Nava Atlas's Blog, page 72

March 7, 2019

My Mortal Enemy by Willa Cather — Two Opposing Reviews

My Mortal Enemy by Willa Cather is a novella by this eminent American author, published in 1926. Cather sketches a character study of a woman and a life not particularly well-lived. In this slim work, the story of an ill-considered marriage unfolds. My Mortal Enemy is considered a minor work by Cather, and there has been debate as to whether it has stood the test of time.

Unlike the nearly universal praise for her major works —My Ántonia, Death Comes for the Archbishop , and O Pioneers! among others, My Mortal Enemy has been received with praise as well as met with disappointment.

In a later edition, this question was posed: “Has the author tried to undo A Lost Lady? There is a definite mark of similarity between the two books, but one feels that she has not come up to her earlier mark, though she has done so admirably.”

This being said, most anything by Willa Cather is worth reading. Even her lesser efforts are on a par with the finest of other authors (notably, male authors) who are still read and studied. It’s always fascinating to see how classic works were received when they were first came out. Following are two reviews from 1926, when the work was first published, stating opposing views.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: A 1918 Review of My Antonia

. . . . . . . . . . .

This reviewer likes My Mortal Enemy’s brevity

From The Ithaca Journal, December 31, 1926: Anyone who overlooks Willa Cather’s My Mortal Enemy is cheating themselves. It is to be classed among the truly fine literature of this year. A small book it is, with not a word to spare, and consumes not more than two hours in the most thorough-going reading. Its space proportions are scarcely more than those of a magazine short story, but its literary proportions are greater than almost any novel of the year.

Willa Cather is a recognized artist. If she were not so recognized previously, this novelette would give her the stamp. Almost any hack writer can sit down and tap off a story of voluminous proportions, but it takes a Willa Cather to compress what most would make into a lengthy tome. Subtract or add a word and you would spoil the effect.

My Mortal Enemy is a poignant character study of an extraordinary woman she is the woman of commanding personality and unaccountable moods, of impulsive action and acquisitive intelligence. She lives and she dies, and Willa Cather knew her, in her imagination.

A cumulative series of incidents, on the surface seemingly trivial build up the powerful climax. Every one of them is essential to the portrait. My mortal enemy suggests the most desirable prospect for the novel of the future. Why must novels be often so inordinately longer than the material within them warrants, padded out with all manner of unnecessary incident and comment by the author?

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: 7 Later Novels by Willa Cather

. . . . . . . . . .

This reviewer finds the story fragmentary

From The Cincinnati Enquirer, November 6, 1926: When Willa Cather wrote My Antonia she put herself in the way of a challenge. Since the richness and glow of Antonia burst upon her public she probably has been one of the for most victims of self-comparison. Most of these — justly, all of them — have been unfavorable. Willa Cather has run a descending scale. Each succeeding book — A Lost Lady, One of Ours, The Professor’s House — has been more noticeably inferior. Inferior, that is, to the magnificent My Antonia.

My Mortal Enemy is the latest and the least of them all. In size it is nothing more than a fairly long short story; in effect, it is hardly more than a suggestion, without roundness and without body. It is scarcely even a skeleton. Selection and compression are great virtues in a literary artist, but like the virtue of renunciation, they can be carried too far.

Myra Driscoll, the subject of My Mortal Enemy, carried renunciation beyond the power of her temperament to survive the loss. She was reared in luxury, was denied nothing, and in colloquial expression, spoiled. After all, her wealthy uncle did deny her one thing — the love of Oswald Henshaw. The uncle told her that she could marry Henshaw or inherit her fortune, but not both.

She chose Henshaw and eloped with him; never thereafter did she forgive her husband for the loss he had caused her.

The story is told by one Nellie Birdseye, who is quite extraneous to the story and has no real business in it. The author employed the same method in My Antonia and A Lost Lady, but in those cases, the interpreters bore an actual relationship to the characters and their doings. Not so Nellie.

She tells us of two periods in the life the Henshaws. The first narrative, with a recapitulation of earlier affairs, comes when the pair have been married twenty years. They had been deeply in love, at Henshaw’s income could not keep Myra, who was used to luxury, at all content. Myra wanted to make a show; the thought another woman possessed advantages beyond her own aroused her violent nature.

She was also extremely generous, as a poseur is generous, for she was very vain. She would give away anything that she had — and then demand that her husband replace it. Therefore, they were always in straitened circumstances.

There’s a lapse of ten years and Nellie Birdseye again takes up the interpretation of the Henshaws. They are in the West; also, they are in poverty. Myra is broken in health and in spirit. She hates her husband and all the circumstances of her life. Except for her regrets and her husband she is alone. Yet before her death, she turns upon him and accuses him of having ruined her life.

“Why,” she asks him — and she is still the selfish poseur that she has been throughout her life — “must I die like this, alone with my mortal enemy?”

The question is not answered, and the book is put aside with the feeling that Myra is not at all realized. Her character, like her story, is fragmentary. She is presented without the significant incident that at times has made Willa Cather’s work so vital. Though the reader is told that Myra is generous and imaginative, she is made to do nothing to prove these qualities. One loses sympathy with her, and that is fatal.

. . . . . . . . . .

My Mortal Enemy by Willa Cather on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post My Mortal Enemy by Willa Cather — Two Opposing Reviews appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 4, 2019

10 Poems by Gabriela Mistral About Life, Love, and Death

Gabriela Mistral (April 7, 1889 – January 10, 1957, also known as Lucila Godoy Alcayaga) was a Chilean poet, educator, diplomat, and feminist. She’s best known for being the first Latina to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Mistral stopped formally attending school at the age of fifteen to care for her sick mother, but continued to write poetry. Just two years later, heart completely broke after the sad deaths of her lover, Romeo Ureta, and a close nephew.

This heartbreak gave her the inspiration to create some of her best works, including Sonetos de la muerte (1914). Much of her later poetry was focused on the theme of death, as you’ll read in some of her poems, following. Here are ten poems by Gabriela Mistral about life, love, and death, both in their original Spanish, and in English translation.

Canción de la Muerte (Song of Death), 1914

La vieja Empadronadora,

la mañosa Muerte,

cuando vaya de camino,

mi niño encuentre.

La que huele a los nacidos

y husmea su leche,

encuentre sales y harinas,

mi leche no encuentre.

La Contra-Madre del Mundo,

la Convida-gentes,

por las playas y las rutas

no halle al inocente.

El nombre de su bautismo

– la flor con que crece –

lo olvide la memoriosa,

lo pierda, la Muerte.

De vientos, de sal y arenas

se vuelve demente,

y trueque, la desvariada,

el Oeste, y el Este.

Niño y madre los confunda

los mismo que peces,

y en el dia y en la hora

a mi sola encuentre.

Song of Death

Old Woman Census-taker,

Death the Trickster,

when you’re going along,

don’t you meet my baby.

Sniffing at newborns,

smelling for the milk,

find salt, find cornmeal,

don’t find my milk.

Anti-Mother of the world,

People-Collector —

on the beaches and byways,

don’t meet that child.

The name he was baptized,

that flower he grows with,

forget it, Rememberer.

Lose it, Death.

Let wind and salt and sand

drive you crazy, mix you up

so you can’t tell

East from West,

or mother from child,

like fish in the sea.

And on the day, at the hour,

find only me.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: 8 Fascinating Facts about Gabriela Mistral

. . . . . . . . . .

Dame la Mano (Give Me Your Hand)

Dame la mano y danzaremos;

dame la mano y me amarás.

Como una sola flor seremos,

como una flor, y nada más…

El mismo verso cantaremos,

al mismo paso bailarás.

Como una espiga ondularemos,

como una espiga, y nada más.

Te llama Rosa y yo Esperanza:

pero tu nombre olvidarás,

porque seremos una danza

en la colina, y nada más…

Give Me Your Hand

Give me your hand and give me your love,

give me your hand and dance with me.

A single flower, and nothing more,

a single flower is all we’ll be.

Keeping time in the dance together,

you’ll be singing the song with me.

Grass in the wind, and nothing more,

grass in the wind is all we’ll be.

I’m called Hope and you’re called Rose:

but losing our names we’ll both go free,

a dance on the hills, and nothing more,

a dance on the hills is all we’ll be.

. . . . . . . . . .

Canto que Amabas (What You Loved)

Yo canto lo que tú amabas, vida mía,

Por si te acercas y escuchas, vida mía,

por si te acuerdas del mundo que viviste,

al atardecer yo canto, sombra mía.

