Nava Atlas's Blog, page 60

January 10, 2020

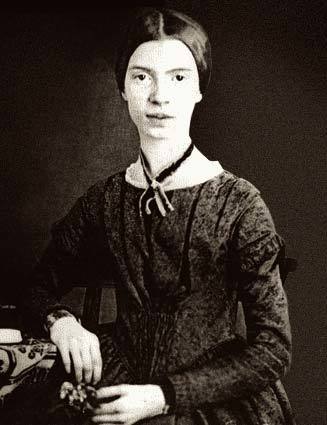

A Matter of Prejudice by Kate Chopin (1895) – full text

The short story, “A Matter of Prejudice” by Kate Chopin (1850 – 1904), the American author best remembered for The Awakening (1899), is one of many short works by this prolific author. It was written in 1893, first published in 1895, and included in Chopin’s collection A Night in Acadie (1897).

Much of Chopin’s literary output preceded The Awakening, a novella; the poor reception it received is thought to have discouraged her. It was often vilified by the press, and frequently banned. Decades later it became a feminist classic, and revitalized interest in her other writings.

“A Matter of Prejudice,” like many of Chopin’s works, comments on social mores and issues in late 19th-century Creole culture. It explores the theme of motherhood, as do many of her other stories, this one particularly focusing on the alienation of a mother and her son due to his choice of a wife. Per Seyerstad, a Chopin biographer, noted,

“This story is the only one by Chopin centered on the conflict between the new American and old Creole cultures. It illustrates her developing skill in characterization and irony, especially in its conclusion.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Awakening (1899) – full text

. . . . . . . . . .

“A Matter of Prejudice”

Madame Carambeau wanted it strictly understood that she was not to be disturbed by Gustave’s birthday party. They carried her big rocking-chair from the back gallery, that looked out upon the garden where the children were going to play, around to the front gallery, which closely faced the green levee bank and the Mississippi coursing almost flush with the top of it.

The house — an old Spanish one, broad, low and completely encircled by a wide gallery – was far down in the French quarter of New Orleans. It stood upon a square of ground that was covered thick with a semi-tropical growth of plants and flowers. An impenetrable board fence, edged with a formidable row of iron spikes, shielded the garden from the prying glances of the occasional passer-by.

Madame Carambeau’s widowed daughter, Madame Cécile Lalonde, lived with her. This annual party, given to her little son, Gustave, was the one defiant act of Madame Lalonde’s existence. She persisted in it, to her own astonishment and the wonder of those who knew her and her mother.

For old Madame Carambeau was a woman of many prejudices – so many, in fact, that it would be difficult to name them all. She detested dogs, cats, organ-grinders, white servants and children’s noises. She despised Americans, Germans and all people of a different faith from her own. Anything not French had, in her opinion, little right to existence.

She had not spoken to her son Henri for ten years because he had married an American girl from Prytania street. She would not permit green tea to be introduced into her house, and those who could not or would not drink coffee might drink tisane of fleur de Laurier for all she cared.

Nevertheless, the children seemed to be having it all their own way that day, and the organ-grinders were let loose. Old madame, in her retired corner, could hear the screams, the laughter and the music far more distinctly than she liked. She rocked herself noisily, and hummed “Partant pour la Syrie.”

She was straight and slender. Her hair was white, and she wore it in puffs on the temples. Her skin was fair and her eyes blue and cold.

Suddenly she became aware that footsteps were approaching, and threatening to invade her privacy — not only footsteps, but screams! Then two little children, one in hot pursuit of the other, darted wildly around the corner near which she sat.

The child in advance, a pretty little girl, sprang excitedly into Madame Carambeau’s lap, and threw her arms convulsively around the old lady’s neck. Her companion lightly struck her a “last tag,” and ran laughing gleefully away.

The most natural thing for the child to do then would have been to wriggle down from madame’s lap, without a “thank you” or a “by your leave,” after the manner of small and thoughtless children. But she did not do this. She stayed there, panting and fluttering, like a frightened bird.

Madame was greatly annoyed. She moved as if to put the child away from her, and scolded her sharply for being boisterous and rude. The little one, who did not understand French, was not disturbed by the reprimand, and stayed on in madame’s lap. She rested her plump little cheek, that was hot and flushed, against the soft white linen of the old lady’s gown.

Her cheek was very hot and very flushed. It was dry, too, and so were her hands. The child’s breathing was quick and irregular. Madame was not long in detecting these signs of disturbance.

Though she was a creature of prejudice, she was nevertheless a skillful and accomplished nurse, and a connoisseur in all matters pertaining to health. She prided herself upon this talent, and never lost an opportunity of exercising it. She would have treated an organ-grinder with tender consideration if one had presented himself in the character of an invalid.

Madame’s manner toward the little one changed immediately. Her arms and her lap were at once adjusted so as to become the most comfortable of resting places. She rocked very gently to and fro. She fanned the child softly with her palm leaf fan, and sang “Partant pour la Syrie” in a low and agreeable tone.

The child was perfectly content to lie still and prattle a little in that language which madame thought hideous. But the brown eyes were soon swimming in drowsiness, and the little body grew heavy with sleep in madame’s clasp.

When the little girl slept Madame Carambeau arose, and treading carefully and deliberately, entered her room, that opened near at hand upon the gallery. The room was large, airy and inviting, with its cool matting upon the floor, and its heavy, old, polished mahogany furniture. Madame, with the child still in her arms, pulled a bell-cord; then she stood waiting, swaying gently back and forth. Presently an old black woman answered the summons. She wore gold hoops in her ears, and a bright bandanna knotted fantastically on her head.

“Louise, turn down the bed,” commanded madame. “Place that small, soft pillow below the bolster. Here is a poor little unfortunate creature whom Providence must have driven into my arms.” She laid the child carefully down.

“Ah, those Americans! Do they deserve to have children? Understanding as little as they do how to take care of them!” said madame, while Louise was mumbling an accompanying assent that would have been unintelligible to any one unacquainted with the negro patois.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: Desirée’s Baby (full text)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“There, you see, Louise, she is burning up,” remarked madame; “she is consumed. Unfasten the little bodice while I lift her. Ah, talk to me of such parents! So stupid as not to perceive a fever like that coming on, but they must dress their child up like a monkey to go play and dance to the music of organ- grinders.

“Haven’t you better sense, Louise, than to take off a child’s shoe as if you were removing the boot from the leg of a cavalry officer?” Madame would have required fairy fingers to minister to the sick. “Now go to Mamzelle Cécile, and tell her to send me one of those old, soft, thin nightgowns that Gustave wore two summers ago.”

When the woman retired, madame busied herself with concocting a cooling pitcher of orange-flower water, and mixing a fresh supply of eau sédative with which agreeably to sponge the little invalid.

Madame Lalonde came herself with the old, soft nightgown. She was a pretty, blonde, plump little woman, with the deprecatory air of one whose will has become flaccid from want of use. She was mildly distressed at what her mother had done.

“But, mamma! But, mamma, the child’s parents will be sending the carriage for her in a little while. Really, there was no use. Oh dear! oh dear!”

If the bedpost had spoken to Madame Carambeau, she would have paid more attention, for speech from such a source would have been at least surprising if not convincing. Madame Lalonde did not possess the faculty of either surprising or convincing her mother.

“Yes, the little one will be quite comfortable in this,” said the old lady, taking the garment from her daughter’s irresolute hands.

“But, mamma! What shall I say, what shall I do when they send? Oh, dear; oh, dear!”

“That is your business,” replied madame, with lofty indifference. “My concern is solely with a sick child that happens to be under my roof. I think I know my duty at this time of life, Cécile.”

As Madame Lalonde predicted, the carriage soon came, with a stiff English coachman driving it, and a red-checked Irish nurse-maid seated inside. Madame would not even permit the maid to see her little charge. She had an original theory that the Irish voice is distressing to the sick.

