Nava Atlas's Blog, page 40

May 24, 2021

Rosamond du Jardin and the American Midcentury Teen Novel

Before there was a designated Young Adult category in publishing, Rosamond du Jardin (1902 – 1963) was known for her novels for the teen reader. Once dismissed as formulaic and dated, her novels are getting a second look, especially in gender studies. Literary critic Claudia Mills wrote that “they are illuminating as cultural documents, revealing how the values of their decade were transmitted to young readers via the vehicle of story.”

This re-introduction to du Jardin’s books and heroines is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

Rosamond du Jardin had written four adult novels and a large number of light short stories for women’s magazines before she started to write books for the teenage market.

She became very prolific and successful, publishing seventeen young adult novels including four Tobey Haydon books, beginning with Practically Seventeen, from 1949 to 1951; two books about Midge Haydon (Tobey’s younger sister) from 1958 to 1961; four books in the Marcy Rhodes series from 1950 to 1957 and four in the Pam and Penny Howard series from 1950 to 1959. All these have recently been republished as physical and electronic books by specialist publisher Image Cascade.

. . . . . . . . . .

Tobey Haydon: Practically Seventeen (1949)

‘My name is Tobey Haydon and I am practically seventeen years old, since my sixteenth birthday was five whole months ago.’

According to Tobey she is, ‘older than my sixteen years in lots of ways, I think.’ This of course is how most sixteen-year-olds feel, including the fictional ones. Tobey (note the gender-ambivalent name) begins by introducing herself and her family, including her sisters and her ‘fairly modern’ parents:

“Ours is quite a large family, as families go nowadays. First there are my mother and father, who are pretty old, in their 40s. Still they are fairly modern in their ideas. My father is tall and thinnish and has a pleasant face with lots of laugh wrinkles. He claims that any man, completely surrounded by females in his own home, would go crazy without a sense of humor and that he has had to develop his in self defense.

Sometimes his wit is a little corny, as is often the case with older people. But none of us mind. He is really sweet, as fathers go. My mother is very well satisfied with him, too. Her only complaint is that his job as a salesman of plumbing supplies takes him away from home on occasional out-of-town trips, during which time she seems to miss him very much indeed.

My mother thinks she is overweight and she is always talking about dieting and losing ten pounds, although compared with the mothers of some of my friends she has a very nice figure.”

Tobey has two older sisters; they are horrid to her; she acts as a kind of Cinderella to them, though the sisters are by no means ugly – as well as a younger sister. Janet, the oldest, is twenty-three with ‘dark red hair and very blue eyes and the kind of figure that rates admiring whistles on street corners,’ though she is married and has a baby known as Toots, ‘a bundle of fiendish energy aged three,’ who is living with the family while Janet’s husband is working away.

Next is her sister Alicia, who is ‘twenty and beautiful, if you care for blondes.’ Alicia, who has just got engaged, is mean and spiteful to Tobey and ‘hasn’t a smidgen of a sense of humor, although how this can be true of one of my father’s daughters is difficult to see.’ Finally, Tobey has:

“… Quite a young sister named Marjorie, but inevitably called Midge. She has a lot more freckles than I, sandy hair that she wears braided in pigtails, and skinny legs. She may improve, though, as she gets older. Right now she is only eight and my father frequently refers to her as The After-thought, this being an example of one of his more corny jokes.”

The recently-engaged Alicia and her fiancé are ‘always kissing. Now I personally, have nothing against this form of amusement, particularly for engaged couples. Still I should think they might want to do something else for a change now and then.’ Tobey does not specify, indeed does not appear to know, what other things engaged couples might do for a change.

Tobey has a boyfriend called Brose who takes her to the movies but does not apparently do very much else with her; on a date with him she puts on lipstick which she has ‘borrowed’ from one of the sisters but she finds it ‘very difficult to maintain any glamour whatever in a family with so many women around, especially sisters.’ They all, including Midge and her mother, mock Tobey’s attempts to look grown-up.

Tobey, like most of the heroines in this genre, is bookish and serious rather than glamorous and flirtatious. Her mother tries to get her to make more of herself: ‘do stop slumping. You have curvature of the spine.’ But still, Tobey has learned some womanly wiles from her older sisters.

‘Brose is really wonderful. I wouldn’t admit this publicly, because it doesn’t pay to let your true opinion of a man get around. Either it goes to his head, or some of your girlfriends decide to try to take him away from you if he’s that terrific. But I am pretty crazy about Brose.’

Tobey certainly does not want to rush into marriage; she has the example of Janet, at twenty-four, who ‘sees life sort of passing her by and her husband’s faraway and she is growing old and older and what does the future hold for her?’ What indeed.

The Tobey and Midge Heydon series

Practically SeventeenClass RingBoy TroubleThe Real ThingWedding in the FamilyOne of the Crowd. . . . . . . . . .

Marcy Rhodes: Wait for Marcy, 1950

Marcy is a tomboy. But for Christmas her grandmother has bought her – at Marcy’s request – a white net ‘formal,’ a dress to be worn to parties or other formal occasions; another Cinderella reference perhaps (Disney’s film of Cinderella appeared in 1950, too late for du Jardin to have seen it before she wrote these last two novels; Marcia Brown’s popular, illustrated retelling of Perrault’s version of the story was not published until 1955).

Marcy does not really do parties and has never worn the dress. As the novel opens she is sitting:

“… Sprawled comfortably crosswise in a slipcovered chair, deeply engrossed in her favorite magazine. The white shirt she wore had long since been discarded by her father, her blue jeans were deeply cuffed. Floppy moccasins hung from her toes. At fifteen Marcy was dark and slim, with brown hair curled under in a soft bell. Hers were the sort of looks that might easily develop into real loveliness as she grew older.”

Still, despite her tomboyish dress sense, Marcy envies her best friend’s looks; she ‘would gladly have traded high cheek bones, wide dark eyes and golden tan skin for the blonde, blue-eyed prettiness possessed by her closest friend, Liz Kendall.’

Unlike Tobey and Cinderella, Marcy has no sisters, though she does have an older brother, Ken. Older brothers of course are an annoyance, always seeking to embarrass their sister, though Betty Cornell advised that ‘an older brother is about the best social insurance any teen-ager can have.’

Like Tobey’s, Marcy’s mother is ‘an agreeable-looking woman, just verging on plumpness, whose fair hair was only lightly frosted with grey.’ Also like Tobey, she considers that her parents, ‘on the whole, were fairly reasonable,’ though not when her mother starts urging her to go to the school dance, if only so she can wear the formal dress.

“Marcy felt a sick sort of sensation in her tummy. The very first suitable occasion. A dance in the big gym at High, with paper festoons and the lights softened and all the couples, all the girls and their dates, whirling and swaying to just the sort of music that was coming from the radio now. Her lovely white formal would fit into the picture perfectly. But before she could wear it, before she could be a part of the entrancing seen in her mind, someone – who, she wondered if little desperately? – would have to invite her to go with him.

Grow up, why don’t you? That was what Ken had said just now. Marcy was trying, but in some respects it wasn’t easy.”

The Marcy Rhodes series

Wait for MarcyMarcy Catches UpA Man for MarcySenior Prom. . . . . . . . . .

Penny and Pam Howard: Double Date (1951)

Penny and Pam Howard are twin sisters but have very different personalities; authors of teen novels often use the device of a sister or best friend with an opposite personality to the protagonist; usually she is shy and bookish while the sister/friend is glamorous and popular. The four Penny and Pam novels, though written in the third person, are seen from the perspective of Penny, the introvert.

Pam is outgoing and popular, a Sub-Deb who has read and digested Betty Cornell’s advice. Although they are physically identical, Penny is less gregarious, more shy and reticent. When we see the twins at home, ‘Penny had been intent on her homework, curled on the couch, surrounded by books. Pam had been lying in front of the record-player, dreamily listening to Perry Como.’ Du Jardin gives us access to Penny’s thoughts while Pam is chatting to two boys they have just met:

How could twin sisters, who looked so much alike that most people couldn’t tell them apart, be so unlike inside? She had pondered the question many times before and found no answer. How could Pam chat on so animatedly, so effortlessly, keeping these boys she scarcely knew interested and amused, instilling in them a desire to get better acquainted?