Yo no quiero enmudecer, vida mía.

¿Cómo sin mi grito fiel me hallarías?

¿Cuál señal, cuál me declara, vida mía?

Soy la misma que fue tuya, vida mía.

Ni lenta ni trascordada ni perdida.

Acude al anochecer, vida mía,

ven recordando un canto, vida mía,

si la canción reconoces de aprendida

y si mi nombre recuerdas todavía.

Te espero sin plazo y sin tiempo.

No temas noche, nebline ni aguacero.

Acude con sendero o sin sendero.

Llámame a donde tú eres, alma mía,

y marcha recto hacia mí, compañero.

What You Loved

Life of my life, what you loved I sing.

If you’re near, if you’re listening,

think of me now in the evening:

shadow in shadows, hear me sing.

Life of my life, I can’t be still.

What is a story we never tell?

How can you find me unless I call?

Life of my life, I haven’t changed,

not turned aside and not estranged.

Come to me as the shadows grow long,

come, life of my life, if you know the song

you used to know, if you know my name.

I and the song are still the same.

Beyond time or place I keep the faith.

Follow a path or follow no path,

never fearing the night, the wind,

call to me, come to me, now at the end,

walk with me, life of my life, my friend.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Gabriela Mistral

. . . . . . . . . .

Elogio de la sal (In Praise of Salt)

La sal que, en los mojones de la playa de Eva del año 3000,

parece frente cuadrada y hombros cuadrados,

sin paloma tibia ni rose viva en la mano

y de la roca que brilla

más que la foca de encima,

capaz de volver toda joya.

La sal que blanquea,

vientre de gaviota y cruje en la pechuga del pingüino

y que en la madreperla juega

con los colores que no son suyos.

La sal es absoluta y pura como la muerte.

La sal que clavetea en la corazón de los buenos

y hasta el de N.S.J. hará que no se disuelvan en la piedad.

In Praise of Salt

The salt, in great mounds on the beach of Eve in the year 3,000,

seems squared off in front and squared off in the back,

holding no warm dove nor living rose in its hand,

and the salt of the rock salt that gleams,

even more than the seal on its peak,

capable of turning everything into a jewel.

The salt that bleaches the seagull’s belly

and crackles in the penguin’s breast,

and that in mother-of-pearl plays

with colors that are not its own.

The salt is absolute and pure as death.

The salt nailed through the hearts of good people,

even the heart of our Lord Jesus Christ, keeps them from dissolving in piety.

. . . . . . . . . .

Los cabellos de los niños (Children’s Hair)

Cabellos suaves, cabellos que son toda la suavidad del mundo:

Que seda gozaría yo si no os tuviera sobre el regazo?

Dulce por ella el dia que pasa, dulce el sustento,

dulce el antiguo dolor, solo por unas horas que ellos resbalan entre mis manos.

Ponedlos en mi mejilla;

Revolvedlos en mi regazo como las flores;

dejadme trenzar con ellos, par suavizarlo, mi dolor;

aumentar la luz con ellos, ahora que es moribunda.

Cuando ya sea con Dios, que no me de el ala de un ángel,

para frescar la magulladura de mi corazón;

extienda sobre el azul las cabelleras de los niños que ame,

y pasen ellas en el viento sobre mi rostro eternamente!

Children’s Hair

Soft hair, hair that is all the softness of the world:

without you lying in my lap, what silk would I enjoy?

sweet the passing day because of that silk, sweet the sustenance,

sweet the ancient sadness, at least for the few hours it slips between my hands.

Touch it to my cheek;

wind it in my lap like flowers;

let me braid it, to soften my pain,

to magnify the light with it, now that it is dying.

When I am with God someday, I do not want an angel’s wing

to cool my heart’s bruises;

I want, stretches against the sky, the hair of the children I loved,

to let it blow in the wind against my face eternally!

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Poemas de las madres (Poems of the Mothers)

Me ha besado y yo soy otra;

por el latido que duplica el de mis venas;

otra; por el aliento que se percibe entre el aliento.

Mi vientre ya es noble como mi corazón …

Y hasta encuentro en mi hálito una exhalación de flores:

¡todo por aquel que descansa en mis entrañas blandamente,

como el rocío sobre la hierba!

Poems of the Mothers

I was kissed, and I am othered: another,

because of the pulse that echoes the pulse in my veins;

another, because of the breath I feel within my breath.

My belly, now, is as noble as my heart …

And now I feel in my own breathing an exhalation of flowers:

all because of the one who rests inside me gently,

as the dew on the grass!

. . . . . . . . . .

El arte (Art)

I. La belleza

Una canción es una herida amor que nos abrieron las cosas.

A ti, hombre, basto, solo te turba un vientre de mujer,

un montón de carne de mujer. Nosotros vamos turbados,

nosotros recibimos la lanzada de toda la belleza del mundo,

porque la noche estrellada nos fue amor tan agudo como un amor de carne.

Una canción es una respuesta que damos a la hermosura del mundo.

Y la damos con un temblor incontenible,

como el tuyo delante de un seno desnudo.

Y de volver en sangre esta caricia de la Belleza,

y de responder al llamamiento innumerable de ella por los caminos,

vamos más febriles, vamos más flagelados que tú,

nosotros, los puros.

Art

I. Beauty

A song is the wound of love that things open in us.

Coarse man, the only thing that arouses you is the woman’s womb,

a mass of female flesh. But our disquiet is continuous;

we feel the thrust of all the beauty of the world,

because the starry night was for us a love as sharp as carnal love.

A song is a response we offer to the beauty of the world.

And we offer that response with an uncontainable tremor,

just as you tremble before a naked breast.

And because we return, in blood, this caress of Beaut,

and because we respond to Beauty’s infinite calling through the paths,

we walk more timorously, more reviled than you:

we, the pure.

. . . . . . . . . .

El girasol (The Sunflower)

“Ya se el de arriba. Pero las hierbas enanas no lo ven

y creen que soy yo quien las calienta

y les da la lamedura de la tarde”.

Yo –ya veis que mi tallo es duro– no les contestado

ni con una inclinación de cabeza.

Nada engaño mio, pero las dejo encarnarse

porque nunca alcanzarán a aquel que, por otra parte,

las quemaría, y a mi en cambio hasta me tocan los pies.

Es bastante esclavitud hacer el son. Este volverse al Oriente y al ocaso

y ester terriblemente atento a la posición de aquel,

cansa mi nunca, que no agil.

Ellas, las hierbas, siguen cantando allá abajo:

“El sol tiene cuatrocientos hojas de oro,

un gran disco oscuro al centro y un tallo soberano”.

Las oigo, pero no les doy señal de afirmación con mi cabeza.

Me callo; pero se, para mi, que es el de arriba.

The Sunflower

“I know for certain it is he, the one up above. But the little plants don’t see him,

and they believe it is I who warms them

and licks them all afternoon.”

I –whose stem is hard, as you can see– I never answer them,

not even with a nod of the head.

It’s no deception on my part, but I let them deceive themselves,

because they will never reach him, who would burn them in any case.

As for me, on the other hand, they hardly even reach my feet.

It’s a form of great servitude to be the sun.

This turning towards the East and towards the sunset,

constantly attending to his position,

tires my neck, which is not so limber.

And they, the little grasses, they continue to sing down there:

“The sun has four hundred golden leaves,

a great dark disc at the center, and a sovereign stem.”

I hear them, but I offer them no confirming sign with my head.

I keep quiet, but as for me. I know for certain it is he, the one up above.

. . . . . . . . . .

Pan (Bread)

Vicio de la costumbre. Maravilla de la infancia,

sentido mágico de las materias y los elementos:

harina, sal, aceite, agua, fuego.

Momentos de vision pura, de audicion pura, de palpacion pura.

La conciencia de la vida en un momento.

Todos los recuerdos en torno de un pan.

Una sensación muy fuerte de vida trae consigo

por no se que aproximacion interior, un pensamiento igualmente poderoso de la muerte.

El pensamiento de la vida banaliza desde el momento en que no se mezcla al de la muerte.

Los vitales puros son grandes superficiales o pequeños paganos.

El pagano se ocupó de las dos cosas.

Bread

Vice of habituation. Wonder of childhood,

magical feeling of raw materials and elements:

flour, salt, oil, water, fire.

Moments of pure vision, pure hearing, pure touch.

