Nava Atlas's Blog, page 49

November 1, 2020

The Literary Love Story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning

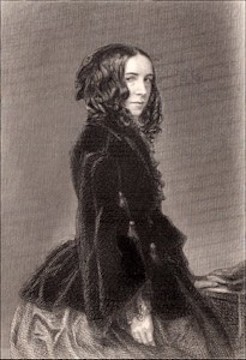

While Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning are both remembered and revered for their contributions to English literature and poetry, their love story is also celebrated.

The tale of their courtship and marriage is a real-life Victorian romance that includes love letters, elopement, and the Italian adventure of a lifetime.

About Elizabeth Barrett

Elizabeth Barrett was born in 1806 and enjoyed a happy childhood growing up in a country house in Worcestershire. When she was fifteen, she developed a serious illness that may have been related to a spinal injury, and had lingering health issues throughout her life, possibly as a result.

Her love poems, including Sonnets from the Portuguese and Aurora Leigh, are the best know among her body of highly respected work. Here is a brief biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

. . . . . . . . . . .

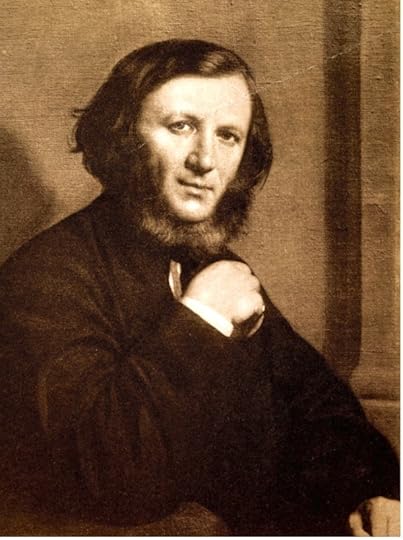

Robert Browning

. . . . . . . . . . .

About Robert Browning

Robert Browning was born in London in 1812. He attended the University of London for one semester and lived with his parents until he was in his mid-30s. In addition to several long poems, most of his plays were written during this early period of his life.

His early works were published with funding from his family. Today, he is particularly renowned for his dramatic monologues and talent for depicting characters in his works.

Letters of Admiration and Love

In 1844, Elizabeth’s second collection of poems was published and warmly received. The work included lines that praised Robert Browning. After reading the poems, Robert wrote a letter of thanks to Elizabeth on January 10, 1845, with the tantalizing line, “I love your verses with all my heart … and I love you, too.”

Their correspondence ensued until they met for the first time in the summer of 1845. Over the next several months, they became ever closer. Elizabeth remarked that she and Robert were “growing to be the truest of friends.” According to her, Robert’s best qualities were fortitude, integrity, and courage in adversity. In all, their courtship went on for twenty months, during which time they exchanged five hundred seventy-five letters.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Secrets

Elizabeth’s and Robert’s courtship was kept hidden from Elizabeth’s overbearing father, and Robert’s parents had concerns about whether Elizabeth’s frail health made her a suitable match for Robert. Elizabeth’s doctors suggested that she move to Italy for health reasons, but her father refused to allow her to go. This refusal led the couple to take decisive action.

On September 12, 1846, they were secretly married at Marylebone Church. Elizabeth’s father wasn’t told, and she continued to live at the family home for a week after the wedding. Then, Elizabeth and Robert moved to Pisa, Italy to begin their life together.

When Elizabeth’s father eventually learned of his daughter’s marriage to Robert, he disowned his her, refusing to see her or open her letters to him. Fortunately, after some time had passed, most of Elizabeth’s family accepted her marriage to Robert.

. . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and son Robert Wiedemann Barrett Browning, 1860

. . . . . . . . .

Life in Italy

After spending time in Pisa, Elizabeth and Robert settled in Florence, where they lived at Casa Guidi. Elizabeth’s health greatly improved, and the two poets composed what would later become some of their most well-respected and widely known works. Their son, Robert, was born in Florence in 1849.

Important Works

Robert and Elizabeth were inspired by their surroundings in Italy, and Elizabeth wrote a significant amount of poetry while living there. Her most famous work, Sonnets from the Portuguese, was a collection of love poems that she wrote in the first few years of her marriage to Robert. The sonnet that begins with her most famous line, “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways,” is part of this collection.

After she shared the sonnets with him, he remarked that they were “the finest sonnets written in any language since Shakespeare’s.”

Italy plays a prominent role in many of Robert and Elizabeth’s most memorable works from this period. Elizabeth was particularly interested in Italian politics, and she supported the unification of Italy. In “Casa Guidi Windows,” written in 1851, she describes hearing a child singing a song about liberty on the street outside her apartment. Scholars believe that the poem was intended to increase sympathy for the people of Florence.

Robert’s works from this period were inspired by the history of the Italian Renaissance. For example, “Fra Lippo Lippi,” now considered one of his finest monologues, discusses the life of the title character, a Florentine painter during the Renaissance. This monologue was published in 1855 as part of Browning’s Men and Women, a collection that also included “A Toccata of Galuppi’s” and “Love Among the Ruins.”

Compared with Elizabeth, Robert wrote relatively little during their marriage. Men and Women didn’t have a very favorable reception, which was disappointing to him. Instead of writing, he tended to spend more time sketching or making clay models during the day.

Casa Guidi, where the Brownings lived in Florence

Photo: Italy Magazine

Sadness

After many happy years together at Casa Guidi, Elizabeth became seriously ill in the summer of 1861. She passed away in Robert’s arms on June 29, 1861. According to Robert, Elizabeth’s last word was “beautiful.”

Robert returned to London with their son in the autumn of that year. Overcome with grief, he spent most of his time alone, and he worked on preparing Elizabeth’s final work, Last Poems, for publication.

. . . . . . . . .

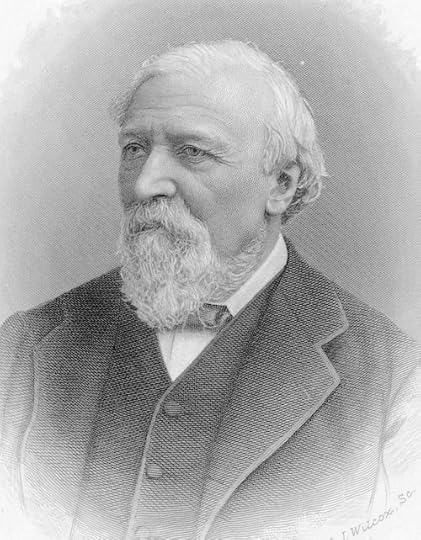

Robert Browning in his later years

. . . . . . . . .

Aftermath

Gradually, Robert returned to writing, publishing The Ring and the Book in 1868 and 1869. The work was immediately received with enthusiasm, and it established Robert’s reputation as a top literary figure of the era.

In his later years, he wrote works of incredible fluency. Many of these were dramatic poems or narrative poems that focused on contemporary issues or classical material. Some of his most enduring works from this period include “Prince Hohenstiel-Schwangau,” “Red Cotton Night-Cap Country,” “Balaustion’s Adventure” and “Dramatic Idyls.”

Although he lived in London after Elizabeth’s death, Robert returned to Italy often. On a trip to Venice in 1889, he passed away after developing complications from a cold. Robert Browning was buried at Westminster Abbey in London.

Legacy

In addition to being celebrated for their literary talents, Elizabeth and Robert are remembered as people who were deeply in love. As Sir Frederic Kenyon wrote, Elizabeth and Robert “gave the most beautiful example of [love] in their own lives.” The marriage of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning required courage and sacrifice, and they were willing to do whatever it took to build a beautiful life together.

. . . . . . . . .

Quotes by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

. . . . . . . . .

