Nava Atlas's Blog, page 29

March 18, 2022

Ruth Moore, Chronicler of Coastal Maine

I became aware of novelist and poet Ruth Moore (July 21, 1903–December, 1989) while vacationing in Maine. Walking through a parking lot in Acadia National Park, I spotted a bumper sticker: “I Read Ruth Moore.” That’s how many people learn of Ruth Moore. Like me, they spot one of the three hundred bumper stickers spread around eastern Maine by publisher Gary Lawless and then they begin to investigate.

What they’ll find out is that Moore was a best-selling novelist (her second novel, Spoonhandle, spent 14 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, along with George Orwell and Somerset Maugham, when it was published in 1946).

They’ll learn that Moore was born on a small island off the coast of Maine, and in the course of her life published numerous novels that portrayed the “wonderful, real folks” of coastal Maine and, in the words of one reviewer, “rounded them out into a community, so we see them not so much as individuals, but as a whole.”

First Jobs

The world is filled with best-selling novelists who are never heard from again, but I found myself drawn to Moore when I learned that this island-born Mainer had also lived in Greenwich Village and worked for a time for the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, a civil rights organization formed in 1910) in New York.

In 1930, Moore went to the American South on behalf of the NAACP to investigate the case of two young African-American men convicted of murder. Moore uncovered evidence to free them.

In 1935, novelist Alice Tisdale Hobart (Oil for the Lamps of China) hired Moore as a typist and personal assistant. In that role, Moore lived in Washington, D.C., and Berkeley, California. While back home in Maine for a visit in 1940, Moore’s sister, a high school teacher, introduced her to a former student, Eleanor Mayo, also a writer. Mayo, then twenty years old, returned to California with Moore, planning to attend the University of California. The two spent the rest of their lives together.

First Novel: The Weir

In a 1987 interview for Down East magazine, Moore said she began writing her first novel, The Weir, out of homesickness. “I began to write that story as a way of escaping from that awful [California] weather,” Moore said. “You can’t imagine how homesick I was for snow. I remember how many times I would get up from the typewriter, go to the window, look up at the snow-capped peaks of the high Sierras, and just stand there with tears rolling down my cheeks.”

Perhaps it was the “awful” California weather that drove Moore and Mayo to New York City in 1941. There, Moore went to work for Reader’s Digest while continuing to work nights and weekends on The Weir. After twenty-five rejections, The Weir was published in 1943, and was described in the New York Times as “a notable first novel” that “tells a rugged, sea-swept tale.”

But Moore’s novels deal with much more than men and their boats. Strong women are always present in her books. In The Weir, we have Alice, who wants to marry, but only on her terms:

She couldn’t explain the way she had felt, seeing him sit down at her breakfast table, because the way she had felt wouldn’t make sense to any man—one side of her glowing with satisfaction at having him there, enjoying her good food, the other side shriveling with fury at the way, just like her father, he had pulled up to the table and took for granted that her province was to feed and wait on him. How could you explain that something you liked tremendously at the same time belittled and affronted you?

Moore plumbs even deeper with the character of Sarah Comey, mother of three young men. As Sarah watches one son do everything he can to undermine the success of his brothers, even if it means their destruction, she makes one of the most difficult decisions any parent must make, ending the life of one son so that her other children can survive.

. . . . . . . . . .

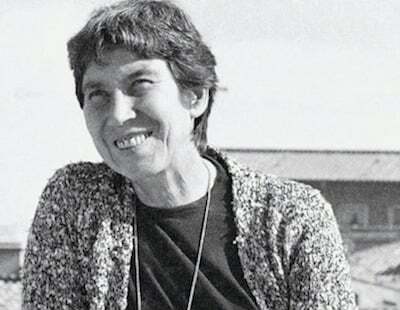

Ruth Moore in 1949, this photo and at top by Edie Sand,

Tremont Historical Society

. . . . . . . . . .

In 1945, Moore published a short story, “It Don’t Change Much,” in The New Yorker. In 1946, she published her second novel, Spoonhandle. Here we find another strong woman — Ann Freeman, returning to her home in a Maine fishing village in search of a quiet place to write after earning a degree at the Columbia School of Journalism.

She is joined by a less appealing figure, Agnes Flynn, who plots with one of her brothers to profit at the expense of others in the village, and by several other women. These include the well-meaning Mary Mackay, who attempts to foster a young orphan, and Mary Sangor, a Portuguese woman ostracized by Agnes Flynn and many other ladies in the town.

This book sold over a million copies and was made into a film, Deep Waters. Sadly, only one of these women — Mary Mackay — made it into the movie version of Spoonhandle. There is a character named Ann Freeman, but she is nothing like the character in Moore’s novel, either in her circumstances or her motivation, despite the prominent, full-screen crediting of Moore and her novel in the opening frames of the film.

Moore, presumably indignant at the distortion of her work, walked off the set as Deep Waters was being made and canceled the remainder of her seven-year contract with 20th Century Fox. She was reportedly shunned by Hollywood for the remainder of her career.

Fortunately, that remaining career was a good one. With the money from Spoonhandle, Moore and Mayo purchased land on Mount Desert Island, the location of most of Maine’s beautiful Acadia National Park. Together they built a house from recycled and second-hand materials. The structure grew as the years passed, and over the decades to come, Moore published twelve more novels and two books of poetry.

Mayo published five novels of her own and then turned to local politics. In 1950, she became the first woman elected to the board of selectmen in the town of Tremont, Maine.

. . . . . . . . .

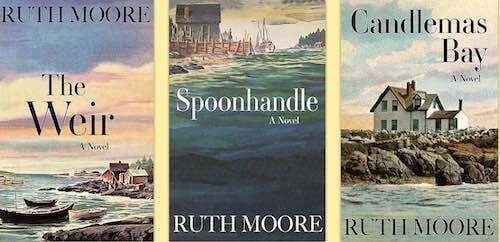

Ruth Moore’s books at Islandport Press

. . . . . . . . . .

Most of Moore’s novels are set among the island and coastal towns and villages of Maine in the mid-twentieth century. But the issues Moore grapples with in her depictions of these communities are surprisingly contemporary. How does income inequality (in the form of wealthy “summer people”) affect the local population? How do people respond to ethnic diversity? (In Spoonhandle, in the form of Portuguese immigrants; in Speak to the Winds, a later novel, in the form of then-called mulattoes, Greeks, Italians, and Native Americans.)

Bad marriages, class conflicts, real estate deals, the role of women, competition for resources, political corruption—these are all situations that plague the most charming community at one time or another, but in the words of one reviewer, “it’s hard for Miss Moore to maintain a villain, because by the time she gets him properly set down you’re on his side to some extent, just through the exuberance and totality of her portrayal.”

In Speak to the Winds (1956), Moore depicts an island village split apart, first by the question of who is at fault, and who will pay for a replacement when the church furnace explodes during the town’s Christmas pageant. As the months pass, the town grows increasingly polarized. Neighbors refuse to speak to neighbors. The postmistress reads and intercepts mail. People boycott one another’s shops.

It’s a situation all too familiar today. At one point, a character in Speak to the Winds suggests that she can tell which side people are on simply by looking at the way they are dressed — one group in clean but plain clothing, the other group attired in a manner that strikes the character as somewhat pretentious. It takes a disastrous fire to pull the town together again:

On the shore, people from the village had come, black, running figures are seen hazily through smoke. Two of them were tearing down the rocks, waving arms, yelling … The whole town. Coming together. To see what might be done.

To Moore’s mind, she told the story not just of Maine, but of people throughout the country as small-town life changed. At the height of her popularity (the 1950s and 1960s), her books were often chosen by subscription book clubs and translated into other languages.

Even at that time, however, she was characterized as a regional writer, and by 1983, while still alive, the sale of her books had diminished and had gone out of print. However, some of her ballads were set to music by folksinger Gordon Bok, and in 1986, Maine poet and publisher Gary Lawless issued a reprint edition of The Weir.

