Nava Atlas's Blog, page 47

January 2, 2021

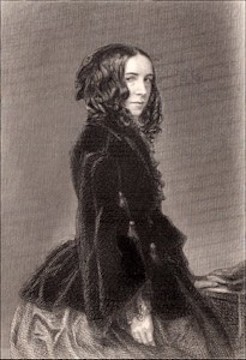

Mother and Poet by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

“Mother and Poet” is a poem by esteemed British poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806 – 1861). Written in a confessional manner, it’s a mother’s lament for having lost two sons serving in war. Though this poem isn’t autobiographical, Elizabeth had endured the sudden death of a beloved brother, and perhaps this allowed her to effectively convey the trauma of losing loved ones.

Suffused with grief and guilt, the mother narrating the poem exalts the bravery of her soldier sons doing battle in Italy. At the same time, it conveys the mother’s pain of the personal loss.

“Mother and Poet” was one of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s later poems, published in Last Poems (1862). If she wasn’t speaking of herself in this poem, to who might it have been referring?

A note in Last Poems explains that it was inspired by the true story of Baroness Olimpia (sometimes referred to as “Laura”) Savio (1815–1889), who was indeed a mother, poet, and writer from Turin, Italy. Both of her sons died in the battle of the Risorgimento, or Italian reunification.

“Mother and Poet” Analysis by Kristyn Baker and Miranda Butler (video) features some in-depth discussion.

More poetry by Elizabeth Barrett Browning on this site:

10 Shorter Poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Sonnets from the Portuguese (full text)

“The Cry of the Children”

To Flush, My Dog

A Dead Rose

To George Sand, a Desire

. . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Barrett Browning and son Robert Wiedemann Barrett Browning, 1860

. . . . . . . . .

Mother and Poet

I.

Dead! One of them shot by the sea in the east,

And one of them shot in the west by the sea.

Dead! both my boys! When you sit at the feast

And are wanting a great song for Italy free,

Let none look at me!

II.

Yet I was a poetess only last year,

And good at my art, for a woman, men said;

But this woman, this, who is agonized here,

— The east sea and west sea rhyme on in her head

For ever instead.

III.

What art can a woman be good at ? Oh, vain!

What art is she good at, but hurting her breast

With the milk-teeth of babes, and a smile at the pain ?

Ah boys, how you hurt! you were strong as you pressed,

And I proud, by that test.

IV.

What art’s for a woman ? To hold on her knees

Both darlings! to feel all their arms round her throat,

Cling, strangle a little! to sew by degrees

And ‘broider the long-clothes and neat little coat;

To dream and to do at.

V.

To teach them … It stings there!I made them indeed

Speak plain the word country. I taught them, no doubt,

That a country’s a thing men should die for at need.

I prated of liberty, rights, and about

The tyrant cast out.

VI.

And when their eyes flashed … O my beautiful eyes! …

I exulted; nay, let them go forth at the wheels

Of the guns, and denied not. But then the surprise

When one sits quite alone! Then one weeps, then one kneels!

God, how the house feels!

VII.

At first, happy news came, in gay letters moiled

With my kisses, — of camp-life and glory, and how

They both loved me; and, soon coming home to be spoiled

In return would fan off every fly from my brow

With their green laurel-bough.

VIII.

Then was triumph at Turin: Ancona was free!’

And some one came out of the cheers in the street,

With a face pale as stone, to say something to me.

My Guido was dead! I fell down at his feet,

While they cheered in the street.

IX.

I bore it; friends soothed me; my grief looked sublime

As the ransom of Italy. One boy remained

To be leant on and walked with, recalling the time

When the first grew immortal, while both of us strained

To the height he had gained.

X.

And letters still came, shorter, sadder, more strong,

Writ now but in one hand, I was not to faint, —

One loved me for two — would be with me ere long :

AndViva l’ Italia! — he died for, our saint,

Who forbids our complaint.”

XI.

My Nanni would add, he was safe, and aware

Of a presence that turned off the balls, — was imprest

It was Guido himself, who knew what I could bear,

And how ’twas impossible, quite dispossessed,

To live on for the rest.”

XII.

On which, without pause, up the telegraph line

Swept smoothly the next news from Gaeta : —Shot.

Tell his mother. Ah, ah, his, ‘ their ‘ mother, — not mine, ‘

No voice says “My mother” again to me. What!

You think Guido forgot ?

XIII.

Are souls straight so happy that, dizzy with Heaven,

They drop earth’s affections, conceive not of woe ?

I think not. Themselves were too lately forgiven

Through THAT Love and Sorrow which reconciled so

The Above and Below.

XIV.

O Christ of the five wounds, who look’dst through the dark

To the face of Thy mother! consider, I pray,

How we common mothers stand desolate, mark,

Whose sons, not being Christs, die with eyes turned away,

And no last word to say!

XV.

Both boys dead ? but that’s out of nature. We all

Have been patriots, yet each house must always keep one.

‘Twere imbecile, hewing out roads to a wall;

And, when Italy ‘s made, for what end is it done

If we have not a son ?

XVI.

Ah, ah, ah! when Gaeta’s taken, what then ?

When the fair wicked queen sits no more at her sport

Of the fire-balls of death crashing souls out of men ?

When the guns of Cavalli with final retort

Have cut the game short ?

XVII.

When Venice and Rome keep their new jubilee,

When your flag takes all heaven for its white, green, and red,

When you have your country from mountain to sea,

When King Victor has Italy’s crown on his head,

(And I have my Dead) —

XVIII.

What then ? Do not mock me. Ah, ring your bells low,

And burn your lights faintly!My country is there,

Above the star pricked by the last peak of snow :

My Italy ‘s THERE, with my brave civic Pair,

To disfranchise despair!

XIX.

Forgive me. Some women bear children in strength,

And bite back the cry of their pain in self-scorn;

But the birth-pangs of nations will wring us at length

Into wail such as this — and we sit on forlorn

When the man-child is born.

XX.

Dead! One of them shot by the sea in the east,

And one of them shot in the west by the sea.

Both! both my boys! If in keeping the feast

You want a great song for your Italy free,

Let none look at me !

The post Mother and Poet by Elizabeth Barrett Browning appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 30, 2020

Marilyn French

Marilyn French (November 21, 1929 – May 2, 2009) was an American author and radical feminist activist best known for her debut novel, The Women’s Room. French wrote many other controversial works, though this novel made her a major literary star in the modern feminist movement.

Born Marilyn Edwards in Brooklyn, New York, she was the daughter of third-generation Polish immigrants. Her father, E. Charles Edwards was an engineer and her mother, Isabel Hazz Edwards, was a department store clerk.

While growing up, French recalled that her mother was the dominant figure in the family’s poor household. This became an early lesson in her life to not succumb to male authority.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Family and Education

As a child, French played the piano and dreamed of one day becoming a composer. That changed once she arrived at Hofstra University, then known as Hofstra College, in 1951. Before attending Hofstra, she married Robert M. French Jr. in 1950.

While working on her education, she endured her husband’s disapproval of her education, all the while supporting him through his law school studies. Her marriage was reportedly unhappy, as she once said “I saw my mother’s life. I tried very hard to escape and I ended up in the same trap.” Despite this, she earned her bachelor’s degree in philosophy and English literature.

After the couple had two children, French returned to Hofstra and in 1964 earned her Master’s degree in English. After graduating, she became an English instructor at Hofstra, a post she held until 1968. In 1967, she divorced Robert French and went back to school yet again, earning a Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1972.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Women’s Room is French’s best-known work

. . . . . . . . .

Early works

After earning her doctorate, French worked as an assistant professor of English at the College of the Holy Cross Worcester, Massachusetts from 1972 to 1976. At the same time, she began creating works that focused on patriarchy and women’s history. In particular, her thesis on James Joyce’s Ulysses gained a substantial amount of praise.

She credited her expanding awareness of feminism to her troubled marriage, the rape of her eighteen-year-old daughter in 1971, and Kate Millet’s Sexual Politics. In addition to working as an assistant professor, she was also a Mellon Fellow in English at Harvard from 1976 to 1977.

