Nava Atlas's Blog, page 51

August 27, 2020

Jasmine by Bharati Mukherjee (1989)

Bharati Mukherjee (1940 – 2017), who made her life in America, has written many books about the immigrant experience. Jasmine, published in 1989, is probably among the best as it picks up on the transition in a very nuanced fashion, not sparing us the horrors, either.

It is quite likely that the author’s personal experiences have contributed to the deep insights that can grab readers and keep them riveted. Mukherjee was born in what is now called Kolkata (Calcutta at the time she was born when under Indian rule). In the course of her prolific career, she wrote many works of fiction and nonfiction and taught at a number of American universities.

Changing names, transforming identities

The protagonist of Jasmine starts her life with the name Jyoti, then adopts the name Jasmine, when her husband lovingly rechristens her. Finally, she becomes Jane, after making the move to America. The names that Bharati chooses for her character become synonymous with the transformations within and without, as she is tossed from one life-changing reality to another; each one stripping her of an identity.

The story starts with Jyoti recalling her life in a small village in Punjab in the North of India where an old astrologer predicts that she will be widowed and then exiled from her own country. But she is Jane now, age twenty-four and living in Baden, Elsa Country, Iowa, with her partner, Bud Ripplemeyer, who is a much-older divorcee and wheelchair-bound after a shooting accident.

Jane is carrying Bud’s child and he would like for them to be married, but she resists. She has already seen tragedy, having been widowed at seventeen. She lost a husband who loved her dearly and whose dream it was to move to Florida in the U.S. It is to fulfill his dream that she makes the long journey out of India, suffering trials and tribulations along the way.

. . . . . . . . .

Bharati Mukherjee

. . . . . . . . . .

Adapting to American life

Modern notions in India of the 1970s are also revealed through the views of Prakash, Jasmine’s futuristic husband who believed, “love was letting go. Independence, self-reliance.” He also believed that to have a “real life,” they had to go to America.

The author uses the first-person and several flashbacks as the story unfolds. As much as Jane attempts to understand the American ways, she brings a bit of India into the lives of the people around. She writes, “They get disappointed if there’s not something Indian on the table” and about how a farmer in the vicinity helps her plant Indian herbs like coriander, fenugreek, and “five kinds of chili peppers.”

The Asian transformation has made Bud “reckless and emotional,” which also has him adopt a teenage Vietnamese boy to “make up for fifty years of selfishness.”

Quite often across the narrative, one finds Jane holding things back, “I have to be careful about nearly everything I say.” Original perspectives also come into play as to why she finds herself hoarding water in all the used-up receptacles around the house in Baden. Her mind wanders back to “water famines in Hasnapur, how at the dried-out well, docile women turned savage for the last muddy bucketful.”

The author’s problems with her adopted country also reveal themselves in the narrative as when she writes, “this country has so many ways of humiliating, of disappointing.” Jane has to accept terms like she is a “dark-haired girl’ or has a “darkish complexion.”

But, even she has to admit that when she is hired to work as an au pair with the Taylor family in New York, they are “democratic” in the way that they treat her, providing her a room to herself, fixed working hours and substantial wages.

It may also interest readers to know that whilst Bharati Mukherjee wrote of hyphenated identities, she always fought shy of that label saying, “I am American, not an Asian-American.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Jasmine by Bharati Mukherjee on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Despite a hint of fatalism, a satisfying ending

The clash of philosophical beliefs also unfurl in Jasmine when Jane tries to explain to Taylor, “a whole life’s mission might be to move a flowerpot from one table to another,” and he replies, “I couldn’t live in a world like yours … If rearranging a particle of dust is as important as discovering relativity, that’s a formula for total anarchy. Total futility. Total fatalism. Where’s the incentive to do anything?”

Despite the hint at fatalism, Jane tells herself, “I do believe that extraordinary events can jar the needle arm, jump tracks, rip across incarnations, and deposit a life into a groove that was not prepared to receive it.”

And finally, the happy but unexpected ending, when Jane makes peace with her foretold destiny and whispers an imagined rejoinder to the astrologer, “Watch me reposition the stars.”

. . . . . . . . . .

RELATED CONTENT BY MELANIE KUMAR

10 Classic Indian Women Authors

Remembering Meena Alexander, Indian Poet & Scholar

A House with Four Rooms by Rumer Godden

Melanie P. Kumar is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Jasmine by Bharati Mukherjee (1989) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 26, 2020

A Selection of 10 Poems by Charlotte Brontë

The Brontë sisters — Charlotte, Emily, and Anne — literary geniuses all, are best known for their classic novels, but each was a poet in her own right. Though Emily’s has come to be known as the best among their poetic works, poems by Charlotte Brontë are more than meriting of a consideration.

Charlotte is best known for Jane Eyre (1847) and also wrote Shirley (1849) and Villette (1853). Before attempting to publish novels, Charlotte undertook the task of finding a home for a collaborative book of poems, thinking it would be a good stepping stone (it wasn’t, as it turned out). The sisters took masculine, or at least indeterminate, noms de plume. In Charlotte’s words:

“We had very early cherished the dream of one day becoming authors. This dream, never relinquished even when distance divided and absorbing tasks occupied us, now suddenly acquired strength and consistency: it took the character of a resolve. We agreed to arrange a small section of our poems, and, if possible, get them printed.

… The book was printed: it is scarcely known, was published and advertised at the sisters’ own expense and sold two copies) and all of it that merits to be known are the poems of Ellis Bell.”

The resulting book, The Poems of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, published in 1846 at the sisters’ own expense, sold exactly two copies. Charlotte didn’t think much of her own poetry, nor apparently that of Anne’s, recognizing even then that Emily (who went by Ellis) had the true poetic talent of the trio. Find out more about the Brontë sisters’ path to publication.

Of Charlotte’s poetic work, The Poetry Foundation observes:

“Like her contemporary Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Brontë experimented with the poetic forms that became the characteristic modes of the Victorian period—the long narrative poem and the dramatic monologue—but unlike Browning, Brontë gave up writing poetry after the success ofJane Eyre.

… Brontë’s decision to abandon poetry for novel writing exemplifies the dramatic shift in literary tastes and the marketability of literary genres—from poetry to prose fiction—that occurred in the 1830s and 1840s.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Charlotte Brontë

. . . . . . . . . . .

A selection of poems by Charlotte Brontë

The first seven poems in this selection are from The Poems of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. The poems reprinted here are the shortest of her works in this book; the others are nearly epic in length. You can read a later edition of the book, with an addendum by Charlotte, on Project Gutenberg.

“Speak of the North ! A Lonely Moor” is the 8th poem in the following selection; it’s not known exactly when Charlotte wrote it. And the last two are sad tributes to her sisters Emily and Anne, who died within months of one another at ages thirty and twenty-nine, respectively.

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy: 5 Poems by Emily Brontë

. . . . . . . . . .

Life

Life, believe, is not a dream

So dark as sages say;

Oft a little morning rain

Foretells a pleasant day.

Sometimes there are clouds of gloom,

But these are transient all;

If the shower will make the roses bloom,

O why lament its fall?

Rapidly, merrily,

Life’s sunny hours flit by,

Gratefully, cheerily,

Enjoy them as they fly!

What though Death at times steps in

And calls our Best away?

What though sorrow seems to win,

O’er hope, a heavy sway?

Yet hope again elastic springs,

Unconquered, though she fell;

Still buoyant are her golden wings,

Still strong to bear us well.

Manfully, fearlessly,

The day of trial bear,

For gloriously, victoriously,

Can courage quell despair!

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Letter

What is she writing? Watch her now,

How fast her fingers move!

How eagerly her youthful brow

Is bent in thought above!

Her long curls, drooping, shade the light,

She puts them quick aside,

Nor knows that band of crystals bright,

Her hasty touch untied.

It slips down her silken dress,

Falls glittering at her feet;

Unmarked it falls, for she no less

Pursues her labour sweet.

The very loveliest hour that shines,

Is in that deep blue sky;

The golden sun of June declines,

It has not caught her eye.

