Nava Atlas's Blog, page 52

July 26, 2020

Film Adaptations of 17 Classic Children’s Novels by Women Authors

It’s fun and fascinating to watch film adaptations of classic children’s novels. Does the cast of characters match how you imagined them while reading? Is the film true to the book, or does it depart too much?

It’s a good idea to read a book first before seeing a film adaptation. That way, the cinematic visuals and actors don’t interfere with your imagination. Who can ever read the Harry Potter books again without picturing Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, and the rest of the actors in the film series?

Film and television adaptations can be helpful for kids who aren’t big on reading. In those cases, having them watch the movie first might be a way to get them more excited about reading the book it’s based on. Then, comparing the film and written versions might spark lively discussions.

For adults who have somehow missed reading certain classic children’s books and don’t want to invest the time (so many books to read, so little time …), the film adaptations can be a way to at least become familiar with classic stories. Though as I’ll point out, some adaptations are much better than others.

Once you’ve watched any book-to-movie adaptation, though, you may want to explore how the film differs from the original material. After all, they are interpretations, and often take liberties. I’d hate to consider that viewers of “Anne with an E,” which was presented on Netflix, for example, would think that this series reflects the spirit of the books. It doesn’t, but we’ll get to that later.

And now to the list of films based on books intentionally written for children. Many of their film counterparts are meant for audiences of all ages. For more films based on classics by women authors, see this site’s Filmography.

. . . . . . . . . . .

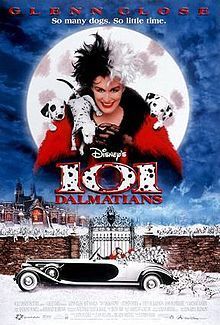

101 Dalmatians

The 101 Dalmatians (originally published as The Hundred and One Dalmatians) by Dodie Smith was published as a book for young readers in 1956. The story of Dalmatians Pongo and Missis, and the Dearlys (their humans), became an instant classic. The intrigue, carried to the screen, involves Cruella de Vil and her plot to steal the Dalmatian puppies and make coats out of them.

The story’s screen debut was a 1961 animated film produced by Disney. The 1996 live-action remake starring Glenn Close as Cruella received mixed reviews; many critics called the remake pointless. Audiences felt differently, apparently, and there was enough interest to release a sequel in 2000 titled 102 Dalmatians. Once again, audiences seemed happier with the film than the critics, and it did well at the box office.

. . . . . . . . . . .

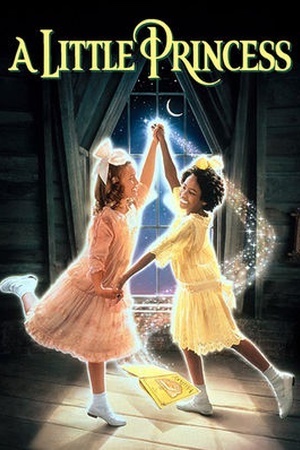

A Little Princess

The classic tale by Frances Hodgson Burnett, A Little Princess was published in full in 1905 after first appearing as the novella Sara Crewe and then being serialized. It tells the story of Sara, the daughter of a wealthy man who is indeed treated like a little princess upon her arrival at a posh English boarding school. But when her father goes missing, she is kept on at the school as a charity case, compelled to work as a servant.

Though Sara is abused by the headmistress and tormented by her fellow students, she holds her head high. The story of courage and kindness has resonated with audiences for generations and has been filmed several times, including the 1939 tearjerker (The Little Princess) starring Shirley Temple, a 1986 mini-series, and a lavishly produced 1995 film.

. . . . . . . . . . .

A Wrinkle in Time

Madeleine L’Engle’s 1962 classic fantasy novel A Wrinkle in Time, written for middle grade and up, blends religion, philosophy, mathematics, satire, and allegory. What’s surprising is that the prolific author had quite a hard time finding a publisher for it — editors thought that the exploration of good and evil was too dark and difficult for children. But in effect, the success of L’Engle’s work paved the way for related works like the Harry Potter series.

Wrinkle was first made into a 2003 television film that got mostly negative reviews. 2018’s star-studded remake, starring Oprah Winfrey, Reese Witherspoon, and Mindy Kaling didn’t fare much better, though it was commended for casting a Black actress in the role of the lovably nerdy heroine, Meg Murry. Fans of the book were generally disappointed in this film; I list it here because of all the hype it received. The definitive adaptation of this beloved novel is yet to be made.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Anne of Green Gables

Anne of Green Gables (1908) the first of many books by L.M. Montgomery and the start of a series, has been adapted to film numerous times.

“Anne with an E” — a 2017 adaptation for Netflix — received mixed reviews, and some viewers even panned it for its somewhat dystopian presentation of the Anne story. It was released at a time when the sunny original was needed more than ever. One of the best versions is the 1985 two-part CBC series.

Another beloved series by L.M. Montgomery is Emily of New Moon, yet another literary orphan who is sent to live with icy relatives in Prince Edward Island. Her character, a plucky girl who wants to be a writer, is one that the author identified with more than the more famous Anne. This series of books was adapted to a multi-season television series starting in 1998.

Unfortunately, it’s difficult to find a way to stream the series without a subscription service, which is why I didn’t list it separately. You might see if you can find it at your local library system.

. . . . . . . . . .

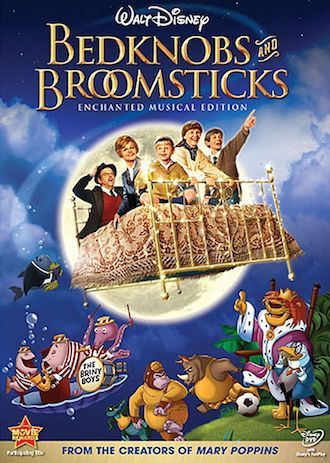

Bedknobs and Broomsticks

This movie title needs an explanation, since it wasn’t an actual book title, but rather, the name of the film, which combines two books by Mary Norton.

Her first novel, published in 1943, was The Magic Bed-Knob; Or, How to Become a Witch in Ten Easy Lessons. The books tell the story of three young siblings in World War II London who embark on some fantastic adventures as they seek shelter from the Blitz.

This book and its sequel, Bonfires and Broomsticks, were very popular. Eventually, they were combined and adapted into the 1971 Disney film Bedknobs and Broomsticks, which won an Oscar for best special visual effects for its combining of live-action and animation. Despite mixed critical reviews, it was nominated for four other categories, which might hint at its crossover appeal to adults as well as children.

. . . . . . . . . .

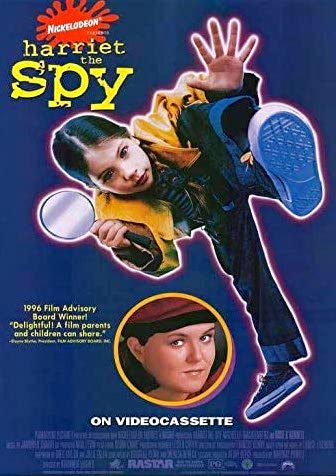

Harriet the Spy

Harriet the Spy, the 1964 children’s novel by Louise Fitzhugh is set in Manhattan’s upper east side. Its 11-year-old heroine, Harriet M. Welsch, already knows that she wants to be a famous writer when she grows up.

To prepare for her ambitions, she keeps a notebook in which she records details of the world around her in minute detail — and which ultimately leads to big trouble. Harriet the Spy became an entertaining 1996 Nickelodeon film.

. . . . . . . . . .

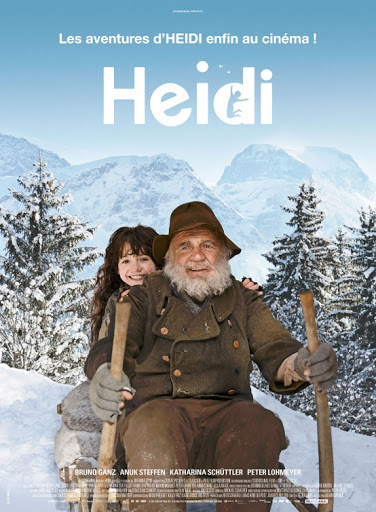

Heidi

Heidi, the story of an orphaned (of course!) little girl who lives in the Alps with her gruff grandfather and helps him tend goats, is a children’s classic by Swiss author Johanna Spyri, published in 1881. Heidi is taken to a distant city to become a companion to an invalid girl and longs to return to her home in the mountains.

Heidi has been adapted to film several times, the best known of which are the well-received 2015 Swiss-German film, and the 1937 version starring Shirley Temple. There are far too many adaptations of Heidi to discuss, here is a thorough, if not complete list.

. . . . . . . . . .

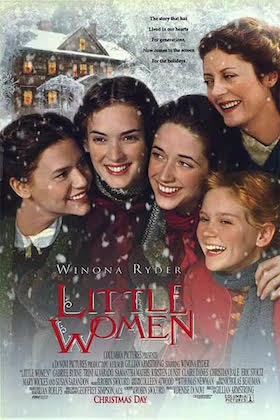

Little Women

Louisa May Alcott’s 1868 classic, Little Women, was originally written as a “girl’s book” that she thought would be a throwaway. Of course, it has been beloved by generations of readers of all ages. And it has been adapted for film and television numerous times.

My personal favorite is the 1994 movie starring Winona Ryder as Jo March. Little Women has made a statement on the big screen numerous times, from the hit 1934 film starring Katherine Hepburn to the 2019 adaptation with Saoirse Ronan. I have a feeling the latest one won’t be the last.