Consciousness of life at one moment.

All the memories revolve around bread.

It carries an intense sense of life, and also,

through I don’t know what internal association, an equally strong sense of death.

The thought of life turns banal from the moment it isn’t blended with the thought of death.

The pure essentials are superficial giants or little pagans.

The pagan paid attention to both.

. . . . . . . . . .

Elogio de la sal (In Praise of Salt)

La sal que, en los mojones de la playa de Eva del año 3000,

parece frente cuadrada y hombros cuadrados,

sin paloma tibia ni rosa viva en la mano

y de la roca que brilla más que la foca encima,

capaz de volver toda joya.

La sal que blanquea, vientre de gaviota

y crujie en la pechuga del pingüino

y que en la madreperla juega con los colores que no son suyos.

La sal es absoluta y pura como la muerte.

La sal que clavetea en la corazón de los buenos

y hasta el de N.S.J. hará que no se disuelvan en la piedad.

In Praise of Salt

The salt, in great mounds on the beach of Eve in the year 3,000,

seems squared off in front and squared off in the back,

holding no warm dove nor living rose in its hand,

and the salt of the rock salt that gleams,

even more than the seal on its peak,

capable of turning everything into a jewel.

The salt that bleaches the seagull’s belly

and crackles in the penguin’s breast,

and that in mother-of-pearl plays with colors that are not its own.

The salt is absolute and pure as death.

The salt nailed through the hearts of good people,

even the heart of our Lord Jesus Christ, keeps them from dissolving in piety.

. . . . . . . . . .

Gabriela Mistral page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 10 Poems by Gabriela Mistral About Life, Love, and Death appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 3, 2019

8 Fascinating Facts About Gabriela Mistral, Latina Nobel Prize Winner

Gabriela Mistral, born Lucila Godoy Alcayaga (April 7, 1889 – January 10, 1957), was a Chilean poet, educator, diplomat, and feminist. She grew up living in poverty with her family in a small Andean village of Montegrande and developed her father’s gift for teaching despite having dropped out of school at age fifteen.

After multiple notable works including Sonetos de la muerte (1914) and Lagar (1954), Mistral received national recognition and praise as her was translated into various languages from her native Spanish. Though she is best known for being the first Latin American woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, she did so much more during her remarkable life. Here are some fascinating facts about Gabriela Mistral that may inspire you to learn more about her, and better yet, to read her work.

She was involved in diplomatic activity

Mistral was heavily involved with diplomatic activity as she served as honorary consul at Madrid, Lisbon, Nice, Brazil, and in Los Angeles. In addition, she also served as a representative of Latin America in the Institute for Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations and the United Nations. Thanks to her participation in these activities, she was able to travel to nearly every major country in Europe and Latin America.

Her work was influenced by heartbreak

Mistral met her first love, a young railroad worker named Romelio Ureta, in 1906. Sadly, he killed himself in 1909. After Ureta’s death, she found love again, though it didn’t last very long — her second love married somebody else.

After getting her heart badly broken twice, she felt inspired to write about her painful emotions . Writing about her lover’s suicide allowed her to gain a different perspective on death than the previous generations of Latin American poets. This is when she created her first recognized literary work in 1914, Sonetos de la muerte.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Gabriela Mistral

. . . . . . . . . .

Much of her later poetry was focused on the theme of death

After winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1945, Mistral’s heart completely broke once again after the suicide of her nephew who she adopted and raised as her son. Around the same time, her good friends Stefan Zweig and his wife also committed suicide.

While trying to cope with the loss of many loved ones, Mistral was dealing with a health issue as well. As a result of her diabetes diagnosis, most of her last works implied that she was awaiting death and had complete faith in God to leave it in his hands.

Her pen name was inspired by two of her favorite poets

After winning the Juegos Florales in the Chilean capital, Santiago, she used her given name, Lucila Godoy, at times for her publications. Shortly after, she then formed her pseudonym from two of her favorite poets, Gabriele D’Annunzio and Frédéric Mistral in 1908. From then on, she has been using the pen name, Gabriela Mistral, for most of her writing.

Some believe she was a “closet lesbian”

During the 1970s and 80s, Gabriela Mistral’s image was presented by the military dictatorship of Pinochet as the symbol of “submission to the authority” and “social order.” Licia Fiol-Matta, an assistant professor of Spanish and Latin American Cultures at Barnard College challenges her saint-like celibate image and claims that she was a closet lesbian.

Chilean poet Volodia Teitelboim claims that he hasn’t found any indications that she might be a lesbian in her writing. In the early 2000s, some love letters were discovered between Mistral and a male poet after a thesis of the lesbianism of Mistral was put forward. She died in 1957 with Doris Dana by her side. Dana inherited her estate after Mistral’s death.

She used her poetry as a voice for the voiceless

Growing up in poverty made Mistral sympathetic to those who were vulnerable. She also defended the freedoms of democracy and pushed for peace during social, political, and ideological conflicts, not only in Latin America but around the world.

She took the side of those who were mistreated by society, including children, women, Native Americans, Jews, workers, war victims, and the poor. She turned to poetry, newspaper articles, letters, and her actions as she was a Chilean representative in international organizations. Her main concern was the future of Latin America and its cultures, specifically in native groups.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The Bible was one of the books that influenced her the most

Mistral’s grandmother was an extremely religious person. As a child, Mistral was encouraged by her grandmother to learn and recite passages from the Bible, specifically the Psalms of David. Eventually, she was able to recite passages by heart. Mistral later said in her poem, Mis Libros, that the Bible was one of the books that influenced her writing the most.

She died of pancreatic cancer in New York City

Toward the end of an active life, Mistral became unable to travel due to her declining health. She developed diabetes in 1944 and sought medical aid in the United States in 1946.

Later on, she was given more devastating news. Mistral was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and passed away in Hempstead Hospital in New York City at the age of sixty-seven in 1967. She was buried in Chile where thousands of Chileans gathered together to mourn the death of a spectacular woman.

The post 8 Fascinating Facts About Gabriela Mistral, Latina Nobel Prize Winner appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 1, 2019

Was Charlotte Brontë’s “Shirley” an Idealized Portrait of Her Sister Emily?

Shirley, the second published novel by Charlotte Brontë, was published in 1849, still under the pseudonym Currer Bell. Charlotte had already achieved fame and notoriety with the wildly successful Jane Eyre under her masculine nom de plume. The question we’ll be exploring here is how much of Shirley’s character did Charlotte draw from her sister Emily’s.

A more challenging novel to read than Jane Eyre, Shirley: A Tale is now considered a prime example of the mid-19th century “social novel.” The social novels that emerged from that period were works of fiction dealing with themes like labor injustice, abuse of and bias against women, and poverty.

Shirley is set in Charlotte’s native Yorkshire in 1811 and 1812, and takes place against the scene of the Luddite uprisings in the Yorkshire textile industry. It must have been a lonely endeavor for Charlotte, who, having gotten used to her sisters Anne and Emily as writing companions, was now the only surviving sibling. Anne, Emily, and their brother Branwell had not long before et their untimely deaths.

The rise of the social novel

A fellow novelist who became known for the genre of social novel was Elizabeth Gaskell, who, incidentally, was also well known for her Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857). This posthumous biography that helped cement its subject’s literary legacy shortly after her death. Her novel Mary Barton, which preceded Shirley by just a year, and termed an “industrial novel,” explored the relationships between workers and their employers.

Since Charlotte may have already been hard at work on Shirley, it’s hard to tell how much she may have been influenced by Mrs. Gaskell’s book by the time of its publication.

What makes Shirley fascinating is that Charlotte had told Mrs. Gaskell that the character of Shirley is how she imagined Emily may have turned out if she had enjoyed the benefits of wealth and privilege. Another character, Caroline Helstone, may have been loosely inspired by Anne, though others thought she may have been based on Charlotte’s dear friend Ellen Nussey.

Following is an excerpt from Emily Brontë by Mary F. Robinson. Diving back to 1883, it presents an insightful exploration of the parallel between the real-life Emily, in all her odd complexity, and the character of Shirley:

A novel with a grace and beauty of its own

Exxcerpted and condensed from Emily Brontë by Mary F. Robinson, 1883: Shirley has never attained the steady success of her masterpiece, Villette, neither did it meet with the furor which greeted the first appearance of Jane Eyre. It is, indeed, inferior to either work; a very quiet study of Yorkshire life, almost pettifogging in its interest in ecclesiastical squabbles, almost absurd in the feminine inadequacy of its heroes.