In addition to the novels and other works she created, she also contributed articles and essays to journals, such as Soundings and Ohio Review, under the pen name Mara Solwoska.

Controversial works

In 1977, French published her first and best-known novel, The Women’s Room, which reflects on her own life. It follows a group of female friends living in 1960s America with a militant radical feminist named Val. At one point in the novel, Val says, “all men are rapists, and that’s all they are. They rape us with their eyes, their laws, and their codes.”

The controversial novel was translated into twenty languages and sold over twenty million copies. Although The Women’s Room was followed by notable gains in the three decades after its publication, she pointed out that there was still much lingering gender inequality.

Aside from this novel, she created significant work in her later life called From Eve to Dawn: A History of Women. It was first published in Dutch in 1995 and translated to English in 2002. This novel examined how exclusion from intellectual histories has denied women of their past, present, and future.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Themes in French’s work

French primarily focused on the subjugation of women in her works. She often examined the expectations placed on married women after the World War II era. She also became an influential opinion-maker on gender issues she witnessed in the patriarchal society in which she lived.

She once said, “My goal in life is to change the entire social and economic structure of Western civilization, to make it a feminist world.”

She also often declared that the oppression of women was a byproduct of an entrenched male-dominated culture. In her 1992 novel, The War Against Women, she expanded on female oppression, writing: “Men’s need to dominate women may be based in their own sense of marginality or emptiness; we do not know its root, and men are making no effort to discover it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Marilyn French books on Bookshop.org*

Marilyn French page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Awards and honors

Despite negative reviews, The Women’s Room remained a best-seller for two years, was translated into over twenty languages, and was adapted to film. A few years later in 1982, the Berkley Publishing Group commended it as one of its top five paperback sellers of all time.

In 1993, French earned the Harvard Centennial Medal, the highest honor bestowed by the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

After From Eve to Dawn: A History of Women was published in English in 2002, it was published again in four volumes by The Feminist Press and again in three volumes by MacArthur & Company.

Grim diagnosis

In 1992, French was diagnosed with esophageal cancer after being a longtime smoker. Doctors told her she only had a few months to live. In the years following her supposed death sentence, she continued publishing an astonishing amount of works. Her battle with illness became the basis of her book, A Season in Hell: A Memoir, published in 1998.

French won her battle with cancer. “I cannot say I am happy I was sick, but I am happy that sickness, if it had to happen, brought me to where I am now. It is a better place than I have been before.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The legacy of Marilyn French

French died in 2009 of heart failure at age 79, in New York City. “She was in pain for fifteen years but she was extremely brave. She fought through it, she wrote through it and carried on her life. The printed word was a source of life for her,” said Carol Jenkins, a friend of the author, who runs the Women’s Media Center, an advocacy group in New York.

In the years prior to her death, French believed that she had seen a notable change in society’s attitude towards women, though progress was still needed. American author Florence Howe said of French’s work that “For the first time women have history. The world changed and she helped change it.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Marilyn French

Major works

The Book as World: James Joyce’s Ulysses (1976)

The Women’s Room (1977)

The Bleeding Heart (1980)

Shakespeare’s Division of Experience (1981)

Beyond Power: On Women, Men, and Morals (1985)

Her Mother’s Daughter (1987)

The War Against Women (1992)

Our Father (1994)

My Summer with George (1996)

A Season in Hell: A Memoir (1998)

From Eve to Dawn: A History of Women in Three Volumes (2003)

Critical studies

Feminist Criticism and Marilyn French

Marilyn French Critical Essays

More information and sources

Wikipedia

Marilyn French Obituary in the New York Times

Encyclopedia

Reader discussion of French’s books on Goodreads

Marilyn French papers at Columbia University

Skyler Isabella Gomez is a 2019 SUNY New Paltz graduate with a degree in Public Relations and a minor in Black Studies. Her passions include connecting more with her Latin roots by researching and writing about legendary Latina authors.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Marilyn French appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 29, 2020

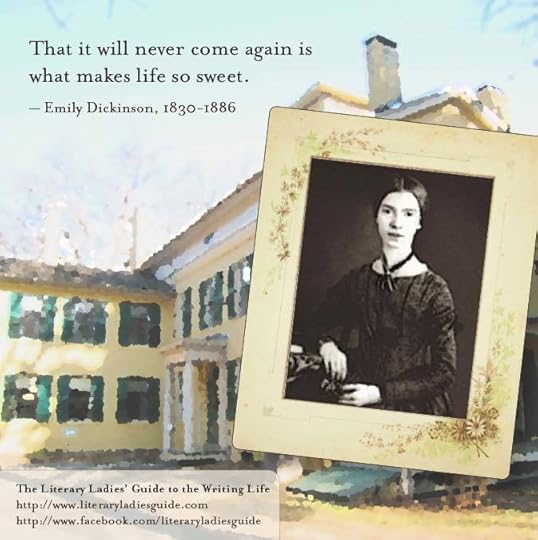

Sic Transit Gloria Mundi — an early poem by Emily Dickinson (1852)

“Sic Transit Gloria Mundi” was the first poem by Emily Dickinson (1830 – 1886) to be published. Without her prior knowledge or consent, it appeared in the February 20, 1852 issue of the Springfield Daily Republican newspaper.

Emily, then age 21, wasn’t pleased. Still a budding poet, she was not at all interested in publication. In her teens and twenties, she may have been reserved and a bit shy, but nothing to hint at how reclusive she would become in her later years. In fact, she and her sister Lavinia (Vinnie) enjoyed quite an active social life in their youth.

One of the highlights of the year was Valentine’s Day, an occasion to brighten the long, cold winters of their home town, Amherst, Massachusetts. Young people enjoyed parties and lavish handmade cards and letters created for a holiday that wasn’t nearly as exclusive to couples as it has since become.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Emily Dickinson

. . . . . . . . .

Emily was inspired to write the long, lively poem, still among her best known, that begins “Sic transit Gloria mundi.” Translated as “This passes the glory of the world,” here’s how it happened to get published, according to Krystyna Poray Goddu, in Becoming Emily: The Life of Emily Dickinson (2019):

“February [1852] also saw the usual flurry of Valentine’s Day notes and poems. To Emily’s surprise, her valentine to young William Howland, who had worked in her father’s law firm, was published, anonymously, in the February 20, 1852 issue of the Springfield Daily Republican newspaper.

The valentine, a poem of 17 quatrains (verses with four lines) with the second and fourth lines of each verse rhyming, holds two mysteries. First, to this day nobody knows who sent it to the newspaper.

Second, Emily never showed any special interest in Howland. Why she chose him as the recipient of this long poem is mystifying. The ambitious poem is noteworthy for being so cleverly written and technically well done.”

Though Howland never owned up to it, as the poem’s recipient, it might be logical to assume that he was the culprit who submitted it to the paper.

All through her life, Emily remained disinterested in having her poems published, though she enjoyed sharing a small number with those she loved or trusted. After her death, over a thousand poems were discovered by her sister Lavinia. By some estimates the number of poems were 1,100; other sources state that it was closer to 1,800.

Analyses of Sic transit gloria mundi

Blogging Dickinson

Emily Dickinson’s Valentines (preview on Jstor)

. . . . . . . . . .

Sic transit gloria mundi

“Sic transit gloria mundi,”

“How doth the busy bee,”

“Dum vivimus vivamus,”

I stay mine enemy!

Oh “veni, vidi, vici!”

Oh caput cap-a-pie!

And oh “memento mori”

When I am far from thee!

Hurrah for Peter Parley!

Hurrah for Daniel Boone!

Three cheers, sir, for the gentleman

Who first observed the moon!

Peter, put up the sunshine;

Patti, arrange the stars;

Tell Luna, tea is waiting,

And call your brother Mars!

Put down the apple, Adam,

And come away with me,

So shalt thou have a pippin

From off my father’s tree!

I climb the “Hill of Science,”

I “view the landscape o’er;”

Such transcendental prospect,

I ne’er beheld before!

Unto the Legislature

My country bids me go;

I’ll take my india rubbers,

In case the wind should blow!

During my education,

It was announced to me

That gravitation, stumbling,

Fell from an apple tree!