For thoughtful commentary on how the book’s film adaptations have been treated through the generations, see this video by Be Kind Rewind and this one from By the Book. They’re both excellent, and will make you want to watch all the adaptations, if only to compare them for yourself!

. . . . . . . . .

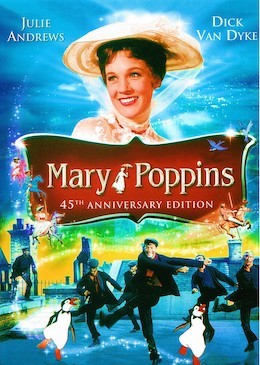

Mary Poppins

One of the best-loved (if most understood) characters in children’s literature, Mary Poppins grew from a story that its author, P.L. (Pamela Lyndon) Travers made up while minding two young children.

If Mary Poppins brings to mind Julie Andrews’ portrayal of her in the 1964 film, you’ll be surprised by her portrayal in the books as a more prickly and complex character. Still, the 1964 film is an iconic Disney movie musical.

Late 2018 saw a cinematic revival with Mary Poppins Returns starring Emily Blunt in the title role and Lin Manuel Miranda in altered iterations of the roles created by Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke in the 1964 Mary Poppins film. The film, released in time for the holiday season, evidently brought more cheer to audiences than to critics.

. . . . . . . . . .

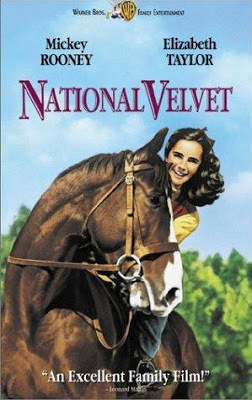

National Velvet

National Velvet is the story of a horse-crazy fourteen-year-old girl, Velvet Brown, who trains her horse, Pi, in hopes of winning Britain’s Grand National steeplechase. The 1935 novel of the same name was successfully adapted to film in 1944 and featured the young Elizabeth Taylor in her first leading role.

National Velvet remains the best-known work by Enid Bagnold (1889 – 1991), the British author not otherwise associated with children’s literature.

. . . . . . . . . .

Pippi Longstocking

The original three books in the Pippi Longstocking series by Astrid Lindgren have made this Swedish author one of the world’s most-translated, with 144 million copies worldwide. The story plunges the reader into the adventures of Pippi, a nine-year-old pigtailed redhead with superhuman strength.

Pippi Longstocking was first made into a Swedish film in 1969, and was actually a compilation of the Swedish TV series episodes. It was released in the U.S. in 1973. Pippi in the South Seas debuted in 1970. The New Adventures of Pippi Longstocking, which came out in 1988, was a Swedish-American joint venture.

All of the films received mixed reviews from adult critics, though they’re fine — and fun — for kids. Still, it’s best to start with the hilarious books, which have been entertaining young readers for generations.

. . . . . . . . . .

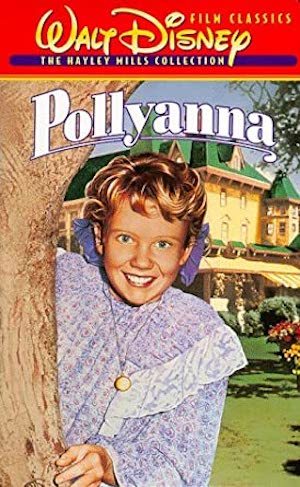

Pollyanna

The 1913 novel Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter (1868 – 1920) is perhaps less familiar now than the lasting expression that grew from its sentimental story. The first film adaptation appeared in 1920 with Mary Pickford in the title role.

The 1960 Disney adaptation is the best known. Hayley Mills won a special Oscar for her portrayal of Pollyanna. The film departs in some significant ways from the book; still, it was a major box-office and critical success. More recently, Pollyanna was adapted into a 2003 made-for-TV film.

. . . . . . . . . .

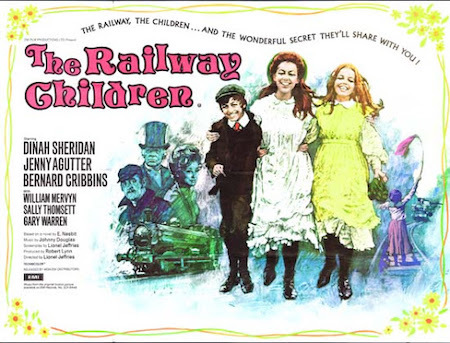

The Railway Children

Until the railway children’s father was sent to prison they had lived a conventional existence — watched and looked after every moment of the day. But when the children came to live in Three Chimneys, all these things vanished. There were no modern conveniences at all, not even running water. But what child cares about such things? What was thrilling for the children was that there was no school and no one to look after them.

In a nutshell, that’s the best-known book by E. Nesbit, the author of many imaginative books for children. Suprisingly, The Railway Children isn’t even better known, given that there have been several adaptations — two televisions series (1957 and 1968), and a few films, the most recent of which was in 2016. The 1970 film seems to be the most universally acclaimed.

. . . . . . . . . .

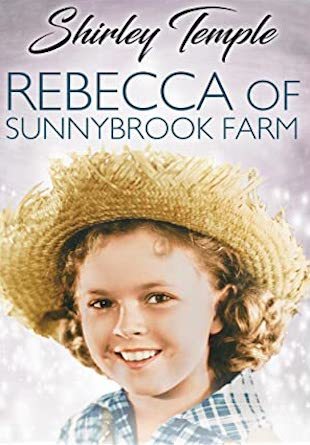

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm

When Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm first came out in 1903, a reviewer wrote: “For anyone suffering with the blues one could not do better than to prescribe this last book of Kate Douglas Wiggin, with the certainty that it would effect a cure. The writer may have done better work than this, but surely she never created a more wholly delightful character than Rebecca.”

Rebecca was one of several literary orphan girls of the era, along with Anne of Green Gables and Pollyanna, who won the hearts of dour spinsters and entire towns. It was adapted to film several times — first as a 1917 silent movie, then again in 1932, before emerging as a much-altered movie musical in 1938 starring Shirley Temple.

More recently, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was a 4-part television series that aired in 1978.

. . . . . . . . . .

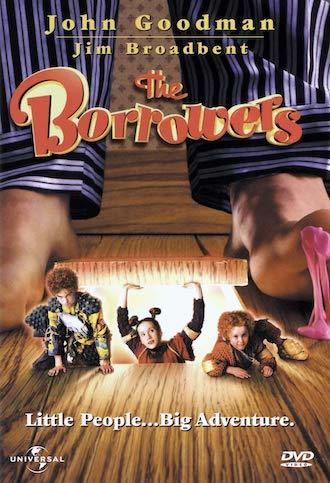

The Borrowers

The Borrowers, the first of a series of books by Mary Norton (1903 – 1992) first published in Great Britain in 1952 and in the U.S. in 1954, the Borrowers are miniature humans who live behind the wainscoting or under the floors of big old houses. They survive by borrowing whatever it is they need, as their name implies.

The first film version of The Borrowers was released in 1997. It’s loosely based on the book, rather than a faithful adaptation, and it received mixed reviews. A Japanese manga-style animated version of The Borrowers called The Secret World of Arrietty, with an all-star Western cast, came out in 2010.

In 2011, a British television film version of The Borrowers premiered. I suspect we haven’t seen the last of The Borrowers on the large and small screen, so it may be wise to read the books before exploring these or any future film adaptations!

. . . . . . . . .

The Boxcar Children

Created by grammar school teacher Gertrude Chandler Warner, the original volume of The Boxcar Children was first published in 1924. It proved so popular that it grew into a series of more than 150 titles.

Henry, Jessie, Violet, and Benny are four orphans who live in an abandoned train boxcar in the woods. They meet their grandfather, a kind and wealthy man, and when they move in with him, they keep the boxcar in the back yard to continue to use as a playhouse.

The Boxcar Children came out in 2014 as an animated film, followed by a sequel, The Boxcar Children: Surprise Island. Given the enduring popularity of the books, it’s rather surprising that a live-action film has yet to be made.

. . . . . . . . .

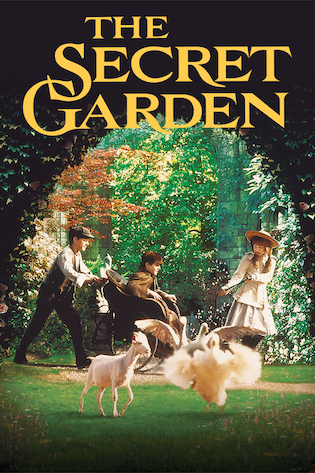

The Secret Garden

The Secret Garden, the timeless 1911 tale by Frances Hodgson Burnett tells of Mary Lennox, a sickly and neglected 10-year-old born to wealthy British parents in colonial India. After being orphaned, Mary is sent to England to live with her uncle in a mysterious house.

The tale follows Mary as she slowly sheds her sour demeanor after discovering a secret locked garden on the grounds of her uncle’s manor. She befriends Dickon, a free spirit who can communicate with animals, and Colin, her uncle’s son, a neglected and lonely invalid.

There were two minor film adaptations (one silent) before what is considered the definitive screen version of The Secret Garden premiered in 1993. Rotten Tomatoes said that it “honors its classic source material with a well-acted, beautifully filmed adaptation that doesn’t shy from its story’s darker themes.”

