Nava Atlas's Blog, page 70

April 3, 2019

Jessie Tarbox Beals, America’s First Female Photojournalist

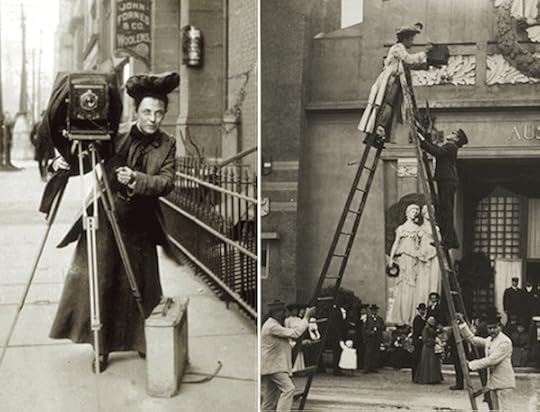

Though Jessie Tarbox Beals (1870 – 1942) wasn’t a literary figure, we’ve been highlighting pioneering female journalists here on Literary Ladies Guide, and she was a true trailblazer. Though she rarely contributed the texts to the news stories she took, she was a storyteller with her camera. As America’s first woman news photographer, she broke many barriers and encouraged other women to follow suit.

Jessie was the first woman to be hired as a staff photographer on a U.S. newspaper and the first American woman to get a byline as a photojournalist. She herself found nothing extraordinary about the pursuit, claiming that photography was a profession that could be mastered by any woman who “has good health, perseverance, and a nose for news.”

Enjoying a lavish childhood, losing everythingAs a young girl growing up in Ontario, Canada, in the 1870s, Jessie observed firsthand how fleeting success could be. Thanks to her father’s invention of a portable sewing machine, her family enjoyed a lavish lifestyle, complete with a mansion and beautiful gardens.

It all came crashing down when his patents expired, plunging his business into bankruptcy and driving him to drink. Jessie’s mother threw him out and found ways to support the family herself. Taking after her resourceful mother, Jessie earned a teaching certificate by age seventeen.

. . . . . . . . . .

This is the kind of camera Jessie used for much of her career.

This photo is from around 1905

. . . . . . . . . .

After a decade of teaching in Massachusetts, Jessie won a camera as a prize for selling magazine subscriptions. At first a hobby, photography became a passion. Jessie worked on her first professional assignment in 1899 when The Boston Post sent her to photograph the Massachusetts state prison. That same year, got her first credit byline for her photographs in the Windham County Reformer.

At age thirty, in 1900, she gave up teaching to pursue photography as a profession. By then, she’d married Alfred Tennyson Beals, moved to Buffalo, New York, and set up a portrait studio. In a rare reversal of roles, her husband was her assistant, doing much of the darkroom work. Jessie taught Alfred the basics of photography.

. . . . . . . . . .

One of Jessie Tarbox Beals’ most famous photos,

depicting President Theodore Roosevelt (front left)

. . . . . . . . . .

Being a successful female portrait photographer in the early 1900s was quite a feat. And when she was hired as a full-time news photographer for Buffalo’s two newspapers in 1902, it was an unheard of profession for women. That’s when she cemented her legacy as America’s first female photojournalist.

But none of this was enough for restless Jessie. In 1905, she moved to New York City, determined to become a news photographer in America’s biggest city. But no newspaper would hire a woman, so once again, she open a portrait studio as a way to make a living.

Street child photo by Jessie Tarbox Beals, a series she became known for

. . . . . . . . . .

It wasn’t for nothing that Jessie was called “aggressive” and a “daredevil,” though neither were meant as compliments. Not willing to give up, she took photos she found newsworthy, printed them, and sold them newspaper editors. Afterwards, reporters would be assigned to write up the stories to go with them. Freelancing in this unique way helped her gain a reputation.

In 1905 Jessie opened her own photo studio on Sixth Avenue in New York City. At the same time, she took whatever assignments came her way, from capturing the burgeoning Bohemian atmosphere of Greenwich Village to her signature photos of the inhabitants of the city’s slums. She also did portraits of presidents (Coolidge, Hoover, and Taft) and literary figures including Edna St. Vincent Millay and Mark Twain.

In 1911, Jessie had a daughter, Nanette, who was frail from the effects of rheumatoid arthritis. She was the apple of her mother’s eye. Jessie and Alfred, who may not have been Nanette’s father, often lived apart and eventually divorced in 1917.

One of her best-known photo essays, featured in the The New York Times in 1913, documented the poor living conditions of immigrant families.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Photojournalism was a demanding, risky profession — as it still remains. But nothing, not even hauling around a box camera weighing fifty pounds wearing full skirts and big hats got in the way of Jessie’s determination to get the best angles for her photos. She climbed ladders and bookcases, and even jumped into hot air balloons.

Her first major “climb” was perching at the top of a bookcase to get shots of a 1903 murder trial through a transom window. Photographers were barred from the courtroom, so Jessie’s photos became exclusive.

. . . . . . . . . .

She became known for documenting living conditions of the poor

. . . . . . . . . .

A full career with some misstepsJessie took every assignment that came her way — news events, celebrity and political portraits, even homes and gardens. She loved to work and needed to make a living. In hindsight, she came to regret her versatility, which made her work harder to recognize and to become known for.

By the 1920s, she was no longer as much of a novelty as a woman photographer. Others, like Dorothea Lange and Margaret Bourke-White were coming up fast behind her. Jessie tried to stay afloat by becoming a public speaker and shifted her focus to giving public talks and specializing in photographing suburban gardens and the estates of the wealthy.

In the late 1920s, she and Nanette moved to Hollywood to ply her trade, but returned to New York City in 1933 — the depths of the depression. Things went downhill from there. Jessie neglected to save money for her later years. Like her father, she lived too lavishly, and sadly, ended up destitute when she could no longer work.

Legacy

As America’s first female news photographer, Jessie Tarbox Beals is considered one of the pioneers of the photo essay — a series of photos with captions to document newsworthy subjects. Jessie didn’t write, but she thought like a reporter, which was why she was able to sell photos before a single word of a news story had been written. Her example encouraged other women to pursue professional photography.

Though Jessie made mistakes, but they don’t diminish her accomplishments. To become America’s first female photojournalist, she refused to let gender be a barrier. She took pride in crafting excellent photographs and used her moxie to get them into major publications. Most admirably of all, she created her own opportunities, rather than waiting for men to give her permission.

The archives of Jessie Tarbox Beals are now housed at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College in Massachusetts. The papers and photographs were gift by her daughter Nanette in 1982, long after Jessie’s death in 1942 at the age of seventy-one.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“Newspaper photography as a vocation for women is somewhat of an innovation, but is one that offers great inducements in the way of interest as well as profit. If one is the possessor of health and strength, a good news instinct … and the ability to hustle, which is the most necessary qualification, one can be a news photographer.” — From an interview in The Focus, St. Louis, Missouri, 1904

More about Jessie Tarbox Beals

Wikipedia First Behind the Camera, photojournalist Jessie Tarbox Beals Women photojournalists at the Library of CongressThe post Jessie Tarbox Beals, America’s First Female Photojournalist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 2, 2019

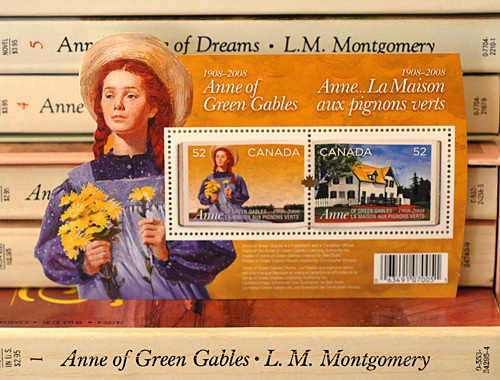

Quotes from Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery

Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery (1874 – 1942) has been a classic children’s novel almost from the time it was first published in 1908. It’s the first of a series of novels detailing the adventures of an orphan girl named Anne Shirley from the age of eleven through adulthood.

