Nava Atlas's Blog, page 33

October 30, 2021

The Poetry Barn in West Hurley, NY

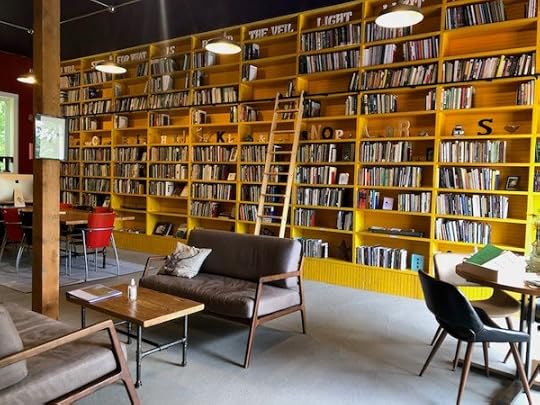

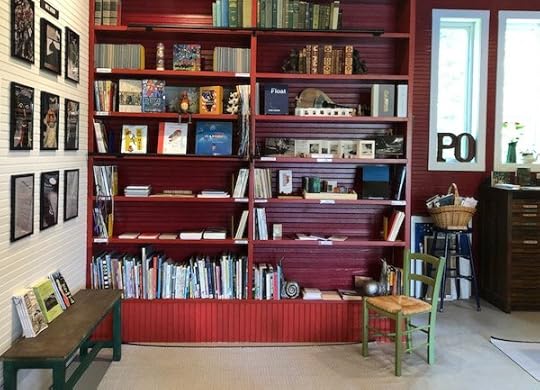

If you do a search on “Poetry Barn,” Google will first serve you an ad for Pottery Barn. Scroll right past that and you’ll arrive at the right destination — The Poetry Barn in West Hurley, New York, a private library and workshop/event space dedicated to all things poetic.

The Poetry Barn is the creation of founding director Lissa Kiernan, who converted a small barn into housing for an inviting 3,000+ volume lending library. In the surroundings of contemporary and classic poetry books, the space is a haven for a myriad of ongoing virtual and in-person workshops and occasional events.

The venue is located on a quiet residential road near the beautiful Ashokan Reservoir in Ulster County, in the Catskill foothills region of New York State. If the weather cooperates, try to schedule some time to walk around the reservoir if you’re making a special trip.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

How to visitMake an appointment for a visit: Make sure not to just show up, whether you’ve traveled from near or afar — you’ll need to make a reservation, especially important at this time, for a visit. Here is The Poetry Barn’s visit scheduler.

Tuesday-Friday, 12-6 PM (by appointment)

Saturdays 12-4 PM (by appointment)

Web: The Poetry Barn

Contact: Email: hello@poetrybarn.org | Phone: (845) 280-0430

. . . . . . . . .

The children’s corner

. . . . . . . . .

From The Poetry Barn’s website, here is their mission:

“The Poetry Barn nurtures poetry education, inspiration, and appreciation through workshops, retreats, readings, and a comprehensive poetry lending library made freely accessible to the public. Nestled in the foothills of Catskill Park in Hudson Valley, surrounded by the protected lands of the Ashokan Reservoir, we take nature as inspiration, and act as a pollinator habitat for poetry and its sister arts.”

. . . . . . . . .

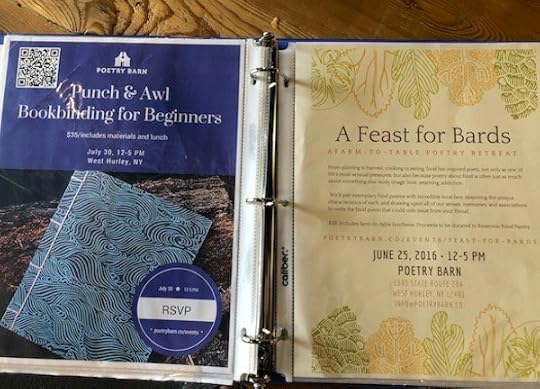

This image displays just a small sampling of the workshops offered.

Explore the entire range of workshops here.

. . . . . . . . .

The Poetry Barn offers an amazing array of workshops year -ound. Some are asynchronous (meaning you sign up for it and do the workshop on your own time, not in real time), while others are real-time Zoom events. One-on-one mentoring with noted posts is also available.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

EventsThe Poetry Barn hosts, onsite and off, wonderfully rich poetic events — readings, book launches, intimate concerts, and special workshops and classes. Check the calendar for upcoming events.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

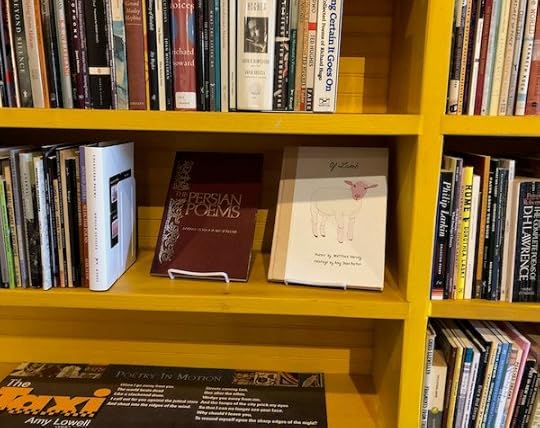

At the heart of The Poetry Barn is, as mentioned earlier, a 3,000+ volume lending library. It’s open year-round by appointment. Books may be borrowed by members — see below.

. . . . . . . . .

Membership

MembershipMembership begins at $25 per year and includes these benefits: Borrowing books from the library, 10% discounts on workshops, and invitations to exclusive events. Here’s how to become a member.

Enjoy a little poetic retail therapy with books, journals, unusual paper, and other objects for the poet in your life (or for yourself!). Grab a cup of coffee and find a cozy chair to read for an hour or so, and view the rotating display of local art.

See more of this site’s Literary Travels features.

The post The Poetry Barn in West Hurley, NY appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 28, 2021

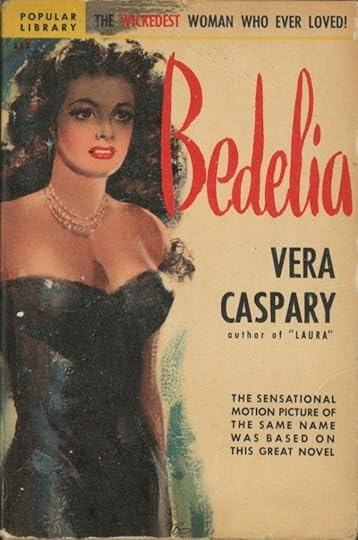

Is Vera Caspary’s Bedelia the Wickedest Fictional Anti-Heroine?

“As in Laura and now again in Bedelia, Vera Caspary avoids the conventional groove. No mysterious opening doors for her. No velvet-gloved hands or hidden rubies. No eerie cries in the night. Murder, yes, suspense, yes – plenty of it – but at the core of her stories is a comprehension that illuminates and gives credibility to the incredible actions of men and women.” (— from the back cover blurb of the 1945 first US edition).

The following analysis of Bedelia (1945) by Vera Caspary is excerpted from the forthcoming A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Novels of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth. Reprinted with permission.

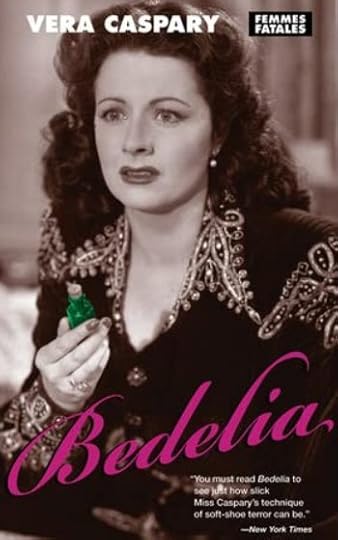

Literary parallels“She seduces men … but does she kill them? A mystery about the wickedest woman who ever loved.” (— Front cover blurb from the 2012 paperback edition published in the Femmes Fatales series by the Feminist Press at the City University of New York)

Is Bedelia the wickedest literary woman who ever loved? There are certainly some earlier candidates. Young and innocent-looking murderesses in Victorian British fiction include Lydia Gwilt in Armadale by Wilkie Collins: “I shall be your widow,” says the poisonous Lydia, “in half an hour!” and Lucy Audley, from Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret, who “bore the red brand of murder on her soul.”

At least one academic has seen multiple parallels between Bedelia and Lady Audley; it is entirely possible that Caspary read Braddon though there is no direct evidence that she did.

We do know however that she admired and deliberately emulated Wilkie Collins — as we have just seen she imitated him in the literary form of Laura and as we will soon see, even more closely in Stranger than Truth.

In Daphne du Maurier’s novel My Cousin Rachel, Philip’s eponymous cousin may or may not have tried to poison him; he was to marry her after giving her all the family treasure, but we never find out.

Close to Caspary’s time and style are husband murderer Cora from James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934) and Phyllis Nirdlinger from Double Indemnity (1943), who seduces an insurance agent into helping her kill her husband for the money; the same twin themes of insurance agent and husband murder as we find in Bedelia, but with the role of the insurance man reversed.