Penny could think of nothing at all to add to Pam’s running comments. Beside her sister she felt leaden and dull and miserably aware of the poor impression she was making. Trudging along with the others, penny spoke only when spoken to directly. Casual, friendly talk eddied about her like a warm current, while she contributed little more than monosyllables. Not that the others seemed to notice. Pam’s voice filled any void that might otherwise have been left by Penny’s silence.

Rosamond du Jardin has presumably chosen to focus on the socially-awkward twin deliberately – she probably assumed, and probably correctly, that teenage girls who read novels like hers rather than Ladies Home Journal columns would themselves be socially awkward and identify more with Penny than Pam, the girl curled up on the couch surrounded by books rather than the girl dreamily listening to crooners. Read in another way of course, Penny is Pam’s alter ego, the girl she wants to be, the girl she – and her readers – aspire to be.

The Penny and Pam Howard series

Double DateDouble FeatureShowboat SummerDouble Wedding. . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

Interestingly, the decline of the teen novel coincided with the decline of the crooner. Perry Como (who was old enough to be Penny and Pam’s father) was superseded by the likes of Ladies Home Journal’s columnist Pat Boone, born in 1934, but he was already one of the last of a generation of singers whom teenage girls could listen to with their parents: the same year Boone released his first record, 1954, Elvis Presley was already recording and in 1956 when Presley released Heartbreak Hotel, the era of parent-friendly music was over.

Mothers, and especially fathers, of teenage girls would never again sit round their teenage daughter’s record player singing along with her. Or watch their idols on TV: Elvis’s suggestive gyrations were first seen on the Ed Sullivan show on September 9, 1956, performing Ready Teddy and Hound Dog to the horror of parents all across America.

Elvis was paid $50,000 for three appearances on the show; the first reached 82.6% of the American TV audience. By his third appearance protests from concerned parents ensured that he was filmed only from the waist up. But it was too late; teenage rebellion had begun and teenage girls began to stop wanting to listen to music with their mothers, let alone become them.

. . . . . . . . . .

Rosamond du Jardin page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Rosamond du Jardin and the American Midcentury Teen Novel appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 23, 2021

Diana and Persis — Louisa May Alcott’s Unfinished Novel

Susan Bailey of Louisa May Alcott is My Passion describes Diana and Persis, Louisa May Alcott‘s unfinished novel, as compelling, revealing, biographical, and thus, tragically incomplete:

By the 1870s, Louisa May Alcott and her baby sister May had become close companions. Although quite different in temperament, both shared that burning ambition to become the artists they were meant to be – Louisa as a best-selling author, and May as an acclaimed painter, exhibiting at the Paris Salon.

Unearthing a treasure

In the 1970s Alcott scholar Sarah Elbert discovered an untitled manuscript of 138 pages at the Houghton Library at Harvard University. Titling it Diana and Persis, the book was published in 1978. There are a couple of cryptic mentions, first in Louisa’s journal, dated December of 1878:

“ … begin work on an art novel, with May’s romance for its thread.” (page 211, The Journals of Louisa May Alcott, edited by Joel Myerson and Daniel Shealy; Madeleine B. Stern, associate editor).

And in May’s journal, dated January 28, 1879:

“Louisa is at the Bellevue writing her Art story in which some of my adventures will appear.” (page 7, Diana and Persis, edited by Sarah Elbert).

Introducing Diana and Persis

The story focuses on two women artists: the elder Diana, a sculptor, modeled somewhat after Louisa; and the younger Persis, modeled after May. Both are dedicated to their art to the exclusion of all else (although Diana appears to be more successful at this than Percy in the beginning as she has renounced marriage and family while Percy is distracted by suitors).

Percy makes the decision to study in Paris, having received financial support from her grandmother. She understands that she is distracted:

“If we give ourselves entirely to art we must trample on Nature occasionally; so in escaping from the lovers who annoy me to the work I prefer I must also turn my back on the last of my kindred and my dearest friend.” (Diana and Persis, page 54)

Diana is encouraged by her friend’s decision despite the fact that the two, close as sisters, will be separated by great distance. Yet she still feels compelled to dispel advice:

“’Don’t look for it [artistic inspiration] in marriage that is too costly an experiment for us. Flee from temptation and do not dream of spoiling your life but any common place romance, I implore you,’ cried Diane earnestly, and this was not the first time she had given the same advice.” (page 57)

. . . . . . . . .

May Alcott Nieriker: Thoroughly Modern Woman

. . . . . . . . .

Despite Percy’s serious ambition, she also desires a husband and children. She wanted it all and was convinced it was doable. She confessed to Diana regarding her “hungry heart” as well as her ambition, admitting that “art alone does not seem to satisfy me as it does you.” (Ibid)

This sounds very much like May.

Diana as Louisa

In contrast, Diana echoes what Louisa wished she could be – free to pursue her writing without distraction of family duty, something with which she was continually burdened:

“Denying herself the pleasures of youth, the honors of sex and beauty, the joys of love, the solaces of home, she went on her steadfast way, unresting and unhasting as a star; as cold and brilliant and remote to all except the few who had discovered hidden fires in this fair planet. Bread and the right to work was all she asked of the world as yet. One friendship was the only luxury she allowed herself and in this she found not only the solace but the stimulant she needed, for it was a most sincere and sympathetic bond.” (page 64)

The next three chapters describe the following:

Percy’s success (taken from May’s letters to the family) with her studies and her acceptance into the Paris Salon.Diana’s subsequent visit to Europe and her encounter with a brilliant widowed sculptor, Stafford, and his young son Nino.Diana’s visit with Percy, who has married August and born a child.The visit

Unlike Louisa who was hampered by her responsibilities and health issues, Diana was able to meet Percy’s husband and child and witness her friend’s triumph in “having it all.” Yet at the same time Diana notices signs of Percy being drawn away from her art, witnessing the dusty easel and dried paint on the palette in her studio.

As progressive as husband August appears to be (“I believe a woman can and ought to have both if she has the power and courage to win them” (page 127), there are hints of potential future troubles in competing with Percy’s art as shown through his “neglected” coffee cup, his sense of feeling left out of the bond between the friends, and the use of Baby as a nude model for their paintings. “Unnatural mother! Would you sacrifice your child on the altar of your insatiable art?” (page 124).

Not meant to know?

As we will never know the outcome of May Alcott Nieriker’s life due to her untimely death after childbirth, so we shall never know the outcome of Diana and Persis since Louisa would not take up the story again, prostrate with grief over May’s passing. If I didn’t know better, I would say we were not meant to know, the experiment being so progressive that it was too far ahead of its time.

Diana and Persis offers this scenario:

Diana succumbs and marries Stafford and becomes stepmother to Nino. She finds herself becoming a better sculptor despite the competition between married life and motherhood, and art, both of which require all she has to give.August proves in the end to be that progressive husband, equal to Percy and thus she continues to find acclaim as a painter.. . . . . . . . .

How Louisa May Alcott’s Feminism Explains her Timelessness

. . . . . . . . . .

Somehow though, I doubt Louisa would create such a “happily ever after” ending, realist as she was, as it would make for a dull read. She had sowed seeds of doubt with Percy and her family, setting the stage for future tension. Anyone who has combined a passion for art, writing or music with raising a family knows how the two passions hotly compete. There is constant warring between the two and plenty of guilt to go along with it.

I get the sense that Diana would have eventually married Stafford but it would have taken a long time for her to accept that she could pursue her art within a happy domestic setting. Stafford delights in Diana’s talent and without pontificating, as August, did, he praises her bold statue of “Saul” (“There is virile force in this, accuracy as well as passion – in short, genius.” – page 103) while reveling in the beautiful and tender likeness of his son in her statue of “Puck.”

