fly so she showed me how to unfurl my wings, and I wanted people to listen, so she modeled being a woman with a mission, a woman on a mission.

Thank you, Zora, for surviving false accusations, poverty, patronage, being buked and scorned, lauded and lifted, speaking your mind, love found, love lost. Rest in peace, and keep rising, sending new missives forth like smoke signals, like the beat of those drums you heard in Jamaica. Like the still fiery drumbeat of your heart.

Excerpted from the book WELL-READ BLACK GIRL Finding Our Stories, Discovering Ourselves by Glory Edim . “Zora and Me” copyright © 2018 by Marita Golden. Published by arrangement with Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All Rights Reserved.

. . . . . . . . . .

Marita Golden is the author of over a dozen works of fiction and nonfiction, Marita Golden’s works are favorites with book clubs, used in college courses from literature to sociology around the country, and are recognized as having added depth and complexity to the canon of contemporary African American writing. Find her online at MaritaGolden.com.

Glory Edim is the founder of Well-Read Black Girl, a Brooklyn-based book club and digital platform that celebrates the uniqueness of Black literature and sisterhood. In fall 2017 she organized the first-ever Well-Read Black Girl Festival. She has worked as a creative strategist for over ten years at startups and cultural institutions. Visit her online at Well-Read Black Girl.

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Zora and Me: How I Found Myself by Discovering Zora Neale Hurston appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 6, 2018

The Poetry of Anne Bradstreet: An Analysis

This concise analysis of the poetry of Anne Bradstreet is excerpted from Who Lived Here? A Baker’s Dozen of Historic New England Houses and Their Occupants by Marc Antony DeWolfe Howe, an eminent editor and writer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Anne Bradstreet (1612 – 1672) was the first writer in the American colonies to be published.

She rejected the prevailing notions of women’s inferiority. That opened her to criticism, not for her work itself, but that she dared to write and make her work public. It was considered unacceptable for women of her time to have a voice. She not only used hers effectively but pushed back at her critics.

The Tenth Muse

In 1647, John Woodbridge, minister of North Andover, married to Anne Bradstreet’s sister, Mercy Dudley, went to England carrying with him a manuscript volume of his sister-in-law’s writings. There, without her knowledge, it was printed in 1650.

The book’s full title page would demand more space that is available here, so this is how it began and ended:

The

Tenth Muse

Lately Sprung up in America,

OR

Severall Poems, compiled

with great variety of Wit

and Learning, full of delight.

. . . . . .

By a Gentlewoman in these parts

This title page contained one further line that must be cited: “With divers other pleasant and serious Poems.” In this category, which should be extended to include the prose Meditations she wrote for her son Simon, the best of Anne Bradstreet is to be found, whether in the London 1650 volume, or in “The Second Edition, Corrected by the Author and enlarged by an Addition of several other Poems found amongst her Peers after her Death.” Boston, 1678.

Woodbridge’s Introduction to The Tenth Muse suggested that “the Reader should pass his sentence that it is the gift of women not only to speak most but to speak best.”

Introductory verses by others, including John Rogers, president of Harvard in the second edition, hailed Anne Bradstreet as both woman and poet. She herself made early assertions of feminism.

I am obnoxious to each carping tongue

Who says my hand a needle better fits

A Poet’s pen all scorn I should thus wrong,

For such despite they cast on female wits;

If what I do prove well, it won’t advance,

They’ll say ’tis stole’n or else it was by chance.

This is in the Prologue to her “Four Elements” and in the poem honoring Queen Elizabeth:

She hath wiped off th’ aspersion of her sex,

That women wisdom lack to play the Rex.

. . . . . . . . .

Nay Masculines, you have thus tax’d us long

But she, though dead, will vindicate our wrong.

Puritan as Anne Bradstreet may have been it would be quite a mistake to recall her as nothing more. Due allowance should be made for her brother in-law’s summary of “her gracious demeanour, her eminent parts, her pious conversation, her courteous disposition, her exact diligence in her place, her discreet managing of her family connections.”

You might also enjoy

5 Poems by Anne Bradstreet, Colonial American Poet

Clear and vigorous thinking

In her writings one may find at this late day direct evidence of clear and vigorous thinking, and of genuinely poetic expression.