Madame Lalonde sent the girl away with a long letter of explanation that must have satisfied the parents; for the child was left undisturbed in Madame Carambeau’s care. She was a sweet child, gentle and affectionate. And, though she cried and fretted a little throughout the night for her mother, she seemed, after all, to take kindly to madame’s gentle nursing. It was not much of a fever that afflicted her, and after two days she was well enough to be sent back to her parents.

Madame, in all her varied experience with the sick, had never before nursed so objectionable a character as an American child. But the trouble was that after the little one went away, she could think of nothing really objectionable against her except the accident of her birth, which was, after all, her misfortune; and her ignorance of the French language, which was not her fault.

But the touch of the caressing baby arms; the pressure of the soft little body in the night; the tones of the voice, and the feeling of the hot lips when the child kissed her, believing herself to be with her mother, were impressions that had sunk through the crust of madame’s prejudice and reached her heart.

She often walked the length of the gallery, looking out across the wide, majestic river. Sometimes she trod the mazes of her garden where the solitude was almost that of a tropical jungle. It was during such moments that the seed began to work in her soul – the seed planted by the innocent and undesigning hands of a little child.

The first shoot that it sent forth was Doubt. Madame plucked it away once or twice. But it sprouted again, and with it Mistrust and Dissatisfaction. Then from the heart of the seed, and amid the shoots of Doubt and Misgiving, came the flower of Truth. It was a very beautiful flower, and it bloomed on Christmas morning.

As Madame Carambeau and her daughter were about to enter her carriage on that Christmas morning, to be driven to church, the old lady stopped to give an order to her black coachman, François. François had been driving these ladies every Sunday morning to the French Cathedral for so many years – he had forgotten exactly how many, but ever since he had entered their service, when Madame Lalonde was a little girl. His astonishment may therefore be imagined when Madame Carambeau said to him:

“François, to-day you will drive us to one of the American churches.”

“Plait-il, madame?” the negro stammered, doubting the evidence of his hearing.

“I say, you will drive us to one of the American churches. Any one of them,” she added, with a sweep of her hand. “I suppose they are all alike,” and she followed her daughter into the carriage.

Madame Lalonde’s surprise and agitation were painful to see, and they deprived her of the ability to question, even if she had possessed the courage to do so.

François, left to his fancy, drove them to St. Patrick’s Church on Camp street. Madame Lalonde looked and felt like the proverbial fish out of its element as they entered the edifice. Madame Carambeau, on the contrary, looked as if she had been attending St. Patrick’s church all her life. She sat with unruffled calm through the long service and through a lengthy English sermon, of which she did not understand a word.

When the mass was ended and they were about to enter the carriage again, Madame Carambeau turned, as she had done before, to the coachman.

“François,” she said, coolly, “you will now drive us to the residence of my son, M. Henri Carambeau. No doubt Mamzelle Cécile can inform you where it is,” she added, with a sharply penetrating glance that caused Madame Lalonde to wince.

Yes, her daughter Cécile knew, and so did François, for that matter. They drove out St. Charles avenue – very far out. It was like a strange city to old madame, who had not been in the American quarter since the town had taken on this new and splendid growth.

The morning was a delicious one, soft and mild; and the roses were all in bloom. They were not hidden behind spiked fences. Madame appeared not to notice them, or the beautiful and striking residences that lined the avenue along which they drove. She held a bottle of smelling-salts to her nostrils, as though she were passing through the most unsavory instead of the most beautiful quarter of New Orleans.

Henri’s house was a very modern and very handsome one, standing a little distance away from the street. A well-kept lawn, studded with rare and charming plants, surrounded it. The ladies, dismounting, rang the bell, and stood out upon the banquette, waiting for the iron gate to be opened.

A white maid-servant admitted them. Madame did not seem to mind. She handed her a card with all proper ceremony, and followed with her daughter to the house.

Not once did she show a sign of weakness; not even when her son, Henri, came and took her in his arms and sobbed and wept upon her neck as only a warm-hearted Creole could. He was a big, good-looking, honest-faced man, with tender brown eyes like his dead father’s and a firm mouth like his mother’s.

Young Mrs. Carambeau came, too, her sweet, fresh face transfigured with happiness. She led by the hand her little daughter, the “American child” whom madame had nursed so tenderly a month before, never suspecting the little one to be other than an alien to her.

“What a lucky chance was that fever! What a happy accident!” gurgled Madame Lalonde.

“Cécile, it was no accident, I tell you; it was Providence,” spoke madame, reprovingly, and no one contradicted her.

They all drove back together to eat Christmas dinner in the old house by the river. Madame held her little granddaughter upon her lap; her son Henri sat facing her, and beside her was her daughter-in-law.

Henri sat back in the carriage and could not speak. His soul was possessed by a pathetic joy that would not admit of speech. He was going back again to the home where he was born, after a banishment of ten long years.

He would hear again the water beat against the green levee-bank with a sound that was not quite like any other that he could remember. He would sit within the sweet and solemn shadow of the deep and overhanging roof; and roam through the wild, rich solitude of the old garden, where he had played his pranks of boyhood and dreamed his dreams of youth. He would listen to his mother’s voice calling him, “mon fils,” as it had always done before that day he had had to choose between mother and wife. No; he could not speak.

But his wife chatted much and pleasantly — in a French, however, that must have been trying to old madame to listen to.

“I am so sorry, ma mère,” she said, “that our little one does not speak French. It is not my fault, I assure you,” and she flushed and hesitated a little. “It – it was Henri who would not permit it.”

“That is nothing,” replied madame, amiably, drawing the child close to her. “Her grandmother will teach her French; and she will teach her grandmother English. You see, I have no prejudices. I am not like my son. Henri was always a stubborn boy. Heaven only knows how he came by such a character!”

The post A Matter of Prejudice by Kate Chopin (1895) – full text appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

8 Iconic Poems by Elizabeth Bishop

Elizabeth Bishop (1911 – 1979) the noted American poet, was recognized with numerous awards during the course of her career, including the Pulitzer Prize. Here you’ll find 8 iconic poems by Elizabeth Bishop that are among her best known.

Not a particularly prolific writer, Bishop published only 101 poems during her lifetime. Her literary reputation has grown since her death, with iconic poems like “One Art,” “A Miracle for Breakfast,” “Sestina,” and “The Fish.”

As a poet, Bishop took great care to rewrite and revise her work. She didn’t give the reader much of a glimpse into her own life, but instead, her poems contained intimate observations of the physical world. She often expressed themes of loss and the struggle to find one’s place in the world in universal rather than personal way.

Her poetry stood in contrast to her contemporaries, including Robert Lowell and Anne Sexton, who, among others, were writing confessional poetry. She preferred to avoid personal disclosure in her work.

In his 2015 book, On Elizabeth Bishop, Irish author Colm Tóibín introduced her work:

“Writing, for Elizabeth Bishop, was not self-expression, but there was a self somewhere, and it was insistent in its presence yet tactful and watchful. Bishops writing bore the marks, many of them deliberate, of much re-writing, of things that had been said, but had now been erased, or moved into the shadows.

Things measured and found too simple and obvious, or too loose in their emotional contours, or too philosophical, were removed. Words not true enough were cut away.

What remained was then of value, but mildly so; it was as much as could be said, given the constraints. This great modesty was also, in its way, a restrained but serious ambition … In the poetics of her uncertainty … there was something hurt and solitary.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Elizabeth Bishop

. . . . . . . . . . .

For analysis of the poems of Elizabeth Bishop, in addition to the above slim volume by Colm Tóibín, these critical biographies are enlightening:

Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast by Megan Marshall (2017)

Elizabeth Bishop: Her Poetics of Loss by Susan McCabe (1994)

Becoming a Poet: Elizabeth Bishop with Marianne Moore and Robert Lowell by David Kalstone (1989)

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Map

Land lies in water; it is shadowed green.