Grief and art

Two small parts of this story stood out for me, once again revealing the authenticity of Louisa’s writing. A statement by Stafford, who had lost his beloved wife, reveals the effects of grief upon art:

“… the power has gone out of me. My friend, may you never know the awful weariness that comes when the golden apples once has struggled for turn to ashes on the lips.” (page 105)

Having experienced this twice with the deaths of my parents, I know from whence he speaks. Music was my passion at the time; it took two years and much hard work to regain my art once my father passed. When my mother entered hospice, I prayed to God asking him not to resurrect the music if it should die within me. He honored that prayer, giving me time to mourn before slowly restoring it. And in the meantime, of course, I was led to write.

I believe that Louisa, understanding the creative, transforming force of grief, would have restored Stafford’s genius through his relationship with Diana. What a wonderful story of redemption and resurrection that would have been!

A modern story

Percy’s story would have so resonated with today’s women who are keenly aware of the struggles of juggling family and career. The competition is keen yet I have to say that although my art was delayed many years due to family responsibilities, I do believe it is better for having gone through the undertaking.

One of longing

Finally, this book is filled with the craving Louisa had to live the dedicated life of an artist without all of her family obligations. Tethered by her own sense of duty and hampered by her poor health, the best she could do was to support the sister who could live the dream, and retreat to her imagination in the story of Diana and Persis.

Diana and Persis has all the promise of Little Women with its honesty, heart and keen insight. How unfortunate for all of us that it was not completed. But how lucky too, that the manuscript was discovered and published.

Where to find Diana and Persis

You can find Diana and Persis in these forms: Sarah Elbert’s version which I highly recommend because of her opening essay, and also in Alternative Alcott, edited by Elaine Showalter.

Further reading

For further reading check out Anne E. Boyd’s book, Writing for Immortality, pages. 109–117, for an analysis of Diana and Persis. For one thing, Boyd reveals yet another unpublished manuscript at Houghton, this one by May herself called An Artist’s Holiday. You can find out more information about that manuscript here.

Originally published on Louisa May Alcott is My Passion. Reprinted by permission.

. . . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Diana and Persis — Louisa May Alcott’s Unfinished Novel appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Books about Bookshops, Libraries, & Reading for True Bibliophiles

For bibliophiles, it’s not enough to be so obsessed with books that we’re reading four or five works of fiction or nonfiction at any given time. We also love books about bookshops, libraries, and even books about books and reading! This might seem eccentric at first glance, but for the devout book lover, it makes perfect sense.

Here’s a slew of books for book lovers that celebrate the passion for the page. At left, Bibliophile: An Illustrated History by Jane Mount, which kicks off this list.

In this list you’ll find a book about so-called “book towns” around the world; a celebration of libraries; a musing on the art of reading itself; a collection on the thrill of finding rare books; a few books on bookshops, and a book on the joy of bibliomania. What perfect gifts these make for the book nerds in your life — or for yourself, if you fit that description!

Nonfiction

. . . . . . . . . .

Bibliophile: An Illustrated History by Jane Mount

Bibliophile on Bookshop.org*

Bibliophile on Amazon*

A love letter to all things bookish, book people and places are curated by Jane Mount, who illuminates them with the vibrant illustrations she’s known for.

You’ll find literary trivia, see the world’s beautiful bookstores, workplaces of famous authors, and even get a taste of famous fictional meals. Best of all, it’s a wonderful resource for discovering some of the greatest reads ever.

“In this love letter to all things bookish, Jane Mount brings literary people, places, and things to life through her signature and vibrant illustrations … A source of endless inspiration, literary facts and recommendations, Bibliophile is pure bookish joy.”

. . . . . . . . . .

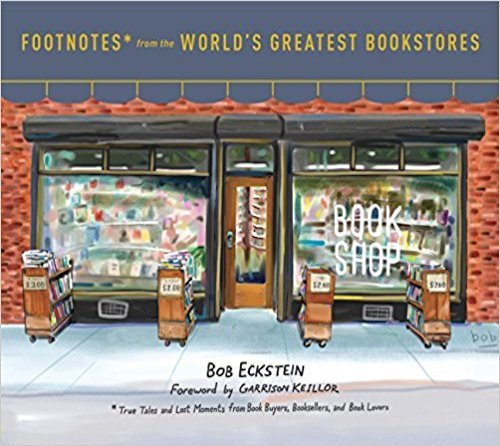

Footnotes from the World’s Greatest Bookstores:True Tales and Lost Moments from Book Buyers, Booksellers,

and Book Lovers by Bob Eckstein

Footnotes from the World’s Greatest Bookstores on Bookshop.org*

Footnotes from the World’s Greatest Bookstores on Amazon*

From New Yorker cartoonist Bob Eckstein, here’s a collection of 75 gorgeous detailed paintings of some of the world’s most iconic bookstores, served up with the inside scoop about what goes on inside them. Quirky and charming, the anecdotes and stories feature many of today’s most renowned authors and thinkers.Some of these bookstores have gone by the wayside, many, thankfully, are still open for business.

“Page by page, Eckstein perfectly captures our lifelong love affair with books, bookstores, and book-sellers that is at once heartfelt, bittersweet, and cheerfully confessional.” Read an excerpt from this book on this site.

. . . . . . . . . .

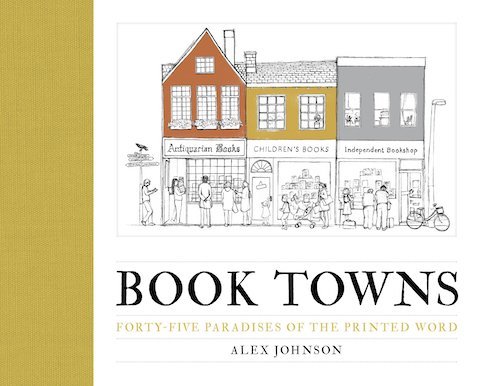

Book Towns: Forty Five Paradisesof the Printed Word by Alex Johnson

Book Towns on Bookshop.org*

Book Towns on Amazon*

“Book Towns” of the world are hamlets, villages, and towns center on literature and bookshops — in other words, paradises for book lovers.

Book Towns will take you on a tour of the recognized literary towns around the world, with stories of how they grew and offering information on how to get there. But even if you never get to any of them, the beautiful photos and charming stories are perfect for the book-loving armchair traveler.

“Amid the beauty of the Norwegian fjords, among the verdant green valleys of Wales, in the shadow of the Catskill mountains and beyond, publishers and printmakers have banded together to form unique havens of literature.” Read more about Book Towns on this site.

. . . . . . . . . .

I’d Rather Be Reading: The Delights and Dilemmasof the Reading Life by Anne Bogel

I’d Rather be Reading on Bookshop.org*

I’d Rather Be Reading

on Amazon*

I’d Rather Be Reading is a collection of witty reflection that any voracious reader will relate to. Blogger and author Anne Bogel (known for her popular podcast What Should I Read Next?) invites book lovers into a virtual community that’s as cozy as it is fascinating.

“With fascinating new things about books and publishing, and reflect on the role reading plays in their lives. The perfect gift for the bibliophile in everyone’s life, I’d Rather Be Reading will command an honored place on the overstuffed bookshelves of any book lover.”

. . . . . . . . . .

I’d Rather be Reading: A Library of Art for Book Loversby Guinevere de la Mare

I’d Rather Be Reading on Bookshop.org*

I’d Rather be Reading on Amazon*

Echoing the title of the previous entry, this gifty book is more visually oriented. From the publisher: For anyone who’d rather be reading than doing just about anything else, this book is the ultimate must-have. In this visual ode to all things bookish, readers will get lost in page after page of beautiful contemporary art, photography, and illustrations depicting the pleasures of books.

Artwork from the likes of Jane Mount, Lisa Congdon, Julia Rothman, and Sophie Blackall is interwoven with text from essayist Maura Kelly, bestselling author Gretchen Rubin, and award-winning author and independent bookstore owner Ann Patchett.