The earth upon an axis

Was once supposed to turn,

By way of a gymnastic

In honor of the sun!

It was the brave Columbus,

A sailing o’er the tide,

Who notified the nations

Of where I would reside!

Mortality is fatal—

Gentility is fine,

Rascality, heroic,

Insolvency, sublime!

Our Fathers being weary,

Laid down on Bunker Hill;

And tho’ full many a morning,

Yet they are sleeping still,—

The trumpet, sir, shall wake them,

In dreams I see them rise,

Each with a solemn musket

A marching to the skies!

A coward will remain, Sir,

Until the fight is done;

But an immortal hero

Will take his hat, and run!

Good bye, Sir, I am going;

My country calleth me;

Allow me, Sir, at parting,

To wipe my weeping e’e.

In token of our friendship

Accept this “Bonnie Doon,”

And when the hand that plucked it

Hath passed beyond the moon,

The memory of my ashes

Will consolation be;

Then, farewell, Tuscarora,

And farewell, Sir, to thee!

. . . . . . . . . .

Emily Dickinson on Bookshop.org*

Emily Dickinson page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: 10 Well-Loved Poems by Emily Dickinson

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Sic Transit Gloria Mundi — an early poem by Emily Dickinson (1852) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 26, 2020

Bringing Daphne du Maurier’s Jamaica Inn to the Big Screen

The following is excerpted from Phantom Lady: Hollywood Producer Joan Harrison, the Forgotten Woman Behind Hitchcock, published by Chicago Review Press. © 2020 by Christina Lane.

In the summer of 1938, signed on to direct an adaptation of Daphne du Maurier‘s novel Jamaica Inn, which was to be his last British film before venturing to Hollywood. The preeminent producer Erich Pommer and lead actor Charles Laughton were already lined up to produce the movie through their jointly owned company Mayflower Pictures.

Jamaica Inn was to be the first screenwriting turn for Hitchcock’s assistant , who was effectively already a creative producer in his unit (though without the official credit). Harrison entertained affection for du Maurier’s material, but more than this, she and the writer were friends — traveling in the same social circles. Harrison resolved not to let her down.

The wild, beguiling Cornwall coast

Born to the popular actor Gerald du Maurier and Muriel Beaumont in London in 1907, Daphne du Maurier was one of the best-known English writers of her time (going on to become one of the most celebrated authors of the twentieth century). She thrived in gothic romance and psychological thrillers like the novel Rebecca and the short story “The Birds” (both equally well known to readers and cinephiles).

The wild, beguiling coastal region of Cornwall — with its spectacular harbor views, hidden coves, and dense, tangled woods — in particular obsessed her. When, on a trip with her mother and sisters at the age of nineteen, she first encountered Cornwall’s village of Fowey, she convinced her parents to purchase a cliffside house, which they did, and christened Ferryside.

Du Maurier found the setting gave her a space, both literally and figuratively, to create. “Here was the freedom I desired,” she later reflected. “Freedom to write, to walk, to wander.” The area would become the setting of most of her works. Inspired by Fowey, by the age of twenty-seven, du Maurier penned three novels and a biography of her father.

. . . . . . . . .

Jamaica Inn by Daphne du Maurier

. . . . . . . . .

Jamaica Inn — the 1936 novel

But it was the breakout success of Jamaica Inn in 1936 that guaranteed du Maurier’s place in literary circles. The historical novel follows twenty-three year-old Mary Yellen across the Cornish Moors to live with her Uncle Joss and Aunt Patience following the death of her mother. Helping them run the eponymous inn, she begins to suspect that her uncle is part of a band of murderous shipwreckers.

Du Maurier had stumbled upon the actual Jamaica Inn several years prior, while riding on Bodmin Moor to the north of Fowey and losing her bearings in sudden, thick fog. Rising before her unexpectedly, the inn (which indeed had been a smugglers’ haven) provided afternoon refuge — and eventually fodder for Mary’s story.

Little surprise that Fowey has since been dubbed “du Maurier country,” a description befitting not just her connection to the place, but the landscape of her imagination.

. . . . . . . . .

Joan Harrison in 1943

. . . . . . . ..

Casting and film production commences

Jamaica Inn was slated to begin production in September and end in October 1938, under the assumption that the Hollywood move might occur as early as January. In fact, Jamaica Inn’s production ended up running through January; nothing about the production process came easy. Producer and lead actor Charles Laughton had an enormous ego, and his producing partner Erich Pommer, the former head of Germany’s UFA, was overly hands-on.

For Joan Harrison, the script development process had been difficult. Clemence Dane (a pseudonym for Winifred Ashton) had written a screenplay in 1937 when the project had a false start. Now that Hitchcock was commissioned, Dane’s script went by the wayside and Sidney Gilliat came on board, along with novelist and playwright J. B. Priestley (brought in by Laughton to pen additional dialogue for his character).

Before Harrison and Gilliat’s involvement, Laughton had sent Dane’s draft to the Production Code Administration in anticipation of a successful American release. He heard back that there was an essential problem; they needed to alter the fact that the villain was a man of the cloth so as not to offend religious groups. After hearing this, Laughton nearly wanted off the picture.

Upon deciding to change the vicar into the town squire, Gilliat recalled, “We evolved (Hitch and Joan and I) a fairly satisfactory Jekyll-and-Hyde-character.” Then there was the challenge of how to handle the big reveal.

In the book, the reader doesn’t arrive at the mastermind’s identity until nearly the end. In the film, the aha moment occurs early on, partly because of narrative necessity — the villain is now a legal authority and an integral part of the community—and partly because Laughton wasn’t about to be confined to the finale.

. . . . . . . . . .

A scene from Jamaica Inn, 1939

. . . . . . . . . . .

Trouble on the set

Hitchcock found it troubling that the “surprise story” now became “a suspense story” (structured around the question of When will Mary and the others discover that which the spectators already know?). Hitchcock once said, “It’s very difficult to make a who-done-it. You see, this was like making a who-done-it, and making Charles Laughton the butler.”

With the director “truly discouraged,” each script meeting was filled with stress. To him, “it was completely absurd, because logically the judge should have entered the scene only at the end of the adventure.”

During the shooting of Jamaica Inn, there was also Laughton’s histrionic personality to contend with. As he struggled to find his character, he demanded numerous takes and more than a little hand-holding.

According to Hitchcock, the actor’s “mercurial” personality was so confounding that the director “tried to duck out of the picture two weeks before we started shooting,” but little could be done once the contract was signed. Joan’s role throughout it all was to serve as the buffer, doing the best she could to smooth out the tense back-and-forth among Hitchcock, Laughton, Pommer, the writers, and the actors.

Eighteen-year-old Maureen O’Hara, a relative newcomer from Ireland, played the female lead. Luckily, O’Hara enjoyed Laughton. She was riding high as a recent Mayflower Pictures discovery and had just signed a seven-picture deal.

What she may not have realized was that if the adaptation had remained more faithful to the novel, she would have enjoyed more screen time. As difficult as it was to compete with Laughton’s on-screen mugging, she turned in a respectable performance as a courageous, precocious, and self-possessed heroine.

. . . . . . . . . .

Phantom Lady on Bookshop.org*

Phantom Lady on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Du Maurier’s disappointment, a film flop

Upon Jamaica Inn’s release in 1939, du Maurier was so disappointed that she demanded her name be removed from the opening titles. The film’s reputation has not improved much with age, and the struggles that Laughton, Pommer, and Hitchcock’s team had over creative control are evident on the screen.

The movie suffers from Laughton’s overblown performance and a decided lack of suspense, based on the fact that his character is revealed to be the villain so early on. Several decades later, it was named one of the “fifty worst films of all time” in Harry Medved and Randy Dreyfuss’s book of the same title.

There have, however, been efforts to rehabilitate the film’s reputation and reclaim it for Hitchcock’s canon. Maurice Yacowar, author of Hitchcock’s British Films, concludes, “[Laughton’s] dominance over the director hurts the film. But the film remains a Hitchcock.”

. . . . . . . . .

One of Joan Harrison’s other notable achievements was co-writing the screenplay for the brilliant 1940 film adaptation of Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, which enjoyed far greater success.