Carmen Sternwood in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep (1939) and its 1946 movie murders her brother-in-law and tries to kill Philip Marlowe. There is also Miss Wonderley from Dashiell Hammett’s novel and 1941 film The Maltese Falcon (1929), a murderess who tries to use her charms to manipulate Sam Spade and does seduce him.

A brief introduction

If you had been reading the original hardback American or British versions of Bedelia before the film appeared, you would have been a hundred pages in before suspecting the charming heroine of being a murderess. And if you had bought any of the paperback editions with their unsubtle front cover blurbs giving the game away, by page one hundred you might be starting to feel disappointed — no one has yet died.

Earlier on though, Caspary would have teased you with the doctor’s suspicion that Charlie Horst’s recent illness may have been caused by poison – a poison that was perhaps given to him by his new wife Bedelia. But Charlie doesn’t believe it and we’re not sure either. Bedelia does seem like the perfect wife for Charlie, and they do seem to be in love.

As the novel opens on Christmas Eve 1913, the couple has invited in many friends. Bedelia has done them proud with her lavish preparations, literally without breaking a sweat, while Charlie is sweating from all the exertion.

“Bedelia’s ivory-tinted skin continued to look as fresh and cool as the white rose she had pinned in her sash.” The rose is from a bouquet brought by neighbor Ben, an artist newly moved into the area, with whom gossip has it that Bedelia might be enamored, and perhaps vice versa; he wants to paint a portrait of her.

Bedelia has bought rather expensive presents for their friends. “She had packages for the men as well as for their wives. And such luxurious trifles!” Charlie’s old money New England friends see this as rather crass, the Austen-named guest Mrs. Bennett “computed the cost of Bedelia’s generosity. ‘We’ve none of us measured up to your wife’s extravagance, Charlie. It’s not our habit to be so ostentatious as Westerners.’”

Bedelia is no New Englander, not at all like her husband’s snooty neighbors.

“She was different from the other women in the room, like an actress or a foreigner. Not that she was common. For all of her vivacity, she was more gentle and refined than any of her guests. She talked less, smiled more, sought friendliness, but fled intimacy … Her mouth, when it was not smiling, was small and perfect, a doll’s mouth.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A heroine and a villainCharlie had not known his new wife very long before they married and still knows very little of her background.

“There were times when Charlie felt that he knew nothing about her. All that she had told him of her girlhood and first marriage seemed as unreal as a story in a book. When she related conversations she had with people she used to know, Charlie could see printed lines, correctly paragraphed and punctuated with quotation marks. At such times he would feel that she was remote, like the heroine of the story, a woman he might dream about but never touch.”

Bedelia is indeed the heroine of her own story, as she is the villain of Caspary’s. She has told Charlie that she was born in California and that her previous husband was an artist named Raoul Cochran, with whom she lived in New Orleans. She says that Raoul is now dead and that she lost the baby she was to have with him, though she is now pregnant – or is she? – with Charlie’s baby, even though they only met in August.

When she met Charlie, in Colorado Springs, Bedelia says, she was desperately poor; Charlie may have taken advantage of her: his love for her is by no means chaste and pure and he may have exploited her poverty in pursuit of his lust, which is undiminished since the marriage.

“He was glad he had married a widow,” according to a passage in the book. He soon won’t be, hints Caspary with a wink.

Fatal attraction

Later, when Charlie sees her wearing her black silk corset, he thinks it is “the most seductive garment he had ever seen and, whenever Bedelia wore it, he wanted to make love to her.”

This is quite strong stuff for the mid-1940s, implying a laxity of morals on the part of Bedelia, a laxity that is intended to attract men. Nevertheless, Bedelia also has “a natural talent for housekeeping. With less fuss than his mother had made with her two servants, Bedelia and the young girl, Mary, kept the house like a pin.”

The ideal wife – apparently – Bedelia is the perfect male-fantasy combination of naughty and nice, slutty and house-proud, at home in both the bedroom and the kitchen. She wears a black crêpe de chine dress which exemplifies this ambivalence. “The bodice was cut low but filled with ruffles of white lace. The dress was both decorous and daring. No woman could criticize, no man fail to notice.”

Later, while she is in bed and Charlie is ministering to her during the snowstorm when the house is cut off by blizzards with no phone or power and the maid and the doctor cannot get to the house, Bedelia explains to Charlie his attraction for her.

. . . . . . . . . .

Vera Caspary signed bookplate. Photo: AbeBooks.com

. . . . . . . . . .

Sneaky, sinister deceitCharlie has already felt that something is not entirely right about his perfect new wife. For one thing, she is afraid of the dark, though he tries to wean her off having the light on all night. It makes him see her, literally, in a different light.

“By day his wife was earthy, a woman who loved her home and had a genuine talent for housekeeping. In the dark, she seemed entirely another sort of creature, female but sinister, a woman whose face Charlie had never seen.”

Knowing what we know from the book’s blurb about Bedelia’s wickedness, the first hint Caspary dangles in front of us is when Charlie, with “sunken eyes, colorless lips, and a pistachio-green complexion” is ill. Bedelia makes him a sedative, pouring powder from a blue packet into a glass of water. “Drink it fast, you won’t notice the taste,” she says, as presumably do all female poisoners administering the coup de grâce.

Charlie does not die, or anywhere close to it. Nevertheless, the doctor is suspicious and appoints a nurse to act as secret guardian. “I don’t want you to eat or drink anything, not even a sip of water unless she gives it to you.”

Charlie sees the doctor’s implication, resents it, and shouts at him. “You have just made a filthy, rotten insinuation against my wife,” he says. While the doctor is still in the room, he calls Bedelia — “He needed the assurance of her physical sweetness, and he hoped to make a show of defiance before that old fool of a doctor.”

From trophy wife to suspect

Soon the storm comes in, and the house is cut off. Charlie is used to this weather in New England, but Bedelia feels trapped in, and demands they leave, go to Europe. Charlie says she is crazy; little does he know how crazy she is.

One night he finds that Bedelia has walked off into the snow. He finds her and brings her back but she is now ill and has to stay in bed for several days. While she is still in bed, but after the house has become accessible again, Ben arrives to see Charlie. He reveals that he is not an artist at all but a private investigator working for a group of insurance companies and suspects Bedelia of insurance fraud.

Ben is following up a lead on a woman who is believed to have murdered three husbands and claimed large life insurance payouts. We remember that in Laura, things were the other way around: shortly before her death, Laura has taken out a large life insurance policy in favor of her fiancé. Ben believes Bedelia is the murdering woman. He tells Charlie detailed stories about how all three men died, apparently unconnected, apparently accidental deaths, all explainable quite easily by natural causes.

According to Ben, all three men had taken out very large life insurance policies in favor of their wife shortly before they died and two of the wives had said they were pregnant before disappearing with the substantial insurance money soon after the husband’s sudden, unexpected death.

Ben explains the connection between the three mystery women and Bedelia. “In every case the woman was pretty, winning in her ways, and quite able to charm the man’s family.” They also had unusual names: Annabel, Chloe, and Maurine, and “were always sweet-tempered, docile, and patient.”

Another important factor for Ben is that the three mystery widows “photographed so badly that all of them, pretty women, too, were more afraid of cameras than pistols . . . Or poison. Have you ever taken a picture of your wife?” Charlie has but has lost the camera.

He realizes that the expensive German Kodak, a gift from his mother that he had used to take pictures of her on a trip to the mountains had “quite by accident, fallen off a cliff.” Charlie remembers how careful he had been with the precious object, not leaving it anywhere near a cliff edge at any time.

. . . . . . . . . .

Bedelia by Vera Caspary on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

The clinching factor seems to be the fact that the last dead husband collected black pearls. While Bedelia was ill in bed, Charlie found hidden in her box the black pearl ring that she had claimed was a fake and claimed she had given away. But still, Charlie is no more convinced than he had been by the doctor.

Partly because of the black pearl ring, Charlie eventually decides to force his wife to tell him the truth. She tells him about her first husband, Herman, whom she married when she was seventeen; he was not one of Ben’s three dead husbands. Playing the role of innocent ingénue to perfection, she answers all Charlie’s questions about Herman.

It is only at this point that Charlie realizes “that when she tried to tell the truth it was tarnished by deceit. For Bedelia, there was no clean line between honesty and fabrication.”

Bedelia seems to still fondly hope that Charlie will come away with her. But Charlie says he can’t afford to take her away, he is not a rich man, and she has always known it. Bedelia smiles graciously, though we now see that she is truly mad. “I’ve got plenty of money . . . I’ve got almost two hundred thousand dollars . . . You can live like a prince on that in Europe.” Charlie is shocked.

But, even presented with the absolute certainty that she has accumulated this wealth through the insurance on husbands she must have killed, Charlie still appears ambivalent. As he watches her making breakfast, watches her “enjoy the jam, pour cream over her oatmeal, measure sugar into the coffee, she seemed so innocent, so sweet and sane that he was ready to discredit everything Ben had told him.”

At this point it seems the story could go one of several ways: Charlie could forgive his wife, go to Europe with her, living off her money; she could murder Charlie and perhaps Ben for good measure; she could be arrested, convicted, and hanged; she could be arrested, tried and get off for lack of evidence.

