Nava Atlas's Blog, page 56

April 22, 2020

Books by Anaïs Nin for a New Generation: Recent Publications by Swallow Press

Anaïs Nin (1903 – 1977), an iconic literary figure of the 20th century, was best known for her Diary series. A trove of books by Anaïs Nin has recently been reissued in updated editions by Swallow Press, the premier U.S. publisher of her works.

Swallow Press is a division of Ohio University Press, and many of these updated editions have been edited by Paul Herron. As founder and editor of Sky Blue Press, Herron publishes the journal A Café in Space and digital editions of the fiction of Anaïs Nin, as well as a new collection of Nin erotica, Auletris.

Born in France, Nin was by heritage Cuban-American; her full name was Angela Anaïs Juana Antolina Rosa Edelmira Nin y Culmell. Best known for her multi-volume series, The Diary of Anaïs Nin, she wrote these journals over the span of more than thirty years (not including her Early Diaries series).

Nin became a feminist icon in the 1970s once a number of volumes of the Diary series were published. They became a touchstone for female readers, and have come to define a large part of Nin’s legacy.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

More about Anaïs Nin

. . . . . . . . . . . .

However, her oeuvre went far beyond the diary genre that made her famous. She was also one of the first women writers to create literary female erotica, notably, The Delta of Venus and Little Birds. She was a splendid essayist as well, and was a prolific author of fiction, both short stories and novels.

Here are new and recent publications by and about Anaïs Nin. And this is just a partial listing — make sure to see the entire list of books by Anaïs Nin at Swallow Press/Ohio University Press.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Reunited

Reunited: The Correspondence of Anaïs and Joaquín Nin, 1933–1940

By Anaïs Nin and Joaquín Nin

Edited by Paul Herron

Release date: May 2020

In 1913, Joaquín Nin abandoned his family, including his ten-year-old daughter, Anaïs. Twenty years later, Anaïs and Joaquín reunited and began an illicit sexual affair. Long believed to have been destroyed and lost to history, Reunited reveals correspondence between father and daughter, exposing for the first time both sides of their complicated relationship.

Reunited collects the correspondence between Anaïs and Joaquín just before, during, and after the affair, which commenced in 1933, twenty years after he had abandoned his ten-year-old daughter and the rest of his family.

These letters were long believed to have been destroyed and lost to history. In 2006, however, a folder containing Joaquín’s original letters to his daughter was discovered in Anaïs’s Los Angeles home, along with a second folder of her letters to him.

Together, these letters tell the story of an absent father’s attempt to reconnect with his adult daughter and how that rapprochement quickly turned into an illicit sexual relationship.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Trapeze

Trapeze: The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1947–1955

By Anaïs Nin

Edited by Paul Herron

Anaïs Nin made her reputation through publication of her edited diaries and the carefully constructed persona they presented.

It was not until decades later, when the diaries were published in their unexpurgated form, that the world began to learn the full details of Nin’s fascinating life and the emotional and literary high-wire acts she committed both in documenting it and in defying the mores of 1950s America.

Trapeze begins where the previous volume, Mirages, left off: when Nin met Rupert Pole, the young man who became not only her lover but later her husband in a bigamous marriage.

It marks the start of what Nin came to call her “trapeze life,” swinging between her longtime husband, Hugh Guiler, in New York and her lover, Pole, in California, a perilous lifestyle she continued until her death in 1977.

Today what Nin did seems impossible, and what she sought perhaps was impossible: to find harmony and completeness within a split existence. It is a story of daring and genius, love and pain, largely unknown until now.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Mirages

Mirages: The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1939–1947

By Anaïs Nin

Edited by Paul Herron

Mirages opens at the dawn of World War II, when Anaïs Nin fled Paris, where she lived for fifteen years with her husband, banker Hugh Guiler, and ends in 1947 when she meets the man who would be “the One,” the lover who would satisfy her insatiable hunger for connection.

Mirages collects, for the first time, the story that was cut from all of Nin’s other published diaries, particularly volumes 3 and 4 of The Diary of Anaïs Nin, which cover the same time period. It is the long-awaited successor to the previous unexpurgated diaries Henry and June, Incest, Fire, and Nearer the Moon.

Mirages answers the questions Nin readers have been asking for decades: What led to the demise of Nin’s love affair with Henry Miller? Just how troubled was her marriage to Hugh Guiler? What is the story behind Nin’s “children,” the effeminate young men she seemed to collect at will?

Mirages is a deeply personal story of heartbreak, despair, desperation, carnage, and deep mourning, but it is also one of courage, persistence, evolution, and redemption that reaches beyond the personal to the universal.

. . . . . . . . . . .

House of Incest

House of Incest

By Anaïs Nin

With an introduction by Allison Pease, this new edition of House of Incest is a lyrical journey into the subconscious mind of one of the most celebrated feminist writers of the twentieth-century.

Originally published in 1936, House of Incest is Anaïs Nin’s first work of fiction. Based on Nin’s dreams, the novel is a surrealistic look within the narrator’s subconscious as she attempts to distance herself from a series of all-consuming and often taboo desires she cannot bear to let go.

The incest Nin depicts is a metaphor—a selfish love wherein a woman can appreciate only qualities in a lover that are similar to her own. Through a descriptive exploration of romances and attractions between women, between a sister and her beloved brother, and with a Christ-like man, Nin’s narrator discovers what she thinks is truth: that a woman’s most perfect love is of herself.

At first, this self-love seems ideal because it is attainable without fear and risk of heartbreak. But in time, the narrator’s chosen isolation and self-possessed anguish give way to a visceral nightmare from which she is unable to wake.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Collages

Collages

By Anaïs Nin

First published in 1964 and reissued in 2019 with a new introduction by Anita Jarczok, Collages showcases Anaïs Nin’s dreamlike and introspective style and psychological acuity.

Seen by some as linked vignettes and by others as a novel, the book is a mood piece that resists categorization. Based on a close friend of Nin’s, Renate is the glue that holds the pieces, by turn fragmentary and full, together.

One character absorbs a lesson from the Koran: “Nothing is ever finished.” With each of Renate’s successive encounters, we take that message to be true.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Waste of Timelessness

Waste of Timelessness and Other Early Stories

By Anaïs Nin

Written when Anaïs Nin was in her twenties and living in France in the 1920, the stories collected in Waste of Timelessness contain many elements familiar to those who know her later work as well as revelatory, early clues to themes developed in those more mature stories and novels.

Seeded with details remembered from childhood and from life in Paris, the wistful tales portray artists, writers, strangers who meet in the night, and above all, women and their desires.

These experimental and deeply introspective missives lay out a central theme of Nin’s writing: the contrast between the public and private self. The stories are taut with unrealized sexual tension and articulate the ways that language and art can shape reality.

Nin’s deft humor, ironic wit, and ecstatic prose display not only superb craftsmanship but also the author’s own constant balancing act between feeling and rationality, vulnerability and strength.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Winter of Artifice: Three Novelettes

Winter of Artifice: Three Novelettes

By Anaïs Nin

Swallow Press first published Winter of Artifice in 1945, following two vastly different versions from other presses. The book opens with a film star, Stella, studying her own, but alien, image on the screen. It ends in the Manhattan office of a psychoanalyst—the Voice—who, as he counsels patients suffering from the maladies of modern life, reveals himself as equally susceptible to them.

The middle, title story explores one of Nin’s most controversial themes, that of a woman’s sexual relationship with her father. Elliptical, fragmented prose; unconventional structure; surrealistic psychic landscapes—Nin forged these elements into a style that engaged with the artistic concerns of her time but still registers as strikingly contemporary.

This reissue, accompanied by a new introduction by Laura Frost and the original engravings by Nin’s husband Ian Hugo, presents an important opportunity to consider anew the work of an author who laid the groundwork for later writers. Swallow Press’s Winter of Artifice represents a literary artist coming into her own, with the formal experimentation, thematic daring, and psychological intrigue that became her hallmarks.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur

By Anaïs Nin

Seduction of the Minotaur is the fifth and final volume of Anaïs Nin’s continuous novel known as Cities of the Interior. First published by Swallow Press in 1961, the story follows the travels of the protagonist Lillian through the tropics to a Mexican city loosely based on Acapulco, which Nin herself visited in 1947 and described in the fifth volume of her Diary.

