Nava Atlas's Blog, page 28

April 22, 2022

The Matriarch by G.B. Stern (1924)

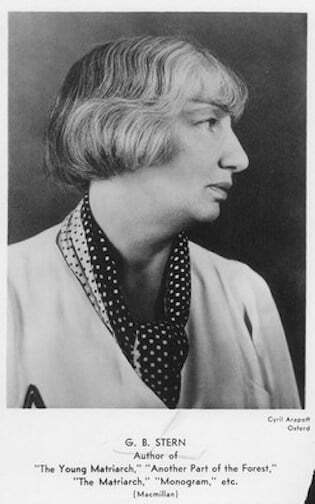

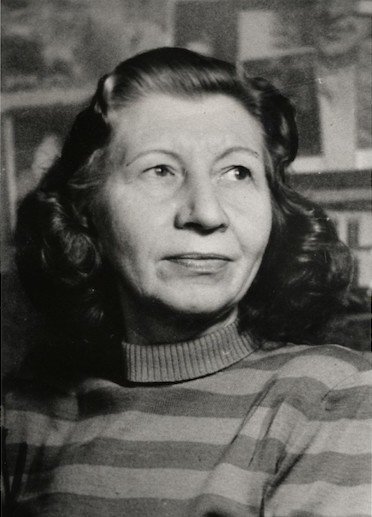

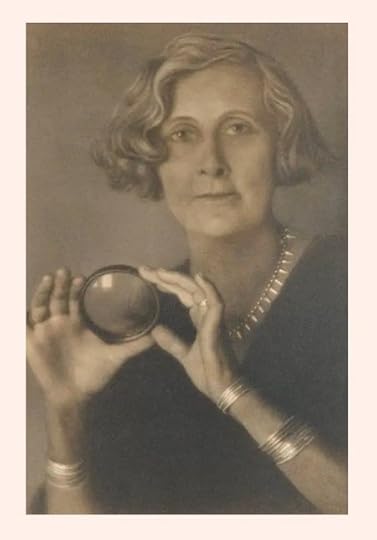

British writer G.B. Stern (1890 – 1973) published a five-volume Jewish family saga collectively entitled, confusingly, both The Rakonitz Chronicles, the first three volumes published together in 1932, and The Matriarch Chronicles in their expanded 1936 form.

This overview of The Matriarch, the first in a series and the best-known work by Stern is excerpted from A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth ©2022. Reprinted by permission.

Born in London as Gladys Bertha Stern, she was later Gladys Bronwyn, and wrote mainly under her initials. She was a friend of Somerset Maugham, H.G. Wells, Rebecca West, and Noël Coward, she wrote over forty novels, as well as plays, short stories, criticism.

Extremely prolific and largely forgotten, Stern was the author of over fifty novels and memoirs, the best known of which were the five novels collectively known as the Matriarch series: The first was The Tents of Israel (1924), published in the U.S. and later known more widely as The Matriarch.This was followed by the other volumes in the series: A Deputy was King (1926), Mosaic (1930), Shining and Free (1935), and The Young Matriarch (1935).

As noted above, the first three books were collected in a single volume as The Rakonitz Chronicles, in 1932, and all five volumes were finally published together as The Matriarch Chronicles. Stern also published a play version of The Matriarch in 1931. Rakonitz was the name of Stern’s maternal grandfather, and the Chronicles are loosely based on her own family.

According to Rabbi Julia Neuberber’s introduction to the Penguin edition, Stern did not like the word “Jew” and preferred “Israelite.” In 1947, Stern converted to Catholicism.

Like Vera Caspary’s Thicker Than Water, though far longer, the Chronicles are a family saga covering a dramatically changing world, beginning when the Rakonitz family diaspora begins at the end of the nineteenth century.

All the Rakonitz women were happiest in Cosmopolis. Imagination cannot easily picture them in a setting of brown ploughed field on a whipped grey morning after storm. Instead, spacious drawing rooms, with parquet floor throwing back the glitter from the Venetian crystal candelabra, brocade hangings, and a polished grand-piano – these were more natural than nature to Babette and her descendants. They scattered from Vienna, certainly, but always to other big cities, capitals of the world; Paris, Budapest, Constantinople, Venice, London – Anastasia was the first Rakonitz in London.

. . . . . . . . . . .

G.B. Stern in 1949

. . . . . . . . . .

Indomitable, cosmopolitan Anastasia, who presides over the family from her exotic home in West London is The Matriarch of the title, “at the age of sixty, in full blossom, at the very height of her mental and physical powers, brilliant, tireless, despotic, at the apex of the family triangle.” Anastasia has not always been the Matriarch, however:

“The Matriarch first began to assert itself in Anastasia, when she insisted that her eldest son and her eldest son’s wife – poor, pretty little Susie Lake, who had so longed for a home of her own – should, as a matter of course, well with her in the same house, sharing her table and controlled by her wishes.”

For Susie, coming from an English suburb, “into the very Rakonitz stronghold itself, into the house of the Matriarch, life was a tragedy and the bewilderment.” Instead of her own house, Suzie now has only her own room, which does not at all seem like her own.

“Heavily furnished by more exotic and profuse taste than her own, on the top floor of a house resembling some foreign palace within, with its antiques used as though they were commonplace; heirlooms thickly clustered about with anecdotes less conventionally romantic than broadly ludicrous; treasures brought from distant cities, not via the medium of shops, but by real people – real relations; dark, heavy furniture, and chandeliers that were a thousand dropping crystals that swayed and reflected light; portraits of ancestors . . . No wonder Suzie marveled how such a fantastic caravanserai could still manage, from the outside, to look almost like every house in Granville Terrace.”

Both metaphorically and physically, the incoming Jewish family have integrated, like Amy Levy’s, into formal, wealthy West London twentieth-century society but internally, behind, as it were closed doors, they are still Middle European, nineteenth-century Jewish. Anastasia’s daughter and youngest child, Sophie is as frightened of the Matriarch as her daughter-in-law Susie; always having given precedence to her older brothers, she feels ignored.

All she can do to assert her place in the family is to try to have a son. “If she did not bear a son who was also Anastasia’s first grandchild, she determined to kill herself.” Worse, she has married the wrong kind of man. “Not only a stranger, and a Gentile, but, from the point of view of Rakonitz, such a ludicrous stranger!”

Not only is he an Englishman, “and what was known as a profligate, without any sense of family,” he is “an artist by temperament, although not overmuch by virtue of work and creation; but carrying all the suspicious attributes of an artist as they were in the late nineteenth century.”

In the 1936, five volume-in-one re-issue of The Matriarch Chronicles, we are less than fifty pages into a book of nearly one thousand pages at this point; a Jewish family saga indeed. Stern dedicated it to John Goldsworthy, in admiration of his The Forsyte Saga; Caspary was a big admirer of the fictional Forsytes; when she first lived in London with Hope Skillman in the 1920s they visited Fleur Forsyte’s house in Belgravia – always the most expensive and exclusive part of London – and when she went back to live there again in the 1950s, far more financially secure now, she had was proud to tell Hope that she had a house round the corner from Fleur.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie on Amazon (US)*

and *

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also like:

Jewish Women in Novels by Early Jewish Female Writers

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Matriarch by G.B. Stern (1924) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 17, 2022

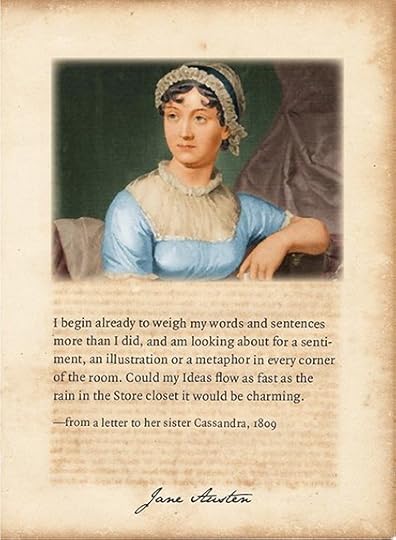

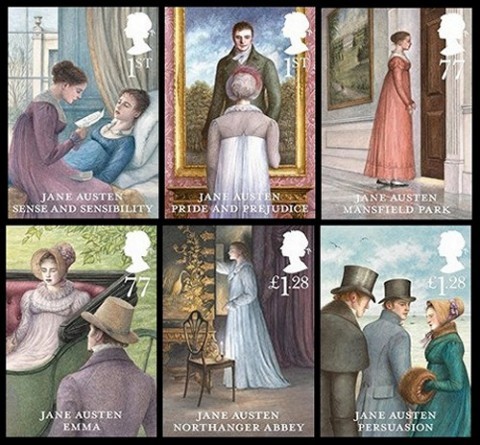

Jane Austen’s Childhood and Glimpses of Her as a Young Woman

Jane Austen by Sarah Fanny Malden (1889) offers an excellent 19th-century view of Jane Austen’s works, along with a handful of chapters on the life of this beloved British author. This excerpt, featuring one such chapter, offers glimpses of Jane Austen’s childhood and what she engaged with as a young woman.

