Nava Atlas's Blog, page 64

August 15, 2019

25 Wise Quotes by Toni Morrison on Writing and Living

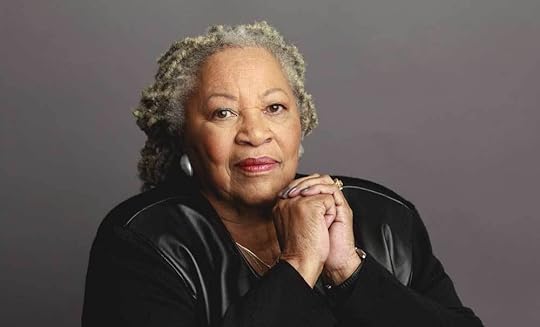

Toni Morrison (1931 – 2019) was an American novelist, editor, essayist, teacher, and professor. She was the recipient of numerous awards, including the Nobel Prize in Literature. Her body of work examined the black experience in America through great storytelling.

Morrison was born and raised in Lorain, Ohio in a working-class African-American family that influenced her love and appreciation for black culture. Growing up, she saw first-hand the horrifying reality of racism in America and used her understanding of racial history to connect it with the present.

Morrison was a great influence on numerous writers, including National Book Award finalist Jamel Brinkley, best-selling author Julia Alvarez, prize-winning poet Saeed Jones, and many more. American author George Saunders said, “There is something about the scale of her work that inspires other writers to think in a more expansive way,” and added, “she inspires with her incredible language and also the moral-ethical intensity of her work.” Here is a selection of wise quotes by Toni Morrison on writing, living, and love.

. . . . . . . . . .

14 Women Who Have Won the Nobel Prize in Literature

. . . . . . . . . .

“When a kid walks in a room, your child or anybody else’s child, does your face light up? That’s what they’re looking for.” – Interview on The Oprah Winfrey Show, 2000

. . . . . . . . . .

“I tell my students, ‘When you get these jobs that you have been so brilliantly trained for, just remember that your real job is that if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else.'” – Interview with O, The Oprah Magazine, November 2003

. . . . . . . . . .

“It is easily the most empty cliché, the most useless word, and at the same time the most powerful human emotion—because hatred is involved in it, too.” – Interview with O, The Oprah Magazine, November 2003

. . . . . . . . . .

“My world did not shrink because I was a Black female writer. It just got bigger.” – Interview with The New York Times, 1987

. . . . . . . . . .

“What I’m interested in is writing without the gaze, without the white gaze … In so many earlier books by African-American writers, particularly the men, I felt that they were not writing to me. But what interested me was the African-American experience throughout whichever time I spoke of. It was always about African-American culture and people — good, bad, indifferent, whatever — but that was, for me, the universe.” – Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah’s profile of Morrison in The New York Times Magazine, 2015

. . . . . . . . . .

“You can do some rather extraordinary things if that’s what you really believe,” – Interview with The New York Times, 1987

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Toni Morrison

. . . . . . . . . .

“I never asked Tolstoy to write for me, a little colored girl in Lorain, Ohio. I never asked Joyce not to mention Catholicism or the world of Dublin. Never. And I don’t know why I should be asked to explain your life to you.” – Interview, 1981

. . . . . . . . . .

“If you find a book you really want to read but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” – Speech to Ohio Arts Council, 1981

. . . . . . . . . .

“If you can’t imagine it, you can’t have it.” – Lecture in Portland, Oregon, 1992

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’m a believer in the power of knowledge and the ferocity of beauty, so from my point of view, your life is already artful—waiting, just waiting, for you to make it art.” – Graduation address at Princeton University, 2005

. . . . . . . . . .

“The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being. Somebody says you have no language and you spend twenty years proving that you do. Somebody says your head isn’t shaped properly so you have scientists working on the fact that it is. Somebody says you have no art, so you dredge that up. Somebody says you have no kingdoms, so you dredge that up. None of this is necessary. There will always be one more thing.” – “A Humanist View,” speech at Portland State University, 1975

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“Your life is already artful—waiting, just waiting, for you to make it art.” – From her Wellesley College Commencement address, 2004

. . . . . . . . . .

“You wanna fly, you got to give up the shit that weighs you down.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If there is a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, you must be the one to write it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Love is or it ain’t. Thin love ain’t love at all.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“In my mother’s church, everybody read the Bible and it was mostly about music. My mother had the most beautiful voice I have ever heard in my life. She could sing anything — classical, jazz, blues, opera. And people came from long distances to that little church she went to — African Methodist Episcopal, the AME church she belonged to — just hear her.” —“‘I Regret Everything: Toni Morrison Looks Back on her Personal Life” – Interview with Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air, 2015

. . . . . . . . . .

“The writing is — I’m free from pain. It’s where nobody tells me what to do; it’s where my imagination is fecund and I am really at my best. Nothing matters more in the world or in my body or anywhere when I’m writing.” – Interview with Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air, 2015

. . . . . . . . . .

Anger … it’s a paralyzing emotion … you can’t get anything done. People sort of think it’s an interesting, passionate, and igniting feeling — I don’t think it’s any of that — it’s helpless … it’s absence of control — and I need all of my skills, all of the control, all of my powers … and anger doesn’t provide any of that — I have no use for it whatsoever.” – Interview on CBS, 1987

. . . . . . . . . .

Former President Barack Obama presenting Toni Morrison

with the Presidential Medal of Freedom

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Toni Morrison’s 2003 interview with The New Yorker

“Being a black woman writer is not a shallow place but a rich place to write from. It doesn’t limit my imagination; it expands it. It’s richer than being a white male writer because I know more and I’ve experienced more.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The title of Ralph Ellison’s book was Invisible Man. And the question for me was ‘Invisible to whom?’ Not to me.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Whatever the work is, do it well—not for the boss but for yourself.”

Quotes from Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Speech

“We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Make up a story … For our sake and yours forget your name in the street; tell us what the world has been to you in the dark places and in the light. Don’t tell us what to believe, what to fear. Show us belief’s wide skirt and the stitch that unravels fear’s caul.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Language alone protects us from the scariness of things with no names. Language alone is meditation.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

The post 25 Wise Quotes by Toni Morrison on Writing and Living appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 13, 2019

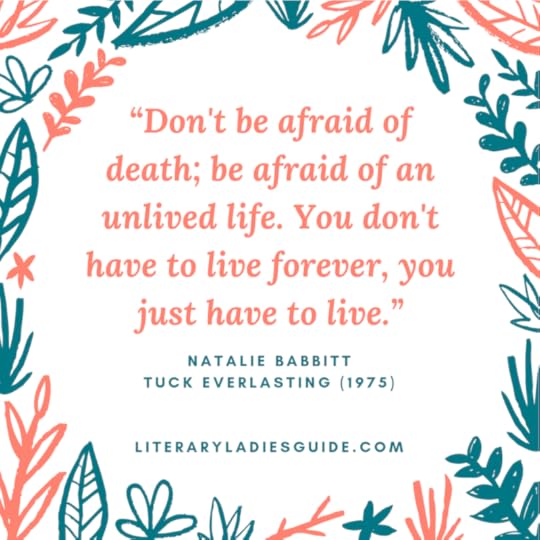

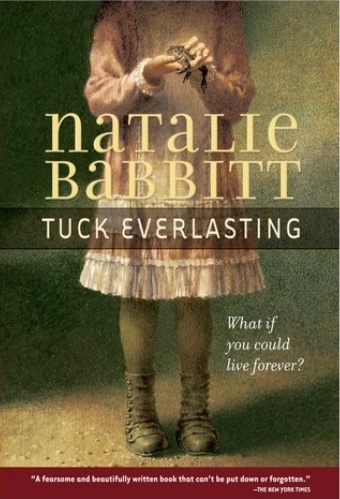

Quotes from Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt

Tuck Everlasting is a 1975 novel by Natalie Babbitt (1932 – 2016) about a young girl who stumbles on a family with an incredible secret. Originally intended for middle grade children, it’s a gracefully written story that has resonated with readers of all ages. It explores the idea of eternal life, and its flip side, mortality. The quotes from Tuck Everlasting that follow demonstrate the book’s charm and thoughtfulness.

When 10-year-old Winnie Foster inadvertently comes upon the Tuck family, she learns that they became immortal when they drank from a spring on her family’s property. They tell Winnie how they’ve watched life go by for decades, while they themselves never grow older. Winnie must decide if she’ll keep the Tucks’ secret, and whether she wants to join them on their immortal path.

