Nava Atlas's Blog, page 67

May 31, 2019

Trifles by Susan Glaspell (full text of the 1916 one-act play)

Trifles is a 1916 one-act play by the American author Susan Glaspell (1876 – 1948). It’s one of her most anthologized works, along with the 1917 short story she based upon this play, A Jury of Her Peers. Trifles was first performed at the Wharf Theater in Provincetown Massachusetts in August of 1916. The author herself performed as Mrs. Hale, the wife of a neighboring farmer.

Glaspell’s inspiration was the true crime story of the murder of John Hossack, a 59-year-old farmer. Working as a journalist at the time of the incident in 1900, Glaspell covered it for the Des Moines Daily News. The case was a sensation, because Hossack’s wife Margaret was accused of killing him. Neighbors believed that Margaret Hossack was an abused wife, and thus, she was the object of suspicion.

Margaret claimed that John had been murdered with an axe by an intruder. She was found guilty, but later, the verdict was overturned on appeal. A great reprint of Glaspell’s coverage of the actual case can be read here. Shortly after reporting on this story, Glaspell quit journalism to write fiction.

Some years later, the incident came back to haunt her. She wroteTrifles in ten days, and a year later fashioned it into the short story A Jury of Her Peers. Both had a feminist slant.

The plot of the play, in a nutshell, is as follows: George Henderson (County Attorney), Henry Peters (the sheriff) and his wife, and Mr. and Mrs. Hale (neighboring farmers) enter the Wright’s empty farmhouse. The previous day, Mr. Wright was found dead in an upstairs bedroom with a top around his neck.

When Mrs. Wright was questioned, she claimed that someone had broken in and strangled her husband while she was asleep. Mrs. Hale and Mrs. Peters hunt around the kitchen and hallways for clues to determine whether Mrs. Wright is telling the truth. The men are unable to find evidence, searching in the areas where the man of the house rules —the bedroom, barn, etc. They dismiss the wife’s sphere, including the kitchen, saying that women worry mainly about “trifles.”

The women find a dead canary, with its neck wrung, which leads them to believe that Mr. Wright killed it. That, in turn, may have led to Mrs. Wright killing her husband in a similar manner. Sympathizing with Mrs. Wright because she was an abused wife, they hide the evidence and thus spare her from punishment for killing her husband. The caged bird is a common symbol of the oppression of women.

And now, on to the play …

. . . . . . . . . .

Susan Glaspell, around 1918

. . . . . . . . . .

CAST

GEORGE HENDERSON (County Attorney)

HENRY PETERS (Sheriff)

LEWIS HALE, A neighboring farmer

MRS. PETERS

MRS. HALE

SCENE

The kitchen is the now abandoned farmhouse of JOHN WRIGHT, a gloomy kitchen, and left without having been put in order—unwashed pans under the sink, a loaf of bread outside the bread-box, a dish-towel on the table—other signs of incompleted work.

At the rear the outer door opens and the SHERIFF comes in followed by the COUNTY ATTORNEY and HALE. The SHERIFF and HALE are men in middle life, the COUNTY ATTORNEY is a young man; all are much bundled up and go at once to the stove. They are followed by the two women—the SHERIFF’s wife first; she is a slight wiry woman, a thin nervous face. MRS HALE is larger and would ordinarily be called more comfortable looking, but she is disturbed now and looks fearfully about as she enters. The women have come in slowly, and stand close together near the door.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: (rubbing his hands) This feels good. Come up to the fire, ladies.

MRS PETERS: (after taking a step forward) I’m not—cold.

SHERIFF: (unbuttoning his overcoat and stepping away from the stove as if to mark the beginning of official business) Now, Mr Hale, before we move things about, you explain to Mr Henderson just what you saw when you came here yesterday morning.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: By the way, has anything been moved? Are things just as you left them yesterday?

SHERIFF: (looking about) It’s just the same. When it dropped below zero last night I thought I’d better send Frank out this morning to make a fire for us—no use getting pneumonia with a big case on, but I told him not to touch anything except the stove—and you know Frank.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: Somebody should have been left here yesterday.

SHERIFF: Oh—yesterday. When I had to send Frank to Morris Center for that man who went crazy—I want you to know I had my hands full yesterday. I knew you could get back from Omaha by today and as long as I went over everything here myself—

COUNTY ATTORNEY: Well, Mr Hale, tell just what happened when you came here yesterday morning.

HALE: Harry and I had started to town with a load of potatoes. We came along the road from my place and as I got here I said, I’m going to see if I can’t get John Wright to go in with me on a party telephone.’ I spoke to Wright about it once before and he put me off, saying folks talked too much anyway, and all he asked was peace and quiet—I guess you know about how much he talked himself; but I thought maybe if I went to the house and talked about it before his wife, though I said to Harry that I didn’t know as what his wife wanted made much difference to John—

COUNTY ATTORNEY: Let’s talk about that later, Mr Hale. I do want to talk about that, but tell now just what happened when you got to the house.

HALE: I didn’t hear or see anything; I knocked at the door, and still it was all quiet inside. I knew they must be up, it was past eight o’clock. So I knocked again, and I thought I heard somebody say, ‘Come in.’ I wasn’t sure, I’m not sure yet, but I opened the door—this door (indicating the door by which the two women are still standing) and there in that rocker—(pointing to it) sat Mrs Wright.

(They all look at the rocker.)

COUNTY ATTORNEY: What—was she doing?

HALE: She was rockin’ back and forth. She had her apron in her hand and was kind of—pleating it.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: And how did she—look?

HALE: Well, she looked queer.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: How do you mean—queer?

HALE: Well, as if she didn’t know what she was going to do next. And kind of done up.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: How did she seem to feel about your coming?

HALE: Why, I don’t think she minded—one way or other. She didn’t pay much attention. I said, ‘How do, Mrs Wright it’s cold, ain’t it?’ And she said, ‘Is it?’—and went on kind of pleating at her apron. Well, I was surprised; she didn’t ask me to come up to the stove, or to set down, but just sat there, not even looking at me, so I said, ‘I want to see John.’

And then she—laughed. I guess you would call it a laugh. I thought of Harry and the team outside, so I said a little sharp: ‘Can’t I see John?’ ‘No’, she says, kind o’ dull like. ‘Ain’t he home?’ says I. ‘Yes’, says she, ‘he’s home’. ‘Then why can’t I see him?’ I asked her, out of patience. ”Cause he’s dead’, says she. ‘Dead?’ says I.

She just nodded her head, not getting a bit excited, but rockin’ back and forth. ‘Why—where is he?’ says I, not knowing what to say. She just pointed upstairs—like that (himself pointing to the room above) I got up, with the idea of going up there.

I walked from there to here—then I says, ‘Why, what did he die of?’ ‘He died of a rope round his neck’, says she, and just went on pleatin’ at her apron. Well, I went out and called Harry. I thought I might—need help. We went upstairs and there he was lyin’—

COUNTY ATTORNEY: I think I’d rather have you go into that upstairs, where you can point it all out. Just go on now with the rest of the story.

HALE: Well, my first thought was to get that rope off. It looked … (stops, his face twitches) … but Harry, he went up to him, and he said, ‘No, he’s dead all right, and we’d better not touch anything.’ So we went back down stairs.

She was still sitting that same way. ‘Has anybody been notified?’ I asked. ‘No’, says she unconcerned. ‘Who did this, Mrs Wright?’ said Harry. He said it business-like—and she stopped pleatin’ of her apron. ‘I don’t know’, she says. ‘You don’t know?’ says Harry. ‘No’, says she. ‘Weren’t you sleepin’ in the bed with him?’ says Harry.

‘Yes’, says she, ‘but I was on the inside’. ‘Somebody slipped a rope round his neck and strangled him and you didn’t wake up?’ says Harry. ‘I didn’t wake up’, she said after him. We must ‘a looked as if we didn’t see how that could be, for after a minute she said, ‘I sleep sound’.

Harry was going to ask her more questions but I said maybe we ought to let her tell her story first to the coroner, or the sheriff, so Harry went fast as he could to Rivers’ place, where there’s a telephone.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: And what did Mrs Wright do when she knew that you had gone for the coroner?

