Nava Atlas's Blog, page 55

May 14, 2020

A Chronology of the Brief Life of Emily Brontë

Who was Emily Brontë? This is a question not easily answered. This wonderful chronology of her brief life by W. Robertson Nicoll was part of the introduction to the 1908 edition of The Complete Poems of Emily Brontë provides much insight into how she lived and worked.

Emily Brontë (1818 – 1848), the British author known for the novel Wuthering Heights, was also recognized as a brilliant poet. The sister of Charlotte and Anne Brontë, she is arguably the most enigmatic of the trio who produced some of the most widely read classics in English literature.

Emily only lived to age thirty and led a sheltered life at Haworth Parsonage in Yorkshire, rarely encountering anyone outside her immediate family. Yet she Emily one of the most iconic novels of passion and tragedy. Wuthering Heights is rather dark study of desire and obsession, it also touches upon economic, social, and psychological issues and is often cited as the ideal “romantic novel.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Anne, Emily, and Charlotte as depicted by their brother, Branwell

. . . . . . . . . . .

A woman of genius: A Chronology of Emily Brontë’s Life

We now see the extraordinary conditions under which this woman of genius did her work. Outside her own circle she had not a single friend. She never had a lover or any one who came near to be her lover.

She was never outside of Yorkshire save during the Brussels experience, where she paid so dearly for the education which she hoped to turn into money. She had practically no acquaintances.

The only people in Haworth she talked to were the servants and the visitors forced upon the home by the brother. Yet she loved life and shrank from death. Between her sister Anne and herself there was a tie of peculiar tenderness and closeness.

She was passionately loved by Charlotte, who saw, nevertheless, something harsh in her temperament. There is no reason to suppose that she failed in affection to her father and her aunt, or to Branwell, though he may have wearied her out.

She did the work of a servant in the house apparently with the greatest cheerfulness and efficiency. In the exercise of her imagination and in her love of nature she found peace. She refused to complain, and turned a front now calm, now defiant, to the most threatening circumstances.

So very little is known of Emily Brontë, the greatest woman genius of the nineteenth century, that whatever throws light upon her thoughts is of high interest to her lovers. It is only for these that this book has been compiled and printed.

How small our knowledge of Emily Brontë’s life is may be best shown by a brief chronological account of her thirty years:

1818.—Emily Brontë born at Thornton.

1820.—Anne Brontë born at Thornton.

1820.—The family remove to Haworth.

1821 (September).—The mother, Mrs. Brontë, died.

1824.—The little Brontë girls went to school at Cowan’s Bridge. Emily, the prettiest of the sisters, was ‘a darling child, under five years of age, quite the pet nursling of the school.’ As a matter of fact, Emily was in her seventh year.

1826.—The children established their plays, each choosing representatives. Emily chose Sir Walter Scott, Mr. Lockhart, and Johnny Lockhart. Blackwood’s Magazine was the favourite reading of the children, and they had also Southey and Sir Walter Scott left by their Cornish mother, and ‘some mad Methodist magazines full of miracles and apparitions, and preternatural warnings.’

1831.—Charlotte Brontë went to school at Roe Head.

1832.—Charlotte returned to Haworth in order to teach Emily and Anne what she had learned. After lessons they walked on the moors. At home Emily was a quiet girl of fourteen, helping in the housework and learning her lessons regularly.

On the moors she was gay, frolicsome, almost wild. She would set the others laughing with her quaint sallies and genial ways. She is described as ‘a strange figure—tall, slim, angular, with a quantity of dark brown hair, deep, beautiful hazel eyes that could flash with passion, features somewhat strong and stern, the mouth prominent and resolute.’

1833.—Ellen Nussey, Charlotte Brontë’s friend, came to Haworth, and made acquaintance with Emily, then about fifteen. Miss Nussey describes her as not ugly, but with irregular features, and a pallid thick complexion, and ‘kind, kindling, liquid eyes.’

She had no grace or style in dress. She was a great walker, and very fond of animals. Only one dog was allowed to her, though two seemed to have got into the house. Emily was very happy on the moor and talked freely.

1835.—Emily, when close on seventeen, went to school at Roe Head with Charlotte. The change from her own home to a school, and from her secluded but free and simple life to discipline and companionship, she found intolerable. She became miserably ill, threatening consumption, and had to go home. This restored her health almost immediately.

In this year she found her brother Branwell beginning to go wrong, drinking in the public house and doing no work.

1836 (Midsummer).—Miss Nussey and Charlotte went to Haworth, and the girls had a taste of happiness and enjoyment.

They were beginning to feel conscious of their powers, they were rich in each other’s companionship; their health was good, their spirits were high, there was often joyousness and mirth; they commented on what they read; analysed articles and their writers also; the perfection of unrestrained talk and intelligence brightened the close of the days which were passing all too swiftly. Charlotte and Emily would dance in exuberant spirits.

1836 (September).—Emily went into a situation as teacher in Miss Patchet’s school at Law Hill, near Halifax, where there were some forty girls. She worked from six in the morning till eleven at night, with only half an hour of exercise between, and soon broke down. At Christmas she came home to Haworth for a brief rest, and then returned to Halifax.

1837 (Spring).—Emily’s health broke down, and she came back to Haworth.

1837–38.—Emily alone at Haworth. Anne, Charlotte, and, for a time, Branwell were away.

1837 (Christmas) found Charlotte, Emily, and Anne at Haworth nursing their old servant, Tabby, who had fallen on the slippery street and broken her leg.

1839.—Charlotte writes: ‘I manage the ironing and keep the rooms clean; Emily does the baking and attends to the kitchen.’

1840.—Emily, Branwell, and Charlotte were all at home together. Charlotte and Branwell had sent their writings to authors, Southey, Coleridge, and Wordsworth, but Emily had not. Her manuscripts were in her locked desk. Emily, Anne, and Charlotte were hoping to enlarge the parsonage at Haworth and keep school.

Things were going fairly well, and Emily was, on the whole, happy. I have been told by Miss Nussey that the one man outside her home in whom Emily ever showed any interest was Mr. Brontë’s first curate, the Rev. William Weightman.

There was nothing like a love affair between them, but she was gracious to him and enjoyed his jests as they all walked together on the moors. But it is on record that Emily was trying to prevent the curate from pressing his attentions on Miss Nussey.

It would seem that in no man’s eyes was Emily passing fair. Emily’s countenance, said Miss Nussey, ‘glimmered,’ as it always did when she enjoyed herself.

1841.—In the early months she was as happy as other country girls in a congenial home. Later on Miss Wooler offered Charlotte the good-will of her school at Dewsbury Moor, but though the girls wished to accept, no arrangement was carried through.

In September Charlotte proposes to go with Emily to Brussels, in order that they might learn French and German, and fit themselves for keeping a school. She calculated that the journey would cost only five pounds for each, and that the living would be half as dear as in England.

‘I feel an absolute conviction that if this advantage could be allowed to us, it would be the making of us for life.’ Arrangements were made to decline the school at Dewsbury Moor. Bridlington was thought of. Emily assented, being anxious that the school should be started.

1842.—Charlotte and Emily went to Brussels to the School of the Hégers. Héger thought that Emily knew no French at all. She was oddly dressed, and wore amazing leg-of-mutton sleeves, her pet whim in and out of fashion. She had a bitter sense of exile, but Charlotte enjoyed the change.

Emily did not like Héger, and was as indomitable and fierce as Charlotte was gentle and obedient. But Héger thought Emily had more genius than her sister. He was deeply impressed with her faculty of imagination and her argumentative powers, and said: ‘She should have been a man: a great navigator!’

But the two were never friends. Emily was ‘wild for home,’ and seldom spoke a word to any one. It was probably at this time that she composed the poem ‘at twilight in the schoolroom,’—’The house is old, the trees are bare.’

In the meantime, Charlotte was almost dangerously happy, but knew that Emily and her teacher did not draw well together. Emily, however, was working very hard, especially at German and music. She became an excellent musician, and her piano playing is described as singularly accurate and expressive.

The two studied French under Héger, whose method was to take an author and investigate his technique. Emily complained against this method, and said that it destroyed all originality of thought and expression. But in spite of this she wrote better exercises than Charlotte did.

