Nava Atlas's Blog, page 46

February 4, 2021

Frankie Addams: Coming of Age in Carson McCullers’ The Member of the Wedding

Like Mick Kelly of The Heart is a Lonely Hunter and her author, Carson McCullers, Frankie Addams is a tall, gangling tomboy. This in-depth look at the complicated young heroine of The Member of the Wedding (the 1946 novel) is excerpted from Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth.

“ … She was almost a big freak, and her shoulders were narrow, the legs too long … Her hair had been cut like a boy’s, but it had not been cut for a long time and was now not even parted.” At the age of ‘twelve and five-sixths’ Frankie is five feet five and three-quarter inches tall and wears size seven shoes.

“In the past year she had grown four inches, or at least that was what she judged. Already the hateful little summer children hollered to her: ‘Is it cold up there?’ Frankie calculates that ‘unless she could somehow stop herself, she would grow to be over nine feet tall.”

Unlike Mick, however, Frankie doesn’t feel part of any community or family. She has no mother – again, there is an absence of a mother figure – a distant father who is always at work and a much older brother who is away in the army (the highly successful play that McCullers made from the novel specifies the setting as August 1945, at the end of the Second World War).

“It happened that green and crazy summer when Frankie was twelve years old. This was the summer when for a long time she had not been a member. She belonged to no club and was a member of nothing in the world. Frankie had become an unjoined person who hung around in doorways, and she was afraid.”

Frankie is not a member of the club of thirteen and fourteen-year-old girls at school who have “parties with boys on Saturday night. Frankie knew all of the club members, and until this summer she had been like a younger member of the crowd, but now they had this club and she was not a member. They said she was too young and mean.”

The sympathetic BereniceThe only people with whom Frankie has close contact are Berenice Sadie Brown, who has been ‘the cook since Frankie could remember,’ and Frankie’s six-year-old cousin John Henry; much of the novel and the play, which both take place in a very short timescale, are spent with the three of them around the kitchen table.

Like Portia in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, Berenice is a very sympathetically-drawn Black female character from a time when white authors largely avoid African-Americans; she was played to great acclaim in the first production of the stage version of The Member of the Wedding, which opened on December 22, 1949 in Philadelphia, by local actress and jazz/blues singer Ethel Waters, who ten years earlier had been the first African-American to star in her own television show.

Frankie was played by a very young-looking, twenty-three-year-old Julie Harris, whose hair was cropped to make her look younger and more tomboyish; the day before the opening night the director asked to cut it even shorter and to do it herself, as Frankie had done. Harris went on to be nominated for an Academy Award for playing the same role in the 1952 film of the play, in which Ethel Waters also starred.

McCullers was concerned about racial balance in her work, and Berenice Sadie Brown may be based partly on the maid, Lucille, her family had when she was young. In her autobiography, McCullers tells the story of how Lucille, when ‘she was only fourteen and a marvelous cook, had called a cab to go home.’

When the taxi driver arrived, he shouted, ‘I’m not driving no damn …’ [the rest can be imagined] “People, kind, sweet people who had nursed us so tenderly, humiliated because of their color… We were exposed so much to the sight of humiliation and brutality, not physical brutality, but the brutal humiliation of human dignity which is even worse. Lucille comes back to me over and over; gay, charming Lucille.”

. . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

The wedding of which Frankie wants to be a member is happening in a few days in Winter Hill and Frankie cannot wait to go – unlike Mick, who is firmly anchored in her community, Frankie cannot wait to go anywhere away from where she is.

“I wish tomorrow was Sunday instead of Friday. I wish I had already left town.”

“Sunday will come,’ said Berenice.

“I doubt it,’ said Frankie. ‘I’ve been ready to leave this town so long. I wish I didn’t have to come back here after the wedding. I wish I was going somewhere for good. I wish I had hundred dollars and could just light out and never see this town again.”

“It seems to me you wish for a lot of things,” said Berenice.

“I wish I was somebody else except me.”

This was the summer that “Frankie was sick and tired of being Frankie. She hated herself, and had become a loafer and a big no-good who hung around the summer kitchen: dirty and greedy and mean and sad.”

Frankie has become aware of the outside world, not like “a round school globe,” but as ‘huge and cracked and loose and turning a thousand miles an hour.’ She is aware of the war, of Patton “chasing the Germans across France,” though it is “happening so fast that sometimes she did not understand.”

Frankie wants to join something, anything — but she cannot join the war. She wants to donate blood to the Red Cross so that the army doctors would say that “the blood of Frankie Addams was the reddest and strongest blood that they had ever known,” but the Red Cross say she is too young. Frankie feels “left out of everything … She was afraid because in the war they would not include her, and because the world seemed somehow separate from herself.”

All these things made her “suddenly wonder who she was, and what she was going to be in the world;” who is this “great big long-legged twelve-year-old blunderbuss who still wants to sleep with her old Papa.” But she is now too old to sleep with her father and sleeps alone in her room, a member of nothing. Her best friend has moved away to Florida and “Frankie did not play with anybody any more.”

Going astray

It was also this summer that Frankie had become a criminal, at least in her own mind. She had taken her father’s gun from the drawer and gone out shooting with it on a vacant lot. She had also stolen a knife from the Sears and Roebuck store, but one sin had been worse than any of them.

One Saturday afternoon in May she committed a secret and unknown sin. In the MacKeans’ garage, with Barney MacKean, they committed a queer sin, and how bad it was she did not know. The sin made a shriveling sickness in her stomach, and she dreaded the eyes of everyone. She hated Barney and wanted to kill him. Sometimes alone in the bed at night she planned to shoot him with the pistol or throw a knife between his eyes.

Like Mick Kelly, after she has committed what we assume is the same sin, Frankie is afraid that people will see the difference in her, afraid of “the eyes of everyone.” After a while though this unspecified sin “became far from her and was remembered only in her dreams.”

. . . . . . . . .

The Member of the Wedding was adapted to film in 1952 and 1997

. . . . . . . . .

The imminent wedding makes Frankie even more aware of her separateness. Her brother and his bride are hundred miles away: “They were them and in Winter Hill, together, while she was her and in the same old town all by herself.”

This is when Frankie has the revelation: she can be a member of something, a member of the wedding. McCullers comes up with one of the greatest sentences in coming-of-age literature:

“They are the we of me. Yesterday, and all the twelve years of her life, she had only been Frankie. She was an I person who had to walk around and do things by herself. All the other people had a we to claim, all other except her. When Berenice said we, she meant Honey and Big Mama, her lodge, or her church. The we of her father was the store. All members of clubs have a we to be-long to and talk about.

The soldiers in the army can say we, and even the criminals on chain-gangs. But the old Frankie had no we to claim, unless it could be the terrible summer we of her and John Henry and Berenice – and that was the last we in the world she wanted. Now all this was suddenly over with and changed. There was her brother and the bride, and it was as though when first she saw them something she had known inside of her: They are the we of me.”

For a moment Frankie believes she has come of age: “It was just at that moment that Frankie understood. She knew who she was and how she was going into the world.” But of course Frankie does not understand. She cannot be a member of the wedding, she cannot be the third person in a couple.

“I’m going off with the two of them to whatever place that they will ever go. I’m going with them … It’s like I’ve known it all my life, that I belong to be with them. I love the two of them so much.” Noting that her brother’s name is Jarvis and his fiancée is Janice she has already decided to change her name to F. Jasmine Addams.

“Jarvis and Janice and Jasmine. See?” she says to Berenice, but Berenice does not understand. Berenice asks what she will do if the couple don’t accept her. “If they don’t, I will kill myself,” she says, with “the pistol that Papa keeps under his handkerchief along with Mother’s picture.”

. . . . . . . . .

Literary Tomboys in Coming of Age Novels

. . . . . . . . .