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

Ruth Moore RevivedIt’s fitting that Moore, the portrayer of Maine’s communities, warts and all, has been taken up by a community of Maine book lovers. If you’re in Maine, it’s not hard to find Ruth Moore once you know to look for her. Lawless, co-owner of Gulf of Maine Books in Brunswick, discovered her when his mother told him to read Moore. He looked for used copies of her out-of-print books and started a letter-writing campaign to get her books back into print.

When he consulted Moore, who he got to know in the last years of her life, she said, “Why don’t you do it?” Through his Blackberry Books press, Lawless did just that, reissuing some eleven titles beginning in the 1980s. As Lawlesss aged, he felt the need to pass on the responsibility for keeping Moore’s work in print. Dean Lunt of Islandport Press has taken up the task.

Like Moore, Lunt grew up in a fishing village on an island of the coast of Maine. As someone from the island communities who had become a successful writer, Moore was familiar to Lunt, despite his being many decades removed from her.

Aided by the advent of digital printing, Lunt has been able to bring Moore’s titles back onto the shelves in bookstores throughout the state, a project he is continuing, and one in which the larger community of readers who live in or visit Maine have taken part.

Ruth Moore’s legacy

The Bass Harbor Memorial Library now celebrates her birthday with Ruth Moore Days, which feature a community reading of her work and offers other tributes to this author increasingly embraced by those who know and love Maine as the writer most adept at “catching the nature, character, and personality of her people.”

In 2018, the Stonington Opera House mounted a production of “I Have Seen Horizons: Ruth Moore’s Stories from Maine.” The title—I have seen horizons—comes from the single line typed on a sheet of paper found in Moore’s typewriter at the time of her death.

“It’s ironic,” Lunt observes. “Moore bristled against the depiction of her work as having a regional focus, but it’s her focus on Maine that is the reason we can still sell her. She’s unique in her descriptions.”

He notes as well that it was because of Moore’s experiences living in New York, working in the South, and then in California that she was able to come back to Maine with a fresh perspective and capture in her books what was unique about these island communities and describe them so vividly that they still speak to readers today.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

More about Ruth MooreNovels

The Weir (1943)Spoonhandle (1946)The Fire Balloon (1948)Candlemas Bay (1950)Jeb Ellis of Candlemas Bay (1952)A Fair Wind Home (1953)Speak to the Winds (1956)The Walk Down Maine Street (1960) Second Growth (1962)The Sea Flower (1964)The Gold and Silver Hooks (1969)“Lizzie” & Caroline (1972)Dinosaur Bite (1976)Sarah Walked Over the Mountain (1979)Poetry

Cold As a Dog and the Wind Northeast (1958)Time’s Web: Poems by Ruth Moore (1972)The Tired Apple Tree: Poems and Ballads (1990)Letters and short stories

High Clouds Soaring, Storms Driving Low: The Letters of Ruth Moore (1993)When Foley Craddock Tore Off My Grandfather’s Thumb: The Collected Storiesof Ruth Moore and Eleanor Mayo (2004)

More information and sources

Tremont Maine Digital Archive Publisher Revives Ruth Moore’s Honest Portrayals of Maine Island Life Ruth Moore: Storyteller Maine Encyclopedia Reader discussion of Moore’s books on Goodreads. . . . . . . . . .

Explore more in this site’s Author Biographies.

The post Ruth Moore, Chronicler of Coastal Maine appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 10, 2022

What (Jane Austen’s) Women Want: Exploring Questions We’re Still Asking

If you’re like me, you’ve many times had to explain what Jane Austen is really about — you might find yourself explaining to friends who just don’t get it, that Austen is not all about finding a man who’s wealthier and more powerful than you are, to marry. This musing, pondering the question of what Jane Austen’s women want, is excerpted from The Austen Connection, reprinted by permission.

Sure, these novels follow the traditional Marriage Plot. These novels may have invented the plot as we know it today. As we’ve said before and will point out often in these letters, the stories also — while not technically Romance-genre stories — introduce, build on, and play off of our favorite Romantic Tropes, from the hate-to-love or friends-to-lovers storylines, to the Alpha male, forbidden love, and proximity plots.

But we also know that within this scaffolding of she-who-identifies-as-girl-meets-complicated-person-who-identifies-as-boy, there is a lot of meandering to get to our much-anticipated engagement, and there’s also some analysis after the Love Declaration, where Austen shows us what she’s been doing all the while.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

And this post-game analysis takes place in the books, friends, not so much in the screen adaptations. That’s because Knightley and Emma apologizing to each other and explaining what they’ve learned through their experiences in the preceding scene, just doesn’t make good cinema. But it’s actually pretty sexy reading.

So, I thought we could discuss what all this meandering — the subtext within Austen’s actual text — is about, and where Austen is trying to take us, as her heroines, and their leading guys, wander through the wilderness of society, and customs, and class, and humiliations, to get to their unexpected (or entirely expected, by us the reader) happy ending, with a hard-won, successful match: a marriage.

So here’s a very simple question: What do Austen women want?

For me, the question leads us to some unexpected places — places that go well beyond the Courtship and Marriage plot. Places that take us on a tour of key issues those identifying as women have even today. Or especially — you might say — today.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

1. See me

The first thing I’ll argue here that Jane Austen’s women want is simply to be seen as human.

I know that sounds a bit basic, maybe even sarcastic — but when you break down what characters like Lizzy Bennet and Fanny Price actually say, you realize they want to be seen, and they want to be seen as rational, human creatures.

And they say as much.

When Elizabeth Bennet implores Mr. Collins, during his proposal, to see her as “rational” she is drawing, it’s assumed, from Mary Wollstonecraft’s famous treatise A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published in 1792, when Jane Austen was seventeen years old.

This plea of Elizabeth’s to be seen as rational — and not be taken as a flattering, manipulative “lady” of fashion in search of gallantry or advantage — cannot be overestimated: It is truly central to what Austen’s heroines, and what Austen herself wanted.

In Vindication, Wollstonecraft urges women not to buy in to the roles society creates for middle- and upper-class women — to be pretty playthings who responded to gallantry, and in doing so either became victims or deployed what little agency they have toward manipulation.

In the intro to Vindication, Wollstonecraft paints an ugly picture of the women her 18th-century world had created: women who, taken in by the flattery of men, “do not seek to obtain a durable interest in their hearts, or to become the friends of the fellow creatures who find amusement in their society.”

Lucy Steele, anyone? Insert your favorite Austen mean-girl here.

To me, the entire sense vs. sensibility tension that drives Austen’s characters and plots reads like a fictionalization of Wollstonecraft’s premise in Vindication.

Wollstonecraft says — Listen up: This construct you’re putting women into is bad for women, and it’s bad for men. It’s bad for everyone. It’s just bad.

Austen says this over and over too. But she says it differently, and through fiction.

Wollstonecraft’s message is: Look what happens to us when you don’t provide women with opportunities for education and agency — you end up wasting half of society’s resources, and everyone is unhappy in the bargain.

But Austen gives us a lopsided mirror image of the bleak picture painted by Wollstonecraft, showing us: Look what happens when do you have educated women, like Elizabeth Bennet and Elinor Dashwood and Anne Elliot — what you get is strong women with authentic affections who are better supporters not only of their families, but can make meaningful contributions to society.

The difference is imagination. The difference is story. Austen creates an imagined world that forces us to see past the real one.

Because Austen was first and foremost an artist — and she continuously deploys her imagination to fashion a better world through art, through fiction. And often, still more than 200 years later, we don’t see it.

But the way Jane Austen does it is a lot more fun.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

2. Just call me Human

Jane Austen’s women are not just intelligence that is forcefully conveyed — think Emma Woodhouse, Elizabeth Bennet, and Fanny Price (Mansfield Park) who, as we’ve said, are in their various ways the Smartest Person in the Room.

But Austen’s stories flip the script, with feeling — the radical interiority of her characters that is urged on every reader also forcefully puts upon the reader the feelings, the cares, the loves, the doubts, the triumphs, of these young women characters.

We empathize. And empathy leads to understanding.

This is the powerful thing Austen is doing — that Wollstonecraft is doing too, but again Mary is doing it through political writing and Jane is doing it through storytelling. (And specifically, one way she’s doing this is through her celebrated stylistic technique of free indirect discourse.)