The post Film Adaptations of 17 Classic Children’s Novels by Women Authors appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 22, 2020

Katharine Graham, Legendary Publisher at The Washington Post

Katharine Graham (June 16, 1917 – July 17, 2001) is best remembered for her role as publisher and CEO of The Washington Post. She oversaw the newspaper’s involvement in the Pentagon Papers controversy and its investigation of the Watergate scandal that led to President Nixon’s resignation in late 1974.

Born in New York City, Katharine Meyer was one of five children raised in a family of great wealth. Her father, Eugene Meyer, was a multimillionaire and businessman who was Chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve from 1930 – 1933. Her mother, Agnes Ernst Meyer, was a politically active educator.

Eugene Meyer left his work in private business and government service to buy and revive The Washington Post in 1933 when the paper was being sold at a bankruptcy sale. He worked to improve the newspaper and in time, it became known for its precise editorial quality and independent reporting. Agnes Meyer was involved in politics and welfare work and maintained social relationships with powerful men, including Thomas Mann (the German novelist and philanthropist) and Adlai Stevenson, the lawyer and politician.

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

Young adulthood and marriage

Katharine attended Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York from 1932 to 1936, and graduated from the University of Chicago in 1938. She briefly worked as a reporter for the San Francisco News before joining her father at the Washington Post. She began an editorial staff member and worked in circulation departments in the daily paper as well as the weekend supplement, the Sunday Post.

In 1940, Katharine married Philip Graham, a lawyer who clerked for Felix Frankfurter, the Supreme Court justice. Eugene Meyer made his son-in-law publisher of the Washington Post in 1946.

Katharine didn’t object, and as a product of her time, quietly assumed the role of wife and mother. The couple had four children: Elizabeth Weymouth, Donald, William, and Stephen Graham. She sacrificed her career in journalism to be able to raise her children.

Katharine and Philip Graham bought the voting stock of the corporation from Graham’s father in 1948, allowing them to vote on important decisions regarding the corporation’s operations.

Busy with her children, Katharine continued to stay away from the mass media corporation while her husband ran the Post. It was an intensely competitive time in the news business, and under Philip Graham’s authority, The Washington Post bought Newsweek in 1961 to expand its coverage overseas.

. . . . . . . . .

Katharine Graham in 1997

. . . . . . . . .

Taking over the Post

Philip Graham struggled with alcoholism and mental illness throughout the marriage. After he committed suicide in 1963, Katharine had to assume the position as de facto publisher of the Washington Post Company. She continued to bolster the newspaper’s prestige and eventually took over as the official Publisher and Chief Executive Officer, becoming the first woman CEO of a Fortune 500 Company.

She remained in that position until 1979, when her son, Donald Graham assumed it. Donald Graham is currently chairman and chief executive officer of the board of the Washington Post Company.

. . . . . . . . .

Katharine Graham and Ben Bradlee

. . . . . . . . .

Watergate and the Pentagon Papers

One of the most exemplary cases of investigative journalism is the famed Watergate scandal that started brewing in the summer of 1972. Eventually, this would lead to Nixon’s resignation in 1974.

With the help of executive director Ben Bradlee, appointed in 1968, Katharine Graham oversaw the risky investigation that exposed the massive cover-up Nixon plotted by publishing excerpts of a top-secret Department of Defense report on June 18, 1971.

The U.S. Justice Department issued a restraining order disallowing the publication of such files for public consumption, but this caused such an uproar that the U.S. Supreme Court lifted the restraining order so that the publication would resume.

After Daniel Ellsburg leaked information about the American military and political involvement in the war with Vietnam (which came to be known as The Pentagon Papers) to the New York Times in 1971, Nixon was caught abusing his presidential powers and sought to destroy Ellsburg’s career.

When Nixon was found guilty of secretly taping his White House meetings, it was determined that he used his aides to cover up burglaries and other nefarious activities. This infamous case led to a new wave of journalism that questioned authority, introduced a new way of conducting news professionalism, and demonstrated the need for investigative journalism to speak truth to power.

The investigation not only led to Nixon’s resignation but also earned The Washington Post a Pulitzer Prize in 1973 for its groundbreaking work.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

The Post on film (2017) and Katharine Graham’s legacy

The 2017 film, The Post, depicts the Washington Post’s long battle to publish the Pentagon Papers, top-secret documentation about the U.S involvement in the Vietnam War. It also depicted the newspaper’s struggle to obtain sources that their competitors didn’t have access to.

The Post showcases how Katharine Graham (Meryl Streep), Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks), and others risked their careers to expose the truth. In the course of the film, Katharine Graham’s lack of experience in publishing as well as lack of self-confidence came through. She was constantly overruled by her male counterparts, including her editor-in-chief and financial advisors.

But she was determined not only to learn about the newspaper business and to do the right thing, which is why she has become a feminist icon.

Katharine Graham overcame her fears rose to the challenges and complications of running a newspaper business and became a role model for women who would follow in that profession. The Washington Post’s dedication to excellent journalism, led by Katharine Graham, continues to inspire journalists around the world.

More about Katharine Graham & Sources

Britannica (Katharine Graham)

Pulitzer Prize Winner Katharine Graham

Britannica (Washington Post)

What The Post (film) Misses About Katharine Graham

The News Media: What Everyone Needs to Know. Anderson, Christopher William, et al. Oxford University Press, 2016.

The post Katharine Graham, Legendary Publisher at The Washington Post appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 20, 2020

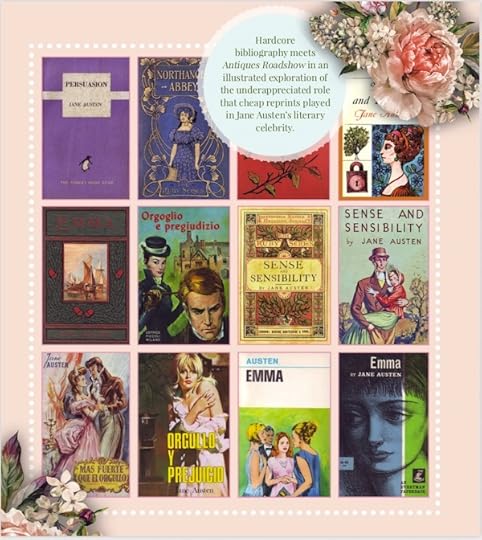

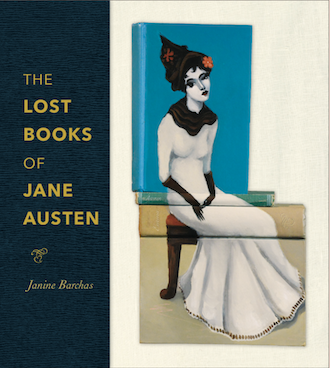

The Lost Books of Jane Austen by Janine Barchas (2019)

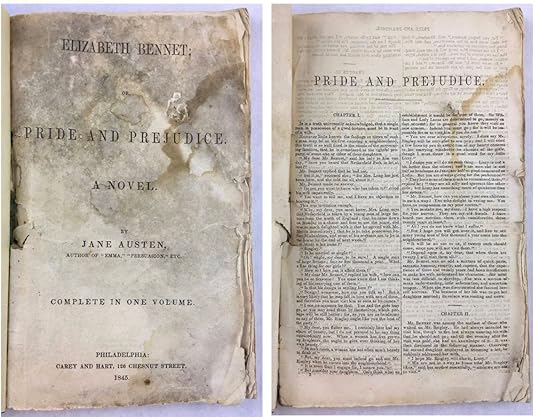

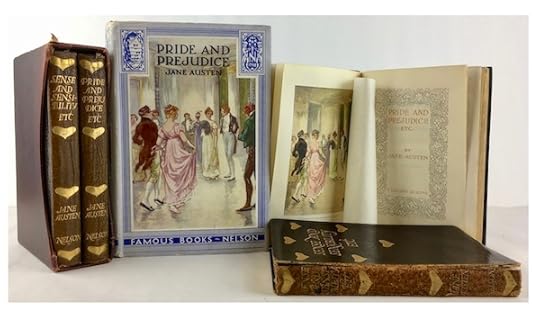

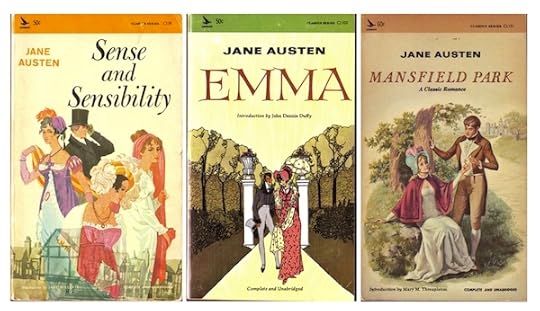

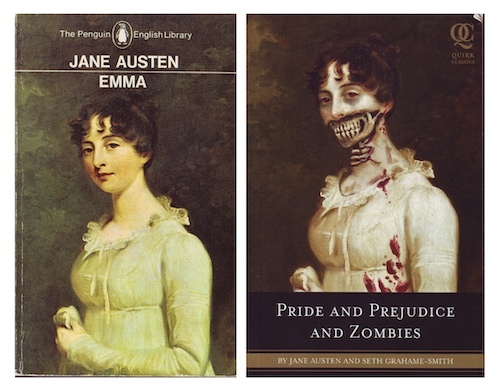

The Lost Books of Jane Austen by Janine Barchas (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019) is an ingenious, lavishly illustrated excursion through the printed history of Jane Austen’s books. Barchas contends that the cheap, sometimes shoddily produced printings of Austen’s novels helped keep her work affordable and in the public eye.

From the publisher: In the nineteenth century, inexpensive editions of Jane Austen’s novels targeted to Britain’s working classes were sold at railway stations, traded for soap wrappers, and awarded as school prizes.

At just pennies a copy, these reprints were some of the earliest mass-market paperbacks, with Austen’s beloved stories squeezed into tight columns on thin, cheap paper. Few of these hard-lived bargain books survive, yet they made a substantial difference to Austen’s early readership. These were the books bought and read by ordinary people.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Packed with nearly 100 full-color photographs of dazzling, sometimes gaudy, sometimes tasteless covers, The Lost Books of Jane Austen is a unique history of these rare and forgotten Austen volumes.

Such shoddy editions, Janine Barchas argues, were instrumental in bringing Austen’s work and reputation before the general public. Only by examining them can we grasp the chaotic range of Austen’s popular reach among working-class readers.

Informed by the author’s years of unconventional book hunting, The Lost Books of Jane Austen will surprise even the most ardent Janeite with glimpses of scruffy survivors that challenge the prevailing story of the author’s steady and genteel rise.

Thoroughly innovative and occasionally irreverent, this book will appeal in equal measure to book historians, Austen fans, and scholars of literary celebrity.

. . . . . . . . . .

Title page and opening text from 25-cent Elizabeth Bennet; or Pride and Prejudice (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1845)

At Christmas of 1905, the novels of Jane Austen sold as a boxed gift set of two leather-bound volumes with gilt hearts stamped on front covers and spines (London: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1903). The reprint of Pride and Prejudice in the Famous Books series is a reissue for a juvenile audience. This image shows two copies of the leather-bound sets, with one Pride and Prejudice open to show the matching frontispiece. Collection of Sandra Clark.

Airmont Classics paperbacks of Sense and Sensibility, Emma, and Mansfield Park (New York: Airmont, 1966–67). Author’s collection.

Sir William Beechey’s portrait of Marcia Fox, as it appears on the Penguin English Library edition of Emma (1966 to 1985) and on the 2009 Quirk Classic spoof Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. Author’s collection.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Lost Books of Jane Austen is available on Amazon*

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . .

Janine Barchas is the Louann and Larry Temple Centennial Professor of English Literature at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity and Graphic Design, Print Culture, and the Eighteenth-Century Novel. She is also the creator behind What Jane Saw.

Praise for The Lost Books of Jane Austen

“A major new work by Janine Barchas, an outstanding critic both of Jane Austen and of book history. The Lost Books of Jane Austen is cogent and persuasive.”—Peter Sabor, editor of The Cambridge Companion to Emma

“This ferociously researched book proves that a fresh set of methods can teach us something new about even this much-studied author.”—Leah Price, author of How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain

. . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy: Jane Austen Postage Stamps

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Lost Books of Jane Austen by Janine Barchas (2019) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 19, 2020

Johanna Spyri

Johanna Spyri (June 12, 1827 – July 7, 1901) born Johanna Louise Heusser, was a Swiss author best known for her first and most successful book, the 1881 children’s novel Heidi.

Born in rural Hirzel, not far from Zurich, she grew up in a happy, cultured home in a literary environment. Her mother, Meta Huesser, was a popular songwriter and poet. Her father was a well-known and greatly beloved physician in Zurich. The Huessers opened their home to the intellectual and literary figures of that time and place.

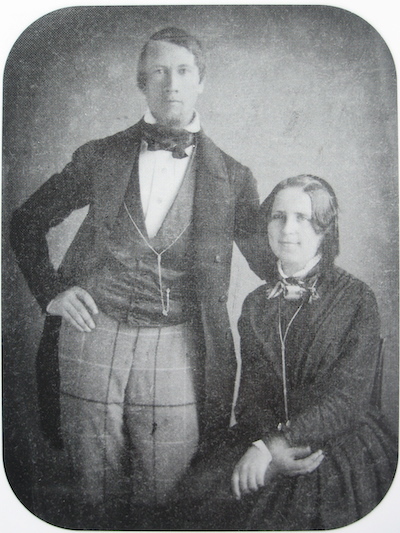

In 1852, when Johanna was 25, she married a former schoolmate, Bernhard Spyri, who became an attorney. While the couple was living in Zurich, she began to tell stories to their son to amuse him, and her husband encouraged her to set them to paper.

It would take many years before her work was published, however. Her first story, about a woman’s experience with domestic abuse, wasn’t published until 1880, when the author was already in her early fifties.

. . . . . . . .

Bernhard and Johanna Spyri when first married in 1852

. . . . . . . . . .

How Heidi came about

Heidi was published in its original German in 1881. Its original subtitled states that it is “a book for children and those who love children.”

Tragically, Spyri’s husband and their son both died in the same year, 1884. Spyri continued to write prolifically as well as to devote herself to charitable causes. None of the dozens of subsequent novels and stories she published came close to the success of Heidi, though that work alone was enough to make Johanna Spyri a national legend. It’s one of the bestselling books not only in Switzerland, but over the entire world.

Heidi has ranked with the Bible and Shakespeare as one of the world’s most widely read books. Translated into dozens of languages, tens of millions of copies have been printed.

In 1884, Heidi saw its first American publication, in a translation by Louise Brooks. As it was in its home country, it was an immediate bestseller, and has been beloved by generations since.

. . . . . . . . .

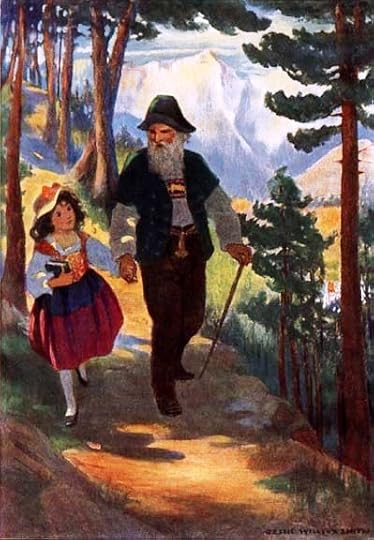

From the 1922 edition of Heidi, illustrated by Jessie Wilcox Smith

. . . . . . . . . . .

Heidi in brief

It’s hard to know what accounts for the universal popularity of Heidi. It’s a simple tale of an orphan girl (of course) who is left by her aunt Dete, who has been caring for her, with her crusty grandfather, a veritable hermit living in the Swiss Alps with a few goats.

Heidi wins him over (of course) and grows to love him, the mountains, and the little goat herd Peter, her only friend. After a time, Dete comes back for Heidi, over Grandfather’s objections, having secured a place for her as a companion to the disabled young daughter of a wealthy businessman.

Heidi grows attached to the girl, and vice versa, but can’t shake her homesickness. She is returned to Grandfather, and, after some turmoil, all is well that ends well. Read more about Heidi here.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

A national legend

Johanna Spyri is a legend in her home country of Switzerland. The Johanna Spyri Museum, dedicated to her life and work, is located not far from Zurich in Hirzel, where the author was born and grew up, states:

“It is not only Heidi’s world, but also that of her creator that you get to know in Zürich’s Hirzel. This is where the little Johanna Louise Heusser went to school. Since 1981 the Johanna Spyri Museum has been located in the Old School House.”

. . . . . . . . .

Johanna Spyri page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Subsequent Works

A surprising number of Spyri’s other works have been translated into English. One of the most popular, other than Heidi, is arguably Cornelli. You can find full texts of Spyri’s English translations on Project Gutenberg.

Other authors have traded in on the success of Heidi by writing sequels. Heidi Grows Up and Heidi’s Children were written by Charles Tritten in the 1930s. By then, Heidi as well as its translations were in the public domain.

In 2015, an English language edition titled The Complete Works of Johanna Spyri was published in a digital edition. It includes Heidi and eleven other works, so it’s actually not her complete oeuvre, but mainly those that have been translated. Still, it’s valuable to have access to more of Spyri’s works in translation.

In the Foreword, the editor of this edition states:

“Many writers have suffered injustice in being known as the author of but one book. Robinson Crusoe was not Defoe’s only masterpiece, nor did Bunyan confine his best powers to Pilgrim’s Progress … Such too has been the fate of Johanna Spyri, the Swiss authoress, whose reputation is mistakenly supposed to rest on the story of Heidi.

To be sure, Heidi is a book that in its field can hardly be overpraised. The winsome, kind-hearted little heroine in her mountain background is a figure to be remembered from childhood to old age. Nevertheless, Madame Spyri has shown here but one side of her narrative ability.”

. . . . . . . . .

The 2015 German language adaptation of Heidi is faithful to the book.

It’s available to stream on Amazon.*

. . . . . . . . . .

Film adaptations of Heidi

Heidi has also been adapted numerous times to the stage, including an opera, plus several movies and television series.

One of the most famous adaptations is the 1937 Shirley Temple film, which plays up on sentimentality, charming though it is. One of the most faithful adaptations is the 2015 German-language film, with a dark-haired Heidi as she was described in the book.

More about Johanna Spyri

Major Works (that have been translated into English)

Cornelli

Erick and Sally

Gritl’is Children

Heidi

Moni the Goat Boy, and Other Stories

Rico and Wiselli

Toni, the Little Woodcarver

Veronica

Vinzi (A Story of the Swiss Alps)

What Sami Sings with the Birds

More information

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Listen to Johanna Spyri’s works on Librivox

Johanna Spyri full text works on Project Gutenberg

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Johanna Spyri appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

“Patterns” by Amy Lowell — from Men, Women and Ghosts (1919)

“Patterns,” a poem by American imagist poet Amy Lowell (1874 – 1925, was published in Men, Women and Ghosts (1919). It exemplifies the imagery-dense free verse for which she was known.

