Nava Atlas's Blog, page 34

October 14, 2021

Misty of Chincoteague (1947)

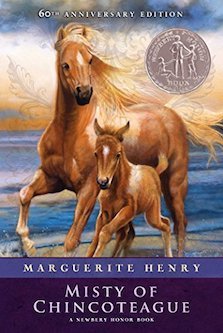

Marguerite Henry (1902–1997) was an American children’s book author who wrote fifty-nine novels based on true stories about horses and other animals. Her famous novel, Misty of Chincoteague (1947) was the first in a series of six stories centered around a wild palomino pony, named Misty.

Set in the island town of Chincoteague, Virginia, Henry’s novel is centered on Misty, her mother (Phantom), Paul Beebe, and Maureen Beebe. While the book is a work of fiction, the story is based on real people and ponies from Chincoteague Island.

In 1948, Henry’s novel received the Newbery Honor Award and went on to become a children’s classic, second only to Black Beauty. The book is a best-seller and has been reprinted over twenty times in hardcover. In 1897, Joan Nichols adapted the story into a series of children’s picture books.

A brief introduction

Misty of Chincoteague tells the story of Paul Beebe and his sister, Maureen, who live with their grandparents, Clarence and Ida Beebe, on Chincoteague Island. Paul and Maureen work on their grandfather’s farm to help him train and breed ponies while always dreaming of having a pony of their own someday.

Finally, after working numerous jobs, Paul and Maureen earn enough money to purchase a pony at the Pony Penning auction. The mare they purchase is named Phantom, and she has escaped the roundup men on Pony Penning Day for two years. Much to everyone’s surprise, Paul captures Phantom and her newborn foal Misty on the roundup.

Paul and Maureen decide to purchase Phantom and Misty at the auction. They spend the next year training Phantom to ride and keeping Misty out of trouble. The following year, Paul rides Phantom in the main race on Pony Penning Day. Phantom wins, but she becomes upset when she sees the herd she used to belong to being released to swim back to Assateague Island. She is released by Paul and gallops to join the herd as they return to their ancestral island in search of freedom, while Misty stays behind with Paul and Maureen.

. . . . . . . . .

Marguerite Henry with the real Misty

. . . . . . . . .

From the Chicago Tribune, November 16, 1947: “A wild, ringing neigh shrilled up from the hold of the Spanish galleon,” and we’re off to a fine start in this beautiful horse story from the talented author-artist combination who gave us Justin Morgan Had a Horse. The neigh came from one of a band of Moor ponies sent to Peru long years ago and shipwrecked off the Virginia coast. Legend has it that the wild ponies who, alone, inhabit Assateague Island today, are their descendants.

This is the story of two children, Paul and Maureen, who lived on their grandpa’s pony ranch on the nearby island of Chincoteague, and whose great desire was to own and tame one of these ponies, a mysterious wild mare names the Phantom, who had never been captured in the annual roundup. By a miracle it fell to Paul this year, on his first roundup ride, to help bring in not only the Phantom but her little colt, which he and Maureen named Misty because in the woods she had seemed like a bit of “white mist with the sun on it.”

The story tells how, after working hard to earn the money to buy both ponies, they almost lost them; how they cared for and trained them to the islanders’ amazement; and how Phantom won a race and was given her freedom. It all makes a fine tale for seven to fourteen-year-olds.

Based on true incidents and people on little-known Chincoteague, stories and pictures race along as light and as free as the wild ponies themselves, and the characters—with a special bow to Grandpa Beebe—are as salty and as real as the island life they lead and the sea air they breathe.”

The real Misty’s hoofprints. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . . .

Marguerite Henry’s inspiration for the novel, Misty of Chincoteague, came from her personal travels to Chincoteague Island to see the annual Pony Roundup and Swim.

Misty was a twelve-hand palomino pinto pony owned by Clarence and Ida Beebe when Henry first met her. At first, Clarence denied Henry’s request to buy Misty from him and take her back home as the model for her new book. After Henry promised Clarence that she would include his grandkids, Paul and Maureen, in her manuscript, Misty was sold for $150 and delivered to Henry after being weaned from Phantom.

Misty remained with Henry for several years and appeared with her at numerous events for fans at schools, museums, and horse shows. Misty passed away in her sleep on October 16, 1972, at age twenty-six. As of 2015, there are two hundred known descendants of Misty.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Misty, the first and only cinematic adaptation of Henry’s novel, was released on June 4, 1961. The film was directed by James Clark and written by Ted Sherdeman. Actors David Ladd, Arthur O’Connell, and Pam Smith starred in the film.

With a budget of $705,000, this 20th Century Fox film remains the same family classic it was in 1961 when it was one of the highest-grossing non-Disney family films of the year. On Rotten Tomatoes, 63 percent of audience members awarded it a 3.7 out of 5 rating, while a top critic called it a “faithful adaptation of the iconic children’s book.”

The majority of the movie was shot on the islands of Chincoteague and Assateague. While the events of Misty of Chincoteague are depicted in the film, Misty herself was not in the film, as she was too old to play the role of a young foal.

Misty did, however, make an appearance at the Island Theater in Chincoteague, VA, where she left her front hoofprints in cement in front of the theater’s entrance when the film initially premiered. Her hoofprints are still visible on the sidewalk today, where Henry inscribed Misty’s name in the cement beneath them.

. . . . . . . . . .

Miss Molly’s Inn at Chincoteague. Photo: Mistysheaven.com

. . . . . . . . . . .

After their deaths, Misty and her foal Stormy were taxidermized and put on display at the Museum of Chincoteague Island. They are the centerpieces of the display on Misty, which also includes artifacts and memorabilia from the Beebe Ranch.

Each year, there is still a Pony Penning Day and an auction in Chincoteague, VA. It takes place in July and attracts approximately 50,000 visitors who come to watch the ponies swim across the channel and parade down the street to the pony pens. You can even stay at Miss Molly’s Inn in Chincoteague, VA, where Henry penned part of her novel.

The time capsule buried alongside Misty’s statue at the Kentucky Horse Park in Lexington, Kentucky, will be opened on the 100th anniversary of her birth in 2046.

. . . . . . . . . .

Misty of Chincoteague on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Here is a brief selection of quotes from Marguerite Henry’s classic horse novel, Misty of Chincoteague:

“The ponies were exhausted, and their coats were heavy with water, but they were free, free, free!”

. . . . . . . . . .

“‘If you look close,’ he whispered, ‘you can see that wild critters have ‘No Trespassing’ signs tacked up on every pine tree.’”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Facts are fine, far as they go… but they’re like water bugs skittering atop the water. Legends, now — they go deep down and bring up the heart of a story.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“With Phantom and Misty things happened the other way around. Misty accepted human beings right from the start. Their hands felt good to her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“The roundup, the discovery of Misty, the swim across the channel-they all melted into this. The moments rushed on. The storm quieted.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Maureen saw Misty stretched out at her mother’s feet. Her heart warmed at the sight of them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“When they could eat no more, they pawed shallow wells with their hooves for drinking water. Then they rolled in the wiry grass, letting out great whinnies of happiness. They seemed unable to believe that the island was all their own. Not a human anywhere. Only grass. And sea. And the wind.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“This was it! This was the exciting smell that had urged them on. With wild snorts of happiness, they buried their noses in the long grass. They bit and tore great mouthfuls- frantically, as if they were afraid it might not last. Oh, the salty goodness of it! Not bitter at all, but juicy-sweet with rain.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Anna Fiore: Anna is a 2021 graduate of SUNY-New Paltz, majoring in Communications, with a concentration in Public Relations and a minor in journalism.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Misty of Chincoteague by Marguerite Henry:

Wikipedia Misty of Chincoteague History of Misty of Chincoteague Visit the Island Home of Misty of Chincoteague. . . . . . . . . .

These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Misty of Chincoteague (1947) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 13, 2021

Jan Morris, Travel Writer and Historian — an Introduction

Jan Morris (October 2, 1926 – November 20, 2020), the historian and travel writer, was born and mostly raised in England, but identified as Welsh. Renowned for the Pax Britannica trilogy, a history of the British Empire, she was also esteemed for her intimate and insightful portraits of several great cities of the world.

Jan published under her birth name, James, before completing her transition to female in 1972. She was one of the first public figures to come out openly as transgender, making her a pioneer to the generations of trans writers (and others) who came after her.

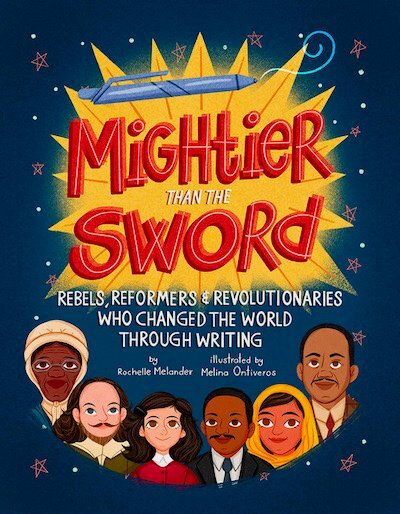

This introduction to the ideas and accomplishments of Jan Morris is excerpted from Mightier Than the Sword; Rebels, Reformers, and Revolutionaries Who Changed the World Through Writing by Rochelle Melander, illustrated by Melina Ontiveros. Copyright © 2021 Beaming Books. Reproduced by permission.

. . . . . . . . .

Illustration of Jan Morris (and the others in this post)

by Melina Ontiveros

. . . . . . . . .

While Mightier Than the Sword is intended for middle grade, its forty capsule biographies can be enjoyed by readers of any age, in tandem with the lively color illustrations. The book highlights how powerful writing can lead to positive change, encouraging young readers to pick up their own pens and use their voices. Learn more about this book following the excerpt, which starts here:

As a young child, Jan Morris experienced a conundrum. Assigned male and called James at birth, she remembered sitting under the piano while her mother played: “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl.” Jan “cherished this as a secret” for twenty years.

Jan felt different from other children. When her two older brothers left for school, she spent hours by herself wandering the hills around her house, watching ships through her telescope. She wrote:

“The instrument played an important part in my fancies and conjectures, perhaps because it seemed to give me a private insight into distant worlds, and when at the age of eight or nine I wrote the first pages of a book, I called it Travels with a Telescope, not a bad title at that.”

. . . . . . . . .

Mightier Than the Sword is available on Bookshop.org*, Amazon*,

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . .

In her late teens, Jan joined the 9th Queens Royal Lancers and worked as a spy. She never felt at home in the army, thinking of herself as a “stranger and imposter.” But the experience gave her the opportunity to learn how to examine the world around her:

“For myself, I think I learnt my trade largely in the 9th Lancers, for I developed in that regiment an almost anthropological interest in the forms and attitudes of its society; and sitting there undetected, so to speak, I evolved the techniques of analysis and observation that I would later adapt to the writer’s craft.”

After the army, Jan delved into reporting. In 1953, The Times assigned her to cover Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay as they attempted to be the first to summit Mount Everest, the world’s highest mountain. Jan climbed thousands of feet above base camp so that when the explorers reached the top, she could race to the bottom and phone in the scoop.

In 1956, Jan received a fellowship to travel and write. She visited every state in the United States and wrote the book, Coast to Coast. She went on to write about many more places, including The World of Venice (1960) and The Presence of Spain (1965). Jan became known for portraying the personality of places, describing their characteristics with rich language.

As Jan tackled one of her biggest professional projects, a three-volume history of the British Empire, she also explored her lifelong conundrum. Because how she felt on the inside (her gender identity) didn’t match the sex she was assigned at birth, Jan’s feeling of being born in the wrong body never left her.

. . . . . . . . . .

She described gender as being “the essentialness of oneself.” And as long as she lived as a man, she felt out of sync with herself. At this time, Jan began transitioning from male to female. She chronicled this process in her book, Conundrum:

“To myself I had been a woman all along, and I was not going to change the truth of me, only discard the falsity. … I embarked upon it only with a sense of thankfulness, like a lost traveler finding the right road at last.”

Jan wrote for the rest of her life, publishing more than 40 books. She answered all of her mail and penned encouraging notes to aspiring writers: “Don’t worry about rejection slips, everyone gets them. Experience everything.”

Contributed by Rochelle Melander: Rochelle is a speaker, a professional certified coach, and the founder of Dream Keepers, a writing workshop that encourages young people to write about their lives and dreams for the future. Rochelle wrote her first book at seven and has published eleven books for adults. Mightier Than the Sword is her debut book for children. She lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Visit her at Write Now Coach.

Other trans writers who came after Jan Morris

Raquel Willis

. . . . . . . . . . .

Throughout history, people have picked up their pens and wielded their words—transforming their lives, their communities, and beyond. Now it’s your turn! Representing a diverse range of backgrounds and experiences, Mightier Than the Sword connects over forty inspiring biographies with life-changing writing activities and tips, showing readers just how much their own words can make a difference.

Readers will explore nature with Rachel Carson, experience the beginning of the Reformation with Martin Luther, champion women’s rights with Sojourner Truth, and many more.

These richly illustrated stories of inspiring speechmakers, scientists, explorers, authors, poets, activists, and even other kids and young adults will engage and encourage young people to pay attention to their world, to honor their own ideas and dreams, and to embrace the transformative power of words to bring good to the world.

Sources and more information

Conundrum by Jan Morris (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) “Experience Everything” by Simon Winchester (American Scholar, December 5, 2020)“Jan Morris: The Art of the Essay, No. 2” (The Paris Review, Issue 143, Summer 1997). . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

See more fascinating literary musings on this site.

The post Jan Morris, Travel Writer and Historian — an Introduction appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 8, 2021

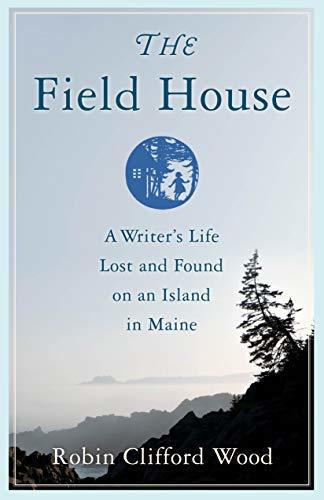

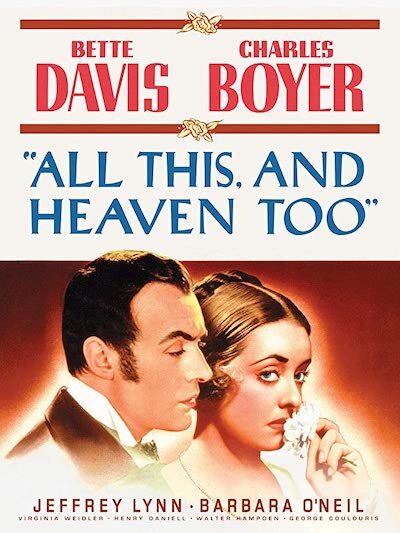

All This, and Heaven Too by Rachel Field (1938)

All This, and Heaven Too is the evocative title of Rachel Field’s 1938 historical novel, based on the life of her great-aunt Henriette Deluzy Desportes. Though she passed away prematurely, Field manage to produce a prodigious array of works in several genres, including children’s books (notably the award-winning Hitty: Her First Hundred Years), poetry, plays, and novels.

If the title seems familiar, it may be in part thanks to the widely praised 1940 film of the same name starring Bette Davis in the role of the novel’s heroine.

Originally published by the Macmillan Company, The Chicago Review Press republished the book in 2003, some years after it had fallen into relative obscurity. Here’s a brief description from the later edition:

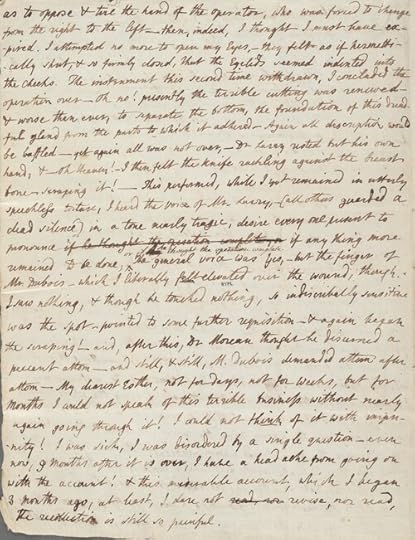

“This number-one bestselling novel is based on the true story of one of the most notorious murder cases in French history. The heroine, Henriette Deluzy-Desportes, governess to the children of the Duc de Praslin, found herself strangely drawn to her employer; when the Duc murdered his wife in the most savage fashion, she had to plead her own case before the Chancellor of France in a sensational murder trial that helped bring down the French king.

After winning her freedom, Henriette took refuge in America, where she hosted a salon visited by all the socialites of New York and New England. This thrilling historical romance, full of passion, mystery, and intrigue, has laid claim to the hearts and minds of readers for generations.”

The first portion of the novel takes place in France and details the years that Henriette spent in the Praslin household as the beloved governess of the younger of the Duc and Duchess’s nine children. In exquisitely wrought prose, it richly imagines life in the upper echelons of early 19th-century Paris. Henriette grows accustomed to the comforts of such a life, even as an employee, but never forgets the straitened circumstances from which she rose.

After the Duc murders his wife and takes his own life, Henriette’s fall from grace is complete, but she never loses her dignity and devotion to the truth. What makes the novel all the more remarkable is that Field recreated real-life events with such skill and managed to maintain suspense in the retelling of a historical event A quick peek at the Duc of Praslin’s Wikipedia page confirms the story’s basis in real life events. Even Henriette Deluzy Desportes merits her own Wikipedia page, because the sensational case led, indirectly, to the second French Revolution of 1948.

Henriette was fortunate enough to gain passage to the U.S. as a way to escape her notoriety (though it couldn’t help but follow her). The devoted Henry Martyn Field, some ten years Henriette’s junior (they never had children of their own), was a scion of an established family from Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Both Henriette and Rachel Field, the great-niece who authored this book, are laid to rest there.

The first two-thirds or so of All This, and Heaven Too, read like a great 19th-century novel. The narrative offers rich detail and drama, without being overwrought. The final third, however, once she and Mr. Field are happily married and ensconced in Stockbridge, I found to be incredibly anticlimactic. This is unsurprising, since the climax and denouement happen before Henriette leaves France. I would have preferred the last one hundred fifty or so of the nearly six hundred pages to have been condensed into an epilogue.

Still, this is a book worthy of a place as a mid-twentieth century classic, with a nod to its author, Rachel Field, who deserves to be read and remembered much more than she is today. All This, and Heaven Too received nearly universal praise when it was published in 1938; here are two typical reviews from the period.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Rachel Field in this biography/memoir by Robin Clifford Wood

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat (St. Louis, Missouri) sat, Oct 22, 1938: The adage that truth is stranger than fiction dares to be is strikingly illustrated in Rachel Field’s new novel. The historical basis of her story is the notorious Praslin murder in France in 1847, a crime which not only filled the newspapers of both continents at the time and inspired several books, but which had repercussions on the throne of France.

However, the cold skeleton of historical truth alone does not make a great novel. It must be imbued with the warm, glowing flesh of life, and in doing this Miss Field presents the portrait of’ a remarkable woman—Henriette Deluzy Desportes. Henriette is impressive, both in fiction and in real life.

She was the great-aunt of the author by marriage, and this is the story of her life. She was a woman of warm personal charm and she possessed the quiet courage and the serenity of character to survive the “transplanting of a life uprooted from obscurity by an avalanche of passion and violence and class hatred.”

Henriette’s story, like her life, is divided into two parts. The first, and by far, the most dramatic, is the story of Mademoiselle Deluzy, the governess in the ill-fated household of the Duc and Duchesse de Praslin. Through no fault of her own she is drawn into the web of scandal which culminates in the slaying of the Duchesse and the nightmare of inquisition and prejudice which followed.

To give reality and contemporaneousness to the past is not an easy task, add it is a tribute to Miss Field’s skill that the reader never has the impression of merely listening to a story, but shares with Henriette her thoughts and emotions during those trying years.

The second half of the story tells of Henriette’s flight to America to escape the notoriety which beat about her ears in France, and of her adjustment to a new and strange world. Before she left France she met Henry Field, a young minister and the brother of Cyrus Field, who laid the Atlantic cable. After a year of teaching in a New York girls’ school, she married him.

Miss Field reveals with sympathetic insight the love story of this unusual Frenchwoman and her New England husband who was ten years her junior. In the years that follow we meet many of the well-known figure of that period, William Cullen Bryant, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Fanny Kemble, Peter Cooper, and Rachel, the noted French tragedienne. The story carries Henriette’s life down to shortly before her death in 1875.

All This, and Heaven, Too is in many respects Miss Field’s best work. It is projected on a much broader canvas than Time Out of Mind and tells a far more dramatic story. Its only weakness is

that the climax comes in the middle of the book, but this doesn’t break the continuity of the story. It has the same sense of intimacy of her previous work and reveals in even more impressive fashion her skill in character delineation.

. . . . . . . . . .

All This, and Heaven Too on Amazon*

All This, and Heaven Too on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

From The Kansas City Star, October 22, 1938: Rachel Field’s great-aunt Henriette Desportes was a favorite of the men during her eventful life. She had much less success winning feminine sympathy in her Victorian period. Now preserved brilliantly in print, she undoubtedly will command admiring attention from both men and women. She deserves a place up front among the 19th-century heroines in American fiction.

Her story makes one of the best novels of 1938, a book that contains all the ingredients required of a bestseller, yet one that possesses genuine literary merit.

Henriette Desportes was a real person, a figure in a great scandal that shook the French empire in 1847. After that, she came to the United States and was married to Henry M. Field, a New England minister who was editor of a religious periodical in New York. In her later years, Henriette was a figure in literary New York.

Painstaking historical research went into the making of this book. In choosing to cast Henriette’s story in the form of a novel, the author created large difficulties for herself — problems of plot, structural organization, continuity, and characterization. She has mastered them all, producing a vivid period piece, an arresting character study, and a narrative that maintains suspense and sustained interest.

The scandal in which Henriette was involved is the tragedy of the Duc and Duchesse of Praslin. The story begins as Henriette is hired as governess of the younger children of the unhappy couple, in their lavish home. Did the Doc finally kill his jealous, mentally unbalanced wife? Though he has concocted an alibi, he also poisons himself and slowly dies.

Henriette, whose name has been linked with that of the Duc in malicious gossip, is arrested as an instigator of the crime. The case becomes one of the most talked-about national scandals in the agitated days before the second French Revolution of 1848.

The sensational murder inquiry, in which Henriette wins her freedom through her courage and eloquence, is a dramatic high point that serves as the climax of this unusual woman’s life in France. It is the stormy prelude to the richly serene years of Henriette’s life in the United States. Seeking refuge in obscurity, she comes to this country as a teacher and finds a useful place for herself as the wife of Henry M. Field, an American minister who had first met her on a visit to Paris.

Miss Field has told each of the two contrasting parts of Henriette’s story with equal facility. The first part is a detailed, intimate account of the maturing of a young woman cast in a strange situation. Tempted by the love of a charming nobleman whose home she has become indispensable, threatened by the jealousy of the Duc’s wife, she is a warmhearted and steadfast figure.

In the last part of the book, she is a sensitive yet sensible woman making a success of life with Henry Field, the man she loves, taking part in the intellectual growth of the country. Both parts of the portrait fit together, showing the fair face of courage, self-reliance, dignity, warm human feeling, and joy in the good things of life.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Stream the 1940 film adaptation on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post All This, and Heaven Too by Rachel Field (1938) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 6, 2021

Remembering the What Katy Did Series by Susan Coolidge

There are some books from one’s schoolgirl years that stay with you, and the What Katy Did series by Susan Coolidge (1835–1905) certainly falls into that category for me. I read and re-read those books through many vacations. Before realizing it, the actions of favorite characters begin to have an effect on me, as the reader.

The American author of the What Katy Did series (five books in all) was born Sarah Chauncey Woolsey but gained fame with her pen name, Susan Coolidge. The first book of her Katy Did series was published in 1872.

What Katy Did deals with the adventures of twelve-year-old Katy Carr, who lives with her Aunt Izzie (after having lost her mother at the age of five), her father, Dr. Carr (a hardworking doctor, who is away from home for long spells), three sisters, and two brothers. Her friend, Cecy, also plays an important role in the first novel.

A typical gangly and gauche tomboyMany twelve-year-olds would most likely identify with Katy at that age — a gangly tomboy who manages to tear her dresses regularly and resents the very idea of being told to be “a good little girl,” by Aunt Izzie when she is actually dreaming about doing “something grand.”

Of course, she is also full of self-doubt about being gauche in appearance and feeling unloved. This preoccupation with not looking good is probably part of growing pains but when you think back, you wonder whether the regular descriptions about people’s looks could be internalized by preteens.

To the despair of Aunt Izzie, Katy is always tearing about the place and getting into fights with her siblings or her friend, Cecy, even as she cooks up wild games for them all to play. All this undergoes a change when Katy falls off a swing and suffers a spinal injury, with the possibility of being laid up in bed for the rest of her life.

Enter Cousin Helen

Here’s where my favorite character, Katy’s Cousin Helen, enters the picture and turns out to be a great emotional bulwark. Herself an invalid who uses a wheelchair, Cousin Helen is the embodiment of kindness and good cheer and helps Katy negotiate her condition and come to terms with it by attending the “School of Pain.”

There is a transference of Cousin Helen’s sweetness to Katy, and much as one might identify with the naughty Katy, even as a young reader, it’s natural to feel admiration for Cousin Helen’s goodness in the face of adversity. This could well be the dichotomy of human nature, which wants to break free of constraints and expectations, and at the same time embrace altruism and goodness.

Fortunately, Katy recovers from her injury, and towards the end of this book becomes all that Aunt Izzie wishes her to be. The fire of imagination hasn’t left her, but she is no longer at loggerheads with her siblings. She is a calmer person, more capable around the house. A nineteenth-century writer of stories for young girls can’t be faulted for ending a story on a note of conformity, because that was the expected outcome for those times.

What Katy Did at School

The second of the series, What Katy Did at School (1873), follows the still high-spirited Katy through her time at a New England boarding school. There, she and her sister, Clover, get used to making a slew of new friends, participating in schoolgirl capers, and confronting issues of ethics. Katy has to face unjust accusations and learn how to deal with them.

The letters from home and constant reference to their large family help Katy and Clover handle some rough times. Moral lessons come into play, but are handled in a way that holds the attention of young adults. The story moves forward with notions of what young women of those times were expected to be, but the author manages to hold the interest of later generations of readers nevertheless.

What Katy Did Next

The final book in the series, What Katy Did Next (1886) becomes a lot more exciting, as a widowed friend of the family, Mrs. Polly Ashe, invites Katy to join her for a vacation to Europe as a traveling companion for herself and her daughter, Little Polly.

Reluctant at first to leave her large family behind, Katy, now twenty-one, is persuaded by her father to make the trip, and Dr. Carr gives her three hundred dollars for her travel expenses. Before her travels, Katy makes a stop at Boston where all the girls from the school at Hillsover have a grand reunion. Soon after, it’s time for departure to England, accompanied by a bout of seasickness.

The sights and sounds of Europe make for interesting reading, as also the discovery that “good weather” in England means the absence of rain and that the muffins that sound so scrumptious in the Dickens’ novels are disappointing when actually tasted.

This is the book in which Katy discovers the true love of her life, Mrs. Ashe’s brother. He must have been a memorable character, as I was surprised that so many years after reading the book, I could still recall his name, Ned Worthington.

Supposedly, the Katy Did series was modeled on Coolidge’s own (Woolsey) family, with Katy inspired by Susan herself, lending the stories their magic. The Little Carrs were based on the characters of her four siblings. The family house in Cleveland, Ohio, is said to have provided the setting for the home of the Carrs in the first book.

Many readers have identified with Katy Carr, perhaps explaining why this series may still be attracting the attention of an international audience of young readers.

. . . . . . . . .

The complete Katy series on bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

More about the What Katy Did seriesTwo related books about Katy’s younger siblings followed the trilogy of What Katy Did books. These were Clover and In the High Valley.

Ongoing book, film, and television adaptations have kept this series before readers’ (and viewers’) eyes, long after the original books were published. The first adaptation for media was the 8-part UK series aired in 1962. Katy (1972) was the first feature film adaptation, made and released in the UK as well. What Katy Did was a 1999 American film starring the versatile actress Alison Pill.

Katy by Jacqueline Wilson (2015) is a contemporary retelling in book form. This, in turn, became a British television adaptation that aired in 2017.

Susan Chauncey Woolsey, writing as Susan Coolidge, is by far best remembered for the What Katy Did series. But she was an incredibly prolific author of works for children, including novels, short stories, and poems. Here is a complete listing of her works.

Wikipedia Full text of What Katy Did at Project Gutenberg Reader discussion on Goodreads Listen to What Katy Did on Librivox. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Remembering the What Katy Did Series by Susan Coolidge appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 4, 2021

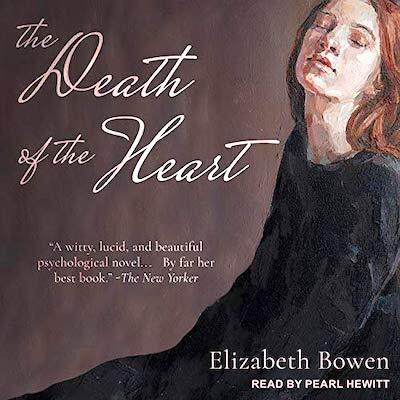

Orphaned Unostentation: The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen

The Death of the Heart (1938) by Elizabeth Bowen is in many ways a traditional English 1930s novel, and a comedy of manners — the manners of pre-war, upper-middle-class London which Bowen (1899 – 1973) knew well. This analysis of The Death of the Heart is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

The Death of the Heart is a coming-of-age novel, and its heroine, Portia Quayne, undoubtedly belongs in the literary realm of adolescent girls and their sexual experiences.

Portia does, in her way, come of age in the course of the story though she does not have the novel to herself. She is just one of a cast of unappealing characters examined in forensic detail by the witty, sardonic, and ruthless Bowen in this darkly witty chamber piece.

Among her many novels, Bowen had already included girls as central characters in at least two others: The House in Paris (1926) is about a day in the life of eleven-year-old Henrietta Mountjoy — not a long enough period to see Henrietta coming of age –—and one of the major characters in The Last September (1929) is eighteen-year-old Lois Farquar, whose coming of age is just one of the stories in this vast, sweeping novel about an upper-class family during the Anglo-Irish troubles of the time.

Portia Quayne

Sixteen-year-old Portia Quayne is a recent orphan and is being brought up, like Jane Eyre, Fanny Price (of Mansfield Park), and other girls in coming of age novels, by unsympathetic relatives who make it clear that they do not want her. These girls are still better off than the likes of an orphaned and abandoned Fanny Hill or Moll Flanders with only their virtue left to sell.

After Portia’s mother has died, she has been sent to live with her much older half-brother Thomas and his snobbish wife Anna in their stylish central London home. Thomas’s father had much earlier left his mother for a woman of a much lower social class, who then gave birth to Portia; the father then died and Portia continued to live with her feckless mother, moving around and living in cheap hotels. Thomas and Anna have no children of their own and Anna clearly does not want Portia cluttering up her pristine house.

Portia’s only ally is the older female servant Matchett, who was in service with her and Thomas’s father and was left to Thomas in his father’s will, like a chattel, along with ‘the furniture that had always been her charge.’ Portia seems to realize that she is in the house but not of it; even though she is hardly a mousy Cinderella/Jane Eyre character she tries to make herself as unnoticed as possible with her ‘orphaned unostentation’.

“Getting up from the stool carefully, Portia returned her cup and plate to the tray. Then, holding herself so erect that she quivered, taking long soft steps on the balls of her feet, and at the same time with an orphaned unostentation, she started making towards the door. She moved crabwise, as though the others were royalty, never quite turning her back on them – and there, waiting for her to be quite gone, watched …

Her body was all concave and jerkily fluid lines; it moved with sensitive looseness, loosely threaded together: each movement had a touch of exaggeration, as though some secret power kept springing out. At the same time she looked cautious, aware of the world in which she had to live. She was sixteen, losing her childish majesty.”

Portia’s diary

As the novel opens Portia is being discussed by Anna and her friend, the novelist St. Quentin. Anna has recently found Portia’s diary in which she has written about her host and hostess – it is not that Portia has written unkindly that has upset Anna, just the fact that she has written about her at all. Anna claims that she was not looking for the diary or searching Portia’s room, just entering to hang up a dress that had come back from the cleaners.

Her room looked, as I’ve learnt to expect, shocking: she has all sorts of arrangements Matchett will never touch. You know what some servants are – how they ride one down, and at the same time make all sorts of allowance for temperament in children or animals.’

‘You would call her a child?’

‘In many ways, she is more like an animal. I made that room so pretty before she came. I had no idea how blindly she was going to live. Now I hardly ever going there; it’s simply discouraging.’

. . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

Portia is, by any normal standard, a polite, intelligent, and respectful girl but by the standards of Anna’s finicky fastidiousness Portia is a rogue element in her otherwise immaculate house; especially in the way she keeps her room. ‘I really did feel it was time I took a line. But she and I are on such curious terms – when I ever do take a line, she never knows what it is. She is so unnaturally callous about objects – she treats any hat, for instance, like an old envelope.’

Anna has given Portia a ‘little escritoire thing’ that had been Thomas’s mother’s with locking drawers, hoping it ‘would make her see that I quite meant her to have a life of her own.’ The symbolism of this object seems to be lost on Portia. ‘Nothing that’s hers ever seems, if you know what I mean, to belong to her.’ Anna should not be surprised at this, as Portia has grown up moving around from one hotel to another.

One of the things that has most upset Anna about Portia’s diary is the quality of the book it is written in: unlike several of the diary-keepers in Girls in Bloom, Portia does not write in a beautiful leather journal but ‘One of those wretched black books one buys for about a shilling with moiré outsides.’ Anna is clearly horrified to have such a seedy object in her house, but she has never liked Portia – or her late mother, who may have been pregnant with Portia when Thomas’s father ran off with her – even before Portia moved in.

‘She’s made nothing but trouble since before she was born.’ St Quentin replies: ‘You mean, it’s a pity she ever was?’ Anna agrees that that is how she feels. Thomas also seems to have resented Portia, and especially her mother, from before her birth. ‘From the grotesqueries of that marriage he had felt a revulsion. Portia, with her suggestion – during those visits – of sacred lurking, had stared at him like a kitten that expects to be drowned.’

St. Quentin’s interest

St. Quentin, as a writer, is interested in the style rather than the content or physical form of Portia’s diary; his dialogue with Anna allows Bowen to have some authorial fun.

‘Was it affected?’

‘Deeply hysterical.’

‘You’ve got to allow for style, though. Nothing arrives on paper as it started, and so much arrives that never started at all. To write is always to rave a little – even if one did once know what one meant, which at her age seems unlikely. There are ways and ways of trumping a thing up: one gets more discriminating, not necessarily more honest. I should know, after all.’

‘I am sure you do, St. Quentin. But this was not a bit like your beautiful books. In fact it was not like writing at all.’ She paused and added: ‘She was so odd about me…’

‘A diary, after all, is written to please oneself – therefore it’s bound to be enormously written up. The obligation to write it is all in one’s own eye, and look how one is when it’s almost always written – upstairs, late, overwrought alone.’

This is, of course, a good point about diaries purporting to have been written by young girls: they are indeed written alone and at night in the privacy of their own room where their thoughts can run free. Bowen has more fun with the idea of diaries as a form of fiction later on in the novel; Portia is talking here to St. Quentin.

‘Now what can have made me think you kept a diary? Now that I come to look at you, I don’t think you’d be so rash.’

‘If I kept one, it would be a dead secret. Why should that be rash?’

‘It is madness to write things down.’

‘But you write those books you write almost all day don’t you?’

‘But what’s in them never happened – it might have, but never did. And though what is felt in them is just possible – in fact, it’s much more possible, in an unnerving way, than most people will admit – it’s fairly improbable. So, you see, it’s my game from the start. But I should never write what had happened down… I dare say,’ said St. Quentin kindly, ‘that what you write is quite silly, but all the same, you are taking a liberty. You set traps for us. You ruin our free will.’

‘I write what has happened. I don’t invent.’

‘You put constructions on things. You are a most dangerous girl.’

Writing, of course, is about the most dangerous thing woman can do.

A school for “delicate girls”

Like Rosamond Lehmann’s heroines, Portia does not go to a normal school but attends a small, special private institution for ‘delicate girls, girls who did not do well at school, girls putting in time before they went abroad, girls who were not to go abroad at all.’ But this seems to be quite an intellectual finishing school, not one designed to turn out dim, obedient, marriageable girls.

According to Portia’s diary, a typical day is: ‘today we began Sienese Art, and did Book Keeping, and read a German play.’ She has only one friend there: Lilian, whom Anna does not think ‘very desirable, but this could not be helped.’

Lillian ‘walks about with the rather fated expression you see in photographs of girls who have subsequently been murdered,’ after she had ‘had to be taken away from her boarding school because of falling in love with the cello mistress, which had made her quite unable to eat.’

Although ten years later than Lehmann’s Dusty Answer, this is one of the first coming-of-age novels to explicitly mention lesbianism, though not in relation to the principal character and only in relation to a schoolgirl crush on a teacher.

Portia does not do well at the school, she cannot concentrate, cannot ‘keep her thoughts at face-and-table level; they would go soaring up through the glass dome.’ Because of her upbringing so far, Portia is ‘unused to learning, she had not learnt that one must learn.’ She is also socially out of place with all these future debutantes; while they had been learning art, languages and social graces, Portia and her mother Irene:

‘… had been skidding about in an out-of-season nowhere of railway stations and rocks, filing off wet third-class decks of lake steamers, choking over the bones of loups de mer, giggling into eiderdowns that smelled of the person-before-last. Untaught, they had walked arm-in-arm along city pavements, and at nights had pulled their beds closer together or slept in the same bed overcoming, as far as might be, the separation of birth. Seldom had they faced up to society.’

But now, Portia must face up, alone and motherless, to not only society, but older male attention; Anna is entirely incapable of acting in loco parentis. Anna’s shiftless friend Eddie, like an impecunious and disrespectable member of Bertie Wooster’s Drones Club, and the slightly seedy, older hanger-on Major Brutt both seem to have feelings for her, though neither of them seems particularly eager to turn them into physical form.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Death of the Heart on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

At first, it seems that Portia has set her cap squarely at Eddie. ‘Portia’s life, up to now, had been all subtle gentle compliance, but she had been compliant without pity. Now she saw with pity, but without reproaching herself, all the sacrificed people — Major Brutt, Lilian, Matchett, even Anna – that she had stepped over to meet Eddie.’

Eddie refuses to let her write about him in her diary, but she tells him that, now she has him, she may not need the diary anymore. Nevertheless, she still writes down thoughts and deeds, some of which Bowen gives us, in a style not entirely unlike that of her friend Virginia Woolf.

But things with Eddie do not work out: he is not the settling down type. ‘I used to think that we understood each other. I still think you’re sweet, though you do give me the horrors. I feel you’re trying to put me into some sort of trap. I’d never dream of going to bed with you, the idea would be absurd.’

Towards the end of the novel, on the rebound from Eddie, as it were, Portia tries to give her virgin self to the Major, who has been sending her presents of jigsaw puzzles. She visits him at his down-at-heel hotel and proposes marriage to him. ‘I could cook; my mother cooked when we lived in Notting Hill Gate. Why could you not marry me? I could cheer you up. I would not get in your way, and we should not be half so lonely… Do think it over, please,’ says Portia calmly.

With a quite new, matter-of-fact air of possessing his room, she made small arrangements for comfort – peeled off his eiderdown, kicked her shoes off, lay down with her head in his pillow and pulled the eiderdown snugly up to her chin. By this series of acts she seemed at once to shelter, to plant here, and to obliterate herself – most of all the last… ‘I suppose,’ she said, after some minutes, ‘you don’t know what to do.’

But the Major turns out to be a confirmed bachelor – though not necessarily in the sense that ‘confirmed bachelor’ was used in those days to connote homosexuality. She looks at the rows of his military-shiny shoes and offers to clean them for him. ‘For some reason, women are never so good at it.’ He picks up the brushes and begins to clean the shoes himself.

Portia, watching him, had all in that moment a view of his untouched masculine privacy, of that grave abstractedness with which each part of his toilet would go on being performed. Unconscious, he could not have made plainer his determination to always live alone. Clapping the brushes together, he put them down with a clatter that made them both start. ‘I’m sure you will cook,’ he said, ‘I’m all in favour of it. But not for some years yet, and not, I’m afraid, for me.’

And that is that; Portia returns ‘home.’ But it is only home in the sense of Philip Larkin’s famous definition: ‘home is where, when you have to go there, they have to let you in.’

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Orphaned Unostentation: The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 1, 2021

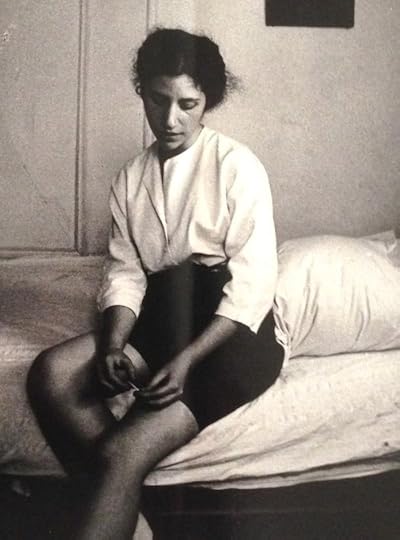

Diane di Prima, Beat Generation Poet

The extraordinary feminist and Beat generation poet Diane di Prima (August 6, 1934 – October 5, 2020) was an active participant in the cultural and political movements of the last half of the twentieth century. She embodied the awareness of a poet’s sensibility required for these political fights to evolve. Photo at right: Estate of Diane di Prima.

Di Prima wrote the poem following when she was named as the San Francisco Poet Laureate in 2009. In eight seemingly simple lines, she brings the credo of her life’s visionary work:

my vow is:

to remind us all

to celebrate

there is no time

too desperate

no season

that is not

a Season of Song

(from “First Draft: Poet Laureate Oath of Office,” 2009)

On October 25, 2020, in her beloved adopted hometown of San Francisco, di Prima passed away with her husband, family, and friends at her bedside. She was eighty-six years old and had been in assisted living for the past two years.

Despite her physical struggles, di Prima continued to write every day and had several book projects in the works. It would be hard to accept that her gritty and tough poetic voice would now be silent — with her heart in every word, after creating fifty books and chapbooks of poetry over nearly sixty years.

Childhood and formative years

Diane Rose di Prima was born on August 6, 1934 in Brooklyn, New York. She grew up in the Italian-American neighborhood of Carrol Gardens, the oldest child of Frank di Prima, a lawyer, and his wife Emma, a schoolteacher.

In Di Prima’s 2003 memoir, Recollections of My Life as a Woman, the reader notices the dominant influence of her maternal grandparents, Domenico and Antoinette Mazzolli. Domenico was an anarchist and an Italian immigrant who worked as a tailor; his friends and colleagues included fellow anarchists Emma Goldman and Carlo Tresca.

Today is your

birthday and I have tried

writing these things before,

but now

in the gathering madness, I want to

thank you

for telling me what to expect

for pulling

no punches, back there in that scrubbed Bronx parlor.

(from “April Fool Birthday Poem for Grandpa”)

Di Prima remembers back to the time when she was three to four years old and her grandfather, Domenico, shared a secret from the family: they would spend long hours listening to Italian opera — a treat that was forbidden to Domenico. Italian opera, with its sorrows and its vicissitudes of its heroes and heroines, had his doctors warning him that his bad heart may give out from the emotional strain of the opera.

Domenico was a popular anarchist speaker; di Prima remembered one of those speeches, when “the arts shine down on us, the leaves glow in the electric lights of the park. I am proud of him, and afraid, but mostly amazed. His words have awakened my full acknowledgment, consent, I hear what he says as truth, and I seem to have always known it.”

Di Prima’s grandmother, Antoinette, shared a grand passion with Domenico but also imparted sound advice to the young Diane that yes, men may be considered special, but women can survive without them.

“My Grandmother’s Catholicism was of the distinctive Mediterranean variety: tolerant and full of humor. ‘Eh!’ my Grandmother would say, ‘The Virgin Mary is a woman, she’ll explain it to God.’ It indicated on one hand, the Virgin Mary knew much better than God the ins and outs human nature, what we were up to, and that she had a tolerance and intelligence and humor that was perhaps missing from the male godhead.”

It was a comfortable home; di Prima went to the Parochial school in her neighborhood and helped her younger brothers with their homework. When it came time for her to choose a high school, she took the exam for the prestigious Hunter College High School in Manhattan and broke the record for the highest score on the written test.

Di Prima and a group of seven other students (including the brilliant poet Audre Lorde) had formed a poetry circle: young women sharing their work and dedicating themselves to the art of the written word. At fifteen years old, di Prima made her commitment to her life’s destiny known: she would spend her life being a poet.

“Seeing a life of striving, possibility of living within a vision … I know I will be a poet, and knowing that knowing what I will lose. Keats said it: I am certain of nothing, but the holiness of the Heart’s Affections and the Truth of the Imagination,” she wrote of her revelation during adolescence. She drew on the strength of her maternal grandparents’ political anarchist ideals and their passion for art, decided to risk everything and write.

. . . . . . . . .

Diane di Prima in 1959, photo by James Oliver Mitchell

. . . . . . . . .

When it came time to consider college, di Prima entered a New York City competition for excellence in Latin and earned a scholarship to the prestigious Swarthmore University. Di Prima had decided to study physics, but after three semesters, she dropped out and became an integral part of the Greenwich Village literary scene that dominated the late 1950s and 1960s.

Di Prima rented a flat for thirty-three dollars a month and became friends with Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Frank O’Hara, and Denise Levertov. She became a co-founder of the Poets Press and the New York Poets Theatre and co-editor of the literary magazine The Floating Bear.

“She was important as the feminist voice of the Beat generation,” said Lawrence Ferlinghetti, co-founder of San Francisco’s City Lights Bookstore. Di Prima wrote about “the equality of the sexes,” fellow poet and close friend Amber Tamblyn wrote in The New Yorker, “She saw herself as a weapon to be deployed — no, detonated — against her oppressors. She wrote about women as wolves, women as predators, as hunters, as villains. She wrote about fat women, queer women, androgynous women, disobedient women, women as Gods, as birds, as the wind.”

I have just realized that the stakes are myself

I have no other ransom money, nothing to break or barter but my life

my spirit measured out, in bits, spread over

the roulette table, I recoup what I can

(from “Revolutionary Letter #1”)

San Francisco

In 1968, di Prima packed up her four children and settled in San Francisco. This time she settled into a fourteen-room flat on the corner of Laguna and Page. The location was at the epicenter of the cultural and political awakenings happening in San Francisco in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Di Prima was an active participant in the movements against the Vietnam War, and the fight for civil, labor, immigrant, and LGBTQ rights. As with her writing, Di Prima’s activism never waned.

The value of an individual life a credo they taught us

to instill fear, and inaction, ‘you only live once’

a fog on our eyes, we are

endless as the sea, not separate, we die

a million times a day, we are born

a million times, each breath life and death:

get up. put on your shoes, get

started, someone will finish.

(from “Revolutionary Letter #3”)

Although di Prima had chosen Greenwich Village instead of an academic path, she landed several jobs as a college instructor at The San Francisco Art Institute and the California College of the Arts.

For many years, she would load her children into the family’s truck to teach at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poets with fellow Beats Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, William Burroughs, and Gregory Corso.

Sweetheart

when you break thru

you’ll find

a poet here

not quite what one would choose.

I won’t promise

you’ll never go hungry

that you won’t be sad

on this gutted

breaking

globe

but I can show you

baby

enough to love

to break your heart

forever

(from “Song for Baby-O, Unborn”)

. . . . . . . . . .

Diane di Prima books on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Di Prima’s life was unconventional by conventional standards: light-years removed from the standards of conformity that choked one’s creativity and authenticity. “So much of the woman I am today is because of the woman Diane once was,” Amber Tamblyn remembered.

One of di Prima’s most seminal works is Loba, first published in 1978 as an open-ended poem and as the feminist answer to Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. In 1998, twenty years after its debut, Loba was published again in a more expansive eight-part poem and she finally considered the work complete.

The same creative process happened with Revolutionary Letters. First begun in the 1960s, with portions being published for the next few decades, until 2014 when di Prima completed the book.

In an interview given three years before her death, di Prima spoke of her legacy to her readers as “giving them the courage to change their lives. People get caught in the conventions of society and they forget what they are really after.”

I’d like my daily bread however

you arrange it, and I’d also like

to be bread, or sustenance for

some others even after I’ve left.

(from “The Poetry Deal,” 1993)

Contributed by Nancy Snyder, who writes about women writers and labor women. After working for the City and County of San Francisco for thirty years, she is now learning everything about Henry David Thoreau in Los Angeles.

More about Diane Di PrimaMajor works

Diane di Prima was incredibly prolific, with numerous published collections of her work. See an extensive bibliography here.

Autobiography

Recollections of My Life as a Woman: The New York Years by Diane di PrimaMemoirs of a Beatnik by Diane di Prima (1998)More information and sources

Poetry Foundation Diane di Prima, Poet of the Beat Era and Beyond Dies at 86 (New York Times, October 28, 2020) Diane di Prima, Beat Poet and Activist Dead at 86 (National Public Radio, October 27, 2020) In Memoriam: The Beat Museum The Undying Voice of Diane di Prima by Amber Tamblyn (New Yorker, November 9, year? ) Diane di Prima, Prolific Beat Poet Dead at 86 (San Francisco Chronicle, October 27, 2020) Wikipedia*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Diane di Prima, Beat Generation Poet appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 29, 2021

Contemporary Writers’ Favorite Classic Books by Women Authors

Many of us love classic books, so I thought it would be fascinating to discover a few contemporary writers’ favorite classic books by women authors. Leslie Pietrzyk, Stacy Hawkins Adams, and Kathryn Reid responded with thoughtful answers as well as short biographies.

As a contributor to Literary Ladies Guide, I (Tyler Scott), weigh in as well. When we write, when we read, it’s all about enlarging our circle. This brief survey proves that literature continues to connect us in our shared human experiences.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Leslie Pietrzyk: My Antonia by Willa Cather

“I grew up in Iowa, reading Laura Ingalls Wilder and any book featuring a covered wagon on the cover, so what a thrill when I discovered My Ántonia by Willa Cather as an adult. The story is dark and joyful, nostalgic and horrifying, no-nonsense and filled with a certain yearning unable to be distilled into words … only images.

As a writer, now, I admire that Cather takes a patchwork narrative and the framing device of the manuscript written by Jim — devices that could be hokey or easily botched–and confidently relies on the power of this story, of Antonia herself, to carry the book. After reading My Antonia, I couldn’t rest until I traveled to Willa Cather’s Red Cloud, Nebraska to experience this landscape for myself.”

Leslie Pietrzyk’s collection of linked stories set in DC, Admit This to No One, is forthcoming in November 2021 from Unnamed Press, the publisher of her 2018 novel Silver Girl. Her first collection of short stories, This Angel on My Chest, won the 2015 Drue Heinz Literature Prize and was published by University of Pittsburgh Press.

Her short fiction and essays have appeared in, among others, Ploughshares, Story Magazine, The Hudson Review, Southern Review, The Gettysburg Review, The Sun, and The Washington Post Magazine. Awards include a Pushcart Prize in 2020. Her twitter is @lesliepwriter.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Stacy Hawkins Adams:Homemade Love by J. California Cooper

“One of my favorite authors is a somewhat hidden gem. The late J. California Cooper penned historical fiction, mostly set in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when her Black characters had little agency over their lives yet led richly compelling ones.

Ms. Cooper deftly crafted men, women and children grappling with love, loss, success, failure, striving and setbacks in every work, including In Search of Satisfaction, Family, and Some People, Some Other Place. In doing so, she invited readers to appreciate others’ humanity and to consider that all people deserve to be seen and cherished.

One of my favorites is her collection of short stories titled Homemade Love. This fiction is filled with humor and wisdom and left me rooting for and celebrating the people I met on the page.

I appreciate the richness of Ms. Cooper’s storytelling each time I revisit her fiction; and in addition to reading it for pleasure, I study it to strengthen my own ‘writing muscles.’”

Stacy Hawkins Adams is an award-winning, multi-published author and essayist whose fiction and nonfiction compels readers to find relevance in their own stories.

She has penned women’s fiction nine novels, a nonfiction devotional book and a collection of original quotes. She also curates a blog at www.LifeUntapped.com and presents at writing conferences and book events around the globe.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Kathleen Reid: Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

“I am a huge Jane Austen fan. My favorite story has always been Pride and Prejudice. Austen’s wit and skill at capturing the nuances of the British aristocracy still resonates today. However, Elizabeth Bennet is a strong character who challenges social mores.

Austen reveals the complete powerlessness of women in society and how few choices were available. The need to marry well was paramount. Mr. Darcy was a complex character: curt, sarcastic, and judgmental, yet grounded in a good heart. For me, I always love a happy ending. Many of these themes are incorporated into my novels.

Let me tell you a secret: I wrote a novel called Wild About Wickham from Lydia’s point of view. My literary agent encouraged the idea, but a PR professional told me I could face major repercussions for daring to emulate an icon. It has been sitting in my desk drawer for years”

Kathleen Reid is an award-winning author who has published three works of fiction: Paris Match, A Page Out of Life and Sunrise in Florence. She loves art history and carefully weaves her extensive research into the story lines of her novels. Kathleen writes to inspire, educate and entertain her readers. Sunrise in Florence won three Indie Awards in Romance and Romantic Suspense. Kathleen is a wife, mom of two girls, volunteer, and avid runner. Follow her on Instagram: @readkathleenreid.

. . . . . . . . . .

Tyler Scott: Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

And my favorite book? Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë. The first time I read this classic I was in the eighth grade, and I suspect the book was on my summer reading list. Bronte opened a door for me, and I can still hear the rattling of the horse carriages, the howling winds on the moors, and the cries of those lonely orphans at Lowood School.

What I didn’t realize at the time is the reason this book rings so true is Bronte was writing autobiographically: she had attended a school like Lowood, she had been a governess, and she had spurned proposals. And what adolescent hasn’t felt as lonely and misunderstood as Jane?

Charlotte Brontë was born in Yorkshire in 1816. Her father was a rector and she and her and her brother and four sisters grew up in an isolated village called Haworth, left to their own devices; her mother died from cancer when Charlotte was six years old so she certainly experienced tragedy at a young age.

The Brontës were bright and imaginative children; Charlottes’s surviving sisters, Emily and Anne, are also esteemed novelists and poets. By the age of fifteen, the young Charlotte had written twenty-three “novels.” When Jane Eyre was published in 1847, written under the pen name Currer Bell, the book was dedicated to William Thackeray; he described the novel as “the masterwork of a great genius.”

Jane yearned for “a real knowledge of life” yet she also pushed back at the constraints of Victorian society, not only thinking for herself, but taking action as when she fled Mr. Rochester in spite of her love for him. Eerie Gothic settings, a secret in the attic and a happy ending: I can’t think of a better formula for a beloved novel.

Tyler Scott has been writing essays and articles since the early 1980s for various magazines and newspapers. In 2014 she published her novel The Excellent Advice of a Few Famous Painters.

She lives in Blackstone, Virginia where she and her husband renovated a Queen Anne Revival house and enjoy small town life.

The post Contemporary Writers’ Favorite Classic Books by Women Authors appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 26, 2021

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf (1927)

Virginia Woolf (1882 – 1941) is recognized as one of the most groundbreaking modernist authors of the twentieth century. She is perhaps most widely known for iconic novels like Mrs. Dalloway (1925) and her semi-autobiographical novel, To the Lighthouse (1927).

To the Lighthouse was Woolf’s fifth novel, and has remained one of her most highly regarded works. Inspired by recollections of her childhood summers spent on the Cornwall coast, To the Lighthouse depicts the fictional Ramsey family and their assorted house guests spending a vacation in the Hebrides, on the island of Skye.

The first part of the novel, “The Window,” finds six-year-old James Ramsey eagerly awaiting a promised trip to the nearby lighthouse, a promise not to be fulfilled until ten years later when, in the third section, “The Lighthouse,” James is nearing adulthood and many of the other characters have disappeared.

Time PassesBridging the sections in the book is “Time Passes,” with Woolf’s characteristic stream-of-consciousness technique at its most lyrical and powerful. It’s where we find out what has happened to the missing members of the group. By the close of the novel, reconciliation with the ghosts of the past has been achieved.

Woolf’s distinctive technique enables her to portray the interior lives of the characters and depict the montage-like imprint of memory. The novel includes very little dialogue and action but instead relies upon the thoughts and observations of the characters as the plot unfolds through shifting perspectives of each character’s consciousness.

This startling — and intentionally autobiographical — portrait of the complex inner workings of a family has been hailed as one of the greatest novels of the century. E.M. Forster commented in eulogizing her in 1941 that Woolf had “pushed the light of English language a little further against the darkness.”

. . . . . . . . . .

To the Lighthouse on Bookshop.org* and on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

An original 1927 review of To the LighthouseVirginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, from the Hartford Courant, June 5, 1927: Of all the exponents of what we may term, for convenience’s sake, the formless or fluid school of novelists, Mrs. Woolf is the most reasonable and the most readable; she has perfected her chosen medium into a thing of actual artistic beauty, and many readers find a fine satisfaction in her work. To others, cleverly handled and intelligently executed though it be, Mrs. Woolf’s artistic formula of the novel is disturbing.

To the Lighthouse is, speaking broadly, a character study, divided into three parts: Part I, The Window, fills two-thirds of the book and is entirely devoted to one day in the life of Mrs. Ramsey, and a group of people surrounding her; Part II, called Time Passes, supposedly spans an interval period of ten years and then comes Part III, The Lighthouse, and there again we have the spiritual narrative, so to speak, of a single day—not in the life of Mrs. Ramsey, who is dead, but of many persons whose lives Mrs. Ramsey, consciously or unconsciously, influenced.

Now, this sort of thing is immensely interesting as an experiment in literary technique, in the possibilities of the novel form, but one doubts if it can ever supersede the more conventional form in which the bulk of novels, from the greatest to the least, have been, and now are written. In the last analysis, the ultimate in any phase of art must be selection—it is impossible to reproduce any coherent impression of everything, everywhere, all at once.

In a sense the Window section of To the Lighthouse is like a decent Ulysses, only that Mrs. Woolf keeps her artistic resources properly in hand, she does not let the fluidity of her medium liquify into mere mad incoherence. “The Window” is an attempt to put the reader inside Mrs. Ramsey’s mind, to let him share her thoughts, her shifting glancing impressions, and hear her spoken works. And all this is set in a huge interwoven tapestry of background, and the little household in the Hebrides becomes vividly actual and real.

Yet it is a question whether this probing and delving into the inner consciousness of a given character, gives that character a continuing vital existence in the mind of the reader, such as the men and women in certain books of the older tradition carry with them.

Do we actually know charming, whimsical, keen-witted Mrs. Ramsey, any better through following her thoughts, than we know, for example, Hardy’s Eustacia Vye, who is presented and revealed to us according to the older tradition? It is significant that Mrs. Woolf is forced, at times, to convey bits of pertinent information, necessary to the enlightenment of the reader, in curt, clean-cut sentences which are bracketed. The entirely unforeseen news of Mrs. Ramsey’s death is so imparted.

Mrs. Woolf is an artist, and her artistic manner is interesting, —but after an hour with “To the Lighthouse,” what sheer relief it is to take up, quite at random, a volume of Hardy, or Trollope, or, to be entirely of our own day, if Galsworthy or Sheila Kaye Smith.

Allusions to Woolf’s autobiography

To the Lighthouse suggests many similarities between the plot of the story and Woolf’s own, real life. Despite debilitating battles with mental illness throughout her life, she wrote the novel as a way of dealing with unresolved issues of the past concerning her parents.

Woolf’s sister disclosed parts of the novel were very descriptive of their late mother, who died when Virginia was just thirteen years old. Other parts of the novel emulated traits of Woolf’s father, who, like Mr. Ramsey threw himself into a pit of darkness and despair after the death of his wife.

The primary setting of the story on Hebridean Island was also inspired by Woolf’s summer home in St. Ives, where she and her family regularly went on holiday until Virginia was ten years old.

. . . . . . . . . .

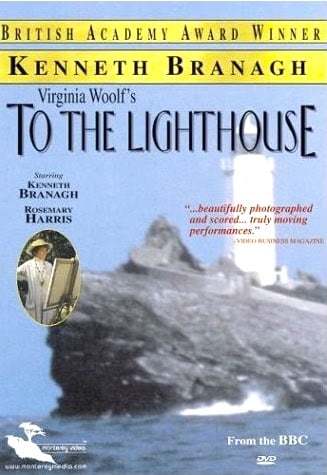

Film adaptations

1983: The first-ever television film adaptation of Woolf’s classic novel was filmed and released on March 23, 1983, in the United Kingdom. The BBC film was adapted by Hugh Stoddart and directed by Colin Gregg. Rosemary Harris, Michael Gough, and a twenty-two-year-old Kenneth Branagh star in the adaptation of Woolf’s novel about a close-knit family who finds their relationships unraveling during their extended summer holiday.

This movie earned a 56% audience score on Rotten Tomatoes, and a 3.6 average rating out of 5. It was nominated for a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) award in the Best Single Drama category in 1984, just a year after the film’s release date.

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo: Hatch Theatre Company

2021: A digital stage production of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse premiered for the first time in Dublin, Ireland. Produced by the Hatch Theatre Company, the film was adapted by Ireland’s foremost playwright, Marina Carr, and directed by award-winning director, Annabelle Comyn.

It was broadcasted worldwide on June 25, 2021 as part of the Cork Midsummer Festival in Cork, Ireland, and starred Maura Bird, Gillian Buckle, and Colin Campbell.

The production was a critical hit despite Woolf’s ambiguous narration, lack of dialogue, and direct action throughout the novel. Carr’s adaptation received several acclaimed reviews, with one from The Guardian praising its “fierce and comic thoughts spoken out loud… In director Annabelle Comyn’s beautifully orchestrated production.”

Quotes from To the Lighthouse

Here is a brief selection of quotes from Virginia Woolf’s novel To the Lighthouse:

“For it was not knowledge but unity that she desired, not inscriptions on tablets, nothing that could be written in any language known to men, but intimacy itself, which is knowledge.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“When life sank down for a moment, the range of experience seemed limitless.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Perhaps it was better not to see pictures: they only made one hopelessly discontented with one’s own work.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A sort of transaction went on between them, in which she was on one side, and life was on another, and she was always trying to get the better of it, as it was of her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“It seemed to her such nonsense-inventing differences, when people, heaven knows, were different enough without that.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The spring without a leaf to toss, bare and bright like a virgin fierce in her chastity, scornful in her purity, was laid out on fields wide-eyed and watchful and entirely careless of what was done or thought by the beholders.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“For one’s children so often gave one’s own perceptions a little thrust forward.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I suppose that I did for myself what psychoanalysts do for their patients. I expressed some very long felt and deeply felt emotion. And in expressing it I explained it and then laid it to rest.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Anna Fiore: Anna is a 2021 graduate of SUNY-New Paltz, majoring in Communications, with a concentration in Public Relations and a minor in journalism.

More about To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf Wikipedia 1927 review in the New York Times Reader discussion on Goodreads An introduction from The British Library

These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, The Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf (1927) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 25, 2021

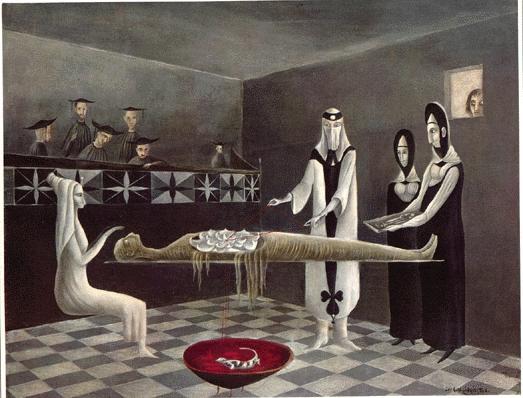

Leonora Carrington, Surrealist Artist and Writer

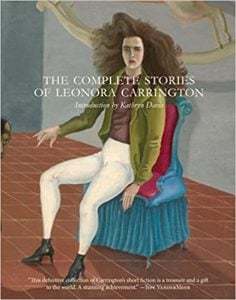

Leonora Carrington (April 6, 1917 – May 25, 2011, born Mary Leonora Carrington) was a British-born artist and writer who lived much of her life in Mexico City. Most famous for her surrealist paintings and artwork, and her prominence in the Surrealist group of the 1930s, she was also an accomplished author who published short stories, a memoir, and a novel.

One of Leonora’s recent biographers, Joanna Moorhead (also a distant relative on Leonora’s mother’s side of the family), wrote: “The key to Leonora was that she was a rebel, and a rebel to the very core of her being.” Even in early childhood, Leonora did not conform.

Her father, Harold, was a successful textile mill owner in Lancashire, England, and ran the company Carrington and Dewhurst. Her mother, Maurie, came from an Irish family and married Harold in 1908. They lived in luxury in Hazelwood Hall, a beautiful Victorian mansion near Morecombe Bay, where Maurie established herself as a society woman. It was these social norms and expectations, and the luxury of her upbringing, that Leonora railed against.

Her three brothers — Pat, Gerard, and Arthur — were sent to school at around seven or eight, but Leonora was kept at home under the tutelage of a French governess. When she did finally attend a convent school, St. Mary’s Ascot, she was promptly expelled by the nuns, who wrote to her parents that, “This girl will collaborate with neither work nor play.” Her family nickname, Prim, was beginning to seem inappropriate.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .