Nava Atlas's Blog, page 42

April 26, 2021

Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke

The extraordinary Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke (1561 – 1621), was an almost exact contemporary of Shakespeare and has been one of the candidates in various conspiracy theories for the actual author of Shakespeare’s works, in particular his sonnets.

Even though this is nonsense, Mary Sidney, sister of the more famous Philip, was arguably Shakespeare’s – and almost everyone else’s – equal as a poet.

This introduction to Mary Sidney’s life and work is excerpted from Killing the Angel: Early Transgressive British Woman Writers by Francis Booth ©2021, reprinted by permission.

In her time, Mary was probably known more as a host and patron to other writers than as a writer herself. Mary had grown up attached to the court of Elizabeth I where her mother Lady Mary Dudley – the sister of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, Elizabeth’s most favored courtier and perhaps the Queen’s lover – was a gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber.

In these surroundings Mary received a liberal education, including scripture, the classics, rhetoric, French, Italian, and Latin, in which she was fluent, and possibly some Greek and Hebrew. Mary was also proficient at the ‘female’ accomplishments of singing and playing the lute as well as needlework, so much so that so that her name was used in endorsing needlework patterns and for books of music.

In 1577, Mary married Henry Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, a family friend and wealthy landowner; among his properties were Wilton House near Salisbury, and Baynard’s Castle in London, where the couple entertained Queen Elizabeth to dinner. Henry died in 1601, leaving Mary less well-off than she had expected, and with the provision in his will that she should not remarry.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Psalms of DavidHer largest work is her complete translation of the Psalms of David, a form known as a psalter. She and her brother worked on the translations together at first but he died in battle overseas in 1586 when they had only reached Psalm 43 of 150; she finished them by herself, also going back and revising all the earlier ones, so that the whole work may be considered to be hers.

Mary was at the time overshadowed by her famous brother Philip Sidney, who was a courtier, a warrior and considered then to be the ideal gentleman. He was indeed a major literary figure: his sonnet cycle Astrophel and Stella rivals Shakespeare’s sonnets and his critical work The Defence of Poesie introduced the ideas of continental theorists to England.

But The Sidney Psalter, largely the work of Mary, and certainly all overseen by her, is a masterclass of poetic styles and techniques: every conceivable poetic form and structure is included and all brilliantly executed; it is a great tour de force of poetry, one of the greatest extended works of verse of its own age, and indeed of any age.

When the volume of Psalms was published, Mary assumed authorship in her own name, Mary Sidney Herbert, but dedicated it to ‘the Angel Spirit of the Most Excellent Sir Philip Sidney.’ It was highly appreciated at the time; John Donne was a fan and wrote a congratulatory poem.

So though some have, some may some Psalms translate,

We thy Sydnean Psalms shall celebrate …

The Psalms as a collection are known in the Church of England as the Book of Common Prayer, and regular churchgoers will be quite shocked by the Sidney translations of them. In their normal Church of England version, the Psalms as used in church services are almost unchanged since Miles Coverdale’s 1535 translations, which were largely preserved in the King James Bible of 1611. The Sidney versions are not translations so much as poetic reimaginings. The well-known Psalm 110, Dixit Dominus is a good example: the version known to Church of England attendees ever since services were conducted in English goes:

The Lord said unto my Lord, Sit thou at my right hand, until I make thine enemies thy footstool.

The Lord shall send the rod of thy strength out of Zion: rule thou in the midst of thine enemies.

Thy people shall be willing in the day of thy power, in the beauties of holiness from the womb of the morning: thou hast the dew of thy youth.

The Lord hath sworn, and will not repent, Thou art a priest for ever after the order of Melchizedek.

The Lord at thy right hand shall strike through kings in the day of his wrath.

He shall judge among the heathen, he shall fill the places with the dead bodies; he shall wound the heads over many countries.

He shall drink of the brook in the way: therefore shall he lift up the head.

And here is Mary Sidney’s radically different version:

Thus to my lord, the Lord did say:

Take up thy seat at my right hand,

Till all thy foes that proudly stand,

I prostrate at thy footstool lay.

From me thy staff of might

Sent out of Sion goes:

As victor then prevail in fight,

And rule repining foes.

But as for them that willing yield,

In solemn robes they glad shall go:

Attending thee when thou shalt show

Triumphantly thy troops in field:

In field as thickly set

With warlike youthful train

As pearlèd plain with drops is wet,

Of sweet Aurora’s rain.

The Lord did swear, and never he

What once he swear will disavow:

As was Melchisedech so thou,

An everlasting priest shalt be.

At hand still ready priest

To guard thee from annoy,

Shall sit the Lord that loves thee best,

And kings in wrath destroy.

Thy Realm shall many Realm contain:

Thy slaughtered foes thick heaped lie:

With crushed head even he shall die,

Who head of many Realm doth reign.

If passing on these ways

Thou taste of troubled streams:

Shall that eclipse thy shining rays?

Nay light thy glories beams.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Killing the Angel on Amazon US*

Killing the Angel on Amazon UK*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Despite living her earlier life in her brother’s shadow, Mary was recognized quite early on as an extraordinary talent and respected by her contemporaries both male and female; in addition to the recognition given to the publication of the Psalms, Mary was the only woman included in John Bodenham’s poetry collection Belvidere, 1600. Æmalia Lanyer’s encomium, from Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, was dedicated to her:

This nymph, quoth he, great Pembroke hight by name,

Sister to valiant Sidney, whose clear light Gives light

to all that tread true paths of Fame,

Who in the globe of heaven doth shine so bright

For to this Lady now I will repair,

Presenting her the fruits of idle hours;

Though many Books she writes that are more rare,

Yet there is honey in the meanest flowers …

Mary was also praised at great length by John Davies in the dedication to The Muses Sacrifice, 1612.

PEMBROKE, (a Paragon of Princely PARTS,

and, of that Part that most commends the Muse,

Great Mistress of her Greatness, and the ARTS,)

Phoebus and Fate makes great, and glorious!

A Work of Art and Grace (from Head and Heart

that makes a Work of Wonder) thou hast done;

Where Art, seems Nature; Nature, seemeth Art;

and, Grace, in both, makes all out-shine the Sun.

Davies understands that even so prominent, so talented a woman as Mary Sidney cannot seek public fame, as male writers can.

And didst thou thirst for Fame. (as all Men do)

thou would’st, by all means, let it come to light;

But though thou cloud it, as doth Envy too,

yet through both Clouds it shines, it is so bright!

. . . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

5 Early English Women Writers to Discover

Elizabeth Cary, Early English Poet, Dramatist, and Scholar

The Matchless Orinda: Katherine Philips

The Scandalous, Sexually Explicit Writings of Aphra Behn

Olympe de Gouges: An Introduction

Susanna Centlivre, English Poet and Playwright

. . . . . . . . . . .

Mary Sidney was not just a poet but a translator; her translation from the French of The Tragedy of Antony, Done into English by the Countess of Pembroke, 1592 revived the use of soliloquy from classical works and is a source of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, 1607. Mary also translated Petrarch’s Triumph of Death and is the probable author of the long poem The Doleful Lay of Clorinda, 1595, a lament for her dead brother.

Woods, hills and rivers, now are desolate,

Sith he is gone the which them all did grace:

And all the fields do wail their widow state,

Sith death their fairest flower did late deface.

The fairest flower in field that ever grew,

Was Astrophel: that was, we all may rue.

What cruel hand of cursed foe unknown,

Hath cropped the stalk which bore so faire a flower?

Untimely cropped, before it well were grown,

And clean defaced in untimely hour.

Great loss to all that ever him did see,

Great loss to all, but greatest loss to me.