As Lillian seeks the warmth and sensuality of this lush and intriguing city, she travels inward as well, learning that to free herself she must free the “monster” that has been confined in a labyrinth of her subconscious.

This new Swallow Press edition includes an introduction by Anita Jarczok, author of Inventing Anaïs Nin: Celebrity Authorship and the Creation of an Icon.

Swallow Press publishes all five volumes that make up Cities of the Interior: Ladders to Fire, Children of the Albatross, The Four-Chambered Heart, A Spy in the House of Love, and Seduction of the Minotaur.

. . . . . . . . . .

Under a Glass Bell

Under a Glass Bell

By Anaïs Nin

Although Under a Glass Bell is now considered one of Anaïs Nin’s finest collections of stories, it was initially deemed unpublishable. Refusing to give up on her vision, in 1944 Nin founded her own press and brought out the first edition, illustrated with striking black-and-white engravings by her husband, Hugh Guiler.

Shortly thereafter, it caught the attention of literary critic Edmund Wilson, who reviewed the collection in the New Yorker. The first printing sold out in three weeks.

This new Swallow Press edition includes an introduction by noted modernist scholar Elizabeth Podnieks, as well as editor Gunther Stuhlmann’s erudite but controversial foreword to the 1995 edition.

Together, they place the collection in its historical context and sort out the individuals and events recorded in the diary that served as its inspiration. The new Swallow Press edition also restores the thirteen stories to the order Nin specified for the first commercial edition in 1948.

The post Books by Anaïs Nin for a New Generation: Recent Publications by Swallow Press appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 17, 2020

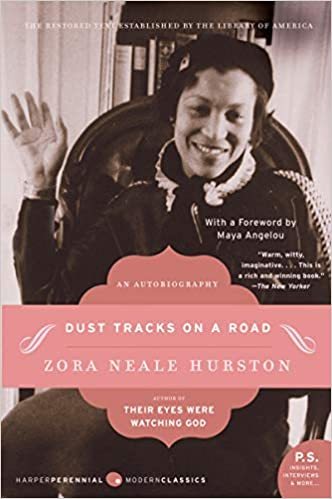

Dust Tracks on a Road by Zora Neale Hurston (1942)

Dust Tracks on a Road, Zora Neale Hurston’s 1942 autobiography, has confounded critics and scholars from the time of its publication, even as it has enthralled and entertained readers.

It was the most commercially successful book she published during her lifetime, though it has since been eclipsed by her 1937 novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Zora (1891 – 1960) studied anthropology at Barnard College in the 1920s, becoming the first African-American student at the prestigious college. With her larger-than-life personality, she quickly became a big name in the Harlem Renaissance movement of the 1920s.

She pursued a career as an ethnographer, collecting stories from the oral traditions of the Black south and the cultures of the Caribbean. At the same time, she wrote fiction, plays, and essays.

Zora’s life was marked by peaks and valleys, accolades and crushing disappointments. Zora stubbornly persisted despite constant financial crises and failed relationships.

When her publisher urged her to write the autobiography that became Dust Tracks, Zora balked. She was only in mid-career, she protested. But she relented because, as always, she needed the funds.

The question has always remained, is Dust Tracks true memoir, or is her life story, as she tells it, more impressionistic rather than realistic? It’s likely a bit of both, something that readers can only guess now.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Zora Neale Hurston

. . . . . . . . . . .

In her Foreword to the 2006 edition, Maya Angelou wrote:

“Zora Neale Hurston chose to write her own version of life in Dust Tracks on a Road. Through her imagery one soon learns that the author was born to roam, to listen, and to tell a variety of stories.

An active curiosity led her throughout the South, where she gathered up the feelings and sayings of her people as a fastidious farmer might gather eggs. When she began to write, she used all the sights she had seen, all the people she encountered and the exploits she had survived …

In this autobiography, Hurston describes herself as obstinate, intelligent, and pugnacious. the story she tells of her life could never have been told believably by a non-Black American, and the details even in her own hands and words offer enough confusions, contusions, and contradictions to confound even the most sympathetic researcher.”

Robert Hemenway, in Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography (1977), sums up the book’s difficulties:

“Dust Tracks can be a discomfiting book, and it has probably harmed Zora’s reputation. Like much of her career, it often appears contradictory. Zora seems to be both an advocate for the universal, demonstrating that this black woman does not look at the world in racial terms, and the celebrant of a unique ethnic upbringing in an all-black village.

Dust Tracks begins with Zora as she grows to adulthood, moving from rustic security toward college and career … She describes herself as a bright, combative, overly imaginative child who had a difficult time between her mother’s death and her college success, but who persevered, and was served well by the values learned in Eatonville.

The final two-fifths of the book self-consciously, and at times simplistically, ranges through love, religion, friendship; it explains why Zora has ‘no race prejudice of any kind.’

When she selects a story from the repertoire of her life and narrates it for her audience, Dust Tracks succeeds. It fails when she tries to shape the narrative into a statement of universality, manipulating events and ideas in order to suggest that the personal voyage of Zora Neale Hurston is something more than the special experience of one black woman.

… That is the chief value of her autobiography — its documentation of the Eatonville scene and what it meant to be a woman who would rise by force of will and talent to become nationally known.”

Mary Helen Washington, in an introduction to one of the book’s later editions, wrote that the book is “filled with evasion, posturing, and all kinds of self-concealment.”

Despite these critical misgivings, Dust Tracks is a wise, warm, and entertaining read by an American writer who was one of a kind. A description from the official Zora Neale Hurston website gives a counterweight argument to the more problematic viewpoints:

“First published in 1942 at the height of her popularity, Dust Tracks on a Road is Zora Neale Hurston’s candid, funny, bold, and poignant autobiography, an imaginative and exuberant account of her rise from childhood poverty in the rural South to a prominent place among the leading artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance.

As compelling as her acclaimed fiction, Hurston’s very personal literary self-portrait offers a revealing, often audacious glimpse into the life—public and private—of an extraordinary artist, anthropologist, chronicler, and champion of the black experience in America.

Full of the wit and wisdom of a proud, spirited woman who started off low and climbed high, Dust Tracks on a Road is a rare treasure from one of literature’s most cherished voices.”

The following brief passages from Dust Tracks on a Road offer a glimpse of its contents.

“Jump at de sun”

“I was born in a Negro town. I do not mean by that the black back-side of an average town. Eatonville, Florida is, and was at the time of my birth, a pure Negro town — charter, mayor, council, town marshal and all. It was not the first Negro community in America, but it was the first to be incorporated, the first attempt at organized self-government on the part of Negroes in America.

… So, looking back, I take it that Papa and Mama, in spite of his meanderings, were really in love. Maybe he was just born before his time. There was nothing then to hinder impulses.

Mama exhorted her children to “jump at de sun.” We might not land on the sun, but at least we would get off the ground. Papa did not feel so hopeful. Let well enough alone. It did not do for Negroes to have too much spirit. He was always threatening to break mine or kill me in the attempt. My mother was always standing between us.”

“One of the most serious objections to me was that having nothing, I still did not know how to be humble. A child in my place ought to realize I was lucky to have a roof over my head and anything to eat at all.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

What White Publishers Won’t Print

. . . . . . . . . . .

Books and Things

While I was in the research field in 1929, the idea of Jonah’s Gourd Vine came to me. I had written a few short stories, but the idea of attempting a book seems so big, that I gazed at it in the quiet of the night, but hid it away from even myself in daylight.

For one thing, it seemed off-key. What I wanted to tell was a story about a man, and from what I had read and heard, Negroes were supposed to write about the Race Problem. I was and am thoroughly sick of the subject.

My interest lies in what makes a man or a woman do such and so, regardless of his color. It seemed to me the human beings I met reacted pretty much the same to the same stimuli. Different idioms, yes.

