Nava Atlas's Blog, page 50

September 22, 2020

The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter (1979)

The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories (1979) is perhaps the best-known work by British author Angela Carter (1940 – 1992). A novelist, short story writer, and journalist, she earned a reputation as one of Britain’s most original writers.

Her influences ranged from fairy tales, gothic fantasy, and Shakespeare to surrealism and the cinema of Godard and Fellini. Her work broken taboos and was often labeled as provocative.

The Bloody Chamber is a collection of re-envisioned imaginings (not, as often described, retellings) of classic European fairy tales. They range in length from very short stories to novellas, and include:

“The Bloody Chamber”

“The Courtship of Mr Lyon”

“The Tiger’s Bride”

“Puss-in-Boots”

“The Erl-King”

“The Snow Child”

“The Lady of the House of Love”

“The Werewolf”

“The Company of Wolves”

“Wolf-Alice”

Carter bristled at inaccurate descriptions of this collection, as described in this 2006 article by Helen Simpson in The Guardian, “Femme Fatale: Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber”:

“The Bloody Chamber is often wrongly described as a group of traditional fairy tales given a subversive feminist twist. In fact, these are new stories, not re-tellings. As Angela Carter made clear, ‘My intention was not to do ‘versions’ or, as the American edition of the book said, horribly, ‘adult’ fairy tales, but to extract the latent content from the traditional stories and to use it as the beginnings of new stories.’”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Angela Carter

. . . . . . . . . .

Here are a pair of reviews that appeared when the book was published in the U.S. in 1980.

The Bloody Chamber and Other Adult Tales

From original review in the Chicago Tribune, April, 1980: This very uncompromising British writer has unsettled readers before — with her sex-laden futuristic fantasies (such as The Passion of New Eve) and her feminist study, The Sadeian Woman.

Here now are Carter’s fiendishly droll versions of fairy and folk tales like Little Red Riding Hood and Puss in Boots. Assorted elves and vampires prowl thought these weather overheated pages — but this is a world in which Beauty outwits her Beast and Bluebeard’s wives live to enjoy their husband’s worldly goods.

It is a world where virgins yawn impatiently at the mention of their purity, and Red Riding Hood can murmur, “I love the company of wolves.”

There’s a creepy lubricity in Carter’s elegant prose that will always make her a cult favorite; but to those who appreciated her voluptuous wit, these revisionist contes may seem her best work so far.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Bloody Chamber on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Fairy Tales Turned into Powerful Adult Stories

From the original review in the Austin Statesman, March, 1980: Angela Carter. novelist, sometimes feminist, has tried her hand at the near impossible and succeeded She has transformed classic fairy tales into potent adult tales.

Her cunning revisions render “Beauty and the Beast,” “Puss in Boots,” “Bluebeard,” and “Little Red Riding Hood” as dangerous and thrilling as they were in childhood. In sumptuous prose, no cozy moments; the landscape is always slightly askew and even happy endings leave unformed questions and unresolved tensions.

Whether inventing new tales or twisting old ones, Carter infuses her stories with disturbing eroticism as she carefully weaves her way back and forth over the fine line that separates sexuality and violence Sometimes a creature’s deviant need is so great that he must be killed; most often the revelation is that yielding is power and tenderness is salvation.

Carter adopts a different form for each of her ten stories: “Bluebeard” becomes a Gothic romance; “Puss in Boots” turns into a bawdy romp. Carter’s own “Werewolf” is a short brutal folk tale. Each story is a fresh invention and the reader is never allowed to be lulled into the simple litany of children’s stories.

All this intensity is eased by Carter’s wonderful comic ingenuity. She mocks forms even as she adopts them and she wryly returns phrases. Her vigorous, lurid prose finally carries this book and forces suspension of disbelief.

Thick and blood-rich, it overwhelms — Carter’s vivid images stayed with me in my dreams: She warns. “These woods enclose and then enclose again, like a system of Chinese boxes opening one into another; intimate perspective of the woods changes endlessly around the interloper … it is easy to lose yourself in these woods.”

More about The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter

An Introduction to The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Angela Carter’s Feminist Mythology

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter (1979) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 20, 2020

The Mark on the Wall by Virginia Woolf (full text)

“The Mark on the Wall,” one of Virginia Woolf‘s early short stories, was published in her first collection of fiction, Monday or Tuesday (1921). It was a prime example of the kind of complex (and sometimes perplexing) modernist short stories that she produced especially in her first years of publishing.

Before getting to the full text of the story, here is a link to an excellent summary and analysis of the story, as well as Leonard Woolf’s foreword to A Haunted House and Other Short Stories, an updated collection that also included this story, published posthumously in 1944.

From Interesting Literature:

“In summary, ‘The Mark on the Wall’ is narrated by someone who recalls noticing a mark on the wall of their house. But the story is not really ‘about’ the mark on the wall, but rather what it prompts the narrator to think about, muse upon and recollect.

As well as speculating on what the mark on the wall might be – a small hole, or perhaps a leftover rose leaf – the narrator’s mind wanders to much bigger questions and meditations, such as the nature of life, where Shakespeare found his inspiration, and even what the afterlife might be like.”

Read the rest of the summary and analysis here.

A Foreword by Leonard Woolf

The original stories in Monday or Tuesday were later collected in A Haunted House and Other Short Stories. Monday or Tuesday was included along with the several other original stories: “A Haunted House,” “An Unwritten Novel,” “The String Quartet,” “Kew Gardens,” and “The Mark on the Wall.”

Mr. Woolf, as he explains here, omitted two of the original stories, “Blue & Green,” and “A society,” as he felt that would have been Virginia’s preference. Here is the Foreword by Leonard Woolf introducing this volume, which was published in the early 1944, after Virginia’s death.

Monday or Tuesday, the only book of short stories by Virginia Woolf which appeared in her lifetime, was published in 1921. It has been out of print for years.

All through her life, Virginia Woolf used at intervals to write short stories. It was her custom, whenever an idea for one occurred to her, to sketch it out in a very rough form and then to put it away in a drawer. Later, if an editor asked her for a short story, and she felt in the mood to write one (which was not frequent), she would take a sketch out of her drawer and rewrite it, sometimes a great many times.

Or if she felt, as she often did, while writing a novel that she required to rest her mind by working at something else for a time, she would either write a critical essay or work upon one of her sketches for short stories. For some time before her death we had often discussed the possibility of her republishing Monday or Tuesday, or publishing a new volume of collected short stories.

Finally, in 1940, she decided that she would get together a new volume of such stories and include in it most of the stories which had appeared originally in Monday or Tuesday, as well as some published subsequently in magazines and some unpublished. Our idea was that she should produce a volume of critical essays in 1941 and the volume of stories in 1942.

In the present volume I have tried to carry out her intention. I have included in it six out of the eight stories or sketches which originally appeared in Monday or Tuesday. The two omitted by me are “A Society,” and “Blue and Green.” I know that she had decided not to include the first and I am practically certain that she would not have included the second.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy reading the full texts of:

“A Haunted House”

“Monday or Tuesday”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Mark on the Wall by Virginia Woolf

Perhaps it was the middle of January in the present that I first looked up and saw the mark on the wall. In order to fix a date it is necessary to remember what one saw. So now I think of the fire; the steady film of yellow light upon the page of my book; the three chrysanthemums in the round glass bowl on the mantelpiece.

Yes, it must have been the winter time, and we had just finished our tea, for I remember that I was smoking a cigarette when I looked up and saw the mark on the wall for the first time. I looked up through the smoke of my cigarette and my eye lodged for a moment upon the burning coals, and that old fancy of the crimson flag flapping from the castle tower came into my mind, and I thought of the cavalcade of red knights riding up the side of the black rock.

Rather to my relief the sight of the mark interrupted the fancy, for it is an old fancy, an automatic fancy, made as a child perhaps. The mark was a small round mark, black upon the white wall, about six or seven inches above the mantelpiece.