All the while she was in revolt. She made no intimate companions, and suffered much, disliking intensely what she though the ‘gentle Jesuitry of the foreign and Romish system.’ Only her desire to be independent kept her in Brussels.

1842.—Madame Héger proposed that Charlotte should teach English, and that Emily should teach music to the younger pupils, so that they might stay on without paying for half a year. They were too poor to go home for their holidays in August and September, and remained in Brussels. But they were called back in the end of October by the death of their aunt.

1842 (Christmas).—They were invited by Héger to go back to Brussels. Emily would not consent. Branwell was at home, but the sisters had not seen him at his worst, and they were happy for three months.

1843 (January).—Charlotte went back to Brussels. Emily was left behind with Branwell for a short time. Branwell went away as tutor, and Emily was left alone with her father and old Tabby helping in the housework. She had Flossie, Anne’s favourite spaniel, and Keeper, the fierce bulldog, cats, and other animals. Charlotte was not happy at Brussels. Branwell was still drinking, and Anne was very anxious about him. Mr Brontë, the father, was in failing health and tempted by stimulants. In the end of this year Emily wrote to Charlotte urging her return.

1844 (January).—Charlotte arrived at Haworth very reluctantly. ‘Haworth seems such a lonely quiet spot.’

1844 (March).—Emily and Charlotte were together thinking over the future. Charlotte wrote: ‘Our poor little cat has been ill two days, and is just dead. It is piteous to see even an animal lying lifeless. Emily is sorry.’

The girls wrote for pupils, but failed to get them. Branwell got worse and worse, drinking heavily to excess. Emily had no friends. They gave up the idea of having pupils.

1844 (July).—Charlotte visited Miss Nussey. When she came back she found Branwell dismissed by his employer. Charlotte, writing of her sister Emily, afterwards said: ‘She had in the course of her life been called upon to contemplate near the end and for a long time the terrible effects of talents misused and faculties abused; hers was naturally a sensitive, reserved, and dejected nature; what she saw went very deeply into her mind: it did her harm.’

Madame Duclaux (Miss A. Mary F. Robinson) in her truly sympathetic book on Emily Brontë, argues that Emily never wearied in her kindness for her unhappy brother, and always hoped to win him back by love when the other sisters had despaired. In March 1846, Charlotte Brontë wrote to Ellen:

“I went into the room where Branwell was to speak to him, about an hour after I got home; it was very forced work to address him. I might have spared myself the trouble, as he took no notice and made no reply; he was stupefied.

My fears were not in vain. I hear that he got a sovereign while I have been away, under pretence of paying a pressing debt; he went immediately and changed it at a public house, and has employed it as was to be expected. Emily concluded her account by saying that he was a hopeless being. It is too true. In his present state it is scarcely possible to stay in the room where he is.”

Madame Duclaux has also a very graphic account of a fire in which a drunken Branwell must have been burned to death had it not been that Emily entered the blazing room, and half carried in her arms, half dragged out, her besotted brother.

This is no doubt part of the extremely questionable Brontë tradition. The legend is almost certainly based on a similar episode in Jane Eyre. Mr Swinburne had a special delight in the belief that Emily was kinder than her sisters, but, as Mr. Shorter has shown, there is no clear evidence for the fact. It is quite plain that she did less in the way of remonstrance than the others.

1845.—In autumn Charlotte accidentally lighted on a manuscript volume of verses in her sister’s handwriting. She saw the value of the poems, and caught their new note. It was resolved that the sisters should publish a little volume together.

1846 (May).—Poems of the sisters Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell were published by Messrs. Aylott and Jones. The book cost the authors thirty guineas, and two copies supplied the public demand.

1846.—The three sisters were each busy on a novel, Emily was writing Wuthering Heights, Charlotte The Professor, and Anne Agnes Grey. It was a heavy and dreary time. Branwell became more and more the oppression of the family.

Out of very scanty means they had to pay his debts. The father was growing blind with cataract, and was deeply depressed, but the indomitable sisters completed their work, and Charlotte began Jane Eyre.

1846 (August).—Charlotte Brontë went to Manchester with her father, and Mr. Brontë went through an operation for cataract, which was successful. In the end of the year Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey were accepted by Newby, a third-rate publisher of the time, who issued many worthless novels on commission.

1847.—The Professor was declined, but Jane Eyre was accepted and published by Smith and Elder.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

. . . . . . . . . . .

1847 (14th December).—Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey were published by Newby, who was encouraged by the success of Jane Eyre. Charlotte Brontë writes:

“Wuthering Heights is, I suppose, at length published, at least Mr. Newby has sent the authors their six copies. I wonder how it will be received. I should say it merits the epithets of vigorous and original much more decidedly than Jane Eyre did. Agnes Grey should please such critics as Mr. Lewes, for it is true and “unexaggerated” enough. The books are not well got up; they abound in errors of the press.”

1848 (September).—Patrick Branwell Brontë died. Charlotte Brontë wrote: ‘I myself, with painful, mournful joy, heard him praying softly in his dying moments; and to the last prayer which my father offered up at his bedside, he added, “Amen.” How unusual that word appeared from his lips, of course you, who did not know him, cannot conceive.’ He was in the village just before his death. “The removal of our only brother must necessarily be regarded by us rather in the light of a mercy than as a chastisement.”

1848 (29th October).—Charlotte Brontë writes:

“Emily’s cold and cough are very obstinate. I fear she has a pain in the chest, and I sometimes catch a shortness in her breathing, when she has moved at all quickly. She looks very, very thin and pale. Her reserved nature occasions me great uneasiness of mind. It is useless to question her; you get no answers. It is still more useless to recommend remedies; they are never adopted.”

On 2nd November she writes again:

“My sister Emily has something like a slow inflammation of the lungs. . . . She is a real stoic in illness: she neither seeks nor will accept sympathy. . . . When she is ill there seems to be no sunshine in the world for me. The tie of sister is near and dear indeed, and I think a certain harshness in her powerful and peculiar character only makes me cling to her more.”

1848 (22nd November).—We have a glimpse of Emily in her last days. Charlotte Brontë writes to W. S. Williams:

“The North American Review is worth reading. There is no mincing the matter there. What a bad set the Bells must be! What appalling books they write! To-day, as Emily appeared a little easier, I thought the Review would amuse her, so I read it aloud to her and Anne.

As I sat between them at our quiet but now melancholy fireside, I studied the two ferocious authors. Ellis, the ‘man of uncommon talents, but dogged, brutal, and morose,’ sat leaning back in his easy chair, drawing his impeded breath as he best could, and looking, alas! piteously pale and wasted; it is not his wont to laugh, but he smiled, half amused and half in scorn as he listened.

Acton was sewing, no emotion ever stirs him to loquacity, so he only smiled too, dropping at the same time a single word of calm amazement to hear his character so darkly portrayed. I wonder what the reviewer would have thought of his own sagacity could he have beheld the pair as I did.” …

1848 (19th December).—Emily Brontë died, ‘conscious, panting, reluctant.’

(As thorough as this chronology of Emily Brontë is, it gives very short shrift to her demise. Here’s more about The Death of Emily Brontë.)

More about Emily Brontë

No Coward Soul is Mine: 5 Poems by Emily Brontë

Emily Brontë’s Poetry: A 19th-Century Analysis

The Night of Storms Has Passed: A Ghostly Poem by Emily Brontë

Keeper: Emily Brontë’s Fiercely Devoted Dog

10 Interesting Facts About the Brontë Sisters

The post A Chronology of the Brief Life of Emily Brontë appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 9, 2020

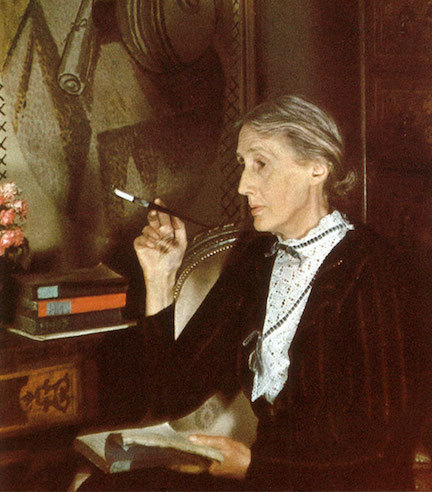

Beyond the Legend: Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West’s Love Affair & Friendship

The relationship of Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West has gone down in literary history, and even today it holds a fascination, epitomizing the allure of the unconventional, the bohemian, the slightly eccentric and exotic.

