Nava Atlas's Blog, page 62

October 24, 2019

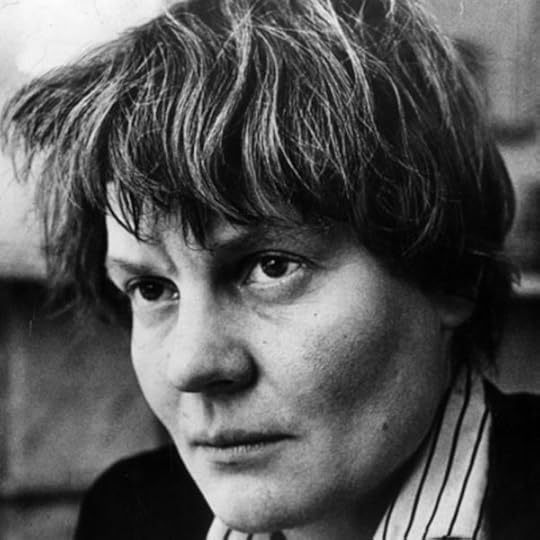

Iris Murdoch

Dame Iris Murdoch (July 15, 1919 – February 8, 1999), the prolific British novelist, philosopher, and playwright was a master of blending psychological depth into darkly comic works.

Born Jean Iris Murdoch in Dublin, Ireland, her father was a World War I veteran and civil servant. Her mother was a former singer. When Murdoch was a newborn, her family moved to London so her father could take a British government position. She remained an only child.

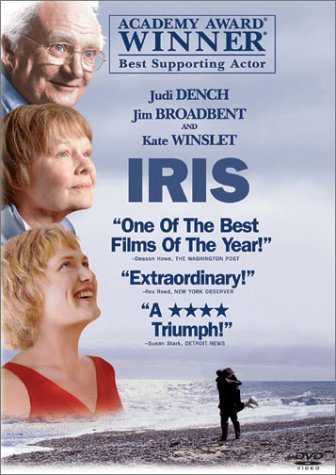

The 2001 Academy and BAFTA Award-winning film Iris is based on her life and marriage to John Bayley, a writer and English professor.

In a 1990 interview with The Paris Review, Murdoch praised her family as a “felicitous trinity” though she knew her mother gave up singing professionally for marriage. She also said, “I knew very early on that I wanted to be a writer. I mean, when I was a child I knew that.” Recognition that her mother’s ambition was subsumed to the time’s gender norms likely fueled Murdoch to achieve.

A life of learning and letters

Early academic prowess set the stage for Murdoch’s impressive career. She attended boarding school in Bristol, then studied the classics and philosophy at Somerville College, Oxford, and Newnham College, Cambridge. She turned down the chance to study at Vassar College in upstate New York out of allegiance to the Communist Party of Great Britain. In The Paris Review interview referenced above, she described how her ambitions were derailed by World War II:

“When I finished my undergraduate career I was immediately conscripted because everyone was. Under ordinary circumstances, I would very much have wanted to stay on at Oxford, study for a Ph.D., and try to become a don. I was very anxious to go on learning. But one had to sacrifice one’s wishes to the war. I went into the civil service, into the Treasury where I spent a couple of years. Then after the war I went into UNRRA, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Association, and worked with refugees in different parts of Europe.”

Murdoch met John Bayley at Oxford. The two married in 1956. She defied convention by remaining childless. Her successful career, use of her maiden name, and publicized open marriage made Murdoch an unwitting symbol of progressive womanhood for second wave feminism.

While at university, Murdoch came into brief but influential contact with prominent thinkers like Jean Paul-Sartre and Wittgenstein. Later, she was romantically linked to the Nobel Prize-winning author Elias Canetti.

She later lectured in philosophy at St. Anne’s College, Oxford. Murdoch’s brief dedication to Communism complicated her visits to the U.S. even after she left the party.

. . . . . . . . .

Photo: Steve Brodie

. . . . . . . . . .

Themes and literary import of Murdoch’s works

Murdoch bloomed as a novelist in her mid-thirties. After she published several nonfiction works, including the first scholarly text written in English on Jean-Paul Sartre (Romantic Rationalist, 1953), she wrote Under the Net (1954). This first novel set Murdoch on the path to writing twenty-five more.

Murdoch’s acclaim for fiction eclipsed appreciation of her philosophical work. However, her novels’ precise psychological character studies and fixation on moral responses in cerebral plot lines alluded to her philosophical training.

In an appreciation of Iris Murdoch in the New York Times’ Enthusiast column, Susan Scarf Merill suggests where to start as a newcomer to her works:

“The Severed Head [Murdoch’s fifth novel] is an excellent place to start. Married man with mistress discovers wife is leaving him for their psychoanalyst. Everyone is so concerned for everyone else — husband and wife help each other move, the analyst’s sister (also his lover, it turns out) sticks her nose in everywhere, and by the end, each character has a new partner and it seems that the world has reshuffled into better order, at least for the moment. Madcap as it sounds, it’s calm on the page. Murdoch’s prose is elegant, validating itself by its own certainty.”

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Awards and Honors

Murdoch is one of the most decorated British novelists of all time. Some of her honors include The Booker Prize for The Sea, The Sea (1978), the Whitbread Literary Award for Fiction for The Sacred and Profane Love Machine (1974), and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for The Black Prince (1973).

She received the Booker Prize for her novel The Sea, The Sea (1978). Several of her novels were adapted to film. Her novels The Bell (1958), A Severed Head (1961), An Unofficial Rose (1962) and The Sea, The Sea were adapted to television series or films.

She received honorary membership to both the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1987, she was appointed a Dame of the British Empire.

Final years and Alzheimer’s

Murdoch became afflicted with Alzheimer’s. She slipped into relative reclusiveness but continued to write. Her last novel, Jackson’s Dilemma (1995), was appreciated for how its simple language and lack of hard editing deterred from Murdoch’s signature style, but demonstrated the effects of Alzheimer’s on creativity.

John Bayley documented Murdoch’s later life struggles in his 1999 memoir Elegy for Iris. Her New York Times obituary reported that Bayley was at his wife’s bedside when she died at the age of 79 in Oxford, England, in February 1999.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Iris (2001 film) and cultural resurgence

Actress Kate Winslet portrayed a young Murdoch to Dame Judi Dench’s older Murdoch in the 2001 biopic Iris. The film focused on Murdoch’s youthful intellectual prowess and complicated marriage.

Jim Broadbent, who played John Bayley, received an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance. Dench won a BAFTA Award for Best Actress for hers. The film introduced Murdoch to a new generation of literary enthusiasts and fans.

In 2019, The Guardian ran a retrospective marking the reissue of all twenty-six of her novels in what would have been the year Murdoch turned 100. The article called her invented people “shapeshifters,” and praised her abilities to confront “the terrifying truth that human beings, in the absence of God, are off the leash.”

More about Iris Murdoch

Major Works

The source for this bibliography is Centre for Iris Murdoch Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Kingston University, U.K.

Fiction

Under the Net (1954)

The Flight from the Enchanter (1956)

The Sandcastle (1957; short stories)

Something Special (1957)

The Bell (1958)

A Severed Head (1961)

An Unofficial Rose (1962)

The Unicorn (1963)

The Italian Girl (1964)

The Red and the Green (1965)

The Time of the Angels (1966)

The Nice and the Good (1968)

Bruno’s Dream (1969)

A Fairly Honourable Defeat (1970)

An Accidental Man (1971)

The Black Prince (1973)

The Sacred and Profane Love Machine (1974)

A Word Child (1975)

Henry and Cato 1976)

The Sea, the Sea (1978)

Nuns and Soldiers (1980)

The Philosopher’s Pupil (1983)

The Good Apprentice (1985)

The Book and the Brotherhood (1987)

The Message to the Planet (1989)

The Green Knight (1993)

Jackson’s Dilemma (1995)

Philosophy

Sartre: Romantic Rationalist (1953)

The Sovereignty of Good (1970)

The Fire and the Sun (1977)

Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals (1992)

Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature (1997)

Plays

A Severed Head (with J.B. Priestley, 1964)

The Italian Girl (with James Saunders, 1969)

The Three Arrows; The Servants and the Snow (1972)

The Servants (1980)

Acastos: Two Platonic Dialogues (1986)

The Black Prince (1987)

Poetry

A Year of Birds (1978; revised edition, 1984)

Poems by Iris Murdoch (1997)

Biographies

Iris Murdoch: A Life by Peter J. Conradi (2002)

Iris Murdoch: As I Knew Her by A.N. Wilson (2003)

Iris: A Memoir of Iris Murdoch by John Bayley (2012)

Iris Murdoch: A Centenary Celebration by Miles Leeson (2017)

More information and sources

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Iris Murdoch’s works on Goodreads

1990 interview in The Paris Review

Iris Murdoch at 100 in The Guardian

Iris Murdoch archive at the National Archive, UK

The Secrets of Iris Murdoch’s and John Bayley’s Unconventional Marriage

. . . . . . . . . .