Mary Sidney’s legacy as patroness and poet

Under Mary’s vigorously transgressive stewardship, Wilton House became a literary salon for writers known as the Wilton Circle, which included Edmund Spenser, Samuel Daniel, Michael Drayton and Ben Jonson. John Aubrey said that ‘Wilton House was like a college, there were so many learned and ingenious persons. She was the greatest patroness of wit and learning of any lady in her time.’

Other poets agreed: Samuel Daniel said of his poetry that he had received ‘the first notion for the formal ordering of those compositions at Wilton, which I must ever acknowledge to have been my best School,’ andThomas Churchyard said that ‘she sets to school, our Poets everywhere.’ At Wilton house, after Queen Elizabeth’s death in 1603, Mary hosted the new King James I and Queen Anne; it is probable that Shakespeare’s As You Like It was first performed for a royal audience there.

Writers vied for her approval and patronage; she probably received more dedications at the front of published books than any non-royal woman, including from Thomas Nashe, Abraham Fraunce, who incorporated her name into the titles of several works that he presented to her, includingThe Countesse of Pembrokes Emmanuel (1591) and the three parts ofThe Countesse of Pembrokes Ivychurch (1591–2) and Nicholas Breton’s The Countesse of Pembrokes Love and‘The Countess of Pembroke’s Passion.

On her death in 1621, Mary Sidney was given a large funeral at St Paul’s Cathedral – possibly the only female writer ever to have been so honored – and her body was taken by torchlight to be buried at Salisbury Cathedral next to her husband. Her epitaph is probably by Ben Jonson:

Underneath this marble hearse

Lies the subject of all verse;

Sidney’s sister, Pembroke’s mother.

Death! ere thou hast slain another

Wise and fair and good as she,

Time shall throw a dart at thee.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 23, 2021

Allison MacKenzie: Coming of Age in Peyton Place by Grace Metalious

This look at the coming of age of Allison MacKenzie, one of the central characters of Peyton Place, the controversial 1956 novel by Grace Metalious, is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

Peyton Place is set in a small New England town where everyone knows everyone’s business. The inhabitants of Peyton Place seemed to have a lot more sex than other novels of the mid-fifties – more than the censors and many critics were prepared to put up with: the novel was banned in Knoxville, Tennessee in 1957 and in Rhode Island in 1959.

But the censors were far too late. Peyton Place was already a bestseller by September 1956, and would remain so well into 1957. It sold over 100,000 copies in its first month, compared to the average first novel which sold 3,000 copies, if lucky, in its lifetime. Peyton Place eventually sold over 12 million copies but even then is most widely remembered for its film and TV adaptations.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Grace Metalious

. . . . . . . . . .

Grace Metalious (1924-1964), born Marie Grace DeRepentigny, was born into poverty in New England. She married George Metalious and, unlike most other successful female authors who kept their names, published under her husband’s.

Despite their poverty, George attended university and became principal of a school while Grace continued to write, something she had done since she was a student, and in which George encouraged her. George later said that the novel’s eponymous town and its name were “a composite of all small towns where ugliness rears its head, and where the people try to hide all the skeletons in their closets.”

Grace was thirty when she finished the manuscript; she found a literary agent but had trouble finding a publisher because of the amount of sex it contained. Reviews in serious newspapers condemned the book but that did not stop people buying it. Much later Metalious said, “If I’m a lousy writer, then an awful lot of people have lousy taste.”

She was right. Less than a month after the novel was published, producer and screenwriter Jerry Wald paid her $250,000 for the film rights. He also paid her as a story consultant though she was not in the end responsible for any of the screenplay and in fact she hated Hollywood, hated the way her novel was sanitized and was appalled by the suggestion that Pat Boone – who wrote a bland advice column for teenagers in Ladies Home Journal – be cast in a leading role.

Still, the $400,000 she made from the film was probably some consolation. The film came out in 1957, featuring nineteen-year-old newcomer Diane Varsi who was far too beautiful and mature for the role but was nominated for an Academy Award anyway.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

The TV series of Peyton Place began in 1964, running for five seasons until 1969. Like the film, it was a very toned down version of the novel, starring , age nineteen when the series began, as twelve-year-old Allison Mackenzie. Unlike Varsi and Farrow, Allison is plain, chubby, and has very few friends.

Allison hadn’t one friend in the entire school, except for Selena Cross. They made a peculiar pair, those two, Selena with her dark, gypsyish beauty, her thirteen-year-old eyes as old as time, and Allison Mackenzie, still plump with residual babyhood, her eyes wide open, guileless and questioning, above that painfully sensitive mouth.

Selena is indeed entirely different from Allison: in many female coming-of-age novels the blameless, bookish, shy, unattractive central character has a foil who is pretty, popular and outgoing, and very often with looser morals. In this case the contrast is extreme. Selena is by no means a virgin, though we only find out later how and to whom she loses her virginity.

There is also a huge social difference between the two girls: Allison’s mother Constance is discreet and aloof and runs a high-class dress shop – “the women of the town bought almost exclusively from her” – while Selena lives in a rundown shack with her hopeless mother and vile, violent, drunken and lecherous stepfather who rapes her and takes her virginity.

In the original manuscript, he was her birth father; the one change that Metalious agreed with her publisher before publication was that he should become her stepfather – it hardly lessens the shock when the rape happens.

“Selena was beautiful while Allison believed herself an unattractive girl, plump in the wrong places, flat in the wrong spots, too long in the legs and too round in the face.” Selena, on the other hand, is “well-developed for her age, with the curves of hips and breasts already discernible under the too short and often threadbare clothes that she wore.” She has “long dark hair that curled of its own accord in a softly beautiful fashion. Her eyes, too, were dark and slightly slanted, and she had a naturally red, full lipped mouth over well shaped startlingly white teeth.”

Selena is nowhere near as well-read as Allison but she’s much wiser; “wiser with the wisdom learned of poverty and wretchedness. At thirteen, she saw hopelessness as an old enemy, as persistent and inevitable as death.” Selena cannot understand “what in the world ailed Allison that she could be unhappy in surroundings like these, with a wonderful blonde mother, and a pink and white bedroom of her own.”

Unlike Allison, Selena covets the dresses in Constance’s shop. Constance “could understand a girl looking that way at the sight of a beautiful dress. The only time that Allison ever wore this expression was when she was reading.”

When Constance asks Selena to work part-time in her shop, Selena thinks she is in heaven. Wearing one of the dresses, Constance thinks Selena has “the look of a beautifully sensual, expensively kept woman.” Selena adores Constance; she thinks: “Someday, I’ll get out, and when I do, I’ll always wear beautiful clothes and talk in a soft voice, just like Mrs. McKenzie.”

Allison may not be popular with the girls – or indeed the boys, not that she cares about boys – but her teacher Miss Thornton likes her. She has a mission: “If I can teach something to one child, if I can awaken in only one child a sense of beauty, joy in truth, and admission of ignorance and a thirst for knowledge then I am fulfilled. One child, thought Miss Thornton, adjusting her old brown felt, and her mind fastened with love on Allison Mackenzie.”

Allison knows about Miss Thornton’s feelings for her – an unusual example of a teacher having a crush on a girl – but she believes it is “only because Miss Thornton was so ugly and plain herself.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Peyton Place — two 1956 reviews

. . . . . . . . . .

Allison’s mother has never told her the truth about her father, whom Allison believes to be dead, but who is in fact alive and well. Constance had an affair with him but they never married; he is a Scottish businessman and his name was also, confusingly, Allison. But he had a wife at the time of the affair and had no intention of marrying Constance, though he always provided for her and their daughter financially.

Constance left town, pregnant, before Allison’s birth and invented a fictitious, short lived marriage, coming back after Allison was born with a story that her imaginary husband was dead. To make the story work, she has had to subtract a year from Allison’s real age – Allison is a year older than she and everybody else believes.

Allison loves her absent father – or at least the false image she has built up of him – as well as her mother, though they have “little in common with each other; the mother was far too cold and practical a mind to understand the sensitive, dreaming child, and Allison too young and full of hopes and fancies to sympathize with her mother.”

Bookish Allison

Allison is bookish but does not get her love of reading from her mother: Constance “could not understand a twelve-year-old girl keeping her nose in a book. Other girls her age would have been continually in the shop, examining and exclaiming over the boxes of pretty dresses and underwear which arrived there almost daily.”

Unlike Selena, all Allison knows about life she has got from her reading. She has discovered a box of old books in the attic, and is fascinated by them; “she went from de Maupassant to James Hilton without a quiver. She read Goodbye, Mr Chips and wept in the darkness of her room for an hour while the last line of the story lingered in her mind. ‘I said goodbye to Chips the night before he died.’ Allison began to wonder about God and death.”

But what Allison loves most of all, better than books even, is being alone in the countryside just outside the town where she can “be free from the hatefulness that was school … For a little while she could find pleasure here and forget that her pleasures would be considered babyish and silly by older, more mature twelve-year-old girls.”

“Now that she was quiet and unafraid, she could pretend that she was a child again, and not a twelve-year-old who would be entering high school within less than another year, and who should be interested now in clothes and boys and pale rose lipstick… But away from this place she was awkward, loveless, pitifully aware that she lacked the attraction and poise which she believed that every other girl her age possessed …

There would not be many more days of contentment for Allison, for now she was twelve and soon would have to begin spending her life with people like the girls at school. She would be surrounded by them, and have to try hard to be one of them. She was sure that they would never accept her. They would laugh at her, ridicule her, and she would find herself living in a world where she was the only odd and different member of the population.”

Resisting the path to womanhood

Allison does not want to turn from a girl into a woman, does not want come of age, mentally or physically; the outward attributes of womanhood repel her. She hates the idea of “hair growing anywhere on her body. Selena already had hair under her arms which she shaved off once a month.” Selena tells Allison that she gets it all over with at once, “my period and my shave.”

Allison agrees this is a good idea but “as far as she was concerned, ‘periods’ were something that happened to other girls. She decided that she would never tolerate such things in herself.’ Allison sends off for a sex education book which she reads carefully to find out about periods; she clearly cannot contemplate asking her mother.

“Phooey, she thought disdainfully when she had finished studying the pamphlet. I’ll be the only woman in the whole world who won’t, and it’ll be written up in all the medical books.

She thought of ‘It’ as a large black bat, with wings outspread, and when she woke up on the morning of her thirteenth birthday to discover that ‘It’ was nothing of the kind, she was disappointed, disgusted and more than a little frightened.

But the reason she wept that she was not, after all, going to be as unique as she had wanted to be.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Peyton Place by Grace Metalious on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Despite its mauling by “serious” critics and its mangling by film and TV producers, the original novel’s reputation for lowbrow sleaze is completely unjustified: in its sensitive and perceptive treatment of both Allison and Selena it is as good a coming of age novel as many more vaunted classics.

It is certainly much better than Grace Metalious’s later novels, including its hastily written sequel, Return to Peyton Place, 1959, which follows Allison as she grows up to become a writer, writing scurrilous, thinly disguised portraits of the people in Peyton Place and, like her mother, has an affair with a married man. Success did not bring happiness to Metalious and she died of liver failure following years of heavy drinking at the age of thirty-nine in 1964.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Allison MacKenzie: Coming of Age in Peyton Place by Grace Metalious appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 22, 2021

Selections from Songs of the Elder Sisters (the Therīgāthā)

Songs of the Elder Sisters were composed during the Buddha’s lifetime, about 2,500 years ago. These women renounced home life and society, and joined the group of nuns founded by the Buddha. This selection of 14 poems from the Buddhist text known as the Therīgāthā were translated from Pāli by Francis Booth. See more of this translation of Songs of the Elder Sisters on Issuu.

These poignant songs are about loss of beauty, wealth and family, balanced by the greater gains of peace and wisdom through enlightenment in old age. All the songs are ascribed to particular women, whose names we know. They speak as individuals, not as wives, mothers and daughters.

Although Buddhist in intent, the songs are highly personal rather than pious and formal and are full of character and personality. They were passed down orally through chanting for 600 years before being written down and are among the earliest extant poems written by women. They also form the only canonical work in any religion written entirely by women.

Referring to a collection known as Verses of the Elder Nuns, the Therīgāthā, (Pāli: therī: elder in feminine form + gāthā: verses) consists of short poems dating from a three hundred year span beginning in the late 6th century BCE.

This collection of poems is believed to be the earliest text to record women’s spiritual journeys, and is the earliest known collection of women’s literature from India. What’s truly remarkable is that contrary to Virginia Woolf‘s famous (and often correct) claim that “anonymous was a woman,” the names of these ancient female poets are recorded.

This excellent analysis of the Therīgāthā from Zen Mountain Monastery gives a good historic background to this ancient text:

“… The adjective “first” and the Therīgāthā seem to go together. It is easy to see why. The Therīgāthā is an anthology of poems composed by some of the first Buddhists; while the poems of the Therīgāthā are clearly nowhere near as old as the poetry of the Rig Veda, for example, they are still some of the first poetry of India; the Therīgāthā ’s poems are some of the first poems by women in India; as a collection, the Therīgāthā is the first anthology of women’s literature in the world.” Read the rest in full here.

. . . . . . . . . .

Lost Beauty

Ambapali’s Song

Ah but when I was young I had beautiful hair

Glossy, curly and black like the colour of bees

Now my hair is like hemp or the bark of the trees

Ah, not false are the words of the teller of truth

With my hair filled with flowers and perfumed with scent

Thick as trees in the forest adorned with gold pins

Now my hair smells like dog’s fur all matted and thin

Ah, not false are the words of the teller of truth

I had eyebrows like crescents an artist would paint

And my eyes flashed like precious and radiant jewels

But the passing of time and the wrinkles were cruel

Ah, not false are the words of the teller of truth

With my beautiful nose and my features refined

And my ear lobes so soft how my teeth brightly shined

Now all yellow and ruined by age and by time

Ah, not false are the words of the teller of truth

Then my singing was sweet as the call of a bird

Like a cuckoo that warbles in the branches of trees

Now the music is broken and cracked with disease

Ah, not false are the words of the teller of truth

With my neck like a conch shell and smooth rounded arms

On my delicate hands rings and bracelets of gold

Now all withered and dried like an onion turned old

Ah, not false are the words of the teller of truth

In my young days my body was burnished and fine

And my breasts stood up proudly all shapely and round

Now my skin has turned baggy and sags to the ground

Ah, not false are the words of the teller of truth

In my youth I had thighs like an elephant’s trunk

And my calves and my ankles and feet were adorned

But with age all my limbs are now knotted and worn

Ah, not false are the words of the teller of truth

This magnificent body so beautiful then

Shows with time and with age how the truth is revealed

As a mansion looks fine ‘til the plaster has peeled

Ah, not false are the words of the teller of truth

. . . . . . . . . .

Anopama’s Song

The daughter of a house of wealth and fame

Well born in fortune and exalted name

A beauty celebrated through the land

A prize beyond a price to win my hand

Pursued and courted by the sons of kings

While merchant princes made rich offerings

A ruler promised treasuries of gold

And jewels equal to my weight eightfold

Gautama, worthy and enlightened one

In pity showed me life with passion gone

I shaved my head and left the world behind

Since seven nights all craving left my mind

. . . . . . . . . .

Vimala’s Song

Young and fine and drunk with beauty

Famous for my flawless face

Richly dressed and acting haughty

Putting others in their place

Painted and adorned with jewels

Standing at the brothel door

Like the hunter’s trap is cruel

Showing men delights in store

Teaching them my secret magic

Showing them my secret part

Now I see my life was tragic

Hating people in my heart

Now I live without possessions

Shaven headed, beg for alms

Now I conquered all obsession

Thoughts all gone now, cool and calm

. . . . . . . . . .

2 Grieving MothersKisogotami’s Song

The noblest friends can even make

The wisdom of a fool increase

So cultivate the wisest ones

And see the tide of pain decrease

The driver of the chariot

Says women’s lives are full of grief

He drives and tames the hearts of men

Heals suffering and brings relief

To share a husband, bear a child

The pain of being second wives

Make some take poison, slit their throats

So suffering through many lives

I lost a husband and two sons

I laid them on the funeral pyre

My mother, father, brother too

Have burned to ashes in that fire

Through tears of a thousand lives

I reached the final state of peace

My dart cut out, my burden shed

From suffering at last released

. . . . . . . . . .

Vasitthi’s Song

Crazy with grief for the death of my son

Wandering far with my senses all gone

Naked and ragged and living in dirt

Three years I suffered with hunger and thirst

One day the Buddha was travelling near

Tamer of hearts and defeater of fear

Hearing the teacher’s true wisdom explained

Now I’ve cast out all the causes of pain

. . . . . . . . . .

3 A Woman FreedPunna’s Song

Woman full is like the moon

Ripened on the fifteenth day

Full of wisdom, calm of mind

Darkness torn and thrown away

. . . . . . . . . .

Mutta’s Song

Woman freed is like the moon

Free from darkness and eclipse

Free in mind and free from debt

Free to live on alms and gifts

. . . . . . . . . .

Patacara’s Song

As men find wealth by planting crops

By ploughing fields and sowing seeds

By nourishing their wives and sons

They satisfy their earthly needs

So why could I, with virtuous mind

A woman pure in words and thoughts

Not find my peace and quench my thirst

By doing what the teacher taught?

Then one day as I bathed my feet

And watched the water run its course

I vowed to purify my mind

As men would train a noble horse

So in my cell I took the lamp

And from my bed I watched the flame

I grasped the wick and pulled it down

The light extinguished, peace remained

. . . . . . . . . .

Mettika’s Song

Walking weak and weary now

Youthful step long gone

Leaning on my walking staff

Trudging slowly on

Climbing up the mountain peak

Robe cast to the ground

Overturn my begging bowl

Freedom all around

. . . . . . . . . .

4 The Temptations of Mara, the Evil OneSela’s Song

Mara:

The solitary life brings no escape

Enjoy the world before it gets too late

Sela:

The pleasures of the body are like spears

And nothing you call joy do I hold dear

My love of earthly pleasure disappears

Go, tempter, you will gain no victory here

. . . . . . . . . .

Soma’s Song

Mara:

The wisdom of the sage is hard to gain

Beyond a woman’s nature to attain

Soma :

How can a woman’s nature interfere?

Our hearts are set, our way ahead is clear

My love of earthly pleasure disappears

Go, tempter, you will gain no victory here

. . . . . . . . . .

Khema’s Song

Mara:

As you are beautiful and I am young

Let us go in delight where songs are sung

Khema:

My body only fills me with disgust

Like swords and stakes to me are thoughts of lust

My love of earthly pleasure disappears

Go, tempter, you will gain no victory here

. . . . . . . . . .

Uppalavanna’s Song

Mara:

You stand under the blossoms in the wood

Exposed to evil men who mean no good

Uppalavanna:

A hundred thousand rascals could appear

I would not shake nor turn a hair in fear

Into your belly I could disappear

And in between your eyes could reappear

For I can rule the body with my thought

By following the way the Buddha taught

My love of earthly pleasure disappears

Go, tempter, you will gain no victory here

. . . . . . . . . .

Subha’s Song

Subha:

I was walking one day

In the beautiful woods

When a rascal appeared

Who was up to no good

So I said to him

Why do you stand in my way

Knowing purity’s rule

I have sworn to obey

For all passion has gone

From my unblemished mind

But the sensual pleasures

Have made your heart blind

The Man:

How can one as sweet as you

Give up life to be a nun

Dressing in the saffron robe

Come with me and have some fun

Trees exude the smell of spring

Forest beds are overgrown

Flowers bloom and pollen spreads

How can you go all alone?

Beasts of prey live in the woods

Elephants about to mate

Women unaccompanied

Risk a very frightening fate

You could be my golden doll

Wearing jewels, silk and pearls

In my palace in the wood

Waited on by serving girls

Garlanded and bathed in scent

On a bed of sandalwood

Like a lotus in the stream

Living long in maidenhood

Subha:

But what is it you see in this body of mine?

And what beauty appears in my face

When the cemetery calls and the body breaks down

Beauty vanishes without a trace

The Man:

Like a nymph inside the mountain

Spirit creature, my delight

Eyes like lotus blossoms blooming

Eyes that shine with radiant light

Like a spotless, golden vision

Long eyelashes, gentle gaze

Eyes that drive me wild with passion

Eyes to haunt me all my days

Subha:

Travel in the wrong direction

Try to leap the mountainside

Seek the moon to be your plaything

Try to trap the Buddha’s child

Purified myself of passion

Struck like sparks from blazing coal

Thrown down like a cup of poison

Truth has always been my goal

Just as puppets can dance

With their sticks and their strings

So my body is made

Of impermanent things

Like a beautiful painting

Seduces the mind

So illusions confused you

And rendered you blind

If you still want my body

To make me your prize

Then I’ll pluck out and give

To you one of my eyes

So your object of worship

You hold in your hand

And the true face of beauty

You now understand

The Man:

Try to hold a blazing fire

Try to grasp a poisonous snake

Lady, live without desire

Now I see my cruel mistake

Subha:

In the presence of the Buddha

There my sight will be regained

By the power of his merit

Passion conquered, peace attained

. . . . . . . . . .

More about the Elder Sisters and the Therīgāthā

Wikipedia The First Free Women: Poems of the Early Buddhist NunsMore English Translations of the Therīgāthā

Therīgāthā translation by Anagarika Mahendra Therīgāthā translation by Bhikkhu Sujato Therīgāthā Verses of the Elder Nuns Anthology of selected passages by Thanissaro Bhikkhu Psalms of the Early Buddhists: I. Psalms of the Sisters , London: Pali Text Society, 1909. Caroline A. F. Rhys Davids’ 1909 translation of the complete Therīgāthā. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Selections from Songs of the Elder Sisters (the Therīgāthā) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 18, 2021

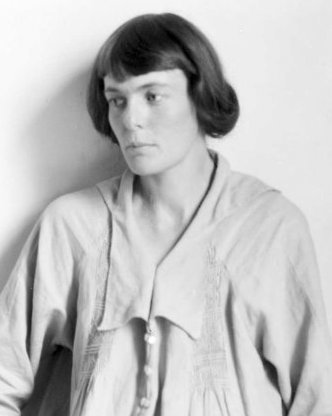

Renascence and Other Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay (full text)

Renascence and Other Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1917) was the first published collection by this eminent American poet. The book’s title reflects Millay’s 1912 poem of the same name, published when she was just nineteen, and still considered one of her finest. Here you’ll find the full text of this work.

From Dover, a recent publisher of this work that’s now in the public domain:

The poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892–1950) have been long admired for the lyric beauty that is especially characteristic of her early works. “Renascence,” the first of her poems to bring her public acclaim, was written when she was nineteen. Now one of the best-known American poems, it is a fervent and moving account of spiritual rebirth.