Though Men, Women and Ghosts is a book of poems, Lowell begins her preface by writing that “This is a book of stories.” She goes on to say:

“For that reason I have excluded all purely lyrical poems. But the word ‘stories’ has been stretched to its fullest application. It includes both narrative poems, properly so called; tales divided into scenes; and a few pieces of less obvious storytelling import in which one might say that the dramatis personae are air, clouds, trees, houses, streets, and such like things.

It has long been a favorite idea of mine that the rhythms of vers libre have not been sufficiently plumbed, that there is in them a power of variation which has never yet been brought to the light of experiment.”

Read more of what Amy Lowell had to say about her vers libre poetry.

More about Amy Lowell

Patterns by Amy Lowell

I walk down the garden paths,

And all the daffodils

Are blowing, and the bright blue squills.

I walk down the patterned garden paths

In my stiff, brocaded gown.

With my powdered hair and jewelled fan,

I too am a rare

Pattern. As I wander down

The garden paths.

My dress is richly figured,

And the train

Makes a pink and silver stain

On the gravel, and the thrift

Of the borders.

Just a plate of current fashion,

Tripping by in high-heeled, ribboned shoes.

Not a softness anywhere about me,

Only whale-bone and brocade.

And I sink on a seat in the shade

Of a lime tree. For my passion

Wars against the stiff brocade.

The daffodils and squills

Flutter in the breeze

As they please.

And I weep;

For the lime tree is in blossom

And one small flower has dropped upon my bosom.

And the plashing of waterdrops

In the marble fountain

Comes down the garden paths.

The dripping never stops.

Underneath my stiffened gown

Is the softness of a woman bathing in a marble basin,

A basin in the midst of hedges grown

So thick, she cannot see her lover hiding,

But she guesses he is near,

And the sliding of the water

Seems the stroking of a dear

Hand upon her.

What is Summer in a fine brocaded gown!

I should like to see it lying in a heap upon the ground.

All the pink and silver crumpled up on the ground.

I would be the pink and silver as I ran along the paths,

And he would stumble after

Bewildered by my laughter.

I should see the sun flashing from his sword hilt and the buckles on his shoes.

I would choose

To lead him in a maze along the patterned paths,

A bright and laughing maze for my heavy-booted lover,

Till he caught me in the shade,

And the buttons of his waistcoat bruised my body as he clasped me,

Aching, melting, unafraid.

With the shadows of the leaves and the sundrops,

And the plopping of the waterdrops,

All about us in the open afternoon—

I am very like to swoon

With the weight of this brocade,

For the sun sifts through the shade.

Underneath the fallen blossom

In my bosom,

Is a letter I have hid.

It was brought to me this morning by a rider from the Duke.

“Madam, we regret to inform you that Lord Hartwell

Died in action Thursday sen’night.”

As I read it in the white, morning sunlight,

The letters squirmed like snakes.

“Any answer, Madam,” said my footman.

“No,” I told him.

“See that the messenger takes some refreshment.

No, no answer.”

And I walked into the garden,

Up and down the patterned paths,

In my stiff, correct brocade.

The blue and yellow flowers stood up proudly in the sun,

Each one.

I stood upright too,

Held rigid to the pattern

By the stiffness of my gown.

Up and down I walked,

Up and down.

In a month he would have been my husband.

In a month, here, underneath this lime,

We would have broke the pattern.

He for me, and I for him,

He as Colonel, I as Lady,

On this shady seat.

He had a whim

That sunlight carried blessing.

And I answered, “It shall be as you have said.”

Now he is dead.

In Summer and in Winter I shall walk

Up and down

The patterned garden paths

In my stiff, brocaded gown.

The squills and daffodils

Will give place to pillared roses, and to asters, and to snow.

I shall go

Up and down,

In my gown.

Gorgeously arrayed,

Boned and stayed.

And the softness of my body will be guarded from embrace

By each button, hook, and lace.

For the man who should loose me is dead,

Fighting with the Duke in Flanders,

In a pattern called a war.

Christ! What are patterns for?

. . . . . . . . . .

More poems (full texts) by Amy Lowell

The Cremona Violin

A Roxbury Garden

Lilacs

The post “Patterns” by Amy Lowell — from Men, Women and Ghosts (1919) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 18, 2020

“A Haunted House” by Virginia Woolf (full text)

“A Haunted House” by Virginia Woolf was published in her first collection of short fiction, Monday or Tuesday (1921). It later appeared as the lead story another collection of the authors stories, A Haunted House and Other Short Stories (1944), after Woolf’s death. Here we present the text in full.

First, here are a pair of analyses of this classic short story.

Interesting Literature: “‘A Haunted House’ by Virginia Woolf both is and is not a ghost story. In less than two pages of prose, Woolf explores, summons, and subverts the conventions of the ghost story, offering a modernist take on the genre … In summary, the narrator describes the house where she and her partner live. Whenever you wake in the house, you hear noises: a door shutting, and the sound of a ‘ghostly couple’ wandering from room to room in the house.”

Sitting Bee: “In ‘A Haunted House’ we have the themes of struggle, loss, commitment, connection, love, and acceptance … The story is narrated in the first person by an unnamed female narrator and after reading the story the reader realises that Woolf may be exploring the theme of struggle. Both the deceased man and woman are searching for something (love) yet they cannot find what they are looking for at the beginning of the story.”

From the Foreword by Leonard Woolf in A Haunted House and Other Short Stories:

Monday or Tuesday, the only book of short stories by Virginia Woolf which appeared in her lifetime, was published in 1921. It has been out of print for years.

All through her life, Virginia Woolf used at intervals to write short stories. It was her custom, whenever an idea for one occurred to her, to sketch it out in a very rough form and then to put it away in a drawer. Later, if an editor asked her for a short story, and she felt in the mood to write one (which was not frequent), she would take a sketch out of her drawer and rewrite it, sometimes a great many times.

Or if she felt, as she often did, while writing a novel that she required to rest her mind by working at something else for a time, she would either write a critical essay or work upon one of her sketches for short stories.

Finally, in 1940, she decided that she would get together a new volume of such stories and include in it most of the stories which had appeared originally in Monday or Tuesday, as well as some published subsequently in magazines and some unpublished. Our idea was that she should produce a volume of critical essays in 1941 and the volume of stories in 1942.

In the present volume I have tried to carry out her intention. I have included in it six out of the eight stories or sketches which originally appeared in Monday or Tuesday. The two omitted by me are “A Society,” and “Blue and Green.” I know that she had decided not to include the first and I am practically certain that she would not have included the second.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like reading the full texts of:

“Kew Gardens”

“Monday or Tuesday”

. . . . . . . . . .

A Haunted House by Virginia Woolf (1921)

Whatever hour you woke there was a door shutting. From room to room they went, hand in hand, lifting here, opening there, making sure—a ghostly couple.

“Here we left it,” she said. And he added, “Oh, but here too!” “It’s upstairs,” she murmured. “And in the garden,” he whispered “Quietly,” they said, “or we shall wake them.”

But it wasn’t that you woke us. Oh, no. “They’re looking for it; they’re drawing the curtain,” one might say, and so read on a page or two.

“Now they’ve found it,” one would be certain, stopping the pencil on the margin. And then, tired of reading, one might rise and see for oneself, the house all empty, the doors standing open, only the wood pigeons bubbling with content and the hum of the threshing machine sounding from the farm.

“What did I come in here for? What did I want to find?” My hands were empty. “Perhaps it’s upstairs then?” The apples were in the loft. And so down again, the garden still as ever, only the book had slipped into the grass.

But they had found it in the drawing room. Not that one could ever see them. The window panes reflected apples, reflected roses; all the leaves were green in the glass. If they moved in the drawing room, the apple only turned its yellow side.

Yet, the moment after, if the door was opened, spread about the floor, hung upon the walls, pendant from the ceiling—what? My hands were empty. The shadow of a thrush crossed the carpet; from the deepest wells of silence the wood pigeon drew its bubble of sound.

“Safe, safe, safe,” the pulse of the house beat softly. “The treasure buried; the room…” the pulse stopped short. Oh, was that the buried treasure?

A moment later the light had faded. Out in the garden then? But the trees spun darkness for a wandering beam of sun. So fine, so rare, coolly sunk beneath the surface the beam I sought always burnt behind the glass.

Death was the glass; death was between us; coming to the woman first, hundreds of years ago, leaving the house, sealing all the windows; the rooms were darkened. He left it, left her, went North, went East, saw the stars turned in the Southern sky; sought the house, found it dropped beneath the Downs. “Safe, safe, safe,” the pulse of the house beat gladly. “The Treasure yours.”

The wind roars up the avenue. Trees stoop and bend this way and that. Moonbeams splash and spill wildly in the rain. But the beam of the lamp falls straight from the window.

The candle burns stiff and still. Wandering through the house, opening the windows, whispering not to wake us, the ghostly couple seek their joy.

“Here we slept,” she says. And he adds, “Kisses without number.” “Waking in the morning—” “Silver between the trees —” “Upstairs—” “In the garden—” “When summer came—” “In winter snowtime—” The doors go shutting far in the distance, gently knocking like the pulse of a heart.

Nearer they come; cease at the doorway. The wind falls, the rain slides silver down the glass. Our eyes darken; we hear no steps beside us; we see no lady spread her ghostly cloak. His hands shield the lantern. “Look,” he breathes. “Sound asleep. Love upon their lips.”

Stooping, holding their silver lamp above us, long they look and deeply. Long they pause. The wind drives straightly; the flame stoops slightly. Wild beams of moonlight cross both floor and wall, and, meeting, stain the faces bent; the faces pondering; the faces that search the sleepers and seek their hidden joy.

“Safe, safe, safe,” the heart of the house beats proudly. “Long years—” he sighs. “Again you found me.” “Here,” she murmurs, “sleeping; in the garden reading; laughing, rolling apples in the loft. Here we left our treasure—”

Stooping, their light lifts the lids upon my eyes. “Safe! safe! safe!” the pulse of the house beats wildly. Waking, I cry “Oh, is this your buried treasure? The light in the heart.”

. . . . . . . . .

A Haunted House and Other Short Stories by Virginia Woolf on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Monday or Tuesday by Virginia Woolf

Listen online at Librivox

Monday or Tuesday at the British Library

Read the entire collection of Monday or Tuesday on Project Gutenberg

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post “A Haunted House” by Virginia Woolf (full text) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 17, 2020

“Kew Gardens” — a short story by Virginia Woolf

“Kew Gardens” is one of Virginia Woolf’s earliest short stories, written around 1917 and published in her first collection of stories, Monday or Tuesday (1921). It later appeared in another collection of the authors stories, A Haunted House and Other Short Stories (1944), after Woolf’s death.

“Kew Gardens” is titled after the famous gardens of London and takes place on a July day. It’s considered modernist, as it favors the capture of moments rather than revolving around a tight plot. Though it’s one of Woolf’s best known stories, and one of the most anthologized, it’s also one of her most elusive.

Here are a couple of excellent analyses of the story:

Sitting Bee: “In Kew Gardens by Virginia Woolf we have the theme of passion, desire, love, regret, paralysis, letting go, uncertainty, connection and humanity … there are sections that have the feel of stream of consciousness and after reading the story the reader realizes just how important the setting of the story is. The story is set in its entirety in the Royal Botanic Gardens situated in London.” Read more of this summary and analysis.

R.S. Martin: “In what may be the greatest of her short stories, Virginia Woolf creates a structured, encompassing view of existence, one which includes people’s thoughts and emotions, nature and human society, and even the movement of a random snail in a flower bed.” Read more of this summary and analysis.

. . . . . . . .

See also: “Monday or Tuesday” — a 1921 short story

. . . . . . . . .

A Foreword by Leonard Woolf

The original stories in Monday or Tuesday were later collected in A Haunted House and Other Short Stories. Monday or Tuesday was included along with the several other original stories: “A Haunted House,” “An Unwritten Novel,” “The String Quartet,” “Kew Gardens,” and “The Mark on the Wall.”

Mr. Woolf, as he explains here, omitted two of the original stories, “Blue & Green,” and “A society,” as he felt that would have been Virginia’s preference. Here is the Foreword by Leonard Woolf introducing this volume, which was published in the early 1944, after Virginia’s death.

Monday or Tuesday, the only book of short stories by Virginia Woolf which appeared in her lifetime, was published in 1921. It has been out of print for years.

All through her life, Virginia Woolf used at intervals to write short stories. It was her custom, whenever an idea for one occurred to her, to sketch it out in a very rough form and then to put it away in a drawer. Later, if an editor asked her for a short story, and she felt in the mood to write one (which was not frequent), she would take a sketch out of her drawer and rewrite it, sometimes a great many times.

Or if she felt, as she often did, while writing a novel that she required to rest her mind by working at something else for a time, she would either write a critical essay or work upon one of her sketches for short stories. For some time before her death we had often discussed the possibility of her republishing Monday or Tuesday, or publishing a new volume of collected short stories.

Finally, in 1940, she decided that she would get together a new volume of such stories and include in it most of the stories which had appeared originally in Monday or Tuesday, as well as some published subsequently in magazines and some unpublished. Our idea was that she should produce a volume of critical essays in 1941 and the volume of stories in 1942.

In the present volume I have tried to carry out her intention. I have included in it six out of the eight stories or sketches which originally appeared in Monday or Tuesday. The two omitted by me are “A Society,” and “Blue and Green.” I know that she had decided not to include the first and I am practically certain that she would not have included the second.

Kew Gardens (a short story by Virginia Woolf)

From the oval-shaped flower-bed there rose perhaps a hundred stalks spreading into heart-shaped or tongue-shaped leaves half way up and unfurling at the tip red or blue or yellow petals marked with spots of colour raised upon the surface; and from the red, blue or yellow gloom of the throat emerged a straight bar, rough with gold dust and slightly clubbed at the end.

The petals were voluminous enough to be stirred by the summer breeze, and when they moved, the red, blue and yellow lights passed one over the other, staining an inch of the brown earth beneath with a spot of the most intricate colour.

The light fell either upon the smooth, grey back of a pebble, or, the shell of a snail with its brown, circular veins, or falling into a raindrop, it expanded with such intensity of red, blue and yellow the thin walls of water that one expected them to burst and disappear.

Instead, the drop was left in a second silver grey once more, and the light now settled upon the flesh of a leaf, revealing the branching thread of fibre beneath the surface, and again it moved on and spread its illumination in the vast green spaces beneath the dome of the heart-shaped and tongue-shaped leaves.

Then the breeze stirred rather more briskly overhead and the colour was flashed into the air above, into the eyes of the men and women who walk in Kew Gardens in July.

The figures of these men and women straggled past the flower-bed with a curiously irregular movement not unlike that of the white and blue butterflies who crossed the turf in zig-zag flights from bed to bed.

The man was about six inches in front of the woman, strolling carelessly, while she bore on with greater purpose, only turning her head now and then to see that the children were not too far behind. The man kept this distance in front of the woman purposely, though perhaps unconsciously, for he wished to go on with his thoughts.

“Fifteen years ago I came here with Lily,” he thought. “We sat somewhere over there by a lake and I begged her to marry me all through the hot afternoon. How the dragonfly kept circling round us: how clearly I see the dragonfly and her shoe with the square silver buckle at the toe. All the time I spoke I saw her shoe and when it moved impatiently I knew without looking up what she was going to say: the whole of her seemed to be in her shoe. And my love, my desire, were in the dragonfly; for some reason I thought that if it settled there, on that leaf, the broad one with the red flower in the middle of it, if the dragonfly settled on the leaf she would say “Yes” at once. But the dragonfly went round and round: it never settled anywhere—of course not, happily not, or I shouldn’t be walking here with Eleanor and the children—Tell me, Eleanor. D’you ever think of the past?”

“Why do you ask, Simon?”

“Because I’ve been thinking of the past. I’ve been thinking of Lily, the woman I might have married…Well, why are you silent? Do you mind my thinking of the past?”

“Why should I mind, Simon? Doesn’t one always think of the past, in a garden with men and women lying under the trees? Aren’t they one’s past, all that remains of it, those men and women, those ghosts lying under the trees…one’s happiness, one’s reality?”

“For me, a square silver shoe buckle and a dragonfly—”

“For me, a kiss. Imagine six little girls sitting before their easels twenty years ago, down by the side of a lake, painting the water-lilies, the first red water-lilies I’d ever seen. And suddenly a kiss, there on the back of my neck. And my hand shook all the afternoon so that I couldn’t paint. I took out my watch and marked the hour when I would allow myself to think of the kiss for five minutes only—it was so precious—the kiss of an old grey-haired woman with a wart on her nose, the mother of all my kisses all my life. Come, Caroline, come, Hubert.”

They walked on the past the flower-bed, now walking four abreast, and soon diminished in size among the trees and looked half transparent as the sunlight and shade swam over their backs in large trembling irregular patches.

In the oval flower bed the snail, whose shelled had been stained red, blue, and yellow for the space of two minutes or so, now appeared to be moving very slightly in its shell, and next began to labour over the crumbs of loose earth which broke away and rolled down as it passed over them.

It appeared to have a definite goal in front of it, differing in this respect from the singular high stepping angular green insect who attempted to cross in front of it, and waited for a second with its antenna trembling as if in deliberation, and then stepped off as rapidly and strangely in the opposite direction.

Brown cliffs with deep green lakes in the hollows, flat, blade-like trees that waved from root to tip, round boulders of grey stone, vast crumpled surfaces of a thin crackling texture—all these objects lay across the snail’s progress between one stalk and another to his goal.

Before he had decided whether to circumvent the arched tent of a dead leaf or to breast it there came past the bed the feet of other human beings.

This time they were both men. The younger of the two wore an expression of perhaps unnatural calm; he raised his eyes and fixed them very steadily in front of him while his companion spoke, and directly his companion had done speaking he looked on the ground again and sometimes opened his lips only after a long pause and sometimes did not open them at all.

The elder man had a curiously uneven and shaky method of walking, jerking his hand forward and throwing up his head abruptly, rather in the manner of an impatient carriage horse tired of waiting outside a house; but in the man these gestures were irresolute and pointless.

He talked almost incessantly; he smiled to himself and again began to talk, as if the smile had been an answer. He was talking about spirits—the spirits of the dead, who, according to him, were even now telling him all sorts of odd things about their experiences in Heaven.

“Heaven was known to the ancients as Thessaly, William, and now, with this war, the spirit matter is rolling between the hills like thunder.” He paused, seemed to listen, smiled, jerked his head and continued:——

“You have a small electric battery and a piece of rubber to insulate the wire—isolate?—insulate?—well, we’ll skip the details, no good going into details that wouldn’t be understood—and in short the little machine stands in any convenient position by the head of the bed, we will say, on a neat mahogany stand. All arrangements being properly fixed by workmen under my direction, the widow applies her ear and summons the spirit by sign as agreed. Women! Widows! Women in black——”

Here he seemed to have caught sight of a woman’s dress in the distance, which in the shade looked a purple black. He took off his hat, placed his hand upon his heart, and hurried towards her muttering and gesticulating feverishly.