The book, from the time of its publication, has been considered a modern classic and has remained the best known of Babbitt’s many works. It was not only filmed twice, it was made into a Broadway musical. The staged production, was, unlike the timeless story, short-lived. Few among us hasn’t pondered the question, what if you could live forever?

Following is a brief description, from the 1975 Farrar, Straus, Giroux edition:

A kidnapping, a murder, a jailbreak. If this were Winnie Foster’s story only, it would be like any other great adventure: you would come to the end, with all resolved, and that would be that. But this is also the story of the Tuck family and therefore, though it has a beginning and a middle, it can never end.

The two stories cross near the village of Treegap during a handful of hot August days in the 1880s, days which are a curious mixture of violence and love, of anguish and tranquility. And when those days are over, young Winnie is left to make a fundamental choice.

What she chooses at last is not what she might have chosen at first. For when you have known the Tucks as Winnie has, however briefly, you can never be quite the same again.

The book begins with the following passage, draws the reader in from this first paragraph:

“The first week of August hangs at the very top of summer, the top of the live-long year, like the highest seat of a Ferris wheel when it pauses in its turning. The weeks that come before are only a climb from balmy spring, and those that follow a drop to the chill of autumn, but the first week of August is motionless, and hot. It is curiously silent, too, with blank white dawns and glaring noons, and sunsets smeared with too much color.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Life’s got to be lived, no matter how long or short. You got to take what comes.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Don’t be afraid of death; be afraid of an unlived life. You don’t have to live forever, you just have to live.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“For some, time passes slowly. An hour can seem like an eternity. For others, there was never enough.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I was having that dream again, the good one where we’re all in heaven and never heard of Treegap.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She was able to believe in this because she needed to; and, believing, was her own true, promising friend once more.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“But dying’s part of the wheel, right there next to being born. You can’t pick out the pieces you like and leave the rest. Being part of the whole thing, that’s the blessing. But it’s passing us by, us Tucks. Living’s heavy work, but off to one side, the way we are, it’s useless, too. It don’t make sense. If I knowed how to climb back on the wheel, I’d do it in a minute. You can’t have living without dying. So you can’t call it living, what we got. We just are, we just be, like rocks beside the road.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“But dying’s part of the wheel, right there next to being born. You can’t pick out the pieces you like and leave the rest. Being part of the whole thing, that’s the blessing.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Like all magnificent things, it’s very simple.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I got a feeling this whole thing is going to come apart like wet bread.”

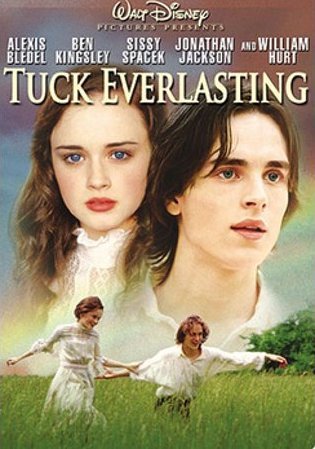

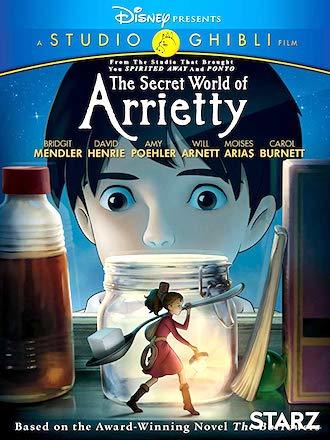

Tuck Everlasting was adapted into a 2002 Disney film

. . . . . . . . . .

“Closing the gate on her oldest fears as she had closed the gate of her own fenced yard, she discovered the wings she’d always wished she had.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The ownership of land is an odd thing when you come to think of it. How deep, after all, can it go? If a person owns a piece of land, does he own it all the way down, in ever narrowing dimensions, till it meets all other pieces at the center of the earth? Or does ownership consist only of a thin crust under which the friendly worms have never heard of trespassing?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“it’s no good hiding yourself away, like Pa and lots of other people. And it’s no good just thinking of your own pleasure, either. People got to do something useful if they’re going to take up space in the world.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I was more’n forty by then,” said Miles sadly. “I was married. I had two children. But, from the look of me, I was still twenty-two. My wife, she finally made up her mind I’d sold my soul to the Devil. She left me. She went away and she took the children with her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

“ … this rowboat now, it’s stuck. If we didn’t move it out ourself, it would stay here forever, trying to get loose, but stuck. That’s what us Tucks are, Winnie. Stuck so’s we can’t move on. We ain’t part of the wheel no more. Dropped off, Winnie. Left behind. And everywhere around us, things is moving and growing and changing. You, for instance. A child now, but someday a woman. And after that, moving on to make room for the new children.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“And then sometimes it comes over me and I wonder why it happened to us. We’re plain as salt, us Tucks. We don’t deserve no blessings—if it is a blessing. And, likewise, I don’t see how we deserve to be cursed, if it’s a curse. Still—there’s no use trying to figure why things fall the way they do. Things just are, and fussing don’t bring changes.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“She had gone away with the Tucks because — well, she just wanted to. The Tucks had been very kind to her, had given her flapjacks, taken her fishing. The Tucks were good and gentle people.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 10, 2019

Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison, born Chloe Ardelia Wofford (February 18, 1931 – August 5, 2019), was an American novelist, editor, essayist, teacher, and professor. She was the recipient of numerous awards, including the Nobel Prize in Literature. Her work examined the black experience, especially the black female experience, in American culture of the past and present.

Morrison was born and raised in Lorain, Ohio in a working-class African-American family. They influenced her immense love and appreciation for black culture as she grew up hearing folktales, songs, and storytelling. Jane Austen and Leo Tolstoy were two of her favorite authors.

First glimpse of racism

As the second oldest of four children, Morrison was well aware of the issues that her family faced because of their race. When her father lived in Cartersville Georgia as a teenager, he witnessed two black businessmen who lived on his street get lynched by white people. Morrison said “He never told us that he’d seen bodies. But he had seen them. And that was too traumatic, I think, for him.”

At the age of two, her house was set on fire by the family’s landlord while they inside because her parents were unable to pay rent. Rather than getting extremely angry, Morrison’s mother simply laughed at the landlord, calling his actions a “bizarre form of evil.” It was from that moment that Morrison became aware of her family’s ability to remain calm and not let racial actions get the best of them.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Education and the start of her career

Morrison became a member of the Catholic church at the age of twelve and chose the baptismal name of Anthony. This led to the use of her nickname, Toni. She earned her degree from Howard University in 1953 and then attended graduate school at Cornell University. After teaching at Texas Southern University for two years, she taught English at Howard University from 1957 to 1964. During this time, she was married to Harold Morrison, an architect from Jamaica who also taught at Howard, and had two children. They divorced in 1964.

In 1965, Morrison began working as a fiction editor at Random House in their Syracuse, New York office. After two years, she transferred to Random House in New York City, becoming the first black woman senior editor of fiction.

In this role, Morrison brought black literature into the mainstream with the compilation of Contemporary African Literature (1972). She discovered the writings of African-American writers that are widely read and respected today, including Angela Davis, Gayl Jones, and Toni Cade Bambara. At the same time, she continued to teach part-time, lecture across the country, and write numerous novels.

Her legendary works

The Bluest Eye (1970) is the story of an African-American girl who dreams of having blue eyes to fit into Western beauty standards. Though it did not sell well at first, it made its way onto the bookshelves of black-studies departments of many colleges which helped boost its sales.

Morrison’s second novel, Sula (1974), examines the various dynamics of friendships and the expectation to conform to a community’s standards. It was extremely popular and was nominated for the National Book Award.

Her third novel was by far the most popular of her early works. Song of Solomon (1977) brought her national praise and won the National Book Critics Circle Award. It was also awarded the Book of the Month Club and an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award.

Tar Baby (1981), her next novel, tells the story of Jadine, a fashion model who is obsessed with her looks and falls in love with a poor drifter who is comfortable in his dark skin. Along with this powerful novel, she also worked on her first play about Emmett Till, Dreaming Emmett, who was murdered by white men in 1955.

In the years to follow, Morrison went on the publish more books that explore issues dealing with race, class, and sex. This next group of books included Beloved (1987), Jazz (1992), and Paradise (1997). While working on these novels, she was also a writer-in-residence at the State University of New York at Stony Brook and then at Albany. She moved to Princeton University in 1989.

While working as a professor at Princeton, she brought out Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992). After creating so many notable books, she was considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

. . . . . . . . . .

Toni Morrison page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

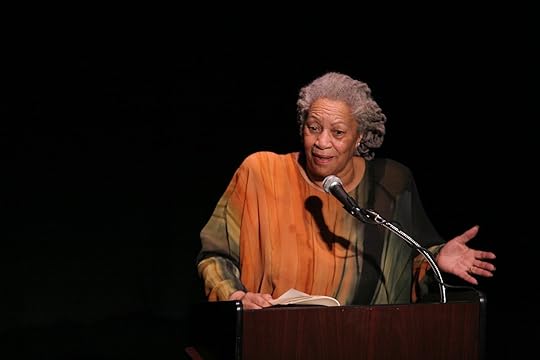

The Nobel Prize in Literature

Morrison was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993, making her the first African-American woman to be selected for the award. Typical of the high praise she received was that she “who in novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality.”

Upon receiving the award, she discussed the power of storytelling and spoke about a blind old black woman who is approached by a group of young people who ask, “Is there no context for our lives? No song, no literature, no poem full of vitamins, no history connected to experience that you can pass along to help us start strong? … Think of our lives and tell us your particularized world. Make up a story.”

. . . . . . . . . .

14 Women Who Have Won the Nobel Prize in Literature

. . . . . . . . . .

Themes in her writing

The central theme of Morrison’s novels is the portrayal of the black American experience. Morrison used her characters to show readers the struggles that black people face, finding themselves and their cultural identity. Her characters seek to understand the unfortunate truth of the world while uncovering love, beauty, friendship, death, and more.

Morrison employed a poetic style and provoke strong emotional responses from her audience. She occasionally included a bit of fantasy to imbue her stories with texture and power.

Other Awards and Honors

In 1979, Morrison was awarded Barnard College’s highest honor, the Barnard Medal of Distinction, during their commencement ceremony.

Beloved (1987), based on the true story of a runaway slave, won a Pulitzer Prize for fiction. A film adaptation of the novel was released in 1998 and starred Oprah Winfrey.

In 1996, Morrison received a Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters from the National Book Foundation.

In 1997, Morrison appeared on the cover of Time magazine. She was the second female writer of fiction and African-American writer to appear on America’s most significant magazine cover of the era.

In 2001, Morrison was given the National Arts and Humanities Award by former President Bill Clinton in Washington, D.C. Upon giving the award, the president said that Morrison had “entered America’s heart.”

In 2005, Morrison won the Coretta Scott King Award for her novel Remember (2004), which delved into the struggles of black students during the time of integration amongst America’s public school system.

Morrison was made an officer of the French Legion of Honour in 2010 and was awarded the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012.

In 2017, Princeton University changed the name of a building, previously known as West College. It was changed to Morrison Hall.

. . . . . . . . . .

Toni Morrison and former President Barack Obama

. . . . . . . . . .

Her final years

In 2011, Morrison worked with directors Peter Sellars, Malian, and Rokia Traoreon on a production called Desdemona, which takes a fresh look at William Shakespeare’s Othello. The production premiered in Vienna in 2011.

When Morrison’s son Slade died, she had stopped working on her latest novel. She decided to start writing again because she thought her son would be upset if he knew that he was the reason she stopped writing. “Please, Mom, I’m dead, could you keep going … ?” she thought he would say. She completed her novel, Home, in 2012 and dedicated it to her son.

On August 5, 2019, the legendary Toni Morrison passed away at Montefiore Medical Center in The Bronx, New York City, from complications of pneumonia. She was eighty-eight years old.

The Legacy of Toni Morrison

As of 2014, Morrison’s papers are part of the permanent library collections of Princeton University, where she worked for seventeen years. Princeton President Christopher L. Eisgruber told those who attended a tribute to Morrison’s legacy:

“This extraordinary resource will provide scholars and students with unprecedented insights into Professor Morrison’s remarkable life and her magnificent, influential literary works. We at Princeton are fortunate that Professor Morrison brought her brilliant talents as a writer and teacher to our campus 25 years ago, and we are deeply honored to house her papers and to help preserve her inspiring legacy.”

Morrison has influenced numerous writers, including National Book Award finalist Jamel Brinkley, best-selling author Julia Alvarez, prize-winning poet Saeed Jones, and many more. When speaking about her work, American writer George Saunders said, “There is something about the scale of her work that inspires other writers to think in a more expansive way,” and added, “she inspires with her incredible language and also the moral-ethical intensity of her work.”

The Pieces I Am, directed by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, is a 2019 documentary on Toni Morrison’s life and powerful works. “I wanted as many people who could hear my voice to understand the importance of her work,” says Oprah Winfrey in the trailer. “Toni Morrison’s work shows us through pain all the myriad ways we can come to love. That is what she does with some words on a page.”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Toni Morrison

Major Works

Novels

The Bluest Eye (1970)

Sula (1973)

Song of Solomon (1977)

Tar Baby (1981)

Beloved (1987)

Jazz (1992)

Paradise (1997)

Love (2003)

A Mercy (2008)

Home (2012)

God Help the Child (2015)

Children’s books (with Slade Morrison)

The Big Box (1999)

The Book of Mean People (2002)

Who’s Got Game? The Ant or the Grasshopper?, The Lion or the Mouse?, Poppy or the Snake? (2007)

Peeny Butter Fudge (2009)

Please, Louise (2014)

Selected short fiction

“Recitatif” (1983)

“Sweetness” (2015)

Plays

Dreaming Emmett (performed 1986)

Desdemona (first performed May 15, 2011, in Vienna)

Libretto

Margaret Garner (first performed May 2005)

Selected nonfiction

Toni Morrison was the editor of several compilations and wrote numerous essays as well.

The Origin of Others (2017)

The Source of Self-Regard: Essays, Speeches, Meditations (2019)

More Information and Sources

Wikipedia

Official site of the Toni Morrison Society

Biography

Notable Biographies

Britannica

Toni Morrison, The Art of Fiction on Paris Review

Obituary in The New York Times

The Legacy of Toni Morrison (by Roxane Gay)

12 Groundbreaking Toni Morrison Books to Read Right Now

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Toni Morrison appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 9, 2019

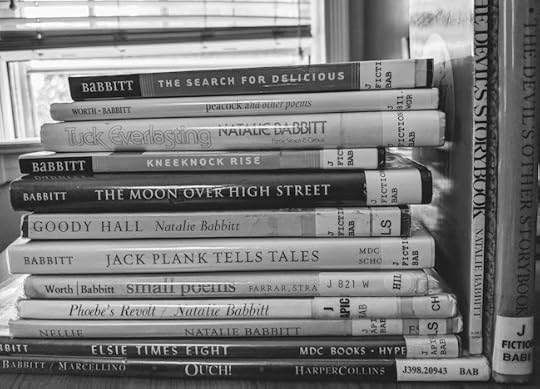

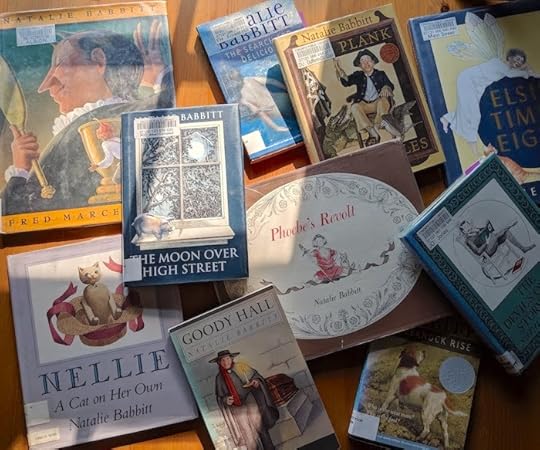

Natalie Babbitt

Natalie Babbitt (July 28, 1932 – October 31, 2016) was an American author and illustrator of children’s books, best known for Tuck Everlasting (1975). Born in Dayton, Ohio, her first ambition was to be a pirate. By second grade, she decided that wanted to grow up to be a librarian.

She discussed her aspirations in Anita Silvey’s The Essential Guide to Children’s Books and Their Creators: “I might have made a pretty good librarian, but with my distaste for heavy exercise, I would probably have made a poor pirate.”

Below-deck or in the stacks, she would have found quiet moments to scribble stories and draw pictures. As an author, she wrote stories about mermaids who swim in the sea, and immortality. As an illustrator, she drew children who hold storybooks close to their hearts.

Upbringing and education

Natalie’s father, Ralph Zane, worked in labor relations and changed jobs many times when the children were young. Natalie recalled (also in Anita Silvey’s volume) that, growing up during the Depression, “there were many things we didn’t have” but “I know now that we had all the things that really matter.”

Her father’s wit and humor had a lasting effect on Natalie. “One of the most valuable things I learned from him,” she wrote in the May-June 1993 issue of The Horn Book Magazine, “was that humor does not trivialize problems. What it does do is relax us and make it easier for us to solve those problems. It puts things in their proper perspective.”

Natalie’s mother, Genevieve Converse Moore was an amateur artist — a landscape and portrait painter, who attended college in an era when that was uncommon for women.

After graduation, Genevieve’s household and parenting duties eclipsed her creative ambitions, but she did expose both daughters to the symphony and the opera, as well as art museums and libraries, and Natalie remembers, fondly, how often her mother read aloud the classics to the girls. Natalie’s love of the classics persisted; as an adult, she continued to read and enjoy the works of Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, and AnthonyTrollope.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

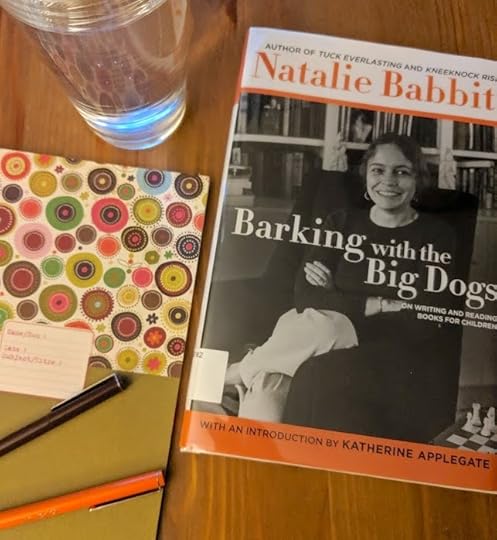

“Books were a normal part of our daily lives, and beyond the list of children’s classics, no one told us we should read such and such, or shouldn’t read so and so. We were entirely unself-conscious about it.” (From her 2018 collection Barking with the Big Dogs: On Writing and Reading Books for Children.)

Natalie’s interest in drawing intensified at the age of nine, after she discovered John Tenniel’s illustrations in a coveted edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. This was also a favorite story because Lewis Carroll never attempted to instruct or moralize.

She describes herself as a “fairly average child” in the aforementioned 1993 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: “Very skinny, but fond of toasted-cheese sandwiches and anything chocolate. By turns confident and scared to death.”

Natalie raced home after school so she could draw and she remembers being captivated by myths and fairy tales while her older sister, Diane, read realistic stories, like Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women.

Her fondest childhood memories revolved around her time in Middletown, Ohio as a student at Lincoln School on Central Avenue, when she was in the fifth grade. When interviewed for the 2007 Square Fish reprints of her classic novels, she identified that time and place as her favored destination using a time-travel device: “And again and again.”

Natalie attended Laurel School for Girls from 1947 –1950, then went on to Smith College in Northampton, MA. She graduated with a B.A. in 1954. She had initially studied theater but soon switched to fine arts.

Stories and books were important throughout her life: “The stories I always liked best were the stories which presented life as it really is: the dark and the light all messed up together, coexisting, with unanswerable questions remaining unanswered, retaining their mystery and their wonder and their endless power to motivate.” (From Barking with the Big Dogs)

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Marriage and family

After graduating from Smith, Natalie married Samuel Fisher Babbitt, on June 26, 1954. He had left Yale, following his sophomore year, to fight in Korea for the U.S. Army, and the couple met after a friend set them up during Natalie’s sophomore year.

Eventually, they would have three children: Christopher Converse (in 1956), Thomas Collier II (in 1958), and Lucy Cullyford (in 1960). Natalie instilled her love of story in her children.

Samuel Babbitt began his career as a professor of American literature with the idea of becoming a novelist. He instead became an administrator at Yale, Vanderbilt, and Brown Colleges. Eventually, he became president of Kirkland College in Clinton, New York, the division of Hamilton College which women attended.

In a 2016 Publishers Weekly article, the story of their relationship is outlined, alongside Natalie’s memory of her later decision to establish a professional identity alongside her work as a wife and mother. In 1964, the feminist movement provided a framework within which Natalie could view her growing sense of frustration and boredom, having abandoned her artistic aspirations.

She credits Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, “a book that reawakened her long-dormant desire to be an artist” and she felt “inspired and empowered by her female friends” to return to work: “By God, I’m going to do what I’ve always wanted to do.”

First publications

It was Natalie who illustrated Samuel Babbitt’s first novel, The Forty-Ninth Magician (1966). She describes the process in Silvey’s compilation, of the husband-and-wife team’s work with Michael di Capua at Farrar, Straus & Giroux, as “natural and preordained.” Much later, in 2017, their son, Tom, produced a short animated film of this novel.

After Samuel shelved his writing ambitions, di Capua encouraged Natalie to work independently. She began by telling stories in verse, beginning with Dick Foote and the Shark (1967). Next, in Phoebe’s Revolt (1968), Phoebe Euphemia Brandon Brown is a spirited girl in 1904 America, who insists on dressing in a more comfortable style than traditional girls’ wear. She resists and, as the title states, revolts:

“And loudly said she hated bows

And roses on her slipper toes

And dresses made of fluff and lace

With frills and ruffles every place

And ribbons, stockings, sashes, curls

And everything to do with girls.”

But as buoyant and entertaining as these characters were, verse stories were more difficult to sell, and di Capua encouraged Natalie to experiment with prose.

Her third book, The Search for Delicious, began as a short picture book but gradually grew into a full-fledged novel and ultimately established her as a fiction writer. “I would have been working in a diner if it wasn’t for Michael,” Natalie said in 2015 in School Library Journal.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Natalie Babbitt page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . . .

Tuck Everlasting

Tuck Everlasting was the book that Natalie Babbitt recommended people read, if choosing just one of her books. But in an interview with Scholastic Books, she said her personal favorite among her books was Herbert Rowbarge, written for women over forty. And her favorite of her books for children was Goody Hall, for the characters and its humor, though she declared it “the one my readers like the least.”

Tuck Everlasting is the story of the Tuck family, who drank water from a mysterious well and from that point on, stopped aging. Winnie, a young girl who lives in isolation with her mother and grandmother, spots a boy drinking from a spring. When she tries to drink from it as well, she is abducted by the kind and gentle Tuck family. From a brief description from a December 23, 1975 review by Elizabeth Coolidge in The Boston Globe:

“Tuck explains to Winnie that never to die puts you outside the wheel of life. ‘dying’s part of the wheel, right there next to being born. You can’t pick out the pieces you like and leave the rest. Being part of the whole things, that’s the blessing. But it’s passing us by, us Tucks.’

Winnie helps them keep the secret in this fascinating story. Natalie Babbit’s great skill is spinning fantasy with the timeless wisdom of the old fairy tales. Tuck Everlasting is a story of death and life, and reading it is like a disturbing dream. You know it isn’t true, yet it lingers on, haunting your waking hours, making you ponder.”

Tuck Everlasting (1975) was adapted twice as a motion picture (first, in 1981 with an age-appropriate Winnie Foster and, next, in 2002 with Alexis Bledel in a Disney production with a 15-year-old version of Winnie) and, more recently, as a stage musical (2015).

Awards and honors

“I became a writer more or less by accident,” Natalie explained in Silvey’s collection. But after shifting into prose, Natalie Babbitt steadily built an impressive body of work.

Natalie was modest about her accomplishments. “Few of us can make anything memorable out of the small commonplaces in the life of an average child, Beverly Cleary being a notable and laudable exception,” she said in Barking with the Big Dogs.

Yet Natalie Babbitt’s Tuck Everlasting altered the landscape of children’s literature. She won a Newbery Honor for Knee-Knock Rise in 1971, a novel which was adapted for film by Miller-Brody Productions in 1975.

She received the George G. Stone Award in 1979 for the body of her work and was the U. S. nominee for the Hans Christian Andersen Medal in 1981. In 2013, she received the inaugural E. B. White Award for achievement in children’s literature.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Natalie Babbitt’s legacy

Winnie struggles with the reality of mortality in Tuck Everlasting: “For she – yes, even she – would go out of the world willy-nilly someday. Just go out, like the flame of a candle, and no use protesting. It was a certainty. She would try very hard not to think of it, but sometimes, as now, it would be forced upon her. She raged against it, helpless and insulted, and blurted at last, ‘I don’t want to die.’”

Natalie Babbitt, too, was mortal, and died of lung cancer, on October 31, 2016, in Hamden, Connecticut. In the January – February 2017 edition of The Horn Book Magazine, her husband, Samuel Fisher Babbitt noted that she “definitely…left her mark in the literary world”, that “her ambition was just to leave a little scratch on the rock” and Tuck Everlasting specifically achieved that goal.

Her Square Fish interview reveals what she wanted readers to remember about her books more generally: “The questions without answers.”

She succeeded, according to critics like Joseph O. Milner, who compared her work to that of Kurt Vonnegut and Wallace Stevens (known for their challenging political and philosophical fiction for adults) in “Hard Religious Questions in Knee-Knock Rise and Tuck Everlasting” in the Winter 1995 issue of Children’s Literature Review.

Author Tim Wynne Jones agreed, in a millennial edition of Horn Book: “I think, a century from now, that Tuck will still have something essential to say about the human condition. And how well it does so, with flawless style, in words that are exact and simple and soothing and right.”

A remarkable legacy indeed.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Natalie Babbitt

Major Works

Self-illustrated verse

Dick Foote and the Shark, 1967

Phoebe’s Revolt, 1968

Self-illustrated fiction

The Search for Delicious (1969)

Knee-knock Rise (1970)

The Something (1970)

Goody Hall (1971)

The Devil’s Storybook (1974)

Tuck Everlasting (1975)

The Eyes of the Amaryllis (1977)

Herbert Rowbarge (1982)

The Devil’s Other Storybook (1987)

Nellie: A Cat on Her Own (1989)

Bub: Or the Very Best Thing (1994)

Elsie Times Eight (2001)

Jack Plank Tells Tales (2007)

Other works

The Big Book for Peace, 1990

Ouch!: A Tale from Grimm (with M.T. Anderson and C. Brown; 1998)

The Exquisite Corpse Adventure: A Progressive Story Game (2011)

The Devil’s Storybooks (2012)

Barking with the Big Dogs: On Writing and Reading Books for Children (2018)

More Information

Wikipedia

Tom Babbitt’s 2015 animated short based on Natalie Babbitt’s The Something (1970)

Reader discussion of Natalie Babbitt’s books on Goodreads

2016 obituary in Publishers Weekly

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Natalie Babbitt appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 6, 2019

Quotes by Natalie Clifford Barney on Life and Love

Natalie Clifford Barney (1876 – 1972) was an American-born poet and novelist also known for her epigrams and pensées. She was an expat living the high life in early twentieth-century Paris where she presided over a famous literary salon. Here you’ll find a selection of quotes by Natalie Clifford Barney on life and love, from a woman who lived and loved to the fullest.

Though she published ten critically acclaimed books, she seems to be equally remembered for her colorful personal life as one of the movers and shakers of the Parisian lesbian circles of the time. She also used the wealth and privilege she was born into as a means of promoting other talented writers and artists.

She most always wrote in French, saying that it allowed her to fully express her emotions, even though English was her native language. Many of her works were based on her own love affairs and friendships, the best known of which is Amants Féminins ou les Troisième (Women Lovers or the Third Woman). This semi-autobiographical novel was one of very few of Barney’s books that were translated into English.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

“If we keep an open mind, too much is likely to fall into it.”

. . . . . . . . .

“It’s necessary to use suffering. Otherwise, one is used by it.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Lovers should also have their days off.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Novels are longer than life.”

. . . . . . . . .

Natalie Clifford Barney with her longtime lover, Renee Vivien

. . . . . . . . .

“When you’re in love you never really know whether your elation comes from the qualities of the one you love, or if it attributes them to her; whether the light which surrounds her like a halo comes from you, from her, or from the meeting of your sparks.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Fatalism is the lazy man’s way of accepting the inevitable.”

. . . . . . . . .

“When she lowers her eyes she seems to hold all the beauty in the world between her eyelids; when she raises them I see only myself in her gaze.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Renouncement: the heroism of mediocrity.”

. . . . . . . . .

“My queerness is not a vice, is not deliberate, and harms no one.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Why grab possessions like thieves, or divide them like socialists when you can ignore them like wise men?”

. . . . . . . . .

“Youth is not a question of years: one is young or old from birth.”

. . . . . . . . .

“It is time for dead languages to be quiet.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Time engraves our faces with all the tears we have not shed.”

. . . . . . . . .

“I have sometimes lost friends, but friends have never lost me.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Paris has always seemed … the only city where you can live and express yourself as you please.”

Learn more about Natalie Clifford Barney

. . . . . . . . .

“I want to be at once the bow, the arrow, and the target.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Entrepreneurship is the last refuge of the trouble making individual.”

. . . . . . . . .

“At first, when an idea, a poem, or the desire to write takes hold of you, work is a pleasure, a delight, and your enthusiasm knows no bounds. But later on you work with difficulty, doggedly, desperately. For once you have committed yourself to a particular work, inspiration changes its form and becomes an obsession, like a love-affair… which haunts you night and day! Once at grips with a work, we must master it completely before we can recover our idleness.”

. . . . . . . . .

“To be one’s own master is to be the slave of self.”

. . . . . . . . .

“There are intangible realities which float near us, formless and without words; realities which no one has thought out, and which are excluded for lack of interpreters.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Most virtue is a demand for greater seduction.”

. . . . . . . . .

“How many inner resources one needs to tolerate a life of leisure without fatigue.”

. . . . . . . . .

“The advantage of love at first sight is that it delays a second sight.”

. . . . . . . . .

Natalie Clifford Barney page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes by Natalie Clifford Barney on Life and Love appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Doris Lessing

Doris Lessing, (October 22, 1919 – November 17, 2013) was a British novelist, playwright, poet, short story writer, and biographer. One of the most revered voices in modern literature, she has written intelligently and passionately about politics, parenting, aging, love relationships, and feminism.

She was born Doris May Tayler in what was then Persia (present-day Iran) to British parents, Captain Alfred Tayler and Emily Maude Tayler. When she was five, her parents moved with her to Rhodesia (what is now Zimbabwe) to farm crops on one thousand acres of land. Observing the strife caused by the British in their colonial rule of the African nation, she developed a strong moral and political compass.

Lessing attended the Dominican Convent High School, a Roman Catholic convent for all girls in the Southern Rhodesian capital of Salisbury (what is now Harare). Afterward, she attended Girls High School in Salisbury and dropped out of school at the age of thirteen. She received no further formal education, though she self-educated from then on.

While still in her teens, she held a number of jobs to piece together a living. She worked at various times as an office worker, nursemaid, and journalist. When at age fifteen she got one of her first jobs as a governess, her employer gave her books on politics and sociology to read. She started writing stories, and not long after, successfully sold two to magazines in South Africa.

Early marriages

Lessing moved to Salisbury in 1937 to work as a telephone operator and met her first husband, Frank Wisdom. She married at age nineteen and soon after had a son, John, born in 1940, and a daughter, Jean, born in 1941. She felt trapped and left the marriage in 1943.

After the divorce, she developed an interest in the Left Book Club. This organization was where she met her second husband, Gottfried Lessing. They married and had their first child, Peter, born in 1946.

The marriage also didn’t last. Three years after the birth of her son, they divorced. During their marriage, she had a love affair with RAF serviceman John Whitehorn, brother of journalist Katherine Whitehorn. He was stationed in Southern Rhodesia and she wrote him about ninety letters between 1943 and 1949.

The start of a writing career

In 1949, Lessing moved to London with her youngest child, leaving her older two children in South Africa with their father. She wanted to pursue her writing career and socialist beliefs. She believed that she couldn’t be a good parent to her children, saying:

“For a long time I felt I had done a very brave thing. There is nothing more boring for an intelligent woman than to spend endless amounts of time with small children. I felt I wasn’t the best person to bring them up. I would have ended up an alcoholic or a frustrated intellectual like my mother.”

Since she was fifteen years old, Lessing sold her stories to various magazines. Her earliest works were African Stories (1948) and Going Home (1949). These semi-autobiographical stories were set in the Africa of her youth, a continent with which she had a love-hate relationship.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: Brilliant Quotes by Doris Lessing

. . . . . . . . . .

The Grass is Singing and The Golden Notebook

With the publication of her first novel, The Grass is Singing (1950), Lessing cemented her foothold as a writer. Semi-autobiographical and somewhat philosophical, the book was an immediate success. Set in Rhodesia, it’s the first of her five-novel series referred to as Children of Violence.

The Golden Notebook (1962) was her breakthrough novel, earning much international attention, especially among feminists. She later became something of an icon and the book is considered a “feminist bible.” The Swedish Academy praised it for being “a pioneering work” that “belongs to the handful of books that informed the twentieth-century view of the male-female relationship.”

Through the eyes of the protagonist, Anna Wulf, The Golden Notebook looks at feminist politics, the writer’s life, and what it means to be female. Anna’s struggles in a patriarchal world struck a chord at a time when second-wave feminism was barley nascent.

A noted science fiction writer

Lessing’s foray into science fiction seemed quite a departure from the political and feminist themes of her other novels, but it was all of a piece. She wove the subjects that she was passionate about into her speculative works as well, notably, the five-book “Canopus in Argos” series.

In Charlie Jane Anders’ 2013 obituary of Doris Lessing in Gizmodo, she wrote:

“Seriously, if you want to write science fiction or fantasy, and you’re interested in learning how to capture the difficult niggly bits of people’s inner lives and their interactions with other people — then you absolutely must read Lessing, both her science fiction and her other stuff. We talk a lot about the importance of world-building in making readers believe in the setting of your story — and Lessing was a master of drawing you into a world and making it feel urgent and real.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Lessing is perhaps still best known for The Golden Notebook

. . . . . . . . . .

Themes of Doris Lessing’s work

Lessing has over fifty books in various different genres. Her writing focuses on the living conditions, behavioral patterns, and historical developments of the twentieth century. Her most famous novel, The Golden Notebook, focuses on a woman’s life situation, sexuality, political ideas, and daily life. Some of Lessing’s works delve into the future as she portrays civilization’s final hour from the eyes of an extraterrestrial observer.

. . . . . . . . . .

14 Women Who Have Won the Nobel Prize in Literature

. . . . . . . . . .

Nobel Prize for Literature

When she won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2007 the jury described her as “that epicist of the female experience, who with skepticism, fire, and visionary power has subjected a divided civilization to scrutiny.”

Lessing was the was the eleventh women and oldest person to receive the award at age eighty-eight. In 2008 The Times put her at number five in the list of “The 50 Greatest British Writers since 1945.”

Doris Lessing long used her platform as an outspoken opponent of apartheid in South Africa, and spoke regularly about the subject. She practiced Sufism, a branch of Islam.

Other awards and honors

In 1971, Lessing was awarded the Man Booker Prize for her work Briefing for a Descent into Hell, published in 1971. She was awarded this prize a second time in 1981 for her science fiction novel, The Sirian Experiments (1980). She was later given the same award in 1985 and 2005 for other works.

In 1977, Lessing declined an Order of British Empire Award, saying the “Empire is non-existent.”

Lessing was awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 1974. She was nominated by American author Joyce Carol Oates. She was awarded the prize again in 1998.

In 1997, Lessing was awarded the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography/Autobiography for her novel, “Walking in the Shade: Volume Two of My Autobiography–1949-1962”.

In 1999, she was appointed the Companion of Honor for “conspicuous national service.” She was named a Companion of Literature by the Royal Society of Literature.

In 2001, Lessing won the Prince of Asturias Award for Literature. Those who gave her the award stated that she was “the creator of an imaginary, everyday world, and her characters, the offspring of contemporary society, are a faithful reflection of twentieth-century morals.”

Other awards Lessing received included the Austrian State Prize for European Literature, The David Cohen Prize, Prince of Asturias Award, and The Golden Pen Award.

The death of a beloved writer

Lessing suffered a stroke in the late 1990s and caused her to stop traveling. Though she was unable to go far, she was still able to attend the theatre and opera. It seemed though she was preparing for her death, asking herself, for instance, if she would be around long enough to finish a new book.

Doris Lessing died on November 17, 2013, at the age of 94 at her home in London.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Doris Lessing

On this site

Dear Literary Ladies: How Do I Become a More Effective Reader?

Brilliant Quotes by Doris Lessing

Major Works

Doris Lessing was incredibly prolific; the list of her work below represents but a fraction of her output, as she wrote a great deal of nonfiction as well.

The Grass is Singing (1950)

Martha Quest (1952, the first of “The Children of Violence” series)

The Golden Notebook (1962)

Briefing for a Descent into Hell (1971)

Memoirs of a Survivor (1974)

The Summer Before the Dark (1973)

The Good Terrorist (1985)

The Fifth Child (1988)

Ben, in the World (2000)

The Sweetest Dream (2001)

The Grandmothers (2004)

Biographies and Autobiographies

Under My Skin: Volume One of My Autobiography, to 1949

Walking In the Shade: Volume Two of My Autobiography – 1949-1962

Doris Lessing: Conversations

Alfred and Emily (a memoir of her parents)

More Information and sources

Wikipedia

The Nobel Prize in Literature in 2007

Reader discussion of Lessing’s books on Goodreads

My Hero: Doris Lessing by Margaret Drabble

Doris Lessing: Her Last Telegraph Interview

Lessing’s Visions of the Future

Lessing Remembered: Provocative, Blunt, Unforgettable

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Doris Lessing appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 2, 2019

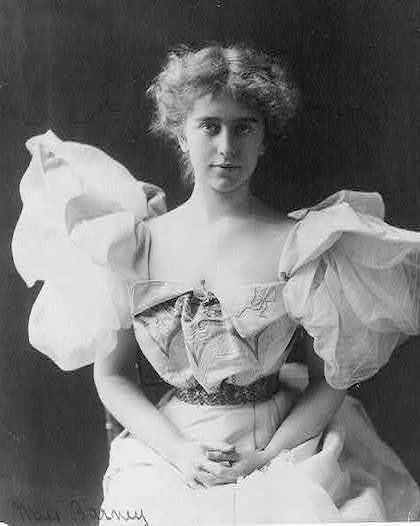

Natalie Clifford Barney

Natalie Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American-born writer of poems, epigrams, pensées and novels. She made her home in Paris, where she was known more for her literary salon and her colorful personal life than her writing, despite publishing ten critically acclaimed books in her lifetime.

She was “the wild girl of Cincinnati,” the grande dame of the literary salon and Parisian lesbian circles, and used her considerable wealth and influence to promote talented writers and artists from around the world.

Early years and work

Natalie was born to privilege. Her parents, Alice Pike Barney and Albert Clifford Barney, were wealthy through a combination of inheritance and private income, and the family had homes in Cincinnati, Ohio; Washington, DC; and Bar Harbor, Maine.

Natalie grew into a confident child, sociable and outgoing, and was naturally athletic with a particular love for riding horses. She was also beautiful, with a mass of pale blond hair that was often likened to moonbeams, sharp blue eyes, and delicate features.

The family often traveled, and from 1888 Natalie attended the exclusive Les Ruches boarding school in France. She was a good student, but later spurned the option of going to college, stating that she preferred education of her own design. She continued to study French, Greek, violin, and literature, seeking out informal and formal tutors who encouraged her ambitions.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

In 1896 she left America to settle in Paris permanently. Writing and socializing were Natalie’s focus during the first years of the new century. She was drawn to shorter forms of writing, particularly poetry and pensées (literally “thoughts” or “fragments”), and always wrote in French, claiming that it was the language in which she could best express her emotion.

Her earlier works are full of love and loss and classical beauty, mostly inspired by her readings of the classical poets — Sappho was a favorite — and her own, already tumultuous, love life.

By 1910 she had published four books: Quelques Portraits – Sonnets de Femmes, Éparpillements, Je Me Souviens, and Actes et Entr’actes. All were published to critical acclaim. However, it was Quelques portraits – sonnets de femmes, a chapbook of love poems to women published in 1900, that garnered the most attention. Reviews ranged from mildly complimentary to gushing (Henri Pene du Bois wrote of Natalie’s “miraculous power to write French verse”), but the fact that they were essentially love letters to women caused great scandal in some circles. Natalie’s father Albert, incensed by a headline that read “Sappho Sings In Washington,” stormed into the publisher’s offices to buy and then destroy the remaining copies and all printing plates. Consequently, the book is incredibly rare today.

Natalie became well-established in the glittering literary and artistic community of the Belle Epoque, and counted Colette, Pierre Loüys, Count Robert de Montesquiou, Lord Alfred Douglas, Jules Cambon, and Remy de Gourmont among her friends.

De Gourmont in particular was a lifelong admirer and promoter of her work. It was he who christened Natalie “The Amazon,” a nickname that would stick. She also continued to write, and Poems & Poèmes: Autres Alliances and Pensées d’une Amazone was published in 1920.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The years of the salonNatalie, perhaps taking after her mother, was a natural hostess. She was sociable, lively, and sharply witty. She also knew how to make people feel at ease, when to relinquish the spotlight, and how to promote others. It was this perfect combination of talents — as well as her own artistic and literary accomplishments — that made her Friday literary salon into arguably the most famous in Paris. It began when she moved into a pavillon at 20 rue Jacob, in the heart of the Left Bank, in 1908, but its heyday was the 1920s.

During these years, Friday afternoons were filled with writers and artists from all over the world. They came for the chance to mingle, to introduce and be introduced, to promote their work and hear the work of others, and to eat the famous chocolate cake. Regular attendees included Colette, Djuna Barnes, Ford Madox Ford, Paul Valéry, Ezra Pound, Mina Loy, and André Germain. Others such as Rilke, T.S. Eliot, Nancy Cunard, Somerset Maugham and Peggy Guggenheim dropped in occasionally.

There were definite standards for admission. Intelligence, artistic accomplishment, celebrity, and, in the case of women, beauty and style — any or all of the above were prerequisites for an invitation. Once there, however, the salon was noted for its inclusivity. Natalie was tolerant and open-minded, and people of all nationalities, religions, and sexual persuasions were welcome.

Natalie used the salon as a way of assisting those who were struggling financially, and she gave generously to individuals who she felt were worthy of her input. She also promoted tirelessly, particularly the work of women which, at the time, was generally not taken as seriously.

Her 1927 Académie des Femmes was a response to the all-male bastion of the Académie Française, and harked back to an earlier ambition of establishing a community of women poets on the island of Lesbos. Women writers were honoured with their own Friday at the salon, during which they would read from unpublished works or works in progress. The Académie included Colette, Gertrude Stein, Djuna Barnes, Mina Loy, Elisabeth de Gramont and Lucie Delarue-Mardrus. Although it faded away after 1927, it remained one of Natalie’s greatest achievements.

The salon ran — with a break over the years of the Second World War — almost until Natalie’s death, and was probably her most lasting and best known legacy.

Love affairs served as inspirationNatalie was known for being a lesbian. Even in Paris, where attitudes were relatively tolerant for the time, her complex love life and her refusal to hide it brought her even more attention than the salon, and certainly more than her writing. Her approach can be summed up in her own words: “I am a lesbian. One need not hide it, or boast of it.”

She was also never monogamous, and her long term relationships — first with the poet Renée Vivien, and later with the artist Romaine Brooks and Elisabeth (Lily) de Gramont — were conducted against a continual backdrop of affairs, some more serious than others.

Natalie was as steadfast in friendship as she could be fickle in love, once claiming to be a lazy friend because “once I confer friendship, I never take it back.” Many lovers became close friends — close enough to immortalize Natalie in their works without offense being taken.

Natalie could be clearly seen as the main character in books by Liane de Pougy (Idylle Saphique), Djuna Barnes (Ladies’ Almanack) and Lucie Delarue-Mardrus (L’Ange et les Pervers).

Many of Natalie’s own works were based on her love affairs and friendships, including Aventures de l’Esprit (published in 1929 and containing reflections on her salon friendships) and the astonishing novel Amants Féminins ou les Troisième (translated into English by Chelsea Ray as Women Lovers or the Third Woman, an account of a three-way relationship with Liane de Pougy and Mimi Franchetti that ended in heartbreak for Natalie).

. . . . . . . . . .

Natalie Clifford Barney page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

In the years immediately preceding the war, Natalie continued to write and publish her own work, run the salon, and socialize. She also traveled widely, settling into a seasonal routine of spending the winter with Romaine on the Côte d’Azure, the autumn in Romaine’s home above Florence, and taking trips to spas in France and Switzerland in between with Lily.

In 1930, her novel The One Who Is Legion was published — a strange, surreal account of a person who, having committed suicide, is brought back to life as a genderless being with no memory. Natalie herself claimed that it came from “the several selves … their conflicts and harmonies” that she felt she possessed. It was the only work that she published in English.

Natalie saw out the war in Florence with Romaine, and did not return to Paris until 1946. The house at rue Jacob was uninhabitable, and it was a further three years before she could move back in and recommence the Friday salons.

Other post-war projects included reestablishing the Prix Renée Vivien for women poets writing in French; and the private funding of three books which commemorated Dolly Wilde and Lucie Delarue-Mardrus. She also started work on her memoirs, which would later be published in 1960 as Souvenirs Indiscrets.

The amazon’s last Friday

Natalie never stopped writing, and her last book, Traits et Portraits, was published in 1963 when she was eighty-six. Her personal life, too, was no less vibrant. Her long relationship with Romaine finally ended when both were almost 90, at which time Natalie met and fell in love with the much younger Janine Lahovary. Janine would be Natalie’s last love and also her carer in her final years, but the split with Romaine — who Natalie thought of as the love of her life — devastated Natalie.

She also endured the loss of the house at rue Jacob, having rented it for almost 60 years, when it was suddenly bought and an eviction notice served. Natalie spent her last months in the Hôtel Meurice, overlooking the Tuileries Gardens, increasingly infirm with the effects of old age. She died in February 1972 — on a Friday — at age ninety-five, and was buried in Passy Cemetery in Paris.

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is an author, poet and artist with a serious case of wanderlust. She is originally from the UK, but has spent time abroad in Europe, the United States and the Bahamas. When not traveling or working on her current projects — a chapbook of poetry, “The Cabinet of Lost Things,” and a novel based on the life of modernist writer and illustrator Djuna Barnes — she can be found with her nose in a book, daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris.

More about Natalie Clifford BarneyMajor works

Most of Natalie Barney’s major works were originally published in French:

Quelques Portraits-Sonnets de Femmes (1900)Cinq Petits Dialogues Grecs (1901)Actes et entr’actes (1910)Je me souviens (1910)Eparpillements (1910)Pensées d’une Amazone (1920)Aventures de l’Esprit (1929)Nouvelles Pensées de l’Amazone (1939)Souvenirs Indiscrets (1960)Traits et Portraits (1963)Amants féminins ou la troisième (2013)English translations

Women Lovers, or the Third WomanA Perilous Adventure: The Best of Natalie Clifford BarneyBiographies

Adventures of the Mind: The Memoirs of Natalie Clifford Barney (1992)Wild Heart, A Life by Suzanne Rodriguez (2003)More information

Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads Natalie Clifford Barney: Queen of the Paris Lesbians Barney’s setting in Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party A Natalie Barney Garland on the Paris Review. . . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Natalie Clifford Barney appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 1, 2019

Empowering Quotes by Ntozake Shange

Ntozake Shange (1948 2018) was an African American playwright, poet, and feminist. She is best remembered for her 1975 Obie Award-winning choreopoem, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow is Enuf.

Born in Trenton, New Jersey, she was the oldest of four children in an upper-middle-class family. She attended a white school where she endured racial attacks to receive a “quality” education. Shange’s family pushed her to find an artistic outlet which was how she discovered her love for poetry.

Heartbreak and racial attacks were influences in her work, which spans several genres addresssing injustice, violence, and oppression. Though her choreopoems have been criticized for using African American dialect and one-sided attacks on black men, many value her work for its flair and lyricism. Here are empowering quotes by Ntozake Shange, a valiant and unapologetic talent in the world of fiction, poetry and theater.

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Sassafras, Cypress & Indigo (1982)

“Where there is a woman there is magic. If there is a moon falling from her mouth, she is a woman who knows her magic, who can share or not share her powers. A woman with a moon falling from her mouth, roses between her legs and tiaras of Spanish moss, this woman is a consort of the spirits.”

“The slaves who were ourselves had known terror intimately, confused sunrise with pain, & accepted indifference as kindness.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Creation is everything you do. Make something.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow is Enuf, 1975

“Through my tears I found god in myself and I loved her fiercely.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“i usedta live in the world really be in the world free & sweet talkin good mornin & thank-you & nice day uh huh i cant now i cant be nice to nobody nice is such a rip-off regular beauty & a smile in the street is just a set-up”

. . . . . . . . . .

“And this is for Colored girls who have considered suicide, but are moving to the ends of their own rainbows.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I started writing because there’s an absence of things I was familiar with or that I dreamed about. One of my senses of anger is related to this vacancy — a yearning I had as a teenager … and when I get ready to write, I think I’m trying to fill that.”

. . . . . . . . . .

” … with no further assistance & no guidance from you

i am endin this affair

this note is attached to a plant

i’ve been waterin since the day i met you

you may water it

yr damn self”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Ever since I realized there waz someone callt/

a colored girl an evil woman a bitch or a nag/

i been tryin not to be that & leave bitterness/

in somebody else’s cup…”

. . . . . . . . . .

“somebody/ anybody sing a black girl’s song bring her out to know herself to know you but sing her rhythms carin/ struggle/ hard times sing her song of life she’s been dead so long closed in silence so long she doesn’t know the sound of her own voice her infinite beauty she’s half-notes scattered without rhythm/ no tune sing her sighs sing the song of her possibilities sing a righteous gospel let her be born let her be born & handled warmly.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Being alive and being a woman is all I got, but being colored is a metaphysical dilemma I haven’t conquered yet.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“my spirit is too ancient to understand the separation of soul & gender.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Ntozake Shange page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes by Ntozake Shange from other works & interviews

“Right now being born a girl is to be born threatened.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I write for young girls of color, for girls who don’t even exist yet, so that there is something there for them when they arrive. I can only change how they live, not how they think.” – “Back at You,” Interview with Rebecca Carroll, 1995

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’m a firm believer that language and how we use language determines how we act, and how we act then determines our lives and other people’s lives.” – “Shange’s Men: For Colored Girls revisited, and Movement Beyond,” Interview with Neal A. Lester, 1992

. . . . . . . . . .

“our dreams draw blood from old sores.” – “Spell number seven,” 1985

. . . . . . . . . .

“I am gonna write poems til i die and when i have gotten outta this body i am gonna hang round in the wind and knock over everybody who got their feet on the ground.” – “Advice,” “Nappy Edges,” 1979

. . . . . . . . . .

“When I die, I will not be guilty of having left a generation of girls behind thinking that anyone can tend to their emotional health other than themselves.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I’m committed to the idea that one of the few things human beings have to offer is the richness of unconscious and conscious emotional responses to being alive … The kind of esteem that’s given to brightness/smartness obliterates average people or slow learners from participating fully in human life, particularly technical and intellectual life. But you cannot exclude any human being from emotional participation.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Our society allows people to be absolutely neurotic and totally out of touch with their feelings and everyone else’s feelings, and yet be very respectable.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“When words & manners leave you no space for yourself

make

very personal

very clear

& your obstructions will join you or disappear.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I hit my head against the wall because I don’t want to know all the terrible things that I know about. I don’t want to feel all these wretched things, but they’re in me already. If I don’t get rid of them, I’m not ever going to feel anything else.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“one thing I don’t need is any more apologies i got sorry greetin me at my front door you can keep yrs i don’t know what to do wit em they don’t open doors or bring the sun back they don’t make me happy or get a mornin paper didn’t nobody stop usin my tears to wash cars cuz a sorry.” – “Sorry”

. . . . . . . . . .

“in our ordinaryness we are most bizarre.” – “Combat Breathing”

. . . . . . . . . .

“nice is such a rip-off.” – Plays from the New York Shakespeare Festival, 1986

. . . . . . . . . .

“Novels allow me to create a whole world.” – “AT HOME WITH/Ntozake Shange; Native Daughter,” Interview with Kimberly J. McClarin, 1994

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Empowering Quotes by Ntozake Shange appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans (1925)

In 1925, Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans: Being a History of a Family’s Progress was published, though the author had finished it many years earlier. It was quite a task to find a publisher for it, and so it languished until the inscrutable author had her first major commercial success with The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas — a memoir that Gertrude Stein (1874 – 1946) not Alice, had actually written.

The Making of Americans is considered a modernist novel covering the history, progress, and genealogy of the fictional Herlsand and Dehning families. It’s written in Stein’s inimitable and experimental style, one that requires much patience, as it is steeped in excruciating detail and heavy repetition. In a March 1934 review of The Making of Americans in The Capital Times, the critic captures the difficulties and pleasures of the novel:

“The style is confusing until you get used to it. The words and sentence structures are simple enough yet the odd phrasing and unique combinations of words, the driving repetitions are upsetting to a reader who is accustomed to having things move along in the orthodox fashion.

Yet if you have patience to stick with it, you’ll begin to realize that by this method Gertrude Stein is able to give the reader a sense of human relationships and emotions which are ordinarily intangible and almost impossible to characterize in straightforward prose.

She has said of her own writing that people may not like it, but that her sentences ‘get under their skin.’ And if you’ll subject yourself to an hour or two of Gertrude Stein you will find that this is true.

Don’t try Tender Buttons or Useful Knowledge, which couldn’t possibly make sense for anyone except the person who wrote them, and even that is dubious, but read Three Lives or The Making of Americans, then try to write anything and you’ll find that the Stein Rhythms and repetitions have gotten into your blood. It’s easy to see why she’s so great an influence upon young writers.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Tender Buttons: Experiment in Cubist Poetry, or Literary Prank?

. . . . . . . . . .

The following analysis of The Making of Americans is excerpted in part from Gertrude Stein: Her Life and Work by Elizabeth Sprigge (1957):

“It is a wonderful thing as I was saying and as I am now repeating, it is a wonderful thing how much a thing needs to be in one as a desire in them how much courage any one must have in them to be doing anything if they are a first one.”

There Gertrude Stein sat, making her enormous sentences, a democrat of language, using simple everyday words with a reformer’s urge to emancipate them from the fetters of tradition, association, rhetoric, grammar, and syntax:

She knew them intimately, carried them about with her to caress and meditate upon, “every word I am ever using in writing has for me very existing being,” and each time she found herself using a new one she was disturbed, as when a stranger joins a circle of old friends.

This passion for words was balanced now by her interest in human character, but it could transcend everything. Then words became coins not to be spent in mere meaning, jewels not set for ordinary wear, and she defeated her democratic intention.

And sometimes hypnotized herself, for she had, as she said, a great deal of inertia and did sometimes “stay on with her own methods” because of the pleasure they gave her … What an extraordinary mixture Gertrude Stein was of vitality fired by the creative struggle, rebelliousness upsetting the comfortable order of things, and an inertia making her unwilling to more from where she was to change what she was doing.

The Making of Americans, The History of a Family in Progress is a stupendous achievement, packed with riches. The matter and method of presenting it were new and important, but the reader is usually defeated by the sheer quantity of words.

Working from charts and diagrams begun at Radcliffe, she started a history “of every one who ever can or is or was or will be living,” in “a space of time that is always filled with moving” — a conception she considered typically American.

. . . . . . . . . .

Gertrude Stein sometime around her college years

. . . . . . . . . .

One thinks of the cinema, and though Gertrude Stein had not then seen a film, in Lectures in America thirty years later she observed, “any one is of one’s period and this is our period was undoubtedly the period of the cinema and series production.”

She was aware that she had set herself a tremendous task, but she felt it a charge since she had a key to the “bottom nature of men and women.”

“When I was working with William James,” she explained later, “I completely learned one thing, that science is continuously busy with the complete description of anything with ultimately the complete description of everything.”

So, courageously, she went to it, manipulating language to express the discovery that “every one is always repeating the whole of them.” There could be, she saw, false repeating, when people went on copying their own or somebody else’s kind of repeating because they were too indolent “to really live inside them their repeating,” but true repeating, which she always found in children, truly expressed a person’s “being existing.”

Repetition could irritate even her who loved it, “loving repeating is one way of being” and it could take a very long time to achieve a complete understanding of a character in this way, “to feel the whole of anyone from the beginning to the ending.” But when this happened, the long labor was rewarded.

For this was her aim, as she explained in her lecture “The Gradual Making of Making of Americans,” to “put down a whole human being felt at one and the same time.”

She was continually discovering more things that had to be said about people and restarting was part of the fugal method, many sentences opening with “To begin then again,” or “As I was saying …”