Spoiler alert

Charlie catches Bedelia trying to poison Ben’s Gorgonzola cheese with the powder in her pillbox. “He had thought the powder in it was a polish for her fingernails.” Charlie realizes “he could no longer close his eyes, deafen his ears, remain mute, or comfort himself with miracles.” He physically attacks his wife.

“Charlie’s hand had tightened on her throat. When she saw that he was not to be cajoled out of his anger, her eyes darkened and hardened. She fought back desperately, writhed in his arms, kicked at his legs. A kind of ecstasy seized Charlie. His knuckles bulged; knots rose in his hands as they felt the warm throbbing of Bedelia’s throat. Her jetty restless eyes reminded Charlie of the mouse who caught in the trap, and he thought exultantly of the blow that had killed it.”

He doesn’t kill Bedelia, though he takes away her lethal powder. She begs for him to take her away. “I haven’t anyone else in the world. Who will take care of me? Don’t you love me, Charlie?” He takes her upstairs, lays her on the bed. “Bedelia submitted humbly, showing that she considered him superior, her lord and master. He was male and strong, she feminine and frail. His strength made him responsible for her; her life was in his hands.”

Bedelia threatens to kill herself if he lets them take her, but he is “no more moved by her threat of suicide than by her appeals and ruses.” Charlie takes a drink up for her. “Please drink it

“A bromide, dear? But I haven’t a headache.”

“I want you to take it,” he said firmly.

Bedelia looked at Charlie’s face and then at the glass. The water was clear and bubbling lightly as if it had just gushed out of the artesian well. Charlie had not known how much of the white powder to put in it, but he had guessed that a small amount would work as well if not better than too much.

“Bedelia knew that she was beaten.” She tells him she had thought he was different, not like all the others. “She sighed, pitying herself, a woman wronged by a cruel man. Reproach shone out of her eyes and her lips were pulled into a hard knot that said, wordlessly, that Charlie was to blame for everything.” Charlie is unmoved.

“Drink it!” he orders. She responds: “It’ll be your fault, they’ll blame you, you’ll hang for it,” she repeated. And seizing the glass, drank the mixture in one long swallow.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

1946 Film AdaptationIn the 1946 film version of Bedelia, she drinks the poison from a vial while she is alone after Charlie has left the room. Before she takes it, she asks Mary, the maid, to make sure that Ellen comes for lunch so that Charlie will not be alone, which is a nice touch but not in the novel.

Aware of the difference in British and American tastes and having shown the script to the US censor, an alternative ending was shot in which Bedelia turns herself in to the police rather than drinking the poison; they also reshot certain scenes where Margaret Lockwood’s hint of cleavage was deemed too indelicate for American tastes; murdering several husbands is fine but there was no hint of flesh allowed in Hays Code Hollywood.

More information and sources

Wikipedia (novel) Wikipedia (film) Vera Caspary – IMDb Bedelia by Vera Caspary on GoodReads New York Times Review (film adaptation). . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Is Vera Caspary’s Bedelia the Wickedest Fictional Anti-Heroine? appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

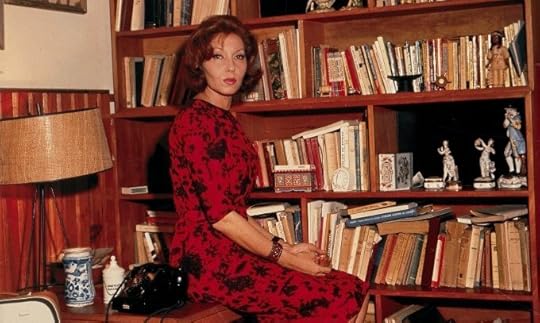

Clarice Lispector, Brazilian Novelist and Journalist

Clarice Lispector (December 10, 1920 — December 9, 1977) was one of the foremost Brazilian writers of her generation. Most famous for her novels and short stories, almost all of which experiment with form and language, she was also a journalist and wrote several high-profile columns for national newspapers.

Her works have been internationally acclaimed and widely translated, and she has often been placed alongside writers such as Virginia Woolf and James Joyce.

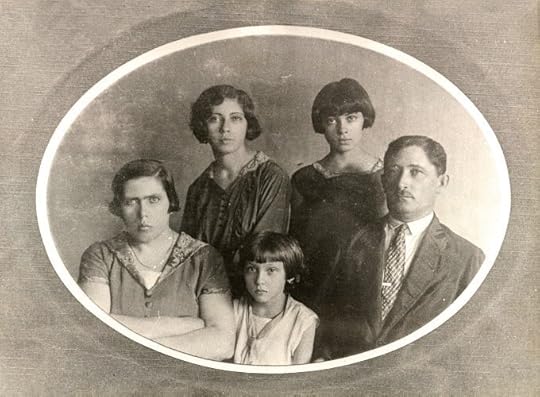

Born Chaya Pinkhasivna Lispector, Clarice Lispector was a Ukraine native. Her parents, Mania and Pinkhas Lispector were Jewish emigrants fleeing from the Russian pogroms. Mania gave birth to Clarice as the family made their way to Europe, and from there, to South America.

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo courtesy of: Criacria.wordpress.com

. . . . . . . . . .

Emigration and early yearsWith their two older daughters Leah and Tânia, and now Chaya, the Lispector family arrived in Brazil together in 1922, when Chaya was no more than one year old. All except Tânia changed their names: Pinkhas became Pedro, Mania became Marieta, Leah became Elisa and Chaya became Clarice.

These first years in Brazil’s northeast were ones of extreme poverty for the Lispectors, and the plight of the urban and rural poor was a theme that would emerge in Clarice’s later novels. They arrived in the country with almost nothing. Pedro, despite being a progressive man who had a love of the arts, worked first as a peddler and then as a merchant to support his family. In 1925, they moved to the coastal city of Recife.

Yiddish was the language spoken at home, although having arrived in the country at such a young age, Clarice’s first language would always be Brazilian-Portuguese. From 1930-1931 she attended the Colégio Hebreo-Idisch-Brasileiro (Hebrew-Yiddish-Brazilian school), and in 1932 gained admission to the Ginásio Pernambucano, the most prestigious secondary school in the state.

Pedro, in particular, encouraged all three of his daughters in their studies, and Leah and Tânia would also go on to become writers, although neither would ever be so famous or successful as Clarice.

Marieta’s health was not in good shape after the trip from her homeland, and despite now being settled somewhere relatively safe, her physical and mental conditions continued to deteriorate. She died in September 1930, and in 1935 Pedro moved with his daughters to Rio de Janeiro.

Law School and Early Works

Clarice began writing stories as a young teenager, inspired by the novels of Dostoyevsky, Hermann Hesse, and the Brazilian modernist Monteiro Lobato. She continued to write throughout her studies at the National School of Law in Rio. Her acceptance into the Law School was no small accomplishment: at the time, there were no other Jewish students and only two other women.

She supported herself by working first as a copy editor and then as a journalist for various newspapers. As a glamorous, fashionable young woman who had a talent for writing, she quickly made her mark: one of her editors wrote that she was “a smart girl, an excellent reporter, and in contrast to almost all women, actually knows how to write.”

Her first published short story, “Triunfo,” appeared in the magazine Pan in May 1940. Shortly after, in August, her father, Pedro, died during a botched gallbladder operation.

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo courtesy of: Gazetadopovo.com

. . . . . . . . . .

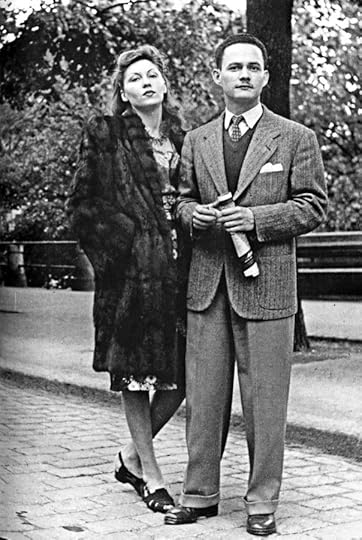

An unexpected marriageAlthough Clarice graduated from law school, she never actually practiced. However, in 1942 she fell in love unexpectedly with one of her fellow students, Maury Gurgel Valente. Maury was a Catholic and a member of the Brazilian Foreign Service. In order to marry a diplomat, Clarice had to become a naturalized citizen, which she did in January 1943.

Eleven days later, the couple were married, and there followed a period of several years in which Maury’s international postings kept them both away from Brazil. Until 1959, Clarice would return only for short annual visits.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The first of many novelsIn December of 1943, Clarice published her first novel Perto do Coração Selvagem (Near to the Wild Heart), which she had written during a feverish ten months in 1942. It had a huge impact, both critically and in popular opinion. It was awarded the Graça Aranha Prize for fiction in 1944, and critic Antonio Candido called it “an impressive attempt at taking our awkward language style to realms barely explored.”

Many of Clarice’s hallmarks were already evident in this first novel: a strong female protagonist, a process of “ontological questioning” that blurs the lines between reality and fiction, and a preoccupation with the ideas of being and consciousness.