. . . . . . . . . .

Anticipation of Joan Harrison’s later work

The case can be made that the film is also thoroughly “a Harrison,” given the ways it anticipates her later work. Jamaica Inn’s domestic gothic themes and disturbing psychology are reminiscent of those found in Phantom Lady (1944), The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945), Nocturne (1946), and They Won’t Believe Me (1947).

Its perverse textures and pathological violence speak directly to Joan Harrison’s preoccupation with what lies hidden beneath romantic, marital, and familial relations. Moreover, the scene in which Mary is trapped in her bedroom with her uncle may be viewed as a predecessor to Phantom Lady’s finale, in which Carol Richman is cornered by the murderous Marlow. (Women’s fearlessness in the face of jeopardy would become a recurring theme.)

There are additional distinguishing marks of Harrison’s signature: Mary’s investigative gaze, her rescue of the hero, and the idea of women saving women. Jamaica Inn sits neatly beside The Lady Vanishes, as these signature marks come into focus and a shift away from light seriocomic thrillers becomes more obvious.

Joan Harrison scored her first official screen credit on Jamaica Inn—as one of the writers. Some, even Hitchcock in one instance, have suggested this was chiefly a tactical maneuver, his way of ensuring her entree into Hollywood.

However, there is a good deal to indicate that she bore a significant influence on the film. Her day-to-day involvement in the writing sessions, her presence on the set, and Jamaica Inn’s close affinities with her other films authenticate this. Hitchcock’s passing pronouncement notwithstanding, Joan earned her Jamaica Inn writing credit.

Contributed by Christina Lane: Christina Lane is the author of Phantom Lady: Hollywood Producer Joan Harrison, the Forgotten Woman Behind Hitchcock (Chicago Review Press, 2020). She has written extensively on film history, aesthetics, and women’s media production, including Feminist Hollywood: From Born in Flames to Point Break (2000) and Magnolia (2011), the first book-length treatment of the Paul Thomas Anderson film.

She is associate professor of film studies and chair of the Cinematic Arts department at the University of Miami. She is a member of the Women Film Critics Circle and has provided commentary to such outlets as Air Mail, NPR, Turner Classic Movies, and the Daily Mail.

. . . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Bringing Daphne du Maurier’s Jamaica Inn to the Big Screen appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 25, 2020

Kamala Das — Indian Poet and a Woman Ahead of Her Time

Kamala Das (1934 – 2009) started her career as a poet writing under the name of Madhavi Kutty. The renowned Indian author was bilingual and wrote in her mother tongue, Malayalam, as well as in English.

Born in Punnayurkulam, India as Kamala Surayya, she was better known in her home state of Kerala for her short stories and her autobiography, and in the rest of the country, for her English poetry. Her explosive autobiography, My Story, written in Malayalam (her native tongue), gained her both fame and notoriety. Later, it was translated into English.

Background

Born into a family where her parents had a literary background, she naturally inherited a disposition towards writing. Married at the age of 15 to a bank officer, Madhav Das, who encouraged her passion for writing, she found herself writing in two languages.

Kamala was fortunate to be located in the city of Calcutta, which in the 1960s afforded good opportunities for creative talent. She began to publish her work in cult anthologies, along with a budding generation of Indian English poets.

Kamala attended literary events in Germany, Jamaica, London and Canada, where she was invited to read her poetry. She also held literary positions in her state of Kerala and for a national daily. In 2009, the Times called her the “mother of modern English poetry.”

Among her many notable achievements are the Pen Asian Poetry Prize in 1963 and a nomination for the Nobel Prize in 1984. She also became a syndicated columnist expressing her views on women, children, and politics.

Kamala lived by her own terms all of her life, which is clearly visible in her writings.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

A bold poet

The first published book of collected poems by Kamala Das, Summer in Calcutta (1965) featured the ups and downs of romantic love. She opted to publish all her six volumes of poetry in English — though she did complain, “Poetry does not sell in this country” — referring to India.

Her poetic work could be classified under the genre of confessional poetry— not a common style for Indian poets, least of all women. She was quite the pioneer in this respect and also for using English to pen her verse. Her English poetry has been compared to that of Anne Sexton and won her both recognition and literary awards during her lifetime.

The poems cast a critical eye on Indian society, with its strong patriarchy and notions about how a woman should conduct herself. Interestingly, while her poetry is replete with feminist yearnings, there is a strong sense of spirituality running through them.

“Introduction,” is Kamala’s autobiographical poem in which she says she can recall the names of the men who dominate the politics of India and follows this up with a plea for her place in the sun, while likely stressing that her knowledge of languages indicates that she is as educated as a man.

I am Indian, born in Malabar,

I speak three languages, write in

Two, dream in one.

In subsequent verses, Kamala speaks of the angst of being told not to write in English, as it is not her mother tongue. These also suggest an interesting aspect of the ownership of language:

This language I speak,

Becomes mine, its distortions its queernesses,

All mine, mine alone.

The next verse explores her sorrow at being married to an older man whilst on the cusp of puberty, and how she felt used in the physicality of the relationship. The later verses bring out the sorrow of being forced to conform in all ways:

Be wife … be embroiderer, be cook … Fit in … belong …

Choose a name, a role. Don’t play pretending games.

The later verses go on to explore her sense of frustration of being hemmed into the family of her in-laws where she has to conform, whilst the men, including her husband, can just be themselves. She concludes:

I am sinner,

I am saint, I am the beloved and the

Betrayed. I have no joys that are not yours, no

Aches which are not yours. I too call myself.

This poem to some extent sums up the essence of Kamala Das, who all her life looked for equality and didn’t find it. She pinned her faith on a kind of spirituality, where she sought God (Krishna) in the natural beauty around her. In her poem, “Only the Soul Knows How to Sing,” she wrote:

Your body is my prison, Krishna

I cannot see beyond it.

Your darkness blinds me

Your love words shut out the wise world’s din.

. . . . . . . . . .

My Story by Kamala Das on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

My Story: A controversial autobiography

Kamala’s autobiography is penned so poignantly that any Indian woman might identify with the trials, tribulations, and burden of expectations from a society steeped in patriarchy. She was certainly an iconoclast and managed to carve a niche for herself with the sheer honesty of her writings.

The publishing of her autobiography, My Story, was originally in Malayalam called Ente Katha, brought her both publicity and criticism for its honesty about sexuality. Kamala did say later that she had adopted fictional elements in her story, but that didn’t prevent her from being censured for doing a striptease.

She replied in characteristic style saying that after she stripped off her skin and crushed her bones, people would perhaps be able to see “my homeless orphan, intensely beautiful soul, deep within the bone…”

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

. . . . . . . . . .

10 Classic Indian Women Authors

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Kamala Das

Reader discussion on Goodreads

Kamala Das — the Mother of Modern Indian Poetry

A selection of poetry by Kamala Das

The Rise and Fall of Kamala Das

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Kamala Das — Indian Poet and a Woman Ahead of Her Time appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 22, 2020

The Cry of the Children by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

“The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, first published in 1843, is an example of the esteemed British poet’s foray into the area of social protest poetry.

With the 19th century’s industrial revolution in full force, the poem forcefully decries the all-too-common exploitation of children as laborers, placing blame on both the social structures and institutions that allowed the practice to spread.

Here is an excellent, in-depth analysis of “The Cry of the Children” on LitCharts, which begins as follows:

“The poem was criticized then and is still sometimes viewed today as a deeply sentimental work, relying on stark stories of children’s suffering in an effort to tug on readers’ heartstrings. Nevertheless, the poem was a popular success, succeeding not just in exposing the exploitation of working-class children, but also in rallying greater public support for child labor reforms in industrial England.”

Poem Analysis provides much additional insight, beginning:

“Browning was inspired to write the poem after a report on the subject came out by the Royal Commission of Inquiry in Children’s Employment as well as a lifetime of writing about topics of her day and age … Readers should also take note of the epigraph that comes before the first line of the poem. It reads: ‘Pheu pheu, ti prosderkesthe m ommasin, tekna.‘ Meaning, ‘Alas, alas, why do you gaze at me with your eyes, my children.'”

. . . . . . . . .