Anne is mistakenly sent to two siblings, Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert interested in adopting a boy to help them on their farm. The novel takes place in the fictional town of Avonlea on Prince Edward Island and follows Anne as she makes her way through life with the Cuthbert siblings, school friends, and townspeople.

Since the year of its publication, Anne of Green Gables has sold more than fifty million copies and has been translated into thirty-six languages as well. Montgomery wrote numerous sequels and since her death, another sequel has been published as well as an authorized prequel — Marilla of Green Gables. In addition, the novel has been adapted into films, television shows, and a live-action and animated television series. Musicals and plays have also been created and are produced annually in Japan and Europe.

Anne of Green Gables has captured the hearts of many all over the world, and has been honored universally. A “Green Gables” building has been named in Australia, Canada Post issued Anne of Green Gables-inspired stamps, and curiously, the Anne franchise has a devoted following in Japan. Here is a selection of quotes from Anne of Green Gables, the beloved classic novel:

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“There’s such a lot of different Annes in me. I sometimes think that is why I’m such a troublesome person. If I was just the one Anne it would be ever so much more comfortable, but then it wouldn’t be half so interesting.”

“Oh, it’s delightful to have ambitions. I’m so glad I have such a lot. And there never seems to be an end to them– that’s the best of it. Just as soon as you attain to one ambition you see another one glittering higher up still. It does make life so interesting.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Because when you are imagining, you might as well imagine something worth.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Isn’t it splendid to think of all the things there are to find out about? It just makes me feel glad to be alive–it’s such an interesting world. It wouldn’t be half so interesting if we know all about everything, would it? There’d be no scope for imagination then, would there? But am I talking too much? People are always telling me I do. Would you rather I didn’t talk? If you say so I’ll stop. I can STOP when I make up my mind to it, although it’s difficult.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It’s delightful when your imaginations come true, isn’t it?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“We pay a price for everything we get or take in this world; and although ambitions are well worth having, they are not to be cheaply won, but exact their dues of work and self-denial, anxiety and discouragement.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Witty and Wise Quotes from L.M. Montgomery’s Novels

. . . . . . . . . .

“That’s the worst of growing up, and I’m beginning to realize it. The things you wanted so much when you were a child don’t seem half so wonderful to you when you get them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Next to trying and winning, the best thing is trying and failing.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I wouldn’t want to marry anybody who was wicked, but I think I’d like it if he could be wicked and wouldn’t.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“You’re never safe from being surprised until you’re dead.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’ve just been imagining that it was really me you wanted after all and that I was to stay here forever and ever. It was a great comfort while it lasted. But the worst of imagining things is that the time comes when you have to stop and that hurts.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Tomorrow is always fresh with no mistakes in it…well with no mistakes in it yet.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Life is worth living as long as there’s a laugh in it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Kindred spirits are not so scarce as I used to think. It’s splendid to find out there are so many of them in the world.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It’s been my experience that you can nearly always enjoy things if you make up your mind firmly that you will.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“Don’t you just love poetry that gives you a crinkly feeling up and down your back?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Look at that sea, girls–all silver and shadow and vision of things not seen. We couldn’t enjoy its loveliness any more if we had millions of dollars and ropes of diamonds.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It’s all very well to read about sorrows and imagine yourself living through them heroically, but it’s not so nice when you really come to have them, is it?”

. . . . . . . . . .

The world looks like something God had imagined for his own pleasure, doesn’t it?

. . . . . . . . . .

“Why must people kneel down to pray? If I really wanted to pray I’ll tell you what I’d do. I’d go out into a great big field all alone or in the deep, deep woods and I’d look up into the sky—up—up—up—into that lovely blue sky that looks as if there was no end to its blueness. And then I’d just feel a prayer.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Anne of Green Gables and its sequels on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“Which would you rather be if you had the choice–divinely beautiful or dazzlingly clever or angelically good?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Pretty? Oh, pretty doesn’t seem the right word to use. Nor beautiful, either. They don’t go far enough. Oh, it was wonderful—wonderful. It’s the first thing I ever saw that couldn’t be improved upon by imagination. It just satisfied me here”—she put one hand on her breast—”it made a queer funny ache and yet it was a pleasant ache.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 1, 2019

America Day by Day by Simone de Beauvoir

In January of 1947, Simone de Beauvoir, existentialist philosopher, novelist, and author of feminist classic The Second Sex, landed at La Guardia airport. From there she embarked on a months-long journey from one end of the U.S. to the other. Immersing herself in American culture, customs, and vistas, she kept a detailed diary that was published in France in 1948. It was first published in an American edition in 1954.

The University of California Press published a more recent edition in 1999, describing it as “one of the most intimate, warm, and compulsively readable texts from the great writer’s pen.” The publisher’s description continued:

“Fascinating passages are devoted to Hollywood, the Grand Canyon, New Orleans, Las Vegas, and San Antonio. We see de Beauvoir gambling in a Reno casino, smoking her first marijuana cigarette in the Plaza Hotel, donning rain gear to view Niagara Falls, lecturing at Vassar College, and learning firsthand about the Chicago underworld of morphine addicts and petty thieves with her lover Nelson Algren as her guide.

This fresh, faithful translation superbly captures the essence of Simone de Beauvoir’s distinctive voice. It demonstrates once again why she is one of the most profound, original, and influential writers and thinkers of the twentieth century.”

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir

. . . . . . . . . .

How much of the American cultural landscape has changed since Simone de Beauvoir observed it in 1947? Doubtless, this is a fascinating read. Here is how one reviewer saw her efforts when the book first appeared in the U.S.:

Visitor From France Found Much to Dislike in U.S.A.From the original review by Helen K. Fairall in the Des Moines Register, January 10, 1954, of America Day by Day by Simone de Beauvoir:

It was bound to happen — that a vocal Frenchwoman would turn the tables (and not the other cheek) on the many critical American women who have “done” France to a crisp after they returned to the U.S. Simone de Beauvoir is an extremely thoughtful observer but she has her phobias.

She came to New York, then covered the United States by train, plane, bus, and automobiles belonging to friends who she contacted wherever she stopped.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: Philosophical Quotes by Simone de Beauvoir

. . . . . . . . . .

Chicago to her was the most depressing city, with its lake front a false facade to hide its miseries. Paradoxically she found Chicago, as well as New York, to be “the most stimulating” cities.

The colleges and universities she visited were failing to develop thinkers, in her view. In the students she found apathy toward world problems, an unawareness of future responsibilities, and ignorance of Europe’s complexities.

The hundreds of towns strung across the country were all alike — but with different names — until she reached California.

Observed hatreds

The sunshine, dust, and noise of Los Angeles had the ugliness of a Paris fair and the traffic was frightening, apparently not recalling to her the traffic jams and speed in Paris.

