Nava Atlas's Blog, page 36

August 22, 2021

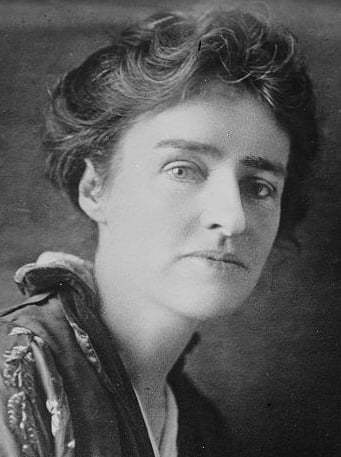

Orphans and Boarding Schools: On rereading Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster

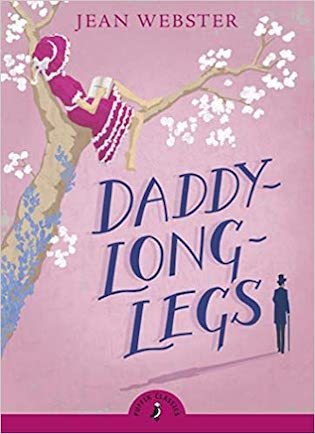

The summer I was twelve, I pulled a well-read and worn book from the shelves of the public library and discovered a story that seemed to be told directly to me. Behind the deceptively dull cover of Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster (1912) were letters and drawings that pulled me hard and fast into Judy Abbott’s life—an orphan at boarding school.

So many of my favorite things were combined in this book: orphans and lonely childhoods, girls succeeding against the odds with their studious natures, boarding school and class events, and perhaps most of all, the burgeoning writer’s sensibility that I also enjoyed in Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy (1964).

I borrowed and devoured Jean Webster’s Daddy-Long-Legs that very afternoon; I’ve revisited it many times.

Orphan girls

Judy’s orphan status reminded me of other favorite characters, from classics like Emily of New Moon (1923) by L.M. Montgomery, Ballet Shoes (1936) by Noel Streatfeild, and A Little Princess (1905) by Frances Hodgson Burnett.

And later-twentieth-century orphans, too, like Mandy the eponymous heroine of Julie Andrews Edwards’ 1971 novel and Christina in K.M. Peyton’s Flambards (1967).

As a kid with recently divorced parents, relocated a couple of hundred miles from familiar territory, I related to these characters’ dislocation. Pseudo-orphans, girls temporarily separated from family—in Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking (1945) and Joan Aiken’s The Wolves of Willoughby Chase (1962)—also appealed.

Even girls unexpectedly living in single-family households like the March sisters in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1880) — Rose Campbell, in Eight Cousins (1874), was a proper orphan but I hadn’t met her yet.

And Judy wasn’t only an orphan, but an orphan keen on rewarding her anonymous benefactor’s investment — not simply surviving, but thriving. The biography of my copy of Daddy-Long-Legs described its author as an orphan, but Jean Webster lived with both parents until she was fifteen years old.

Nonetheless, as Alice Sanford’s article in the Vassar Miscellany (June 1915) explains, the success of Daddy-Long-Legs created many opportunities for actual orphans:

“One hundred orphan children have since been placed in families by the Society of the National Sons and Daughters of the Golden West. Miss Webster has been consulted repeatedly by prominent social workers to suggest improvements in children’s institutional homes, besides being invited to become a Director in many of them.”

Whether true or not, the author having been described as an orphan would have made Judy’s story about life at the John Grier Home and Fergussen College more credible. And decades after the author’s death, Vassar praised Daddy-Long-Legs as “a moving revelation of child-life in an orphanage, timeless in its humor, justice, and lovable make-believe.”

The book’s social welfare message “that under-privileged children, if given a chance, are capable of succeeding in life and of enjoying its beauty” is simple but powerful. (September 1936, Vassar Miscellany)

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Jean Webster

. . . . . . . . .

I also related to the work-in-progress nature of young Jerusha, who changed her name to “Judy” when she went to Fergussen Hall (the author herself changed from “Alice” to “Jean” when she went to college), echoing Anne imagining herself into becoming “Cordelia” in L. M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables (1908).

I was waiting for someone to see the real me, like Judy’s benefactor saw her: “He believes that you have originality, and he is planning to educate you to become a writer.”

In the story, “Jerusha” was said to be a name from a tombstone and a telephone book. In real life, Jean Webster’s friend Ethelyn McKinney had a grandmother named Jerusha, and Jean’s connection to the McKinney family intensified when she married Ethelyn’s brother in 1915 (though nobody claimed the grandmother’s name was an inspiration).

Eventually, Judy’s story would succeed not only on the printed page but on the Broadway stage and multiple Hollywood films. Webster herself adapted the work for theatre and Alice Sanford shares this evidence of the author’s commitment to its success:

“It is a fact that on the opening night of the play in February at Atlantic City, Mr. [Henry] Miller was very nervous and dubious, and said to Miss Webster that he would sell out the house for twenty dollars. She, however, was confident, and predicted a success.”

Boarding schools

I preferred Enid Blyton-style school stories to literary alternatives; Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre bored me after Jane left Lowood and only finished reading it decades later. When Sara Crewe was in classes with Miss Minchin in A Little Princess, life was fine, but her fortunes soon took a turn.

Judy’s life at Fergussen Hall was more bookish than the Naughtiest Girl, St. Clare’s, and Malory Towers stories. Although lacking the privileges of her well-to-do classmates, Judy must catch up scholastically and socially:

“The trouble with college is that you are expected to know such a lot of things you’ve never learned. It’s very embarrassing at times.”

I preferred the stories where children connected with teachers who recognized their talents, and even though I was less fond of books about boys (unless they were one of the Three Investigators or the love interest in a Beverly Cleary romance), a story like Irene Hunt’s The Lottery Rose squeaked past my anti-boy bias because of the boarding-school setting.

Judy includes specifics about her classes and her independent work, which held its own appeal. Jean Webster’s homage to her beloved Vassar College is most immediately recognizable in When Patty Went to College (1903) and Just Patty (1911). But a 1912 review in the Vassar Miscellany by Gabrielle Elliot situates Daddy-Long-Legs there too:

“Perhaps the earmarks are not quite so plain, but when we find the heroine trying to make a tower room livable, taking the ‘entertaining’ Benvenuto Cellini’s life in chunks and writing ‘humorous’ songs for a Glee Club concert our suspicions are more or less confirmed.”

From the perspective of a fellow Vassar graduate, the school setting was one of the novel’s most appealing elements:

“The description of how ‘Judy’ nightly fortified herself behind an engaged sign and acquired in gulps the knowledge which everyone is assumed to have is extremely amusing. Perhaps the most genuine part of the book comes in one or two perceptive touches of the everyday life at college.”

. . . . . . . .

Daddy-Long-Legs on Bookshop.org* and on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Although I warmed to the details of Judy’s coursework—which wars she was studying and which verbs she was conjugating — her growing identity as a writer thrilled me more. In concert with the sense that I — and only I — was the reader of this story, other than the bookish girl who made it.

“I look forward all day to evening, and then I put an ‘engaged’ on the door and get into my nice red bathrobe and furry slippers and pile all the cushions behind me on the couch, and light the brass student lamp at my elbow, and read and read and read. One book isn’t enough. I have four going at once. Just now, they’re Tennyson’s poems and Vanity Fair and Kipling’s Plain Tales and – don’t laugh – Little Women. I find that I am the only girl in college who wasn’t brought up on Little Women. I haven’t told anybody though (that would stamp me as queer).”

Judy’s letters read more like a diary because her benefactor never writes back. Throughout the book, she is reading, mostly for school but sometimes for pleasure: “Excuse me for filling my letters so full of [Robert Louis] Stevenson; my mind is very much engaged with him at present.”

And, eventually, she is writing as much as she is reading, particularly during the summer holidays: “College opens in two weeks and I shall be glad to begin work again. I have worked quite a lot this summer though—six short stories and seven poems. Those I sent to the magazines all came back with the most courteous promptitude. But I don’t mind.”

From the start, it felt like she was writing both to me and about me. Books like Lois Lowry’s Anastasia Krupnik (1979) and Norma Fox Mazer’s I, Trissy (1971) had revealed the power of intimacy in handwritten pages. Judy’s story unfolded decades earlier, but her hand-drawn, near-stick figures were as disproportioned as my own doodles, and her bookishness was recognizable and her friendships were enviable.

Spiders and titles

Judy addresses her letters to Daddy-Long-Legs because of a silhouette she has glimpsed, that of a very tall man (her benefactor), but the title had another genesis, which Alice Sanford describes:

“Five or six summers ago Miss Webster was visiting at the home of her publisher, and as they all were sitting on the porch, a daddy-long-legs dropped into her lap. ‘Oh, a daddy-long-legs,’ she exclaimed — ‘what a capital title for a book!’ and the publisher said upon her leaving, ‘Don’t forget to write the book.’”