See also: 10 Shorter Poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

. . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806 – 1861) was a respected and widely read British poet of the Victorian era. Tragedy and loss as well as great love marked her life. Many of her poems were incredibly long, some even book-length (such as Aurora Leigh).

She and her beloved husband and fellow poet Robert Browning belong to a circle of the most esteemed writers and thinkers of their time. During her lifetime, Elizabeth was better known than her husband. Her work fell out of favor for some time, but contemporary re-evaluation has once again elevated her work once again to the highest order of literary achievement.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Cry of the Children

“Pheu pheu, ti prosderkesthe m ommasin, tekna;”

(Alas, alas, why do you gaze at me with your eyes, my children. —Medea)

Do ye hear the children weeping, O my brothers,

Ere the sorrow comes with years?

They are leaning their young heads against their mothers, —

And that cannot stop their tears.

The young lambs are bleating in the meadows

The young birds are chirping in the nest

The young fawns are playing with the shadows

The young flowers are blowing toward the west—

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

They are weeping bitterly!

They are weeping in the playtime of the others,

In the country of the free.

Do you question the young children in the sorrow,

Why their tears are falling so?

The old man may weep for his to-morrow

Which is lost in Long Ago —

The old tree is leafless in the forest —

The old year is ending in the frost —

The old wound, if stricken, is the sorest —

The old hope is hardest to be lost

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

Do you ask them why they stand

Weeping sore before the bosoms of their mothers,

In our happy Fatherland?

They look up with their pale and sunken faces,

And their looks are sad to see,

For the man’s grief abhorrent, draws and presses

Down the cheeks of infancy —

“Your old earth,” they say, “is very dreary;”

“Our young feet,” they say, “are very weak!”

Few paces have we taken, yet are weary—

Our grave-rest is very far to seek!

Ask the old why they weep, and not the children,

For the outside earth is cold —

And we young ones stand without, in our bewildering,

And the graves are for the old!”

“True,” say the children, “it may happen

That we die before our time!

Little Alice died last year her grave is shapen

Like a snowball, in the rime.

We looked into the pit prepared to take her —

Was no room for any work in the close clay

From the sleep wherein she lieth none will wake her,

Crying, ‘Get up, little Alice! it is day.’

If you listen by that grave, in sun and shower,

With your ear down, little Alice never cries

Could we see her face, be sure we should not know her,

For the smile has time for growing in her eyes ,—

And merry go her moments, lulled and stilled in

The shroud, by the kirk-chime!

It is good when it happens,” say the children,

“That we die before our time!”

Alas, the wretched children! they are seeking

Death in life, as best to have!

They are binding up their hearts away from breaking,

With a cerement from the grave.

Go out, children, from the mine and from the city —

Sing out, children, as the little thrushes do —

Pluck you handfuls of the meadow-cowslips pretty

Laugh aloud, to feel your fingers let them through!

But they answer, ” Are your cowslips of the meadows

Like our weeds anear the mine?

Leave us quiet in the dark of the coal-shadows,

From your pleasures fair and fine!

“For oh,” say the children, “we are weary,

And we cannot run or leap —

If we cared for any meadows, it were merely

To drop down in them and sleep.

Our knees tremble sorely in the stooping —

We fall upon our faces, trying to go

And, underneath our heavy eyelids drooping,

The reddest flower would look as pale as snow.

For, all day, we drag our burden tiring,

Through the coal-dark, underground —

Or, all day, we drive the wheels of iron

In the factories, round and round.

“For all day, the wheels are droning, turning, —

Their wind comes in our faces, —

Till our hearts turn, — our heads, with pulses burning,

And the walls turn in their places

Turns the sky in the high window blank and reeling —

Turns the long light that droppeth down the wall, —

Turn the black flies that crawl along the ceiling —

All are turning, all the day, and we with all! —

And all day, the iron wheels are droning

And sometimes we could pray,

‘O ye wheels,’ (breaking out in a mad moaning)

‘Stop! be silent for to-day! ‘ ”

Ay! be silent! Let them hear each other breathing

For a moment, mouth to mouth —

Let them touch each other’s hands, in a fresh wreathing

Of their tender human youth!

Let them feel that this cold metallic motion

Is not all the life God fashions or reveals —

Let them prove their inward souls against the notion

That they live in you, or under you, O wheels! —

Still, all day, the iron wheels go onward,

As if Fate in each were stark

And the children’s souls, which God is calling sunward,

Spin on blindly in the dark.

Now tell the poor young children, O my brothers,

To look up to Him and pray —

So the blessed One, who blesseth all the others,

Will bless them another day.

They answer, ” Who is God that He should hear us,

While the rushing of the iron wheels is stirred?

When we sob aloud, the human creatures near us

Pass by, hearing not, or answer not a word!

And we hear not (for the wheels in their resounding)

Strangers speaking at the door

Is it likely God, with angels singing round Him,

Hears our weeping any more?

” Two words, indeed, of praying we remember

And at midnight’s hour of harm, —

‘Our Father,’ looking upward in the chamber,

We say softly for a charm.

We know no other words, except ‘Our Father,’

And we think that, in some pause of angels’ song,

God may pluck them with the silence sweet to gather,

And hold both within His right hand which is strong.

‘Our Father!’ If He heard us, He would surely

(For they call Him good and mild)

Answer, smiling down the steep world very purely,

‘Come and rest with me, my child.’

“But, no!” say the children, weeping faster,

” He is speechless as a stone

And they tell us, of His image is the master

Who commands us to work on.

Go to! ” say the children,—”up in Heaven,

Dark, wheel-like, turning clouds are all we find!

Do not mock us grief has made us unbelieving —

We look up for God, but tears have made us blind.”

Do ye hear the children weeping and disproving,

O my brothers, what ye preach?

For God’s possible is taught by His world’s loving —

And the children doubt of each.

And well may the children weep before you

They are weary ere they run

They have never seen the sunshine, nor the glory

Which is brighter than the sun

They know the grief of man, without its wisdom

They sink in the despair, without its calm —

Are slaves, without the liberty in Christdom, —

Are martyrs, by the pang without the palm, —

Are worn, as if with age, yet unretrievingly

No dear remembrance keep,—

Are orphans of the earthly love and heavenly

Let them weep! let them weep!

They look up, with their pale and sunken faces,

And their look is dread to see,

For they think you see their angels in their places,

With eyes meant for Deity—

“How long,” they say, “how long, O cruel nation,

Will you stand, to move the world, on a child’s heart, —

Stifle down with a mailed heel its palpitation,

And tread onward to your throne amid the mart?

Our blood splashes upward, O our tyrants,

And your purple shews your path

But the child’s sob curseth deeper in the silence

Than the strong man in his wrath!”

. . . . . . . . . .

More full-length poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning on this site

To Flush, My Dog

A Dead Rose

To George Sand, a Desire

The post The Cry of the Children by Elizabeth Barrett Browning appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 21, 2020

A Wagner Matinee by Willa Cather – 1904 short story (full text)

The short story “A Wagner Matinee” by Willa Cather was first published in the February, 1904 issue of Everybody’s Magazine. It became part of Cather’s first book of short stories, collected under the title The Troll Garden (1906). Following is the full text of “A Wagner Matinee.”

Plot summary

Clark, a young man living in Boston, finds out that his Aunt Georgiana is coming to town from Nebraska to settle an estate. As a younger woman, Georgiana was an esteemed music teacher at the Boston Conservatory. While on a trip to the Green Mountains of Vermont, she met Howard Carpenter, a man ten years younger than she. The two eloped and began a homestead in Nebraska.

It is now thirty years since she has been to Boston, and Clark remembers a visit to his aunt in Nebraska. He recalls how she introduced him to mythology, Shakespeare, and music.

In the course of his aunt’s visit to Boston, Clark takes her to a concert at the symphony. Georgiana is moved to tears by the power of Wagner’s music, including Tannhauser, Tristan und Isolde, and The Flying Dutchman. Georgiana confesses to Clark that she doesn’t want to return to Nebraska, and the life of hardship on the plains. Themes of loss, loneliness, struggle, and gratitude are woven through this brief and touching story.