Rather than Wollstonecraft’s “enfeebled” women – women weakened by frippery, and romance — Austen’s women want to be seen not as Females, but as Humans engaged in and contributing to the vast human enterprise. Not decorations, however well cared for, on the margins of that enterprise.

Sometimes I feel like all of Austen’s literary techniques and dramatic powers are rallied toward this enterprise. She deploys point of view, narration, and an intense interiority of the female perspective, to create empathy, as writers before and since have done.

To do what Austen did in the early 19th century is still considered even today to be radical and innovative — from Toni Morrison and Elena Ferrante to Karl Ove Knausgaard: To show our point of view, and in doing so to reveal our humanity.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

3. Let’s call it a tie (or ‘companionate marriage’)

Of all people, it is often the leading men that take Austen’s challenge to reason and humanity seriously, in her novels.

It’s easy to dismiss Mr. Darcy, Henry Tilney, and Mr. Knightley as chivalric, powerful suitors.

But they defy — and deftly undercut — the mold: They look the part, but their “manners” are blunt and challenging in a way that throws off notions of chivalry. (Charlotte Brontë took this to the extreme with Rochester and was called a “sexual delinquent” for doing so by a 19th century reviewer — but that’s a topic for another day, friends!)

Austen’s leading men are also affectionate, understanding, and always straightforwardly candid. Austen places them in opposition to gallant falsity of the Wickhams, the Willoughbys, and the Frank Churchills.

Knightley and Darcy, our most famous leading men in Austen, are perhaps the biggest examples of blunt, candid, challenging truthfulness mixed with genuine feeling. And it’s why they are also so appealingly — there’s no better word for it — sexy.

Even Henry Tilney, who has lots more experience than naïve Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey, treats her respectfully, even while challenging her wild, Ann Radcliffe-inspired imaginings.

In Emma, the character that most challenges the Female Ideal of idle useless playfulness is Knightley himself.

So, what’s going on here?

First of all, Austen is so good at her job that we always have to remind ourselves, friends, that it is not of course Knightley who makes the charge to Emma’s governess that our heroine should be more usefully employed and more often opposed — it is Austen giving him his words.

It is always Austen, behind the scenes, putting the words into the mouths of our powerful heroes. And in doing so I think she’s showing that women just might be worth the trouble. It’s jarring to even write that last sentence — but in Regency England this was something that needed to be said: If an astute, wealthy, independent Knightley is clear enough in his head to say that most men do not want to marry silly women, then maybe Austen’s early-19th-century readers would reconsider what after all makes a good wife, and maybe they would pay attention to her and other young women in their life.

They’re invited to do this through the words, and actions, of Knightley. This is what’s going on, friends, when Knightley invites Harriet Smith to dance with him in that infamous swoony scene that rescues Harriet and lifts her beyond the painful public condescension of the Eltons.

Austen is standing up for the women by appealing to the men — in language they understand.

It is always Austen, behind the scenes, putting the words into the mouths of our powerful heroes. And in doing so I think she’s showing that women just might be worth the trouble.

And as we’ve pointed out in these letters and will continue to explore, all the meandering around and toward courtship and marriage in Austen has, for Regency-world readers, an unexpected destination. It is always a union between not only equals — equally strong, equally judge-y, and equally flawed and feeling humans — but also it’s a union that is predicted to be intellectually challenging to each party.

This is one of the things that makes Austen, in the end, a writer of realism rather than romance. The romantic scaffolding is there for all to enjoy — but we also see, along the way, plenty of conflict and conflagration that is going to come from two real people with real passions and real opinions. And that clash is both the romance and the realism.

It’s also what makes people — actually human ones — stronger.

Austen repeatedly shows that marriage between two people is an opportunity to improve, or not: The Bennetts’ marriage makes each of them worse; marriage between John and Fanny Dashwood makes each more selfish and weaker; marriage between Emma and Knightley will make each more generous and engaging.

Marriage in Austen can be a living nightmare or a benevolent dream. And it is not romance — but education, intelligence, and integrity, mostly of women — that decides it.

So in Austen, a spouse can improve you, and improve your life and that of your family. It can even increase your status and popularity, which in this Regency world is a tool for survival.

So, in Jane Austen’s world, an equal, candid, challenging marriage is a survival skill, and, also, a lot more fulfilling and fun.

Read the rest of What (Jane Austen’s) Women Want on the Austen Connection.

Contributed by Janet Saidi. Janet is a public-radio journalist with a couple of degrees in Literature, and has written about arts and culture for NPR, the BBC, the Christian Science Monitor, and the Los Angeles Times. Join the conversations on all things Jane Austen at the Austen Connection newsletter, @AustenConnect on Twitter, and at @austenconnection on Instagram and Facebook. And you can follow the Austen Connection podcast on Spotify and Apple.

The post What (Jane Austen’s) Women Want: Exploring Questions We’re Still Asking appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 9, 2022

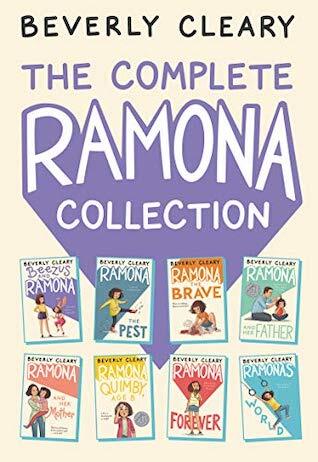

Reading and Revisiting Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby Stories

Literary Ladies contributor Marcie McCauley delves into children’s book author Beverly Cleary’s beloved character, Ramona Quimby, with this appreciation.

“The sight of that smooth, faintly patterned cloth fills me with longing,” writes Beverly Cleary, recalling an early childhood memory of Thanksgiving. At first, a moment of calm for the young girl: anticipating relatives seated around the dining room table. Then, activity: she finds a bottle of blue ink, pours some out, presses her hands into it, then “all around the table I go, inking handprints on that smooth white cloth.”

You might guess that the lingering memory would be the moment of discovery. Instead: “All I recall is my satisfaction in marking with ink on that white surface.”

A writer finds her voice

Dedicated Beverly Cleary readers cannot help but see Ramona Quimby in this incident recounted in Beverly’s memoir, A Girl from Yamhill (1988), which covers her early years in rural Oregon, while My Own Two Feet (1995) covers her early working years, filling blank pages with inked stories.

I also think of my fictional friend Ramona when I envision Beverly Bunn (the author’s pre-marriage name) sliding down the banister, trying to find the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, pressing her nose against the barbershop window, yearning to look under the swinging doors of a saloon, feeling frustrated when the church ladies mistook her for a picture (a pitcher!) with big ears, and standing on the tilting seat of the fair’s Ferris Wheel.

Others might see a mischievous or rambunctious girl; I see curiosity and intensity, someone stretching to see beyond the edges of a scene.

Early on, young Beverly enjoyed films and comic strips more than books, but soon was lured into reading — via fairy tales— myths, and legends and, eventually, The Dutch Twins by Lucy Fitch Perkins. In the seventh grade, she discovered her love of writing, via an essay about her favorite characters; she couldn’t choose —Tom Sawyer, Peter Pan, and Judy from Daddy Long-Legs were all contenders—so she invented a journey to “Bookland” to accommodate everyone. There’s more about Beverly’s love of story and how it influenced her writing career in this brief biography.

In her second memoir, Cleary describes the Suzzallo Library in Washington: “a cathedral-like building that seemed elaborate after Cal[ifornia]’s neoclassical Doe library.” She attended the School of Librarianship, under the guidance of Miss Siri Andrews, whose “courses took me back to my childhood. The slogan of children’s librarians was ‘The right book for the right child.’”

Cleary’s studies intensified her dedication to storytelling: “Most of my evenings, I read, read, read. There was so much I needed to learn, so many books to become acquainted with.” But she was ultimately inspired to write her first book for the boys she met while working in a library, who asked for books about boys like themselves.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Henry Huggins makes way for RamonaHenry Huggins (1950) was published ten years after Beverly Bunn married and became Beverly Cleary. In her introduction to its 2016 reprint, she emphasizes the importance of believability and relevance, in her efforts to pull young readers into stories: “Henry would have a dog, an ordinary city mutt because dog stories so often seemed to be about noble country dogs.”