Her prose Meditations written for her son Simon — seventy-seven in number, with four added in Latin — look back to Solomon and forward to Ben Franklin. Here is one of them:

“It is reported of the Peacock the priding himself and his gay colors, he ruffles them up; but spying his black feet, he’s soon lets fall his plumes, so that he glorys in his gifts and adornings, should look upon his Corruptions, and that will damn his high thoughts.” But it was in poetry rather than in proverbs that her real distinction lay.

Take, for example, “The Flesh and the Spirit,” ending with lines about the Celeste City in which the Spirit dwells — a rendering in telling verse of a familiar passage in the book of revelations.

Or look, still more attentively, at the long poem, “Contemplations,” which first saw the light in the second edition of her writings. Nature was here her theme — the woods, the river, all the outdoor objects to which she turned from her books. Chiefly of a high seriousness, it’s stanza’s held touches of light fancy — as here:

I heard the merry grasshopper then sing,

The black clad Cricket bear a second part,

They kept one tune, and plaid on the same string,

Seeming to glory in their little Art.

With Addison and Shelley still to come, she wrote this stanza”

When I behold the heavens as in their prime,

And then the earth (though old) still clad in green,

The stones and trees, insensible of time

Nor age nor wrinkle on their front are seen;

Is winter come, and greenness then do fade,

A spring returns, and they more youthful made

But Man grows old, lies down, remains where once

he’s laid.

And in conclusion this stanza, comparable with the best poetry of her own in later times, is found:

O Time, the fatal wrack of mortal things,

That draws oblivious curtains over Kings,

Their sumptuous monuments, men know them not,

Their names without a Record are forgot.

Their parts, their ports, their pomp’s all laid in th’ dust

Nor with nor gold, nor buildings scape time’s rust

But he whose name is grav’d in the white stone

Shall last and shine when all of these are gone.

An admirable husband

From such loftier strains as these, Anne Bradstreet could turned to domestic themes in the burning of her house, love for her children and, most of all, for her admirable husband.

Beginning in Massachusetts is one of the chosen Assistants in the government, Simon Bradstreet served the Colony in successive posts of responsibility … to the dignity of Deputy Governor and Governor.

What ever he may have been to the state he was all in all to that Tenth Muse, his wife. Her short poem beginning:

If ever two were one, then surely we,

If ever man were loved by wife, then thee;

and ending:

Then while we live, in love let’s so persever,

That when we live no more, we may live ever,

Speaks timelessly for conjugal happiness. There are, besides, three letters in verse to her husband, “absent upon Publick employment.” The third of these has a special 17th-century flavor … and, with these lines, as if of Jacobean conceit:

Return my Dear, my joy, my only Love

Unto thy Hind, thy mullet, and thy Dove,

Who neither joyes in pasture, house, nor streams,

The substance gone, O me, these are but dreams,

Together at one Tree, oh let us brouze

And like two Turtles, roost within one house,

And like the Mullets in one River glide,

Let’s still remain but one, till death divide.

Thy loving love and dearest dear,

At home, abroad, and everywhere.

A lofty place among American poets

Anne Bradstreet was not the first, or the last, of poets needing to be stripped of some excess poetical baggage. In fact she had a good deal of it, but there is a residue which, quite apart from the unique circumstances of its origin should hot be permitted to perish. It was long before any other woman took such a place as hers among the poets of America.

Excerpted from Who Lived Here? © 1952 by Marc Antony DeWolfe Howe (1860 – 1960), Bramhall House, New York.

Learn more about Anne Bradstreet

The post The Poetry of Anne Bradstreet: An Analysis appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 3, 2018

Anne Bradstreet

Anne Bradstreet (March 20, 1612 – September 16, 1672) was one of the most prominent early American poets, and the first writer in the American colonies to be published. It was considered unacceptable for women of her time to write, but Anne rejected the prevailing notions of women’s inferiority. She was roundly criticized, not for the work itself, but that she dared to write and make her work public at all.

Young Anne Dudley didn’t attend school, though she received a solid education from her book-loving father, Thomas Dudley. During his year a steward at the estate of the Earl of Lincoln, she had access to the library, and read widely, especially from the classics: Plutarch, Pliny, Virgil, Suetonius, Homer, Ovid, Seneca, and others. She was also steeped in philosophy and Biblical studies.

