Nava Atlas's Blog, page 54

June 4, 2020

10 Poems by Lucille Clifton, Chronicler of African-American Experience

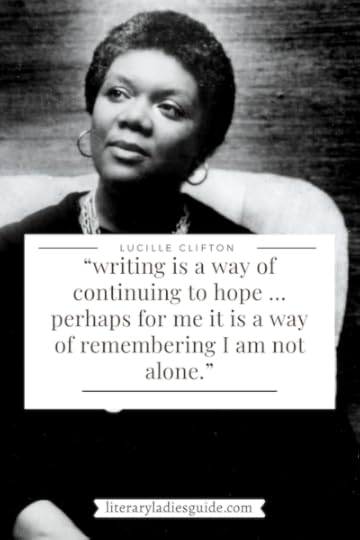

Lucille Clifton (1936 – 2010) was a poet, teacher, and children’s book author whose life and career began in western New York. Her poetry is recognizable because of its purposeful lack of punctuation and capitalization. Here is a selection of 10 poems by Lucille Clifton, a small sampling of her prolific output.

Clifton’s widely respected poetry focuses on social issues, the African-American experience, and the female identity. Her poetry has been praised for its wise use of strong imagery, and lines that have even given the spacing of words meaning.

Poet Elizabeth Alexander praises Clifton’s use of strong language in her poetry, which was often spare and brief. Robin Becker of The American Poetry Review states that Clifton emphasizes the human element and morality of her poetry that’s amplified by the use of improper grammar.

Clifton was devoted to expressing the painful history of African-Americans. Yet she also expressed ideas of beauty and courage, addressing themes of women’s issues, everyday family struggles, and health. Read more about Lucille Clifton and her poetry at Poetry Foundation.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Lucille Clifton

. . . . . . . . . .

homage to my hips (1987)

these hips are big hips

they need space to

move around in.

they don’t fit into little

petty places. these hips

are free hips.

they don’t like to be held back.

these hips have never been enslaved,

they go where they want to go

they do what they want to do.

these hips are mighty hips.

these hips are magic hips.

i have known them

to put a spell on a man and

spin him like a top!

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

the lost baby poem (1987)

the time i dropped your almost body down

down to meet the waters under the city

and run one with the sewage to the sea

what did i know about waters rushing back

what did i know about drowning

or being drowned

you would have been born into winter

in the year of the disconnected gas

and no car we would have made the thin

walk over genesee hill into the canada wind

to watch you slip like ice into strangers’ hands

you would have fallen naked as snow into winter

if you were here i could tell you these

and some other things

if i am ever less than a mountain

for your definite brothers and sisters

let the rivers pour over my head

let the sea take me for a spiller

of seas let black men call me stranger

always for your never named sake

. . . . . . . . . .

1994 (1996)

i was leaving my fifty-eighth year

when a thumb of ice

stamped itself hard near my heart

you have your own story

you know about the fears the tears

the scar of disbelief

you know that the saddest lies

are the ones we tell ourselves

you know how dangerous it is

to be born with breasts

you know how dangerous it is

to wear dark skin

i was leaving my fifty-eighth year

when i woke into the winter

of a cold and mortal body

thin icicles hanging off

the one mad nipple weeping

have we not been good children

did we not inherit the earth

but you must know all about this

from your own shivering life

. . . . . . . . . .

adam thinking

she

stolen from my bone

is it any wonder

i hunger to tunnel back

inside desperate

to reconnect the rib and clay

and to be whole again

some need is in me

struggling to roar through my

mouth into a name

this creation is so fierce

i would rather have been born

. . . . . . . . . .

eve thinking

it is wild country here

brothers and sisters coupling

claw and wing

groping one another

i wait

while the clay two-foot

rumbles in his chest

searching for language to

call me

but he is slow

tonight as he sleeps

i will whisper into his mouth

our names

. . . . . . . . . .

my dream about being white (1987)

hey music and

me

only white,

hair a flutter of

fall leaves

circling my perfect

line of a nose,

no lips,

no behind, hey

white me

and i’m wearing

white history

but there’s no future

in those clothes

so i take them off and

wake up

dancing.

. . . . . . . . . .

sorrow song (1987)

for the eyes of the children,

the last to melt,

the last to vaporize,

for the lingering

eyes of the children, staring,

the eyes of the children of

buchenwald,

of viet nam and johannesburg,

for the eyes of the children

of nagasaki,

for the eyes of the children

of middle passage,

for cherokee eyes, ethiopian eyes,

russian eyes, american eyes,

for all that remains of the children,

their eyes,

staring at us, amazed to see

the extraordinary evil in

ordinary men.

. . . . . . . . . .

wishes for sons (1987)

i wish them cramps.

i wish them a strange town

and the last tampon.

i wish them no 7-11.

i wish them one week early

and wearing a white skirt.

i wish them one week late.

later i wish them hot flashes

and clots like you

wouldn’t believe. let the

flashes come when they

meet someone special.

let the clots come

when they want to.

let them think they have accepted

arrogance in the universe,

then bring them to gynecologists

not unlike themselves.

. . . . . . . . . .

the garden of delight (1991)

for some

it is stone

bare smooth

as a buttock

rounding

into the crevasse

of the world

for some

it is extravagant

water mouths wide

washing together

forever for some

it is fire

for some air

and for some

certain only of the syllables

it is the element they

search their lives for

eden

for them

it is a test

. . . . . . . . . .

blessing the boats (2000)

(at St. Mary’s)

may the tide

that is entering even now

the lip of our understanding

carry you out

beyond the face of fear

may you kiss

the wind then turn from it

certain that it will

love your back may you

open your eyes to water

water waving forever

and may you in your innocence

sail through this to that

. . . . . . . . . . .

Lucille Clifton page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

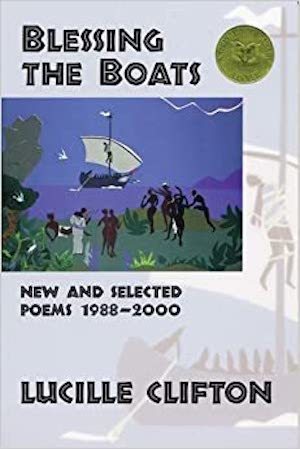

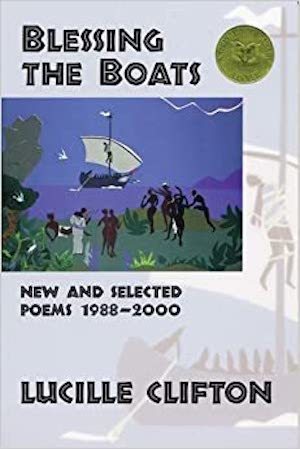

Lucille Clifton’s poetry collections

Good Times (1969)

Good News About the Earth (1972)

An Ordinary Woman (1974)

Two-Headed Woman (1980)

Good Woman: Poems and a Memoir: 1969–1980 (1987)

Next: New Poems (1987)

Quilting: Poems 1987–1990 (1991)

The Book of Light (1993)

The Terrible Stories (1996)

Blessing The Boats: New and Collected Poems 1988–2000 (2000)

Mercy (2004)

Voices (2008)

The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton (2012)

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 10 Poems by Lucille Clifton, Chronicler of African-American Experience appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

10 Poems by Lucille Clifton, Chronicler of the African-American Experience

Lucille Clifton (1936 – 2010) was a poet, teacher, and children’s book author whose life and career began in western New York. Her poetry is recognizable because of its purposeful lack of punctuation and capitalization. Here is a selection of 10 poems by Lucille Clifton, a small sampling of her prolific output.

Clifton’s widely respected poetry focuses on social issues, the African American experience, and the female identity. Her poetry has been praised for its wise use of strong imagery, and lines that have even given the spacing of words meaning.