Texas opened her eyes to the “hatreds of the South” which she found from there to Charleston. New Orleans, with its legendary beauty, she knew to be “one of the most wretched cities in America — its stagnant luxury ambiguous.”

American drugstores fascinated her. They embraced all the bizarre qualities of the general stores of the pioneer west. The opulence of the overheated hotels crushed her.

. . . . . . . . . .

America Day by Day on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

The good will and helpfulness of the people attracted yet irritated Simone de Beauvoir. They identified virtue with prosperity and loved to impose upon others all that was good. What distressed her most was the average American’s inclination to seek the source of valued “in things, not in themselves.”

Some of her criticism is valid. Her observations on the cities and the ways of American life are pointed. What this reviewer objects to is her use of a personal bias to exploit controversial American problems. Perhaps a continental understands them as poorly as Americans understand French politics.

Quotes from America Day by Day

“There’s something in the New York air that makes sleep useless.”

. . . . . . . . . .

” … Americans love speed, alcohol, film thrills and sensational news. They feverishly demand something more and, again, something more, never able to quell their restlessness. Yet here, as everywhere else, life repeats itself day after day, so people amuse themselves with gadgets, and lacking real projects, they cultivate hobbies.

These manias allow them to pretend to take responsibility, by choice, for their daily habits. Sports, movies, and comics all offer distractions. But in the end, people are always faced with what they wanted to escape: the arid basis of American life—boredom.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I hope I am not fated to live in Rochester.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“[Americans] respect the past, but as an embalmed monument; the idea of a living past integrated with the present is alien to them. They want to know only a present that’s cut off from the flow of time, and the future they project is one that can be mechanically deduced from it, not one whose slow ripening or abrupt explosion implies unpredictable risks.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post America Day by Day by Simone de Beauvoir appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 31, 2019

The Song of the Lark by Willa Cather (1915)

The Song of the Lark by Willa Cather, published in 1915, was the third of her twelve novels. It traces the artistic growth of Thea Kronberg, the novel’s heroine, from her hometown in the desert of Colorado to the stage of New York’s Metropolitan Opera House. Though Cather herself didn’t follow the path of a performer, some of the elements of the novel are autobiographical, mirroring the trajectory from an early life in a pioneering region to one of creative fulfillment as a woman.

Thea Kronborg has a dream of becoming a world-class singer. Born into the family of a Swedish Methodist minister in the Colorado village of moonstone, she has a beautiful voice, a driving ambition, and an innate sense of what is true and fine. She sees the surroundings in which she is growing up in as cheap and tawdry, though it’s a part of the booming American West.

The novel’s trajectory follows Thea from her girlhood, when her ambition takes root, to her becoming a prima donna at the age of thirty. Thea’s sole focus is on her aspiration to artistic perfection. Her passion and desire for artistic achievement color everything in her life.

The fictional Thea’s professional achievements were inspired by the real-life career of the Wagnerian soprano Olive Fremstad. In 1913, Willa Cather was assigned to write an article for McClure’s magazine about three American opera singers, Louise Homer, Geraldine Farrar, and Olive Fremstad.

Willa had already been planning to write a book about an opera singer, and it was fortuitous that she got to meet the three singers for her interviews. Of the three women, it was Fremstad who interested her most, and she zeroed in on trying to discern what it had taken from the Swedish Fremstad to become a true artist.

. . . . . . . . . .

Willa Cather’s inspiration for The Song of the Lark, Olive Fremstad

. . . . . . . . .

Penguin Random House’s Readers Guide encapsulates the novel: “The Song of the Lark is the story of an artist’s growth and development from childhood to maturity. More particularly—and decidedly more rarely—it traces the development of a female artist supported by a series of male characters willing to serve her career. Inspired by Willa Cather’s own development as a novelist and by the career of an opera diva, The Song of the Lark examines the themes of the artist’s relationship with family and society, themes that would dominate all of Cather’s best fiction.”

An original 1915 review of Song of the Lark

From the original review in The State Journal, Raleigh, NC, December, 1915: Willa Cather‘s The Song of the Lark is a book which merits more than ordinary notice. The story is easy to summarize, because it is so simple, so entirely the story of the development of a single personality.

Thea Kronborg, born into the family of a Swedish Methodist minister in a Colorado village, has a voice, an ambition, and a native sense of the true and fine — qualities all in contrast with the cheapness and tawdriness about her.

Two or three childhood friends who have faith in her suffice to fix her determination. From the time in her early girlhood, when her ambition takes definite form, to her triumph as a prima donna at thirty, her whole life is moulded by her supreme desired for artistic perfection.

Obstacles to overcomeShe has the help of a few sympathetic friends; but she also has oppressive discouragements — her own crudeness and ignorance, criticism and lack of understanding on the part of her family, poverty, and, perhaps worst of all, the cheap success around her, the eclat of superficial art, of voices without brains or artistic feeling behind them.

Through it all she clings to her ideal, and in the end has the satisfaction of winning not only the recognition of the larger public, but also the unstinted praise of the few who really know and understand her and her ideal.

. . . . . . . . . .

Song of the Lark on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

The story has its blemishes. The characterization is sometimes labored; the concluding section is too long-drawn-out; the duplicity of Thea’s lover is inconsistent and has the effect of an artificial device.

But these are faults that are easily forgiven in consideration of the story’s merits: its seriousness and utter sincerity, its painstaking workmanship, its large free pictures of the Western plains and the Arizona canyons, the simplicity and restraint with which the more emotional parts are handled.

The faults are of the kind that can be overcome; the merits are of the kind that make fine things in fiction.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Novels of Willa Cather, Master of American Literature

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from The Song of the Lark“Nothing is far and nothing is near, if one desires. The world is little, people are little, human life is little. There is only one big thing—desire. And before it, when it is big, all is little.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Her secret? It is every artist’s secret — passion. That is all. It is an open secret, and perfectly safe.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I only want impossible things,” she said roughly. “The others don’t interest me.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Artistic growth is, more than it is anything else, a refining of the sense of truthfulness. The stupid believe that to be truthful is easy; only the artist, the great artist, knows how difficult it is.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“People live through such pain only once. Pain comes again—but it finds a tougher surface.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There are some things you learn best in calm, and some in storm.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The world is little, people are little, human life is little. There is only one big thing — desire.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Song of the Lark by Willa Cather (1915) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 30, 2019

Angela Carter

Angela Carter (May 7, 1940– February 16, 1992), born Angela Olive Stalker, was an English novelist, short story writer, and journalist. Born in Eastbourne, England. She became known as one of Britain’s most original writers, best known for her eclectic range of themes and genres.

Her varied influences included fairy tales, gothic fantasy, Shakespeare, Surrealism, and the cinema of Godard and Fellini. Her work breaks taboo, often being labeled provocative. She was also a strong believer in women having control over their own narrative. She is perhaps best known for The Bloody Chamber (1979), which is a type of re-envisioned version of the classic European fairy tales.

Early LifeCarter was born to a journalist father, Hugh Alexander Stalker, and mother, Olive, who worked as a cashier at a local grocery store. Both parents spoiled her to no end. She was gifted with treats, kittens, and storybooks. Her mother never put her to bed until after midnight, when her father got back from work. Her father brought her long rolls of white paper from his office, and while her parents chatted she wrote stories in crayon.