F. Jasmine does not even discuss any of this with her brother, whom she has not seen for two years – we never see him at all: neither he nor his fiancée appear first-hand in the novel. But still she walks around the town “as a sudden member … entitled as a Queen … It was the day when, from the beginning, the world seemed no longer separate from herself and when all at once she felt included.”

Frankie is now so bold that she goes to a hotel room with a soldier – McCullers does not make explicit the fact that her brother is also a soldier and perhaps her desire to be a “member” of her brother and his new wife extends, if only subliminally, to the physical. Frankie has never met the soldier before and does not even find out his name. He seems not to realize how young she is and assumes she is a prostitute. Having got herself into a difficult situation, she does not know how to get out of it.

F. Jasmine did not want to go upstairs, but she did not know how to refuse. It was like going into a fair booth, or fair ride, that once having entered you cannot leave until the exhibition or the ride is finished. Now it was the same with the soldier, this date. She could not leave until it ended. The soldier was waiting at the foot of the stairs and, unable to refuse, she followed after him.

Once upstairs, neither of them seems at first to know what to do next.

“Already F. Jasmine had started for the door, for she could no longer stand the silence. But as she passed the soldier, grasped her skirt and limpened by fright, she was pulled down beside him on the bed. The next minute happened, but it was too crazy to be realized. She felt his arms around her and smelled his sweaty shirt. He was not rough, but it was crazier than if he had been rough – and in a second she was paralyzed by horror.

She could not push away, but she bit down with all her might upon what must have been the crazy soldier’s tongue – so that he screamed out and she was free. Then he was coming towards her with an amazed pained face, and her hand reached the glass pitcher and brought it down upon his head … He lay there still, with the amazed expression on his freckled face that was now pale, and a froth of blood showed on his mouth. But his head was not broken, or even cracked, and whether he was dead or not she did not know.”

Fortunately for F. Jasmine the soldier is not dead. She goes to the wedding as she had planned but nothing else goes according to plan. She cannot explain to them about the we of me and can only say: “Take me! And they pleaded and begged with her, but she was al-ready in the car. At the last she clung to the steering wheel until her father and somebody else had hauled and dragged her from the car.” The wedding party drives off without her and she is left “in the dust of the empty road,” still calling out: “Take me! Take me!”

In the third part of the narration she is now called Frances; she had started as the tomboy Frankie, then briefly became the delusional F. Jasmine, but Frances seems to be her coming of age name, her woman’s name. Berenice talks to her kindly.

Frances could not stand the kind tone. “I never meant to go with them!” she said. “It was all just a joke. They said they were going to invite me to visit when they get settled, but I wouldn’t go. Not for a million dollars.”

The sense of separateness continues

But though her delusion has been shattered and she has come of age, Frances still returns the next day to the feeling of separateness. “There had been a time, only yesterday, when she felt that every person she saw was somehow connected with herself,” but now she sees the world again as something separate from her.

Having left her father a note saying she is leaving, Frances ends up back in the sleazy hotel where she had been with the soldier, but now a policeman is there; it turns out that her father has asked the police to try to find her. The Law, as she thinks of him, asks her what he is doing there.

“What am I doing in here?” she repeated. For all at once she had forgotten, and she told the truth when she said finally, “I don’t know.”

The voice of the Law seemed to come from a distance like a question asked through a long corridor. “Where were you heading for?”

The world was now so far away that Frances could no longer think of it. She did not see the earth as in the old days, cracked and loose and turning a thousand miles an hour; the earth was enormous and still and flat. Between herself and all the places there was a space like an enormous canyon she could not hope to bridge or cross.

The novel ends quite suddenly with a flash forward: we are told that she has met a new friend, Mary Littlejohn, and that John Henry has died of meningitis. “She remembered John Henry more as he used to be, and it was seldom now that she felt his presence – solemn, suffering, and ghost-grey.”At the very end her father has had a letter from her brother, who is now stationed in Luxembourg.

“Luxembourg. Don’t you think that’s a lovely name?”

Berenice roused herself. “Well, Baby – it brings to my mind soapy water. But it’s a kind of pretty name.”

“There is a basement in the new house. And a laundry room.” She added, after a minute, “We will most likely pass through Luxembourg when we go around the world together.”

Frances turned back to the window. It was almost five o’clock and the geranium glow had faded from the sky. The last pale colors were crushed and cold on the horizon. Dark, when it came, would come on quickly, as it does in wintertime. “I am simply mad about—”

But the sentence was left unfinished for the hush was shattered when, with an instant shock of happiness, she heard the ringing of the bell.

More literary tomboys to explore in Girls in Bloom Charlie Laborde ( Charlie by Kate Chopin , 1900)Peggy Vaughan (A Terrible Tomboy by Angela Brazil, 1904)Irene Ashleigh (A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls by LT Meade, 1913) Petrova Fossil (Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfeild, 1932)George Fayne (The Secret of Red Gate Farm by ‘Caroline Keene’, 1931)George Kirrin (Five On a Treasure Island by Enid Blyton, 1942)Mick Kelly (The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers, 1940). . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

More about The Member of the Wedding Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads 1952 film of The Member of the Wedding All-American Loneliness and a Universe of Yearning 1997 made for television film*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Frankie Addams: Coming of Age in Carson McCullers’ The Member of the Wedding appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 1, 2021

5 Early English Women Writers to Discover

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf espoused the cause of the playwright and novelist Aphra Behn (1640 – 1689) as the great precursor of free women writers — though the first book in English was written by Julian of Norwich, the first autobiography was written by Margery Kempe, the first playwright and female poet since antiquity was Hrotsvitha, and the first professional woman writer was probably Christine of Pizan. And we can’t leave out Sappho, the ancient Greek poet.

Presented here are five early English women writers who may not be as well known as Aphra Behn, though each came before her, and set the stage for those who came after — Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe, Jane Anger, Æmalia Lanyer, and Margaret Cavendish.

. . . . . . . . .

Julian of Norwich

The first book written in the modern English language, Revelations of Divine Love, was begun in 1373 by a woman: the abbess Julian of Norwich; it famously repeats the phrase, ‘all shall be well and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.’ Like some of her predecessors and successors, Julian transgressively insisted that being a woman was no bar to writing about the love of God. ‘But for I am a woman should I therefore live that I should not tell you the goodness of God?’

Following her near death from a serious illness at the age of thirty, Julian began to receive revelations or ‘Shewings’ which she believed came straight from God without any ‘mean’ [intermediary].

This transgresses, as do the revelations of all the female mystics, the Catholic idea that God would only speak to the people through a male priest, and in Latin at that. It was men like Luther and Calvin objecting to this idea that led to the Reformation and Protestantism, though the Wycliffe and Tyndale Bibles in English and the Lollards of the late fourteenth century, Julian’s contemporaries, had preceded them. Like other female mystics, Julian stressed the Virgin Mary’s status as the most perfect human; a woman superior in grace to any man.

In this [Shewing] He brought our blessed Lady to my understanding. I saw her ghostly, in bodily likeness: a simple maid and a meek, young of age and little waxen above a child, in the stature that she was when she conceived. Also God shewed in part the wisdom and the truth of her soul: wherein I understood the reverent beholding in which she beheld her God and Maker, marvelling with great reverence that He would be born of her that was a simple creature of His making. . . I understood soothly that she is more than all that God made beneath her in worthiness and grace; for above her is nothing that is made but the blessed [Manhood] of Christ.

. . . . . . . . .

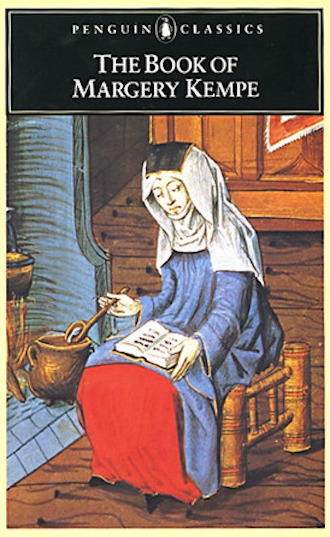

Margery Kempe

Shortly after Julian wrote the first book in English, Margery Kempe began a work in 1436 that also transgressed ideas of what a woman should do and say, in what would become the first autobiography in English: compiled over many years it became known simply as The Book of Margery Kempe.