Sources

Robert Browning

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Love and the Brownings

Fra Lippo Lippi

A Florentine Reformation: The Brownings at Casa Guidi

The post The Literary Love Story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 27, 2020

11 Poems by Angelina Weld Grimké on Love, Longing, & Race

Angelina Weld Grimké (1880 – 1958) was an American playwright, poet, and educator best known for being a figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. Following is a selection of poems by Angelina Weld Grimké on love, race, nature, and other subjects that preoccupied her.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Grimké was part of a family of biracial civil rights activists, and in earlier generations, abolitionists. Her father served some time as the Vice-President of the NAACP. Her great-aunts (including the similarly named Angelina Grimké Weld) were well-known abolitionists and advocates for women’s rights in the 19th century. They were significant influences for Grimké’s use of literature as a propagandist tool.

With a mixed-race father and white mother, Grimké was 75% white, but she identified as Black. After her parents separated when she was a child, she was raised by her father in Boston, where she attended school. As a woman of color, she was deeply invested in issues affecting the African-American community.

After completing her studies, she moved to Washington D.C. where she began connecting with fellow poet Georgia Douglas Johnson. Shortly after, she wrote her first articles and poems about racism and the black experience in America. After her father’s death, which devastated her, she moved to New York City where she lived fairly reclusively until her death.

In Afro-American Women Writers (1988), Ann Allen Shockley wrote of Grimké’s poetic work:

As a poet, she became a familiar contributor to magazines and anthologies of the Harlem Renaissance. Sixteen of her poems appeared in Countee Cullen’s classic Caroling Dusk. They were also featured in the pages of The Crisis and Opportunity magazines, although none was collected for publication. The poems were conventional verses on nature, love, life, and death. She was considered an imagist poet in the mode of the “old lapidaries,” who wrote from her own private emotions about what she felt and saw in a sensitive, poignant, and beautiful way.

Gloria T. Hull, who exhumed Grimké from near literary oblivion, said of her work: “Grimké’s poetry is very delicate, musical, romantic, and pensive. It draws extensively on the natural world for allusions and figures of speech.” Hull found some of her unpublished poetry lesbian in nature. Of this, she wrote: “Most of these lyrics either chronicle a romance which is now dead or record a cruel and unrequited love.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Black Finger

I have just seen a beautiful thing

Slim and still,

Against a gold, gold sky,

A straight cypress,

Sensitive

Exquisite,

A black finger

Pointing upwards.

Why, beautiful, still finger are you black?

And why are you pointing upwards?

. . . . . . . . . .

At April

Toss your gay heads,

Brown girl trees;

Toss your gay lovely heads;

Shake your brown slim bodies;

Stretch your brown slim arms;

Stretch your brown slim toes.

Who knows better than we,

With the dark, dark bodies,

What it means

When April comes a-laughing and a-weeping

Once again

At our hearts?

. . . . . . . . . .

Trees

God made them very beautiful, the trees:

He spoke and gnarled of bole or silken sleek

They grew; majestic bowed or very meek;

Huge-bodied, slim; sedate and full of glees.

And He had pleasure deep in all of these.

And to them soft and little tongues to speak

Of Him to us, He gave wherefore they seek

From dawn to dawn to bring unto our knees.

Yet here amid the wistful sounds of leaves,

A black-hued gruesome something swings and swings;

Laughter it knew and joy in little things

Till man’s hate ended all. -And so man weaves.

And God, how slow, how very slow weaves He-

Was Christ Himself not nailed to a tree?

. . . . . . . . . .

A Winter Twilight

A silence slipping around like death,

Yet chased by a whisper, a sigh,

a breath; One group of trees, lean,

naked and cold,

Inking their cress ‘gainst a

sky green-gold;

One path that knows where the

corn flowers were;

Lonely, apart, unyielding, one fir;

And over it softly leaning down,

One star that I loved ere the

fields went brown

. . . . . . . . . .

Tenebris

There is a tree, by day,

That, at night, Has a shadow,

A hand huge and black,

With fingers long and black.

All through the dark,

Against the white man’s house,

In the little wind,

The black hand plucks and plucks

At the bricks.

The bricks are the color of blood

and very small.

Is it a black hand,

Or is it a shadow?

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The Eyes Of My Regret

Always at dusk, the same tearless experience,

The same dragging of feet up the same well-worn path

To the same well-worn rock;

The same crimson or gold dropping away of the sun

The same tints, – rose, saffron, violet, lavender, grey

Meeting, mingling, mixing mistily;

Before me the same blue black cedar rising jaggedly to

a point;

Over it, the same slow unlidding of twin stars,

Two eyes, unfathomable, soul-searing,

Watching, watching, watching me;

The same two eyes that draw me forth, against my will

dusk after dusk;

The same two eyes that keep me sitting late into the

night, chin on knees

Keep me there lonely, rigid, tearless, numbly

miserable –

The eyes of my Regret.

. . . . . . . . . .

Death

When the lights blur out for thee and me,

And the black comes in with a sweep,

I wonder — will it mean life again,

Or sleep?

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also like:

12 Women Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Puppet-Player

Sometimes it seems as though some puppet-player

A clenched claw cupping a craggy chin,

Sits just beyond the border of our seeing,

Twitching the strings with slow, sardonic grin.

. . . . . . . . . .

Vigil

You will come back, sometime, somehow;

But if it will be bright or black

I cannot tell; I only know

You will come back.

Does not the spring with fragrant pack

Return unto the orchard bough?

Do not the birds retrace their track?

All things return. Some day the glow

Of quick’ning dreams will pierce your lack;

And when you know I wait as now

You will come back.

. . . . . . . . . .

Hushed by the Hands Of Sleep

Hushed by the hands of Sleep,

By the beautiful hands of Sleep.

Very gentle and quiet he lies,

With a little smile of sweet surprise,

Just softly hushed at lips and eyes,

Hushed by the hands of Sleep,

By the beautiful hands of Sleep.

Hushed by the hands of Sleep,

By the beautiful hands of Sleep.

Death leaned down as his eyes grew dim,

But oh! it was beautiful to him.

Hushed by the hands of Sleep,

By the beautiful hands of Sleep.

. . . . . . . . . .

For the Candle-Light

The sky was blue, so blue that day

And each daisy white, so white,

O, I knew that no more could rains fall grey

And night again be night . . . . .

I knew, I knew. Well, if night is night,

And the grey skies greyly cry.

I have in a book for the candle light,

A daisy dead and dry.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Angelina Weld Grimké

See more of her poetic work at Academy of American Poets

. . . . . . . . . .

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

The post 11 Poems by Angelina Weld Grimké on Love, Longing, & Race appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 23, 2020

10 Classic Latina Poets to Discover and Read

There are so many more classic Latina poets to discover (or rediscover) than is possible to list in one post. But for those just getting acquainted with this area of Spanish literature, you’ll find a good starting point here. Shown at right, Rosario Castellanos.

Presented here is a sampling of poets whose works have been fairly extensively translated into English, or whose achievements in their home countries were significant. The Latina poets listed following represent Cuba, Puerto Rico, a number of South American countries, Mexico, and Spain.

. . . . . . . . . .

Delmira Agustini

Delmira Agustini (1886 – 1914) was a Uruguayan poet born in the country’s capital, Montevideo. Her first book of poetry was published when she was still in her teens. Many of Agustini’s poems dealt frankly with female sexuality, sensuality, and passion at a time when writing openly about such subjects was taboo.

Agustini’s life ended tragically when her estranged husband murdered her. She was only 28, and yet had already achieved much in the field of poetry.

Major works included El libro blanco (1907; The White Book), Cantos de la mañana (1910; Morning Songs), Los cálices vacíos (1913; Empty Chalices). Posthumous collections include El rosarío del Eros (1924; Eros’ Rosary), and Obras completas (1924; Complete Works). A selection of her poems, mainly in Spanish, can be found here, with commentary in English.

. . . . . . . . .

Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda

Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda (1814 – 1873) was born in Puerto Principe, Cuba, and made her name as one of the great romantic poets and playwrights of the 19th century. Avellaneda’s timeless style and romantic vision combined with her experiences of personal suffering, resulting in some of the most heart-rending literature in the Spanish language.

A woman whose love life was as prolific as her pen, she wove her experiences into her varied works. For her earliest poems, she used the pseudonym of “La Peregrina” (The Pilgrim). Her first collection, Poesías líricas (“Lyrical Poems”) was published in 1841, and she continued to write and publish for the next several decades. Here is a selection of her poems in English translation.

. . . . . . . . . .

Julia de Burgos

Julia de Burgos (1914 – 1953), was a Puerto Rican poet and activist. She was also an advocate for Puerto Rican independence and served as Secretary General of the Daughters of Freedom, the women’s branch of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party.

When Burgos left Puerto Rico at the age of twenty-five, she vowed never to return. Though she kept her promise, her poetry invoked the social issues and the national identity of Puerto Rico.

The island’s history, including colonialism, slavery, and oppression were woven into her poems. She also wrote of her personal struggles and complicated love life. Read more about Julia de Burgos and sample 6 poems about love and identity in both English and Spanish.

. . . . . . . . . .

Rosario Castellanos

Rosario Castellanos (1925 – 1974), author, poet, and diplomat, was one of Mexico’s most influential literary voices of the twentieth century. https://www.literaryladiesguide.com/a...

Her work dealt with issues of culture and gender in her home country and went on to influence contemporary Mexican feminist theory and cultural studies. Personal and cultural identity and the spirit of her home state of Chiapas are among the themes in her poetry. Her deep religious faith was also a theme in her poetic work.

Read a sampling of poems by Rosario Castellanos in English and Spanish.

. . . . . . . . .

Nydia Lamarque

Nydia Lamarque (1906–1982) was an Argentine poet, activist, and translator, as well as a trained attorney. She was involved with the country’s feminist and socialist movements.

Lamarque translated the work of prominent French poets including Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Racine, and others into Spanish. Her own first collection of poetry, Telarañas, was published in 1925, and she continued to produce collections through 1951 with her final book, Echeverría el Poeta.

Finding Lamarque’s poetry online is a challenge, though there’s a selection of her poetry in its original Spanish here.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gabriela Mistral

Gabriela Mistral (1889 – 1957) was a Chilean poet, educator, diplomat, and feminist. She was the first Latin American to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature (1945). The prize was awarded to her “for her lyric poetry which, inspired by powerful emotions, has made her name a symbol of the idealistic aspirations of the entire Latin American world.”

She said of her own need to write: “I write poetry because I can’t disobey the impulse; it would be like blocking a spring that surges up in my throat. For a long time I’ve been the servant of the song that comes, that appears and can’t be buried away.”

Sample nine poems by Gabriela Mistral about life, love, and death, in their original Spanish and in English translation.

. . . . . . . . .

Rafaela Chacón Nardi

Rafaela Chacón Nardi was a Cuban poet and educator born in Havana, Cuba. In addition to her writing activities, she was a professor who taught at Escuela Normal para Maestros, Universidad de La Habana, and Universidad Las Villas.

In 1948 she published Journey to the Dream, her first volume of poetry. The work was reprinted in 1957 and included a letter that Chilean poet and Nobel Laureate Gabriela Mistral wrote in praise of Nardi’s work.

Though she authored more than 30 books including several volumes of poetry, very little of her work has been translated into English. However, if your Spanish is good, you can read a lovely selection of her poetry here.

. . . . . . . . . .

Mercedes Negron Muñoz

Mercedes Negron Muñoz (1895 – 1973) was a Puerto Rican poet, feminist, and essayist who was recognized as one of the most important postmodern writers of the island nation’s 20th-century writers.

Born in Barranquitas, Puerto Rico, Muñoz grew up in a family steeped in culture and politics. She emigrated to the U.S. in 1918, then returned to Puerto in 1932. In 1937 her first collection of poems were published, establishing herself as “Clara Lair” the pseudonym she would use going forward. Themes in her highly awarded work included themes of love, feminism, existentialism, and a touch of eroticism.

Like some of the others listed here, her work has rarely been translated, but here’s a small sampling of her poems in Spanish.

. . . . . . . . .

Excilia Saldaña

Excilia Saldaña (1946 – 1999) was a poet, children’s book author, and academic. Born in Havana, she identified as Afro-Cuban. Though she was an esteemed and much-awarded Cuban cultural figure, during her lifetime, her work was mainly confined to a Cuban audience, and rarely translated.

This changed in 2002 with the publication of In the Vortex of the Cyclone: Selected Poems by Excilia Saldaña: A Bilingual Edition. The publisher wrote of it that “The collection emphasizes her construction of a personal and poetic autobiography to reveal the identity of one of the best Afro-Caribbean poets of the twentieth century.”

It’s exceedingly rare to find Saldaña’s poetry in translation (or even in its original Spanish, for that matter) online, so the best resource continues to be the In the Vortex of the Cyclone.

. . . . . . . . . . .

María Elena Walsh

María Elena Walsh (1930 – 2011) was an Argentine poet, novelist, playwright, and musician. She was widely known for books and songs for children and used her work to express her political beliefs. In the era of the Argentine military dictatorship (1976 – 1983), her song, “Oración a la Justicia” was adopted as a civil rights anthem. She was a staunch feminist and lived with her female partner until her death at age 80.

Born in Buenos Aires, Walsh was partly of Irish descent. She had her first poem published at age 15 and from then on, devoted her career to creating poetry and lyrics for readers and listeners of all ages. This multitalented artist deserves wider recognition. Here’s a small sampling of Walsh’s poems translated into English.

. . . . . . . . . .

Find more in

10 Classic Cuban Women Authors to Discover

The post 10 Classic Latina Poets to Discover and Read appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 16, 2020

12 Essential Works of Classic Feminist Fiction

Here are 12 essential works of classic feminist fiction — according to Literary Ladies’ Guide. Some of the books listed were considered daring (and sometimes shocking) in their time. Because of the courage and foresight of their creators, women writers today are freer to speak their truths — and to see them in print — than the authors highlighted in the list following.

These timeless classics have proven foundational for contemporary feminist novels. From Jane Eyre (1847), Charlotte Brontë’s gothic romance, through Octavia Butler’s Afro-futurist Parable of the Talents (1998), the books listed here feature heroines who continue to inspire and surprise.

. . . . . . . . . .

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847)

Jane Eyre (1847), Charlotte Brontë’s best-known novel, is the story of a young woman of humble means and lonely upbringing who searches for love and a sense of belonging while preserving her independence. The book sparked a fair amount of controversy when first published, which was fueled by critics and the public suspecting that “Currer Bell” (the author’s ambiguous pseudonym) was a woman.

An avowedly feminist work, Jane Eyre also fits into the genre of gothic novel due to that pesky little detail of Mr. Rochester’s mad wife locked away in an attic. Jane’s strength, integrity, and determination to make her own way in the world has spoken to generations of readers.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë (1848)

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall was published under Anne Brontë’s pseudonym, Acton Bell. Like her older sister Charlotte’s Jane Eyre, it’s now considered among the earliest of feminist novels.

The novel’s heroine, Helen Graham, fled her abusive husband, lived on her own with her young son, and was making a living as an artist. Taken together, these circumstances were considered shocking at the time. Yet The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, more so than Anne’s quieter first novel, Agnes Grey (1847), was an immediate success despite its unflinching look at the harms of alcoholism and abuse that arose from it.

. . . . . . . . . .

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (1868)

Louisa May Alcott expert Susan Bailey writes in How Louisa May Alcott’s Feminism Explains Her Timelessness, “It’s the simple and subtle messages inherent in her writing to children that continue to stand the test of time. Just about every woman pioneer since Louisa’s era remembers reading Little Women and they point to Jo March as a pivotal inspiration.”

The story of four sisters and their beloved Marmee who draw strength from one another has proven timeless — with adaptations for the large and small screen appearing regularly. In addition to her literary pursuits, Louisa was also known for promoting women’s rights and campaigning for women’s suffrage. She allowed her feminist views to come through in the dialog between her characters, which is one of the great pleasures of reading Little Women and her other works.

. . . . . . . . .

The Awakening by Kate Chopin (1899)

The Awakening by Kate Chopin, an 1899 novella telling the story of a young mother who undergoes a dramatic period of change as she “awakens” to the restrictions of her traditional societal role and her full potential as a woman. Many times, we find Edna Pontellier awake in situations that signify more metaphorical awakenings to new knowledge and sensual experience.