Iris Murdoch page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Iris Murdoch appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 17, 2019

Gene Stratton-Porter

Gene Stratton-Porter (born Geneva Grace Stratton, August 17, 1863 – December 6, 1924) was an American author, photographer, naturalist, artist, and filmmaker. Among her best known books are Freckles, Girl of the Limberlost, and The Harvester.

Many of her novels are ostensibly aimed at younger readers, but they can be enjoyed by “children of all ages,” much in the way that the Anne of Green Gables books (which were published in the same era) can be.

Born in Lagro, Indiana, into a family with eleven other siblings, Geneva, who was later referred to as Gene, spent most of her time roaming the fields and forests of her family’s farm, catching butterflies and moths, and observing birds and small animals.

Her outdoor exploration was encouraged by her parents, and both her father and mother taught her how to glean all she could from her surroundings. All of her time spent outdoors would lay the foundation of her career as a naturalist, photographer, and writer.

An early affinity with the natural world

Disliking school for most of her high school years, she quietly quit her senior year, frustrated with its rigidity. She recalled how teachers never “made the slightest effort to discover what I cared for personally, what I had been born to do.” She was tired of spending time on mathematics and geometry when she longed to be in the wilds of the forest, learning through real-life experiences and doing what she loved most.

After a year spent recovering from an injury, Gene accepted a friend’s invitation to Sylvan Lake, in Rome City, Indiana. She spent a portion of her time attending a Chautauqua show — bird watching, row-boating, and fishing. She also observed how young women her age were not in touch with nature, and were even afraid of it.

The domestic life that called to these young women did not entice Gene. She found her outdoor world to be more life-giving than embroidery, painting and other domesticities of the era. She hoped that one day she might entice these women to broaden their minds with the natural world around them: “I came in time to believe there might be a lifework for one woman in leading these other women back to the forest.”

Marriage and children

Eventually, Gene did catch the eye of a man, Charles Porter, an entrepreneur and drug store owner. He began to court her via handwritten letters, which continued for over a year. Gene was candid about her lack of domestic skills. “I made some cookies and they were not fit to eat!,” and “I don’t like housekeeping by any means, but if I have to do it I mean to march it through.” As marriage began to come up in conversation, Gene wrote in a letter to Charles, dated September 1885:

“…How can any woman be bright and cheerful when a husband would lay on a girl’s shoulders the management and planning of a house, then have her cook, wash, bake, iron, scrub, make up beds, sweep, and dust.”

Her frankness did not deter Charles, and a month later the two were engaged. The Porters began married life in Decatur, Indiana, where Charles’ second drug store was located. After the couple had their first and only child, Jeannette, Gene pressed Charles to move to Geneva, Indiana. She longed to be near nature again after a busy, crowded city life.

One might think that Gene became rather domesticated in her home in Geneva. She spent her days with little Jeannette, taking care of her birds, perfecting her musical interests, painting china, taking classes in embroidery, and organizing a ladies’ literary club.

After experiencing the Columbian World’s Fair in Chicago with Charles, Gene desired a real home of their own, a house inspired by the architecture she had seen displayed at the Fair. In 1894, Gene worked with an architect to design the new Porter homestead. A lovely cedar home was constructed, with redwood shingles, a colonnaded porch, white oak flooring and mahogany furniture throughout. Finally, Gene felt her empire had been created.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Discovering the Limberlost

It wasn’t long before Gene began to explore her surroundings and discovered what the local Genevans called “The Limberlost Swamp.” The Limberlost, only one mile from her home, would become Gene’s haven, the place she’d longed to find, which opened her up to a world of nature study, photography, and writing. A trip to this deep forest was, as Gene wrote later:

“ … not be joked about. It had not been shorn, branded, and tamed. There were most excellent reasons why I should not go there … In its physical aspect, it was a treacherous swamp and quagmire filled with every plant, animal, and human danger known … in the Central States.”

The trees and brush were thick, nearly impassable in places. In the summer, mosquitoes swarmed, poisonous snakes lurked, and oozing mud made hiking a slow and arduous trek. Gene saw birds she had never dreamed of before: scarlet tanagers, cedar waxwings, yellowhammers, goldfinches, red-winged blackbirds and blue herons. Butterflies, moths, and wildflowers also drew Gene to this magnificent cathedral of color.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

An observer and recorder of birds

Observing, photographing, and sketching birds, Gene learned the differences between species — how some birds like the baby grosbeaks and finches, had to be convinced by their parents to fly, while warblers and thrushes didn’t need coaxing, and robins and larks had to be taught how to forage for food. Gene gave her full attention and time to observing and waiting for the right moment to take a picture. She explained:

“I have reproduced birds in moments of fear, anger, in full tide of song, while dressing their plumage, taking a sunbath, courting, feeding their young. The recipe for such studies is: Go slow, know the birds and understand them, and remain in the woods until … they will be perfectly natural in your presence.”

Gene’s photographs even drew the attention of a manufacturer of photographic print paper at one point, who sent a representative to her home to observe how she achieved her results. She told the representative that the chemicals in the Indiana water probably contributed to her success, sheepishly leaving out the fact that she processed her own film in her bathroom. Gene eventually came to believe her photographs were superior to John James Audubon’s famous sketches.

Gene’s home was an oddity, for at any given time butterflies, birds, insects, and small animals roamed freely indoors. Her lush conservatory served as a perching place for birds, while curtains and furniture were home to cocoons and butterflies. This was her observatory, her venue for learning when she could not be found in the swamp. She and her family coexisted with these curious creatures and they abided as willing guests.

Stepping into a writing career

Gene Stratton-Porter first made writing waves in an outdoor magazine, Outdoor Recreation, during the late 1890s, in response to a popular fad among women: the wearing of stuffed birds on their hats. She was so opposed to this idea that once, while trying to find a hat without a bird, she visited four different shops before she finally purchased a hat containing birds, which she promptly cut off with the storekeeper’s scissors.

She encouraged women to choose hats made with peacock feathers and ostrich plumes, both of which could be collected without harming the birds. From that point on, Gene was published in various magazines and newspapers across the country, including the Metropolitan (New York City).

A short story sent to the editor of Century Magazine was so well received that he encouraged Gene to expand the story into a novel. The Song of the Cardinal (1903) was her first published novel, with her own illustrations. The story was inspired by a personal experience of hers, which involved giving a proper burial to a redbird that she assumed had been killed for target practice.

She hoped to spread the word about the evils of senseless killing of cardinals and birds in general. Though the book received warm reviews and readers enjoyed its contents, sales were slow and limited in circulation.

. . . . . . . . . .

Gene Stratton-Porter page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . .

A prolific author and filmmaker

Gene knew she would need to write more, and faster, if she was to gain a following and educate others about preserving and cherishing nature. Her next novel, Freckles (1904), blended romance with the love of the outdoors as a way to capture a wider range of readers. Receiving a better reaction, Gene continued to write similar stories, combining all that she loved about nature with human interest.

Through the coming years, Gene wrote numerous novels, nature books, and volumes of poetry. Of these, her most famous, The Harvester (1911), rose to number one on the bestseller list. Also among her writing credits were numerous articles in The Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and McCall’s, as well as several lesser-known publications. After the success of her 1915 novel Michael O’Halloran, her books weren’t as successful nor as critically acclaimed, but that didn’t deter her.

Gene squeezed all she could out of life and nature in Indiana, though eventually, a change of scenery was desired. Having visited California, Gene felt an undeniable pull to move to Los Angeles. She wrote a friend, “I sorter like this glorious sunshine, the pergola of Cherokee roses, the orange trees and blood-red poinsettias, and the mocking birds tame as robins back at home.”

Following her daughter’s divorce, Gene took Jeannette, who now had two daughters of her own, and moved to Los Angeles. Charles Porter remained in Indiana, tending to his business pursuits. It was in California that Gene did much of her writing, especially poetry, and where she enjoyed the fruits of her labor.

Quite a few of her novels were even turned into films, some multiple times. She founded her own production company, Gene Stratton-Porter Productions, to produce silent films based on her novels, and even directing some of them. There was a long hiatus from her books being filmed in the 1920s, with just a scattering across the decades after. The most recent was a new adaptation of A Girl of the Limberlost in 1990.

Death and legacy

Sadly, in 1924, Gene was killed in a car accident in Los Angeles. She was sixty-one years old. The reverend leading her funeral said of her, “Hers was ever an original way. She did nothing after a prescribed fashion.”

Most of Gene Stratton-Porter’s novels became best sellers, and were wildly popular in the first quarter of the twentieth century. She published twenty-six books, which included twelve novels, eight nature studies, plus collections of stories, children’s books, and poetry volumes. She’s a much admired figure in her home state of Indiana, where there are numerous tributes to her in many forms, including a historic site in the state’s Rome City. A one-woman play titled “A Song in the Wilderness” was staged in 2017 as part of the Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival

The life this amazing woman led, and the boldness she demonstrated in making it her own, paved the way for so many other women to pursue their dreams.

As she was sometimes called, the “swamp angel,” or the “bird lady,” gave so much to the world in her intricate, detailed and passionate writing about the natural world. Her hope was that in doing so, she would ignite the same fervor and love she felt for even the tiniest of creatures, spurring others to help preserve and value them for all time.

Contributed by Emily Speight, who says, “Much like Gene Stratton-Porter, I love nature and the lessons learned from it’s tales. I am the wife to an amazing and supportive husband, and a stay-at-home mother, teacher to and expert of my two sweet boys. In my spare time I enjoy nature walks, painting and swing dancing. ”

More about Gene Stratton-Porter

Major works

Novels, children’s books, and essay collections

The Song of the Cardinal (1903)

Freckles (1904)

At the Foot of the Rainbow (1907)

A Girl of the Limberlost (1909)

After the Flood (1911)

The Harvester (1911)

Laddie (1913)

Birds of the Limberlost (1914)

Michael O’Halloran (1915)

Morning Face (1916)

A Daughter of the Land (1918)

Her Father’s Daughter (1921)

The White Flag (1923)

The Keeper of the Bees (1925)

The Magic Garden (1927)

Nature studies

What I Have Done with Birds, 1907 (Retitled Friends in Feathers , 1917)

Birds of the Bible (1909)

Music of the Wild (1910)

Moths of the Limberlost (1912)

Homing with the Birds (1919)

Wings (1923)

Tales You Won’t Believe (1925)

Read and listen online

Project Gutenberg

Audio versions on Librivox

More information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Gene Stratton-Porter’s books on Goodreads

Gene Stratton-Porter archives

Indiana History

Friends of the Limberlost

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing

The post Gene Stratton-Porter appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 15, 2019

Quotes from Excellent Women and other novels by Barbara Pym

Barbara Pym (1913 – 1980) was a British author whose novels explored manners and morals in village life. Yet even though most of the action, such as it is, is set in small town England locales, her stories convey universal truths about human foibles. She published thirteen novels in her lifetime, four published posthumously. The following selection of quotes from Excellent Women and other novels by Barbara Pym demonstrate her sense of irony and subtle, understated wit.

The novels published in her lifetime are considered the Pym canon, with many devotees citing Excellent Women as their entry-point or favorite. Pym was often compared to Jane Austen for her comedies of manner; she has been called Britain’s “other Jane Austen” or “new Jane Austen.”

In an homage to Pym in the New York Times (August 24, 2017), Matthew Schneier wrote:

“Barbara Pym, the midcentury English novelist, is forever being forgotten, and forever revived. Her novels sketch a circumscribed scene whose anchors were the church and the vicarage, and the busy, decent Englishmen and -women (more women) who shuffled between the two. To read her, one must have an appetite for endless jumble sales and whist drives, and the interfering wisdom of dowagers and distressed gentlewomen.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Some Tame Gazelle (1950)

“But surely liking the same things for dinner is one of the deepest and most lasting things you could possibly have in common with anyone,’ argued Dr. Parnell. ‘After all, the emotions of the heart are very transitory, or so I believe; I should think it makes one much happier to be well-fed than well-loved.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“If only one could clear out one’s mind and heart as ruthlessly as one did one’s wardrobe.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Yes, I love September … Michaelmas daisies and blackberries and comforting things like fires in the evening again and knitting.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Also, it was the morning and it seemed a little odd to be thinking about poetry before luncheon.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Excellent Women (1952)

Barbara Pym page on Amazon

“I realised that one might love him secretly with no hope of encouragement, which can be very enjoyable for the young or inexperienced.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“My thoughts went round and round and it occurred to me that if I ever wrote a novel it would be of the ‘stream of consciousness’ type and deal with an hour in the life of a woman at the sink.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Once you get into the habit of falling in love you will find that it happens quite often and means less and less.”. . . . . . . . . . .

“There are some things too dreadful to be revealed, and it is even more dreadful how, in spite of our better instincts, we long to know about them.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Surely many a romance must have been nipped in the bud by sitting opposite somebody eating spaghetti?”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Perhaps long spaghetti is the kind of thing that ought to be eaten quite alone with nobody to watch one’s struggles.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Virtue is an excellent thing and we should all strive after it, but it can sometimes be a little depressing.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I was so astonished that I could think of nothing to say, but wondered irrelevantly if I was to be caught with a teapot in my hand on every dramatic occasion.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I hope you don’t mind tea in mugs,’ she said, coming in with a tray. ‘I told you I was a slut.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I mumbled something about making a joke and that of course one needed tea always, at every hour of the day or night.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I stretched out my hand towards the little bookshelf where I kept cookery and devotional books, the most comfortable bedside reading.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Let me hasten to add that I am not at all like Jane Eyre, who must have given hope to so many plain women who tell their stories in the first person, nor have I ever thought of myself as being like her.”

Quotes from Jane and Prudence (1953)

“Once outside the magic circle the writers became their lonely selves, pondering on poems, observing their fellow men ruthlessly, putting people they knew into novels; no wonder they were without friends.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Prudence thanked him, experiencing that feeling of contrition which comes to all of us when we have made up our minds to dislike people for no apparent reason and they then perform some kind action.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Prue hadn’t really been in love with Fabian. Indeed, it was obvious that at times she found him both boring and irritating. But wasn’t that what so many marriages were – finding a person boring and irritating and yet loving him? Who could imagine a man who was never boring, or irritating?”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Prudence’s flat was in the kind of block where Jane imagined people might be found dead, though she had never said this to Prudence herself; it seemed rather a macabre fancy and not one to be confided to an unmarried woman living alone.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“For although she had been, and still was, very much admired, she had got into the way of preferring unsatisfactory love affairs to any others, so that it was becoming almost a bad habit.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“If it is true that men only want one thing, Jane asked herself, is it perhaps just to be left to themselves with their soap animals or some other harmless little trifle?”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Oh, but it was splendid the things women were doing for men all the time, thought Jane. Making them feel, perhaps sometimes by no more than a casual glance, that they were loved and admired and desired when they were worthy of none of these things — enabling them to preen themselves and puff out their plumage like birds and bask in the sunshine of love, real or imagined, it didn’t matter which.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“People do seem to be ashamed of admitting that they read poetry,’ said Jane, ‘unless they have a degree in English—it is permissible then.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I suppose old atheists seem less wicked and dangerous than young ones,’ said Jane. ‘One feels that there is something of the ancient Greeks in them.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Jane decided he was certainly beautiful, with brown eyes and a well-shaped nose. It is a refreshing thing for an ordinary-looking woman to look at a beautiful man occasionally and Jane gave herself up to contemplation.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Quartet in Autumn (1977)

“Letty allowed her to ramble on while she looked around the wood, remembering its autumn carpet of beech leaves and wondering if it could be the kind of place to lie down in and prepare for death when life became too much to be endured.”

“There was something to be said for tea and a comfortable chat about crematoria.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“She had always been an unashamed reader of novels.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“One did not drink sherry before the evening, just as one did not read a novel in the morning.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Four people on the verge of retirement, each one of us living alone, and without any close relative near – that’s us.”

“If the two women feared that the coming of this date might give some clue to their ages, it was not an occasion for embarrassment because nobody else had been in the least interested, both of them having long ago reached ages beyond any kind of speculation.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from An Unsuitable Attachment

(1963; published 1982)

“In the weeks that had passed since she had met Rupert Stonebird at the vicarage her interest in him had deepened, mainly because she had not seen him again and had therefore been able to build up a more satisfactory picture of him than if she had been able to check with reality.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“She had now reached an age when one starts looking for a husband rather more systematically than one does at nineteen or even at twenty-one.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Oh, this coming back to an empty house,’ Rupert thought, when he had seen her safely up to her door. People – though perhaps it was only women – seemed to make so much of it. As if life itself were not as empty as the house one was coming back to.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“She saw herself perhaps as an Elizabeth Bowen heroine – for one did not openly identify oneself with Jane Austen’s heroines – and ‘To The North’ was her favourite novel.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Well, some books are destined never to be read,” said Mervyn. ‘Its’s the natural order of things.”

“Like women who are destined never to marry, thought Ianthe.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Crampton Hodnet

(ca. 1940; published 1985)

“There are no sick people in North Oxford. They are either dead or alive.It’s sometimes difficult to tell the difference, that’s all.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“It was only sometimes, when a spring day came in the middle of winter, that one had a sudden feeling that nothing was really impossible.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“She knew exactly how she ought to feel, for she was well read in our greater and lesser English poets, but the unfortunate fact was that she did not really like being kissed at all.”

“Inanimate objects were often so much nicer than people.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“A youngish woman of about thirty-five who had come in to shelter from a heavy shower of rain, pricked up her ears and looked away from the book she had not been reading. To realize that two men could apparently be quarreling almost publicly over a woman in this unchivalrous age sent her on her way with new hope.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Barbara Pym

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Excellent Women and other novels by Barbara Pym appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 14, 2019

Caroline Kirkland

Caroline Kirkland (full name, Caroline Mathilda Stansbury Kirkland; January 11, 1801 – April 6, 1864) was an American essayist, writer, and educator, best known for her books examining the frontier settlement. Her work as an editor demonstrated her strong commitment to realism in what she deemed acceptable for publication along with her critical skill in her reviews.

Caroline Stansbury was born into a middle-class family in New York City, the oldest of eleven siblings. Her mother was a writer of fictional stories and poetry, and her entire family had a love of reading. One of her greatest influences was her grandfather, Joseph Stansbury, who was an ardent Loyalist during the American Revolution.

Early life and education

Caroline attended school at her aunt’s prestigious school for young ladies. Here, she excelled both in the classroom and in extracurricular activities, such as music and dance. Afterward, she worked alongside her aunt, Lydia Philadelphia Mott, who became the headmistress at several academically outstanding schools for young women.

Caroline’s father died when she was twenty-one years old, and from that time on, Kirkland took on the responsibility of supporting her family.

Leaving New York City

After her father’s death, Caroline and her family moved to upstate New York, where she taught and would soon meet her future husband, William Kirkland. The couple married in 1828 and settled in Geneva, New York.

The couple had seven children, four of whom survived early childhood. Here, they also founded the Domestic school for boys. Caroline believed her students should be treated as part of their family, so she watched over her own children as well as the resident boys.

The Kirklands left Geneva in 1835 to what was then considered a frontier town — now known as Detroit, Michigan. William Kirkland followed his dreams by purchasing land, and helped found the village of Pinckney, just northwest of Detroit, in 1837.

Success soon came their way as Caroline’s book, A New Home; Who’ll Follow?, was published. She wrote another book about the settlements titled Forest Life.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A land scam in Pinckney

The Kirklands left Michigan in 1843 after learning that William, like his neighbors, was tricked by corrupt land agents. Wildcat banks issued paper notes that had no value, and then closed practically overnight. Others who joined them in Pinckney similarly duped in the new settlement.

In addition to losing money, the Kirklands felt as though their neighbors had turned against them because of Caroline’s revelations of life on the frontier. Just two years after leaving Michigan, Caroline wrote a third book based on frontier life called Western Clearings. Afterward, she returned to New York City to be with her family.

The family’s move back to New York City seemed promising. Their son, Joseph Kirkland, was becoming a recognized writer. William began working in the newspaper business as an editor of the New York Evening Mirror along with his own paper, the Christian Inquirer. His good fortune was short-lived; in 1846, near-sighted and hard of hearing, he accidentally fell of a pier and drowned. For the second time in her life, Caroline was left to care for her family alone.

Making new friends

After the sudden death of her husband, Caroline opened a school for girls in New York City and began working as an editor of Union Magazine (1847 to 1849).

She became part of the literary social life of the New York City as well. Her home became a literary salon where she often entertained writers, publishers, and other nobles, including Edgar Allan Poe, William Cullen Bryant, Elizabeth Drew Stoddard, and others. Poe, in particular, believed that she was a gifted American writer. Here is an excerpt of Poe’s critique of A New Home:

“Mrs. Kirkland’s A New Home, published under the nom de plume Mary Clavers, wrought an undoubted sensation. The cause lay not so much in the picturesque description, in racy humor, or animated individual portraiture, as in truth and novelty. The west at the time was a field comparatively untrodden by the sketcher or the novelist. In certain works, to be sure, we had obtained brief glimpses of character strange to us sojourners in the civilized east, but to Mrs. Kirkland alone we were indebted for our acquaintance with the home and home-life of the backwoodsman.”

From 1848 through 1850, Caroline traveled abroad, where she was received by Charles Dickens and the Brownings — Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning. During this time, she also became very close friends and correspondents of Harriet Martineau.

Themes in Caroline Kirkland’s work

Caroline Kirkland had gained much fame and praise from her work during her lifetime. She wrote primarily because she liked to write, and published only what she thought was well written. Though she wrote from a decidedly female perspective, her writings wer intended for both women and men.

Her work discusses the frontier, more specifically the movement west of white settlers. A New Home: Who’ll Follow? (1839) debunked the popular belief that the West is a place of untapped wealth. “I have never seen a cougar—nor been bitten by a rattlesnake,” she tells readers.

She writes from the perspective of other woman of her time migrating Westward, most always compelled to follow the man. She delves into the cost to women of constantly having to pursue a change to improve one’s lot in life.

Her work provided context for the commitment of mid-19th-century women to the values of home, domesticity, and family. She was also an excellent, and fairly rare, example of an early American woman writer who was able to successfully establish a voice in a male-dominated profession.

. . . . . . . . . .

Caroline Kirkland page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . .

Caroline Kirkland’s legacy

Caroline Kirkland continued to create literary works until her death in 1864. After her death, Bayard Taylor, an author and Western correspondent, remembered her as “the possessor of more genius than any woman in America.”

Subsequently, her work was overlooked for more than a century. In the 1970s, her work was rediscovered, establishing her reputation as a social critic and pioneering literary realist. Today, her works continue to be studied for their contributions to American literature and the influence of the female perspective.

Essays and excerpts by Caroline Kirkland subsequently appeared in a number of contemporary anthologies, Including Women’s Work: An Anthology of American Literature (1984). In 1994, Lori Merish’s “The Hand of Refined Taste” in the Frontier Landscape: Caroline Kirkland’s A New Home, Who’ll Follow? And the Feminization of American Consumerism” won the Constance M. Rourke Prize.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Caroline Kirkland

Major works

A New Home; Who’ll Follow? (1839; published under the pseudonym Mary Clavers)

Forest Life (1842)

Western Clearings (1845)

Essays and stories

“Harvest Musings” (essay, 1842)

“Insect Life” (essay, 1839)

“The Schoolmaster’s Progress” (short story)

Read and listen online

Various works and anthologies on Internet Archive

“The Schoolmaster’s Progress” (short story) on Librivox

More information and sources

Wikipedia

Encyclopedia

Women History Blog

Georgetown.edu

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Caroline Kirkland appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 10, 2019

Barbara Pym

Barbara Pym (Born Barbara Mary Crampton Pym; June 2, 1913 – January 11, 1980) was a British author whose novels explored manners and morals in village life with a subtle, understated wit. She published nine novels in her lifetime and four books were published posthumously.

Tweed skirts and peach halves, knitted socks and tea kettles, macaroni cheese and old books: Barbara Pym has become known for her novels about the small comforts of mid-twentieth-century Englishwomen’s daily lives.

Much as Belinda turns the conversation to lighter topics in Barbara Pym’s first published novel, Some Tame Gazelle (1950), to avoid argument and taking things too seriously, Pym’s fiction appears to focus on lighter matters.

She appears to be concerned with whether to serve a rich fruit cake or a cake with a coffee icing or with who knits socks for whom, but these details reveal deeper truths about how people forge and maintain connections, and what happens when those efforts fail and people live solitary lives.

Upbringing and education

Born in the small market town of Oswestry, in Shropshire, her father, Frederic Crampton Pym, belonged to a professional class, as a lawyer in a firm of solicitors. Her mother, Irena Thomas, was the assistant organist at the church they attended and was a handsome, “tomboyish” woman, according to Hazel Holt, friend and co-worker (and, later, the literary executor of Barbara Pym’s will).

At the age of twelve, Pym attended Huyton College in Liverpool, a boarding school for girls. There she read Aldous Huxley’s Crome Yellow and determined that she would become a writer. Holt recalls her early creative work, at the age of sixteen, as “respectable but adolescent”.

From 1931 to 1934, she studied at St. Hilda’s College (Oxford) graduating with a BA (Honors) in English. In A Mind at Ease, Robert Liddell recalls her as a student: a “cheerful, romantic outgoing girl of just nineteen, playfully flirtatious, whose interest in men was keen but not obsessive.”

She met her steadiest love interest there, in 1932: Henry Harvey, who later married (and divorced) another woman, Elsie Godenhjelm. She had a string of suitors but, according to Holt, she tended to pursue “safe” romances.

A Young Writer at War and at Work

From 1934 to 1939, Pym was living at home and reading widely. She particularly loved poetry and describes in “Finding a Voice” her discovery of Elizabeth von Arnim as a revelation (particularly The Enchanted April and The Pastor’s Wife), for von Arnim’s “dry, unsentimental treatment of the relationship between men and women.”

Other writers she considered influential included Ivy Compton-Burnett (for her “precise, formal conversation”), John Betjeman (for his “glorifying of ordinary things and buildings”), Gertrude Trevelyan (for Hothouse, which made her long to write an Oxford novel), and Denton Welch (for Maiden Voyage, which reflects his “acute miniaturist observation and vibrant interest in everything he saw”).

Early in the war years, Pym helped her mother care for six children who had been evacuated from Birkenhead ???. Shortly afterward, she volunteered at the local YMCA camp for soldiers and then began working at the Postal and Telegraph Censorship in Bristol, which suited her inquisitive personality.

She joined the Women’s Royal Navy Service in 1940 and travelled to Naples, where she served as an officer (an experience characterized by nightly cocktail parties and minor romances, Holt explains).

After the war and following her mother’s death from cancer, Pym began work at an anthropological foundation – the International African Institute – in 1946. Just two years later, she was promoted to the position of research assistant there. She was writing in the evenings and on weekends, continuing work on the draft she began after graduation, a novel about two middle-aged sisters sharing a home.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Early publications: a subtle world-building

Drawing on her relationship with her younger sister, Hilary, Pym published Some Tame Gazelle in 1950, which considered the youth and middle years of Harriet and Belinda Bede. Straight away readers recognize the importance of church personnel in the lives of these women, which reflected Pym’s younger years, in which much of the family’s social life revolved around the church calendar.

Church men come for tea and stay for cake – and an occasional nap. As Belinda observes: “Of course, if the Archdeacon had not been asleep, she could have had some conversation within, but it was nice to know that he felt really at home, and she would not for the world have had him any different.” These are not idealized, sacred figures: their religiosity takes a back seat to their main-dish and dessert preferences.

Pym published three more novels in quick succession (Excellent Women in 1952, Jane and Prudence in 1953, and Less than Angels in 1955) before she was promoted to editorial secretary and assistant editor of Africa (a quarterly publication of the anthropological institute) in 1958.

That same year she published A Glass of Blessings, notable for its unambiguously gay characters and for its reference of a character in her previous novel, illuminating a subtle world-building designed to please her growing body of readers.

Her work at the International African Institute fueled her interest in the worlds of academics and anthropologists: people studying people. In “The Quest for a Career,” Constance Malloy describes how Pym and Hazel Holt would invent “home lives” and “field lives” for their co-workers.

Holt describes Pym’s working years from 1946 to 1974, in “The Novelist in the Field” and explains that only “occasionally, when she had an idea or when things were a little slack, she would write a bit of a novel in the office”. Pym chose to work from 10 am to 6 pm in the offices in St. Dunstan’s Chambers, so that she could avoid the 5 o’clock rush on the subway, so it’s easy to imagine that there were a few slack evenings while her colleagues were already en route in the crowds.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A disruption and renewed recognition

After her next novel, No Fond Return of Love (1961), which Holt believes to contain the most Pym-like character of all (Dulcie), Pym’s publisher lost interest in her work. Rejections accumulated and concerns about salability surfaced. She continued to write for her own satisfaction, but even after finishing three complete drafts, publishers kept their distance.

In the interim, she was diagnosed with and treated for breast cancer and she suffered a minor stroke. Still, she wrote. “Often she would get out one of the spiral-backed notebooks in which she recorded her observations and make a note of something that had caught her attention,” Holt remarked.

In 1977, in a special issue of the Times Literary Supplement which considered the “most underrated writer” of the previous 75 years, two writers, Philip Larkin and Lord David Cecil, named Barbara Pym. Larkin wrote, “I’d sooner read a new Barbara Pym than a new Jane Austen.” Publishers’ interest was renewed and her public work resumed with A Quartet in Autumn (1977).

Her books still considered anthropology and the church and also reflected her developing interests in local history and healthcare. Of these later novels, Holt refers to Letty’s character in Quartet in Autumn as the closest to Pym, as she was in the early 1960s. It was followed by The Sweet Dove Died (1978) and A Few Green Leaves (1979).

. . . . . . . . . .

Barbara Pym page on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . . .

Barbara Pym’s legacy and posthumous publications

In a letter to a friend in 1976, Pym commented: “And what could be more mundane than trying to type a novel.” (This is quoted in Deborah Donato’s Reading Barbara Pym.)

Pym was not aiming to chronicle the lives of extraordinary adventurers. As Shirley Hazzard describes it: “She is herself the poet of the lonely, the virtuous, the ironic; of the unostentatiously intelligent and witty; of the angelically self-effacing, with their diabolically clear gaze. Nothing escapes such persons; and they escape nothing.”

The novels published in her lifetime are considered the Pym canon, with many devotees citing Excellent Women as their entry-point or favorite. Four additional works were published posthumously – An Unsuitable Attachment (1982), Crampton Hodnet (1985), An Academic Question (1986) and Civil to Strangers (1987) – and excerpts from her diaries and letters were published as A Very Private Eye (1984).

Pym was often compared to Jane Austen for her comedies of manner; she was called Britain’s “other Jane Austen” or “new Jane Austen.”

In an homage to Pym in the New York Times (August 24, 2017), Matthew Schneier wrote:

“Barbara Pym, the midcentury English novelist, is forever being forgotten, and forever revived. Her novels sketch a circumscribed scene whose anchors were the church and the vicarage, and the busy, decent Englishmen and -women (more women) who shuffled between the two. To read her, one must have an appetite for endless jumble sales and whist drives, and the interfering wisdom of dowagers and distressed gentlewomen.”

Barbara Pym died in Oxford on January 11, 1980, at the age of sixty-seven.

More about Barbara Pym

Major Works

Some Tame Gazelle (1950)

Excellent Women (1952)

Jane and Prudence (1953)

Less than Angels (1955)

A Glass of Blessings (1958)

No Fond Return of Love (1961)

Quartet in Autumn (1977)

The Sweet Dove Died (1978)

A Few Green Leaves (1980)

An Unsuitable Attachment (written 1963; published posthumously, 1982)

Crampton Hodnet (written around 1940, published posthumously, 1985)

An Academic Question (written 1970–72; published posthumously, 1986)

Civil to Strangers (written 1936; published posthumously, 1987)

Biographies

A Lot to Ask: A Life of Barbara Pym by Hazel Holt (1990)

Barbara Pym: A Very Private Eye by Barbara Pym (1984)

A la Pym: The Barbara Pym Cookery Book by Hilary Pym and Honor Wyatt (1995)

More information and sources

The Barbara Pym Society

Marvelous Spinster Barbara Pym At 100

Barbara Pym and the New Spinster

In Praise of Barbara Pym

BBC’s Desert Island Discs with Barbara Pym in 1978

An Experiment with the Barbara Pym Cookbook

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Pym’s work on Goodreads

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Barbara Pym appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 7, 2019

“Spunk” by Zora Neale Hurston (1925)- full text

Zora Neale Hurston’s third published short story, “Spunk” (1925), helped launch her career as a fiction writer. She had already established herself as an ethnographer and folklorist, having been the first Black student to study anthropology at Columbia University in New York City. The following year, “Spunk was published in the prestigious Opportunity, A Journal of Negro Life, and her literary career was off and running.

“Spunk” won second place in Opportunity’s fiction writing contest that year. At the awards dinner on May 1, 1925, Zora also won second place in the drama category for her play, Color Struck, plus two honorable mentions. These early successes helped assure Zora’s place as a writer in the creative world of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

“Spunk”: A brief plot summary

The story is set is a rural, all-black town in the South modeled on Eatonville, Florida, where Zora had grown up. As it begins, a group of men outside the town’s general store watch as Spunk Banks walks by, with Lena Kanty, the wife of another man, Joe Kanty, clinging to his arm. The men warn Joe that his wife is being lured away, and he sets off in search of her and her lover with a razor.

Described as “a giant of a brown skinned man,” Spunk is appraised with admiration, laced with a little fear, by his fellow townsmen. One of them, Elijah, touts Spunk’s fortitude and bravery with and anecdote about what happened at the sawmill, where they work. Just minutes after ‘Tes Miller’s death on the circle saw, Spunk approached the machine fearlessly, even though everyone else had been “too skeered to go near it.” That is, Spunk continued to operate the dangerous circle-saw just after it had killed his co-worker.

This incident, and Elijah’s telling of it, illustrates the esteem in which the townsmen hold Spunk Banks, and highlights extreme masculinity. It hardly seems to surprise them, then, that he could choose whatever woman he wanted, and pluck her right out of her marriage to a weaker man. Spunk’s size and strength seems to excuse him from the norms and decency of society, and allow his to flaunt his affair with a married woman for all to see.

Soon, the men hear a gunshot. In walks Spunk with Lena, who is shaken and upset, claiming that Joe attacked him from behind with a razor, and so he had no choice but to kill him.

Spunk is charged with the crime but gets off with the claim of self-defense. He is now free to live with his lady love. After he and Lena move in together, a black bobcat circles their house at night. Spunk goes out with his gun, but the bobcat rises on his hind legs and meets Spunk with a stare. Spunk is sure that the bobcat is Joe, back from the dead in another form in order to haunt him — and prevent him from marrying his widow, Lena.

Spunk’s confidence is gone, and he goes about trembling in fear. The trembling causes him to fall on the circle saw; he claims to have felt someone push him toward it, and that someone had to be Joe’s ghost. Minutes later, Spunk dies from his wounds.

Despite his show of strength and manliness, Spunk is weekend in the end by his superstition. While he is the one his fellow townsmen perceive as strong, and Joe as weak, Spunk’s fear of the bobcat, who he believes is the embodiment of Joe’s sprit, erodes his confidence and leads to his downfall.

Zora writes the dialogue of the characters in dialect, mirroring how she perceived Black southerners speaking in that time and place. Some fellow writers and literary critics of the time objected to this style of writing, feeling that it in some way demeaned the characters, it became something of a trademark of hers.

. . . . . . . .

You might also like this analysis of “The Gilded Six-Bits”

. . . . . . . .

“Spunk” by Zora Neale Hurston — full text

A giant of a brown-skinned man sauntered up the one street of the Village and out into the palmetto thickets with a small pretty woman clinging lovingly to his arm.

“Looka theah, folkses!” cried Elijah Mosley, slapping his leg gleefully. “Theah they go, big as life an’ brassy as tacks.”

All the loungers in the store tried to walk to the door with an air of nonchalance but with small success.

“Now pee-eople!” Walter Thomas gasped. “Will you look at ’em!”

“But that’s one thing Ah likes about Spunk Banks—he ain’t skeered of nothin‘ on God’s green footstool—nothin’! He rides that log down at saw-mill jus‘ like he struts ’round wid another man’s wife—jus‘ don’t give a kitty. When Tes’ Miller got cut to giblets on that circle-saw, Spunk steps right up and starts ridin’. The rest of us was skeered to go near it.”

A round-shouldered figure in overalls much too large, came nervously in the door and the talking ceased. The men looked at each other and winked.

“Gimme some soda-water. Sass’prilla Ah reckon,” the newcomer ordered, and stood far down the counter near the open pickled pig-feet tub to drink it.

Elijah nudged Walter and turned with mock gravity to the new-comer.

“Say, Joe, how’s everything up yo‘ way? How’s yo’ wife?”

Joe started and all but dropped the bottle he held in his hands. He swallowed several times painfully and his lips trembled.

“Aw ‘Lige, you oughtn’t to do nothin’ like that,” Walter grumbled. Elijah ignored him.

“She jus‘ passed heah a few minutes ago goin’ theta way,” with a wave of his hand in the direction of the woods.

Now Joe knew his wife had passed that way. He knew that the men lounging in the general store had seen her, moreover, he knew that the men knew he knew. He stood there silent for a long moment staring blankly, with his Adam’s apple twitching nervously up and down his throat. One could actually see the pain he was suffering, his eyes, his face, his hands and even the dejected slump of his shoulders. He set the bottle down upon the counter. He didn’t bang it, just eased it out of his hand silently and fiddled with his suspender buckle.

“Well, Ah’m goin‘ after her to-day. Ah’m goin’ an’ fetch her back. Spunk’s done gone too fur.”

He reached deep down into his trouser pocket and drew out a hollow ground razor, large and shiny, and passed his moistened thumb back and forth over the edge.

“Talkin‘ like a man, Joe. Course that’s yo’ fambly affairs, but Ah like to see grit in anybody.”

Joe Kanty laid down a nickel and stumbled out into the street.

Dusk crept in from the woods. Ike Clarke lit the swinging oil lamp that was almost immediately surrounded by candle-flies. The men laughed boisterously behind Joe’s back as they watched him shamble woodward.

“You oughtn’t to said whut you did to him, Lige—look how it worked him up,” Walter chided.

“And Ah hope it did work him up. ‘Tain’t even decent for a man to take and take like he do.”

“Spunk will sho’ kill him.”

“Aw, Ah doan’t know. You never kin tell. He might turn him up an‘ spank him fur gettin’ in the way, but Spunk wouldn’t shoot no unarmed man. Dat razor he carried outa heah ain’t gonna run Spunk down an‘ cut him, an’ Joe ain’t got the nerve to go up to Spunk with it knowing he totes that Army 45. He makes that break outa heah to bluff us. He’s gonna hide that razor behind the first likely palmetto root an‘ sneak back home to bed. Don’t tell me nothin’ ’bout that rabbit-foot colored man. Didn’t he meet Spunk an‘ Lena face to face one day las’ week an‘ mumble sumthin’ to Spunk ‘bout lettin’ his wife alone?”

“What did Spunk say?” Walter broke in—“Ah like him fine but ‘tain’t right the way he carries on wid Lena Kanty, jus’ cause Joe’s timid ‘bout fightin’.”

