Nava Atlas's Blog, page 37

July 20, 2021

Jean Webster, Author of Daddy-Long-Legs

Jean Webster (July 24, 1876 – June 11, 1916) was an American author best known for her enduring girls’ novel, Daddy-Long-Legs (1912), which was successfully dramatized two years after its publication. Her fiction reveals her dedication to social welfare and her characters often triumph over destitution and injustice.

Born Alice Jane Chandler Webster in Fredonia, New York, the name Jean was acquired later, as a young woman. Her parents, Charles Webster and Annie Moffett Webster, were married in 1875; Alice was their firstborn.

A childhood as Alice

Alice didn’t brag about her great-uncle, Samuel Clemens, who was becoming famous as author Mark Twain — Pamela, in the photograph, being his sister, Jane his mother.

Unsurprisingly, Alice’s childhood was an artistic one. Her grandmother had been a music teacher and “from her earliest childhood, books, and those of the best” surrounded Alice.

Twain established the publishing house Charles L. Webster and Company and appointed Alice’s father as its business manager in 1884 out of frustration with his previous publishers’ delays and royalties. Also in 1884, Alice’s brother Samuel was born, the family’s youngest of three; there were eight years between Samuel and Alice, five years between her and William.

The firm found tremendous success with The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885) and The Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, which Charles was instrumental in soliciting, having previously met Grant while working as an engineer out west.

The extended family now lived in New York City during the year and Long Island in the summer. But Charles’ work was increasingly demanding; networking with the firm’s agents required lengthy and frequent travel.

His health declined in concert with the firm’s fortunes, and although Twain reinvested profits, in 1888, he severed his working relationship with Charles. When Alice was fifteen, in 1891, her father committed suicide.

Public and boarding school, and becoming Jean

After Alice graduated from Fredonia Normal School in 1894, she boarded at Lady Jane Grey School in Binghamton for two years where she was aught academics, music, art, letter-writing, diction, and manners.

Here, she became “Jean” to distinguish herself from her roommate Alice, and had many of the experiences she would immortalize in her Patty stories.

In 1896, she returned to Fredonia Normal School for one year, before attending Vassar College in 1897 — class of 1901. There, she met Adelaide Crapsey, also her roommate and a poet, who became the model for Patty (and, later, Judy).

At Vassar, Jean studied English and Economics, including welfare and penal reform, which led her to work at the College Settlement House; observing class inequities indelibly marked her literary pursuits.

Embarking on the writing life

In the course of publishing short works at Vassar, Jean concealed her connection to Twain, relying on her own merits in approaching an editor at the Poughkeepsie Sunday Courier during her sophomore year. She proposed a weekly Vassar-themed column:

“He looked me over dubiously, and asked if I knew how to write. I told him I did, and that my roommates were pretty good spellers; and I thought between us we could turn out a column a week of chatty news, and that I could go home and try, and he would see how he liked it. I cut my classes more or less during the next week, and succeeded in producing quite a chatty column.”

She describes this in the Vassar Quarterly, along with their unanticipated follow-up discussion about rates, during which Jean hastily suggested $3/week (based on a figure she’d heard was equal to a servant’s weekly wages). She and her roommates celebrated at the Smith Brothers restaurant next door.

The Courier columns developed Jean’s work ethic: she prioritized truthfulness, avoided abbreviations, and elaborated on ordinary stories to make deadlines.

During her junior year, she continued with the Courier, but also spent a semester in Europe: briefly in the UK and France, and extensively in Italy, where she developed her thesis “Pauperism in Italy” and researched for fiction. While traveling with two other Vassar students, she also met and established enduring friendships with Ethelyn McKinney and Lena Weinstein there.

After graduation, she wrote for magazines and assembled her school stories into a manuscript. “Much of her writing was no more than a magazine editor, in search of a Christmas story or of a trifle for a hammock on a sunny day, would pay for—a romance, a melodrama or a detective story,” according to biographers Alan and Mary Simpson.

. . . . . . . . .

Jean Webster page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

After securing a publisher for When Patty Went to College (1903), Jean visited Italy again with her mother. His first was the only book of Jean’s that her great-uncle read; Twain described it as “limpid, bright, sometimes brilliant; it is easy, flowing, effortless, and brimming with girlish spirits … Its humour is genuine, and not often overstrained.” (“Jean Webster.” Twentieth-Century Romance and Historical Writers)

In Italy, Jean worked casually on short stories (which would appear in 1909’s Much Ado about Peter), concertedly on The Wheat Princess (1905), and deepened her attachment to the country, also the setting for her romance, Jerry Junior (1909), about Americans in Italy.

Jean Webster and her friends believed The Wheat Princess contained her best writing, according to Elizabeth Cutting. EMD’s review in the Vassar paper says: “The book is rapid and interesting reading, not once throughout does the attention wander or flag.”

The next year, Jean traveled with Ethelyn and Lena again, to Ireland — with Ethelyn’s older brother. Jean and Glenn concealed their romantic attachment because Glenn was married to, and had a son with, Annette Raynaud; Annette’s frequent hospitalizations for manic depression complicated their divorce.

Jean spent winters in New York City apartments, occasionally attending literary events, and summers in New England farmhouses. Her literary reputation grew, culminating in 1912, when Daddy-Long-Legs, which began the previous summer in Tyringham, MA was serialized in the Ladies’ Home Journal. It was then published as a novel.

Daddy-Long-Legs and Dear Enemy

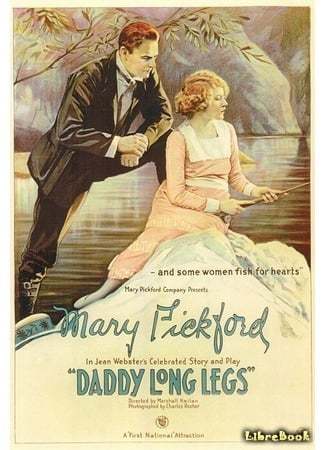

This story about an orphan who writes letters to her anonymous gentleman benefactor, complete with hand-drawn illustrations and a sense of humor, was a grand success. The following summer, Jean began to dramatize Judy’s story for Henry Miller, who produced it for Broadway in the fall of 1914. Jean’s friend Adelaide became ill and died from tuberculosis during that October.

The show ran for 300 performances in New York City with more than 175,000 attendees. After its run ended in May 1915, it toured widely throughout the U.S. and included the sale of Judy dolls, which funded the adoption of orphans into families.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Later, would purchase the film rights and star on-screen; many other screen and stage productions succeeded: most notably in 1955 with Fred Astaire and Leslie Caron, and most recently in 2015, off-Broadway.

Dear Enemy (1915) built on that success. Ruth Danenhower’s review in the May 1916 Vassar Quarterly acknowledges that some might object that Sallie is “simply Judy of Daddy Long-Legs fame over again” but she was “glad to meet Judy again under any other name, and hope she will have many more reincarnations.”

The next September, Jean married Ethelyn’s brother, Glenn Ford McKinney — son of John Luke McKinney, a co-founder of Standard Oil. Glenn was a high-school valedictorian who later studied law at Princeton but wasn’t close with his father. Even so, after his death, Glenn’s estate was valued at more than a million dollars in 1934. Glenn practiced law and the couple first lived together in a New York City apartment, overlooking Central Park, but soon settled on Tymor Farm, Union Vale.

The following June, Jean with her friends Ethelyn and Lena — attended Sloan Hospital for Women in New York City; Glenn was recalled from his Princeton reunion and arrived ninety minutes before Jean gave birth to their daughter. She was named Little Jean in honor of her mother, who died the next morning at 7:30, of “childbirth fever.”

Legacy

A room at the Girls’ Service League in NYC and a bed at the county branch of the New York Orthopedic Hospital (near White Plains), were endowed in Jean Webster’s memory. (American Dictionary of Biography)

In June 1927, a bronze statue called “The Awakening” was erected in Greenwich’s Putnam Cemetery, when Little Jean lived with her aunt, Miss Ethelyn McKinney, described in the New York Times as “slightly larger than life, recumbent figure of a woman, her right arm raised as though to lift a veil, on a pedestal of polished black Swedish granite, with delicate drapery and wreath of laurel about the head.”