A pocket-sized book of less than 100 pages, it’s rounded out with poems, quotations, and aphorisms celebrating the joys of reading, this lovingly curated compendium is a love letter to all things literary, and the perfect gift for bookworms everywhere.

. . . . . . . . . .

Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic Findsin Unlikely Places by Rebecca Rego Barry

Rare Books Uncovered on Bookshop.org*

Rare Books Uncovered on Amazon*

From the publisher: Feed your inner bibliophile with this volume on unearthed rare and antiquarian books. Few collectors are as passionate or as dogged in the pursuit of their quarry as collectors of rare books. In Rare Books Uncovered, expert on rare and antiquarian books Rebecca Rego Barry recounts the stories of remarkable discoveries from the world of book collecting.

Read about the family whose discovery in their attic of a copy of Action Comics No. 1— the first appearance of Superman — saved their home from foreclosure. Or the Salt Lake City bookseller who volunteered for a local fundraiser — and came across a 500-year-old copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle.

Or the collector who, while browsing his local thrift shop, found a collectible copy of Calvary in China — inscribed by the author to the collector’s grandfather. These tales and many others will entertain and inspire casual collectors and hardcore bibliomaniacs alike.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Bookshop Book by Jen Campbell

The Bookshop Book on Bookshop.org*

The Bookshop Book on Amazon*

From the publisher: Here’s a book in which the bookshop, even more than the book itself, is the center of curiosity and fascination. Here you’ll find more than 300 weird and wonderful bookstores around the world, in every form imaginable: shops on buses, in converted churches, abandoned factories, on barges, and even odder places.

You’ll encounter stories of bookshops that moveable, mutable, and that are even folded into vending machines. “From the oldest bookshop in the world, to the smallest you could imagine … The Bookshop Book is a love letter to bookshops all around the world.” From the bestselling author of Weird Things Customers Say in Bookshops.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Diary of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell

The Diary of a Bookseller on Bookshop.org*

The Diary of a Bookseller on Amazon*

You wouldn’t think that the journals of a bookseller would be so comedic, but The Diary of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell is laugh-out-loud-funny. The owner of a used bookstore, appropriately called The Book Shop, Shaun’s story takes place in Wigtown, Scotland.

This rural town was the first of the forty-some odd “Book Towns” compiled into the book of the same name, above. Bythell dishes on how he buys books, how he makes his old-fashioned business thrive in the modern world, and more. The heart of the book is his the hilarious interactions with staff and customers, adding up to an entertaining romp for book nerds. Shaun Bythell is also the author of Seven Kinds of People You Find in Bookshops.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders by Stuart Kells

The Library on Bookshop.org*

The Library on Amazon*

From the publisher: Ancient libraries, grand baroque libraries, scientific libraries, memorial libraries, personal libraries, clandestine libraries: Stuart Kells tells the stories of their creators, their prizes, their secrets, and their fate.

To research this book, Kells traveled around the world with his young family like modern-day ‘Library Tourists.’” So states the description of this book that will surely thrill devoted library lovers.

The Library is a celebration of libraries as places of wonder, and of the physical book as a thing of beauty. And it explores the human element, the very thing that has made libraries enduring institutions in a rapidly changing world. By the author of Shakespeare’s Library: Unlocking the Greatest Mystery in Literature.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Library Book by Susan Orlean

The Library Book on Bookshop.org*

The Library Book on Amazon*

Susan Orlean has created a wondrous love letter to libraries. From Amazon: “Weaving her lifelong love of books and reading into an investigation of the fire, award-winning New Yorker reporter and New York Times bestselling author Susan Orlean delivers a mesmerizing and uniquely compelling book that manages to tell the broader story of libraries and librarians in a way that has never been done before …

Brimming with her signature wit, insight, compassion, and talent for deep research, The Library Book is Susan Orlean’s thrilling journey through the stacks that reveals how these beloved institutions provide much more than just books—and why they remain an essential part of the heart, mind, and soul of our country. It is also a master journalist’s reminder that, perhaps especially in the digital era, they are more necessary than ever.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Card Catalog: Books, Cards, and Literary Treasuresby The Library of Congress

The Card Catalog on Bookshop.org*

The Card Catalog on Amazon*

From the publisher: The Library of Congress brings book lovers an enriching tribute to the power of the written word and to the history of our most beloved books. Featuring more than 200 full-color images of original catalog cards, first edition book covers, and photographs from the library’s magnificent archives, this collection is a visual celebration of the rarely seen treasures in one of the world’s most famous libraries and the brilliant catalog system that has kept it organized for hundreds of years.

Packed with engaging facts on literary classics — from Ulysses to The Cat in the Hat to Shakespeare’s First Folio to The Catcher in the Rye — this package is an ode to the enduring magic and importance of books.

. . . . . . . . .

Dear Fahrenheit 451: Love and Heartbreak in the Stacksby Annie Spence

Dear Fahrenheit 451 on Bookshop.org*

Dear Fahrenheit 451 on Amazon*

From the publisher: A librarian’s laugh-out-loud funny, deeply moving collection of love letters and breakup notes to the books in her life. If you love to read … you know that some books affect you so profoundly they forever change the way you think about the world. Some books, on the other hand, disappoint you so much you want to throw them against the wall. Either way, it’s clear that a book can be your new soul mate or the bad relationship you need to end.

In Dear Fahrenheit 451, librarian Annie Spence has crafted love letters and breakup notes to the iconic and eclectic books she has encountered over the years. From breaking up with The Giving Tree (a dysfunctional relationship book if ever there was one), to her love letter to The Time Traveler’s Wife (a novel less about time travel and more about the life of a marriage, with all of its ups and downs), Spence will make you think of old favorites in a new way.

Filled with suggested reading lists, Spence’s take on classic and contemporary books is very much like the best of literature―sometimes laugh-out-loud funny, sometimes surprisingly poignant, and filled with universal truths.

. . . . . . . . . .

Reading Behind Bars: A True Story of Literature, Law,and Life as a Prison Librarian by Jill Grunewald

Reading Behind Bars on Bookshop.org*

Reading behind Bars on Amazon*

From the publisher: In December 2008, twenty-something Jill Grunenwald graduated with her Master’s degree in library science, ready to start living her dream of becoming a librarian. But the economy had a different idea. As the Great Recession reared its ugly head, jobs were scarce. After some searching, Jill was lucky enough to snag one of the few librarian gigs left in her home state of Ohio. The catch? The job was behind bars as the prison librarian at a men’s minimum-security prison.

… Over the course of a little less than two years, Jill came to see past the bleak surroundings and the orange jumpsuits and recognize the humanity of the men stuck behind bars. They were just like every other library patron—persons who simply wanted to read, to be educated and entertained through the written word. Jill simultaneously began to recognize the humanity in everyone and to discover inner strength that she never knew she had. At turns poignant and hilarious, Reading behind Bars is a perfect read for fans of Orange is the New Black and Shakespeare Saved My Life.

Children’s books

. . . . . . . . . .

Schomberg: The Man Who Built a Libraryby Carole Boston Weatherford

Schomberg on Bookshop.org*

Schomberg on Amazon*

Though this book is meant for grades 3 to 6 (illustrated by Eric Velasquez), it can really be enjoyed by “children of all ages,” and is a wonderful way to learn about an amazing, under-appreciated personage in American literary history.

From the publisher: In luminous paintings and arresting poems, two of children’s literature’s top African-American scholars track Arturo Schomburg’s quest to correct history.

Where is our historian to give us our side? Arturo asked. Amid the scholars, poets, authors, and artists of the Harlem Renaissance stood an Afro–Puerto Rican named Arturo Schomburg. This law clerk’s life’s passion was to collect books, letters, music, and art from Africa and the African diaspora and bring to light the achievements of people of African descent through the ages … A century later, his groundbreaking collection, known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, has become a beacon to scholars all over the world.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Book Itch: Freedom, Truth & Harlem’s Greatest Bookstoreby Vaunda Micheaux Nelson

The Book Itch on Bookshop.org*

The Book Itch on Amazon.com*

From the publisher: In the 1930s, Lewis’s dad, Lewis Michaux Sr., had an itch he needed to scratch–a book itch. How to scratch it? He started a bookstore in Harlem and named it the National Memorial African Bookstore.