On December 15, 1922, Virginia Woolf recorded in her diary that she had met “the lovely aristocratic Sackville-West last night at Clive’s. Not much to my severer taste … all the supple ease of the aristocracy, but not the wit of the artist.”

She was, of course, writing of Vita, the woman who would go on to become her lover, friend, and confidante.

Their affair has inspired biographies, a West End play, and most recently, a 2019 film (the reception of the latter having been tepid). But none have come close to capturing the vibrant nuances and dynamics of their personalities, or the subtleties of a relationship that was more emotional than physical and that lasted until Virginia’s death in 1941.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf

. . . . . . . . . . .

A discouraging start

By the time she met Virginia, Vita was thirty years old and an established author, having published several volumes of poetry and fiction with more commercial than literary success.

Virginia was ten years older, and had published three novels and survived three major bouts of insanity. The age difference and the apparent emotional fragility did not deter Vita, however, whose first impressions were far more favorable than Virginia’s. Soon after their first meeting, she wrote to her husband Harold Nicholson:

“I simply adore Virginia Woolf, and so would you … Mrs Woolf is so simple…At first you think she is plain, then a sort of spiritual beauty imposes itself on you, and you find a fascination in watching her…I’ve rarely taken such a fancy to anyone”.

In true Vita style — slightly arrogant, slightly pushy, but with a charm and vitality that few could resist — she persuaded Virginia into several dinners (although not into membership of the P.E.N.Club, an international author’s society of which Vita was a member).

A flurried exchange of letters and books followed … and then nothing. Perhaps Vita was snubbed at Virginia’s refusal to join the P.E.N. Club, or more likely she was preoccupied with her new affair with architectural historian Geoffrey Scott.

Virginia, meanwhile, was working on both Mrs. Dalloway and The Common Reader. It wasn’t until late spring 1924 that correspondence between the two resumed and an intimacy, of sorts, was formed.

. . . . . . . . . .

Portrait of a Marriage: Vita Sackville-West & Harold Nicolson

. . . . . . . . . . .

Seduction in Bloomsbury

Despite her initial dismissal of Vita’s artistic merits, Virginia enjoyed both Vita’s poetry and fiction. In May 1924 she threw down a gauntlet: would Vita write a novel for the Hogarth Press (the small press she ran with her husband Leonard Woolf), and would she write it while on holiday in Italy that summer?

Vita responded by writing from Italy that she hoped “no one has ever yet, or ever will, throw down a glove I was not ready to pick up.” The result was Seducers In Ecuador, which she dedicated to Virginia.

Over the next few months, they settled into a tentative sparring back and forth, in language that became more and more flirtatious and intimate. Their letters show that a dichotomy of sorts was developing: Virginia saw Vita as the superior woman, while Vita saw Virginia as the superior writer.

Virginia’s response to Vita’s advances was a mix of guarded acquiescence and gentle mockery, and already Vita was playing not only the larger-than-life aristocrat (the “superior woman” that Virginia so admired) but also the protective maternal figure to Virginia’s sometimes helpless child.

Virginia, in turn, could also be Vita’s mistress of letters, appearing unattainable, unpredictable, and unapproachable; all aspects of her character that gave her a mysterious allure and simply added to Vita’s fascination.

But she was also affectionate and — perhaps more importantly — willing to indulge Vita’s aggressive side. When Vita accused her of using other people “for copy,” not thinking that Virginia would take offense, Virginia responded,

“I enjoyed your intimate letter…It gave me a great deal of pain – which is I’ve no doubt the first stage of intimacy…Never mind: I enjoyed your abuse very much.”

“I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia …”

In September 1925, Harold Nicholson was informed by the Foreign Office that he would be posted to the British Legation in Tehran, and it was arranged that Vita would join him in January and remain until May.

The news startled Virginia into realizing how much Vita had come to mean to her. Vita was “doomed to go to Persia; & I minded the thought so much (thinking to lose sight of her for 5 years) that I conclude I am genuinely fond of her…”

With the prospect of months of separation, Virginia visited Vita’s home at Long Barn in Kent that December. She stayed for three nights, and Vita made a note in her diary for the 17th: “A peaceful evening.”

For the 18th, though: “Talked to her til 3 am — Not a peaceful evening.” It’s generally agreed that it was during this time at Long Barn the two became lovers.

After this progression of their relationship, separation was all the more difficult. Vita was honest with Harold who, after suffering through the chaos of Vita’s affair with Violet Trefusis just a few years earlier, was understandably worried.

Vita sought to reassure him, saying that she would not fall in love with Virginia, nor would Virginia fall in love with her. Despite this, on the journey to Tehran Vita penned some of the most poignant love letters in literary history.

From Italy, she wrote “I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia,” and from the Red Sea, “I find it very difficult to look at the coast of Sinai when I am also looking inward and finding the image of Virginia everywhere.”

But Vita never entirely lost herself: in amongst the letters are the traveller’s insights and the adventurer’s spirit that would eventually find expression in A Passenger to Teheran, also published by the Hogarth Press.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Signs of affection: “Potto” and “Donkey West”

When Vita returned from Tehran their relationship continued, but rarely in a sexual way. Vita was a passionate woman who often sought affairs outside of her marriage, but she had “too much real affection and respect” for Virginia to toy with her.

Mindful of the episodes of madness which had already left Virginia fragile, she initiated few sexual encounters. The love she felt for Virginia, she said, was not a sexual thing but “a mental thing; a spiritual thing, if you like, an intellectual thing, and she inspires and feeling of tenderness…”

Their letters during this time show a deepening of emotional intimacy along with a sense of fun, sometimes beginning in the traditional way of “Dearest Vita” or “My dearest Virginia”, but sometimes addressed to “Potto” (Virginia) and “Donkey West” (Vita).

They became close enough for uncomfortable observations to also occasionally be made. Virginia once wrote to Vita that, “there is something obscure…something that doesn’t vibrate in you…something reserved, muted … It’s in your writing too, by the bye. The thing I call central transparency — sometimes fails you there too.”

Vita knew Virginia was right, writing to Harold, “Damn the woman, she has put her finger on it … the thing which spoils me as a writer; destroys me as a poet.”

But emotional intimacy wasn’t enough. Vita was a fierce woman, with a longing for adventure that no amount of traveling to and from Tehran could satisfy. This time, the adventure presented itself in the form of Mary Campbell, wife of the poet Roy Campbell, and by October 1927 they were lovers.

Vita’s love letters to Virginia continued as if nothing was wrong, however Virginia sensed immediately that Vita’s attention had wandered.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Orlando by Virginia Woolf: Gender and Sexuality Through Time

. . . . . . . . . . .

The longest love letter in literature

The unexpected result of Vita’s lapses in fidelity, drawn out over a period of several months, was one of the most personal “biographies” in literary history: the fictional account of Vita’s life that was Orlando.

On October 9, Virginia wrote to Vita that she was aware of Mary Campbell, and also to tell her about the idea for Orlando:

“Suppose Orlando turned out to be Vita; and it’s all about you and the lusts of your flesh and the lure of your mind (heart you have none, who go gallivanting down the lanes with Campbell)…Shall you mind? Say yes, or No.”

Vita readily agreed. as the writing flowed, Orlando became a version of Vita that, while completely recognizable to anyone who knew her, was also purely Virginia’s; a creation that could not be taken from her, who was safe beyond the lure of other women.

It also posed some interesting questions for Virginia as she withdrew, busy writing the fictional Orlando / Vita into existence while the real Vita was continuing to see Mary Campbell. She often wondered in her diary which was the more real.

In September 1928 the two women took a long-awaited holiday to France — the first and only holiday they would take together. Both were nervous about the prospect of close day-to-day proximity, but the week was a success. Further successes followed on their return with the publication of Orlando.

Reviewers loved it and Vita, who had not so far been allowed to read a word, found herself “enchanted, under a spell.”

Even Harold Nicholson praised it, writing to Virginia from Berlin, “It really is Vita — her puzzled concentration, her absent-minded tenderness … She strides magnificent and clumsy through 350 years.”

Their son Nigel would later refer to the book as “the longest and most charming love letter in literature.” Only Vita’s mother disliked it, writing to Virginia, “… probably you do not realise how cruel you have been.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Sissinghurst Gardens

. . . . . . . . . . .

Sissinghurst

With Orlando, though, Vita felt as if Virginia truly had “found her out.” All aspects of her character, including those she usually kept hidden even from herself, had been laid bare. She felt as if there was nothing that could now be kept from Virginia.

As an artist and fellow writer, her admiration for Virginia increased, while emotionally she began to withdraw. Virginia once again sensed what was happening but knew that there was nothing she could do about Vita’s affairs.

Further change was precipitated by the resounding successes of Vita’s novels The Edwardians, published by the Hogarth Press in 1930, and All Passion Spent, published in 1931.

With the money that she earned Vita was able to purchase Sissinghurst Castle in Kent, the renovation of which would become her life’s project and the garden of which would make her more famous than her novels.

It also took her one step further away from Virginia, who split her time — along with Leonard — between London and Monk’s House in Sussex.

Although they saw each other from time to time and continued to exchange letters, the restoration of Sissinghurst took most of Vita’s attention while Virginia was enjoying a new friendship with the composer Ethel Smyth.

Her feelings for Vita remained unabated, but even she couldn’t close her eyes to the changes that were happening as Sissinghurst became the centre of Vita’s world.

The onset of war

With the approach of the Second World War, Virginia was becoming tense and fragile. Her nephew Julian Bell had been killed in the Spanish Civil War, and she had just finished her longest and most arduous (to write) novel, The Years.

It was against this background of bloody exhaustion that she wrote Three Guineas, a passionate denunciation of wars and the patriarchy which perpetuated them.

It was published in 1938 and caused one of the only serious quarrels she ever had with Vita, who alleged that the book contained “misleading arguments” that amounted to dishonesty.

Several stinging letters flew back and forth between London and Sissinghurst before Virginia was satisfied that Vita had not been accusing her of deliberate deceitfulness.

Behind all of this was the shadow of war, and their responses to it could not have been more different. Vita’s intrinsic aggressiveness was sparked to life — she came down from her pink Kentish tower, rolled up her sleeves and volunteered as a local ambulance driver.

Virginia, however, was horrified. War, to her, meant loss and deprivation. It meant no readers, and without readers there were no writers and no creativity. War also meant the end of personal independence as books struggled to sell and the Hogarth Press struggled to publish.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I might have saved her”

The women kept in touch through the first years of the war. Virginia occasionally visited Sissinghurst, when petrol rations and air raids allowed, and Vita kept the Woolfs supplied with butter and eggs.

But by 1941 Virginia had begun to drift into a strange state of serenity that quickly turned into the deepest of depressions. The strain of war, the fear of old age and of another period of insanity, and the terror of failing as a writer all converged to produce, for her, the perfect storm.

On March 28, 1941 Virginia ended her own life by drowning herself in the River Ouse.

Vita had had no idea of Virginia’s state of mind, and the shock would haunt her for years. Later, she wrote to Harold, “I still think that I might have saved her if only I had been there and had known the state of mind she was getting into.”

She could well have been right, but we will never know. It was the sad end of a long and passionate friendship that was far more vibrant in life than portrayed on screen, and one that will surely continue to fascinate for years to come.

Sources

All letter and diary quotes are taken from The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf, edited by Louise DeSalvo and Mitchell Leaska, Cleis Press 1984, and from Vita: The Life of Vita Sackville-West by Victoria Glendinning, Penguin 1983.

Further reading

The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf, edited by Louise DeSalvo and Mitchell Leaska.

Vita: The Life of Vita Sackville-West by Victoria Glendinning

Virginia Woolf by Hermione Lee

A Writer’s Diary by Virginia Woolf (edited by Leonard Woolf)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is an author, poet and artist with a serious case of wanderlust. She is originally from the UK, but has spent time abroad in Europe, the United States and the Bahamas.

When not traveling or working on her current projects — a chapbook of poetry, “The Cabinet of Lost Things,” and a novel based on the life of modernist writer and illustrator Djuna Barnes — she can be found with her nose in a book, daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Visit her on the web at Elodie Rose Barnes.

This review of Vita and Virginia (2019 film) is typical of the tepid response to the film

The post Beyond the Legend: Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West’s Love Affair & Friendship appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Fearless Journalist and Crusader for Justice

Ida B. Wells (1862–1931), also known as Ida B. Wells-Barnett, was a fearless journalist and crusader in the early civil rights movement. She was a feminist, editor, sociologist, and one of the founders of the NAACP.

She was best known for spearheading a national antilynching campaign, through which she worked tirelessly to end the uniquely American practice of the public mob murders of African-Americans. Wells’s reputation has continued to grow after her death.

There have been journalism awards established in her name as well as scholarships endowed in her honor, and there is even a museum celebrating her legacy in her hometown in Mississippi.

In 2020, nearly 90 years after her death, Ida B. Wells was awarded a long overdue posthumous Pulitzer Prize in the category of Special Citations and awards for “her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching.”

Early life

The following biography of Ida B. Wells is excerpted from Afro-American Women Writers 1746 – 1933 by Ann Allen Shockley:

For more than forty years Ida B. Wells was one of the most fearless and one of the most respected women in the United States.” She was widely known as a crusading editor, journalist, organizer, lecturer, social reformer, and feminist.

Born a slave on the threshold of freedom, 16 July 1862, at Holly Springs, Mississippi, Ida Bell Wells was the oldest of eight children. Her parents were Jim Wells, son of his master and a highly skilled carpenter, and Elizabeth Warrenton, an expert cook. The two were married in slavery and repeated their vows when freed.

Deeply religious, Ida’s parents instilled in her biblical teachings and the importance of getting an education. She went to Rust College in her hometown, a Freedmen’s Aid school with all grade levels. A “pretty little girl, slightly nut-brown, with delicate features” she became an exceptional student in the school where her father was a member of the first Trustee Board.

When the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 reached Holly Springs, Ida’s parents and their youngest child died. Two other children had passed on earlier, leaving Ida and her four brothers and sisters.

Showing at the age of fourteen the strength and determination that marked her all her life, she undertook to keep the family together.

After passing the examination for county schoolteacher, she was assigned a one-room school six miles away. After one term, she was encouraged by a widowed aunt to come to Memphis to teach and live with her. While studying for the city school examination, she taught in Shelby County.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Refusal to move from a white train car and litigation

In May 1884, when she was traveling on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad to teach in Woodstock, Tennessee, a conductor asked her to move to the smoking car. When she refused, the conductor, with the assistance of the baggage man, tried to force her out. During the fracas, lda braced her feet on the back of the seat and bit the conductor’s hand.

Getting off at the next stop, she returned to Memphis and brought a suit against the railroad. She won the case and was awarded five hundred dollars and damages.

In writing of her victory, the white Memphis Daily Appeal of December 25, 1884, captioned the story: “A Darky Damsel Obtains a Verdict for Damages against the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad.”

Her triumph was short-lived, however, for the railroad appealed and the Supreme Court of Tennessee reversed the decision on April 5, 1887. It was the first case in which a colored plaintiff in the South had appealed to a state court since the repeal of the Civil Rights Bill by the United States Supreme Court.

First forays into journalism

Ida qualified to teach in the Memphis school system, and became a primary grade teacher for seven years. To further her education, she attended summer school at Fisk University, studied privately with experienced teachers, and read voraciously.

Her writing talent emerged when she was elected editor of a small church paper, the Evening Star. Then, much to her surprise, for she had no newspaper training, she was invited to contribute to the Living Way, a Baptist weekly. Adopting the pen name of “Iola,” she wrote her first article for the paper on the railroad suit.

Soon the young journalist, who had learned to “handle a goose-quill, with diamond point, as easily as any man in the newspaper work,” was in demand. She wrote for the American Baptist, Detroit Plaindealer, Christian Index, Indianapolis World, Gate City Press, and A. M. E. Review.

She also edited the “Home” department of Our Women and Children. Called the “brilliant Iola” and “Princess of the Press,” she was the first woman to attend the Afro-American Press Convention in Louisville, Kentucky, and was elected assistant secretary. There she read a paper, “Women in Journalism, or, How I would Edit.”