But William caught him by the sleeve and touched a flower with the tip of his walking-stick in order to divert the old man’s attention. After looking at it for a moment in some confusion the old man bent his ear to it and seemed to answer a voice speaking from it, for he began talking about the forests of Uruguay which he had visited hundreds of years ago in company with the most beautiful young woman in Europe.

He could be heard murmuring about forests of Uruguay blanketed with the wax petals of tropical roses, nightingales, sea beaches, mermaids, and women drowned at sea, as he suffered himself to be moved on by William, upon whose face the look of stoical patience grew slowly deeper and deeper.

Following his steps so closely as to be slightly puzzled by his gestures came two elderly women of the lower middle class, one stout and ponderous, the other rosy cheeked and nimble.

Like most people of their station they were frankly fascinated by any signs of eccentricity betokening a disordered brain, especially in the well-to-do; but they were too far off to be certain whether the gestures were merely eccentric or genuinely mad.

After they had scrutinised the old man’s back in silence for a moment and given each other a queer, sly look, they went on energetically piecing together their very complicated dialogue:

“Nell, Bert, Lot, Cess, Phil, Pa, he says, I says, she says, I says, I says, I says——”

“My Bert, Sis, Bill, Grandad, the old man, sugar, Sugar, flour, kippers, greens, Sugar, sugar, sugar.”

The ponderous woman looked through the pattern of falling words at the flowers standing cool, firm, and upright in the earth, with a curious expression.

She saw them as a sleeper waking from a heavy sleep sees a brass candlestick reflecting the light in an unfamiliar way, and closes his eyes and opens them, and seeing the brass candlestick again, finally starts broad awake and stares at the candlestick with all his powers. So the heavy woman came to a standstill opposite the oval-shaped flower bed, and ceased even to pretend to listen to what the other woman was saying.

She stood there letting the words fall over her, swaying the top part of her body slowly backwards and forwards, looking at the flowers. Then she suggested that they should find a seat and have their tea.

The snail had now considered every possible method of reaching his goal without going round the dead leaf or climbing over it. Let alone the effort needed for climbing a leaf, he was doubtful whether the thin texture which vibrated with such an alarming crackle when touched even by the tip of his horns would bear his weight; and this determined him finally to creep beneath it, for there was a point where the leaf curved high enough from the ground to admit him.

He had just inserted his head in the opening and was taking stock of the high brown roof and was getting used to the cool brown light when two other people came past outside on the turf. This time they were both young, a young man and a young woman.

They were both in the prime of youth, or even in that season which precedes the prime of youth, the season before the smooth pink folds of the flower have burst their gummy case, when the wings of the butterfly, though fully grown, are motionless in the sun.

“Lucky it isn’t Friday,” he observed.

“Why? D’you believe in luck?”

“They make you pay sixpence on Friday.”

“What’s sixpence anyway? Isn’t it worth sixpence?”

“What’s ‘it’—what do you mean by ‘it’?”

“O, anything—I mean—you know what I mean.”

Long pauses came between each of these remarks; they were uttered in toneless and monotonous voices. The couple stood still on the edge of the flower bed, and together pressed the end of her parasol deep down into the soft earth.

The action and the fact that his hand rested on the top of hers expressed their feelings in a strange way, as these short insignificant words also expressed something, words with short wings for their heavy body of meaning, inadequate to carry them far and thus alighting awkwardly upon the very common objects that surrounded them, and were to their inexperienced touch so massive; but who knows (so they thought as they pressed the parasol into the earth) what precipices aren’t concealed in them, or what slopes of ice don’t shine in the sun on the other side?

Who knows? Who has ever seen this before? Even when she wondered what sort of tea they gave you at Kew, he felt that something loomed up behind her words, and stood vast and solid behind them; and the mist very slowly rose and uncovered—O, Heavens, what were those shapes?—little white tables, and waitresses who looked first at her and then at him; and there was a bill that he would pay with a real two shilling piece, and it was real, all real, he assured himself, fingering the coin in his pocket, real to everyone except to him and to her; even to him it began to seem real; and then—but it was too exciting to stand and think any longer, and he pulled the parasol out of the earth with a jerk and was impatient to find the place where one had tea with other people, like other people.

“Come along, Trissie; it’s time we had our tea.”

“Wherever does one have one’s tea?” she asked with the oddest thrill of excitement in her voice, looking vaguely round and letting herself be drawn on down the grass path, trailing her parasol, turning her head this way and that way, forgetting her tea, wishing to go down there and then down there, remembering orchids and cranes among wild flowers, a Chinese pagoda and a crimson crested bird; but he bore her on.

Thus one couple after another with much the same irregular and aimless movement passed the flower-bed and were enveloped in layer after layer of green blue vapour, in which at first their bodies had substance and a dash of colour, but later both substance and colour dissolved in the green-blue atmosphere.

How hot it was! So hot that even the thrush chose to hop, like a mechanical bird, in the shadow of the flowers, with long pauses between one movement and the next; instead of rambling vaguely the white butterflies danced one above another, making with their white shifting flakes the outline of a shattered marble column above the tallest flowers the glass roofs of the palm house shone as if a whole market full of shiny green umbrellas had opened in the sun; and in the drone of the aeroplane the voice of the summer sky murmured its fierce soul.

Yellow and black, pink and snow white, shapes of all these colours, men, women, and children were spotted for a second upon the horizon, and then, seeing the breadth of yellow that lay upon the grass, they wavered and sought shade beneath the trees, dissolving like drops of water in the yellow and green atmosphere, staining it faintly with red and blue.

It seemed as if all gross and heavy bodies had sunk down in the heat motionless and lay huddled upon the ground, but their voices went wavering from them as if they were flames lolling from the thick waxen bodies of candles.

Voices. Yes, voices. Wordless voices, breaking the silence suddenly with such depth of contentment, such passion of desire, or, in the voices of children, such freshness of surprise; breaking the silence?

But there was no silence; all the time the motor omnibuses were turning their wheels and changing their gear; like a vast nest of Chinese boxes all of wrought steel turning ceaselessly one within another the city murmured; on the top of which the voices cried aloud and the petals of myriads of flowers flashed their colours into the air.

More about Monday or Tuesday by Virginia Woolf

Listen online at Librivox

Monday or Tuesday at the British Library

Read the entire collection of Monday or Tuesday on Project Gutenberg

The post “Kew Gardens” — a short story by Virginia Woolf appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 15, 2020

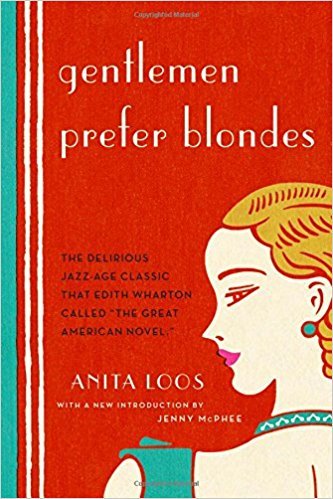

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes by Anita Loos (1925) — A Jazz Age Classic

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes by Anita Loos, subtitled The Intimate Diary or a Professional Lady, published in 1925, popularized the unfortunate tropes of “dumb blonde” and ruthless gold-digger in the character of Lorelei Lee.

We accompany the unflappable flapper around New York and Europe, where she dallies with the affections of hapless men. Maybe she’s not so dumb after all.

Anita Loos (1889 – 1991, who was by the time of the book’s publication already a successful screenwriter, claimed that the book’s inspiration came from a real-life incident.

On a train, her efforts to haul around her large luggage were ignored by her male fellow passengers (Loos was a tiny brunette). Yet when a blonde dropped her book, the men around her fell all over themselves in a competition to retrieve it for her.

She used the incident as the jumping-off point for a series of sketches about a gold-digging blonde flapper from Little Rock who came to be called Lorelei Lee. These were published in Harper’s Bazaar magazine as “The Lorelei stories.”

. . . . . . . . .

More about Anita Loos

. . . . . . . . . . .

The satiric stories that subtly skewered sex tropes were such a hit that the magazine’s circulation quadrupled within a short time. The stories were soon collected into the novel Gentleman Prefer Blondes, published in 1925, and which is arguably the most enduring work by Anita Loos. It was the second bestselling novel of 1926, having captured the carefree spirit of the Jazz Age.

Was Lorelei Lee a feel-good flapper exemplifying the roaring twenties, or a scheming “professional lady,” as the subtitle implies? Likely, a bit of both. The rank of “professional” refers to the gold-digging, and not, as the term has often been used, to refer to prostitution per se.

Despite the light tone of the book, it was well-received by critics and devoured by the public. Edith Wharton deemed it “The Great American Novel,” though that distinction hasn’t endured. While Gentlemen Prefer Blondes can be deemed a classic, its stature as a great work of literature would be questioned today.

In 1927, hot on the heels of the book’s success, a sequel was published, titled But Gentlemen Marry Brunettes. Take that, Blondes!

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

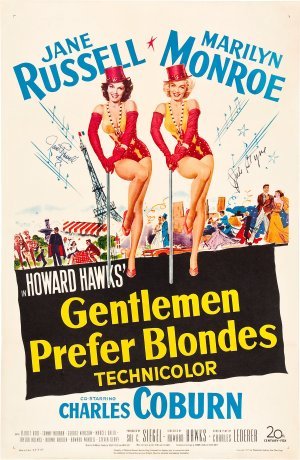

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was first made into a 1928 silent film, for which Loos co-wrote the screenplay. However, there are no copies in existence, and it is considered a lost film. The 1949 Broadway adaptation of the novel became a musical starring Carol Channing. The story has continued to return to the stage in several renamed versions for decades to come.

The best-known adaptation of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is the 1953 film starring Jane Russell and Marilyn Monroe as two best friends who work as American showgirls. Based on the 1949 stage play, Monroe, as Lorelei Lee, made the song “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend” an iconic standard. The story and premise depart fairly substantially from the original 1925 novel, but this film is considered a movie musical classic.

A contemporary edition

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes continues to stay in print. From the 2014 Liveright edition:

“This delirious 1925 Jazz Age classic introduced readers to Lorelei Lee, the small-town girl from Little Rock, who has become one of the most timeless characters in American fiction. Outrageous and charming, this not-so-dumb blonde has been portrayed on stage and screen by Carol Channing and Marilyn Monroe and has become the archetype of the footloose, good-hearted gold digger (not that she sees herself that way).

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes follows Lorelei as she entertains suitors across Europe before returning home to marry a millionaire. In this delightfully droll and witty book, Lorelei’s glamorous pragmatism shines, as does Anita Loos’s mastery of irony and dialect. A craze in its day and with ageless appeal, this new Liveright edition puts Lorelei back where she belongs: front and center.”

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes by Anita Loos on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . . .

A 1925 review: Introducing the professional gold digger

From The Davenport Daily Times, December 1925: The beautiful and successful gold digger is not a new type in fiction but Anita Loos is the first one to our knowledge to write the diary of a professional lady of this sort.

Her heroine may never have heard of Plato or middle distance or Chopin or the Nobel awards or the Locarno treaty, but she knew her oil, as the slang phrase has it, when it came to the pleasant art of extorting gifts of jewelry or money from wealthy men.

In one chapter she gets herself engaged with the mental reservation that if she can’t really stick it out, she will go on such an orgy of extravagance fit her fiancé’s expense that the only decent thing for him to do will be to break the match. Then her way will be clear to a profitable breach of promise suit.

But a gentleman gold digger of whom she is enamored persuades her to go through with the marriage so that friend husband will finance the production of some scenario he has written, and our little heroine serenely closes her diary with the reflection that everything is as right as can be in the rightest of possible worlds.

She has a convenient husband who is hardly astute enough to be suspicious, she has ample money to buy all the jewelry she wants, and she has in the gentleman gold digger a friend who can satisfy her craving for mental stimulation.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The original cover of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

. . . . . . . . . . .

Another 1925 review: “A Topsy of literature”

From the Salt Lake Telegram, November 15, 1925: Anita Loos already famous in her way. but even so, we hardly expected a book of subtle humor from her pen such as is found in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

Characterized as The Intimate Diary of a Professional Lady, it resolves itself into a book that is crammed full of chuckles. You may object to the methods of a charming gold-digger, or you may marvel at the void of the dumbbell. And you may object to some scattered risqué remarks.

But in spite of it all, you’re bound to be amused, for her leading character the author has created an intriguing gold digger, dumb and beautiful. What a smooth worker she is. Here we have her in all her glory, in a sidesplitting, astonishingly frank diary that takes her from New York to London, Paris, Vienna, and Munich in quest of art education In the foreign colleges known as the Ritz hotels.

Diplomats, princes, society, big business, and men—sho plays them all, especially men, men, men. Tiaras. state secrets, titles, and Poirlett models all fall into her pretty little net.

With the intimate drawings by Ralph Barton, this book, its characters, and its sardonic insight will become part of our tradition of humor alongside the Benchleys. Stewarts and Lardners of our period.

A precocious pen

Perhaps it’s heredity. Anita Loos’s father was humorist—and a theatrical producer. At age five she was on the stage. At thirteen she was an authoress. and at the same time was writing scenarios for David Griffith.

When Griffith, two years later, saw the child in pigtails and sailor suit who was writing his roughest comedies for him, he nearly collapsed. Since then she has outlined the moods and motions for many an eminent screen star; and she has come to know far more about “professionals” than it is wise perhaps for anyone to know.

On her last trip to California, to while away the dull passages of a four-day train journey she wrote the first chapter of this book. Harper’s Bazaar, which took the first, called for more.

And so the book “growed up,” a Topsy of literature which is certain to make a definite mark in American Literature.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Gentlemen Prefer Blondes by Anita Loos (1925) — A Jazz Age Classic appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 13, 2020

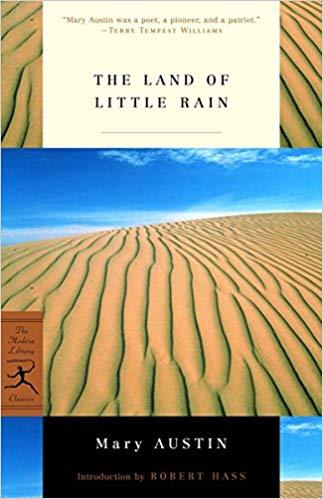

The Land of Little Rain by Mary Hunter Austin (1903)

Mary Hunter Austin (1868 – 1934) is no longer widely read, but during her lifetime, she traveled in vaunted literary circles. The Land of Little Rain (1903), a nonfiction compilation of connected essays, is her best-remembered work. From the publisher:

“The enduring appeal of the desert is strikingly portrayed in this poetic study, which has become a classic of the American Southwest. First published in 1903, it is the work of Mary Austin, a prolific novelist, poet, critic, and playwright, who was also an ardent early feminist and champion of Indians and Spanish-Americans.

She is best known today for this enchanting paean to the vast, arid, yet remarkably beautiful lands that lie east of the Sierra Nevadas, stretching south from Yosemite through Death Valley to the Mojave Desert.

Comprising fourteen sketches, the book describes plants, animals, mountains, birds, skies, Indians, prospectors, towns, and other aspects of the desert in serene, beautifully modulated prose that conveys the timeless cycles of life and death in a harsh land.

Readers will never again think of the desert as a lifeless, barren environment but rather as a place of rare, austere beauty, rich in plant and animal life, weaving a lasting spell over its human inhabitants.”

As a novelist and essayist, Austin focused her writing on cultural and social problems within the Native American community. In addition to spending seventeen years making a special study of Indian life in the Mojave Desert, Austin was defended the rights of Native Americans and Spanish Americans.

For many years, she and her husband lived in various towns in California’s Owens Valley, where Austin’s love for the desert and the Native Americans who lived there began to grow. This led to the creation of her first published book, The Land of Little Rain (1903), a tribute to California’s deserts.

. . . . . . . . .

More about Mary Hunter Austin

. . . . . . . . . . .

It’s always fascinating to discover original reviews of somewhat forgotten books, and it appears that The Land of Little Rain received its share of praise when first published. Here is one such review from 1903:

A 1903 review of Land of Little Rain

From the original review in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 7, 1903: On the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, where the slopes drop steeply to the desert stretches, beyond independence, and reaching eastward and southward, ever the eastern borders of that portion of California, is the country which Mary Hunter Austin describes so graphically in her book, The Land of Little Rain.

Wonderfully appropriate to the country is that name. Indeed, it is a land of “little rain.” Desert is the name which the tourist, accustomed to moister areas, gives to it, and when it’s remembered that the stark Death Valley, with its wastes of sand and alkali lies within its borders, its seems well named.

A vivid descriptions of “the country of three seasons”

“Desert is the name it wears upon the maps,” says Austin, “but the Indian’s is the better name.” Another term is the “Country of Lost Borders,” for the land and not the law sets its limits. Note Austin’s description:

“This is the nature of that country. There are hills, rounded, blunt, burned, squeezed up out of chaos, chrome, and vermillion painted, aspiring to the snow line. Between the hills lie high, level-looking plains full of intolerable sun glare, or narrow valleys drowned in a blue haze. The hill surface is streaked with ash drift and the black, unweathered lava flows.

After rains, water accumulates in the hollows of the closed valleys, and, evaporating, leaves hard, dry levels of pure desertness that get the local name of dry lakes. Where the mountains are steep and the rains heavy the pool is never quite dry, but dark and bitter, rimmed about with the efflorescence of alkaline deposits.

A thin crust of it lies along the marsh over the vegetating area, which has neither beauty nor freshness. In the broad wastes, open to the wind, the sand drifts its hummocks about he stubby shrubs and between them the soil shows saline traces. The sculpture of the hills here is more wind than water work, though the quick storms do sometimes scar them past many a year’s redeeming.

Since this is a hill country, one expects to find springs, but not to depend on them, for when found they are often brackish and unwholesome, or maddening slow dribbles in a thirsty soil. Here you find the hot sink of the Death Valley, or high rolling districts were the air has always a tang of frost.

Here are the long, heavy winds and breathless calms on the tilted mesas where the dust devils dance, whirling up into a wide, pale sky. Here you have no rain when all the earth cried for it, or quick downpours, called cloudbursts for violence. A land of local rivers, with little in it to love; yet a land that, once visited, must be come back to inevitably. If it were not so there would be little told of it.

This is the country of three seasons. From June on to November it lies hot, still and unbearable, sick with violent unbelieving storms, then on until April — chill, quiescent, drinking its scant rain and scantier snows; from April to the hot season again, blossoming, radiant, and seductive. These months are only approximate: later of earlier the rain-laden wind may drift up the water gate of the Colorado from the Gulf, and the land sets its seasons by the rain.”