She spent much of her childhood with her grandmother in Yorkshire, where she was sent to escape the dangerous wartime bombings. After the war, she attended school in Balham, South London. Here she frequently went on trips with her father to the Granada Cinema in Tooting, which started her life-long love of the cinema and film.

After leaving school she worked at the Croydon Advertiser for a short time, before she joined her soon-to-be husband Paul Carter in 1960. After her marriage, she moved to Bristol where she studied English with a specialization in medieval literature at Bristol University.

Carter divorced in 1974 due to Paul’s numerous battles with depression. Soon after, she settled back in south London again and got together with Mark Pearce. In 1983, she had a son named Alexander with Pearce. During the late 1970s and 80s, Carter taught at a number of universities; including Sheffield and East Anglia in Britain, Brown University in the U.S., and the University of Adelaide in Australia.

. . . . . . . . . .

Memorable Quotes by Angela Carter from Her Literary Works

. . . . . . . . . .

Carter published over two dozen pieces of literature in her lifetime. Her first novel, Shadow Dance was published in 1966 and introduced Carter’s most enigmatic characters, Honeybuzzard. After the publication of this novel, she was immediately recognized as one of Britain’s most original writers. The novel tells the tale of seducing and tormenting lovers, enemies, and friends in the back-streets of London, leaving behind a trail of broken hearts, dashed hopes, and destruction.

Her second novel, The Magic Toyshop, followed shortly after in 1967. And her third, Several Perceptions, was published in 1968. She won the Somerset Maugham award for these two, which followed themes of gothic fantasy and horror, touched with the libertine energy of the 1960s.

Carter went on to publish six more novels, four collections of short stories, a book of essays, two collections of journalism, and a volume of radio plays.

A condition of the Somerset Maugham award was that it was to be used for foreign travel. And so in 1969, Carter traveled to Japan, where she immersed herself in the Japanese culture. She wrote some of her most powerful essays during her time in Japan.

Her experiences in Japan inspired her collection of semi-autobiographical short stories such as Fireworks, Heroes and Villains, The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman, and The Passion of New Eve. Her novel, Nights at the Circus, won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. In 2012 that novel was declared the best book to have ever been awarded that prize.

Carter went on to publish nine novels in total, four collections of short stories, a book of essays, two collections of journalism, and a volume of radio plays. She also went on to write the screenplay for 1984 film The Company of Wolves, based on one of her most famous short stories.

. . . . . . . . . .

Angela Carter, 1976; photograph by Fay Godwin © British Library Board

. . . . . . . . . .

Life After DeathAngela Carter died at home in 1992 after her battle with lung cancer. After her untimely death at age fifty-one, there was a notable increase of interest in her work. There was a rapid increase in sales of her books and her stage adaptations of her work both in Britain and abroad.

Carter quickly became one of the most widely taught and researched writers in all of British fiction. Her writing has been described as occupying a unique place in twentieth-century fiction — one where myths about sexuality and gender are proven wrong, and where there’s no limit to the human imagination. In 2008, The Times of London ranked Carter tenth on their list of the 50 greatest British writers since 1945.

. . . . . . . . . .

Angela Carter page on Amazon

More about Angela Carter on this site

Memorable Quotes by Angela Carter from Her Literary WorksMajor works

Though Angela Carter was only fifty-one when she died, she left a large body of work. In addition to the novels, short stories, and nonfiction listed below, she also published three collections of poems, several plays and screenplays, and four children’s books. For a compete listing of her works, see this section of her Wikipedia page.

Novels

Shadow Dance (1966, aka Honeybuzzard)The Magic Toyshop (1967)Several Perceptions (1968)Heroes and Villains (1969)Love (1971)The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman (1972)The Passion of New Eve (1977)Nights at the Circus (1984)Wise Children (1991)Short stories and nonfiction

Fireworks: Nine Profane Pieces (1974)The Bloody Chamber (1979)Black Venus (1985; Saints and Strangers in the U.S.)The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography (1979)Nothing Sacred: Selected Writings (1982)Expletives Deleted: Selected Writings (1992)Biographies

The Invention of Angela Carter by Edmund Gordon (2017)Inside the Bloody Chamber: Aspects of Angela Carter by Christopher Frayling (2015)More information

Wikipedia Reader discussion of Angela Carter’s books on Goodreads Angela Carter bio at The British Library

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Angela Carter appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 29, 2019

Memorable Quotes by Angela Carter from Her Literary Works

Angela Carter (1940-1992), born Angela Olive Stalker, was an English novelist, short story writer, and journalist. Known as one of Britain’s most original writers, she was best known for her eclectic range of themes and influences. Her work breaks taboo, often being labeled provocative.

Carter was a strong believer in women having control over their own narrative. Most famous for her 1979 novel The Bloody Chamber, a reenvisioned version of the classic European fairy tales. She went on to publish dozens of literary works. Here are memorable quotes by Angela Carter from her novels and other literary works:

The Bloody Chamber

“She herself is a haunted house. She does not possess herself; her ancestors sometimes come and peer out of the windows of her eyes and that is very frightening.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Those are the voices of my brothers, darling; I love the company of wolves.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Anticipation is the greater part of pleasure.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There is a striking resemblance between the act of love and the ministrations of a torturer.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Love is desire sustained by unfulfillment.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“For all cats have this particularity, each and every one, from the meanest alley sneaker to the proudest, whitest she that ever graced a pontiff’s pillow—we have our smiles, as it were, painted on. Those small, cool, quite Mona Lisa smiles that smile we must, no matter whether it’s been fun or it’s been not. So all cats have a politician’s air; we smile and smile and so they think we’re villains.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Like the wild beasts, she lives without a future. She inhabits only the present tense, a fugue of the continuous, a world of sensual immediacy as without hope as it is without despair.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The girl burst out laughing; she knew she was nobody’s meat.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman

. . . . . . . . . .

“I desire therefore I exist.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Some cities are women and must be loved; others are men and can only be admired or bargained with.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Love is the synthesis of dream and actuality; love is the only matrix of the unprecedented; love is the tree which buds lovers like roses.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Nights at the Circus

. . . . . . . . . .

“We must all make do with the rags of love we find flapping on the scarecrow of humanity.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Despair is the constant companion of the clown.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Out of the frying pan into the fire! What is marriage but prostitution to one man instead of many? No different!”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Sadeian Woman

. . . . . . . . . .

“A free woman in an unfree society will be a monster.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If women allow themselves to be consoled for their culturally determined lack of access to the modes of intellectual debate by the invocation of hypothetical great goddesses, they are simply flattering themselves into submission (a technique often used on them by men). All the mythic versions of women, from the myth of the redeeming purity of the virgin to that of the healing, reconciliatory mother, are consolatory nonsenses; and consolatory nonsense seems to me a fair definition of myth, anyway. Mother goddesses are just as silly a notion as father gods. If a revival of the myths gives women emotional satisfaction, it does so at the price of obscuring the real conditions of life. This is why they were invented in the first place.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To be the object of desire is to be defined in the passive case. To exist in the passive case is to die in the passive case—that is, to be killed. This is the moral of the fairy tale about the perfect woman.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“In his diabolic solitude, only the possibility of love could awake the libertine to perfect, immaculate terror. It is in this holy terror of love that we find, in both men and women themselves, the source of all opposition to the emancipation of women.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“In a world where women are commodities, a woman who refuses to sell herself will have the thing she refuses to sell taken away from her by force.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Wise Children

. . . . . . . . . .