Leaving England for New England

While still living in her native England, Anne married the highly educated Simon Bradstreet in 1628 when she was sixteen years old. That same year she contracted smallpox, and in her piety, she confessed to Pride and Vanity to the Lord that she worshipped. That, she believed, restored her to health. Two years later, she accompanied her husband and father to the new land. The three-month ocean voyage was a difficult one.

Along with her father, Anne Bradstreet and her husband Simon set off to New England in 1630. She was reluctant to give up the comfortable life of the manor for the wilderness of New England, but as a wife and daughter, she was obligated to follow. Their ship landed in Salem, Massachusetts, in July of 1630.

This imagined image of Anne Bradstreet appeared in 1898

See also: 5 Poems by Anne Bradstreet, Colonial American Poet

They lived for a few years in Newtowne, or what is now Cambridge, MA, and then in Ipswich, before settling in what is now North Andover, Massachusetts. The Bradstreets endured many privations, but it was her faith that helped her endure — even as she struggled with some of its harsher tenets, like salvation and redemption.

In his sketch of Anne Bradstreet in Who Lived Here? (1952), M.A. De Wolfe wrote of what might have inspired her to pursue writing:

“What set Anne Bradstreet apart from most of the emigrating women was her exposure to books, the works of both earlier writers and of her own exciting contemporaries — and not only her exposure, but her response to it.

One thing to be remembered is that in the ruling class of the Bay Colony to which Anne Bradstreet belonged, the clergy held a powerful place, and that month the immigrants to New England even before 1640 there were about one hundred fifteen graduates of English University’s — chiefly ministers — and that seventy-four of these were in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Difficult, then, as the mere mechanics of living must have been for anybody of Anne Bradstreet’s tastes and gifts, she could feel that her voice … would find some sympathetic listeners not too far away.”

Wife, mother, and poet

Anne was always, from girlhood, in delicate health. Once safely settled in Massachusetts, she anxiously awaited the arrival of children.

The Son of Prayers, of vowes, of teares,

The childe I stay’d for many years.

She did manage to have eight children, and her love for them inspired her best-known lines (from “In Reference to Her Children, 23 June 1659)

I had eight birds hatch in one nest,

Four Cocks there were, and Hens the rest,

I nurst them up with pain and care,

Nor cost nor Labour dis I spare,

Till at the last they felt their wing,

Mounted the Trees and learn’d to sing.

The poem continues on for many lines, celebrating each of her offspring. You can read it in its entirety in this post.

Of her demanding life as a mother and her pull to express herself as a writer, The Poetry Foundation offers these insights:

“Although Bradstreet had eight children between the years 1633 and 1652, which meant that her domestic responsibilities were extremely demanding, she wrote poetry which expressed her commitment to the craft of writing. In addition, her work reflects the religious and emotional conflicts she experienced as a woman writer and as a Puritan.

Throughout her life, Bradstreet was concerned with the issues of sin and redemption, physical and emotional frailty, death and immortality. Much of her work indicates that she had a difficult time resolving the conflict she experienced between the pleasures of sensory and familial experience and the promises of heaven. As a Puritan she struggled to subdue her attachment to the world, but as a woman she sometimes felt more strongly connected to her husband, children, and community than to God.”

Anne Bradstreet page on Amazon

A deeply ambitious writer

Anne Bradstreet was a deeply ambitious writer, according to this piece, Humble Assertions, published in Common-Place, the journal of early American life. In it, Charlotte Gordon writes that her sophistication as a poet is often overlooked, as well as:

“…her skills as a disguise artist, and her youthful ambition. But if one reads Bradstreet’s poetry with close attention, one finds work that is replete with double meanings and ironies, self-deprecation and even self-condemnation—strategies she had learned in a culture that disparaged women for trespassing in realms that were considered male territory.”

The first edition of the poetry collection that won her fame was The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America (1650). How it came to be published was through the graces of her brother-in-law, John Woodbridge (a minister), husband of her sister Mercy Dudley. According to common legend, took Anne’s manuscript volume of poetry with him to England, and had it printed in London without her knowledge.

Published under the pseudonym “A Gentlewoman from Those Parts,” this collection, like Anne Bradstreet’s subsequent work, reflected the duties of a Puritan woman to God, home, and family.