Consequently, Chopin’s work came under immediate attack when published and was banned from bookstores and libraries. The author died virtually forgotten, yet The Awakening has been rediscovered and holds a secure and prominent position as a watershed text in U.S. literature and feminist studies.

. . . . . . . . .

My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin (1901)

My Brilliant Career (1901) was Australian author Miles Franklin‘s first novel, written while still in her teens and published in her twenty-first year.

Sybilla Melvyn is a high-strung, imaginative girl from the Australian countryside. Convinced that she’s ugly and useless, Sybilla is surprised when a wealthy young man proposes marriage. What ensues is a slow-moving yet thoroughly satisfying coming-of-age novel that’s decades ahead of its time.

While this book rarely appears on lists of top classic feminist novels, it should — and its staunchly feminist author deserves to be better known outside her native land. There’s a scene in which Sybilla bloodies a harasser that speaks to today’s #MeToo movement, with a satisfying vengeance!

. . . . . . . . . .

O Pioneers! by Willa Cather (1913)

O Pioneers! by Willa Cather is one of this esteemed American author’s most iconic novels. One of her earliest full-length works, it was published in 1913. Written in the kind of spare, lyric prose, the book explores ideas of community, family ties, destiny, and chance, this is a prime example of overlooked classic feminist fiction.

When Alexandra Bergson’s father is near death, he puts her in charge of the prairie farmland he loved deeply. The father trusted his daughter, not his sons, to carry out his life’s work in taming an unforgiving land. Even as a fictional device, this was a radical notion in 1913. Alexandra proves more than equal to the task, infusing the narrative with values of compassion and dignity.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1915)

Herland is a utopian novel by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Three American men are exploring an unknown continent, and in the course of their travels, they hear of a land where only women, female children, and babies live. It’s rumored that it’s a place where men might dare to enter, but never seem to come out.

Reaching the aptly named “Herland,” the three men are captured and imprisoned. The female leaders don’t wish to harm them, but rather to study them, so that the two cultures (and genders) can learn from one another. We join the men on this journey with them as the narrator describes their interactions with the women, the land, and how each of them navigates and adjusts to their surroundings.

A bit clumsily written, Herland is nevertheless an ahead-of-its-time piece of speculative fiction that was followed by two sequels to form a trilogy.

. . . . . . . . .

Their Eyes Were Watching God

by Zora Neale Hurston (1937)

Their Eyes Were Watching God is arguably Zora Neale Hurston‘s best-known work, and one that has become an acknowledged feminist classic.

Janie, the story’s heroine, searches for a sense of identity, independence, love, and happiness over the course of twenty-five years and several relationships. Janie’s story has a few echoes of Zora’s own, especially the early portion, though it could be argued that the author never found true happiness when it came to love.

Critic Mary Helen Washington wrote of Zora’s masterpiece: “In 1937 came the novel in which Hurston triumphed in the art of taking the imagery, imagination, and experiences of Black folk and making literature.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Pavilion of Women by Pearl S. Buck (1946)

Pavilion of Women by Pearl S. Buck tells the story of the spiritual and intellectual awakening of Madame Wu, a pampered wife of the wealthy House of Wu. On her fortieth birthday, she announces to her husband that she wishes to withdraw from their physical life as a couple.

Madame Wu beseeches her husband to take a second wife to serve him as a concubine. She feels that this is his due as the patriarch of one of the China’s oldest and most prestigious households, and over his objections, carries out the arrangement herself. She then withdraws to her private rooms to read books and live a life of the mind, something she never had the luxury to do as a wife and mother. With another woman in the household, complications ensue, of course.

Pavilion of Women, an exquisitely told story of a woman coming into her own in a patriarchal society, is a gem to savor. Pearl S. Buck isn’t often listed in compilations of feminist authors and their works, which is curious, as she was a staunch promoter of equality for women.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing (1962)

Doris Lessing, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2007, is considered one of the premier authors of fiction and nonfiction of the second wave feminist era. The Golden Notebook might just be her most iconic book, one of introspective feminism that challenged the prevailing notion of women’s roles midcentury society.

A 1962 review stated, “The Golden Notebook is far and away her most ambitious work to date — a long and complex novel which draws on all the talents and insights of this gifted woman …The publisher compares its heroine, Anna, with the ‘new woman’ of Ibsen and Shaw … unquestionably The Golden Notebook is going to be debated and analyzed by students of the novel for a long time to come.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Parable of the Sower (1993) &

Parable of the Talents by Octavia E. Butler (1998)

When Octavia E. Butler‘s Parable of Sower (1993) begins, Lauren Olamina is a young Black woman just emerging from her teens, navigating the apocalyptic world of Los Angeles in the 2020s. A fight — and flight — for survival leads to her create a new faith called Earthseed, in hopes of repairing the world.

Lauren is once again at the center of Parable of the Talents, still fighting to salvage humanity. Now, she’s battling violent bigots and religious fanatics. Now a mother, her daughter Larkin (also called Asha Vere) becomes part of the narrative.

As richly imagined amalgams of dystopian literature and science fiction, the Parable novels feature the social commentary and prescience that Butler was known for. And Lauren emerges as a feminist symbol of courage and leadership that the real world could use now.

. . . . . . . . . .

Honorable Mentions

This list began with Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, featuring a young woman struggling to save herself, and ends with Lauren Olamina, whose task it is to save humanity in Octavia E. Butler’s Parable novels.

In lists of feminist classics, we often find The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (1963/1971), The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys (1966).

These books highlight the devastating effects of patriarchy on women who suffer from mental illness. It could actually be argued that it’s the patriarchy that exacerbates mental illness. While these are all great stories that I personally love and highly recommend, their heroines, at least in my mind, are driven to victimhood than emerging as feminist heroines.

Other books that occasionally pop up in the realm of feminist fiction by more recently deceased authors include The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter, Dancing at the Edge by Ursula K. Le Guin, and The Women’s Room by Marilyn French.

It would be pretty overwhelming to list all the feminist-inclined authors and poets in this site’s list of biographies and on the wish list — that would cover most of them, honestly!

Here are a few lists of essential contemporary classic feminist literature, some mixing fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and plays:

Feminist Literature

40 New Feminist Classics You Should Read

40 of the Best Feminist Books

The post 12 Essential Works of Classic Feminist Fiction appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 14, 2020

Miss Brill by Katherine Mansfield (1920) — full text

“Miss Brill” by Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923) is a much-anthologized short story by this New Zealand-born author considered a master of the genre. It was first published in The Garden Party and Other Stories in 1920.

Miss Brill is an elderly woman who has created her own illusory world.Some of the themes in this classic short story include loneliness, aging, and alienation. It’s considered a modernist piece and is replete with symbolism rather than plot.

Here is some supplementary information on Miss Brill:

General analysis here and here

Plot summary here and here

The story’s conflict

Symbolism in the story

Here is the entire text of The Garden Party and Other Stories by Katherine Mansfield (1920), the original source of “Miss Brill.”

The paragraphs in the original full text of this short story, following, have been broken up for readability. This short story is in the public domain.

. . . . . . . . .

Miss Brill by Katherine Mansfield

Although it was so brilliantly fine—the blue sky powdered with gold and great spots of light like white wine splashed over the Jardins Publiques—Miss Brill was glad that she had decided on her fur. The air was motionless, but when you opened your mouth there was just a faint chill, like a chill from a glass of iced water before you sip, and now and again a leaf came drifting—from nowhere, from the sky.

Miss Brill put up her hand and touched her fur. Dear little thing! It was nice to feel it again. She had taken it out of its box that afternoon, shaken out the moth-powder, given it a good brush, and rubbed the life back into the dim little eyes.

“What has been happening to me?” said the sad little eyes. Oh, how sweet it was to see them snap at her again from the red eiderdown!… But the nose, which was of some black composition, wasn’t at all firm. It must have had a knock, somehow. Never mind—a little dab of black sealing-wax when the time came—when it was absolutely necessary…. Little rogue!