Circumstances and conditions having power to influence, yes. Inherent difference, no. But I said to myself that that was not what was expected of me, so I was afraid to tell a story the way I wanted or rather the way the story told itself to me. So I went down that way for three years.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Their Eyes Were Watching God

. . . . . . . . . . .

Their Eyes Were Watching God

I wrote Their Eyes Were Watching God in Haiti. It was dammed up in me, I wrote it under internal pressure in seven weeks. I wish that I could write it again. In fact, I regret all of my books. It is one of the tragedies of life that one cannot have all the wisdom one is ever to possess in the beginning.

Perhaps, it is just as well to be rash and foolish for a while. If writers were too wise, perhaps no books would get written at all. It might be better to ask yourself “Why?” afterwards than before.

Anyway, the force from somewhere in Space which commands you to write in the first place, gives you no choice. You take up the pen when you are told, and write what is commanded. There is no agony like a bearing and untold story inside you.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Dust Tracks on a Road on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Looking Things Over

I can look back and see sharp shadows, high lights, and smudgy inbetweens. I have been in Sorrow’s kitchen and licked out all the pots. Then I have stood on the peaky mountain wrapped in rainbows, with the heart and a sword in my hands.

What I have to swallow in the kitchen has not made me less glad to have lived, nor made me want to low-rate the human race, nor any whole sections of it. I take no refuge from myself in bitterness …

If tough breaks have not soured me, neither have my glory-moments caused me to build any altars to myself where I can burn incense before God’s best job of work. My sense of humor will always stand in the way of my seeing myself, my family, my race, or my nation as the whole intent of the universe.

I see too, it while we all talk about justice more than any other quality on earth, there is no such thing as justice in the absolute in the world. We are too human to conceive of it. We all want the breaks, and what seems just to us is something that favors our wishes.

More about Dust Tracks on a Road by Zora Neale Hurston

Most recent edition:

The Restored Text Established by the Library of America with a Foreword by Maya Angelou

Series editor: Henry Louis Gates, Jr. | HarperPerennial Modern Classics

HarperCollins publishers © 1942, 1995 Copyright renewed 1970, John Hurston

Previously unpublished passages © 1995 by the Estate of Zora Neale Hurston

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Video review by Climb the Stacks

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Dust Tracks on a Road by Zora Neale Hurston (1942) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 15, 2020

The Stunt Girls — 3 Fearless American Pioneers of Investigative Journalism

When you think of undercover reporting, what comes to mind? I have to admit that the image that came to my mind was some guy in a trench coat, wearing a fedora. That is, until I learned about the group of late nineteenth and early twentieth century reporters referred to as “stunt girls.”

These intrepid young women, following in the footsteps of Nelly Bly, pioneered the practice of underground investigative reporting in journalism.

Good journalism has always been about presenting the human story behind events large and small. It’s also about holding the powerful accountable for their actions, a cornerstone of democracy (at least in theory). Women have always had the desire, talent, and ability to participate in these endeavors.

Yet every step of the way, from early American newspapers to broadcast news, women have had to fight for the right to report. But no matter what barriers stood in their way, women have found a way around them or blasted through them.

These three trailblazers did just that, paving the way for women to cover hard news and social issues a matter of course — though that fight would still be waged for decades to come.

. . . . . . . . . .

Eva McDonald Valesh posed as a worker to expose unsafe working conditions in factories

. . . . . . . . . .

The birth of the “stunt girl” reporter

In 1887, a small-town girl from Pennsylvania arrived in New York City with the burning ambition of becoming a star reporter. Elizabeth Cochrane changed her name to Nellie Bly and would become the first “stunt girl” reporter, inspiring other young women of her time to go undercover.

Using secret identities like “Dorothy Dare” and “Florence Noble,” this breed of female reporters tackled subjects considered “unfit for ladies.” Newspaper readers devoured their exposés on the plights of factory workers (including children), the mentally ill, disaster victims, and immigrants.

From the late 1880s through the early 1900s, daily newspapers were cropping up in every American city, large and small. As the printing process continued to grow cheaper, competition for readers grew more fierce. More women were literate, and newspapers were hungry to grab their attention.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Yellow Journalism and “Ten Days in a Madhouse”

Two of the top newspapermen of the time, William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, constantly competed to outdo each other for the most sensational human interest news stories. This kind of “yellow journalism” was packed with drama and printed under blaring headlines.

After Nellie Bly’s explosive 1887 “Ten Days in a Madhouse” series appeared in Pulitzer’s New York World, every major newspaper wanted a stunt girl on staff. Following in the footsteps of Nellie Bly, young women reporters risked life and limb for the juiciest scoops. The shocking stories they wrote captured readers’ imaginations — and sold a ton of newspapers!

Though this overly dramatic stunt reporting was eventually looked down upon, these young reporters truly pioneered the more respected kind of investigative journalism. Their writing style might have been over the top, but the scandals and injustices they revealed were real. In many cases, their reporting led to lasting change supported by Congress and the courts.

. . . . . . . . . .

Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

Nellie Bly was the nom de plume that Elizabeth Cochrane took when she arrived in New York City at age twenty-two. She’d already investigated Pittsburgh’s factories, and what she’d seen had made her mad. It confirmed her belief that reporting was a good way to expose the truth.

As a newly hired reporter for the New York World, she was pushed into society and theater pages. But that wasn’t what she’d come to New York to write about.

In 1887, Nellie convinced her editor to let her investigate the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island. She pretended to be insane so she’d be committed as a patient. Her series on the brutal conditions she saw and experienced herself is still considered a groundbreaking work of investigative journalism.

Nellie Bly’s travel adventures inspired a board game

Two years later, Nellie got Joseph Pulitzer to fund a trip around the world. She would follow the footsteps of the fictional Phileas Fogg, hero of Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules Verne. She beat the record, traveling nearly 25,000 miles in seventy-two days.

This stunt didn’t change anyone’s life for the better, but her exciting travelogues made her world-famous. Nellie now had more power to do the kind of reporting she felt was important.

And that’s exactly what she did. Nellie wrote about immigrants, women’s prisons, labor issues, abandoned children, sexual harassment, and more. Was she ahead of her time? Possibly. But there were already many young women who wanted to dive into investigative reporting; she was brave enough to light the way.

More about Nellie Bly on this site:

In Search of Nellie Bly: America’s Pioneering Investigative Journalist

Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Journalist

. . . . . . . . . .

Winifred Sweet Bonfils Black (1863 – 1926)

Winifred Sweet Bonfils Black was the original “sob sister” — a name for female reporters who wrote human interest stories with enough drama and emotion to make readers weep.

Another pioneer of undercover journalism, Winifred was just a year younger than Nellie Bly, and was inspired by her daring spirit and sense of adventure.

For her undercover work, Winifred used the byline “Annie Laurie” but also wrote under her real name. She especially liked covering murder trials and interviewing famous people. Once, after being denied an interview with President Benjamin Harrison, she hid under his railroad dining car and cornered him when he sat down to dinner.

One of her famous stunts involved throwing herself under a truck in San Francisco and pretending to faint. Instead of her trademark elegant dresses, she wore shabby clothes. Taken to a nearby hospital, she was assumed to be poor and took secret notes on how she was treated — or rather, mistreated. When her series was published, the entire hospital staff was fired.

Winifred also went undercover to report on natural disasters, including the Galveston flood of 1900. Women reporters weren’t allowed, so she disguised herself as a boy. She exposed conditions in juvenile courts, cotton mills, canneries, and more.

Her articles resulted in improved conditions for workers as well as better emergency and disaster relief. By the time of her death, Winifred Sweet Bonfils Black was a respected journalist — no longer dismissed as a “stunt girl” or “sob sister.”

More about Winifred Sweet Bonfils Black, including links to some of her articles.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Eva McDonald Valesh (1866 – 1956)

Eva McDonald Valesh came to her interest in journalism early. Growing up in Minnesota, she worked as a typesetter in a print shop, which was unusual for a young woman. She also joined a typographer’s union — even more unusual.