“Hope for the best, expect the worst.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He was a lovely man in many ways. But he kept on insisting on forgiving me when there was nothing to forgive.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A mother is always a mother, since a mother is a biological fact, whilst a father is a movable feast.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Our fingernails match our toenails, match our lipstick match our rouge…The habit of applying warpaint outlasts the battle.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Wayward Girls and Wicked Women

. . . . . . . . . .

“She was no malleable, since frigid, substance upon which desires might be executed; she was not a true prostitute for she was the object on which men prostituted themselves.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“To be a wayward girl usually has something to do with premarital sex; to be a wicked woman has something to do with adultery. This means it is far easier for a woman to lead a blameless life than it is for a man; all she has to do is to avoid sexual intercourse like the plague. What hypocrisy!”

. . . . . . . . . .

Other Sayings and Quotes“Proposition one: time is a man, space is a woman.” –The Passion of New Eve

. . . . . . . . . .

“She was like a piano in a country where everyone has had their hands cut off.” –Saints and Strangers

. . . . . . . . . .

“Reading a book is like re-writing it for yourself. You bring to a novel, anything you read, all your experience of the world. You bring your history and you read it in your own terms.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Cities have sexes: London is a man, Paris a woman, and New York a well-adjusted transsexual.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Is not this world an illusion? And yet it fools everybody.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“For most of human history, ‘literature,’ both fiction and poetry, has been narrated, not written—heard, not read. So fairy tales, folk tales, stories from the oral tradition, are all of them the most vital connection we have with the imaginations of the ordinary men and women whose labor created our world.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Language is power, life and the instrument of culture, the instrument of domination and liberation.”

The post Memorable Quotes by Angela Carter from Her Literary Works appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

The Woman Destroyed by Simone de Beauvoir

Simone de Beauvoir (1908 – 1986) French author, existential philosopher, political activist, and feminist was best known for The Second Sex (1949). But she also put her social theories, especially those pertaining to affairs of the heart, into several works of fiction. The Woman Destroyed, published first in French in 1967 (as La Femme Rompue) presents a trio of novellas, or long short stories.

Upon the book’s 1969 publication in English, The Sunday Herald Times (London) wrote: “In three immensely intelligent stories about the decay of passion, Simone de Beauvoir draws us into the lives of three women, all past their first youth, all facing unexpected crises … suffused with de Beauvoir’s remarkable insights into women, The Woman Destroyed gives us a legendary writer at her best.”

. . . . . . . . .

See also: The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir

. . . . . . . . .

ThoughThe Woman Destroyed was generally praised, not all reviewers were as enthusiastic as the one above. Following is a review of the American edition that, though critical of the book’s tone, nonetheless offers a succinct synopsis of each story:

The Woman Destroyed: Three Women in Crisis

From a review by Inna Uhlig of The Woman Destroyed by Simone de Beauvoir in The Baltimore Sun, March 23, 1969: In this English translation of La Femme Rompue, Simone de Beauvoir presents three novellas, or long short stories, that describe women over forty, each delving into her own unhappiness:

The Age of Discretion

In “The Age of Discretion,” the woman is faced with a young married son who suddenly tears himself free from her sphere of influence. She rejects him completely, refusing to see him. At the same time, she observes that she no longer seems to bring her husband any kind of happiness. She and he are not in accord over her treatment of their son.

As her marital relationship shifts into a different key, she and her spouse grow father and farther apart. At the end there is a suggestion of a new plateau of understanding, but it’s not convincing because non of the problems have been resolved.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Simone de Beauvoir

. . . . . . . . . .

The Monologue

In the middle tale, the tone is strident, the pitch continuously noisy, rising over and over again to a hysterical note. “The silly bastards!” the woman cries at the first gasp. Her accusing, despairing monologue goes on and on about the ghastly mess in which she is drowning: a woman separated from her child and “ditched” by his “swine of a father.”

She screams how she is rotting all alone, how she is being trampled underfoot. She moans that she is “bored through the ground,” alone on New Year’s Eve.

And then, there is the memory of her daughter, dead by her own hand at fifteen. She vows she would have made that daughter into a fine girl, asking nothing, only giving. When they buried their daughter, she cries out that they really buried her. The woman gives one scream after another of rage and despair and loneliness, until there is more than enough.

The Woman Destroyed

The title story, “The Woman Destroyed,” is told in a more modified tone; but the undercurrent of despair builds to uncontrolled proportions. In this monologue, the woman tells of a comfortable life that is being washed away by her husband’s affair with another woman.

The woman telling her story has two grown daughters, one of whom is married and the other pursuing an independent career in the United States. Now, as her unhappiness builds, she even questions her upbringing of her daughters.

Alone with her husband, she gradually becomes aware of his concealments and actual lies that hide the fact that he is not really “eaten up by his profession”

Running from friend to friend, the wife becomes less and less sure of herself as she allows her husband to share his life with the other woman. Where everything had been secure and tidy, suddenly everything is disintegrating.

Having devoted her whole self to her family, the wife fines herself faced with an utterly abandoned life. she is playing a losing game.

This reviewer’s conclusion

Each of these novellas is concerned with a desperately unhappy, no-longer-young woman whose life is going down the drain. Three such monologues, in succession, are an overdose. At the same time, none of the husbands or other characters in any of the stories take on a convincing life of their own.

What we have are three female voices, one louder and more strident than the other, but all disconcerting. None of them throw any real light upon the melancholy situations complained about.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Woman Destroyed on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Though the reviewer above gives helpfully neat synopses of these stories, it’s evident that the she found the characters distasteful. Scanning recent reader reviews, contemporary readers find much in this book that resonates.

On the book’s discussion page on Goodreads, one reader notes, “Reading The Woman Destroyed, I was reminded that all great writing is a warning, or at the very least, veiled advice on how one might attempt to live a meaningful life.” Another writes, “Her characters make sense of life on the page and when they discover the why in the actions of others, the reader is invited along for the journey.”

Despite the brevity of the book, many readers, both female and male, leave long, thoughtful musings on how the book has resonated with them. It could be that Simone de Beauvoir was tapping into a fictional form of confessional angst that was a bit before its time, and that has aged well.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Woman Destroyed by Simone de Beauvoir appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 28, 2019

Julia de Burgos

Julia de Burgos, born Julia Constanza Burgos Garcia (February 17, 1914 – July 6, 1953), was a Puerto Rican poet and civil rights activist for women and African/Afro-Caribbean writers. She was also an advocate for Puerto Rican independence and served as Secretary General of the Daughters of Freedom, the women’s branch of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party.

Burgos was born and raised in Santa Cruz, a poor area of Carolina, Puerto Rico where her father owned a farm in addition to working as a member of the Puerto Rican National Guard. She was the oldest of her thirteen siblings until unfortunately, six of her younger siblings died of malnutrition. As the oldest in an underprivileged home, she was the only one that was given the opportunity to attend school.

Beginning a teaching careerBurgos graduated from Munoz Rivera Primary in 1928 and was awarded a scholarship to attend University High School, so her family moved to Rio Piedras. This would influence her later on to write her first work, Rio Grande de Loiza. She was a very intelligent student and learned to love literature at a young age. The writings of Luis Llorens Torres, Clara Lair, Rafael Alberti, and Pablo Neruda were among some of the people who influenced her career as a young poet.