She also describes her surprise over her first book being about Henry: “I assumed I would write about a girl. After all, I had been a girl, hadn’t I?”

You might say that Ramona was both an unexpected and accidental heroine. Cleary had been an only child and, recognizing that all her characters were only children too, she determined to give one of them a sibling:

“When it came time to name the sister, I overheard a neighbor call out to another whose name was Ramona. I wrote in ‘Ramona’, made several references to her, gave her one brief scene, and thought that was the end. Little did I dream, to use a trite expression from books of my childhood, that she would take over books of her own, that she would grow and become a well-known and loved character.”

This is no exaggeration: Ramona’s emergence in Henry Huggins is brief indeed:

“Beezus’s real name was Beatrice, but her little sister Ramona called her Beezus and now everyone else did, too. Beezus and Ramona already had a cat, three white rats, and a turtle, so one fish wouldn’t make much difference. It took Henry a long time to decide which guppy to give her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Ramona blossomsYears later, Cleary’s editor Elizabeth Hamilton suggested Ramona could have her own book. Readers then encounter Henry through her eyes, in Ramona the Pest (1968): “She had known Henry and his dog Ribsy as long as she could remember, and she admired Henry because not only was he a traffic boy, he also delivered papers.”

Now Ramona is five years old, and she’s starting kindergarten. “People who called her a pest did not understand that a littler person sometimes had to be a little bit noisier and a little bit more stubborn in order to be noticed at all.”

In Ramona the Brave (1975), she is about to start first grade, and she is afraid of the gorilla in the book Wild Animals of Africa in her bookshelf. Her mom has a new bookkeeping job at their doctor’s office, and the world begins to widen in positive and negative ways.

“Agreeing was so pleasant she wished she and her sister could agree more often. Unfortunately, there were many things to disagree about—whose turn it was to feed Picky-picky, the old yellow cat, who should change the paper under Picky-Picky’s dish, whose washcloth had been left sopping in the bathtub because someone had not wrung it out, and whose dirty underwear had been left in whose half of the room.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

In Ramona and Her Father (1977), Picky-Picky eats the jack-o-lantern because he hates the cheaper food purchased while the family has only one income.

When the girls go to Mrs. Swink’s house to interview her for Beezus’s school project, they learn what her girlhood had been like: “Nothing very exciting, I’m afraid. I helped with the dishes and read a lot of books from the library. The Red Fairy Book and Blue Fairy Book and all the rest.” Ramona’s life is so much more interesting.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Interesting, but still ordinary: in Ramona and Her Mother (1979) she learns how to write in cursive and gets her first hair cut.

“Nobody had to tell Ramona that life was full of disappointments. She already knew. She was disappointed every evening because she had to go to bed at eight-thirty and never got to see the end of the eight o’clock movie on television. She had seen many beginnings but no endings.”

In Ramona, Age 8 (1981), Ramona and Beezus cook dinner by themselves for the first time, and Ramona starts into DEAR—Drop Everything and Read— at school. Ramona’s world expands a little with every volume.

“She tried not to think of the half-overheard conversations of her parents after the girls had gone to bed, grown-up talk that Ramona understood just enough to know her parents were concerned about their future.”

In Ramona Forever (1984), Ramona’s father has almost finished earning his teaching credentials and Ramona’s friend Howie gets a unicycle, which means she can ride his bicycle.

“Someone’s nose is out of joint. Ramona had heard them say it many times about children who had new babies in the family. This was their way of talking about children behind their backs in front of them.”

Cleary is consistently respectful with her young characters; she doesn’t cut corners with her grown-ups either.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

In Ramona’s World (1999), our heroine is excited about the fourth grade; she is not excited by a copy of Moby Dick, which has almost no quotation marks and small print. Ramona’s inner world has always been rich and complex, but now that her understanding of the wider world is increasing, readers see her begin to process the ever-shifting dynamic of coming-of-age. Beneath just one simple word, she is preparing for what’s next:

““Okay,” said Ramona, but she was thinking about Beezus growing up and about what it would be like to grow up herself. She felt the way she felt when she was reading a good book. She wanted to know what would happen next.”

More than a decade passes between the publication of the last two Ramona books, along with other stories and her two memoirs. Bruce Handy, in Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult (2019), writes:

“I loved Cleary before I knew anything about her, but I loved her even more after reading her two memoirs—The Girl from Yamhill and its sequel, My Own Two Feet—and learning that her career was to some extent fueled by her pique at insipid children’s books, the kind that treat kids as if they were mush-headed or shallow, rather than just young. I haven’t read every word Cleary has written, but I’ve read most of them and I’ve never known her to condescend to children or anyone else. Her books are warm but they have backbone. Her pique has served several generations of readers well.”

And why does Ramona stand out in that lauded landscape? In a 2006 HarperCollins interview, “Celebrate Reading with Beverly Cleary,” the author is succinct and clear: “She does not learn to be a better girl.”

Children, she believes, long for the same universal things: home, parents who love them, friends, and teachers they love. Ramona need not learn to be a better girl—she simply must be Ramona. It’s more than enough: most of the letters Cleary received during her career were about either Dear Mr. Henshaw or Ramona.

Cleary doesn’t revisit her characters in her mind to think of new adventures for them. Children enjoy rereading their favorite stories, she says, in that 2016 edition of Henry Huggins, and “by doing that, they learn.”

So does Ramona: “I’ve read all my books a million times,” said Ramona, who usually enjoyed rereading her favorites.” (From Ramona’s World) On occasion, Ramona would come into Cleary’s mind, though, and Cleary would think something like “Oh, Ramona would enjoy that” or “I bet Ramona would love to get herself into that mess.”

As though somewhere, independently, Ramona’s “what would happen next” is unfolding.

. . . . . . . . . .

The complete Ramona collection on

Bookshop.org* and Amazon.com*

. . . . . . . . . .

Perusing Anna Katz’s The Art of Ramona Quimby: Sixty-Five Years of Illustrations from Beverly Cleary’s Beloved Books (2020) is akin to rereading the Ramona stories. This kind of bird’s-eye view of the series is fascinating because not only does Ramona’s world broaden as the series unfolds, but readers’ understanding of Ramona and her world also broadens.

In the section devoted to the illustrators of Ramona Forever, for instance, are three different illustrations of a scene: one each from Jacqueline Rogers, Alan Tiegreen, and Tracy Dockray (Louis Darling and Joanne Scribner’s illustrations feature prominently elsewhere):

“Put together, these three illustrations create a zooming-out effect, from Ramona slumped angrily in her chair, to Mrs. Kemp standing over her, to Uncle Hobart trying to make peace between the older woman and the girl. […] This moment could also be understood as a mental zooming out, an expansion of understanding. Ramona suddenly realizes that adults have their own feelings about children, feelings that aren’t always nice.”

The things that happen in Ramona’s mind and Ramona’s world are not always nice. Ramona isn’t always nice either. But reading about her as a girl was like spending time with a friend. We’re still pretty tight. Rereading her as an adult is like a “mental zooming out, an expansion of understanding” as I trace the unexpected complexities of Cleary’s ordinary stories.

Beverly Cleary left her handprints all over me as a young reader and, even now, I’m grateful for the inked trail she left behind.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Reading and Revisiting Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby Stories appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 8, 2022

Growing up With Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women in India

“Some books are so familiar, reading them is like being home again,” says Jo March, to her best friend, Laurie, as she picks up a volume of Shakespeare. That is exactly the kind of feeling that Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women evokes in me — a book that was a steadfast friend in my growing up years — one that I read and reread through my schoolgirl days in India.

Memories come back of lying on my stomach on a cold stone floor, on a hot summer day, with Little Women in one hand and homemade ice cream, tasting mainly of frozen Bournvita (an iconic nutritional beverage in India), in the other.

Once the last cold bit of ice cream slid down the throat, it was time to find a cushion to rest one’s head on and be transported into the magical tale of the March sisters and Marmee, Laurie, the senior Mr. Lawrence, Papa March, Mr. Brooks, Professor Bhaer, Hannah, and the formidable Aunt March.