How readily our thoughts swarm upon a new object, lifting it a little way, as ants carry a blade of straw so feverishly, and then leave it…If that mark was made by a nail, it can’t have been for a picture, it must have been for a miniature—the miniature of a lady with white powdered curls, powder-dusted cheeks, and lips like red carnations.

A fraud of course, for the people who had this house before us would have chosen pictures in that way—an old picture for an old room. That is the sort of people they were—very interesting people, and I think of them so often, in such queer places, because one will never see them again, never know what happened next.

They wanted to leave this house because they wanted to change their style of furniture, so he said, and he was in process of saying that in his opinion art should have ideas behind it when we were torn asunder, as one is torn from the old lady about to pour out tea and the young man about to hit the tennis ball in the back garden of the suburban villa as one rushes past in the train.

But as for that mark, I’m not sure about it; I don’t believe it was made by a nail after all; it’s too big, too round, for that. I might get up, but if I got up and looked at it, ten to one I shouldn’t be able to say for certain; because once a thing’s done, no one ever knows how it happened. Oh! dear me, the mystery of life; the inaccuracy of thought!

The ignorance of humanity! To show how very little control of our possessions we have—what an accidental affair this living is after all our civilization—let me just count over a few of the things lost in one lifetime, beginning, for that seems always the most mysterious of losses—what cat would gnaw, what rat would nibble—three pale blue canisters of book-binding tools?

Then there were the bird cages, the iron hoops, the steel skates, the Queen Anne coal-scuttle, the bagatelle board, the hand organ—all gone, and jewels, too. Opals and emeralds, they lie about the roots of turnips. What a scraping paring affair it is to be sure!

The wonder is that I’ve any clothes on my back, that I sit surrounded by solid furniture at this moment. Why, if one wants to compare life to anything, one must liken it to being blown through the Tube at fifty miles an hour—landing at the other end without a single hairpin in one’s hair!

Shot out at the feet of God entirely naked! Tumbling head over heels in the asphodel meadows like brown paper parcels pitched down a shoot in the post office! With one’s hair flying back like the tail of a race-horse. Yes, that seems to express the rapidity of life, the perpetual waste and repair; all so casual, all so haphazard…

But after life. The slow pulling down of thick green stalks so that the cup of the flower, as it turns over, deluges one with purple and red light. Why, after all, should one not be born there as one is born here, helpless, speechless, unable to focus one’s eyesight, groping at the roots of the grass, at the toes of the Giants?

As for saying which are trees, and which are men and women, or whether there are such things, that one won’t be in a condition to do for fifty years or so. There will be nothing but spaces of light and dark, intersected by thick stalks, and rather higher up perhaps, rose-shaped blots of an indistinct colour—dim pinks and blues—which will, as time goes on, become more definite, become—I don’t know what…

And yet that mark on the wall is not a hole at all. It may even be caused by some round black substance, such as a small rose leaf, left over from the summer, and I, not being a very vigilant housekeeper—look at the dust on the mantelpiece, for example, the dust which, so they say, buried Troy three times over, only fragments of pots utterly refusing annihilation, as one can believe.

The tree outside the window taps very gently on the pane…I want to think quietly, calmly, spaciously, never to be interrupted, never to have to rise from my chair, to slip easily from one thing to another, without any sense of hostility, or obstacle. I want to sink deeper and deeper, away from the surface, with its hard separate facts. To steady myself, let me catch hold of the first idea that passes…Shakespeare…Well, he will do as well as another.

A man who sat himself solidly in an arm-chair, and looked into the fire, so—A shower of ideas fell perpetually from some very high Heaven down through his mind. He leant his forehead on his hand, and people, looking in through the open door—for this scene is supposed to take place on a summer’s evening—But how dull this is, this historical fiction! It doesn’t interest me at all.

I wish I could hit upon a pleasant track of thought, a track indirectly reflecting credit upon myself, for those are the pleasantest thoughts, and very frequent even in the minds of modest mouse-coloured people, who believe genuinely that they dislike to hear their own praises. They are not thoughts directly praising oneself; that is the beauty of them; they are thoughts like this:

“And then I came into the room. They were discussing botany. I said how I’d seen a flower growing on a dust heap on the site of an old house in Kingsway. The seed, I said, must have been sown in the reign of Charles the First. What flowers grew in the reign of Charles the First?”

I asked—(but, I don’t remember the answer). Tall flowers with purple tassels to them perhaps. And so it goes on. All the time I’m dressing up the figure of myself in my own mind, lovingly, stealthily, not openly adoring it, for if I did that, I should catch myself out, and stretch my hand at once for a book in self-protection.

Indeed, it is curious how instinctively one protects the image of oneself from idolatry or any other handling that could make it ridiculous, or too unlike the original to be believed in any longer. Or is it not so very curious after all? It is a matter of great importance. Suppose the looking glass smashes, the image disappears, and the romantic figure with the green of forest depths all about it is there no longer, but only that shell of a person which is seen by other people—what an airless, shallow, bald, prominent world it becomes!

A world not to be lived in. As we face each other in omnibuses and underground railways we are looking into the mirror that accounts for the vagueness, the gleam of glassiness, in our eyes.

And the novelists in future will realize more and more the importance of these reflections, for of course there is not one reflection but an almost infinite number; those are the depths they will explore, those the phantoms they will pursue, leaving the description of reality more and more out of their stories, taking a knowledge of it for granted, as the Greeks did and Shakespeare perhaps—but these generalizations are very worthless.

The military sound of the word is enough. It recalls leading articles, cabinet ministers—a whole class of things indeed which as a child one thought the thing itself, the standard thing, the real thing, from which one could not depart save at the risk of nameless damnation. Generalizations bring back somehow Sunday in London, Sunday afternoon walks, Sunday luncheons, and also ways of speaking of the dead, clothes, and habits —like the habit of sitting all together in one room until a certain hour, although nobody liked it.

There was a rule for everything. The rule for tablecloths at that particular period was that they should be made of tapestry with little yellow compartments marked upon them, such as you may see in photographs of the carpets in the corridors of the royal palaces. Tablecloths of a different kind were not real tablecloths. How shocking, and yet how wonderful it was to discover that these real things, Sunday luncheons, Sunday walks, country houses, and tablecloths were not entirely real, were indeed half phantoms, and the damnation which visited the disbeliever in them was only a sense of illegitimate freedom.

What now takes the place of those things I wonder, those real standard things? Men perhaps, should you be a woman; the masculine point of view which governs our lives, which sets the standard, which establishes Whitaker’s Table of Precedency, which has become, I suppose, since the war half a phantom to many men and women, which soon—one may hope, will be laughed into the dustbin where the phantoms go, the mahogany sideboards and the Landseer prints, Gods and Devils, Hell and so forth, leaving us all with an intoxicating sense of illegitimate freedom—if freedom exists…

In certain lights that mark on the wall seems actually to project from the wall. Nor is it entirely circular. I cannot be sure, but it seems to cast a perceptible shadow, suggesting that if I ran my finger down that strip of the wall it would, at a certain point, mount and descend a small tumulus, a smooth tumulus like those barrows on the South Downs which are, they say, either tombs or camps.

Of the two I should prefer them to be tombs, desiring melancholy like most English people, and finding it natural at the end of a walk to think of the bones stretched beneath the turf… There must be some book about it. Some antiquary must have dug up those bones and given them a name…What sort of a man is an antiquary, I wonder?

Retired Colonels for the most part, I daresay, leading parties of aged labourers to the top here, examining clods of earth and stone, and getting into correspondence with the neighbouring clergy, which, being opened at breakfast time, gives them a feeling of importance, and the comparison of arrow-heads necessitates cross-country journeys to the county towns, an agreeable necessity both to them and to their elderly wives, who wish to make plum jam or to clean out the study, and have every reason for keeping that great question of the camp or the tomb in perpetual suspension, while the Colonel himself feels agreeably philosophic in accumulating evidence on both sides of the question.