Poet Elizabeth Alexander praises Clifton’s use of strong language in her poetry, which was often spare and brief. Robin Becker of The American Poetry Review states that Clifton emphasizes the human element and morality of her poetry that’s amplified by the use of improper grammar.

Clifton was devoted to expressing the painful history of African-Americans. Yet she also expressed ideas of beauty and courage, addressing themes of women’s issues, everyday family struggles, and health. Read more about Lucille Clifton and her poetry at Poetry Foundation.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Lucille Clifton

. . . . . . . . . .

homage to my hips (1987)

these hips are big hips

they need space to

move around in.

they don’t fit into little

petty places. these hips

are free hips.

they don’t like to be held back.

these hips have never been enslaved,

they go where they want to go

they do what they want to do.

these hips are mighty hips.

these hips are magic hips.

i have known them

to put a spell on a man and

spin him like a top!

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

the lost baby poem (1987)

the time i dropped your almost body down

down to meet the waters under the city

and run one with the sewage to the sea

what did i know about waters rushing back

what did i know about drowning

or being drowned

you would have been born into winter

in the year of the disconnected gas

and no car we would have made the thin

walk over genesee hill into the canada wind

to watch you slip like ice into strangers’ hands

you would have fallen naked as snow into winter

if you were here i could tell you these

and some other things

if i am ever less than a mountain

for your definite brothers and sisters

let the rivers pour over my head

let the sea take me for a spiller

of seas let black men call me stranger

always for your never named sake

. . . . . . . . . .

1994 (1996)

i was leaving my fifty-eighth year

when a thumb of ice

stamped itself hard near my heart

you have your own story

you know about the fears the tears

the scar of disbelief

you know that the saddest lies

are the ones we tell ourselves

you know how dangerous it is

to be born with breasts

you know how dangerous it is

to wear dark skin

i was leaving my fifty-eighth year

when i woke into the winter

of a cold and mortal body

thin icicles hanging off

the one mad nipple weeping

have we not been good children

did we not inherit the earth

but you must know all about this

from your own shivering life

. . . . . . . . . .

adam thinking

she

stolen from my bone

is it any wonder

i hunger to tunnel back

inside desperate

to reconnect the rib and clay

and to be whole again

some need is in me

struggling to roar through my

mouth into a name

this creation is so fierce

i would rather have been born

. . . . . . . . . .

eve thinking

it is wild country here

brothers and sisters coupling

claw and wing

groping one another

i wait

while the clay two-foot

rumbles in his chest

searching for language to

call me

but he is slow

tonight as he sleeps

i will whisper into his mouth

our names

. . . . . . . . . .

my dream about being white (1987)

hey music and

me

only white,

hair a flutter of

fall leaves

circling my perfect

line of a nose,

no lips,

no behind, hey

white me

and i’m wearing

white history

but there’s no future

in those clothes

so i take them off and

wake up

dancing.

. . . . . . . . . .

sorrow song (1987)

for the eyes of the children,

the last to melt,

the last to vaporize,

for the lingering

eyes of the children, staring,

the eyes of the children of

buchenwald,

of viet nam and johannesburg,

for the eyes of the children

of nagasaki,

for the eyes of the children

of middle passage,

for cherokee eyes, ethiopian eyes,

russian eyes, american eyes,

for all that remains of the children,

their eyes,

staring at us, amazed to see

the extraordinary evil in

ordinary men.

. . . . . . . . . .

wishes for sons (1987)

i wish them cramps.

i wish them a strange town

and the last tampon.

i wish them no 7-11.

i wish them one week early

and wearing a white skirt.

i wish them one week late.

later i wish them hot flashes

and clots like you

wouldn’t believe. let the

flashes come when they

meet someone special.

let the clots come

when they want to.

let them think they have accepted

arrogance in the universe,

then bring them to gynecologists

not unlike themselves.

. . . . . . . . . .

the garden of delight (1991)

for some

it is stone

bare smooth

as a buttock

rounding

into the crevasse

of the world

for some

it is extravagant

water mouths wide

washing together

forever for some

it is fire

for some air

and for some

certain only of the syllables

it is the element they

search their lives for

eden

for them

it is a test

. . . . . . . . . .

blessing the boats (2000)

(at St. Mary’s)

may the tide

that is entering even now

the lip of our understanding

carry you out

beyond the face of fear

may you kiss

the wind then turn from it

certain that it will

love your back may you

open your eyes to water

water waving forever

and may you in your innocence

sail through this to that

. . . . . . . . . . .

Lucille Clifton page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Lucille Clifton’s poetry collections

Good Times (1969)

Good News About the Earth (1972)

An Ordinary Woman (1974)

Two-Headed Woman (1980)

Good Woman: Poems and a Memoir: 1969–1980 (1987)

Next: New Poems (1987)

Quilting: Poems 1987–1990 (1991)

The Book of Light (1993)

The Terrible Stories (1996)

Blessing The Boats: New and Collected Poems 1988–2000 (2000)

Mercy (2004)

Voices (2008)

The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton (2012)

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 10 Poems by Lucille Clifton, Chronicler of the African-American Experience appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 31, 2020

Lucille Clifton

Lucille Clifton (June 26, 1936 – February 13, 2010) was a prolific American poet, teacher, and children’s book author. Clifton’s work focused on issues of race, family affairs, and gender through the lens of the African-American experience.

Clifton’s poetry was first published by Langston Hughes, who included it in his impactful anthology, The Poetry of the Negro (1746-1970).

Poetic style and themes

Clifton’s poetry is easily identified because of the purposeful lack of capitalization and proper punctuation. The central message of her work is the celebration of African-American heritage and the endurance, strength, and beauty of Black women.

Poet Elizabeth Alexander praises Clifton’s use of strong language in her poetry, which was often spare and brief. Robin Becker of The American Poetry Review states that Clifton emphasizes the human element and morality of her poetry that’s amplified by the use of improper grammar.

She devoted to expressing the painful history of African-Americans. Yet she also expressed ideas of beauty and courage. She also created works about women’s issues, everyday family struggles, and health. Her work has been described as feminist.

Clifton sometimes conveyed her messages through the voices of Biblical characters, and paid homage to her personal heroes, including W.E.B. Dubois, Nelson and Winnie Mandela, Huey Newton, and others.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Education and marriage

Born Thelma Lucille Sayles, Lucille Clifton was born in DePew, New York and raised in Buffalo. She attended Howard University and majored in drama, and left to pursue her passion for poetry.

Returning to her hometown in 1955, Clifton completed her studies at Fredonia College and met Fred Clifton, a professor of philosophy at the University of Buffalo. They married three years later. The couple moved to Baltimore, Maryland and raised a family of six children — two sons and four daughters.

Clifton completed her residency at Coppin State College in Baltimore, MD, and subsequently obtained a visiting professorship at Columbia University and at George Washington University. She also taught literature and creative writing at the University of California at Santa Cruz and at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, and was Maryland’s Poet Laureate from 1974 to 1985.

Children’s Book Author

In addition to her many poetry collections, Clifton wrote a number of children’s books as well. One of her best-known series featured a young black boy, Everett Anderson, which included: Some of the Days of Everett Anderson (1970), Everett Anderson’s Goodbye (1983), and One of the Problems of Everett Anderson (2001). She also wrote My Friend Jacob, about a disabled child’s friendship.

Comparing Clifton’s poetry to her children’s books, Jocelyn K. Moody wrote in the Oxford Companion to African American Literature, “Like her poetry, Clifton’s short fiction extols the human capacity for love, rejuvenation, and transcendence over weakness and malevolence even as it exposes the myth of the American dream.”

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Major poetry collections

Clifton published her first poetry collection, Good Times: Poems in 1969. It was widely praised and was named as one of the top ten best books of 1969 on several lists. Her second collection, Good News about the Earth: New Poems (1972) addressed the societal and political changes of the 1960s and 1970s, and paid tribute to the many African American political leaders.

Her third collection, An Ordinary Woman (1974), focused far less on social issues and more about her experiences as an African-American woman.

Clifton’s widely respected poetry, including the well-known “homage to my hips,” embraces female identity. In what is one of her most famous poems, she made the bold statement that her hips “don’t fit into those petty places” and they will not be held back or “enslaved.” Clifton conveys the message that she won’t conform to the societal definition of female beauty, but instead embraces herself and her body.

Reynolds Price wrote in The New York Times Book Review that Clifton’s fourth book was a gracefully written eulogy to Clifton’s parents that celebrated them. It was later incorporated into Good Woman: Poems and a Memoir: 1969-1980, and was followed by Quilting and The Book of Light.

Blessing the Boats addressed her battle with breast cancer. Her poem “1994” was about her the lumpectomy she had that year to remove cancerous cells. At the beginning of the poem, she described the pain of cancer as a “thumb of ice” near the heart. Clifton uses cold imagery throughout this poem to convey feel her fear of loss of identity and femininity through the experience of having lost her breasts and hair, and going through the phases of chemotherapy.

Clifton passed away at the age of 73 in 2010 after a long battle with cancer.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Lucille Clifton page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Awards and honors

Clifton is best known as the first author to have had two pieces of literature as finalists for the Pulitzer Prize: Good Woman: Poems and a Memoir, 1969-1980 (1987), and Next: New Poems (1987).

She also received the National Book Award for Blessing the Boats: New and Selected Poems (1988-2000), and the highly esteemed Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize for lifetime achievement in poetry in 2007.

Two-Headed Woman was both a Pulitzer Prize nominee and a University of Massachusetts Jupiter Prize winner.

Clifton’s eight-part Everett Anderson children’s book series, which educated children on African American heritage led Clifton to earn the Coretta Scott King Award in 1984 for Everett Anderson’s Goodbye.

My Friend Jacob also won the Access to Equality Conference Award for Children’s Literature in “Recognition for Outstanding Treatment of Disabled Children.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Lucille Clifton’s Legacy

In an interview with Antioch Review’s Michael S. Glaser, Clifton states that “writing is a way of continuing to hope … perhaps for me it is a way of remembering I am not alone.” In 1976, she published her memoir, Generations.

Through her writings Clifton hoped “to be seen as a woman whose roots go back to Africa, who tried to honor being human. My inclination is to try to help.”

More about Lucille Clifton

Major works – poetry collections

Good Times (1969)

Good News About the Earth (1972)

An Ordinary Woman (1974)

Two-Headed Woman (1980)

Good Woman: Poems and a Memoir: 1969–1980 (1987)

Next: New Poems (1987)

Quilting: Poems 1987–1990 (1991)

The Book of Light (1993)

The Terrible Stories (1996)

Blessing The Boats: New and Collected Poems 1988–2000 (2000)

Mercy (2004)

Voices, Rochester: BOA Editions, 2008, ISBN 978-1-934414-12-5

The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton, Rochester, BOA Editions, (2012) ISBN 978-1-934414-90-3

Major works – children’s books

Three Wishes

The Boy Who Didn’t Believe In Spring

The Lucky Stone

The Times They Used To Be

All Us Come Cross the Water

My Friend Jacob

Amifika

Sonora the Beautiful

The Black B C’s

The Everett Anderson children’s book series

Everett Anderson’s Goodbye

One of the Problems of Everett Anderson

Everett Anderson’s Friend

Everett Anderson’s Christmas Coming

Everett Anderson’s 1-2-3

Everett Anderson’s Year

Some of the Days of Everett Anderson

Everett Anderson’s Nine Month Long

More information

Poetry Foundation

Britannica

Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Lucille Clifton appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 29, 2020

The Edwardians by Vita Sackville-West (1930)

The Edwardians by Vita Sackville-West, published in 1930, is a novel that critiques the aristocracy of the early 20th century. The work was very much a reflection of the world that Vita grew up in.

As the only child of the aristocratic Victoria and Lionel Edward Sackville-West, a Baron, she had all the duties of a male heir, yet as a female, she wasn’t able to inherit Knole, the castle in which the small family lived.

In The Edwardians, the country estate of Knole castle becomes the fictional Chevron. Within the fictional framework, Vita reproduces in exquisite detail its physical features.

Vita possessed a dual nature where gender was concerned, so it’s not surprising that she chose a male character to represent the position she would have inherited had she been born male.

The Edwardians was first published in England by Hogarth Press, the small publishing company owned and operated by Virginia and Leonard Woolf.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Vita Sackville-West

. . . . . . . . . . .

A brief plot summary of The Edwardians

The main character of the narrative is 19-year-old Sebastian, Duke of Chevron. Due to his youth and initial inexperience, it could be argued that this novel is in the tradition of the Bildungsroman. Sebastian is in line to inherit the country estate once he turns twenty-one, but until such time, it’s overseen by his mother, the widowed Lucy, Dowager Duchess of Chevron.

Sebastian attends Oxford University and on weekends, returns home, where his mother throws lavish parties awash in drink, food, and affairs. As the story gets underway, one of the guests Sebastian encounters is Leonard Anquetil, an adventurer.

Anquetil engages Sebastian in a conversation in which he attempts to convince the young heir of the hypocrisy and shallowness of the social goings-on at Chevron. But Sebastian is unconvinced, or rather doesn’t want to be convinced, since he has freshly embarked on an affair with a married woman, Sylvia Roehamptan, a friend of his mother’s.

When the two are found out, Lady Roehampton ends the affair, wishing to avoid scandal. Undaunted, Sebastian pursues other affairs, and this goes on until he finally capitulates to the idea of marrying a proper young lady and serving in the court of the newly coronated King George V.

Another chance encounter with Anquietil dissuades him from the momentous decision to settle down. It so happens that Anquietil has been seeing Sebastian’s liberated sister, Viola. Sebastian agrees to join the adventurer on the expedition.

It’s equally the plot, the scrutiny of aristocratic life, and the minute details of a castle estate that has made this one of Vita Sackville-West’s most enduring works.

. . . . . . . . . .

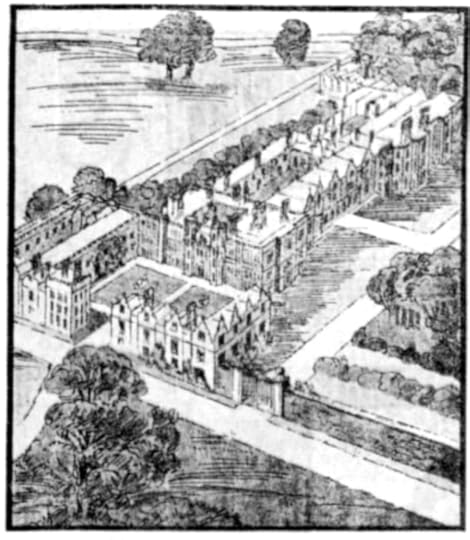

Knole, the model for the fictional Chevron,

is now part of the National Trust in the U.K.

. . . . . . . . . .

“No character in this book is wholly fictitious”

A description of this novel in Vita Sackville-West: Selected Writings (edited by Mary Ann Caws, 2002), makes clear that much in the novel is based on the author’s experiences, and the people closest to her:

“A statement precedes this volume as an author’s note, the contrary of the usual disclaimer about the reality of the depictions in relation to the writer’s imagination:

‘No character in this book is wholly fictitious.’ Beginning on this self-conscious note, the novelist treats herself as a presumably non-generic ‘he.’

‘Among the many problems which beset the novelist, not the least weighty is the choice of the moment at which to begin his novel.’

This hugely successful novel presents a picture of some of the novelist’s own problems. Among them, the protagonist’s attachment to a great house modeled after Knole, a duchess modeled after Vita’s mother, and siblings Sebastian and Viola modeled after Vita herself.

Sebastian’s struggles with life and love, torn between adventure, sin, and conformity to his wealthy upper class expectations and traditions. Most interesting are the descriptions of the house parties and of Sylvia, one of the central female characters, the older woman with whom Sebastian has his first love affair.

On April 19, 1930, The Edwardians was presented as a play at the Richmond Theatre, to great acclaim.”

The Edwardians was well received on both sides of the Atlantic and was a book club selection in both the U.S. and Britain. Here is one such typical review:

A 1930 review of The Edwardians by Vita Sackville-West

From the original review in The Fort Worth Star-Telegram, September 21, 1930: Lament for the lost glories of a house: Historic Knole Castle is the real hero of Vita Sackville-West’s book.

Though a slender, dark, handsome youth wanders petulantly in search of truth through the glittering pages of The Edwardians, Vita Sackville-West’s novel, the real hero of the book is a house that is mysterious, friendly, comforting, ancient, and wise.

Knole Castle has been celebrated in history and poetry as well as in fiction. The home of the Sackvilles was the setting of Orlando, Virginia Woolf’s novel, which has been recognized as a composite portrait of Sackville-West and her ancestors.

A portrait of Knole in the guise of Chevron

It was the subject of Knole and the Sackvilles and now in The Edwardians it is again presented, this time as “Chevron.” Chevron is a thinly disguised yet accurate picture of Knole, with its magnificent park and its seven acres of roof, a gift that Queen Elizabeth presented to her Lord Treasurer, Thomas Sackville, from whom Vita Sackville-West descends.

Knole Castle is said to have 365 rooms, one for every day in the year, seven courts, one for each day of the week, and fifty-two staircases, one for each week.

According to Sackville-West, the main block of Knole dates from the end of the fifteenth century, although there are several earlier outbuildings. The walls are of gray stone, in many places ten and twelve feet thick and most of the rooms are rather small and low. The windows are rich with armorial glass.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

The portrait galleries at Knole

Many of the floors are made of black oak trees sawed in half. The wood walls are hung with countless pictures, the Sackville portraits of ten generations. Miss Sackville-West explains:

“Let them stand each as the prototype of his age, and at the same time as a link to carry on, not only their tradition but also their heredity, and they immediately acquire a significance, a unity.

You have first the grave Elizabethans, Thomas Sackville, with the long, rather melancholy face, emerging from the oval frame above the black clothes and the white wand of the office; you perceive all his severe integrity; you understand the intimidation austerity of the contribution he made to English letters, undoubtedly a fine old man.

You come down to his grandson; he is the Cavalier by Vandyck hanging in the hall, hand on hip, his flame-colored doublet slashed across by the blue of the Garter; this is the man who raised a troop of horses off his own estates and vowed never to cross the threshold of his house into an England governed by the murderers of the King.

You have next the florid, magnificent Charles, the fruit of the Restoration, poet, and patron of poets — prodigal, jovial, and licentious; you have him full length by Sir Godfrey Kneller, in his Garter robes and his enormous wig, his foot and fine calf well thrust forward.

You have him less pompous and more intimate wrapped in a dressing gown of figured silk, the wig replaced by a Hogarthian turban; but it is still the same coarse face, with the heavy jowl and the twinkling eyes, the crony of Rochester and Sedley, the patron and host of Pope and Dryden, Prior and Killigrew.

You come down to the 18th century. You have Gainsborough’s canvas of the beautiful sensitive face of the fickle duke, spoilt, feared, and propitiated by the women of London and Paris, the reputed lover of Marie Antoinette.

You have his son, too fair and pretty a boy, the friend of Byron, killed in the hunting field at the age of twenty-one, the last direct male of a race too prodigal, too amorous, too weak, too indolent and too melancholy.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Edwardians by Vita Sackville-West on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Edwardians: A portrait of a useless and aristocratic society

Like the novels of Edith Wharton, The Edwardians will appeal to many who may fail to catch its point: the intimate portrait of a useless and aristocratic society. Miss Miss Sackville-West herself, however, sees it with commendable balance. She has killed the thing she loved with neither too much ruthlessness nor too much pity; she has simply told the truth.

She deals with a period and class that possessed a certain glamour and charm, and she has let us feel them; but even more forcefully, she has let us feel the emptiness, the triviality, and the wastefulness that went with them.

The Edwardians relates the splendid dying fall of the privileged classes in England during the aimless years before the war. The old order, which persisted so long under Queen Victoria, had changed. But the new had not quite asserted itself: there was no longer a morality, but there was a great emphasis on appearances.

Questioning traditions

What went on in the neighborhood of Grosvenor Square and in the great country houses was all trivial, and much of it, in the social sense immoral, but these people, who cared about so little else, still took care that no breath of scandal should ever reach the bourgeoisie.

Women did not smoke in public or dine alone with men in restaurants, and husband who surprised their wives with lovers did not divorce them. The old dowagers still ruled society; the great bourgeoisie captains of industry still knocked at its doors in vain.

One questioned one’s traditions as never before, but one seldom broke them. It was definitely an age of transition.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

Portrait of a Marriage: Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson

. . . . . . . . .

Introducing Sebastian, Duke of Chevron

Into this meaningless era was born Sebastian, the twelfth duke of his line. His home was Chevron, a magnificent country house with centuries of tradition behind it. Chevron, we are told, is the fictional incarnation of Knole, the home of the Sackville family and the mise-en-scene of another book, Virginia Woolf’s Orlando.

It was Sebastian’s fate to be pulled two ways in life: to hate the triviality of upper-class existence and yet to love Chevron with its charm and beauty and sense of being home. His mother and sister knew of no such indecision: his mother conformed and his sister rebelled.

But Sebastian, unable to make up his mind, went from love affair to love affair, from dissent to acquiescence, and finally decided to marry a very plain young woman from his own set. But he ran into Anquetil, an explorer who long ago had tried to show him how meaningless his life was, and this time, Anquietil was successful. Instead of becoming engaged, Sebastian went off to explore.

A study in manners and social history

As a picture, a study in manners, and a record of social history, The Edwardians could hardly be better. Miss Sackville-West knows her people intimately, she understands them perfectly She reproduces them as a group against a background brilliantly.

Her book is a personally conducted tour into a world from which all but a few would have been rigorously excluded. The guide has point out everything from the family portraits to the kind of china on the dinner table to the upholstery inside the family state coach to the crest on the writing paper.

She can describe the coronation of George V and reveal both its grandeur and its comedy. She can make Chevron seem the most delectable spot in the world and at the same time the most stifling. The details in The Edwardians makes an organized satiric approach unnecessary — it conveys so much that the facts speak for themselves.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Edwardians by Vita Sackville-West (1930) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 22, 2020

8 Fascinating Facts About Lorraine Hansberry

Lorraine Hansberry (1930 – 1965) was an American playwright and author best known for A Raisin in the Sun, a 1959 play that was influenced by her background and upbringing in Chicago. The fascinating facts about Lorraine Hansberry that follow illustrate her growth as an African American woman, activist, and writer.

Though A Raisin in the Sun is the crown jewel in Hansberry’s legacy, she was also known for the plays The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window and Les Blancs.

To Be Young, Gifted and Black was a posthumously produced play and collection of writings that capped a brief and brilliant career. When she died of pancreatic cancer in 1965, she was only 34 years old.

The first Black woman to have a play staged on Broadway

A Raisin in the Sun was the first play written by an African American woman to be produced on Broadway. When she was only 29 years old, Hansberry became the youngest American and the first African-American playwright to win the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for Best Play.

Hansberry commented on her play:

“It is a play that tells the truth about people, Negroes [in the parlance of the time], and life. The thing I tried to show was the many gradations in even one Negro family, the clash of the old and the new, but most of all the unbelievable courage of the Negro people.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Lorraine Hansberry

. . . . . . . . . . .

Her father was a plaintiff in a Supreme Court housing case

Lorraine Hansberry’s father, Carl Augustus Hansberry, was involved in the Supreme Court case. It was previously ruled that African Americans were not allowed to purchase property in the Washington Park subdivision in Chicago, Illinois.

In 1938, after her father bought a house in the south side of Chicago, the family was subject to the wrath of their white neighbors, resulting in U.S. Supreme Court’s Hansberry v. Lee case.

This experience is reflected in Raisin in how unwelcoming the white community was to the Younger family in Clybourne Park. Hansberry’s father died in 1946 when she was only fifteen years old. She was later quoted as saying that “American racism helped kill him.”

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Lorraine Hansberry

. . . . . . . . . .

She came from an accomplished circle of family and friends

The Hansberry family had many friends and relatives that were involved in the arts. W.E.B. Du Bois, the Civil Rights activist, author, sociologist, and historian, and Paul Robeson, the musician and actor, were friends of the Hansberry family.

Hansberry’s uncle, William Leo Hansberry, founded the Howard University African Civilization section of the history department, her cousin Shauneille Perry is an actress and playwright, and her younger relatives, Taye Hansberry is an actress and Aldridge Hansberry is a composer and flutist.

Later, Hansberry would maintain her own close bonds with Du Bois, Robeson, Langston Hughes, and James Baldwin. All mourned her premature death.

The title, A Raisin in the Sun, came from a Langston Hughes poem

The title of Hansberry’s now-iconic play A Raisin In the Sun was inspired by Hughes’ poem “Harlem.” One could argue that the play illustrated the poem’s sentiment:

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from A Raisin in the Sun

. . . . . . . . . .

Nina Simone dedicated a song to her

In 1969, four years after Lorainne Hansberry’s death, Nina Simone wrote a song titled “Young, Gifted, and Black” after being inspired by a talk that Hansberry delivered to college students. Since that time, other artists including Aretha Franklin have covered the song, which begins:

To be young, gifted and black

Oh, what a lovely precious dream

To be young, gifted and black

Open your heart to what I mean

In the whole world you know

There are a million boys and girls

Who are young, gifted and black

And that’s a fact!

Hansberry and Simone had been friends and shared a bond over their interests in social justice and radical politics. also named Lorraine Hansberry the Godmother of her daughter, Lisa Simone.

Hansberry was an advocate for gay rights

Hansberry was a contributor to The Ladder, a predominantly lesbian publication, where she wrote about homophobia and feminism. She even wrote anonymous letters to the publication alluding to her own lesbian relationships.

Princeton Professor Imani Perry, author of Looking for Lorraine, wrote that “she was a feminist before the feminist movement. She identified as a lesbian and thought about LGBT organizing before there was a gay rights movement. She was an anti-colonialist before independence had been won in Africa and the Caribbean.”

Hansberry kept a low profile of her identity as a lesbian.

Hansberry addressed social issues in her writings

Not only did Hansberry address social and racial issues in her novels and plays, but she also wrote articles true to her voice and beliefs for a progressive black journal, Freedom, concerning governmental issues. She explored the issues of colonialism and imperialism through her own lens as well as the female perspective.

Hansberry was invited to meet Robert F. Kennedy (then U.S. Attorney General) in May, 1963 due to the work she had done as a Civil Rights activist, but declined the invitation. She admonished the Kennedy administration to be more active in addressing the problem of segregation in the community.

. . . . . . . . . . .

To Be Young, Gifted and Black

. . . . . . . . . .

James Baldwin was Lorraine Hansberry’s close friend and confidant

Lorraine Hansberry was 28 when she met James Baldwin, 34 at the time. Lorraine believed that the artist’s voice in whatever medium was to be as an agent for social change. That was what formed their bond at the time when Lorraine was developing her own black, feminist, and queer politics.

Both of these talented writers wanted to incorporate themes of race and sexual identity into their stage work, something that was considered quite radical at the time.

James Baldwin wrote the introduction to Hansberry’s biography, To Be Young, Gifted, and Black with an endearing letter to Hansberry titled “Sweet Lorraine.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Norma Brickner is a Journalism and Digital Media major at SUNY-New Paltz.

The post 8 Fascinating Facts About Lorraine Hansberry appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

How Alice Walker Rediscovered Zora Neale Hurston

After discovering, reading, and rereading Zora Neale Hurston’s works, Alice Walker felt as if she knew Hurston personally. By the time of Hurston’s death, most of her considerable body of work was out of print, rarely read or studied. Here we’ll explore how Alice Walker rediscovered Zora Neale Hurston and revived her literary legacy.

Zora Neale Hurston (1891 – 1960) had a dual career as an anthropologist and author, incorporating regional and cultural realism in her short stories, folklore collections, and novels.

Alice Walker (1944 – ) is an activist, novelist, short story writer, and poet best known for the 1982 novel The Color Purple. Works by Walker and Hurston were included in a 1967 anthology of stories. Yet Alice Walker wasn’t very familiar with Zora Neale Hurston at the time.

. . . . . . . . .

More about Zora Neale Hurston

. . . . . . . . . .

Making her mark in the Harlem Renaissance

Hurston was a major name in the Harlem Renaissance movement of the 1920s. In 1937, what would become her best-known novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, was published. Though it was controversial in its time, later generations of readers, especially women, would find its message empowering.

Although the Harlem Renaissance embraced and promoted Black artists and writers, bringing fame to many who participated in it, Zora’s reputation had completely declined by the time of her death in 1960.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Alice Walker

. . . . . . . . . . .

In search of Zora Neale Hurston

It was a few years after Zora’s death that Walker read Their Eyes Were Watching God, which set her on the path of researching Zora Neale Hurston’s life and work.

Walker admired how Hurston embraced Black culture through her literature. Something the two authors share in their writing style is that Their Eyes Were Watching God (and other works) and The Color Purple both use the Black southern vernacular in their characters’ dialogue.

In the essay “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” (first published in Ms. magazine in 1975, later titled “Looking for Zora”) Alice Walker explored Hurston’s hometown of Eatonville, Florida, and came to understand that it was immensely influential to her works.

The influence of Eatonville

Hurston’s father was born into slavery; her mother was born to freed slaves. Having lineage branching towards both slavery and freedom is an intriguing background, and perhaps influenced Zora Neale Hurston’s attitude toward the world’s restricting hierarchy.

Growing up in Eatonville, Florida, a small town with such an intentional Afro-American community, might have caused Hurston to experience culture shock once she realized that in the wider world, she was considered a minority, and “less-than.”

Walker discovered that some characters in Hurston’s works were based on the people in her life. One of them was Jody Stark, who was inspired by Joe Clarke, the first mayor of Eatonville, and one of Hurston’s uncles.

Searching for Zora’s grave

Farther along in her quest, Walker felt drawn to travel to the cemetery where Zora Neale Hurston was buried, the Garden of Heavenly Rest in Fort Pierce, Florida.

Walker wanted to honor the writer who had been such an inspiration, only to discover that Hurston’s unmarked grave had caved in and had been overrun by weeds and snakes. Once Walker was as certain as possible that she’d found the right spot, she purchased a headstone and had it engraved. She observed:

“There are times — and finding Zora’s grave was one of them — when normal responses of grief, horror, and so on, do not make sense because they bear no relation to the depth of emotion that one feels.

It was impossible for me to cry when I saw the field full of weeds where Zora is. Partly this is because I have come to know Zora through her books and she was not a teary person herself; but partly, too, it is because there is a point at which even grief feels absurd.”

. . . . . . . . .

Their Eyes Were Watching God

. . . . . . . . .

Ripe for rediscovery

In Their Eyes Were Watching God, the main character, Janie Crawford, gains her freedom and gains her power after the death of her most-loved husband, Tea-Cake.

This novel challenges societal patriarchy through one African-American woman’s journey of self-discovery. Walker found these ideals and values in Hurston’s literature worthy of being presented to a new generation of readers.

Hurston’s writings seemed ripe for rediscovery in the 1970s, a time when social movements were re-envisioning the relationship between gender and race, and searching for a feminine identity not defined by a patriarchal society.

Her writings, especially Their Eyes Were Watching God, were controversial in their time, partly due to the use of Black southern vernacular. Some critics felt that this served only to ridicule the black community and provide a source of entertainment for white readers. But in reality, Hurston was expressing affection for the people she grew up with.

In Walker’s collection of essays, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens (1983), she writes as if she is the metaphorical daughter of Hurston and other great African American female writers before her.

Through their struggles of slavery, oppression, and sexually exploitation, they paved the way for authors and poets who came after them. Certainly, many of today’s African American women authors stand on the shoulders of Zora Neale Hurston.

“Zora Neale Hurston: A Genius of the South” — The inscription that Alice Walker provided for the gravestone she erected says it all.

. . . . . . . . . .

In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens by Alice Walker

on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Further reading and sources

“In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” by Alice Walker

Crafting a Voice for Black Culture (NPR)

“Black Matrilineage: The case of Alice Walker and Zora Neale Hurston” by Dianne F. Sadoff, University of Chicago Press Journals

Zora Neale Hurston … “A Genius of the South”

Norma Brickner is a Journalism and Digital Media major at SUNY-New Paltz.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post How Alice Walker Rediscovered Zora Neale Hurston appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 21, 2020

Quotes from Elizabeth Taylor’s Fiction: Glimpsing the British Novelist’s Gifts

Elizabeth Taylor (1912 – 1975) knew from a young age that she wanted to be a novelist — to be clear, this isn’t in reference to the renowned actress, but to the prolific British author. In the following selection of quotes from Elizabeth Taylor’s fiction, we get a glimpse of her literary gifts.

Her first novel, At Mrs Lippincote’s, was published in 1945. Here, Roddy, an RAF officer has been stationed in a small town in southern England and, now, his wife and son and cousin have joined him in what used to be Mrs Lippincote’s house. Mr and Mrs Lippincote have died, but the Davenant family is building a life together.

Her last novel, Blaming, was published posthumously in 1976. Here, Amy is unexpectedly widowed in Istanbul and Martha helps her travel home to England. Sharing this intense experience suggests a solid foundation for a friendship, but when the women return to England, maintaining that tie is a challenge.

These are everyday events in ordinary people’s lives: throughout her twelve novels and sixty-five short stories, Elizabeth Taylor has been inspired and fueled by such events.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Elizabeth Taylor

. . . . . . . . . . .

Character

Taylor’s female characters are often at the heart of her stories, and they remain distinct and memorable creations. Consider how different readers’ impressions are of the following three women in her stories: Julia’s observations of the Wing Commander’s wife, Angel, and Camilla.

Twittering, gazing and supplanting: Taylor’s observations are succinct and evocative. We feel like we know these characters, sometimes more intimately than they know themselves:

“She twitters. Like all the wives of somber men, she froths and seethes and bubbles, keeps herself at boiling-point ready for emergencies.” (At Mrs Lippincote’s)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Angel, at first shocked, soon grew used, from constant looking, to seeing only what she chose, especially the narrowness of her bare hand with its emerald ring. She would gaze at this detail for a long time each day.” (Angel)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“She made the mistake always of thinking people would like what she herself liked; she put herself too much in other people’s places, instead of allowing them to stay there themselves.” (A Wreath of Roses)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Here are even more quotes by Elizabeth Taylor, British novelist

. . . . . . . . . . .

The senses

Another way that Taylor involves readers in her stories about ordinary lives is to evoke simple sensory details. Our noses and our fingertips are engaged—we feel the prickling and the slicing. Elizabeth Taylor’s use of detail is specific and astute:

“The smell was suffocating. Cats had wetted the carpets for centuries, Camilla decided. Bushels of onions had been fried. No one had washed, or opened a window.” (A Wreath of Roses)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“The sandwiches they had ordered were now put in front of them, and Nell lifted a corner of one of hers and peered short-sightedly inside – hard-boiled egg, sliced, with dark rings round the yolk, a scattering of cress, black seeds as well.” (The Wedding Group)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“He thought of Emily lying under the spell of her alien beauty and Rose’s devotion enclosing her like a thicket of briars.” (The Sleeping Beauty)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“The train ripped through the sullen landscape like scissors through calico….” (Palladian)

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Relationships, with ourselves and one another

Even when she evokes more universal experiences, she has a way of illuminating the darker corners of human experiences. Richard’s observation is true:

“We are all like icebergs; underneath where the greater parts are hidden it is dark and unreachable.” (A Wreath of Roses)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Consider how unconventional and varied are two of her representations of mothering:

“Some sons may have a picture of their mother knitting by the fireside — but David’s was of Midge with glass in hand, railing against something. The railing was hardly ever seriously meant. It was intended to interest, or amuse, or fill in a gap in the conversation, which was something Midge deplored.” (The Wedding Group)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Flora sat down in the old rocking-chair – her mother’s – and began to unbutton her blouse. Alice pushed her tear-wet face against her and her crying ceased; but, even with her mouth fastened furiously to her mother’s breast, she still made little hiccupping noises, the echoes of sobs, as if resentment lingered.” (The Soul of Kindness)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Taylor’s characters can be loving and enchanting, as well as railing and resentful (although when one character observes another and assumes an understanding of them, this often says more about the observer than the observed). Darkness complements the light in her storytelling.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Darkness

“Back along the suburban streets with the admired privet hedges, the houses with their bowed and bayed windows, the skeleton laburnums which in spring would give such pleasure. Gardens were all in darkness now, but television lit up rooms, or shadows passed behind drawn curtains. Sometimes light sprang up in bedrooms.” (Blaming)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“… she dreamed through the lonely evenings, closing her eyes to create [as a novelist] the darkness where Paradise House could take shape, embellished and enlarged day after day — with colonnades and cupolas, archways and flights of steps….” (Angel)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Whereas in the centre of the earth, in the heart of life in the core of even everyday things is there not violence, with flames wheeling, turmoil, pain, chaos?” (A Wreath of Roses)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“She thought of the river and the prison and then of the Abbey ruins, imagining a dark, Gothic, ivy-covered place in which, under some crumbling archway, she might meet [the Wing Commander], with the bats swinging at shoulder height and a white owl hooting above.” (At Mrs Lippincote’s)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Fans of the Brontë sisters — Anne, Charlotte, and Emily —will find many allusions to their work throughout Elizabeth Taylor’s writing. These references contribute to these stories’ timeless feel, their enduring relevance across the decades.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Time

How Elizabeth Taylor’s characters experience time passing is often revealing of the state of their minds and hearts:

“At other tables sat a few other elderly ladies looking, to Mrs Palfrey, as if they had been sitting there for years. They were waiting patiently for the celery soup, hands folded in laps and eyes dreamy.” (Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“After their walk in the woods, Harriet faced the day’s page uncertainly. There was either far too much space or only one-hundredth part enough. Time had expanded and contracted abnormally. That morning and all her childhood seemed the same distance away.” (A Game of Hide and Seek)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Those games, to outwit time and distance, all lovers play – the rose that the hand touched, the kisses on paper: so that the earth is spun about by invisible threads, a tangle of enchantment.” (The Sleeping Beauty)

. . . . . . . . . . .

As astutely as Taylor represents her characters broader understanding of time (and mortality and other related themes), she is just as talented in representing the present. She manages the mechanics of scenes and dialogue in them so deftly that it appears effortless.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Characters’ conversations

Dialogue can be used to build characterization, as with this conversation between Vinny and Emily:

“’I cannot think why you love me,’ he said, as all lovers say; but with more anxiety in his voice than is usual.

‘Oh, I am nothing without you,’ she said. ‘I should not know what to be. I feel as if you had invented me. I watch you inventing me, week after week.’” (The Sleeping Beauty)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Sometimes, however, the dialogue is simply part of constructing a scene. And, when it comes to children, Elizabeth Taylor’s depictions are tender and cruel — in short, realistic. Consider this passage, from a novel preoccupied with the theme of loss and bereavement, both blatantly and delicately exploring the matter at hand, through a discussion between two children:

“’Not everyone goes to heaven,’ Dora, who was older said, ‘Egyptian mummies didn’t go. Or stuffed fishes.’

‘No fishes never go,’ Isobel agreed ‘sometimes I eat them. Chickens can’t go, nor.’

‘I don’t really know about heaven,’ Dora said in her considered way. ‘We haven’t done that at school yet. But I know they must go somewhere, or we’d be full up here. People coming and going all the time.’” (Blaming)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Evidently, in the face of darkness, Elizabeth Taylor’s storytelling has a light touch. There are many humorous moments in her work, as with Patrick’s suggestion to Flora, in The Soul of Kindness: “One can’t make much of a career out of having tea with married women.” They are numerous, but usually most effective in the context of the story.

Often readers who select just one Elizabeth Taylor novel, on the advice of another reader, return for more. Her writing is of a consistently high-quality. It’s easy to imagine that she viewed the world around her with the kind of attention and dedication that Mrs Secretan describes in this scene:

“Mrs Secretan had spent some happy hours renovating Flora’s old dolls’ house for her future grandchild. She had made new curtains and bed-clothes and had cleaned the plaster food, which was set out on the table – a lobster, a pink ham, a dish of peas and a charlotte russe. A woolly cat lay in front of the painted fire. Dolls sat stiffly in chairs: those that could not bend at all had been put to bed in their clothes or were propped against furniture.” (The Soul of Kindness)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Just as the Davenant family moves into Mrs Lippincote’s home, just as Mrs Secretan creates a dolls’ house for her daughter and her granddaughter, Elizabeth Taylor prepares the scenes in her novels meticulously. Her characters move as needs must, whether comfortable in front of the fire or propped awkwardly in a corner, and then she makes us care about them through the small ceremonies of their daily lives.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Taylor page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes from Elizabeth Taylor’s Fiction: Glimpsing the British Novelist’s Gifts appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 20, 2020

Quotes by British Novelist Elizabeth Taylor on Love and Loneliness, Beauty and Marriage

A unique voice comes through in the following selection of quotes by British author Elizabeth Taylor (not to be confused with the actress of the same name) on love, loneliness, beauty, and marriage from her novels and short stories.

Elizabeth Taylor (1912 – 1975) knew from a young age that she wanted to be a novelist. She received high marks in English as a student and, after graduation, borrowed books through the Boots Library system which informed her natural storytelling abilities: works by of Jane Austen, Anton Chekhov, Henry Fielding, E.M. Forster, Samuel Richardson, Ivan Turgenev and Virginia Woolf.

She found inspiration for twelve novels and sixty-five short stories in the everyday lives of ordinary people. She described it like this to her American publisher:

“People are my only adventures and I hope never to have any others … to be ‘ordinary’ and live among ‘ordinary’ people (though no one is really that) is the only way that I can write, and I expect that this limits my range; but I have no gift for anything else.”

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Elizabeth Taylor

. . . . . . . . . .

Relationships are at the heart of her fiction, long- and short-form. Some of her characters come together, while others fall apart, and others observe dramatic changes from the margins. Various themes resurface, in and between works, and Elizabeth Taylor devotees vicariously explore human contradictions as they explore her stories.

Not surprisingly, love is a common theme. Many of her more remarkable observations consider the aspects of love which are overlooked (or denied) in formulaic stories. Which is to say that they are occasionally celebratory but, more often, complicated—sometimes even melancholy.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Love

Although willing to acknowledge, even inhabit, the darker recesses of human experience, her novels and stories do not dwell in these environs. Many of her characters, however, as in the novels of Barbara Pym, do feel markedly alone. (Pym was an admirer of Taylor’s fiction too.)

“Don’t fuss, dear girl. At your age one has to be in love with someone, and Robert does very well for the time being. Perhaps at every age one has to be in love with someone, but when one is young it is difficult to decide whom. Later one becomes more stable. I fell in love with all sorts of unsuitable people—very worrying for one’s mother.” (“Hester Lilly”)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Seeing one face continually in crowds is one of the minor annoyances of being in love.” (A Game of Hide and Seek)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“The story he could not have distinguished from many others so much the same – the humbling by love of a too rebellious young woman – and it was drawing towards its reassuring conclusion that, even if she triumphs over the rigours of the jungle, no woman escapes the doom of her sexuality: a satisfactory conclusion; no surprise to anyone.” (The Sleeping Beauty)

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Loneliness

“When she saw the light swinging over the water she felt terror and desolation, the approach of the long evening through which she must coax herself with cups of tea, a letter to her brother in Canada or this piece of knitting she had dropped to the floor as she leant to the pane to watch Bertram, the harsh lace curtain against her cheek, the cottony, dusty smell of it setting her teeth on edge.” (A View of the Harbour)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“She could see then, with Etta’s eyes, their own dark, narrow house, and she thought of the lonely hours she spent there reading on days of imprisoning rain.” (“Girl Reading”)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“He imagined home having the same time as England. He would have felt quite lost to his loved ones if when he woke in the night, he could not be sure that they were lying in darkness too and, when his own London morning came, theirs also came, the sun streamed through the cracks of their hut in shanty-town, and the little girls began to chirp and skip about.” (“Tall Boy”)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“When it was dark she pinned the curtains together again and sat down at the table, simply staring in front of her; at the back of her mind, listening. In the warm living-room of her sister’s house, the children in dressing-gowns would be eating their supper by the fire; Roy, home from a football match, would be lying back in his chair. Their faces would be turned intently to the blue-white shifting screen of a television.” (“The Thames Spread Out”)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“’You’ll have the company of others like you,’ his neighbours had told him. This was not so. He found himself in a society, whose existence he had never, in his old egotism, contemplated and whose ways soon lowered his vitality. He had nothing in common with these faded seamstresses; the prophet-like lay-preacher; an old piano-tuner who believed he was the reincarnation of Beethoven; elderly people who had lived more than half a dim life-time in dark drapers’ shops in country towns.” (“Spry Old Character”)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Once he saw a large cactus-plant in a flower-shop window. From one unpromising, barbed shoot had sprung a huge, glowering bloom. It looked solitary and incongruous, a freakish accident; and he was reminded of Angel.” (Angel)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“It is seldom safe to confide in lonely people. Their very loneliness requires the importance of making known the confidence, at hinting at its existence and source, if not actually divulging it; better to trust in busy, popular people, who have no time for betraying one and no personal need to do so.” (At Mrs. Lippincote’s)

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Beauty

Even while describing or musing on the idea of beauty, Elizabeth Taylor often considers relationships between concepts, as though they are relationships between people.

Beauty is an illusion, a boon, a risk: a complex way of examining the concept. Some characters reap benefits from their beauty, others struggle to reorient themselves with their beauty having worked into an equation that they hadn’t recognized as part of an exchange system.

“Ugliness has the extra power of making beauty seem unreal, a service beauty seems rarely able to return.” (A Wreath of Roses)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“She would know then that she was in her own setting and had no reason for ever finding herself elsewhere; know moreover that she was bereft of the power to rescue herself, the brains or the beauty by which other young women made their escape.” (Angel)

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Marriage

As another system of exchange, marriage is a key element of many characters’ lives in Elizabeth Taylor’s fiction. Whether the bond between wife and husband is a desirable or undesirable state, be it cinched or slack, marriage is under the microscope in her long and short tales.

This sequence of quotations about marriage illustrates the kind of gradient that readers can expect from Elizabeth Taylor’s fiction. In some cases, marriage is a source of joy; in other instances, marriage is a destructive force.

To complicate matters further, her characters’ experience of marriage alters depending on access to varying levels of privilege and how realistic their expectations are. In every instance, however, there is an element of risk.

Take Vinny, in The Sleeping Beauty, for instance: “We can afford to be undignified only when we are young,” he thought, waiting in the street, staring at his dusty shoes. “And, love, alas, has so much indignity attached to it.”

Elizabeth Taylor’s characters are often undignified, either in their own eyes or another’s: that’s what makes them relatable. That’s what makes these grand overarching themes—of love and loneliness, beauty and marriage—so accessible in her fiction.

“It makes very little difference to me. I am a parasite. I follow my man around like a piece of luggage or part of a traveling harem. He is under contract to provide for me, but where he does so is for him to decide.” (At Mrs. Lippincote’s)

. . . . . . . . . .

“And marriage changes us quite. How can we enter marriage and remain the same? The circles of our existences become concentric.” (A Wreath of Roses)

. . . . . . . . . .

“They became more and more to one another and, in the end, the perfect marriage they had created was like a work of art. People are sorry for brides who lose their husbands early, from some accident or war. And they should be sorry, Mrs Palfrey thought. But the other thing is worse.” (Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Without discussing where they should sit, they [the married couple] moved apart from the others and spread towels out on the sand. Bunny removed his hat and shirt, and went trotting down to the sea, his crooked arms jerking back and forth like a long-distance runner’s.” (“In the Sun”)

. . . . . . . . . .

“He was a man utterly, bewilderedly at sea. His married life had been too much for him, with so much in it that he could not understand.” (“The Blush”)

. . . . . . . . . .

“‘Marriage does not solve mysteries,’ she thought. ‘It creates and deepens them.’ The two of them being shut up physically in this dark space, yet locked away for ever from one another, was oppressive. Both were edgy.” (A Game of Hide and Seek)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Just imagine, as a child, being told that some day one will have to belong to some other person, so finally that only death could put an end to it. You couldn’t blame the child for bursting into tears at the idea. To be under the same roof till kingdom come.” (The Soul of Kindness)

. . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Taylor page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Quotes by British Novelist Elizabeth Taylor on Love and Loneliness, Beauty and Marriage appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

“Désirée’s Baby” by Kate Chopin: Motherhood and Miscegenation in 19th-Century America

This analysis of “Désirée’s Baby,” an 1893 short story by Kate Chopin, explores the narrative of miscegenation and motherhood in the antebellum American South. Chopin is best known for the groundbreaking classic novella The Awakening (1899).

Désirée, a young woman adopted as a child, is married to a plantation owner named Armaud. She is startled when she suddenly realizes that their baby is of a darker complexion than her own and her husband’s.

Chopin uses the setting of Louisiana to create a delicate yet hostile environment for a disillusioned young mother. Motherhood in this era can be deemed sensitive and complicated, since Désirée lives in a time when its treatment is based on ethnicity and social stratification.

The setting not only provides an environment for the characters in the story, but also advances each to their individual downfalls.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Read the full text of “Désirée’s Baby”

. . . . . . . . . . .

A complicated maternal history

Désirée unknowingly has a complicated history and relationship with motherhood through her own two mothers. Désirée is a child of adoption; the history and relationship between her biological mother is intangible to her, and the readers.

Without or with intention, Chopin makes no clear note of Désirée’s mother. In fact, when Désirée is found as a baby by Monsieur Valmode, she says she utters the words, “Dada.” On the other hand, Désirée’s adoptive parents seem to be more than grateful for her spontaneous arrival.

Conflictingly, her adoptive mother, Madame Valmode, spoils Désirée and sees her as a gift from God: “In time Madame Valmode abandoned every speculation but the one that Désirée had been sent to her by a beneficent Providence.”

Although Désirée is portrayed as having a functional and happy childhood, her ideas surrounding motherhood are misconstrued from a young age, due to her biological mother’s abandonment.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Kate Chopin

. . . . . . . . . . .

La Blanche: A complicating factor

These factors cause Désirée to be confused as to what the maternal role should be, especially since in the era of slavery, Southern white women often delegated the responsibilities of motherhood to their female house slaves.

One could think of female house slaves as precursors to nannies and maids, but they had a greater amount of responsibilities imposed on them.

In this story, for example, La Blanche is a house slave who takes care of her three young boys along with Désirée’s baby. While the slave’s children are hinted as being Armaud’s, that doesn’t ease the struggles of tending to four young children.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: Full text of The Awakening by Kate Chopin

. . . . . . . . . . .

A shocking revelation

The tenderness with which Désirée goes about raising her own child takes a turn when she realizes her child is the same skin color as La Blanche’s children: “When the baby was about three months old, Désirée awoke one day to the conviction that there was something in the air menacing her peace.”

Chopin foreshadows the trepidation Désirée will soon encounter when she realizes her child’s origins.

Furthermore, once Désirée has come to the realization that her child is a product of miscegenation, she becomes maniacal, and her husband Armaud begins to feel animosity towards her and his child. The question arises in the reader’s mind as to why Armaud is resentful towards his wife but does not have the same feelings towards La Blanche.

The differences between the two are their social status and racial makeup. Also, Désirée hasn’t been held to the same standard of motherhood as La Blanche has. La Blanche is not just a mother in Armaud’s eyes but also a worker, objectified for profit and use.

When she turns to her husband for empathy, she is unexpectedly greeted with rage: “Armaud,” she panted once more, clutching his arm, “look at our child. What does it mean? Tell me,” she begs of him.

In response he tells her, “[T]hat the child is not white; it means that you are not white.” Armaud immediately assumes and blames Désirée for the child’s African descent.

A devastating decision

This accusation proves overwhelming for Désirée (the confusion of her child and now her own origins), and leads to what appears to be a demise; she took the child and “disappeared among the reeds and willows that grew thick along the banks of the deep, sluggish bayou; and she did not come back again.”

Désirée’s final act as a mother to her child can be seen as selfish and destructive, but it’s also a gesture of protection against the racism of the antebellum era.

The mendacity of Armaud and the naïveté in which Désirée was raised produced devastating consequences on the experience of motherhood in the antebellum South, where strict social and racial strictures reigned, and endured long past the end of slavery.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Oona Uishama Narvaez. Oona is an ardent writer from El Paso, Texas. She is a passionate reader currently pursuing a degree in creative writing.

The post “Désirée’s Baby” by Kate Chopin: Motherhood and Miscegenation in 19th-Century America appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 15, 2020

Lilacs by Amy Lowell (1922) — the poet’s own favorite

Amy Lowell (1874 – 1925), an influential yet undervalued American poet, was an energetic evangelist of the art of poetry for all her adult life. Here is presented “Lilacs,” said to be the one of the poet’s own favorites, and among the poems she recited most often in her many public readings.

First published first published in the New York Evening Post on September 18, 1920, “Lilacs” went on to be included in a 1922 modernist poetry anthology.

Finally, “Lilacs” became part of Lowell’s 1925 collection What’s O’ Clock, which received the Pulitzer Prize the following year. Unfortunately, the poet died before receiving this honor. She was only 51, having suffered from poor health for some time.

Prior to the publication of What’s O’Clock, Lowell had published the collections A Dome of Many-Coloured Glass (1912) Sword Blades and Poppy Seed (1914), Men, Women and Ghosts (1916), Can Grande’s Castle (1918), Pictures of the Floating World (1919), and more.

Lowell’s poetry was in the genre of “imagism,” which is pretty much what it sounds like, and of which “Lilacs” is a good illustration. According to her own definition, imagism is defined as the “concentration is of the very essence of poetry” and aimed to “produce poetry that is hard and clear, never blurred nor indefinite.”

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Amy Lowell

. . . . . . . . . .

Who better to present Lowell’s philosophy on the creation of poetry than the poet herself; she wrote in the introduction to Can Grande’s Castle:

“I wish to state my firm belief that poetry should not try to teach, that it should exist simply because it is a created beauty, even if sometimes the beauty of a gothic grotesque.