Three years later, she was enrolled in the University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras Campus to become a teacher. In 1933 at the age of nineteen, she earned her teaching degree from the University of Puerto Rico and taught at Feijoo Elementary School in Barrio Cedro Arriba of Naranjito, Puerto Rico.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Failed marriages leading to depressionHer teaching career was cut short after Burgos met her first husband, Ruben Rodriguez Beauchamp, in 1934. She started doing civil rights work in 1936 and became a member of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party (Partido Nacionalista de Puerto Rico) and was later elected as the Secretary-General of the Daughters of Freedom, women’s branch of the Nationalist Party. The start to her new career was followed by the end of her marriage to Rodriguez. Burgos and Beauchamp divorced just three years later in 1937.

After her divorce, Burgos started an intense romantic relationship with Dominican historian, physician, and political Juan Isidro Jiménez Grullón. Little did she know he would become a big inspiration for her poems later on in her career that discusses her love for him. They traveled to Cuba together in 1939 where Burgos briefly attended school at the University of Havana. She then traveled to New York City where she worked as a journalist for Pueblos Hispanos, a progressive newspaper.

Her relationship with Grullón started to take a negative turn shortly after they arrived in Cuba. Burgos tried to save the relationship but failed to do so. She decided to leave and return to New York by herself where she worked menial jobs in order to support herself.

While starting a life of her own in New York City, Burgos met Vieques musician, Armando Marín. They got married in 1943 but this marriage also ended in divorce. As a result, Burgos fell further into depression and alcoholism.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

ThemesBurgos had already become a published writer in journals and newspapers by the early 1930s. She also published three books that contained a collection of her poems. To promote her first two books, she traveled all over Puerto Rico giving book readings. Her third book was published in 1954 and contained a collection of the intimate, land, and social struggles of those oppressed on the island.

Many critics claim that Burgos’ poetry is the work of feminist writers and poets along with that of other Latinx authors as she writes in one of her poems: “I am life, strength, woman.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Soldaderas” by Yasmin Hernandez, 2011

“Soldaderas” by Yasmin Hernandez, 2011. . . . . . . . . .

Awards and HonorsIn July 1940, Burgos was awarded a Puerto Rican literary prize for her second collection of poems, Canción de la Verdad Sencilla (Song of the Simple Truth).

In 1986, Julia de Burgos was awarded by the Spanish Department of the University of Puerto Rico and was granted a doctorate in Human Arts and Letters.

In 2002, a documentary about the life of Julia de Burgos was created titled “Julia, Toda en mi…” directed and produced by Ivonne Belén. In 1978 another biopic of her life titled “Vida y poesía de Julia de Burgos,” was filmed and released in Puerto Rico.

In 2006, a mosaic mural titled “Remembering Julia,” by artist Manny Vega was inaugurated. It is located between 106th Street between Lexington and Third Avenue in East Harlem.

On September 14, 2010, the United States Postal Service held a ceremony in San Juan in honor of Burgos’s life and literary work. They issued a first-class postage stamp which was the 26th release in the postal system’s Literary Arts series. Toronto-based artist Jody Hewgill created the stamp’s beautiful portrait.

In 2011, Yasmin Hernandez created a mural called “Soldaderas” (Women Soldiers) that was inaugurated at the community garden Modesto Flores Garden on Lexington Avenue between 104th and 105th street. Interestingly, just one block away inside the old building of P.S. 72 is the Julia Burgos Latino Cultural Center. This is of great importance to the Latinx community as it is one of the mainstays of cultural life in El Barrio. This year, she was also inducted into the New York Writers Hall of Fame.

On May 29, 2014, twelve notable women were honored with plaques in the “La Plaza en Honor a la Mujer Puertorriqueña” (Plaza in Honor of Puerto Rican Women) in San Juan. Burgos was among the twelve who were honored who, according to their plaques, stand out by virtue of their merits and legacies.

. . . . . . . . . .

Portrait of Julia de Burgos by Jody Hewgill, 2010

Portrait of Julia de Burgos by Jody Hewgill, 2010. . . . . . . . . .

An early deathOn June 28, 1953, Julia de Burgos left a relative’s home in Brooklyn where she had been living. She was nowhere to be found until July 6, 1953 when she had collapsed on a sidewalk in the Spanish Harlem section of Manhattan.

After being taken to a hospital in Harlem, she died of pneumonia at the young age of thirty-nine. Burgos was not wearing any ID when she passed away and was buried as “Jane Doe” at the public cemetery on Hart Island.

Her friends began to look for her after noticing that she had been missing. Her disappearance was even recognized by El Diario/La Prensa as they published a notice an an effort to find her. After various days of extreme searching, her body was unearthed and sent to Carolina, her hometown, for a proper burial.

. . . . . . . . . .

“Remembering Julia” by Manny Vega, 2006

“Remembering Julia” by Manny Vega, 2006Major Works

Song of the Simple Truth: The Complete Poems of Julia de Burgos (dual-language edition: Spanish, English), trans. Jack Agueros. Curbstone Books – 1997 Yo misma fui mi ruta, Ediciones Huracán (“I myself was my route, Hurricane Editions”) – 1986Amor y soledad, Ediciones Torremozas (“Love and loneliness, Torremozas Editions”) – 1994El Mar Y Tu, Ediciones Huracán (“The Sea and You, Hurricane Editions”) – 1981Canción De La Verdad Sencilla (Vortice Ser), Ediciones Huracán (“Song of the Simple Truth (Vortex Be), Hurricane Editions”) – 1982Poema en Veinte Surcos, Ediciones Huracán (“Poem in Winding Furrows, Hurricane Editions”) – 1983Poema Río Grande de Loíza (“Great River Poem of Loiza”)Poemas exactos de mí misma (“Exact poems of myself”)Dame tu hora perdída (“Give me your lost time”)Ay, ay, ay de la grifa negra (“Oh, oh, oh of the black grif”)Biographies

Becoming Julia de Burgos: The Making of a Puerto Rican Icon by Vanessa Perez Rosario (2014)Julia: Cuando Los Grandes Eran Pequeños by Georgina Lázaro (2006)More Information

Wikipedia Voices of NY The New York Times Discussion of Julia de Burgos’ life on NYR Daily. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Julia de Burgos appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 27, 2019

The Professor by Charlotte Brontë: A 19th Century Analysis

Though Jane Eyre was Charlotte Brontë‘s first published novel, The Professor was actually the first novel that she wrote. It wasn’t published until 1857, two years after her death and having secured her literary reputation.

The resounding failure of a book of poems she produced with sisters Emily and Anne in 1846 didn’t stop Charlotte from spearheading an effort to find a publisher for the novels that they had been working on. They continued to use the assumed masculine names that appeared on their book of poetry. They styled themselves as Currer Bell (Charlotte), Ellis Bell (Emily), and Acton Bell (Anne).

At first, and for some time, they had no luck. Charlotte described their efforts: “We each set to work on a prose tale: Ellis Bell produced Wuthering Heights, Acton Bell, Agnes Grey, and Currer Bell also wrote a narrative in one volume [referring to The Professor]. These MSS. were perseveringly obtruded upon various publishers for the space of a year and a half; usually, their fate was an ignominious and abrupt dismissal …”

Many rejections

Charlotte Brontë’s manuscript for The Professor made its rounds and was rejected (or ignored) by half a dozen London publishers. With nowhere near the houses as there are today, each disappointment was significant. Adding to the pain was that her sisters’ novels found a home, while hers didn’t. Yet Charlotte did what any savvy would-be author would. Instead of sitting idly, pining for news, she worked on her next novel.