It is true that he does finally incline to believe in the camp; and, being opposed, indites a pamphlet which he is about to read at the quarterly meeting of the local society when a stroke lays him low, and his last conscious thoughts are not of wife or child, but of the camp and that arrowhead there, which is now in the case at the local museum, together with the foot of a Chinese murderess, a handful of Elizabethan nails, a great many Tudor clay pipes, a piece of Roman pottery, and the wine-glass that Nelson drank out of—proving I really don’t know what.

No, no, nothing is proved, nothing is known. And if I were to get up at this very moment and ascertain that the mark on the wall is really—what shall we say?—the head of a gigantic old nail, driven in two hundred years ago, which has now, owing to the patient attrition of many generations of housemaids, revealed its head above the coat of paint, and is taking its first view of modern life in the sight of a white-walled fire-lit room, what should I gain?— Knowledge? Matter for further speculation? I can think sitting still as well as standing up.

And what is knowledge? What are our learned men save the descendants of witches and hermits who crouched in caves and in woods brewing herbs, interrogating shrew-mice and writing down the language of the stars? And the less we honour them as our superstitions dwindle and our respect for beauty and health of mind increases…Yes, one could imagine a very pleasant world. A quiet, spacious world, with the flowers so red and blue in the open fields.

A world without professors or specialists or house-keepers with the profiles of policemen, a world which one could slice with one’s thought as a fish slices the water with his fin, grazing the stems of the water-lilies, hanging suspended over nests of white sea eggs…How peaceful it is drown here, rooted in the centre of the world and gazing up through the grey waters, with their sudden gleams of light, and their reflections—if it were not for Whitaker’s Almanack—if it were not for the Table of Precedency!

I must jump up and see for myself what that mark on the wall really is—a nail, a rose-leaf, a crack in the wood?

Here is nature once more at her old game of self-preservation. This train of thought, she perceives, is threatening mere waste of energy, even some collision with reality, for who will ever be able to lift a finger against Whitaker’s Table of Precedency? The Archbishop of Canterbury is followed by the Lord High Chancellor; the Lord High Chancellor is followed by the Archbishop of York.

Everybody follows somebody, such is the philosophy of Whitaker; and the great thing is to know who follows whom. Whitaker knows, and let that, so Nature counsels, comfort you, instead of enraging you; and if you can’t be comforted, if you must shatter this hour of peace, think of the mark on the wall.

I understand Nature’s game—her prompting to take action as a way of ending any thought that threatens to excite or to pain. Hence, I suppose, comes our slight contempt for men of action—men, we assume, who don’t think. Still, there’s no harm in putting a full stop to one’s disagreeable thoughts by looking at a mark on the wall.

Indeed, now that I have fixed my eyes upon it, I feel that I have grasped a plank in the sea; I feel a satisfying sense of reality which at once turns the two Archbishops and the Lord High Chancellor to the shadows of shades. Here is something definite, something real. Thus, waking from a midnight dream of horror, one hastily turns on the light and lies quiescent, worshipping the chest of drawers, worshipping solidity, worshipping reality, worshipping the impersonal world which is a proof of some existence other than ours.

That is what one wants to be sure of…Wood is a pleasant thing to think about. It comes from a tree; and trees grow, and we don’t know how they grow. For years and years they grow, without paying any attention to us, in meadows, in forests, and by the side of rivers—all things one likes to think about.

The cows swish their tails beneath them on hot afternoons; they paint rivers so green that when a moorhen dives one expects to see its feathers all green when it comes up again. I like to think of the fish balanced against the stream like flags blown out; and of water-beetles slowly raiding domes of mud upon the bed of the river.

I like to think of the tree itself:—first the close dry sensation of being wood; then the grinding of the storm; then the slow, delicious ooze of sap. I like to think of it, too, on winter’s nights standing in the empty field with all leaves close-furled, nothing tender exposed to the iron bullets of the moon, a naked mast upon an earth that goes tumbling, tumbling, all night long.

The song of birds must sound very loud and strange in June; and how cold the feet of insects must feel upon it, as they make laborious progresses up the creases of the bark, or sun themselves upon the thin green awning of the leaves, and look straight in front of them with diamond-cut red eyes … One by one the fibres snap beneath the immense cold pressure of the earth, then the last storm comes and, falling, the highest branches drive deep into the ground again.

Even so, life isn’t done with; there are a million patient, watchful lives still for a tree, all over the world, in bedrooms, in ships, on the pavement, lining rooms, where men and women sit after tea, smoking cigarettes. It is full of peaceful thoughts, happy thoughts, this tree. I should like to take each one separately—but something is getting in the way…

Where was I? What has it all been about? A tree? A river? The Downs? Whitaker’s Almanack? The fields of asphodel? I can’t remember a thing. Everything’s moving, falling, slipping, vanishing …There is a vast upheaval of matter. Someone is standing over me and saying—

“I’m going out to buy a newspaper.”

“Yes?”

“Though it’s no good buying newspapers … Nothing ever happens. Curse this war; God damn this war!…All the same, I don’t see why we should have a snail on our wall.”

Ah, the mark on the wall! It was a snail.

The post The Mark on the Wall by Virginia Woolf (full text) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 16, 2020

Parable of the Sower & Parable of the Talents by Octavia E. Butler

Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents by Octavia E. Butler are a duo of books intended to have become a trilogy, though the third never came to be. Now that we inhabit the time in which the novels actually take place, they’re more eerily prescient than ever.

When Parable of Sower (1993) begins, Lauren Olamina is a young Black woman just emerging from her teens, navigating the apocalyptic world of Los Angeles in the 2020s. A fight — and flight — for survival leads to her create a new faith called Earthseed, in hopes of repairing the world.

We find Lauren once again at the center of Parable of the Talents, now a young mother and still fighting to salvage humanity with Earthseed, the new faith she founded. Now she’s battling violent bigots and religious fanatics.

Shading from dystopian literature to the kind of richly imagined science fiction Butler was known for, these award-winning novels contain the insightful social commentary that was this esteemed author’s hallmark.

. . . . . . . . . .

New editions of Octavia E. Butler’s works reissued by Grand Central Publishing

. . . . . . . . . .

Grand Central Publishing (a division of Hachette Book Group) has been keeping this important American author in the public eye by regularly reissuing her work in attractive contemporary editions.

Here is a portion of N.K. Jemisin’s Foreword to the 2019 edition of Parable of the Sower:

“Butler does not appear to have intended the Parable novels to be a guidebook — and yet they are. That’s true for all of the most powerful science fiction novels: they offer not only accurate visions of the future, but also suggestions for coping with the resulting changes. We can only imagine what that vision might have included if Butler had been able to complete it; she apparently planned a third novel, Parable of the Trickster.

But maybe it’s just as well that she and Lauren were unable to “discover” that third book of Earthseed. Now, like the communities of Earthseed, it’s our job to create change in fiction and in life. Like Lauren, these days I am comforted not by the platitudes I was raised with, but by the idea that change is a tool I can shape to my advantage, if I am clever and lucky. Claiming the future will be an ugly, brutal struggle, but I’m prepared to go the distance in that fight. The future is worth it.”

(Excerpted from The Parable of the Sower, reissue, April 2019, foreword by N.K. Jemisin, 2018, copyright © 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Parable of the Sower (1993)

Parable of the Sower

on Amazon*

From the 2019 Grand Central Publishing / Hachette edition: From the “grand dame” of science fiction, a dystopian classic of terror and hope about a teenage girl trying to survive in an all-too-real future. When unattended environmental and economic crises lead to social chaos, not even gated communities are safe.

In a night of fire and death, Lauren Olamina, an empath and the daughter of a minister, loses her family and home and ventures out into the unprotected American landscape. But what begins as a flight for survival soon leads to something much more: a startling vision of human destiny and the birth of a new faith, as Lauren becomes a prophet carrying the hope of a new world and a revolutionary idea christened “Earthseed.”

First book in the Parable series, also known as Earthseed. Originally published in 1993, reissued April 30, 2019.

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original 1993 Four Walls Eight Windows edition of Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler: Parable of the Sower is the odyssey of one woman who is twice as feeling in a world that has become doubly dehumanized.

The time is 2025. The place is California, where small walled communities must protect themselves from hordes of desperate scavengers and roaming bands of “Paints,” people addicted to a drug that activates an orgasmic desire to burn, rape, and murder. When one small community is overrun, Lauren Olamina, an 18-year-old back woman, sets off on foot, moving north along the dangerous coastal highways.

She is a “sharer,” one who suffers from a hereditary trait called “hyperempathy,” which causes her to feel others’ pain as well as her own. Parable of the Sower is both a coming of age novel and a road novel, set in the near future, when the dying embers of our old civilization can either cool or be the catalyst for something new.

. . . . . . . . . .

Parable of the Talents (1998)

Parable of the Talents on Amazon*

From the 2019 Grand Central Publishing / Hachette edition: The follow-up to Parable of the Sower, this shockingly prescient novel’s timely message of hope and resistance in the face of fanaticism is more relevant than ever.

In 2032, Lauren Olamina has survived the destruction of her home and family and realized her vision of a peaceful community in northern California based on her newly founded faith, Earthseed.

The fledgling community provides refuge for outcasts facing persecution after the election of an ultra-conservative president who vows to “make America great again.” In an increasingly divided and dangerous nation, Lauren’s subversive colony, a minority religious faction led by a young black woman becomes a target for President Jarret’s reign of terror and oppression.

Years later, Asha Vere reads the journals of Lauren Olamina, a mother she never knew. As she searches for answers about her own past, she also struggles to reconcile with the legacy of a mother caught between her duty to her chosen family and her calling to lead humankind into a better future.

Second book in the Parable series, also known as Earthseed. Originally published in 1998, reissued August 20, 2019. Butler intended Earthseed to be a trilogy, but it was never completed.

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original 1998 Four Walls Eight Windows edition of Parable of the Talents by Octavia E. Butler: Parable of the Talents celebrates the usual Butlerian themes of alienation and transcendence, violence and spirituality, slavery and freedom, and separation and community, to astonishing effect in the shockingly familiar, broken world of 2032.

A continuation of the travails of Lauren Olamina, the heroine of the 1994 Nebula Award finalist Parable of the Sower, Parable of the Talents is told in the voice of Lauren’s daughter Larkin, also called Asha Vere — from whom she has been separated for most of the girl’s life — with sections in the form of Lauren’s journal.

Against a background of a war-torn continent, and with a far-right religious crusader in the office of the U.S. presidency, this is a book about a society whose very fabric has been torn asunder.

As Ms. Butler explains, “Parable of the Sower was a book about problems. I originally intended that Parable of the Talents be a book about solutions. I don’t have solutions, so what I’ve done here is look at the solutions that people tend to reach for when they’re feeling troubled and confused.”

And yet human life, oddly, thrives in this unforgettable novel. And the Lauren of Parable of the Sower blossoms into the full strength of her womanhood, complex and entirely credible.

An incredible passage from Parable of the Talents:

Choose your leaders with wisdom and forethought.

To be led by a coward is to be controlled by all that the coward fears.

To be led by a fool is to be led by the opportunists who control the fool.

To be led by a thief is to offer up your most precious treasures to be stolen.

To be led by a liar is to ask to be told lies.

To be led by a tyrant is to sell yourself and those you love into slavery.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Parable of the Sower & Parable of the Talents by Octavia E. Butler

Reader discussion of Parable of the Sower on Goodreads

Reader discussion of Parable of the Talents on Goodreads

Octavia Butler’s Prescient Vision of a Zealot Elected to “Make America Great Again”

Gloria Steinem on Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Parable of the Sower & Parable of the Talents by Octavia E. Butler appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 14, 2020

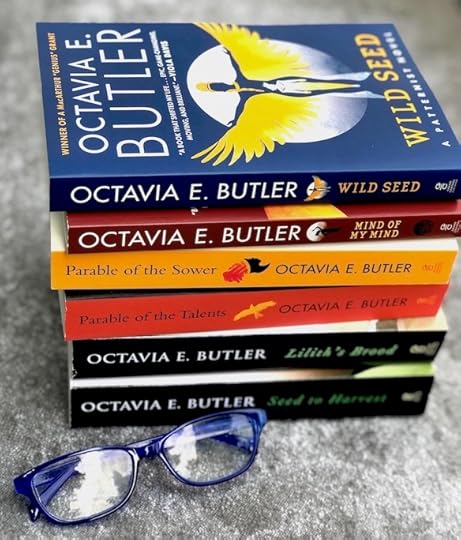

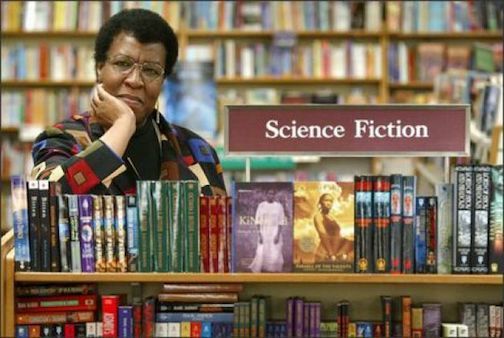

Beautiful New Editions of Octavia E. Butler Classics

It’s possible that Octavia E. Butler’s speculative, dystopian, and science fiction novels and short stories have been over-described as “prescient.” But there’s hardly a better word to some of her major works, and in tandem with her keen observance of human nature, they’ve transcended genre to become classic literature.

In her New York Times obituary, Butler was described as “an internationally acclaimed science fiction writer whose evocative, often troubling novels explore far-reaching issues of race, sex, power, and ultimately, what it meant to be human.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Growing up in Pasadena. California in the 1950s, Butler was drawn to science fiction magazines like Amazing Stories, which sparked flights of imagination. Wondrous possibilities of worlds unknown were opened to a young Black girl who loved to read and write, and who described herself painfully shy and awkward.

With unyielding determination, Butler eventually broke into the white male-dominated genre of science fiction, where she became a trailblazer not only as a woman, but as an African-American.

. . . . . . . . . .

Works by Octavia E. Butler reissued by Grand Central Publishing

. . . . . . . . . . .

Grand Central Publishing (a division of Hachette Book Group) has been keeping this important American author in the public eye by regularly reissuing her work in attractive contemporary editions. The publisher offers this concise biography of Butler, who died at age 59 in 2006.

Octavia E. Butler was a renowned writer who received a MacArthur “Genius” Grant and PEN West Lifetime Achievement Award for her body of work.

She was the author of several award-winning novels including Parable of the Sower, which was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, and was acclaimed for her lean prose, strong protagonists, and social observations in stories that range from the distant past to the far future.

Sales of her books have increased enormously since her death as the issues she addressed in her Afrofuturistic, feminist novels and short fiction have only become more relevant.

Here are some of the editions most recently reissued by Grand Central Publishing. This list will be updated as more are released.

. . . . . . . . . .

Parable of the Sower

From the publisher: From the “grand dame” of science fiction, a dystopian classic of terror and hope about a teenage girl trying to survive in an all-too-real future. When unattended environmental and economic crises lead to social chaos, not even gated communities are safe.

In a night of fire and death, Lauren Olamina, an empath and the daughter of a minister, loses her family and home and ventures out into the unprotected American landscape. But what begins as a flight for survival soon leads to something much more: a startling vision of human destiny and the birth of a new faith, as Lauren becomes a prophet carrying the hope of a new world and a revolutionary idea christened “Earthseed.”

First book in the Parable series, also known as Earthseed. Originally published in 1993, Parable of the Sower was reissued April 30, 2019.

. . . . . . . . . .

Parable of the Talents

From the publisher: The follow-up to Parable of the Sower, this shockingly prescient novel’s timely message of hope and resistance in the face of fanaticism is more relevant than ever.

In 2032, Lauren Olamina has survived the destruction of her home and family and realized her vision of a peaceful community in northern California based on her newly founded faith, Earthseed.

The fledgling community provides refuge for outcasts facing persecution after the election of an ultra-conservative president who vows to “make America great again.” In an increasingly divided and dangerous nation, Lauren’s subversive colony, a minority religious faction led by a young black woman becomes a target for President Jarret’s reign of terror and oppression.

Years later, Asha Vere reads the journals of Lauren Olamina, a mother she never knew. As she searches for answers about her own past, she also struggles to reconcile with the legacy of a mother caught between her duty to her chosen family and her calling to lead humankind into a better future.

Second book in the Parable series, also known as Earthseed. Originally published in 1998, Parable of the Talents was reissued August 20, 2019. Butler intended Earthseed to be a trilogy, but it was never completed.

. . . . . . . . .

Mind of My Mind

From the publisher: A young woman harnesses the power of a viral mutation and challenges the ruthless man who controls her, in this brilliantly provocative novel from the award-winning author of Parable of the Sower.

Mary is a treacherous experiment. Her creator, an immortal named Doro, has molded the human race for generations, seeking out those with unusual talents like telepathy and breeding them into a new sub-race of humans who obey his every command. The result is Mary: a young black woman living on the rough outskirts of Los Angeles in the 1970s, who has no idea how much power she will soon wield.

Doro knows he must handle Mary carefully or risk her ending like his previous experiments: dead, either by her own hand or Doro’s. What he doesn’t suspect is that Mary’s maturing telepathic abilities may soon rival his own power. By linking telepaths with a viral pattern, she will create the potential to break free of his control once and for all-and shift the course of humanity.

Second book in the Patternist series. Originally published in 1977, Mind of My Mind was reissued August 4, 2020.

. . . . . . . . .

Wild Seed

From the publisher: Doro knows no higher authority than himself. An ancient spirit with boundless powers, he possesses humans, killing without remorse as he jumps from body to body to sustain his own life. With a lonely eternity ahead of him, Doro breeds supernaturally gifted humans into empires that obey his every desire. He fears no one — until he meets Anyanwu.

Anyanwu is an entity like Doro and yet different. She can heal with a bite and transform her own body, mending injuries and reversing aging. She uses her powers to cure her neighbors and birth entire tribes, surrounding herself with kindred who both fear and respect her. No one poses a true threat to Anyanwu — until she meets Doro.

The moment Doro meets Anyanwu, he covets her; and from the villages of 17th-century Nigeria to 19th-century United States, their courtship becomes a power struggle that echoes through generations, irrevocably changing what it means to be human.

Fourth book in the Patternist series. Originally published in 1980, Wild Seed was reissued March 17, 2020.

. . . . . . . . .

Clay’s Ark

From the publisher: A gripping tale of survival as an alien pandemic irrevocably changes humanity. In a violent near-future, Asa Elias Doyle and her companions encounter an alien life form so heinous and destructive, they exile themselves in the desert so as not to contaminate other humans.

Resisting the compulsion to infect others is mental agony, but succumbing would mean relinquishing their humanity and free will. Desperate, they kidnap a doctor and his two daughters as they cross the wasteland — and, in doing so, endanger the world. The second novel in the Seed to Harvest series

Fifth book in the Patternist series. Originally published in 1984, Clay’s Ark was reissued September 1, 2020.

. . . . . . . .

Octavia E. Butler’s books are available on Amazon*

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . . .

New Octavia E. Butler editions coming soon

Patternmaster (first book in the Patternist series – December 2020

Dawn (first book in the Xenogenesis series) – April 2021

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Octavia E. Butler

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Beautiful New Editions of Octavia E. Butler Classics appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 8, 2020

Imagining Helen: The Life of Translator Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter

I first heard about Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter (1876 – 1963) when I fell in love with her grandson, a visiting American graduate student at my university in New Zealand. I knew of the great German novelist Thomas Mann but had not read his novels, and certainly had never wondered about how they came to appear in English.

“My grandmother was Mann’s translator,” my new boyfriend informed me. I was mildly impressed. He told me a little about her: how forbiddingly intellectual she was, how un-grandmotherly.

His mother, Patricia, who soon became my mother-in-law, always spoke with mixed awe and resentment of her illustrious mother, though adoringly of her illustrious father, a renowned paleographer.

I learned more when in her seventies Patricia set out to write a biography of both her parents. Helen’s achievement was extraordinary. Between 1924 and 1960 she translated twenty-two of Mann’s novels and nonfiction works, under contract to Knopf as his sole translator. Mann had been widely read and celebrated in Germany but was barely known to English-language readers.

Helen’s first translation, Buddenbrooks, brought Mann instant acclaim and a place in the pantheon. Three years later, after The Magic Mountain was published, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. The pace kept up for the next thirty-three years, until Helen at last withdrew to attend to her own long-deferred ambitions.

“The time has come for me to retire as your translator, after all these years,” she wrote to Mann with typical self-deprecation. “The reason is perhaps silly: in the end of my life I have so many things in my head that I find I must get them down, whether they ever find a publisher or no.”

She and Mann, by now both elderly, had become affectionate friends after years of tension: he had resented having a female translator and constantly pushed her to work faster, rarely expressing praise or appreciation for her meticulous work and its essential contribution to his vast success.

. . . . . . . . . .

Helen at age 18

. . . . . . . . . .

Patricia, an accomplished writer herself, delved deeply into her project, tracing her parents’ trajectories from the U.S. to Germany to England and back, interviewing relatives and colleagues, studying family history and the material her parents had left behind.

Her father, Elias Lowe, had been prolific, not only in published writing but in his letters and his pocket diaries, dozens of them, where he noted everything from the academic calendar at Oxford where he was a professor to the important people he had lunch with and the vagaries of his digestive system.

Helen, on the other hand, was elusive. She had produced thousands of pages of lucid and elegant translation. She wrote a long, insightful essay about Mann’s post-Second World War masterpiece Doctor Faustus, and another substantial essay about her career as his translator. But there was not much else–the correspondence over many years between herself, Mann, and the Knopfs, a few family letters.

Although Helen kept letters from her adult daughters, they did not keep hers. Despite the fact that she strove all her life to succeed as a writer of poetry and fiction, very little of her own creative writing has survived: a small book of poetry published by Oxford University Press, and her one solid success, the play Abdication, triumphantly produced in Dublin for its first and only run, and later published in book form by Knopf.

Patricia often spoke about her parents. Her narrative, long before she began writing about them, was that her father was charming and distinguished, earning her respectful devotion as a daughter, while her mother was distant and cold. Her mother’s work seemed less important than her father’s, with his magnum opus, the 12-volume Codices of ancient Latin manuscripts and his status not only as an Oxford don but as a founding member, with Einstein, of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ.

Based in part on what I knew from my husband and his cousins, I had a less august impression of Elias. From them I’d formed a picture of a rather arrogant and selfish man who took others’ attention for granted. Most of the cousins felt, like Patricia, that Helen was intimidating. Their memories of her were thin.

In his final years, Elias confided in Patricia about the crisis from which his marriage had never recovered. When they first married he had persuaded his sexually inexperienced 30 year-old bride to allow him to sleep with other women on his frequent professional travels. But years later when he slept with a young friend of their eldest daughter, Helen was outraged and unforgiving.

Patricia found her mother’s reaction incomprehensible. Her parents’ relationship, she believed, was more intellectual than romantic, with her mother indifferent to his affairs. So why was she so distraught on this occasion? It wasn’t even his fault, Patricia said—the girl had come to their house in Oxford intent on seduction and he had succumbed.

Helen and Elias never divorced, but their life from then on alternated uneasily between separations and awkward attempts to live together again. The story sounded suspicious to me: it seemed far more likely that this lifelong philanderer, a man of status and influence, had been the aggressor.

Patricia and I shared a serious interest in writing and also in feminism, from our different generational perspectives. She thought I sometimes went too far, with my disregard of conventions; I thought she clung to conformity. Helen herself was an avowed feminist. It seemed to me that her life was a feminist cautionary tale: a gifted, educated woman whose own artistic commitment was constantly subordinated to the needs of the great writer as well as those of her husband and three children.

The struggles of her life had echoes in my own. I had no claims whatsoever to the kind of brilliance and achievement that Helen inarguably had, but I too wrestled with the competing needs of family and artistic calling, and with my own ambivalence around claiming any recognition. Helen was not my mother. I had not suffered, as my mother-in-law had, from feeling neglected by her. And so I was freer to empathize, to give Helen the benefit of the doubt, to imagine her subjective experience.

My defense of Helen might have prompted Patricia to see her mother in a more forgiving and sympathetic light, reflected in the portrait that she now drew in her memoir. Over the next few years she worked hard on research and writing, often sharing it with me as she went along. Sadly, before she had completed her biography she began to lose some of her own capacity.

Seeing that the project was not going to get finished, I helped her publish about 80 pages, along with some of her own poems and stories. The launch of this little volume, a few months before her death, was a happy moment for her: her mild dementia made her believe that she had become the celebrated writer she had always longed to be.

. . . . . . . . . .

Helen and daughters in 1920

. . . . . . . . . .

I inherited Patricia’s research: boxes of folders with documents, letters, notes on her reading and travels, newspaper clippings. I knew she would have wanted me to finish what she had tried so hard to do, and the knowledge weighed on me. But I had no interest in writing biography.

After a while, though, another idea took hold: the idea of writing fiction about this extraordinary and enigmatic woman. A short story? A novella? A novel? I wasn’t sure. I opened up the boxes of folders and spent hours with them. I read her play, which I’d always avoided, written in blank verse about the abdication of Edward Vlll in 1936—and found it beautiful and compelling.

I read some of Mann’s novels, marveling at the scale and depth of these mighty works, and what it must have taken to render them into English. I read biographies of Mann and a short biography of Helen, In Another Language, written soon after her death. The author glossed over Helen’s complexities but usefully noted the milestones of her work and her historical times. He mentioned a novel written after her retirement, Sea Change, that won praise from Mann and his wife but never found a publisher—a mystery, since no one in the family recalls ever seeing it.

I read Helen’s personal letters and others written to her, discovering a very likable, witty, politically aware woman who adored her children and friends. And, surprisingly, a woman who loved her husband passionately until their relationship was abruptly truncated by the crisis.

I read Elias’s diaries, now housed in the Morgan Library of New York. In that silent wood-paneled room, with stacks of his tiny diaries in front of me, I could almost hear the voice of this man across the decades. I learned that the story he had told Patricia about the “seduction” was not the whole truth. In the diaries he noted several meetings with the girl both before and after the moment that he’d confessed to, including at least one time in Paris. It was either a full-blown affair or he’d been grooming her. Helen was indeed grievously betrayed. He broke her heart.

I felt more and more that I knew this woman, my grandmother-in-law, and I liked her enormously. In this strange, one-sided, cross-generational way, reaching from the living to the dead, Helen became my friend. And I wanted very much to let the world see who she was—at least, my view of her. So I wrote my novel Anticipation, adding invented incidents and characters to the slender factual record — all the time with the uneasy awareness that this perennially self-critical woman would very likely disapprove.

Anticipation is still looking for a publisher. I hope it won’t share Sea Change’s fate. I want readers, especially those with curiosity about women whose brilliance is hidden behind towering male figures, to have the chance to meet Helen Lowe-Porter and follow her spirited, determined journey.

Contributed by Jo Salas, a New Zealand-born writer living in the Mid-Hudson Valley of New York. Her short fiction has appeared in literary journals and anthologies, earning awards and a Pushcart Prize nomination. Her novel Dancing with Diana was published in 2015 by Codhill Press. Jo also writes extensively about Playback Theatre, with numerous essays and three books including Improvising Real Life: Personal Story in Playback Theatre, now published in 10 languages. Find her on the web at josalas.com.

References

Lowe-Porter, Helen Tracy. Abdication or All is True. Alfred A. Knopf, 1950.

Lowe-Porter, Helen Tracy. Casual Verse. Oxford University Press, 1957.

Lowe, Patricia Tracy. A Marriage of True Minds: A memoir of my parents, Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter and Elias Avery Lowe. Tusitala Publishing, 2006, 2016.

Mann, Thomas. The Magic Mountain. Translated by H. T. Lowe-Porter. Alfred A. Knopf, 1927.

Mann, Thomas. Doctor Faustus. Translated by H. T. Lowe-Porter. Alfred A. Knopf, 1948.

Thirlwall, John C. In Another Language: A Record of the Thirty-Year Relationship between Thomas Mann and His English Translator, Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter. Alfred A. Knopf, 1966.

Discover other under-appreciated trailblazers in Other Rad Voices on this site.

The post Imagining Helen: The Life of Translator Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 7, 2020

6 Essential Novels by Daphne du Maurier

If you want to delve into the novels of Daphne du Maurier (1907 – 1989), where should you begin? The prolific British novelist, playwright, and short-story writer started her publishing career at age twenty-two with The Loving Spirit (1931), her first novel, and went on to publish numerous works of full-length and short fiction as well as nonfiction and plays.

Arguably, Rebecca (1938) is du Maurier’s masterwork and best-known work. And there’s a group of novels among her canon that approach it in terms of quality and longevity. Here we’ll list the books that Dame Daphne is best remembered for.

With the exception of The Loving Spirit, all of the following have also been made into well-known films, sometimes more than once.

The Loving Spirit (1931)

Though no longer as well known as some of du Maurier’s more iconic works, The Loving Spirit is included here because it was her first, and launched what would become a stellar career.

Beginning in the early 1800s, The Loving Spirit tells the story of the Coombes family and is mainly set in Cornwall, a part of England in which the author spent much of her life. Janet Coombes marries her cousin, Thomas Coombes, who is a shipbuilder. The novel follows the adventures and trials of this family for four generations.

A modern reprint of this novel rightly described it as having “established du Maurier’s reputation and style with an inimitable blend of romance, history, and adventure.”

Many readers who are familiar with du Maurier’s later, and more famous works, have been delighted to discover her first novel. More about The Loving Spirit.

. . . . . . . . .

Jamaica Inn (1936)

Jamaica Inn is a period piece set in Cornwall, England in 1820. Central to the story is a group of “wreckers” — murderers who run ships aground, kill sailors, and steal cargo.

Upon her mother’s death, Mary Yellan moves from the farm in Helford where she was raised, to live with her mother’s sister. Her Aunt Patience is married to a vicious drunkard who has her completely intimidated.

Mary soon realizes that things aren’t as they should be at this inn, which never has guests and isn’t open to the public. Filled with fascinating and creepy characters, Jamaica Inn is one of Daphne du Maurier’s best-known works. The film adaptation of Jamaica Inn came out in 1939 and was directed by Alfred Hitchcock. More about Jamaica Inn.

. . . . . . . . .

Rebecca (1938)

Rebecca is surely the most iconic of du Maurier’s novels. It celebrated its eightieth anniversary of publication in 2018, never having gone out of print. “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again,” is one of the most iconic first lines in English literature.

The story is cleverly told in the first person by the shy, awkward, and nameless young bride of the older, mysterious Maxim de Winter. She is, like the other inhabitants of Manderley castle, haunted by the shadow by her husband’s deceased first wife, Rebecca. Like the best of du Maurier’s works, this one keeps the reader guessing until the very end.

The film adaptation of Rebecca, also directed by Alfred Hitchcock, came out in 1940. There have been a few mini-series adaptations as well. More about Rebecca.

. . . . . . . . .

Frenchman’s Creek (1941)

Frenchman’s Creek is another of du Maurier’s Cornwall-set historical novels. Set during the reign of King Charles II. the story centers on a love affair between Dona, Lady St. Columb, and Jean-Benoit Aubéry, a French pirate. The novel was reissued in a new edition in 2020. From the publisher (Sourcebooks):

“A classic from master of gothic romance and suspense, Daphne du Maurier, Frenchman’s Creek is an electrifying tale of love and scandal on the high seas. Jaded by the numbing politeness of London in the late 1600s, Lady Dona St. Columb revolts against high society. She rides into the countryside, guided only by her restlessness and her longing to escape. But when chance leads her to meet a French pirate, hidden within Cornwall’s shadowy forests, Dona discovers that her passions and thirst for adventure have never been more aroused.”

The first film adaptation of Frenchman’s Creek was released in 1944. It starred the versatile Joan Fontaine as Lady Dona, in a very different role than the one she portrayed as the second Mrs. de Winter in the first film version of Rebecca. More about Frenchman’s Creek.

. . . . . . . . .

My Cousin Rachel (1951)

My Cousin Rachel, like Rebecca, is a romantic thriller. It’s set primarily on a large estate in Cornwall, England, where du Maurier drew real-life inspiration from Antony House. There she saw a portrait of a woman named Rachel Carew, and the creative spark was lit.

Told by Philip young man heir to the estate of his uncle. The uncle, who marries the mysterious Rachel, rapidly and mysteriously declines and dies. Has he been poisoned by his young wife? Rachel, like eponymous Rebecca, remains a puzzle to the end. Is she a devil or an angel? The reader must decide.

The first, and very well-received film adaptation of My Cousin Rachel came out in 1951, starring Olivia de Havilland, with Richard Burton in his first film role. There have been several adaptations since. including the less-than-successful 2017 film. More about My Cousin Rachel.

. . . . . . . . .

The Scapegoat (1957)

The Scapegoat was one of du Maurier’s successful mid-career novels, coming after Jamaica Inn, Rebecca, and My Cousin Rachel. In her skillful hands, this suspense novel makes an ingenious doppelgänger plot work on many levels.

It’s the story of a disaffected Englishman and an aristocratic Frenchman who meet by an accidental encounter and are at once struck by how much they resemble one another. John, an English academic, is compelled by Count Jean de Gué into switching places with him. What ensues is how he is swept into the count’s complicated intrigues and family life.

The 1959 film version of The Scapegoat starred Alec Guinness and Bette Davis. More about The Scapegoat.

. . . . . . . . . .

Daphne du Maurier page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 6 Essential Novels by Daphne du Maurier appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

The House on the Strand by Daphne du Maurier (1969)

The House on the Strand (1969) is one of prolific British author Daphne du Maurier’s later novels, and perhaps one of those less widely read and not as critically acclaimed.

The story, set in her own beloved Cornwall, is one of time travel, with elements of the gothic and supernatural. The narrator, Richard (Dick) Young, gains access to a drug that transports him from the present day (and a life he finds rather dreary) to the 14th century. There, he becomes involved in the lives of those he meets, and his two worlds collide.

A recent reconsideration of The House on the Strand on the official Daphne du Maurier site, sums up the novel’s storyline:

“In The House on the Strand, protagonist Dick Young agrees to test out a drug which his old university friend, Magnus, has developed. Staying in Magnus’s family home, Kilmarth, Dick takes the drug and is transported back in time to the fourteenth-century where he shadows his guide, Roger Kylmerth, and is immersed in a world of intrigue, adultery, and murder.

Increasingly frustrated with his modern day existence, Dick escapes into this secret other world, fascinated by the beautiful Isolda Carminowe, the adventurer Sir Otto Bodrugan, and his malevolent sister Joanna.

But Dick’s addiction to his ‘trips’ to the fourteenth-century soon becomes a danger to himself and those around him as by the end of the novel the professor is dead, Dick has tried to strangle his wife and he is experiencing paralysis.”

Both reader and critical reviews of this novel by Daphne du Maurier have proven more decidedly mixed than those of some of there other classics (including Rebecca, My Cousin Rachel, Jamaica Inn, and others), it has had its share of admirers on both sides of the Atlantic.

The following review captures the mixed reception the novel received upon its publication.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: The Scapegoat by Daphne du Maurier

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1969 review of The House on the Strand by Daphne du Maurier

From the original review by W.G. Rogers, Saturday Review Syndicate, October, 1969: Tywardreath, Par, Polmear, Polpey, the Gratten, Lampetho — these place names from Cornwall are as much tongue twisters as if they were Welsh.

This is the stony, bleak, Land’s End setting — endpapers chart it and you recognize this as the country of Daphne du Maurier herself and many of her books. It’s a tale that unwinds in two eras, two ages — in the first half of the 14th century and the last half of the comforting, familiar, un-spooky 20th century.

Richard Young, just out of a publishing position in London, is spending some idle weeks in a home, Kilmarth, lent by his friend Magnus Lane, a biophysicist. As students together, they often came there for vacations. Now Lane stays in London and Young waits not too impatiently for the arrival of his American wife Vita and her two sons by a former marriage.,

While waiting, he has been indulging in some fantastic back-tracking. Lane in off-duty hours has concocted a potion that whisks a man on a broomstick back six centuries. Three bottles of his drug, labeled A, B, and C, are locked in his cellar. One swig of A, at Lane’s request, and Young is off to adventure.

When the story opens, he is already traipsing around in the reign of Edward II and Edward III. For a guide he has Sir Roger, and the cast of medieval characters in the drama that he watches, unseen by them, includes the families of Ferrers, Bodrugan, Champernoune, and Carminowe.

The switch over the six-century gap is abrupt and drastic. First, we have Mrs. Collins, caretaker in the 1960s, plus auto, railroad, telephone, mail, and motorboard. Then in contrast there is primitive, thatched, horseback-riding Cornwall with true and furze for the fireplace, rushes for carpet, muddy roads, stables, peasants, the belt with dagger, and also mysterious potions almost as powerful as the modern ones.

Even the geography has changed. Railroad tracks are gone, estuary replaces marsh, and winter surprisingly replaces summer. The daring visits have some ill consequences for Young like nausea and confusion, but the effects of this time machine in reverse, this fanciful looking back ward, wear off quickly.

There are other complications. Vita and the boys show up earlier than expected. Vita doesn’t understand the mystifying phone conversations between Lane and her husband. She also is upset by his unexplained disappearances — is he having an affair? When he is still under the influence of the drugs, he looks to her simply and disgustingly drunk.

He is in fact drunk with his baffling adventure. He witnesses a brutal murder six hundred years in the past, and with his tongue still loose as an effect of the hallucination, he mentions it most indiscreetly to 20th-century listeners.

There is a death and maybe a murder in the present, followed by an inquest. Some research in genealogies and musty histories is partially revealing. There’s enough to make you suspect that somewhere in this labyrinthine situation there is some truth.

Perhaps in a tale of this ephemeral nature the truth has to be elusive The key device is trite, and for all of this author’s demonstrated skill in plotting and working up goosebumps, a lot of this is hard to believe, even as a fantastical tale.

This is no match for Rebecca, My Cousin Rachel, The Scapegoat, or many other novels among du Maurier’s titles. In a world rent by many dreadful problems, it seems a wast to write this story or to read it. On the other hand, if you’v had enough of problems, here’s an escape.

Start reading by lamplight if you’d like, for the beginning is slow. But du Maurier after a while whips up some suspense and you should finish by light of day.

. . . . . . . . .

The House on the Strand on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

More about The House on the Strand by Daphne du Maurier

The Addiction of Time Travel (review on Tor)

Wikipedia

Review on She Reads Novels

Reader discussion on Goodreads

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The House on the Strand by Daphne du Maurier (1969) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 4, 2020

Rule Britannia by Daphne du Maurier (1972)

Rule Britannia (1972) was the last novel written by Daphne du Maurier, who was known for her tightly plotted, exquisitely crafted thrillers, including the iconic Rebecca (1938).

The story, set in a future version of England, envisioned the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EEC (European Economic Community), a body that was incorporated into the European Union in 1993, well after du Maurier’s time. It was almost as if she was envisioning Brexit.

In fact, the Times of London called it a “Brexit novel,” placing it among others that envisioned Britain striking off on its own in an April 2019 article by Lucy Scholes:

“What are the Brexit novels? Ali Smith’s Autumn, Jonathan Coe’s Middle England, Sam Byers’s Perfidious Albion, Daphne du Maurier’s Rule Britannia? Yes, you read that correctly: nearly 50 years ago the writer famous for her 1938 bestseller Rebecca all but predicted Brexit in her final novel.”