All the characters are etched so well that they stay in one’s memory forever, even though some of them flit in and out of the story.

I grew up with educated parents, in a household where simple living, recycling, and not wasting resources was a message that was unconsciously absorbed.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Going to a Catholic school, there was an awareness created about the poor, as we were always asked to donate unneeded clothes, prepare medicine packets, and the like. As a Girl Guide, visits to Jamshedpur’s Cheshire Home (a nonprofit spread across India that’s dedicated to assisting those with disabilities and senior citizens) was a must, so there was an identification with Mrs. March’s charity work, in which she wanted to involve her daughters.

In my peer group, my reader friends all read Little Women — it was like a rite of passage. Even now, decades later, we speak of these books.

While growing up, my friends and I indulged in make-believe and play adaptations as the March sisters did. I had a strong bond with my sister as well as my entire family, echoing the universal sentiments portrayed in Little Women.

I had yet to find my writing voice, and my ideas about becoming a writer were still nascent, I couldn’t help but identify with Jo March when she voiced her ambitions:

“I want to do something splendid before I go into my castle—something heroic, or wonderful — that won’t be forgotten after I’m dead. I don’t know what, but I’m on the watch for it, and mean to astonish you all, some day. I think I shall write books, and get rich and famous; that would suit me, so that is my favorite dream.”

Jo also admitted to being flawed, which made her more relatable. It wasn’t difficult to find commonality with the other three sisters, but with Jo, the identification seemed complete.

. . . . . . . . .

10 Writers Who Were Inspired by Jo March

. . . . . . . . .

Alcott modeled Jo on herself and often spoke through her character. Jo says things like, “I’m happy as I am, and love my liberty too well to be in a hurry to give it up for any mortal man.”

Alcott was clearly an author ahead of her time, as she didn’t make a pushover of any of the sisters. Meg is portrayed as a pleasant girl that every man could fall in love with, but she also has strong opinions, as when she tells Jo, “Just because my dreams are different than yours, it doesn’t mean they’re unimportant.” Loving, kind Beth, who always thinks of others, is also shown as having a unique viewpoint.

I started out not caring too much for Amy, the pampered youngest child, who in her younger days could come across as vain, with petty preoccupations. But she grew on me with some of her witticisms and wise words, and in her acceptance of Laurie as a husband, despite knowing that he had been madly in love with her older sister.

She tells him, “Love Jo all your days, if you choose, but don’t let it spoil you, for it is wicked to throw away so many good gifts because you can’t have the one you want.”

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Readers suffered over Jo’s rejection of Laurie, as in their hearts was hope for them to be together always. But then, you can only be filled with respect for Jo’s determination and her desire to do something more with her life than to just settle down into matrimony.

“Women, they have minds, and they have souls, as well as just hearts. And they’ve got ambition, and they’ve got talent, as well as just beauty. I’m so sick of people saying that love is all a woman is fit for.”

Alcott portrays Jo as an emancipated woman, always questioning the lot of women:

“I find it poor logic to say that because women are good, women should vote. Men do not vote because they are good; they vote because they are male, and women should vote, not because we are angels and men are animals, but because we are human beings and citizens of this country.”

Marmee’s genuine, self-reflective nature as a strong, supportive woman comes through when she confesses to Jo about her lifelong struggles with a quick temper. That’s something Jo grapples with as well. It’s nice to see the humanizing portrait, written at a time when mothers were always supposed to be portrayed as perfect paragons of virtue.

. . . . . . . . .

You might also like:

Little Women: A Book I Come Back to For Comfort and Guidance

. . . . . . . . .

Professor Friedrich Bhaer, the tutor who befriends Jo when she goes to New York to take up employment, is a masterstroke on the part of the author. The Professor in encouraging of Jo’s literary talents but isn’t above telling her the truth about her writing.

It’s his push that prompts Jo to move from penning stories about blood and gore because they pay well, to writing from the heart. This eventually pays off in terms of getting published (much like it did in Louisa’s real life), turning Jo into a respected author.

Seeing Professor Bhaer as competition to Laurie made me resent him at first. Laurie’s high spirits and rapport with Jo seemed to be missing. It took me a while to figure that Alcott intended him to be a perfect foil for Jo.

I was so enamored with Little Women that I went on to read all the sequels in serial order starting with Good Wives (originally published as a separate sequel, it eventually became part of Little Women in one volume), Little Men, and Jo’s Boys. All of them enthralled me, though none were quite equal to Little Women.

In my formative years, the story of a family that didn’t have much money, but were happy and contented and had fun, stayed in my mind. Perhaps it was the magic of growing up with Little Women that gave it a special perspective.

Jo’s determination to be a writer and her one-track approach has always spoken to me, especially seeing her doggedness bear fruit. This gives hope to all writers.

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

. . . . . . . .

How Louisa May Alcott Came to Write Little Women

. . . . . . .

The post Growing up With Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women in India appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 6, 2022

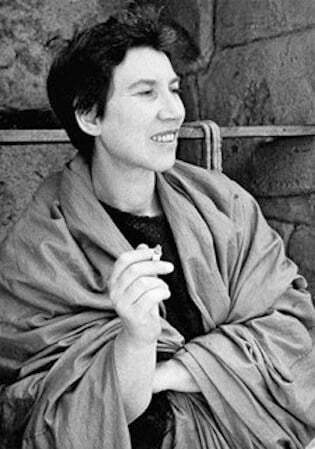

Natalia Ginzburg, Italian Novelist, Essayist, and Playwright

Natalia Ginzburg (July 14, 1916 – October 7, 1991) is considered among the best Italian writers of the post-World War II generation. Her vast literary legacy of novels, essays, plays, and nonfiction captures the devastation endured by war survivors.

In her works, the reader is struck by the imagery and near lyricism as she describes the mundane details and personal catastrophes that define life under political oppression. It has been said of Ginzburg that she “wrote like a man,” given that she was unsentimental in portraying the historic, violent traumas she witnessed.

Early life

Born Natalia Levi in Palermo, Sicily, she grew up under the iron heel of Mussolini’s fascism in the 1930s. She was the youngest of five children of Giuseppe Levi and Lidia Tanzi. For several generations on both sides of the Levi and Tanzi family branches, the family had an inordinately high number of brilliant minds and renowned achievers in the arts and sciences.

When Natalia was three years old, the family relocated to Turin, Italy. Giuseppe, a renowned neuroanatomy professor. Took a position at the University of Turin. In the 1930s and 940s, Turin was the center of anti-fascist activity in Italy — and every member of the Levi family was an active member of the Italian underground Resistance.

Following the Levi family tradition of brilliant minds and high achievements, Natalia started writing and publishing in adolescence. Her first book, a novella titled Il Bambini was published in a distinguished Florentine magazine when she was eighteen. It was released under a pseudonym to hide her Jewish identity.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A family of anti-fascist activistsBeing Jewish and outspoken against the Italian fascists, the Levi family was brutally retaliated against by the local fascist authorities. Giuseppe Levi lost his job and each of Natalia’s brothers was intermittently arrested for seditious acts. Yet despite the risk, the Levi family continued their anti-fascist work.

In 1934, Natalia’s brother Mario, a journalist, became an unwitting hero when he and an associate were caught at the Swiss border attempting to bring anti-fascist literature into Italy. As his colleague was being arrested, Mario jumped into the Tresa river and swam to safety on the Swiss shore while wearing his overcoat.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Marriage to Leone GinzburgThe most renowned and effective Resistance fighter in Turin was Leone Ginzburg, a native of Odessa, Ukraine. Ginzburg was a professor of Russian literature at the University of Turin and a close friend of the Levi family.

Despite the coming World War, Leone and Natalia were married in 1938 — a testament to the hope of a peaceful future, and the great power of love and family. The couple had three children, the oldest of whom, Carlo Ginzburg, is currently an eminent historian at the University of California Los Angeles.

Two years after they were married, Leone was sent into confino, (internal exile). He and Natalia were sent to the isolated and very poor countryside of Abruzzi. The fascists were convinced that by removing Ginzburg from the political activity in Italian cities, he would cease to be effective.