She did so with skill, yet occasionally allowed some cynical notes to creep in — exercizing the only form of rebellion available to her. She pushed back against the criticism heaped against her in her poems, as in this stanza from the poem “Prologue”:

I am obnoxious to each carping tongue

That says my hand a needle better fits.

A poet’s pen all scorn I should thus wrong.

For such despite they cast on female wits:

If what I do prove well, it won’t advance,

They’ll say it’s stol’n, or else it was by chance.

See also: 6 Early American Women Writers to Rediscover

A woman’s universal joys and struggles

Though Anne wrote sincerely and lovingly about her family, she also expressed her struggles as a woman and as a mother in her poetry.

Though she refused to accept the notion of women’s inferiority, she did seem to find contentment in her lot. Her husband was apparently supportive of her literary aspirations and was the beneficiary of her regard in “To My Dear and Loving Husband” which begins:

If ever two were one, then surely we.

If ever man were lov’d by wife, then thee;

If ever wife was happy in a man,

Compare with me ye women if you can.

Read the rest of this poem and others by Anne Bradstreet here. Several of her best-known poems can be read at Wikisource.

Legacy

Being from a wealthy family and having received a good, if informal education was to Anne’s advantage in an era when many Colonial women weren’t even taught to read, let alone write. She produced a copious body of poetry in the face of a great deal of criticism, but refused to accept the notion of women’s inferiority.

Summing up, M.A. DeWolfe Howe wrote: “Anne Bradstreet was not the first, or last, of poets needing to be stripped of excess poetical baggage. In fact. she had a good deal of it, but there is a residue which, quite apart from the unique circumstances of its origin, should not be permitted to perish. It was long before any other woman took such a place as her among the poets of America.”

Anne Bradstreet died at the age of 60 in 1672 in North Andover, Massachusetts.

More about Anne Bradstreet on this site

5 Poems by Anne Bradstreet, Colonial American Poet

More information

Anne Bradstreet: Celebrating 400 Years and Beyond

Wikipedia

Poetry Foundation

The Tenth Muse, Lately Sprung Up in America

Humble Assertions: The True Story of Anne Bradstreet’s Publication of The Tenth Muse

Anne Bradstreet Poems

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Anne Bradstreet appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 30, 2018

7 Biographies of Laura Ingalls Wilder, Author of the Little House Books

Laura Ingalls Wilder (1867 – 1957) has a permanent place in the American imagination for her beloved Little House series of books for young readers. With her own humble beginnings, having been born in a log cabin on the edge of an area called “Big Woods” in Pepin, Wisconsin, her life inspired her semi-autobiographical novels.

Because her fames series of books came out when she was already sixty-five, Laura’s body of work mainly consisted of the 9-volume little house set. The first installment, Little House in the Big Woods, was published in 1931; the best known of the series, Little House on the Prairie, was published soon after and the rest of the series followed apace.

Though the family depicted in the stories was idealized, the hardships and joys of pioneering the Great Plains in the mid-1800s was based on Laura’s actual experiences. Her tales immediately appealed to readers of all ages, immediately popular with readers and well-received by critics. Perhaps their being publication during the Great Depression resonated with a message of resilience during hard times.

The Little House books continues to be read from one generation to another, and her life continues to be a source of fascination. Here are several biographies of Laura Ingalls Wilder (including autobiographies) for those who can’t get enough of America’s favorite “pioneer girl.”

Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Biography (2007)

This substantive 2007 biography by William Anderson is aimed at middle grade readers. From her days on the prairie to her long and happy marriage to Almanzo Wilder, this well-researched account illuminates the real-life events behind the Little House books. Readers will also get a glimpse of what her life was like after the last Little House book left off.

Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Biography on Amazon

Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Writer’s Life (2007)

From Amazon: “In Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Writer’s Life, Pamela Smith Hill delves into the complex and often fascinating relationships Wilder formed throughout her life that led to the writing of her classic Little House series.

Using Wilder’s stories, personal correspondence, a previously unpublished autobiography, and experiences in South Dakota, Hill has produced a historical-literary biography of the famous and much-loved author. Following the course of Wilder’s life, and her real family’s journey west, Hill provides a context both familial and literary, for Wilder’s writing career.”

Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Writer’s Life on Amazon

On the Way Home (1962)