Yes, she really felt like that about it. Little rogue biting its tail just by her left ear. She could have taken it off and laid it on her lap and stroked it. She felt a tingling in her hands and arms, but that came from walking, she supposed. And when she breathed, something light and sad—no, not sad, exactly—something gentle seemed to move in her bosom.

There were a number of people out this afternoon, far more than last Sunday. And the band sounded louder and gayer. That was because the Season had begun. For although the band played all the year round on Sundays, out of season it was never the same.

It was like some one playing with only the family to listen; it didn’t care how it played if there weren’t any strangers present. Wasn’t the conductor wearing a new coat, too? She was sure it was new. He scraped with his foot and flapped his arms like a rooster about to crow, and the bandsmen sitting in the green rotunda blew out their cheeks and glared at the music.

Now there came a little “flutey” bit—very pretty!—a little chain of bright drops. She was sure it would be repeated. It was; she lifted her head and smiled.

Only two people shared her “special” seat: a fine old man in a velvet coat, his hands clasped over a huge carved walking-stick, and a big old woman, sitting upright, with a roll of knitting on her embroidered apron. They did not speak. This was disappointing, for Miss Brill always looked forward to the conversation. She had become really quite expert, she thought, at listening as though she didn’t listen, at sitting in other people’s lives just for a minute while they talked round her.

She glanced, sideways, at the old couple. Perhaps they would go soon. Last Sunday, too, hadn’t been as interesting as usual. An Englishman and his wife, he wearing a dreadful Panama hat and she button boots.

And she’d gone on the whole time about how she ought to wear spectacles; she knew she needed them; but that it was no good getting any; they’d be sure to break and they’d never keep on. And he’d been so patient. He’d suggested everything—gold rims, the kind that curved round your ears, little pads inside the bridge. No, nothing would please her. “They’ll always be sliding down my nose!” Miss Brill had wanted to shake her.

The old people sat on the bench, still as statues. Never mind, there was always the crowd to watch. To and fro, in front of the flower-beds and the band rotunda, the couples and groups paraded, stopped to talk, to greet, to buy a handful of flowers from the old beggar who had his tray fixed to the railings.

Little children ran among them, swooping and laughing; little boys with big white silk bows under their chins, little girls, little French dolls, dressed up in velvet and lace. And sometimes a tiny staggerer came suddenly rocking into the open from under the trees, stopped, stared, as suddenly sat down “flop,” until its small high-stepping mother, like a young hen, rushed scolding to its rescue.

Other people sat on the benches and green chairs, but they were nearly always the same, Sunday after Sunday, and—Miss Brill had often noticed—there was something funny about nearly all of them. They were odd, silent, nearly all old, and from the way they stared they looked as though they’d just come from dark little rooms or even—even cupboards!

Behind the rotunda the slender trees with yellow leaves down drooping, and through them just a line of sea, and beyond the blue sky with gold-veined clouds.

Tum-tum-tum tiddle-um! tiddle-um! tum tiddley-um tum ta! blew the band.

Two young girls in red came by and two young soldiers in blue met them, and they laughed and paired and went off arm-in-arm. Two peasant women with funny straw hats passed, gravely, leading beautiful smoke-coloured donkeys. A cold, pale nun hurried by. A beautiful woman came along and dropped her bunch of violets, and a little boy ran after to hand them to her, and she took them and threw them away as if they’d been poisoned. Dear me!

Miss Brill didn’t know whether to admire that or not! And now an ermine toque and a gentleman in grey met just in front of her. He was tall, stiff, dignified, and she was wearing the ermine toque she’d bought when her hair was yellow. Now everything, her hair, her face, even her eyes, was the same colour as the shabby ermine, and her hand, in its cleaned glove, lifted to dab her lips, was a tiny yellowish paw.

Oh, she was so pleased to see him—delighted! She rather thought they were going to meet that afternoon. She described where she’d been—everywhere, here, there, along by the sea. The day was so charming—didn’t he agree? And wouldn’t he, perhaps?…

But he shook his head, lighted a cigarette, slowly breathed a great deep puff into her face, and even while she was still talking and laughing, flicked the match away and walked on. The ermine toque was alone; she smiled more brightly than ever. But even the band seemed to know what she was feeling and played more softly, played tenderly, and the drum beat, “The Brute! The Brute!” over and over.

What would she do? What was going to happen now? But as Miss Brill wondered, the ermine toque turned, raised her hand as though she’d seen some one else, much nicer, just over there, and pattered away. And the band changed again and played more quickly, more gayly than ever, and the old couple on Miss Brill’s seat got up and marched away, and such a funny old man with long whiskers hobbled along in time to the music and was nearly knocked over by four girls walking abreast.

Oh, how fascinating it was! How she enjoyed it! How she loved sitting here, watching it all! It was like a play. It was exactly like a play. Who could believe the sky at the back wasn’t painted? But it wasn’t till a little brown dog trotted on solemn and then slowly trotted off, like a little “theatre” dog, a little dog that had been drugged, that Miss Brill discovered what it was that made it so exciting.

They were all on the stage. They weren’t only the audience, not only looking on; they were acting. Even she had a part and came every Sunday. No doubt somebody would have noticed if she hadn’t been there; she was part of the performance after all. How strange she’d never thought of it like that before!

And yet it explained why she made such a point of starting from home at just the same time each week—so as not to be late for the performance—and it also explained why she had quite a queer, shy feeling at telling her English pupils how she spent her Sunday afternoons.

No wonder! Miss Brill nearly laughed out loud. She was on the stage. She thought of the old invalid gentleman to whom she read the newspaper four afternoons a week while he slept in the garden. She had got quite used to the frail head on the cotton pillow, the hollowed eyes, the open mouth and the high pinched nose.

If he’d been dead she mightn’t have noticed for weeks; she wouldn’t have minded. But suddenly he knew he was having the paper read to him by an actress! “An actress!” The old head lifted; two points of light quivered in the old eyes. “An actress—are ye?” And Miss Brill smoothed the newspaper as though it were the manuscript of her part and said gently; “Yes, I have been an actress for a long time.”

The band had been having a rest. Now they started again. And what they played was warm, sunny, yet there was just a faint chill—a something, what was it?—not sadness—no, not sadness—a something that made you want to sing. The tune lifted, lifted, the light shone; and it seemed to Miss Brill that in another moment all of them, all the whole company, would begin singing.

The young ones, the laughing ones who were moving together, they would begin, and the men’s voices, very resolute and brave, would join them. And then she too, she too, and the others on the benches—they would come in with a kind of accompaniment—something low, that scarcely rose or fell, something so beautiful—moving…. And Miss Brill’s eyes filled with tears and she looked smiling at all the other members of the company. Yes, we understand, we understand, she thought—though what they understood she didn’t know.

Just at that moment a boy and girl came and sat down where the old couple had been. They were beautifully dressed; they were in love. The hero and heroine, of course, just arrived from his father’s yacht. And still soundlessly singing, still with that trembling smile, Miss Brill prepared to listen.

“No, not now,” said the girl. “Not here, I can’t.”

“But why? Because of that stupid old thing at the end there?” asked the boy. “Why does she come here at all—who wants her? Why doesn’t she keep her silly old mug at home?”

“It’s her fu-fur which is so funny,” giggled the girl. “It’s exactly like a fried whiting.”

“Ah, be off with you!” said the boy in an angry whisper. Then: “Tell me, ma petite chère—”

“No, not here,” said the girl. “Not yet.”

On her way home she usually bought a slice of honey-cake at the baker’s. It was her Sunday treat. Sometimes there was an almond in her slice, sometimes not. It made a great difference. If there was an almond it was like carrying home a tiny present—a surprise—something that might very well not have been there. She hurried on the almond Sundays and struck the match for the kettle in quite a dashing way.

But to-day she passed the baker’s by, climbed the stairs, went into the little dark room—her room like a cupboard—and sat down on the red eiderdown. She sat there for a long time. The box that the fur came out of was on the bed. She unclasped the necklet quickly; quickly, without looking, laid it inside. But when she put the lid on she thought she heard something crying.