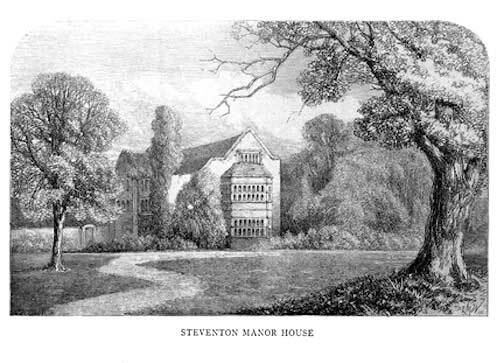

Born in Steventon, Hampshire (England), Jane (1775 – 1817) was part of a convivial middle-class family consisting of five brothers and her sister Cassandra, with whom she was very close. Her father was an esteemed rector. Jane spent the first twenty-five years of her life in Steventon, after which the family moved to Bath.

Mrs. Malden said of her sources, “The writer wishes to express her obligations to Lord Brabourne and Mr. C. Austen Leigh for their kind permission to make use of the Memoir and Letters of their gifted relative, which have been her principal authorities for this work.”

The 1889 publication of Malden’s Jane Austen was part of an Eminent Women series published by W.H. Allen & Co., London. The following excerpt is in the public domain:

The society at Steventon

The society immediately around Steventon when Jane Austen was growing up was neither above nor below the average of country society seventy miles from London.

It was not unusual for a country clergyman to find himself the only educated gentleman within a radius of some miles round his parsonage. But the dense ignorance of country gentlemen a hundred years ago is a thing of the past, and it could scarcely happen to any clergyman now to be asked, as Mr. Austen was once by a wealthy squire, “You know all about these things. Do tell us. Is Paris in France, or France in Paris? for my wife has been disputing with me about it.”

The Austens were not, however, dependent entirely on neighbors of this class for their social life, and whether, like Mrs. Bennet, they dined with four-and-twenty families or not, they certainly managed to have a good deal of pleasant society.

By birth and position the Austens were entitled to mix with the best society of their county, and though not rich, their means were sufficient to enable them to associate with the best families in the neighborhood.

Country visits were more of a business then than now; wet weather and bad roads and dark nights made more obstacles to social intercourse than we realize in these days; but a houseful of merry, cultivated young people, presided over by genial parents, is sure to be popular with its neighbors, and Jane Austen had no lack of society when she was growing up.

She was one of a most attractive family party, for they were all warmly attached to each other, full of the small jokes and bright sayings that enliven family life, and blessed with plenty of brains and cultivation, besides the sweet sunny temper that makes everyday life so easy.

. . . . . . . . .

A drawing of Jane by her sister Cassandra

. . . . . . . . . .

Steventon Rectory in Jane Austen’s girlhood was as cheerful and happy a home as any girl need have desired, and she remembered it affectionately throughout her life, unconscious how much of its sunshine she herself had produced, for in her eyes its brightness was mainly owing to her sister, Cassandra.

It was natural that two sisters coming together at the end of a line of brothers should draw much together, and from her earliest childhood Jane’s devotion to her elder sister was almost passionate in its intensity.

As a little child she pined so miserably when Cassandra began going to school without her, that she was sent also, though too young for school life; but, as Mrs. Austen observed at the time, “If Cassandra were going to have her head cut off, Jane would insist on sharing her fate;” and this childish devotion only increased with riper years.

From beginning to end Jane never wrote a story that was not related first to Cassandra and discussed with her; she literally shared every thought and feeling with her sister, and the two pleasant volumes of letters which Lord Brabourne has published show us how the intense attachment between the two sisters never waned throughout their lives.

All her warmth of heart and devotion to her family shine out in them, as well as her quick perception of character; and they sparkle throughout with quiet fun, and with humor, which is never ill-natured, while from first to last there is not a line written for effect, nor an atom of egotism or self-consciousness.

It is characteristic both of Jane’s self-abnegation and of her complete faith in her sister that, even after she was a successful authoress, she always gave Cassandra’s opinion first to anyone consulting her on literary matters, and if it differed from her own, she mentioned the fact almost apologetically, and merely as if she felt bound to do so.

If she did not actually pine for her sister’s presence after she was grown up, she certainly missed her, even in a short time, far more than most sisters, however affectionate, would do.

At twenty she is eager to give up a ball to which she had been looking forward, merely that Cassandra may return from a visit two days earlier than she otherwise could, and writes, “I shall be extremely impatient to hear from you again, that I may know when you are to return.”

At another time she reproaches her for staying away longer than she need have done, and entreats her to write oftener while away, declaring, “I am sure nobody can desire your letters as much as I do,” while every letter she receives from Cassandra is commented on with the same lover-like ardor, and received with the same delight, long after both the sisters had passed the romantic stage of girlhood.

“Excellent sweetness of you to send me such a nice long letter,” writes Jane, in 1813, when she was eight and thirty years old; and though doubtless letters were greater treasures then than now, it must be remembered that these and similar expressions are from a woman who was usually anything but “gushing” or “sentimental” in her language.

Wherever the sisters were they always shared their bedroom, and if Jane’s feeling was the clinging devotion of a younger to an elder sister, Cassandra certainly returned it with an intense sympathy and affection that never diminished in life or in death.

The sisters were educated together chiefly at home. Mr. Austen taught his sons in great part himself, and was well fitted to do so, but the higher education for women had not then been discovered, and the Austen girls were not better instructed than other young ladies of their day.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Jane’s special gift was skill and dexterity with her fingers; she was a first-rate needlewoman and delighted in needlework; she excelled also in any game or occupation that required neat-fingeredness; but she was no artist, and not a great musician, though far from a bad one.

Like Elizabeth Bennet, “her performance was pleasing, though by no means capital.” She was an excellent French scholar, and a fair Italian one; German was in her day quite an exceptional acquirement for ladies; and as to what was then thought of the dead languages for them, all readers of Hannah More must remember her bashful heroine who put the cream into the teapot and the sugar into the milk-jug on it being discovered that she read Latin with her father!

. . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy: Jane Austen’s Literary Ambitions

. . . . . . . . . . .

Jane Austen risked no such overwhelming discovery, but she was well acquainted with the standard writers of her time and had a fair knowledge of miscellaneous literature. Crabbe, Cowper, Johnson, and Scott were her favorite poets, though, rather oddly, she set Crabbe highest; and it was a standing joke in the family that she would have been delighted to become Mrs. Crabbe if she had ever been personally acquainted with the poet.

Old novels were her delight, and the influence of Richardson and Fanny Burney may be traced in some of her early writings. I have always thought that her criticism on the Spectator in Northanger Abbey proves that she could have known very little of Steele and Addison’s masterpieces; but tastes differ, and she may have been unlucky in her selections.

She always took pleasure in calling herself “ignorant and uninformed,” and in declaring that she hated solid reading; but her letters continually make mention of new books which she is reading, and there was a constant stream of literature setting through the rectory at Steventon, in which Jane shared quite as fully as any of the others.

An early and avid writer

The delight and pursuit of her life, however, from very early days, was writing, and she seems to have been permitted to indulge in this pleasure with very little restraint; all the more, perhaps, that no amount of scribbling ever succeeded in spoiling her excellent handwriting.

After she grew up to womanhood she regretted not having read more and written less before she was sixteen and urged one of her nieces not to follow her example in that respect; but there must have been many wet or solitary days in the quiet rectory life which would have been very dull for the child without such a resource, and posterity may rejoice that no one hindered Jane Austen’s inclination for writing.

How soon she began to produce finished stories is not certain, but from a very early age her writings were a continual amusement and interest to the home circle, where they were criticized and admired with no idea as to what they might lead.

Most young authors try their hands at dramatic writing some time or other, and Jane passed through this stage of composition when she was about twelve years old, though she never seems to have attempted it later in life.