As a young reporter for the twin cities’ Globe, she posed as a worker at a local garment factory. Under the name “Eva Gay,” she wrote articles on female workers’ long hours, low wages, and the unhealthy conditions in the factory. Her reports inspired a successful strike for better pay and working conditions.

When Eva’s exposés started to gain attention, employers in the Minnesota area became wary, not wanting to be fooled by her. But even with her unique tomboy looks and ragged costumes, she never failed to slip under the radar and get her stories.

Through her investigations as a stunt girl reporter, Eva created lasting improvements for factory, domestic, and service workers. When that phase of her career was over, she got involved in the Minnesota labor movement and led the campaign for an 8-hour workday — something we now take for granted.

The only time Eva ever slowed down was when she nearly died giving birth to her only child. For the rest of her long life, she proudly supported labor causes as a passionate speaker and writer.

More about Eva McDonald Valesh.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about “stunt girl” reporters

5 Stunt Girl Reporters that Changed Investigative Journalism

These Women Reporters Went Undercover to Get the Most Important Scoops of Their Day

Nellie Bly and Stunt Journalism: Undercover Exploration to Discover the Truth

And though this is by no means an exhaustive list, here are more investigative journalists who were considered “stunt girls” of their time:

Elizabeth Banks (“Mary Mortimer Maxwell”)

Nixola Greeley-Smith

Ada Patterson

Helen Cusack (“Nell Nelson”)

Nora Marks

Winifred Mulcahey

Elizabeth Jordan

“Florence Noble”

“Dorothy Dare”

Eleanor Stackhouse

You might also enjoy:

10 Pioneering African-American Women Journalists

6 Women Journalists of the World War II Era

3 Trailblazing Sports Journalists

The post The Stunt Girls — 3 Fearless American Pioneers of Investigative Journalism appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 13, 2020

The Message of the City: Dawn Powell’s New York Novels 1925 – 1962

Dawn Powell (1896 – 1965) is considered a “writer’s writer,” though nearly all of her work was out of print by the time she died. Overcoming a hard-knock early life in the American midwest, she moved to New York City in 1918 and fell in love with it. Dawn Powell’s New York novels and stories are among the most enduring of her works.

Though she wrote prolifically throughout her life, producing novels, short stories, poetry, and plays, she didn’t gain much notoriety — for better or worse — during her lifetime. To the joy of devoted fans and new readers alike, many of her works have been rediscovered and rereleased.

A critical biography of Dawn Powell’s New York novels

In The Message of the City: Dawn Powell’s New York Novels 1925 – 1962 (2016), a critical biography and study of Powell’s work, Patricia Palermo gives the underappreciated author her due, and a place in American letters. From the publisher, Ohio University Press (A Swallow Press book):

Dawn Powell was a gifted satirist who moved in the same circles as Dorothy Parker, Ernest Hemingway, renowned editor Maxwell Perkins, and other midcentury New York luminaries.

Her many novels are typically divided into two groups: those dealing with her native Ohio and those set in New York.

“From the moment she left behind her harsh upbringing in Mount Gilead, Ohio, and arrived in Manhattan, in 1918, she dove into city life with an outlander’s anthropological zeal,” reads a New Yorker piece about Powell, and it is those New York novels that built her reputation for scouring wit and social observation.

In this critical biography and study of the New York novels, Patricia Palermo reminds us how Powell earned a place in the national literary establishment and East Coast social scene.

Though Powell’s prolific output has been out of print for most of the past few decades, a revival has been under way: the Library of America, touting her as a “rediscovered American comic genius,” released her collected novels, and in 2015 she was posthumously inducted into the New York State Writer’s Hall of Fame.

Engaging and erudite, The Message of the City fills a major gap in in the story of a long-overlooked literary great. Palermo places Powell in cultural and historical context and, drawing on her diaries, reveals the real-life inspirations for some of her most delicious satire.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Dawn Powell

. . . . . . . . . . .

From the introduction to The Message of the City

Ohio-born writer Dawn Powell, who lived from 18961 to 1965, was always prolific, writing fifteen novels; more than a hundred short stories; a dozen or so plays; countless book reviews; several radio, television, and film scripts; volumes of letters and diary entries; even poetry.

So productive was she that, following one spate of housecleaning, she wrote to her editor at Scribner’s, Max Perkins, “I was appalled by the mountains of writing I had piled up in closets and file cases and trunks … It struck me with terrific force that I just wrote too goddam much. Worse, I couldn’t seem to stop”

Weighing her literary output against that of some of her contemporaries, Powell joked to her close friend, writer and literary critic Edmund Wilson, “If I don’t write for five years I may make quite a name for myself and if I can stop for ten I may give Katherine Anne [Porter] and Dorothy Parker a run for their money.”

If in her lifetime, Powell never did make either the name for herself or the money she had hoped, she did enjoy certain successes. In the year before her death, she was awarded the American Institute of Arts and Letters’ Marjorie Peabody Waite Award for lifetime achievement; a few years before that, she was granted an honorary doctorate from her alma mater, Lake Erie College for Women.

… After she moved from Ohio to Manhattan in 1918 and began writing the many works that today are divided into the Ohio and the New York novels (with the exceptions of Angels on Toast, sometimes called a Chicago novel, and A Cage for Lovers, set in Paris), Malcolm Cowley hailed her as “the cleverest and wittiest writer in New York”; Diana Trilling called her “one of the wittiest women around.”

Other friends and admirers included Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, Matthew Josephson, Edmund Wilson, and many more. Some of her books sold adequately, many less than adequately; none were blockbusters by any means, and virtually all were out of print by the time of her death in 1965.

Thanks to the late Gore Vidal and Tim Page — her biographer, the Pulitzer prize–winning former Washington Post music critic and professor in both the Annenberg School of Journalism and the Thornton School of Music at the University of Southern California—twelve of her novels, a volume of her letters, a collection of her diaries, and some of her plays and short stories have in recent decades been reissued to critical acclaim.

Several of her plays have been either restaged or produced for the first time, and a 1933 film, Hello Sister, loosely based on Powell’s play Walking Down Broadway, was in the 1990s released on VHS, if only out of interest in its famous director, Erich von Stroheim; it was shown in a Greenwich Village cinema in 2012.

Of course, more important than quantity of writing is quality. Powell’s novels are filled with astute observations, wry commentaries, spot-on characterizations. Despite her reputation as a tough and unflinching satirist, she is capable of moving tenderness and pathos, particularly in the Ohio novels.

In an article originally published in the New York Times Book Review, Terry Teachout called My Home Is Far Away, one of the Ohio novels, a “permanent masterpiece of childhood.” Few novelists are better at depicting young children than is Powell; one need read but the first several chapters of My Home Is Far Away to see that. Edmund Wilson found her books “at once sympathetic and cynical.”

… But most remarkable perhaps is her sense of humor. Few writers are wittier, more scathing, more insightful than Powell. Not only Gore Vidal, Terry Teachout, and Diana Trilling, but Margo Jefferson, John Updike, Michael Feingold, and many other distinguished authors and critics have found much to like in the novelist.

About the author

Patricia E. Palermo is a Southern California native, professor of English, and independent scholar who has lived in the New York City area for more than twenty years.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Message of the City on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Praise for Message of the City

“Palermo understands Powell’s mixture of wit and pain, knows the books by heart, has the scholarship down pat, and has written it up in an intelligent and lyrical manner. A smart, affectionate, and never blinkered study of one of America’s great authors.” — Tim Page, author of Dawn Powell: A Biography

“The Message of the City is a solid, thoughtful piece of work. Palermo’s familiarity with Dawn Powell’s own writings and with the secondary literature on her life is comprehensive, and she’s integrated her analyses of fact and fiction with exceptional skill. Anyone who reads the book will come away with a clear understanding of why Powell’s New York novels are of continuing interest, both as works of satire and as sharp-eyed fictionalized portraits of her life and times.” — Terry Teachout, drama critic, Wall Street Journal

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Message of the City: Dawn Powell’s New York Novels 1925 – 1962 appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 11, 2020

Eleanor H. Porter

Eleanor H. Porter (December 19, 1868 – May 21, 1920) was best known as the author of Pollyanna, the children’s novel that took America by storm during the World War I years.