The cheerful lawn, and unclosed gate,

The white road, far away,

In vain for her light footsteps wait,

She comes not forth to-day.

There is an open door of glass

Close by that lady’s chair,

From thence, to slopes of messy grass,

Descends a marble stair.

Tall plants of bright and spicy bloom

Around the threshold grow;

Their leaves and blossoms shade the room

From that sun’s deepening glow.

Why does she not a moment glance

Between the clustering flowers,

And mark in heaven the radiant dance

Of evening’s rosy hours?

O look again! Still fixed her eye,

Unsmiling, earnest, still,

And fast her pen and fingers fly,

Urged by her eager will.

Her soul is in th’absorbing task;

To whom, then, doth she write?

Nay, watch her still more closely, ask

Her own eyes’ serious light;

Where do they turn, as now her pen

Hangs o’er th’unfinished line?

Whence fell the tearful gleam that then

Did in their dark spheres shine?

The summer-parlour looks so dark,

When from that sky you turn,

And from th’expanse of that green park,

You scarce may aught discern.

Yet, o’er the piles of porcelain rare,

O’er flower-stand, couch, and vase,

Sloped, as if leaning on the air,

One picture meets the gaze.

‘Tis there she turns; you may not see

Distinct, what form defines

The clouded mass of mystery

Yon broad gold frame confines.

But look again; inured to shade

Your eyes now faintly trace

A stalwart form, a massive head,

A firm, determined face.

Black Spanish locks, a sunburnt cheek

A brow high, broad, and white,

Where every furrow seems to speak

Of mind and moral might.

Is that her god? I cannot tell;

Her eye a moment met

Th’impending picture, then it fell

Darkened and dimmed and wet.

A moment more, her task is done,

And sealed the letter lies;

And now, towards the setting sun

She turns her tearful eyes.

Those tears flow over, wonder not,

For by the inscription see

In what a strange and distant spot

Her heart of hearts must be!

Three seas and many a league of land

That letter must pass o’er,

Ere read by him to whose loved hand

‘Tis sent from England’s shore.

Remote colonial wilds detain

Her husband, loved though stern;

She, ‘mid that smiling English scene,

Weeps for his wished return.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Passion

Some have won a wild delight,

By daring wilder sorrow;

Could I gain thy love to-night,

I’d hazard death to-morrow.

Could the battle-struggle earn

One kind glance from thine eye,

How this withering heart would burn,

The heady fight to try!

Welcome nights of broken sleep,

And days of carnage cold,

Could I deem that thou wouldst weep

To hear my perils told.

Tell me, if with wandering bands

I roam full far away,

Wilt thou to those distant lands

In spirit ever stray?

Wild, long, a trumpet sounds afar;

Bid me—bid me go

Where Seik and Briton meet in war,

On Indian Sutlej’s flow.

Blood has dyed the Sutlej’s waves

With scarlet stain, I know;

Indus’ borders yawn with graves,

Yet, command me go!

Though rank and high the holocaust

Of nations steams to heaven,

Glad I’d join the death-doomed host,

Were but the mandate given.

Passion’s strength should nerve my arm,

Its ardour stir my life,

Till human force to that dread charm

Should yield and sink in wild alarm,

Like trees to tempest-strife.

If, hot from war, I seek thy love,

Darest thou turn aside?

Darest thou then my fire reprove,

By scorn, and maddening pride?

No—my will shall yet control

Thy will, so high and free,

And love shall tame that haughty soul—

Yes—tenderest love for me.

I’ll read my triumph in thine eyes,

Behold, and prove the change;

Then leave, perchance, my noble prize,

Once more in arms to range.

I’d die when all the foam is up,

The bright wine sparkling high;

Nor wait till in the exhausted cup

Life’s dull dregs only lie.

Then Love thus crowned with sweet reward,

Hope blest with fulness large,

I’d mount the saddle, draw the sword,

And perish in the charge!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Evening Solace

The human heart has hidden treasures,

In secret kept, in silence sealed;—

The thoughts, the hopes, the dreams, the pleasures,

Whose charms were broken if revealed.

And days may pass in gay confusion,

And nights in rosy riot fly,

While, lost in Fame’s or Wealth’s illusion,

The memory of the Past may die.

But there are hours of lonely musing,

Such as in evening silence come,

When, soft as birds their pinions closing,

The heart’s best feelings gather home.

Then in our souls there seems to languish

A tender grief that is not woe;

And thoughts that once wrung groans of anguish

Now cause but some mild tears to flow.

And feelings, once as strong as passions,

Float softly back—a faded dream;

Our own sharp griefs and wild sensations,

The tale of others’ sufferings seem.

Oh! when the heart is freshly bleeding,

How longs it for that time to be,

When, through the mist of years receding,

Its woes but live in reverie!

And it can dwell on moonlight glimmer,

On evening shade and loneliness;

And, while the sky grows dim and dimmer,

Feel no untold and strange distress—

Only a deeper impulse given

By lonely hour and darkened room,

To solemn thoughts that soar to heaven

Seeking a life and world to come.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Parting

There’s no use in weeping,

Though we are condemned to part:

There’s such a thing as keeping

A remembrance in one’s heart:

There’s such a thing as dwelling

On the thought ourselves have nursed,

And with scorn and courage telling

The world to do its worst.

We’ll not let its follies grieve us,

We’ll just take them as they come;

And then every day will leave us

A merry laugh for home.

When we’ve left each friend and brother,

When we’re parted wide and far,

We will think of one another,

As even better than we are.

Every glorious sight above us,

Every pleasant sight beneath,

We’ll connect with those that love us,

Whom we truly love till death!

In the evening, when we’re sitting

By the fire, perchance alone,

Then shall heart with warm heart meeting,

Give responsive tone for tone.

We can burst the bonds which chain us,

Which cold human hands have wrought,

And where none shall dare restrain us

We can meet again, in thought.

So there’s no use in weeping,

Bear a cheerful spirit still;

Never doubt that Fate is keeping

Future good for present ill!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Regret

Long ago I wished to leave

” The house where I was born; ”

Long ago I used to grieve,

My home seemed so forlorn.

In other years, its silent rooms

Were filled with haunting fears;

Now, their very memory comes

O’ercharged with tender tears.

Life and marriage I have known,

Things once deemed so bright;

Now, how utterly is flown

Every ray of light !

‘Mid the unknown sea of life

I no blest isle have found;

At last, through all its wild wave’s strife,

My bark is homeward bound.

Farewell, dark and rolling deep!

Farewell, foreign shore!

Open, in unclouded sweep,

Thou glorious realm before!

Yet, though I had safely pass’d

That weary, vexed main,

One loved voice, through surge and blast,

Could call me back again.

Though the soul’s bright morning rose

O’er Paradise for me,

William ! even from Heaven’s repose

I’d turn, invoked by thee!

Storm nor surge should e’er arrest

My soul, exulting then:

All my heaven was once thy breast,

Would it were mine again!

Stanzas

If thou be in a lonely place,

If one hour’s calm be thine,

As Evening bends her placid face

O’er this sweet day’s decline;

If all the earth and all the heaven

Now look serene to thee,

As o’er them shuts the summer even,

One moment—think of me!

Pause, in the lane, returning home;

‘Tis dusk, it will be still:

Pause near the elm, a sacred gloom

Its breezeless boughs will fill.

Look at that soft and golden light,

High in the unclouded sky;

Watch the last bird’s belated flight,

As it flits silent by.

Hark! for a sound upon the wind,

A step, a voice, a sigh;

If all be still, then yield thy mind,

Unchecked, to memory.

If thy love were like mine, how blest

That twilight hour would seem,

When, back from the regretted Past,

Returned our early dream!

If thy love were like mine, how wild

Thy longings, even to pain,

For sunset soft, and moonlight mild,

To bring that hour again!

But oft, when in thine arms I lay,

I’ve seen thy dark eyes shine,

And deeply felt their changeful ray

Spoke other love than mine.

My love is almost anguish now,

It beats so strong and true;

‘Twere rapture, could I deem that thou

Such anguish ever knew.

I have been but thy transient flower,

Thou wert my god divine;

Till checked by death’s congealing power,

This heart must throb for thine.

And well my dying hour were blest,

If life’s expiring breath

Should pass, as thy lips gently prest

My forehead cold in death;

And sound my sleep would be, and sweet,

Beneath the churchyard tree,

If sometimes in thy heart should beat

One pulse, still true to me.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Winter Stores

We take from life one little share,

And say that this shall be

A space, redeemed from toil and care,

From tears and sadness free.

And, haply, Death unstrings his bow,

And Sorrow stands apart,

And, for a little while, we know

The sunshine of the heart.

Existence seems a summer eve,

Warm, soft, and full of peace,

Our free, unfettered feelings give

The soul its full release.

A moment, then, it takes the power

To call up thoughts that throw

Around that charmed and hallowed hour,

This life’s divinest glow.

But Time, though viewlessly it flies,

And slowly, will not stay;

Alike, through clear and clouded skies,

It cleaves its silent way.

Alike the bitter cup of grief,

Alike the draught of bliss,

Its progress leaves but moment brief

For baffled lips to kiss

The sparkling draught is dried away,

The hour of rest is gone,

And urgent voices, round us, say,

“Ho, lingerer, hasten on!”

And has the soul, then, only gained,

From this brief time of ease,

A moment’s rest, when overstrained,

One hurried glimpse of peace?

No; while the sun shone kindly o’er us,

And flowers bloomed round our feet,—

While many a bud of joy before us

Unclosed its petals sweet,—

An unseen work within was plying;

Like honey-seeking bee,

From flower to flower, unwearied, flying,

Laboured one faculty,—

Thoughtful for Winter’s future sorrow,

Its gloom and scarcity;

Prescient to-day, of want to-morrow,

Toiled quiet Memory.

‘Tis she that from each transient pleasure

Extracts a lasting good;

‘Tis she that finds, in summer, treasure

To serve for winter’s food.

And when Youth’s summer day is vanished,

And Age brings Winter’s stress,

Her stores, with hoarded sweets replenished,

Life’s evening hours will bless.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Speak of the North! A lonely moor

Speak of the North! A lonely moor

Silent and dark and tractless swells,

The waves of some wild streamlet pour

Hurriedly through its ferny dells.

Profoundly still the twilight air,

Lifeless the landscape; so we deem

Till like a phantom gliding near

A stag bends down to drink the stream.

And far away a mountain zone,

A cold, white waste of snow-drifts lies,

And one star, large and soft and lone,

Silently lights the unclouded skies.

. . . . . . . . . .

On the Death of Emily Jane Brontë

My darling thou wilt never know

The grinding agony of woe

That we have bourne for thee,

Thus may we consolation tear

E’en from the depth of our despair

And wasting misery.

The nightly anguish thou art spared

When all the crushing truth is bared

To the awakening mind,

When the galled heart is pierced with grief,

Till wildly it implores relief,

But small relief can find.

Nor know’st thou what it is to lie

Looking forth with streaming eye

On life’s lone wilderness.

“Weary, weary, dark and drear,

How shall I the journey bear,

The burden and distress?”

Then since thou art spared such pain

We will not wish thee here again;

He that lives must mourn.

God help us through our misery

And give us rest and joy with thee

When we reach our bourne!

. . . . . . . . . .

On the Death of Anne Bront

There’s little joy in life for me,

And little terror in the grave;

I ‘ve lived the parting hour to see

Of one I would have died to save.

Calmly to watch the failing breath,

Wishing each sigh might be the last;

Longing to see the shade of death

O’er those belovèd features cast.

The cloud, the stillness that must part

The darling of my life from me;

And then to thank God from my heart,

To thank Him well and fervently;

Although I knew that we had lost

The hope and glory of our life;

And now, benighted, tempest-tossed,

Must bear alone the weary strife.

Analysis of “On the Death of Anne Brontë”

The post A Selection of 10 Poems by Charlotte Brontë appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 24, 2020

10 Modernist Women Writers Who Shouldn’t be Forgotten

Female authors have always been overshadowed by men, but this does not make their writing any weaker or lesser than. Though popular Modernist works in today’s day tend to gravitate toward the male voice, the following Modernist women writers were well known in their day.

Some of their work has fallen into a literary abyss, where little attention has been given to them almost a century later. Their names appeared regularly on bestseller lists in the 20th century, and they were no strangers to readers. At right, May Sinclair.

Most of these women were connected to one another in some way, either through schooling, a crossing of literary paths, or in reviewing another’s work.

What makes these names critical in understanding Modernist literature is that most, if not all, of these women were not confined to writing within the parameters of fiction. Their words wove through and throughout non-fiction, playwriting, criticism, literary magazines, poetry, translating, and more.

This presence of literary versatility flourished during the Modernist period for both women and men. Not only were structural and stylistic constraints in the traditional novel broken, contorted, and subverted, but the same was done to societal conventions.

Artistic movements, like Dadaism and Surrealism, additionally captured the absurdity of tradition. Though some of the following women writers stayed within the confines of traditional literature, their writing converges in the ideal that their work is still deserving of attention and admiration.

. . . . . . . . . .

Dorothy Richardson (1873 – 1957)

Dorothy Richardson was best known for her Pilgrimage novels, which were precursors to and champions of the stream-of-consciousness narrative technique.

Often unmentioned in discussions about Modernism and stylistic conventions for the period, Pilgrimage is Richardson’s magnum opus. It is comprised of thirteen novels that she considered to be chapters. Beginning with Pointed Roofs and ending with March Moonlight, the Pilgrimage novels all follow the life of Miriam Henderson and her quotidian responsibilities. Today, her novels are still in print, but not in all countries.

. . . . . . . . . .

May Sinclair (1863 – 1946)

At the time when May Sinclair’s writing was featured in The Egoist, she was a well-known literary critic and novelist. In The Egoist, she reviewed Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage, coining the now-popular term “stream-of-consciousness,” which Richardson detested.

She was on cordial terms with the three leading Imagist revolutionaries: Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington, and H.D. Her novel, The Three Sisters, parallels the lives of the Brontë sisters in some respects, while Mary Olivier: A Life is mostly known for being featured in The Little Review alongside James Joyce’s Ulysses (rather than for its content).

. . . . . . . . . .

Bryher (Annie Winifred Ellerman; 1894 – 1983)

Known primarily as Bryher, Annie Winifred Ellerman came from an affluent family, as her father was a shipping magnate. With her wealth, Bryher funded the endeavors of her literary friends.

In Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris, Noel Riley Fitch writes that Bryher gave Sylvia Beach, owner of Shakespeare and Company in Paris, “nearly $1,400” (in 1937) just to help keep the bookshop afloat. Bryher married fellow writer Robert McAlmon as a means of convenience, causing her then-husband to be nicknamed “Robert McAlimony,” according to his archives at Yale.

Bryher’s most known-of relationship is with poet H.D. (Hilda Doolittle). A novelist in her own right, Bryher published over a dozen novels, including memoirs and poetry collections.

. . . . . . . . . .

Storm Jameson (1891 – 1986)

Penning nearly fifty novels, Storm Jameson wrote two series — Triumph of Time and Mirror in Darkness — and fifteen non-fiction works. Like many other female writers during the Modernist period, Jameson and her work are overlooked.

In British Fiction After Modernism, Elizabeth Maslin writes a chapter titled, “The Case for Storm Jameson.” There, she argues that because the weight tends to land on high Modernists, like Virginia Woolf, novelists that did not ascribe to the new novelistic conventions during the time are overshadowed.

. . . . . . . . . .

Dorothy Sayers (1893 – 1957)

Dorothy Sayers was known for being, among other things, a translator, detective novelist, Oxford alumna, and literary critic. While a statue of her proudly stands in Essex, she took on the arduous task of translating Dante’ The Divine Comedy. Today, some of her works remain out-of-print, but others can be found in local bookstores today – mostly her detective fiction.