HALE: She moved from that chair to this one over here (pointing to a small chair in the corner) and just sat there with her hands held together and looking down. I got a feeling that I ought to make some conversation, so I said I had come in to see if John wanted to put in a telephone, and at that she started to laugh, and then she stopped and looked at me—scared, (the COUNTY ATTORNEY, who has had his notebook out, makes a note) I dunno, maybe it wasn’t scared. I wouldn’t like to say it was. Soon Harry got back, and then Dr Lloyd came, and you, Mr Peters, and so I guess that’s all I know that you don’t.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: (looking around) I guess we’ll go upstairs first—and then out to the barn and around there, (to the SHERIFF) You’re convinced that there was nothing important here—nothing that would point to any motive.

SHERIFF: Nothing here but kitchen things.

(The COUNTY ATTORNEY, after again looking around the kitchen, opens the door of a cupboard closet. He gets up on a chair and looks on a shelf. Pulls his hand away, sticky.)

COUNTY ATTORNEY: Here’s a nice mess.

(The women draw nearer.)

MRS PETERS: (to the other woman) Oh, her fruit; it did freeze, (to the LAWYER) She worried about that when it turned so cold. She said the fire’d go out and her jars would break.

SHERIFF: Well, can you beat the women! Held for murder and worryin’ about her preserves.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: I guess before we’re through she may have something more serious than preserves to worry about.

HALE: Well, women are used to worrying over trifles.

(The two women move a little closer together.)

COUNTY ATTORNEY: (with the gallantry of a young politician) And yet, for all their worries, what would we do without the ladies? (the women do not unbend. He goes to the sink, takes a dipperful of water from the pail and pouring it into a basin, washes his hands. Starts to wipe them on the roller-towel, turns it for a cleaner place) Dirty towels! (kicks his foot against the pans under the sink) Not much of a housekeeper, would you say, ladies?

MRS HALE: (stiffly) There’s a great deal of work to be done on a farm.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: To be sure. And yet (with a little bow to her) I know there are some Dickson county farmhouses which do not have such roller towels. (He gives it a pull to expose its length again.)

MRS HALE: Those towels get dirty awful quick. Men’s hands aren’t always as clean as they might be.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: Ah, loyal to your sex, I see. But you and Mrs Wright were neighbors. I suppose you were friends, too.

MRS HALE: (shaking her head) I’ve not seen much of her of late years. I’ve not been in this house—it’s more than a year.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: And why was that? You didn’t like her?

MRS HALE: I liked her all well enough. Farmers’ wives have their hands full, Mr Henderson. And then—

COUNTY ATTORNEY: Yes—?

MRS HALE: (looking about) It never seemed a very cheerful place.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: No—it’s not cheerful. I shouldn’t say she had the homemaking instinct.

MRS HALE: Well, I don’t know as Wright had, either.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: You mean that they didn’t get on very well?

MRS HALE: No, I don’t mean anything. But I don’t think a place’d be any cheerfuller for John Wright’s being in it.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: I’d like to talk more of that a little later. I want to get the lay of things upstairs now. (He goes to the left, where three steps lead to a stair door.)

SHERIFF: I suppose anything Mrs Peters does’ll be all right. She was to take in some clothes for her, you know, and a few little things. We left in such a hurry yesterday.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: Yes, but I would like to see what you take, Mrs Peters, and keep an eye out for anything that might be of use to us.

MRS PETERS: Yes, Mr Henderson.

(The women listen to the men’s steps on the stairs, then look about the kitchen.)

MRS HALE: I’d hate to have men coming into my kitchen, snooping around and criticising.

(She arranges the pans under sink which the LAWYER had shoved out of place.)

MRS PETERS: Of course it’s no more than their duty.

MRS HALE: Duty’s all right, but I guess that deputy sheriff that came out to make the fire might have got a little of this on. (gives the roller towel a pull) Wish I’d thought of that sooner. Seems mean to talk about her for not having things slicked up when she had to come away in such a hurry.

MRS PETERS: (who has gone to a small table in the left rear corner of the room, and lifted one end of a towel that covers a pan) She had bread set. (Stands still.)

MRS HALE: (eyes fixed on a loaf of bread beside the bread-box, which is on a low shelf at the other side of the room. Moves slowly toward it) She was going to put this in there. (picks up loaf, then abruptly drops it. In a manner of returning to familiar things)

It’s a shame about her fruit. I wonder if it’s all gone. (gets up on the chair and looks) I think there’s some here that’s all right, Mrs Peters. Yes—here; (holding it toward the window) this is cherries, too. (looking again) I declare I believe that’s the only one. (gets down, bottle in her hand. Goes to the sink and wipes it off on the outside) She’ll feel awful bad after all her hard work in the hot weather. I remember the afternoon I put up my cherries last summer.

(She puts the bottle on the big kitchen table, center of the room. With a sigh, is about to sit down in the rocking-chair. Before she is seated realizes what chair it is; with a slow look at it, steps back. The chair which she has touched rocks back and forth.)

MRS PETERS: Well, I must get those things from the front room closet, (she goes to the door at the right, but after looking into the other room, steps back) You coming with me, Mrs Hale? You could help me carry them.

(They go in the other room; reappear, MRS PETERS carrying a dress and skirt, MRS HALE following with a pair of shoes.)

MRS PETERS: My, it’s cold in there.

(She puts the clothes on the big table, and hurries to the stove.)

MRS HALE: (examining the skirt) Wright was close. I think maybe that’s why she kept so much to herself. She didn’t even belong to the Ladies Aid. I suppose she felt she couldn’t do her part, and then you don’t enjoy things when you feel shabby. She used to wear pretty clothes and be lively, when she was Minnie Foster, one of the town girls singing in the choir. But that—oh, that was thirty years ago. This all you was to take in?

MRS PETERS: She said she wanted an apron. Funny thing to want, for there isn’t much to get you dirty in jail, goodness knows. But I suppose just to make her feel more natural. She said they was in the top drawer in this cupboard. Yes, here. And then her little shawl that always hung behind the door. (opens stair door and looks) Yes, here it is.

(Quickly shuts door leading upstairs.)

MRS HALE: (abruptly moving toward her) Mrs Peters?

MRS PETERS: Yes, Mrs Hale?

MRS HALE: Do you think she did it?

MRS PETERS: (in a frightened voice) Oh, I don’t know.

MRS HALE: Well, I don’t think she did. Asking for an apron and her little shawl. Worrying about her fruit.

MRS PETERS: (starts to speak, glances up, where footsteps are heard in the room above. In a low voice) Mr Peters says it looks bad for her. Mr Henderson is awful sarcastic in a speech and he’ll make fun of her sayin’ she didn’t wake up.

MRS HALE: Well, I guess John Wright didn’t wake when they was slipping that rope under his neck.

MRS PETERS: No, it’s strange. It must have been done awful crafty and still. They say it was such a—funny way to kill a man, rigging it all up like that.

MRS HALE: That’s just what Mr Hale said. There was a gun in the house. He says that’s what he can’t understand.

MRS PETERS: Mr Henderson said coming out that what was needed for the case was a motive; something to show anger, or—sudden feeling.

MRS HALE: (who is standing by the table) Well, I don’t see any signs of anger around here, (she puts her hand on the dish towel which lies on the table, stands looking down at table, one half of which is clean, the other half messy) It’s wiped to here, (makes a move as if to finish work, then turns and looks at loaf of bread outside the breadbox. Drops towel. In that voice of coming back to familiar things.) Wonder how they are finding things upstairs. I hope she had it a little more red-up up there. You know, it seems kind of sneaking. Locking her up in town and then coming out here and trying to get her own house to turn against her!

MRS PETERS: But Mrs Hale, the law is the law.

MRS HALE: I s’pose ’tis, (unbuttoning her coat) Better loosen up your things, Mrs Peters. You won’t feel them when you go out.

(MRS PETERS takes off her fur tippet, goes to hang it on hook at back of room, stands looking at the under part of the small corner table.)

MRS PETERS: She was piecing a quilt. (She brings the large sewing basket and they look at the bright pieces.)

MRS HALE: It’s log cabin pattern. Pretty, isn’t it? I wonder if she was goin’ to quilt it or just knot it?

(Footsteps have been heard coming down the stairs. The SHERIFF enters followed by HALE and the COUNTY ATTORNEY.)

SHERIFF: They wonder if she was going to quilt it or just knot it! (The men laugh, the women look abashed.)