Jean Webster didn’t take it seriously, but her publisher did:

“After receiving a mock-up ‘with the picture of a daddy-long-legs emblazoned upon it’ Jean Webster got to work. Over the next couple of years, she noodled the idea and conceived of a ‘little orphan asylum girl, Judy, who finally goes to college through the munificence of the aristocratic Jervis Pendleton, self-styled misogynist.’”

. . . . . . . . . .

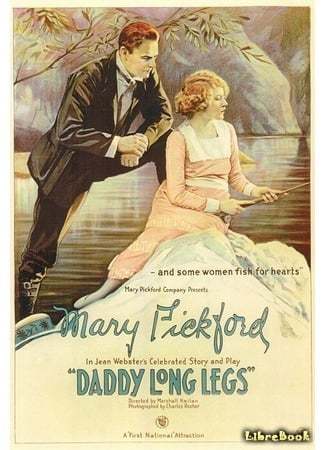

The first film version, 1919

. . . . . . . . . .

Jervis is a shadowy figure in the novel, but in later adaptations, the relationship between him and Judy is more prominent. More than a decade after I first read the book, I finally saw a film that I recognized as being adapted from it.

In between, I had seen Shirley Temple’s Curly Top (1935) but I didn’t recognize it as the same story. The first film, made by Mary Pickford in 1919, wasn’t available (likely for the best, as the orphanage scenes probably would have given me nightmares), although Canadian students studied Mary Pickford in school as dutifully as Judy studied algebra and physiology.

Rewatching the 1955 film Daddy-Long-Legs recently, I was struck by how much of it was about Jervis Pendleton, which is perhaps best explained by the fact that Fred Astaire was cast in the role, opposite Leslie Caron.

Rumor has it that he was surprised to be cast opposite a ballerina, quickly announcing: “Kid, you’re going to have to do what I do, because I sure don’t do what you do.” As Judy in the film, Leslie Caron does what Fred Astaire as Jervis does: dancing makes for better showmanship than reading or writing.

Bolstering Daddy-Long-Legs’ popularity has been a series of stage and screen productions: films in 1990 in Japan, and in 2005 in Korea; on-stage as Love from Judy in 1952 in England, as a two-person musical in California in 2009, and stage production in New York City in 2015.

But it’s the novel that holds the most appeal for me. Other readers of classic girls’ stories often count it among their favorites too, both in North America and in England (where many of Jean Webster’s novels were published, often a year or two after their American debut).

In 2005, Amanda Craig, nominated more than once for the International Women’s Fiction Prize, included it in a list of her favorite teen romances in the London Times, describing it like this: “Sweet novel made up of an adopted girl’s letters to her daddy.”

She’s not adopted and he’s not her daddy, yet this statement is no more inaccurate than the biographical note at the back of the novel that identifies Jean Webster as an orphan. The point is that Judy doesn’t feel like she belongs anywhere and her Daddy-Long-Legs helps her believe that she does. It’s a human yearning to connect: it’s what we look for in a story and it’s why I return to Jean Webster’s Daddy-Long-Legs.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

More about Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster Read full text on Project Gutenberg Listen on Librivox Reader discussion on Goodreads Jean Webster on the Vassar Encyclopedia

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Orphans and Boarding Schools: On rereading Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 21, 2021

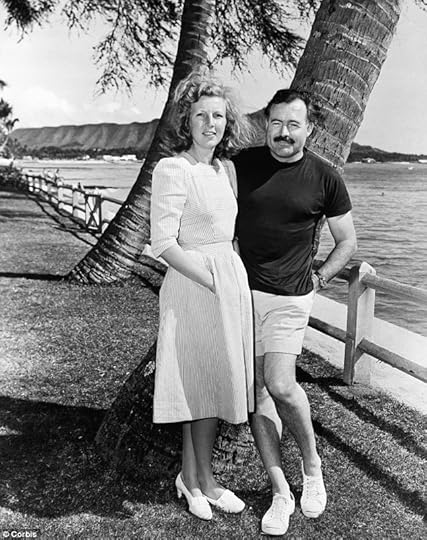

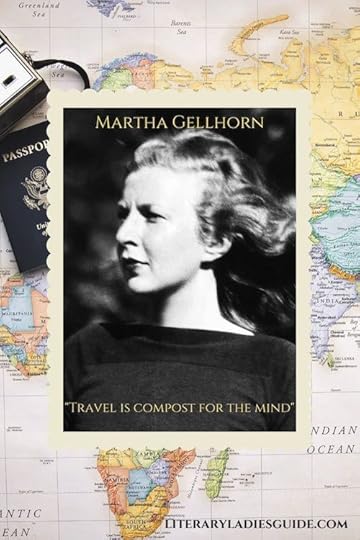

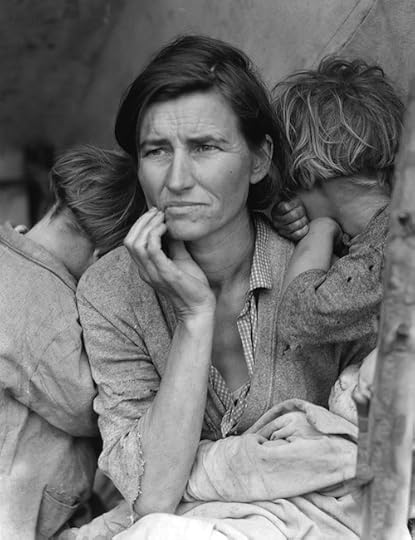

Flint and Steel: The Tumultuous Marriage of Martha Gellhorn & Ernest Hemingway

The esteemed war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, Ernest Hemingway’s third wife, famously said, “Why should I be a footnote to somebody else’s life?” She dreaded being remembered mainly for her doomed marriage to the iconic American author. Hemingway and Gellhorn encouraged each other, supported each other, and once they separated, refused to speak of each other.

It all began when one evening, close to Christmas 1936, the young journalist and writer Martha Gellhorn went to a bar on Key West for a drink. She was with her mother, Edna, and younger brother Alfred, taking a break in the winter sun. The bar was Sloppy Joe’s, and there Martha noticed “a large, dirty man in untidy somewhat soiled white shorts and shirt,” sitting in a corner, drinking and reading his mail.

The man was Ernest Hemingway, and this fairly inauspicious meeting was the start of a relationship that lasted almost ten years. Culminating in a disastrous four-year marriage, their partnership is (in)famous for its volatility, hard drinking, and occasional violence.

But there were also times of love, happiness, and hard work in writing. The tempestuous dynamic between these two enormous literary talents continues to fascinate to this day.

. . . . . . . . .

Photo of Gellhorn and Hemingway by Corbis

. . . . . . . .

When he first met Martha Gellhorn, Ernest Hemingway was living on Key West with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, and three sons: John (known as Bumby), age thirteen; Patrick (nicknamed “Mexican Mouse”), age eight; and Gregory, or Gigi, who was five. Hemingway spent a lot of time fishing in the clear waters off the island and drinking in Sloppy Joe’s, but by the end of 1936 was also planning a trip to Spain to cover the civil war.

His enthusiastic support of the Republican cause had attracted the attention of the North American Newspaper Alliance, who asked him to cover the conflict for them, and he was raising money to buy ambulances as well as planning a documentary film with the Dutch director Joris Ivens.

Gellhorn, though not as well established as Hemingway, had her own accomplishments and ambitions. Her recent book, The Trouble I’ve Seen, based on her experiences of reporting the Great Depression, had received rave reviews, and she’d been hailed as the literary discovery of the decade. She was also very well traveled and aware of the worsening situation in Europe.

After their first drinks in Sloppy Joe’s, Hemingway offered to show the family around the island and, believing Martha and Alfred to be a couple rather than brother and sister, resolved to “get her away from the young punk” as soon as he could.

When Edna and Alfred went home to St Louis a week later, Gellhorn decided to stay to work on her new novel. However, instead of writing, she spent hours talking to Hemingway — about politics, about his love of Cuba, his books, and his new manuscript, which he gave her to read. She did so, “weak with envy and wonder,” but determined not to imitate the style she admired so much. She had found, she wrote to her close friend Eleanor Roosevelt, “an odd bird, very lovable and full of fire and a marvelous storyteller.”

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Martha Gellhorn

Learn more about Martha Gellhorn

. . . . . . . . .

When Martha Gellhorn finally left for St. Louis in the middle of January 1937, Hemingway headed to New York to finalize his preparations for Spain. His regular letters and phone calls gave her encouragement through the long winter days, during which she forced herself to work on her novel for ten pages a day, determined to get it done as quickly as possible so that she could go to Europe herself and “get all the facts tidy.”

But by the time she arrived in New York, Hemingway was almost ready to leave for Spain. His passage was booked and, with obligations to both his documentary film and to the NANA, he had to depart without her. It took several weeks for Gellhorn to procure the required paperwork, eventually persuading a friend at Collier’s magazine to give her special correspondent status.

She sailed in March 1937, writing to a family friend, “Me, I am going to Spain with the boys. I don’t know who the boys are, but I am going with them.”

Too impatient to find a traveling companion among the several hundred men and women going to Spain as part of the International Brigades, Gellhorn set out alone from Paris with only fifty dollars and a backpack full of tinned food. By late March she was in Barcelona, crowded with soldiers and militia of all kinds, and from there made her way to Madrid.

Hemingway, already installed in two rooms in the Hotel Florida, greeted her: “I knew you’d get here, daughter, because I fixed it so you could.” Gellhorn accepted the self-congratulatory twisting of the truth with tolerance but was less understanding the next morning after she found herself locked her in her room during a bombing raid. When Hemingway finally came to let her out he explained that he had done it for her own safety, but she was furious. Later, she wrote, “I should have known at that moment what doom was.”

It didn’t, however, stop her from starting an affair. She didn’t love Hemingway, she claimed, and she wasn’t physically attracted to him, but she admired him and was grateful for his companionship and leadership amid a horrific war. Hemingway regarded himself — and was mostly regarded by others — as the foremost foreign journalist in Spain, and was able to procure supplies, including petrol, where no one else could.

He knew his way around the various fronts and was expert with a gun. As “just about the only blonde in the country,” Gellhorn felt vulnerable, although she would never have shown it. It was, she felt, better to be seen as belonging to someone.

. . . . . . . . .

Photo: JFK Presidential Library and Museum

. . . . . . . . .

It was the first of four trips to Spain over the next two years, interspersed with periods back in America. Hemingway’s film was a success, while Gellhorn’s articles about the human cost of war, the ordinary people, and their lives on the streets were taken enthusiastically by Collier’s and The New Yorker.

Their second trip, in August 1937, was less successful. Gellhorn and Hemingway were attempting to be discreet about their relationship, mostly for Pauline’s sake, and they again traveled from New York on separate ships. By the time they arrived, two-thirds of the country lay in nationalist hands.

Madrid was becoming increasingly cold and uncomfortable, with little food to be had, and in the tough conditions, the differences between the two of them began to slide into violent arguments. Known for being a bully at times, Hemingway was capable of subjecting Gellhorn to torrents of abuse: she described one evening as “a really excellent show but the kind of show usually reserved for enemies.”

By November 8th, Gellhorn’s 29th birthday, she had heard from America that gossip was circulating about her and Hemingway, and swore never again to “get into such a thing … I am in it up to the neck.” She dreaded returning to New York.

Meanwhile, with nothing much happening at the front, Hemingway had started work on a play called The Fifth Column, based largely on his experiences in Spain and including a not-entirely flattering portrait of Martha as Dorothy Bridges, the heroine, whose main feature was her legs and who had “men, affairs, abortions, ambitions.”

Christmas 1937 was spent in America, after a nasty incident in Paris when Pauline, having traveled to confront Hemingway about Gellhorn, threatened to jump off their hotel balcony. Hemingway, with characteristic understatement, confided in Max Perkins that he was in a “gigantic jam” yet returned once more to Spain with Gellhorn in April 1938, leaving an increasingly desperate Pauline in America.

. . . . . . . . .

Martha Gellhorn: Quotes from a Courageous Woman

. . . . . . . . .

By the end of 1938, Hemingway was back in Key West, trying to adapt back into family life with Pauline, but it was evident to visitors that he was unhappy. His brother Leicester noted that he was drinking an average of fifteen Scotch and sodas each day. He eventually retreated to one of his favorite islands, Cuba, to write, and Gellhorn joined him in the early spring of 1939.

She found him split between two hotel rooms in Havana, one for sleeping and one for writing, disheveled as usual, stockpiling food and surrounded by deep-sea fishing tackle (the waters of the Gulf were only half an hour away by boat). Having tolerated his squalid way of hotel living during the war in Spain, Gellhorn found that she couldn’t bear it in Cuba, and determined to find them somewhere more permanent to live.

She found a house in the village of San Francisco de Paula, not far from Havana. A one-story colonial Spanish building called Finca Vigía, it was set in fifteen acres of grounds that had overgrown to jungle density in the tropical heat.

The house hadn’t been lived in for years and needed significant cleaning and renovation, but Gellhorn saw its potential. Their move to the Finca effectively marked the end of Hemingway’s marriage to Pauline.

At first, the two were happy in their new home, writing constantly and leading a disciplined life. Hemingway, who had started work on For Whom The Bell Tolls, rose early and started writing before dawn, using their sunny bedroom as a study.

Gellhorn admired the way he fiercely protected his writing time despite everything there was to do around the house: “He has,” she wrote to a friend, “been about as much use as a stuffed squirrel, but he is turning out a beautiful story. And nothing on earth besides matters to him …”

She was having trouble, per usual, with her book (it would later be published as The Stricken Field), worried that her writing was flat and uninspiring. Reading Hemingway’s work made things worse: she saw her own as “without magic” while his flowed “like the music of a flute.” But she was happy in the Finca, surrounded by the exotic plants she loved, and the view of the sea.

With a break in Wyoming and Idaho over the fall, they continued this routine into the new year, writing in the mornings (Hemingway now tucked up in bed because of the exceptionally cold weather), playing tennis in the afternoons, and, about once a week, driving into Havana for a long night of hard drinking at the Floridita, Hemingway’s favorite bar.

Hemingway’s sons came for a successful visit in March 1940. They liked Gellhorn, calling her “The Marty,” and she relished becoming an instant mother to three good-looking, intelligent, yet very different boys.

Gradually, the differences between them began escalating once again into arguments, just as they had done in Spain. Hemingway found the bad news from Europe intrusive, and eventually banned their radio from the house altogether. Gellhorn found his disinterest annoying and his commitment to his work overbearing.

One letter from Hemingway at this time is a profuse tract of apology, begging her forgiveness for having been “thoughtless, egotistic, mean-spirited and unhelpful.” It was one of the few times he admitted to, and apologized for, any wrongdoing.

A marriage of flint and steel

In September 1940, For Whom The Bell Tolls was published. It sold — as Hemingway put it — “like frozen Daiquiris in hell.” After a stint alone in New York for the initial round of publication events, Hemingway took Gellhorn back to Sun Valley with his sons. They spent happy weeks hunting, riding, fishing, and playing tennis, and became engaged after Hemingway’s divorce from Pauline was finalized.

Gellhorn wore a diamond and sapphire ring she described as “snappy as hell.” Although she had some doubts about marriage (upsetting Hemingway, who wrote that she had given him a “good sound busted heart”) photos from this time show them both happy, windswept, and smiling.

On November 21, 1940 they were married in the dining room of the Union Pacific Railroad in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Several newspapers covered the wedding, with one reporter describing it as a union “of flint and steel,” though which one of them was which was never made clear.

“Honeymoon” in China

Many years later, when Gellhorn was nearly seventy, she wrote a book of the “horror journeys” of her life, Travels With Myself and Another. The book is full of darkly comic stories of terrible discomfort, embarrassing situations, and all the gory details of traveling in strange places with few modern comforts.

She included their “honeymoon trip to China, entitled “Mr. Ma’s Tigers,” one of the funniest in the collection and notable for its tone of affection and self-mockery. Collier’s had asked her to travel to the Far East to cover the war there, and Hemingway, despite grave misgivings, agreed to join her for part of the trip and write some articles for PM magazine. The trip was to start on the Burma Road, not long after their wedding, and Hemingway insisted on calling it their honeymoon.

It started badly, with rolling Pacific waves which made them seasick all the way to Hawaii. Although things started to improve in Hong Kong, where Hemingway found new friends to drink with and delighted in setting off firecrackers in their hotel room, there was the ever-present danger of Japanese bombing, and health concerns, including a prevalence of cholera.

When the couple got permission to travel to the front line, they made the journey in an ancient truck, a derelict boat that let in water, and ponies so small that Hemingway pointed out he could walk and ride at the same time. It was also, as Gellhorn noted, the “mosquito center of the world.”

One night, lying on a board in wet clothes, besieged by flies and mosquitoes, she said, “I want to die.” Hemingway replied, “Too late. Who wanted to come to China?” But when she and Hemingway parted in Rangoon, he wrote, “I am lost without you … with you I have so much fun even on such a lousy trip.”