Shadows, or are they shallows, at its edges

showing the line of long sea-weeded ledges

where weeds hang to the simple blue from green.

Or does the land lean down to lift the sea from under,

drawing it unperturbed around itself?

Along the fine tan sandy shelf

is the land tugging at the sea from under?

The shadow of Newfoundland lies flat and still.

Labrador’s yellow, where the moony Eskimo

has oiled it. We can stroke these lovely bays,

under a glass as if they were expected to blossom,

or as if to provide a clean cage for invisible fish.

The names of seashore towns run out to sea,

the names of cities cross the neighboring mountains

-the printer here experiencing the same excitement

as when emotion too far exceeds its cause.

These peninsulas take the water between thumb and finger

like women feeling for the smoothness of yard-goods.

Mapped waters are more quiet than the land is,

lending the land their waves’ own conformation:

and Norway’s hare runs south in agitation,

profiles investigate the sea, where land is.

Are they assigned, or can the countries pick their colors?

-What suits the character or the native waters best.

Topography displays no favorites; North’s as near as West.

More delicate than the historians’ are the map-makers’ colors.

— From North and South, 1946

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Fish

I caught a tremendous fish

and held him beside the boat

half out of water, with my hook

fast in a corner of his mouth.

He didn’t fight.

He hadn’t fought at all.

He hung a grunting weight,

battered and venerable

and homely. Here and there

his brown skin hung in strips

like ancient wallpaper,

and its pattern of darker brown

was like wallpaper:

shapes like full-blown roses

stained and lost through age.

He was speckled with barnacles,

fine rosettes of lime,

and infested

with tiny white sea-lice,

and underneath two or three

rags of green weed hung down.

While his gills were breathing in

the terrible oxygen

— the frightening gills,

fresh and crisp with blood,

that can cut so badly —

I thought of the coarse white flesh

packed in like feathers,

the big bones and the little bones,

the dramatic reds and blacks

of his shiny entrails,

and the pink swim-bladder

like a big peony.

I looked into his eyes

which were far larger than mine

but shallower, and yellowed,

the irises backed and packed

with tarnished tinfoil

seen through the lenses

of old scratched isinglass.

They shifted a little, but not

to return my stare.

— It was more like the tipping

of an object toward the light.

I admired his sullen face,

the mechanism of his jaw,

and then I saw

that from his lower lip

— if you could call it a lip

grim, wet, and weaponlike,

hung five old pieces of fish-line,

or four and a wire leader

with the swivel still attached,

with all their five big hooks

grown firmly in his mouth.

A green line, frayed at the end

where he broke it, two heavier lines,

and a fine black thread

still crimped from the strain and snap

when it broke and he got away.

Like medals with their ribbons

frayed and wavering,

a five-haired beard of wisdom

trailing from his aching jaw.

I stared and stared

and victory filled up

the little rented boat,

from the pool of bilge

where oil had spread a rainbow

around the rusted engine

to the bailer rusted orange,

the sun-cracked thwarts,

the oarlocks on their strings,

the gunnels — until everything

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!

And I let the fish go.

. . . . . . . . . . .

One Art

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster,

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

— Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

. . . . . . . . . . .

A Miracle for Breakfast

At six o’clock we were waiting for coffee,

waiting for coffee and the charitable crumb

that was going to be served from a certain balcony

— like kings of old, or like a miracle.

It was still dark. One foot of the sun

steadied itself on a long ripple in the river.

The first ferry of the day had just crossed the river.

It was so cold we hoped that the coffee

would be very hot, seeing that the sun

was not going to warm us; and that the crumb

would be a loaf each, buttered, by a miracle.

At seven a man stepped out on the balcony.

He stood for a minute alone on the balcony

looking over our heads toward the river.

A servant handed him the makings of a miracle,

consisting of one lone cup of coffee

and one roll, which he proceeded to crumb,

his head, so to speak, in the clouds–along with the sun.

Was the man crazy? What under the sun

was he trying to do, up there on his balcony!

Each man received one rather hard crumb,

which some flicked scornfully into the river,

and, in a cup, one drop of the coffee.

Some of us stood around, waiting for the miracle.

I can tell what I saw next; it was not a miracle.

A beautiful villa stood in the sun

and from its doors came the smell of hot coffee.

In front, a baroque white plaster balcony

added by birds, who nest along the river,

— I saw it with one eye close to the crumb–

and galleries and marble chambers. My crumb

my mansion, made for me by a miracle,

through ages, by insects, birds, and the river

working the stone. Every day, in the sun,

at breakfast time I sit on my balcony

with my feet up, and drink gallons of coffee.

We licked up the crumb and swallowed the coffee.

A window across the river caught the sun

as if the miracle were working, on the wrong balcony.

. . . . . . . . . . .

In the Waiting Room

In Worcester, Massachusetts,

I went with Aunt Consuelo

to keep her dentist’s appointment

and sat and waited for her

in the dentist’s waiting room.

It was winter. It got dark

early. The waiting room

was full of grown-up people,

arctics and overcoats,

lamps and magazines.

My aunt was inside

what seemed like a long time

and while I waited and read

the National Geographic

(I could read) and carefully

studied the photographs:

the inside of a volcano,

black, and full of ashes;

then it was spilling over

in rivulets of fire.

Osa and Martin Johnson

dressed in riding breeches,

laced boots, and pith helmets.

A dead man slung on a pole

“Long Pig,” the caption said.

Babies with pointed heads

wound round and round with string;

black, naked women with necks

wound round and round with wire

like the necks of light bulbs.

Their breasts were horrifying.

I read it right straight through.

I was too shy to stop.

And then I looked at the cover:

the yellow margins, the date.

Suddenly, from inside,

came an oh! of pain

— Aunt Consuelo’s voice–

not very loud or long.

I wasn’t at all surprised;

even then I knew she was

a foolish, timid woman.

I might have been embarrassed,

but wasn’t. What took me

completely by surprise

was that it was me:

my voice, in my mouth.

Without thinking at all

I was my foolish aunt,

I —we — were falling, falling,

our eyes glued to the cover

of the National Geographic,

February, 1918.

I said to myself: three days

and you’ll be seven years old.

I was saying it to stop

the sensation of falling off

the round, turning world.

into cold, blue-black space.

But I felt: you are an I,

you are an Elizabeth,

you are one of them.

Why should you be one, too?

I scarcely dared to look

to see what it was I was.

I gave a sidelong glance

–I couldn’t look any higher–

at shadowy gray knees,

trousers and skirts and boots

and different pairs of hands

lying under the lamps.

I knew that nothing stranger

had ever happened, that nothing

stranger could ever happen.

Why should I be my aunt,

or me, or anyone?

What similarities

boots, hands, the family voice

I felt in my throat, or even

the National Geographic

and those awful hanging breasts

held us all together

or made us all just one?

How I didn’t know any

word for it how “unlikely” . . .

How had I come to be here,

like them, and overhear

a cry of pain that could have

got loud and worse but hadn’t?

The waiting room was bright

and too hot. It was sliding

beneath a big black wave,

another, and another.

Then I was back in it.

The War was on. Outside,

in Worcester, Massachusetts,

were night and slush and cold,

and it was still the fifth

of February, 1918.

. . . . . . . . . . .

I Am in Need of Music

I am in need of music that would flow

Over my fretful, feeling fingertips,

Over my bitter-tainted, trembling lips,

With melody, deep, clear, and liquid-slow.

Oh, for the healing swaying, old and low,

Of some song sung to rest the tired dead,

A song to fall like water on my head,

And over quivering limbs, dream flushed to glow!