And as far as Lewis Michaux Jr. could tell, his father’s bookstore was one of a kind. People from all over came to visit the store, even famous people–Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, and Langston Hughes, to name a few. In his father’s bookstore people bought and read books, and they also learned from each other.

People swapped and traded ideas and talked about how things could change. Read the story of how Lewis Michaux Sr. and his bookstore fostered new ideas and helped people stand up for what they believed in.

Winner of the Coretta Scott King Illustrator Honor, ALA Notable Children’s Book, Jane Addams Children’s Book Award, Kirkus Best Children’s Books, & other awards. It’s picture book (illustrated by R. Gregory Christie) for grades 1 to 4, though like the book above about Arturo Schomberg, it can be enjoyed by all ages.

Novels. . . . . . . . . .

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald

The Bookshop on Bookshop.org*

The Bookshop on Amazon*

Set in 1959, Florence Green, a kindhearted widow with a small inheritance, risks everything to open a bookshop—the only bookshop—in the seaside town of Hardborough. By making a success of a business so impractical, she invites the hostility of the town’s less prosperous shopkeepers.

By daring to enlarge her neighbors’ lives, she crosses Mrs. Gamart, the local arts doyenne. Florence’s warehouse leaks, her cellar seeps, and the shop is apparently haunted. Only too late does she begin to suspect the truth: a town that lacks a bookshop isn’t always a town that wants one.

The Bookshop, published in 2015, was adapted to film in 2018, to mixed reviews by audiences and critics. Devotees of media about bookstores should nevertheless get some enjoyment from it.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Last Bookshop in London: A Novel of World War IIby Madeline Martin

The Last Bookshop in London on Bookshop.org*

The Last Bookshop in London on Amazon*

From the publisher: August 1939: London prepares for war as enemy forces sweep across Europe. Grace Bennett has always dreamed of moving to the city, but the bunkers and drawn curtains that she finds on her arrival are not what she expected. And she certainly never imagined she’d wind up working at Primrose Hill, a dusty old bookshop nestled in the heart of London.

Through blackouts and air raids as the Blitz intensifies, Grace discovers the power of storytelling to unite her community in ways she never dreamed—a force that triumphs over even the darkest nights of the war.

This 2021 publication has become a bestseller and a reader favorite.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Little Paris Bookshop by Nina George

The Little Paris Bookshop on Bookshop.org*

The Little Paris Bookshop on Amazon*

From the publisher: “Monsieur Perdu calls himself a literary apothecary. From his floating bookstore in a barge on the Seine, he prescribes novels for the hardships of life. Using his intuitive feel for the exact book a reader needs, Perdu mends broken hearts and souls. The only person he can’t seem to heal through literature is himself; he’s still haunted by heartbreak after his great love disappeared. She left him with only a letter, which he has never opened.

After Perdu is finally tempted to read the letter, he hauls anchor and departs on a mission to the south of France, hoping to make peace with his loss and discover the end of the story. Joined by a bestselling but blocked author and a lovelorn Italian chef, Perdu travels along the country’s rivers, dispensing his wisdom and his books, showing that the literary world can take the human soul on a journey to heal itself.”

Internationally bestselling and filled with warmth and adventure, The Little Paris Bookshop is a love letter to books, meant for anyone who believes in the power of stories to shape people’s lives.

. . . . . . . . .

The Bookshop on the Corner by Jenny Colgan

The Bookshop on the Corner on Bookshop.org*

The Bookshop on the Corner on Amazon*

From the publisher: Nina Redmond is a librarian with a gift for finding the perfect book for her readers. But can she write her own happy-ever-after? In this valentine to readers, librarians, and book-lovers the world over, the New York Times-bestselling author of Little Beach Street Bakery returns with a funny, moving new novel for fans of Nina George’s The Little Paris Bookshop.

Nina is a literary matchmaker. Pairing a reader with that perfect book is her passion… and also her job. Or at least it was. Until yesterday, she was a librarian in the hectic city. But now the job she loved is no more. Determined to make a new life for herself, Nina moves to a sleepy village many miles away. There she buys a van and transforms it into a bookmobile — a mobile bookshop that she drives from neighborhood to neighborhood, changing one life after another with the power of storytelling.

Nina discovers there’s plenty of adventure, magic, and soul in a place that’s beginning to feel like home… a place where she just might be able to write her own happy ending. The next book in this series is The Bookshop on the Shore.

. . . . . . . . .

*This post contains Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Books about Bookshops, Libraries, & Reading for True Bibliophiles appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 20, 2021

The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck: An Appreciation

Revisiting a book many years after the first reading and still being able to connect is one of the greatest joys of rediscovering great authors. It’s no surprise that Pearl S. Buck won the Pulitzer Prize for The Good Earth and also went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

This novel, published in 1931, was the first in her House of Earth trilogy, followed by Sons and A House Divided. It made it to the bestselling lists in the United States, both in 1931 and 1932. The author, as the daughter of missionaries, grew up in China and based this work of historical fiction on her personal observations of village life around her.

Possibly the most interesting consequence of the author’s sympathetic depiction of the protagonists, farmer Wang Lung and his wife O-Lan, was in helping Americans of that period to be accepting of the Chinese as allies against the rumblings of war against Japan. Perhaps even Buck couldn’t have anticipated the impact that her book had — and continued to have — on her fellow Americans.

A view of women & society that still resonates

For myself, as an Asian woman from a totally different time, the book almost seems uncanny in its similarity to India, in the way that it views women.

The notion of a woman as a possession, which seems an underlying theme of this book, is prevalent even in the India of today, more pronounced perhaps in the rural hinterlands and very much internalized in a patriarchal society.

The other marked commonality is the respect accorded to elders and the elevated position that they enjoy in a family, by virtue of their years and experience.

The abject poverty of this farming family has been grasped so well by the author that you are left wondering whether she has lived this life herself. From the scarcity of water for a bath to the limitations on food and drink and also the tattered clothes; everything is reflected so authentically.

Wang Lung’s marriage to O-lan

The story begins with the farmer Wang Lung’s marriage day and his preparations for the occasion. After fetching water for his father’s wash, which he has been doing for six years since his mother’s passing, he can look forward to a rest: “There was a woman coming to the house. Never again would Wang Lung have to rise summer and winter at dawn to light the fire.”

The contrast between poverty and wealth is a recurring theme of this novel as is Wang Lung’s obsession with his land and the desire to own more and more of it. The House of Hwang from where his father goes in search of a slave as a bride for his son, is held up in the early part of the novel as unattainable until good fortune comes into the life of Wang Lung, whilst things change for the House of Wang.

Wang Lung’s father’s decision to choose a bride who is not pretty is met with initial protests by the son. But he is silenced by his father’s logic, “And what will we do with a pretty woman? We must have a woman who will tend the house and bear children as she works in the fields, and will a pretty woman do these things?”

The tragic character in this novel is most certainly O-Lan, the bride that Wang Lung brings home. She is all that Wang Lung’s father had envisaged and much more. Self-effacing and efficient, this woman becomes someone the father and son begin to depend on and, later on, the children who are born to the couple. Even when she bears children, O-Lan handles everything herself in quiet isolation and is up and about the next day, tending to the house and going about her regular work.

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1931 review of The Good Earth

. . . . . . . . . .

The birth of a first-born son is a matter of great celebration and announcements are made with ceremonial fanfare. Like in many Asian cultures, the arrival of a son affords bragging rights in China, whilst the birth of daughters is no cause for celebration, with the daughters sometimes being referred to as slaves.

The fortunes of Wang Lung seem to turn around after the arrival of his wife and while he seems silently proud of her, never once does he openly voice his appreciation of her. Rather, in the latter part of the novel, he actually develops an aversion to her plainness, and what he now perceives as coarseness. With his newly acquired wealth, the farmer now involves himself in a dalliance with a prostitute and later brings her home as his second wife.

One wonders whether the author had intended to keep an aura of mystery about O-Lan or is it the prototype of a Chinese village woman that she has tried to replicate? Rarely is there a personal glimpse into the life that O-Lan lived in the House of Hwang as a slave. The only time that she shows desire is when she asks to keep two tiny pearls from a pile of jewelry that she has kept hidden on her person after retrieving the same from a rich man’s house.

“Then Wang Lung, without comprehending it, looked for an instant into the heart of this dull and faithful creature, who had labored all her life at some task at which she won no reward…”

Besides this, O-Lan only shows resentment in small ways when the second wife comes to live with the rest of the family, but does not express anything in words.

Glimpses of the House of Hwang

Buck, being the great author that she is, keeps the see-saw going with regard to deprivation, then prosperity, and again hardship, followed again by great wealth. Being the daughter of missionaries, one cannot help wonder whether there is an internalization of the dangers of too much wealth, which the reader is given glimpses of, in the dissipated lives of the denizens of the House of Hwang.

History seems to repeat itself in the House of Wang, as the farmer becomes a wealthy man and the sons used to the good life, no longer have a connection with the land, except for the wealth that can be extracted from it. The end is poignant when Wang Lung, old and helpless, tells his sons, “If you sell the land, it is the end” and they reply, “Rest assured, father …The land is not to be sold,” as they look over his head and smile at each other.

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

. . . . . . . .

The Good Earth on Bookshop.org*

The Good Earth on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck: An Appreciation appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 18, 2021

That is the New Rhythm: Mina Loy and Marianne Moore

A reflection on the period in which Mina Loy and Marianne Moore, modernist poets (among other talents) crossed paths in the early 1920s. Excerpted from Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

The poetry of Mina Loy was often compared and sometimes published next to that of the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap put them together in the issue of Little Review that immediately followed their obscenity conviction for printing Ulysses, some time around 1920.

Man Ray took photographs of both of them specially; opposites in looks but potential sisters in their view of female sexuality. And the only issue of the magazine New York Dada had both an article mocking Loy’s relationship with Cravan and a portrait of the Baroness, this time wearing only her jewelry, as the “naked truth” of Dada.

A confluence of poets

Loy was also often compared to Ezra Pound; she wrote a paper called “Modern Poetry,” in which she talks about the relationship of poetry to music. In it she says that only one poet has really ever made “the logical transition from verse to music” — Pound.

To speak of the modern movement is to speak of him; the masterly impresario of modern poets, for without the discoveries he made with his poet’s instinct for poetry, this modern movement would still be rather a nebula than the constellation it has become.

Like William Carlos Williams, Loy believed that it was “inevitable that the renaissance of poetry should proceed out of America, where latterly a thousand languages have been born, and each one, for purposes of communication at least, English.” Loy is not interested in the past, only in the future, and one of the most futuristic poets for her is e.e. cummings; where “other poets have failed for being too modern he is more modern still, and altogether successful.”

She does admire some poets from what she calls the past though, including H.D. and Marianne Moore “whose writing so often amusingly suggests the soliloquies of a library clock.” This is not necessarily praise from such a freethinking and passionate woman – the words “library” and “clock” suggest the aloof austerity of which H.D. was in awe; Moore was in fact a librarian.

Even though she was at Bryn Mawr and knew them all, Marianne Moore was never close to Ezra, Bill, or Hilda throughout her life; she was never part of any movement or any set, and in both her life and her poetry she was quite reserved and austere. Moore lived in a tiny apartment with her mother, who was gay, sharing a bed until her mother’s death.

In awe of Marianne Moore

Both men and women were attracted to Moore but she seems to have had no real relationships with either sex. H.D. seems to have been rather in awe of Moore. As late as October 28, 1934, HD wrote to Bryher:

“I have had my first real fan letter from a woman – Marianne – of all people – write this in letter of gold – And I hope you will never doubt from such worms as myself the admiration which the shining face of your courage evokes! … I am positively limp!!!! I was terrified of M.M.”

William Carlos Williams was also slightly in awe of Moore.

“She had a head of the most glorious auburn hair and eyes – I don’t even know to this day whether they were blue or green – but these features were about her only claim to physical beauty. We all loved and not a little feared her not only because of her keen wit but for her skill as a writer of poems. She had a unique style of her own; none of us wanted to copy it but we admired it.”

In Moore’s only published reference to Loy she talks about Loy’s “sliced and cylindrical, complicated yet simple use of words.” Again, not exactly pure praise. Around 1920, many people were comparing Loy and Moore. Ezra Pound bracketed them together, calling their style logopoeia, the poetry of ideas. This wasn’t praise either; at the time he was promoting Imagism, the poetry of things, in the work of H.D. and Amy Lowell. Pound said that Loy and Moore didn’t use arresting images or noble sentiments, their work was just “a dance of the intelligence among words and ideas … A mind cry, more than a heart cry.”

. . . . . . . . . .

[image error]

Everybody I Can Think of Ever on Amazon U.S.*

Everybody I Can Think of Ever on Amazon U.K*

. . . . . . . . . .

T.S. Eliot, in The Egoist, ranked Moore higher than Loy in his personal pantheon but Pound quickly replied saying that some of Mina’s lines were “perhaps better than anything I have found in Miss Moore.” In practice, Pound championed and supported them both.

In a very long letter of April 22, 1921 to Anderson and Heap, soon after they had been fined $50 each for publishing sections of Ulysses and barred from publishing any more, Pound lists his suggested contributors for the next issue; referring to Mina and Marianne only by their first names.

Cocteau ourselves illustrations of work by Picabia

W. c. Williams Brancusi etc. Cendrars

Marianne Picasso Cros

Mina Lewis Morand

Crossing paths

The two women first met in 1916 when Marianne saw Mina playing the wife opposite William Carlos Williams at the Provincetown Players. They met again in 1920, when McAlmon took Loy to the apartment at St Luke’s Place in Greenwich Village where Marianne the librarian lived with her mother, as if playing to her image as a timid spinster.

In McAlmon’s fictional version, Loy says that her life must be the result of “some suppression or cowardice.” But Marianne is very welcoming and tells Mina she has wanted to talk about her poetry, saying that her job keeps her from writing. Mina says to her: “you observe things too uniquely to let any paid job interfere, though I presume you believe in self-discipline and duty more than some of us.”

Williams knew both Moore and Loy, and recorded a dinner where both women were there so everyone could compare them – their physical appearance if not their poetry.

“Marianne Moore, like a rafter holding up the superstructure of our uncompleted building, a caryatid, her red hair plaited and wound twice about the fine skull, though she was surely one of the main supports of the new order, was no luckier than the rest of us. One night (Mina Loy was there also) we all met at some Dutch-treat party in a cheap restaurant on West Fifteenth Street or thereabouts.

There must have been twenty of us. Marianne, with her sidelong laugh and shake of the head, quite childlike and overt, was in awed admiration of Mina’s long-legged charms. Such things were in our best tradition. Marianne was our saint – if we had one – in whom we all instinctively felt our purpose come together to form a stream. Everyone loved her.”

That is the new rhythm

In her article “Modern Poetry,” Loy singles out Williams for special praise as one of the few writers who embodies her idea of a bridge between the past and the future.

“Williams brings me to a distinction that it is necessary to make in speaking of modern poets. Those I have spoken of are poets according to the old as well as the new reckoning; there are others who are poets only according to the new reckoning. They are headed by Dr. Carlos Williams. Here is the poet whose expression derives from life. He is a doctor. He loves bare facts. He is also a poet, he must recreate everything to suit himself. How can he reconcile these two selves?

Williams will make a poem of a bare fact – just show you something you noticed. The doctor wishes you to know just how uncompromisingly itself that fact is. But the poet would like you to realisze all that it means to him, and he throws that bare fact onto paper in such a way that it becomes part of Williams’ own nature as well as the thing itself. That is the new rhythm.”

. . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

Mina Loy and “The Crowd”: Modernists in 1920s Paris

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post That is the New Rhythm: Mina Loy and Marianne Moore appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Mina Loy, Modernist Poet, Playwright, and Artist

Mina Loy (December 27, 1882 – September 25, 1966) was a brilliant English-born poet, playwright, and artist. Light years ahead of her time, she was lauded by her peers for her dense analyses of the female experience in early twentieth-century Western society.

She was associated with other great minds and literary innovators of her time, like T.S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, Sylvia Beach, Sinclair Lewis, Ezra Pound, and others.

BackgroundLoy was born Mina Gertrude Löwy in London, England, the eldest daughter of Sigmund and Julia Bryan Löwy. Löwy’s father was a Jewish-Hungarian immigrant.

Mina was granted an unconventionally thorough education for a young lady of a wealthy middle-class family, traveling to Europe to study in the great art capitals of the Continent.

Unhappy marriages and a peripatetic life

At twenty-one, Loy married fellow artist Hugh “Stephen” Oscar William Haweis. They settled in Paris among the bustling modernist art salons, where they mingled with the likes of Guillaume Apollinaire, and Picasso, as well as Leo and Gertrude Stein.

Loy and Haweis had three children. Their eldest, Oda Janet, died in infancy. The bereaved family relocated to Florence, Italy, where Loy gave birth to two more children, Joella and Giles. Loy began to suffer from frequent ailments and mental illness, but continued to pursue and exhibit her art in both Italy and her native England.

As a young child, Joella was unwell, leading to Loy’s pursuit of Christian Science. Her marriage to Haweis was never a happy one, and in 1913, he abandoned his family to travel to the South Seas. The couple finally divorced several years later. Loy spent these years as a recluse among the expatriate community in Florence, a sad and beautiful young woman — unprepared for motherhood, overwhelmed by her illnesses and Joella’s.

Despite her own afflictions, Loy worked as a nurse during World War I but soon abandoned the Continent for the United States. In October 1916, she left her children in the care of a nurse, intending to retrieve them soon, and sailed for New York City.

While in New York, Loy fell in love with early Dadaist and surrealist, Arthur Cravan. In January 1918, they married in Mexico City, then returned to Europe to reunite with Loy’s children and make a home in Paris. Loy went ahead, planning to reunite with Cravan in Buenos Aires, Argentina, but he never arrived.

Loy diverted her travels to London, where she gave birth to their daughter, Jemima Fabienne. Cravan’s disappearance devastated Loy, and she would continue to mourn him in her writings. In 1921, Loy’s ex-husband abducted their son Giles from Florence. The child died only two years later.

She settled again in Paris, this time with her daughters, and together they ran a business where she designed and sold lampshades.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Becoming a poetThough Loy began her art career with painting, her creative fire propelled her expansion into other forms of artistic expression. Her introduction to Italian futurists, Carlo Carrà, F.T. Martinetti, and Giovanni Papini among them, was a primary inspiration to her poetry.

Although she espoused the futurists’ teachings on how to use one’s “vitality,” Loy remained skeptical of their machismo and quickly turned to satirize them in pamphlets, poems, and plays like “The Sacred Prostitute,” Psycho-Democracy, and “Lions’ Jaws.”

In New York City, Loy was recognized as the epitome of the avant-garde woman. She was a forerunner of the movement to modernize poetry inspired by futurism, cubism, and surrealism. Immediately after her arrival in the States, Loy acted in Kreymborg’s play, Lima Beans.

Loy was too radical for the more mainstream poetry journals of her day but found a home for her work in journals such as Others, Camera Work, and Rogue. After Marcel Duchamp’s definitive Dadaist sculpture was rejected by the New York Independents Exhibit, Duchamp, Loy, and others collaborated on a journal of their own, called Blind Man.

Feminist Manifesto

Feminist Manifesto, which is now considered Loy’s greatest work, wasn’t published until decades after her death. In this 1914 piece, Loy struggles modernism, the artistic philosophy of her day, and its central aesthetic of impersonality.

Loy believed women needed to assert their own special brand of selfhood because they had so long been relegated to “impersonality” by subsuming their own personalities in those of men.

. . . . . . . . . .

Mina Loy was central to a group of creatives known as “The Crowd”

. . . . . . . . . .

Loy was as much noted for her visual art as for her writing. She was promoted by the noted art dealer Peggy Guggenheim, who wrote,

“Mina Loy, who was not only a poetess and a painter, was always inventing something new by which she hoped to make a fortune. She had just created a new, or old, form of papier collé – flower cut-outs which she framed in beautiful old Louis Philippe frames she bought in the flea market. She asked me to take these to New York for her and sell them.”

Peggy exhibited Loy’s work in her Madison Avenue gallery, with great success. Later, back in Paris, Mina and Peggy went into business together, opening a lampshade shop.

Controversy and legacy

Mina Loy’s shockingly open handling of sexuality scandalized more conservative readers and her cerebral, abstract style alienated and confused many, but her supporters praised her “dance of the intelligence among words and ideas” and her innate artistry, saying, “Yes, poetry is in this lady whether she writes or not.”

Loy sought to combine feminism and futurism, often to unsettling ends, as when she asserted that intelligent women ought to produce children as part of her “race-responsibility.” She railed against the ideal of virginity and how it constrained women to narrowly defined roles set for them by men.

Her unabashed honesty and demands that her readers face their own truth, never shrinking to hide in delusion, capture the terrible beauty of life’s constant change. Her short lines and not-quite-free verse style reflected the deep emotion and deep thought saturating her poetry. Her bounding from imagery to calculated analysis irked some of her fellow artists but was an intentional artistic reflection of the chaos of the physical world and our own inner processes.

. . . . . . . . .

Mina Loy page on Amazon*

More about Mina LoyOn this site

Mina Loy and “The Crowd” — Modernists in 1920s Paris That is the New Rhythm: Mina Loy and Marianne MoorePoetry

Lunar Baedeker (1923)Lunar Baedeker and Time-Tables (1958)The Last Lunar Baedeker, Roger Conover, ed. (1982)The Lost Lunar Baedeker, Roger Conover, ed. (1997)Prose

Insel, Elizabeth Arnold ed. (1991)Stories and Essays, Sara Crangle, ed. (2011)More information

Modern American Poetry Poetry Foundation Modernism Lab at Yale University WikipediaRead online

Mina Loy at Electronic Poetry Center Works by or about Mina Loy at HathiTrustWorks by or about Mina Loy at Internet Archive. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Mina Loy, Modernist Poet, Playwright, and Artist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 14, 2021

The Road Through the Wall by Shirley Jackson: An Analysis

This analysis of The Road Through the Wall focuses on its young heroine, Harriet Merriam and is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

The Road Through the Wall was Shirley Jackson’s first novel, published in 1948. That was also the year when her short story, “The Lottery,” was published, making her instantly famous (as well as infamous).

Jackson claimed that the novel was loosely based on her childhood growing up in a well-to-do neighborhood in California. Admitting that this book was somewhat of a revenge novel, she asserted that a first novel’s purpose, after all, was to get back one’s parents.

Two original reviews

Saturday Review, February 28, 1948 wrote that “the story is a good one, set down with neither hope nor despair. It is the story of Sidestreet, USA, where the children reflect the life of their parents with its bickering futility and its moral bankruptcy.”

The Montreal Gazette (May 28, 1948) wrote: “Miss Jackson is no Sinclair Lewis; she is only 28. But she does in her most recent work show a remarkable talent for putting on paper the everyday happenings which at times make life a pleasure and sometimes make it pretty grim.”

Introducing Harriet Merriam

As in several of Jackson’s stories and novels, we do indeed see the world – and in this case Pepper Street is its own world – largely through children and their mothers; Jackson didn’t – possibly couldn’t – ever write a sympathetic male character.