The Crook Shop, and a Caribbean “journey from hell”

Back in Cuba, Martha settled down to edit the proofs of a collection of stories, The Heart of Another, while Hemingway spent more and more time fishing in the Gulf on his boat, the Pilar. Martha enjoyed joining him when she wasn’t working, and Hemingway told Max Perkins that he was happy with her, that she was just what he needed, and that she had told him she was now going to stop traveling and stay at home.

But the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the entrance of America into the war made them both restless. Still unwilling to travel to Europe, Hemingway started to gather stories for a war anthology, while both he and Gellhorn were intrigued by the idea of setting up a kind of counter-intelligence group in Cuba, similar to the ‘Fifth Column’ of Madrid in the Spanish Civil War.

Hemingway proposed to recruit informants from among his friends in the Havana bars, and, somewhat bizarrely, to equip the Pilar with grenades and machine guns in order to hunt and destroy enemy submarines that might be cruising the Gulf (his idea was to lure them into raising their conning towers, before lobbing grenades down the opening).

In a turn of events that seems ludicrous today, he succeeded in recruiting an eight-man crew and persuaded the FBI to contribute $500 a month for running costs. “Friendless” was the official name of the operation, but it was more often known as the Crook Shop.

As the Crook Shop took over the Finca, and the parties and drinking sessions began to last well into the morning hours, Gellhorn grew more and more impatient. She and Hemingway began to quarrel regularly, even about writing, so when Collier’s suggested that she do some traveling around the Caribbean and write about preparations for war, she was delighted.

But the assignment became another of her journeys from hell. It started in Puerto Rico, which had been turned into a huge naval base, and continued from St. Thomas to Antigua. Gellhorn was held up by hurricanes and heavy rain; she became violently seasick; and one night, while she slept out the bad weather on Saba, she awoke to find that the boat crew had slipped away in the night, leaving her marooned on an island with very few facilities.

She finally made her way off with a derelict motor launch, paying $60 to persuade the elderly captain to take her to Antigua. At her next destination, Surinam, she fractured a wrist and caught dengue fever.

Throughout her trip, Hemingway sent her several letters, most of them loving and intimate, full of life at the Finca and the domestic squabbles of the cats that had taken up residence in the gardens. Responding to a complaint from Gellhorn about life in Cuba, he wrote, “Boy can you hit. Can you hit and do you know where the heart of another lives…”

It was clear on her return that Hemingway had missed her, and Gellhorn spoke of becoming a “good little wife” and giving up reporting so as not to have to leave him again. For a short time, over the summer, they were genuinely happy.

War at home and in Europe

As time went on, Gellhorn grew increasingly tired of Hemingway’s spying activities and heavy drinking. He had quarreled with most of his writer friends and was spending more and more time at sea; on the few occasions he was at the Finca he was moody, depressed, and occasionally violent.

She was finding his slovenly way of living almost unbearable, while he told her that she was obsessed with cleanliness. One night, after a fight about his drunken driving on their way back from a night in Havana, Gellhorn took the wheel of his beloved Lincoln Continental and drove it slowly straight into a tree. She got out and walked back to the Finca, leaving Hemingway with the wrecked car.

Finally, despite the lack of military accreditation for women journalists, and despite all the dangers, Gellhorn decided to go to Europe. She tried to persuade Hemingway to go with her — even after all their arguments, there were still moments of tenderness — but he was reluctant to leave the Finca and the Pilar. From New York, she wrote, “You belong to me … We have a good wide life ahead of us. And I will try to be beautiful when I am old, and if I can’t do that I will try to be good. I love you very much.”

Gellhorn arrived in London in fall 1943. During the weeks that followed, she wrote several long and loving letters to Hemingway, full of the war in London and the people she was meeting, and still encouraging him to join her. Hemingway, though, was drinking heavily alone at the Finca, and wrote less and less often.

To Gellhorn’s mother, with whom he got on well, he wrote that he felt he was dying a little every day. Jealous of Gellhorn but unwilling to join her, he wrote to Max Perkins that he hadn’t “done a damned thing I wanted to do now for well over two years….but then I guess no one else has either except Martha who does exactly what she wants to do as willfully as any spoiled child…”

After six months, despite being desperate not to miss the French landings, Gellhorn decided to return, set on the idea of “blast[ing] him loose from Cuba” and bringing him back to Europe.

“I am wondering now if it ever really worked …”

This time, her return was not so happy. They fought over everything — over the house, over writing, over money -—and Hemingway went so far as to write to Gellhorn’s mother saying that he felt she had become unbalanced during her time in Europe.

“Nothing outside of herself interests her very much … she seems mentally unbalanced, maybe just borderline …” Then, out of the blue, Hemingway announced that he had decided to go to Europe after all, and would be writing articles for Collier’s — a move that effectively jeopardized Gellhorn’s position at the magazine, since officially it was allowed to have only one accredited journalist at the front.

Even more galling for Gellhorn was the fact that, after agreeing to write an article on RAF pilots, Hemingway was given a coveted seat on a plane heading for London, and told her that no women were allowed on board. Later, it turned out that the actress Gertrude Lawrence was also a passenger.

Angry but undeterred, Gellhorn eventually found a place on a Norwegian freighter. On the twenty-day Atlantic crossing, she had plenty of time for reflection, and in letters to friends made clear that she felt the marriage was over:

“He is a good man … He is however bad for me, sadly enough, or maybe wrong for me is the word; and I am wrong for him … I am wondering now if it ever really worked …We quarreled too much I suppose … It is all sickening and I am sad to death …”

When Gellhorn met up with Hemingway in London, she found him once again installed in a hotel, surrounded by hangers-on and drinking heavily. Instead of welcoming her, he seemed to delight in goading her, reducing her to tears and embarrassing those they were with, and one evening stood her up for dinner in favor of Mary Welsh, a young American journalist for the Daily Express. From that night, Gellhorn considered their marriage over.

Divorce and aftermath

It was not an amicable separation. Hemingway was not accustomed to being left by women, and even his sons were not spared his furious attempts to portray himself as the one who had wanted to end it. He wrote to Patrick that he had “torn up my tickets on her and would be glad never to see her again.”

Hemingway and Gellhorn met only twice more: once by accident in Paris in 1944, and later in London to finalize details of their divorce, which came through at the end of 1945.

It was a sad end to a troubled relationship. Later, Hemingway’s youngest son Gregory would say that Gellhorn had been driven away by his father’s bullish behavior and egotism. Gellhorn wrote to her mother that, “A man must be a very great genius to make up for being such a loathsome human being.”

After that, she refused to talk about Hemingway at all. Even in Travels With Myself and Another he was referred to only as UC, and on hearing of his suicide in 1961, her only comment was that she understood why he had done it.

Hemingway, initially outspoken and blustering about their separation, also fell silent on the subject. It’s ironic, then, that speculation, gossip, and fascination with their unconventional love story continued long after they had separated, and survives today in books, biographies, and the sensationalized 2012 film, Hemingway and Gellhorn, 2012.

Further reading

Travels With Myself And Another by Martha Gellhorn (1978)The Hemingway Women by Bernice Kert (1983)Selected Letters 1917-1961 by Ernest Hemingway, edited by Carlos Baker (2003)Martha Gellhorn: A Life by Caroline Moorehead (2004)Ernest Hemingway: A Biography by Mary Dearborn (2018)Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is an author, poet, and artist with a serious case of wanderlust. She is originally from the UK, but has spent time abroad in Europe, the United States, and the Bahamas.

When not traveling or working on her current projects — a chapbook of poetry, “The Cabinet of Lost Things,” and a novel based on the life of modernist writer and illustrator Djuna Barnes — she can be found with her nose in a book, daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Visit her on the web at Elodie Rose Barnes.

The post Flint and Steel: The Tumultuous Marriage of Martha Gellhorn & Ernest Hemingway appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 15, 2021

Time Out of Mind by Rachel Field (1935)

Time Out of Mind by Rachel Field (1894 – 1942) was this American author’s first novel for adults, published in 1935. The following year, it won the National Book Award.

Field had been writing prose and poetry for children and young adults, as well as plays, since 1924. Her major breakthrough, up until Time Out of Mind was released, was the children’s book Hitty: Her First Hundred Years (1929), which won the Newbery Medal.

The story in Time Out of Mind is narrated in the first person by Kate Fernald. Kate, described as a hardy, “square-rigged” girl, comes to the Maine coast home of the Fortune family at the age of ten. She accompanies her mother, who serves as the housekeeper, and grows up with brother and sister Nat and Clarissa Fortune, forging a bond that would last a lifetime. The book begins:

“I was never one to begrudge people their memories. From a child I would listen when they spoke of the past. Mother often remarked upon it as strange in one so young. But I think I must have guessed, even then, at what is now clear to me, though I have not skill enough with words to make it plain. For I know that nothing can be so sweet as remembered joy, and nothing so bitter as despair that no longer has the power to hurt us. And to me the past seems like nothing so much as one of those shells that used to be on every mantelpiece of sea-faring families years ago along the coast of Maine.”