And yet Shirley has a grace and beauty of its own. This it derives from the charm of its heroines—Caroline Helstone, a lovely portrait in character of Charlotte’s dearest friend, and Shirley herself, a fancy likeness of Emily Brontë.

Emily Brontë, but under very different conditions. No longer poor, no longer thwarted, no longer acquainted with misery and menaced by untimely death; not thus, but as a loving sister would fain have seen her, beautiful, triumphant, the spoiled child of happy fortune.

Yet in these altered circumstances Shirley keeps her likeness to Charlotte’s hardworking sister; the disguise, haply baffling those who, like Mrs. Gaskell, “have not a pleasant impression of Emily Brontë,” is very easily penetrated by those who love her …

Charlotte’s portrait gives us another view, and fortunately there are still a few alive of the not numerous friends of Emily Brontë. Every trait, every reminiscence paints in darker, clearer lines, the impression of character which Shirley leaves upon us. Shirley is indeed the exterior Emily, the Emily that was to be met and known thirty-five years ago, only a little polished, with the angles a little smoothed, by a sister’s anxious care …

. . . . . . . . . .

The Brontë sisters, in a painting by their brother, Branwell

Charlotte wrote much about their paths to publication

. . . . . . . . . .

An echo of Emily and her fierce dog

But to know how Emily Brontë looked, moved, sat and spoke, we still return to Shirley. A host of corroborating memories start up in turning the pages. Who but Emily was always accompanied by a “rather large, strong, and fierce-looking dog, very ugly, being of a breed between a mastiff and a bulldog?” it is familiar to us as Una’s lion; we do not need to be told, Currer Bell, that she always sat on the hearth rug of nights, with her hand on his head, reading a book; we remember well how necessary it was to secure him as an ally in winning her affection.

Has not a dear friend informed us that she first obtained Emily’s heart by meeting, without apparent fear or shrinking, Keeper’s huge springs of demonstrative welcome?

How characteristic, too, the touch that makes her scornful of all that is dominant, dogmatic, avowedly masculine in the men of her acquaintance; and gentleness itself to the poetic Philip Nunnely, the gay, boyish Mr. Sweeting, the sentimental Louis, the lame, devoted boy-cousin who loves her in pathetic canine fashion. That courage, too, was hers.

Not only Shirley’s flesh, but Emily’s, felt the tearing fangs of the mad dog to whom she had charitably offered food and water; not only Shirley’s flesh, but hers, shrank from the light scarlet, glowing tip of the Italian iron with which she straightway cauterized the wound, going quickly into the laundry and operating on herself without a word to any one.

Emily, also, singlehanded and unarmed, punished her great bulldog, Keeper, for his household misdemeanors, in defiance of an express warning not to strike the brute, lest his uncertain temper should rouse him to fly at the striker’s throat. And it was she who fomented his bruises. This prowess and tenderness of Shirley’s is an old story to us.

. . . . . . . . . .

Shirley by Charlotte Brontë on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

More parallels between Shirley and Emily

And Shirley’s love of picturesque and splendid raiment is not without an echo in our memories. It was Emily who, shopping in Bradford with Charlotte and her friend, chose a white stuff patterned with lilac thunder and lightning, to the scarcely concealed horror of her more sober companions.

And she looked well in it; a tall, lithe creature, with a grace half-queenly, half-untamed in her sudden, supple movements, wearing with picturesque negligence her ample purple-splashed skirts; her face clear and pale; her very dark and plenteous brown hair fastened up behind with a Spanish comb; her large grey-hazel eyes, now full of indolent, indulgent humor, now glimmering with hidden meanings, now quickened into flame by a flash of indignation, “a red ray piercing the dew.”

She, too, had Shirley’s taste for the management of business. We remember Charlotte’s disquiet when Emily insisted on investing Miss Branwell’s legacies in York and Midland Railway shares.

“She managed, in a most handsome and able manner for me when I was in Brussels, and prevented by distance from looking after our interests, therefore I will let her manage still and take the consequences. Disinterested and energetic she certainly is; and, if she be not quite so tractable or open to conviction as I could wish, I must remember perfection is not the lot of humanity, and, as long as we can regard those whom we love, and to whom we are closely allied, with profound and never-shaken esteem, it is a small thing that they should vex us occasionally by what appear to us headstrong and unreasonable notions.”

So speaks the kind elder sister, the author of Shirley. But there are some who will never love either type or portrait. Sydney Dobell spoke a bitter half-truth when, ignorant of Shirley’s real identity, he declared: “We have only to imagine Shirley Keeldar poor to imagine her repulsive.”

. . . . . . . . . .

See also:Villette by Charlotte Brontë — a Portrait of a Woman in Shadow

. . . . . . . . . .

The world has no use for a poor and plain woman

The silenced pride, the thwarted generosity, the unspoken power, the contained passion of such a nature are not qualities which touch the world when it finds them in an obscure and homely woman. Even now, very many will not love a heroine so independent of their esteem. They will resent the frank imperiousness, caring not to please, the unyielding strength, the absence of trivial submissive tendernesses, for which she makes amends by such large humane and generous compassion.

“In Emily’s nature,” says her sister, “the extremes of vigor and simplicity seemed to meet. Under an unsophisticated culture, inartificial taste and an unpretending outside, lay a power and fire that might have informed the brain and kindled the veins of a hero; but she had no worldly wisdom—her powers were unadapted to the practical business of life—she would fail to defend her most manifest rights, to consult her legitimate advantage. An interpreter ought always to have stood between her and the world. Her will was not very flexible and it generally opposed her interest. Her temper was magnanimous, but warm and sudden; her spirit altogether unbending.”

Terrible difference between ideas and truth

Disinterested, headstrong, noble Emily Brontë, at this time, while your magical sister was weaving for you, with golden words, a web of fate as fortunate as dreams … you were never to see the brightest things in life. Sisterly love, free solitude, unpraised creation, were to remain your most poignant joys. No touch of love, no hint of fame, no hours of ease, lie for you across the knees of Fate. Neither rose nor laurel will be shed on your coffined form. Meanwhile, your sister writes and dreams for Shirley. Terrible difference between ideas and truth; wonderful magic of the unreal to take their sting from the veritable wounds we endure!

Neither rose nor laurel will we lay reverently for remembrance over the tomb where you sleep; but the flower that was always your own, the wild, dry heather. You, who were, in your sister’s phrase, “moorish, wild and knotty as a root of heath,” you grew to your own perfection on the waste where no laurel rustles its polished leaves, where no sweet, fragile rose ever opened in the heart of June.

But now you live, still singing of freedom, the undying soul, of courage and loneliness, another voice in the wind, another glory on the mountain-tops, Emily Brontë, the author of Wuthering Heights.

Condensed from Emily Brontë by Mary F. Robinson, 1883. Follow this link to read the entire chapter.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing.

The post Was Charlotte Brontë’s “Shirley” an Idealized Portrait of Her Sister Emily? appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 28, 2019

Tasha Tudor and Her Beloved Corgis: “How could you resist a Corgi?”

Tasha Tudor (August 28, 1915 – June 18, 2008) not only wrote and illustrated some two dozen of her own titles, but her exquisitely detailed watercolors and drawings grace scores of other books. Her writing and art have earned her a secure place in children’s literature, yet she became nearly as famous for her unconventional lifestyle.

Anyone who knows a bit about Tasha’s private life will know that she was a consummate Corgi lover. And if this is news to you, you’re in for a treat.

Tasha’s art and books go straight to the heart of nostalgia, harking back to an abiding love for simpler days gone by. Some of the best known children’s books Tasha illustrated include the classics Mother Goose and The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett.

Tasha Tudor’s Corgis received her abiding affection. “How could you resist a Corgi?” she was known to ask. Indeed, it’s hard to think of a more adorable dog.

In turn, Tasha Tudor’s name is well known and revered in the global Corgi community. Given her love for them, it’s not surprising that her preserved home in Marlboro, Vermont is called The Corgi Cottage (which you can visit in season). Jeanette Chandler Knazek, Consulting Curator of The Corgi Cottage, introduces Tasha:

“For the November 1941 issue of the Horn Book Magazine for Boys and Girls, Tasha had penned a short piece titled ‘Out of New England,’ in which she eloquently described some of the sights and experiences of her childhood while learning to appreciate all that New England had to offer, particularly in the ways of nature. For the rest of her life, Tasha would continue to explore New England’s history, cherishing its days and ways.”

. . . . . . . . .

Tasha at her home in Marlboro, Vermont; Photo: Patricia Denys

. . . . . . . . .

Born in Boston, Tasha has been referred to as an “unconventional Martha Stewart,” for creating an idyllic New England existence that time seemed to forget. This “back-to-the-land” lifestyle included spinning her own fabric for making her trademark old-fashioned dresses, raising Nubian goats, and recreating bygone pastimes. But what seemed to give her great pleasure were her beloved Corgis.

Her foray into the world of Corgis, both in her life and art, seemed to start around the late 1950s. According to the homage to Tasha on Welsh Corgi News:

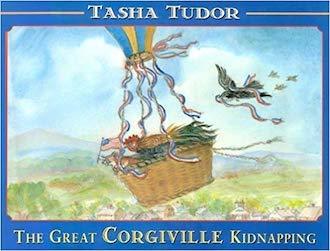

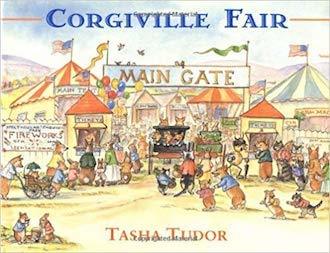

“Inevitably it was only a matter of time before Corgis began to feature in Tasha Tudor’s work; sometimes as the focal point of an illustration, often as a detail, but the Tudor Corgis are quite ubiquitous! Indeed, they have been the subject of three entire books: Corgiville Fair (1971), The Great Corgiville Kidnapping (1997) and Corgiville Christmas (2002).”

. . . . . . . . .

Tasha and her corgis, Rebecca and Owyn; photo: Patricia Denys

. . . . . . . . .

Patricia Denys and Mary Holmes were fortunate to have met Tasha on her home turf when they collaborated on a 1998 book titled Animal Magnetism: At Home With Celebrities and Their Animal Companions. Denys recalls:

“We had created a wish list of humans we would like to photograph with their companion animals. Tasha Tudor was on that list. We contacted her manager at the time, who was extremely open to the idea and arranged for us to not only photograph Tasha but to spend the night at her enchanting farm. At dusk, she served us black tea and her custom apricot cobbler. I was spellbound. Her home, the animals, the property and the autumn air were all seductive.

We followed her for a day and were told that night if we wanted to see her ‘goat cafeteria’ the next day we needed to be up at dawn to watch her feed the animals! Tasha used one of my photographs of her from that first meeting for her book jacket for The Great Corgiville Kidnapping.

We visited Tasha over four Autumns; one included polishing her numerous copper pots at her request after we volunteered to help with chores if needed. She had no trouble thinking of something for us to do.

Tasha, her goats, birds, cat, and beloved Corgyn were some of the most photogenic subjects we had ever photographed. It was a remarkable experience knowing Tasha Tudor and being able to record a small part of her amazing life as an artist.”

See more of Patricia Denys’s Tasha Tudor photos here.

. . . . . . . . .

Finally, we’ll leave you with a few choice quotes by Tasha Tudor, Corgi lover extraordinaire:

“Corgis are enchanted. You need only to see them in the moonlight to know this.”

“There is no other dog that can compare to a Corgi. They’re the epitome of beauty.”

“They’re such characters. A mixture of a dog and a cat, I think.”

“I have a one-track mind when it comes to Corgis. I think it is because they are Welsh, and my ancestors came from Wales. Don’t you think people look like their dogs? Just like a man and wife who come to look like one another in a very happy marriage.”

. . . . . . . . .

Tasha Tudor’s corgi books

The Great Corgiville Kidnapping

. . . . . . . . .

Corgiville Fair

. . . . . . . . .

Corgiville Christmas

. . . . . . . . .

You Might Also Enjoy: Classic Women Authors and Their Dogs and Cats

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Tasha Tudor and Her Beloved Corgis: “How could you resist a Corgi?” appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 27, 2019

A Lost Lady by Willa Cather (1923)

A Lost Lady (1923) is a shining example of Willa Cather’s gift for concise expression and talent for vivid character studies. Marian Forrester, a young woman of beauty and grace, brings an uncommon air of sophistication to the frontier town of Sweet Water. She wound up in this town, which lay along the Transcontinental Railroad, through her marriage to the much older Captain Daniel Forrester.

The novel is written from the viewpoint of Niel Herbert, a young man who has grown up in Sweet Water. He idealizes Mrs. Forrester, even as he witnesses her decline. As a contemporary edition of A Lost Lady concludes, “The recurrent conflict in Cather’s work, between frontier culture and an encroaching commercialism, is nowhere more powerfully articulated.”

A Lost Lady came out on the heels of One of Ours (1922), which, even though it disappointed critics for the most part, nevertheless won the Pulitzer Prize. It’s always fascinating to read reviews of novels that have achieved the status of a classic from when they first came out.

A Lost Lady mitigated the disappointment of One of Ours, restoring her to her well-earned place in the American literary canon. It’s always fascinating to read reviews of novels that have achieved the status of a classic from when they first came out. Here are two reviews that appeared in 1923:

A portrait of Marian Forrester

From the Detroit Free Press, October 14, 1923: To be sure, Willa Cather disappointed most of her admirers in One of Ours (1922), but to read My Antonia is to engrave Willa Cather’s with the names that endure. O Pioneers! has the same breadth and power, the same grasp of the pioneer theme, the same engaging simplicity, but it hasn’t the added interest of centering vividly around one character.

The setting for A Lost Lady is once again the raw west, though the date is later than in the earlier novels — after the railroads had gone through and the railroad aristocracy had developed, “men who had to do with the railroad itself, or with one of the land companies which were its by-products.

Miss Cather’s story centers on the Forrester home, which was one of those always open to officers of the road and their families traveling east and west through Sweet Water. Without these visitors, indeed, this side-tracked little village would have been desolate and dull enough:

“The house stood on a low round hill, nearly a mile from town; a white house with a wing, and sharp-sloping roofs to shed the snow. It was encircled by porches, too narrow for modern notions of comfort, supported by the fussy, fragile pillars of that time, when every honest stick of timber was tortured by the turning-lathe into something hideous.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: My Antonia by Willa Cather

. . . . . . . . . .

The story is incidental to the character of Marian Forrester, Captain Forrester’s young wife about whom the life of the house centered. Miss Cather’s ability in character revelation is amazing. In the simplest, most straightforward way, she tells you exactly what a person is like. Marian Forrester is charming, feminine, and potent.

To the town, she is a symbol of the elegance of a civilization vaguely felt to exist somewhere east of Sweet Water. To young Niel Herbert she represents all that is desirable in the outside world. Like Antonia, Marian Forrester will live vividly for you long after you have forgotten the details of her life.

You imagine for a time as you proceed with the story that Miss Cather is portraying the disintegration of character — another writer might have fallen into that error with Marian Forrester. Miss Cather has done a subtler, wiser thing in simply revealing strength and weakness as they are inextricably interwoven in the character of a lovely woman who prefers the fine to the vulgar, but who, left with “only the stage hands to listen,” draws them in to the charmed circle of her need.

She gives, with all her supports about her — influential husband, money — “the sense of tempered steel, a bade that could fence with anyone and never break.” When these supports are removed, it is evident that she has assailable points that her strength was drawn from without as well as from within. The Captain understood his wife better than she understood herself; and understanding her, he, in his own phrase, “valued her.”

It is only to Niel Herbert, from whose viewpoint the story is mostly told, that Marian Forrester is a “lost lady.”Beautiful women, whose beauty meant more than it said . . . was their brilliancy always fed by something coarse and concealed? Was that their secret?”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: 7 Later Novels by Willa Cather

. . . . . . . . . .

An unforgettable woman

From the Honolulu Star Bulletin, October 13, 1923: Miss Cather is primarily honest, and honesty means fearlessness. She is never so blinded by the compassion or proprietary pride to minimize in any way the faults of her characters, or to try to hide an unpleasant trait behind a virtue. Marian Forrester, the seductively charming heroine, is at times shown up in spotlights which reveal anything but beauty and nobility.

The book is primarily a character analysis of this strangely fascinating woman, the young and beautiful wife of an old railroad contractor living in the days that followed the extravagant period of development of the West.