Most people today won’t know the name of the author of this classic, but many still understand what it means to be called a “Pollyanna.” According to Merriam Webster’s Dictionary, it’s “a person characterized by irrepressible optimism and a tendency to find good in everything.”

Pollyanna was published in 1913, on the eve of World War I — it would hardly seem the time for the story of a girl who could see the bright side of just about any situation, no matter how dire. But somehow the book struck a nerve and was an immediate hit with children as well as adults, and its popularity endured throughout those years.

Much of the following biography comes directly from her obituary in Cambridge Chronicle, May, 29, 1920.

Early years and education

Eleanor Hodgman was born in Littleton, New Hampshire, and was the only child of Francis Fletcher Hodgman, a pharmacist and Llewella (Woolson) Hodgman. She was of Mayflower ancestry and traced her lineage directly back to Governor Bradford.

When she was a very small child, Eleanor began to play and sing. Even before she learned to read notes she would make up little pieces to express her moods. Naturally, it was decided in her family that she was “musical,” and all her education was planned to cultivate that talent.

She had also, however, a taste for writing, and birthdays, weddings and other important occasions among her acquaintances were always celebrated with a little poem from Eleanor.

In school, on exhibition days, her part was singing, playing or acting, though all the while she was longing to be asked to write. During Eleanor’s high school days, ill health interrupted her studies and for a time all books were banished.

When she became well again, she came to Boston, where she studied music under private teachers and at the New England conservatory. She sang in concerts and in church choirs for some years.

The start of a writing career

After her marriage on May 3, 1892, at Springfield, Vt., to John Lyman Porter, of Corinth, Vt., they took up their residence for a few years at Chattanooga, Tenn., where Mr. Porter then was in business.

It was around 1900 that Eleanor began to turn her attention seriously to writing. Her first novel, Cross Currents, was published in 1907. Subsequent books included The Turn of the Tide, The Story of Marco, Miss Billy, and Miss Billy’s Decision. The latter two, published in 1911 and 1912, fared very well and set the stage for what was to become her most popular work.

. . . . . . . . . .

Pollyanna: Revisiting the Eternal Optimist

. . . . . . . . . .

Pollyanna

Pollyanna, subtitled The Glad Book, became her best-known work. Following its publication as a full novel in1913 (it was first serialized in newspapers), it didn’t take long for the book to sell its first million copies.

Pollyanna is an 11-year-old orphan who comes to live under the care of her dour spinster aunt Polly in a Vermont town. Soon, her “glad game” — finding the good in any situation— wins over the residents of the town and transforms it into a place of hope and joy.

Pollyanna’s success was followed by Miss Billy Married (rounding out a series of three) and Pollyanna Grows Up. Later works included Just David and Dawn. All of her books of this era were enormous bestsellers.

Later works

Following the success of these books, Eleanor went in a somewhat different direction with her work. The Road to Understanding, to a certain extent like Dawn, dealt mainly with older characters, as did her short stories, published in three volumes, each with a certain unity of subject: The Tie That Binds, Tales of Love and Marriage, The Tangled Threads, Just Tales, and Across the Years Tales of Age.

In Mary Marie, she went back to the scene of her greatest popular successes, once again creating a lovable child character. At the time of her death, Eleanor had been working on a story which had been contracted for by a Boston monthly magazine.

She also had recently finished a book entitled Sister Sue, which a New York magazine had contracted for, to be issued serially in the fall.

The last fifteen years of Eleanor Hodgman Porter’s life were spent in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She was only 51 when she died of tuberculosis on May 21, 1920.

She was survived by her husband, with whom she had no offspring, though she demonstrated a great affinity for children in her literary work.

At her funeral service, the reverend noted in his eulogy that she was “mourned as a beautiful woman who had won her way into the hearts of everyone who had read her stories; that her books had blessed thousands of lives of old and young. She was loved for her winsome gladness; her buoyant and joyous nature was reflected in her characters.”

. . . . . . . . .

Eleanor H. Porter page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Stage and film adaptations

Pollyanna was first adapted to the Broadway stage in 1916, with Helen Hayes in the title role. It received great accolades and went on the road to be performed in Philadelphia and other locations. It debuted as a silent film in 1920 starring Mary Pickford, the actress then known as “America’s sweetheart,” also to resounding success.

The 1960 Disney adaptation is the best known. Hayley Mills won a special Oscar for her portrayal of Pollyanna. The film departs in some significant ways from the book; still, it was a major success. These are just a few of its film and stage adaptations.

Eleanor H. Porter’s Legacy

Pollyanna came just about in the middle of Eleanor’s prolific writing career. In her time, she became quite well known. Throughout her writing career, she also wrote numerous short stories.

As a work of literature, Pollyanna is sentimental, corny, and somewhat simplistic. It doesn’t have the grace, humor, and subtle subversiveness of L.M. Montgomery’s classic Anne of Green Gables, a book that also deals with an unwanted 11-year-old orphan girl, published just five years earlier.

In turn, Anne of Green Gables debuted five years after Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm by Kate Douglas Wiggin (1903). Pollyanna has endured as part of this trio of early twentieth-century books about irrepressible orphan girls who melt the hearts of dour aunts and flinty spinsters.

Despite the book’s incredible success and staying power, Eleanor was often roundly criticized for unleashing this cheerful-to-a-fault heroine. In an interview, she explained:

“You know I have been made to suffer from the Pollyanna books. I have been placed often in a false light. People have thought that Pollyanna chirped that she was ‘glad’ at everything. I have never believed that we ought to deny discomfort and pain and evil; I have merely thought that it is far better to ‘greet the unknown with a cheer.’”

Pollyanna, though in the public domain, continues to stay in print, has gone through countless editions, and has been translated to numerous languages.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Eleanor H. Porter

On this site

Optimistic Quotes from Pollyanna

Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter: Revisiting the Eternal Optimist

Short Stories

In addition to some fifteen published novels, Eleanor H. Porter wrote numerous short stories, perhaps some 200, for various publications, too many to list here. The following are a few of the collections:

Across the Years (1919)

Money, Love, and Kate (1923; posthumous)

Little Pardner (1926)

Just Mother (1927)

Novels

Cross Currents (1907)

The Turn of the Tide (1908)

The Story of Marco (1911)

Miss Billy (1911)

Miss Billy’s Decision (1912)

Pollyanna (1913)

The Sunbridge Girls at Six Star Ranch (1913)

Miss Billy Married (1914)

Pollyanna Grows Up (1915)

Just David (1916)

The Road to Understanding (1917)

Oh, Money! Money! (1918)

The Tangled Threads (1919)

Dawn (1919)

Keith’s Dark Tower (1919)

Mary Marie (1920)

Sister Sue (1921; posthumous)

More information and sources

Wikipedia

Reader discussion of Porter’s works on Goodreads

Encyclopedia

Read and listen online

Porter’s works on Project Gutenberg

Porter’s works on Librivox

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Eleanor H. Porter appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 7, 2020

There is Confusion by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1924)

There is Confusion by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882 – 1961) was the first novel by this American editor, poet, essayist, educator, and author associated closely with the Harlem Renaissance movement.

In addition to her own pursuits, Cornell-educated Fauset was known as one of the “literary midwives” of the movement, as someone who encouraged and supported other talents.

Fauset’s poetic bent is reflected in the novel’s title, which comes from lines in “The Lotos-Eaters” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

There is confusion worse than death,

Trouble on trouble, pain on pain,

Long labour unto aged breath …

Ann Allen Shockley, in Afro-American Women Writers 1746 – 1933, observed that the writing of this book “at the age of forty-two was prompted by reading an unrealistic novel, Birthright (1922) by white writer T.S. Stribling. To her, the story was not indicative of actual Negro life. There is Confusion was the first novel to depict black middle-class people.”

A new edition in 2020

After being out of print for many years, Modern Library Torchbearers has reissued There is Confusion in a new edition with an introduction by bestselling author Morgan Jerkins. Here is the publisher’s synopsis of the book:

“A rediscovered classic about how racism and sexism tests the spirit, ambition, and character of three children growing up in Hell’s Kitchen and Harlem, from Jessie Redmon Fauset, the literary editor of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP.

Set in early-twentieth-century New York City, There Is Confusion tells the story of three Black children: Joanna Marshall, a talented dancer willing to sacrifice everything for success; Maggie Ellersley, an extraordinarily beautiful girl determined to leave her working-class background behind; and Peter Bye, a clever would-be surgeon who is driven by his love for Joanna.

As children, Maggie, Joanna, and Peter support one another’s dreams, but as young adults, romance threatens to upset the balance of their friendship. One afternoon, Joanna makes two irrevocable decisions — and sets off a chain of events that wreaks havoc with all of their lives.

Written with a Jane Austen-like eye for social dynamics, There Is Confusion is an unjustly forgotten classic that celebrates Black ambition, love, and the struggle for equality.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Jessie Redmon Fauset

. . . . . . . . . . .

Initial critical response

Reviews in white newspapers made an enormous to-do about the fact that There is Confusion featured middle-class black people doing ordinary things, and grappling with the universal quandaries and challenges of life and love.

Though no reviewers objected to this portrayal, they nevertheless marveled at it — at the time, it was quite revolutionary to depict black people in a way that didn’t involve demeaning stereotypes.

A review in an Illinois newspaper pointed out that that the book featured no Southern mammy saying “sho’ ‘nuff,” no happy-go-lucky plantation Negro (if ever there were such thing). Others pointed out that there was no slapstick comedy or tragic roles.

In some of the reviews, it was pointed out the achievement of this book is all the more significant due to having been written by an educated “negress.” Rather, observed this review, the book presented “a picture of a new society which is rapidly growing up among the educated Negro of the north.”

A review in the May 31, 1924 Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that the book’s characters “do not carry on a continuous burlesque … They are encouraged and thwarted in their endeavors precisely as the blondest Nordics are encouraged or thwarted. In short, they live in a perfectly natural fashion …The result is an unprejudiced study of modern negro psychology written with profound knowledge and understanding.”

Fauset was celebrated with receptions and book launch parties by her black colleagues when There is Confusion was published, but they held her to a high standard and not all were enamored of this and her subsequent work. Her novels occasionally received mixed reviews from African-American critics. Some praised her for portraying an aspect of black life that often didn’t see the light of print; others criticized her for an overly bourgeoise point of view.

Yet the majority of black critics were delighted with Fauset’s images of black American life. Critic and anthropologist William Stanley Braithwaite praised her as “the potential Jane Austen of Negro literature.”

. . . . . . . . .

See also: Plum Bun by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1928)

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1924 review of There is Confusion

This original review in The Chicago Tribune, July 26, 1924 is typical of the mixture of admiration and amazement the novel received upon first publication. Please note that some of the language here reflects the parlance of the time:

There is Confusion, a novel by Jessie Redmon Fauset, is of more than the usual interest a first novel inspires in a reader. Miss Fauset is a Negro and the story is a serious record of the lives of a group of the educated, ambitious members of her race.

As a first novel it is as good as the average. The construction is not as good as it could be, the motivations seem a little strained, and the heroine’s rise to fame, like that of most fictional heroines, is more flighty than convincing.

But the faults of There is Confusion are no greater than the faults of most first novels, and Miss Fauset tells an interesting story.

That her characters are always shadowed by the fact of their color is the most memorable impression one gains from the book — that, and the fact that they have a rounded, full life of their own. That life, aside from the mechanical devices of restaurants where they may not eat, parallels the life of white family that occupy similar social positions of their own.

There is none of the poignant terror and power that one finds in W.E.B. Du Bois’s Dark Water, for instance, or in The Souls of Black Folk.

There is bitterness in the story, but not despair. Its hero discovers that, instead of being the direct descendant of a pure stock of slaves (and therefore the cream of Negro society), as he believed himself to be, he is the grandson of a white man. That provides an explanation, to him, of why he as suffered shiftlessness of mind and inability to amount to something due to that taint of white blood.

“My ingratitude, my inability to adopt responsibility, my very irresoluteness came from that strain of white Bye blood. But I understand it now. I can fight against it …”

If you expect to find any of the rich color and flavor of Negro humor in There is Confusion, you will be entirely disappointed, for there isn’t a moment of it. The story might as well have been of middle class Lithuanians or Bosnians, or French, or English, or Americans, so far as any actual local flavor is concerned.

The characters talk like their white neighbors; act, in most cases, like them; love and live like them. There is Confusion comes nowhere near to being the Great Negro Novel. It’s merely a presentable novel written by an educated and obviously earnest person of that race. It’s as good as the general run of first novels, and, one account of its story, illuminating and interesting.

. . . . . . . . . .

There is Confusion by Jessie Redmon Fauset on Amazon*

or purchase from an independent bookstore*

. . . . . . . . . .

How There is Confusion begins: A portion of Chapter One

Joanna’s first consciousness of the close understanding which existed between herself and her father dated back to a time when she was very young. Her mother, her brothers and her sister had gone to church, and Joanna, suffering from some slight childish complaint, had been left home. She had climbed upon her father’s knee demanding a story.

“What sort of story?” Joel Marshall asked, willing and anxious to please her, for she was his favorite child.

“Story ’bout somebody great, Daddy. Great like I’m going to be when I get to be a big girl.”

He stared at her amazed and adoring. She was like a little, living echo out of his own forgotten past. Joel Marshall, born a slave and the son of a slave in Richmond, Virginia, had felt as a little boy that same impulse to greatness.

“As a little tyke,” his mother used to tell her friends, “he was always pesterin’ me: ‘Mammy, I’ll be a great man some day, won’t I? Mammy, you’re gonna help me to be great?’

“But that was a long time ago, just a year or so after the war,” said Mammy, rocking complacently in her comfortable chair. “How wuz I to know he’d be a great caterer, feedin’ bank presidents and everything? Once you know they had him fix a banquet fur President Grant. Sent all the way to Richmond fur ’im. That’s howcome he settled yere in New York; yassuh, my son is sure a great man.”

But alas for poor Joel! His idea of greatness and his Mammy’s were totally at variance. The kind of greatness he had envisaged had been that which gets one before the public eye, which makes one a leader of causes, a “man among men.”

He loved such phrases! At night the little boy in the tiny half-story room in that tiny house in Virginia picked out the stories of Napoleon, Lincoln and Garrison, all white men, it is true; but Lincoln had been poor and Napoleon unknown and yet they had risen to the highest possible state. At least he could rise to comparative fame.

And when he was older and came to know of Frederick Douglass and Toussaint L’Ouverture, he knew if he could but burst his bonds he, too, could write his name in glory.

This was no selfish wish. If he wanted to be great he also wanted to do honestly and faithfully the things that bring greatness. He was to that end dependable and thorough in all that he did, but even as a boy he used to feel a sick despair—he had so much against him.

His color, his poverty, meant nothing to his ardent heart; those were nature’s limitations, placed deliberately about one, he could see dimly, to try one’s strength on. But that he should have a father broken and sickened by slavery who lingered on and on! That after that father’s death the little house should burn down!

He was fifteen when that happened and he and his mother both went to work in the service of Harvey Carter, a wealthy Virginian, whose wife entertained on a large scale. It was here that Joel learned from an expert chef how to cook.

His wages were small even for those days, but still he contrived to save, for he had set his heart on attending a theological seminary. Some day he would be a minister, a man with a great name and a healing tongue. These were the dreams he dreamed as he basted Mrs. Carter’s chickens or methodically mixed salad dressing.

His mother knew his ideas and loved them with such a fine, albeit somewhat uncomprehending passion and belief, that in grateful return he made her the one other consideration of his life, weaving unconsciously about himself a web of such loyalty and regard for her that he could not have broken through it if he would.