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Rachel Field

. . . . . . . . .

This award-winning novel earned universal praise at the time of its publication; though it’s no longer well known, contemporary readers seem to enjoy it as well. Here are two 1935 reviews of a story worthy of rediscovery:

Maine is Scene of Rachel Field’s Nostalgic SagaFrom the original review in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 27, 1935: The cycle of the seasons, spring and summer, autumn and winter, along the blue Penobscot Bay, forms the radiant background for Rachel Fields’s nostalgic saga of Maine folks and tall-masted sailing ships.

The pungent odor of the majestic pines and the harbors about which the fortune of a great shipping family eddies, permeates each page of Time Out of Mind, a shining example of the renaissance of the traditional romantic novel.

From these pages there arises another stalwart “square-rigged” figure, Kate Fernald, who belongs alongside Mary Peters and others of her caliber in the Maine hall of fictional fame.

Kate, daughter of the housekeeper, came to Fortune’s Folly, the great white-columned home of the Fortune family when she was ten years old. As an old woman, she draws upon her storehouse of poignant memories to relate the story of the disintegration of the Fortunes, ship-builders for three generations.

Major Fortune, heir to the tradition that “there’s no port too far for Fortune pines to cast their shadows,” was too blindly willful to read the doom of canvas in the encroachment of steam. His failure to read this handwriting on the wall spelled disaster for his fortune and his family.

Rissa (short for Clarissa), the arrogant and lovely daughter, and Nat, his son, whose physical unfitness to step into the Major’s shoes and love of music rankled his father.

There is a sense of foreboding at the torchlight launching of the Rainbow, the last of the Fortune ships to sail the seas, and well there might have been for the sailing of the Rainbow marked the beginning of the Fortune’s decline.

Trembling, white-faced twelve-year-old Nat is forced by his father to make a hand on the maiden voyage, to return a year later permanently broken in spirit and health. Rissa and Kate Fernald, equally loving Nat, scheme to protect him from the Major. This jealous struggle to draw him within the circle of love continues through the story.

Rissa and Nat escape from the stern shadow of the Folly to Paris. The Major, never recovered from the fate of the Rainbow, is laid to rest in the Little Prospect Cemetery, but Kate Fernald stays on, happy in the daily chores, scouring the Maine countryside for ripe red berries and russet apples, suffering an occasional twinge from the failure of her plan for marriage.

Kate still harbors a notion that Rissa, Nat, and she will be together again in the big house, the grandeur of which is slowly fading in the shadow of the pert modern homes of the summer visitors that are slowly and surely crowding the acres of the Fortune shoreline.

In the tragic climax of Nat and Rissa’s return, Kate’s strength in the face of failure is a memorable characterization and the resultant lump in the throat, the product of Miss Field’s word artistry, might be termed senile sentimentality by the foes of romanticism, but we prefer to call it just a natural involuntary reaction to the author’s force and skill.

In the end, Kate Fernald hears the strike of the quaint French clock, symbolic of the flow of time through the years and all that remains to her of the Fortune’s possessions, and she finds herself left alone “to fill the last pages of the Major’s old logbooks.”

Strong in color with a quiet rhythm all its own, Time Out of Mind is a sturdy tale, as fresh and clean as the tang of a New England breeze.

. . . . . . . . .

Time Out of Mind by Rachel Field on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

From The Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), April 6, 1935: In the words of Major Fortune, last of the ship-building Fortunes whose vessels for generations had been known the world around, Kate Fernald, who tells the story in Time Out of Mind, was “a square-rigged girl” and “a four-square girl.”

When Kate was only ten years old, her father died and her mother gave up the farm where they had lived. The two came to “Fortune’s Folly,” the great house of Major Fortune, where Kate’s mother took the position of housekeeper. From that time on, there grew in this simple, warmhearted country girl a conflict between two widely divergent ways of life — the reckless and lordly manner that came to a Fortune, and the sweet and lowly, the good and honest path that so many of the world’s toilers take.

Yet Kate had no pretense about her, and the conflict wasn’t due to any importance she stressed upon the highborn — rather, it was a conflict in loyalties. She was faithful to her own kind, but she was faithful to these Fortunes too, even to the Major who had been so cruel and unjust to his son, Nat, simply because the boy had a taste for music instead of ships.

Kate was only a child when she came to Fortune’s Folly and she wasn’t regarded as a servant, or even as the daughter of a servant, yet there was a kind of barrier between Kate and Nat and Rissa, the daughter of the Major, just the same. They played together, they confided in each other, they formed a secret society to outwit the Major so that Nat could practice his beloved music.

But Kate as well as the Fortune children know that they belonged to different worlds. Nat was less conscious of this than Rissa, indeed. Nat was so absorbed in his music that he was scarcely aware of being a Fortune, certainly, he was not the conventional son of a line of strong men. No, he was weak and puny and had a bad heart. He was marked for glory, as a fortune-teller predicted, but he was also marked for death.

The big-souled Kate, the narrator of this story, looked backward as old people do, remembering feeling, sensing every detail of the scene, which is the Maine coast, recalling words, inflections, gestures of persons she had known in her girlhood and young womanhood.

As she relates this tale, she has had a job in the post office of Little Prospect, and for thirty years has led an obscure and blameless life with a modest role in the community.

Once in a while, someone who knows the strange story of Nat’s death, and about his having come home to stay at Fortune’s Folly when Kate was there alone; a broken-down Nat it was who had found fame but not happiness.

. . . . . . . . .

The Field House by Robin Clifford Wood —

Rediscovering Rachel Field

. . . . . . . . .

Once in a while, a garbled old piece of gossip will be repeated. But those who hear the talk do not pay much heed; it is difficult to get excited about the irregular romance of a person who is very old. It all happened so long ago, one will say; perhaps it never happened.

It was a happy thought by Rachel Field to have Kate herself tell the story, because by this means the author achieved a character of great significance. Kate unconsciously reveals her sterling qualities — her bravery, goodness, independence, and capacities for loving, giving, and serving.

Kate herself told Nat once that “it’s better to feel something too much, even if it spills over.” She thought it was “better than drying up slow from the inside.” And it is a remembered abundance of love and a remembered desire to spend herself, even recklessly, that kept Kate from being a tragic spinster and letting those free-flowing founts of her being dry up.

This is a book that anyone can enjoy and it’s recommended unreservedly to all who appreciate the land and the trees and the movements of the tides and for characters who are consistent with their heritage and upbringing. It is a book filled with the mellowness, the bright sun, and the wild rain that natives of the Maine coast know.

It is filled with a repetition of nature’s warmth and growth and storm, nature’s occasional flashes of cruelty. Rachel Field depicts these places and their people so surely and so truly.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Time Out of Mind by Rachel Field (1935) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 13, 2021

The Dilettante by Edith Wharton (1903 short story-full text)

The Dilettante by Edith Wharton is a short story that was first published in Harper’s Magazine in 1903, and then was part of The Descent of Man and Other Stories in 1904. Close on the heels of this short story collection, Wharton’s very successful first novel, The House of Mirth, was published in 1905, establishing her as a major figure in American literature.

The story centers around the relationship of Mrs. Vervain and Thursdale. Mrs. Vervain is in love with him, though he considers her just a friend (this possibly echoes some of Wharton’s own relationships with men). Arrogantly, Thursdale (the dilettante of the story’s title) even considers Mrs. Vervain something of his own creation. He describes her as “the finest material to work on,” almost as if she is merely clay in his hands.

The dictionary defines a dilettante as “a person who cultivates an area of interest, such as the arts, without real commitment or knowledge.”

It’s worth considering being a dilettante applies to Thursdale and the women in his life. He looks back on attempts at commitment as mistakes, comparing them to “long walks back from a picnic when one has to carry all the crockery one has finished using.”

The Dilettante, which is in the public domain, is reprinted here in full. Some of the long paragraphs have been broken up for easier readability. Edith Wharton’s The Descent of Man is not to be confused, of course, with Charles Darwin’s book of the same title.

The Dilettante by Edith Wharton

It was on an impulse hardly needing the arguments he found himself advancing in its favor, that Thursdale, on his way to the club, turned as usual into Mrs. Vervain’s street.

The “as usual” was his own qualification of the act; a convenient way of bridging the interval—in days and other sequences—that lay between this visit and the last. It was characteristic of him that he instinctively excluded his call two days earlier, with Ruth Gaynor, from the list of his visits to Mrs. Vervain: the special conditions attending it had made it no more like a visit to Mrs. Vervain than an engraved dinner invitation is like a personal letter.

Yet it was to talk over his call with Miss Gaynor that he was now returning to the scene of that episode; and it was because Mrs. Vervain could be trusted to handle the talking over as skillfully as the interview itself that, at her corner, he had felt the dilettante’s irresistible craving to take a last look at a work of art that was passing out of his possession.

On the whole, he knew no one better fitted to deal with the unexpected than Mrs. Vervain. She excelled in the rare art of taking things for granted, and Thursdale felt a pardonable pride in the thought that she owed her excellence to his training.

Early in his career Thursdale had made the mistake, at the outset of his acquaintance with a lady, of telling her that he loved her and exacting the same avowal in return. The latter part of that episode had been like the long walk back from a picnic, when one has to carry all the crockery one has finished using: it was the last time Thursdale ever allowed himself to be encumbered with the debris of a feast.

He thus incidentally learned that the privilege of loving her is one of the least favors that a charming woman can accord; and in seeking to avoid the pitfalls of sentiment he had developed a science of evasion in which the woman of the moment became a mere implement of the game.

He owed a great deal of delicate enjoyment to the cultivation of this art. The perils from which it had been his refuge became naively harmless: was it possible that he who now took his easy way along the levels had once preferred to gasp on the raw heights of emotion?

Youth is a high-colored season; but he had the satisfaction of feeling that he had entered earlier than most into that chiar’oscuro of sensation where every half-tone has its value.

As a promoter of this pleasure no one he had known was comparable to Mrs. Vervain. He had taught a good many women not to betray their feelings, but he had never before had such fine material to work in.

She had been surprisingly crude when he first knew her; capable of making the most awkward inferences, of plunging through thin ice, of recklessly undressing her emotions; but she had acquired, under the discipline of his reticences and evasions, a skill almost equal to his own, and perhaps more remarkable in that it involved keeping time with any tune he played and reading at sight some uncommonly difficult passages.

It had taken Thursdale seven years to form this fine talent; but the result justified the effort. At the crucial moment she had been perfect: her way of greeting Miss Gaynor had made him regret that he had announced his engagement by letter.

It was an evasion that confessed a difficulty; a deviation implying an obstacle, where, by common consent, it was agreed to see none; it betrayed, in short, a lack of confidence in the completeness of his method. It had been his pride never to put himself in a position which had to be quitted, as it were, by the back door; but here, as he perceived, the main portals would have opened for him of their own accord.

All this, and much more, he read in the finished naturalness with which Mrs. Vervain had met Miss Gaynor. He had never seen a better piece of work: there was no over-eagerness, no suspicious warmth, above all (and this gave her art the grace of a natural quality) there were none of those damnable implications whereby a woman, in welcoming her friend’s betrothed, may keep him on pins and needles while she laps the lady in complacency.

So masterly a performance, indeed, hardly needed the offset of Miss Gaynor’s door-step words—”To be so kind to me, how she must have liked you!”—though he caught himself wishing it lay within the bounds of fitness to transmit them, as a final tribute, to the one woman he knew who was unfailingly certain to enjoy a good thing.

It was perhaps the one drawback to his new situation that it might develop good things which it would be impossible to hand on to Margaret Vervain.

The fact that he had made the mistake of underrating his friend’s powers, the consciousness that his writing must have betrayed his distrust of her efficiency, seemed an added reason for turning down her street instead of going on to the club. He would show her that he knew how to value her; he would ask her to achieve with him a feat infinitely rarer and more delicate than the one he had appeared to avoid.

Incidentally, he would also dispose of the interval of time before dinner: ever since he had seen Miss Gaynor off, an hour earlier, on her return journey to Buffalo, he had been wondering how he should put in the rest of the afternoon. It was absurd, how he missed the girl….Yes, that was it; the desire to talk about her was, after all, at the bottom of his impulse to call on Mrs. Vervain!

It was absurd, if you like—but it was delightfully rejuvenating. He could recall the time when he had been afraid of being obvious: now he felt that this return to the primitive emotions might be as restorative as a holiday in the Canadian woods. And it was precisely by the girl’s candor, her directness, her lack of complications, that he was taken.

The sense that she might say something rash at any moment was positively exhilarating: if she had thrown her arms about him at the station he would not have given a thought to his crumpled dignity. It surprised Thursdale to find what freshness of heart he brought to the adventure; and though his sense of irony prevented his ascribing his intactness to any conscious purpose, he could but rejoice in the fact that his sentimental economies had left him such a large surplus to draw upon.

Mrs. Vervain was at home—as usual. When one visits the cemetery one expects to find the angel on the tombstone, and it struck Thursdale as another proof of his friend’s good taste that she had been in no undue haste to change her habits.

. . . . . . . . .

The Descent of Man and Other Stories on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

The whole house appeared to count on his coming; the footman took his hat and overcoat as naturally as though there had been no lapse in his visits; and the drawing-room at once enveloped him in that atmosphere of tacit intelligence which Mrs. Vervain imparted to her very furniture.

It was a surprise that, in this general harmony of circumstances, Mrs. Vervain should herself sound the first false note.

“You?” she exclaimed; and the book she held slipped from her hand.

It was crude, certainly; unless it were a touch of the finest art. The difficulty of classifying it disturbed Thursdale’s balance.

“Why not?” he said, restoring the book. “Isn’t it my hour?” And as she made no answer, he added gently, “Unless it’s some one else’s?”

She laid the book aside and sank back into her chair. “Mine, merely,” she said.

“I hope that doesn’t mean that you’re unwilling to share it?”

“With you? By no means. You’re welcome to my last crust.”

He looked at her reproachfully. “Do you call this the last?”

She smiled as he dropped into the seat across the hearth. “It’s a way of giving it more flavor!”

He returned the smile. “A visit to you doesn’t need such condiments.”

She took this with just the right measure of retrospective amusement.

“Ah, but I want to put into this one a very special taste,” she confessed.

Her smile was so confident, so reassuring, that it lulled him into the imprudence of saying, “Why should you want it to be different from what was always so perfectly right?”

She hesitated. “Doesn’t the fact that it’s the last constitute a difference?”

“The last—my last visit to you?”

“Oh, metaphorically, I mean—there’s a break in the continuity.”

Decidedly, she was pressing too hard: unlearning his arts already!

“I don’t recognize it,” he said. “Unless you make me—” he added, with a note that slightly stirred her attitude of languid attention.

She turned to him with grave eyes. “You recognize no difference whatever?”

“None—except an added link in the chain.”

“An added link?”

“In having one more thing to like you for—your letting Miss Gaynor see why I had already so many.” He flattered himself that this turn had taken the least hint of fatuity from the phrase.

Mrs. Vervain sank into her former easy pose. “Was it that you came for?” she asked, almost gaily.

“If it is necessary to have a reason—that was one.”

“To talk to me about Miss Gaynor?”

“To tell you how she talks about you.”

“That will be very interesting—especially if you have seen her since her second visit to me.”

“Her second visit?” Thursdale pushed his chair back with a start and moved to another. “She came to see you again?”

“This morning, yes—by appointment.”

He continued to look at her blankly. “You sent for her?”

“I didn’t have to—she wrote and asked me last night. But no doubt you have seen her since.”

Thursdale sat silent. He was trying to separate his words from his thoughts, but they still clung together inextricably. “I saw her off just now at the station.”

“And she didn’t tell you that she had been here again?”

“There was hardly time, I suppose—there were people about—” he floundered.

“Ah, she’ll write, then.”

He regained his composure. “Of course she’ll write: very often, I hope. You know I’m absurdly in love,” he cried audaciously.

She tilted her head back, looking up at him as he leaned against the chimney-piece. He had leaned there so often that the attitude touched a pulse which set up a throbbing in her throat. “Oh, my poor Thursdale!” she murmured.

“I suppose it’s rather ridiculous,” he owned; and as she remained silent, he added, with a sudden break—”Or have you another reason for pitying me?”

Her answer was another question. “Have you been back to your rooms since you left her?”

“Since I left her at the station? I came straight here.”

“Ah, yes—you could: there was no reason—” Her words passed into a silent musing.

Thursdale moved nervously nearer. “You said you had something to tell me?”

“Perhaps I had better let her do so. There may be a letter at your rooms.”

“A letter? What do you mean? A letter from her? What has happened?”

His paleness shook her, and she raised a hand of reassurance. “Nothing has happened—perhaps that is just the worst of it. You always hated, you know,” she added incoherently, “to have things happen: you never would let them.”

“And now—?”

“Well, that was what she came here for: I supposed you had guessed. To know if anything had happened.”

“Had happened?” He gazed at her slowly. “Between you and me?” he said with a rush of light.

The words were so much cruder than any that had ever passed between them that the color rose to her face; but she held his startled gaze.

“You know girls are not quite as unsophisticated as they used to be. Are you surprised that such an idea should occur to her?”

His own color answered hers: it was the only reply that came to him.

Mrs. Vervain went on, smoothly: “I supposed it might have struck you that there were times when we presented that appearance.”