As she makes clear, Kempe could neither read nor write and struggled to find someone to write down her experiences. Kempe eventually found a priest who was willing to write it out legibly from the various existing badly-written sections, ‘asking him to write this book and never to reveal it as long as she lived, granting him a great sum of money for his labour.’

Because of the ad hoc nature of its composition, ‘this book is not written in order, every thing after another as it was done, but just as the matter came to this creature’s mind when it was to be written down, for it was so long before it was written that she had forgotten the time and the order when things occurred.’

Kempe refers to herself throughout in the third person, mostly as ‘this creature.’ Like Julian and the other mystics she claims her revelations came directly from God, after she had been led astray by devils.

‘She slandered her husband, her friends, and her own self. She spoke many sharp and reproving words; she recognized no virtue nor goodness; she desired all wickedness.’ Jesus then appeared to her, ‘clad in a mantle of purple silk, sitting upon her bedside.’ After this Margery wanted to devote herself entirely to God, at the expense of sexual relations with her husband; transgressively she refuses her husband his conjugal rights.

And after this time she never had any desire to have sexual intercourse with her husband, for paying the debt of matrimony was so abominable to her that she would rather, she thought, have eaten and drunk the ooze and muck in the gutter than consent to intercourse.

Kempe wants to make a vow of chastity and regrets being married. ‘Ah, Lord, maidens are now dancing merrily in heaven. Shall I not do so? Because I am no virgin, lack of virginity is now great sorrow to me.’ But God forgives her. ‘Ah, daughter, how often have I told you that your sins are forgiven you and that we are united.’ But her husband has become so afraid that he does not even try to have sex with her anymore:

… Then she said with great sorrow, ‘Truly, I would rather see you being killed, than that we should turn back to our un-cleanness.’

And he replied, ‘You are no good wife.’

And then she asked her husband what was the reason that he had not made love to her for the last eight weeks, since she lay with him every night in his bed. And he said that he was made so afraid when he would have touched her, that he dared do no more.

. . . . . . . . .

Jane Anger

Like many of the works written by transgressive women, Her Protection for Women (1585) by Jane Anger (1560 – 1600) was addressed explicitly to an audience of other women. It was probably the first book-length defence of women’s place in society to be published in English. In 1558, the Scots preacher John Knox had published The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women. The appropriately-named Anger’s book was the first blast of women in return and very angry indeed.

To all Women in general,

and gentle Reader whatsoever.

FIE on the falshood of men, whose minds go oft a madding, & whose tongues can not so soon be wagging, but straight they fall a railing. Was there ever any so abused, so slandered, so railed upon, or so wickedly handled undeservedly, as are we women? . . But judge what the cause should be, of this their so great malice towards simple women.

Doubtless the weakness of our wits, and our honest bashfulness, by reason whereof they suppose that there is not one amongst us who can, or dare reprove their slanders and false reproaches: their slanderous tongues are so short, and the time wherein they have lavished out their words freely, hath been so long, that they know we cannot catch hold of them to pull them out, and they think we will not write to reprove their lying lips.

Like other transgressive, pre-feminist writers going back to Hildegard of Bingen, Anger claims that Eve’s original transgression is more than balanced by the Virgin Mary’s grace, bestowed upon her by God. Again, she is specifically addressing a female audience.

And now (seeing I speak to none but to you which are of mine own Sex,) give me leave like a scholar to prove our wisdom more excellent then theirs, though I never knew what sophistry meant. There is no wisdom but it comes by grace, this is a principle, & Contra principium non est disputandum: but grace was first given to a woman, because to our lady: which premises conclude that women are wise. Now Primum est optimum, & therefore women are wiser than men.

GOD making woman of man’s flesh, that she might be purer then he, doth evidently show, how far we women are more excellent then men. Our bodies are fruitful, whereby the world increaseth, and our care wonderful, by which man is preserved. From woman sprang man’s salvation. A woman was the first that believed, & a woman likewise the first that repented of sin.

. . . . . . . . .

Æmelia Lanyer

Æmalia Lanyer, or Emilia Lanier (1569 – 1645), is said to be the first English woman to publish a book, though she was in fact preceded by Isabella Whitney; but Whitney only published a pamphlet, mostly comprising poetry written by others, including the Cornish woman Anne Dowriche, and the Scot Elizabeth Melville.

Nevertheless, Lanier was the first British woman to assert her status as a professional writer, though her book of poems Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, published in 1611 when she was forty-two, is advertised as being by a wife. ‘Written by Mistris Æmilia Lanyer, Wife to Captaine Alfonso Lanyer, Seruant to the Kings Majestie.’

The book is addressed specifically to women and dedicated to several female aristocrats, seeking their patronage woman to woman, begging pardon for her ‘defects.’ They include a dedication ‘To the Queenes most Excellent Majestie’.

Renowned Empresse, and great Britaines Queene,

Most gratious Mother of succeeding Kings;

Vouchsafe to view that which is seldome seene,

A Womans writing of diuinest things:

Reade it faire Queene, though it defectiue be,

Your Excellence can grace both It and Mee. . .

And since all Arts at first from Nature came,

That goodly Creature, Mother of Perfection,

Whom Ioues almighty hand at first did frame,

Taking both her and hers in his protection:

Why should not She now grace my barren Muse,

And in a Woman all defects excuse.

Lanier was born Aemilia Bassano, a member of the Venetian Bassano family of musical instrument makers who lived and worked in London and has been a candidate for Shakespeare’s Dark Lady. The thrust of her book is female virtue and obedience to God’s will; in this sense she is no bad girl. But, like Jane Anger before her and Margaret Cavendish later, Lanier complains that it is unfair that, because of Eve, ‘we (poore women) must endure it all.’ Eve cannot be blamed for man’s fall.

And ‘If Eue did erre, it was for knowledge sake,’ and in any case, Adam ate too: ‘The fruit beeing faire perswaded him to fall: / No subtill Serpents falshood did betray him.’ Adam wanted to share in the knowledge which eating the fruit gave Eve; human knowledge comes from Eve but men have claimed it. ‘Men will boast of Knowledge, which he tooke / From Eues faire hand, as from a learned Booke.’ The evil was not in Eve, who was, quite literally, made from Adam, but in men’s betrayal of God’s intentions.

Like many other women writers, Lanier extols at length the obedient virtue of the Virgin Mary, who more than compensates for any sins of Eve. But, also like other women writers, she also extols strong women in history who have physically overcome powerful men, Like the Scythian Women, or Amazons.

Lanier also mentions with approval the biblical judge and prophet Deborah and the great pre-feminist Judith, who cut off the head of Holofernes before he could rape her and so set her people free, though what Lanier is celebrating in Judith’s act is a woman defeating a man who has ignored God’s will rather than a woman’s:

Yea Judeth had the powre likewise to queale

Proud Holifernes, that the just might see

What small defence vaine pride and greatnesse hath

Against the weapons of Gods word and faith.

. . . . . . . . .

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle

Men are so Unconscionable and Cruel against us, as they Endeavour to Bar us of all Sorts or Kinds of Liberty, as not to Suffer us Freely to Associate amongst our Own Sex, but would fain Bury us in their Houses or Beds, as in a Grave; the truth is, we Live like Bats or Owls, Labour like Beasts, and Die like Worms.

— Margaret Cavendish, To All Noble and Worthy Ladies

Also writing for an exclusively female audience and also angry at men was the eccentric Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (1623 – 1673), whom Virginia Woolf called a ‘giant cucumber,’ which ‘had spread itself over all the roses and carnations in the garden and choked them to death.’ She addressed some of her writings explicitly to ‘ladies.’ Her Poems and Fancies of 1653 begins:

Noble, Worthy Ladies, Condemn me not as a dishonour of your Sex, for setting forth this Work; for it is harmless and free from all dishonesty; I will not say from Vanity: for that is so natural to our Sex, as it were unnatural, not to be so. Besides, Poetry, which is built upon Fancy, Women may claim, as a work belonging most properly to themselves.

Cavendish asserts here that poetry is the natural realm of women’s imagination. In the introduction to her proto-science fiction novel The Blazing World, she also addresses a female audience and asserts her right to write whatever she pleases; if the present world is not to her taste she has the right to invent one that is and to be the mistress of it.

And if (Noble Ladies) you should chance to take pleasure in reading these Fancies, I shall account myself a Happy Creatoress: If not, I must be content to live a Melancholy Life in my own World . . . I am not Covetous, but as Ambitious as ever any of my Sex was, is, or can be; which is the cause, That though I cannot be Henry the Fifth, or Charles the Second; yet, I will endeavour to be, Margaret the First: and, though I have neither Power, Time nor Occasion, to be a great Conqueror, like Alexander, or Cesar; yet, rather than not be Mistress of a World, since Fortune and the Fates would give me none, I have made One of my own.

Cavendish transgressively published under her own name: not only fiction but scientific and philosophical works, including many short pieces on the natural sciences, and especially about the atom, written in verse ‘because I thought errors might better pass there than in prose – since poets write most fiction, and fiction is not given for truth, but pastime – and I fear my atoms will be as small pastime as themselves, for nothing can be less than an atom.’

Cavendish knew philosophers and scientists like Descartes and Thomas Hobbes and in 1667 she was the first woman to attend a meeting of the Royal Society, which did not admit women until 1945. Like several other early transgressive writers, Cavendish assumes that as a woman she will be subjected to harsher criticism than a male writer, not just by men but by women too. Her short apologia To All Noble and Worthy Ladies ends:

I imagine I shall be censured by my own sex, and men will cast a smile of scorn upon my book, because they think thereby women encroach too much upon men’s prerogatives. For they hold books as their crown and the sword as their sceptre by which they rule and govern. . . Therefore pray strengthen my side in defending my book, for I know women’s tongues are as sharp as two-edged swords, and wound as much when they are angered. And in this battle may your wit be quick and your speech ready, and your arguments so strong as to beat them out of the field of dispute. So shall I get honour and reputation by your favours, otherwise I may chance to be cast into the fire. But if I burn, I desire to die your martyr.

Unlike Joan of Arc and the thousands of European ‘witches,’ Cavendish was not literally burned at the stake and unlike the French writer Olympe de Gouges she was not sent to the guillotine; she stayed out of politics and though she was hardly the Angel of the House she mostly stayed out of trouble. But like several early women writers Cavendish was keen to stir women to action, to make the best of themselves and ignore men’s efforts to keep them down.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 5 Early English Women Writers to Discover appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 26, 2021

Can A Wrinkle in Time Ever be Successfully Filmed?

As the 60th anniversary of Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time (1962) approaches, with it will come a wave of nostalgia. A Wrinkle in Time follows the story of siblings, Meg and Charles Wallace, in their cosmic search to find the whereabouts of their missing father.

The story is cinematic in all ways possible; however, it has already had two unsuccessful attempts at being brought to the big screen. Why have both of these films flopped? Can A Wrinkle in Time ever be successfully filmed?

I vividly remember the first time I read this novel. I was in eighth grade, and I reveled in its whimsical details. A Wrinkle in Time is a complex novel that has resonated with generations of readers.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle (1962)

. . . . . . . . . .

The main theme — the idea that being unique should be celebrated — is universal. It can be applied to social media today, and the resulting “sameness” that comes from it. It’s a children’s book that deals with not-so-childish subjects; the loss of a parent and the turmoil that accompanies it, and the fear of inadequacy and how to overcome it.

A Wrinkle in Time is also an irresistible combination of fantasy and science fiction that can’t help but stand out. Meg and Charles Wallace find help from three angelic women who guide them in their quest to find their father and save the universe all in one sweep. It has underlying elements of magic that meld with scientific ideas, such as traveling through dimensions and spacetime.

It isn’t often that a children’s book can successfully combine a surrealist cosmic fantasy with tangible, approachable characters. Like many kids, I related to Meg, with her braces and just-so-average nature. Like Meg’s Charles Wallace, I too have a younger brother. It almost felt as if I was reading a story about my own life. For a young reader, the imagination you bring to a novel like A Wrinkle in Time makes it all the more mystical, all the more relatable. I knew when I was reading it that I had come across something significant.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Wrinkle in Time (2018 film) official trailer

. . . . . . . . . .

When I heard that A Wrinkle in Time was coming to the big screen in 2018, I begged my friends, a bunch of twenty-year-olds, to accompany me to the theater. I was so excited to see how a book I had adored when I was young would be brought to life. Unfortunately, I left the theater with the sense that I had been misled. The film came so close to encapsulating the things I loved about the novel, but fell short, leaving me feeling unsatisfied.

The film was targeted towards children, so maybe I shouldn’t have gotten my hopes up. Yet, it wasn’t underwhelming because it was for children, it was underwhelming because it failed to illustrate the book. With a critic rating of 42% on Rotten Tomatoes and an astonishingly low 26% audience score, it’s safe to say it was not well received. It was comforting to know I wasn’t the only person who was disappointed.

Critic Alex Hudson wrote, “A Wrinkle in Time feels like a missed opportunity.” Another critic, Jason Fraley, put it perfectly: “Some stories work far better in literature than on the screen, as the screenwriters scrap necessary connecting tissue to trim the runtime down to two hours.”

Casting decisionsThe film was directed by , the producer of Selma. She made a point to diversify the cast list, which I wholeheartedly celebrate. Meg was played by , who undoubtedly stole the show. She did an amazing job at portraying the character I loved so dearly. DuVernay’s decision to cast this iconic literary character as a black girl was refreshing, and her other casting choices made the film more relatable as a whole.

It was an interesting decision to make Charles Wallace’s character an adoptee in the film. It didn’t go along with the plot line of the book series, in which the entire family is directly related to their father, resulting in their “special powers.” It’s unclear what the intent was to add the adoption plot line, or whether it was really necessary.

The film was also visually pleasing. It was colorful and lush, exactly what I envisioned when reading it as a kid. In theory, the film should have been a hit. The all-star cast alone was worthy of much attention. Featuring Reese Witherspoon, Mindy Kaling, and Oprah Winfrey, acting as mentor figures for Meg and Charles Wallace, had the potential and talent to add a fun dynamic to the storyline. However, all the star power simply overshadowed the storyline.

In the film, many of the characters strayed away from their lovable traits. I found myself seriously disliking the characters that I had once loved. Ms. Whatsit, played by Witherspoon, was transformed into a snide character spouting sassy remarks, as opposed to the eccentric and all-knowing guardian that I loved in the book.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Plot holes and lack of character developmentIt was off-putting to see a timeless novel fizzling into an unrefined story line, updated with unnecessary modernity. I found the film version of Charles Wallace written in such a way that I couldn’t help but dislike him. His character is supposed to be a quiet prodigy, instead, he’s portrayed as a pompous, talkative kid. The personalities of the characters may have been altered to establish some 21st-century relatability in the movie version, but their likable qualities were erased in the process.

The actors seemed forced into roles they didn’t completely understand, and as a result, their performances fell short. The surrealist, astronomical flavor of the novel boiled down into a glitzy mess with glaring plot holes — and little to no character development.

So, why didn’t it work?

Translating A Wrinkle in Time to film wasn’t exactly a novel idea, so to speak. It had been attempted before, as a mini-series, in 2003. I’ve scoured the internet to find this series, curious to watch it, to no avail. The only option seems to be to buy the DVD, and most of us no longer have the disc drives to play this kind of media. So I was left to trust the author’s own words about the series; Madeleine L’Engle declared: “I have glimpsed it … I expected it to be bad, and it is.”

The book-to-film success rate is known to be low. So it isn’t entirely a surprise that the film didn’t stand up. Successful film franchises like Harry Potter or The Hunger Games are few and far between, which is what makes them special.

A Wrinkle in Time is an older novel. It doesn’t deal with a magical high school or dystopian societies that make for an epic, easily consumable cinematic experience. A Wrinkle in Time is convoluted. It’s whimsical and unique, with an essence I desperately wanted to see on film. But it seems doubtful that it can be captured on film. The 2018 mega-film had a $100 million budget and still managed to miss the mark. Why?

The answer may have to do with what makes the book so unique in the first place. It simply wasn’t built for film. Some novels can afford to cut plot corners when translated to film, but A Wrinkle in Time can’t. It’s a macrocosm, its own little universe that takes a well-tuned eye to successfully dissect.

Many successful adaptations rely on authors being on set, guiding the directors and cast to achieve a realistic vision that pleases the audience that loved the story first — the readers. That’s what made the film version of To Kill a Mockingbird, a book from the same era,so successful — Harper Lee was always on set as the 1962 film version of her 1960 novel was being produced. Neither the 2018 nor the 2003 mini-series did this.

L’Engle passed away in 2007, and wasn’t able to see the 2018 rendition of her novel. I wonder what she would have thought of it, and in my view, she would have absolutely done things differently.

The good news is the novel you grew up with and loved is still in print and readily available at bookstores and libraries. If you never read it as a child, it’s never too late to discover it as an adult. I recently reread the novel, and it captivated me just as much as it did the first time. Madeleine L’Engle’s celestial universe of mystique and wonder, and the lovable characters that explore it, still live on, in our imaginations and our hearts.

. . . . . . . . . .

If you’re still curious, the film is available to stream on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Can A Wrinkle in Time Ever be Successfully Filmed? appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Carson McCullers’ Mick Kelly: The Tomboy Author & Her Tomboy Heroine

This literary musing on Mick Kelly, the complex yet lovable tomboy character in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers, is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in mid-20th Century Women’s Fiction by Francis Booth. Reprinted by permission.

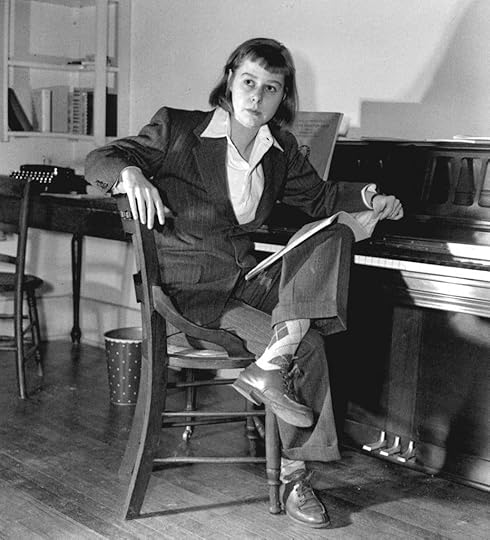

Carson McCullers (1917-1967) was born Lula Carson Smith but chose to use the gender-neutral Carson; she was the epitome of the literary tomboy: as tall as a man, with long, lanky limbs, short, bobbed hair, boyish dress, and elfin face – the ideal author to create fictional tomboys.

And that she did, in two of literature’s greatest tomboys, Mick Kelly (The Heart is a Lonely Hunter) and Frankie Addams (The Member of the Wedding), with their equally gender-neutral names.

McCullers had intended to be a musician rather than a writer, and at one time thought she might become a professional pianist. She was never academic and did not enjoy school; she was beaten up during her first week in high school and, as she says in her autobiography:

“I still wanted to be a concert pianist so my parents did not make me go every day. I just went enough to keep up with the classes. Now, years later, the high school teachers who taught me are extremely puzzled that anyone as negligent as I was could be a successful author. The truth is I don’t believe in school, whereas I believe very strongly in a thorough musical education. My parents agreed with me. I’m sure I missed certain social advantages by being such a loner but it never bothered me.”

Though her piano teacher encouraged her, McCullers “realized that Daddy would not be able to send me to Juilliard or any other great school of music to study.’ So she told him that she had ‘switched professions,’ and was going to be a writer. “That was something I could do at home, and I wrote every morning.”

. . . . . . . . .

See also:

Literary Tomboys in Classic Coming-of-Age Novels by Women Authors

. . . . . . . . .

In “Wunderkind,” McCullers’ first published story (1936) — she was only nineteen years old and a wunderkind herself — the teenage Frances is a precocious piano student, as McCullers herself was before she turned to writing; we will see shortly how for Mick Kelly in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, having a piano would be the most wonderful thing in the world.

In ‘Wunderkind’ Frances has a negative kind of coming of age when she is suddenly unable to face the piano. ‘She felt that the marrows of her bones were hollow and there was no blood left in her. Her heart that had been springing against her chest all afternoon felt suddenly dead. She saw it gray and limp and shriveled at the edges like an oyster.’

McCullers became even better known as a wunderkind when her first novel, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, was published in 1940. She took the literary world’s breath away at the age of twenty-two; in the publicity photo, she looks even younger, like an eager, doe-eyed, chipmunk-faced teenager, though she is holding a cigarette in a very adult manner, as she nearly always is in photos.

. . . . . . . . .

Carson McCullers

. . . . . . . . .

A gangling, towheaded youngster, a girl of about twelve, stood looking in the doorway. She was dressed in khaki shorts, a blue shirt, and tennis shoes – so that at first glance she was like a very young boy.

This is very much in line with descriptions of typical tomboys, as well as contemporary descriptions of McCullers herself. Mick – we are not told her birth name – is part of a large cast of strange characters, including two deaf-mutes, in a poor, isolated southern town that could easily be a setting for a Eudora Welty or Flannery O’Connor story but could also be Columbus, Georgia where McCullers was born.

One of the characters is Biff Brannon, the owner of the New York Cafe, with “two fists and a quick tongue,” who has “a special friendly feeling for sick people and cripples,” including Mick – especially Mick. She is certainly an outsider even though she is not sick or crippled.

“He thought of the way Mick narrowed her eyes and pushed back the bangs of her hair with the palm of her hand. He thought of her hoarse, boyish voice and her habit of hitching up her khaki shorts and swaggering like a cowboy in the picture show. A feeling of tenderness came in him. He was uneasy.”

Although Mick is described as being like a young boy, she’s rather tall for her age, as was McCullers herself, and completely fearless, as McCullers wasn’t. “Five feet six inches tall and a hundred and three pounds, and she was only thirteen. Every kid at the party was a runt beside her.” Despite her tomboyishness and rough clothes, she has the pretensions and dreams of any teenager – any teenage boy, anyway.

McCullers’ sympathetic portrayal of African-Americans

Another character who is fond of Mick is Portia, the daughter of the town’s Black doctor, a wise and almost saintly figure. McCullers’ sympathetic portrayal of African-Americans and the way her Southern characters show no prejudice was quite shocking for 1940, though probably helped with her critical reception by the East Coast literary elite.

Portia’s Shakespearean name and the fact that her father is a doctor imply her parents had an education way beyond what would be expected of Southern Black families of the time, though she does talk in a kind of dialect. Portia works as a maid in the Kelly household but complains to her father that she is not being paid properly.

. . . . . . . . .

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter

. . . . . . . . .

But the biggest thing in Mick’s life in music, especially classical music; she walks around the streets of the town in the evenings listening to the radios in the houses playing different stations. “There was one special fellow’s music that made her heart shrink up every time she heard it. Sometimes this fellow’s music was like little colored pieces of crystal candy, and other times it was the softest, saddest thing she had ever imagined about.”

The composer turns out to be Mozart, though she cannot at first spell his name and has no idea who he is. She also listens to music by someone who turns out to be Beethoven; it makes her face her own littleness – big as she is she does not contain multitudes. “Wonderful music like this was the worst hurt there could be. The whole world was this symphony, and there was not enough of her to listen.”

The thing Mick wants most in the world is a piano: “If we had a piano I’d practice every single night and learn every piece in the world.” She also wants to write music, and notes down snatches of songs, “but she didn’t feel satisfied with them. If you could write a symphony!” In the private box that, like most teenage girls, she has under her bed, Mick has a notebook; she draws five lines across a test page.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Mick is in the middle of her family: her eldest sibling is Bill and she also has younger brothers, including Bubber. Mick also has two older sisters, Hazel and Etta, with whom she shares a room and who are “O.K. as far as sisters went.” The older girls complain about Mick’s “silly boys clothes,” but it is exactly because she has older sisters that she wears them.

“I wear shorts because I don’t want to wear your old hand-me-downs. I don’t want to be like either of you and I don’t want to look like either of you. And I won’t. That’s why I wear shorts. I’d rather be a boy any day, and I wish I could move in with Bill.”

An unexpected coming of ageMick’s coming of age, such as it is, begins with a party she decides to hold at her house and the clothes she decides to wear for it.

“She stood in front of the mirror a long time, and finally decided she either looked like a sap or else she looked very beautiful. One way or the other… she stuck the rhinestones in her hair and put on plenty of lipstick and paint. When she finished she lifted up her chin and half-closed her eyes like a movie star. Slowly she turned her face from one side to the other. It was beautiful she looked – just beautiful. She didn’t feel like herself at all. She was somebody different from Mick Kelly entirely.”

The party gets out of hand and many people come uninvited, though nothing especially bad happens to her or anyone else. It ends with her and the others running around playing in ditches outdoors like children. But Mick is no longer a child by the time she gets home. “Her old shorts and shirt were lying on the floor just where she had left them. She put them on. She was too big to wear shorts any more after this. No more after this night. Not any more.”

Contemplating Mick maturing, McCullers uses the character of Biff to rehearse a rather bizarre but obviously highly personal and deeply heartfelt meditation on intersexuality.

Mick had grown so much in the past year that she would be taller than he was. She dressed in the red sweater and blue pleated skirt she had worn every day since school started. Now the pleats had come out and the hem dragged loose around her sharp, jutting knees. She was at the age when she looked as much like an overgrown boy as a girl.

Mick never seems to have any feelings for other girls, and there aren’t any in the novel. But she does get quite close to the boy Harry, who is very passionate about fascism and world events. They take a trip out to the lake to have a picnic one day; taking off their bathing suits, “they turned towards each other. Maybe it was half an hour they stood there – maybe not more than a minute,” before Harry says they ought to get dressed.

But then it happens, or at least it seems to: McCullers draws an impressionistic veil over it but shows how Mick’s coming of age is advanced by it.

An uneasy segue to young womanhood

Mick’s coming of age does not turn out the way she hoped: she goes directly from tomboy schoolgirl to overworked, overtired, and defeated mature woman when, to help the family’s disastrous finances, Mick leaves school to work in a shop, her dreams and ambitions unrealized.

While she was still at school, when she came home “she felt good and was ready to start working on the music. But now she was always too tired.”

Then things get even worse: John Singer dies; he is the deaf mute at the center of Lonely Hunter. Singer has been a lodger at the Kelly house and been very sympathetic to Mick, who had become quite obsessed with him (though not in a sexual way). “There were these two things she could never believe. That Mister Singer had killed himself and was dead. And that she was grown and had to work at Woolworth’s.”

“She was the one who found him. They had thought the noise was a backfire from a car, and it was not until the next day that they knew. She went in to play the radio. The blood was all over his neck and when her dad came he pushed her out the room. She had run from the house. The shock wouldn’t let her be still. She had run into the dark and hit herself with her fists. And then the next night he was in a coffin in the living room.”

All this changes Mick irrevocably. Biff notices the changes more perhaps than Mick herself. Mick has never had any idea of Biff’s feelings for her, which in any case have evaporated with her coming of age. Biff preferred Mick as a tomboy to Mick as a grown woman. By the end, Mick grows philosophical about her new womanhood.

More literary tomboys to explore in Girls in Bloom Charlie Laborde (“Charlie” by Kate Chopin, 1900)Peggy Vaughan (A Terrible Tomboy by Angela Brazil, 1904)Irene Ashleigh (A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls by LT Meade, 1913) Petrova Fossil (Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfeild, 1932)George Fayne (The Secret of Red Gate Farm by ‘Caroline Keene’, 1931)George Kirrin (Five On a Treasure Island by Enid Blyton, 1942)Frankie Addams (The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers, 1946)

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Carson McCullers’ Mick Kelly: The Tomboy Author & Her Tomboy Heroine appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 18, 2021

Petrova Fossil & Tania Whichart: Noel Streatfeild’s Literary Tomboys

This intriguing look at Petrova Fossil, one of the three Fossil sisters of Noel Streatfeild’s best-known work of children’s literature, Ballet Shoes (1932), is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in mid-20th Century Women’s Fiction by Francis Booth, reprinted with permission

Noel Streatfeild (1895 – 1986; note that she was a female author with a male-sounding first name and an unconventionally-spelled surname), was born in Sussex, England and was the daughter of the Bishop of Lewes.

She wrote several children’s books, of which Ballet Shoes – beautifully illustrated by her older sister – was the first and most well-known and well-loved by more than one generation of girls; her subsequent books were renamed by the publishers to have the word Shoes in the title, though in fact they are not a series.

Petrova Fossil of Ballet Shoes (1932)

Like Jo March, Petrova in Ballet Shoes by is one of a group of sisters but very unlike the others. She is a different kind of tomboy to outdoorsy, sporty girls like Kate Chopin’s Charlie Laborde: she does not charge around on a horse or play boys’ games but loves staying in the house and tinkering with mechanical things, unlike her more conventionally feminine, artistic sisters Posy and Pauline.

Petrova is said to be ‘very stupid with her needle, but very neat with her fingers; she was working at a model made in Meccano. It was a difficult model of an aeroplane, meant for much older children to make.’

Like a conventional boy, Petrova ‘knows heaps about aeroplanes and motor-cars,’ and, like Carson McCullers’ Frankie Addams (of The Member of the Wedding), wants to be a pilot when she grows up.

When it is suggested that the sisters, who want to be famous for something artistic, learn ballet, Petrova does not seem to be ballet material.

‘Well, she won’t be good at it to my way of thinking, but it might be just the thing for her – turn her more like a little lady; always messing about with the works of clocks and that just like a boy; never plays with dolls, and takes no more interest in her clothes than a scarecrow.’

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Predictably, Petrova is bored by the dancing but finds something interesting to do at the weekends.

Petrova had a thin, pale face and high cheekbones, very different to Pauline’s pink-and-white oval and Posy’s round, dimpled look; she was naturally more serious than the others, and so, being bored for eight hours in each week did not show on her, as it would on them. It was Sundays that saved her.

After morning church she went straight to the garage, put on her jeans, and though only emergency work was really done on Sundays, the foreman always had something ready for her. Very dirty and happy, she would work until they had to dash home for lunch. Afterwards, occasionally, they came back until tea-time; then they washed and popped across the road to Lyons, but usually they went on expeditions in the car.

Those expeditions were their secret; Petrova never even told the other two about them. The best of them were to the civil flying-grounds, where they watched the planes take off and alight, and often went up themselves. Sometimes they saw some motor-car or dirt-track races; but Petrova like the flying Sundays best.

Although, of course, she was years too young to fly, in bed, and at her very few odd moments, she studied for a ground license; she knew that when she did, an aeroplane would obey her, just as certainly as Posy knew that her feet and body would obey her.

. . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Before she wrote the universally-loved and continuously in-print Ballet Shoes for children, Streatfeild wrote her first published novel The Whicharts, 1931 for adults, universally ignored and out of print for decades. It has an almost identical plot and characters to the later book; in a way it is Ballet Shoes’ evil twin.

Streatfeild wrote several sequels to Ballet Shoes, the semi-autobiographical A Vicarage Family, 1963 and returned to the subject of orphan girls dancing professionally much later with Wintle’s Wonders, 1957.

In The Whicharts the three sisters have different mothers but the same father: the Brigadier. They are not exactly orphans but they are all brought up by another of the Brigadier’s lovers who worships him, as do the children, though they never know him and he dies when they are very young. They give themselves the surname Whichart after him, ‘our Father which art in heaven.’

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

The tomboy in this novel is again the middle sister, here called Tania. Like Petrova Fossil she loves mechanical devices, especially when they are in bits and need mending.

Tania loved machinery, too. To screw things together, to find out why some thing wouldn’t go, was an absorbing game. All the week she was too busy to play at anything, so on Sunday mornings he always had something waiting for her. A clock that wouldn’t go. A toy engine in need of repairs. A sewing-machine that had stuck.

Also like Petrova, Tania hates the dancing she is forced into but loves cars and planes and dreams of working in a garage.

“Pity you aren’t a boy, you could have got a job in this line.”

“If I was a boy I’d learn to fly.”

“Why?”

“They goes so fast.”

Tania later pays the owner of the garage to let her work there. ‘The garage life seemed to Tania as near the life of Heaven as was possible while still on earth.’ She even finds a chauffeur who teaches her to drive even though she is only sixteen. Older sister Maimie is not interested in cars, except when they are driven by boys.

‘Maimie bitterly resented interference, she wanted a good time. And a good time was going out with boys. She adored boys . . . Some of the ones she knew had cars; they all had enough money to take her to the pictures.’

Maimie’s coming of age moment happens with an older theatre producer, bizarrely named Dolly, when she is seventeen.

Dolly sat down beside Maimie. He ran his fingers through her hair. ‘You’ve got pretty hair, Baby.’ Maimie only smiled. ‘And a pretty face, and a very pretty little figure’; his hand wandered over her. Her experience with the boys who had taken her motoring and to the pictures had left her quite unprepared for Dolly. She thought: ‘Surely it must have been an accident, he couldn’t have meant to touch me quite like that. Not there!’

But that is exactly where and how Dolly meant to touch Maimie. Shortly afterwards she loses her virginity to him, though Streatfeild seamlessly elides the act itself from the text:

She heard a clock strike. Dolly from behind slipped his hands under her armpits. She shivered. He pulled her round to face him. ‘Little innocent Baby.’ Maimie moved away with a jerk. ‘I think I’d better go home,’ she laughed nervously. ‘It does seem silly, but do you know, I feel frightened, Dolly.’ He pulled her down beside him on the divan. His hands slowly stroked her. Soothed her. She felt almost sleepy. He put his lips to hers. She turned her body towards him. When she put on her hat she couldn’t look at him. She was amazed when she got into the street to find that she didn’t look different. Nobody stared. Nobody seemed to guess.

As they get older the three girls go looking for their mothers. Tania drives herself across the country to meet hers. It turns out to have been worth it; her rich new mother wants to take her traveling to Java.

“I want to take you about, and show you the world, and perhaps later on find you a husband.”

“I’d rather have an aeroplane,” exclaimed Tania, horrified out of her usual reticence.

“Would you? Do you want to fly? Well, could you bear to try traveling for a year first, and after that you can do what you like. I think you’ll find Java fun, you know. The people are too attractive, and they have –”

But Tania wasn’t listening. Her mind was on the skyline, where an aeroplane, like some giant silver bird, was darting towards them.

. . . . . . . . . . .

See also:

Literary Tomboys in Classic Coming-of-Age Novels by Women Authors

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Petrova Fossil & Tania Whichart: Noel Streatfeild’s Literary Tomboys appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 17, 2021

The Storm by Kate Chopin (1898) – full text

“The Storm” by Kate Chopin is a short story written in 1898, just a year before what is now her best-known work, The Awakening (a novella). Had it been published it would surely have been just as controversial, since it also explores extramarital passion as its theme.

At the time these works were written, women — especially married mothers — were supposed to be “the angels in the house.” Any hint of agency over one’s sexual desires in a work of fiction, particularly from a woman’s pen, was considered shocking. The Awakening, now considered a proto-feminist work and a staple in literature courses, was reviled by critics and banned in many quarters long after its publication.

Even before the brutal reception of The Awakening, Kate Chopin seemed to have sensed not to send “The Storm” out for consideration. It was never published in her lifetime, and indeed, not for many decades afterwards. Dated July 19, 1898, it wasn’t published until 1969, in The Complete Works of Kate Chopin. Chopin biographer Per Seyersted wrote:

“Sex in this story is a force as strong, inevitable, and natural as the Louisiana storm which ignites it.” The story “covers only one day and one storm and does not exclude the possibility of later misery. The emphasis is on the momentary joy of the amoral cosmic force.”

[Chopin] “was not interested in the immoral in itself, but in life as it comes, in what she saw as natural — or certainly inevitable— expressions of universal Eros, inside or outside of marriage. She focuses here on sexuality as such, and to her, it is neither frantic nor base, but as ‘healthy’ and beautiful as life itself.”

“The Storm” was actually a sequel to another Chopin short story, “At the ‘Cadian Ball” (1892), which featured some of the same characters.

More about “The Storm” by Kate Chopin

Complete history, resources at KateChopin.org Plot summary and analysis on Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads Themes and setting in “The Storm” Listen to this short story on Librivox“The Storm” by Kate Chopin

I

The leaves were so still that even Bibi thought it was going to rain. Bobinot, who was accustomed to converse on terms of perfect equality with his little son, called the child’s attention to certain sombre clouds that were rolling with sinister intention from the west, accompanied by a sullen, threatening roar. They were at Friedheimer’s store and decided to remain there till the storm had passed. They sat within the door on two empty kegs. Bibi was four years old and looked very wise.

“Mama’ll be ‘fraid, yes, he suggested with blinking eyes.

“She’ll shut the house. Maybe she got Sylvie helpin’ her this evenin’,” Bobinot responded reassuringly.

“No; she ent got Sylvie. Sylvie was helpin’ her yistiday,’ piped Bibi.

Bobinot arose and going across to the counter purchased a can of shrimps, of which Calixta was very fond. Then he returned to his perch on the keg and sat stolidly holding the can of shrimps while the storm burst. It shook the wooden store and seemed to be ripping great furrows in the distant field. Bibi laid his little hand on his father’s knee and was not afraid.

II

Calixta, at home, felt no uneasiness for their safety. She sat at a side window sewing furiously on a sewing machine. She was greatly occupied and did not notice the approaching storm. But she felt very warm and often stopped to mop her face on which the perspiration gathered in beads. She unfastened her white sacque at the throat. It began to grow dark, and suddenly realizing the situation she got up hurriedly and went about closing windows and doors.

Out on the small front gallery she had hung Bobinot’s Sunday clothes to dry and she hastened out to gather them before the rain fell. As she stepped outside, Alce Laballire rode in at the gate. She had not seen him very often since her marriage, and never alone. She stood there with Bobinot’s coat in her hands, and the big rain drops began to fall. Alce rode his horse under the shelter of a side projection where the chickens had huddled and there were plows and a harrow piled up in the corner.

“May I come and wait on your gallery till the storm is over, Calixta?” he asked.

“Come ‘long in, M’sieur Alce.”