However, you can still find her name inside Penguin editions of The Divine Comedy, where her name is listed as the translator. Her brief biography in the edition lauds her work The Nine Tailors as “fascinating” and notes the breadth of her capabilities, stating that she “also wrote religious plays.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Margaret Kennedy (1896 – 1967)

Margaret Kennedy’s work made it onto the big screen in her day, but before that, she went to school with writers Sylvia Thompson and Winifred Holtby.

In 1925 – the year that marks the publication of The Great Gatsby and Mrs. Dalloway – Kennedy’s novel, The Constant Nymph, reigned as the number two bestselling book. On the charts, it sat five spots above Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith. The Constant Nymph was just one of her works to make it to become a stage production.

. . . . . . . . . .

Winifred Holtby (1898 – 1935)

Besides Winifred Holtby’s schooling with other novelists including her good friend Vera Brittain, she knew Leonard Woolf, Virginia Woolf’s husband. In 1932, she published Virginia Woolf: A Critical Memoir. In its Author’s Note, she references meeting Virginia Woolf only a couple of times, yet she expresses her gratitude to her for aiding the composition of the book.

Holtby not only interviewed Woolf but, Woolf supplied her with “copies of some of her critical articles.” Most known for her posthumously-published book South Riding, Holtby wrote short stories and plays, as well. South Riding made it to the big screen in 1938, three years after her death.

. . . . . . . . . .

Mary Butts (1890 – 1937)

Though her name was no stranger to literary magazines, like The Little Review, during Mary Butts’ lifetime, her paternal great-grandfather was friends with William Blake.

The Modern Novel states that “In Paris [she] came in contact with many of the glitterati of the time – the painter, Nina Hamnett, the writers Ezra Pound, Djuna Barnes, Ford Madox Ford, Bryher, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and many others.” Even though her work has been reprinted in the late 20th century and the 21st century, insight about her life and works remain scant today, though Armed with Madness is considered to be her best and most enduring novel.

. . . . . . . . . .

Mazo de la Roche (1879 – 1961)

Known for her Jalna series, which spans sixteen books, four of Mazo de la Roche’s Jalna novels graced the top ten bestsellers lists in the 1900s: Jalna (1927), Jalna (1928), Finch’s Fortune (1931), and The Master of Jalna (1933).

The Library of Congress holds that the Jalna series contains “the story of the Canadian Whiteoak family from 1854 to 1954, although each of the novels can also be enjoyed as an independent story.” Despite the changes throughout the century, the Whiteoaks maintain a sense of stasis, as “the manor house and its rich surrounding farmland known as ‘Jalna’” never changes in some ways.

. . . . . . . . . .

E.M. Delafield (1890 – 1943)

Born to a count and a novelist, Diary of a Provincial Lady is one of several works that gave E.M. Delafield a name in her own right. As recently as May 2020, The Guardian featured an article by Kathryn Hughes claiming that Delafield should be more prevalent in contemporary literary discussions.

Though Diary of a Provincial Lady has not been out of print, Hughes attributes the “dusty and quaint” title and “the comedy servants” as possible reasons for warding away readers.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francesca Mancino

Francesca Mancino is a Master’s in English student at Case Western Reserve University. After this degree, she hopes to pursue a Ph.D. in English, where she can study Lost Generation literature and culture, along with Modernist female writers that have strayed from the canon. Find more of her writing at Lost Modernists.

MORE MODERNIST AUTHORS ON THIS SITE

Djuna Barnes

H.D. (Hilda Doolittle)

Marianne Moore

The post 10 Modernist Women Writers Who Shouldn’t be Forgotten appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 20, 2020

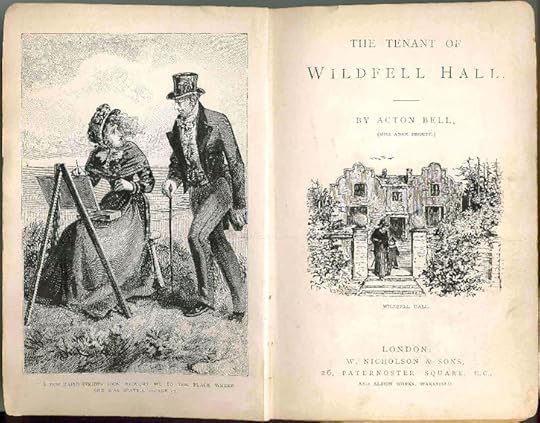

An 1848 Review of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall was published in 1848 under Anne Brontë ’s pseudonym, Acton Bell. It’s now considered one of the earliest feminist novels. Following you’ll find an original review of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, first published under Anne’s pseudonym, Acton Bell.

More so than Anne’s quieter first novel, Agnes Grey (1847), The Tenant of Wildfell Hall was an immediate success. That was despite its being considered shocking by some readers and critics for its unflinching look at the harms of alcoholism and abuse that arose from it.

The novel tells the story of the mysterious Helen Graham, and her arrival at Wildfell Hall with her young son and a servant. Through a series of letters from another character, we learn of Helen’s troubled past.

If you’re interested in the history of this novel, be sure to read this 19th-century introduction by Mary Ward, which discusses the effect that the troubled Brontë brother, Branwell, might have had on the sisters’ work, particularly on The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

When the novel was first published, reviews on both sides of the Atlantic identified it as the work of Currer Bell (Charlotte Brontë‘s pseudonym), author of Jane Eyre, or Ellis Bell (Emily Brontë), author of Wuthering Heights, or both. The three sisters were often assumed to be one writer. And most of the public and critics believed at first that the writer — or writers — of these books was a man. It was the intention of the sisters to conceal their identities.

Anne only lived to the year following the publication of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. She died of tuberculosis at the age of twenty-nine in 1849.

It’s always exciting to find an original review of a classic novel, especially one published so long ago. Following is one from 1848, the year in which the novel was published, in a British newspaper.

. . . . . . . . . . .

See also: Quotes from Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

. . . . . . . . . . .

An 1848 review of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

From the original review of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Acton Bell in The Manchester Weekly Times and Examiner, July 8, 1848: Our readers remember our introduction of Jane Eyre, a novel singularly impressive, and yet, in style and incident, singularly simple.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is from the pen of a brother* of the author of Jane Eyre, to which it bears a strong family likeness.

[*note from Literary Ladies Guide: this review was published at a time when the Brontë sisters were publishing under pseudonyms and it was still generally believed that they were men. Anne wrote under the name of Acton Bell.]

Here we have the same rigid, direct, compressed tone of narrating which, with its undercurrents of humour and wayward pathos, was so striking in Jane Eyre.

Here, too, the effect produced arises out of combinations of the most unpretending and familiar kind — the daily, real-life police reports furnish of “savage ill-treatment by a husband of his wife,” raised a step or two in the social scale, and told with a hard, faithful minuteness that moves the stoutest reader.

A few other figures there are, all drawn from the most unexciting sphere of English country life; the parson and the old lady, the blackguard English country gentleman, the meddling squire, and the village flirt of everyday existence.

Yet, out of these unpromising elements, and with little of anything like reflection, philosophy, or beautiful delineation, Bell has managed to frame a tale which we defy the most blasé novel reader to yawn over.

A strange, mysterious, gloomy fascination, the wild, bleak scenery we are carried through, does exert. It is a book which should be read on a comfortless day, with a scowling sky and fitful gusts of sulky wind sighing and groaning without; with such accompaniments, and alone in some isolated, deserted country mansion, the reader will be made as painfully happy as the novel reader can desire.

Helen Lawrence, the heroine, who, in a diary stretching through some half of the novel, tells us her own story. She is a young English lady of the best kind, full of quiet ardour and quiet wit, accomplished, resolute, and beautiful.

Motherless, the daughter of a country squire, she is brought up at a distance from her father’s estate, unknown, therefore, to the people of the district in which that lies, and where the hero of the novel will be afterwards found residing.

Out of the many suitors for her hand, she selects a Mr. Huntington, a bold, dissipated country gentleman, whose character is drawn with uncommon skill and truth to nature, a riotous enjoyer of life, and with the dashing forwardness which such habits give; yet, he is capable of assuming a respectful tenderness, which, in combination with his beauty of person and manly courage, quite captivate poor Helen’s heart.