In 1977, Jean Webster McKinney Connor donated fifty-two boxes to Vassar College. The Jean Webster Papers included “some correspondence to friends and family, college notebooks, travel journals, as well as later notebooks filled with story ideas, suggestions, and drafts.” In 1981, the Jean Webster Faculty Salary Fund was established, which would later develop into the Jean Webster Chair.

In March 2014, the Vassar Quarterly reported that Daddy Long-Legs inspired Yoshimi Tamai to establish a children’s charity: “And the novel immensely popular in Japan — was greatly inspiring to Ashinaga founder Yoshiomi Tamai, who created the organization to provide education and psychological support to children around the world who have lost one or both parents. The foundation runs programs in Japan for those who have lost parents in the earthquake and tsunami that struck the region in 2011, and in Uganda for those who have lost parents to HIV/AIDS.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

More about Jean WebsterMajor Works

When Patty Went to College (1903)Wheat Princess (1905)Jerry Junior (1907)The Four Pools Mystery (1908)Much Ado About Peter (1909)Just Patty (1911)Daddy-Long-Legs (1912)Dear Enemy (1915)More information

Union Vale’s Jean Webster House Holds Place in Literary History V assar College Encyclopedia Reader discussion on Goodreads Wikipedia Recovering 19th-Century Women AuthorsRead and listen online

Jean Webster’s works on Project Gutenberg Audio editions on Librivox. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Jean Webster, Author of Daddy-Long-Legs appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 15, 2021

Charlotte Lennox, English Novelist, Playwright, and Poet

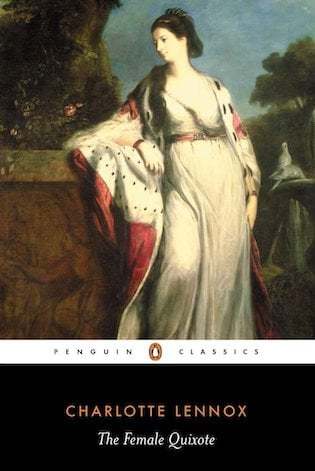

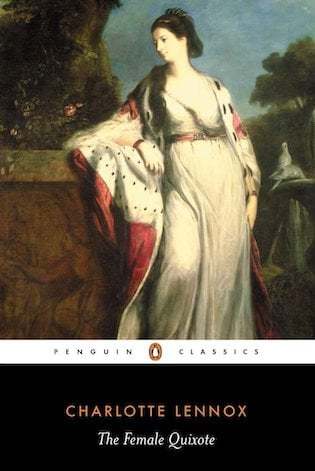

Charlotte Lennox (c. 1730 – 1804), née Barbara Charlotte Ramsay, was an English novelist, playwright, and poet best remembered for her 1752 novel, The Female Quixote. This introduction to her life and work is excerpted from Killing the Angel: Early Transgressive British Woman Writers by Francis Booth ©2021, reprinted by permission.

Charlotte had a peripatetic early life. Born in Gibraltar, the daughter of a Scottish captain in the British Army, she lived her first ten years in England before moving to Albany in New York, where her father was Lieutenant Governor.

After her father’s death in 1742, Charlotte remained in New York with her mother until, at age thirteen, she was sent to London to a companion to her aunt. Her aunt, however, seems to have been mentally unstable, so Charlotte became companion to the unmarried courtier Lady Isabella Finch, cousin of the poet Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea.

The Countess lived in a splendid, newly built townhouse in Berkeley Square in the fashionable heart of London. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was a visitor, as was Horace Walpole.

Poems on Several Occasions (1747)

Lennox’s first published volume of poetry, Poems on Several Occasions (1747) was dedicated to Lady Isabella.

Charlotte was preparing to be a courtier herself, but instead married Alexander Lennox, who had very little money. She turned to stage acting on the stage to earn her own living — a very transgressive thing to do. She had some success, but after Poems was published she turned her focus to writing; ‘The Art of Coquetry’ was published in The Gentleman’s Magazine.

Ye lovely maids! whose yet unpractis’d hearts

Ne’er felt the force of Love’s resistless darts;

Who justly set a value on your charms,

Pow’r all your wish, but beauty all your arms

Who o’er mankind wou’d fain exert your sway

And teach the lordly tyrant to obey;

Attend my rules, to you alone addrest

Deep let them sink in every female breast.

. . . . . . . . . .

Killing the Angel

on Amazon US*

Killing the Angel

on Amazon UK*

. . . . . . . . .

Although the women of the Bluestockings seemed to dislike her, Samuel Johnson was an admirer of Lennox and introduced her to all the leading members of the London literary scene; he threw a party to celebrate the publication of her first novel The Life of Harriot Stewart, Written by Herself.

Johnson, Henry Fielding, and Samuel Richardson favorably reviewed her second and most famous novel, The Female Quixote, or, The Adventures of Arabella (1752) which was published anonymously, though its authorship was an open secret. It is a picaresque, a parody of Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes, clearly influenced by Fielding’s slightly earlier Tom Jones, 1749.

Fielding had published a play Don Quixote in England in 1734 and the title page of his 1742 Joseph Andrews said it was ‘written in imitation of the manner of Cervantes.’ It’s a precursor to Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759 onwards) with its ‘Cervantic humour.’ Like theirs, Lennox’s novel has absurdly long, ironic chapter titles such as:

CHAPTER IV. A Mistake, which produces no great Consequences — An extraordinary Comment upon a Behaviour natural enough — An Instance of a Lady’s Compassion for her Lover, which the Reader may possibly think not very compassionate.

CHAPTER VI. In which the Adventure is really concluded; tho’, possibly, not as the Reader expected.

The Arabella of the title (Arabella is the name of the title character’s older sister in Richardson’s Clarissa, 1748) is something of an idealised woman, educated and cultured, perhaps representing Lennox’ own idealized view of herself.

Nature had indeed given her a most charming Face, a Shape easy and delicate, a sweet and insinuating Voice, and an Air so full of Dignity and Grace, as drew the Admiration of all that saw her. These native Charms were improved with all the Heightenings of Art; her Dress was perfectly magnificent; the best Masters of Music and Dancing were sent for from London to attend her. She soon became a perfect Mistress of the French and Italian Languages, under the Care of her Father; and it is not to be doubted, but she would have made a great Proficiency in all useful Knowledge, had not her whole Time been taken up by another Study.

From her earliest Youth she had discovered a Fondness for Reading, which extremely delighted the Marquis; he permitted her therefore the Use of his Library, in which, unfortunately for her, were great Store of Romances, and, what was still more unfortunate, not in the original French, but very bad Translations.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Translations, literary criticism, and playsLike her character Arabella and some other female writers of the time, Lennox herself learned Italian and translated several Italian works. And, like Elizabeth Montagu, Lennox published a lengthy critical work on William Shakespeare, Shakespear Illustrated, 1753, arguably the first feminist work of literary criticism.

Lennox is mostly concerned with Shakespeare’s sources, but she is also concerned with his female characters; she accuses Shakespeare of ‘taking from them the power and the moral independence which the old romances and novels had given them.’

Her major plays were Philander (1758), The Sister (1769), and Old City Manners (1775).

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

5 Early English Women Writers to Discover

Elizabeth Cary, Early English Poet, Dramatist, and Scholar

The Matchless Orinda: Katherine Philips

Olympe de Gouges: An Introduction

Susanna Centlivre, English Poet and Playwright

. . . . . . . . . .

Lennox published four other novels: Henrietta, 1758 (Lennox also wrote a stage play, The Sister based on the novel); Sofia, 1762; Eliza, 1766 and Euphemia, 1790, but during 1761 and 1762 her main literary output was as the editor of and main contributor to the periodical The Lady’s Museum, The Trifler, advertised as being ‘by the author of The Female Quixote.’ The introduction to the first issue runs:

AS I do not set out with great promises to the public of the wit, humour, and morality, which this pamphlet is to contain, so I expect no reproaches to fall on me, if I should happen to fail in any, or all of these articles.

My readers may depend upon it, I will always be as witty as I can, as humorous as I can, as moral as I can, and upon the whole as entertaining as I can. However, as I have but too much reason to distrust my own powers of pleasing, I shall usher in my pamphlet with the performance of a lady, who possibly would never have suffered it to appear in print, if this opportunity had not offered.

If her sprightly paper meets with encouragement enough to dispel the diffidence natural to a young writer, she will be prevailed upon, I hope, to continue it in this Museum; I shall therefore, without any farther preface, present it to my readers.

More about Charlotte Lennox Rediscovering Charlotte Lennox Charlotte Lennox and the Disciplining of the Female Reader Reader discussion on GoodreadsContributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Charlotte Lennox, English Novelist, Playwright, and Poet appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Charlotte Lennox, English Novelist, Playwright, and Poet: An Introduction

Charlotte Lennox (c. 1730 – 1804), née Barbara Charlotte Ramsay, was an English novelist, playwright, and poet best remembered for her 1752 novel, The Female Quixote. This introduction to her life and work is excerpted from Killing the Angel: Early Transgressive British Woman Writers by Francis Booth ©2021, reprinted by permission.

Charlotte had a peripatetic early life. Born in Gibraltar, the daughter of a Scottish captain in the British Army, she lived her first ten years in England before moving to Albany in New York, where her father was Lieutenant Governor.

After her father’s death in 1742, Charlotte remained in New York with her mother until, at age thirteen, she was sent to London to a companion to her aunt. Her aunt, however, seems to have been mentally unstable, so Charlotte became companion to the unmarried courtier Lady Isabella Finch, cousin of the poet Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea.

The Countess lived in a splendid, newly built townhouse in Berkeley Square in the fashionable heart of London. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was a visitor, as was Horace Walpole.

Poems on Several Occasions (1747)

Lennox’s first published volume of poetry, Poems on Several Occasions (1747) was dedicated to Lady Isabella.

Charlotte was preparing to be a courtier herself, but instead married Alexander Lennox, who had very little money. She turned to stage acting on the stage to earn her own living — a very transgressive thing to do. She had some success, but after Poems was published she turned her focus to writing; ‘The Art of Coquetry’ was published in The Gentleman’s Magazine.

Ye lovely maids! whose yet unpractis’d hearts

Ne’er felt the force of Love’s resistless darts;

Who justly set a value on your charms,

Pow’r all your wish, but beauty all your arms

Who o’er mankind wou’d fain exert your sway

And teach the lordly tyrant to obey;

Attend my rules, to you alone addrest

Deep let them sink in every female breast.

. . . . . . . . . .

Killing the Angel

on Amazon US*

Killing the Angel

on Amazon UK*

. . . . . . . . .

Although the women of the Bluestockings seemed to dislike her, Samuel Johnson was an admirer of Lennox and introduced her to all the leading members of the London literary scene; he threw a party to celebrate the publication of her first novel The Life of Harriot Stewart, Written by Herself.

Johnson, Henry Fielding, and Samuel Richardson favorably reviewed her second and most famous novel, The Female Quixote, or, The Adventures of Arabella (1752) which was published anonymously, though its authorship was an open secret. It is a picaresque, a parody of Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes, clearly influenced by Fielding’s slightly earlier Tom Jones, 1749.

Fielding had published a play Don Quixote in England in 1734 and the title page of his 1742 Joseph Andrews said it was ‘written in imitation of the manner of Cervantes.’ It’s a precursor to Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759 onwards) with its ‘Cervantic humour.’ Like theirs, Lennox’s novel has absurdly long, ironic chapter titles such as:

CHAPTER IV. A Mistake, which produces no great Consequences — An extraordinary Comment upon a Behaviour natural enough — An Instance of a Lady’s Compassion for her Lover, which the Reader may possibly think not very compassionate.

CHAPTER VI. In which the Adventure is really concluded; tho’, possibly, not as the Reader expected.

The Arabella of the title (Arabella is the name of the title character’s older sister in Richardson’s Clarissa, 1748) is something of an idealised woman, educated and cultured, perhaps representing Lennox’ own idealized view of herself.

Nature had indeed given her a most charming Face, a Shape easy and delicate, a sweet and insinuating Voice, and an Air so full of Dignity and Grace, as drew the Admiration of all that saw her. These native Charms were improved with all the Heightenings of Art; her Dress was perfectly magnificent; the best Masters of Music and Dancing were sent for from London to attend her. She soon became a perfect Mistress of the French and Italian Languages, under the Care of her Father; and it is not to be doubted, but she would have made a great Proficiency in all useful Knowledge, had not her whole Time been taken up by another Study.

From her earliest Youth she had discovered a Fondness for Reading, which extremely delighted the Marquis; he permitted her therefore the Use of his Library, in which, unfortunately for her, were great Store of Romances, and, what was still more unfortunate, not in the original French, but very bad Translations.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Translations, literary criticism, and playsLike her character Arabella and some other female writers of the time, Lennox herself learned Italian and translated several Italian works. And, like Elizabeth Montagu, Lennox published a lengthy critical work on William Shakespeare, Shakespear Illustrated, 1753, arguably the first feminist work of literary criticism.

Lennox is mostly concerned with Shakespeare’s sources, but she is also concerned with his female characters; she accuses Shakespeare of ‘taking from them the power and the moral independence which the old romances and novels had given them.’

Her major plays were Philander (1758), The Sister (1769), and Old City Manners (1775).

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

5 Early English Women Writers to Discover

Elizabeth Cary, Early English Poet, Dramatist, and Scholar

The Matchless Orinda: Katherine Philips

Olympe de Gouges: An Introduction

Susanna Centlivre, English Poet and Playwright

. . . . . . . . . .

Lennox published four other novels: Henrietta, 1758 (Lennox also wrote a stage play, The Sister based on the novel); Sofia, 1762; Eliza, 1766 and Euphemia, 1790, but during 1761 and 1762 her main literary output was as the editor of and main contributor to the periodical The Lady’s Museum, The Trifler, advertised as being ‘by the author of The Female Quixote.’ The introduction to the first issue runs:

AS I do not set out with great promises to the public of the wit, humour, and morality, which this pamphlet is to contain, so I expect no reproaches to fall on me, if I should happen to fail in any, or all of these articles.

My readers may depend upon it, I will always be as witty as I can, as humorous as I can, as moral as I can, and upon the whole as entertaining as I can. However, as I have but too much reason to distrust my own powers of pleasing, I shall usher in my pamphlet with the performance of a lady, who possibly would never have suffered it to appear in print, if this opportunity had not offered.

If her sprightly paper meets with encouragement enough to dispel the diffidence natural to a young writer, she will be prevailed upon, I hope, to continue it in this Museum; I shall therefore, without any farther preface, present it to my readers.

More about Charlotte Lennox Rediscovering Charlotte Lennox Charlotte Lennox and the Disciplining of the Female Reader Reader discussion on GoodreadsContributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Charlotte Lennox, English Novelist, Playwright, and Poet: An Introduction appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 13, 2021

The Literary Friendship of Poets Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin

Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin were significant twentieth-century poets who provided deep friendship and support for one another as they developed and mastered their craft. Literary Ladies Guide has offered fascinating musings and insights into several significant literary friendships between women writers:

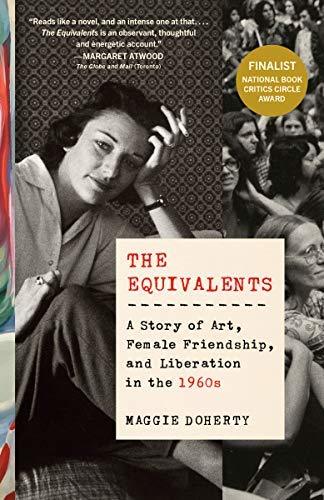

George Eliot and Harriet Beecher Stowe Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West Lillian Hellman and Dorothy Parker Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Zora Neale HurstonBut none of these compare in intensity to the literary friendship of Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin, a relationship brought to life in The Equivalents (2020) by Maggie Doherty, an exploration of the first group of poets and artists to be part of the Institute for Independent Study at Radcliffe College (later the Bunting Institute, and now the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study).

Initial meeting

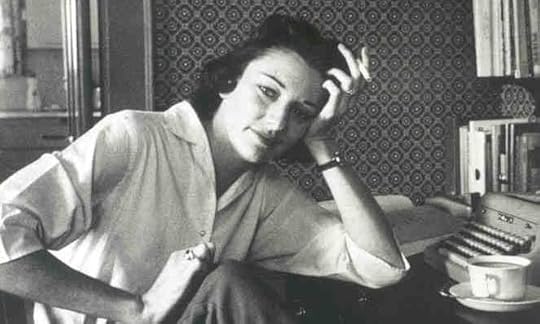

Kumin and Sexton met in 1957 when both women took a poetry workshop at the Boston Center for Adult Education. They had much in common — both were slender, dark-haired, and attractive; both came from upper-middle-class backgrounds; both lived in Newton, a wealthy Boston suburb; and both were married with children.

But the two women also differed in some ways. Sexton had never gone to college and had been told throughout her life that she was “dumb.” She was emotionally fragile. She had attempted suicide the year before and had been institutionalized for mental illness. She began writing poetry after she happened on a public television program called A Sense of Poetry.

Kumin, on the other hand, had earned both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree from Radcliffe College. She “kept her temper in check and steered away from instability,” according to Doherty. She regularly published poetry in outlets such as the Christian Science Monitor, the Wall Street Journal, Ladies’ Home Journal, and the Saturday Evening Post.

. . . . . . . . .

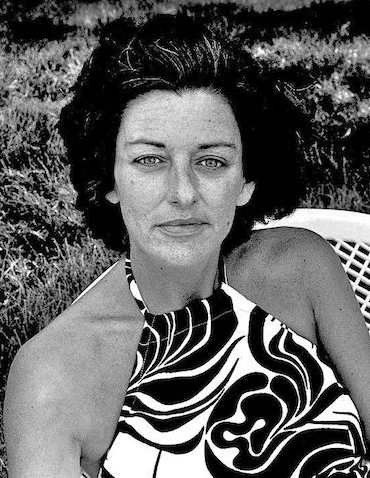

Anne Sexton

. . . . . . . . . .

Her initial reaction to Sexton, who joined the workshop after Kumin had been attending for a while, was a mixture of fear and fascination. And as the weeks progressed and Sexton shared her poems about her suicide attempts and experiences in a mental institution, Kumin was repulsed and decided to avoid Sexton.

Over time, however, convenience overcame her initial disinclination. The two women lived near one another, and it was practical for them to commute to the Boston workshop in the same car. The conversations during the drive broke down Kumin’s dislike. Soon the two saw each other often, attending and sharing impressions of readings by poets such as Marianne Moore and Robert Graves.

They turned to one another between workshop sessions to discuss their own writing as well. One of them would call the other, read a couple of lines, and wait for feedback. As their children demanded attention, the two women struggled to focus on one another’s work. Sometimes they left the phone line open for hours as they worked and took turns reading to one another.

Their differences inspired one another and deepened their writing: Doherty writes that Kumin “offered Sexton the knowledge she’d gleaned from college, and Sexton showed Kumin how to write from a place of feeling rather than thought.”

The Radcliffe Institute

Kumin and Sexton’s friendship was well established by November of 1960, when the latter read about the plan to form a new institute at Radcliffe, the women’s college of Harvard University, in the Sunday paper.

Intended as a center for “intellectually displaced women” the institute was meant to revive the intellectual lives of women who had achieved advanced degrees “or the equivalent” success in the arts but whose careers had been side-tracked by domestic responsibilities. Women chosen for the program would receive workspace, access to Harvard’s resources, and a stipend.

By then, Sexton had published her first book of poetry, To Bedlam and Part Way Back. She and Kumin both applied to be among the first group of scholars and artists. When Kumin received her acceptance letter, she immediately called Sexton to celebrate. Sexton shared her friend’s delight, but when she checked her own mail, there was no letter of acceptance.

Crushed, Sexton took to her bed. But three days later, Sexton received her acceptance and ran through the streets of her suburban neighborhood, knocking on doors and announcing, “I got it!” to anyone who answered. Both women were thrilled that they would be sharing the opportunity and the honor of being in the first group of women at the newly formed Institute for Advanced Study when it opened in September 1961.

. . . . . . . .

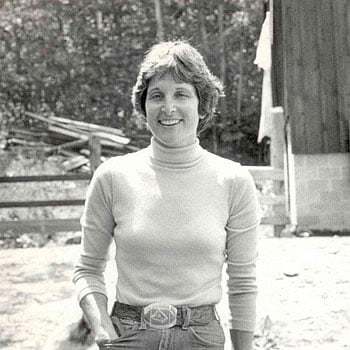

Maxine Kumin (photo: Georgia Litwack)

. . . . . . . .

Over the years, the two poets supported one another’s poetry and collaborated on four children’s books. The daily phone calls continued after the two poets were both fellows at the institute. Both continued to work from their home offices: A typical workday started with a phone call. They often gave each other a series of twenty-minute interludes in which to write or revise a line of poetry before turning to one another for feedback.

They continued in this manner until it was time to make lunch for their children. On warm days, all five children gathered at Sexton’s backyard pool. The two mothers dangled their feet in the water and passed a portable typewriter back and forth as they worked on a children’s book.

Kumin and Sexton gave the first seminar for the group of twenty-four women who comprised the initial class at the Radcliffe Institute. They had promised to read from their poems and discuss their composition process.

Typically, Kumin was calm and well-prepared, having written out her planned remarks. Sexton, on the other hand, was anxious. A natural performer, she would rely on instinct and impulse. By agreement, the two women had kept their collaborative working style (the daily phone calls, the close feedback) secret.

They worried that others might try to turn their collaboration into a rivalry or would doubt the authenticity of their work. But when someone in the audience asked Sexton how she knew a poem was finished, Sexton confessed: “I call up Maxine and I ask her.” She went on to explain that she and Kumin had known each other for years and described their daily phone calls.

The secret collaboration was a secret no more, and the scholars were charmed by the revelation. It was, after all, exactly the sort of supportive relationship the institute had been created to foster.

. . . . . . . . .

The Equivalents on Bookshop.org*

The Equivalents on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

When Sexton and Kumin met in the poetry workshop, people saw Kumin as Sexton’s teacher. Kumin and Sexton saw her that way, too. Kumin’s education and success in publishing made her the more advanced poet at the time that they met. But as the years passed, Sexton became the better-known writer. She published a book before Kumin did.

Both women were awarded a second year at the Radcliffe Institute, and Sexton published a second collection, All My Pretty Ones, in 1962. In 1963, in the final month of her second year at the Institute, Sexton received a traveling fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the first of its kind. In 1967, Sexton won a Pulitzer Prize for her book Live or Die. There was now no thought of Kumin as Sexton’s teacher. Kumin never craved fame the way Sexton did, so the latter’s success posed no threat to their friendship.

In 1973, Sexton was on the Pulitzer Prize committee and argued vehemently to award the prize to Kumin for her fourth book, Up Country, an honor that many saw as overdue. As a past recipient of the award, Sexton knew well how the prize would affect her friend’s career. Once Kumin won the Pulitzer, she was in demand — invited to speak around the country, hired to teach at Columbia University, profiled in magazines.

Kumin had become a professional poet in an industry she referred to as “PoBiz.” She and Sexton stayed in constant telephone contact but saw each other less frequently as professional demands took her away from Newton.

Emotional needs

The two women were essential to each other’s creative and intellectual development, but Sexton’s needs were emotional as well. When Sexton set off for Europe after winning her traveling fellowship, she felt unanchored and adrift and relied on Kumin’s letters to calm her manic and unstable moods.

In 1973, following Kumin’s Pulitzer, Sexton got divorced. Sexton had initiated the dissolution of her marriage, but she came to regret the decision. In March of 1974, Sexton called Kumin and said she was sitting in front of a pile of pills and planned to keep taking them until both she and the pills were gone.

Kumin rushed over to Sexton’s house and drove her to the emergency room. Sexton was furious, but Kumin said, “If you’re going to telegraph your intentions, you don’t give me any choice.”

It was not by any means a one-way relationship. Kumin needed Sexton’s friendship. Doherty says she “needed Sexton to shake her up and pull her out of her proper, reserved self.”

But Kumin’s needs and friendship were not enough to sustain Sexton. In the months following her March attempt, Kumin believed her friend seemed “healed,” but in October of the same year, after what seemed like an ordinary lunch with Kumin, Sexton drove home and committed suicide by sitting in her idling car in her closed garage.

. . . . . . . . . .

10 Poems by Anne Sexton, Confessional Poet

. . . . . . . . . .

After an initial statement in the aftermath of Sexton’s death, Kumin refused to speak about her friend. “I carried Anne’s death in my pocket,” she wrote to one friend, but she couldn’t help but resent the many messages she received from fans, friends, and acquaintances of Sexton and herself.

The bombardment infringed on her efforts to grieve her friend. She was especially angered by Tillie Olsen’s notes implying that Kumin had failed to be an “active sworn enemy” of Sexton’s suicidal thoughts.

Eventually, she was able to write a foreword to Sexton’s Complete Poems, published in 1981, in which she recalled their early friendship and the evolution of Sexton’s art and its role: “Before there was a Women’s Movement, the underground river was already flowing, carrying such diverse cargoes as the poems of Bogan, Levertov, Rukeyser, Swenson, Plath, Rich, and Sexton.” Kumin did not name herself, of course.

After Sexton’s death, Kumin and her husband moved to their house in rural New Hampshire. Kumin continued to write prose, fiction, children’s books, and especially poetry until her death in 2014. She won numerous awards and was named poetry consultant for the Library of Congress (a position now known as the U.S. poet laureate position).

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, she has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Literary Friendship of Poets Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 8, 2021

How to Create Memorable Characters (with Inspiration from Classic Novels)

Characters are the lifeblood of your creative writing, and you want them to power your stories to the end. Here you’ll find some actionable tips on how to create memorable characters for your fictional works, with a few case studies of famous literary heroines to guide and inspire you.

While the world you create in your fictional works is important, readers are more likely to remember the characters that populate it. Indeed, a well-developed central character (or characters) will stay with readers long after they’ve turned the final page.

Strong characters are a must if you want people to stay invested in your story! After all, if readers don’t care about the characters themselves, why should they care what those characters do or say?

. . . . . . . . . .

Allow your characters to be flawed

A perfect character is hardly a relatable one, and unrelatable characters are destined to be shunted to the side and forgotten. To create complex and believable characters your readers will root for, you need to incorporate some character flaws.

Not only do flaws intrigue readers from the get-go, but they also make for a much more dramatic and exciting story, as they demonstrate that your protagonist isn’t invincible.

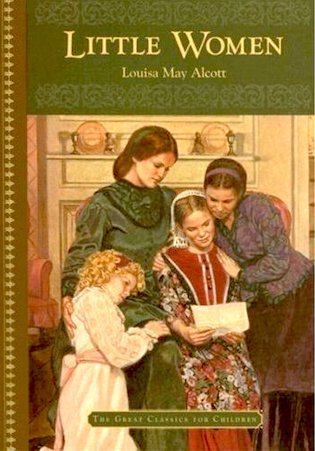

Louisa May Alcott‘s most beloved character, Jo March of Little Women is a classic example of a beloved heroine who has plenty of human foibles. While there’s much to love about Jo — her ambition, her drive, her bravery — it’s her less-than-lovable traits that make her a well-rounded and realistic character. Her quick temper and propensity for bluntness are natural extensions of her more admirable traits, creating a balanced personality that’s grounded in believability.

Jo’s flaws also leave space for conflicts with her close friends and family that are crucial to the plot and the development of her character. Thanks to her flaws, Jo is a real person, and we want her to succeed all the more because of it.

. . . . . . . . . .

Give your characters real agency

Many authors approach creative writing from a plot-driven perspective: they establish the story’s sequence of events first, then build outwards from this spine by fleshing it out with characters and settings. This can be a useful way to shape a story, but one potential pitfall is the creation of characters who are perfunctory, rather than real actors in your tale.

If a character has no say in how the story unfolds, it can create a sense of predetermination — and not in the fun, magical prophecy kind of way, but rather in the “if the course of events is already fixed, why am I bothering to read on?” way.

It will seem as if the story’s simply happening to the character, a passive non-participant in its events. Strong characters aren’t like that — rather, they impact the world around them by making choices with real consequences, producing the kind of genuine, nail-biting stakes that readers love.

While the ending of Charlotte Brontë‘s Jane Eyre is often criticized for its deus ex machina-style resolution, Jane is nevertheless a classic example of a character who makes their own decisions and whose actions have weight in the plot.

Her willful nature and spiritual strength drive her to leave Mr. Rochester and refuse to marry St. John, twice going against the life path seemingly laid out for her — and significantly rerouting the plot. Though it may not always seem like it, Jane is a character who makes choices in line with her own desires, rather than merely being along for the ride.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Allow the plot to affect the characters

It might seem counterintuitive to follow up my last tip with this one, but even active characters with agency should still be affected by what happens around them. If you want your character to feel true to life, they shouldn’t be impervious to the events of the story, but rather responsive to their environment and experiences.

Indeed, when faced with new situations, a character might even choose to be different from before. This can be an excellent way to create satisfying character arcs over the course of your story.

One character who is clearly impacted by narrative events in powerful, realistic ways is Gone With the Wind’s Scarlett O’Hara. The devastation of the Civil War and her family’s subsequent financial ruin provoke a notable shift in Scarlett’s character: she becomes more mercenary and desperate, hardening as a person and going to more extreme lengths to protect and provide for her family. Margaret Mitchell allows readers get to witness her change in direct response to the altered circumstances of her life, making her story and arc feel far more authentic.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Have your characters self-reflect

You may have a well-defined sense of your character’s mindset and personality, but have you ever thought about what the character thinks of themselves? Considering this might be where you strike gold in terms of character development. Your hero or heroine doesn’t need to be preternaturally self-aware, but some level of self-reflection (even only on occasion) adds another dimension to them and brings the reader closer to their psyche.

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway is a masterclass in building a believable psychological world. The eponymous protagonist is constantly grappling with the disconnect between what she wants and what is expected of her. She reflects on her past and the choices she’s made, and constantly questions her happiness. This psychological drama gives readers insight into Mrs. Dalloway as she moves through an otherwise regular day in her life.

. . . . . . . . . .

Challenge expectations

One important lesson every writer must learn is to resist adhering to stereotypes, subconsciously or not. And while you don’t want characters who subvert expectations in superficial, ineffective ways (we’ve probably had enough “not-like-other-girls” heroines to last several lifetimes), it’s helpful to be aware of what readers have been conditioned to expect.

Then, rather than conforming to these expectations, you can attempt to create characters that challenge them — whether they’re aware they’re doing so or not.

One great example of a literary heroine going against type is Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple. In a genre dominated by fictional men (including Christie’s own iconic Hercule Poirot), this female detective allowed the author to explore a brand-new space. Miss Marple also challenged the “spinster” image of unhappy, even bitter, unmarried women that had dominated (and still dominates) the media.

Miss Marple frequently uses the tendency of people to underestimate her to utmost advantage; Christie doesn’t ignore societal expectations and constraints on her characters, but plays with them, highlighting how they can be turned on their heads.

Ultimately, the secret to writing good characters is making sure they engage with the world around them (and our own) in interesting, thoughtful ways. Armed with these tips, and with these examples of remarkable literary women by your side, you’ll soon be creating characters so vivid they practically leap off the page.

Contributed by Savannah Cordova, a writer with Reedsy, a marketplace that connects indie authors with the world’s best publishing professionals. In her spare time, Savannah enjoys reading fiction and writing short stories.

See more writing advice inspired by classic women authors here on Literary Ladies Guide.

The post How to Create Memorable Characters (with Inspiration from Classic Novels) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

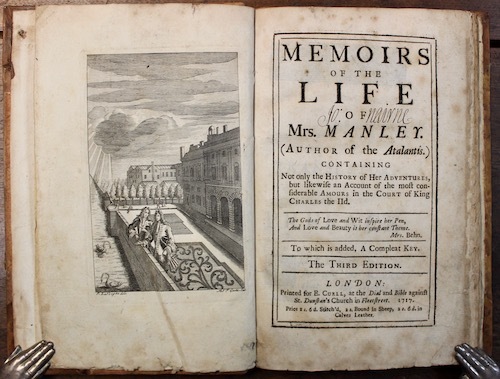

The New Atalantis by Delarivier Manley (1709)

Many women authors have been criticized and even ostracized for their writing but very few have been arrested for it. The New Atalantis by Delarivier Manley (1709) was considered so scandalous that its publisher, printer and author were all arrested for scandalum magnatum.

This introduction to the best-known work by Delarivier Manley (1663 – 1724) is excerpted from Killing the Angel: Early Transgressive British Woman Writers by Francis Booth ©2021, reprinted by permission.

Manley herself considered that it was her gender that most upset the censors; in the follow-up book The Adventures of Rivella, 1714, she says, very much as Aphra Behn had said earlier:

‘If she had been a Man, she had been without Fault: But the Charter of that Sex being much more confined than ours, what is not a Crime in Men is scandalous and unpardonable in Woman.’

The New Atalantis was partly a thinly disguised autobiography but, like the earlier, equally scandalous Urania by Mary Wroth, was mainly a scalding, scathing attack on contemporary society, aimed at the corrupt courtiers, politicians and aristocrats of the time, transgressing any idea of the woman writer as only concerned with romance and manners.

Like Urania, New Atalantis is a kind of early roman à clef, where the names of real people are replaced by fictitious ones, which is why Lady Mary Wortley Montagu told her friend she believed she could find the Key. The central character is Astrea (you may remember that Astrea was Aphra Behn’s pseudonym; this was a deliberate homage on Manley’s part). She is a semi-divine woman who comes back down to earth and meets characters called Virtue and Intelligence, rather as Christine of Pizan met Reason, Rectitude and Justice.

‘Once upon a time, Astrea (who had long since abandoned this world, and flown to her native residence above) by a new formed design, and a revolution of thought, was willing to revisit the earth, to see if humankind was still as defective, as when she in a disgust forsook it.’

. . . . . . . . . . .

Killing the Angel on Amazon US*

Killing the Angel on Amazon UK*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Astrea doesn’t like what she finds as she is guided round the world by her mother, Virtue. Between them, they rail at the corruption around them. Here they are discussing the corruption in the navy.

If some great good man should stand up and fearlessly regulate these disorders, as is reported there is now such a one at their head; if corruptions were not above, these inconveniences would not be below. Did only service and true merit recommend to office; were not bribery, and the solicitations of friends, preferred to duty and worth: were severe penalties inflicted upon these blasphemers (the commanders themselves first is a listing from the use): were dice, cards, and an exorbitant love of wine, and the hotter liquors taxed: were faithful commissioners appointed to inspect the provision of the Navy: were matter of lawful complaint made free to the meanest seamen, provided (upon pain of exemplary punishment) he advance nothing but the truth: were it made capital to take a bribe in the service of their country – the regulation might be made easy, if the leading men and commanders gave them but examples of sobriety, justice and morality. But all is nothing but oaths, drunkenness, burning lust, riots, avarice, cruelty, and disorder; they have got the better of a bad reputation, and do not so much as care to dissemble a good.

Manley was involved in a circle of women writers that included Aphra Behn, Catherine Trotter and Katherine Philips; Manley even provided a poem for Trotter’s play version of Behn’s Agnes de Castro in praise of her predecessors and women poets in general. (Orinda is Philips’ pseudonym, Astrea is Behn’s.)

Orinda and the fair Astrea gone

Not one was found to fill the Vacant Throne:

Aspiring Man quite regained the Sway,

Again had taught us humbly to obey;

Till you (Nature’s third start, in favour of our Kind)

With stronger Arms, their Empire have disjoined,

And snatched a laurel which they thought their Prize,

Thus Conqueror, with your Wit, as with your Eyes.

Fired by their bold Example, I would try

To turn our Sexes weaker Destiny.

O! How I long in the Poetic Race,

To loose the Reins, and give their Glory Chase;

For thus encouraged, and thus led by you?

Methinks we might more Crowns than theirs Subdue.

Manley was probably the editor of a collection of poems on the death of Poet Laureate John Dryden in 1700, including one by Sarah Fyge Egerton. The two women were friends, though their politics were very different, and their friendship ended when Egerton gave evidence against Manley in a forgery trial.

The Dryden memorial volume The Nine Muses also included poems by Trotter and Susanna Centlivre. But despite her admiration for and solidarity with her fellow female authors in The New Atalantis Manley satirizes all these women – the attacks hidden behind fictional names of course.

Her spite was partly due to their Whig politics – Manley was a fervent Tory – but also for what she saw as various betrayals of her friendship; women can be scolds to each other as much as to men. Manley seems however to have been entirely in favor of Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea and reprints two of her poems, complete but unattributed, in The New Atalantis.

Delarivier Manley was highly prolific in many areas, including political journalism, pamphlets and magazines – she briefly edited Jonathan Swift’s Tory journal the Examiner – as well as plays and novels, most of which were what we now call scandal novels, the English equivalent of the French chroniques scandaleuses. Manley’s own life was indeed quite scandalous: she entered into a bigamous marriage with her cousin (which is why her maiden name and her married name are the same).

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

After that failed, she came under the patronage of Charles II’s mistress Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland. That relationship failed too and thereafter she supported herself by her writing; she was another early professional female writer though she insisted throughout her life that she never received enough financial recompense for her writing on behalf of the state.

Most of her political writings were published anonymously but Manley never attempted to hide her many affairs and indeed featured them extensively in her fiction which is mostly at least semi-autobiographical.

Her affairs seem to have been mostly heterosexual, although she moved in circles where lesbian relationships were not uncommon. The New Atalantis, which of course is not entirely fictional, heavily features the Cabal, a group of upper-class women, many of whom are in various artistic fields, who reject family and heterosexual relationships. They tend to dress as men: ‘they do not in reality love Men; but dote of the Representation of Men in Women. Hence it is that those Ladies are so fond of the Dress En Cavaliere.’

This kind of crossdressing society was very unusual in England, though much later in France there were female to male cross dressers like George Sand, the female societies that Colette described so vividly, the Monocle club in Paris and salons like that around Natalie Clifford Barney.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

5 Early English Women Writers to Discover

Elizabeth Cary, Early English Poet, Dramatist, and Scholar

The Matchless Orinda: Katherine Philips

The Scandalous, Sexually Explicit Writings of Aphra Behn

Olympe de Gouges: An Introduction

Susanna Centlivre, English Poet and Playwright

. . . . . . . . . . .

The women of the Cabal in The New Atalantis do occasionally have affairs with men which are indulged as temporary lapses by the other members; their main aim is of a higher kind of friendship between women, transcending the merely physical. Nevertheless, physical love between women is by no means considered shameful within the ranks of the Cabal if not in the rest of society.

Two beautiful Ladies joined in an Excess of Amity (no word is tender enough to express their new Delight) innocently embrace! for how can they be guilty? They vow eternal Tenderness, they exclude the Men, and condition that they will always do. What irregularity can there be in this? ‘Tis true, some things may be strained a little too far, and that causes Reflections to be cast upon the Rest.

Manley’s narrator, Astrea, is not a member of the Cabal and does not entirely approve; for Astrea friendship between women is perfectly acceptable as long as it does not lead to anything physical:

But if they carry it a length beyond what Nature designed and fortify themselves by these new-formed Amities against the Hymenial Union, or give their Husbands but a second place in their Affections and Cares; ‘tis wrong and to be blamed.

Even Manley is not so transgressive as to suggest that women should neglect their duty as wives.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The New Atalantis by Delarivier Manley (1709) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 7, 2021

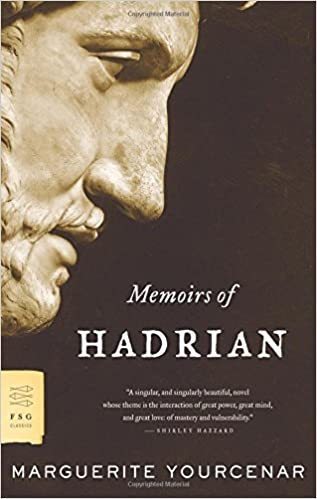

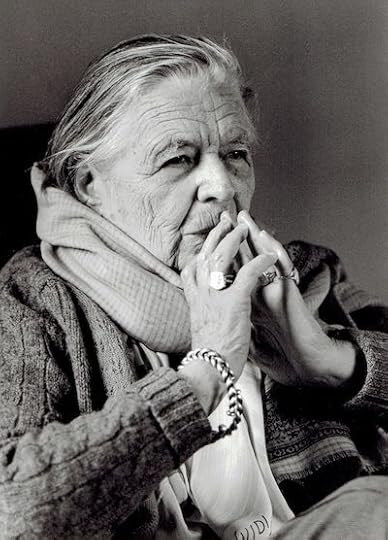

Marguerite Yourcenar, Author of Memoirs of Hadrian

Marguerite Antoinette Jeanne Marie Ghislaine Cleenewerck de Crayencour (June 8, 1903 – December 17, 1987) was a French short story writer, novelist and essayist known as Marguerite Yourcenar. Best known for her novel Memoirs of Hadrian, she was the first woman to be elected to the Académie Française.

From the beginning of World War II, she lived in the United States with her partner, the American professor Grace Frick. She took American citizenship and died in Maine at the age of eighty-four.

A nomadic childhood

Marguerite was the child of a Belgian mother, Fernande de Cartier de Marchienne, and a French father, Michel-René Cleenewerck de Crayencour. The family lived in Brussels, Belgium, where Marguerite was born at home. Ten days after her birth (which Marguerite later described with characteristic unsentimentality: “the pretty room looked like the scene of a crime”), her mother died from puerperal fever.

Not long afterward, her father took her to his family estate near Lille, France, where she lived until the age of nine. She remembered these as largely happy years, with nature on the doorstep, a pet lamb and goat that she adored, and a devoted nursemaid called Barbe.

According to Marguerite’s first biographer Josyane Savigneau, she later scandalized French readers by claiming that she never regretted not having a mother. Barbe, together with her loving but largely absent father, was a good enough substitute — at least until Barbe was sacked for taking Marguerite with her to ‘houses of assignation,’ where she went to supplement her income. It was a shock for the young Marguerite, who was not even allowed to say goodbye. After this, her father sold the family château and moved the two of them to Paris.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Michel was a man of leisure and a prolific gambler, who was very rarely at home. Marguerite was mostly left to fend for herself in the city, wandering the streets and visiting museums and bookstalls. She was educated sporadically at home with a succession of tutors, but it was through her own reading that she became proficient in Latin, ancient Greek, English, and Italian.

This self-styled education was augmented by extensive travel with her father: in a later interview, she recalled several months lived in Richmond, near London, when she would spend days walking in the park or visiting the London museums. “I saw the Elgin Marbles at the British museum. and went to the Victoria and Albert frequently. I used to drop my sweet wrappings in a porcelain dragon there…”

She anticipated a literary career and was encouraged in this by Michel. They moved to Monte Carlo in 1920 so that he could further indulge his love of baccarat, and Marguerite recalled reading English and French classics together in the heat of the Riviera, passing the books back and forth between them.

It was Michel who helped her work out the pen name of Yourcenar (an imperfect anagram of Crayencour), who wrote to publishers under her name to submit her writings, and who paid for her first two books of poetry to be published. He also gave her the first chapter of an unfinished novel of his own, telling her to do what she wanted with it: the result was “The First Evening,” a short story about a joyless wedding night.

A writing career and a tangled personal life

Michel died in 1929, having gambled away much of his fortune and leaving Marguerite nothing. She did, however, have a small inheritance from her mother, which she used to support a continuation of their nomadic and dissipated lifestyle. She drank a little, traveled a lot, slept with both men and women, and wrote prolifically.

Later, she said that everything she ever wrote was already in her mind by the age of twenty; all that remained was for her to polish her method and put the words onto paper. “Books,” she claimed, “are not life, only its ashes.”

It was during this period, then, that she refined the style that would become her own: a classical style that was considered old-fashioned, with a lack of sentimentality and deep psychological insights, that drew comparisons with Racine.

Her first novel, Alexis, was published not long after her father’s death in 1929, followed by Denier du Rêve (translated as A Coin In Nine Hands) in 1934. Her work was largely well-received, although critics tended to comment that she wrote like a man: one wrote that her words were “clasped by an iron gauntlet,” and that he could not find in her work “those often charming weaknesses … by which one identifies a feminine pen.”

Marguerite’s personal life was no less colorful. During this period, she fell for her homosexual editor at Éditions Grasset, André Fraigneau, who loved her intellectually but had no interest sexually.

Her passion for him, though, lasted for several years and overlapped the start of what would be a lifelong relationship with American English professor Grace Frick. The two women met in the bar of the Wagram Hotel in Paris in 1937, where Marguerite was drinking with a friend and discussing the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Grace, so the story goes, overheard their conversation; she walked over to Marguerite’s table and proceeded to correct them on aspects of Coleridge that she felt they had misunderstood.

It could have been an inauspicious start to a relationship, but later that year Marguerite sailed to the U.S. to spend the winter in New Haven with Grace, who was working on her dissertation at Yale. On returning to France in the spring, Marguerite faced a choice between her unrequited love for Fraigneau and her blossoming passion for Grace, which was very much reciprocated.

The short novel Le Coup de Grâce was largely a product of this situation (the storyline involves a love triangle between two Prussian soldiers, Erich and Conrad, and Conrad’s sister Sophie).

Shortly after the novel was published in 1939, Marguerite returned to the U.S. Later, she claimed that she only planned to spend another winter with Grace, but the war prevented her from returning and by the time it was over she had decided to stay. For the next forty years, Grace Frick would be her secretary, translator, manager, lover, and companion.

For the first few years in the U.S., Marguerite found herself unable to write. She turned to teaching instead: she and Grace lived near Hartford in order to be near to Grace’s work at Hartford Junior College and Connecticut College, and Marguerite commuted to teach French and Italian at Sarah Lawrence, just outside New York.

. . . . . . . . . .

Marguerite Yourcenar page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

In 1949, a trunk of possessions belatedly arrived from Lausanne, Switzerland, where Marguerite had stored them when she left Europe at the outbreak of war. Most of the valuables were missing and all that was left were old papers, most of which she burned. While sorting through them, she came across a draft of a novel about the Emperor Hadrian that she had started when she was twenty-one and later abandoned. At that moment, she later said, her mind “more or less exploded.”

In a state of “controlled delirium,” she wrote Memoirs of Hadrian from this early draft in two years. It was a formidable feat considering the amount of research it entailed. There were seventeen pages of bibliographical sources appended to the novel, including histories in English, French, and German, archaeological treatises, and ancient Latin texts — plus the time to physically write the book.

Published in 1951, Memoirs of Hadrian was her first big success, but it was a book that she did not think she could have written when she was younger. “There are books,” she said later, “which one should not attempt before having passed the age of forty.”

She regarded historical novels generally as, “merely a more or less successful costume ball,” and believed that recapturing the spirit of the past required rigorous and detailed research, alongside a kind of spiritual identification that was hard to pinpoint. She described her own historical writing as the “passionate reconstitution, at once detailed and free, of a moment or a man out of the past.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Marguerite Yourcenar in 1982, photo by Bernhard De Grendel

. . . . . . . . . .

Writing success, and life in MaineDuring the 1950s and 1960s, Marguerite wrote several critical essays, many of them linked to her research on Hadrian, and collected them in The Dark Brain of Piranesi and Other Essays (1962). Here, as with Memoirs of Hadrian, the extent of her reading and self-directed learning is apparent. The essays deal with subjects as wide-ranging as Constantine Cavafy and Michelangelo, the venerable Bede, and James Joyce.

Her main project during the 1960s was another novel. The Abyss, published in 1968, is an imaginary biography of a 16th-century scholar and alchemist, and although it is another historical novel the tone is very different from that of Memoirs of Hadrian. Marguerite felt closer to the main character Zeno than she had ever felt to Hadrian, and described him as a brother to her: once, she even recollected ‘leaving’ him at a bakery, and having to go back to collect him. Like Memoirs of Hadrian, the novel was a great success.

Much of this writing work was done at Marguerite and Grace’s house on Mount Desert Island, Maine; an old weatherboarded house that they called Petite Plaisance. Moving here entailed giving up their teaching jobs in Hartford and New York, but Marguerite was busy writing and Grace soon took over everything else, including translating Marguerite’s work into English.

Marguerite spoke fluent English, and translated several English and American novels, including Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, into French herself, but refused to write in English; she remained devoted to her native French tongue until she died. At Petite Plaisance, they would sit facing each other across a large custom-made table in the study, surrounded by books, writing, and translating together.

But life in this isolated part of the world was not easy. Marguerite developed cancer in 1958, and fought it, on and off, for the next twenty years. She still had a passion for travel, a pursuit that was curtailed more and more by her illness.

Unable to visit Europe or other parts of the U.S., as she had been used to doing, she found herself feeling trapped and bored, and her relationship with Grace suffered as a result. When Grace died, also suffering from cancer, in 1979, Marguerite took up the nomadic lifestyle of her younger years and never lived in Maine again. With the final love of her life, a twenty-nine-year-old American photographer called Jerry Wilson (she was seventy-four when their relationship began), she traveled to Europe, Asia and Africa.

French honors, and later years

In 1980 Marguerite was elected to the Académie Française, an exclusive French literary institution that had existed since 1685 without ever including a woman in its number, and to which nomination and election required French citizenship. Marguerite had taken American citizenship in 1949. To get around the problem, the president of France granted her a dual U.S.-French status in 1979.

It was a huge honor that didn’t escape the media, and the attention surrounding her election prompted a resurgence of interest in her early works, none of which had yet been translated. She was happy, after some revision, for most of this work to be published, but none of it (in the critics’ view, at least) measured up to Memoirs of Hadrian or The Abyss.

Despite the recognition of her achievements, Marguerite never really settled to writing again. Her last big project, a three-volume biography of her family entitled Le Labyrinthe du Monde, was never completed.

While packing for a trip to Europe, she suffered a stroke and was taken to hospital. She never recovered and died the night of December 17, 1987. She was buried next to Grace in Somesville, across the sound from Petite Plaisance, with a memorial marker alongside for Jerry Wilson, who died of AIDS in 1986.

Her obituary in the New York Times described her as a “cosmopolitan, versatile woman of letters,” and President Jacques Chirac said that “French letters has just lost an exceptional woman…[who] used a very personal tone to find, thanks to history, the occasion for a strong reflection on morality and power.”

Petite Plaisance is now a museum, and home to a conservation fund for the maintenance of the building.

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is an author, poet, and artist with a serious case of wanderlust. She is originally from the UK, but has spent time abroad in Europe, the United States and the Bahamas.

When not traveling or working on her current projects — a chapbook of poetry, “The Cabinet of Lost Things,” and a novel based on the life of modernist writer and illustrator Djuna Barnes — she can be found with her nose in a book, daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Visit her on the web at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Marguerite YourcenarMany of Yourcenar’s works are still only available in French, although some of her essays and short stories have been posthumously translated and collected. See her full bibliography here.

Selected works available in English

The Abyss (1982)That Mighty Sculptor, Time (1992)A Blue Tale and Other Stories (1995)Memoirs of Hadrian (2000)Biographies

Marguerite Yourcenar: Inventing a Life by Josyane Savigneau (1993)Marguerite Yourcenar: A Biography by George Rousseau (2004)More information

Wikipedia Becoming the Emperor: How Marguerite Yourcenar Reinvented the Past The Art of Fiction No. 103 on Paris Reviews Reader discussion on Goodreads. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Marguerite Yourcenar, Author of Memoirs of Hadrian appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 6, 2021

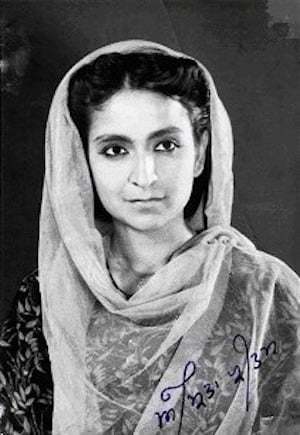

The Revenue Stamp – An Autobiography by Amrita Pritam

Amrita Pritam (1919 – 2005) was a poet, novelist, and essayist, with a huge body of work to her credit. So it’s surprising that her autobiography is just under two hundred pages, and it’s curious why she chose this particular title — The Revenue Stamp.

Behind the name is the exchange between Amrita and the famous author and journalist, Khushwant Singh, who told her that her life was of so little consequence that it could be written on the back of a revenue stamp (‘Raseedi Ticket’ in the original).

When choosing the name for her autobiography, Amrita recalled this banter and opted for this name. Credit must be given to the English translator, Krishna Gorowara, who seems to have picked up on all the nuances and depth of Amrita’s thoughts.

Pritam was born in an area that was then British India, now part of Pakistan. She wrote in Punjabi and Hindi, and her work has long been beloved by readers in both India and Pakistan. The autobiography (first published in 1977; published in English translation in 2015) doesn’t follow a linear style. Rather, it provides wonderful insights into the mind of a woman poet who was far ahead of her time, in both her thinking and how she conducted her life.

The book touches on her life with Imroz, a painter with whom she has a live-in-relationship at a time when such things were far from the norm. Her early marriage to Pritam Singh ends in a divorce. The reasons for their parting and how it affects their two children are covered.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Amrita Pritam

. . . . . . . .

Amrita writes of her parents, Raj Bibi and Kartar Singh. The latter had chosen a life of renunciation as a child Sadhu, but one glance at Raj Bibi changes all that, and they are married. Amrita writes, “The most remarkable thing about father was that a life of riches or renunciation came alike to him.”

When Amrita loses her mother at the age of ten, this sense of renunciation comes to haunt her. She senses that her father is torn between his love for her and a complete withdrawal from life. She writes poignantly that she “used to cry out in anguish because I could not tell whether I was accepted or not. I was both accepted and rejected in turns.”

Amrita’s father dabbles in verse and teaches her about rhyme and rhythm hoping that she will find expression in poetry. Amrita writes, “It seems to me I wrote because I wanted to forget those moments of rejection I felt in him.”

Interestingly, half a century later, Amrita expresses the idea that she has inherited her father’s way of looking at the world, “I feel that both riches and renunciations have taken twin births in me as well.” She also states the philosophy that stays with her throughout, “I am not in the least mindful of what others think of me. My only desire is to be at peace with my innermost self.”

After her mother’s death, Amrita loses her interest in religion, feeling that all her prayers didn’t serve to keep her mother alive. Still, spiritual experiences do come into her now and then in her later life and she gives expression to them.

Rebellious years and the Partition

Some tidbits from her formative years reveal Amrita’s questioning and rebellious streak. Her grandmother was the reigning matriarch of the kitchen. Amrita’s father aided her in her efforts to revolt against her grandmother’s regime.

One issue arose relating to three glass tumblers that were kept aside to serve buttermilk only to the Muslim visitors to the house. The tumblers became a “cause” for Amrita, who would insist on drinking only from those glasses, with her father’s aid. She writes, “Thereafter not a single utensil in the house was labeled ‘Hindu’ or ‘Muslim.’ She continues, “Neither Grandmother nor I knew then that the man I was to fall in love with, would be of the same faith as the branded utensils were meant for.”

In her sixteenth year, the author starts questioning all the regimentation of her life, her school years, parental authority: “What I had so far learnt was like a straightjacket that gives way at the seams — as the body grows. I was thirsty for life. I wanted living contact with those stars I had been taught to worship from afar.”

Amrita compares this rebellious time of her life with the era of the Partition of Undivided India in 1947, “when all social, political and religious values came crashing down like glass smashed into smithereens from the feet of people in flight.”

For those of us born after the Partition into a free India, Amrita’s autobiography offers heartbreaking insights into what it did to people — families, who found themselves separated, friends who were suddenly expected to be sworn enemies, and saddest of all, women who were abducted and raped and faced untold horrors.

She writes, “The passion of those monstrous times have been with me since, like some consuming fire — when I wrote later of a beloved’s face; of the aggressors from neighboring countries; of the crime of the long Vietnamese night, or, at one stage, of the helpless Czechs … In the haunting image of beauty and in the anger at wrong and cruelty, my sixteenth year stretches on and on …”

Unrequited love and friendships

Amrita writes of her (probably unrequited) love for the Hindi poet and lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi, which the man in her life, Imroz, understood and joked with her about. She says, “The curse of my lonesome state has been broken through — by Imroz.”

She is so candid in her description of how she picked up her habit of smoking. Sahir would visit her and smoke, leaving the cigarette butts behind. After his departure, Amrita would pick up the butts and smoke them, just to feel close to something that had touched Sahir’s lips. She also describes how the character of Sahir makes an appearance in some of her novels.

This is the kind of candidness and honesty that appear time and again in this autobiography, including the instances where she writes about fellow writers and poets. She names those whose writings she enjoys and doesn’t mince words about the pettiness of others who leave her essays out of anthologies, bar her from organizations, or prevent her from being part of poetry delegations that are invited to travel abroad.

A section called ‘The Cycle of Hatred’ details all this. One also gets an idea of the trials and tribulations of a woman writer, in a world of men wishing to dominate the writing world.

Her friendship with a Pakistani poet, Sajjad, whom she has known before the Partition, results in her getting flak for mentioning his name publicly. Sajjad asks her to stop doing so, and she mourns the fact that the Partition left no space for recognition of a friendship.