Fourteen-year-old Harriet lives in a middle-class suburb in California – not completely unlike the one where Jackson herself was born – where everyone knows everyone else’s business. This a chamber piece where many characters have an equal part and Harriet is simply one of the actors in the drama. Nevertheless, she is drawn in great detail and the novel does show her awkwardly coming of age, at least in one sense.

Like many fictional teen heroines, Harriet wants to be a writer. She considers herself dumpy, unattractive and awkward; Jackson herself was consistently overweight – at the age of forty she weighed over 200 pounds – and by no means conventionally beautiful or glamorous even in her publicity photos; she creates Harriet with obvious love and a great deal of empathy.

“Harriet was a big girl, large-boned and stout, and Mrs. Merriam braided Harriet’s hair every morning and dressed her in bright colors. For the last year or so, from twelve to almost fourteen, Harriet had begun to speak awkwardly when she was uneasy, missing her words sometimes, and stammering.”

Trouble with Mother

Her mother confides to a friend that she worries about Harriet, “about her being so heavy, I mean. It’s very hard on a girl.” Harriet does not join in with the other children playing “baseball or tag or hide-and-seek, actually because she was fat and the other children made fun of her, ostensibly because her mother had forbidden her to play.’ She tells her friends that she has ‘a sort of weak heart… My mother thinks and the doctor thinks I shouldn’t do much running around like the other kids.” Jackson herself died of a heart attack in her forties.

Harriet’s trouble with her mother starts when, following other girls in her class, she writes a letter to a boy which only the most prudish of mothers, even in the 1940s, would consider risqué. Unfortunately for Harriet, her mother is one of those mothers. Harriet has chosen to write to George “because he was dull and unpopular and she felt vaguely that she had no right to aim any higher than the one boy no one else would have.”

Harriet had not sent the letter, nor even finished it. It begins, “Dearest George,” and continues, “Let’s run away and get married. I love you and I want to – “ The letter ends here because “Harriet had not been able to think of what she wanted to do with George.” Her friend Helen’s letter had ended “kiss you a thousand times’ but Harriet ‘could not bring herself to write such a thing, at least partly because the thought of kissing George Martin’s doll face horrified her.”

Harriet sees that her mother has been looking through her desk drawers, a private world which contains her notebooks labelled, respectively, Poems, Moods, Me and Daydreams. The mothers of the various girls are appalled to various degrees at this wanton, lustful collective display on the part of their daughters. Harriet’s mother is distraught.

“I try to make my daughter into a good decent girl in spite of –“ Mrs Merriam sobbed, “– in spite of everything, and I work all day and I worry about money and try to make a good decent home for my husband and now my only daughter turns out to be –“

“Josephine,” Mr Merriam said strongly. “Harriet, go upstairs again.”

Harriet went upstairs away from her mother’s sorry voice. Her desk was unlocked; instead of eating dinner, she and her mother had stood religiously by the furnace and put Harriet’s diaries and letters and notebooks into the fire one by one, while solid Harry Merriam sat eating lamb chops and boiled potatoes upstairs alone.

. . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

Harriet’s mother soon comes down and “Harriet felt at last like crying. She loved her mother again, as one should love a mother, tenderly and affectionately. She put her arm around her mother and kissed her. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said.”

Her mother says to Harriet: “We’ll spend more time together from now on. Reading, and sewing. Would you like to learn to cook, really cook?” She even offers to help Harriet write her poetry. “I used to write poetry, Harriet, not very well, of course, but that’s probably where you get it.”

Her father insists that she shows her mother everything she writes; Harriet, earnestly, says she will. Unusually for the characters in Girls in Bloom, Harriet’s father is not at all close to his daughter and has no idea what is going on in her life. Unlike Natalie Waite’s father in Jackson’s Hangsaman, he has no interest in literature or his daughter’s interest in it.

Real-life and literary friends

Harriet’s friend Virginia very nearly leads her into serious trouble when she takes Harriet with her to the apartment of a Chinese man she has met on the street. Harriet has been nervous of doing anything her mother would not approve of and wants to go the long way home so they will not run into him but Virginia tells her, “if you’re going to be scared all the time and always be wanting to go around the other way and afraid of your mother and everything I’ll just go on down to the store by myself and not talk to you anymore.”

Harriet doesn’t know what to do, she doesn’t want to go into the apartment but “she couldn’t let Virginia go alone, and never be friends again afterward, but once inside they were no longer right where they could call for help.” She tries to stop Virginia. “We can’t go in, Ginnie. My mother.” The girls do go inside but nothing bad happens, except that they discover the Chinese man is simply a servant in the apartment and the owners are away.

Afterwards she is nervous that Virginia will let slip something to her mother and is hoping that the family moving into the vacant house on the street may provide a new friend for her to replace the risky Virginia. Harriet quite naturally sees the world in terms of Little Women, though unusually, she does not want to be Jo.

Perhaps one of the new girls who would live in the house – they would be like in Little Women, and Harriet’s friend would be Jo (or just possibly Beth, and they could die together, patiently) – would love and esteem Harriet, and some day their friendship would be a literary legend, and their letters –

“‘Listen, she said in an honest voice, ‘I wanted to talk to you for a long time.’

‘What about?’ Harriet said.

Marilyn put her chin on her hands and stared straight ahead. ‘Just about everything,’ she said. ‘You like to read, don’t you?’ When Harriet moved her head solemnly Marilyn said, ‘so do I,’ and then stopped to think.

‘Do you get library books? she asked.

‘No,’ Harriet said. ‘I’ve never been to the library yet.’

‘Me neither,’ Marilyn said. ‘We could get library cards you know.’

‘Have you read Little Women?’ Harriet asked.

Marilyn shook her head and asked, ‘have you read Vanity Fair?’

‘I haven’t read that yet,’ Harriet said. ‘I liked Little Women, though.’”

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Road Through the Wall on Bookshop.org*

The Road Through the Wall on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Harriet’s mother would presumably be apoplectic if Harriet were to read Vanity Fair. Marilyn tells Harriet about the girls she does not like, including Virginia. “She’s not much,” says Harriet and in “a final recognition of her bond with Marilyn,” she says, “I know something about her.”

Marilyn is from the only Jewish family in the neighborhood. Harriet’s parents are not at first especially anti-Semitic, and the subject only arises in relation to readings of Shakespeare that are being organized; someone mentions that it might be insensitive to read The Merchant of Venice with Marilyn present. Eventually, Harriet’s parents tell her she must not see Marilyn again but before that Harriet and Marilyn have become close, especially in their literary tastes.

One time, Marilyn is talking about reincarnation; she tells Harriet that she might have been Becky Sharp before she was Harriet Merriam, even though Harriet is far closer to Emmy Sedley than to Becky Sharp, who is more like Virginia. ‘“Or Jo March,” Harriet replied, fascinated;’ clearly her friendship with Marilyn has given her the confidence to move up the ladder of the March sisters. Marilyn suggests that they should both write down where they think they will be in ten years’ time, bury the notes and never look at each other’s for the next ten years.

“Rest here, all my hopes and dreams,” says Marilyn as they bury the paper. “The curse be on whoever touches these papers,” adds Harriet. “Now you’re my closest and dearest friend, Harriet.”

After Harriet’s parents have forbidden her to see Marilyn again, Harriet meekly agrees but handles the breakup very badly. Marilyn calls her a fat slob and Harriet now sees Marilyn as being ugly. They never do see each other’s ten-year plans, but we do: a neighborhood boy finds them and Jackson shows them to us. As we have already seen, Jackson knows a thing or two about what teenage girls want. Cunningly, she does not tells which note is which but we can probably work it out.

“In ten years I will be a beautiful charming lovely lady writer without any husband or children but lots of lovers and everyone will read the books I write and want to marry me but I will never marry any of them. I will have lots of money and jewels too.

I will be a famous actress or maybe a painter and everyone will be afraid of me and do what I say.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also like:

An Analysis of We Have Always Lived in the Castle

by Shirley Jackson

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture: