Nava Atlas's Blog, page 71

March 24, 2019

Dorothy Thompson, Trailblazing Correspondent & Broadcaster

Dorothy Thompson (1893 – 1961) used her charm, wit, sense of adventure, and strong work ethic to create an incredibly illustrious career in journalism. Born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, she studied politics and economics at Syracuse University.

After completing her degree in 1914, a rarity for a woman in her time, she felt an obligation to contribute to the public good. Her cause of choice was the women’s women’s suffrage movement. After women won the right to vote in 1920, she moved to Europe to pursue journalism and became one of America’s first foreign correspondents.

In her heyday, she reported from across the European continent and at the same time enjoyed a fabulous social life. Her circle of friends included many writers and artists as well as some of the most notable journalists in the field.

A trusted American journalist

By the time she had returned to the U.S. in the1930s Dorothy was one of the most trusted American journalists. Her “On the Record” column in the New York Tribune was syndicated, with more than ten million readers. She also wrote a column, from 1937 to 1961, for the enormously popular magazine Ladies’ Home Journal. Though in that forum she steered clear of political topics in favor of domestic ones, it serve to gain her an even larger and devoted readership.

Dorothy’s heart was in the international political arena. Never sugar-coating the truth, she sounded the alarm against the rise of fascism, and for that she was thrown out of Germany in 1933 as Hitler and the Third Reich were rising.

As a news commentator for NBC radio in the 1930s, Dorothy’s show, “On the Record” was heard by millions. When Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939, legend has it that Dorothy stayed on the air for fifteen days and nights in a row (it’s not clear what she did about sleep!). The June 12, 1939 issue of Time magazine featured her on the cover, speaking into an NBC radio microphone.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A trailblazer whose life inspired a film and a musical

Dorothy Thompson’s life and work inspired the 1942 film Woman of the Year. Katherine Hepburn plays Tess Harding, a character based on Dorothy. It also became a Broadway musical, with Lauren Bacall as Tess.

Thompson was considered the most influential American woman, second only to first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. With all she accomplished, and being immortalized in a movie and a musical, isn’t it amazing that few people today have heard of her?

Here’s more on this legendary journalist from the 1973 edition of Dorothy Thompson: A Legend in Her Time by Marion K. Sanders (Houghton Mifflin Co.):

An extraordinary woman in a tumultuous time

Dorothy Thompson was an extraordinary woman in an extraordinary time. Her marriage to Sinclair Lewis was the most celebrated literary union of the century, but it was in her own right that she became “the First Lady of American Journalism.”

She was a highly talented reporter who covered the tumultuous happenings of the era preceding and during World War II; more importantly, she played a prominent role in helping to shape her countrymen’s attitudes toward the crucial events of those times.

. . . . . . . . . .

Sinclair Lewis and Dorothy Thompson in 1928

. . . . . . . . . .

Going wherever history was being made

This is the first full story of what Dorothy herself called her “love affair with life.” It spans a long and controversial professional career and a stormy private one that included three marriages and a succession of attachments to both sexes. It is a far journey that begins in a poor parsonage in western New York State and goes forth to range through the capitals of the western world.

Beginning in the 1920s, Dorothy managed to be in the right place at the right time — wherever history was being made. “She swept though Europe like a blue-eyed tornado, said her colleague John Gunther. In Vienna and Berlin, Moscow, Budapest, and London, she was the center of a brilliant, glamorous group of foreign correspondents.

By 1934, when she was expelled from Germany by Hitler’s personal order, she had become an international celebrity. She returned to America as a columnist and commentator whose political opinions and eloquent warnings on the rise of the Third Reich were read and heard and heeded by millions.

“She and Eleanor Roosevelt are undoubtedly the most influential women in the U.S.,” stated a magazine cover story featuring Dorothy Thompson.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Has “The First Lady of American Journalism” been forgotten?

Dorothy’s friends and personal brain trust of the succeeding years formed a roster of distinguished Americans and refugee European intellectuals, and her farm in Vermont, along with various elegant homes in New York, became the social axis of her influential court. Her powerful public presence, however, masked an emotional vulnerability that sometimes led her to contradictory passions and allegiances.

Marion K. Sanders’ candid and compassionate biography, based on Dorothy Thompson’s journals and personal papers and on extensive interviews with friends and associates on two continents, brings a tremendous immediacy to her life story and the several worlds she moved in. One has the sense sharing the excitements and heartbreak of these crowded legendary years, of witnessing first hand the unfolding of a complex and always fascinating woman.

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes by Dorothy Thompson

“There is nothing to fear except the persistent refusal to find out the truth.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Peace is not the absence of conflict but the presence of creative alternatives for responding to conflict — alternatives to passive or aggressive responses, alternatives to violence.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Courage, it would seem, is nothing less than the power to overcome danger, misfortune, fear, injustice, while continuing to affirm inwardly that life with all its sorrows is good; that everything is meaningful even if in a sense beyond our understanding; and that there is always tomorrow.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Peace has to be created, in order to be maintained. It is the product of Faith, Strength, Energy, Will, Sympathy, Justice, Imagination, and the triumph of principle. It will never be achieved by passivity and quietism.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“When liberty is taken away by force, it can be restored by force. When it is relinquished by default it can never be recovered.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Only when we are no longer afraid do we begin to live.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The most destructive element in the human mind is fear.”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Dorothy Thompson

Wikipedia

Dorothy Thompson: The Real Woman of the Year

Americans and the Holocaust: Dorothy Thompson

… and read more about trailblazing women journalists on this site.

The post Dorothy Thompson, Trailblazing Correspondent & Broadcaster appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 22, 2019

Keeper: Emily Brontë’s Fiercely Devoted Dog

Though Emily Brontë (1818 – 1848) only lived to the age of thirty, she produced one of the most iconic novels in the English literary canon. Wuthering Heights is a decidedly dark study of romantic obsession that takes a rather dim view of human nature.

The sister of Charlotte and Anne Brontë, Emily was beyond introverted. She didn’t care for company outside of her immediate family, and any time she ventured from her beloved Yorkshire moors, she became sick with longing to return. Emily Brontë’s dog Keeper, a large and rather menacing dog, was among the most faithful companions of her adult life.

There were other dogs and cats in residence at the Parsonage over the years, including Cavalier King Charles Spaniel named Flossy who belonged to Anne. Like her mistress, Flossy could be both gentle and strong willed. She was as solely devoted to Anne as Keeper was to Emily.

The mutual devotion between Emily Brontë and her dog was surprising, given the brutal way in which Emily asserted her role as the “alpha” of the two. This part of the story isn’t pretty, and hints at a violent nature that may have been part of Emily’s psyche. Given her sheltered upbringing and limited contact with the outside world, this hidden part of herself allowed her to create a character like Heathcliff. But once dog and mistress settled on who was in charge, it became a story of a dog’s undying loyalty for his mistress, and hers for him.

. . . . . . . . . .

Sketch of Keeper by Emily Brontë (later colorized from the original)

. . . . . . . . . .

First, we’ll hear the story as told by by Albert Payson Terhune as it appeared in The Baltimore Sun, January 9, 1927. Though the Brontë had been long gone, there was still, at the time, an incredible amount of fascination with them on both sides of the pond:

Three strange literary geniuses

Up in the bleakest corner of the Yorkshire moors, the little village of Haworth clings to its bare hillside. It is like a hundred other desolate hamlets in the same region; except that once it was the dwelling place of the Brontë sisters, three strange literary geniuses whose fame became worldwide.

They were the daughters of the local clergyman, Patrick Brontë, whose life was soured by the drunkenness and early each of his only son, Branwell. I spent a few days at Haworth and visited the parsonage long after the last of the Brontës died. That visit made me understand the gloom of the three Brontë girls’ lives.

Charlotte Brontë is best remembered for her novel, Jane Eyre. Emily wrote one grippingly powerful book, Wuthering Heights. Anne was the gentlest of the trio, yet had a fortitude of her own. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is her masterwork. Emily was the most unapproachable of the trio.

Affection for a dog with “the nature of a brute”

The bulk of Emily’s affection was lavished on a gigantic dog, half mastiff, half bulldog. His name was Keeper and in at least one of the Brontë books his character is drawn with wondrous skill. The man who gave Keeper to Emily also gave him a doubtful reputation by writing to her the following account of the big dog:

“Though he is faithful to the depths of his nature as long as he is with friends, yet who strikes him rouses the relentless nature of the brute who flies at such man’s throat, therewith, and holds him there until one or the other is at the point of death.

Emily knew little about dogs, and such a warning as came with Keeper would have scared a less courageous woman that she. But she welcomed Keeper and set about to win his love and confidence.

It was a hard job, but less hard perhaps if both dog and mistress had not been of the same stubborn nature. Presently a strong friendship grew between them. Keeper became Emily’s shadow, following her everywhere.

But the presence of the great dog in the primly quiet parsonage was not an unmixed pleasure to anyone. He did whatever he chose to, and none dared punish him for fear of a murderous attack.

For instance, he would pick out the cleanest and most comfortable bed in the house and would go to sleep on it, refusing to move when ordered to. A growl would accompany his refusal, and with it, a savage show of teeth.

. . . . . . . . . .

Illustration of Emily and Keeper from the 1920s

. . . . . . . . . .

Showing Keeper who was in charge

Emily did not chance to discover him lying thus on her bed until the rest of the household had complained often and bitterly. But when one day she did discover him stretched out on her counterpane with his muddy paws smearing it she went into immediate action.

She ordered Keeper to get down from the bed. As usual he merely snarled and showed his teeth. Emily rushed at him and seized him by the neck, dragging him off the bed and out of the room and down the stairs. As no whip was handy she beat him furiously about the head with her bare fists until his eyes were swollen and his nose bleeding.

So sudden and so ferocious was her assault on him, and so fearless was it, that Keeper did not so much as try to defend himself from the beating. He stood snarling and growling, but making no move to attack his assailant while the stinging rain of frantic fist-blows landed on his shaggy head and face.

When the beating was over it was Emily herself who bathed and sponged his swollen face. From that hour Emily and Keeper were perfect chums.

She even undertook to teach him a single trick. The trick consisted of roaring furiously at at man who called at the parsonage and leaping at the guest’s throat. The roar and the leap were merely playful, though they did not give that impression.

Emily said she used to judge men by the way they behaved under such nerve-shaking treatment. He who shrank from the dog’s noisy assault was deemed by her a coward and unworthy of future notice.

The Yorkshire Moorland around Haworth was lonely and frequented sometimes by doubtful characters. But Emily used to walk over it for miles with Keeper at her side. She was as safe with such an escort as if she had been guarded by a troop of cavalry.

Loyalty to Emily beyond the grave

When Emily Brontë died, Keeper insisted on crouching close beside her coffin until the hour of burial. Then, as chief mourner, he followed it to the grave in the nearby churchyard. With great difficulty he was induced to leave the filled-in grave and follow the mourners back to the parsonage.

There, heavily, he made his way to the door of the room that had been Emily’s. The door was shut. Keeper lay down on the threshold, lifted his head, and shook the silent house with a series of unearthly howls. Nor for weeks thereafter would he move from that closed door of his own accord. To the time of his death, he slept there every night.

Charlotte was the last survivor of the Brontë siblings. She did what she could for Keeper’s happiness, but he never accepted her mastery nor ceased to grieve for Emily. You will find a character sketch of him in Charlotte’s novel, Shirley, where he appears under the name of Tartar.

Gradually, steadily, the old dog pined away. Charlotte tells of his end in a letter which is published in her biography. She wrote: “Keeper died last Monday. After being ill all night he gently went to sleep. We laid his old faithful head in the garden.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Brontë sisters, in a painting by their brother, Branwell.

She wrote much about their paths to publication

. . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Gaskell’s view of Keeper

From The Life of Charlotte Brontë by Elizabeth Gaskell (1857): The same tawny bull-dog (with his “strangled whistle”), called “Tartar” in Shirley, was “Keeper” in Haworth parsonage; a gift to Emily. With the gift came a warning. Keeper was faithful to the depths of his nature as long as he was with friends; but he who struck him with a stick or whip, roused the relentless nature of the brute, who flew at his throat forthwith, and held him there till one or the other was at the point of death.

Now Keeper’s household fault was this. He loved to steal upstairs, and stretch his square, tawny limbs, on the comfortable beds, covered over with delicate white counterpanes. But the cleanliness of the parsonage arrangements was perfect; and this habit of Keeper’s was so objectionable, that Emily, in reply to Tabby’s remonstrances, declared that, if he was found again transgressing, she herself, in defiance of warning and his well-known ferocity of nature, would beat him so severely that he would never offend again.

In the gathering dusk of an autumn evening, Tabby came, half-triumphantly, half-tremblingly, but in great wrath, to tell Emily that Keeper was lying on the best bed, in drowsy voluptuousness. Charlotte saw Emily’s whitening face, and set mouth, but dared not speak to interfere; no one dared when Emily’s eyes glowed in that manner out of the paleness of her face, and when her lips were so compressed into stone.

She went upstairs, and Tabby and Charlotte stood in the gloomy passage below, full of the dark shadows of coming night. Down-stairs came Emily, dragging after her the unwilling Keeper, his hind legs set in a heavy attitude of resistance, held by the “scuft of his neck,” but growling low and savagely all the time.

The watchers would fain have spoken, but durst not, for fear of taking off Emily’s attention, and causing her to avert her head for a moment from the enraged brute.

She let him go, planted in a dark corner at the bottom of the stairs; no time was there to fetch stick or rod, for fear of the strangling clutch at her throat—her bare clenched fist struck against his red fierce eyes, before he had time to make his spring, and, in the language of the turf, she “punished him” till his eyes were swelled up, and the half-blind, stupified beast was led to his accustomed lair, to have his swollen head fomented and cared for by the very Emily herself.

And upon Emily’s death:

… her old father, Charlotte, the dying Anne; and as they left the doors, they were joined by another mourner, Keeper, Emily’s dog. He walked in front of all, first in the rank of mourners; and perhaps no other creature had known the dead woman quite so well.

When they had lain her to sleep in the dark, airless vault under the church, and when they had crossed the bleak churchyard, and had entered the empty house again, Keeper went straight to the door of the room where his mistress used to sleep, and lay down across the threshold. There he howled piteously for many days; knowing not that no lamentations could wake her any more.

The generous dog owed her no grudge; he loved her dearly ever after; he walked first among the mourners to her funeral; he slept moaning for nights at the door of her empty room, and never, so to speak, rejoiced, dog fashion, after her death. He, in his turn, was mourned over by the surviving sister.

The post Keeper: Emily Brontë’s Fiercely Devoted Dog appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 21, 2019

Duty and Desire: Quotes from The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

The Age of Innocence (1920) by Edith Wharton (1862 – 1937) is considered one of this classic American author’s finest works. In 1921, it earned Wharton the distinction as the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

The story is set in the 1870s and centers on Newland Archer, an upper-class New Yorker. Archer’s conflicted desires between duty to his staid but loving wife and his passion for scandal-plagued divorcée Countess Ellen Olenska are central to the narrative. The overarching conflict explored by the novel is the extent to which an individual should allow the rules of society to overrule what the heart desires.

A reflection of Wharton’s privileged world

The story’s setting reflects the world of wealth and privilege in which Edith Wharton grew up. Despite all the advantages that she shared with her fictional characters, neither she nor they were spared from heartache and love affairs gone wrong. An original 1920 review expressed the nearly universal praise for this novel:

“With deft and certain touch Mrs. Wharton builds her sort around the society of the day, showing the absolutely artificial lives led by its members, their abject submission to rules and restriction prescribed by convention, and their distrust of, and hostility to, such of their people as evinced any desire for freedom of thought or action.”

Much of the novel delves into Archer’s innermost thoughts and his conflicting feelings about duty to marital vows and the desires of the heart. Here is a selection of quotes from The Age of Innocence that capture its essence.

. . . . . . . . . .

“With a shiver of foreboding he saw his marriage becoming what most of the other marriages about him were: a dull association of material and social interests held together by ignorance on the one side and hypocrisy on the other.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He took refuge in the comforting platitude that the first six months were always the most difficult in marriage. ‘After that I suppose we shall have pretty nearly finished rubbing off each other’s angles,’ he reflected; but the worst of it was that May’s pressure was already bearing on the very angles whose sharpness he most wanted to keep.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The real loneliness is living among all these kind people who only ask one to pretend!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He had married (as most young men did) because he had met a perfectly charming girl at the moment when a series of rather aimless sentimental adventures were ending in premature disgust; and she had represented peace, stability, comradeship, and the steadying sense of an unescapable duty.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton: A 1920 Review

. . . . . . . . . .

“I swear I only want to hear about you, to know what you’ve been doing. It’s a hundred years since we’ve met-it may be another hundred before we meet again.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“We can’t behave like people in novels, though, can we?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Once more it was borne in on him that marriage was not the safe anchorage he had been taught to think, but a voyage on uncharted seas.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The worst of doing one’s duty was that it apparently unfitted one for doing anything else.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The persons of their world lived in an atmosphere of faint implications and pale delicacies, and the fact that he and she understood each other without a word seemed to the young man to bring them nearer than any explanation would have done.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The young man felt that his fate was sealed: for the rest of his life he would go up every evening between the cast-iron railings of that greenish-yellow doorstep, and pass through a Pompeian vestibule into a hall with a wainscoting of varnished yellow wood. But beyond that his imagination could not travel.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To the general relief, the Countess Olenska was not present in her grandmother’s drawing-room . . . it spared them the embarrassment of her presence, and the faint shadow that her unhappy past might seem to shed on their radiant future.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Ah, good conversation – there’s nothing like it, is there? The air of ideas is the only air worth breathing.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“In reality they all lived in a kind of hieroglyphic world, where the real thing was never said or done or even thought, but only represented by a set of arbitrary signs.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“His whole future seemed suddenly to be unrolled before him; and passing down its endless emptiness he saw the dwindling figure of a man to whom nothing was ever to happen.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“But after a moment a sense of waste and ruin overcame him. There they were, close together and safe and shut in; yet so chained to their separate destinies that they might as well been half the world apart.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Women ought to be free — as free as we are,’ he declared, making a discovery of which he was too irritated to measure the terrific consequences.”

. . . . . . . . . .

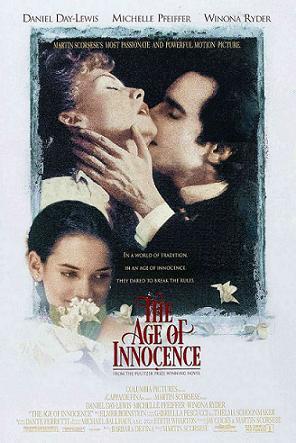

Too busy to read the book? Look for the wonderful 1993 film version of The Age of Innocence

starring Daniel Day-Lewis, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Winona Ryder

. . . . . . . . . .

“His own exclamation: ‘Women should be free—as free as we are,’ struck to the root of a problem that it was agreed in his world to regard as nonexistent. ‘Nice’ women, however wronged, would never claim the kind of freedom he meant, and generous-minded men like himself were therefore—in the heat of argument—the more chivalrously ready to concede it to them. Such verbal generosities were in fact only a humbugging disguise of the inexorable conventions that tied things together and bound people down to the old pattern.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He had known the love that is fed on caresses and feeds them; but this passion that was closer than his bones was not to be superficially satisfied.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He had built up within himself a kind of sanctuary in which she throned among his secret thoughts and longings. Little by little it became the scene of his real life, of his only rational activities; thither he brought the books he read, the ideas and feelings which nourished him, his judgments and his visions. Outside it, in the scene of his actual life, he moved with a growing sense of unreality and insufficiency, blundering against familiar prejudices and traditional points of view as an absent-minded man goes on bumping into the furniture of his own room.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I shan’t be lonely now. I was lonely; I was afraid. But the emptiness and the darkness are gone; when I turn back into myself now I’m like a child going at night into a room where there’s always a light.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“And you’ll sit beside me, and we’ll look, not at visions, but at realities.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He simply felt that if he could carry away the vision of the spot of earth she walked on, and the way the sky and sea enclosed it, the rest of the world might seem less empty.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He had her in his arms, her face like a wet flower at his lips, and all their vain terrors shriveling up like ghosts at sunrise.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Age of Innocence on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“A smiling, bantering, humoring, watchful and incessant lie. A lie by day, a lie by night, a lie in every touch and every look; a lie in every caress and every quarrel; a lie in every word and in every silence.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“When we’ve been apart, and I’m looking forward to seeing you, every thought is burnt up in a great flame. But then you come; and you’re so much more than I remembered, and what I want of you is so much more than an hour or two every now and then, with wastes of thirsty waiting between, that I can sit perfectly still beside you, like this, with that other vision in my mind, just quietly trusting it to come true.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There was no use in trying to emancipate a wife who had not the dimmest notion that she was not free.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“What’s the use? You gave me my first glimpse of a real life, and at the same moment you asked me to go on with a sham one. It’s beyond human enduring—that’s all.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Something he knew he had missed: the flower of life. But he thought of it now as a thing so unattainable and improbable that to have repined would have been like despairing because one had not drawn the first prize in a lottery.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The longing was with him day and night, an incessant undefinable craving, like the sudden whim of a sick man for food and drink once tasted and long since forgotten. . . He simply felt that if he could carry away the vision of the spot of earth she walked on, and the way the sky and sea enclosed it, the rest of the world might seem less empty.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“During that time he had been living with his youthful memory of her; but she had doubtless had other and more tangible companionship. Perhaps too had kept her memory of him as something apart; but if she had, it must have been like a relic in a small dim chapel, where there was not time to pray every day … “

. . . . . . . . . .

“Their long years together had shown him that it did not so much matter if marriage was a dull duty, as long as it kept the dignity of a duty: lapsing from that, it became a mere battle of ugly appetites. Looking about him, he honored his own past, and mourned for it. After all, there was good in the old ways.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Duty and Desire: Quotes from The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 20, 2019

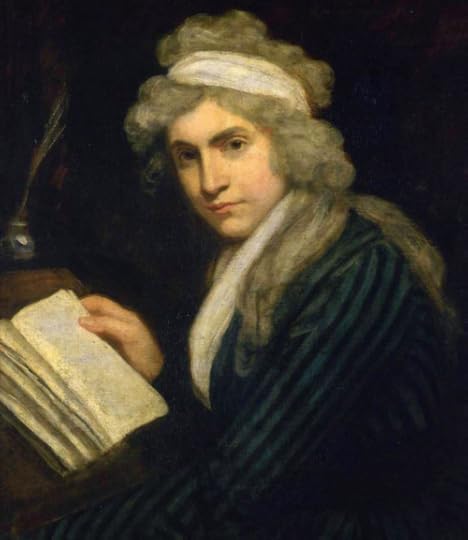

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (April 27, 1759 – September 10, 1797) was a British author of fiction and nonfiction, philosopher, and women’s rights advocate. Though her body of work was fairly substantial, including many essays, a history of the French Revolution, and some fiction, she’s now almost exclusively known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. She was the mother of Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (later known as Mary Shelley), the author of Frankenstein; sadly, she died a few days after giving birth to her namesake.

Born in the Spitalfields section of London, her father, Edward John Wollstonecraft, frittered away his inherited fortune. He bullied his children and beat his wife, Elizabeth Dixon, during drunken rages. While in her teens, Mary sat guard at her mother’s door to try to protect her from her father.

An unstable childhood and youth

There were six siblings in the household. The eldest, Edward, eventually became an attorney who practiced in London. There were two other brothers, and three sisters, Mary, Everina, and Eliza. Their father continued to make life intolerable for his family as his fortunes deteriorated with each failed venture.

Of the Wollstonecraft children, Mary and Eliza were thought to be quite talented, but they acquired little in terms of formal education. When their mother died in 1780, Mary, at age 21, resolved with her sister to become a teacher.

Finding her father’s household intolerable, she moved in with her friend Fanny Blood, only to find that her friend’s father was just as nefarious as her own. She derived some comfort in assisting Fanny’s mother in doing needlework as a trade, but not many years later, lost her dear friend when she died in childbirth

Her sister Everina went to work keeping house for their brother Edward. Eliza accepted an offer of marriage while still quite young as a way to escape her miserable home life. Marriage was no salve, as her husband, a Mr. Bishop, was abusive.

Eliza’s misfortune was portrayed later in Mary’s thinly veiled novel fragment, The Wrongs of Woman, or Maria. Things got so bad that Eliza went into hiding until she could obtain a legal separation. In 1783, Mary and Everina started a school at Newington Green, though it lasted only two years.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Beginning a literary career

After this short stint as a teacher, Mary worked as a lady’s companion and governess, and quickly realized that she was ill-suited for these traditional female occupations. She was frustrated at the lack of options for women to make a living and wrote of this quandary in one of her first published works, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters.

Mary was determined to do what she most wanted — to become a writer. There were few women who were able to support themselves by their pen, so her ambition was nothing less than radical. But as she wrote to Everina, she wished to become “the first of a new genus.”

Mary settled in London and found a position with the progressive publisher Joseph Johnson as a reader and translator. The occupation not only suited her well, but had other benefits. It gave her the opportunity to connect with the literary circles of the day, and with her earnings, she helped her siblings, especially Everina.

In 1792, Mary published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects. It enjoyed some initial success and was translated into French. Its central thesis was an argument for equality of men and women: Men and women, in her view, are born with the ability to reason, and therefore power and influence should be equally available to all regardless of gender. This was quite a unique and radical view for its time.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is considered one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. In her preface to Mary Wollstonecraft: A Biography (1972), women’s studies pioneer Eleanor Flexner wrote that her subject “articulated her protest and her ideas of what education and equality of opportunity might do for society as a whole … It is not given to many books to exert as powerful an influence as A Vindication has done, although its effect was delayed and for decades it was largely unread.” Read more of this appreciation of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

. . . . . . . . .

Quotes from A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft

. . . . . . . . .

Gilbert Imlay: Obsessive love

Later in 1792, traveling to Paris alone, Mary met and fell in love with Gilbert Imlay, a commercial speculator, adventurer, and former American army captain during the Revolutionary War.

Getting married in France would have been virtually impossible during the Reign of Terror. King Louis XVI had recently been guillotined, and Britain and France were on the brink of war. So Mary lived openly with Imlay without marrying. Marriage was unimportant to her, as evidenced in her Letters to Imlay (a posthumously published collection); still, to live with a man as his wife without being married was shocking. And of course, it was the woman who suffered all the societal consequences.

By the end of 1793, the two were living in Havre, France, and on May 14, 1794, Mary gave birth to a daughter, who they named Fanny. Mary continued to write, publishing Historical View of the French Revolution not long after her daughter’s birth. Imlay was deeply involved in business speculations, which necessitated long periods of separation. Mary’s letters from this time hint at doubts about his feelings for her and suspicions of his infidelity. She recognized the perils of being so attached to a man whose feelings have grown cool:

“I have gotten into a melancholy mood, you perceive. You know my opinion of men in general; you know that I think them systematic tyrants, and that it is the rarest thing in the world to meet with a man with sufficient delicacy of feeling to govern desire. When I am thus sad, I lament that my little darling, fondly as I dote on her, is a girl. I am sorry to have a tie to a world that for me is ever sown with thorns.”

Mary’s suspicions proved correct. Imlay’s letters grew less frequent and less ardent as he embarked on a new love affair. Mary tried to kill herself with laudanum, but recovered.

The story of this tortured, increasingly one-sided affair continued for some time. When their final separation came, Mary, still passionately in love with Imlay, tried to drown herself by plunging off a bridge, but was rescued by a boat that was passing by. Even after that, she made several pathetic attempts to reconcile.

Eventually, Mary came to her senses and broke off with Imlay in 1796, refusing to take any financial support from him other than a bond that would benefit their daughter. She continued to write as a means of support as well as a way to return to London’s literary society.

. . . . . . . . .

Mary Wollstonecraft page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . .

A brief marriage and a fatal birth

She resumed her friendship with William Godwin, who she had met a few years earlier upon beginning to work for Joseph Johnson. Their relationship soon turned romantic. Though both of them were philosophically opposed to traditional marriage, they wed on March 29, 1797. Mary was by then expecting a child.

It was to be a brief marriage. After giving birth to a healthy baby girl, Mary contracted an infection and died eleven days later, on September 10, 1797. She was buried in the Old St. Pancras churchyard and in 1851, her remains were moved to Bournemouth.

Legacy

Mary Wollstonecraft was described as impulsive and enthusiastic, with charm of manner and brilliance of mind. A year after her death, Godwin published the simply titled Memoir. Though it wasn’t his intent to besmirch her reputation, he revealed intimate details of his late wife’s life. The book detailed her love affairs, illegitimate daughter Fanny, and suicide attempts, and more. All of it was deemed deeply immoral and appalled late-18th-century society, even the more progressive literati. In the preface, Godwin wrote:

“I cannot easily prevail on myself to doubt, that the more fully we are presented with the picture and story of such persons as the subject of the following narrative, the more generally shall we feel in ourselves an attachment to their fate and a sympathy in their excellencies. There are not many individuals with whose character the public welfare and improvement are more intimately connected than the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.”

Despite Godwin’s intentions of cementing her legacy, the book instead completely destroyed Mary Wollstonecraft’s reputation for the better part of a century. Female novelists of the 19th century, ironically, were the most vicious. They created unlikeable, amoral female characters and didn’t hide the fact that they were modeled from what they knew of Mary.

Fortunately, Mary Wollstonecraft’s legacy as a pioneering feminist philosopher was restored during the second-wave feminist movement of the 1970s, and she is often credited as an important influence on modern-day feminist theory.

More about Mary Wollstonecraft on this site

Quotes from A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: An Appreciation

Major works

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787)

Mary: A Fiction (1788)

Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790)

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution (1794)

Letters Written in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark (1796)

Letters to Imlay (1879; posthumous)

The Wrongs of Women, or Maria (novel fragment; posthumous, 1798)

More information

Wikipedia

Mary Wollstonecraft: Online Library of Liberty

BBC: Britain’s First Feminist

Read and listen

Mary Wollstonecraft’s works on Librivox

Public domain ebook of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Mary Wollstonecraft appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 18, 2019

A Book Lover’s Reykjavik — Bookstores, Libraries, and Book Culture

Prior to my first visit to Iceland in the summer of 2018, when I spent the entire month of August at a writer/artist residency, I knew very little about the country generally and even less about Reykjavik specifically. And prior to my trip, I’d been so busy that I had no time to do much research. I went with good word of mouth from friends who had visited and faith that it would be a good experience.

Of course, I had seen photos of the otherworldly landscapes, but I would have only the shortest time in which to explore them; my stay was mainly within the confines of Reykjavik. And that turned out to be absolutely beyond fine. In fact, for a nerd and bookworm like myself, it was blissful. Any time I had a chance, I would explore the myriad bookstores and libraries in Reykjavik, in addition to other aspects of its very rich book culture.

I’m hardly what you call the rugged outdoorsy type; I’m more of a books-and-art-and-coffee type. Iceland offers incredible pleasures for both of these kinds of travelers. If you happen to be a combination of the two, don’t even think about spending less than two weeks there.

It’s a small country, to be sure, but it is so dense with culture, history, and natural beauty that a short hop of a few days would be (at least for me) frustrating. Even after having spent a month there, I feel like I just scratched the surface, and am ever plotting a return.

Bókabúðin Bergstaðastræti

A few things I learned that came as a surprise to me:

Reykjavik is a UNESCO City of Literature, designated in 2011. There are some 28 as of this writing.

More books are published per capita in Iceland than any other country (though this is relative in a small country of about 350,000 citizens; but still …)

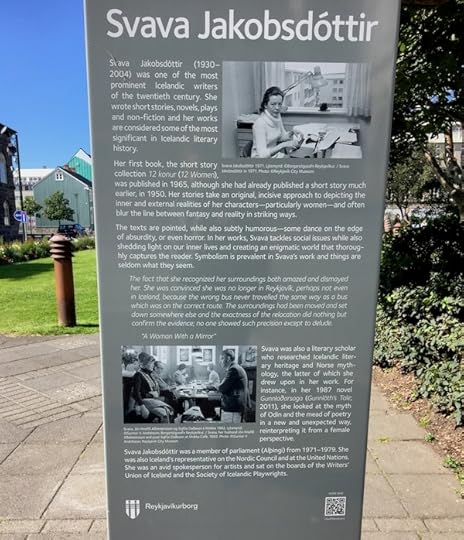

Reykjavik honors its literary figures with street signs, park benches, and more, that can be explored all around the town.

Icelanders have a custom called “a book on every bed” for Christmas. It’s just what it sounds like: on Christmas morning, a wrapped book is left as a gift on every bed.

Even though I didn’t get to every book-related site during my month in Reykjavik, I did get to plenty of them. This promises to be a lengthy post, so let’s get to it! Note that all the places on this list are centrally located and you can literally walk from one to another, as I did.

Reykjavik Bookstores

Bókabúðin Bergstaðastræti

A relatively small bookstore, but an exquisitely curated one, Bókabúðin Bergstaðastræti focuses on design, culture, and food. Truly, my kind of place. The one downside is that it’s one of the few bookstores without a café, but that shouldn’t preclude a visit. The selection is unique, and most of the books are English language. Bergstaðastræti 7, 101 Reykjavík.

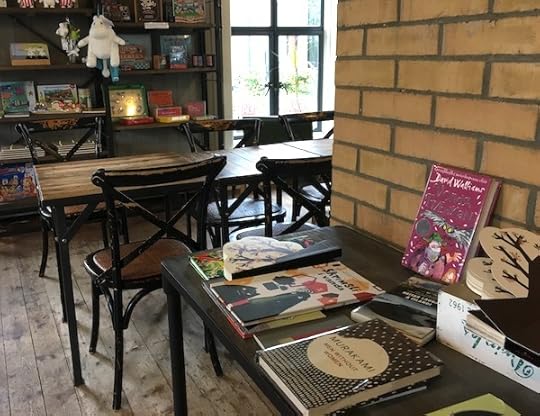

Ida Zimsen

This appealing bookstore-café-gift shop has such an unassuming exterior that even though it’s right in the center of the downtown area, I managed to ignore it until my last day in Reykjavik. About half the books are in Icelandic and half in English.

This place manages to be both expansive and cozy at the same time, including charming books and bookish gifts for children, and a nice table area to have coffee or work on one’s laptop (with coffee, of course). There’s also a menu of light fare and pastries. The photos above don’t nearly do credit to it, nor do many of the photos online. So I guess I’ll have to return, and take some better shots! Vesturgata 2a, Grófin, 101 Reykjavík.

Mal og Menning

Located in the center of Laugavegur, Reykjavik’s main shopping street, Mal og Menning won a place in my heart not only for their good selection of English language books but also for their café. It specializes in vegan soup-and-sourdough bread combos for a price that’s quite economical relative to other eateries (which, you may have heard, can be quite expensive).

For under $10, you can enjoy a big bowl of plant-based soup and the delicious sourdough bread that Iceland is famous for — a meal that will keep you full for hours. You can bring a book to browse through while you eat, and of course, you will carefully avoid getting any soup on it. You can read more about my vegan culinary adventures in Reykjavik on my other site, The Vegan Atlas. Above, an entire display dedicated to the Queen of Crime herself, Agatha Christie. Laugavegur 18, 101 Reykjavík.

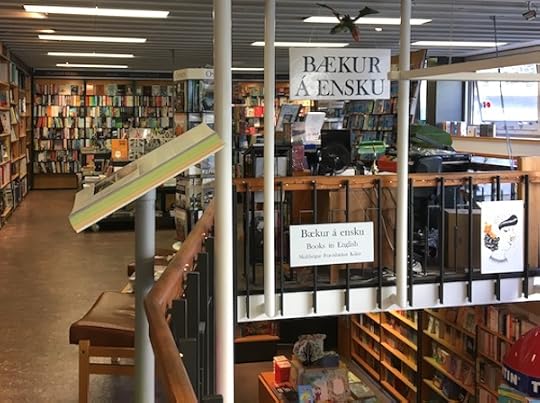

Penninn Eymundsson

Iceland’s largest bookstore chain (with 15 stores around the country), Penninn Eymundsson has three locations just blocks from one another in central Reykjavik. It’s also the oldest of the bookstores in the country, established in 1872. Though these bookstores may lack the visual charm of a smaller, cozier establishment, they make up for it with a great depth of offerings in both English and Icelandic.

What I found interesting is that many of the English language books seem to come from British publishers, so they were a bit different from what I see at home. There were also British editions of American bestsellers, so I got to see alternative covers and descriptions. I also loved seeing all the beautifully designed books — as well as the many books on design.

Within the stores are cafés run by the chain Te & Kaffi. Above, you’ll see that I treated myself to an oat milk latté, a vegan brownie, and The Life-Changing Magic of Not Giving a F**k. It was a nice day and not windy (somewhat of a rarity in Iceland), so I took my break on an outdoor terrace on one of the upper floors. The bottom two photos are from the Austurstræti 18 store and the top photo is from the Skólavörðustígur 11 location. There’s also a large branch at Laugavegur 77, and all are in Reykjavik 101.

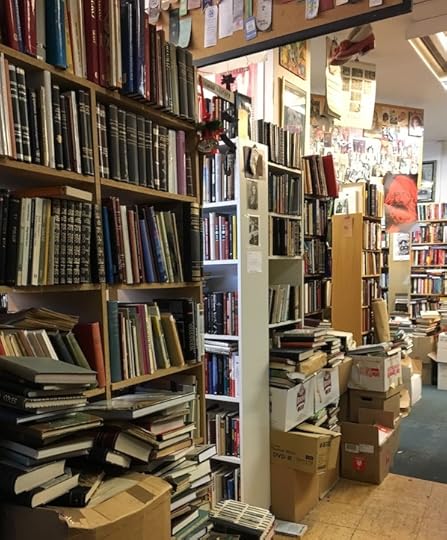

Bókin

This bookstore is almost the opposite of the others on this list — it deals mostly in used books, 95% of which are in Icelandic. Piles and piles of books are everywhere, some seeming to totter almost to the ceiling. So if your interest is in poring through older books in this fascinating and challenging language, this is the place for you. Klapparstígur 25-27, 101 Reykjavik.

Reykjavik Libraries

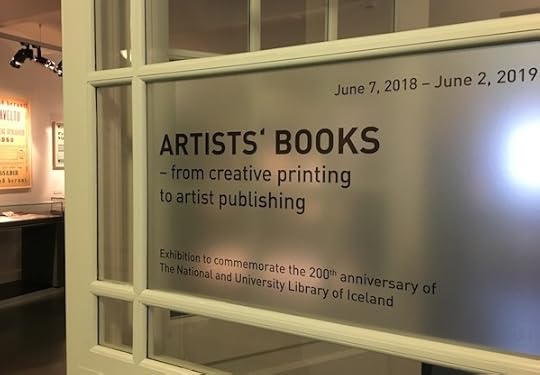

National and University Library of Iceland

This beautiful library, just off the campus of the University of Iceland in Reykjavik, is a repository of manuscripts, archives, historical documents, and of course, books. There are also beautifully mounted exhibits, mostly about Icelandic history and culture, throughout the building. As you can see, it’s a serene setting both inside and out, and for the book-loving traveler, this just-off-the-beaten-path site is well worth visiting. Arngrímsgötu 3, 107 Reykjavík.

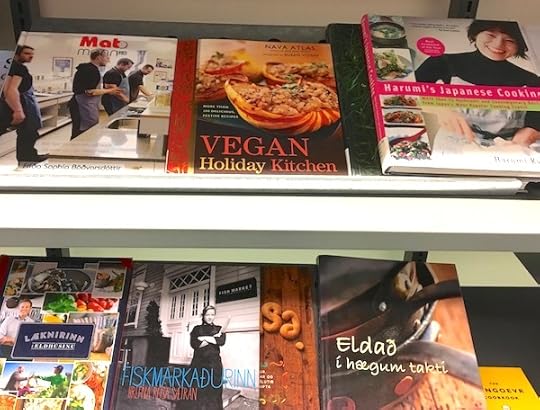

Reykjavik City Library

Reykjavik’s public library has six branches around the city, with the main branch located right in the heart of the downtown area. Visitors are welcome to browse, though you need a library card to be able to borrow books. The main branch is a has several floors, all flooded with natural light, with an array of books in Icelandic, English, and other languages. One quickly expanding area is their collection of global comic books.

The library hosts a variety of multicultural events throughout the year. Keep an eye out for the guided literary walks that beginning at the entrance during the warmer months, and make sure to visit the Reykjavik Museum of Photography on the top floor of the same building. It’s quite impressive!

Okay, I have to do a bit of a brag here. My friend and literary agent, Lisa Ekus, visited Reykjavik a few months before I did, and just happened to spot one of my books on display on the ground floor. When I went, it was still on display, but on one of the upper floors near where the cookbooks are shelved. That’s my book in the center, above — Vegan Holiday Kitchen. That was a pretty cool sight to see! Tryggvagata 15, 101 Reykjavík.

More Reykjavik book culture

Reykjavik City of Literature Self-Guided Walking Tour

All around the city, you’ll come across signage pertaining to Icelandic Literary Figures. The signs contain a QR code which allows visitors to partake in a self-guided tour right from their smartphones. Find out more about how to download the app here.

Art Library at Hafnarhús Art Museum

It seems like almost any cultural institution has at least a small library, or that books are an intrinsic part of exhibits (see below). Here’s a cozy library that’s part of one of the city’s contemporary art museums. It’s packed with art books, and you can while away an hour or so if you need to take a break from touring. The main branch of the Reykjavik City Library is just a few steps away, so combining a visit to these two sites (plus the Museum of Photography on the top floor of the library building) is a relaxing and intellectually stimulating itinerary for nerds. Tryggvagata 17, 101 Reykjavík.

Culture House

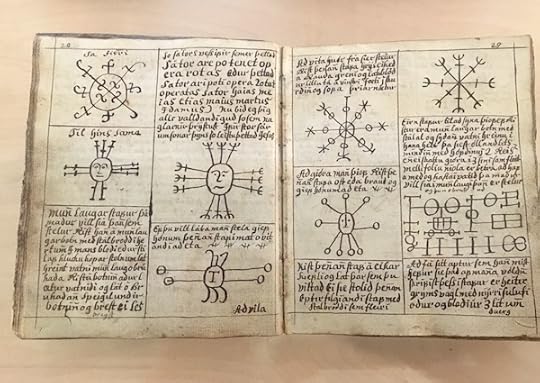

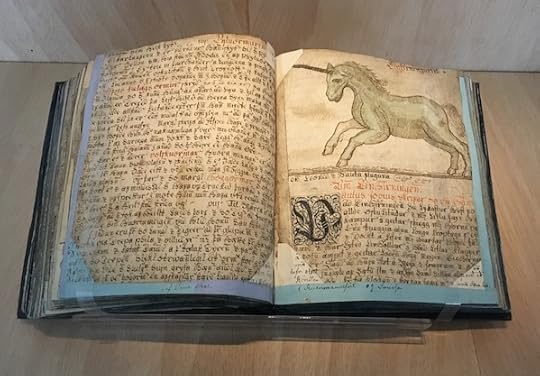

As mentioned just above, books are an intrinsic part of the country’s history and culture, with the Icelandic sagas dating back to the 9th century. So books are often a part of most any major exhibit, no matter what the theme. Culture House hosts a permanent exhibition called Points of View – a journey through the visual world of Iceland.

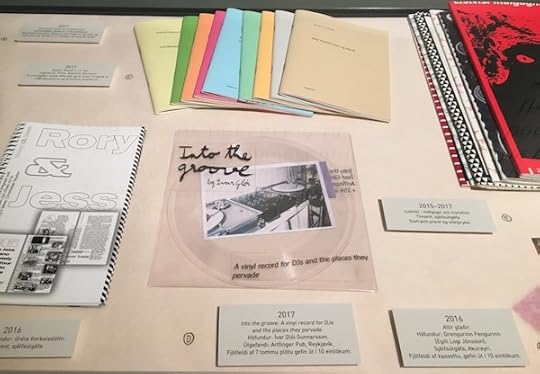

According to Culture House’s website: “The exhibition gives visitors a unique opportunity to view the collections of six major Icelandic cultural institutions. Artworks of various styles and mediums are presented thematically alongside museum objects and archival materials such as books and maps.” Above, a couple of absolutely beautiful medieval books spotted here, among many others, as well as an exhibition of contemporary artist’s books. Hverfisgata 15, 101 Reykjavík.

International Literary Festival

Every other spring, Reykjavik is home to the Reykjavik International Literary Festival. From the website: “Set in cozy venues in downtown Reykjavík every two years, the festival offers interesting and entertaining programs for literature enthusiasts. Over a span of more than 30 years, the festival has welcomed Nobel-prize winners, novelists, historians, political activists, philosophers, cartoonists and more to take part in lively programs. All programs are in English and there’s no admission fee to the events.” Meet me there?

Though this post is already mile long, I have a feeling I’ve hardly scratched the surface of Reykjavik’s bookstores, libraries, and book culture. For me, it’s a subject of endless fascination and a good reason to return to this enchanting place. Updates are on the horizon …

The post A Book Lover’s Reykjavik — Bookstores, Libraries, and Book Culture appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 16, 2019

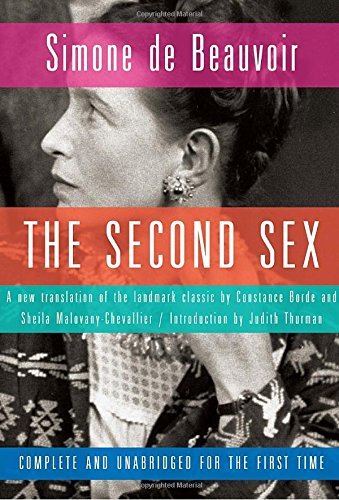

The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir (1949)

Simone de Beauvoir (1908 –1986) was a French author, existential philosopher, political activist, feminist, and social theorist whose most popular and enduring work is The Second Sex. Published in 1949, it was considered quite radical for its time and made de Beauvoir an intellectual force to be reckoned with. The book has inspired generations of women to question the status quo and strive to change it.

De Beauvoir, who wasn’t yet forty when her magnum opus was published, explored the history and mythology of the female gender. It was first published it in two volumes, Facts and Myths and Lived Experience (Les faits et les mythes & L’expérience vécue).

The Second Sex is a cornerstone works of feminist philosophy and the second wave feminist movement. It’s still read and studied to this day as an essential manifesto on women’s oppression and liberation. First published in the United States in 1953, it was a time when the media’s message to women was that their place was in the home. The English translation by H.M. Parshley was often criticized as subpar, even omitting swathes of text. A new translation came out in 2009, and though most critics found it to be better than the first, it, too, has had its detractors.

Despite some snarky reviews by male reviewers, the book was an immediate success in the American market, and was recognized as an instant classic. Here’s a review of The Second Sex from 1953, when the book first appeared in print in the United States.

An ever timely topic

From the March 1, 1953 review by Mary Lapsley of The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir in the Cincinnati Enquirer: It is with timidity that a reviewer who is also a woman approaches Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. If one lavishly praises it, one lends oneself to the suspicion that one does so merely through feminine complicity. If one condemns it, one lays oneself open to the charge of playing traitor to one’s sex. Yet it is perhaps through this very ambivalence — of choice, the existentialist would say — that one may arrive at a just appraisal.

When first published in France in 1949, Le Deuxieme Sexe appeared in two volumes: Facts and Myths and Lived Experiences. In Fact and Myths, Mlle. de Beauvoir states her reason for writing on a theme that has already had a large and almost always partisan literature.

“Books by women on women are in general animated in our day less by a wish to demand our rights than by an effort toward clarity and understanding. As we emerge from an era of excessive controversy, this book is offered as one attempt among others to confirm that statement.”

Indeed, the subject is timely. World War II required of women active participation in fields formerly closed to them. The UN Commission on the Status of Women maintains that the equality of sexes is now becoming a reality; that they must be regarded as equal is a necessary tenet in any Democratic challenge to totalitarianism.

. . . . . . . . . .

Philosophical Quotes by Simone de Beauvoir

. . . . . . . . . .

An existentialist perspective

Moreover, the importance of childhood environment on adults has of recent years been stressed to the point of exaggeration. The child is father to the man, and also, of necessity, the child is mother to the woman. Simone de Beauvoir is an existentialist, and it is in the terms of that philosophy that she views the history of her sex.

As an existentialist, Mlle. de Beauvoir finds that “the drama of woman lies in this conflict between the fundamental aspirations of every subject (ego) — who always regards the self as the essential — and the compulsions of a situation in which she is inessential.”

“Now what peculiarly signalizes the situation of the woman is that she — a free and autonomous being like all human creatures — nevertheless finds herself living in a world where men compel her to assume the status of the Other.” This masculine insistence that woman be the inessential, Mlle. de Beauvoir regards as the crying injustice; this she points out in 732 closely packed, reiterative pages.

“Men have presumed to create a feminine domain — the kingdom of life, of immanence — only in order to lock women therein.”

From the biological to the psychoanalytic

To this fate woman is condemned, says Mlle de Beauvoir, neither by facts of biology nor by immutable laws of her psychological makeup; her destiny is shaped by the society she lives in. As she acts in that society, according to existentialist belief, she makes herself; she chooses, by accepting a passive role, her subjugation to the male.

From biological facts, Mlle. de Beauvoir turns to the psychoanalytic. These are, of necessity, less absolute, but here too she finds nothing inherent in woman’s psychological makeup that dooms her to a role of “immanence.” In some sixty pages, there follows a brief survey of the history of woman from the nomads through the period of the French Revolution to the present day.

Man’s myths about women

Man has always used myths to protect himself from what he has not understood. Mlle. de Beauvoir goes to some lengths to describe man’s myths about woman. She is the Earth Mother and Death; she is Magic and the Servant; she is the Moon and Night, the Sea and Tides. In her study of the myths about woman, Mlle. de Beauvoir has chosen five writers, to show the myth makers’ varying attitudes towards that mystery — the Other. These are: Motherlant, D.H. Lawrence, Claudel, Andre Breton, and Stendhal.

D.H. Lawrence believes that “woman is not evil, she is even good — but subordinated.” Claudel finds woman to be the Handmaid of the Lord. “The more one demands complete submission of her salvation.” In the ever changing forms of his mistresses, Andre Breton holds woman to be the essence of pure poetry.

Finally, breathing a sigh of relief, Mlle. de Beauvoir presents Stendhal as the Romantic of Reality, “demanding woman’s emancipation not only in the name of liberty but also in the name of individual happiness.”

. . . . . . . . .

17 Feminist Quotes from The Second Sex

. . . . . . . . . .

Volume two, “Woman’s Life Today”

This constitutes the sum of the first volume. The second volume, “Woman’s Life Today,” analyzes the great detail in women’s development from childhood through her formative years of young girlhood and sexual initiation to — with a bypass on Lesbianism — marriage, motherhood, and social life — and so on to maturity and old age.

Withe a degree from the Sorbonne, and a considerable career as a novelist, essayist, and teacher of philosophy, Simone de Beauvoir comes to her thesis as a dedicated soul. Her conclusions in The Second Sex are naturally existentialist: there is, she states, no physiologic reason for conflict between man and woman — “The battle of the sexes is not immediately implied in the anatomy of man and woman … The woman who is shut up in immanence endeavors to hold man in that prison also.”

Whether or not one accepts the existentialist’s view, one must find that Mlle. de Beauvoir has done a service in pulling apart the tangled strands of fact and myth about woman’s place in society. The man who is neither sociologist, historian, nor writer may well be uninterested in her report. Most intelligent women will find it rewarding.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

An able and serious piece of writing, if too long

Written in a style that is often declamatory, sometimes shrill, the book is too long. The first volume is better, partly because the second contains an excess of repetition. Eager as Simone de Beauvoir is to be thorough, there is really no scientific check on her statements.

Moreover, while deploring — and rightly this reviewer believes — the dogma of both Freudian and Adlerian psychoanalysts, Mlle. de Beauvoir has in her account of women’s difficulties relied too much on these same psychoanalysts, so that much that she says about presumably normal women is colored by abnormality.

Despite its occasional maddening repetitiousness, The Second Sex is an able and serious piece of writing. Incidentally, the translation is top-notch, and the translator’s notes throw further light on the subject of women in the United States. But there have been other books that in their philosophy have offered an equally good solution.

In any case, if “know thyself” is, as Socrates contended, the beginning of wisdom, Simone de Beauvoir, in having attempted to clear the air of the many hoary superstitions and misconceptions about women, has immensely helped her sex.

More about The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Introduction to Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir (1949) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 14, 2019

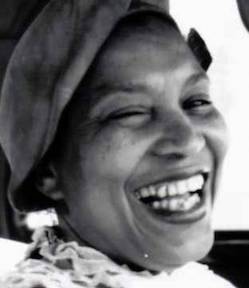

The Enduring Power of For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide by Ntozake Shange

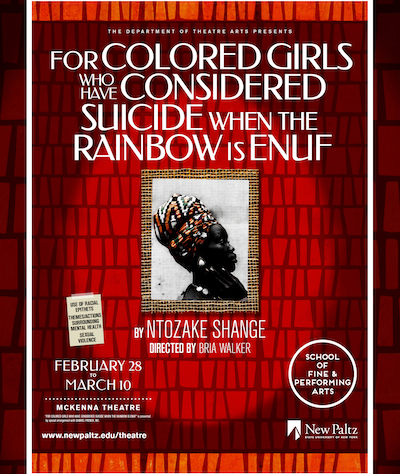

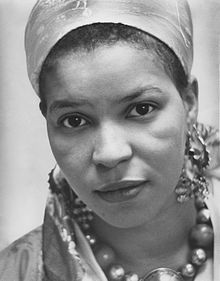

“Through my tears I found god in myself and I loved her fiercely” is perhaps the most iconic quote from For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf by Ntozake Shange (1948 – 2018). For Colored Girls has touched many hearts since it premiered in 1976. The 2019 production of For Colored Girls at SUNY New Paltz was one such powerful and emotional presentation of Shange’s play.

For Colored Girls was Shange’s first work and remains her most acclaimed theatre piece, consisting of twenty captivating poetic monologues representing black sisterhood in a racist and sexist society. Shange describes her work as choreopoem, a form of dramatic expression incorporating poetry, dance, music, and song. This term was coined in 1975 by Shange herself to describe this work.

The play follows the lives of seven African-American women who are identifiable based on the colors of their dresses: Lady in Red, Lady in Orange, Lady in Blue, Lady in Brown, Lady in Yellow, Lady in Purple, and Lady in Green. The nameless women battle issues concerning love, empowerment, struggle, and loss throughout the play. The ladies’ interconnected stories push their relationships to evolve into a heartwarming sisterhood that the audience is sure to feel a part of by the end of the production.

. . . . . . . . . .

Poster for the 2019 production of For Colored Girls … at SUNY New Paltz

. . . . . . . . . . .

It continues to resonate in today’s world

Though Ntozake Shange first staged For Colored Girls over forty years ago, it will continue to resonate for many women who can relate to the struggles portrayed. The harrowing pieces within the play on rape, abortion, domestic violence, and abandonment have the power to touch the lives of viewers, as many women have unfortunately dealt with them at some point in their lives.

Shange allows the audience to live these dark moments, and show them that they are strong enough to make it through. As the script says at the opening of the play, “& this is for colored girls who have considered suicide but moved to the ends of their own rainbows.”

In the introduction to the second publication of For Colored Girls, Shange wrote that “the poems introduce the girls to other kinds of people of color, other worlds. To adventure, kindness, and cruelty. The cruelty that we usually think we face alone, but we don’t. We discover that by sharing with each other we find the strength to go on.” Despite some of the difficult themes, there is also a great sense of love and empowerment.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Ntozake Shange in 1978

. . . . . . . . . . .

A message comes through — you’re not alone

While witnessing these ladies break down from the horrific events they face, we notice that they never go through it alone. For women of color who have been in similarly dark place in their lives, this play’s power is to convey that you’re not alone. The script is extremely intense, especially in scenes where the audience learns about the rape of Lady in Green and the heart-wrenching moment when we learn that Lady in Yellow tested positive for HIV.

When one lady is speaking, the rest of the cast remains on stage and occasionally interrupt the speaker to ask a question. It’s as though they are having a conversation rather than reciting monologues, allowing the audience to realize that these experiences are universal. The emotions of these women are quite raw, as they seem to shed real tears — the audience can forget that they’re watching a production. The impeccable acting and powerful language captivates viewers and moves them to genuinely feel each woman’s pain.

Addressing marginalization and trauma

Through dance and music (as well as poetic dialog), For Colored Girls addresses social issues for women and girls who have felt marginalized, traumatized, or were stuck in a place of judgment by an unforgiving world for being colored. Shange’s words were, and are still, revolutionary. Her play speaks to all women of color who have been affected and allows them to find themselves through Shange’s choreopoem to this day as it still remains relevant.

In 2019, this is a powerful reminder that women of color are still mistreated and silenced by society. The #MeToo movement of 2018 proved just how often sexual abuse of women occurs. The hashtag was used over five hundred thousand times over the course of twenty-four hours after actress Alyssa Milano first tweeted the phrase.

Lady in Red ultimately steals the show with the recital of a night with beau Willie Brown. In this scene, Lady in Red tells the story of her dysfunctional family with her boyfriend who is dealing with PTSD and constantly abusing her and her children. The play was updated in 2010 and included references to the Iraq War as a way to address the same systematic failures that Shange was trying to bring to light in the 1970s.

“I found god in myself and I loved her fiercely”

The play ends with a laying of hands monologue as the ladies come together to express what they are missing. Lady in Purple finally says the iconic line, “through my tears I found god in myself and I loved her fiercely.” All ladies softly recite these lines as they close into a circle with each other. We are reminded of the fact that these social problems started deep in our history and continue to remain present in our world today.

. . . . . . . . . .

For Colored Girls … A Choreopoem by Ntozake Shange on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Here is the 1976 New York Times review of For Colored Girls after it premiered on Broadway, detailing its journey from very small stages to finally arrive on Broadway. For Colored Girls was nominated for a Tony, Grammy, and Emmy. The play was updated in 2010 with a section called “Positive.”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Enduring Power of For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide by Ntozake Shange appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 12, 2019

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë: A 19th-Century Synopsis

Writing as “Ellis Bell,” Emily Brontë‘s only novel,Wuthering Heights, was published in December 1847. The brooding and complex story follows the intersection of two families — the Earnshaws and the Lintons. Catherine Earnshaw and Heathcliff have sparked romantic imaginations as star-crossed lovers whose dramas and tragedies reverberate into the next generation.

Reviewers in Emily’s time were rather perplexed by the novel. Charlotte Brontë felt that her sister Emily’s magnum opus was poorly understood and supplied her own preface to the 1850 edition of Wuthering Heights. By this time, Emily (1818 – 1848) had already died at the age of thirty, and Charlotte had become something of a literary celebrity for the far more successful reception of Jane Eyre. She wrote:

“Whether it is right or advisable to create beings like Heathcliff, I do not know: I scarcely think it is. But this I know: the writer who possesses the creative gift owns something of which he is not always master — something that, at times, strangely wills and works for itself.”

Literary critic Angus Ross commented: “If Wuthering Heights is not approached as a ‘morbid romance’ it can be seen to have a very skillful arrangement. She deals with evil and good, not right and wrong, and the wildness and fierceness of her vision gives her one long work a kind of elemental power not matched in any other novel.”

Any synopsis of Wuthering Heights must, by necessity, mirror its long and complicated story. I found this 19th-century synopsis by Mary F. Robinson to be quite up to the task of encapsulating the narrative. The following is from the book Emily Brontë by Mary F. Robinson (1883). This selection has been edited for clarity. Long quoted sections of dialog have been excluded.

For the unedited selection, go to Emily Brontë and scroll to Chapter XIV, Wuthering Heights: The Story. And before reading the synopsis that starts with the next paragraph, I recommend getting to know the cast of characters to understand their relationship to one another.

A visitor’s nightmare

The first four chapters of Wuthering Heights are merely introductory. They relate Mr. Lockwood’s visit there, his surprise at the rudeness of the place in contrast with the foreign air and look of breeding that distinguished Mr. Heathcliff and his beautiful daughter-in-law. He also noticed the profound moroseness and ill-temper of everybody in the house.

Overtaken by a snowstorm, he was, however, constrained to sleep there and was conducted by the housekeeper to an old chamber, long unused, where (since at first he could not sleep) he amused himself by looking over a few mildewed books piled on one corner of the window-ledge. They and the ledge were scrawled all over with writing, Catherine Earnshaw, sometimes varied to Catherine Heathcliff, and again to Catherine Linton.

Nothing save these three names was written on the ledge, but the books were covered in every fly-leaf and margin with a pen-and-ink commentary, a sort of diary, as it proved, scrawled in a childish hand. Mr. Lockwood spent the first portion of the night in deciphering this faded record; a string of childish mishaps and deficiencies dated a quarter of a century ago.

Evidently this Catherine Earnshaw must have been one of Heathcliff’s kin, for he figured in the narrative as her fellow-scapegrace, and the favorite scapegoat of her elder brother’s wrath. After some time Mr. Lockwood fell asleep, to be troubled by harassing dreams, in one of which he fancied that this childish Catherine Earnshaw, or rather her spirit, was knocking and scratching at the fir-scraped window-pane, begging to be let in.

Overcome with the intense horror of nightmare, he screamed aloud in his sleep. Waking suddenly up he found to his confusion that his yell had been heard, for Heathcliff appeared, exceedingly angry that any one had been allowed to sleep in the oak-closeted room.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Image: https://www.wuthering-heights.co.uk/l...

Image: https://www.wuthering-heights.co.uk/l...You may also enjoy: Quotes from Wuthering Heights

. . . . . . . . . . .

An unwelcome foundling

The story of Wuthering Heights is the story of Heathcliff. It begins with the sudden journey of the old squire, Mr. Earnshaw, to Liverpool one summer morning at the beginning of harvest. He had asked the children each to choose a present, “only let it be little, for I shall walk there and back, sixty miles each way” — and the son Hindley, a proud, high-spirited lad of fourteen, had chosen a fiddle; six-year-old Cathy, a whip, for she could ride any horse in the stable; and Nelly Dean, their humble servant, had been promised a pocketful of apples and pears.

It was the third night since Mr. Earnshaw’s departure, and the children, sleepy and tired, had begged their mother to let them sit up a little longer—yet a little longer—to welcome their father, and see their new presents. At last, just about eleven o’clock Mr. Earnshaw came back, laughing and groaning over his fatigue; and opening his greatcoat, which he held bundled up in his arms, he cried:

“‘See here, wife! I was never so beaten with anything in my life: but you must e’en take it as a gift of God; though it’s as dark almost as if it came from the devil.”

So the child entered ‘Wuthering Heights,’ a cause of dissension from the first. Mrs. Earnshaw grumbled herself calm; the children went to bed crying, for the fiddle had been broken and the whip lost in carrying the little stranger for so many miles. But Mr. Earnshaw was determined to have his protégé respected; he cuffed saucy little Cathy for making faces at the newcomer, and turned Nelly Dean out of the house for having set him to sleep on the stairs because the children would not have him in their bed. And when she ventured to return some days afterwards, she found the child adopted into the family, and called by the name of a son who had died in childhood —Heathcliff.

Mrs. Earnshaw disliked the little interloper and never interfered in his behalf when Hindley, who hated him, thrashed and struck the sullen, patient child, who never complained, but bore all his bruises in silence. This endurance made old Earnshaw furious when he discovered the persecutions to which this mere baby was subjected; the child soon discovered it to be a most efficient instrument of vengeance.

Young Heathcliff continues to sow discord

So the division grew. This malignant, uncomplaining child could only breed discord in that Yorkshire home … Insensible, it seemed, to gratitude … cruel, and violently passionate. One soft and tender speck there was in this dark and sullen heart; it was an exceedingly great and forbearing love for the sweet, saucy, naughty Catherine.

But this one affection only served to augment the mischief that he wrought. He who had estranged son from father, husband from wife, severed brother from sister as completely; for Hindley hated the swarthy child who was Cathy’s favorite companion. When Mrs. Earnshaw died, two years after Heathcliff’s advent, Hindley had learned to regard his father as an oppressor rather than a friend, and Heathcliff as an intolerable usurper. So, from the very beginning, he bred bad feeling in the house.

In the course of time Mr. Earnshaw began to fail. His strength suddenly left him, and he grew half childish, irritable, and extremely jealous of his authority. He considered any slight to Heathcliff as a slight to his own discretion; so that, in the master’s presence, the child was deferred to and courted from respect for that master’s weakness, while, behind his back, the old wrongs, the old hatred, showed themselves unquenched. And so the child grew up bitter and distrustful.

The death of Mr. Earnshaw does nothing to allay a bitter rivalry

Matters got a little better for a while, when the untamable Hindley was sent to college; yet still there was disturbance and disquiet, for Mr. Earnshaw did not love his daughter Catherine, and his heart was yet further embittered by the grumbling and discontent of old Joseph the servant.

But Catherine, though slighted for Heathcliff, and nearly always in trouble on his account, was much too fond of him to be jealous … Suddenly this pretty, mischievous sprite was left fatherless; Mr. Earnshaw died quietly, sitting in his chair by the fireside one October evening. Mr. Hindley, now a young man of twenty, came home to the funeral, to the great astonishment of the household bringing a wife with him.

A rush of a lass, spare and bright-eyed, with a changing, hectic color, hysterical, and full of fancies, fickle as the winds, now flighty and full of praise and laughter, now peevish and languishing. For the rest, the very idol of her husband’s heart. A word from her, a passing phrase of dislike for Heathcliff, was enough to revive all young Earnshaw’s former hatred of the boy.

Heathcliff was turned out of their society, no longer allowed to share Cathy’s lessons, degraded to the position of an ordinary farm-servant. At first Heathcliff did not mind. Cathy taught him what she learned, and played or worked with him in the fields. Cathy ran wild with him, and had a share in all his scrapes; they both bade fair to grow up regular little savages, while Hindley Earnshaw kissed and fondled his young wife utterly heedless of their fate.

Encountering the Lintons

An adventure suddenly changed the course of their lives. One Sunday evening Cathy and Heathcliff ran down to Thrushcross Grange to peep through the windows and see how the little Lintons spent their Sundays. They looked in, and saw Isabella at one end of the, to them, splendid drawing-room, and Edgar at the other, both in floods of tears, peevishly quarreling. So elate were the two little savages from Wuthering Heights at this proof of their neighbors’ inferiority, that they burst into peals of laughter.

The little Lintons were terrified, and, to frighten them still more, Cathy and Heathcliff made a variety of frightful noises; they succeeded in terrifying not only the children but their silly parents, who imagined the yells to come from a gang of burglars, determined on robbing the house.

They let the dogs loose, in this belief, and the bulldog seized Cathy’s bare ankle, for she had lost her shoes in the bog. While Heathcliff was trying to throttle off the brute, the man-servant came up, and, taking both the children prisoner, conveyed them into the lighted hall.

Cathy is transformed

Cathy stayed five weeks at Thrushcross Grange, by which time her ankle was quite well, and her manners much improved. Young Mrs. Earnshaw had tried her best, during this visit, to endeavor by a judicious mixture of fine clothes and flattery to raise the standard of Cathy’s self-respect. She went home, then, a beautiful and finely-dressed young lady, to find Heathcliff in equal measure deteriorated; the mere farm-servant, whose clothes were soiled with three months’ service in mire and dust, with unkempt hair and grimy face and hands.

From this time Catherine’s friendship with Heathcliff was checkered by intermittent jealousy on his side and intermittent disgust on hers; and for this evil turn, far more than for any coarser brutality, Heathcliff longed for revenge on Hindley Earnshaw.

Hindley Earnshaw’s reputation grows ever more terrible

Meanwhile Edgar Linton, greatly smitten with the beautiful Catherine, went from time to time to visit at Wuthering Heights. He would have gone far oftener, but that he had a terror of Hindley Earnshaw’s reputation, and shrank from encountering him.

For this fine young Oxford gentleman, this proud young husband, was sinking into worse excesses than any of his wild Earnshaw ancestors. A defiant sorrow had driven him to desperation. In the summer following Catherine’s visit to Thushcross Grange, his only son and heir had been born. An occasion of great rejoicings, suddenly dashed by the discovery that his wife, his idol, was fast sinking in consumption.

Hindley refused to believe it, and his wife kept her flighty spirits till the end; but one night, while leaning on his shoulder, a fit of coughing took her—a very slight one. She put her two hands about his neck, her face changed, and she was dead. Hindley grew desperate, and gave himself over to wild companions, to excesses of dissipation, and tyranny. “His treatment of Heathcliff was enough to make a fiend of a saint.”

Heathcliff bore it with sullen patience, as he had borne the blows and kicks of his childhood; the aches and wants of his body were redeemed by a fierce joy at heart, for in this degradation of Hindley Earnshaw he recognized the instrument of his own revenge.

Cathy is engaged to Edgar Linton, but not in love

Time went on, ever making a sharper difference between his gypsy soul and his beautiful young mistress time went on, leaving the two fast friends enough, but leaving also in the heart of Heathcliff a passionate rancor against the man who had made him unworthy of Catherine’s hand, and of the other man on whom it was to be bestowed.

For Edgar Linton was infatuated with the naughty young beauty of Wuthering Heights. Her violent temper did not frighten him, although his own character was singularly sweet, placid, and feeble; her compromising friendship with such a mere boor as young Heathcliff was only a trifling annoyance easily to be excused. And when his own father and mother died of a fever caught in nursing her he did not love her less for the sorrow she brought.