Virago Modern Classics reissued Rule Britannia in 2004, and summarized the plot as follows:

“Emma wakes up one morning to an apocalyptic world. The cosy existence she shares with her grandmother, a famous retired actress, has been shattered: there’s no post, no telephone, no radio — and an American warship sits in the harbor.

As the two women piece together clues about the ‘friendly’ military occupation on their doorstep, family, friends and neighbors gather round to protect their heritage. In this chilling novel of the future, Daphne du Maurier explores the implications of a political, economic and military alliance between Britain and the United States.”

Du Maurier seemed to enjoy writing the novel, finding it clever and satirical. This one was a departure from her usual style, and the result was not kindly met by critics. Some called it absurd or silly; even her biographer, Margaret Foster, deemed it her worst book.

However, the book is being reconsidered in the light of today’s politics. It’s not as far-fetched as it seemed upon first publication. Reader ratings of Rule Britannia on Goodreads are mixed, though a number of them enjoyed the book and noted that it was quite prescient.

And not all critics were scathing at the time it was published; the following review of the novel upon its American publication was a bit more measured.

. . . . . . . . . .

Rule Britannia on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1973 review of Rule Britannia by Daphne du Maurier

From the original review of Rule Britannia by Daphne du Maurier in The Anniston Star, January 1973: It is an England of some unspecified future year, close enough that most resent day people and events are still very much in evidence.

But history is shifting, economically, culturally, and socially, and the powers that be have secretly taken matters into their own hands to form a union of the English-speaking people of Great Britain and America.

The first inkling Ellen, Mad and the boys have of the coalition out there in Cornwall is the sound of planes and the sudden appearance of American marines in their own field. It seems they are in protective custody of some sort, and things are rapidly going from bad go worse.

Now, Mad is not the sort of woman to take such things docilely. At nearly eighty, this famous retired actress still maintains a lively interest in everything, especially her only granddaughter, Ellen, and the six assorted boys, ranging from three years to late teens, that Mad has adopted over the years and set up housekeeping for here in the country.

The Americans get off on the wrong foot by shooting the pet dog of Mr. Trembath, the neighboring farmer. Andy, one of Mad’s boys, eventually retaliates by shooting an American between the eyes with a steel-tipped arrow just outside the house.

This serious matter erupts into a full-scale struggle, as the local people, aided by the mysterious man who lives in the abandoned cottage in the woods, conspire to hide the and protect Andy. And Mad, in her typical unsubtle manner, manages to provoke everyone from the local woman politician to the military authorities, all in the name of protest against the unpopular USUK coalition.

By turns funny and serious, Rule Britannia is surprisingly un-du Maurier, a far cry in theme and style from Rebecca or Frenchman’s Creek, the sort of thing Dame Daphne is famous for.

Like her previous novel, The House on the Strand, it brings in new ideas and new styling, not nearly so appealing, to this reviewer at least, as her finer, more traditional work.

More about Rule Britannia by Daphne du Maurier

Wikipedia

Did Daphne du Maurier Predict Brexit?

Review of Rule Britannia on Heavenali

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Rule Britannia by Daphne du Maurier (1972) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 31, 2020

Angelina Weld Grimké

Angelina Weld Grimké (February 27, 1880 – June 10, 1958), was an American playwright, poet, and educator. She rose to prominence as a figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, though most of her major works were created before that era.

As a writer and woman of color, she was deeply concerned about African-American issues and pervasive racism. Themes of race played a prominent role in her poetry and plays.

Family and background

Angelina was born in Boston, Massachusetts, into a prominent family of biracial civil rights activists and abolitionists. Her father, Archibald Grimké, was the son of a slave and a wealthy white aristocrat. He was the second Black man to graduate from Harvard Law School and for a time served as Vice-President of the NAACP. Her mother, Sarah, came from a middle-class white family of European origin.

With a mixed-race father and a white mother, Angelina was at least 75% white. She was considered Black and identified as such. Angelina’s parents met in Boston, where her father practiced law. They separated when Angelina was a child, and she was raised by her father in Boston.

Angelina’s great-aunts Sarah and Angelina Grimké Weld (the latter practically a namesake) were well-known abolitionists and influential advocates for women’s rights. The elder Angelina had taken a bold step to acknowledge her half-black nephews who were the children of her brother and one of his slaves. Hence, the connection between the Grimké Weld and the Weld Grimké families.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Education and teaching

In 1902 Angelina graduated from the Boston Normal School of Gymnastics, where she earned her degree in physical education. She also attended Wellesley College and Boston University College of Health and Rehabilitation sciences.

After completing her studies, Angelina taught English and physical education in Washington, D.C. She had moved to Washington with her father to be close to her aunt and uncle.

While living in Washington, she taught at the Armstrong Manual Training School, in the city’s segregated area. Angelina also taught at Dunbar High School, a school for black students, which was known for its excellence in academics.

Angelina later connected with another longtime resident of Washington, D.C., fellow poet Georgia Douglas Johnson. Though the two women were affiliated with the Harlem Renaissance literary movement, neither had actually lived in Harlem. Still, they did encounter fellow authors, as the Johnson home was a literary salon for those who were visiting the nation’s capital.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Goldie, Rachel, and Mara: Protest Works

Much of Angelina’s early work was focused on the theme of lynching. Rachel, Angelina’s three-act dramatic play, was one of her earliest milestones. She was inspired to write it after the NAACP’s call for works to counteract the racist, pro-Klan film, The Birth Of A Nation.

First staged in Washington, D.C. in 1916, the production was one of the first dramatic presentations to feature an all-Black cast. As a vehicle to enlighten the American public to the anguish suffered by Black Americans as a result of the brutal practice of lynching, it was generally well-received, though some critics viewed it as overly sentimental for the subject.

The NAACP declared that Rachel was “the first attempt to use the stage for race propaganda in order to enlighten the American people relating to the lamentable condition of ten millions of Colored citizens in this free republic.”

While it may not have had the impact the author intended, it did go on to be staged in New York after its Washington, D.C. run and was officially published in 1920.

The short story “Goldie” was based on the true incident of the killing of Mary Turner in Georgia in 1918. Mary was the Black mother of two children, and pregnant with a third, and was murdered while protesting the lynching of her husband.

Angelina’s second play, Mara, also focused on the theme of lynching.

Poetic Works

One of her early achievements was having poems, short stories, and essays published in The Crisis. The editor of the official publication of the NAACP was the eminent W.E.B. DuBois, and it was a vehicle that helped launch many a literary career.

Her poems were published in The New Negro, a publication by Alain Locke, one of the leading intellectuals in the Black Rights Movement in the earliest part of the 20th-century. He earned a PhD. in Philosophy at Harvard and became the head of the Philosophy Department. He was also a significant supporter of the Black Renaissance and an influence in Angelina’s life.

Angelina’s poetry continued to be included in several anthologies. They included Negro Poets and Their Poems, published in 1923, Caroling Dusk (1927), and The Poetry of the Negro (1949).

A number of poems express her profound feelings, sense of solitude, and longing for affection and love. Her poems, “El Beso” and “Dawn” are written in this fashion. “El Beso” was published in 1909 and expressed her feelings of desire and isolation.

In the poem “Dawn,” she reflects on an early morning when the world is grey, and no stars are visible, then a thrush calls out to announce the dawning of the day.

Some of her poems, including “Beware Lest He Awakes” and “The Black Finger” were written to draw attention to racism and the treatment of Black Americans. Other well-known poems include “The Eyes of My Regret,” “At April,” “The Closing Door,” and “Trees.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Sexuality

It’s widely believed that Angelina was a lesbian or bisexual, something her poems and letters hint at. As something to be kept secret in her time, thwarted desire and loneliness are theme expressed in some of her work. It seemed that she was aware of her leanings from an early age. At 16, she wrote to a female friend,

“I know you are too young now to become my wife, but I hope, darling, that in a few years you will come to me and be my love, my wife! How my brain whirls how my pulse leaps with joy and madness when I think of these two words, ‘my wife.’”