Her very sympathy defeated his purpose. So that when she, too, fell ill on a day with what seemed for years an incurable affection, Joel shut his teeth and put his frustrated plans behind him.

He drew his small savings from the bank and rented a tiny two and a half room shack in the front room of which he opened a restaurant,—really a little lunch stand. He was patronized at first only,—and that sparingly—by his own people.

But gradually the fame of his wonderful sandwiches, his inimitable pastries, his pancakes, brought him first more black customers, then white ones, then outside orders. In five years’ time Joel’s catering became known state wide. He conquered poverty and came to know the meaning of comfort. The Grant incident created a reputation for him in New York and he was shrewd enough to take advantage of it and move there.

Ten years too late old Mrs. Marshall was pronounced cured by the doctors. She never understood what her defection had cost her son. His material success, his position in the church, in the community at large and in the colored business world,—all these things meant “power.” To her, her son was already great. Joel did not undertake to explain to her that his lack of education would be a bar forever between him and the kind of greatness for which his heart had yearned.

It was after he moved to New York and after the death of his mother that Joel married. His wife had been a school teacher, and her precision of language and exactitude in small matters made Joel think again of the education and subsequent greatness which were to have been his. His wife was kind and sweet, but fundamentally unambitious, and for a time the pleasure of having a home and in contrasting these days of ease with the hardships of youth made Joel somewhat resigned to his fate.

“Besides, it’s too late now,” he used to tell himself. “What could I be?” So he contented himself with putting by his money, and attending church, where he was a steward and really the unacknowledged head.

His first child brought back the old keen longing. It was a boy and Joel, bending over the small, warm, brown bundle, felt a gleam of hope. He would name it Joel and would instill, or more likely, stimulate the ambition which he felt must be already in that tiny brain. But his wife wouldn’t hear of the name Joel.

“It’s hard enough for him to be colored,” she said jealously guarding her young, “and to call him a stiff old-fashioned name like that would finish his bad luck. I am going to name him Alexander.”

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

**This is a Bookshop.org link. Literary Ladies receives a modest commission from sales, and your purchase helps support independent bookstores.

The post There is Confusion by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1924) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 2, 2020

Celebrating the Centenary of The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie

2020 marks one hundred years since Christie’s debut novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, was first published. As the inaugural Hercule Poirot mystery, the story was serialized in The Times (London) weekly edition from February to June 1920 and later published as a complete novel in the U.S. in October, 1920.

The book was written as the result of a challenge between Agatha and her older sister, who bet that Agatha couldn’t write a detective novel. While she was working in a dispensary during World War I, Agatha came up with the idea for the story using her knowledge of poisons.

And the rest is literary history, as Agatha conquered the publishing world for more than fifty years, releasing works that defined the genre, including And Then There Were None, the world’s best-selling crime novel.

Agatha Christie is the best-selling novelist in history. With over one billion books sold in English and another billion in over 100 languages, her popularity has never waned; last year her English language sales exceeded two million copies. For more on the centenary of her first publication, see 100 Years of Agatha Christie stories.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Agatha Christie

. . . . . . . . . . .

About The Mysterious Affairs at Styles

Who poisoned the wealthy Emily Inglethorp and how did the murderer penetrate and escape from her locked bedroom? Suspects abound in the quaint village of Styles St. Mary—from the heiress’s fawning new husband to her two stepsons, her volatile housekeeper, and a pretty nurse who works in a hospital dispensary.

With impeccable timing, and making his unforgettable debut, the brilliant Belgian detective Hercule Poirot is on the case.

One of the best-loved classic mysteries of all time, The Mysterious Affair at Styles will continue to enchant old readers and introduce Agatha Christie’s unique storytelling genius to a host of new readers.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Mysterious Affair at Styles (centenary edition) on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

To mark the occasion, HarperCollins issued a new edition of The Mysterious Affair at Styles in Jan. 2020. In this official and fully restored edition, Hercule Poirot solves his first case in the Agatha Christie novel that started it all, now featuring a “missing chapter” and exclusive content from the Queen of Mystery.

The exclusive content featured in this Agatha Christie reissue will include a passage from The Mysterious Affair at Styles; “Creating Poirot,” a letter from Agatha Christie published in 1958; “Agatha Christie’s Favourite Cases,” an article written by Agatha Christie to introduce serialization of her novel Appointment with Death in the Daily Mail in 1938; “A Letter to My Publisher,” by Agatha Christie from the American Omnibus Hercule Poirot Master Detective, (HarperCollins, 2016).

In addition, every reissue will include The Hercule Poirot Reading List and The Miss Marple Reading List, which includes the Top Ten Titles, a Reader’s Guide, and a Reader’s Challenge.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

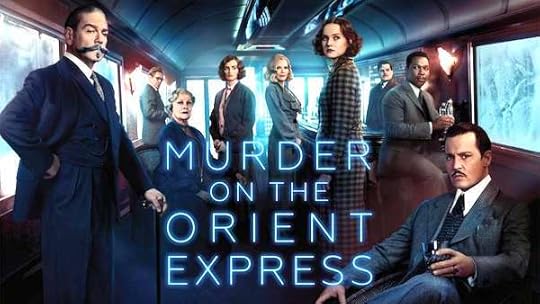

Blockbuster stage and screen adaptations

Christie’s stories have always translated brilliantly to screen and stage, with 48 million people having watched 20th Century Fox’s 2017 movie blockbuster Murder on the Orient Express in cinemas, taking in $350 million at the global box office.

She is also the most successful female playwright of all time: The Mousetrap is the longest running West-End show in history, watched by 10 million people in its continuous London run since 1952, and a quarter of a million people have seen Witness for the Prosecution at London’s County Hall since it opened in 2017.

In 2019 there were over 700 productions of Agatha Christie’s plays globally, with performances from an estimated 7000 individuals. Major productions of her works, including a new adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express, are playing to audiences worldwide.

The centenary year will see celebrations across the book world and beyond, culminating in the release of 20th Century Studios’ highly anticipated film adaptation of Death on the Nile directed by and starring Kenneth Branagh as Poirot.

James Prichard, chairman of Agatha Christie Limited and Christie’s great-grandson said: “100 years after her first story was published, the extraordinary global appeal of my great grandmother’s stories shows no sign of abating. Her works continue to entertain audiences through the books, television, film and theatre – a testament to their timelessness, and to her unique creativity.”

Liate Stehlik, President and Publisher of the William Morrow Group says: “Agatha Christie was a literary genius. Her stories are always riveting, thanks to her instinctive sense of what makes people tick and her determination to surprise and delight her readers. And she made it look effortless. The Mysterious Affair at Styles is just as relevant now as it was 100 years ago. Christie’s timeless stories continue to resonate with millions of new readers even today.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Agatha Christie

. . . . . . . . . .

New research on Christie readership

New research has revealed that an estimated 32 million Americans have read an Agatha Christie book, and in 2019 alone over 900,000 people bought an Agatha Christie book in the U.S.! Additionally, Agatha Christie is the introduction to mysteries for 3 out of every 10 readers in the nation.

The research was commissioned by HarperCollins to mark the centenary of Christie’s being in print (with the aforementioned publication of The Mysterious Affair at Styles, 1920) and was conducted by an independent research agency. It included 4,500 nationally representative fiction readers in the U.K. U.S. and Australia.

Surprising Facts and Figures About Agatha Christie

Agatha Christie’s personal life was just as interesting as her professional work. During World War I, she worked firstly as a VAD nurse, and then as a qualified dispenser in the pharmacy at Torquay’s wartime hospital, where she acquired her knowledge of poisons.

It was during this time that she devised the plot for her first detective story — a result of a bet from her elder sister Madge, who said she could never do it — and where she created Hercule Poirot, inspired by the Belgian refugees in her home town.

In 1922, she spent 10 months traveling the world with her first husband Archie, on a research mission for the British Empire exhibition. During this Grand Tour, she learnt to surf in South Africa and Hawaii, and is credited with being the first Western woman to stand up on a surfboard.