“You wrong theah, Walter. ‘Tain’t cause Joe’s timid at all, it’s cause Spunk wants Lena. If Joe was a passle of wile cats Spunk would tackle the job just the same. He’d go after anything he wanted the same way. As Ah wuz sayin’ a minute ago, he tole Joe right to his face that Lena was his. ‘Call her,’ he says to Joe. ‘Call her and see if she’ll come. A woman knows her boss an’ she answers when he calls.‘ ’Lena, ain’t I yo‘ husband?’ Joe sorter whines out. Lena looked at him real disgusted but she don’t answer and she don’t move outa her tracks. Then Spunk reaches out an‘ takes hold of her arm an’ says: ‘Lena, youse mine. From now on Ah works for you an’ fights for you an‘ Ah never wants you to look to nobody for a crumb of bread, a stitch of close or a shingle to go over yo’ head, but me long as Ah live. Ah’ll git the lumber foh owah house to-morrow. Go home an‘ git yo’ things together! ‘

” ‘Thass mah house,’ Lena speaks up. ‘Papa gimme that.’

“‘Well,’ says Spunk, ‘doan give up whut’s yours, but when youse inside don’t forgit youse mine, an’ let no other man git outa his place wid you!’

“Lena looked up at him with her eyes so full of love that they wuz runnin‘ over, an’ Spunk seen it an‘ Joe seen it too, and his lip started to tremblin’ and his Adam’s apple was galloping up and down his neck like a race horse. Ah bet he’s wore out half a dozen Adam’s apples since Spunk’s been on the job with Lena. That’s all he’ll do. He’ll be back heah after while swallowin‘ an’ workin‘ his lips like he wants to say somethin’ an’ can’t.”

“But didn’t he do nothin‘ to stop ’em?”

“Nope, not a frazzlin‘ thing—jus’ stood there. Spunk took Lena’s arm and walked off jus‘ like nothin’ ain’t happened and he stood there gazin‘ after them till they was outa sight. Now you know a woman don’t want no man like that. I’m jus’ waitin‘ to see whut he’s goin’ to say when he gits back.”

II

But Joe Kanty never came back, never. The men in the store heard the sharp report of a pistol somewhere distant in the palmetto thicket and soon Spunk came walking leisurely, with his big black Stetson set at the same rakish angle and Lena clinging to his arm, came walking right into the general store. Lena wept in a frightened manner.

“Well,” Spunk announced calmly, “Joe come out there wid a meatax an’ made me kill him.”

He sent Lena home and led the men back to Joe—Joe crumpled and limp with his right hand still clutching his razor.

“See mah back? Mah cloes cut clear through. He sneaked up an‘ tried to kill me from the back, but Ah got him, an’ got him good, first shot,” Spunk said.

The men glared at Elijah, accusingly.

“Take him up an‘ plant him in ’Stoney lonesome,”‘ Spunk said in a careless voice. “Ah didn’t wanna shoot him but he made me do it. He’s a dirty coward, jumpin’ on a man from behind.”

Spunk turned on his heel and sauntered away to where he knew his love wept in fear for him and no man stopped him. At the general store later on, they all talked of locking him up until the sheriff should come from Orlando, but no one did anything but talk.

A clear case of self-defense, the trial was a short one, and Spunk walked out of the court house to freedom again. He could work again, ride the dangerous log-carriage that fed the singing, snarling, biting, circle-saw; he could stroll the soft dark lanes with his guitar. He was free to roam the woods again; he was free to return to Lena. He did all of these things.

III

“Whut you reckon, Walt?” Elijah asked one night later. “Spunk’s gittin’ ready to marry Lena!”

“Naw! Why, Joe ain’t had time to git cold yit. Nohow Ah didn’t figger Spunk was the marryin’ kind.”

“Well, he is,” rejoined Elijah. “He done moved most of Lena’s things—and her along wid ‘em—over to the Bradley house. He’s buying it. Jus’ like Ah told yo‘ all right in heah the night Joe wuz kilt. Spunk’s crazy ’bout Lena. He don’t want folks to keep on talkin‘ ’bout her—thass reason he’s rushin‘ so. Funny thing ’bout that bob-cat, wan’t it?”

“What bob-cat, ‘Lige? Ah ain’t heered ’bout none.”

“Ain’t cher? Well, night befo‘ las’ was the fust night Spunk an‘ Lena moved together an’ jus‘ as they was goin’ to bed, a big black bob-cat, black all over, you hear me, black, walked round and round that house and howled like forty, an‘ when Spunk got his gun an’ went to the winder to shoot it he says it stood right still an‘ looked him in the eye, an’ howled right at him. The thing got Spunk so nervoused up he couldn’t shoot. But Spunk says twan’t no bob-cat nohow. He says it was Joe done sneaked back from Hell! ”

“Humph!” sniffed Walter, “he oughter be nervous after what he done. Ah reckon Joe come back to dare him to marry Lena, or to come out an’ fight. Ah bet he’ll be back time and agin, too. Know what Ah think? Joe wuz a braver man than Spunk.”

There was a general shout of derision from the group.

“Thass a fact,” went on Walter. “Lookit whut he done took a razor an‘ went out to fight a man he knowed toted a gun an’ wuz a crack shot, too; ‘nother thing Joe wuz skeered of Spunk, skeered plumb stiff! But he went jes’ the same. It took him a long time to get his nerve up. ‘Tain’t nothin’ for Spunk to fight when he ain’t skeered of nothin‘. Now, Joe’s done come back to have it out wid the man that’s got all he ever had. Y’ll know Joe ain’t never had nothin’ nor wanted nothin‘ besides Lena. It musta been a h’ant cause ain’ nobody never seen no black bob-cat.”

“Nother thing,” cut in one of the men, “Spunk wuz cussin’ a blue streak to-day ‘cause he ’lowed dat saw wuz wobblin‘—almos’ got ‘im once. The machinist come, looked it over an’ said it wuz alright. Spunk musta been leanin‘ t’wards it some. Den he claimed somebody pushed ’im but ‘twant nobody close to ’im. Ah wuz glad when knockin’ off time come. I’m skeered of dat man when he gits hot. He’d beat you full of button holes as quick as he’s look etcher.”

IV

The men gathered the next evening in a different mood, no laughter. No badinage this time.

“Look, ‘Lige, you goin’ to set up wid Spunk?”

“New, Ah reckon not, Walter. Tell yuh the truth, Ah’m a lil bit skittish. Spunk died too wicket—died cussin’ he did. You know he thought he wuz done outa life.”

“Good Lawd, who’d he think done it?”

“Joe.”

“Joe Kanty? How come? ”

“Walter, Ah b’leeve Ah will walk up theta way an’ set. Lena would like it Ah reckon.”

“But whut did he say, ‘Lige?”

Elijah did not answer until they had left the lighted store and were strolling down the dark street.

“Ah wuz loadin‘ a wagon wid scantlin’ right near the saw when Spunk fell on the carriage but ‘fore Ah could git to him the saw got him in the body—awful sight. Me an’ Skint Miller got him off but it was too late. Anybody could see that. The fust thing he said wuz: ‘He pushed me, ’Lige—the dirty hound pushed me in the back!‘—He was spittin’ blood at ev’ry breath. We laid him on the sawdust pile with his face to the East so’s he could die easy. He heft mah hen‘ till the last, Walter, and said: ’It was Joe, ‘Lige—the dirty sneak shoved me . . . he didn’t dare come to mah face . . . but Ah’ll git the son-of-a-wood louse soon’s Ah get there an’ make hell too hot for him. . . . Ah felt him shove me. . .!’ Thass how he died.”

“If spirits kin fight, there’s a powerful tussle goin‘ on somewhere ovah Jordan ’cause Ah b’leeve Joe’s ready for Spunk an‘ ain’t skeered any more yes, Ah b’leeve Joe pushed ’im mahself.”

They had arrived at the house. Lena’s lamentations were deep and loud. She had filled the room with magnolia blossoms that gave off a heavy sweet odor. The keepers of the wake tipped about whispering in frightened tones. Everyone in the village was there, even old Jeff Kanty, Joe’s father, who a few hours before would have been afraid to come within ten feet of him, stood leering triumphantly down upon the fallen giant as if his fingers had been the teeth of steel that laid him low.

The cooling board consisted of three sixteen-inch boards on saw horses, a dingy sheet was his shroud.

The women ate heartily of the funeral baked meats and wondered who would be Lena’s next. The men whispered coarse conjectures between guzzles of whiskey.

Source: Zora Neale Hurston, “Spunk,” in Alain Locke, ed., The New Negro (New York: A and C Boni, 1925), 105–111.