His voice and her own startled her as if from a trance, and she seized Bobinot’s vest. Alce, mounting to the porch, grabbed the trousers and snatched Bibi’s braided jacket that was about to be carried away by a sudden gust of wind. He expressed an intention to remain outside, but it was soon apparent that he might as well have been out in the open: the water beat in upon the boards in driving sheets, and he went inside, closing the door after him. It was even necessary to put something beneath the door to keep the water out.

“My! what a rain! It’s good two years sence it rain’ like that,” exclaimed Calixta as she rolled up a piece of bagging and Alce helped her to thrust it beneath the crack.

She was a little fuller of figure than five years before when she married; but she had lost nothing of her vivacity. Her blue eyes still retained their melting quality; and her yellow hair, dishevelled by the wind and rain, kinked more stubbornly than ever about her ears and temples.

The rain beat upon the low, shingled roof with a force and clatter that threatened to break an entrance and deluge them there. They were in the dining room the sitting room the general utility room. Adjoining was her bed room, with Bibi’s couch along side her own. The door stood open, and the room with its white, monumental bed, its closed shutters, looked dim and mysterious.

Alce flung himself into a rocker and Calixta nervously began to gather up from the floor the lengths of a cotton sheet which she had been sewing.

“If this keeps up, Dieu sait if the levees goin’ to stan it!” she exclaimed.

“What have you got to do with the levees?”

“I got enough to do! An’ there’s Bobinot with Bibi out in that storm if he only didn’ left Friedheimer’s!”

“Let us hope, Calixta, that Bobinot’s got sense enough to come in out of a cyclone.”

She went and stood at the window with a greatly disturbed look on her face. She wiped the frame that was clouded with moisture. It was stiflingly hot. Alce got up and joined her at the window, looking over her shoulder. The rain was coming down in sheets obscuring the view of far-off cabins and enveloping the distant wood in a gray mist. The playing of the lightning was incessant. A bolt struck a tall chinaberry tree at the edge of the field. It filled all visible space with a blinding glare and the crash seemed to invade the very boards they stood upon.

Calixta put her hands to her eyes, and with a cry, staggered backward. Alce’s arm encircled her, and for an instant he drew her close and spasmodically to him.

“Bont!” she cried, releasing herself from his encircling arm and retreating from the window, the house’ll go next! If I only knew w’ere Bibi was!” She would not compose herself; she would not be seated. Alce clasped her shoulders and looked into her face. The contact of her warm, palpitating body when he had unthinkingly drawn her into his arms, had aroused all the old-time infatuation and desire for her flesh.

“Calixta,” he said, “don’t be frightened. Nothing can happen. The house is too low to be struck, with so many tall trees standing about. There! aren’t you going to be quiet? say, aren’t you?”

He pushed her hair back from her face that was warm and steaming. Her lips were as red and moist as pomegranate seed. Her white neck and a glimpse of her full, firm bosom disturbed him powerfully.

As she glanced up at him the fear in her liquid blue eyes had given place to a drowsy gleam that unconsciously betrayed a sensuous desire. He looked down into her eyes and there was nothing for him to do but to gather her lips in a kiss. It reminded him of Assumption.

“Do you remember in Assumption, Calixta?” he asked in a low voice broken by passion.

Oh! she remembered; for in Assumption he had kissed her and kissed and kissed her; until his senses would well nigh fail, and to save her he would resort to a desperate flight. If she was not an immaculate dove in those days, she was still inviolate; a passionate creature whose very defenselessness had made her defense, against which his honor forbade him to prevail. Now well, now her lips seemed in a manner free to be tasted, as well as her round, white throat and her whiter breasts.

They did not heed the crashing torrents, and the roar of the elements made her laugh as she lay in his arms. She was a revelation in that dim, mysterious chamber; as white as the couch she lay upon. Her firm, elastic flesh that was knowing for the first time its birthright, was like a creamy lily that the sun invites to contribute its breath and perfume to the undying life of the world.

The generous abundance of her passion, without guile or trickery, was like a white flame which penetrated and found response in depths of his own sensuous nature that had never yet been reached.

When he touched her breasts they gave themselves up in quivering ecstasy, inviting his lips. Her mouth was a fountain of delight. And when he possessed her, they seemed to swoon together at the very borderland of life’s mystery.

He stayed cushioned upon her, breathless, dazed, enervated, with his heart beating like a hammer upon her. With one hand she clasped his head, her lips lightly touching his forehead. The other hand stroked with a soothing rhythm his muscular shoulders.

The growl of the thunder was distant and passing away. The rain beat softly upon the shingles, inviting them to drowsiness and sleep. But they dared not yield.

The rain was over; and the sun was turning the glistening green world into a palace of gems. Calixta, on the gallery, watched Alce ride away. He turned and smiled at her with a beaming face; and she lifted her pretty chin in the air and laughed aloud.

III

Bobinot and Bibi, trudging home, stopped without at the cistern to make themselves presentable.

“My! Bibi, w’at will yo’ mama say! You ought to be ashame’. You oughta’ put on those good pants. Look at ’em! An’ that mud on yo’ collar! How you got that mud on yo’ collar, Bibi? I never saw such a boy!” Bibi was the picture of pathetic resignation.

Bobinot was the embodiment of serious solicitude as he strove to remove from his own person and his son’s the signs of their tramp over heavy roads and through wet fields. He scraped the mud off Bibi’s bare legs and feet with a stick and carefully removed all traces from his heavy brogans. Then, prepared for the worst the meeting with an over-scrupulous housewife, they entered cautiously at the back door.

Calixta was preparing supper. She had set the table and was dripping coffee at the hearth. She sprang up as they came in.

“Oh, Bobinot! You back! My! But I was uneasy. W’ere you been during the rain? An’ Bibi? he ain’t wet? he ain’t hurt?” She had clasped Bibi and was kissing him effusively. Bobinot’s explanations and apologies which he had been composing all along the way, died on his lips as Calixta felt him to see if he were dry, and seemed to express nothing but satisfaction at their safe return.

“I brought you some shrimps, Calixta,” offered Bobinot, hauling the can from his ample side pocket and laying it on the table.

“Shrimps! Oh, Bobinot! you too good fo’ anything!” and she gave him a smacking kiss on the cheek that resounded, “J’vous reponds, we’ll have a feas’ to-night! umph-umph!”

Bobinot and Bibi began to relax and enjoy themselves, and when the three seated themselves at table they laughed much and so loud that anyone might have heard them as far away as Laballiere’s.

IV

Alce Laballiere wrote to his wife, Clarisse, that night. It was a loving letter, full of tender solicitude. He told her not to hurry back, but if she and the babies liked it at Biloxi, to stay a month longer. He was getting on nicely; and though he missed them, he was willing to bear the separation a while longer realizing that their health and pleasure were the first things to be considered.

V

As for Clarisse, she was charmed upon receiving her husband’s letter. She and the babies were doing well. The society was agreeable; many of her old friends and acquaintances were at the bay. And the first free breath since her marriage seemed to restore the pleasant liberty of her maiden days. Devoted as she was to her husband, their intimate conjugal life was something which she was more than willing to forego for a while.

So the storm passed and everyone was happy.

More full texts of Chopin’s works Désirée’s Baby (1893) The Story of an Hour (1894) A Matter of Prejudice (1897) The Awakening (1899)

The post The Storm by Kate Chopin (1898) – full text appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Charlie Laborde, Tomboy-Poet of Kate Chopin’s “Charlie”(1900)

One of Kate Chopin’s most interesting heroines is the tomboyish teen Charlie Laborde of the eponymous short story “Charlie” (1900). This fascinating musing on this little-known character is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in mid-20th Century Women’s Fiction by Francis Booth, reprinted with permission:

Girls in coming of age novels often keep diaries: it is a very good device for an author to let us in on the girl’s feelings, and in this case for the author to enjoy herself playing with ideas of fiction, style and truth.