There is a certain pathos in the story of Marian’s life. First, because she is tied down to a very much older man; again because, being surrounded by only the simple villagers, who must inevitably wear badly cut clothes, knobby toes on their toes on their shoes out of the room, she is isolated in her beauty and sophistication; and lastly, because she is pictured throughout through the wistful eyes of a youth, very much younger than herself, whose adoration lent her the asset of mystery and yet who understood her too well not to be sickened by her disintegration.

Marian was bewitching to the end, never admitting defeat until she was bowled over by it. She was an unforgettable sort of person, and in later years, after she passed out of his life, Niel Herbert was glad to have known her.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Lost Lady by Willa Cather on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post A Lost Lady by Willa Cather (1923) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 21, 2019

14 Women Who Have Won the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature has become the most prestigious literary prize. The Swedish literature prize has been awarded annually since 1901. It is given to an author from any country who, in the words of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, created “in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction.”

The Nobel Prize has been awarded to 853 men and only 51 women in all fields combined since its inception in 1895, 14 of whom achieved this honor in literature. Above right, Doris Lessing receiving her award in 2007.

The Swedish Academy decides who will receive the prize and announces the name of the laureate in early October. Authors can be awarded for individual works but the award recognizes and praises the talented author’s body of work as a whole. Listed below are women who have won the Nobel Prize in Literature in chronological order starting from the most recent.

. . . . . . . . . .

Svetlana Alexievich (2015)

Svetlana Alexandrovna Alexievich is an investigative journalist, essayist, and oral historian. She was born in 1948 in Ukraine and grew up in Belarus, where both of her parents were teachers. Her criticism of the political regimes in the Soviet Union forced her to live abroad in places like Germany, Italy, France, and Sweden.

Her work describes life after the Soviet Union through the eyes of individuals. She conducted numerous interviews in order to collect a wide range of voices. She was given the award “for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time.” She was also awarded the Order of the Badge of Honour, the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, and Prix Medicis.

Best known work: Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, 2013

. . . . . . . . . .

Alice Munro (2013)

Alice Munro was born in Wingham, Canada in 1931. She started writing as a teenager and ever since the late 1960s, she has dedicated herself to writing, specifically the short story genre. Growing up in Canada inspired the backdrops for her stories.

The underlying themes of her stories are usually relationship problems and moral conflicts. There is also a reoccurring theme of the relationship between memory and reality which she uses to create tension within her work. She is able to show the impact that small events can have on someone’s life. She won the Nobel Prize in Literature for being the “master of the contemporary short story.” In addition, she has also been awarded the Giller Prize, the Man Book International Prize, and more.

Best known work: Vintage Munro, 2004

. . . . . . . . . .

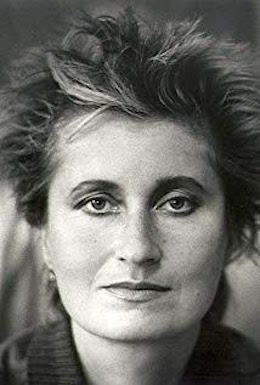

Herta Müller (2009)

Born in 1953 in Nitzkydorf, Banat, Romania, Herta Müller was a part of Romania’s small German-speaking population. Her vulnerable position during the communist regime affected her life and was portrayed in her writing.

Her literary works focus on her experiences as one of the few German speakers in Romania and tells her story about life under Ceausescu’s regime. She details images from her past as well as the terror and isolation from these events that have traumatized her and stayed in her mind. Muller’s Nobel Prize motivation was “who, with the concentration of poetry and the frankness of prose, depicts the landscape of the dispossessed.”

Best known work: The Passport, 1986

. . . . . . . . . .

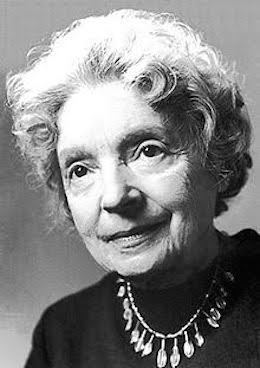

Doris Lessing (2007)

Doris Lessing was born in 1919 in Kermanshah, Persia (now Iran). Though she stopped attending school at the age of fourteen, she became a journalist and published a few short stories. After moving to London in 1949, she became involved in politics and social issues and was apart of the campaign against nuclear weapons.

Her work focuses on living conditions during the 20th century as well as behavioral patterns and historical developments at the time. Some of her work focuses on the future as she talks about civilization’s final hour in the eyes of an extraterrestrial watcher. The Academy described her work as “the epicist of the female experience, who with scepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilization to scrutiny.” She passed away in 2013 in London, United Kingdom.

Best known work: The Golden Notebook, 1962

. . . . . . . . . .

Elfriede Jelinek (2004)

Playwright and novelist Elfriede Jelinek was born in 1946 in Mürzzusihlag, Austria. Her works, such as The Piano Teacher and Lust, are characterized by their outspokenness and satirical sharpness. She developed a reputation of being a harsh critic of modern consumer society as she uncovers issues dealing with sexism, sadism, and submission and digs into the language to uncover it’s hidden ideologies.

Jelinek was awarded the prize “for her musical flow of voices and counter-voices in novels and plays that with extraordinary linguistic zeal reveal the absurdity of society’s cliches and their subjecting power.” In addition, she was also awarded the George Buchner Prize, the Franz Kafka Prize, and the Heinrich Heine Prize.

Best known work: The Piano Teacher, 1983

. . . . . . . . . .

Wisława Szymborska (1996)

Born in 1923, Maria Wislawa Anna Szymborska was well known in Poland for her poetic style containing wit, irony, and deceptive simplicity. She often focused on domestic details and occasions. During her lifetime, she wrote over fifteen books of poetry and was described by the Nobel committee as the “Mozart of poetry.”

Upon receiving the award, the Academy praised her “poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality.” Along with the Nobel Prize in Literature, she also received the Polish PEN Club Prize, the Goethe Prize, and the Herder Prize. She passed away in Poland on 2012.

Best known work: Dwukropek, 2005

. . . . . . . . . .

Toni Morrison (1993)

Toni Morrison was born Chloe Anthony Wofford in 1931, in Lorain, Ohio. Growing up, she developed a deep love and appreciation for black culture. Her works revolve around the dark side of being African-American and depict difficult circumstances. She reveals the individual lives and gives insight into her characters so that readers can have an understanding and empathize with them.

The American writer was recognized for her examination of the black experience within the black community. The Academy awarded her the Nobel Prize in Literature saying, “who in novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality.” She also won the Pulitzer Prize, Presidential Medal of Freedom, Coretta Scott King Award, and the National Book Critics’ Circle Award.

Best known work: The Bluest Eye, 1970

. . . . . . . . . .

Nadine Gordimer (1991)

Nadine Gordimer was born in South Africa in 1923. The short-story writer was exposed to reading at an early age. She quickly learned about the other side of the apartheid and focused her writing on racial issues in her native country. Her stories went into detail about how the apartheid on the lives of South Africans and the tension between personal isolation and the commitment to social justice.

As a result, there was strong political opposition towards the apartheid. Later on, though not an outstanding scholar herself, she lectured and taught at numerous schools during the 1960s and 70s. Afterward, she went on to publish several novels including The Conservationist (1974) and Burger’s Daughter (1979). She passed away in South Africa in 2014. Her prize motivation was “who through her magnificent epic writing has — in the words of Alfred Nobel — been of very great benefit to humanity.”

Best known work: The Conservationist, 1974

. . . . . . . . . .

Nelly Sachs (1966)

Nelly Sachs was born in 1891 in Berlin, Germany. Sachs experienced the Nazi persecution during the 20th century and was left with deep scars. This horrific event later became the basis for her writing as she described the trauma Jews faced during Nazi prosecution. She was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature with Israeli author, Shmuel Yosef Agnon.

While she acknowledged Agnon for representing Israel, she said “I represent the tragedy of the Jewish people.” In fact, she won the prize “for her outstanding lyrical and dramatic writing, which interprets Israel’s destiny with touching strength.” She passed away in 1970 in Stockholm, Sweden.

Best known work: Eli: A Mystery Play of the Sufferings of Israel, 1943

. . . . . . . . . .

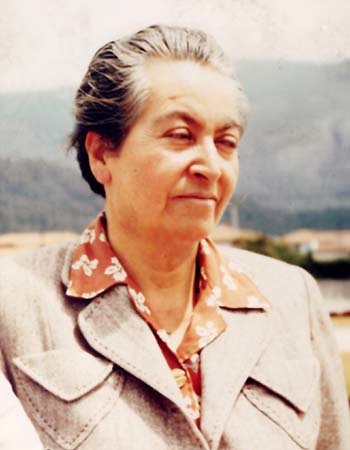

Gabriela Mistral (1945)

Lucila Godoy Alcayaga was born in 1889 in Vicuna, Chile. The Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral was the first Latin American woman to have won the Nobel prize. After the death of her lover, she was deeply distraught and used poetry to characterize her emotions which is when she wrote Sonetos de la muerte, three of which got published and earned her a national prize for poetry in 1914.

She was awarded “for her lyric poetry which, inspired by powerful emotions, has made her name a symbol of the idealistic aspirations of the entire Latin American world.” She was also given the title “Teacher of the Nation” in 1923 by her own government. She passed away in the Town of Hempstead, NY in 1957.

Best known work: Sonetos de la muerte, 1914

. . . . . . . . . .

Pearl S. Buck (1938)

Pearl S. Buck was born in Hillsboro, West Virginia in 1892. She spent much of her childhood in China, which is where most of her work is set. Her second novel that set the tone for her literary legacy, The Good Earth, received the Pulitzer Prize and Howells Medal in 1932. Today, it remains her best-known work and is a staple of high-school English curricula.

She was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “for her rich and truly epic descriptions of peasant life in China and for her biographical masterpieces.” Altogether, she’s written over seventy books and numerous articles and essays that were published in many well-known magazines. She passed away 1973 in Danby, Vermont.

Best known work: The Good Earth, 1931

. . . . . . . . . .

Sigrid Undset (1928)

Sigrid Undset was born in Denmark in 1882. The Norwegian writer wrote novels, short stories, and essays. At first, her writing was focused on strong women who were struggling to be liberated. This changed as her father, an archeologist, inspired her to write about the Middle Ages.

With the use of historical knowledge, deep psychological insight, a great imagination, and powerful language, Undset was able to bring both the communities and individuals to life. She was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1928 “principally for her powerful descriptions of Northern life during the Middle Ages.” She passed away in 1949 in Norway.

Best known work: Kristin Lavransdatter, 1920

. . . . . . . . . .

Grazia Deledda (1926)

Grazia Maria Cosima Damiana Deledda (commonly known as Grazia Deledda) was born in Nuoro, Italy in 1871. The Italian writer focused most of her writing on the people of her birthplace, Sardinia. Deledda wrote about themes such as love, pain, and death as many of her characters were social outcasts struggling with silence and isolation. As her childhood was shaped by old traditions and deep historical roots, she developed a strong belief in destiny.

Recurring themes, such as moral dilemmas, uncontrollable forces, and human weakness can also be seen in some of her writing. Deledda became the first Italian writer to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature 1926 and was awarded “for her idealistically inspired writings which with plastic clarity picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general”. She passed away in 1871 in Rome, Italy.

Best known work: La Madre, 1920

. . . . . . . . . .

Selma Lagerlöf (1909)

Selma Ottilia Lovisa Lagerlöf was born on 1858 in Marbacka, Sweden. The Swedish born writer was the first woman to ever win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Though she started writing poetry as a child, she didn’t publish anything until 1891 when she won a literary competition.

After several small works, she published Jerusalem in 1902. It was intended to be a primer for elementary schools but actually became one of the most delightful children’s books in any language. She was awarded the prize in 1909 for “in appreciation of the lofty idealism, vivid imagination and spiritual perception that characterize her writings.” She passed away in 1940 in her Marbacka, Sweden.

Best known work: The Wonderful Adventure of Nils, 1906

The post 14 Women Who Have Won the Nobel Prize in Literature appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 20, 2019

Remembering Meena Alexander, Indian Poet and Scholar

There are times when you take more interest in a poet or an author after you read her obituary. This is what happened with Meena Alexander, whom I had read in passing but devoured in great detail, especially after I heard that she had succumbed to cancer on November 21, 2018 in New York.

Meena could be termed an international poet as she was of Indian origins, born in Allahabad in 1951 and raised in Kerala, India before the family moved to Sudan.

Meena finally made the U.S. and New York City her home, where she was a professor of English and Women’s Studies at City University of New York and Hunter College. For five years in between, she also did teaching stints in various universities in India. Meena’s writings clearly reflect her life — migration, the trauma of moving places, and finally reconciliation.

Poetry collections, memoirs, and essays

As I write this tribute, I have Meena’s latest work of poetry Atmospheric Embroidery, in front of me. But she is equally renowned for her other volumes like Illiterate Heart, which won her the 2002 PEN Open Book Award and Raw Silk.

Her autobiographical memoir, Fault Lines, and her volume of poems and essays, The Shock of Arrival: Reflections on Post Colonial Experience, clearly bring out her feelings of angst. In the The Shock of Arrival, Meena wrote:

“The act of writing, it seems to me, makes up a shelter, allows space to what would otherwise be hidden, crossed out, mutilated. Sometimes writing can work toward a reparation, making a sheltering space for the mind. Yet it feeds off ruptures, tears in what might otherwise seem a seamless oppressive fabric.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Meena Alexander at Hyderabad Literary Festival, 2016

. . . . . . . . . .

One can term it a coming-home present to oneself, because interestingly, it was during her five-year stint as a Professor in India that Meena published her first three books of poetry, The Bird’s Bright Ring, I Root My Name, and Without Place. References to memory come up often in Meena’s writings and she observes, “In the poem, there is always that present moment, which is terribly important through which memory works.”

Besides the PEN award, Meena’s honors include grants and fellowships from the Guggenheim, Rockefeller, and Fulbright Foundations, National Council for Research on Women, and the South Asian Literary Association’s Distinguished Achievement Award in Literature, to name a few.

. . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: 10 Classic Indian Women Authors

. . . . . . . . . .

A sampling of poetry

The theme of displacement appears in myriad forms in Meena’s poetry. In the poem, “Udisthanam,” meaning base or foundation from the volume, “Atmospheric Embroidery,” she writes with near Biblical allusions:

Where are those refugees

Amma did not want me to see,

Gunny sacks and torn saris,

Stitched together with cord?

Breath of my breath, bone

Of my bone, dark god

Of the Nilgiris,

Who will grant them passage?

In another poem from the same collection called “Tarawad,” meaning home in her native language, Malayalam, Meena brings out the tragedy of leaving home thus,

Unseen umbilicus

That tethered me

Even as the ocean

Swept on and on.

Going, going, gone!

Someone banged the gavel,

Hearing the house was sold

She lay down in the mango grove

And stopped her eyes with stones,

Crazy girl, inconsolable!

Where is she now?

And the poem ends in sheer lyrical poesy…

What becomes of houses torn down?

In the room where she slept

Milk trickles

Syllables swarm, lacking a script

Door jambs stick to emptiness

Threshold split from walls.

Meena looks through a child’s eyes in a war-ravaged nation, in her Darfur poems, “Last Colours” and “There she stands,” where life and art seem to inspire each other:

In another country, in a tent under a tree,

A child sets paper to rock,

Picks up a crayon, draws a woman with a scarlet face,

Arms outstretched, body flung into blue.

The child draws an armored vehicle, guns sticking out

Purple flames, orange and yellow jabbing,

A bounty of crayons, a hut burst into glory.

How tragic it is for a child to see

On a cloud,

A child, arms splayed.

Beneath her, a field.

Red trees

With creatures clinging on —

Cat, dog, goat, mother, father too.

How are they all going to live?

Meena’s sensitive poetry pierces through these images to look straight into the heart of these children and their dreams and fears, which probably converge with her own childhood experiences of displacement.

But finally, Meena is able to make peace with migration and the acceptance of her many identities when she says in the “Poetics of Dislocation”: “And in terms of identity, surely one could argue versions of such a crisis have been with us for a very long time. There is nothing new in exile. It is as ancient as the notion of home.”

Given that Meena is no more with us physically, she might conclude that there is nothing like a permanent home on earth. Or maybe one can add a disclaimer that a poet or writer does live on, through her work.

Rest in peace, Meena.

Melanie P. Kumar is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

. . . . . . . . . .

Meena Alexander page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Meena Alexander

Meena Alexander biography on poets.org

RIP, Meena Alexander

Meena Alexander’s biography and complete works

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Remembering Meena Alexander, Indian Poet and Scholar appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 18, 2019

A Pilgrimage to Harper Lee’s Monroeville, Alabama, “Maycomb” of To Kill a Mockingbird

To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) by Harper Lee continues to be one of the most frequently taught novels in American high schools and is beloved by readers of all persuasions. The Pulitzer Prize-winning book has sold more than forty million copies and has been translated into some forty languages.

After a gap of fifty-six years, the 2016 publication of Go Set a Watchman set off a fervor of renewed interest in the famously private (though not, as myth would have it, reclusive) author.

No wonder, then, that Harper Lee’s hometown of Monroeville, Alabama, draws thousands of visitors each year who arrive to pay homage to her literary legacy. This small Southern town (population around 6,000) was the inspiration for Maycomb, where both books are set. The photo above right was snapped by Lee’s friend Michael Brown in 1957, the year she sold her manuscript, which had yet to be much edited.

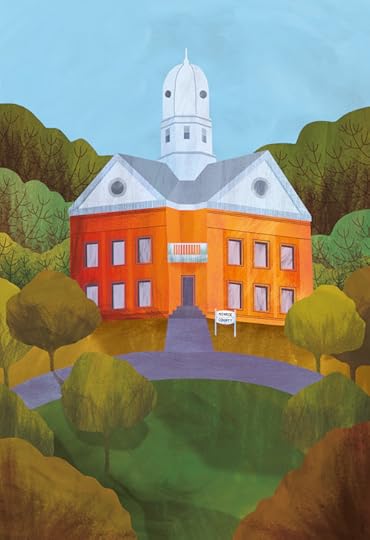

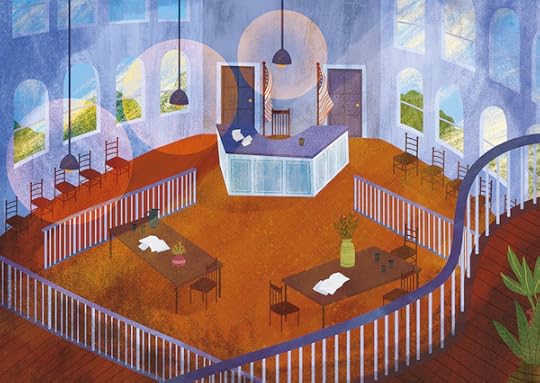

Image by Amy Grimes, from Literary Places

. . . . . . . . . . .

Literary Places (2019), written by Sarah Baxter and illustrated by Amy Grimes, explores twenty-five locales that are nearly as important to the narrative of certain novels as are the human characters. Think of the Paris of Les Miserables, the Yorkshire Moors of Wuthering Heights, and the Dublin of Ulysses, among others. None of those novels would be what they are without their settings, with their proverbial “sense of place.”

This is amply true for Harper Lee’s Monroeville, Alabama, which has come to symbolize not merely a typical Southern town in the early 20th-century, but of a particular mindset that America can’t seem to shake. That’s part of what, sadly, keeps Mockingbird relevant.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Harper Lee in the recreated courthouse in Monroeville; Getty Images

. . . . . . . . . . .

Here’s a portion of Sarah Baxter’s ode to Monroeville:

“No one’s in a hurry in this tired old town. Maybe it’s the heat – the Alabama summer is stultifying, sticky as molasses. It would be swell to swing on a porch all afternoon with an icy Coca-Cola. But this bench under the main square’s live oaks and magnolias will do just fine. Folk pass by, strolling between the Christian bookshop, the thrift store and the fine old County Courthouse, its white dome dazzling under the sun.

No case has been tried here for decades; indeed, its most famous case wasn’t tried here at all. But it remains a potent symbol of justice all the same … Harper Lee’s classic, To Kill a Mockingbird, delivered the right message in the right tone at the right moment. A simple tale of prejudice, unjustness and morality, it was published in 1960, just as the American South faced its biggest social shift since the Civil War.

The equality movement was gaining momentum; deeply entrenched attitudes to race and class were being challenged. Alabama saw some of the highest-profile acts. It was in Montgomery in 1955 that Rosa Parks refused to surrender her bus seat to a white passenger. In 1956, anti-integration riots erupted when Autherine Lucy and Polly Myers became the first African-American students to be admitted to the state’s university.”

(excerpted from Literary Places by Sarah Baxter ©2019, Quarto Publishing; reprinted by permission)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Image by Amy Grimes, from Literary Places

. . . . . . . . . . .

Monroeville has capitalized on the fame of its most famous resident and her hugely influential book, but it’s hard to quibble with the desire to do so. One of the highlights of a Harper Lee pilgrimage is the “To Kill a Mockingbird Experience” tour centered around the Old Courthouse Museum. It houses a courtroom re-created from the 1960 film starring Gregory Peck in his iconic role as Atticus Finch.

In the spring of each year, the first act of the theatrical version of Mockingbird is performed in an outdoor amphitheater behind the courtroom. Because of its limited annual run, tickets sell out very quickly, so if you consider going, order them well in advance.

In addition, the museum displays photographs and memorabilia of Harper Lee and Truman Capote, her childhood friend (and later her writing colleague and sometimes rival). Though a visit to Monroeville is tinged with commercialism, anything that extends the legacy of Lee’s novel, and the messages it delivers, can only be to the good.

As the entry in Literary Places concludes, “According to Atticus, ‘You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view … Until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it.’ Visiting Monroeville lets you walk a little with Harper Lee.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Literary Places by Sarah Baxter (author) and Amy Grimes (illustrator)

is available on Amazon and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Harper Lee’s Monroeville

The “To Kill a Mockingbird” Experience

What’s Changed, and What Hasn’t, in the Town That Inspired “To Kill a Mockingbird”

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post A Pilgrimage to Harper Lee’s Monroeville, Alabama, “Maycomb” of To Kill a Mockingbird appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 16, 2019

12 Classic Novels by Women Authors That Make Great Book Club Selections

Most often, book clubs (aka book groups) choose recent publications for discussion, many straight off the current bestseller list. And this is understandable, given all the great books coming out. It’s hard enough to keep up with all the new publications, but can we make the case for discussions of classic literature by women authors?

Some suggestions in this post are by authors of the past that are still well known, while others have fallen under the literary radar. Either way, these novels make for fantastic reading and stimulating discussion. Books remain classics for a reason, after all. With universal themes of what it means to be a woman — and what it means to be human — these great stories are timeless.

Has your book group read any great classic novels by women authors? If so, please comment below. For more ideas, see 12 Lesser Known Classic Women Novelists Worth Rediscovering, and more Themes and Tips for a Successful Book Club.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Awakening by Kate Chopin (1899)

This groundbreaking novella by Kate Chopin tells the story of a young mother who undergoes a dramatic period of change as she “awakens” to the restrictions of her traditional societal role and to her potential as a woman.

According to professor Sarah Wyman’s analysis of The Awakening, the book “came under immediate attack when published and was banned from bookstores and libraries. The author died virtually forgotten, yet The Awakening has been rediscovered and holds a secure and prominent position as a watershed text in U.S. literature and feminist studies.” We highly recommend this brief yet impactful book.

. . . . . . . . . .

My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin (1901)

My Brilliant Career was the first novel by Australian author Miles Franklin, written while she was still in her teens. The protagonist, Sybylla Melvyn, is an imaginative and tomboyish figure who is sent to live with her grandmother. She meets a man named Harold Beecham, whose attempts to court her are met with stubborn refusal. Sybilla is determined to become a writer. Will she ever achieve the “brilliant career” that she aspires to? Readers are left to ponder the possibility for themselves, for the story is open-ended.

This coming-of-age story is touching, funny, and sad, in turns. It’s a wonderful feminist novel by a talented writer who dedicated her life to women’s issues.

. . . . . . . . . .

My Antonia by Willa Cather (1918)

Willa Cather is truly one of the masters of American literature and ought to be read more, both by students and general readers who appreciate great writing. My Antonia one of several masterpieces from this writer’s pen.

Antonia is the daughter of an unhappy Bohemian immigrant, who brings his family to Nebraska to face the harsh conditions on the prairie. Antonia has an incredible talent for telling stories and a heroic capacity for love and resilience. She endures an unhappy marriage and has eleven children. A book that’s both beautiful and simple, it tells the story about a unique woman who is central to a giving community and its fascinating cast of characters.

. . . . . . . . . .

Show Boat by Edna Ferber (1926)