She was also an amateur archaeologist. Over two decades, she attended digs in the Middle East and North Africa with her second husband Max Mallowan, living on the excavation sites where aside from writing her novels, she photographed the artifacts and cleaned them using her own face cream.

Here are more fascinating facts and statistics about Agatha Christie:

Over 2 billion books published, with as many published in foreign languages as in English.

Outsold only by the Bible and Shakespeare.

Her books continue to sell 4,000,000 copies every year.

A writing career spanning six decades, with 66 crime novels, 6 non-crime novels and over 150 short stories.

The most successful female playwright of all time, holding a world record as the only female playwright to have three plays running simultaneously in London’s West End.

Wrote around 25 plays, of which the most famous, The Mousetrap, is the longest running play in the world, having debuted in 1952.

Since first publication, her books have been published in over 100 languages, making her the most translated writer of all time. Currently she is published in 57 languages and in over 100 countries.

Her best-known works includes Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, and the genre-defining And Then There Were None.

Created Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, two of the most famous detectives of all time.

Received a DBE (Dame of the British Empire) in 1971.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Death on the Nile — a new film adaptation coming in the fall of 2020

October 2020 will see the release of the 20th Century Studios feature film adaptation of Agatha Christie’s acclaimed mystery Death on the Nile.

The film is directed by five-time Academy Award nominee Kenneth Branagh, who also stars as Poirot. Branagh helms an all-star cast that includes Tom Bateman, Annette Bening, Russell Brand, Ali Fazal, Dawn French, Gal Gadot, Armie Hammer, Rose Leslie, Emma Mackey, Sophie Okonedo, Jennifer Saunders and Letitia Wright.

It follows the box office hit Murder on the Orient Express, released in November 2017, which grossed over $35 million in the global box office.

Agatha Christie Limited (ACL) has been managing the literary and media rights to Agatha Christie’s works around the world since 1955. Collaborating with the very best talents in film, television, publishing, stage and on digital platforms ACL ensures that Christie’s work continues to reach new audiences in innovative ways and to the highest standard. The company is managed by Christie’s great grandson James Prichard.

Contributed by HarperCollins: HarperCollins Publishers is the second largest consumer book publisher in the world, with operations in 17 countries.

With 200 years of history and more than 120 branded imprints around the world, HarperCollins publishes approximately 10,000 new books every year in 16 languages, and has a print and digital catalog of more than 200,000 titles.

Writing across dozens of genres, HarperCollins authors include winners of the Nobel Prize, the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the Newbery and Caldecott Medals and the Man Booker Prize.

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Celebrating the Centenary of The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

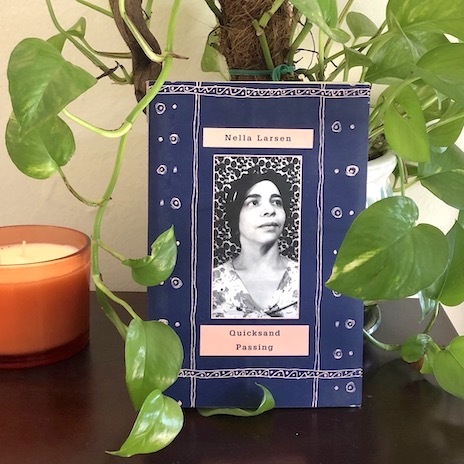

Passing by Nella Larsen (1929)

Passing by Nella Larsen (1929) is one of the most iconic novels of the Harlem Renaissance era of the 1920s, the New York City-centered movement that celebrated the ascendence of black writers, artists, and performers.

Nella Larsen was the first African-American woman to graduate from library school and to receive the Guggenheim Fellowship for creative writing. As the daughter of a white Danish immigrant mother and a mixed-race father from the Danish West Indies, the theme of her life, and in effect, her work, was a sense of never belonging — not to any community, nor even to an immediate family.

Though her first novel, Quicksand (1928), contained more obviously autobiographical elements, Passing also reflected the author’s lifelong sense of alienation and search for identity.

In length, Passing might be considered a novella, yet within its spare prose lies deep ideas and much to ponder. The 2001 Griot Edition describes it succinctly:

“In Passing, Clare Kendry, a poor, fair-skinned woman, passes for white and marries a wealthy white man. Seeking to fulfill a need for the company of black folks, she renews a friendship with Irene Redfield, who has married a physician and becomes a member of Harlem’s black elite.

As Clare spends more time in Harlem, her search for community becomes dangerous in the face of her blatantly racist husband who believes he has never even met a black person. Clare yearns for a closeness with Irene that she cannot name but which reads as incredibly homoerotic.

‘Passing’ is not only a direct reference to Clare’s decision to live as a white woman but also her suppression of her sexuality. It also calls attention to the other kinds of ‘passing’ women do in relationships romantic and otherwise, and the adoption by the black middle class of the actions and values of the dominant culture.”

Highly recommended is a critical essay by Claudia Tate titled “Nella Larsen’s Passing: A Problem of Interpretation.” It begins:

“Nella Larsen’s Passing (1929) has been frequently described as a novel depicting the tragic plight of the mulatto. In fact, the passage on the cover of the 1971 Collier edition refers to the work as ‘the tragic story of a beautiful light-skinned mulatto passing for white in high society.’

It further states that Passing is a “searing novel of racial conflict …” Though Passing does indeed relate the tragic fate of a [mixed-race] woman who passes for white, it also centers on jealousy, psychological ambiguity, and intrigue.

By focusing on the latter elements, Passing is transformed from an anachronistic, melodramatic novel into a skillfully executed and enduring work of art.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Nella Larsen

. . . . . . . . . .

Passing as an exploration of cultural identity

The following insights are excerpted from the Introduction by Thadious M. Davis to the 1992 Penguin Books edition of Passing:

“In Passing (1929), Nella Larsen explores the cultural identity and psychological positioning of modern black individuals unmarked by difference from whites.

Locating her narrative within the liberating 1920s, the golden days of black cultural consciousness, she critiques a societal insistence on race as essential and fixed by representing racial fluidity inherent in Clare Kendry Bellew and Irene Westover Redfield, women who choose their racial identities.

In portraying Clare, who becomes white, and Irene, who passes occasionally, Larsen represents passing as a practical, emancipatory option, a means by which people of African descent could permeate what W.E.B. Du Bois themed ‘the veil of color caste.’

Larsen defines passing in a meeting between Clare and Irene as a simple but ‘hazardous business,’ requiring ‘breaking away from all that was familiar and friendly to take one’s chance in another environment, not entirely strange, perhaps, but certainly not entirely friendly.’

Basing her definition on readable social texts, she concludes that by changing their environment or social structures, passers disrupt social meanings and avail themselves of both basic human and fundamental constitutional rights enjoyed by the white majority.

With such certain rewards for so easy a move, Clare ‘wondered why more coloured girls … never ‘passed’ over. It’s such a frightfully easy thing to do. If one’s the type, all that’s needed is a little nerve.’

Passing, according to Clare, is a movement in gesture as well as in space: a psychological, social, cultural movement signaling both a reconfiguration of the self and consolidation of one’s cultural identity, but not a valuation of one’s physical body.

… In creating characters like Irene, her physician husband, and their designer-dressed, college-educated friends, Larsen reduced the material difference in lifestyle between blacks and whites of the middle class and freed her narrative of the more obvious markers of racial identity.”

. . . . . . . . .

Quicksand & Passing by Nella Larsen on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Marriage in Harlem: A 1929 Review of Passing

From the original review of Passing in the Baltimore Evening Sun, June 15, 1929: Just as in the author’s first novel, Quicksand, you are made vividly aware of the intellectual Negro temperament, of the barriers existing between blacks and whites and of the utter inability of either side to remove them.

Harlem has its Negro city with walls as definite as the walls of Troy. Although they allow whites to bring in an occasional friendly wooden horse, to listen to their songs or discuss art with their intelligentsia, they nonetheless have rationalized for themselves an impenetrable defense against hostile attitudes. All of this is forcibly brought out in Miss Larsen’s novel.