He made an impatient gesture. “A man’s past is his own!”

“Perhaps—it certainly never belongs to the woman who has shared it. But one learns such truths only by experience; and Miss Gaynor is naturally inexperienced.”

“Of course—but—supposing her act a natural one—” he floundered lamentably among his innuendoes—”I still don’t see—how there was anything—”

“Anything to take hold of? There wasn’t—”

“Well, then—?” escaped him, in crude satisfaction; but as she did not complete the sentence he went on with a faltering laugh: “She can hardly object to the existence of a mere friendship between us!”

“But she does,” said Mrs. Vervain.

Thursdale stood perplexed. He had seen, on the previous day, no trace of jealousy or resentment in his betrothed: he could still hear the candid ring of the girl’s praise of Mrs. Vervain. If she were such an abyss of insincerity as to dissemble distrust under such frankness, she must at least be more subtle than to bring her doubts to her rival for solution.

The situation seemed one through which one could no longer move in a penumbra, and he let in a burst of light with the direct query: “Won’t you explain what you mean?”

Mrs. Vervain sat silent, not provokingly, as though to prolong his distress, but as if, in the attenuated phraseology he had taught her, it was difficult to find words robust enough to meet his challenge. It was the first time he had ever asked her to explain anything; and she had lived so long in dread of offering elucidations which were not wanted, that she seemed unable to produce one on the spot.

At last she said slowly: “She came to find out if you were really free.”

Thursdale colored again. “Free?” he stammered, with a sense of physical disgust at contact with such crassness.

“Yes—if I had quite done with you.” She smiled in recovered security. “It seems she likes clear outlines; she has a passion for definitions.”

“Yes—well?” he said, wincing at the echo of his own subtlety.

“Well—and when I told her that you had never belonged to me, she wanted me to define my status—to know exactly where I had stood all along.”

Thursdale sat gazing at her intently; his hand was not yet on the clue. “And even when you had told her that—”

“Even when I had told her that I had had no status—that I had never stood anywhere, in any sense she meant,” said Mrs. Vervain, slowly—”even then she wasn’t satisfied, it seems.”

He uttered an uneasy exclamation. “She didn’t believe you, you mean?”

“I mean that she did believe me: too thoroughly.”

“Well, then—in God’s name, what did she want?”

“Something more—those were the words she used.”

“Something more? Between—between you and me? Is it a conundrum?” He laughed awkwardly.

“Girls are not what they were in my day; they are no longer forbidden to contemplate the relation of the sexes.”

“So it seems!” he commented. “But since, in this case, there wasn’t any—” he broke off, catching the dawn of a revelation in her gaze.

“That’s just it. The unpardonable offence has been—in our not offending.”

He flung himself down despairingly. “I give it up!—What did you tell her?” he burst out with sudden crudeness.

“The exact truth. If I had only known,” she broke off with a beseeching tenderness, “won’t you believe that I would still have lied for you?”

“Lied for me? Why on earth should you have lied for either of us?”

“To save you—to hide you from her to the last! As I’ve hidden you from myself all these years!” She stood up with a sudden tragic import in her movement. “You believe me capable of that, don’t you? If I had only guessed—but I have never known a girl like her; she had the truth out of me with a spring.”

“The truth that you and I had never—”

“Had never—never in all these years! Oh, she knew why—she measured us both in a flash. She didn’t suspect me of having haggled with you—her words pelted me like hail. ‘He just took what he wanted—sifted and sorted you to suit his taste. Burnt out the gold and left a heap of cinders. And you let him—you let yourself be cut in bits’—she mixed her metaphors a little—’be cut in bits, and used or discarded, while all the while every drop of blood in you belonged to him! But he’s Shylock—and you have bled to death of the pound of flesh he has cut out of you.’ But she despises me the most, you know—far the most—” Mrs. Vervain ended.

The words fell strangely on the scented stillness of the room: they seemed out of harmony with its setting of afternoon intimacy, the kind of intimacy on which at any moment, a visitor might intrude without perceptibly lowering the atmosphere. It was as though a grand opera-singer had strained the acoustics of a private music-room.

Thursdale stood up, facing his hostess. Half the room was between them, but they seemed to stare close at each other now that the veils of reticence and ambiguity had fallen.

His first words were characteristic. “She does despise me, then?” he exclaimed.

“She thinks the pound of flesh you took was a little too near the heart.”

He was excessively pale. “Please tell me exactly what she said of me.”

“She did not speak much of you: she is proud. But I gather that while she understands love or indifference, her eyes have never been opened to the many intermediate shades of feeling. At any rate, she expressed an unwillingness to be taken with reservations—she thinks you would have loved her better if you had loved some one else first. The point of view is original—she insists on a man with a past!”

“Oh, a past—if she’s serious—I could rake up a past!” he said with a laugh.

“So I suggested: but she has her eyes on his particular portion of it. She insists on making it a test case. She wanted to know what you had done to me; and before I could guess her drift I blundered into telling her.”

Thursdale drew a difficult breath. “I never supposed—your revenge is complete,” he said slowly.

He heard a little gasp in her throat. “My revenge? When I sent for you to warn you—to save you from being surprised as I was surprised?”

“You’re very good—but it’s rather late to talk of saving me.” He held out his hand in the mechanical gesture of leave-taking.

“How you must care!—for I never saw you so dull,” was her answer. “Don’t you see that it’s not too late for me to help you?” And as he continued to stare, she brought out sublimely: “Take the rest—in imagination! Let it at least be of that much use to you. Tell her I lied to her—she’s too ready to believe it! And so, after all, in a sense, I sha’n’t have been wasted.”

His stare hung on her, widening to a kind of wonder. She gave the look back brightly, unblushingly, as though the expedient were too simple to need oblique approaches. It was extraordinary how a few words had swept them from an atmosphere of the most complex dissimulations to this contact of naked souls.

It was not in Thursdale to expand with the pressure of fate; but something in him cracked with it, and the rift let in new light. He went up to his friend and took her hand.

“You would do it—you would do it!”

She looked at him, smiling, but her hand shook.

“Good-by,” he said, kissing it.

“Good-by? You are going—?”

“To get my letter.”

“Your letter? The letter won’t matter, if you will only do what I ask.”

He returned her gaze. “I might, I suppose, without being out of character. Only, don’t you see that if your plan helped me it could only harm her?”

“Harm her?“

“To sacrifice you wouldn’t make me different. I shall go on being what I have always been—sifting and sorting, as she calls it. Do you want my punishment to fall on her?“

She looked at him long and deeply. “Ah, if I had to choose between you—!”

“You would let her take her chance? But I can’t, you see. I must take my punishment alone.”

She drew her hand away, sighing. “Oh, there will be no punishment for either of you.”

“For either of us? There will be the reading of her letter for me.”

She shook her head with a slight laugh. “There will be no letter.”

Thursdale faced about from the threshold with fresh life in his look. “No letter? You don’t mean—”

“I mean that she’s been with you since I saw her—she’s seen you and heard your voice. If there is a letter, she has recalled it—from the first station, by telegraph.”

He turned back to the door, forcing an answer to her smile. “But in the mean while I shall have read it,” he said.

The door closed on him, and she hid her eyes from the dreadful emptiness of the room.

. . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Dilettante by Edith Wharton (1903 short story-full text) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 8, 2021

Mina Loy’s Feminist Manifesto (1914): Foresight and Controversy

Mina Loy’s Feminist Manifesto is considered among her most notable works, though it wasn’t published until well after her death. In this 1914 piece, Loy vehemently asserted women’s need to fight for their selfhood rather than subsuming their personalities and desires to those of the patriarchy.

Mina Loy (1882 – 1966), the English-born modernist poet, playwright, and artist was was lauded by her peers for her dense analyses of the female experience in early twentieth-century Western society. The undercurrent of the Manifesto hints at Loy’s struggles with modernism — the artistic philosophy of her day — and its central aesthetic of impersonality.

Feminist Manifesto was finally published in 1982, in The Last Lunar Baedeker, a posthumous collection of her various works, including essays and poetry.

By writing the Manifesto before women even achieved the right to vote on either side of the Atlantic, it might be tempting to say that Loy was far ahead of her time. In many ways, she was indeed, but truthfully, she was expressing the frustration that legions of women of her day felt at their lack of rights and inferior position.

Why hasn’t the Manifesto stood the test time as a relevant feminist tract? There are at least two fatal flaws. It’s marred by the passage that begins, “Every woman of superior intelligence should realize her race-responsibility …” which has been interpreted as possibly rooted in eugenicist thought.

In addition, Loy argues for “the unconditional surgical destruction of virginity throughout the female population at puberty.” Though this assertion was made due to the value of virginity to the roles of wife and mistress, the suggestion is as abhorrent now as it was back in 1914.

Analyses of Feminist Manifesto

Here are links to two insightful analyses of Mina Loy’s Feminist Manifesto:

“Feminist Manifesto, that now most popular text, is actually shot through with a dilemma: as a feminist and woman writer, Loy wants to claim women’s equality within modernism; yet, she also seems to feel that modernist impersonality, a key aesthetic of the period, is a luxury that women writers cannot afford.” (by Christina Walter, for the Yale Modernism Lab)

“… It is a short work — in fact it can be read in just a couple of minutes — but the striking tone of the manifesto, as well as its highly radical ideas are what make it so memorable. Speaking to women and particularly contemporary feminists rather than patriarchal society, she starts by saying, “The feminist movement as at present instituted is Inadequate.” (“Mina Loy’s Feminist Manifesto” in King’sNews.org)

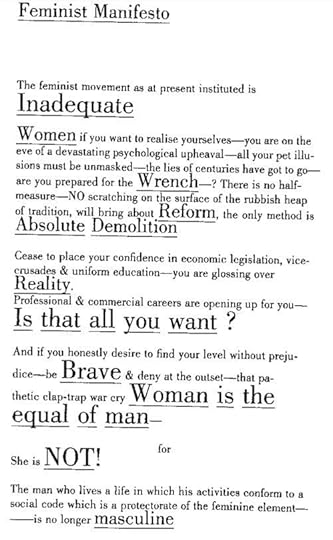

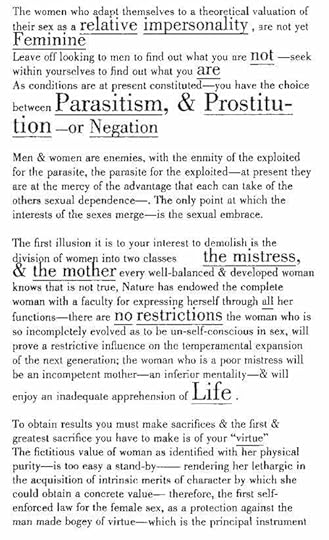

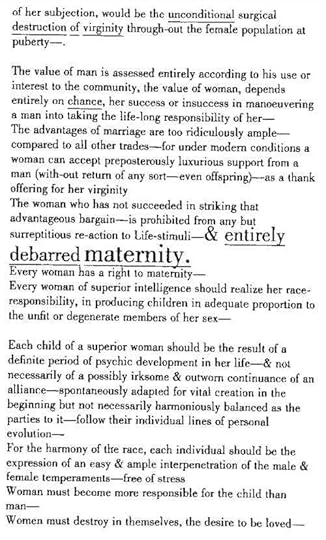

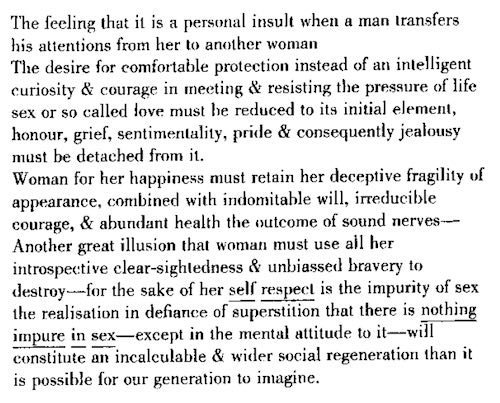

This pictorial representation just below of the Feminist Manifesto is in the original, modernist style that Loy intended for it to be printed. Following this will be a text version for searchability.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Feminist Manifesto by Mina Loy (text version)The feminist movement as at present instituted is

Inadequate

Women if you want to realize yourselves-you are on the

eve of a devastating psychological upheaval-all your pet illu-

sions must be unmasked—the lies of centuries have got to go—

are you prepared for the Wrench—? There is no half-

measure—NO scratching on the surface of the rubbish heap

of tradition, will bring about Reform, the only method is

Absolute Demolition

Cease to place your confidence in economic legislation, vice-

crusades & uniform education-you are glossing over

Reality.

Professional & commercial careers are opening up for you—

Is that all you want?

And if you honestly desire to find your level without preju-

dice—be Brave & deny at the outset—that pa-

thetic clap-trap war cry Woman is the

equal of man—

for

She is NOT!

The man who lives a life in which his activities conform to a

social code which is protectorate of the feminine element—

is no longer masculine

The women who adapt themselves to a theoretical valuation of

their sex as a relative impersonality, are not yet

Feminine

Leave off looking to men to find out what you are not —seek

within yourselves to find out what you are

As conditions are at present constituted—you have the choice

between Parasitism, & Prostitu-

tion—or Negation

Men & women are enemies, with the enmity of the exploited

for the parasite, the parasite for the exploited—at present they

are at the mercy of the advantage that each can take of the

others sexual dependence—. The only point at which the

interests of the sexes merge—is the sexual embrace.

The first illusion it is to your interest to demolish is the

division of women into two classes the mistress,

& the mother every well-balanced & developed woman

knows that is not true, Nature has endowed the complete

functions—there are no restrictions on the woman who is

so incompletely evolved as to be un-self-conscious in sex, will

prove a restrictive influence on the temperamental expansion

of the next generation; the woman who is a poor mistress will

be an incompetent mother—an inferior mentality—& will

enjoy an inadequate apprehension of Life.

To obtain results you must make sacrifices & the first &

greatest sacrifice you have to make is of your ”virtue”

The fictitious value of a woman as identified with her physical

purity—is too easy to stand-by rendering her lethargic in

the acquisition of intrinsic merits of character by which she

could obtain a concrete value—therefore, the fist self-

enforced law for the female sex, as a protection against the

man made bogey of virtue—which is the principal instrument

of her subjection, would be the unconditional surgical

destruction of virginity through-out the female population at

puberty—.

The value of man is assessed entirely according to his use or

interest to the community, the value of woman depends

entirely on chance, her success or insuccess in maneouvering

a man into taking the life-long responsibility of her—

The advantages of marriage are too ridiculously ample—

compared to all other trades—for under modern conditions a

woman can accept preposterously luxurious support from a

man (with-out the return of an sort—even offspring)—as a thank

offering for her virginity

The woman who has not succeeded in striking that

advantageous bargain—is prohibited from any but

surreptitious re-action to Life-stimuli—& entirely

debarred maternity.

Every woman has a right to maternity—

Every woman of superior intelligence should realize her race-

responsibility, in producing children in adequate proportion to

the unfit or degenerate members of her sex—

Each child of a superior woman should be the result of a

definite period of psychic development in her life—& and not

necessarily of a possible irksome & outworn continuance of an

alliance—spontaneously adapted for vital creation in the

beginning but not necessarily harmoniously balanced as the

parties to it—follow their individual lines of personal

evolution—

For the harmony of race, each individual should be the

expression of an easy & ample interpenetration of the male &

female temperaments—free of stress

Woman must become more responsible for the child than

man—

Woman must destroy in themselves, the desire to be loved—

The feeling that it is a personal insult when a man transfers

his attention from her to another woman

The desire for comfortable protection instead of an intelligent

curiosity & courage in meeting & resisting the pressure of life

sex or so called love must be reduced to its initial element,

honour, grief, sentimentality, pride and & consequently jealousy

must be detached from it.

Woman for her happiness must retain her deceptive fragility of

appearance, combined with indomitable will, irreducible

courage, & abundant health the outcome of sound nerves—

Another great illusion is that woman must use all her

introspective and clear-sightedness & unbiassed bravery to

destroy—for the sake of her self respect is the impurity of sex

the realization in defiance of superstition that there is nothing

impure in sex—except in the mental attitude to it—will

constitute an incalculable & wider social regeneration than it

is possible for our generation to imagine.

. . . . . . . . .

More about Mina Loy on this site

Mina Loy and “The Crowd” — Modernists in 1920s Paris That is the New Rhythm: Mina Loy and Marianne Moore. . . . . . . . .

Mina Loy page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Mina Loy’s Feminist Manifesto (1914): Foresight and Controversy appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 7, 2021

Coup De Grâce by Marguerite Yourcenar (1939)

Coup De Grâce by Marguerite Yourcenar is this noted French author’s 1939 novella, her second such work following Alexis (1929). In a 1988 interview in Paris Review, Yourcenar reveals that the novella’s lead female, Sophie, is very close to herself at twenty.

The brief but emotionally devastating story is of the love triangle between three young people affected by the civil war between the White Russians and the Bolsheviks: Erick and Conrad, best friends from childhood; and Sophie, who is burdened with an unrequited love for Conrad.

From the 1957 Farrar, Straus and Cudahy edition: Coup de Grâce is the second of Mme. Yourcenar’s novels to be translated from the French by Grace Frick in collaboration with the author, Memoirs of Hadrian being the first.