Hoping to convert him from his dissipated ways, she becomes his wife and they settle down at Glassdale Manor, Mr. Huntington’s county seat. It is now that the author’s knowledge, seemingly very exact, comes into play.

With the lapse of the honeymoon, all that is bad in the unregulated, uncultivated country gentleman makes its appearance. Abandonment of home for orgies in London with his old club-friends is succeeded by a series of orgies at home. The endeavors and remonstrances by Helen to reform her husband, change his penitent tenderness into indifference and disgust. The radiant, fascinating gentleman sinks into an infuriated and savage sot.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

The stern accuracy of this part of the book has something wonderfully engrossing, in spite of all the repulsiveness of the details. A domestic tragedy of the deepest kind is brought before us — a company of blackguard gentlemen at their disgusting revels, alone with a modest and gentle lady, in the solitude of a squirearchical estate.

Helen lingers on in the hope of yet weaning her husband from his evil ways’ but when, at last, she finds him seeking to inoculate their little son with all the wickedness of grown-up vice, she resolves on flight to a ruined old house. Wildfell Hall, in the neighbourhood of her brother’s estate, is where she can live in secrecy, beyond the reach of her brutal husband, and support herself on the fruits of her skillful pencil.

It is at this point of the heroine’s history that the novel opens, introducing us to Gilbert Markham, by whom, with the introduction of Helen’s diary, the whole story is told in the form of an autobiography.

Gilbert is a gentleman farmer, and hastens to make us acquainted with the people of his own household and neighbourhood. Among them are a certain Frederick Lawrence, a quiet, reserved young gentleman, who has a sister of whom we know something — though not so Gilbert and his friends.

The neighbourhood is agog with the news that a widow-looking lady and a little boy have come to inhabit some rooms in the ruined Wildfell Hall, and Gilbert’s worthy old mother and pretty sister are soon off to visit Mrs. Graham (how Helen identifies herself), the beautiful and sad newcomer.

She returns the call, and a kind of acquaintance, through intimacy she repels, springs up between Gilbert and herself, chiefly through the little boy’s fondness of Gilbert’s dog; the acquaintance proceeds, and is very charmingly painted as on its way to deeper feeling.

Meanwhile, the village gossips are busy speculating on who Mrs. Graham is, and eagerly spy on her to find more about her ways. Frederick Lawrence is discovered to be in the habit of paying her visits, innocent enough ones, as we know, but which lead Gilbert to look upon his friend as a rival, the more so that he warns him against his passion for Helen.

Finally, the brother is horsewhipped by the lover. Things come to a crisis; Gilbert declares himself. And to excuse her rejection, Helen gives him to read the diary of her married life, which clears up the whole mystery for him.

Just at this juncture, she hears that her husband, Mr. Huntington, is dying — neglected and untended — and goes off to nurse him. He dies, and after due delays and misunderstandings, she gives her hand to Gilbert.

On reflection, it seems, this review gives rather too gloomy a portrait of this very clever and powerful book.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (mini-series) on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

An Entire Mistake: The Suppression of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

Review on Smart Bitches Trashy Books

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post An 1848 Review of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 15, 2020

10 Fascinating Facts about Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe (1819 – 1910) was an American poet, essayist, editor, speaker, and activist extraordinaire, especially in the causes of abolition, suffrage, and the advancement of women everywhere.

Although her iconic “Battle Hymn of the Republic” is ubiquitous in patriotic, inspirational, and popular settings, its author is far less known. Let’s look at 10 fascinating facts about the woman behind the verses.

Howe was born on Bond Street and Broadway in New York City to an affluent, Calvinist family; when she was five, her mother died in childbirth. She was educated in a home with its own library and art gallery and well-propertied for a secure future. Her heroic but controlling husband stymied her spirit and mishandled her land holdings.

Once Howe recovered her voice in the company of the New England Woman’s Club and Unitarianism, her mission became to free other women and gain the vote.

. . . . . . . . .

Portrait of Julia Ward Howe by John Elliot

. . . . . . . . .

Howe earned five dollars for the publication of “Battle Hymn”

“Battle of Hymn of the Republic” was first published in The Atlantic Monthly in February 1862.

Howe claimed that a minister friend goaded her to write new verses to the marching song “John Brown’s Body” as the two watched Union soldiers go by in Washington, D. C. Once her hymn became popular and was performed almost everywhere in the North, it provided celebrity and a platform for her causes.

She repeatedly told of how the verses came to her fully formed and that she had risen to write them in semi-darkness. She answered the many requests over her lifetime for handwritten verses to be used as fundraisers.

An early nickname tells her style

Suitors called her “Diva.” She expected esteem. She was undeterred once her mind was set.

Once, she charmed herself onto the caboose of a freight train when she missed the passenger one and needed to keep an engagement; she once hugged a post on a pitching ship to deliver an address she had promised. She could act the “belle” well into her sixties and was indefatigable into her ninety-first year. When she gave her support, she overcame obstacles with courage, wit, and benignity.

. . . . . . . . .

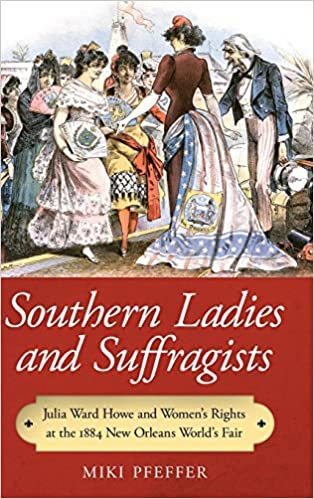

Southern Ladies and Suffragists by Miki Pfeffer on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Her first volume of poetry was provocative for its time

Passion-Flowers (1853) was expressive in ways that seemed inappropriate during True Womanhood when piety, purity, and domesticity were expected, especially of married women.

The collection was published anonymously, but her husband, Samuel Gridley Howe, was blindsided by it and appalled by its intimacies. Longfellow and Margaret Fuller encouraged her poetry.

Housekeeping and motherhood were not her strong suits

She raised five children to adulthood (she lost one son at four) but always demanded “precious time” for study (“PT” to her children). Each pregnancy depressed her, and marriage and motherhood did not fulfill her.

Her husband judged her inept and hired consecutive housekeepers, some of whom were patients from the Perkins School for the Blind, which he founded.

When Samuel Gridley Howe died in 1876, his estate went to their offspring, not to Julia. Her eldest brother, Sam Ward, bought her the house on Beacon St. in Boston. In widowhood, she was most free to pursue her causes, but she worried she might leave debts for her children.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Leadership was her true calling

She was the perpetual president of the Association for the Advancement of Women and the New England Woman’s Club and an editor of its Woman’s Journal. She also helped edit her husband’s abolitionist paper, The Commonwealth.

She was a leader in the American Woman Suffrage Association, the state-centered movement for suffrage, and was active when that group merged with the federal push for a Constitutional amendment and became the NAWSA. The Nineteenth passed too late for Howe to vote.

She also called on mothers to demand world peace and envisioned a Mother’s Day for that purpose.

She promoted suffrage, equality, and “women’s work” when she went to the South

As president of the first Woman’s Department (white) at a World’s Fair in the South, Howe helped open minds to suffrage, as did visiting activists like Susan B. Anthony.

At the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans in 1884-85, she led women to consider higher education, new jobs, suffrage, and transitions in “women’s work.”

She met with representatives of the Colored Ladies Exposition Committee and spoke to audiences in the Colored Department and at two Black universities in New Orleans during her six-month stay. She heard her “Battle Hymn” played and sung at those events.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

She brought literature and journalism to the Cotton Centennial Exposition

Howe tasked her youngest daughter to create a library in the Woman’s Department. Maud Howe amassed over a thousand books, magazines, and newspapers written or edited by women, and she donated 800 books to a circulating library in New Orleans at the end of the fair.

Howe invited a hundred women of the press to cover the fair and the Woman’s Department.