Analyses of A Wagner Matinee

Sitting Bee

Anatoly’s

UK essays

. . . . . . . . .

Willa Sibert Cather (1873 – 1947) was a masterful American author of fiction whose spare yet evocative prose has held an enduring place in American literature.

Life on the prairie and the immigrant families she had encountered in her family’s adopted state of Nebraska inspired some of her earlier novels, including O Pioneers!, The Song of the Lark, and My Ántonia.

A Wagner Matinee by Willa Cather

I received one morning a letter, written in pale ink on glassy, blue-lined notepaper, and bearing the postmark of a little Nebraska village. This communication, worn and rubbed, looking as though it had been carried for some days in a coat pocket that was none too clean, was from my Uncle Howard and informed me that his wife had been left a small legacy by a bachelor relative who had recently died, and that it would be necessary for her to go to Boston to attend to the settling of the estate.

He requested me to meet her at the station and render her whatever services might be necessary. On examining the date indicated as that of her arrival I found it no later than tomorrow. He had characteristically delayed writing until, had I been away from home for a day, I must have missed the good woman altogether.

The name of my Aunt Georgiana called up not alone her own figure, at once pathetic and grotesque, but opened before my feet a gulf of recollection so wide and deep that, as the letter dropped from my hand, I felt suddenly a stranger to all the present conditions of my existence, wholly ill at ease and out of place amid the familiar surroundings of my study.

I became, in short, the gangling farm boy my aunt had known, scourged with chilblains and bashfulness, my hands cracked and sore from the corn husking. I felt the knuckles of my thumb tentatively, as though they were raw again. I sat again before her parlor organ, fumbling the scales with my stiff, red hands, while she, beside me, made canvas mittens for the huskers.

The next morning, after preparing my landlady somewhat, I set out for the station. When the train arrived I had some difficulty in finding my aunt. She was the last of the passengers to alight, and it was not until I got her into the carriage that she seemed really to recognize me. She had come all the way in a day coach; her linen duster had become black with soot, and her black bonnet gray with dust, during the journey. When we arrived at my boardinghouse the landlady put her to bed at once and I did not see her again until the next morning.

Whatever shock Mrs. Springer experienced at my aunt’s appearance she considerately concealed. As for myself, I saw my aunt’s misshapen figure with that feeling of awe and respect with which we behold explorers who have left their ears and fingers north of Franz Josef Land, or their health somewhere along the Upper Congo.

My Aunt Georgiana had been a music teacher at the Boston Conservatory, somewhere back in the latter sixties. One summer, while visiting in the little village among the Green Mountains where her ancestors had dwelt for generations, she had kindled the callow fancy of the most idle and shiftless of all the village lads, and had conceived for this Howard Carpenter one of those extravagant passions which a handsome country boy of twenty-one sometimes inspires in an angular, spectacled woman of thirty.

When she returned to her duties in Boston, Howard followed her, and the upshot of this inexplicable infatuation was that she eloped with him, eluding the reproaches of her family and the criticisms of her friends by going with him to the Nebraska frontier. Carpenter, who, of course, had no money, had taken a homestead in Red Willow County, fifty miles from the railroad.

There they had measured off their quarter section themselves by driving across the prairie in a wagon, to the wheel of which they had tied a red cotton handkerchief, and counting off its revolutions. They built a dugout in the red hillside, one of those cave dwellings whose inmates so often reverted to primitive conditions. Their water they got from the lagoons where the buffalo drank, and their slender stock of provisions was always at the mercy of bands of roving Indians. For thirty years my aunt had not been further than fifty miles from the homestead.

But Mrs. Springer knew nothing of all this, and must have been considerably shocked at what was left of my kinswoman. Beneath the soiled linen duster which, on her arrival, was the most conspicuous feature of her costume, she wore a black stuff dress, whose ornamentation showed that she had surrendered herself unquestioningly into the hands of a country dressmaker.

My poor aunt’s figure, however, would have presented astonishing difficulties to any dressmaker. Originally stooped, her shoulders were now almost bent together over her sunken chest. She wore no stays, and her gown, which trailed unevenly behind, rose in a sort of peak over her abdomen. She wore ill-fitting false teeth, and her skin was as yellow as a Mongolian’s from constant exposure to a pitiless wind and to the alkaline water which hardens the most transparent cuticle into a sort of flexible leather.

I owed to this woman most of the good that ever came my way in my boyhood, and had a reverential affection for her. During the years when I was riding herd for my uncle, my aunt, after cooking the three meals—the first of which was ready at six o’clock in the morning-and putting the six children to bed, would often stand until midnight at her ironing board, with me at the kitchen table beside her, hearing me recite Latin declensions and conjugations, gently shaking me when my drowsy head sank down over a page of irregular verbs.

It was to her, at her ironing or mending, that I read my first Shakespeare’, and her old textbook on mythology was the first that ever came into my empty hands. She taught me my scales and exercises, too—on the little parlor organ, which her husband had bought her after fifteen years, during which she had not so much as seen any instrument, but an accordion that belonged to one of the Norwegian farmhands.

She would sit beside me by the hour, darning and counting while I struggled with the “Joyous Farmer,” but she seldom talked to me about music, and I understood why. She was a pious woman; she had the consolations of religion and, to her at least, her martyrdom was not wholly sordid.

Once when I had been doggedly beating out some easy passages from an old score of Euryanthe I had found among her music books, she came up to me and, putting her hands over my eyes, gently drew my head back upon her shoulder, saying tremulously, “Don’t love it so well, Clark, or it may be taken from you. Oh, dear boy, pray that whatever your sacrifice may be, it be not that.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

Full text of “Paul’s Case: A Study in Temperament” by Willa Cather

. . . . . . . . . .

When my aunt appeared on the morning after her arrival she was still in a semi-somnambulant state. She seemed not to realize that she was in the city where she had spent her youth, the place longed for hungrily half a lifetime. She had been so wretchedly train-sick throughout the journey that she bad no recollection of anything but her discomfort, and, to all intents and purposes, there were but a few hours of nightmare between the farm in Red Willow County and my study on Newbury Street.

I had planned a little pleasure for her that afternoon, to repay her for some of the glorious moments she had given me when we used to milk together in the straw-thatched cowshed and she, because I was more than usually tired, or because her husband had spoken sharply to me, would tell me of the splendid performance of the Huguenots she had seen in Paris, in her youth.

At two o’clock the Symphony Orchestra was to give a Wagner program, and I intended to take my aunt; though, as I conversed with her I grew doubtful about her enjoyment of it. Indeed, for her own sake, I could only wish her taste for such things quite dead, and the long struggle mercifully ended at last.

I suggested our visiting the Conservatory and the Common before lunch, but she seemed altogether too timid to wish to venture out. She questioned me absently about various changes in the city, but she was chiefly concerned that she had forgotten to leave instructions about feeding half-skimmed milk to a certain weakling calf, “old Maggie’s calf, you know, Clark,” she explained, evidently having forgotten how long I had been away.

She was further troubled because she had neglected to tell her daughter about the freshly opened kit of mackerel in the cellar, which would spoil if it were not used directly.

I asked her whether she had ever heard any of the Wagnerian operas and found that she had not, though she was perfectly familiar with their respective situations, and had once possessed the piano score of The Flying Dutchman. I began to think it would have been best to get her back to Red Willow County without waking her, and regretted having suggested the concert.

From the time we entered the concert hall, however, she was a trifle less passive and inert, and for the first time seemed to perceive her surroundings. I had felt some trepidation lest she might become aware of the absurdities of her attire, or might experience some painful embarrassment at stepping suddenly into the world to which she had been dead for a quarter of a century. But, again, I found how superficially I had judged her.

She sat looking about her with eyes as impersonal, almost as stony, as those with which the granite Rameses in a museum watches the froth and fret that ebbs and flows about his pedestal-separated from it by the lonely stretch of centuries.

I have seen this same aloofness in old miners who drift into the Brown Hotel at Denver, their pockets full of bullion, their linen soiled, their haggard faces unshaven; standing in the thronged corridors as solitary as though they were still in a frozen camp on the Yukon, conscious that certain experiences have isolated them from their fellows by a gulf no haberdasher could bridge.

We sat at the extreme left of the first balcony, facing the arc of our own and the balcony above us, veritable hanging gardens, brilliant as tulip beds. The matinee audience was made up chiefly of women.

One lost the contour of faces and figures—indeed, any effect of line whatever—and there was only the color of bodices past counting, the shimmer of fabrics soft and firm, silky and sheer: red, mauve, pink, blue, lilac, purple, ecru, rose, yellow, cream, and white, all the colors that an impressionist finds in a sunlit landscape, with here and there the dead shadow of a frock coat. My Aunt Georgiana regarded them as though they had been so many daubs of tube-paint on a palette.

When the musicians came out and took their places, she gave a little stir of anticipation and looked with quickening interest down over the rail at that invariable grouping, perhaps the first wholly familiar thing that had greeted her eye since she had left old Maggie and her weakling calf.

I could feel how all those details sank into her soul, for I had not forgotten how they had sunk into mine when. I came fresh from plowing forever and forever between green aisles of corn, where, as in a treadmill, one might walk from daybreak to dusk without perceiving a shadow of change.

The clean profiles of the musicians, the gloss of their linen, the dull black of their coats, the beloved shapes of the instruments, the patches of yellow light thrown by the green-shaded lamps on the smooth, varnished bellies of the cellos and the bass viols in the rear, the restless, wind-tossed forest of fiddle necks and bows-I recalled how, in the first orchestra I had ever heard, those long bow strokes seemed to draw the heart out of me, as a conjurer’s stick reels out yards of paper ribbon from a hat.

The first number was the Tannhauser overture. When the horns drew out the first strain of the Pilgrim’s chorus my Aunt Georgiana clutched my coat sleeve. Then it was I first realized that for her this broke a silence of thirty years; the inconceivable silence of the plains.

With the battle between the two motives, with the frenzy of the Venusberg theme and its ripping of strings, there came to me an overwhelming sense of the waste and wear we are so powerless to combat; and I saw again the tall, naked house on the prairie, black and grim as a wooden fortress; the black pond where I had learned to swim, its margin pitted with sun-dried cattle tracks; the rain-gullied clay banks about the naked house, the four dwarf ash seedlings where the dishcloths were always hung to dry before the kitchen door.

The world there was the flat world of the ancients; to the east, a cornfield that stretched to daybreak; to the west, a corral that reached to sunset; between, the conquests of peace, dearer bought than those of war.

The overture closed; my aunt released my coat sleeve, but she said nothing. She sat staring at the orchestra through a dullness of thirty years, through the films made little by little by each of the three hundred and sixty-five days in every one of them. What, I wondered, did she get from it? She had been a good pianist in her day I knew, and her musical education had been broader than that of most music teachers of a quarter of a century ago.

She had often told me of Mozart’s operas and Meyerbeer’s, and I could remember hearing her sing, years ago, certain melodies of Verdi’s. When I had fallen ill with a fever in her house she used to sit by my cot in the evening—when the cool, night wind blew in through the faded mosquito netting tacked over the window, and I lay watching a certain bright star that burned red above the cornfield—and sing “Home to our mountains, O, let us return!” in a way fit to break the heart of a Vermont boy near dead of homesickness already.

I watched her closely through the prelude to Tristan and Isolde, trying vainly to conjecture what that seething turmoil of strings and winds might mean to her, but she sat mutely staring at the violin bows that drove obliquely downward, like the pelting streaks of rain in a summer shower.

Had this music any message for her? Had she enough left to at all comprehend this power which had kindled the world since she had left it? I was in a fever of curiosity, but Aunt Georgiana sat silent upon her peak in Darien. She preserved this utter immobility throughout the number from The Flying Dutchman, though her fingers worked mechanically upon her black dress, as though, of themselves, they were recalling the piano score they had once played.

Poor old hands! They had been stretched and twisted into mere tentacles to hold and lift and knead with; the palms unduly swollen, the fingers bent and knotted—on one of them a thin, worn band that had once been a wedding ring. As I pressed and gently quieted one of those groping hands I remembered with quivering eyelids their services for me in other days.

Soon after the tenor began the “Prize Song,” I heard a quick drawn breath and turned to my aunt.

Her eyes were closed, but the tears were glistening on her cheeks, and I think, in a moment more, they were in my eyes as well. It never really died, then— the soul that can suffer so excruciatingly and so interminably; it withers to the outward eye only; like that strange moss which can lie on a dusty shelf half a century and yet, if placed in water, grows green again. She wept so throughout the development and elaboration of the melody.

During the intermission before the second half of the concert, I questioned my aunt and found that the “Prize Song” was not new to her. Some years before there had drifted to the farm in Red Willow County a young German, a tramp cowpuncher, who had sung the chorus at Bayreuth, when he was a boy, along with the other peasant boys and girls.

Of a Sunday morning he used to sit on his gingham-sheeted bed in the hands’ bedroom which opened off the kitchen, cleaning the leather of his boots and saddle, singing the “Prize Song,” while my aunt went about her work in the kitchen. She had hovered about him until she had prevailed upon him to join the country church, though his sole fitness for this step, insofar as I could gather, lay in his boyish face and his possession of this divine melody.

Shortly afterward he had gone to town on the Fourth of July, been drunk for several days, lost his money at a faro table, ridden a saddled Texan steer on a bet, and disappeared with a fractured collarbone. All this my aunt told me huskily, wanderingly, as though she were talking in the weak lapses of illness.

“Well, we have come to better things than the old Trovatore at any rate, Aunt Georgie?” I queried, with a well-meant effort at jocularity.

Her lip quivered and she hastily put her handkerchief up to her mouth. From behind it she murmured, “And you have been hearing this ever since you left me, Clark?” Her question was the gentlest and saddest of reproaches.

The second half of the program consisted of four numbers from the Ring, and closed with Siegfried’s funeral march. My aunt wept quietly, but almost continuously, as a shallow vessel overflows in a rainstorm. From time to time her dim eyes looked up at the lights which studded the ceiling, burning softly under their dull glass globes; doubtless they were stars in truth to her.

I was still perplexed as to what measure of musical comprehension was left to her, she who had heard nothing but the singing of gospel hymns at Methodist services in the square frame schoolhouse on Section Thirteen for so many years. I was wholly unable to gauge how much of it had been dissolved in soapsuds, or worked into bread, or milked into the bottom of a pail.

The deluge of sound poured on and on; I never knew what she found in the shining current of it; I never knew how far it bore her, or past what happy islands. From the trembling of her face I could well believe that before the last numbers she had been carried out where the myriad graves are, into the gray, nameless burying grounds of the sea; or into some world of death vaster yet, where, from the beginning of the world, hope has lain down with hope and dream with dream and, renouncing, slept.

The concert was over; the people filed out of the hall chattering and laughing, glad to relax and find the living level again, but my kinswoman made no effort to rise. The harpist slipped its green felt cover over his instrument; the flute players shook the water from their mouthpieces; the men of the orchestra went out one by one, leaving the stage to the chairs and music stands, empty as a winter cornfield.

I spoke to my aunt. She burst into tears and sobbed pleadingly. “I don’t want to go, Clark, I don’t want to go!”

I understood. For her, just outside the door of the concert hall, lay the black pond with the cattle-tracked bluffs; the tall, unpainted house, with weather-curled boards; naked as a tower, the crook-backed ash seedlings where the dishcloths hung to dry; the gaunt, molting turkeys picking up refuse about the kitchen door.

The post A Wagner Matinee by Willa Cather – 1904 short story (full text) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 19, 2020

The Betsy-Tacy Books by Maud Hart Lovelace: An Appreciation

Revisiting the Deep Valley novels by Maud Hart Lovelace (1892 – 1980) during the winter holiday season is a particular delight, though this American author’s stories can be enjoyed year-round. Perhaps better known as the Betsy-Tacy books, the themes celebrated in these nostalgic novels for young readers are universal: friendship, devotion, love of home, ambition, and comfort.