At last, finally getting some encouragement from Messers Smith and Elder that her next submission might get some honest attention, her next manuscript was at the ready to submit and she dispatched it, post haste. That new manuscript was none other than Jane Eyre.

The publisher must have sensed a winner; the book was hastily brought out just six weeks after acceptance, and became an immediate bestseller. The Professor, meanwhile, continued to languish, and was published posthumously, remaining one of Brontë’s more obscure works.

The Professor was something of a roman à clef, based on Charlotte’s experiences while studying and teaching in Brussels. The title character was based on Constantin Héger, the headmaster of the school, a married man with children with whom Charlotte had fallen in love. Usually no-nonsense and practical, if not entirely level-headed, she became obsessed with Héger and made something of a fool of herself — though that is a subject for a different post entirely.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Charlotte Brontë

. . . . . . . . .

This excellent analysis of The Professor is by Mary Augusta Ward (1851 – 1920), an early and avid Brontë biographer. It originally appeared in The Brontë Prefaces, 1899 – 1900.

It is in April 1846 that we discover a first mention of The Professor in a letter from Charlotte Brontë to Messrs. Aylott & Jones, the publishers of the little volume of ‘Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell’ which made its modest appearance in that year. Miss Brontë consults Messrs. Aylott & Co. “on behalf of C., E. and A. Bell” as to how they can best publish three tales already written by them—whether in three connected volumes or separately. The advice given was no doubt prudent and friendly—but it did not help The Professor.

The story went fruitlessly to many publishers. It returned to Charlotte, from one of its later quests, on the very morning of the day on which Mr. Brontë underwent an operation for cataract at Manchester — August 25, 1846. That evening, as we have seen, she began Jane Eyre.

. . . . . . . . .

Jane Eyre: A Late 19th-century analysis by Mary A. Ward

. . . . . . . . .

After the great success of the first two books, she would have liked to publish The Professor. But Mr. Smith and Mr. Williams dissuaded her; and to their dissuasion we owe Villette; for if The Professor had appeared in 1851, Miss Brontë could have made no such further use of her Brussels materials as she did actually put them to in Villette.

The story was finally published after the writer’s death, and when the strong interest excited by Mrs. Gaskell’s Memoir led naturally to a demand for all that could yet be given to the public from the hand of Currer Bell.

There is little to add to the writer’s own animated preface. As she herself points out, the book is by no means the book of a novice. It was written in the author’s thirtieth year, after a long apprenticeship to the art of writing. Those innumerable tales, poems, and essays, composed in childhood and youth, of which Mrs. Gaskell and Mr. Shorter between them give accounts so suggestive and remarkable, were the natural and right foundation for all that followed.

The Professor shows already a method of composition almost mature, a pronounced manner, and the same power of analysis, within narrower limits, as the other books. What it lacks is color and movement.

The characters — Crimsworth, Hunsworth, and Frances Henri

Crimsworth as the lonely and struggling teacher, is inevitably less interesting — described, at any rate, by a woman — than Lucy Snowe under the same conditions, and in the same surroundings. His rôle is not particularly manly; and he does not appeal to our pity.

The intimate autobiographical note, which makes the spell of Villette, is absent; we miss the passionate moods and caprices, all the perennial charm of variable woman, which belongs to the later story. There are besides no vicissitudes in the plot. Crimsworth suffers nothing to speak of; he wins his Frances too easily; and the reader’s emotions are left unstirred.

Hunsworth is really the critical element in the story. If he were other than he is, The Professor would have stood higher in the scale. For the conception of him is both ambitious and original. But it breaks down. He puzzles us; and yet he is not mysterious. For that he is not human enough. In the end we find him merely brutal and repellent, and the letter to Crimsworth, which accompanies the gift of the picture, is one of those extravagances which destroy a reader’s sense of illusion.

Great pains have been taken with him; and when he enters he promises much; but he is never truly living for a single page, and half way through the book he has already become a mere bundle of incredibilities. Let the reader put him beside Mr. Helstone of Shirley, beside even Rochester, not to speak of Dr. John or Monsieur Paul, and so realize the difference between imagination working at ease, in happy and vitalizing strength, and the same faculty toiling unprofitably and half-heartedly with material which it can neither fuse nor master.

On the other hand Frances Henri, the little lace-mender, is a figure touched at every point with grace, feeling and truth. She is an exquisite sketch — a drawing in pale, pure color, all delicate animation and soft life. She is only inferior to Caroline Helstone because the range of emotion and incident that her story requires is so much narrower than that which Caroline passes through. One feels her thrown away on The Professor.

An ampler stage and a warmer air should have been reserved for her; adventures more subtly invented; and a lover less easily victorious. But the scene in which she makes tea for Crimsworth — so at least one thinks as one reads it—could hardly be surpassed for fresh and tender charm; although when the same material is used again for the last scenes of Villette, it is not hard to see how the flame and impetus of a great book may still heighten and deepen what was already excellent before.

. . . . . . . . .

Villette — a Portrait of a Woman in Shadow

. . . . . . . . .

The Professor indeed is grey and featureless compared with any of Charlotte Brontë’s other work. The final impression is that she was working under restraint when writing it, and that her proper gifts were consciously denied full play in it.

In the preface of 1851, she says, as an explanation of the sobriety of the story: “In many a crude effort destroyed almost as soon as composed, I had got over any such taste as I might once have had for ornamented and redundant composition, and come to prefer what was plain and homely.”

In other words, she was putting herself under discipline in The Professor; trying to subdue the poetical impulse; to work as a realist and an observer only.

According to her own account of it, the publishers interfered with this process. They would not have The Professor; and they welcomed Jane Eyre with alacrity. She was therefore thrown back, so to speak, upon her faults; obliged to work in ways more “ornamented” and “redundant;” and thus the promise of realism in her was destroyed.

. . . . . . . . .

The Professor by Charlotte Brontë on Amazon

. . . . . . . . .

The explanation is one of those which the artist will always supply himself with on occasion. In truth, the method of The Professor represents a mere temporary reaction — an experiment — in Charlotte Brontë’s literary development. When she returned to that exuberance of imagination and expression which was her natural utterance, she was not merely writing to please her publishers and the public. Rather it was like Emily’s passionate return to the moorland —

I’ll walk where my own nature would be leading,

It vexes me to choose another guide …

The strong native bent reasserted itself, and with the happiest effects.

But because of what came after, and because the mental history of a great and delightful artist will always appeal to the affectionate curiosity of later generations, The Professor will continue to be read both by those who love Charlotte Brontë, and by those who find pleasure in tracking the processes of literature. It needs no apology as a separate entity; but from its relation to Villette it gains an interest and importance the world would not otherwise have granted it.

It is the first revelation of a genius which from each added throb of happiness or sorrow, from each short after-year of strenuous living,—per damna, per cœdes—was to gain fresh wealth and steadily advancing power.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Professor by Charlotte Brontë: A 19th Century Analysis appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 26, 2019

Anne Brontë

Anne Brontë (January 17, 1820 – May 28, 1849) was a British author born in Thornton, West Yorkshire, the daughter of Patrick Brontë, a clergyman, and Maria Branwell. She followed in her older sisters’ (Charlotte and Emily Brontë) paths by delving into the literary world as a novelist and poet.

Along with her sisters and brother Branwell, Anne grew up in Haworth, an isolated town on the moors of Yorkshire. Anne Brontë was one of six, raised by her father after the death of her mother a year after Anne was born. The children’s aunt Elizabeth Branwell acted as their mother and helped inspire Anne spiritually as their relationship was the closest of all. The two oldest Brontë sisters died young.

The four surviving siblings received little formal education and grew up in imaginative play, constructing a make-believe world called Angria, putting on plays, and creating journals and magazines. Anne’s make-believe world, Gondal, became the setting for many of her literary pieces. She and Emily created the kingdom of Gondal, yet another fictional world that lay in the North Pacific.

In her sisters’ footstepsLike her sisters, Anne spent much of her life at the family parsonage in Haworth, England, on the Yorkshire moors. She left home briefly to attend a boarding school while in her teens, and at age nineteen, began working as a governess. These experiences wove themselves into her first novel, Agnes Grey.

Following in the footsteps of her sisters, she studied at Roehead School, where she began to write poetry. Her work had themes of emotional attachment to her home, which she ultimately had to leave, determined to support herself.

It is suspected that Anne and William Weightman, a curate in Haworth where she grew up, fell in love. Poetry exchanged and character inspiration suggests that their relationship was built on mutual fondness. When William died, Anne’s poetry contained motifs of grief and longing for connection.

Her poetry, though skillful, wasn’t nearly as brilliant as Emily’s, became part of a volume of poems, along with Charlotte’s, and published in 1846. Titled Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, the volume, sold a humiliating total of two copies, did not dampen the sisters’ desired to continue writing and pursuing publication.

Agnes GreyAgnes Grey, Anne’s debut novel (1847) took inspiration from her time teaching at the Ingham family’s Blake Hall. She worked as a governess, caring for and teaching children who were badly behaved. Dissatisfied with her performance, the Ingham family let Anne go after a year, but the experience influenced her writings later on.

Unlike her sisters, Anne spent more time traveling, which allowed for her experiences with religion and society to come through in her writing. She expressed progressive observations for her time, as well as a feminist bent.

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

. . . . . . . . . .

The Tenant of Wildfell HallAnne’s second novel, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) was more popular than Agnes Grey, yet never achieved the renown of Charlotte’s novels. Like Agnes Grey, it was written under the pen name of “Action Bell” so as to disguise her gender. Both of Anne’s novels, as well as her poems, contain many autobiographical elements that correspond with events and people prominent in her life. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, now considered a groundbreaking feminist novel, appeared in 1848.

All through the late 19th and early 20th century, fascination with the Brontë sisters continued on both sides of the Atlantic. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, as part of a May 1900 article on the literary sisters’ lives, offered these insights on The Tenant of Wildfell Hall:

Mary A. Ward [1851 – 1920; a Brontë biographer] says of Anne Brontë that she “serves a twofold purpose in the study of what the Brontë wrote and were. In the first place, her gentle and delicate presence; her sad, short story; her hard life and early death, enter deeply into the poetry and tragedy that have always been entwined with the memory of the Brontë, as women, and as writers.

In the second, the books and poems that she wrote serve as a matter of comparison by which to test the greatness of her two sisters. She is the measure of their genius — like them, yet not with them.”

It is Mrs. Ward’s opinion that The Tenant of Wildfell Hall shows the effect of Bramwell Brontë’s dissipations. He was a victim of both opium and drink, and he seems to have led his sisters to believe that he was the possessor of all manner of dark and guilty secrets. They did not know enough of the world to differentiate between the frenzied dreams of an opium drunkard and the reality; there is no reason to think that the offenses of which he accused himself had any other origin than in his own disordered mind.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall bears traces of these supposed forbidding revelations — revelations that had a most unhappy effect on his three sisters. Their brother’s fate could be borne by Charlotte and Emily; it crushed Anne.

It seems strange that so gentle a creature as Anne — “Acton Bell” — should have written such a book as The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. She is said to have written it as a warning, and the necessity for it is believed to have had its origin in her belief in her brother’s fancied revelations of his own moral turpitude.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Brontë sisters’ path to publication

. . . . . . . . . .

An early deathUnfortunately, the literary career of this talented writer was cut short, as she hadn’t yet turned thirty when she died of was called consumption (pulmonary tuberculosis) in 1849.

Following Branwell’s death in September of 1848 at the age of thirty-one, Emily became ill. Though she was wracked with misery, she refused medical attention until it was too late, and died in mid-December of that same year at the age of thirty.

The shock of Emily’s death weakened Anne, and she caught what was thought to be the flu. But alas, it was also consumption. Anne, characteristically, faced the news with courage, though she was disappointed that she would not have the chance to further her ambition as a writer. Her last poem was “A Dreadful Darkness Closes In” — describing an imminent death. She wrote to Ellen Nussey, a dear friend she shared with Charlotte:

“I have no horror of death: if I thought it inevitable I think I could quietly resign myself to the prospect … But I wish it would please God to spare me not only for Papa’s and Charlotte’s sakes, but because I long to do some good in the world before I leave it. I have many schemes in my head for future practice — humble and limited indeed — but still I should not like them all to come to nothing, and myself to have lived to so little purpose. But God’s will be done.”

Over the next few months, Anne regained some strength and was even able to travel to Scarborough. It was hoped that a change of scene and fresh sea air would improve her health, but it was not to be. When death was at hand, she was unable to travel back to Haworth and died in Scarborough on May 28, 1849, at the age of twenty-nine.

LegacyA year after Anne’s death, Charlotte did something that was quite surprising, bordering on unforgivable: She prevented the re-publication of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. She remarked in 1850, “Wildfell Hall it hardly appears to me desirable to preserve. The choice of subject in that work is a mistake, it was too little consonant with the character, tastes and ideas of the gentle, retiring inexperienced writer.”

The result was that Anne’s work received far less critical attention for many decades, and was viewed as a rather minor Brontë, without the genius of her sisters. Much later, her work was reassessed, and more contemporary biographies and criticism have given her more of her due as an important literary figure.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is now viewed as a major contribution to literature. In 2013, Sally McDonald of the Brontë Society noted that Anne Brontë is “now viewed as the most radical of the sisters, writing about tough subjects such as women’s need to maintain independence and how alcoholism can tear a family apart.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Anne Brontë page on Amazon

More about Anne Brontë on this site

Quotes from Agnes Grey & The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Without the Veil Between — Anne Brontë: A Fine and Subtle Spirit The Brontë Sisters’ Path to PublicationMajor Works

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Agnes GreyThe Complete Poems of Anne BrontëPoems by Currer, Ellis and Acton BellBiographies about Anne Brontë

A Life of Anne Brontë by Edward ChithamMore Information

Wikipedia Reader discussion of Anne Brontë’s books on GoodreadsFilm adaptation

Tenant of Wildfell Hall mini-seriesRead and listen online

Audio versions of Anne Brontë’s works on Librivox Anne Brontë on Project GutenbergVisit the Brontë’s Birthplace and Home

Brontë Parsonage , Haworth, UK. . . . . . . . . .

Anne Brontë’s grave at Scarborough. The gravestone mistakenly

gives her age of death as 28; she was actually 29.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Anne Brontë appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.