There is a magic made by melody:

A spell of rest, and quiet breath, and cool

Heart, that sinks through fading colors deep

To the subaqueous stillness of the sea,

And floats forever in a moon-green pool,

Held in the arms of rhythm and of sleep.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Sestina

September rain falls on the house.

In the failing light, the old grandmother

sits in the kitchen with the child

beside the Little Marvel Stove,

reading the jokes from the almanac,

laughing and talking to hide her tears.

She thinks that her equinoctial tears

and the rain that beats on the roof of the house

were both foretold by the almanac,

but only known to a grandmother.

The iron kettle sings on the stove.

She cuts some bread and says to the child,

It’s time for tea now; but the child

is watching the teakettle’s small hard tears

dance like mad on the hot black stove,

the way the rain must dance on the house.

Tidying up, the old grandmother

hangs up the clever almanac

on its string. Birdlike, the almanac

hovers half open above the child,

hovers above the old grandmother

and her teacup full of dark brown tears.

She shivers and says she thinks the house

feels chilly, and puts more wood in the stove.

It was to be, says the Marvel Stove.

I know what I know, says the almanac.

With crayons the child draws a rigid house

and a winding pathway. Then the child

puts in a man with buttons like tears

and shows it proudly to the grandmother.

But secretly, while the grandmother

busies herself about the stove,

the little moons fall down like tears

from between the pages of the almanac

into the flower bed the child

has carefully placed in the front of the house.

Time to plant tears, says the almanac.

The grandmother sings to the marvelous stove

and the child draws another inscrutable house.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Bishop page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Florida

The state with the prettiest name,

the state that floats in brackish water,

held together by mangrove roots

that bear while living oysters in clusters,

and when dead strew white swamps with skeletons,

dotted as if bombarded, with green hummocks

like ancient cannon-balls sprouting grass.

The state full of long S-shaped birds, blue and white,

and unseen hysterical birds who rush up the scale

every time in a tantrum.

Tanagers embarrassed by their flashiness,

and pelicans whose delight it is to clown;

who coast for fun on the strong tidal currents

in and out among the mangrove islands

and stand on the sand-bars drying their damp gold wings

on sun-lit evenings.

Enormous turtles, helpless and mild,

die and leave their barnacled shells on the beaches,

and their large white skulls with round eye-sockets

twice the size of a man’s.

The palm trees clatter in the stiff breeze

like the bills of the pelicans. The tropical rain comes down

to freshen the tide-looped strings of fading shells:

Job’s Tear, the Chinese Alphabet, the scarce Junonia,

parti-colored pectins and Ladies’ Ears,

arranged as on a gray rag of rotted calico,

the buried Indian Princess’s skirt;

with these the monotonous, endless, sagging coast-line

is delicately ornamented.

Thirty or more buzzards are drifting down, down, down,

over something they have spotted in the swamp,

in circles like stirred-up flakes of sediment

sinking through water.

Smoke from woods-fires filters fine blue solvents.

On stumps and dead trees the charring is like black velvet.

The mosquitoes

go hunting to the tune of their ferocious obbligatos.

After dark, the fireflies map the heavens in the marsh

until the moon rises.

Cold white, not bright, the moonlight is coarse-meshed,

and the careless, corrupt state is all black specks

too far apart, and ugly whites; the poorest

post-card of itself.

After dark, the pools seem to have slipped away.

The alligator, who has five distinct calls:

friendliness, love, mating, war, and a warning–

whimpers and speaks in the throat

of the Indian Princess.

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 8 Iconic Poems by Elizabeth Bishop appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 7, 2020

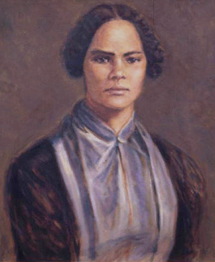

Grazia Deledda

Grazia Maria Cosima Damiana Deledda (September 1871 – August 15, 1936), more commonly known as Grazia Deledda, was an Italian writer best known for being the first Italian woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature (1926).

She was praised “for her idealistically inspired writings which with plastic clarity picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general.”

Early life

Deledda was born in Nuoro, Sardinia, the second-largest island in the Mediterranean sea. Her parents, Giovanni Antonio Deledda and Francesca Cambosu Pereleddu, were a respectable middle-class couple. They started educating Deledda in literature at a very young age.

After attending elementary school, she stopped formerly attending school at the age of eleven, as a guest of one of her relatives started to privately tutor her. It wasn’t long before she discovered her passion for writing, and she continued to independently study literature after being inspired by Sardinian peasants and their challenging lives.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The start of a writing career

Deladda’s first published work was Nell’azzurro, published in 1890. She also he published several pieces in L’Ultima Moda when the fashion magazine was still publishing prose and poetry.

Deledda was only twenty-one years old when she wrote and published her first novel, Fiori di Sardegna (Flowers of Sardinia), in 1892. Four years after she published her first novel, Paesaggi Sardi was published in 1896.

Her work shed light on the harsh realities in the lives of individuals, and wove in imaginary and autobiographical elements. Her writing reflected her critical views of social values and norms and how they victimized ordinary people.

Deladda’s family grew unsupportive of Deledda’s writing. She was unfazed by their lack of support, and continued to produce works reflecting her beliefs, no matter how controversial.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Family life and rise to fame

Deledda met Palmiro Madesani, a functionary of the Ministry of Finance, in Cagliari in October of 1899. The two married in 1900 and moved to Rome.

After the publication of Anime Oneste in 1895, II vecchio della montagna in 1900, and the many works she collaborated on with magazines such as La Sardegna, Piccola Rivista, and Nuova Antologia, her work began to gain recognition.

While her writing career was taking off, she had two sons, Franz and Sardus, and lived a rather quiet life. She worked efficiently, as on average, she published a novel per year.

In 1903, Deledda published her most successful work to date. Elias Portolu officially established her career as a writer. She began successfully writing novels and theatrical works, such as Cenere (1904), L’edera (1908), Sino al confine (1910), Colombi e sparvieri (1912), and more.

Cenere, was actually the inspiration for a silent movie with Eleonora Duse, a well-known Italian stage actress. It happened to be the only time that Duse appeared in a film.

. . . . . . . . . .

14 Women Who Won the Nobel Prize in Literature

. . . . . . . . . .

The Nobel Prize in Literature

In 1926, Deledda made history as the first Italian recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature after being nominated by Henrick Schuck, a member of the Swedish Academy. When learning that she would be awarded the prestigious prize, Deledda’s response was “Gia!” (“Already!”)

Almost exactly one year after Benito Mussolini dropped the charade of constitutional rule in favor of fascism, Deledda received the Nobel Prize. He insisted on giving her a portrait of himself and signed it with “profound admiration.” In the midst of her heightened fame, many journalists and photographers visited her home, hoping to learn more about this prolific writer.

Deledda was deeply passionate about writing and was strict about dedicating a few hours of writing to her routine. Her daily schedule was exactly the same throughout the entire week. She started her day with a late breakfast, read for a few hours, had lunch and a nap, and ended her day with a few hours of writing.

She was extremely fond of her pet crow, Checcha. He often became agitated with the huge crowd of photographers and visitors constantly stopping by Deledda’s home. She would often be quoted as saying “If Checcha has had enough, so have I.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Staying positive through hard times

Deledda continued writing as she grew older. In her later yers, she created two collections of short stories titled La Casa del Poeta and Sole d’Estate. Her work often expressed a positive view of life despite her own suffering from painful illnesses.

She didn’t allow the her work to touch on her personal suffering, and instead, focused on the beauty that life had to offer. Most of her later works describe mankind and her faith in God in beautiful terms.