Buying into newspaper ownership

Her opportunity to edit a paper came when she bought a one-third interest in the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight in 1889.

Not one to hold her tongue or her pen, she wrote an article about the poor conditions of the local black schools, deploring not only the physical structures but the inadequacies of the teachers also. The exposé provoked ill feeling against her among both blacks and whites, and she was not rehired to teach the following year.

She had never particularly enjoyed teaching because of its “confinement and monotony,” and now she set out to express what she called her “real me” in newspaper work.

Shortening the name of the paper to the Free Speech, she devoted full-time to traveling for the paper and making it a success.

Free Speech soon became a household word “up and down the Delta.” It was printed on pink paper so the illiterate could identify it, and circulation increased from fifteen hundred to four thousand.

Urging black people to move west to escape lynching

On March 9, 1892, the lynching in Memphis of three young black businessmen, owners of the People’s Grocery Company and friends of Ida’s, changed the direction of her life.

Away at the time in Natchez, Mississippi, she returned to write blistering editorials that condemned whites for permitting the lynching and urged its black citizens to leave the city and go west.

Hundreds of black people began to move away, including entire church congregations. She also encouraged blacks to boycott white businesses, introducing the first black boycott.

A serious death threat

In May, Ida B. Wells left an editorial at the paper to be published while she attended the A. M. E. General Conference in Philadelphia, where she was to be the guest of author Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. From there, she was scheduled to go to New York to see T. Thomas Fortune, the brilliant editor of the New York Age.

While in the company of Fortune, she learned about the destruction of her press by an angry white mob. Her partner, J. C. Fleming, had been run out of town, and friends sent word warning her not to return, for whites were threatening to kill her on sight.

The editorial that ignited the wrath of whites concerned the lynching of black men because of white women:

“Nobody in this section believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men assault white women. If southern white men are not careful they will over-reach themselves and a conclusion will be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Militant anti-lynching writings

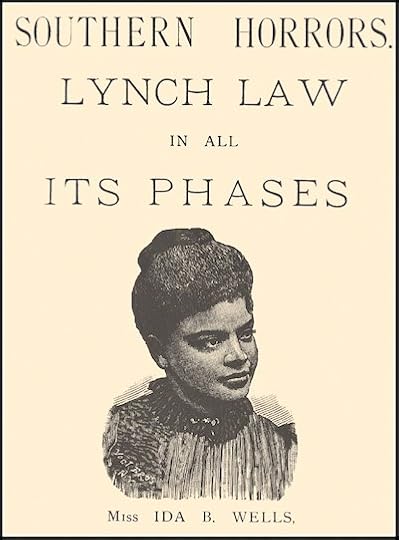

Now an exile from home, Ida was asked by T. Thomas Fortune to write for the New York Age. For the June 5, 1892 issue, she substantiated her Memphis editorial by writing an incisive factual front-page piece on lynching. Four months later, it was published again in pamphlet form and called Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892).

Her writing aroused the interest of the eminent race leader, Frederick Douglass, who published a letter in the pamphlet citing her as a “Brave woman!” That was the beginning of a lifetime friendship between the two.

Ida B. Well’s militant writings against lynching awakened other black women to rally behind her cause. Victoria Earle Matthews, writer and reformer of New York, and Maritcha Lyons, a Brooklyn schoolteacher, led a group of black women to give lda a testimonial at Lyric Hall, in October, 1892. She was presented with five hundred dollars and a gold brooch in the shape of a pen.

This event turned out to be an important occasion in her life, for before a large gathering of prominent black women, she gave her first public lecture on the horrors of lynching. The testimonial had another historic aspect also, for it laid the groundwork for the beginning of the black women’s club movement.

A writer and speaker in demand

Out of it came the Women’s Loyal Union. Ida B. Well’s ability as an organizer was readily recognized, and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin of Boston asked her to assist in forming the Woman’s Era Club. Earning the title “Mother of Clubs,” she helped form women’s groups throughout New England and in Chicago, where one was named in her honor.

She was an outstanding worker in the National Association of Colored Women and, in 1924, ran for president against Mary McLeod Bethune.

Ida now was receiving numerous requests to speak on the subject of lynching. During April and May of 1893, she traveled to England, Scotland, and Wales, and in 1894 visited England again for six months. Her speeches there led to the formation of an Anti-Lynching Committee.

Besieged to write as well as to speak, she was asked to send back articles about her trip to the Chicago daily paper, the Inter-Ocean (subsequently the Herald-Examiner), writing a column “Ida B. Wells Abroad.” She commented in her autobiography that she was the first black person to become a regular paid correspondent for a daily paper in the United States.

Always quick to publicize racial disparities, she protested against the barring of blacks from the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. She, along with Frederick Douglass and Frederick J. Loudin, an original Fisk University Jubilee Singer, appealed for funds to publish a pamphlet protesting the discrimination.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Settling in Chicago; becoming a wife and mother

Ida B. Wells settled in Chicago, where she wrote her indictment, A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States, 1892-1893-1894 (1895). This notable work presented both lynching statistics and its history.

She joined the staff of the first black Chicago newspaper, the Conservator, which was owned by Ferdinand L. Barnett, a widower and attorney. Romance entered the picture, and on June 27, 1895, Ida married Barnett. They had four children, but motherhood did not stop her from continuing her writing and lecturing.

In the role of social reformer, she founded the Negro Fellowship League in the most blighted section of Chicago’s South Side. The league gave a refuge to those who were homeless, offered religious services, and helped the unemployed. As the first black woman to be appointed a probation officer, she used the league’s services to assist with her work.

An aggressive feminist, she organized in January 1913 the first suffrage group composed of black women, the Alpha Suffrage Club, which published a newsletter, the Alpha Suffrage Record.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

A focus on antilynching activism

She was called upon also to investigate riots in such places as Springfield, Illinois; Elaine, Arkansas; and East St. Louis. Her stories on these events ran in the Chicago Defender, Broad Ax, and Whip. She carried her mission against mob rule all the way to the White House in 1898.

Armed with resolutions from a Chicago rally against lynching, she presented them to President William McKinley. In 1900, she published a pamphlet, Mob Rule in New Orleans: Robert Charles and His Fight to the Death.

A firm believer in organizing for unity, she was one of the original group who, with W. E. B. Du Bois, conceived of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

. . . . . . . . .

10 Pioneering African-American Women Journalists

. . . . . . . . . .

The legacy of Ida B. Wells Barnett

All through her life, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a dynamic, bold, and strong-minded woman who fought against lynching and for the rights of her people.

She spoke her mind whenever the occasion warranted, and because of this, she was frequently “not only opposed by whites, but some of her own people were often hostile, impugning her motives.”

She fought a “lonely and almost single-handed fight” against lynching long before men or women of any race entered the arena.”

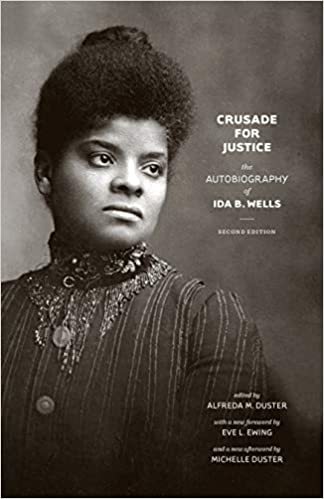

She left her story in an autobiography begun in 1928. Her memoirs were eventually edited by her daughter, Alfreda M. Duster, and published under the title Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of lda B. Wells (1970).

On March 25, 1931, Ida B. Wells died of uremic poisoning. In 1940, the Chicago Housing Authority named a housing project on the South Side in her honor. Ten years after that, the city designated her as one of the twenty-five outstanding women in Chicago’s history.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Books by and about Ida B. Wells-Barnett on Amazon*

More about Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Books by Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Southern Horrors: Lunch Law in all its Phases (1892)

A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States, 1892-1893-1894 (1895)

Lynch Law in Georgia (1899)

Mob Rule in New Orleans: Robert Charles and His Fight to the Death (1900)

Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells, edited by Alfreda M. Duster (second edition, 2020)

Biography

To Keep the Waters Troubled: The Life of Ida B. Wells by Linda McMurry (1999)

Ida: A Sword Among Lions by Paula Giddings (2009)

Passionate for Justice: Ida B. Wells as Prophet for Our Time by Catherine Meeks (2019)

More information

Wikipedia

National Women’s History Museum

Works by Ida B. Wells-Barnett at Project Gutenberg

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing

The post Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Fearless Journalist and Crusader for Justice appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 8, 2020

Two Jane Austen-inspired Novels by Sonali Dev: Pride, Prejudice, and Other Flavors & Recipe for Persuasion

It is a truth universally acknowledged that there are Jane Austen fans so devoted that they read Pride and Prejudice (and/or her other novels) every year or two. Contemporary Austen-flavored retellings only add fuel to the literary fire. In that vein, the witty pen of Sonali Dev has produced Pride, Prejudice and Other Flavors (2019) and Recipe for Persuasion (2020).