While in the city, she revived a lagging literary club (the Pan Gnostics) and helped members to research, write, present, edit, and publish their works. At least one woman’s career began in that club — Grace King— and other careers were advanced under her leadership.

. . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: A New Orleans Author in Mark Twain’s Court

Letters from Grace King’s New England Sojourns by Miki Pfeffer

. . . . . . . . . .

There was nothing small about her but her size

The redhead was less than five feet tall, but her ambition, determination, wit, and accomplishments were outsized. She arranged her own engagements all over the country and was still trying to do so into her ninety-first year. In forty-four years of journals (lodged in Houghton at Harvard), she logged worries, triumphs, and whereabouts and with-whom.

She could draw a crowd as large as Emerson’s when she lectured

Like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Howe spoke at Bronson Alcott’s School of Philosophy in Concord, Mass. The building is behind Orchard House, where Louisa May Alcott wrote Little Women and other popular books.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The life story of Julia Ward Howe won the first Pulitzer award for biography in 1917

Julia Ward Howe, 1819-1910 by daughters Laura E. Richards and Maud Howe Elliott, assisted by Florence Howe Hall, won that first prize for biography, autobiography, or memoir. In 1899, Howe had published her Reminiscences 1819–1899 and also wrote the biography, Margaret Fuller (Marchesa Ossoli) in 1883.

Contributed by Miki Pfeffer

Miki Pfeffer received the 2015 Eudora Welty Prize for Southern Ladies and Suffragists: Julia Ward Howe and Women’s Rights in the 1884 New Orleans World Fair. Miki is a visiting scholar at Nicholls State University and also the author of A New Orleans Author in Mark Twain’s Court: Letters from Grace King’s New England Sojourns.

Sources

Howe, Julia Ward. Reminiscences 1819-1899. Reprinted New York: Negro Universities Press, 1969.

Pfeffer, Miki. Southern Ladies and Suffragists: Julia Ward Howe and Women’s Rights in the 1884 New Orleans World Fair. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2015

Richards, Laura E. and Maud Howe Elliott. Julia Ward Howe 1819-1910. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1915.

Showalter, Elaine. The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

Williams, Gary. Hungry Heart: The Literary Emergence of Julia Ward Howe. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999.

Ziegler, Valerie. Diva Julia: The Public Romance and Private Agony of Julia Ward Howe. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press, 2003.

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 10 Fascinating Facts about Julia Ward Howe appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 13, 2020

All Passion Spent by Vita Sackville-West (1931)

All Passion Spent by Vita Sackville-West, a 1931 novel, was one of this British author’s most popular works. Its major theme is that of gaining control over one’s own life, and it also addresses the constrictions of class and gender.

We meet Lady Slane, who has lived her adult life as the dutiful wife of a powerful politician and a respectable mother. Her husband having just passed away, she’s already well into in her eighties but determined to live out her remaining days to their fullest.

From the publisher of the 2017 Vintage Classics edition:

“Irreverently funny and surprisingly moving, All Passion Spent is the story of a woman who discovers who she is just before it is too late.

After the death of elder statesman Lord Slane—a former prime minister of Great Britain and viceroy of India—everyone assumes that his eighty-eight-year-old widow will slowly fade away in her grief, remaining as proper, decorative, and dutiful as she has been her entire married life.

But the deceptively gentle Lady Slane has other ideas. First she defies the patronizing meddling of her children and escapes to a rented house in Hampstead. There, to her offspring’s utter amazement, she revels in her new freedom, recalls her youthful ambitions, and gathers some very unsuitable companions—who reveal to her just how much she had sacrificed under the pressure of others’ expectations.”

Vita Sackville-West (1892 – 1962 ) lived an unconventional life, marching to her own drummer. Born to great wealth, she and her husband, the diplomat Harold Nicolson, were both bisexual and gave one another the freedom to pursue other relationships. Yet they had a happy home and family, raising two sons. Vita was part of the storied Bloomsbury circle, which included her great friend Virginia Woolf.

Her work is no longer read as avidly as it was during her lifetime, yet it remains well respected. Here is an American review of All Passion Spent, typical of its positive reception both in her home country and abroad.

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy: The Edwardians by Vita Sackville-West

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1931 review of All Passion Spent

From the original review of All Passion Spent in the Indianapolis Star-Sun, November, 1931: Here is a winter’s tale that must not be spoiled for the reader by too much criticism or fanfare, both of which often prejudice a prospective reader before the book is opened.

But chances are, before you’ve read many pages, you’ll find yourself in sympathy with the elderly Lady Slane. After almost seventy years of conforming to every wish of her just-deceased husband, she decides to live her remaining years to her own liking, “calm of mind, all passion spent.”

Immediately, the author also enlists you agains all the conspiring children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren who had planned Lady Slane’s life after the manner of the offspring. They keep her among them, an unwilling and somewhat unwelcome guest.

But Lady Slane, for the first time in her eighty-eight years, made up her own mind. With her French maid, only a few years younger than herself, she betakes them to a house in Hampstead, kept in remembrance by her for thirty years. There it was, waiting, idle, as if it had some secret understanding with her.

Heart craved quiet, privacy

To this place of retirement her own children might come occasionally, but no grandchildren, and certainly not the great-grandchildren. Her life constantly in the public eye, as wife of a Viceroy to India and later prime minister, had been a strenuous one.

Now all she asked of life was that it pass her by. It pleased her to steep herself in old age. It was to be her one holiday from social publicity. Her heart craved only a small taste of quiet and privacy.

Much of the story concerns itself in establishing Lady Slane in her home, peculiarly fitted for the retirement she so desired. The great peace that came to her, “sitting there in the sun at Hamstead, in the late summer, under the south wall and the ripened peaches” steals into the heart of the reader.

It makes this reader, at least, almost eager to be eighty-eight, when one can at last step aside and meditate on the life that has been lived.

Lady Slane’s life was particularly rich in memories. This reader is delighted to go back with her over her years — what was and what might have been. As with all of us, life had played strange pranks with her, but romance was always kept in sight.

Three institutions

But life even in its twilight could not pass her by. It’s true that as the story is being told, Lady Slane enjoys a brief interlude of contentment, free from intruders and family disturbance. But three old gentlemen gain entry into her home, each for his own particular reason.

There was Mr. Bucktrout, the agent for the house, who felt privileged to come to tea every Tuesday afternoon, and as many times in between as the occasion permitted. Then there was Mr. Gosheron, the contractor, who looked after the repairs and was highly respected, in spite of his always wearing his hat in the house. The third was Mr. Fitzgeorge, who had known Lady Slane in India more than fifty years before.

How these three, all old, eccentric, and unworldly had populated her remote life now at its close, was a bit fantastic to Lady Slane, and in spite of her years, she thoroughly enjoyed the intrusion. For the first time in her life she was freed from pretense.

The strife and pride and living were stripped away and she was able to look at her own desires squarely in the face. She said exactly what she was thinking to the three gentlemen.

Just so, she began to belatedly discover her true self — from whom she was abruptly swept away when her marriage was arranged, and she abandoned her fond ambitions to be an artist and carve out a career for herself.

The understanding and sympathy Lady Slane is suddenly about to show her great-granddaughter Deborah, who is confronted with the same problem she faced in her own girlhood. The comfort that the two of them experience in their talk at the end of the book is Lady Slane’s last bit of happiness on the earthly plane, and would seem a fitting close to a remarkable life — frustrated and then reclaimed after hearts less stout would have proclaimed it too late.

Delicate situation well handled

It is, then, not the story of a tedious old lady, but of an ageless woman. No note of resignation enters into the narrative. All is quiet, even tinged with a little glamour, freedom, independence, romance, and the putting away of trivialities.

The nature of the story is such that it requires a deft touch to handle delicate situations, and Miss Sackville-West has proven herself equal to the task.

Surely the reader will derive a vicarious joy in Lady Slane’s retreat from life. This is the book’s chief hold upon us. We’re all running away at times, a bit weary of this great world. There’s rest in this story for the earth-bound. There’s also a quiet beauty and the subtlest of charm.