Deledda’s work reflected on the life, customs, and traditions of the Sardinian people and used geographical descriptions and detail in her work. Many of her characters are social outcasts who struggle with loneliness, much like the Sardinian peasants that inspired her passion for writing as a young girl.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Themes in Deledda’s work

In Deledda’s novels, there are connections between people and places and between feelings and the environment. One can often recognize the influence of verism, the artistic preference for everyday subject matter, as opposed to the heroic or legendary.

Her work also depicts decadentism, an Italian artistic style based on the Decadent movement in the arts in nineteenth-century France and England, especially the works of Gabriele D’Annunzio.

Deledda’s themes of women’s pain and suffering rather than on their autonomy, didn’t help to gain her much recognition as a feminist writer.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Grazia Deledda page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Death and legacy of Grazia Deledda

Deledda died of breast cancer in Rome in 1936, at the age of sixty-four. Just before her death, she was able to complete her final novel, La Chiesa della Solitudine (1936), a semi-autobiographical story about a young Italian woman who learns she has breast cancer. After her death, her completed manuscript of the novel Cosima was discovered and published in 1937

Her work has since been praised by Luigi Capuana and Giovanni Verga, as well as many other writers and critics. Her birthplace and childhood home located in Nuoro was created into a museum in the writer’s honor called Museo Deleddiano di Nuoro, consisting of ten rooms used to reconstruct stages of her life.

To this day, Deledda remains the only Italian woman to have won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

. . . . . . . . . .

Major works

From Stella D’Oriente and Nell’azzurro, both published in 1890, through a number of posthumously published works, it would be unwieldy to list all of Deledda’s works here. See a complete listing of her works on Wikipedia.

Biographies

A Self-Made Woman: Biography of Nobel-Prize-Winner Grazia Deledda by Carolyn Balducci (1975)

Grazia Deledda: A Legendary Life (Troubador Italian Studies) by Martha King (2005)

More Information

Wikipedia

The Famous People

Britannica

The Nobel Prize

With Profound Admiration: Grazia Deledda, Nobel Laureate

. . . . . . . . . .

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Grazia Deledda appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 21, 2019

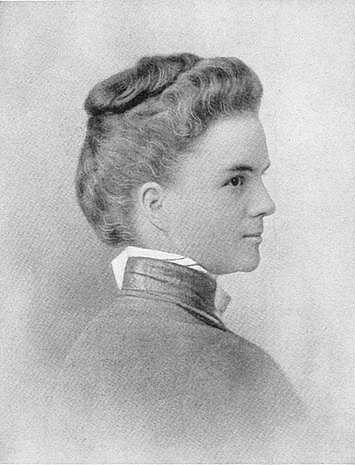

Elizabeth Bishop

Elizabeth Bishop (February 8, 1911 – October 6, 1979) was a noted American poet. Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, Bishop won numerous awards during the course of her career, including the Pulitzer Prize, and her reputation as a significant American poet has only grown since her death. Her most iconic poems include “The Fish,” “One Art,” “A Miracle for Breakfast,” and “Sestina.”

Bishop wasn’t a particularly prolific poet, preferring to spend long periods of time revising her work; she wrote just over one hundred poems. Her poetry is characterized by keen observations of the physical world and a serene yet searching attitude. Many of her poems grapple with themes of loss and the struggle to find one’s place in the world.

Early life and education

Elizabeth Bishop’s experiences of loss began early. Her father died when she was an infant; her mother suffered from severe mental illness and was committed to an institution when Bishop was five. She was raised by her maternal grandparents in Nova Scotia for several years before being taken in by her paternal grandparents, who brought her back to Massachusetts.

Bishop was unhappy living with her grandparents. Recognizing her sadness, they sent her to live with her mother’s oldest sister. Bishop’s aunt was the first to expose her to poetry, especially the Victorian poets, including Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

Because her grandparents were wealthy and paid for her education, Bishop was able to attend the elite Walnut Hill School, where she studied music. It was at Walnut Hill that her first poems were published in a student magazine.

Bishop then attended Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, studying music with the intention of becoming a composer. Performance anxiety redirected her toward a degree in English. As the editor-in-chief of Vassar’s yearbook, Bishop and a group of friends — including her classmate, future novelist Mary McCarthy — founded the literary magazine Con Spirito. Though short-lived, it was able to compete with Vassar’s established magazine. Bishop graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1934.

. . . . . . . . . .

1934 Vassar College yearbook portrait

. . . . . . . . . .

Literary friendships and correspondences

While Bishop studied English, a librarian introduced her to the poet Marianne Moore. The two corresponded extensively, and Moore became Bishop’s mentor and lifelong friend. She helped publish Bishop’s poetry in the anthology Trial Balances, in which established poets promoted new and unknown poets. Their friendship lasted until Moore’s death in 1972.

In 1947, poet and critic Randall Jarrell introduced Bishop to Robert Lowell, and they became close friends. Bishop and Lowell often wrote poems inspired by the other’s work. Lowell’s famous “Skunk Hour,” for example, was inspired by Bishop’s “The Armadillo,” and Bishop’s “North Haven” paid homage to Lowell after his death.

Bishop had numerous correspondents over her lifetime. She found letter-writing a joyous activity and an extension of her poetry. Over five hundred of her letters to Moore, Lowell, and others have been collected in the volume One Art: Letters.

World travels and a poet’s beginnings

With an inheritance from her deceased father’s estate, Bishop was able to travel widely after graduating from Vassar. She first lived in New York City for several years, and then visited Italy, Ireland, France, Spain, and North Africa. Bishop described many of the places she lived in her poems, such as in “Questions of Travel” and “Over 2000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance.”

In 1938, Bishop purchased a home in Key West, Florida with a friend from Vassar. There, she began work on her first poetry collection, North and South. The book was published in 1946; it won the Houghton Mifflin prize for poetry.

1951 brought Bishop the opportunity to embark on deeply impactful travels. With a travel fellowship of $2,500 she was awarded by Bryn Mawr College, she circumnavigated South America by boat. Bishop arrived in Santos, Brazil in November of 1951; she intended to stay for only two weeks, but instead stayed for fifteen years.

Life and love in Brazil

Bishop’s relationship with architect Lota de Macedo Soares is what kept her in Brazil. When Bishop was sick during her initial two-week visit, Soares nursed her back to health, effectively winning over the poet. Soares was descended from a prominent and political family; though not trained as a designer or architect, she worked as both. The couple lived together in Pétropolis, near Rio de Janeiro.

Though it began blissfully, the women’s relationship deteriorated after about fourteen years. Their later years together were marked by recurring bouts of Bishop’s alcoholism and Soares’s depression, making both were prone to start volatile fights.

Bishop moved back to New York to teach in 1966. Her alcoholism eventually led to infidelity. Soares visited Bishop in 1967; on the first day of their reunion, she took her own life, possibly due to stress from work and the couple’s failing relationship.

Bishop wasn’t forthcoming about the nature of her relationship with Soares, and she never came out as a lesbian. Much of what’s known about their relationship comes from Bishop’s letters to professor Samuel Ashley Brown. Their relationship was memorialized in the book Flores Raras e Banalíssimas (in English, Rare and Commonplace Flowers) by Carmen Lucia de Oliveira, and the 2013 film Reaching for the Moon.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Building a literary identity

While living in Brazil, Bishop published her second collection of poems, North and South — A Cold Spring. The collection appeared in 1955 and included her first book, plus eighteen additional poems that made up the Cold Spring section. Bishop won the Pulitzer Prize for this volume the following year.

It would be another ten years before Bishop published any new poems. Her next book was 1965’s Questions of Travel, and many of the poems in this collection were inspired by her life in Brazil, such as “Arrival at Santos” and “The Riverman.”