For fervent devotees, for whom there can never be Too Much Jane, Ms. Dev’s novels will be a delicious treat. They transpose Austen-esque complicated relationships to the modern world, and season them with culinary themes. Here’s a look at these entertaining reads by Sonali Dev.

Pride, Prejudice, and Other Flavors By Sonali Dev

A compelling, gender-swapped modern retelling of Jane Austen’s classic Pride and Prejudice by critically acclaimed author Sonali Dev provides a poignant exploration of cultural assimilation, identity, and the true places our hearts learn to call home. Pride, Prejudice and Other Flavors (William Morrow, 2019) gives powerful voice to two charismatic characters who will delight readers.

Award-winning author Sonali Dev launches a new series about the Rajes — an immigrant Indian family descended from royalty, who have painstakingly built their lives in San Francisco.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that only in an overachieving Indian American family can a genius daughter be considered a black sheep.

Trisha, an empowered American woman descended from Indian royalty, and D.J., the British man who leaves behind his career and culinary acclaim to come to California to care for his grievously ill sister.

. . . . . . . . .

Pride, Prejudice and Other Flavors is available on Amazon*

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . .

Dr. Trisha Raje is San Francisco’s most acclaimed neurosurgeon. But that’s not enough for the Rajes, her influential immigrant family who’s achieved power by making its own non-negotiable rules:

Never trust an outsider

Never do anything to jeopardize your brother’s political aspirations

And never, ever, defy your family

Trisha is guilty of breaking all three rules. But now she has a chance to redeem herself. So long as she doesn’t repeat old mistakes.

Up-and-coming chef DJ Caine has known people like Trisha before, people who judge him by his rough beginnings and place pedigree above character. He needs the lucrative job the Rajes offer, but he values his pride too much to indulge Trisha’s arrogance. And then he discovers that she’s the only surgeon who can save his sister’s life.

As the two clash, their assumptions crumble like the spun sugar on one of DJ’s stunning desserts. But before a future can be savored there’s a past to be reckoned with…

A family trying to build home in a new land. A man who has never felt at home anywhere. And a choice to be made between the two.

Sonali Dev cannily weaves references to challenges still faced by those of multi-ethnic heritage. And yet, Trisha’s family is as American as Tikka Masala. Her brother is running for Governor of California; her sister (hiding an unplanned, high-risk pregnancy) is his campaign manager; a dear cousin is the owner of a struggling neighborhood restaurant.

Their story is our story, and the infused beauty of the interwoven tales brims with flavor and delight. Pride, Prejudice and Other Flavors is at once a compelling, heartwarming romance between two strangers from completely different worlds, and a poignant examination of cultural assimilation, identity, and an exploration of the places we come to call “home.”

“Like a gender-swapped Pride and Prejudice, sparks fly … Dev’s fifth novel faces such issues as cultural assimilation, familial forgiveness, and medical ethics head-on. Her descriptions … are mouthwatering. Ideal for romantics and foodies alike.” — Booklist

Recipe for Persuasion by Sonali Dev

When waiting for a new book is half agony, half hope … acclaimed author Sonali Dev Delivers!

“I must speak to you by such means as are within my reach. You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope. Tell me not that I am too late, that such precious feelings are gone forever. I offer myself to you again with a heart even more your own than when you almost broke it, eight years and a half ago. Dare not say that man forgets sooner than woman, that his love has an earlier death. I have loved none but you. Unjust I may have been, weak and resentful I have been, but never inconstant.” — from Jane Austen’s Persuasion

A delicious reinterpretation of Persuasion, considered by some Jane Austen’s best novel, Sonali Dev’s Recipe for Persuasion (William Morrow, 2020) provides a poignant exploration of loves, romantic and familial, lost and re-found.

Executive editor Tessa Woodward notes, “Persuasion is the Austen novel most known for its well-rounded heart, emotional depth, what makes someone worthy of love and respect – and Sonali Dev has written Recipe for Persuasion to pay tribute to the subtle nuances of the original.”

Award-winning author Sonali Dev continues her new series about the Rajes — an immigrant Indian family descended from royalty, who have painstakingly built their lives in San Francisco.

Recipe for Persuasion is a clever, deeply layered, and heartwarming romantic comedy that follows in the Jane Austen tradition—this time, with a twist on Persuasion.

And while having a fun cooking hook, like Pride, Prejudice and Other Flavors, Recipe for Persuasion incorporates a darker thread of familial discord and dysfunction, a counterpoint to the pop-culture friendly plot.

The heroine is a renowned chef who has been paired with a soccer star on a reality competition, hoping to give her restaurant a much-needed publicity boost. Her partner just happens to be the one man she ever loved … and lost.

Chef Ashna Raje desperately needs a new strategy. How else can she save her beloved restaurant and prove to her estranged, overachieving mother that she isn’t a complete screw up?

When she’s asked to join the cast of Cooking with the Stars, the latest hit reality show teaming chefs with celebrities, it seems like just the leap of faith she needs to put her restaurant back on the map. She’s a chef, what’s the worst that could happen?

Rico Silva, that’s what.

. . . . . . . . .

Recipe for Persuasion is available on Amazon*

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . .

Being paired with a celebrity who was her first love, the man who ghosted her at the worst possible time in her life, only proves what Ashna has always believed: leaps of faith are a recipe for disaster. World Cup winning soccer star Rico Silva isn’t too happy to be paired up with Ashna either.

Losing Ashna years ago almost destroyed him. The only silver lining to this bizarre situation is that he can finally prove to Ashna that he’s definitely over her.

But when their catastrophic first meeting goes viral, social media becomes obsessed with their chemistry. The competition on the show is fierce…and so is the simmering desire between Ashna and Rico.

Every minute they spend together rekindles feelings that pull them toward their disastrous past. Will letting go again be another recipe for heartbreak—or a recipe for persuasion?

In Recipe for Persuasion, Sonali Dev once again takes readers on an unforgettable adventure in this fresh, fun, and enchanting romantic comedy.

“Clever allusions to Persuasion aside (even Jane Austen fans will be challenged to spot them all), this is a sumptuously multilayered story about the ways love gets tangled in family life and romantic relationships.” — Library Journal (Starred review)

“Dev balances the toe-curling romance with high-octane family drama, fleshing out Ashna’s strained relationship with her mother with touching flashbacks to her parents’ past. Dev’s candor and sensitivity in both story lines set this family-centric romance apart. Readers are sure to be impressed.” — Publishers Weekly (Starred review)

About the Author:

Award-winning author Sonali Dev writes Bollywood-style love stories that let her explore issues faced by women around the world while still indulging her faith in a happily ever after. Sonali lives in the Chicago suburbs with her very patient and often amused husband and two teens who demand both patience and humor, and the world’s most perfect dog. Find her on the web:

https://www.facebook.com/SonaliDev.author

https://twitter.com/Sonali_Dev

https://www.instagram.com/sonali.dev/

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Two Jane Austen-inspired Novels by Sonali Dev: Pride, Prejudice, and Other Flavors & Recipe for Persuasion appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 7, 2020

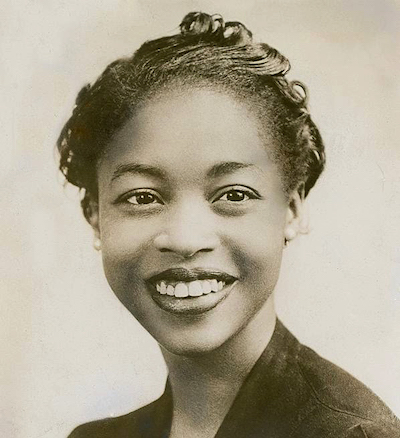

Margaret Walker

Margaret Walker (July 15, 1915 – November 30, 1998) was an American poet and novelist. She is recognized today as one of the foremost African-American female writers of her generation. In addition to her acclaimed novel, Jubilee (1966), she wrote several volumes of poetry.

Walker participated in the literary movement known as the Chicago Black Renaissance, and was a long-time friend of novelist and poet Richard Wright.

Walker was a university professor from the 1940s through the 1970s, and she held positions at colleges in North Carolina, West Virginia and Mississippi. She received six honorary degrees and was inducted into the African American Literary Hall of Fame in October 1998.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Early Life and Education

Margaret Walker was born in Birmingham, Alabama, on July 7, 1915. Her parents, Marion and Sigismund, introduced her to philosophy and poetry during her childhood.

The family moved to New Orleans when she was young, and she attended school there. As a child, she particularly loved the poetry of Langston Hughes, and began writing her own poems when she was 15 years old.

Walker received her bachelor’s degree from Northwestern University in 1935. While pursuing her studies there, she met Langston Hughes, who encouraged her to continue writing.

In 1936, Walker joined the Federal Writers’ Project and the South Side Writers Group, where she became friends with Richard Wright. In 1940, she received her master’s degree in creative writing from the University of Iowa.

The following year, Walker was awarded the Yale Younger Poets Prize for her debut collection of poetry, For My People, which was published in 1942. She was the first African-American person to be awarded this prize.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Family, Teaching and Early Career Highlights

In 1941, Walker began teaching at Livingstone College in North Carolina, and she taught at West Virginia State College in 1942. In 1943, she married Firnist Alexander, and her first child was born in 1944.

Throughout the 1940s, Walker researched her family history during the Civil War, compiling outlines and chapter titles for the novel that would later become her most famous work.

In 1949, Walker moved to Mississippi with her family, and she started teaching at Jackson State College. She re-enrolled at the University of Iowa in the early 1960s, graduating with her doctorate in 1965. She re-worked her doctoral dissertation into the form of a novel, and it was published as Jubilee in 1966.

. . . . . . . . . .

Margaret Walker page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Jubilee (1966)

Jubilee, Ms. Walker’s best known work, is a novel based on the personal history of Ms. Walker’s great-grandmother. It follows Vyry, a slave on a plantation in Georgia, as she grows from childhood to adulthood during the antebellum period, the Civil War and the Reconstruction era.

The novel has been praised for its realistic depiction of daily life as a slave, and each of the 58 chapters begins with a proverb or an excerpt from a spiritual. Crispin Y. Campbell, a Washington Post contributor, hailed the work as “the first truly historical black American novel.”

While teaching at Jackson State College in 1968, Ms. Walker founded the Institute for the Study of the History, Life, and Culture of Black People at the college. The institute was later renamed as the Margaret Walker Center in her honor.

As the director of the institute, Margaret organized many events throughout the 1970s, including the 1973 Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival.

Later Works

Prophets for a New Day, a collection of poetry, was published in 1970. With the exception of “Elegy” and “Ballad of the Hoppy Toad,” the poems are focused entirely on the civil rights movement.

Many of the poems use biblical allusions, and historical events, major cities and important leaders associated with the movement are prominently featured.

How I Wrote Jubilee was published in 1972. In this work, Walker explains the creative process behind the novel, detailing the oral history she received from her grandmother and citing the historical references that served as the underpinning for her story. Another collection of poetry, October Journey, was published in 1973.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Later Years and Legacy

In 1979, Margaret Walker retired from teaching. During the 1980s and 90s, she continued to write both poetry and prose. Richard Wright: Daemonic Genius, a nonfiction work which drew from her friendship with Richard, was published in 1988, and This Is My Century: New and Collected Poems followed in 1989.

In the 1990s, Walker published two volumes of essays. The last of these was On Being Female, Black, and Free (1997), and it became her final publication.

During her lifetime, Walker received numerous awards. In addition to Fulbright Commission, Ford Foundation, Rosenwald Foundation, and National Endowment for the Humanities fellowships, she received the Living Legacy Award from President Carter.

She was the recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award for Excellence in the Arts, and the College Language Association also honored her with their Lifetime Achievement Award.

Walker died of cancer on November 30, 1998. Over a career that lasted nearly a century, her work spoke of the struggle for liberation and the importance of resilience and hope.

According to Tomeika Ashford, Margaret Walker was “one of the foremost transcribers of African-American heritage.” In 2014, she was posthumously inducted into The Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.

More about Margaret Walker

Major Works

For My People (poetry; 1942)

Jubilee (novel; 1966)

October Journey (poetry; 1973)

Richard Wright: Daemonic Genius (critical biography; 1988)

This Is My Century: New and Collected Poems. (1989)

How I Wrote Jubilee and Other Essays on Life and Literature (1990)

Biography

Conversations with Margaret Walker with Maryemma Graham (2002)

Song of My Life: A Biography of Margaret Walker by Carolyn J. Brown (2014)

More information

Poetry Foundation

Poets.org

Biography

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Margaret Walker appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 4, 2020

A New England Nun by Mary E. Wilkins Freeman – full text

Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman (1852 – 1930), more commonly known as Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, was an American novelist and short story writer. Though no longer widely read, her 1891 short story, “A New England Nun,” is widely anthologized and still studied.

Born in Randolph, Massachusetts, Freeman came from New England Puritan stock. A prolific writer of novels, short stories, children’s books, and poems, her work has been largely forgotten, though it’s widely available online, all of it being in the public domain.

Notably, she also wrote supernatural and weird fiction — a stark departure from her regionally-flavored New England tales. A 1911 encyclopedia entry on Freeman’s work stated:

“Her longer novels, though successful in the portrayal of character, lack something of the unity, suggestiveness and charm of her short stories, which are notable contributions to modern American literature.

She deals usually with a few traits peculiar to the village and country life of New England, and she gave literary permanence to certain characteristics of New England life which are fast disappearing.”

. . . . . . . . .

Mary E. Wilkins Freeman

. . . . . . . . . .

Summary of A New England Nun

Louisa Ellis promised Joe Dagget that she would marry him upon his return from fortune-hunting in Australia. The years stretched to fourteen, and in the meantime, Louisa made a quiet and orderly life for herself.

She liked to keep the house neat, serve herself her meals on her nicest china, and take care of her old dog, Cæsar, who she has kept chained since he bit a neighbor as a puppy.

Joe’s return makes Louisa unhappy. He’s a distraction and a disruption; he’s somewhat boorish and awkward. To make matters worse, he tracks dirt on her clean floors and knocks things over in her neat home.

Louisa realizes that marrying Joe would mean loss of her independence and her enjoyment of an orderly life, filled with small pleasures that could be defined as somewhat feminine.

A fellow townswoman, Lily Dyer, has been taking care of Joe’s mother in his absence. This only further confirms to Louisa that her quiet life would be upended if she married Joe. At this point it’s clear that she’s only planning to go through with it due to her years-long promis.

However, just weeks before the wedding date, Louisa comes upon Joe and Lily during an evening stroll. It’s apparent that they have developed feelings for one another. Joe has fallen in love with Lily, but feels beholden to Louisa. He tells Lily to find someone else, but she responds: “I’ll never marry any other man as long as I live.”

When Joe comes to call on Louisa the next day, she releases Joe from his promise without letting on that she overheard the conversation. They part amicably, with the last line of the story, “Louisa sat, prayerfully numbering her days, like an uncloistered nun.”

Analyses of A New England Nun

Here are three excellent analyses of this classic short story:

Encyclopedia

Owlcation

Grin

The text following is completely true to the original. The long paragraphs have been broken up for better readability.

A New England Nun (1891) – full text

It was late in the afternoon, and the light was waning. There was a difference in the look of the tree shadows out in the yard.

Somewhere in the distance cows were lowing and a little bell was tinkling; now and then a farm-wagon tilted by, and the dust flew; some blue-shirted laborers with shovels over their shoulders plodded past; little swarms of flies were dancing up and down before the peoples’ faces in the soft air.

There seemed to be a gentle stir arising over everything for the mere sake of subsidence — a very premonition of rest and hush and night.

This soft diurnal commotion was over Louisa Ellis also. She had been peacefully sewing at her sitting-room window all the afternoon. Now she quilted her needle carefully into her work, which she folded precisely, and laid in a basket with her thimble and thread and scissors.

Louisa Ellis could not remember that ever in her life she had mislaid one of these little feminine appurtenances, which had become, from long use and constant association, a very part of her personality.

Louisa tied a green apron round her waist, and got out a flat straw hat with a green ribbon. Then she went into the garden with a little blue crockery bowl, to pick some currants for her tea.

After the currants were picked she sat on the back door-step and stemmed them, collecting the stems carefully in her apron, and afterwards throwing them into the hen-coop. She looked sharply at the grass beside the step to see if any had fallen there.

Louisa was slow and still in her movements; it took her a long time to prepare her tea; but when ready it was set forth with as much grace as if she had been a veritable guest to her own self.

The little square table stood exactly in the centre of the kitchen, and was covered with a starched linen cloth whose border pattern of flowers glistened.

Louisa had a damask napkin on her tea-tray, where were arranged a cut-glass tumbler full of teaspoons, a silver cream-pitcher, a china sugar-bowl, and one pink china cup and saucer. Louisa used china every day — something which none of her neighbors did.

They whispered about it among themselves. Their daily tables were laid with common crockery, their sets of best china stayed in the parlor closet, and Louisa Ellis was no richer nor better bred than they.

Still she would use the china. She had for her supper a glass dish full of sugared currants, a plate of little cakes, and one of light white biscuits. Also a leaf or two of lettuce, which she cut up daintily.

Louisa was very fond of lettuce, which she raised to perfection in her little garden. She ate quite heartily, though in a delicate, pecking way; it seemed almost surprising that any considerable bulk of the food should vanish.

After tea she filled a plate with nicely baked thin corn-cakes, and carried them out into the back-yard.

“Cæsar!” she called. “Cæsar! Cæsar!”

There was a little rush, and the clank of a chain, and a large yellow-and-white dog appeared at the door of his tiny hut, which was half hidden among the tall grasses and flowers.

Louisa patted him and gave him the corn-cakes. Then she returned to the house and washed the tea-things, polishing the china carefully.

The twilight had deepened; the chorus of the frogs floated in at the open window wonderfully loud and shrill, and once in a while a long sharp drone from a tree-toad pierced it.

Louisa took off her green gingham apron, disclosing a shorter one of pink and white print. She lighted her lamp, and sat down again with her sewing.

In about half an hour Joe Dagget came. She heard his heavy step on the walk, and rose and took off her pink-and-white apron. Under that was still another — white linen with a little cambric edging on the bottom; that was Louisa’s company apron.

She never wore it without her calico sewing apron over it unless she had a guest. She had barely folded the pink and white one with methodical haste and laid it in a table-drawer when the door opened and Joe Dagget entered.

He seemed to fill up the whole room. A little yellow canary that had been asleep in his green cage at the south window woke up and fluttered wildly, beating his little yellow wings against the wires. He always did so when Joe Dagget came into the room.

“Good-evening,” said Louisa. She extended her hand with a kind of solemn cordiality.

“Good-evening, Louisa,” returned the man, in a loud voice.

She placed a chair for him, and they sat facing each other, with the table between them. He sat bolt-upright, toeing out his heavy feet squarely, glancing with a good-humored uneasiness around the room. She sat gently erect, folding her slender hands in her white-linen lap.

“Been a pleasant day,” remarked Dagget.

“Real pleasant,” Louisa assented, softly. “Have you been haying?” she asked, after a little while.

“Yes, I’ve been haying all day, down in the ten-acre lot. Pretty hot work.”

“It must be.”

“Yes, it’s pretty hot work in the sun.”

“Is your mother well to-day?”

“Yes, mother’s pretty well.”

“I suppose Lily Dyer’s with her now?”

Dagget colored. “Yes, she’s with her,” he answered, slowly.

He was not very young, but there was a boyish look about his large face. Louisa was not quite as old as he, her face was fairer and smoother, but she gave people the impression of being older.

“I suppose she’s a good deal of help to your mother,” she said, further.

“I guess she is; I don’t know how mother’d get along without her,” said Dagget, with a sort of embarrassed warmth.

“She looks like a real capable girl. She’s pretty-looking too,” remarked Louisa.

“Yes, she is pretty fair looking.”

Presently Dagget began fingering the books on the table. There was a square red autograph album, and a Young Lady’s Gift-Book which had belonged to Louisa’s mother. He took them up one after the other and opened them; then laid them down again, the album on the Gift-Book.

Louisa kept eying them with mild uneasiness. Finally she rose and changed the position of the books, putting the album underneath. That was the way they had been arranged in the first place.

Dagget gave an awkward little laugh. “Now what difference did it make which book was on top?” said he.

Louisa looked at him with a deprecating smile. “I always keep them that way,” murmured she.

“You do beat everything,” said Dagget, trying to laugh again. His large face was flushed.

He remained about an hour longer, then rose to take leave. Going out, he stumbled over a rug, and trying to recover himself, hit Louisa’s work-basket on the table, and knocked it on the floor.

He looked at Louisa, then at the rolling spools; he ducked himself awkwardly toward them, but she stopped him. “Never mind,” said she; “I’ll pick them up after you’re gone.”

She spoke with a mild stiffness. Either she was a little disturbed, or his nervousness affected her, and made her seem constrained in her effort to reassure him.

When Joe Dagget was outside he drew in the sweet evening air with a sigh, and felt much as an innocent and perfectly well-intentioned bear might after his exit from a china shop.

Louisa, on her part, felt much as the kind-hearted, long-suffering owner of the china shop might have done after the exit of the bear.

She tied on the pink, then the green apron, picked up all the scattered treasures and replaced them in her work-basket, and straightened the rug. Then she set the lamp on the floor, and began sharply examining the carpet. She even rubbed her fingers over it, and looked at them.

“He’s tracked in a good deal of dust,” she murmured. “I thought he must have.”

Louisa got a dust-pan and brush, and swept Joe Dagget’s track carefully.

If he could have known it, it would have increased his perplexity and uneasiness, although it would not have disturbed his loyalty in the least.

He came twice a week to see Louisa Ellis, and every time, sitting there in her delicately sweet room, he felt as if surrounded by a hedge of lace.

He was afraid to stir lest he should put a clumsy foot or hand through the fairy web, and he had always the consciousness that Louisa was watching fearfully lest he should.

Still the lace and Louisa commanded perforce his perfect respect and patience and loyalty. They were to be married in a month, after a singular courtship which had lasted for a matter of fifteen years.

For fourteen out of the fifteen years the two had not once seen each other, and they had seldom exchanged letters. Joe had been all those years in Australia, where he had gone to make his fortune, and where he had stayed until he made it.

He would have stayed fifty years if it had taken so long, and come home feeble and tottering, or never come home at all, to marry Louisa.

But the fortune had been made in the fourteen years, and he had come home now to marry the woman who had been patiently and unquestioningly waiting for him all that time.

Shortly after they were engaged he had announced to Louisa his determination to strike out into new fields, and secure a competency before they should be married.

She had listened and assented with the sweet serenity which never failed her, not even when her lover set forth on that long and uncertain journey. Joe, buoyed up as he was by his sturdy determination, broke down a little at the last, but Louisa kissed him with a mild blush, and said good-by.

. . . . . . . . .

Mary E. Wilkins Freeman page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

“It won’t be for long,” poor Joe had said, huskily; but it was for fourteen years.

In that length of time much had happened. Louisa’s mother and brother had died, and she was all alone in the world.

But greatest happening of all — a subtle happening which both were too simple to understand — Louisa’s feet had turned into a path, smooth maybe under a calm, serene sky, but so straight and unswerving that it could only meet a check at her grave, and so narrow that there was no room for any one at her side.

Louisa’s first emotion when Joe Dagget came home (he had not apprised her of his coming) was consternation, although she would not admit it to herself, and he never dreamed of it.

Fifteen years ago she had been in love with him — at least she considered herself to be. Just at that time, gently acquiescing with and falling into the natural drift of girlhood, she had seen marriage ahead as a reasonable feature and a probable desirability of life.

She had listened with calm docility to her mother’s views upon the subject. Her mother was remarkable for her cool sense and sweet, even temperament.