Private family theatricals

It was not a style which could have suited her, but at the time she tried it the young Austens had taken a craze for private theatricals, and Jane’s plays are thus easily accounted for. [According to James Edward Austen Leigh, a nephew who later wrote a memoir of his famed aunt, Jane was between thirteen and sixteen at the time of this family pursuit.]

The corps dramatique consisted of the brothers and sisters and a cousin, who had become one of them under pathetically romantic circumstances. She was a niece of Mr. Austen’s, had been educated in Paris, and married to a French nobleman, the Count de la Feuillade. He was guillotined in the Revolution, and she, with great difficulty, made her way to England, where she found a home in the already well-filled rectory at Steventon.

She was clever and accomplished, rather un-English in her ways and tastes, and very ready to help in the theatricals, which, perhaps, would not have existed but for her. There was no theatre but the dining-room or a barn, and both actors and audience must have been limited in number; but plays were got up in which Mme. de Feuillade was the principal actress.

James Austen wrote brilliant prologues and epilogues when they were wanted, and Jane Austen looked on and laid in materials for the immortal theatricals of the Bertram family.

Space must have made it impossible for a Mr. Yates, a Mr. Rushworth, or the Crawfords to be among the Steventon actors; but there may have been a very sufficient spice of lovemaking throughout the business, for Mme. de Feuillade afterwards married Henry Austen, Jane’s third brother. It is probable that there were enough “passages” between them during the theatricals to interest a girl of Jane’s age keenly.

Meanwhile, something—perhaps the absurdly transparent mysteries in which some old comedies abound—suggested to her a little jeu d’esprit, which, slight as it is, shows her keen sense of fun and her close observation, for she has copied the style and manner of an old play very closely, even in the dedication.

The post Jane Austen’s Childhood and Glimpses of Her as a Young Woman appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 15, 2022

A 19th-Century Analysis & Plot Summary of Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Jane Austen by Sarah Fanny Malden (1889) offers an excellent 19th-century view of Jane Austen’s works. The following analysis and plot summary of Pride and Prejudice (1813) focuses on this beloved novel, which was Jane Austen‘s second to be published. It followed Sense and Sensibility, published two years earlier.

Mrs. Malden said of her sources, “The writer wishes to express her obligations to Lord Brabourne and Mr. C. Austen Leigh for their kind permission to make use of the Memoir and Letters of their gifted relative, which have been her principal authorities for this work.”

The 1889 publication of Malden’s Jane Austen was part of an Eminent Women series published by W.H. Allen & Co., London. The following excerpt is in the public domain:

Pride and Prejudice appeared in 1813 under its new and certainly better title (it had at first been called First Impressions), and Jane’s letters at the time are full of the unaffected interest which she always displayed in her own writings, mixed with her usual keen criticism. Jane’s opinion of her heroine, and of the first edition of the book is described in a letter to her sister Cassandra:

“I must confess, that I think her (Elizabeth) as delightful a creature as ever appeared in print, and how I shall be able to tolerate those who do not like her at least, I do not know. There are a few typical errors, and a ‘said he’ or a ‘said she’ would sometimes make the dialogue more immediately clear; but ‘I do not write for such dull elves’ as have not a great deal of ingenuity themselves.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Jane Austen

. . . . . . . . . .

No admirer of Elizabeth Bennet will wonder that her delineator could not find a satisfactory portrait of her, for she is a vary rare type of character; indeed, it is a distinguishing characteristic of Pride and Prejudice that both the hero and heroine are uncommon in every respect, and yet thoroughly lifelike.

A shade more of gaiety would have made Elizabeth a flippant, amusing, commonplace girl, just as a degree less intellect would have made Darcy as intolerable as Mrs. Bennet thought him. But Jane Austen had shaken off all tendency to exaggeration by the time she brought out Pride and Prejudice, and henceforth her characters are kept well within bounds.

We see in Darcy the man who has had everything to spoil him yet is really superior of being spoilt. He is handsome, wealthy, well-born, and of powerful intellect, and the adulation and submission he has always had from everyone about him wearies him into receiving such homage with cold indifference and apparent haughtiness, yet under this repellent exterior is a warm, generous, and tender heart, which is capable of great sacrifices for anyone he really loves.

Elizabeth Bennet is exactly the right wife for him, for, with a nature as capable of tenderness and constancy as his, she has all the simplicity, brightness, and playfulness which are wanting in him; yet from the day that she and Mr. Darcy first meet they take a mutual aversion to each other, and long after he has succumbed, and fallen in love with her, she is unconscious of his feelings, and continues to dislike him.

Elizabeth Bennet and her family

Elizabeth lives in Hertfordshire with a clever satirical father (whose pet she is), an intensely vulgar silly mother, and four sisters, of whom only one is her equal and companion: Jane and Elizabeth Bennet are as Cassadra and Jane Austen were to one another.

The Bennets, though well off, are not rich, and the daughters will be very poor, as their father’s estate is entailed to male heirs, and, at his death, goes to a distant cousin. This arrangement is a perpetual grievance to Mrs. Bennet, who cannot be made to understand the nature of an entail, and makes thereupon the remark which is so much truer than appears at first sights that “there is no knowing how estates will go when once they come to be entailed!”

Bad first impressions

The Bingleys, consisting of Mr. Bingley, a married and an unmarried sister, and the former’s husband, come to reside on an estate near the Bennets, and Mr. Darcy comes with them; he is Mr. Bingley’s great friend, and Miss Bingley has formed the intention of becoming his wife.

The Bingleys and Bennets meet at a ball, where Bingley falls in love at first sight with Jane Bennet, while Darcy is much bored by the whole thing, and, being urged to dance with Elizabeth Bennet, answers hastily and coldly that “she is not handsome enough to tempt me, and I am in no humour to give consequence to young ladies who are slighted by other men.”

Elizabeth overhears him, and registers a vow of eternal dislike to him. From this time, though neither the gentleman nor the lady have any wish to meet again, circumstances, which neither of them can control, force them into an intimacy.

. . . . . . . . .

Film and Mini-Series Adaptations of Pride and Prejudice

. . . . . . . . . .

In due course, Darcy, who has begun by despising Elizabeth as a mere country-town belle, and believes himself perfectly safe from her attacks, falls hopelessly in love with her, although she has no idea of it.

When at last he is impelled to throw himself at her feet, she rejects him indignantly, not only, it should be said, on account of the original insult, but also because she believes him to have acted treacherously and basely in some occurrences of his past life.

She has, however, been deceived, in the stories she has heard, which her original dislike to him made her accept too readily, and Darcy, feeling bound to clear himself, writes her an explanation which opens her eyes to see that she has cruelly misjudged and needlessly insulted him.

Upon a generous nature like Elizabeth’s this knowledge can have but one result—she is gradually drawn over, first to admire, then to esteem him, and so reaches the brink of love, though he has no suspicion of her change of feeling and is determined never again to try his fate.

Circumstances, which seem likely to separate him and Elizabeth forever, prove to be the chain which draws them together at last.

Lydia’s disreputable elopement

Lydia, the youngest of the five Bennet sisters, a foolish, spoilt, flirting girl, makes a disreputable elopement with a young officer, named Wickham, of whom Elizabeth had seen a good deal.

He is the son of a former steward of Mr. Darcy, handsome, plausible, and unprincipled, and, having been thwarted by his employer in a disgraceful attempt to take Holy Orders, had revenged himself first by attempting an elopement with Miss Darcy, a girl of fifteen, to whom her brother is guardian, and afterwards by spreading abroad scandalous stories of Darcy, all absolutely false, although concocted with skill.

Elizabeth, at the time when her feelings against Mr. Darcy were most hostile, had heard and believed these stories, and it is to these she made an allusion when rejecting him. To clear himself he is obliged to tell her of his sister’s narrow escape, which, he entreats, she will tell no one but her sister Jane, and she obeys the injunction.

Now, in the first agony at Lydia’s shameful elopement, she reproaches herself bitterly for not having warned her own family against Wickham.

. . . . . . . . . .

Why Has Mr. Darcy Been Attractive to Generations of Women?

. . . . . . . . . . .

Darcy, generously taking the blame upon himself, sets off in pursuit of the fugitives, whom he traces, and reinstates in comparative comfort and decency, after spending much time, trouble, and money in the undertaking, and (having done all this without the knowledge of the Bennet family) only requires that none of them shall ever be made acquainted with all that they owe him.

Of course, the secret leaks out, and Elizabeth is overwhelmed by the magnanimity of the man she has disliked and insulted, so that when be again ventures to plead his cause she grants it. She is all the more willing to do so as Jane is on the eve of a happy marriage with Bingley, and one of her bitterest prejudices against Darcy had been engendered by his opposition to their engagement.

Everything is now rose-color, but, unfortunately, Elizabeth had been at first so very outspoken against Mr. Darcy, and afterwards (partly from necessity) so very reticent about his rise in her good opinion that none of her relations, except an uncle and aunt, who have lately seen them together, can believe in her changed feelings, and even her own beloved sister is hard to convince.

Elizabeth, by repeated assurances that Mr. Darcy was really the object of her choice, by explaining the gradual change which her estimation of him had undergone, relating her absolute certainty that his affection was not the work of a day, but had stood the test of many months’ suspense, and enumerating with energy all his good qualities, she did conquer her father’s incredulity, and reconcile him to the match.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Memorable Quotes from Pride and Prejudice

. . . . . . . . . .

In following the career of the hero and heroine, the secondary characters of Pride and Prejudice have been somewhat passed over, but there is not one that could be suppressed without injury to the book, and each and all are excellent in their way.

Take, for instance, Mr. Collins, the prim, self-satisfied, under-bred young clergyman. He is cousin to Mr. Bennet, and (to Mrs. Bennet’s never-ending wrath) heir to the Longbourn estate.

Mr. Collins, being in search of a wife, hopes to find one among his cousins, and, for that purpose, invites himself to stay with them. He is kindly received, and after dinner the conversation turns upon his good fortune in having been presented to his living by Lady Catherine de Bourgh.

We feel, after a certain dialogue, that we know something of Lady Catherine as well as of Mr. Collins, and our acquaintance with both is allowed to increase. Mr. Collins fixes his intentions on Elizabeth, who, of course, refuses him; but she has an intimate friend, Charlotte Lucas, whose ideas about marriage are by no means as lofty as her own, and who is quite willing to accept a comfortable house and good income with Mr. Collins attached.

She becomes Mrs. Collins, and Elizabeth, though shocked and grieved at the marriage, cannot refuse her friend’s earnest entreaty to pay her a visit in her new home.

Darcy tries again

During this visit she unexpectedly meets Mr. Darcy, who is Lady Catherine’s nephew, and receives the offer from him, which she refuses with such indignant surprise.

She has traveled with Sir William and Maria Lucas—Charlotte’s father and sister—and two days after their arrival the whole party are invited to dine with Lady Catherine, Darcy and his friend not having then arrived.

There could not be a better picture of a second-rate great lady’s behavior towards people whom she considers as her inferiors, and it may be supposed from this how angry she is when her cherished nephew, whom she also intended should be her son-in-law, falls in love with Elizabeth.

She hears of it from outside sources, at about the time of Jane’s engagement to Bingley, and at once sets off for Longbourn to load Elizabeth with reproaches, and insist upon her giving up all idea of marrying Darcy.

Of course, Elizabeth absolutely refuses to do this, and her ladyship departs in great wrath; but as she has wrung from Elizabeth an admission that she is not actually engaged to Darcy, she calls on him in the hopes that he may be deterred from proposing again.

Her anger has, however, just the contrary effect; her account of what she calls Elizabeth’s “perverseness and assurance” fills him with hope, and urges him on to the final proposal, in which he is successful.

“It taught me to hope,” said he, “as I had scarcely ever allowed myself to hope before. I knew enough of your disposition to be certain that had you been absolutely, irrevocably decided against me, you would have acknowledged it to Lady Catherine, frankly and openly.”

As Elizabeth observes, “Lady Catherine has been of infinite use, which ought to make her happy, for she loves to be of use,” and though her ladyship’s fury knows no bounds when she hears that Darcy is actually married to Elizabeth, she condescends in time to make overtures to them, which they care too little about her to refuse.

Elizabeth Bennet charms throughout

Elizabeth Bennet’s charm is one that pervades the book, and is not easily condensed into any isolated passage; but her first connected conversation with Mr. Darcy after their engagement is fairly characteristic of both of them.

Elizabeth’s spirits soon rising to playfulness again, she wanted Mr. Darcy to account for his having ever fallen in love with her.

“How could you begin?” said she. “I can comprehend your going on charmingly when you had once made a beginning; but what could set you off in the first place?

“I cannot fix on the hour, or the spot, or the look, or the words, which laid the foundation. It is too long ago. I was in the middle before I knew that I had begun.”

“My beauty you had early withstood, and as for my manners—my behaviour to you was at least always bordering on the uncivil, and I never spoke to you without rather wishing to give you pain than not. Now, be sincere; did you admire me for my impertinence?”

“For the liveliness of your mind, I did.”

Darcy is quite as well-drawn a character as Elizabeth, for though his pride and self-will are, in the early part of the story, almost overpowering, we always see the really fine nature behind them, and we can feel that when he meets with a woman who will respect him, but never stoop to flatter his faults, and whom he can love enough to bear with her laughing at him, he will be a most devoted and excellent husband.

. . . . . . . . .

Pride and Prejudice on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

If the book can be said to have any defects, they are—first, that it is impossible to see how such a woman as Mrs. Bennet could have two daughters like Jane and Elizabeth; secondly, at Lydia’s elopement is a disagreeable incident, told too much in detail, and made needlessly prominent.

It is intended to bring Wickham’s baseness into greater relief, and to show how Darcy’s love could even triumph over such a connection; but it is revolting to depict a girl of sixteen so utterly lost to all sense of decency as Lydia is, and the plot would have worked out quite well without it.

Still, at the time Jane Austen wrote, she might have pointed to many episodes in great writers that were far more strangely chosen, and Lydia’s story does not really occupy much of the book, thought, for a time, it is prominent.

The other flaw is, I venture to think, the mistake of a young writer, and Mrs. Bennet is so excellently drawn, and is so amusing, that we cannot wish her refined into anything different.

It may be said, also, that Lady Catherine is too vulgar for a woman who was really of high birth; but it must be remembered that she is introduced among people whom she considers her inferiors, and vulgarity in high life is not so rare but that even Jane Austen, in her quiet country home, may have come across it.

There is not a character nor a conversation in Pride and Prejudice that could be omitted without loss, and we may, therefore, very well give over criticizing small defects, and yield ourselves to the full enjoyment of its genius as a whole.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post A 19th-Century Analysis & Plot Summary of Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 10, 2022

Writing for Madame: The Complex Friendship of Violette Leduc and Simone de Beauvoir

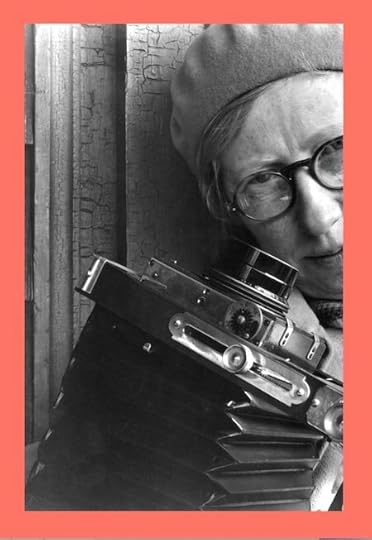

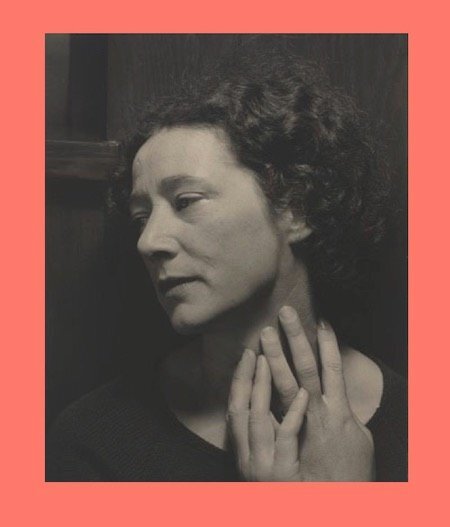

Simone de Beauvoir first met the French author Violette Leduc in 1945. At the time, de Beauvoir and her partner, Jean-Paul Sartre were the golden couple of Parisian intellectual circles, while Violette Leduc was a struggling writer mired in poverty.

Their first meeting, in the heady atmosphere of the Café Flore on the Left Bank, came only after Leduc had observed de Beauvoir and Sartre from a distance for several months, gathering the courage to introduce herself.

The resulting friendship seemed unlikely. Yet it lasted for several years, with mutual respect and admiration that survived Leduc’s unrequited attraction to de Beauvoir as well as the differing circumstances of the two women and their wildly diverging experiences of success.

Even today, Simone de Beauvoir remains a feminist icon while Leduc herself is marginalized, little known to either French or English readers, and their rich, complex friendship is often reduced to that of mentor and protege.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

An unlikely friendshipTheir backgrounds could not have been more different. Leduc spent her childhood in poverty, as the unwanted daughter of an affair between a servant and the son of a wealthy family. Her education was piecemeal. She was expelled from her boarding school for having an affair with her female music teacher, Denise Hertgès, and she ultimately failed her baccalaureate exam.

Along with Denise (who she lived with until their relationship ended in 1935), she moved to Paris and began working as a secretary for a publishing company. In 1939, she married an old friend, Jacques Mercier, but the marriage only lasted a year and resulted in an abortion that almost killed her. Poor and alone, nursing an unrequited obsession for her friend Maurice Sachs, she attempted to make a living during the war by selling on the black market.

In contrast, de Beauvoir was raised in a bourgeois Parisian family and grew up in the prestigious 6th arrondissement not far from where she would eventually meet Leduc. Despite the family’s fortunes that had suffered during World War I, she attended a prestigious convent boarding school and passed her baccalaureate exams in both math and philosophy in 1925.

She then studied philosophy at the Sorbonne before achieving second place in the agrégation in philosophy, a competitive national postgraduate exam (Jean-Paul Sartre came first). She taught at lycée (high school) level until 1943 when she started making a living from her writing.

Despite their circumstances, the two women found common ground through writing. De Beauvoir later said that her first impression of Leduc was of a “tall, elegant blonde woman with a face both brutally ugly and radiantly alive.” But her attention was truly drawn to the manuscript Leduc handed her, titled “Confessions of a Woman of the World.”

De Beauvoir was skeptical. But instead of the “socialite’s confessions” she had been expecting, it was an extraordinary memoir of childhood that enthralled her so much that she read the first half of it without stopping. Determined that it should be published, she arranged for excerpts to appear in Les Temps Modernes, the journal that she had launched with Sartre, and was instrumental in its eventual acceptance by Gallimard in 1946. It was published as L’Asphyxie (later translated as In the Prison of Her Skin and again as Asphyxia).

It was the start of what would become a complex relationship, in which de Beauvoir became not only Leduc’s lifelong mentor and champion of her work, but also her muse and the subject of her unrequited attraction.

The starving woman

From then on, the two met every other week to discuss Leduc’s work. When de Beauvoir was abroad, she would send letters, but whether in person or in writing, she would always ask Leduc the same question: “Have you been working?” Already realizing that Leduc was prone to fits of paralyzing insecurity and feelings of unworthiness, de Beauvoir was determined to keep her new protege writing.

De Beauvoir’s support also extended to the financial: quickly understanding that Leduc’s poverty was a major obstacle to creativity, she arranged a small monthly stipend, claiming that it was paid by Gallimard.

Leduc became infatuated with de Beauvoir and channeled her obsession into a new novel, L’affamée (later translated as The Starving Woman). The novel’s primary theme is hunger and Leduc’s preoccupation with what the narrator calls “the identical mirages of presence and absence.” It begins with the narrator’s encounter, in a café, with a person she calls Madame and goes on to recount the narrator’s fluctuating state of mind as the relationship with Madame evolves.

Alternately close to and distant from Madame, thrown into despair or ecstasy by one meeting after another, the narrator eventually comes to a tentative acceptance of the reality and limitations of the relationship.

The novel also incorporates De Beauvoir’s insistence that Leduc should write: the narrator, conscious of her own perceived shortcomings, seeks out anything that would make her worthy in the eyes of Madame. “Let her order me to remove my shoes, let her order me to run on rocks, on nails, on pieces of broken glass, on thorns.” But what Madame demands instead is the “purgation” of creativity, and in particular of writing.

De Beauvoir described the novel to her American lover Nelson Algren as “a diary in which she tells everything about her love for me. It is a wonderful book.” However, she rejected Leduc’s advances, writing in 1945:

“Despite my colossal indifference, I was very moved by your letter and your journal. You tell me about my loyalty, I admire yours. I believe thanks to our mutual esteem and trust, we will achieve a balance in our relations. It is strange to find out that you are so precious to someone: you know that you are never precious to yourself; there is a mirage effect which will certainly dissipate quickly. In any case, this feeling cannot bother me more than flatter me … I would like you not to be afraid of me anymore, that you get rid of all this fearful side which seems to me so unjustified. I respect you too much for this kind of mistrust, of apprehension, to have any reason to exist.”

Leduc wrote of her devastation, saying, “She has explained that the feeling I have for her is a mirage. I don’t agree.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Simone de Beauvoir

. . . . . . . . . .

Far from ending their friendship, however, Leduc’s infatuation only seemed to make it stronger, and De Beauvoir continued to act as a guide and mentor. The two continued to meet every other week, and whenever de Beauvoir was abroad, she sent encouraging and supportive letters to Leduc. From the Sahara, in 1950, she wrote:

“I am wholeheartedly with you in the struggle which you are leading to courageously to write, to live; I admire your energy, I would like this sincere deep esteem to help you a little.”

When Leduc’s novel Ravages had its entire first section censored as obscene for its depiction of a lesbian affair between two schoolgirls, de Beauvoir was “indignant at their prudery, their lack of courage. Sartre too. Do not be broken. You must defend yourself and we will help you…”

The censored novel was eventually published in 1955, while part of the offending section was later published as a stand-alone novella, Thérèse and Isabelle. It was a commercial success, and a film adaptation was released in 1968. But even this was not published in its entirety in France until 2000, and it didn’t appear in English translation until 2012.

Paranoia, depression, and psychiatric treatment

Despite De Beauvoir’s support, Leduc still struggled to achieve the recognition that she wanted and felt she deserved. Her first two books had been well received by other authors such as Jean Cocteau, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Jean Genet, who said of Leduc, “She is an extraordinary woman … crazy, ugly, cheap, and poor, but she has a lot of talent.”

The critics, though, were not impressed, and Leduc was mostly ignored by the reading public. Despondent and frustrated, she once said, “I don’t think of myself as not understood. I think of myself as nonexistent.”

By 1956, Leduc was suicidal and paranoid. Depressed by poor book sales and plagued by migraines and insomnia, she became convinced that journalists and critics were ridiculing both her creative failures and what she perceived as her ugliness. In desperation, she asked de Beauvoir to help her arrange an “investigation” into this press harassment.

Alarmed, de Beauvoir persuaded her to go to a psychiatric clinic at Versailles. She remained there for six months, her bills paid by de Beauvoir, undergoing electroconvulsive therapy and a “sleep cure.”

Belated success

Over the next few years, Leduc published two more books, neither of which met with much success. Her health remained fragile, and she began to lose faith in writing. It was de Beauvoir, committed to her belief in Leduc’s talent, who encouraged her to write her life story. The result was La Bâtarde, published in 1964 with a glowing preface by de Beauvoir:

“A woman is descending into the most secret part of herself, and telling us about all she finds there with an unflinching sincerity, as though there were no one listening.”

With this book, Leduc finally achieved some of the success she had craved for so long: it sold 170,000 copies in just a few months and was nominated for both the Prix Goncourt and the Prix Femina.

“The most interesting woman I know”

It wasn’t entirely a one-sided relationship. De Beauvoir considered Leduc “the most interesting woman I know” and was intellectually inspired by the woman who seemed to encapsulate and embody so many of her philosophical theories. She cited Leduc frequently in The Second Sex and drew on Leduc’s life for the book’s analysis of lesbianism.

In Leduc, she saw a vindication of her own philosophy — that we are all free to choose, no matter our past or previous circumstances. To her, Leduc had overcome the limitations of her childhood by choosing to write, thus freeing herself from the constraints of what life had laid down for her. Leduc, incidentally, challenged this theory, saying that “To write is to liberate oneself. Untrue. To write is to change nothing.”

The friendship between the two women lasted until Leduc’s death in 1972 from breast cancer, but it always defied any kind of neat classification. Despite their closeness, de Beauvoir stated in the 1980s that, “I established a certain distance from the very beginning,” while Leduc admitted in her memoirs:

“I shall never understand the meaning of the word love when it applies to her and to me. I do not love her as a mother, I do not love her as a sister, I do not love her as a friend, I do not love her as an enemy, I do not love her as someone absent, I do not love her as someone always close to me. I have never had, nor will I ever have, one second of intimacy with her. If I could no longer see her every other week, darkness would submerge me. She is my reason for living, without having ever made room for me in her life.”

. . . . . . . . .

Violette

(2013 film) is available to stream on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

The complexity and ambiguity surrounding their relationship have proven to be a source of continued fascination: the 2013 film Violette, starring Emmanuelle Devos and directed by Martin Provost, concentrated largely on Leduc and de Beauvoir, and was well received.

And in 2020, when de Beauvoir’s letters to Leduc were sold, auction house Sotheby’s described them as “remarkable … charting a complex and ambiguous relationship…where unrequited amorous passion, tenderness, and mutual admiration tinged with mistrust mingle.”

Perhaps, though, it is best summed up by one of Leduc’s last interviews, given in 1970, in which she poignantly acknowledged, “at the end of my life I will think of my mother, I will think of Simone de Beauvoir, and I will think of my long struggle.”

. . . . . . . . .

Violette Leduc page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is an author, poet, and artist with a serious case of wanderlust. She is originally from the UK, but has spent time abroad in Europe, the United States, and the Bahamas.

When not traveling or working on her current projects — a chapbook of poetry, “The Cabinet of Lost Things,” and a novel based on the life of modernist writer and illustrator Djuna Barnes — she can be found with her nose in a book, daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Visit her on the web at Elodie Rose Barnes.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Writing for Madame: The Complex Friendship of Violette Leduc and Simone de Beauvoir appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 8, 2022

Evvie by Vera Caspary (1960)

Evvie (1960) is a sophisticated thriller by the remarkably prolific and unfairly forgotten novelist and screenwriter Vera Caspary. This appreciation and analysis of Evvie is excerpted from A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth ©2022. Reprinted by permission.

The publisher’s copy described the novel succinctly:

“This big, bursting novel of the roaring Twenties – and of two girls who believed that love and art could save the world, if not themselves – is in our view the best book that Vera Caspary has ever written, not forgetting Laura.

Evvie Ashton and Louise Goodman shared a studio in Chicago in 1928, the age of “the girl.” Louise was a successful advertising copywriter in love with her boss. Evvie, married and divorced at seventeen, beautiful, artistic, was living on her “alimony”. Men found her irresistible – just as she found men. She painted, she danced, she read a great deal, and could discuss anything by repeating what her admirers had said.

But, in the midst of all the gaiety, Evvie and Louise found their lives becoming desperately complicated. Yet neither sensed that tragedy was to strike, until a horrible crime involving friends and families, strays and unknowns, the cream and the dregs of Chicago, gave the newspapers a field day.

The reader, mesmerized by the constantly mounting suspense, follows the involvements, the revelations and the shocking relationships of all those touched by the crime. But it is Evvie herself who will haunt the reader’s memory for a long, long time.”

Reviews of this novel were overwhelmingly positive, highlighting the author’s talent at weaving suspense into a compelling narrative of the lives of two freedom-loving young women in the Roaring Twenties. Here’s a snippet of one such typical review:

“That same Vera Caspary who wrote the exciting Laura some years ago has a new murder-suspense story, Evvie, which in addition to skillful suspense provides a detailed account of two free and easy successful business gals in the Chicago of the Twenties. Evvie is so attractive and the evocation of her period so nostalgic that the reader is tempted to forget what a good mystery the author makes of who killed Evvie.” (Rocky Mountain Evening Telegram, September 18, 1960)

Focused on “faint praise”

Yet despite numerous glowing reviews, Caspary chose to focus on the “faint praise,” as she puts it, in this passage from her memoir, The Secrets of Grown-Ups (1979):

“The novel Evvie, which I still think one of my best, was greeted with faint praise. In Chicago, Fanny Butcher came out of retirement to declare it obscene—ironic judgment from today’s point of view, since there are no graphic descriptions, and the most explicit allusions are in a scene in which two naked girls discuss sex.

Since Laura I’ve been typecast as a suspense writer and, to my own dismay, may have fallen into the trap. Evvie was born of a situation involving murder. But instead of keeping to the mystery formula I indulged in elements far out of that field of fiction. There was only one murder. It came late, halfway through the story.

Evvie is a picture of the lives of girls in the twenties, drawn quite honestly from my own experiences. More clearly than in any of my other books it defines the changing position of women at a time when tradition was sturdier, inhibition more binding than in these later years when girls declare independence by demanding entrance to men’s colleges, sports, and bars. Evvie was begun in London, continued in New York, finished in Beverly Hills, proofed in Paris.”

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Vera Caspary

. . . . . . . . .

Caspary’s characterization of Fanny Butcher’s review is rather unfair; perhaps she misremembered it: the review is not exactly glowing but Butcher had been reviewing books for nearly 40 years at this time and can perhaps be forgiven for her cynicism regarding books written to be popular.

Butcher was hardly anti-Caspary: her review of The White Girl thirty years earlier had been very positive. And, despite Butcher’s reservations, her review does make one want to read the novel ,though apparently it did not make enough people want to read it to make Evvie a bestseller. Butcher doesn’t call the novel obscene at all and she had not in fact retired at this time. The review in question, from the Chicago Tribune, August 7, 1960, titled “Setting: Chicago 1920; Flavor: Beatnik 1960” concludes:

“Nobody is going to be deterred from reading Evvie for technical reasons, however, nor, in these days of the policy of the open door to every bedroom, by the heroine’s inability to deny herself a man, any man, even her best friend’s beloved. And Louise’s way of telling the story has a kind of entrancing glitter. So Evvie will probably be on the bestseller lists and be bought for the movies before the author gets her first royalty check.”

One of Caspary’s best novels

With hindsight, Caspary was right about Evvie: it is one of her best novels, possibly the best of them all and deserves to be as well-known as Laura and Bedelia. But, despite Butcher’s predictions, it never was on the bestseller lists, never was bought for the movies and is almost forgotten today.

It is a particular shame that it was never made into a film; the fact that the murder occurs and the heroine disappears halfway through would have been no barrier: Hitchcock did exactly that in Psycho, also released in 1960. And the year after Evvie, 1961, Caspary’s next novel, Bachelor in Paradise, was made into a film.

Perhaps by that time, after the death of film noir, producers were looking for more frothy material – Caspary could certainly do frothy; she did so with Out of the Blue in 1947, again with Bachelor, and in her light, romantic screenplays and original treatments for the movies. But not with Evvie. Evvie was serious for her — serious and personal, perhaps even cathartic in its intensely personal autobiographical elements.

A complex and autobiographical novel

Evvie is a complex novel and in my categorization of Caspary’s works into psycho-thrillers and coming of age novels it could have counted as either: its first sentence is “Horror attended the death of girlhood.”

The narrator, Louise, despite her high-earning job and the respect she gets from men in the office, is reluctant to leave girlhood behind and come of age. “With the responsibilities of my job, the help I gave my mother, with life insurance and the right to vote for a president in November, I was adult, old enough to give up girlhood. But how? I loved being a girl, I did not want to change. Maturity looked too stolid.”

Along with the earlier Thelma, Evvie is unique among Caspary’s works in that it has a first-person narration where the narrator is not the title character, like Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. This trope is also reminiscent of Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone – we have already seen how heavily influenced Caspary was by Collins’ other novels – where Rachel Verinder is the central character but never the narrator; like Collins’ Rachel and like her namesake in du Maurier’s My Cousin Rachel, Evvie is only seen through the eyes of other people.

Evvie is also unusual in being by far by far the most autobiographical of Caspary’s works, apart from her actual autobiography – the narrator is called Louise, Caspary’s middle name, in case we had any doubts. Louise is not so much a Caspary woman as a lightly fictionalized version of Caspary herself.

In fact, we might almost say that the title of the novel is a red herring: it really should have been called Louise; Evvie herself is almost as absent a presence as Rebecca in du Maurier’s eponymous novel.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie on Amazon (US)*

and *

. . . . . . . . . .

Although Evvie was published in 1960, when Caspary was sixty-one years old, the setting is a lovingly described late 1920s Chicago, as it was in the much earlier The White Girl and Music in the Street and would be again much later in The Dreamers. At this time and place Caspary was working in a man’s world as a copywriter and designing and selling correspondence courses while writing a novel in her spare time, as is Louise.

But, like Caspary herself, Louise Goodman is regarded as one of the boys (a good man). “They put on a show of gallantry and when they used off-color expressions smiled toward me furtively. Someone would always remark that you could say anything in front of Louise, she was a hell of a good sport.”

At work, because they are not obsessed with Louise’s looks, not scared of her, men feel able to give Louise backhanded compliments: “I’ve never known a girl like you. You’re not pretty but you got a wonderful line and you’re dynamite.” Evvie, who has no job and lives off the alimony her stepfather gets, is a painter – the two girls live in her studio apartment – and the pretty one of the pair; next to her Louise is the plain but smart one.

All the sections of Evvie that describe Louise’s job sound like the reminiscences of Caspary herself, as told in her tales of those 1920s days in her autobiography The Secrets of Grown-ups. Louise’s mother even sounds very much like Caspary’s in her attitude to her daughter’s business career and independence:

“For the life of her Mama could not see how anyone could pay eighty dollars a week to a girl of twenty-two. Yet she was proud. These shreds of information nourished her and my success at the office gave her the chance to brag when ladies at bridge tables wondered why a girl clever enough to earn all that money had not yet found a husband.”

Like Vera Caspary with her Marinoff dance course and Van Vliet photoplay course, Louise Goodman writes correspondence courses for the agency, inventing gurus for whose advice subscribers will pay good money, like the famous Dr. Russell Wadsworth Bryant. But “there was no Dr. Russell Wadsworth Bryant. The names of three New England poets had been strung together to give the sound of culture to E. G. Hamper’s correspondence course. . . My greatest success in the agency had been in the development of the Bryant personality.”

The emergence of the working girl

It is not just in Louise’s job but in her relationship with Carl, one of her bosses in the office, that she is so similar to Caspary, who in her autobiography describes in detail the physically intimate relationship with her own boss, whom she calls simply the Junior Partner.

Louise begins to fall for Carl just as he begins to withdraw; she doesn’t understand the change in his attitude to her until later.

“Each day at the office I waited for some sign of change in Carl’s attitude, some word of praise, some little attention. . . I was tempted to ask if and why he had quit liking me but had no courage to face him with the question. I pitied myself, so a spinster future and the dry life of devotion to my mother.”

Like Caspary herself in the late 1920s, Louise uses every spare minute of her leisure time to write novels and stories. When the Chicago winter is so bad she can’t get to work, Louise only has one thing on her mind: “Wearing two sweaters, a robe and blankets I tried to work on my novel. It was impossible to travel through the snow-piled streets to the office.” This reads like Caspary fondly reminiscing. Even Louise’s description of her literary ethos could be a summary of Caspary’s own positioning of women within her fiction:

“All my tales, whether gaily caparisoned with wealth or morbid in poverty, whether celebrating health or pain (for there are sanatoria and cemeteries as well as ballrooms), tell of man’s reliance upon woman, his need, blindness, and final recognition. In its many beginnings, mutations and styles of narration, my story always concerns man’s search for the sympathy and satisfaction that only the heroine can bestow.”

Both the time around and just after Evvie’s publication in 1960 and the time of its setting in the 1920s were in their different ways the era of the working girl: independent, sexually aware and enjoying her freedom – though the working girls of the 1960s enjoyed sexual freedom far more than those of the 1920s.

The first wave of novels about these freedom-loving, happily unmarried working women started appearing in the 1920s. A second wave started appearing at the end of the 1950s with Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything in 1958, followed by Evvie in 1960 and then Mary McCarthy’s The Group and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, both published in 1963. A passage from Evvie:

“For this was the age of The Girl. We had come out of the back parlor, out of the kitchen and nursery, we turned our backs upon the blackboards, shed aprons and paper cuffs. A war had freed us and given women a new kind of self-respect. The adjective poor no longer preceded the once disreputable working girl. It was honorable, it was jolly, it was even superior to be a career girl. Intellectual young men considered themselves members of a lost generation. For us it was a decade of self-discovery. We held jobs, we voted, we asserted equal independence with men, equal privilege. Best and most decisive in the reshaping of our lives was the money in our pocketbooks.”

The female contraceptive pill was launched in the United States in 1960, and although it wasn’t widely available for a long time, that didn’t stop women claiming sexual equality with men or refusing to wait until after marriage to have sex. It certainly doesn’t stop Evvie and Louise, who have 1960s rather than 1920s sex lives.

Even Evvie’s wealthy and flighty mother does not disapprove. “If you’re not married or engaged, the least you can do is have a bit of fun. But I insist that you use proper contraceptives. Do you know about pessaries? … We could go to London and have you fitted.”

In The Group, Dick tells Dottie to get herself “a pessary;” she doesn’t understand. “‘A female contraceptive, a plug,’ Dick threw out impatiently. ‘You get it from a lady doctor.’” Dick is married – to someone else – and makes Dottie promise not to fall in love with him; no one in “the group” wants naïvely to confuse sex and love. Neither does Louise in Evvie.

“To this day I am grateful that I had my first experience with an honest lover. There were no romantic promises, no vows of permanent devotion, no discussions of marriage. Our generation took lovers with conviction and did not rush off to seek absolution. Nor was I a girl who considered a husband destiny and a wedding the end of all seeking.”

Nevertheless, much later, when the first lover tells Louise he is getting married, she has pangs of regret. “In the mirror I saw the pallid, tear-streaked face of a spinster with no more in life than a job and the memory of a youthful affair.”

Frank, cynical, and explicit

In its frankness, cynicism and explicitness about sex, Evvie feels as though it was written sometime in the middle 1960s, in the time of Betty Friedan and Helen Gurley Brown, in the age of the contraceptive pill, rather than at the end of the 1950s.

But according to Caspary’s autobiography, there was indeed a similar frankness about sex in the big city when she moved to New York in the 1920s, when she was in her twenties; Caspary seems herself at that time to have lived a life very similar to that of Louise and Evvie, according to The Secrets of Grown-Ups:

“Sex was the backbone of conversation among intellectuals and their imitators. In uptown apartments as well as Greenwich Village studios, among girls and girls, men and men, men and girls, with lovers, potential lovers and rejected lovers; conversation was the popular aphrodisiac.

We all had a smattering of kindergarten Freud and at the drop of a chemise would analyze our own and our friends’ affairs. Sexual inhibition was to be avoided like pregnancy and a repressed libido shunned like a dose of clap. No one used the term sexual revolution, but certainly a generation had risen in revolt against the Victorian restraints of its parents. Sex had become the dominating theme of novels, plays, sermons, lectures, jokes, and pranks.”

Evvie was married and divorced young, so she isn’t a virgin at the start of the story. But she doesn’t at first let her latest lover – the mystery lover with whom she is obsessed but whose name Louise and we, the reader do not yet know – know about her sexual appetites.

Later Evvie feels she has to confess to him about her urges and then she confess her confession to Louise, who is Evvie’s confidante in everything but the man’s name: “wayward and wanton,” is how she describes herself to him, stealing the words from Louise’s novel, though she denies being obsessed with sex.

“’I said I’d never liked it very much, that I really didn’t care an awful lot about sex. That’s true.’ Sighing again, she waved her cigarette aloft. ‘I never did go crazy about it the way some girls do. At boarding school in Santa Barbara there were girls, simply maniacs.’”

For contrast, Caspary gives the sexually aware Louise and Evvie a mutual friend, Midge, a relatively new recruit to the ranks of Chicago working girls who is shy and virginal, very much unlike them. Midge has a boyfriend who keeps insisting she has sex with him, but Midge is very unsure. “I’ve told him over and over, let’s be good friends, Bob, but don’t ask me to be a common pushover.”

Louise and Evvie try to explain that his attitude is perfectly normal in a young man. “Bob’s in love with you and he honestly believes that sexual completion is an expression of love.” Midge will not relent. They accuse her of cruelty to Bob.

After Evvie’s death, Midge, now a successful newspaper reporter, wastes no opportunities to hit out at the immorality of Evvie and her circle in her paper.

“Last winter Evvie and her sophisticated friends laughed at this country girl for expressing horror at their advanced views of life and sex but today these same ‘bright young people’ are asking themselves what all of their cocktails, jazz, modern philosophy and indiscriminate petting leads to.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Physical copies of Evvie are very hard to come by;

here’s the Kindle version on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Up to this point, Evvie has been simply a more-than-semi-autobiographical story about two young women enjoying free life and free love in the 1920s. Suddenly, mid-chapter, it becomes a psycho-thriller. Both of the big revelations come at once, though Louise and the reader have already begun to suspect the first revelation: “Only the compulsion to self-deceit could have kept me from noting the signs along that tragic road.”

In the very next paragraph, the M word first appears for the first time as the pace and tone of the story change completely.

“To keep this story rigidly within the limits of my knowledge at that time would stunt its growth. Indirection and subterfuge weave a false mystery. What I shall now tell (out of chronological order) was later confessed in a darkened room. The terror of its mood is recalled whenever I see bars of unwelcome sunlight force their way through a closed Venetian blind or hear in any voice the echo of desperation. It was in the taut time after the murder when Carl sought my understanding. No other state of mind could have brought about such articulate agony.”

As Caspary later said in her autobiography, quoted above, she had begun writing Evvie as a mystery, but she had “indulged in elements far out of that field of fiction” – she had clearly got carried away with the thinly-veiled autobiography and ended up combining two kinds of narrative in one novel, which upset some critics and readers.

Still, that blending of mystery and psychology is the essence of the psycho-thriller and when we learn that Evvie has been murdered, we care far more about her than we did about Laura because we know so much more about her. At this stage, we have no idea how or why Evvie was killed; this is the opposite of Laura, where we know exactly how the murder was committed but very little about the murdered woman.

The rest of the novel alternates between psycho and thriller, though there is far more reflection than action, with revelations, flashbacks of details from Louise’s past and Evvie’s diary, which Louise finds in the studio and hides from the police – she had not read it before.

“Betrayal by a man is to be expected, woman’s lot, but she had been my friend, my darling, beloved since childhood. As I walked I scolded her. Resentment was barren for it is futile to rage at the dead; but I had to remind her. There was so much, thousands of secrets, confidences, foolish notions. She had been my first love. I had been caught in that period when a girl gives rapture and worship to her own sex.”

Louise – as Caspary’s mouthpiece – makes clear again that the story, like any narrative, must be unreliable and partial.

“Out of yellowing newspapers as vulgar and lively as this morning’s murder, out of Evvie’s diary and mine this story has been rewoven; out of nostalgia for girlhood, out of snatches of unforgotten conversations, daydreams disinterred, out of tunes and flavors that recall ghosts. I cannot promise that every scene is precisely remembered nor every dialogue true.”

Spoiler ahead

Carl is arrested for Evvie’s murder, though neither he nor Louise have told the police about his relationship with the dead Evvie. But it turns out that Carl didn’t do it, someone else did, someone unlikely, someone we have not even met before: the “pimply” boy who worked at the garage next to the studio and had run errands for Evvie; he had become obsessed with her.

But although this twist is unexpected and unlikely, not to mention disappointing, Caspary has planted plenty of examples of Evvie giving money to disabled beggars and the unfortunate who lined the streets of Chicago in the manner of Chekhov’s gun. Louise had always been frustrated at Evvie’s indulgent and, as Louise sees it, dangerous habit of talking and giving to waifs and strays, the disabled and the outsiders, of whom the young murderer is one.

This unexpected and unconventional ending is either, according to taste, brilliant or banal and bathetic.

“There was no mystery nor moral to the squalid tale; it had none of the inexorable directness of a contrived detective story, neither the glitter of crime in high places nor the spice of Bohemian transgression.”

As she had in Laura, Caspary comments, meta-fictionally, on the traditional detective story and connects the psycho with the thriller.

“The horror of the case lay in its untruths; all those bright red herrings hailed in the beginning as important clues and found in the end to be no more than reflections of our own guilt.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Evvie by Vera Caspary (1960) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 7, 2022

Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen: A 19th-Century View

Jane Austen by Sarah Fanny Malden (1889) is an excellent resource as a 19th-century view of Jane Austen’s works. The publication was part of an Eminent Women series published by W.H. Allen & Co., London. The following analysis and plot summary of Sense and Sensibility (1811) focuses this work, which was Jane Austen‘s first published novel.

Mrs. Malden said of her sources, “The writer wishes to express her obligations to Lord Brabourne and Mr. C. Austen Leigh for their kind permission to make use of the Memoir and Letters of their gifted relative, which have been her principal authorities for this work.” This excerpt is in the public domain:

In the summer of 1811, two years after Jane Austen’s move to Chawton Cottage, Sense and Sensibility was published by Egerton. Jane, at the age of thirty-six, was fairly launched on that career of authorship which was to prove so short, yet so much more brilliant ultimately than her best friends and warmest admirers could have expected.

Her own expectations were so humble—probably from previous disappointments — that it has been said she saved something out of her income to meet any possible loss in the publication, a precaution which was uncalled for. She made one hundred and fifty pounds by it, and, on receiving the money, remarked that it was a great deal to earn for so little trouble!

Sense and Sensibility was originally called Elinor and Marianne, but it might as appropriately have been named The Dashwood Family, for it is really the history of one family, of whom two sisters are nominally the chief characters, but by no means the most interesting; and the other personages of the story, as was so usual with Jane Austen, only revolve round the central characters.

John Dashwood’s promise

From the first conversation early in the book between John Dashwood and his wife, we feel that we know them thoroughly, and can safely predict their future conduct all through. John is the only child of his father’s first marriage; he inherits a good fortune from his mother, and has acquired another with his wife, besides which his only child has had a large one unexpectedly left to him by a relation.

He has a stepmother and three half-sisters, Elinor, Marianne, and Margaret Dashwood, who, on the premature death of the father, are left very scantily provided for. On his deathbed, Mr. Dashwood earnestly entreats John Dashwood to do something for them, which the latter readily promises, especially since the fortune that has come to his child had always been destined for the second family.

The John Dashwoods take possession of the house and estate as soon as the funeral is over, and the elder Mrs. Dashwood perceives that she and her daughters must soon find themselves a home elsewhere. Meanwhile John Dashwood debates, first with himself, then with his wife, as to what he is bound to do for them.

“When he gave his promise to his father he meditated within himself to increase the fortunes of his sisters by the present of a thousand pounds apiece. He then really thought himself equal to it. The prospect of four thousand a year in addition to his present income, besides the remaining half of his own mother’s fortune, warmed his heart, and made him feel capable of generosity.

“Yes, he would give them three thousand pounds: it would be liberal and handsome! It would be enough to make them completely easy. Three thousand pounds! he could spare so considerable a sum with little inconvenience.”

A wife’s objections

John Dashwood thought of it all day long and for many days successively, and he did not repent. His wife did not at all approve of what her husband intended to do for his sisters. To take three thousand pounds from the fortune of their dear little boy would be impoverishing him to the most dreadful degree. She begged him to think again upon the subject.

How could he answer it to himself to rob his child, and his only child too, of so large a sum? It was very well known that no affection was ever known to exist between the children of any man by different marriages, and why was he to ruin himself and their poor little Harry by giving away all his money to his half-sisters?

“It was my father’s last request to me,” replied her husband, “that I should assist his widow and daughters.”

Perhaps Mrs. Dashwood’s bitterness against her husband’s family is sharpened by perceiving the very evident attachment of her eldest brother, Edward Ferrars, for Elinor Dashwood, an attachment which both she and her mother find insupportable. They are bent on his making a brilliant marriage which shall raise him to eminence.

The elder Mrs. Dashwood, on the other hand, is delighted at the prospect, for, while cordially disliking her daughter-in-law, she has a great esteem and affection for Edward Ferrars; and warm-hearted, romantic, and imprudent, she looks to nothing but the future happiness of the young people.

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen

. . . . . . . . . .

The second daughter, Marianne, is the exact copy of her mother in disposition; both regard all prudence or circumspection as worldly wisdom of the worst type, and while they respect Elinor for her calm judgment and steady good sense, they have no wish whatever to imitate her.

I think the title of the book is misleading to modern ears. Sensibility in Jane Austen’s day meant warm, quick feeling, not exaggerated or over-keen, as it really does now; and the object of the book, in my belief, is not to contrast the sensibility of Marianne with the sense of Elinor, but to show how with equally warm tender feelings the one sister could control her sensibility by means of her sense when the other would not attempt it.

These qualities come still more prominently forward when Mrs. Dashwood and her daughters have found a home at Barton Cottage, on the estate of a cousin, Sir John Middleton. He is a good-humored sportsman, his wife a vapid fine lady, and his mother-in-law, Mrs. Jennings, a vulgar old woman. He is very fond of society, and the kind of society he gathers round him may be easily guessed.