She was also experimenting with language, with the form of the novel and with structures of interior monologues and stream-of-consciousness: experiments that would later be compared to the work of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, but that Benjamin Moser, in his biography Why This World, would attribute to Clarice’s roots in Jewish mysticism and the spiritual impulse that she inherited from her father.

Spiritual and religious influences

While in law school, Clarice began to read the work of Jewish mystical philosopher Baruch Spinoza, and this was also a major influence of hers. Like the Kabbalists, who explored divinity by rearranging letters, using nonsensical words, and decrying the rational, so too did Clarice attempt to explore new subjects, sometimes overtly spiritual, sometimes not, with new language.

“In painting as in music and literature,” she wrote, “what is called abstract so often seems to me the figurative of a more delicate and difficult reality, less visible to the naked eye.”

She also resented the comparison to Virginia Woolf, whose work, she said, she had only read after Near to the Wild Heart had been published. “I don’t like when they say I have an affinity with Virginia Woolf. I don’t want to forgive her for committing suicide,” she wrote later in one of her newspaper columns. “The terrible duty is to go on to the end.”

Later, she would be criticized for appearing to be reticent about her Jewish identity in her writing. Recently, however, scholars have argued that in fact, her Jewishness was apparent in her constant explorations of exile and of identity. There is also the fact that Brazil, in the 1930s and 1940s was an intensely nationalistic state: although safer for Jews than Europe, there were still outbursts of fascism, antisemitism, and racism. And, having been assimilated into the country before she was even a year old, Clarice was, more than anything, Brazilian.

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo: LitHub.com

. . . . . . . . . .

During her time in Europe as a diplomat’s wife, Clarice lived in Italy, Switzerland, and England. She played the role reluctantly: one of her friends said that “she was incapable of being conventional,” and the restrictions placed upon her in her situation were, at times, intolerable.

She found Italy bearable, mostly because she was busy. She volunteered at the military hospital in Naples, caring for wounded Brazilian troops, and completed her second novel O Lustre (variously translated as The Chandelier or The Candelabrum) in 1946.

But Maury’s second European posting, to Berne in Switzerland, was a time of considerable boredom and depression for Clarice. “This Switzerland is a cemetery of sensations,” she wrote to her sister Tânia, and not even the publication of her third novel A Cidade Sitiada (The Besieged City) in 1946, nor the birth of her first son Pedro, in September 1948, could lift her gloom.

Both of these European novels, like Near to the Wild Heart, featured women searching for their own identities and self-enlightenment. While The Chandelier received another enthusiastic critical reception, The Besieged City turned out to be probably the least loved and the least understood of all Clarice’s novels.

But despite the critical ambivalence, the sensation that Near to the Wild Heart had caused only grew during Clarice’s years abroad. Absence seemed to give her an aura of mystery and glamour. Rumors abounded about her foreign-sounding name, which some critics suggested was a pseudonym, while others wondered whether she was in fact a man.

This was the beginning of what the New Yorker has called “the spell” of Clarice Lispector: the sense of mystery, glamour, and slight unease that seems to accompany her name and her work even today.

Washington, D.C. and the end of a marriage

From 1952 -1959 Maury’s work took the family to Washington, D.C., and Clarice’s second son Paulo was born in February 1953. They bought a house in Chevy Chase, Maryland, and as well as working on a collection of short stories, Clarice was publishing work in Brazilian magazines and newspapers. But she was growing increasingly unhappy and discontented with the diplomatic way of life.

“I hated it, but I did what I had to…I gave dinner parties, I did everything you’re supposed to, but with a disgust…” Finally, in June 1959, she left her husband and took her sons back to Rio, where she would live for the rest of her life.

. . . . . . . . . .

Clarice Lispector page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Once back in Brazil, Clarice struggled financially and often had to work as a journalist to support herself and her sons. In addition to her fiction, she wrote a regular column for a national daily newspaper, O Jornal do Brasil, from 1967 to 1973. These “Saturday conversations,” as she called them, were later compiled into a book, Discovering the World, published after her death in 1984.

She also sometimes wrote under pseudonyms: as Helen Palmer, for example, she offered lifestyle and beauty advice, possibly paid by the American beauty brand Pond’s. But the 1960s and 1970s were also productive years for her fiction. The collection of short stories that she had begun in Washington was published in 1960, under the title “Laços de Família” (Family Ties).

The stories focused on the conventional familial bonds which can so often trap and stifle women, particularly middle-class women, although Clarice would always firmly reject the label of “feminist writer” that the stories encouraged. The collection was hailed by Fernando Sabino as “exactly, sincerely, indisputably, and even humbly, the best book of stories ever published in Brazil.”

The following year A Maçã No Escuro (The Apple in the Dark), which she had begun in England, and which was repeatedly rejected by publishers, was published by the same house that had published Family Ties, the Livraria Francisco Alves in São Paulo.

It was awarded the Carmen Dolores Barbosa Prize for best novel, despite it being her longest and probably most perplexing novel. Unusually, it also had a male protagonist, Martim, who believes he has killed his wife and flees to start a new life as a farm laborer deep in the Brazilian interior.

Two of her most famous books followed: A Paixão Segundo G.H. (The Passion According to G.H.) in 1964, in which a woman goes through a mystical experience that leads to her eating a cockroach, and Água viva (The Stream of Life) in 1973, the interior monologue of an unnamed narrator that many came to consider her finest book.

Her own preoccupations with belonging, displacement, and otherness (preoccupations that she often claimed stemmed from having been born “in flight”) were apparent in these later works: the female narrator of her novel Água viva states that, “I can’t sum myself up because it’s impossible to add up a chair and two apples. I’m a chair and two apples. And I don’t add up.”

The critic Leo Gilson Ribeiro wrote that “With this fiction, Clarice Lispector awakens the literature currently being produced in Brazil from a depressing and degrading lethargy and elevates it to a level of universal perennity and perfection.”

Clarice, however, struggled to complete Água viva: her friend Olga Borelli later recalled that “She was insecure and asked a few people for their opinion. With other books, Clarice didn’t show that insecurity. That was the only time I saw Clarice hesitate before handing a book into the publisher.”

During the intervening years, she also wrote seven collections of short stories and four children’s books and worked also as a translator from English into Portuguese, publishing translations of Agatha Christie, Edgar Allan Poe, and Oscar Wilde.

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo: TheParisReview.org

. . . . . . . . . .

Even during these years of increasing success, Clarice was notoriously guarded about her life. She granted very few interviews, and repeatedly bent the facts in the equally few autobiographical columns that she wrote, leaving the press and reading public unsure, exactly, of who she really was.

In recalling a visit to the Sphinx in Egypt during World War Two, she wrote: “I didn’t decipher her. But she didn’t decipher me, either. She accepted me, I accepted her. Each one with her own mystery.”

In September of 1966, she suffered an accident in her apartment when she fell asleep in bed with a lit cigarette. The resulting burns were so bad that her right hand almost had to be amputated, and she had permanent scars on her legs. She rarely talked about it later, saying only that, “… I spent three days in hell, where — so they say — bad people go after death. I don’t consider myself bad and I experienced it while still alive.” But an increasing dependence on sleeping pills made her behavior more and more erratic.

While she decried the press for portraying her as eccentric, it was an image that she also cultivated: in 1975 she accepted an invitation to appear at the First World Congress of Sorcery in Colombia. The aura of mystery, of something almost supernatural, continued even after her death.

When the French-Canadian Clare Varin began researching Clarice’s life in the 1980s, she received a warning letter from Brazilian author Otto Lara Resende: “Be careful with Clarice,” he wrote, “It’s not literature. It’s witchcraft.”

The Hour of the Star

Her final book, A Hora da Estrela (The Hour of the Star) was published in 1977. The story revolves around a male narrator, who reflects on the life and death of a young girl from Alagoas, the poor northeastern state in which the Lispector’s had lived when they first arrived in the country. Shortly after the book was published, Clarice gave her only television interview, and told the interviewer, “When I don’t write, I am dead … I’m speaking from my tomb.”

Later that year she was admitted to the hospital after suffering a hemorrhage. She was never told the official diagnosis of ovarian cancer and died on December 9, 1977. She was buried in the Jewish Cemetery of Caju in Rio.

Several of her works have been turned into films, and since Benjamin Moser’s 2009 biography Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector, her work has undergone an extensive retranslation, published by New Directions Publishing and Penguin Modern Classics.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is an author, poet, and artist with a serious case of wanderlust. She is originally from the UK, but has spent time abroad in Europe, the United States, and the Bahamas.

When not traveling or working on her current projects — a chapbook of poetry, “The Cabinet of Lost Things,” and a novel based on the life of modernist writer and illustrator Djuna Barnes — she can be found with her nose in a book, daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Visit her on the web at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Clarice LispectorNovels

Near to the Wild Heart (1943)The Chandelier (1946)The Besieged City (1949)The Passion According to G.H (1964)An Apprenticeship, or The Book of Pleasures (1968)Agua Viva (1973)The Hour of the Star (1977)Breath of Life (1977)Short story collections

Alguns contos (1952) – Some StoriesLaços de Família (1960) – Family TiesA Legião Estrangeira (1964) – The Foreign LegionFelicidade Clandestina (1971) – Covert JoyA Imitação da Rosa (1973) – The Imitation of the RoseA Via Crucis do Corpo (1974) – The Via Crucis of the BodyOnde Estivestes de Noite (1974) – Where You Were at NightPara Não Esquecer (1978) – Not to ForgetA Bela e a Fera (1979) – Beauty and the BeastThe Complete Stories (2015)Biographies

Reading With Clarice Lispector by Hélène Cixous (1990)Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector by Benjamin Moser (2014)More information on Clarice Lispesctor

The True Glamor of Clarice Lispector Overlooked No More (NY Times) Reader discussion on Goodreads Jewish Women’s Archive Wikipedia Clarice Lispector (Author of The Hour of the Star). . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Clarice Lispector, Brazilian Novelist and Journalist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 24, 2021

Zelda Fitzgerald — Talented, Troubled Wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald

Zelda Fitzgerald (July 24, 1900 – March 10, 1948), known for her beauty and personality, made a name for herself as a socialite, novelist, dancer, and painter. She was far more than merely the wife of writer F. Scott Fitzgerald, who called her “the first American flapper.”

Born Zelda Sayre in Montgomery, Alabama, she met Scott at a country club dance in 1918, when he was stationed outside of Montgomery during WWI. He was immediately taken by Zelda, and their passionate and tumultuous relationship began — as did Scott’s liberal borrowing of material from her letters and diaries for use in his own works.

Although friends and family were not necessarily in favor of their match, Zelda agreed to marry Fitzgerald once his first novel, This Side of Paradise, was published. He finished it in the fall of 1919 and urged his editor, Maxwell Perkins, to hurry the release. This Side of Paradise was published March 26, 1920, and the couple was married on April 3rd at St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

This Side of Paradise not only sold its initial 3,000 print run, but two subsequent runs within a month, and with that success, Zelda and Scott became celebrities and icons of the Jazz Age.

On October 26, 1921, Zelda gave birth to their first and only child, Francis “Scottie” Fitzgerald. As Zelda emerged from anesthesia, Scott recorded her saying of her daughter, “I hope it’s beautiful and a fool — a beautiful little fool.” He later paraphrased this quote in his most famous novel, The Great Gatsby, having Daisy Buchanan say after giving birth: “I’m glad it’s a girl. And I hope she’ll be a fool—that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool.”

After the publication of Scott’s second novel, The Beautiful and the Damned, the New York Tribune asked Zelda to write a review of her husband’s book. The piece led to other offers from magazines, including the 1922 “Eulogy on the Flapper” for Metropolitan Magazine.

. . . . . . . . . .

Zelda and Scott in the early 1920s

. . . . . . . . .

In 1924 the Fitzgeralds moved to Paris, having burned through their money. Zelda began an affair with a French pilot, Edouard S. Jozan, and asked Scott for a divorce. In the midst of their marital drama, Scott finished The Great Gatsby and Zelda attempted suicide with sleeping pills.

In Paris the following year, Scott became friends with Ernest Hemingway, although Zelda and Ernest openly detested one another. Zelda pursued many of her own artistic ventures. She was a painter and later became obsessed with ballet, dancing up to eight hours a day. Scott was dismissive of her goals and wrapped himself in writing and alcohol.

As the 1920s progressed their relationship was strained and their creativity was hurt by mental and emotional struggles and addictions. Their partying had turned self-destructive toward the end of the 1920s, and in 1930 Zelda was admitted into a sanitarium in France, where she was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

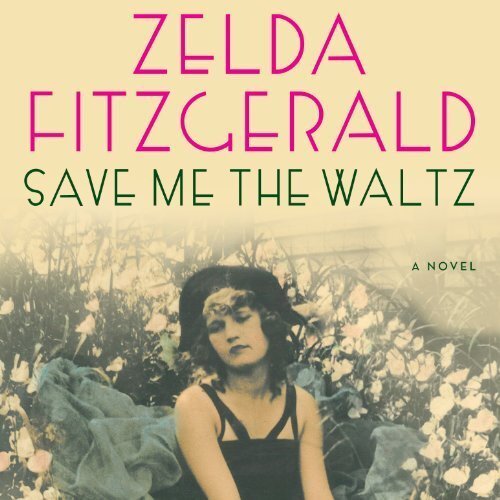

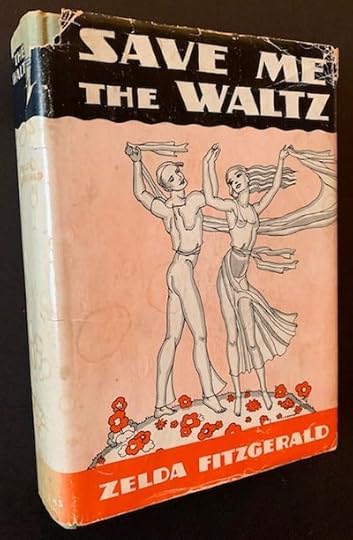

While admitted to another clinic in 1932, Zelda wrote a novel called Save Me the Waltz in six weeks and sent it to Maxwell Perkins, Scott’s publisher at Scribner’s. When Scott found out about the novel he was furious. He forced her to rewrite parts of the novel that he considered too autobiographical, as well as parts that he planned on using in Tender is the Night, which would be published in 1934.

The first edition of Save Me the Waltz was published October 7th, 1932 in a print run of just 3,010 copies. It sold only 1,392 copies for which Zelda earned $120.73. Between the poor sales and her husband’s criticism of the work, Zelda’s spirit was crushed. It was the only novel she would publish.

. . . . . . . . .

See more of Zelda’s artwork

. . . . . . . . .

As her paintings and other hobbies were also not well received, Zelda became more reclusive and mentally unstable. In 1936 she was admitted into Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, a place she would return to on and off for the remainder of her years.

In 1937, Fitzgerald moved to Hollywood to work in the film industry and began an affair with movie columnist Sheila Graham. Scott was bitter toward his wife, blaming her for his recent failures. Despite their troubles, the couple took a trip to Cuba together in 1939. It was disastrous, and when they returned to the states, Scott returned to Hollywood and Zelda to Asheville. They never saw one other again.

F. Scott Fitzgerald died at the age of forty-four in 1940. That same year, their daughter Scottie was married. Zelda missed both events. On March 10th, 1948 a fire broke out at Highland Hospital where Zelda was in residential treatment. She was locked in a room for electroshock therapy and unable to get out, she perished in the fire along with eight other patients.

. . . . . . . . . .

Save Me the Waltz, original edition

. . . . . . . . . .

Zelda: A Biography, the first book-length treatment of Zelda’s (1970) was written by Nancy Milford when she was in graduate school. It was a bestseller and finalist for the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize.

Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald by Therese Anne Fowler: This biographical historical novel about the life of Zelda Fitzgerald was published by St. Martin’s Griffin in 2014.

Guests on Earth By Lee Smith: This novel by author Lee Smith is set in Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina from 1936 – 1948, during the years Zelda was a resident and was killed in a fire.

Call Me Zelda by Erika Robuck: First published in 2013, this novel is set in a Baltimore Psychiatric hospital in 1932 where a nurse befriends Zelda and gets drawn into her tumultuous world.

Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda : The Love Letters of F.Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald: The twenty-two-year love story between Scott and Zelda is documented in this work through their letters. It includes 333 letters illustrated by photographs.

Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise by Sally Cline: Published by Arcade Publishing in 2003, this book is described as a “Tragic, Meticulously Researched Biography of the Jazz Age’s High Priestess.”

The Romantic Egoists: A Pictorial Autobiography from the Scrapbooks and Albums of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald: Published by the University of South Carolina Press in 2003, The Romantic Egoists weaves the story of Scott and Zelda through their personal scrapbook and photo albums.

Beautiful Fools: The Last Affair of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald: This 2013 publication focuses on Zelda and Scott’s 1939 trip to Cuba, the last time the couple saw each other. It describes their last attempt to grasp at love and happiness after the brightness of their earlier star had faded.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Amy Manikowski: Amy has worked in books her entire life, starting at the David A. Howe Public Library in Wellsville, NY. In college she began working in the bookstore, a career that lasted fifteen years. She received her MFA in creative writing from Chatham University in 2004. Since graduate school she has been in love with traveling and writing about the South, moving first to Savannah, GA, then Kentucky and South Carolina, before setting in 2011 in Asheville, North Carolina. Amy blogs at Daily Inspiration for Writers.

This article was originally published as Zelda Fitzgerald — the First American Flapper on biblio.com. Reprinted with permission.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The post Zelda Fitzgerald — Talented, Troubled Wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 21, 2021

Bookstagram for Authors and Book Lovers

Bookstagram is an Instagram account featuring books with pictures dedicated to showcasing everything “bookish.” Bookstagram for authors and book lovers uses a series of hashtags, participates in special book events and themes, and posts images that involve bookshelves, book spaces, and of course, books!

Some of the best Bookstagrammers stick with a central theme. Many of them use props to enhance these themes, while others develop styles unique to their brand. Bookstagram accounts post book reviews and host book giveaway contests, too!

Bookstagram is great for authors looking to build a following and connect with readers and other writers. It’s also an enjoyable use of social media for avid book lovers who wants to connect with others of like minds, showcase what they’re currently reading, or highlight bookish nooks and corners of their homes.

Here are some tips for how to participate in Bookstagram, and how to use the platform.

Find a Unique Selling Point (USP)This is important as your USP is what makes your book uniqueAsk yourself what your niche isThe answer to that question is the foundation of your strategy to promote your book on social media

Promotion

The primary objective is to build hype about your book and show people what you have to offer, without giving away all the secrets you wrote in your new book. You can do this by…

Sharing teasers and updates from your book. Start with something small – a fragment of a photo, a corner of the cover – and work up to bigger spoilers. In the last few weeks before the book is released, you can share teasers of the book to show people what’s to come.Keeping a healthy mix of content, from book trailers to newsletters and teasers. You’ll notice that there are a lot of video content online, so you’ll want to mix it up — this is because video content is usually more successful on Facebook and Instagram than static posts.Offering exclusive content to people who sign up for your newsletter, or pre-order the book. Make sure you announce those exclusives on your social media pages, so that everyone knows what they’re missing!Posting timely content, especially around the holidays. Even when a book isn’t directly related to an upcoming holiday, you can stage them in a festive setting to tie into the event and included relevant hashtags in the caption to position your title as a holiday gift.. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

GiveawaysSocial media giveaways are very easy to set up. It’s as simple as making a post on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter or YouTube — and then using an app to harvest the comments and pick a winner (there are even multi-network apps that allow you to collect comments from several different social network sites).

The purpose of a giveaway is to get more attention and encourage sales from people who aren’t lucky enough to win a copy of your book for free. You can also use giveaways to learn more about your audience. For example, you’ll get a ton of statistics from the giveaway about which social networks are most active, what time your followers are online, and so on.

How to get the most out of a giveaway:Create a simple, eye-catching graphic that contains the word giveaway with a photo of the prizes (in this case, your book cover).Gather 5-20 fellow Bookstagrammers who will repost your giveaway graphic to spread the word.Post to your Instagram account explaining the giveaway and its rules. Don’t forget to mention whether or not your giveaway is international or country-based.Some rules for giveaways:The user must be following your Instagram accountThe user must repost your graphic to their page or story (so it will reach their followers)The user must use your giveaway-specific hashtag (so you can find their entries later)Optional: The user must tag people in the comments of your post to receive additional entry points (this helps extend your audience reach and also gives your post a ton of social proof, which boosts you in the Instagram algorithm)

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo Courtesy of Ella Jardim: Unsplash.com

. . . . . . . . . .

Aim to begin your social media activity early on with the intention of creating a community that will turn into potential book buyers. You can build your community by engaging with your followers by asking questions, responding to comments, running polls, and trying to like your followers’ posts. Posting a few times a week is okay for posts, but you should try to keep your Instagram stories active by posting daily.

You should also aim to create a unique, specific hashtag for your book and encourage your audience to use your hashtag. Over time, that hashtag will become a landing page for users to view everything that is relevant to your book.

Sharing user-generated content (UGC), also shows that you value the dedication of your followers. UGC is otherwise known as content your followers create and tag you in that can be reposted to your own profile. Sharing any kind of UGC will help persuade your potential readers to purchase your book and also encourage them to share their reviews, giving your book more exposure.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

If you want to take your Instagram strategy one step further, try tying your posts and Instagram Stories together. Instagram stories are a great tool for cross-promoting content.

Prior to your book launch, you can share multiple variants of your book cover and request your followers to vote on their favorite. You can do this by using the polling feature in your Instagram stories.

Other ideas for Instagram stories:Post screenshots of your favorite quotes and snapshots from your bookShare photos of yourself with your favorite booksCreate a story about your writing process and or your book launchShare photos from your initial draft, places you went for inspiration, and so on…

You can also encourage readers to preorder your book with an Instagram story promoting your preorder link. Authors are always asking you to preorder their book titles, and it is because preorders inform booksellers about what new books people are interested in.

Potential PartnershipsIt is worth mentioning that it is crucial to connect with fellow bookstagrammers and gift them a copy of your book, especially if they have a large following. This is because by sharing your book with them, you are essentially garnering free reviews (which are a tremendous help with sales), and they are also indirectly promoting your book at the same time.

Contributed by Anna Fiore: Anna is a 2021 graduate of SUNY-New Paltz, majoring in Communications, with a concentration in Public Relations and a minor in journalism.

More information and sources

How to Start a Bookstagram for Beginners 17 Instagram Book Promotion Ideas from Publishers Instagram Book Marketing: How to Promote Your BookSee more resources for writers on this site.

The post Bookstagram for Authors and Book Lovers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

How to Use BookTok: A Guide for Authors and Publishers

BookToks are TikTok accounts that are dedicated to books and everything “bookish.” They’re part of a niche platform for short-term video content. BookToks might include content such as videos about literary collections, building at-home libraries, book reviews, and promotions for new releases. Here’s a quick guide on how to use BookTok.

You might notice that many people post content that is awfully similar. These are known as “trends” or challenges, and they can ultimately help widen your page reach.

TikTok started out as a platform mainly used by teenagers, but it has quickly expanded its reach to incorporate influencers, much as Instagram does. Businesses have jumped on the bandwagon to use TikTok as a marketing tool, so it was just a matter of time before BookTok emerged as a marketing tool for publishers. In other cases, young book lovers have become BookTok influencers as an outgrowth of their passion for books and all things bookish, rather than by design.

Here are a few tips for how the book community can use BookTok:

The Algorithm

Users consume videos through their “For You” pages, which is an algorithmically programmed feed that delivers content to users based on what they have engaged with in the past. Once a user begins viewing and engaging with a specific type of content, there is a snowball effect in which that user is served more of that type of content.

The most effective TikTok strategy is no different from other social media platforms:

Engage with your followers by liking and replying to their comments (the more comments a video receives, the more the platform recognizes it as “engaging” and will show it to more people)Post regularly — keep people excited for new content and don’t let your page die downUse hashtags to help people discover your videosHashtags

There is a lot of conflicting information online on the most effective strategy for using hashtags on TikTok. We have found that the best thing to do is to use a combination hashtag strategy.

Meaning, use 4-6 hashtags that represent your brand (#authorsoftiktok, #writertok, etc.) and then add 4-6 hashtags that fit the content of the video. You can also use trending hashtags if you are copying a trend or a challenge.

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo Courtesy of Caleb Woods: Unsplash.com

. . . . . . . . . .

Content Ideas for Marketing and PromotionPost a book cover revealSummarize your bookPost an unboxing videoShow your audience about your writing process and the pains of editingTell your audience about the publishing processLend writing tips and tricks for aspiring authorsShare quotes and illustrations from your bookEngage with other BookTok-ers and ask them to post a review of your book What not to doMake sure to mix up your content so that you’re not only self-promoting your book. It would be useful to share other tips and tricks for writers as well as book recommendations. Your followers will get turned off if all you do is self-promote.

How to Get Your Videos Trending

The number one factor that will help you boost your page reach is trending sounds. If you see a sound that has over ten thousand videos under it, use it. You can even put it over a video in the background of you talking and it will still boost your views.

Once you spend some time on TikTok for a while, you’ll start to notice that many people post videos that are similar—similar sounds and similar themes. These are known as “trends” or challenges. Look for ways you might be able to take advantage of TikTok trends and hashtag challenges to promote your new book.

Keep in mind however, that TikTok allows 15-second videos. This means that you only have 15 seconds to grab your audience’s attention and persuade them to buy your book.

Contributed by Anna Fiore: Anna is a 2021 graduate of SUNY-New Paltz, majoring in Communications, with a concentration in Public Relations and a minor in journalism.

More information and sources

Using TikTok to Sell Books 19 Ways to Promote Your Book on TikTok 15 TikTok Ideas for Authors to Help Grow Their Audience and Book SalesSee more resources for writers on this site.

The post How to Use BookTok: A Guide for Authors and Publishers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 20, 2021

All-of-a-Kind-Family by Sydney Taylor — Jewish Joy, Family Ties

All-of-a-Kind-Family by Sidney Taylor (1951) is the first of a series of children’s books about the everyday lives of a tight-knit Jewish family at the turn of the 20th century. Ella, Henny, Sarah, Charlotte, and Gertie are young sisters who live with their parents in the Lower East Side of New York City.

This story and its sequels smooth the rough edges of immigrant life, but the warmth and strength of the family unit sends the message that love and mutual respect can overcome many of life’s challenges. The girls occasional bicker, but their love and loyalty for one another is evident.

The five sisters love to do everything together, whether it’s going to the library to choose each week’s treasured books, interacting with peddlers in Papa’s junk shop on rainy days, or going on the rare outing with wise, patient Mama.

This book is notable for its emphasis on Jewish holidays and traditions, presenting them as joyous occasions without resorting to tired stereotypes. In the few decades following the first of the series in 1951, the All-of-a-Kind Family books were the best known children’s works depicting Jewish life in America.

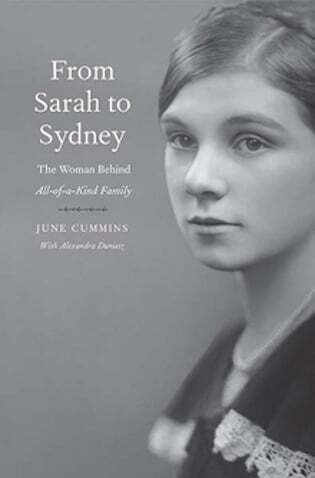

Sydney Taylor (1904 – 1978) was born Sarah Brenner to Jewish immigrant parents, and like her subjects, grew up in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. She even used the real names of her sisters in the fictionalized account (though she herself was Sarah in the books and later changed her name to Sydney).

. . . . . . . . . .

From Sarah to Sydney (Yale University Press, 2021)

. . . . . . . . . .

Until now, not a lot was known about her despite the popularity the All-of-a-Kind series. That may change thanks to a 2021 biography, from Sarah to Sydney by June Cummins and Alexandra Dumietz. In a presentation titled “Who Was Sydney Taylor?” Cummins wrote:

“As a grown woman, Sydney remembered the early days of her family’s life on the Lower East Side. Although they were poor, like most Jewish immigrants, they had many happy times. Just like the girls in the books, Sydney and her sisters were ‘five little girls [who] shared one bedroom—and never minded bedtime. Snuggled in our beds we would talk and giggle and plan tomorrow’s fun and mischief.’”

A review in The Nashville Banner (November 16, 1951) by Kay Early Russell, also confirms the series inspiration from the author’s real-life experiences:

“The author of All-of-a-Kind-Family is also a wife the mother of a teenage daughter, Jo. Jo loved to hear stories of her mother’s youth, and the tales of good times with her four sisters. Inspired by her only daughter’s enthusiasm, Mrs. Taylor set her tales to paper and All-of-a-Kind-Family was born.

The author has a keen insight into situations that appeal to children, and is able to present them in a satisfying way. It’s a happy, warm story of five little girls who live with their parents (of modest means) in a four-room flat on New York’s Lower East Side.”

. . . . . . . . . .

All-of-a-Kind Family on

Bookshop.org

* and

Amazon

*

. . . . . . . . . .

A 1951 review of All-of-a-Kind FamilyFrom the Meriden Record (Meriden, CT), October 26, 1951

The Charles W. Follett award for “worth contributions to children’s literature” has been awarded this year to All-of-a-Kind-Family by Sydney Taylor, a newcomer to the field of children’s books.

The five little heroines, ranging in age from four to twelve, might be described as the East Side’s prototype of Little Women.

Ella is the eldest, in the first throes of romantic puppy love; Henrietta, the ten-year-old, is the madcap of the family, able to turn a tragedy like getting lost at Coney Island into an ice cream binged financed by good-natured policemen; Sarah is the conscientious one; and six-year-old Charlotte and little Gertie are at the delicious age when it takes half an hour to select two cents’ worth of penny candy.

Since Papa runs a junk shop and business is only fair-to-middling, there is more love than money in the little apartment. Chores are shared, along with joys and ceremonies of the great procession of Jewish holidays, and descriptions of the special dishes that Mama prepares are enough to make the mouths of both adult and child readers water.

When work lags, Mama thinks up ingenious games with buttons and bright pennies to make chores go faster. And when a rainy day forces them to stay indoors, what better haven could any little girls find than the crowded junk shop. There, the peddlers sit around the stove and a newly-arrived stash of discarded books yields collections of fairy tales and paper dolls to reward the patient little searchers.

The eight-year-old and up reader for whom this book is intended will find herself completely enamored with its little heroines. Their adventures are natural, funny, and heartwarming, and the family atmosphere that Mrs. Taylor has recreated so well from her own remembered childhood combines the brightness of reality with the glow of love.

The only note of implausibility, but one of which romantic-minded pre-teens will heartily approve, is the romance between Charlie, the handsome misplaced junkman and Miss Allen, the pretty young librarian.

Without being aware of it, young readers will absorb attitudes as well as facts from All-of-a-Kind-Family. Along with a fascinating picture of the East Side food markets in the old days, and some vivid descriptions of Jewish holidays, the child reader will gain an appreciation for children who observe different customs. Altogether, a wholesome experience as well as an enjoyable one.

All-of-a-Kind-Family seriesAll-of-a-Kind Family (1951), illustrated by Helen JohnMore All-Of-A-Kind Family (1954), illustrated by Mary StevensAll-of-a-Kind Family Uptown (1958), illustrated by Mary StevensAll-of-a-Kind Family Downtown (1972), illustrated by Beth and Joe KrushElla of All-of-a-Kind Family (1978), illustrated by Gail Owens

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post All-of-a-Kind-Family by Sydney Taylor — Jewish Joy, Family Ties appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 18, 2021

Marguerite Henry, Author of Misty of Chincoteague

Marguerite Henry (April 13, 1902 — November 26, 1977), was a beloved American author of animal stories for children. She authored more than fifty children’s books throughout, capturing especially the dreams and fantasies of horse-loving children everywhere.

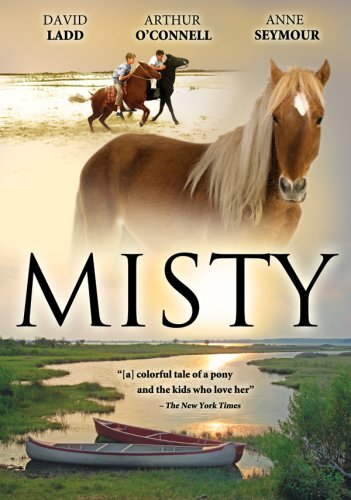

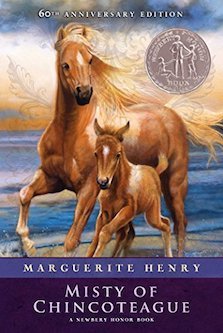

Many of Marguerite Henry’s books are based on true stories of horses (and occasionally other animals), and have since been translated into twelve languages. Her best-known novels are Misty of Chincoteague (the basis for the 1961 movie Misty) and its sequels.

King of the Wind (1948) is another of her most popular novels, recognized as “the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children,” by the American Library Association. Both it and Misty of Chincoteague won the highest accolade a children’s book can garner, the Newbery Medal Award; King of the Wind won the Young Reader’s Choice Award in 1951 as well.

Early Life

Born and raised in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Marguerite was the youngest of the five children of Louis and Anna Breithaupt. She was stricken with rheumatic fever at age six, which kept her bedridden until she was twelve years old.

Marguerite wasn’t allowed to go to school because of her weak state and the fear of spreading her illness to others, and discovered the joy of reading while confined. She read many western adventure stories by Zane Grey and decided at a young age that she wanted to live on a ranch of her own someday, where she could see her own horses run and play.

Shortly after Marguerite discovered the joys of reading, she found a love for writing as well. Her father, a publisher, gifted her a little red desk and some writing supplies one for Christmas. He continued to encourage his daughter’s writing, from the age of seven on, by supplying her with reams of paper and lots of pencils. She always wrote about animals, including dogs, cats, birds, and foxes, but her stories focused primarily on horses.

In 1913, when Marguerite was eleven years old, she published her first article. Her mother told her about a local magazine that was looking for submissions by children about the earth’s seasons. She wrote a short story about the change of the seasons, “Hide and Seek in Autumn Leaves” which the magazine published. It earned her twelve dollars, a tidy sum at the time.

Marriage and the Start of a Writing CareerMarguerite studied to become an English school teacher at the Milwaukee State Teacher’s College. One summer, she went on a fishing trip where she met her future husband, Sidney Henry. They were married on May 5, 1923.

After the two were married, Marguerite continued to write articles for magazines. Her husband was supportive of her writing ability, and encouraged her to write for publications such as The Saturday Evening Post and Reader’s Digest.

In 1939, Marguerite and her husband bought a small farm cottage on two acres of land in Wayne, Illinois, which they named Mole Meadows. It was the farm Henry always dreamed of as a child.

In 1940, she published her first full-length book, Auno and Tauno: A Story of Finland. This was quickly followed by several other children’s books, including Dilly Dally Sally (1940), Geraldine Belinda (1942), and Their First Igloo on Baffin Island (1943).

. . . . . . . . . .

Illustration by Wesley Dennis. Photo: Askart.com

. . . . . . . . . .

Marguerite Henry’s first book to earn critical acclaim was her novel, Justin Morgan Had a Horse (1945). After finishing the manuscript for the story, Henry scanned her local library’s children’s book section looking for the perfect illustrator.

She stumbled upon a story called Flip, written and illustrated by Wesley Dennis, and fell in love with the illustrations. She sent Dennis a copy of the manuscript to Justin Morgan Had a Horse, asked him to illustrate the novel. He kindly accepted, and the story became a Newbery Honor Book.

The two went on to produce more than twenty novels together, thus beginning the start of a long and successful partnership.

. . . . . . . . . .

Marguerite Henry with the real Misty

. . . . . . . . . .

Misty of Chincoteague (1947) became one of Marguerite Henry and Wesley Dennis’ most popular and enduring works. Like most of her books, this children’s novel was based on a true story. Marguerite valued historical authenticity, and spent many months meticulously researching each of her books before writing them.

In 1945, she had heard the tale of ponies who survived the shipwreck of a Spanish galleon hundreds of years before. They supposedly swam to shore and live on an island off the coast of Virginia and Maryland. Intrigued, Marguerite and Wesley Dennis went to observe Pony Penning Day, when the ponies swim from Assateague to Chincoteague Island.

Misty was a real filly that Marguerite spotted at the auction on Pony Penning Day in Chincoteague. “The first time I saw Misty, my heart bumped up into my throat until I thought I’d choke,” she wrote in A Pictorial Life Story of Misty. “It was a moment to laugh and cry and pray over, especially if all your childhood you wanted a pony and couldn’t have one on account of your rheumatic fever.”

Misty lived with Marguerite for several years while she worked on her book. As usual, Wesley Dennis illustrated it. Rand McNally published the novel in 1947, when it was met with great success. After the publication of the book, Misty became an instant celebrity and was even invited to an ALA conference!

Henry’s work has captivated generations of children and young adults and won many honors and awards. In 1961, Misty of Chincoteague won the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award and was named a Newberry Honor Book.

Misty became the subject of a 1961 motion picture film, as did Brighty in 1967. Justin Morgan Had a Horse was filmed by Walt Disney Productions in 1972, and the King of the Wind came to the big screen in 1990.

. . . . . . . . . .

A review of Misty of Chincoteague

. . . . . . . . . .

Marguerite Henry finished her last novel, Brown Sunshine of Sawdust Valley (1996) just before her death in 1997. She died at the age of 95 in her home in Rancho Santa Fe, California after a series of strokes.

Married for sixty-four years, Marguerite and Sidney Henry had no children, but they did have many animals that inspired some of her stories throughout her career. It was her dying wish that her ashes be scattered in the Pacific Ocean, as were her husband’s (he had died a decade earlier). A niece and nephew of Marguerite and Sidney Henry did the honors.

To this day, Marguerite Henry remains one of the classic voices of animal stories written for children. A great many of her books remain in print and continue to be read; her legacy of heartwarming stories lives on.

Contributed by Anna Fiore: Anna is a 2021 graduate of SUNY-New Paltz, majoring in Communications, with a concentration in Public Relations and a minor in journalism.

. . . . . . . .

Marguerite Henry books on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

More about Marguerite HenryMajor works

Auno and Tauno: A Story of Finland (1940)Dilly Dally Sally (1940)Birds at Home (1942)Geraldine Belinda (1942)Their First Igloo on Baffin Island (1943)A Boy and a Dog (1944)Justin Morgan Had a Horse (1945)The Little Fellow (1945)Robert Fulton, Boy Craftsman (1945)Always Reddy (1947); also published as Shamrock QueenBenjamin West and His Cat Grimalkin (1947)Misty of Chincoteague (1947)King of the Wind: the Story of the Godolphin Arabian (1948)Little-or-Nothing from Nottingham (1949)Sea Star, Orphan of Chincoteague (1949)Born To Trot (1950)Album of Horses (1951)Brighty of the Grand Canyon (1953)Wagging Tails: Album of Dogs (1955)Cinnabar, the One O’Clock Fox (1956)Misty, the Wonder Pony, by Misty, Herself (1956)Black Gold (1957)Muley-Ears, Nobody’s Dog (1959)Gaudenzia, Pride of the Palio (1960); also published as The Wildest Horse Race in the WorldAll About Horses (1962)Five O’Clock Charlie (1962)Stormy, Misty’s Foal (1963)Portfolio of Horse Paintings (1964)White Stallion of Lipizza (1964)Mustang, Wild Spirit of the West (1966)Dear Readers and Riders (1969); also published as Dear Marguerite HenryStories from Around the World (1971)San Domingo, the Medicine Hat Stallion (1972)A Pictorial Life Story of Misty (1976)Our First Pony (1984)Misty’s Twilight (1992)Album of Horses: a pop-up book (1993)Brown Sunshine of Sawdust Valley (1996)My Misty Diary (1997)Selected film adaptations

Misty (1961)Brighty (1967)Justin Morgan Had a Horse (1972)King of the Wind (1990)More information and sources

Wikipedia Reader discussion of Marguerite Henry’s books on GoodReads Marguerite Henry biography Marguerite Henry: Forever Young Washington Post: ‘Misty’ Author Marguerite Henry Dies at Age 95. . . . . . . . . .

*Thesea are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Marguerite Henry, Author of Misty of Chincoteague appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 16, 2021

The White Girl by Vera Caspary, Forgotten Contemporary of Nella Larsen’s Passing

Passing by Nella Larsen (1929) has staked an important place as a classic fictional work of race, class, sexuality, and identity. Thematically similar,The White Girl by Vera Caspary, a white Jewish novelist and screenwriter, was published earlier that same year and is all but forgotten. This analysis of how this now-obscure novel relates to Nella Larsen’s enduring classic is excerpted from the forthcoming A Girl named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Novels of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth.

In a career spanning 1929 to 1979, prolific novelist and screenwriter Vera Caspary wrote a series of compelling strong and amoral women. Her two most famous titular anti-heroines – Laura and Bedelia – were turned into successful Hollywood films of the noir genre in the 1940s.

Enthusiastic reception for The White Girl

The heroine of Caspary’s first, semi-autobiographical novel is neither strong nor amoral. The White Girl came out in January 1929 to very enthusiastic reviews and had run into a sixth edition by March of the same year, the month in which Nella Larsen published Passing to much more tepid reviews and poor sales.

As Caspary says in her autobiography (The Secrets of Grown-Ups), “there was a rumor that I was a Black girl who had written an autobiography.” She wasn’t. Despite the many strongly autobiographical elements in The White Girl, its heroine Solaria Cox is not Jewish like her author but is transposed to a light-skinned young Black woman, her “camellia-toned skin” pale enough to allow her to pass as white, which she does, as did many young Black women in Chicago and New York, the settings for both The White Girl and Passing.

In Larsen’s novel, Clare, whose father is a janitor like Solaria’s, passes as white so successfully that her white husband never suspects she is Black until later on when she reunites with an old friend who is involved in the (fictional) Negro Welfare League. When he finds out, the husband accuses Clare of being a “damned dirty n–!” Clare falls out of the window and dies, though it is not clear whether she was pushed or if she has killed herself rather than carry on with her life after her true racial heritage has been revealed.

Caspary’s Solaria and Larsen’s Clare

In The White Girl, Solaria has a Black family, and is striking and attractive to men of all races; like Clare, she “passes” successfully.

“She was a tall girl with a languorous fine figure, small hips, exquisite breasts and a narrow head carried high on a sensitive neck. Her wide-set dark eyes were dusky mirrors, mysterious, hardly alive. Her nose was straight and arrogant, set bravely above a short upper lip. With her fine black hair and white face, she looked as if she might be a Spanish aristocrat.”

In Larsen’s Passing, Clare’s friend Irene has a similar Hispanic look. ‘They always took her for an Italian, a Spaniard, a Mexican, or a Gypsy. Never, when she was alone, had they even remotely seemed to suspect that she was a Negro.”

Like Clare, their mutual friend Gertrude has married a white man. Irene reflects, “’Though it couldn’t be truthfully said that she was ‘passing.’ Her husband—what was his name? — had been in school with her and had been quite well aware, as had his family and most of his friends, that she was a Negro. It hadn’t, Irene knew, seemed to matter to him then. Did it now, she wondered.”

Irene does not herself consciously try to “pass” but she is curious about Clare and ‘this hazardous business of “passing,” this breaking away from all that was familiar and friendly to take one’s chance in another environment, not entirely strange, perhaps, but certainly not entirely friendly.’ When Clare asks Irene if she herself never thought of passing, Irene answers quickly “No. Why should I?”

For her own part, Irene finds that her annoyance at women who try to pass “arose from a feeling of being outnumbered, a sense of aloneness, in her adherence to her own class and kind; not merely in the great thing of marriage, but in the whole pattern of her life as well.” Irene feels that she is betraying her race by helping Clare hide her origin from her husband but is also reluctant to betray her friend in support of her race:

“… she shrank away from the idea of telling that man, Clare Kendry’s white husband, anything that would lead him to suspect that his wife was a Negro. Nor could she write it, or telephone it, or tell it to someone else who would tell him. She was caught between two allegiances, different, yet the same. Herself. Her race. Race! The thing that bound and suffocated her. Whatever steps she took, or if she took none at all, something would be crushed. A person or the race. Clare, herself, or the race. Or, it might be, all three.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Nella Larsen’s Passing is now widely read and studied;

while Caspary’s The White Girl has fallen into obscurity

. . . . . . . . . .

Vera Caspary’s ironically-titled The White Girl is also about the “hazardous business” of passing, and though it was published three months earlier than Larsen’s Passing and written several years earlier than that, it could be read as a long form of answer to Irene’s questions.