The post “Spunk” by Zora Neale Hurston (1925)- full text appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 3, 2019

Jonah’s Gourd Vine by Zora Neale Hurston (1934)

Jonah’s Gourd Vine by Zora Neale Hurston (1891 – 1960) was this eminent author’s first novel, published in 1934. It’s the story of a Black plantation worker who aspires to be a preacher. When he achieves his goal, he gives powerful sermons, and in between, indulges in much sinning with women of his congregation and others.

While studying with the noted anthropologist Franz Boas, Zora was recognized for her talent for storytelling and abiding interest in black cultures of the American South and Caribbean. Her background as an anthropologist and folklorist was one of her great gifts, and what made her work, both fiction and nonfiction, so unique. She was already established in the field when this novel came out, as well as having published a number of short stories and nonfiction works.

After decades out of print, HarperCollins reissued Jonah’s Gourd Vine in 2008. From the publisher’s description:

“Jonah’s Gourd Vine tells the story of John Buddy Pearson, ‘a living exultation’ of a young man who loves too many women for his own good. Lucy Potts, his long-suffering wife, is his true love, but there’s also Mehaley and Big ‘Oman, as well as the scheming Hattie, who conjures hoodoo spells to ensure his attentions.

Even after becoming the popular pastor of Zion Hope, where his sermons and prayers for cleansing rouse the congregation’s fervor, John has to confess that though he is a preacher on Sundays, he is a ‘natchel man’ the rest of the week.

And so in this sympathetic portrait of a man and his community, Zora Neale Hurston shows that faith, tolerance, and good intentions cannot resolve the tension between the spiritual and the physical. That she makes this age-old dilemma come so alive is a tribute to her understanding of the vagaries of human nature.”

Zora’s inspiration and intention

Zora describes her intent for Jonah’s Gourd Vine, which is possibly based on her own parents’ dysfunctional marriage. The novel provides an inside view of Reconstruction-era African-American life, with black families adjusting to freedom and migration.

Aspiring to better himself through education and religion, yet unable (and unwilling) to master his philandering ways, John Buddy Pearson’s divided nature leads to his inevitable downfall. In Zora’s own words:

“While I was in the research field in 1929, the idea of Jonah’s Gourd Vine came to me. I had written a few short stories, but the idea of attempting a book seems so big, that I gazed at it in the quiet of the night, but hid it away from even myself in daylight.

For one thing, it seemed off-key. What I wanted to tell was a story about a man, and from what I had read and heard, Negroes were supposed to write about the Race Problem. I was and am thoroughly sick of the subject. My interest lies in what makes a man or a woman do such and so, regardless of his color.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Jonah’s Gourd Vine by Zora Neale Hurston on Amazon

. . . . . . . . . . .

An original 1934 review of Jonah’s Gourd Vine

Here is George S. Schuyler‘s original review in The Pittsburgh Courier from May 12, 1934:

Jonah’s Gourd Vine by Zora Neale Hurston is a first class novel by a brilliant young woman. Like Elmer Gantry, it tells of the rise of a man of god, only John Pearson is a big, strong, magnetic mulatto* [note from Literary Ladies: this term is no longer used, it was a common term to describe a mixed-race person in the time this review was written].

Like Elmer Gantry, however, John cannot keep away from the sisters, and of course, that is his undoing. If this were all, Jonah’s Gourd Vine would still be a fine novel, because Zora Hurston knows all about our reverend clergy.

But this novel is a mine of folklore; a study of social life in the rural south, which the author knows so well. Julia Peterkin, Du Bose Heyward, and Roark Bradford have written about the Black rustic but they have all described him with the cool objectivity of an outsider. Miss Hurston writes of her folk with the knowledge and warmth of understanding that comes only with the intimate spiritual association.

She knows her people and loves them, but she is not blind to their faults, their fads, or their foibles. She knows their weakness and their strength.

Her ear for Southern country dialect is superb and in setting it down she excels any Dixie writer of today … I confess that I read Jonah’s Gourd Vine with progressively increased interest and rapidly mounting enthusiasm. It is smoothly written, a finished piece of work, valuable alike as literature and sociology. When I laid it down, I voted it one of the best novels ever written about the Southern Negro farmers.

More about Jonah’s Gourd Vine by Zora Neale Hurston

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Suggested Syllabus

Wikipedia

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Jonah’s Gourd Vine by Zora Neale Hurston (1934) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 27, 2019

Quotes by Anaïs Nin on Writing, Life, and Love

Anaïs Nin (1903 – 1977) was best known for her multi-volume Diary of Anaïs Nin, which became an iconic series of writings in feminist literature. She was a splendid essayist as well. The sampling of quotes that follow reflect her passionate nature and deep commitment to the writing life.

Born in France in 1903, Nin spent her teens living in the U.S., becoming self-educated and working as a model and dancer before returning to Europe in the 1920s.

From the earliest of her diaries, written while still in her teens, to one of her last essays, published just a year before her death in 1977, it’s clear that writing was what shaped her life and gave it meaning.

Though it’s generally believed that Nin wrote her Diaries with an eye toward eventual publication, it wasn’t until the 1960s that they were published and acclaimed as instant feminist classics, depicting one woman’s lifelong voyage of self-discovery.

Decades of writing accompanied by scant publication success is ample proof that passion was the main ingredient in her steadfast devotion to the craft. So when Nin examined the “why” of writing, it wasn’t for money, fame, or glory. Rather, it filled a need for her that was as elemental as breathing.

. . . . . . . . . .

“We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I am an excitable person who only understands life lyrically, musically, in whom feelings are much stronger as reason. I am so thirsty for the marvelous that only the marvelous has power over me. Anything I can not transform into something marvelous, I let go. Reality doesn’t impress me. I only believe in intoxication, in ecstasy, and when ordinary life shackles me, I escape, one way or another. No more walls.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I am aware of being in a beautiful prison, of which I can only escape by writing.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Life shrinks or expands according to one’s courage.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The personal life deeply lived always expands into truths beyond itself.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.”

You might also like: Anaïs Nin: Writing to Find Meaning in Life

. . . . . . . . . .

“Anxiety is love’s greatest killer. It creates the failures. It makes others feel as you might when a drowning man holds on to you. You want to save him, but you know he will strangle you with his panic.” (February, 1947)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Only the united beat of sex and heart together can create ecstasy.” (Delta of Venus, 1969)

. . . . . . . . . .

“He was now in that state of fire that she loved. She wanted to be burnt.” (Delta of Venus, 1969)

. . . . . . . . . .

“From the backstabbing co-worker to the meddling sister-in-law, you are in charge of how you react to the people and events in your life. You can either give negativity power over your life or you can choose happiness instead. Take control and choose to focus on what is important in your life. Those who cannot live fully often become destroyers of life.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“… You don’t write for yourself or for others. You write out of a deep inner necessity. If you are a writer, you have to write, just as you have to breathe, or if you’re a singer you have to sing. (“The Artist as Magician,” interview, 1973)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Love never dies a natural death. It dies because we don’t know how to replenish its source. It dies of blindness and errors and betrayals. It dies of illness and wounds; it dies of weariness, of witherings, of tarnishings.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Incest: From a Journal of Love by Anaïs Nin

. . . . . . . . . .

“We write to taste life twice, in the moment and in retrospect.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“There were always in me, two women at least, one woman desperate and bewildered, who felt she was drowning and another who would leap into a scene, as upon a stage, conceal her true emotions because they were weaknesses, helplessness, despair, and present to the world only a smile, an eagerness, curiosity, enthusiasm, interest.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I didn’t have any particular gift in my twenties. I didn’t have any exceptional qualities. It was the persistence and the great love of my craft which finally became a discipline, which finally made me a craftsman and a writer.” (“The Personal Life Deeply Lived”)

. . . . . . . . . .

“How wrong is it for a woman to expect the man to build the world she wants, rather than to create it herself?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“If you do not breathe through writing, if you do not cry out in writing, or sing in writing, then don’t write, because our culture has no use for it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The role of a writer is not to say what we can all say, but what we are unable to say.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“We travel, some of us forever, to seek other states, other lives, other souls.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I believe one writes because one has to create a world in which one can live. I could not live in any of the worlds offered to me … I had to create a world of my own, like a climate, a country, an atmosphere in which I could breathe, reign, and recreate myself when destroyed by living. (In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays, 1976)

. . . . . . . . . .

“The secret of joy is the mastery of pain.”

. . . . . . . . . .