And there is an infinite deal of writing between the lines. Could each of us have as peaceful and colorful a journey’s end, and go as gracefully as did Lady Slane! No doubt it takes a rich life to add so much of grace and beauty to death.

. . . . . . . . . .

All Passion Spent by Vita Sackville-West on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

More about All Passion Spent

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Wikipedia

A review on The Australian Legend

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post All Passion Spent by Vita Sackville-West (1931) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 6, 2020

The Loving Spirit by Daphne du Maurier (1931)

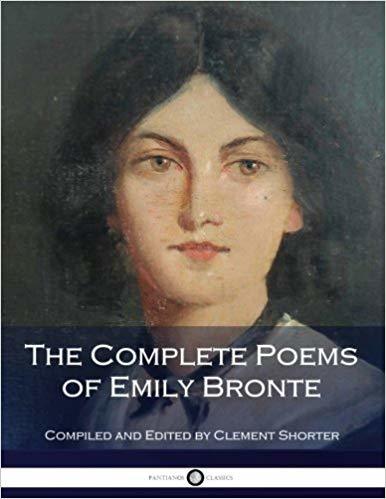

Daphne du Maurier (1907 – 1989), the prolific British novelist, playwright, and short story writer started her publishing career at age twenty two with her first novel, The Loving Spirit (1931).

The title was inspired by the name of a poem by Emily Brontë. It’s well known that du Maurier was greatly inspired by the Brontë sisters; her masterwork, Rebecca (1938), has echoes of Jane Eyre.

Beginning in the early 1800s, The Loving Spirit tells the story of the Coombes family, and is mainly set in Cornwall, a part of England in which the author spent much of her life. Janet Coombes marries her cousin, Thomas Coombes, who is a shipbuilder. The novel follows the adventures and trials of this family for four generations.

A fascinating fact: The Loving Spirit captured the attention of a young British army major, Frederick A.M. “Boy” Browning. Resolving to meet the author, and traveled to Paris to find her. They met the following year, and married a few months later in 1932.

The Loving Spirit was well received and launched what would be a stellar career. This and Daphne du Maurier’s subsequent novels and stories have all offered the reader rich detail, with elements of romance and intrigue. Since her work shaded into the realm of popular fiction in their time, they were sometimes criticized as lacking in depth or intellect, a view that has since been revised.

From the 2003 Time-Warner Books UK edition:

“Cornwall, 1900s. Plyn Boat Yard is a hive of activity, and Janet Coombe longs to share in the excitement of seafaring: to travel, to have adventures, to know freedom. But constrained by the times, instead she marries her cousin Thomas, a boat builder, and settles down to raise a family.

Janet’s loving spirit — the passionate yearning for adventure and for love — is passed down to her son, and through him to his children’s children. As generations of the family struggle against hardship and loss, their intricately plotted history is set against the greater backdrop of war and social change in Britain.

Her debut novel established du Maurier’s reputation and style with an inimitable blend of romance, history and adventure.”

. . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: Jamaica Inn (1936) by Daphne du Maurier

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1931 review of The Loving Spirit by Daphne du Maurier

From the original review in the Province Sun, November 1, 1931: Rebecca West, in her criticism of this book, describes it as “a whopper of a romantic novel in the vein of Emily Brontë.” That it is. It is also in the vein of George du Maurier, grandfather of the authoress; it’s also a legitimate descendant of Peter Ibbetson.

It will be something of a relief to anyone who is wearied with the intense psychological exactitudes of modern fiction to plunge into a tale so romantic and full of life, because, apart from satisfying the average intelligent person’s instinct —the instinct that announces itself very early in life — romance is kin to poetry, and in poetry can be found here and there a flash of insight that penetrates through and beyond the muddle of everyday life.

This book contains the curious blend of instinct, knowledge, and intuition that marks the genuine teller of tales. As the first novel by a young writer, it foretells a future of pleasurable prospects.

“Please God, make me a lad afore I’m grown,” was Janet Coombe’s early prayer, but no miracle happened. She remained a girl — restless and hoydenish, with a loving, unsatisfied spirit — mad an affectionate and successful marriage with her cousin, Thomas Coombe, and bore him six children. This was in 1830 and subsequent years.

Of these children, Samuel and Mary, the two oldest, and Herbert, the fourth, were hard-working, estimable souls, just like their father. Joseph, the third child, was twin spirit with his mother. Philip, the fifth child, was a stranger in the family. Elizabeth, the sixth, was a happy blend of both parents.

Here Miss du Maurier shows her powers. She recognizes the law of polarity. The violent cleaving of spirit to spirit, the very closeness of the tie between Janet and Joseph sets up a counterbalancing force.

Desiring above all things spiritual union with some one person and finding it only in her second son, Janet herself gives birth to his destroyer. Philip, her fourth son, from his childhood to his old age, when Joseph’s grandchild is all that is left to remind him closely of the past, goes his secret way to smash the loving transmissible spirit from whose warmth he feels himself shut out.

Christopher, Joseph’s son, feels the weight of his Uncle Philip’s hatred. Jennifer, Christopher’s daughter, almost dies of it. The good nonentities of the family are swept aside into bewildered poverty by it. It remains for Elizabeth, her excellent husband and their son and grandson to throw in their weight, and the end of the book finds the loving spirt of the time being at rest from its violent journeying.

There is a great quality of courage here; the tale is cast in a large mold. With a feeling of personal exile, the reader is dragged into London for a time, but the main events happen in Cornwall, on the coast, where the English Channel starts at one end of its stormy passage between the Atlantic and the North Sea. They could not be placed more suitably.

. . . . . . . . .

The Loving Spirit on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Quotes from The Loving Spirit

“She gave to both Thomas and Samuel her natural spontaneity of feeling and a great simplicity of heart; but the spirit of Janet was free and unfettered, waiting to rise from its self-enforced seclusion to mingle with intangible things, like the wind, the sea, and the skies, hand in hand with the one for whom she waited. Then she, too, would become part of these things forever, abstract and immortal.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Dust unto dust. There was no reason then for life—it was only a fraction of a moment between birth and death, a movement upon the surface of water, and then it was still. Janet had loved and suffered, she had known beauty and pain, and now she was finished—blotted by the heedless earth, to be no more than a few dull letters on a stone.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Though Thomas liked to think he had his own way over things, it was generally Janet who had the last say in the matter. She would fling a word at her husband and no more, and he would go off to his work with an uneasy feeling at the back of his mind that she had won. He called it ‘giving in to Janie,’ but it was more than that, it was unconscious subservience to a quieter but stronger personality than his own.”

. . . . . . . . .

“The child destined to be a writer is vulnerable to every wind that blows. Now warm, now chill, next joyous, then despairing, the essence of his nature is to escape the atmosphere about him, no matter how stable, even loving. No ties, no binding chains, save those he forges for himself.

Or so he thinks. But escape can be delusion, and what he is running from is not the enclosing world and its inhabitants, but his own inadequate self that fears to meet the demands which life makes upon it. Therefore create. Act God. Fashion men and women as Prometheus fashioned them from clay, and, by doing this, work out the unconscious strife within and be reconciled.”

. . . . . . . . .

More about The Loving Spirit by Daphne du Maurier

On the Daphne du Maurier official website

Wikipedia

Reader discussion on Goodreads

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Loving Spirit by Daphne du Maurier (1931) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 30, 2020

The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield (1924)

An ahead-of-its-time novel, The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield Fisher (at the time known as Dorothy Canfield), published in 1924 by Harcourt, Brace & Co., imagined a domestic role-reversal.

Quite a rare set of circumstances to consider in its time, the mother and farther of the Knapp family were both going through the motions of their proscribed societal gender roles. An accident forced them to reverse roles out of practicality, and coming out of that adversity, a family found strength and happiness.

Dorothy Canfield Fisher (1879 – 1958) was an American author, educational reformer, and social activist based in New England and identified most closely with Vermont. She earned a Ph.D in 1905, was able to speak five languages, and worked for the cause of refugees in Europe.