Though the novels were published in the 1940s, they take place in the early years of the twentieth century, when the author herself was growing up. As young girls, her well-known heroines—Betsy, Tacy, and Tib—have ten cents to spend on Christmas shopping. As they grow up, in Betsy and Joe (1948), for instance, they have “real shopping” to do, but their trip downtown is as “heavily weighted with tradition as a Christmas pudding with plums.”

They visit every store (including Cook’s Book Store) and price “everything from diamonds to gumdrops, and bought, each one, a Christmas tree ornament … savoring Christmas together all up and down Front Street.” It’s a simple and comforting ritual.

Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy-Tacy books were based on her experiences growing up in Mankato, Minnesota. The Betsy-Tacy Companion by Sharla Scannell Whalen even contains a helpful chart that displays the names of the novels’ main characters alongside their real-life corollaries. But the enduring appeal of this series rests as much with their invented elements as their real-life, autobiographical links.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about

Maud Hart Lovelace

. . . . . . . . .

Friendship

In real life, Betsy is Maud Hart Lovelace, the author herself. Tacy is Anna Anastacia’s nickname; she was based on Maud’s friend Frances ‘Bick’ Kenny. They meet at Betsy’s (and Maud’s) fifth birthday party.

In Betsy-Tacy (1940), they decorate eggs for Easter, with the help of older sisters Julia and Katie. They walk to school together every morning, even when it’s so cold and snowy that their hands ache inside their mittens.

They dream of buying the chocolate-colored house, when they earn two nickels—but eventually, Tib moves in. The actual chocolate-colored house was much like Tib’s house (Tib was based on Maud’s friend Midge Gerlach), except that there was no tower, and in this volume, there’s no Tib, either. (Another neighborhood house did have a tower though. Wasn’t it Toni Morrison who said that one must write the stories one yearns to read? One must write about houses with towers, too, then.)

Betsy and Tacy accommodate Tib, naturally. In Betsy-Tacy and Tib (1941), the girls are eight years old and fast friends: “Tib was always pointing things out. But Betsy and Tacy liked her just the same.” This allows readers to adjust to Tib’s presence, to create a space for her, just as the other girls do.

Tib is the smallest and, arguably, the sharpest. She is also the best at flying, as the girls come to learn. Because even though it was Betsy’s idea, Betsy invents a story to tell, rather than take the plunge like the other two girls did (reluctantly but determinedly). Even so, the friends are inseparable.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Devotion

Beyond the celebrated central friendship between the three girls, there are other sustained friendships. For instance, between Betsy’s and Tacy’s older sisters, and the friendships between the principle girls and certain neighborhood boys (some of whom—like Cab Edwards—remind me of Laurie in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women stories). Friendship almost seems too simplistic a concept in Maud Hart Lovelace’s books: these are dedicated, lifelong relationships.

The loving and warm relationship between Betsy’s parents is based on observations of her own mother and father, Stella, and Tom. Although Jule and Bob Ray do not always see eye-to-eye in the series, their temperaments are even and their motives true; they enjoy one another’s company consistently (with many jokes and much good-natured teasing).

The series’ final volume, Betsy’s Wedding (1955) has Betsy’s fiancé declaring: “I want to be married to you and have you around all the time. I want to come home to you after work and tell you about my day. I want to hear you humming around, doing housework. I want to support you. I want to do things for you. If we were married and I was coming home to you tonight, I wouldn’t care if we had just bread and milk.”

But there are other instances of loyalty and commitment in the series as well: support offered to relatives near and far, parents sacrificing to ensure that a child can pursue her talents, teachers who monitor Betsy’s progress and offer appropriate opportunities, the librarian who makes regular recommendations to the budding writer, and Anna, the cook, who leaves a well-established family to work for the Ray family instead (in real life, there was an Anna, but she did not stay long with the Hart family).

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Love of home

Heaven to Betsy (1945) opens with Betsy spending two weeks of the summer holiday away from home; she stays with the Taggart family on a nearby farm, to put some color in her cheeks. At fourteen years old, this is her first independent visit and her homesickness is overwhelming.

When she finally returns, she learns that the Ray family is leaving Hill Street behind and moving to a new house at the “windy junction” of High Street and Plum Street: “Betsy thought her heart would break. Didn’t they know how much she loved that coal stove beside which she had read so many books while the tea kettle sang and the little flames leaped behind the isinglass window?”

It’s not just the Ray family that calls Deep Valley and its environs home. When the girls enjoy a private picnic the summer they turn ten, they discover a community of newcomers within walking distance in Betsy and Tacy Go over the Big Hill (1942). In Little Syria, and they meet a girl close to their age.

In Little Syria, the food and drink are unfamiliar to the girls: people smoke and play flutes, give the girls raisins and figs for snacks, and sign their names in Arabic. But not everyone in Deep Valley is accepting and when Naifi is bullied. Tib (then Tacy and, finally, Betsy) intervene:

“I’m glad Tib stood up for the little Syrian girl. Foreign people should not be treated like that. America is made up of foreign people. Both of Tib’s grandmothers came from the other side. Perhaps when they got off the boat they looked a little strange too.”

. . . . . . . . .

Quotations from the Betsy-Tacy Books

. . . . . . . . .

Ambition

Even though Betsy travels in her sister’s footsteps in the series’ penultimate volume — Betsy and the Great World (1952) — it’s her older sister, Julia, who is passionate about the arts and pursuing a career in opera. Julia dreams of exploring Europe the way that the younger girls dreamed of exploring the other side of the hill.

In Betsy in Spite of Herself (1946), Betsy observes that Julia seems to belong to the Great World already, that courting and her beau will not be the end of her personal story. Julia’s passion is opera:

“The next was La Boheme! I saw Geraldine Farrar come in with her candle. I heard her sing ‘Mi chiamano Mimi.’ Oh, Bettina how I cried! And I knew then. Cavalleria and Pagliacci only made me surer, and so did Aïda, although that’s pretty hard, too. Not like Wagner, of course. He’s just the ultimate.”

Betsy’s dedication to her writing has a similar prominence and her parents celebrate her efforts as seriously as they support Julia’s ambitions. The first book in which her writing is central is Betsy and Tacy Go Downtown (1943), which is often cited as a favorite in the series (perhaps as much for Miss Poppy’s colorful personality, with her husband owning the Melborn Hotel and running the theater). “Betsy waved to the big desk. ‘I write stories,’” Betsy exclaims later in the series.

. . . . . . . . . .

Maud Hart Lovelace books on bookshop.org*

Maud Hart Lovelace page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Comfort

The Rays and readers salivate when Anna takes the position of the family’s cook: her cinnamon buns are legendary and she bakes a mean ginger cookie too. When a Ray daughter returns from a trip, she can expect any number of indulgences: “Anna’s muffins, and the choicest jams and jellies her mother had put up over the summer.”

Throughout the series, picnic fixings and the ritual of Mr. Ray’s sandwich nights (onion and vinegar concoctions on Sundays, designed to give the women a break from cooking) are a pleasure. A summer picnic might be like this: “They set out on one of the long tables potato salad, potted meat, sandwiches, hard-boiled eggs, a chocolate cake, a cocoanut cake, and a jug of lemonade.” (There are winter picnics too.)

And, for special occasions, at the Moorish Café, the family enjoys “oyster cocktails, and then soup, and then fish, and then turkey, and then salad, and then dessert … pie, ice cream or Delmonico pudding.”

Mrs. Taggart packs a fine lunch for Betsy for her trip home: “It was magnificent; ham sandwiches, dill pickles, hard-boiled eggs, a chunk of layer cake and cookies.” Betsy and her friend, Bonnie, raid the Andrews’ icebox for “cheese, apples, olives, cookies, cold ham, and some of Mrs. Andrews’ famous little mince pies” to have a hen party, complete with Ouija board. And there are remarkable banana splits at Heinz’s Restaurant and evening gatherings with freshly made fudge.

As the series wends on, the girls become old enough to host their own gatherings. While her parents are away, in Betsy Was a Junior (1947), Betsy,Tacy, and Tib hurry home from school, put on their party dresses, and host: “Balancing plates full of chicken salad, hot rolls, World’s Fair pickles and coffee, and second plates with ice cream and angel food cake, they nevertheless found time to smile at the mothers of their friends. Boys’ mothers were particularly fascinating.”