In 1917, “Renascence” was incorporated into her first volume of poetry, which is reprinted here, complete and unabridged, from the original edition. The 23 works in this first volume are fired with the romantic and independent spirit of youth that Edna St. Vincent Millay came to personify.

From the introductory Note by Joslyn Pine from this edition:

At Vassar, College Millay enjoyed significant celebrity not only as a literary light, but also for her work in theatre where, it is generally believed, she began having intimate relationships with women. In addition to her acting and poetry, she gained an awareness of social issues like the suffragist movement and women’s rights …

In 1917, the year of her graduation from Vassar, she published her first book, Renascence and Other Poems. She also moved to Greenwich Village in New York City where she dwelt in a 9-foot-wide attic, leading a rather bohemian and “poor but merry” life among fellow writers and intellectuals.

Here she devoted herself to writing poetry and prose pieces to bolster her perpetually scant finances, publishing the latter in various magazines under the pseudonym “Nancy Boyd” to keep her poetry pure from the taint of her “hack work,” as it was called by some.

More of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poetry on this site:

A Few Figs From Thistles (1921; full text) 10 Spring-Themed Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay 12 Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay. . . . . . . . .

More background on the title poem, “Renascence” (1912)

. . . . . . . . . . .

ContentsRenascenceInterimThe SuicideGod’s WorldAfternoon on a HillSorrowTavernAshes of LifeThe Little GhostKin to SorrowThree Songs of ShatteringThe ShroudThe DreamIndifferenceWitch-WifeBlightWhen the Year Grows OldSonnets. . . . . . . . . .

RenascenceAll I could see from where I stood

Was three long mountains and a wood;

I turned and looked another way,

And saw three islands in a bay.

So with my eyes I traced the line

Of the horizon, thin and fine,

Straight around till I was come

Back to where I’d started from;

And all I saw from where I stood

Was three long mountains and a wood.

Over these things I could not see;

These were the things that bounded me;

And I could touch them with my hand,

Almost, I thought, from where I stand.

And all at once things seemed so small

My breath came short, and scarce at all.

But, sure, the sky is big, I said;

Miles and miles above my head;

So here upon my back I’ll lie

And look my fill into the sky.

And so I looked, and, after all,

The sky was not so very tall.

The sky, I said, must somewhere stop,

And—sure enough!—I see the top!

The sky, I thought, is not so grand;

I ‘most could touch it with my hand!

And reaching up my hand to try,

I screamed to feel it touch the sky.

I screamed, and—lo!—Infinity

Came down and settled over me;

Forced back my scream into my chest,

Bent back my arm upon my breast,

And, pressing of the Undefined

The definition on my mind,

Held up before my eyes a glass

Through which my shrinking sight did pass

Until it seemed I must behold

Immensity made manifold;

Whispered to me a word whose sound

Deafened the air for worlds around,

And brought unmuffled to my ears

The gossiping of friendly spheres,

The creaking of the tented sky,

The ticking of Eternity.

I saw and heard, and knew at last

The How and Why of all things, past,

And present, and forevermore.

The Universe, cleft to the core,

Lay open to my probing sense

That, sick’ning, I would fain pluck thence

But could not,—nay! But needs must suck

At the great wound, and could not pluck

My lips away till I had drawn

All venom out.—Ah, fearful pawn!

For my omniscience paid I toll

In infinite remorse of soul.

All sin was of my sinning, all

Atoning mine, and mine the gall

Of all regret. Mine was the weight

Of every brooded wrong, the hate

That stood behind each envious thrust,

Mine every greed, mine every lust.

And all the while for every grief,

Each suffering, I craved relief

With individual desire,—

Craved all in vain! And felt fierce fire

About a thousand people crawl;

Perished with each,—then mourned for all!

A man was starving in Capri;

He moved his eyes and looked at me;

I felt his gaze, I heard his moan,

And knew his hunger as my own.

I saw at sea a great fog bank

Between two ships that struck and sank;

A thousand screams the heavens smote;

And every scream tore through my throat.

No hurt I did not feel, no death

That was not mine; mine each last breath

That, crying, met an answering cry

From the compassion that was I.

All suffering mine, and mine its rod;

Mine, pity like the pity of God.

Ah, awful weight! Infinity

Pressed down upon the finite Me!

My anguished spirit, like a bird,

Beating against my lips I heard;

Yet lay the weight so close about

There was no room for it without.

And so beneath the weight lay I

And suffered death, but could not die.

Long had I lain thus, craving death,

When quietly the earth beneath

Gave way, and inch by inch, so great

At last had grown the crushing weight,

Into the earth I sank till I

Full six feet under ground did lie,

And sank no more,—there is no weight

Can follow here, however great.

From off my breast I felt it roll,

And as it went my tortured soul

Burst forth and fled in such a gust

That all about me swirled the dust.

Deep in the earth I rested now;

Cool is its hand upon the brow

And soft its breast beneath the head

Of one who is so gladly dead.

And all at once, and over all

The pitying rain began to fall;

I lay and heard each pattering hoof

Upon my lowly, thatched roof,

And seemed to love the sound far more

Than ever I had done before.

For rain it hath a friendly sound

To one who’s six feet underground;

And scarce the friendly voice or face:

A grave is such a quiet place.

The rain, I said, is kind to come

And speak to me in my new home.

I would I were alive again

To kiss the fingers of the rain,

To drink into my eyes the shine

Of every slanting silver line,

To catch the freshened, fragrant breeze

From drenched and dripping apple-trees.

For soon the shower will be done,

And then the broad face of the sun

Will laugh above the rain-soaked earth

Until the world with answering mirth

Shakes joyously, and each round drop

Rolls, twinkling, from its grass-blade top.

How can I bear it; buried here,

While overhead the sky grows clear

And blue again after the storm?

O, multi-colored, multiform,

Beloved beauty over me,

That I shall never, never see

Again! Spring-silver, autumn-gold,

That I shall never more behold!

Sleeping your myriad magics through,

Close-sepulchred away from you!

O God, I cried, give me new birth,

And put me back upon the earth!

Upset each cloud’s gigantic gourd

And let the heavy rain, down-poured

In one big torrent, set me free,

Washing my grave away from me!

I ceased; and through the breathless hush

That answered me, the far-off rush

Of herald wings came whispering

Like music down the vibrant string

Of my ascending prayer, and—crash!

Before the wild wind’s whistling lash

The startled storm-clouds reared on high

And plunged in terror down the sky,

And the big rain in one black wave

Fell from the sky and struck my grave.

I know not how such things can be;

I only know there came to me

A fragrance such as never clings

To aught save happy living things;

A sound as of some joyous elf

Singing sweet songs to please himself,

And, through and over everything,

A sense of glad awakening.

The grass, a-tiptoe at my ear,

Whispering to me I could hear;

I felt the rain’s cool finger-tips

Brushed tenderly across my lips,

Laid gently on my sealed sight,

And all at once the heavy night

Fell from my eyes and I could see,—

A drenched and dripping apple-tree,

A last long line of silver rain,

A sky grown clear and blue again.

And as I looked a quickening gust

Of wind blew up to me and thrust

Into my face a miracle

Of orchard-breath, and with the smell,—

I know not how such things can be!—

I breathed my soul back into me.

Ah! Up then from the ground sprang I

And hailed the earth with such a cry

As is not heard save from a man

Who has been dead, and lives again.

About the trees my arms I wound;

Like one gone mad I hugged the ground;

I raised my quivering arms on high;

I laughed and laughed into the sky,

Till at my throat a strangling sob

Caught fiercely, and a great heart-throb

Sent instant tears into my eyes;

O God, I cried, no dark disguise

Can e’er hereafter hide from me

Thy radiant identity!

Thou canst not move across the grass

But my quick eyes will see Thee pass,

Nor speak, however silently,

But my hushed voice will answer Thee.

I know the path that tells Thy way

Through the cool eve of every day;

God, I can push the grass apart

And lay my finger on Thy heart!

The world stands out on either side

No wider than the heart is wide;

Above the world is stretched the sky,—

No higher than the soul is high.

The heart can push the sea and land

Farther away on either hand;

The soul can split the sky in two,

And let the face of God shine through.

But East and West will pinch the heart

That can not keep them pushed apart;

And he whose soul is flat—the sky

Will cave in on him by and by.

. . . . . . . . . .

InterimThe room is full of you!—As I came in

And closed the door behind me, all at once

A something in the air, intangible,

Yet stiff with meaning, struck my senses sick!—

Sharp, unfamiliar odors have destroyed

Each other room’s dear personality.

The heavy scent of damp, funereal flowers,—

The very essence, hush-distilled, of Death—

Has strangled that habitual breath of home

Whose expiration leaves all houses dead;

And wheresoe’er I look is hideous change.

Save here. Here ’twas as if a weed-choked gate

Had opened at my touch, and I had stepped

Into some long-forgot, enchanted, strange,

Sweet garden of a thousand years ago

And suddenly thought, “I have been here before!”

You are not here. I know that you are gone,

And will not ever enter here again.

And yet it seems to me, if I should speak,

Your silent step must wake across the hall;

If I should turn my head, that your sweet eyes

Would kiss me from the door.—So short a time

To teach my life its transposition to

This difficult and unaccustomed key!—

The room is as you left it; your last touch—

A thoughtless pressure, knowing not itself

As saintly—hallows now each simple thing;

Hallows and glorifies, and glows between

The dust’s grey fingers like a shielded light.

There is your book, just as you laid it down,

Face to the table,—I cannot believe

That you are gone!—Just then it seemed to me

You must be here. I almost laughed to think

How like reality the dream had been;

Yet knew before I laughed, and so was still.

That book, outspread, just as you laid it down!

Perhaps you thought, “I wonder what comes next,

And whether this or this will be the end”;

So rose, and left it, thinking to return.

Perhaps that chair, when you arose and passed

Out of the room, rocked silently a while

Ere it again was still. When you were gone

Forever from the room, perhaps that chair,

Stirred by your movement, rocked a little while,

Silently, to and fro…

And here are the last words your fingers wrote,

Scrawled in broad characters across a page

In this brown book I gave you. Here your hand,

Guiding your rapid pen, moved up and down.

Here with a looping knot you crossed a “t”,

And here another like it, just beyond

These two eccentric “e’s”. You were so small,

And wrote so brave a hand!

How strange it seems

That of all words these are the words you chose!

And yet a simple choice; you did not know

You would not write again. If you had known—

But then, it does not matter,—and indeed

If you had known there was so little time

You would have dropped your pen and come to me

And this page would be empty, and some phrase

Other than this would hold my wonder now.

Yet, since you could not know, and it befell

That these are the last words your fingers wrote,

There is a dignity some might not see

In this, “I picked the first sweet-pea to-day.”

To-day! Was there an opening bud beside it

You left until to-morrow?—O my love,

The things that withered,—and you came not back!

That day you filled this circle of my arms

That now is empty. (O my empty life!)

That day—that day you picked the first sweet-pea,—

And brought it in to show me! I recall

With terrible distinctness how the smell

Of your cool gardens drifted in with you.

I know, you held it up for me to see

And flushed because I looked not at the flower,

But at your face; and when behind my look

You saw such unmistakable intent

You laughed and brushed your flower against my lips.

(You were the fairest thing God ever made,

I think.) And then your hands above my heart

Drew down its stem into a fastening,

And while your head was bent I kissed your hair.

I wonder if you knew. (Beloved hands!

Somehow I cannot seem to see them still.

Somehow I cannot seem to see the dust

In your bright hair.) What is the need of Heaven

When earth can be so sweet?—If only God

Had let us love,—and show the world the way!

Strange cancellings must ink th’ eternal books

When love-crossed-out will bring the answer right!

That first sweet-pea! I wonder where it is.

It seems to me I laid it down somewhere,

And yet,—I am not sure. I am not sure,

Even, if it was white or pink; for then

‘Twas much like any other flower to me,

Save that it was the first. I did not know,

Then, that it was the last. If I had known—

But then, it does not matter. Strange how few,

After all’s said and done, the things that are

Of moment.

Few indeed! When I can make

Of ten small words a rope to hang the world!

“I had you and I have you now no more.”

There, there it dangles,—where’s the little truth

That can for long keep footing under that

When its slack syllables tighten to a thought?

Here, let me write it down! I wish to see

Just how a thing like that will look on paper!

“*I had you and I have you now no more*.”

O little words, how can you run so straight

Across the page, beneath the weight you bear?

How can you fall apart, whom such a theme

Has bound together, and hereafter aid

In trivial expression, that have been

So hideously dignified?—Would God

That tearing you apart would tear the thread

I strung you on! Would God—O God, my mind

Stretches asunder on this merciless rack

Of imagery! O, let me sleep a while!

Would I could sleep, and wake to find me back

In that sweet summer afternoon with you.

Summer? ‘Tis summer still by the calendar!

How easily could God, if He so willed,

Set back the world a little turn or two!

Correct its griefs, and bring its joys again!

We were so wholly one I had not thought

That we could die apart. I had not thought

That I could move,—and you be stiff and still!

That I could speak,—and you perforce be dumb!

I think our heart-strings were, like warp and woof

In some firm fabric, woven in and out;

Your golden filaments in fair design

Across my duller fibre. And to-day

The shining strip is rent; the exquisite

Fine pattern is destroyed; part of your heart

Aches in my breast; part of my heart lies chilled

In the damp earth with you. I have been torn

In two, and suffer for the rest of me.

What is my life to me? And what am I

To life,—a ship whose star has guttered out?

A Fear that in the deep night starts awake

Perpetually, to find its senses strained

Against the taut strings of the quivering air,

Awaiting the return of some dread chord?

Dark, Dark, is all I find for metaphor;

All else were contrast,—save that contrast’s wall

Is down, and all opposed things flow together

Into a vast monotony, where night

And day, and frost and thaw, and death and life,

Are synonyms. What now—what now to me

Are all the jabbering birds and foolish flowers

That clutter up the world? You were my song!

Now, let discord scream! You were my flower!

Now let the world grow weeds! For I shall not

Plant things above your grave—(the common balm

Of the conventional woe for its own wound!)

Amid sensations rendered negative

By your elimination stands to-day,

Certain, unmixed, the element of grief;

I sorrow; and I shall not mock my truth

With travesties of suffering, nor seek

To effigy its incorporeal bulk

In little wry-faced images of woe.

I cannot call you back; and I desire

No utterance of my immaterial voice.

I cannot even turn my face this way

Or that, and say, “My face is turned to you”;

I know not where you are, I do not know

If Heaven hold you or if earth transmute,

Body and soul, you into earth again;

But this I know:—not for one second’s space

Shall I insult my sight with visionings

Such as the credulous crowd so eager-eyed

Beholds, self-conjured, in the empty air.

Let the world wail! Let drip its easy tears!

My sorrow shall be dumb!

—What do I say?

God! God!—God pity me! Am I gone mad

That I should spit upon a rosary?

Am I become so shrunken? Would to God

I too might feel that frenzied faith whose touch

Makes temporal the most enduring grief;

Though it must walk a while, as is its wont,

With wild lamenting! Would I too might weep

Where weeps the world and hangs its piteous wreaths

For its new dead! Not Truth, but Faith, it is

That keeps the world alive. If all at once

Faith were to slacken,—that unconscious faith

Which must, I know, yet be the corner-stone

Of all believing,—birds now flying fearless

Across would drop in terror to the earth;

Fishes would drown; and the all-governing reins

Would tangle in the frantic hands of God

And the worlds gallop headlong to destruction!

O God, I see it now, and my sick brain

Staggers and swoons! How often over me

Flashes this breathlessness of sudden sight

In which I see the universe unrolled

Before me like a scroll and read thereon

Chaos and Doom, where helpless planets whirl

Dizzily round and round and round and round,

Like tops across a table, gathering speed

With every spin, to waver on the edge

One instant—looking over—and the next

To shudder and lurch forward out of sight—

. . . . . . .

Ah, I am worn out—I am wearied out—

It is too much—I am but flesh and blood,

And I must sleep. Though you were dead again,

I am but flesh and blood and I must sleep.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Suicide“Curse thee, Life, I will live with thee no more!

Thou hast mocked me, starved me, beat my body sore!

And all for a pledge that was not pledged by me,

I have kissed thy crust and eaten sparingly

That I might eat again, and met thy sneers

With deprecations, and thy blows with tears,—

Aye, from thy glutted lash, glad, crawled away,

As if spent passion were a holiday!

And now I go. Nor threat, nor easy vow

Of tardy kindness can avail thee now

With me, whence fear and faith alike are flown;

Lonely I came, and I depart alone,

And know not where nor unto whom I go;

But that thou canst not follow me I know.”

Thus I to Life, and ceased; but through my brain

My thought ran still, until I spake again:

“Ah, but I go not as I came,—no trace

Is mine to bear away of that old grace

I brought! I have been heated in thy fires,

Bent by thy hands, fashioned to thy desires,

Thy mark is on me! I am not the same

Nor ever more shall be, as when I came.

Ashes am I of all that once I seemed.

In me all’s sunk that leapt, and all that dreamed

Is wakeful for alarm,—oh, shame to thee,

For the ill change that thou hast wrought in me,

Who laugh no more nor lift my throat to sing!

Ah, Life, I would have been a pleasant thing

To have about the house when I was grown

If thou hadst left my little joys alone!

I asked of thee no favor save this one:

That thou wouldst leave me playing in the sun!

And this thou didst deny, calling my name

Insistently, until I rose and came.

I saw the sun no more.—It were not well

So long on these unpleasant thoughts to dwell,

Need I arise to-morrow and renew

Again my hated tasks, but I am through

With all things save my thoughts and this one night,

So that in truth I seem already quite

Free and remote from thee,—I feel no haste

And no reluctance to depart; I taste

Merely, with thoughtful mien, an unknown draught,

That in a little while I shall have quaffed.”

Thus I to Life, and ceased, and slightly smiled,

Looking at nothing; and my thin dreams filed

Before me one by one till once again

I set new words unto an old refrain:

“Treasures thou hast that never have been mine!

Warm lights in many a secret chamber shine

Of thy gaunt house, and gusts of song have blown

Like blossoms out to me that sat alone!

And I have waited well for thee to show

If any share were mine,—and now I go!

Nothing I leave, and if I naught attain

I shall but come into mine own again!”

Thus I to Life, and ceased, and spake no more,

But turning, straightway, sought a certain door

In the rear wall. Heavy it was, and low

And dark,—a way by which none e’er would go

That other exit had, and never knock

Was heard thereat,—bearing a curious lock

Some chance had shown me fashioned faultily,

Whereof Life held content the useless key,

And great coarse hinges, thick and rough with rust,

Whose sudden voice across a silence must,

I knew, be harsh and horrible to hear,—

A strange door, ugly like a dwarf.—So near

I came I felt upon my feet the chill

Of acid wind creeping across the sill.

So stood longtime, till over me at last

Came weariness, and all things other passed

To make it room; the still night drifted deep

Like snow about me, and I longed for sleep.

But, suddenly, marking the morning hour,

Bayed the deep-throated bell within the tower!

Startled, I raised my head,—and with a shout

Laid hold upon the latch,—and was without.

. . . . . . .

Ah, long-forgotten, well-remembered road,

Leading me back unto my old abode,

My father’s house! There in the night I came,

And found them feasting, and all things the same

As they had been before. A splendour hung

Upon the walls, and such sweet songs were sung

As, echoing out of very long ago,

Had called me from the house of Life, I know.

So fair their raiment shone I looked in shame

On the unlovely garb in which I came;

Then straightway at my hesitancy mocked:

“It is my father’s house!” I said and knocked;

And the door opened. To the shining crowd

Tattered and dark I entered, like a cloud,

Seeing no face but his; to him I crept,

And “Father!” I cried, and clasped his knees, and wept.

Ah, days of joy that followed! All alone

I wandered through the house. My own, my own,

My own to touch, my own to taste and smell,

All I had lacked so long and loved so well!

None shook me out of sleep, nor hushed my song,

Nor called me in from the sunlight all day long.

I know not when the wonder came to me

Of what my father’s business might be,

And whither fared and on what errands bent

The tall and gracious messengers he sent.

Yet one day with no song from dawn till night

Wondering, I sat, and watched them out of sight.

And the next day I called; and on the third

Asked them if I might go,—but no one heard.

Then, sick with longing, I arose at last

And went unto my father,—in that vast

Chamber wherein he for so many years

Has sat, surrounded by his charts and spheres.

“Father,” I said, “Father, I cannot play

The harp that thou didst give me, and all day

I sit in idleness, while to and fro

About me thy serene, grave servants go;

And I am weary of my lonely ease.

Better a perilous journey overseas

Away from thee, than this, the life I lead,

To sit all day in the sunshine like a weed

That grows to naught,—I love thee more than they

Who serve thee most; yet serve thee in no way.

Father, I beg of thee a little task

To dignify my days,—’tis all I ask

Forever, but forever, this denied,

I perish.”

“Child,” my father’s voice replied,

“All things thy fancy hath desired of me

Thou hast received. I have prepared for thee

Within my house a spacious chamber, where

Are delicate things to handle and to wear,

And all these things are thine. Dost thou love song?

My minstrels shall attend thee all day long.

Or sigh for flowers? My fairest gardens stand

Open as fields to thee on every hand.

And all thy days this word shall hold the same:

No pleasure shalt thou lack that thou shalt name.

But as for tasks—” he smiled, and shook his head;

“Thou hadst thy task, and laidst it by”, he said.

. . . . . . . . . .

God’s WorldO world, I cannot hold thee close enough!

Thy winds, thy wide grey skies!

Thy mists, that roll and rise!

Thy woods, this autumn day, that ache and sag

And all but cry with colour! That gaunt crag

To crush! To lift the lean of that black bluff!

World, World, I cannot get thee close enough!

Long have I known a glory in it all,

But never knew I this;

Here such a passion is

As stretcheth me apart,—Lord, I do fear

Thou’st made the world too beautiful this year;

My soul is all but out of me,—let fall

No burning leaf; prithee, let no bird call.

. . . . . . . . . .

Afternoon on a HillI will be the gladdest thing

Under the sun!

I will touch a hundred flowers

And not pick one.

I will look at cliffs and clouds

With quiet eyes,

Watch the wind bow down the grass,

And the grass rise.

And when lights begin to show

Up from the town,

I will mark which must be mine,

And then start down!

. . . . . . . . . .

SorrowSorrow like a ceaseless rain

Beats upon my heart.

People twist and scream in pain,—

Dawn will find them still again;

This has neither wax nor wane,

Neither stop nor start.

People dress and go to town;

I sit in my chair.

All my thoughts are slow and brown:

Standing up or sitting down

Little matters, or what gown

Or what shoes I wear.

. . . . . . . . . .

TavernI’ll keep a little tavern

Below the high hill’s crest,

Wherein all grey-eyed people

May set them down and rest.

There shall be plates a-plenty,

And mugs to melt the chill

Of all the grey-eyed people

Who happen up the hill.

There sound will sleep the traveller,

And dream his journey’s end,

But I will rouse at midnight

The falling fire to tend.

Aye, ’tis a curious fancy—

But all the good I know

Was taught me out of two grey eyes

A long time ago.

. . . . . . . . . .

Ashes of LifeLove has gone and left me and the days are all alike;

Eat I must, and sleep I will,—and would that night were here!

But ah!—to lie awake and hear the slow hours strike!

Would that it were day again!—with twilight near!

Love has gone and left me and I don’t know what to do;

This or that or what you will is all the same to me;

But all the things that I begin I leave before I’m through,—

There’s little use in anything as far as I can see.

Love has gone and left me,—and the neighbors knock and borrow,

And life goes on forever like the gnawing of a mouse,—

And to-morrow and to-morrow and to-morrow and to-morrow

There’s this little street and this little house.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Little GhostI knew her for a little ghost

That in my garden walked;

The wall is high—higher than most—

And the green gate was locked.

And yet I did not think of that

Till after she was gone—

I knew her by the broad white hat,

All ruffled, she had on.

By the dear ruffles round her feet,

By her small hands that hung

In their lace mitts, austere and sweet,

Her gown’s white folds among.

I watched to see if she would stay,

What she would do—and oh!

She looked as if she liked the way

I let my garden grow!

She bent above my favourite mint

With conscious garden grace,

She smiled and smiled—there was no hint

Of sadness in her face.

She held her gown on either side

To let her slippers show,

And up the walk she went with pride,

The way great ladies go.

And where the wall is built in new

And is of ivy bare

She paused—then opened and passed through

A gate that once was there.

. . . . . . . . . .

Kin to SorrowAm I kin to Sorrow,

That so oft

Falls the knocker of my door—

Neither loud nor soft,

But as long accustomed,

Under Sorrow’s hand?

Marigolds around the step

And rosemary stand,

And then comes Sorrow—

And what does Sorrow care

For the rosemary

Or the marigolds there?

Am I kin to Sorrow?

Are we kin?

That so oft upon my door—

*Oh, come in*!

. . . . . . . . . .

Three Songs of ShatteringI

The first rose on my rose-tree

Budded, bloomed, and shattered,

During sad days when to me

Nothing mattered.

Grief of grief has drained me clean;

Still it seems a pity

No one saw,—it must have been

Very pretty.

II

Let the little birds sing;

Let the little lambs play;

Spring is here; and so ’tis spring;—

But not in the old way!

I recall a place

Where a plum-tree grew;

There you lifted up your face,

And blossoms covered you.

If the little birds sing,

And the little lambs play,

Spring is here; and so ’tis spring—

But not in the old way!

III

All the dog-wood blossoms are underneath the tree!

Ere spring was going—ah, spring is gone!

And there comes no summer to the like of you and me,—

Blossom time is early, but no fruit sets on.

All the dog-wood blossoms are underneath the tree,

Browned at the edges, turned in a day;

And I would with all my heart they trimmed a mound for me,

And weeds were tall on all the paths that led that way!

. . . . . . . . . .

The ShroudDeath, I say, my heart is bowed

Unto thine,—O mother!

This red gown will make a shroud

Good as any other!

(I, that would not wait to wear

My own bridal things,

In a dress dark as my hair

Made my answerings.

I, to-night, that till he came

Could not, could not wait,

In a gown as bright as flame

Held for them the gate.)

Death, I say, my heart is bowed

Unto thine,—O mother!

This red gown will make a shroud

Good as any other!

. . . . . . . . . .

The DreamLove, if I weep it will not matter,

And if you laugh I shall not care;

Foolish am I to think about it,

But it is good to feel you there.

Love, in my sleep I dreamed of waking,—

White and awful the moonlight reached

Over the floor, and somewhere, somewhere,

There was a shutter loose,—it screeched!

Swung in the wind,—and no wind blowing!—

I was afraid, and turned to you,

Put out my hand to you for comfort,—

And you were gone! Cold, cold as dew,

Under my hand the moonlight lay!

Love, if you laugh I shall not care,

But if I weep it will not matter,—

Ah, it is good to feel you there!

. . . . . . . . . .

IndifferenceI said,—for Love was laggard, O, Love was slow to come,—

“I’ll hear his step and know his step when I am warm in bed;

But I’ll never leave my pillow, though there be some

As would let him in—and take him in with tears!” I said.

I lay,—for Love was laggard, O, he came not until dawn,—

I lay and listened for his step and could not get to sleep;

And he found me at my window with my big cloak on,

All sorry with the tears some folks might weep!

. . . . . . . . . .

Witch-WifeShe is neither pink nor pale,

And she never will be all mine;

She learned her hands in a fairy-tale,

And her mouth on a valentine.

She has more hair than she needs;

In the sun ’tis a woe to me!

And her voice is a string of colored beads,

Or steps leading into the sea.

She loves me all that she can,

And her ways to my ways resign;

But she was not made for any man,

And she never will be all mine.

. . . . . . . . . .

BlightHard seeds of hate I planted

That should by now be grown,—

Rough stalks, and from thick stamens

A poisonous pollen blown,

And odors rank, unbreathable,

From dark corollas thrown!

At dawn from my damp garden

I shook the chilly dew;

The thin boughs locked behind me

That sprang to let me through;

The blossoms slept,—I sought a place

Where nothing lovely grew.

And there, when day was breaking,

I knelt and looked around:

The light was near, the silence

Was palpitant with sound;

I drew my hate from out my breast

And thrust it in the ground.

Oh, ye so fiercely tended,

Ye little seeds of hate!

I bent above your growing

Early and noon and late,

Yet are ye drooped and pitiful,—

I cannot rear ye straight!

The sun seeks out my garden,

No nook is left in shade,

No mist nor mold nor mildew

Endures on any blade,

Sweet rain slants under every bough:

Ye falter, and ye fade.

. . . . . . . . . .

When the Year Grows OldI cannot but remember

When the year grows old—

October—November—

How she disliked the cold!

She used to watch the swallows

Go down across the sky,

And turn from the window

With a little sharp sigh.

And often when the brown leaves

Were brittle on the ground,

And the wind in the chimney

Made a melancholy sound,

She had a look about her

That I wish I could forget—

The look of a scared thing

Sitting in a net!

Oh, beautiful at nightfall

The soft spitting snow!

And beautiful the bare boughs

Rubbing to and fro!

But the roaring of the fire,

And the warmth of fur,

And the boiling of the kettle

Were beautiful to her!

I cannot but remember

When the year grows old—

October—November—

How she disliked the cold!

. . . . . . . . . .

SonnetsI

Thou art not lovelier than lilacs,—no,

Nor honeysuckle; thou art not more fair

Than small white single poppies,—I can bear

Thy beauty; though I bend before thee, though

From left to right, not knowing where to go,

I turn my troubled eyes, nor here nor there

Find any refuge from thee, yet I swear

So has it been with mist,—with moonlight so.

Like him who day by day unto his draught

Of delicate poison adds him one drop more

Till he may drink unharmed the death of ten,

Even so, inured to beauty, who have quaffed

Each hour more deeply than the hour before,

I drink—and live—what has destroyed some men.

II

Time does not bring relief; you all have lied

Who told me time would ease me of my pain!

I miss him in the weeping of the rain;

I want him at the shrinking of the tide;

The old snows melt from every mountain-side,

And last year’s leaves are smoke in every lane;

But last year’s bitter loving must remain