Canfield Fisher’s body of work included 22 novels and some 18 works of nonfiction. Some of her best known novels included The Brimming Cup, Rough-Hewn, Raw Material, Her Son’s Wife,The Deepening Stream, and Understood Betsy. She was also a prolific author of nonfiction and essays.

From the publisher of the Audible edition of The Home-Maker

Evangeline Knapp’s neighbors are in awe of her prowess. She re-upholsters furniture and can take scraps of fabric and create a beautiful garment. Her house is always immaculate and her children are beautifully behaved – except for the stubborn youngest, but with Eva’s strength of will, they’re certain she’ll sort him out in time.

The neighbors don’t know that in her frenzied zeal to create the perfect home, her children live in dread of her temper. She loves them, but she can’t stand having to remind them constantly about the same things, simple rules easy enough for anyone to understand. Eva can’t abide childishness.

Her husband Lester is no less miserable in his job as a department store accountant, sacrificing his love of literature and poetry to the daily grind of commerce. Lester can’t seem to get ahead and feels like a failure. Shouldn’t a man be able to provide better for his family? Isn’t that his job? When a near fatal accident forces these two to switch roles, each finds their true calling. Then fate steps in again.

As with her children’s classic Understood Betsy, Dorothy Canfield Fisher brilliantly explores the inner lives not only of the parents but the three Knapp children. An early champion of the Montessori Method, the author stresses that children should learn by doing, should be allowed to fail at tasks so they can experience the triumph of success and discover their strengths. The Home-Maker proves that the same holds true for adults, that biology should not determine destiny.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: Understood Betsy by Dorothy Canfield Fisher

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1924 review of The Home-maker by Dorothy Canfield

From the original review in the Austin-American Statesman, August 24, 1924: It would be unjust to dismiss Dorothy Canfield’s new novel, “The Home-maker,” with the bare statement that it is merely another novel about the dissatisfied modern woman.

Out of a flood of such novels, however, there is some satisfaction in discovering one that delves into the subject from an entirely new angle and brings to light an entirely different opinion. In this case the author has solved her problem, and is probably justified in doing so because the characters themselves justify a solution.

Lester Knapp is an ordinary bookkeeper who hates his work, hates his associates, and hates the very air of commercialism. He is incompetent because he is a dreamer and has no interest whatsoever in his work. There was a time when he wrote poetry, and he still possesses that dreamer’s interest in aesthetic beauty.

He is a misfit. and simply does not possess the prerequisites that might assist him to an adjustment to his environment. Dreaming of the luxury of having nothing to do but sit back and read poetry and be carried away by its beauty. and chafing under the strain of never having an opportunity to indulge this desire.

Lester Knapp, through a change in the management and ownership of the establishment where he is employed, sees the promotion of a man who is a sort of rival. Going home he contemplates ending his life; his predicament is solved tor him when a neighbors’ house catches on fire. During the confusion, Lester falls from the root and is carried home, hurt and helpless.

Eva Knapp, Letser’s wife, is equally dissatisfied with the trials of home life. Her husband’s accident to husband opens the way tor her to seek a means of livelihood in the world of business. She gets a position in the establishment where her husband was formerly employed, and her delight with the work, coupled with her unusual character, brings rapid promotion and satisfaction to her.

Now forced to stay home and confined to a wheelchair, Lester becomes for the first time truly interested in the children. He studies them — their desires, their needs, and their interests. He strives to become a companion to them, and is surprised at the resulting revelations that unfold — not only about his children, but about himself.

He also makes a study of housekeeping. He prefers this new occupation, and for the first time since his college days finds time to enjoy poetry. Where he had made a failure his wife makes a success; and where she had been for the most part a failure, he had made a success.

The climax of these new circumstances comes when the family physican says that he can cure Lester of his malady. But Lester has already discovered that fact for himself and has rebelled at the very thought of being cure because he knows it means he will have to go back to the world of commerce. Conventions, after all, must be satisfied; the man of the family must be the breadwinner.

Eva does not want him to be cured, for she knows that it would mean her return to the drudgery of home life. Even the children, Helen, Henry, and little Stephen, do not want to lose the wonderful companionship of their father, which has come to mean so much to them.

The outcome of this entanglement is admirably and dramatically handled by Dorothy Canfield. The author has an uncanny way of making everything work out. That’s really the only disagreeable feature of the novel. By turning everything precisely around, all the difficulties of the Knapp family are too neatly, and completely, resolved.

For the rest, the novel is truly admirable. The characters are superbly drawn. Eva is, as one female reader remarked, exactly like dozens of women she knows. Anyone who understands the spirit of a poetic nature understands Lester Knapp. And, perhaps best of all. the author knows children and understands them. Her portrait of the Knapp children is admirable and touching.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield (1924) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 28, 2020

The Scapegoat by Daphne Du Maurier (1957)

The Scapegoat by Daphne du Maurier, published in 1957, was one of the British author’s successful mid-career novels, coming after Jamaica Inn, Rebecca, and My Cousin Rachel. and In her skillful hands, this suspense novel makes an ingenious doppelgänger plot work on many levels.

In brief, it’s the story of a disaffected Englishman and an aristocratic Frenchman who meet by an accidental encounter and are at once struck by how much they resemble one another. John, an English academic, is compelled by Count Jean de Gué into switching places with him. What ensues is how he is swept into the count’s complicated intrigues and family life.

From the 1957 Doubleday edition:

Someone jolted my elbow as I drank and said, ‘Je vous demande pardon,’ and as I moved to give him space he turned and stared at me and I at him, and I realized, with a strange sense of shock and fear and nausea all combined, that his face and voice were known to me too well. I was looking at myself.”

The Englishman and the Frenchman continue to inspect each other — astounded that they could look so alike and not have known of each other’s existence before this moment. The problems that each had considered so vital before that instant of uncanny recognition were forgotten as they began to talk …

It was not until the next day when he awoke that John, the Englishman, realized he had talked too much. His French companion was gone; John had been trapped into taking the place of the Comte de Gué, head of a large family — master of a château.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

. . . . . . . . . .

Not since Rebecca has Daphne du Maurier written a novel so full of the sense of mounting excitement, of a “wanting to know what is going to happen.”

Loaded with suspense and crackling wit, The Scapegoat has a double fascination: John’s manipulations to escape detection by the Comte’s large family, his servants, his mistresses; and his constant and frustrating attempts to discover that enigmatic evil that dominates all who live within the Château — without asking the questions that would give him away.

Beneath the surface of this immensely exciting plot, Miss du Maurier has filled her novel with human significance. The Scapegoat is eminently readable and profoundly moving —a reading adventure you will long remember.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Scapegoat by Daphne Du Maurier on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1957 review of The Scapegoat by Daphne Du Maurier

From the original review in the Akron Beacon Journal, February 17, 1957: It couldn’t actually happen in real life (or could it?) but Daphne du Maurier’s skill makes The Scapegoat a plausible perplexity.

The Scapegoat is the tale of one man who was trapped into impersonating another, living as husband of a saddened wife, father of a fanciful child, manager of a glass-making concern, and son of an aging, dope-addled mother.

All of the action takes place within one week, yet so much is learned of the past that the book seems to span a generation.

The tale opens in a French village. An Englishman, John, is slightly jostled, looks up, and finds himself “with a strange sense of shock and fear and nausea all combined … looking at myself.” The two men, equally startled, walk over to look into a mirror together.

“It was no chance resemblance — no superficial likeness — it was as though one man stood there.”

John then was mulling the idea of seeking a brief retreat in a monastery to learn how he should go on living. He was a casual lecturer on the French historic and literary past, without family or ties. He felt himself a failure. This lack of useful affection concerned him.

His alter ego, Jean de Gue, was a count with a castle he didn’t care for, a marriage he called a trap, “too many possessions — human ones.” The ate an drank together, the wily Frenchman feeling out his double.

The next morning, John woke in a hotel room, the valise of Count De Gué nearby, a solicitous chauffeur waiting to take “his master” home despite protestations. Evidently, Jean was unwilling to go home. There was no evidence that John was other than the count. He began to try to live the role.