. . . . . . . . .

More full texts of short stories by Katherine Mansfield on this site

“The Garden Party” (1920)

“Bliss” (1918)

The post Miss Brill by Katherine Mansfield (1920) — full text appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 10, 2020

A Few Figs from Thistles by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1921)

Presented here is the full text of A Few Figs from Thistles: Poems and Sonnets by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892 – 1950). A Few Figs from Thistles was her second collection, published in 1921.

As a poet, Millay is considered as a major twentieth-century figure in the genre. Wildly popular, and actually famous as a poet in her lifetime, she’s no longer as widely read and studied, though still well regarded in the field of poetry.

The poetry in this collection explored love and female sexuality, among other themes. In the poems, including the oft-quoted “First Fig,” Millay both celebrates and satirizes herself.

Here are a few reviews, analyses, and commentaries on Millay’s inaugural published work, which is in the public domain:

Analysis on JStor

Bolstered by Thoughts

What’s Up with the Title?

Another Night of Reading

. . . . . . . . .

See also: 12 Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

. . . . . . . . .

A Few Figs from Thistles (1921) – full text

First Fig

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

. . . . . . . . .

Second Fig

Safe upon the solid rock the ugly houses stand:

Come and see my shining palace built upon the sand!

. . . . . . . . .

Recuerdo

We were very tired, we were very merry—

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

It was bare and bright, and smelled like a stable—

But we looked into a fire, we leaned across a table,

We lay on a hill-top underneath the moon;

And the whistles kept blowing, and the dawn came soon.

We were very tired, we were very merry—

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry;

And you ate an apple, and I ate a pear,

From a dozen of each we had bought somewhere;

And the sky went wan, and the wind came cold,

And the sun rose dripping, a bucketful of gold.

We were very tired, we were very merry,

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

We hailed, “Good morrow, mother!” to a shawl-covered head,

And bought a morning paper, which neither of us read;

And she wept, “God bless you!” for the apples and pears,

And we gave her all our money but our subway fares.

. . . . . . . . .

Thursday

And if I loved you Wednesday,

Well, what is that to you?

I do not love you Thursday—

So much is true.

And why you come complaining

Is more than I can see.

I loved you Wednesday,—yes—but what

Is that to me?

. . . . . . . . .

To the Not Impossible Him

How shall I know, unless I go

To Cairo and Cathay,

Whether or not this blessed spot

Is blest in every way?

Now it may be, the flower for me

Is this beneath my nose;

How shall I tell, unless I smell

The Carthaginian rose?

The fabric of my faithful love

No power shall dim or ravel

Whilst I stay here,—but oh, my dear,

If I should ever travel!

. . . . . . . . .

Macdougal Street

As I went walking up and down to take the evening air,

(Sweet to meet upon the street, why must I be so shy?)

I saw him lay his hand upon her torn black hair;

(“Little dirty Latin child, let the lady by!”)

The women squatting on the stoops were slovenly and fat,

(Lay me out in organdie, lay me out in lawn!)

And everywhere I stepped there was a baby or a cat;

(Lord God in Heaven, will it never be dawn?)

The fruit-carts and clam-carts were ribald as a fair,

(Pink nets and wet shells trodden under heel)

She had haggled from the fruit-man of his rotting ware;

(I shall never get to sleep, the way I feel!)

He walked like a king through the filth and the clutter,

(Sweet to meet upon the street, why did you glance me by?)

But he caught the quaint Italian quip she flung him from the gutter;

(What can there be to cry about that I should lie and cry?)

He laid his darling hand upon her little black head,

(I wish I were a ragged child with ear-rings in my ears!)

And he said she was a baggage to have said what she had said;

(Truly I shall be ill unless I stop these tears!)

. . . . . . . . .

The Singing-Woman from the Wood’s Edge

What should I be but a prophet and a liar,

Whose mother was a leprechaun, whose father was a friar?

Teethed on a crucifix and cradled under water,

What should I be but the fiend’s god-daughter?

And who should be my playmates but the adder and the frog,

That was got beneath a furze-bush and born in a bog?

And what should be my singing, that was christened at an altar,

But Aves and Credos and Psalms out of the Psalter?

You will see such webs on the wet grass, maybe,

As a pixie-mother weaves for her baby,

You will find such flame at the wave’s weedy ebb

As flashes in the meshes of a mer-mother’s web,

But there comes to birth no common spawn

From the love of a priest for a leprechaun,

And you never have seen and you never will see

Such things as the things that swaddled me!

After all’s said and after all’s done,

What should I be but a harlot and a nun?

In through the bushes, on any foggy day,

My Da would come a-swishing of the drops away,

With a prayer for my death and a groan for my birth,

A-mumbling of his beads for all that he was worth.

And there’d sit my Ma, with her knees beneath her chin,

A-looking in his face and a-drinking of it in,

And a-marking in the moss some funny little saying

That would mean just the opposite of all that he was praying!

He taught me the holy-talk of Vesper and of Matin,

He heard me my Greek and he heard me my Latin,

He blessed me and crossed me to keep my soul from evil,

And we watched him out of sight, and we conjured up the devil!

Oh, the things I haven’t seen and the things I haven’t known.

What with hedges and ditches till after I was grown,

And yanked both ways by my mother and my father,

With a “Which would you better?” and a “Which would you rather?”

With him for a sire and her for a dam,

What should I be but just what I am?

. . . . . . . . .

She Is Overheard Singing

Oh, Prue she has a patient man,

And Joan a gentle lover,

And Agatha’s Arth’ is a hug-the-hearth,—

But my true love’s a rover!

Mig, her man’s as good as cheese

And honest as a briar,

Sue tells her love what he’s thinking of,—

But my dear lad’s a liar!

Oh, Sue and Prue and Agatha

Are thick with Mig and Joan!

They bite their threads and shake their heads

And gnaw my name like a bone;

And Prue says, “Mine’s a patient man,

As never snaps me up,”

And Agatha, “Arth’ is a hug-the-hearth,

Could live content in a cup;”

Sue’s man’s mind is like good jell—

All one colour, and clear—

And Mig’s no call to think at all

What’s to come next year,

While Joan makes boast of a gentle lad,

That’s troubled with that and this;—

But they all would give the life they live

For a look from the man I kiss!

Cold he slants his eyes about,

And few enough’s his choice,—

Though he’d slip me clean for a nun, or a queen,

Or a beggar with knots in her voice,—

And Agatha will turn awake

While her good man sleeps sound,

And Mig and Sue and Joan and Prue

Will hear the clock strike round,

For Prue she has a patient man,

As asks not when or why,

And Mig and Sue have naught to do

But peep who’s passing by,

Joan is paired with a putterer

That bastes and tastes and salts,

And Agatha’s Arth’ is a hug-the-hearth,—

But my true love is false!

. . . . . . . . .

The Prisoner

All right,

Go ahead!

What’s in a name?

I guess I’ll be locked into

As much as I’m locked out of!

. . . . . . . . .

The Unexplorer

There was a road ran past our house

Too lovely to explore.

I asked my mother once—she said

That if you followed where it led

It brought you to the milk-man’s door.

(That’s why I have not traveled more.)

. . . . . . . . .

Grown-up

Was it for this I uttered prayers,

And sobbed and cursed and kicked the stairs,

That now, domestic as a plate,

I should retire at half-past eight?

. . . . . . . . .

The Penitent

I had a little Sorrow,

Born of a little Sin,

I found a room all damp with gloom

And shut us all within;

And, “Little Sorrow, weep,” said I,

“And, Little Sin, pray God to die,

And I upon the floor will lie

And think how bad I’ve been!”

Alas for pious planning—

It mattered not a whit!

As far as gloom went in that room,

The lamp might have been lit!

My little Sorrow would not weep,

My little Sin would go to sleep—

To save my soul I could not keep

My graceless mind on it!

So up I got in anger,

And took a book I had,

And put a ribbon on my hair

To please a passing lad,

And, “One thing there’s no getting by—

I’ve been a wicked girl,” said I;

“But if I can’t be sorry, why,

I might as well be glad!”