Bishop’s contemporaries, including Robert Lowell and Anne Sexton, among others, were writing confessional poetry, but she avoided personal disclosure in her work. Preferring a more objective style, the narrative voices in her poems are often distant from the subject matter, describing their observations in precise yet impersonal detail. In the March 6, 2017 issue of The New Yorker, an article titled “Elizabeth Bishop’s Art of Losing” (reviewing A Miracle for Breakfast: The Art of Elizabeth Bishop, a biography of the poet by Megan Marshall) bears out this general assessment of her work:

“Except perhaps for her mentor, Marianne Moore, it is hard to name a poet whose work so thoroughly disinvites private scrutiny. Admirers of Bishop’s early work Moore, Robert Lowell, Randall Jarrell—praised its cool objectivity, its calm impersonality, what Moore described as its ‘rational considering quality’ (hardly the usual praise for poetry), its ‘deferences and vigilances.’ What the young poet deferred to was poetic form and an increasingly old-fashioned sense of manners and discretion. She was vigilant in giving nothing of herself away.”

Bishop’s next major publication was her Collected Poems, published in1969. The volume included her previously published poetry, plus eight new poems. It won the National Book Award. The following book and the last to be published in Bishop’s life, Geography III, contains many of her most anthologized poems, such as “One Art” and “In the Waiting Room.”

Bishop continued to reject confessional poetry when this collection came out in 1977, but some sparse personal details began to surface, hinting at her mother’s illness and her grief after losing Soares. Bishop won the Neustadt International Prize for Literature for Geography III, which no woman had won before and no American has won since.

Not a “Woman Poet”

Bishop had a fraught relationship with how gender and sexuality related to her career as a poet. She refused the labels “female poet” or “lesbian poet,” preferring her work to speak for itself rather than be overshadowed by her gender or sexual orientation.

Being an intensely private person, Bishop was never involved in the women’s movement and shared intimate details of her life with few people. As a result, those around her thought she was hostile to the women’s movement. However, Bishop stated in a 1978 interview with The Paris Review that although she refused to be published in women-only anthologies, she did consider herself a feminist.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Bishop page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Awards, accolades, and later years

When her father’s inheritance began dwindle in the 1970s, Bishop started lecturing at various universities. She taught at Harvard for several years, then at New York University, and finally the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

During her lifetime, she may not have been famous per se, but her work was recognized and well rewarded. Starting in 1945 with the Houghton Mifflin award for her first collection, she went on to win a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Shelley Memorial Award, an Academy of American Poets Fellowship, the National Book Award for Poetry, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and many others, not the least of which was the Pulitzer Prize mentioned earlier.

In 1979, Bishop died of a cerebral aneurysm in her apartment in Boston, at the age of 68. Her partner of some eight years, Alice Methfessel, became her literary executor.

Ultimately, Elizabeth Bishop achieved what she had hoped for — a reputation as a great American poet, who just happened to be a woman.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Elizabeth Bishop

Major Works

North & South ( 1946)

Poems: North & South / A Cold Spring (1955)

A Cold Spring (1956)

Questions of Travel (1965)

The Complete Poems (1969)

Geography III (1976)

The Complete Poems: 1927–1979 (1983)

Poems, Prose and Letters by Elizabeth Bishop (2008)

Poems (2011)

Biography, letters, and criticism

The Collected Prose (1984)

One Art: Letters (1994)

Exchanging Hats: Elizabeth Bishop Paintings, (1996)

Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell (2008)

Conversations with Elizabeth Bishop (1996)

A Miracle for Breakfast: The Art of Elizabeth Bishop by Megan Marshall (2017)

Love Unknown: The Life and Worlds of Elizabeth Bishop by Thomas Travisano (2019)

Documentary

Welcome to this House (2015)

More information and sources

Wikipedia

Poets

Poetry Foundation

A Conversation with Elizabeth Bishop

Alone with Elizabeth Bishop

It’s Always a Good Time to Revisit the Brilliance of Elizabeth Bishop

Visit and research

Elizabeth Bishop House and Society of Nova Scotia

The Elizabeth Bishop Papers at Vassar College

Contributed by Johanna Shaw. Johanna Shaw is a writer currently pursuing an M.A. in English at the University at Albany, SUNY. Her essays have appeared in bioStories, Trolley, Gravel, and Glass Mountain. When not writing or studying, Johanna can be found playing Chopin nocturnes at her piano, obsessing over literary modernism, or somewhere deep within a used bookstore.

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Elizabeth Bishop appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 16, 2019

Seven Gothic Tales by Isak Dinesen (1934)

Seven Gothic Tales by Isak Dinesen (1885 – 1962) is a masterful collection of short stories by the Danish author best known for Out of Africa (1937), a now-controversial memoir of her life as a coffee plantation owner in the colonized Kenya of the 1920s.

In 1931, the plantation’s fortunes collapsed, and she returned to her family home in Denmark from Kenya. Karen Christenze Dinesen was the author’s original name, and she was known as Baroness Karen von Blixen-Finecke, or simply Karen Blixen, during her disastrous marriage. Upon her return to her home country, she began writing in earnest. In 1934, Seven Gothic Tales, a collection of stories she had written in English, was published.

A surprise success by a Danish author in the U.S.

Seven Gothic Tales was a surprise success in the U.S., even becoming a Book-of-the-Month-Club selection. It set the stage for the thematic character of her fiction, which was an amalgam of the real and the mythic, and incorporating elements of Persian and West Indian exotica. Storytelling is actually a part of some of her stories — that is, stories are told within the stories; and characters are sometimes archetypes rather than fully fleshed-out people. She wrote of her work:

“Reality had met me … in such an ugly shape, that I have no wish to come into contact with it again. Somewhere in me a dark fear was still crouching and I took refuge within the fantastic like a distressed child in his book of fairy tales …

I belong to the ancient, idle, wild, and useless tribe, perhaps I am even one of the last members of it, who, for many thousands of years, in all countries and parts of the world, has, now and again, stayed for a time among the hard working honest people in real life, and sometimes has thus been fortunate enough to create another sort of reality for them, which, in some way or another, has satisfied them. I am a storyteller … ”

The use of the term gothic

Commenting on the designation of these tales as gothic, the Karen Blixen Museum offers this insight:

“Some of the foremost Anglo-Saxon authors of 19th century had written Gothic tales and novels: Robert Louis Stevenson, Charlotte Brontë, Jane Austen, Edgar Allan Poe and William Faulkner – all of whom feature in Karen Blixen’s private library. Karen Blixen adopted a very free approach to the traditional Gothic genre, but she worked within a number of its parameters.

The themes of Gothic novels include: the collapse of feudal aristocracy; young heroes and heroines held captive in ancient castles and convents by powerful and manipulative men; the tyranny of the past stifling the hopes of the present generation. Women writers were especially fond of the genre – presumably because its traditional themes of oppression and persecution went hand-in-hand with women’s experience of lack of freedom and independence in a patriarchal society.”

Endeavoring to describe the indescribable

In her introduction to the 1934 Modern Library edition of Seven Gothic Tales, Dorothy Canfield Fisher endeavors to describe the unusual flavor, so to speak of the tales:

“Although solidly set in an admirably described factual background somewhere on the same globe we inhabit, in a past mostly no longer ago than sometime in the nineteenth century, although they are human beings, young men, maidens, old men, old women, they are unlike us and the people we know in books and in real life, because the attitude towards life which they have is different from ours, or from any attitude we have met in life or in books …

Where, you will ask yourself, puzzled, have I ever encountered such strange slanting beauty of phrase, clothing such arresting but controlled fantasy? As for me, I don’t know where.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Isak Dinesen

. . . . . . . . . .

The following 1934 review reflects the accolades the book received in the U.S., even as reviewers attempted to define the ineffable quality of the writing:

A 1934 review of Seven Gothic Tales

From the original review of Seven Gothic Tales by Isak Dinesen in The Salt Lake Tribune, April 29, 1934: One will find much difficulty in assaying this volume, in determining just wherein lies ints peculiar fascination. These Seven Gothic Tales, or novelettes, as they might be called have nothing of the manner or style of anything else being written contemporaneously.

There is an air of classicism about them, a suggestion of Bocaccio, of the German romantics, or even the richness of Scheherazade’s tales. Yet only a suggestion; they’re truly unlike anything else one can recall. The author takes us into a world peopled by characters that are strange to us, and who have a way of life that’s unfamiliar.

Filled with Danish history, lore, and legend

Isak Dinesen comes of an old Danish family, we are told, and while she chooses to write in English, it’s a Continental attitude of mind that’s revealed. Some of her tales are filled with Danish history, lore, and legend.

In “The Roads Round Pisa,” it is a young Danish nobleman who, seeking in a journey to Tuscany to learn something of the truth about himself, becomes a spectator at a curious chain of events. For this, as for any of the other tales, a proper preface might be found in the words of a character in “The Dreamers” — “It happened just as I tell it to you … You must take in whatever you can, and leave the rest outside. It is not a bad thing in a tale that you can understand only half of it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Babette’s Feast, the 1958 Short Story by Isak Dinesen and 1987 Film

. . . . . . . . . .

Slightly grotesque characters grip the imagination

While the actors in these tales are strange, slightly grotesque, and their experiences fantastic, they grip the imagination. The Gothic mood of the stories grows on us, and while we read we’re bound by the author’s spell, and see these people as she saw them, as though she held some secret vision that we may not share.

All of the tales are set back in previous century, and are intricate in structure, designed like some exquisite early mosaic. “The Dreamers,” full of mystical meaning, tells of the beautiful opera singer who, grieving the loss of her voice, gives up her personality also. She becomes more than one person, a woman who never grows old.

Peculiar qualities of family and romance

That is also the peculiar quality of the family in “The Supper at Elsinore.” Two brilliant sisters, like a “pair of spiritual courtesans,” still keep their admirers; the pirate brother who returns long after his death to call upon these two women who loved him in a strange tryst.

A tinge of eroticism marks most of the tales, most especially “The Monkey.” In this tale, a noble Prioress goes to strange lengths to arrange a marriage to save a dissolute nephew, and a small gray monkey plays a weird part. At dinner with the young woman he is to marry, the thoughts of Boris, the nephew, are described:

“He thought that she must have a lovely, an exquisitely beautiful skeleton. She would lie in the round like a piece of matchless lace, a work of art in ivory … he imagined that he might be very happy with her, that he might even fall in love with her, could he have her in her beautiful bones alone … Many human relations, he thought, would be infinitely easier if they could be carried out in the bones only.”

Delicate beauty of writing

In “The Deluge at Norderney,” the most arresting of the tales, the flood that destroyed a coast town of Holstein — coming in summertime, it assumed “the character of a terrible, grim joke” — becomes the setting for the stories of four people: a cardinal who wasn’t a cardinal, a half-mad spinster of the noble Nat-of-Dag, and two unusual young people. These four are revealed during the hours of the night while the waters rise to the loft where they take shelter.

More than the unexpectedness of these tales, with their startling grotesqueries and fantastic incident, is the delicate beauty of the writing. This mysterious Danish author has mastered an exquisite prose style.

. . . . . . . . . .

Seven Gothic Tales by Isak Dinesen on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Seven Gothic Tales by Isak Dinesen

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Margaret Atwood on the Show-Stopping Isak Dinesen

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Seven Gothic Tales by Isak Dinesen (1934) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 8, 2019

12 African-American Suffragists Who Shouldn’t be Overlooked

The women’s suffrage movement in the United States led to the establishment of the legal right for women to vote nationally when the 19th amendment was ratified 1920. Here we present twelve African-American suffragists whose contributions shouldn’t be overlooked, a mere fraction of those who should be acknowledged and honored.

As women’s suffrage gained momentum in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, African-American women often were marginalized. Yet despite the odds, Black suffragists made important strides in the fight for voting rights. African-American women suffragists dealt with the political concerns of white suffragists who were aware that they needed the support of Southern legislators both on the state and federal levels.

In 1890, the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). NAWSA’s members excluded African-American women, believed that would gain them greater support. The view of women’s suffrage was thus narrowed, focusing primarily on white women.

Racism was as much an issue in the right to secure the vote for Black women as was sexism. Susan Goodier and Karen Pasternello, the authors of Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State, observed:

“They [Black women] did not rely on white women to tell them they needed the right to vote; they began organizing for the franchise in New York State as early as the 1880s and, in spite of the racism they faced, they would actively seek their enfranchisement throughout the entire struggle. African-American women rarely separated the quest for the vote from the other activism in which they engaged.

Many Black women came to fear that white women would ‘devise something akin to an exclusionary ‘grandmother’s clause’ to keep Black women from voting once they won the vote. Some scholars argue that, in fact, ‘racist attitudes provided additional impetus” for Black women’s struggle.

Much of their activism and work for woman suffrage and women’s rights occurred as a fundamental component of their activities in clubs such as the Negro Women’s Business League or in the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs or its affiliates …”

Though there were many obstacles in the way, African-American women fought tirelessly on all fronts secure the vote. Thanks to the devoted and determined women who participated in the women’s suffrage movement and helped it progress, women gained the right to make their voices heard through voting, at least on paper. The passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, unfortunately, didn’t end the fight for voting rights for all women, as we well know.

. . . . . . . . . .

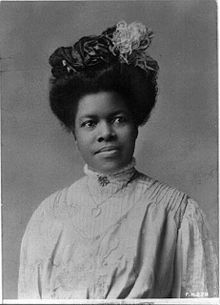

Nannie Helen Burroughs (1871-1961)

Nannie Helen Burroughs was born in north-central Virginia and later attended school in Washington, D.C., where she graduated with honors. Due to racial bias, she was unable to find a job, neither in the D.C. schools, nor the federal government.

She relocated to Philadelphia and worked as a secretary for the Christian Banner, the National Baptist Convention’s paper. This experience motivated her to advocate for civil rights for African-Americans and women. One result was her founding the National Training School for Women and Girls.

Burroughs believed women should be given a fair opportunity to get an education and job training. She also discussed the need for Black and white women to unite in the fight voting rights; she strongly believed that suffrage for African-American women was necessary to protect their interests. In society which was often racist, she believed a Black woman’s vote was an essential antidote to racial and gender discrimination.

She left behind an impressive legacy, which included assisting Black women of the suffragist movement when they went through hard times. She’s also one of the most quoted suffragists of her time. One of her most memorable quotes was “Having standards isn’t really for anyone else. You should want to have them for yourself.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823 – 1893)

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was born into a family that lived to help others. As she grew up, her family was actively helping those seeking to escape slavery by participating in the Underground Railroad. This became ever more urgent after the Fugitive Slave Act was passed by Congress in 1850. Her drive toward social justice followed her into adulthood, as she became involved in the women’s suffrage movement among many other causes.

While in Washington D.C, she became a member of the National Woman Suffrage Association and spoke at their convention in 1878. She worked alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony to testify before the House Judiciary Committee and founded the Colored Women’s Progressive Franchise in 1880 to push for equal rights for women.

Cary strongly advocated for the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments at a House Judiciary Committee hearing. The Fourteenth Amendment defined citizenship and the Fifteenth Amendment gave African-American men the right to vote. Though she supported the Fifteenth Amendment, she was vocal in her criticism of this amendment that left women out. Her hard work and dedication paid off when she testified before the U.S. House Judiciary Committee on Women and the Vote, after which she registered to vote in Washington, D.C.

. . . . . . . . . .

Coralie Franklin Cook (1861 – 1942)

Coralie Franklin Cook was an outspoken leader in the African-American community, best known in West Virginia and Washington, D.C. She was a very powerful public speaker, a professor, appointed Board of D.C, a leader in the Black women’s club movement.

She focused primarily on issues of women’s suffrage and education. She was an active member of the National American Woman Suffrage Association and took part in participating in the association’s inner circles. The NAWSA hierarchy acknowledged her hard work, though rather patronizingly praised her as an educated, professional, middle-class woman who she matched the intelligence of Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Cook was disheartened by the reality that African-American women weren’t a priority for white women active in the suffrage movement and insisted that they do not ignore the political rights of the less fortunate.

She even addressed Susan B. Anthony, saying “…and so Miss Anthony, on behalf of the hundreds of colored women who wait and hope with you for the day when the ballot shall be in the hands of every intelligent woman; and also in behalf of the thousands who sit in darkness and whose condition we shall expect those ballots to better, whether they be in the hands of white women or Black, I offer you my warmest gratitude and congratulations.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Anna Julia Cooper (1858 – 1964)

Anna Julia Cooper (1858 – 1964) was born to a house slave named Hannah Stanley Haywood in Raleigh, North Carolina. In the course of her long life, she lived through slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and the early Civil Rights movement. She also lived to see the fruits of the women’s suffrage movement.

Not only was Cooper an author and educator, but she was also a social commentator. She participated in numerous conferences, including Woman Suffrage Congress in 1893, where she delivered formidable speeches focusing on racial and gender equality and education. She was among one of the most dedicated of African-American women suffragists.

Cooper encouraged women of color to push back against the belief that a Black man’s experiences and needs were the same as theirs. They needed a voice — and a vote — of their own. She became known for her statement, “Only the BLACK WOMAN can say when and where I enter in the quiet undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence or special patronage; then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Charlotte Forten Grimké (1837 – 1914)

Charlotte Forten Grimké married Presbyterian minister Francis J. Grimké, making her the aunt of Harlem Renaissance poet and journalist Angelina Weld Grimké. She was an abolitionist and diarist who grew up in a prominent and abolitionist family of color in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Grimké was an influential activist and civil rights leader. In 1892 she formed the Colored Women’s League in Washington, D.C. as a service-oriented club working to promote unity, social progress, and other interests of the Black community. She contributed much to the formation of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896.

Even as she grew older, she continued to speak publicly on abolitionist issues and also arranged lectures for other prominent speakers. Grimké continued to stay an active force advocating for the rights of African-Americans until the time of her death.

. . . . . . . . . .

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825 – 1911)

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper combined her talents as a writer, poet, and public speaker with a deep commitment to abolition and social reform. She was an avid supporter of progressive causes both before and after the American Civil War, including prohibition and women’s suffrage.

Her life changed after a trip to the South when she witnessed the mistreatment of Black women during Reconstruction. She gave lectures on the need for racial equality along with women’s rights. Years later, she founded the YMCA Sunday Schools and become the leader in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. She also joined the American Equal Rights Association and the American Woman’s Suffrage Association to help fight for racial and women’s equality.

In 1866, Harper gave a speech demanding equal rights for everyone, including Black women, before the National Woman’s Rights Convention. She stated:

“We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul. You tried that in the case of the Negro … You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs. I, as a colored woman, have had in this country an education which has made me feel as if I were in the situation of Ishmael, my hand against every man, and every man’s hand against me …”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Adella Hunt Logan (1863 – 1915)

Adella Hunt Logan was an African-American writer, educator, administrator, and suffragist. She was active in advocating for education and voting rights for women of color.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association held a convention in Atlanta in 1895. At the time, the organization was having a difficult time gaining support for a constitutional amendment on women’s suffrage, so they turned to southern states for help. NAWSA appealed to white southerners because it observed segregation and had previously barred African-American men and women from their conventions.

Around this time, Mississippi and other southern states had passed a constitution to disenfranchise Black citizens through 1908. Although the atmosphere was extremely unwelcoming to African-Americans, Logan attended the convention. She was inspired by a speech by Susan B. Anthony and became a member shortly after.

She began writing for NAWSA’s newspaper, The Woman’s Journal, and contributed to other magazines (including NAACP’s The Crisis) to promote women’s suffrage. Logan also campaigned for women’s voting rights in western states that had statewide suffrage, and argued that African-Americans should have the right to vote in order to have a say in education legislation.

Though her life ended sadly in depression and suicide, Logan’s contributions to the cause of suffrage were significant.

. . . . . . . . . .

Gertrude Bustill Mossell (1855 – 1948)

Gertrude Bustill Mossell was a journalist, author, teacher, activist, and suffragist. She was able to utilize her skills as a writer to give a voice to the ideas of Black women who advocated for women’s suffrage.

Although Mossell came from a comfortable family, she chose to give a voice to African-American women suffragists who were often ignored. She began supporting the women’s suffrage movement when she began writing a woman’s column for T. Thomas Fortune’s Black newspaper, The New York Freeman. Her first article for the column was “Woman Suffrage,” which encouraged Black women to educate themselves about the movement and get involved to work for its success.

She also encouraged women to become journalists to write articles for numerous publications and share their views on current events. Mossell personally favored the Constitutional amendment route favored by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton over the state-by-state method favored by Lucy Stone.

. . . . . . . . . .

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin (1842 – 1924)

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was a journalist, publisher, civil rights leader, editor of the Woman’s Era, and suffragist. She was best known for creating the club movement that encouraged Black women to fight for civil rights and suffrage.

Ruffin joined Julia Ward Howe and Lucy Stone to create the American Woman Suffrage Association in Boston. She became the first Black member of the New England Women’s Club, a group created by Howe, Stone, and other AWSA members, when she joined in the mid 1890s.

After Massachusetts granted women the right to vote in School Committee elections, she became the founder of the Massachusetts School Suffrage Association. Here, she advocated for women’s suffrage and candidacy for office. Years later, she became the President of the West End League of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association.

. . . . . . . . . .

Mary B. Talbert (1866 – 1923)

Mary B. Talbert (also known as Mary Burnett Talbert) was an American orator, reformer, activist, and suffragist called “the best known Colored Woman in the United States,” as she was one of the most distinguished African-Americans of her time.

In 1905, W.E.B Dubois, John Hope, and thirty others secretly met in Talbert’s home to discuss the civil rights resolution that eventually led to the founding of the Niagara Movement. Dubois stated: “We want full manhood suffrage and we want it now …” Though Talbert was unable to become a member of the Niagara Movement, it served its purpose as the forerunner of the NAACP. The latter allowed her to become a vice president and a board member of the organization from 1919 until her death.

Talbert used the media of the day to educate the public about suffrage and persuade African-American women to fight for their right to vote. In a 1915 article in The Crisis she wrote, “It should not be necessary to struggle forever against popular prejudice, and with us as colored women, this struggle becomes two-fold, first because we are women and second because we are colored women.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Mary Church Terrell (1863 – 1954)

Mary Church Terrell, the well-known activist for civil rights, was one of the first African-American woman to earn a college degree. Her interest in suffrage began when she was an Oberlin College student, and she continued her involvement in many aspects of activism into her later years.

As a member of NAWSA, Terrell created a group of African-American women to combat racial issues such as lynching, educational reform, and more.

Terrell gave a speech called “The Progress of Colored Women” at a NAWSA session in Washington, D.C. as a call for the association to fight for Black women’s lives. The speech received a great response from the association which led Terrell to serve as their unofficial African-American ambassador. She went on to give other addresses aimed at uniting Black people in various causes.

Terrell led the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority women of Howard University in a suffrage rally, and became the first Black woman to hold a position in the District of Columbia Board of Education.

. . . . . . . . . .

Ida B. Wells (1862 – 1931)