COUNTY ATTORNEY: (rubbing his hands over the stove) Frank’s fire didn’t do much up there, did it? Well, let’s go out to the barn and get that cleared up. (The men go outside.)

MRS HALE: (resentfully) I don’t know as there’s anything so strange, our takin’ up our time with little things while we’re waiting for them to get the evidence. (she sits down at the big table smoothing out a block with decision) I don’t see as it’s anything to laugh about.

MRS PETERS: (apologetically) Of course they’ve got awful important things on their minds.

(Pulls up a chair and joins MRS HALE at the table.)

MRS HALE: (examining another block) Mrs Peters, look at this one. Here, this is the one she was working on, and look at the sewing! All the rest of it has been so nice and even. And look at this! It’s all over the place! Why, it looks as if she didn’t know what she was about!

(After she has said this they look at each other, then start to glance back at the door. After an instant MRS HALE has pulled at a knot and ripped the sewing.)

MRS PETERS: Oh, what are you doing, Mrs Hale?

MRS HALE: (mildly) Just pulling out a stitch or two that’s not sewed very good. (threading a needle) Bad sewing always made me fidgety.

MRS PETERS: (nervously) I don’t think we ought to touch things.

MRS HALE: I’ll just finish up this end. (suddenly stopping and leaning forward) Mrs Peters?

MRS PETERS: Yes, Mrs Hale?

MRS HALE: What do you suppose she was so nervous about?

MRS PETERS: Oh—I don’t know. I don’t know as she was nervous. I sometimes sew awful queer when I’m just tired. (MRS HALE starts to say something, looks at MRS PETERS, then goes on sewing) Well I must get these things wrapped up. They may be through sooner than we think, (putting apron and other things together) I wonder where I can find a piece of paper, and string.

MRS HALE: In that cupboard, maybe.

MRS PETERS: (looking in cupboard) Why, here’s a bird-cage, (holds it up) Did she have a bird, Mrs Hale?

MRS HALE: Why, I don’t know whether she did or not—I’ve not been here for so long. There was a man around last year selling canaries cheap, but I don’t know as she took one; maybe she did. She used to sing real pretty herself.

MRS PETERS: (glancing around) Seems funny to think of a bird here. But she must have had one, or why would she have a cage? I wonder what happened to it.

MRS HALE: I s’pose maybe the cat got it.

MRS PETERS: No, she didn’t have a cat. She’s got that feeling some people have about cats—being afraid of them. My cat got in her room and she was real upset and asked me to take it out.

MRS HALE: My sister Bessie was like that. Queer, ain’t it?

MRS PETERS: (examining the cage) Why, look at this door. It’s broke. One hinge is pulled apart.

MRS HALE: (looking too) Looks as if someone must have been rough with it.

MRS PETERS: Why, yes.

(She brings the cage forward and puts it on the table.)

MRS HALE: I wish if they’re going to find any evidence they’d be about it. I don’t like this place.

MRS PETERS: But I’m awful glad you came with me, Mrs Hale. It would be lonesome for me sitting here alone.

MRS HALE: It would, wouldn’t it? (dropping her sewing) But I tell you what I do wish, Mrs Peters. I wish I had come over sometimes when she was here. I—(looking around the room)—wish I had.

MRS PETERS: But of course you were awful busy, Mrs Hale—your house and your children.

MRS HALE: I could’ve come. I stayed away because it weren’t cheerful—and that’s why I ought to have come. I—I’ve never liked this place. Maybe because it’s down in a hollow and you don’t see the road. I dunno what it is, but it’s a lonesome place and always was. I wish I had come over to see Minnie Foster sometimes. I can see now—(shakes her head)

MRS PETERS: Well, you mustn’t reproach yourself, Mrs Hale. Somehow we just don’t see how it is with other folks until—something comes up.

MRS HALE: Not having children makes less work—but it makes a quiet house, and Wright out to work all day, and no company when he did come in. Did you know John Wright, Mrs Peters?

MRS PETERS: Not to know him; I’ve seen him in town. They say he was a good man.

MRS HALE: Yes—good; he didn’t drink, and kept his word as well as most, I guess, and paid his debts. But he was a hard man, Mrs Peters. Just to pass the time of day with him—(shivers) Like a raw wind that gets to the bone, (pauses, her eye falling on the cage) I should think she would ‘a wanted a bird. But what do you suppose went with it?

MRS PETERS: I don’t know, unless it got sick and died.

(She reaches over and swings the broken door, swings it again, both women watch it.)

MRS HALE: You weren’t raised round here, were you? (MRS PETERS shakes her head) You didn’t know—her?

MRS PETERS: Not till they brought her yesterday.

MRS HALE: She—come to think of it, she was kind of like a bird herself—real sweet and pretty, but kind of timid and—fluttery. How—she—did—change. (silence; then as if struck by a happy thought and relieved to get back to everyday things) Tell you what, Mrs Peters, why don’t you take the quilt in with you? It might take up her mind.

MRS PETERS: Why, I think that’s a real nice idea, Mrs Hale. There couldn’t possibly be any objection to it, could there? Now, just what would I take? I wonder if her patches are in here—and her things.

(They look in the sewing basket.)

MRS HALE: Here’s some red. I expect this has got sewing things in it. (brings out a fancy box) What a pretty box. Looks like something somebody would give you. Maybe her scissors are in here. (Opens box. Suddenly puts her hand to her nose) Why—(MRS PETERS bends nearer, then turns her face away) There’s something wrapped up in this piece of silk.

MRS PETERS: Why, this isn’t her scissors.

MRS HALE: (lifting the silk) Oh, Mrs Peters—it’s—

(MRS PETERS bends closer.)

MRS PETERS: It’s the bird.

MRS HALE: (jumping up) But, Mrs Peters—look at it! It’s neck! Look at its neck!

It’s all—other side to.

MRS PETERS: Somebody—wrung—its—neck.

(Their eyes meet. A look of growing comprehension, of horror. Steps are heard outside. MRS HALE slips box under quilt pieces, and sinks into her chair. Enter SHERIFF and COUNTY ATTORNEY. MRS PETERS rises.)

COUNTY ATTORNEY: (as one turning from serious things to little pleasantries) Well ladies, have you decided whether she was going to quilt it or knot it?

MRS PETERS: We think she was going to—knot it.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: Well, that’s interesting, I’m sure. (seeing the birdcage) Has the bird flown?

MRS HALE: (putting more quilt pieces over the box) We think the—cat got it.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: (preoccupied) Is there a cat?

(MRS HALE glances in a quick covert way at MRS PETERS.)

MRS PETERS: Well, not now. They’re superstitious, you know. They leave.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: (to SHERIFF PETERS, continuing an interrupted conversation) No sign at all of anyone having come from the outside. Their own rope. Now let’s go up again and go over it piece by piece. (they start upstairs) It would have to have been someone who knew just the—

(MRS PETERS sits down. The two women sit there not looking at one another, but as if peering into something and at the same time holding back. When they talk now it is in the manner of feeling their way over strange ground, as if afraid of what they are saying, but as if they can not help saying it.)

MRS HALE: She liked the bird. She was going to bury it in that pretty box.

MRS PETERS: (in a whisper) When I was a girl—my kitten—there was a boy took a hatchet, and before my eyes—and before I could get there—(covers her face an instant) If they hadn’t held me back I would have—(catches herself, looks upstairs where steps are heard, falters weakly)—hurt him.

MRS HALE: (with a slow look around her) I wonder how it would seem never to have had any children around, (pause) No, Wright wouldn’t like the bird—a thing that sang. She used to sing. He killed that, too.

MRS PETERS: (moving uneasily) We don’t know who killed the bird.

MRS HALE: I knew John Wright.

MRS PETERS: It was an awful thing was done in this house that night, Mrs Hale. Killing a man while he slept, slipping a rope around his neck that choked the life out of him.

MRS HALE: His neck. Choked the life out of him.

(Her hand goes out and rests on the bird-cage.)

MRS PETERS: (with rising voice) We don’t know who killed him. We don’t know.

MRS HALE: (her own feeling not interrupted) If there’d been years and years of nothing, then a bird to sing to you, it would be awful—still, after the bird was still.

MRS PETERS: (something within her speaking) I know what stillness is. When we homesteaded in Dakota, and my first baby died—after he was two years old, and me with no other then—

MRS HALE: (moving) How soon do you suppose they’ll be through, looking for the evidence?

MRS PETERS: I know what stillness is. (pulling herself back) The law has got to punish crime, Mrs Hale.

MRS HALE: (not as if answering that) I wish you’d seen Minnie Foster when she wore a white dress with blue ribbons and stood up there in the choir and sang. (a look around the room) Oh, I wish I’d come over here once in a while! That was a crime! That was a crime! Who’s going to punish that?

MRS PETERS: (looking upstairs) We mustn’t—take on.

MRS HALE: I might have known she needed help! I know how things can be—for women. I tell you, it’s queer, Mrs Peters. We live close together and we live far apart. We all go through the same things—it’s all just a different kind of the same thing, (brushes her eyes, noticing the bottle of fruit, reaches out for it) If I was you, I wouldn’t tell her her fruit was gone. Tell her it ain’t. Tell her it’s all right. Take this in to prove it to her. She—she may never know whether it was broke or not.

MRS PETERS: (takes the bottle, looks about for something to wrap it in; takes petticoat from the clothes brought from the other room, very nervously begins winding this around the bottle. In a false voice) My, it’s a good thing the men couldn’t hear us. Wouldn’t they just laugh! Getting all stirred up over a little thing like a—dead canary. As if that could have anything to do with—with—wouldn’t they laugh!

(The men are heard coming down stairs.)

MRS HALE: (under her breath) Maybe they would—maybe they wouldn’t.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: No, Peters, it’s all perfectly clear except a reason for doing it. But you know juries when it comes to women. If there was some definite thing. Something to show—something to make a story about—a thing that would connect up with this strange way of doing it—

(The women’s eyes meet for an instant. Enter HALE from outer door.)

HALE: Well, I’ve got the team around. Pretty cold out there.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: I’m going to stay here a while by myself, (to the SHERIFF) You can send Frank out for me, can’t you? I want to go over everything. I’m not satisfied that we can’t do better.

SHERIFF: Do you want to see what Mrs Peters is going to take in?

(The LAWYER goes to the table, picks up the apron, laughs.)

COUNTY ATTORNEY: Oh, I guess they’re not very dangerous things the ladies have picked out. (Moves a few things about, disturbing the quilt pieces which cover the box. Steps back) No, Mrs Peters doesn’t need supervising. For that matter, a sheriff’s wife is married to the law. Ever think of it that way, Mrs Peters?

MRS PETERS: Not—just that way.

SHERIFF: (chuckling) Married to the law. (moves toward the other room) I just want you to come in here a minute, George. We ought to take a look at these windows.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: (scoffingly) Oh, windows!

SHERIFF: We’ll be right out, Mr Hale.

(HALE goes outside. The SHERIFF follows the COUNTY ATTORNEY into the other room. Then MRS HALE rises, hands tight together, looking intensely at MRS PETERS, whose eyes make a slow turn, finally meeting MRS HALE‘s. A moment MRS HALE holds her, then her own eyes point the way to where the box is concealed. Suddenly MRS PETERS throws back quilt pieces and tries to put the box in the bag she is wearing. It is too big. She opens box, starts to take bird out, cannot touch it, goes to pieces, stands there helpless. Sound of a knob turning in the other room. MRS HALE snatches the box and puts it in the pocket of her big coat. Enter COUNTY ATTORNEY and SHERIFF.)

COUNTY ATTORNEY: (facetiously) Well, Henry, at least we found out that she was not going to quilt it. She was going to—what is it you call it, ladies?

MRS HALE: (her hand against her pocket) We call it—knot it, Mr Henderson.

(CURTAIN)

More about Trifles by Susan Glaspell Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads Further analysis on ThoughtCoThe post Trifles by Susan Glaspell (full text of the 1916 one-act play) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 30, 2019

Early Poems of Sara Teasdale: 9 Sonnets to Duse (1907)

Sara Teasdale (1884 – 1933) was well known in her time for lyric poetry that celebrated the beautiful things in life, even as she herself struggled with perpetual illness and loneliness. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, she was the daughter of wealthy parents.

In her young adult years in St. Louis, she was part of a group of creative, talented young women who called themselves the Potters. They hand-printed a magazine called The Potter’s Wheel, where Sara’s early poems were first published. This led to the publication of her first book, Sonnets to Duse and Other Poems in 1907. She was twenty-three at the time of its publication.

The title refers to Eleanora Duse (who is pictured throughout this post, beginning with the photo at upper right), an Italian actress who was quite famous at the time and who often went simply by the name of Duse. Sara never got to meet her, but was apparently quite taken with her, if not infatuated.

Why she chose to write this suite of sonnets to the actress isn’t clear. But her references to Sappho and Lesbos hint at an erotic interest, though Sara wasn’t known to have had liaisons with women in her love life. Here are the sonnets to Duse by Sara Teasdale, the poet’s chosen entryway into the literary world.

. . . . . . . .

To Eleonora Duse (I)Oh beauty that is filled so full of tears,

Where every passing anguish left its trace,

I pray you grant to me this depth of grace:

That I may see before it disappears,

Blown through the gateway of our hopes and fears

To death’s insatiable last embrace,

The glory and the sadness of your face,

Its longing unappeased through all the years.

No bitterness beneath your sorrow clings;

Within the wild dark falling of your hair

There lies a strength that ever soars and sings;

Your mouth’s mute weariness is not despair.

Perhaps among us craven earth-born things

God loves its silence better than a prayer.

. . . . . . . .

Portrait of Eleanora Duse in Sonnets to Duse and Other Poems by Sara Teasdale

. . . . . . . . . .

Your beauty lives in mystic melodies,

And all the light about you breathes a song.

Your voice awakes the dreaming airs that throng

Within our music-haunted memories:

The sirens’ strain that sank within the seas

When men forgot to listen, floats along

Your voice’s undercurrent soft and strong.

Sicilian shepherds pipe beneath the trees;

Along the purple hills of drifted sand,

A lone Egyptian plays an ancient flute;

At dawn the Memnon gives his old salute

Beside the Nile, by desert breezes fanned.

The music faints about you as you stand,

And with the Orphean lay it trembles mute.

To Eleonora Duse in “The Dead City”

Were you a Greek when all the world was young,

Before the weary years that pass and pass,

Had scattered all the temples on the grass,

Before the moss to marble columns clung?

I think your snowy tunic must have hung

As now your gown does—wave on wave a mass

Of woven water. As within a glass

I see your face when Homer’s tales were sung.

Alcaeus kissed your mouth and found it sweet,

And Sappho’s hand has lingered in your hand.

You half remember Lesbos as you stand

Where all the times and countries mix and meet,

And lay your weight of beauty at our feet,

A garland gathered in a distant land.

To a Picture of Eleonora Duse in “The Dead City” (I)

Your face is set against a fervent sky,

Before the thirsty hills that sevenfold

Return the sun’s hot glory, gold on gold,

Where Agamemnon and Cassandra lie.

Your eyes are blind whose light shall never die,

And all the tears the closèd eyelids hold,

And all the longing that the eyes have told,

Is gathered in the lips that make no cry.

Yea, like a flower within a desert place,

Whose petals fold and fade for lack of rain,

Are these, your eyes, where joy of sight was slain,

And in the silence of your lifted face,

The cloud is rent that hides a sleeping race,

And vanished Grecian beauty lives again.

. . . . . . . . . .

Portrait of Eleanora Duse in Sonnets to Duse and Other Poems by Sara Teasdale

. . . . . . . . .

Carved in the silence by the hand of Pain,

And made more perfect by the gift of Peace,

Than if Delight had bid your sorrow cease,

And brought the dawn to where the dark has lain,

And set a smile upon your lips again;

Oh strong and noble! Tho’ your woes increase,

The gods shall hear no crying for release,

Nor see the tremble that your lips restrain.

Alone as all the chosen are alone,

Yet one with all the beauty of the past;

A sister to the noblest that we know,

The Venus carved in Melos long ago,

Yea, speak to her, and at your lightest tone,

Her lips will part and words will come at last.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Sara Teasdale

. . . . . . . . . .

Oh flower-sweet face and bended flower-like head!

Oh violet whose purple cannot pale,

Or forest fragrance ever faint or fail,

Or breath and beauty pass among the dead!

Yea, very truly has the poet said,

No mist of years or might of death avail

To darken beauty—brighter thro’ the veil

We see the glimmer of its wings outspread.

Oh face embowered and shadowed by thy hair,

Some lotus blossom on a darkened stream!

If ever I have pictured in a dream

My guardian angel, she is like to this,

Her eyes know joy, yet sorrow lingers there,

And on her lips the shadow of a kiss.

To a Picture of Eleonora Duse

Was ever any face like this before—

So light a veiling for the soul within,

So pure and yet so pitiful for sin?

They say the soul will pass the Heavy Door,

And yearning upward, learn creation’s lore—

The body buried ‘neath the earthly din.

But thine shall live forever, it hath been

So near the soul, and shall be evermore.

Oh eyes that see so far thro’ misted tears,

Oh Death, behold, these eyes can never die!

Yea, tho’ your kiss shall rob these lips of breath,

Their faint, sad smile will still elude thee, Death.

Behold the perfect flower this neck uprears,

And bow thy head and pass the wonder by.

To a Picture of Eleonora Duse with the Greek Fire,

in “Francesca da Rimini”

Francesca’s life that was a limpid flame

Agleam against the shimmer of a sword,

Which falling, quenched the flame in blood outpoured

To free the house of Rimino from shame—

Francesca’s death that blazed aloft her name

In guilty fadeless glory, hurling toward

The windy darkness where the tempest roared,

Her spirit burdened by the weight of blame—

Francesca’s life and death are mirrored here

Forever, on the face of her who stands

Illumined and intent beside the blaze,

Grown one with it, and reading without fear

That they shall fare upon the selfsame ways,

Plucked forth and cast away by bloody hands.

A Song to Eleonora Duse in “Francesca da Rimini”

Oh would I were the roses, that lie against her hands,

The heavy burning roses she touches as she stands!

Dear hands that hold the roses, where mine would love to be,

Oh leave, oh leave the roses, and hold the hands of me!

She draws the heart from out them, she draws away their breath,—

Oh would that I might perish and find so sweet a death!

. . . . . . . . . .

Sonnets to Duse and Other Poems by Sara Teasdale on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Early Poems of Sara Teasdale: 9 Sonnets to Duse (1907) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 27, 2019

Sara Teasdale

Sara Teasdale (August 8, 1884 – January 29, 1933) was an American poet known for her deceptively simple lyric poetry that emphasized life’s beauty. Born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri, she was the youngest of four children of wealthy parents. In delicate health throughout her childhood, she was tutored at home until the age of ten.

Despite her privileged background, and being spoiled and petted Sara’s childhood was often lonely. She lived in a separate suite in her family’s grand homes, often left alone. The ill health of her childhood followed her throughout much of her adult life, and she often had to have a nurse-companion.

She described her fragility as “a flower in a toiling world.” Reared to believe that she was fragile and helpless, this was the attitude that dogged her throughout her life.

A slew of early successes and a Pulitzer Prize

Sara was a member of The Potters in St Louis, a group of young female artists led by Lillie Rose Ernst, from the years 1904 to 1907. The group printed their original poetry, prose, and art in The Potter’s Wheel, a monthly magazine.

In 1907, Sara’s first collection, Sonnets to Duse, and Other Poems was published; she was 23 years old at the time. Duse was a well-known actress who Sara idolized, though she never got to meet her. Sara’s second, collection, Helen of Troy and Other Poems, was published in 1911. Both were praised by critics, who noted her mastery of the lyrical style.

Her third collection of poetry, Rivers to the Sea, established itself quickly as one of her most popular works. Love Songs came out in 1917 and earned Sara the Pulitzer Prize the following year, though it was then called the Columbia Poetry Prize.

. . . . . . . .

Sara Teasdale in 1907

. . . . . . . . . .

Sara had several suitors while in her twenties. The poet Vachel Lindsay was very much in love with her, but she didn’t think he could keep her in the style to which she was accustomed. He was crushed by the rejection.

In 1914 she married Ernst Filsinger, a businessman who had long admired her poetry. Soon after they married, the couple moved to New York City where they took up residence in an apartment on Central Park West.

Filsinger had to travel a great deal for business, leaving Sara alone and lonely, echoing her childhood. Despite the fact that he was generally a faithful and loving husband, her own illnesses and depressions made it difficult for her to sustain a relationship. In 1929, she moved to another state for three months in order to meet the legal criterion for divorce, without her husband’s knowledge. He was completely taken by surprise.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A complex personalityDespite her successes and the accolades that came with them, Sara was plagued with a lack of confidence and constant worries about her health. In A Study Guide for Sara Teasdale’s There Will be Soft Rains (2002) she’s described like this:

“She was the youngest child of a prim family who grew up believing she was a fragile, helpless girl, vulnerable to a variety of illnesses, both physical and emotional. Her perceived frailty resulted in lifelong bouts of nervous exhaustion and chronic weakness, and she remained dependent upon her parents until she married at age thirty.

… Her fondness for music was reflected in the lyric poems she wrote, most very rhythmic and many of which ended up being set to musical scores. Her work at the time centered primarily on love from a woman’s perspective, and its childlike innocence was widely acclaimed, being published in major poetry journals in Chicago, New York, and Europe.

As well-liked as Teasdale’s poetry was, the poet herself became just as admired, and she was welcomed into the circles of America’s most esteemed early twentieth-century writers. But in spite of the popularity, Teasdale was her own worst enemy. She often lapsed into depression without a definable cause and suffered a consistent lack of self-confidence, believing she would never be independent or able to live on her own.”

. . . . . . . . .

Sara Teasdale page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . .

Once the divorce was final, Sara moved back to New York City. Beset with chronic pneumonia, Sara became disillusioned and depressed. No longer able to enjoy the beauty that she expressed in her poetry, she took her own life in 1933 by taking an overdose of sleeping pills. She was 49 years old.

In all, Sara Teasdale had seven books of poetry published in her lifetime. Her finely crafted lyrical poetry was admired, especially by the public. Like the work of many female poets of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, hers has been somewhat forgotten.

Still, her female-centric work, with themes of love, death, and beauty earned her major accolades and prizes, some critics were a bit dismissive of her earlier work. For example, Rivers to the Sea, which earned her the first Columbia Poetry Prize in 1918 (later renamed the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry) was deemed by the New York Times Book Review contributor deemed the book “a little volume of joyous and unstudied song,” and concluded, “Miss Teasdale is first, last, and always a singer.” None of her biographies describe her as a singer, so this assertion is quite curious.

Her later works, including Flame and Shadow (1920), Dark of the Moon (1926), and Stars To-Night (1930) earned her more serious considerations, with reviewers praising the development of her lyric poetry and the artistry in her craft. Strange Victory, her last collection, was published shortly after her death by suicide in 1933 and praised as one of her most significant works.

Some contemporary scholars have argued that Sara’s body of work has been unjustly neglected over the years. For example, Carol B. Schoen, author of the 1986 critical biography, Sara Teasdale, considered her one of the most important lyric poets, yet long overlooked “in favor of more controversial or militant female poets.” This attitude prevailed despite even Sara’s anti-war poetry during World War I.

Sara Teasdale is an intriguing American poet whose work seems ripe for reconsideration.

More about Sara TeasdaleMajor works

Sonnets to Duse and Other Poems (1907)Helen of Troy and Other Poems (1911)Rivers to the Sea (1915)Love Songs (1917)Flame and Shadow (1920)Dark of the Moon (1926)Stars To-night (1930)Strange Victory (1933)Biographies

Sara Teasdale by Carol Schoen (1986)Sara Teasdale: Woman and Poet by William Drake (1989)Sara Teasdale: A Biography by Margaret Haley Carpenter (2011)Read and listen online

Audio recordings on Librivox Project GutenbergMore information and sources

Wikipedia Poetry Foundation Britannica American Literature (contains a great selection of her poetry)Poem HunterReader discussion on Goodreads

. . . . . . . .

Discover more great women poets and their works on this site

This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Sara Teasdale appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 24, 2019

The Tory Lover by Sarah Orne Jewett (1901)

The Tory Lover by Sarah Orne Jewett is a 1901 novel by this esteemed New England author best known for The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896). The story is partly set in Berwick, Maine, where Jewett grew up and spent much of her life, and takes place during the Revolutionary period. Roger Wallingford, a gentleman of Tory ancestry joins the cause of the Patriots through his love for the beautiful Mary Hamilton.

Mary urges Captain Paul Jones, a compatriot of her brother, to give a commission to Wallingford. A nefarious shipmate contrives to have Wallingford arrested for treachery and desertion, and he virtually disappears. Mary believes that the charges are false, so she and his mother set sail for England to find him and clear his name.

This novel, so very different from Jewett’s other works, mainly sketches of the ordinary people of her time and place in Maine, nevertheless was warmly received. Here is one such review from 1901.

A 1901 Review of The Tory Lover by Sarah Orne Jewett

From the original review in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 27, 1901: The Tory Lover by Sarah Orne Jewett will be read with interest by anyone familiar with her Country of the Pointed Firs, Deephaven, and other novels and short stories.

The Tory Lover is a romance with a historical setting. The period is the Revolutionary era, and the action takes place partly in New England and partly in England. Captain Paul Jones is one of the characters of the story, but her figures in it in a different light from that in which he appears in other novels.

. . . . . . . . . .

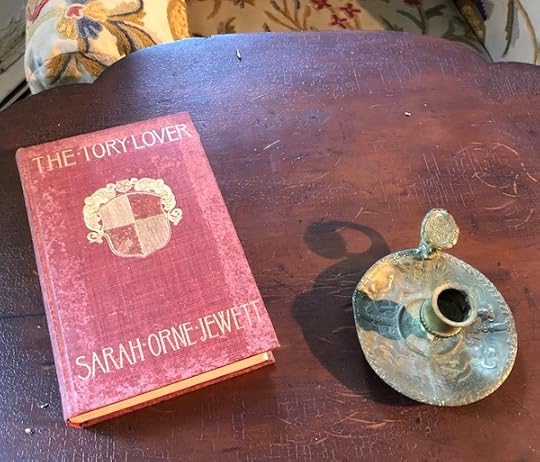

Randomly spotted in a historic home in the Hudson Valley

. . . . . . . . . .

A revolutionary era tale

Colonial Portsmouth, 1777, is when the story opens. The heroine is Mary Hamilton, the lovely daughter of an opulent house, devoted to the American cause. The Tory lover is Roger Wallingford, whose love for Mary has won him from his loyalist proclivities. To show his devotion to the patriot cause, he takes service under Captain Paul Jones, on the Ranger.

It is at Mary Hamilton’s behest that the Ranger’s commander enlists the young man. He knows that she looks on him as an old and trusted friend, and that his love is a hopeless passion. He has no time to court her but loves her nonetheless.

An enemy on board, and imprisonment

Roger sails on the Ranger and does good service on board. He has an enemy on the ship, however, named Dickson, who is a traitor to the American cause as well. In a night raid on the town of Whitehaven, in England, in which Wallingford and Dickson are concerned, the latter sees his opportunity for revenge. He betrays Wallingford into the hands of the British.

Returning to the ship, Dickson is able to spread a false report about Wallingford, and Paul Jones and his comrades believe that he had returned to his Loyalist sentiments and had played the part of a spy and a traitor.

Wallingford is taken to prison and the news of his captivity at last reaches his home in New England. His mother, who is known as a Loyalist, starts out to secure his release and Mary Hamilton accompanies her. She has not the slightest doubt of her lover’s fidelity to the American cause.

Shifting scene to Bristol, England

The story then shifts scene to Bristol, where the two women find good friends and are able to bring their influence to bear to secure a pardon for the young lieutenant. But when they go to the prison they are met with the news that Wallingford, with one or two others, has just escaped, and no one knows where they are.

Paul Jones, going ashore in disguise, encounters Mary Hamilton in Bristol, and there gathers intelligence that leads him to think that Dickson is a traitor. The end of the story is worked out with a great deal of dramatic skill and the ending is sure to satisfy the reader.

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah Orne Jewett

. . . . . . . . . .

A well sustained story with stellar characters

So much for the outline of the tale. The reader will note that while the story has a historical setting, it is not a historical novel. We don’t know that any of the incidents, same some phases of the Ranger’s cruise, figure at all in actual history or tradition. It’s not necessary for the scheme that the author had in mind. The Tory Lover is a romance, pure and simple, but it is one portrayed with a fine touch.

Wallingford is a fine young fellow, but one feels more interest in Mary Hamilton. She’s drawn with a delicate touch, and even the ideal portrait of this charming heroine, painted by Marcia O.Woodbury, which serves as a frontispiece to the book, hardly does her justice.

Paul Jones as a lover shines in a positive new light. He’s much more than just the dashing rover in this story; he’s a gallant and tender gentleman. When Mary looks him straight in the eyes and tells him of her faith in her lover’s honeys and loyalty to the cause he served on the Ranger, Paul Jones receives this evidence of love for another as a loyal gentleman should.

The scene in the little inn where Dickson’s treachery is made clear is also a strong bit of work. Miss Jewett has a reputation for excellence, but she has never done better than The Tory Lover. The story is well sustained throughout, but her pass aren’t overcrowded with action. The love story is subtle, charming in every line, while the literary quality of the story is top notch.

. . . . . . . . . .

Sarah Orne Jewett page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Tory Lover by Sarah Orne Jewett (1901) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 22, 2019

Emma Lazarus

Emma Lazarus (July 22, 1849 – November 17, 1887), American poet, translator, and activist. She’s best known for the poem “The New Colossus” (1883), whose lines, “Give me your tired, your poor …” are inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty.

As touching and world-famous as this poem has remained, it’s but a tiny portion of her body of work. The life of Emma Lazarus, brief as it would be, was filled with accomplishment, not only as a writer, but as an advocate for Jewish immigrants and refugees.

Emma was part of a large Sephardic Jewish family, the fourth of seven children of a well-to-do merchant and sugar refiner, Moses Lazarus. Her mother’s maiden name was Esther Nathan. Most of her ancestors were from Portugal, though they settled in New York well before the American Revolution. Along with some two dozen other Portuguese Jews, they arrived in New Amsterdam after fleeing the Inquisition from their settlement in Recife, Brazil.

A precocious poet and accomplished translator

When she began writing and translating poetry, Emma was still in her teens. Her father, with whom she enjoyed a close rapport, privately printed her first works in 1866. The following year, at age 18, her first collection, Poems and Translations, was published. Her original poems were written when she was between 14 and 17 years old, and the volume also included translations of poems by Dumas, Hugo, and Schiller, among others. The book was praised by Ralph Waldo Emerson and other notable writers and thinkers.

Her subsequent publications included Admetus and Other Poems (1871), Alide: An Episode in Goethe’s Life (a novel, 1874), and The Spagnoletto; (a play in verse, 1876).

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Jewish causes and the plight of refugeesGeorge Eliot’s 1876 novel, Daniel Deronda, had a profound influence on Emma. The story of a young man’s discovery of his Jewish roots in 1870s England led Emma to think more deeply about her own Jewish identity.

She became outspoken about the plight of Russian Jews, who suffered violent pogroms following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. She also became aware of the struggles of Jewish refugees who had fled from the Russian Pale of Settlement to New York, arriving destitute and desperate.

Emma delved into social activism, particularly in the realm of immigrants and refugees. She became involved with Russian Jewish immigrants detained at Castle Garden, and was deeply affected by their experiences. She began to argue for the cause of a Jewish homeland, even before the concept of Zionism began to emerge.

Her work with Jewish immigrants and refugees inspired the writings and poems in Songs of a Semite: The Dance to Death and Other Poems in 1882. It was the first American publication to deal with the struggles of Jewish immigrants and explore Jewish identity.

According to the Guide to the Emma Lazarus papers housed at the American Jewish Historical Society, she also produced:

… a series of fourteen essays printed in 1882 – 1883 in The American Hebrew entitled “Epistles to the Hebrews” was posthumously published in 1900 as a book by the Federation of American Zionists. The essays outlined her Zionist ideas and plans that entailed Jewish centers in both the United States and Palestine.

Emma was one of the founders of Hebrew Technical Institute in New York City. The organization provided vocational training to Jewish immigrants. She also established The Society for the Improvement and Colonization of East European Jews in 1883.

“The New Colossus”

Following a journey to France and England, where she befriended poets Robert Browning and William Morris, Emma received the commission that would forever alter her legacy. She was invited to write a poem for the purpose of raising funds for a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty in 1883.

Though reluctant at first, she finally relented. “The New Colossus,” a sonnet, was first published New York World and The New York Times in 1883. But it wouldn’t be engraved on the Statue of Liberty until 1903, about sixteen years after she had died.

These are the most recited lines (actually the last lines) of the sonnet containing the “lines of world-wide welcome” inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

. . . . . . . . . .

12 Poems by Emma Lazarus, Creator of The New Colossus

. . . . . . . . . .

Emma began to suffer from illness, likely Hodgkin’s lymphoma, in 1884. In 1885, devastated by her father’s death, she traveled to Europe once again, visiting Italy, England, and France. But her condition worsened, and she returned to New York.

She died on November 17, 1887, at the age of 38, and is buried at Congregation Shearith Israel’s Beth Olom Cemetery, Cypress Hills, Queens, New York.

“The New Colossus” would become (and is still) so famous that it has overshadowed much of Emma’s considerable body of work and accomplishments.

Emma Lazarus was one of the first successful and vocal Jewish American authors, and her work was admired and praised by her contemporaries. Her advocacy on behalf of Jewish refugees and her case for the creation of a Jewish homeland were also part of what made her short life so impactful.

. . . . . . . . .

Books by and about Emma Lazarus on Amazon

. . . . . . . . .

Here is a portion of a remembrance of Emma Lazarus that appeared in The Century Magazine shortly after her death:

We cannot restrain a feeling of suddenness and incompleteness and a natural pang of wonder and regret for a life so richly and so vitally endowed thus cut off in its prime. But for us, it is not fitting to question or repine, but rather to rejoice in the rare possession that we hold. What is any life, even the most rounded and complete, but a fragment and a hint?

What Emma Lazarus might have accomplished, had she been spared, it is idle and even ungrateful to speculate. What she did accomplish has real and peculiar significance. It is the privilege of a favored few that every fact and circumstance of their individuality shall add lustre and value to what they achieve.

To be born a Jewess was a distinction for Emma Lazarus, and she in turn conferred distinction upon her race. To be born a woman also lends a grace and a subtle magnetism to her influence. Nowhere is there contradiction or incongruity. Her works bear the imprint of her character, and the character of her works; the same directness and honesty, the same limpid purity of tone, and the same atmosphere of things refined and beautiful.

The vulgar, the false, and the ignoble—she scarcely comprehended them, while on every side she was open and ready to take in and respond to whatever can adorn and enrich life. Literature was no mere “profession” for her, which shut out other possibilities; it was only a free, wide horizon and background for culture.

She was passionately devoted to music, which inspired some of her best poems; and during the last years of her life, in hours of intense physical suffering, she found relief and consolation in listening to the strains of Bach and Beethoven.

When she went abroad, painting was revealed to her, and she threw herself with the same ardor and enthusiasm into the study of the great masters; her last work (left unfinished) was a critical analysis of the genius and personality of Rembrandt.

And now at the end we ask: Has the grave really closed over all these gifts? Has that eager, passionate striving ceased, and “is the rest silence?” Who knows? But would we break, if we could, that repose, that silence and mystery and peace everlasting?

More about Emma LazarusOn this site

12 Poems by Emma Lazarus, Creator of The New ColossusMajor Works

Poems and Translations (1867)Admetus and Other Poems (1871)Alide: An Episode in Goethe’s Life (a novel, 1874)The Spagnoletto (a play in verse, 1876)Songs of a Semite (1882) The Poems of Emma Lazarus (1888; posthumous)Biography

Emma Lazarus in Her World: Life and Letters by Bette Roth Young (1995)Liberty’s Poet: Emma Lazarus by Hannia S. Moore (2005)Liberty’s Voice: The Story of Emma Lazarus by Erica Silverman (2011, ages 6 to 8)Emma’s Poem: The Voice of the Statue of Liberty by Linda Glaser (2013, ages 4 to 7)Emma Lazarus (Jewish Encounters Series) by Esther Schor (2017)More information and sources

Wikipedia Statue of Liberty National Monument Poetry Foundation Jewish Women’s Archive Academy of American Poets. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Emma Lazarus appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 17, 2019

Quotes from Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

How to select quotes from Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf, when almost every sentence in the book is quotable? It’s a tough choice, indeed. The 1925 novel whose narrative is built on the inner consciousness of its characters, particularly Clarissa Dalloway, was groundbreaking in its time. Often called “a novel of one day,” it was almost universally praised for its innovative format. One 1925 review stated:

“Mrs. Woolf makes one aware of one’s own mental experiences in a way no other contemporary writer has ever achieved. Her characters appear upon the scenic screen of Clarissa Dalloway’s consciousness in proportion to her personal reaction to them; and then appear again in a swift soul-probing analysis as they really are.

Clarissa’s charm, her delicate sense of superiority, and naïve speculation upon the problems of others make themselves felt on all with whom she comes in contact. Yet she is loved: one cannot escape her somehow, and, as her returned lover discovers, one can never quite forget her.”

Here is a sampling of quotes from Mrs. Dalloway, though the wiser course would be to read and savor the entire book.

. . . . . . . . . .

“She felt very young; at the same time unspeakably aged. She sliced like a knife through everything; at the same time was outside, looking on. She had a perpetual sense, as she watched the taxi cabs, of being out, out, far out to sea and alone; she always had the feeling that it was very, very dangerous to live even one day. Not that she thought herself clever, or much out of the ordinary.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She thought there were no Gods; no one was to blame; and so she evolved this atheist’s religion of doing good for the sake of goodness.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“He thought her beautiful, believed her impeccably wise; dreamed of her, wrote poems to her, which, ignoring the subject, she corrected in red ink.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Clarissa had a theory in those days — they had heaps of theories, always theories, as young people have. It was to explain the feeling they had of dissatisfaction; not knowing people; not being known. For how could they know each other? You met every day; then not for six months, or years. It was unsatisfactory, they agreed, how little one knew people.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It is a thousand pities never to say what one feels.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There was touch of the bird about her, of the jay, blue-green, light, vivacious, though she was over fifty, and grown very white since her illness.There she perched, never seeing him, waiting to cross, very upright.“

. . . . . . . . . .

“Mrs. Dalloway is always giving parties to cover the silence.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The world wavered and quivered and threatened to burst into flames.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Fear no more, says the heart, committing its burden to some sea, which sighs collectively for all sorrows, and renews, begins, collects, lets fall.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Her life was a tissue of vanity and deceit.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolfon Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“Did it matter then, she asked herself, walking towards Bond Street, did it matter that she must inevitably cease completely; all this must go on without her; did she resent it; or did it not become consoling to believe that death ended absolutely?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“For in marriage a little license, a little independence there must be between people living together day in and day out in the same house; which Richard gave her, and she him.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“With twice his wits, she had to see things through his eyes — one of the tragedies of married life.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A thing there was that mattered; a thing, wreathed about with chatter, defaced, obscured in her own life, let drop every day in corruption, lies, chatter. This he had preserved. Death was defiance. Death was an attempt to communicate; people feeling the impossibility of reaching the centre which, mystically, evaded them; closeness drew apart; rapture faded, one was alone. There was an embrace in death.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“But nothing is so strange when one is in love (and what was this except being in love?) as the complete indifference of other people.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Doesn’t one always think of the past, in a garden with men and women lying under the trees? Aren’t they one’s past, all that remains of it, those men and women, those ghosts lying under the trees, … one’s happiness, one’s reality?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“This late age of the world’s experience had bred in them all, all men and women, a well of tears. Tears and sorrows; courage and endurance; a perfectly upright and stoical bearing.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Her only gift was knowing people almost by instinct, she thought, walking on. If you put her in a room with someone, up went her back like a cat’s; or she purred.

. . . . . . . . . .

“She had influenced him more than any person he had ever known. And always in this way coming before him without his wishing it, cool, ladylike, critical; or ravishing, romantic.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“‘Musing among the vegetables?’— was that it? — ‘I prefer men to cauliflowers‘ — was that it? He must have said it at breakfast one morning when she had gone out on to the terrace — Peter Walsh.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Did it matter then, she asked herself, walking towards Bond Street, did it matter that she must inevitably cease completely? All this must go on without her; did she resent it; or did it not become consoling to believe that death ended absolutely?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“And of course she enjoyed life immensely. It was her nature to enjoy. Anyhow there was no bitterness in her; none of that sense of moral virtue which is so repulsive in good women. She enjoyed practically everything. If you walked with her in Hyde Park now it was a bed of tulips, now a child in a perambulator, now some absurd little drama she made up on the spur of the moment.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She belonged to a different age, but being so entire, so complete, would always stand up on the horizon, stone-white, eminent, like a lighthouse marking some past stage on this adventurous, long, long voyage, this interminable — this interminable life.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

Orlando by Virginia Woolf: Gender and Sexuality Through Time

. . . . . . . . . .

“That she held herself well was true; and had nice hands and feet; and dressed well, considering that she spent little. But often now this body she wore (she stopped to look at a Dutch picture), this body, with all its capacities, seemed nothing — nothing at all. She had the oddest sense of being herself invisible; unseen; unknown; there being no more marrying, no more having of children now, but only this astonishing and rather solemn progress with the rest of them, up Bond Street, this being Mrs. Dalloway; not even Clarissa any more; this being Mrs. Richard Dalloway.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“What is this terror? what is this ecstasy? he thought to himself. What is it that fills me with this extraordinary excitement?

It is Clarissa, he said.

For there she was.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 15, 2019

The “Bachelor Girl” — a Poem by Effie Waller Smith

Born in the rural mountain community of Chloe Creek in Pike County, Kentucky, Effie Waller Smith (1879–1960) was the child of former slaves Sibbie Ratliff and Frank Waller, who ensured that their children were well educated.

She attended Kentucky Normal School for Colored Persons, and from 1900 to 1902 she trained as a teacher, then taught for some years. Her verse appeared in local papers, and she published her first collection, Songs of the Months, in 1904. That same year she entered a marriage that did not last long, and she divorced her husband.

In 1908 she married Deputy Sheriff Charles Smith, but this union was also short-lived. In 1909 she published two further collections, Rhymes from the Cumberland and Rosemary and Pansies. She appears to have stopped writing at the age of 38 in 1917, when her sonnet “Autumn Winds” appeared in Harper’s Magazine. She left Kentucky for Wisconsin in 1918.

This brief bio and the following poem, The “Bachelor Girl,” are excerpted from New Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Writing by Women of African Descent, edited by Margaret Busby. Copyright © 2019 Reprinted with permission by Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. The “Bachelor Girl” is hosted on The New York Public Library’s Digital Schomburg African Women Writers of the 19th Century.

. . . . . . . . . .

New Daughters of Africa, edited by Margaret Busby

is available on Amazon and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . .

From Rhymes from the Cumberland (1909)

She’s no “old maid,” she’s not afraid

To let you know she’s her own “boss,”

She’s easy pleased, she’s not diseased,

She is not nervous, is not cross.

She’s no desire whatever for

Mrs. to precede her name,

The blessedness of singleness

She all her life will proudly claim.

She does not sit around and knit

On baby caps and mittens,

She does not play her time away

With puggy dogs and kittens.

And if a mouse about the house

She sees, she will not jump and scream;

Of handsome beaux and billet doux

The “bachelor girl” does never dream.

She does not puff and frizz and fluff

Her hair, nor squeeze and pad her form.

With painted face, affected grace,

The “bachelor girl” ne’er seeks to charm.

She reads history, biography,

Tales of adventure far and near,

On sea or land, but poetry and

Love stories rarely interest her.

She’s lots of wit, and uses it,

Of “horse sense,” too, she has a store;

The latest news she always knows,

She scans the daily papers o’er.

Of politics and all the tricks

And schemes that politicians use,

She knows full well and she can tell

With eloquence of them her views.

An athlete that’s hard to beat

The “bachelor girl” surely is,

When playing games she makes good aims

And always strictly minds her “biz.”

Amid the hurry and the flurry

Of this life she goes alone,

No matter where you may see her

She seldom has a chaperon.

But when you meet her on the street

At night she has a “32,”

And she can shoot you, bet your boots,

When necessity demands her to.

Her heart is kind and you will find

Her often scattering sunshine bright

Among the poor, and she is sure

To always advocate the right.

On her pater and her mater

For her support she does not lean,

She talks and writes of “Woman’s Rights”

In language forceful and clean.

She does not shirk, but does her work,

Amid the world’s fast hustling whirl,

And come what may, she’s here to stay,

The self-supporting “bachelor girl.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Note to readers: Across the web, Effie Waller Smith is sometimes conflated with Effie Lee Newsome (1885 – 1979), a poet associated with the Harlem Renaissance, and the rare existing photo of Newsome is often used incorrectly to identify Smith.

More about Effie Waller Smith Effie Waller Smith: African-American Appalachian Poetry from the Breaks Wikipedia Notable Kentuckian African Americans Database. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

6 Fascinating African-American Women Writers of the 19th Century

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The “Bachelor Girl” — a Poem by Effie Waller Smith appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 12, 2019

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas by Gertrude Stein (1933)

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas by Gertrude Stein (1933) is actually Stein’s autobiography, written as if in her longtime companion’s voice. Considered one of the most accessible of Stein’s experimental, often ponderous works, it was a commercial and critical success. It is indeed narrated as if Alice is doing the writing, and this comes through in a fresh and vibrant manner.

Some of Gertrude’s colleagues didn’t much care for the book. Some thought it too commercial, as indeed, the author admitted that she cranked it out in six weeks as a way to make money. Ernest Hemingway, to whom Gertrude was a mentor, called it “a damned pitiful book,” and her brother, Leo Stein, who disliked Alice, called it “a farrago of lies.”

The book played with the notion of what an autobiography could be and helped to cement the legacy of its author and, no doubt, Alice B. Toklas as well. Following are two reviews from 1933, the year that this unique book was published.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein in 1908, the year after they first met

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review in the Chicago Tribune, September 2, 1933: “About six weeks ago Gertrude Stein said, ‘It does not look to me as if you were ever going to write that autobiography. You know what I am going to do? I am going to write it for you. I am going to write it as simply as Defoe did the autobiography of Robinson Crusoe.’ And she has, and this is it.”

For years intelligent readers have known of, if now actually followed, the work of Gertrude Stein. No person with any feel at all for modern American literature has missed Three Lives or the “cuttings from it which have been grafted into the literary work of Ernest Hemingway (to name just one of the writers who have been influenced by Gertrude Stein).

From Three Lives Gertrude Stein went on to a more complicated, less assimilable theory of writing, which culminated in the idea that this is an age of the sentence as opposed to previous ages of the paragraph. Much amused and bitter criticism of its obscurity gave Stein’s work the same sort of fantastic praise and blame that was attached to the work of the modern painters (intent upon expressing ideas rather than facts).

For years, everyone, and by everyone I mean everyone who knows about such things, has been trying to get Stein to write her autobiography. The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is Stein’s unique way of answering that cry without giving up her theories of the new forms of writing.

Alice B. Toklas is “a pretty good housekeeper, and a pretty good gardener, and a pretty good needlewoman, and a pretty good secretary, and a pretty good editor, and a pretty good vet for the dogs,” the book says, “and I have to do them all at once and I found it difficult to add being a pretty good author.” So Gertrude Stein wrote her autobiography for her, choosing, in this manner, to actually write her own.

Miss Toklas has been inseparable from Stein since 1907 and in writing the “autobiography” of her constant companion, Stein has been able, in an amusing form, to detail her own life completely. The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is really the autobiography of Gertrude Stein.

No book I have read recently has given me the sheer pleurae in its writing that this book has. It contains the subtlest undercurrent of humor and satire. It is sharp as the edge of a scalpel. Its sentences are often spike upon which are carried the heads of a whole generation’s foibles, sentiments, critical mistakes, and righteousness. It is wise and it is brilliantly cruel, as truth can be.

If one began quoting sentences, one might quote a third of the book. It is all stimulating to the mind of the reader. He or she need not know the work of the artists and writers who fill its pages. He or she needs only to float in the vividly tangy words and to be refreshed about the importance of creative art.

Not that The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is a treatise. It is a record set down with such clarity and rich humanity that it becomes itself a work of creative art.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review in the Des Moines Register, November 5, 1933: Gertrude Stein, an exponent of surrealism, has exerted a profound influence on the growth of the new art, music, and literature during the great revolution in the arts which came in the twentieth century.