But despite his confino, the fascist authorities continued to fear Ginzburg’s organizing power and popularity with the Italian people. Ginzburg was a resistance leader who did not abandon his work despite the risk to his and his family’s life.

After Mussolini was deposed in 1943, Leone and Natalia returned to Rome to work on an underground press. Five months later, Leone disappeared. Natalia later found out he had died in prison of “cardiac arrest,” the medical term given when a prisoner dies of torture. She recalled:

“Arriving in Rome, I breathed a sigh of relief believing that a happy period was about to begin for us. I didn’t have any reason to believe this, but I did. We had a place to stay near the Piazza Bologna. Leone was the editor of a clandestine paper and was never home. They arrested him twenty days after our arrival and I never saw him again.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Natalia Ginzburg page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

After Leone’s death, Natalia stayed in Rome and worked for Einaudi Publishers as an editor. She was the first Italian translator of Proust’s Swann’s Way and found great satisfaction working and befriending other renowned Italian writers, including Carlo Levi, Primo Levi, Elsa Morante, and Italo Calvino.

The 1950s and 1960s were the most prolific years in Natalia Ginzburg’s writing career. Her best work was written in this period, including Valentino (1957), The Little Virtues, (1962), Voices in the Evening (1961), and Family Lexicon, (1963). She married Gabriele Baldini, with whom she was together from 1950 to 1969.

Family Lexicon was the recipient of Italy’s 1963 Straga Prize (the Italian version of the American Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award). Family Lexicon was published as a novel, and, despite the resemblance to the Turin household of her youth in the 1930s and 1940s, Natalia was adamant that it was a work of fiction.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

LegacyThrough all of her copious writings and life as a public intellectual in Italian culture, Natalia also remained an activist. In the last decade of her life she became politically active and was elected as an independent left-wing deputy in 1983. She was reelected in 1987. She was motivated by a profound sense of justice, and championed causes that affected impoverished Italian populations the most, such as food prices and legal representation for crime victims.

Finding herself uncomfortable with the limitations of party politics, Natalia retired from this pursuit. She spent the last three years of her life in Rome, where she died peacefully at the age of seventy-five in 1991.

Natalia Ginzburg and her fellow Italian writers from the post-World War II generation have been experiencing a renaissance for the past decade. There have been reissues of their work with new translations and new introductions. These include a reissue of Valentino and Sagittarius by the New York Review of Books in 2020 in a single volume. At a lecture to launch this publication, Cynthia Zarin and Jhumpa Lahiri paid homage to the life and works of Natalia Ginzburg.

With so many of her works available in English translation, Natalia Ginzburg is an esteemed author worth discovering.

Contributed by Nancy Snyder, who writes about women writers and labor women. After working for the City and County of San Francisco for thirty years, she is now learning everything about Henry David Thoreau in Los Angeles.

More about Natalia GinzburgFor a more detailed listing of Natalia Ginzburg’s works, including essays, plays, and names of translators, follow this link.

Selected novels and short stories

La strada che va in città (1942); English translation: The Road to the City (1949)È stato così (1947); English translation The Dry Heart (1949)Tutti i nostri ieri (1952); English translation: A Light for Fools / All Our Yesterdays (1985)Valentino (1957); English translation: Valentino (1987)Sagittario (1957); English translation: Sagittarius (1987)Le voci della sera (1961); English translation: Voices in the Evening (1963)Lessico famigliare (1963); English translation: Family Lexicon (2017)Famiglia (1977); English translation: Family (1988)La famiglia Manzoni (1983); English translation: The Manzoni Family (1987)La città e la casa (1984); English translation; The City and the House (1986)More information and sources

Rediscovering Natalia Ginzburg (The New Yorker) Jewish Women’s Archives Natalia Ginzburg’s Radical Clarity (The New Republic) If Ferrante is a Friend, Ginzburg is a Mentor (The Guardian) Wikipedia Reader discussion of Natalia Ginzburg’s works on Goodreads. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Natalia Ginzburg, Italian Novelist, Essayist, and Playwright appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 3, 2022

Pregnancy in Classic Novels by Women Authors: A Transgressive Theme

After reading a memoir of high-risk pregnancy by a friend (more about that ahead), I got to thinking about the prevalence of pregnancy in classic novels by women authors as a central theme.

Of course, many there are many instances of female characters in novels (both by male and female authors) bearing a child or miscarrying, but pregnancy itself is rarely more than quickly touched upon.

Reliable birth control was nonexistent not so long ago; yet fictional pregnancies, other than the seduction and abandonment trope, aren’t all that common. Her First Time: Seduction and Loss of Innocence in 1920s Women’s Novels presents several classic titles in which the heroine becomes pregnant (usually outside of marriage), with various outcomes.

In a Guardian article titled “Why does literature ignore pregnancy?” Jessie Greengrass observed that while exploring pregnancy as a theme is more prevalent than it once was, it still seems transgressive:

“Women’s bodies can be many things. They can be mirrors, weights, rewards; but so often they are seen from outside. Experiences that are unique to them remain anomalous, smoothly impenetrable, like bubbles of water to which significance refuses to adhere. What could we possibly learn about being human from that which only happens to half of us?”

Even so, more contemporary novels than ever have presented the theme of pregnancy, though often in apocalyptic ways. For more upbeat stories of pregnancy in fiction, one has to turn to romance novels. But I suppose there’s no drama in an uneventful pregnancy, is there?

. . . . . . . . . . .

Knocked Down is available on Bookshop.org*, Amazon*

and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . . . .

That brings me back to the memoir by my friend and colleague, Aileen Weintraub. Knocked Down: A High-Risk Memoir, as the title implies, is about a high-risk pregnancy, but it’s much more than that. As I wrote in the blurb I provided for the book:

“Knocked Down poignantly and often hilariously reminds us that no one is exempt from life’s unexpected curveballs. Aileen Weintraub weaves her wry wisdom into this chronicle of how the choices we make can collide with circumstances beyond our control. This fast-paced memoir of a woman who is forced to slow down is proof positive that precarious situations can be overcome with family, faith, and especially love.”

In turns touching and funny, Knocked Down brought back memories of leaving NYC for the Hudson Valley, deciding to have babies after insisting that I didn’t want children, dealing with my Jewish Mother (and becoming one). It’s so much about what it means to be female — what we give up, what we gain.

It may not be a work of fiction, but Knocked Down was what sparked this train of thought about pregnancy as a theme in classic novels, a rabbit hole that was fascinating to go down. And now, on to the novels …

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Charlotte Temple by Susanna Rowson (1790)

Charlotte Temple by Susanna Rowson (1762 – 1824) was the best-known work by this American-British author. It was also America’s first best-selling novel. With its themes of seduction, abandonment and remorse, it sparked a great deal of controversy in its time. Yet it remained the most widely read novel of the first half of the nineteenth century.

The story is about the betrayal of Charlotte, just fifteen years old, and a student in an English boarding school. She meets secretly with two British officers who are about to set sail for America to take part in the Revolutionary War.

The night before she is to return to her family home to celebrate her birthday, she is persuaded to go with the officer with whom she has fallen in love. He promises to marry her when they get to America. This promise, of course, is broken.

Laden with heavy moralizing, Charlotte is made to suffer and pay over and over for her unhappy adventure. In the end, she gives birth to a baby girl and dies of malnutrition. What’s worse about this melodramatic plot is that Rowson claimed it was based on the true story of someone she knew.

. . . . . . . . . .

Summer by Edith Wharton (1917)

Summer by Edith Wharton, a novella, was one of her personal favorites. She called it the “hot Ethan,” referring to her 1911 novella, Ethan Frome. It’s unclear if she was speaking of the book’s setting in the summer season, Charity’s sexual awakening, or both.

Charity, who was adopted by a small-town lawyer named Royall and his wife as a baby, continues to live with him after his wife passes away. He begins to look at Charity in a new light once she becomes a young woman, which deeply disgusts her. While working at the local library, she meets a young architect passing through. He seduces and abandons her, leaving her pregnant.

“Charity, till then, had been conscious only of a vague self-disgust and a frightening physical distress; now, all of a sudden, there came to her the grave surprise of motherhood.”

Lawyer Royall, initially furious at the mess Charity finds herself in, becomes a comforting ally.

“Mr. Royall seldom spoke, but his silent presence gave her, for the first time, a sense of peace and security. She knew that where he was there would be warmth rest, silence; and for the moment they were all she wanted.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Gone With the Wind by Margaret Mitchell (1936)

Pregnancy and childbirth play minor, yet pivotal roles in Margaret Mitchell‘s Gone With the Wind. The widowed Scarlett was left with a son by her first husband; after marrying Rhett Butler, she gives birth to the adored Bonnie Blue. Then, she wants nothing more to do with pregnancy, lest it spoils her seventeen-inch waist.

Following an angry encounter, Rhett forces himself upon Scarlett. Controversially, this incident of marital rape seems to turns Scarlett’s pretty head; in the morning, she’s practically purring. He nonetheless decides to leave Scarlett, and in the interim, Scarlett discovers that she’s pregnant (her third pregnancy in the book; her second in the film).

When Rhett returns after three months, he’s still in a foul mood, souring Scarlett’s as well. When she informs him of the pregnancy, he says, “Cheer up, maybe you will have a miscarriage.” Enraged, Scarlett takes a swing at him. When Rhett steps out of the way, Scarlett loses her footing and tumbles down the long staircase. She does miscarry and nearly dies.

Melanie, the angelic wife of Ashley Wilkes (the man with whom Scarlett professes to be in love) becomes pregnant with their second child, though her doctor warns her against it. Sure enough, she grows weak after a miscarriage. Summoned to Melanie’s bedside in her final moments, Scarlett is made to realize what’s at stake in making deathbed promises to one she had until then considered a rival.

. . . . . . . . .

The Door of Life by Enid Bagnold (1938)

It’s surprising to discover that Enid Bagnold, the author best known for the classic horse story National Velvet, wrote what is considered one of the first novels centered on pregnancy and childbirth. Oddly titled The Squire when first published in England, it was recast asThe Door of Life for its American publication.

This semi-autobiographical novel is described as an almost meditative reading experience from the perspective of the expectant mother, who is soon to give birth to her fifth child. A 1938 review observed:

“Those to whom the act of giving birth to a new human is fraught with terror and dread will see here that it is possible for it to be a wonderful and moving experience. We have never before read of the birth of a baby where all anguish was removed and a deep, fundamental joy was put in its place.”

Even by today’s standards, that sounds so refreshingly positive!

. . . . . . . . . .

The Tenth Month by Laura Z. Hobson (1970)

We’ll let the publisher of this 1970 novel about single motherhood describe it, since they did it so ably:

In her first great best seller, Gentleman’s Agreement, Laura Z. Hobson dealt memorably with the prejudice of antisemitism. In The Tenth Month, Hobson deals with another kind of prejudice — one far more subtle, emotional, and pervasive — the prejudice that society is guilty of when it forces a single rigid code of morality on all human beings.

The Tenth Month is the story of Theodora Gray, a woman who has been told she can never have children, but now —after ten years of divorce and at the amiable end of one of her infrequent affairs —suddenly discovers that she is pregnant.

Dori Gray is not bothered by feelings of shame or self-reproach. She is delighted, and determined to have her baby. But another kind of dilemma poses itself: even before she is certain that she is pregnant, Dori falls in love with Matthew Poole, a lawyer who is married and a devoted father of two children.

Should she tell him she is pregnant by another man? If she tells him, how will he take it? Will Dori become another “problem case,” or will Matthew’s strength and humanity prevail and let him respect the rightness of her decision to have her child?

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Pregnancy in Classic Novels by Women Authors: A Transgressive Theme appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 25, 2022

Vera Caspary’s Ladies and Gents, and Women’s Flapper Novels of the 1920s

Women’s flapper novels of the 1920s captured the essence of a fleeting era known as the Jazz Age and Roaring Twenties. This look at a largely forgotten genre of fiction, many written by women, is excerpted from the forthcoming A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth. Reprinted by permission.

The 1920s was the age of the flapper — the free, single, modern woman unencumbered by long skirts or long hair who could go anywhere, do anything; she did not have to settle for what her mother had to settle for.

She could change her life and entire social and economic situation, if only through marriage, and even change her physical appearance. The Flapper magazine, with its slogan “not for old fogeys,” was based in Vera Caspary’s hometown of Chicago and started in 1922. The opening issue made its stance clear.

“Greetings, flappers! All ye who have faith in this world and its people, who do not think we are going to the eternal bowwows, who love life and joy and laughter and pretty clothes and good times, and who are not afraid of reformers, conformers, or chloroformers — greetings! … Thanks to the flappers the world is going round instead of crooked, and life is still bearable. Long may the tribe wave!”

Gertrude Atherton’s novel Black Oxen, the bestselling novel of 1923, features the flapper Janet Oglethorpe, portraayed in the film of the same year by Clara Bow, with whom Caspary’s character Rosina in Ladies and Gents identifies. Oglethorpe herself gives a good definition of the fashionable woman of her age.

Being a rank materialist myself, I know ‘em like a book. The emancipated flapper is just plain female under her paint and outside her cocktails. More so for she’s more stimulated. Where girls used to be merely romantic, she’s romantic—callow romance of youth, perhaps, but still romantic—plus sex-instinct rampant. At least that’s the way I size ‘em up, and its logic. There’s no virginity of mind left, mauled as they must be and half-stewed all the time, and they’re wild to get rid of the other. But they’re too young yet to be promiscuous, at least those of Janet’s sort, and they want to fall in love and get him quick.

In Atherton’s next novel, The Crystal Cup, 1925, the young Gita from the aloof old Carteret family dresses and behaves like a boy but denies to her disapproving grandmother that she is a flapper.

“You do all you can to distort and destroy the Carteret beauty in your attempt to look like a boy. The Carteret women were all dashing brunettes, but feminine. Otherwise they never would have had men crawling at their feet, generation after generation.”

“If men crawled at my feet—which they don’t do these days, anyhow—I’d kick them out of the way. And if I were a man myself—and I wish to God I were—I’d see women to the devil before I’d make a fool of myself——”

“I don’t like your language. I don’t like your voice. I don’t like your bobbed hair——”

“My hair is not bobbed.” …

“Are you a specimen of the flappers all these magazines and novels are full of?”

“I am not. Silly little females. Besides, I’m twenty-two.”

“I can’t make out whether you seem to hate men or women more, and you won’t give any reason.”

“I don’t hate women. I only resent being one.”

The Flapper Wife: The Story Of A Jazz Bride by Beatrice Burton (1925) made into the silent film His Jazz Bride (1926) and its sequel Footloose (1926), feature the hedonistic young May Seymour who is looking to marry a millionaire but settles for a lawyer instead. For a while, anyway. Then May gets bored with married life and starts to have affairs with other men, refusing to settle down.

Nalbro Bartley’s The Fox Woman (1928) also concerns the predatory 1920s female. “Everyone knows the fox woman. She is at every club – in every set – at every resort. You see men gathered around her – you see groups of women talking about her. She is a type in the modern world of Society. Her desire is always to dominate, possess. Always exacting love, never returning it – plunging men into despair, into jealousy, finally into hatred.”

Like Ladies and Gents, Janet Flanner’s The Cubical City (1926) is about a woman succeeding in this world of show business, though as a costume designer rather than as a dancer. The owner of the New York theatre for which Delia Poole designs the showgirls’ costumes tells her that everything had changed after prohibition: the market had become more sophisticated, more discerning.

“What we got in our line is mostly girls. In the old days if they was pretty it used to be enough. Now we gotta put ‘em across,” he had added with regret. “We gotta have expensive lights. We gotta have good music. Beautiful sets. Ideas. They need everything nowadays since life ain’t so simple. Since prohibition everybody’s got wine and we furnish the women and song.”

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

In Edith Wharton’s Twilight Sleep, among the top ten bestselling novels of 1927, is set in Jazz Age New York. The three heroines, including a mother and daughter, go as far as trying to change their bodies to look like the flapper ideal.

“The modern girl was always free, was expected to know how to use her freedom. Nona’s independence had been as scrupulously respected as Jim’s; she had had her full share of the perpetual modern agitations. Yet Nona was firm as a rock: a man’s heart could build on her. If a woman was naturally straight, jazz and night-clubs couldn’t make her crooked.”

Laura Lou Brookman wrote several books about this kind of strong, independent, even predatory modern woman, including The Heart Bandit (1928). “The thrilling and romantic adventures of a beautiful young ‘man hunter.’” The full-page newspaper ad for it featured a drawing of a short-haired, big-eyed woman in a heart shape and the words:

Ask yourself these questions.

Does every pretty Flapper coolly look over the men about her, select one or several victims – and begin a ruthless, subtle campaign, using all her feminine lure and wiles to attach his heart – and purse?

Can the Flapper tactics really win a man’s heart?

Do bare knees and a vanity case win a wedding ring?

Is the motto of the girl of today “Get Your Man”?

Is the modern maid a man hunter?

Similarly, the dust jacket of Ethel Hueston’s Birds Fly South (1930) says of its heroine:

P.T. is a flapper. She lives in a New York hotel for the sake of a Good Address. She wears slinky clothes with a swishy little flare of red silk at the right knee. She lies in a tepid salt bath for one hour daily to preserve youth, beauty, suppleness. She makes it a point of business to pick up strange men who pay for her luncheon. She is ready to marry a stranger on a bottle of champagne. But – if you think you are going to find her a Horrible Warning, a Terrible Example of Flaming Youth, read further. P.T. is really the most charming among Ethel Hueston’s many charming heroines.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Perhaps the most famous novel featuring the thoroughly modern 1920s flapper was Gentlemen Prefer Blondes by Anita Loos, the second-bestselling novel of 1926. Loos’ narrator, Lorelei Lee, is somewhat similar to Caspary’s third person Rosina in that her parents want her to be serious but she prefers frivolity and freedom, traveling the world in search of excitement. However, Lorelei does decide to write a book in the form of a diary, given to us unedited, spelling mistakes and all.

A gentleman friend and I were dining at the Ritz last evening and he said that if I took a pencil and a paper and put down all of my thoughts it would make a book. This almost made me smile as what it would really make would be a whole row of encyclopediacs. I mean I seem to be thinking practically all of the time. I mean it is my favorite recreation and sometimes I sit for hours and do not seem to do anything else but think.

So this gentleman said a girl with brains ought to do something else with them besides think . . . And so when my maid brought it to me, I said to her, “Well, Lulu, here is another book and we have not read half the ones we have got yet.” But when I opened it and saw that it was all a blank. I remembered what my gentleman acquaintance said, and so then I realized that it was a diary. So here I am writing a book instead of reading one.

Like Rosina in Ladies and Gents, and like most young women at the time, Lorelei’s dream is to be in the moving pictures – as Vera Caspary’s dream was to write for them and in which she succeeded beyond her wildest dreams. “Gentlemen always seem to remember blondes. I mean the only career I would like to be besides an authoress is a cinema star and I was doing quite well in the cinema when Mr. Eisman made me give it all up,” says Lorelei.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Vera Caspary

. . . . . . . . . . .

Soon after Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was released, and well before Caspary’s Ladies and Gents was published, the death of the flapper was being widely announced. An article in the New York Times of February 16, 1928, was titled “No More Flappers.”

In thirty-five cities the flapper has been surveyed and found wanting. Investigation reveals, not that she is lacking in certain desirable qualities, but that she has actually disappeared. Surely you have missed her. Who has seen in recent days this creature, described by the league as the typical post-war flapper? Her hair was furiously frizzled. Her smoking was overenthusiastic. Her chewing gum was too loud and too large. Her vocabulary was imported direct from the trenches. She was startlingly picturesque – and now she is no more.

In her place is a delicately made up young woman of great poise and dignity. She has selected a few attributes of the flapper for preservation – the latch-key, the lipstick and the liquor. But she makes such discreet use of them that she is no longer an offense to the world at large. Instead of flaunting her freedom, she makes it more valuable by using it quietly.

Still, the world of Broadway theatres, shows and revues, the world that Rosina moves in through Ladies and Gents moves up and moves through was highly successful throughout the prohibition-era 1920s. Caspary describes this world of New York Jazz Age theatre beautifully in her autobiography.

Broadway glittered with theatres. It was a time of richness when the plays, the playwrights and the players offered exuberant and intelligent entertainment. The show music was by Gershwin, Kerns, Youmans, Berlin and Richard Rogers. Jazz was fresh, good bands played in cabarets or small, elegant nightclubs where tall fellows in tails waltzed and tangoed with sylphs in memorable chiffons. Revues were of two kinds – big, vulgar and funny in the Ziegfeld or Schubert manner, or small, witty satires disrespectful of politicians, artists and heroics.

Unlike Lorelei Lee, unlike Janet Oglethorpe, unlike F. Scott Fitzgerald’s flapper heroines Isabelle Borgé and Daisy Buchanan and indeed unlike Fitzgerald’s wife Zelda, whom he named “the first American flapper,” Rosina in Ladies and Gents does not come from money or from high society. (The little-known short story collection Flappers and Philosophers, (1920) was Fitzgerald’s first published book.)

And unlike Helen Taylor in Thyra Samter Winslow’s Show Business (1926) – also a novel about a young woman climbing to the top of the New York musical theatre scene – she does not come from a narrow, conservative small town society. Indeed, Rosina Scaduto Monticelli’s circus family are situated outside society altogether, being Italian acrobats, itinerant and literally surrounded by circus freaks.

In this, Rosina is somewhat similar to Magnolia from Edna Ferber’s Show Boat (1926), who “learned to strut and shuffle the buck-and-wing from the Negroes whose black faces dotted the boards of the southern wharves,” and her daughter Kim, who becomes a famous actress in New York City.

Rosina is also to some extent a successor to Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie (1900), who like Rosina, progresses from ingénue to queen of the stage but unlike her ends up alone.

“Here was Carrie, in the beginning poor, unsophisticated, emotional; responding with desire to everything most lovely in life, yet finding herself turned as by a wall. . . Amid the tinsel and shine of her state walked Carrie, unhappy.”

. . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Vera Caspary’s Ladies and Gents, and Women’s Flapper Novels of the 1920s appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 21, 2022

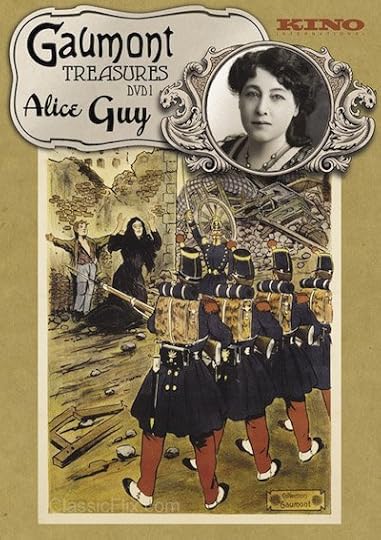

Alice Guy-Blaché, Pioneer of Early Cinema

Alice Guy-Blaché (July 1, 1873 – March 24, 1968) was a pioneering filmmaker of the early days of cinema, and the first woman to direct a film. One of the first filmmakers to make a narrative film, she was the only known female filmmaker in the world from 1896 to 1906.

Guy-Blaché directed, produced, or supervised about a thousand films, many of them short. When she died in 1968, many of her accomplishments had been erased from male-dominated film history books, but recent years have seen a revival of interest in her life and work.

Early years

Alice Ida Antoinette Guy was born in Paris to a Chilean father, Emile Guy, and a French mother, Marie Clotilde Franceline Aubert. The Guy family made their home in Santiago, Chile, where Alice’s four siblings were born and where Emile ran a bookshop and publishing company.

A smallpox epidemic in 1872 compelled the family to emigrate to France, where Alice was born the following year. When her parents returned to Chile soon after her birth, Alice was left in the care of her grandmother in Switzerland.

At the age of three, Alice returned to Chile. She spent the next two years with her family in Santiago before returning to France. She attended school at Veyrier, and later, went to a convent school at Ferney with her sister Louise.