. . . . . . . . .

Daphne

Why do you follow me?—

Any moment I can be

Nothing but a laurel-tree.

Any moment of the chase

I can leave you in my place

A pink bough for your embrace.

Yet if over hill and hollow

Still it is your will to follow,

I am off;—to heel, Apollo!

. . . . . . . . .

Portrait by a Neighbor

Before she has her floor swept

Or her dishes done,

Any day you’ll find her

A-sunning in the sun!

It’s long after midnight

Her key’s in the lock,

And you never see her chimney smoke

Till past ten o’clock!

She digs in her garden

With a shovel and a spoon,

She weeds her lazy lettuce

By the light of the moon,

She walks up the walk

Like a woman in a dream,

She forgets she borrowed butter

And pays you back cream!

Her lawn looks like a meadow,

And if she mows the place

She leaves the clover standing

And the Queen Anne’s lace!

. . . . . . . . .

Midnight Oil

Cut if you will, with Sleep’s dull knife,

Each day to half its length, my friend,—

The years that Time takes off my life,

He’ll take from off the other end!

. . . . . . . . .

The Merry Maid

Oh, I am grown so free from care

Since my heart broke!

I set my throat against the air,

I laugh at simple folk!

There’s little kind and little fair

Is worth its weight in smoke

To me, that’s grown so free from care

Since my heart broke!

Lass, if to sleep you would repair

As peaceful as you woke,

Best not besiege your lover there

For just the words he spoke

To me, that’s grown so free from care

Since my heart broke!

. . . . . . . . .

To Kathleen

Still must the poet as of old,

In barren attic bleak and cold,

Starve, freeze, and fashion verses to

Such things as flowers and song and you;

Still as of old his being give

In Beauty’s name, while she may live,

Beauty that may not die as long

As there are flowers and you and song.

. . . . . . . . .

To S. M.

If he should lie a-dying

I am not willing you should go

Into the earth, where Helen went;

She is awake by now, I know.

Where Cleopatra’s anklets rust

You will not lie with my consent;

And Sappho is a roving dust;

Cressid could love again; Dido,

Rotted in state, is restless still:

You leave me much against my will.

. . . . . . . . .

The Philosopher

And what are you that, wanting you

I should be kept awake

As many nights as there are days

With weeping for your sake?

And what are you that, missing you,

As many days as crawl

I should be listening to the wind

And looking at the wall?

I know a man that’s a braver man

And twenty men as kind,

And what are you, that you should be

The one man in my mind?

Yet women’s ways are witless ways,

As any sage will tell,—

And what am I, that I should love

So wisely and so well?

. . . . . . . . .

Four Sonnets

I

Love, though for this you riddle me with darts,

And drag me at your chariot till I die,—

Oh, heavy prince! Oh, panderer of hearts!—

Yet hear me tell how in their throats they lie

Who shout you mighty: thick about my hair

Day in, day out, your ominous arrows purr

Who still am free, unto no querulous care

A fool, and in no temple worshiper!

I, that have bared me to your quiver’s fire,

Lifted my face into its puny rain,

Do wreathe you Impotent to Evoke Desire

As you are Powerless to Elicit Pain!

(Now will the god, for blasphemy so brave,

Punish me, surely, with the shaft I crave!)

II

I think I should have loved you presently,

And given in earnest words I flung in jest;

And lifted honest eyes for you to see,

And caught your hand against my cheek and breast;

And all my pretty follies flung aside

That won you to me, and beneath your gaze,

Naked of reticence and shorn of pride,

Spread like a chart my little wicked ways.

I, that had been to you, had you remained,

But one more waking from a recurrent dream,

Cherish no less the certain stakes I gained,

And walk your memory’s halls, austere, supreme,

A ghost in marble of a girl you knew

Who would have loved you in a day or two.

III

Oh, think not I am faithful to a vow!

Faithless am I save to love’s self alone.

Were you not lovely I would leave you now;

After the feet of beauty fly my own.

Were you not still my hunger’s rarest food,

And water ever to my wildest thirst,

I would desert you—think not but I would!—

And seek another as I sought you first.

But you are mobile as the veering air,

And all your charms more changeful than the tide,

Wherefore to be inconstant is no care:

I have but to continue at your side.

So wanton, light and false, my love, are you,

I am most faithless when I most am true.

IV

I shall forget you presently, my dear,

So make the most of this, your little day,

Your little month, your little half a year,

Ere I forget, or die, or move away,

And we are done forever; by and by

I shall forget you, as I said, but now,

If you entreat me with your loveliest lie

I will protest you with my favorite vow.

I would indeed that love were longer-lived,

And oaths were not so brittle as they are,

But so it is, and nature has contrived

To struggle on without a break thus far,—

Whether or not we find what we are seeking

Is idle, biologically speaking.

The post A Few Figs from Thistles by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1921) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 2, 2020

27 Quotes from Silent Spring by Rachel Carson

Silent Spring (1962) is the best-known work by Rachel Carson (1907 – 1964), noted American marine biologist and environmental trailblazer. The following selection of quotes from Silent Spring is a passionate argument for protecting the environment from manmade pesticides.

A work of nonfiction by Carson, the book is a gracefully written indictment of the pesticide industry that arose in the late 1950s. It presents a piercing look at the damage these chemicals cause to bird, bees, wildlife, and plant life.

From Rachel Carson’s official website:

“Silent Spring inspired the modern environmental movement, which began in earnest a decade later. It is recognized as the environmental text that changed the world.”

She aimed at igniting a democratic activist movement that would not only question the direction of science and technology but would also demand answers and accountability. Rachel Carson was a prophetic voice and her ‘witness for nature’ is even more relevant and needed if our planet is to survive into a 22nd century.”

From this site’s biography of Rachel Carson:

“The public’s growing awareness of the dangers of chemicals created a natural readership for Silent Spring, serialized in The New Yorker beginning June 16, 1962, and published as a book on September 27, 1962.

Silent Spring sold more than 100,000 copies in the first week and was on the bestseller list by Christmas. By now it has sold more than two million copies and has been translated into more than twenty languages.”

Not everyone applauded Carson’s prescient book. Not surprisingly, she was attacked by the pesticide industry, which conspired to discredit her. A 2012 article in Yale Environment 360 titled “Fifty Years After Silent Spring, Attacks on Science Continue” observed:

“When Silent Spring was published in 1962, author Rachel Carson was subjected to vicious personal assaults that had nothing do with the science or the merits of pesticide use. Those attacks find a troubling parallel today in the campaigns against climate scientists who point to evidence of a rapidly warming world.”

. . . . . . . . .

Rachel Carson U.S. postage stamp, 1981

. . . . . . . . .

“Over increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds, and the early mornings are strangely silent where once they were filled with the beauty of bird song.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature — the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter.”

. . . . . . . . .

“In nature nothing exists alone.”

. . . . . . . . .

“We stand now where two roads diverge. But unlike the roads in Robert Frost‘s familiar poem, they are not equally fair. The road we have long been traveling is deceptively easy, a smooth superhighway on which we progress with great speed, but at its end lies disaster. The other fork of the road — the one less traveled by — offers our last, our only chance to reach a destination that assures the preservation of the earth.”

. . . . . . . . .

“A Who’s Who of pesticides is therefore of concern to us all. If we are going to live so intimately with these chemicals eating and drinking them, taking them into the very marrow of our bones — we had better know something about their nature and their power.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Why should we tolerate a diet of weak poisons, a home in insipid surroundings, a circle of acquaintances who are not quite our enemies, the noise of motors with just enough relief to prevent insanity? Who would want to live in a world which is just not quite fatal?”

. . . . . . . . .

“The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us, the less taste we shall have for destruction.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Nature has introduced great variety into the landscape, but man has displayed a passion for simplifying it. Thus he undoes the built-in checks and balances by which nature holds the species within bounds.”

. . . . . . . . .

“How could intelligent beings seek to control a few unwanted species by a method that contaminated the entire environment and brought the threat of disease and death even to their own kind? Yet this is precisely what we have done. We have done it, moreover, for reasons that collapse the moment we examine them.”

. . . . . . . . .

“We urgently need an end to these false assurances, to the sugar coating of unpalatable facts. It is the public that is being asked to assume the risks that the insect controllers calculate. The public must decide whether it wishes to continue on the present road, and it can do so only when in full possession of the facts.”

. . . . . . . . .

“As crude a weapon as the cave man’s club, the chemical barrage has been hurled against the fabric of life — a fabric on the one hand delicate and destructible, on the other miraculously tough and resilient, and capable of striking back in unexpected ways.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Can anyone believe it is possible to lay down such a barrage of poisons on the surface of the Earth without making it unfit for all life?”

. . . . . . . . .

“We are accustomed to look for the gross and immediate effects and to ignore all else. Unless this appears promptly and in such obvious form that it cannot be ignored, we deny the existence of hazard. Even research men suffer from the handicap of inadequate methods of detecting the beginnings of injury. The lack of sufficiently delicate methods to detect injury before symptoms appear is one of the great unsolved problems in medicine.”

. . . . . . . . .

“It is not my contention that chemical insecticides must never be used. I do contend that we have put poisonous and biologically potent chemicals indiscriminately into the hands of persons largely or wholly ignorant of their potentials for harm. We have subjected enormous numbers of people to contact with these poisons, without their consent and often without their knowledge.”

. . . . . . . . .

“If, having endured much, we have at last asserted our ‘right to know,’ and if by knowing, we have concluded that we are being asked to take senseless and frightening risks, then we should no longer accept the counsel of those who tell us that we must fill our world with poisonous chemicals; we should look about and see what other course is open to us.”

. . . . . . . . .

“To have risked so much in our efforts to mold nature to our satisfaction and yet to have failed in achieving our goal would indeed by the final irony. Yet this, it seems, is our situation.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Have we fallen into a mesmerized state that makes us accept as inevitable that which is inferior or detrimental, as though having lost the will or the vision to demand that which is good?”

. . . . . . . . .

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

“If the Bill of Rights contains no guarantee that a citizen shall be secure against lethal poisons distributed either by private individuals or by public officials, it is surely only because our forefathers, despite their considerable wisdom and foresight, could conceive of no such problem.”

. . . . . . . . .

“When the public protests. confronted with some obvious evidence of damaging results of pesticide applications, it is fed little tranquilizers pills of half truth.”

. . . . . . . . .

“No witchcraft, no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The people had done it themselves.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Most of us walk unseeing through the world, unaware alike of its beauties, its wonders, and the strange and sometimes terrible intensity of the lives that are being lived about us.”

. . . . . . . . .

“The fact that every meal we eat carries its load of chlorinated hydrocarbons is the inevitable consequence of the almost universal spraying or dusting of agricultural crops with these poisons.”

. . . . . . . . .

“When one is concerned with the mysterious and wonderful functioning of the human body, cause and effect are seldom simple and easily demonstrated relationships. They may be widely separated both in space and time. To discover the agent of disease and death depends on a patient piecing together of many seemingly distinct and unrelated facts developed through a vast amount of research in widely separated fields.”

. . . . . . . . .

“By their very nature chemical controls are self-defeating, for they have been devised and applied without taking into account the complex biological systems against which they have been blindly hurled.”

. . . . . . . . .

“The balance of nature is not a status quo; it is fluid, ever shifting, in a constant state of adjustment. Man, too, is part of this balance.”

. . . . . . . . .

“We in this generation, must come to terms with nature, and I think we’re challenged as mankind has never been challenged before to prove our maturity and our mastery, not of nature, but of ourselves.”

. . . . . . . . .

“In this now universal contamination of the environment, chemicals are the sinister and little-recognized partners of radiation in changing the very nature of the world—the very nature of its life.”

More about Silent Spring by Rachel Carson

The Story of Silent Spring

How Silent Spring Ignited the Environmental Movement

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Wikipedia

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 27 Quotes from Silent Spring by Rachel Carson appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 29, 2020

Rachel Carson

Rachel Carson (May 27, 1907 – April 14, 1964) was a noted American marine biologist, conservationist, and writer whose holistic view of the natural world shaped today’s environmental science. Her writing as a popular scientist educated readers about how every entity interacts with the broader web of life.

This interconnectedness influenced her research into the indiscriminate use of chemical insecticides and the resulting book, Silent Spring (1962), her best known, raised questions and awareness that contributed to the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Though Rachel Carson is regarded more as a scientist and environmentalist, there’s no question that her passion for literature fueled her graceful and impassioned writings.

Childhood and family history

Rachel Louise Carson’s mother, Maria, was the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, who received a classical education in an all-female seminary school. Her father, Robert, didn’t complete high school and worked at a series of unfulfilling jobs. The couple married when Maria was twenty-five and Robert was thirty years old.

Maria gave piano lessons to supplement Robert’s erratic employment earnings. Their first child, Marian, was born in 1897, followed by young Robert, in 1899, before Rachel eight years later, on May 27, on a small Pennsylvania farm in the town of Springdale, along the Allegheny River.

The Carson home had four rooms, a fireplace for heat, and no indoor plumbing, with 64 acres of fields and orchards and brush to explore, which fostered a curiosity and intensity in young Rachel. Her mother nurtured her creativity, with books and art supplies, games, and puzzles. Rachel especially loved stories about animals: Beatrix Potter’s books, when a young reader, Kenneth Grahame’s A Wind in the Willows (1908) and, as an older reader, Gene Stratton Porter’s novels.

In 1913, at six years of age, Rachel attended Springdale Grammar School. Two years later, she wrote a story called “The Little Brown House” about a pair of wrens seeking shelter. In the fourth grade, she wrote another, “The Sleeping Rabbit.”

In 1918, the children’s magazine, St. Nicholas, published “A Battle in the Clouds by Rachel L. Carson (Age 10),” for which she received a Silver Badge. By the time she was twelve years old, she had had four stories published and earned ten dollars for her writing.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Education

After completing the tenth grade in Springdale Grammar School, Rachel studied at Parnassus High School in Kensington, Pennsylvania, and graduated top of her class.

She received a scholarship at the Pennsylvania College for Women in Pittsburgh (now Chatham University) and began to study English in 1925, but switched to biology in her junior year, inspired by the teachings of Mary Scott Skinker, who emphasized the natural world’s interconnectivity.

She graduated magna cum laude in 1928 and in August received a Full Fellowship at Wood’s Hole marine biological laboratory in Maine. Inspired to continue her studies, she applied twice to Johns Hopkins University; on her second attempt, they offered a scholarship, and she completed her masters in zoology in 1932.

As a doctoral candidate, she taught part-time to support her family, but dropped out after her father died in 1935 to work full-time.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Working life

When Rachel began working at the Federal Bureau of Fisheries (now the Fish and Wildlife Service), in 1935, she was one of two women employed in non-secretarial positions. Her first assignment was to write the scripts for a 52-episode-long series called Romance under the Waters.

She continued to write radio scripts and pamphlets and eventually she climbed the ranks to aquatic geologist but she never had any scientific duties. The substantial promotion she received, at the age of 42, after a male colleague left the position vacant, did not result in an increase of status and pay comparable to his.

While employed at the Bureau, Rachel also contributed articles to the Baltimore Sun under the name R.L. Carson and she continued to pursue publication elsewhere.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Writing life

One eleven-page essay originally prepared for the Bureau, but deemed better-suited for another kind of audience, was ultimately published in The Atlantic in 1937 as Undersea. This was the basis for her first book and her favorite. Under the Sea Wind (1941) combines biology with aspects of paleontology and geology, and it presents the interactions of species and landscapes against a backdrop of human history.

After WWII, chemical companies sought peace-time uses for products designed as weapons. Rachel edited reports about scientific tests and prepared two alerts about the effects of dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) at work. When she pitched an article on the subject to Reader’s Digest in 1945, they rejected it. In 1946, she began to work more concertedly towards conservation, traveling with Kay Howe or Shirley Briggs, who accompanied her in the field and illustrated her booklets.