Nava Atlas's Blog, page 25

June 29, 2022

How Mary Ann Evans Became George Eliot

In September 1856, the 36-year-old woman heretofore known as Mary Ann Evans (alternatively Marian) wrote in her journal that she had “made a new era” in her life, “for it was then I began to write fiction.”

It was a new era in another way, as well, because it was soon after this that Mary Ann Evans began to transform herself into the author we know as the eminent British novelist and essayist, George Eliot (1819 – 1880).

Mary Ann Evans was in the process of reinventing herself in several ways. A few months after she began writing fiction, she sent a letter to her beloved brother Isaac in which she announced, “You will be surprised to learn … that I have changed my name and have someone to take care of me in the world.”

She was not referring to her pen name when she announced this name change. In the same envelope with the note to Isaac was another to her sister Fanny, in which she spoke of her de facto husband, George Lewes.

Liberal-minded Lewes, a religious skeptic actively engaged in the scientific and philosophic debates of the day, had tolerated one instance of adultery on the part of his legal wife and having done so, had no legal grounds for divorce when his wife’s relationship with the other man continued, eventually resulting in four children whom Lewes adopted as his own.

Despite the legal impediments to her marriage, it was important to Eliot that she be known socially as Mrs. Lewes. A year or so later, Eliot urged a friend not to call her Miss Evans anymore. “My name is Marian Evans Lewes.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Silly Novels by Lady Novelists”

. . . . . . . . . .

As she began work on “The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton,” the first of the three novellas that would constitute Scenes of Clerical Life, she was very aware of her goals in writing fiction. Just a few days before beginning this new project, she had finished writing “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” an essay in which she denounced popular fiction with predictable plots and superficial heroines—well-educated, privileged women who failed to use their advantages to accomplish anything but to find a husband.

Perhaps it was fear of being dismissed as a “lady novelist” that led Eliot to hide her identity, or perhaps it was fear that her fiction would be rejected by publishers and readers because of her relationship with Lewes.

After Isaac Evans learned that his sister’s life with Lewes did not involve a legal marriage, he cut off all communication, and then directed her sisters to do the same. With both her parents dead, the loss of contact with her siblings was deeply wounding to Evans.

Eliot may also have wanted to protect her standing as a serious essayist and translator. Writing unsuccessful fiction could threaten that reputation. Furthermore, Eliot’s goals for her fiction were ambitious. It wasn’t just that she did not want to write something silly. Eliot saw fiction as a vehicle for grappling with the largest questions of her day.

The idea that human beings had arisen through natural selection, rather than divine creation, challenged conventional religious thought. If God was not in charge, as Eliot came to believe, how were human beings to make ethical choices? Only a few months earlier, Eliot had completed her translation of humanist philosopher Baruch Spinoza’s Ethics.

Philosopher Clare Carlisle states that Eliot had “an affinity with [Spinoza’s] thinking, and particularly with his insight into the vast, intricate, ever-shifting constellation of emotion, action, and interaction that shape each human life.”

Though Eliot began her career of writing fiction with strong convictions about why she would write, she was filled with doubt about whether she could create scenes that would elicit the emotional responses from her readers that would motivate them to sympathize with the very ordinary and flawed people she planned to portray in her work.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about George Eliot

. . . . . . . . .

To protect Mary Ann’s anonymity, Lewes approached his friends the Blackwood brothers, publishers of Blackwood’s Magazine as well as of books, on her behalf. Initially he led the publishers to believe that the mysterious author was a friend of his, a shy male cleric. In later correspondence he clarified that the author was not actually a clergyman but did nothing to correct the assumptions regarding gender.

The serialized version of Scenes of Clerical Life appeared anonymously in the magazine. At the end of 1857, when Scenes was about to come out in book form, the publishers pressed for an author’s name. “I shall be resolute in preserving my incognito,” Eliot responded. Recognizing that there would be “curious inquiries” on the part of readers, she announced that “accordingly I subscribe myself … George Eliot.”

In effect, she took the name of the man she regarded as her husband—George—despite their inability to marry. While Eliot liked people to refer to her as Mrs. Lewes, not everyone accepted her under that name. She took Eliot, she said, because “it was a good, mouth-filling, easily pronounced word,” and it’s worth noting that the sounds of the first two syllables name the first two letters of Lewes’s surname.

If Eliot had simply wanted to guard her fiction from judgment based on disapproval of her relationship with Lewes, or if she had wanted to shield her reputation as an essayist from any shortcomings in her abilities as a fiction writer, she could have taken a feminine name as her pen name. Instead, she chose a masculine name, reflective perhaps of her feeling that her ambitions required a masculine identity.

“You may try,” Eliot writes in Daniel Deronda, “but you can never imagine what it is to have a man’s force of genius in you, and to suffer the slavery of being a girl.” Charles Dickens famously saw through the ruse. In a letter thanking “George Eliot” for sending him a copy of Scenes of Clerical Life, he said, “I believe that no man ever before had the art of making himself so mentally like a woman.”

It may have been the complex emotional lives that Eliot portrayed in Scenes of Clerical Life that prompted Dickens’s comment. The collection included “The Sad Fortunes of Amos Barton,” which describes the plight of an Anglican priest falsely slandered by villagers; “Mr. Gilfil’s Love-Story,” about a clergyman who aids the woman he loves after she is accused of murder, even though his love is unrequited; and “Janet’s Repentance,” the story of an alcoholic woman who escapes an abusive husband with the support of a cleric whose theology she does not share.

While now regarded as somewhat awkward in style compared to her later work, Scenes received “discerning applause” and readers of Blackwood’s wondered about the identity of George Eliot. But it wasn’t until the tremendous success of Eliot’s first novel, Adam Bede, that the nom de plume became a problem.

Growing curiosity about the identity of George Eliot

Adam Bede, published in February 1859, attracted far more attention than Scenes of Clerical Life. Like Scenes, it first appeared in Blackwood’s Magazine in serial form before being published as a book. The Blackwoods’ enthusiasm for the story provided Eliot with significantly more money for her first novel than she had received for her series of novellas.

The story of a love rectangle that culminates in the death of a child born out of wedlock and the conviction of its mother for murder, Adam Bede attracted the admiration of many readers, including Dickens and Queen Victoria. The glowing reviews increased public curiosity about the author.

Lewes and Eliot had revealed her identity to publisher John Blackwood in December of 1857. He kept the secret, but as time went on, people around Eliot began to guess that she was the mysterious author of Scenes and Adam Bede. In February of 1859, Lewes flatly denied that his wife was George Eliot when John Chapman, publisher of many of Evans’s essays, confronted him.

Chapman, who was used to Evans sending articles on a regular basis due to her need for money, was suspicious because she had sent him nothing in eighteen months. Other friends noticed that Lewes and Eliot had recently moved into a larger house and purchased linens and china, middle-class luxuries that had previously been beyond their means.

Even Eliot’s estranged brother Isaac bragged that the popular Adam Bede could have been written only by his sister, based on the novel’s depictions of places and situations familiar to his family. When Barbara Bodichon, a friend of Eliot’s who had read an excerpt of Adam Bede, guessed her identity, Eliot asked her to “keep the secret solemnly till I give you leave to tell it,” and her friend complied.

Complications and revelations

The situation soon became more complicated. A man named Joseph Liggins denied rumors that he was the author George Eliot. After his denials were brushed aside, he began to complain that he had not received a penny for Adam Bede. At first, Eliot and Lewes found this somewhat funny, but when a group of men planned a fundraising campaign on his behalf, Eliot became concerned about well-meaning people being caught up in the fraud.

Despite the Liggins rumors, more and more people who knew her began to suspect that Evans was George Eliot. An article denouncing George Eliot as a woman who refused to reveal her identity because of her shame regarding her private life infuriated Eliot. Worse, the article claimed that George Eliot herself had promulgated the Joseph Liggins rumor to sell more books.

It became clear that Eliot’s “incognito,” as she had termed it, had run its course. Blackwood announced his intention to reveal Eliot’s identity. Before his public revelation, Evans and Lewes shared the news that Evans herself was author of Adam Bede, first with an inner circle of close friends (some of whom were deeply offended at having been kept so long in the dark), as well as with Lewes’s adopted sons, whose school fees were paid by Eliot. The boys were delighted to learn that their father’s new wife was a celebrated author.

The secret was officially disclosed in July 1859. By this time Eliot was writing her second novel, The Mill on the Floss. When that novel was published in April of 1860, her identity was widely known, and yet her public continued to refer to the novelist as George Eliot.

Sales of Mill did not suffer from any scandal attached to her relationship with Lewes, and her public continued to refer to the novelist as George Eliot. Her transformation, in fact, was complete. The novelist George Eliot had triumphed over the social limitations Mary Ann Evans Lewes faced as a woman.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

SourcesCarlisle, Clare, ed. Spinoza’s Ethics translated by George Eliot. Princeton University Press, 2019.Eliot, George and J.W. Cross. George Eliot’s Life, as Related in Her Letters and Journals, Everyman’s Library, 1910 (Project Gutenberg, 2013; updated 2021).Harris, Margaret and Judith Johnston, eds. The Journals of George Eliot, Cambridge University Press, 1998.Hughes, Kathryn. George Eliot: The Last Victorian Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998.Nestor, Pauline George Eliot. Palgrave Critical Issues, 2002.Eliot, George Scenes of Clerical Life. Everyman’s Library, 1910. (Project Gutenberg, 2006; updated 2021)

The post How Mary Ann Evans Became George Eliot appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 28, 2022

The Door of Life by Enid Bagnold (originally titled The Squire)

It’s surprising to discover that Enid Bagnold, the author best known for the classic horse story National Velvet, wrote what is considered one of the first novels centered on pregnancy and childbirth. Oddly titled The Squire when first published in England in 1938, it was retitled The Door of Life for the American audience.

This semi-autobiographical novel is an almost meditative reading experience from the perspective of an expectant mother who is soon to give birth to her fifth child. A review from the time of its publication observed:

“Those to whom the act of giving birth to a new human is fraught with terror and dread will see here that it is possible for it to be a wonderful and moving experience. We have never before read of the birth of a baby where all anguish was removed and a deep, fundamental joy was put in its place.”

Even by today’s standards, that sounds so refreshingly positive!

. . . . . . . .

Learn more about Enid Bagnold

. . . . . . . .

From the original review in The Charlotte Observer, November 6, 1938; “Her Writing is Different”: Enid Bagnold, English novelist, is gifted with a very special genius

We can recall no one of her contemporaries who writes at all like her, whose talent coincides with hers at any point. She isn’t whimsical as was James Barry, nor is she full of tricks, as is Gertrude Stein.

She writes with no self-consciousness of being original or different, yet she is that. And much more than that.

A year or so ago her novel National Velvet was being talked about. We were interested then to observe that the book was praised or condemned with equal enthusiasm. Many persons considered it enchanting and “not-to-be-missed,” others thought it “precious,” and “unrealistic.” It had a great success. and it certainly made a lasting impression on many persons, for we still her it talked about.

All this leads up to Mrs. Bagnold’s new book, The Door of Life. It is about an English woman who lives with her young children in a big house with the usual number of servants — butler, kitchen maids, nurses, cooks, gardeners, and so on.

The husband never appears, and his total absence from the story, even in spirit, suggests that Mrs. Bagnold knows more about the childish ways of children than of husbands and fathers.

Not much, that is externally, happens. The core of the story is hidden and must be got at by use of the imagination and quiet consideration. But it is worth the effort. To get the most from this book the reader must put himself into its reading, for its meaning is not obvious, but subtle and faintly concealed. It is delicate, exquisite rather than bold and broadly indicated.

. . . . . . . . .

See also:

Pregnancy in Classic Novels by Women Authors

. . . . . . . . .

Women who are inclined to consider motherhood a chore which must be got through quickly will see a new light in this mother’s love and intelligent consideration for her children in The Door of Life.

And those to whom the act of giving birth to a new human being is fraught with terror and dread will see here that it is possible for it to be a wonderful and moving experience. We have never before read of the birth of a baby where all anguish was removed and a deep, fundamental joy was put in its place. This is a relief.

“Her mind went down and lived in her body, ran out of her brain and lived in her flesh. She had eyes and nose and ears and senses in her body, in her backbone. living like a spiny woodlouse, doubled in a ball, having no beginning and no end. Now the first twisting spate of pain began.

Swim then, swim with it for your life. If you resist, horror and impediment! If you swim, not pain but sensation! Who knows the heart of pain, the central bellows of child-birth which expels one being from another?

None knows it who, in disbelief and dread has drawn back to the periphery, contradicting the will of pain, braking against inexorable movements. Keep abreast of it, rush together, you and your violence which is also you! Wild movements, hallucinated swimming! Other things exist than pain!”

Set off against the mother is her friend whose life still depends upon the admiration and love of men. Their difference is astonishing-the security of the mother, the helplessness of her friend, for she was a woman meant to walk from man to man and never to look back. The five children are as lovable and mischievous a group as we have ever met in a book or in life. They are real children, not the sole product of the imagination.

What is the secret of Mrs. Bagnold’s understanding of children? The answer is simple and inevitable: Enid Bagnold herself. Her publisher tells us that she has had five children of her own and adopted another for each one that she has had “in order that two of the same age may grow up together.”

Add to this talent for children a gift, if not genius, for writing and it is no wonder that she can write such extraordinarily good books. They spring straight out of her own life.

It is our opinion that all young people, married or contemplating marriage, would enjoy and really benefit from reading The Door of Life. It certainly is not a practical course in marriage but its message is meaningful, encouraging, and enlightening.

More about The Door Of Life by Enid Bagnold Reader discussion on Goodreads 1938 review in the NY Times

The post The Door of Life by Enid Bagnold (originally titled The Squire) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 27, 2022

Reading (and Watching) Pride and Prejudice in India

Like most teenagers in India who enjoyed the English classics, Pride and Prejudice came into my life. It prompted me to borrow the Complete Works of Jane Austen from the library and to read all her novels. But if you were to ask me to recall the plots today, Pride and Prejudice is the one that has etched itself most clearly in my mind.

This could also be because I had to study this novel as part of my English Honors program in college. I recall the name of the teacher who took up this book but can’t remember many insights that she left me with.

What comes to mind is that she spoke of it as a “drawing room novel,” as a lot of the action indeed takes place in these various home settings, starting with that of the Bennet family in Pride and Prejudice.

But can one fault the teacher? Jane Austen did write the book in something of a bubble, after all. If there is a historical context to a novel, a teacher can probably reference it for students to think about it. Pride and Prejudice was devoid of any such allusions, except for being referred to as a novel of manners and satire.

Jane Austen wrote with her powers of observation about the world around her, with a subtle critique of the prevalent social mores of her time.

Studying the history of English Literature in India was a very important part of my Honors program. An entire paper was devoted to this, and Legouis and Cazamian’s History of English Literature almost became like a Bible for me throughout those years.

Though many of us didn’t particularly care for having to delve into British history, as it was linked with those periods, it was clear that the writers were influenced by their times. For many of us, Pride and Prejudice is primarily a romance, and interestingly, it was written in the Romantic Period.

Elizabeth Bennet, as the protagonist, is my favorite character, as she was for Jane Austen (and legions of Jane Austen aficionados). Fitzwilliam Darcy is a close second; the fact that after all the pride and the prejudice, they’re able to get together is such a relief to the reader.

The famous opening lines of the novel, “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife,” is still adapted by writers across the world to convey multiple meanings, including political ideas.

The Big Fat Indian Wedding

In a country like India where marriages are still arranged, the Big Fat Indian Wedding is very much a part of the culture. In a land of many languages, communities, and creeds, parents are always keen that their offspring choose within their station, though no one minds upward mobility — just like Mrs. Bennet.

Matrimonial websites are now replacing family matchmakers and wedding bureaus, and many have mushroomed online, based upon community, religion, caste, and perhaps even sub-sect. The amount of information provided for matchmaking is mind boggling.

Some amount of subterfuge does form part of the experience, as families are probably reluctant to share job details, especially the salary, more so when it comes to girls.

A friend told me about how she had pegged down her daughter’s position and emoluments for fear of boys and their families being daunted by a woman, who will expect equality in the marriage, which in India’s patriarchal society, is still a distant dream.

Luckily for the daughter, the deception didn’t have to continue for long, as she met and fell in love with a European colleague while on a foreign posting and they lived happily ever after, but not before the groom’s family came down and celebrated the Big Fat Indian wedding in her hometown.

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy …

Miniseries & Film Adaptations of Pride and Prejudice

. . . . . . . . . .

Is it little wonder then that TV serial makers and filmmakers saw the potential of Pride and Prejudice and opted for remakes to suit an Indian audience?

When India’s national channel, Doordarshan, got into commercially broadcasted serials and movies, a black-and-white (color television was yet to make its entry) adaptation of Pride and Prejudice slipped into our living rooms and charmed the nation.

Called Trishna and made in Hindi, the serial kept to the storyline of the original novel. I was completely enamored of Rekha, the Indian Elizabeth Bennet (played by Sangeeta Handa) and even more so by the dishy Tarun Dhanrajgir, who is called Rahul. The essence of Darcy was so well captured by this actor that one can almost imagine that Austen had created her character for this Indian Rahul.

The serial ran for just one season of 13 episodes, each eagerly awaited and subsequently discussed in detail with other fans.

. . . . . . . . . .

Bride & Prejudice is available for streaming on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Later in 2004, the British Indian filmmaker, , released an adaptation of Pride and Prejudice titled Bride and Prejudice, filming the story in English.

Buoyed by the success of her soccer film, Bend It Like Beckham, the director ambitiously cast Aishwariya Rai, the famous actress and one-time Miss World as Lalita Bakshi, the Elizabeth Bennet character. The American actor Martin Henderson played the role of Will Darcy, a Los Angeles hotelier.

Sparks fly when the couple meets at a wedding in Amritsar, India. As she did it with the very successful Bend It Like Beckham, Chadha used her exposure to the East and the West to make a heady blend of the two, with the characters moving from India to London to Los Angeles.

The picture captures all the pageantry, fanfare, and colors of India in exaggerated fashion, with the characters breaking into song at the slightest provocation — the film is styled as a musical. I found the televised serial Trishna much more interesting, but many enjoyed Chadha’s interpretation of the novel. It may have even contributed to tourism, inspiring Western viewers to experience Indian culture firsthand.

Though ostensibly simple, even the mere title of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, packs a wealth of meaning. In addition to romantic entanglements, pride and prejudice — governed by the ego — are responsible for the many complications of human relationships.

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Reading (and Watching) Pride and Prejudice in India appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 22, 2022

Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson (1942)

Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson was the noted naturalist’s first book, published in 1942. Even in her debut publication, reviewers noted the lyrical quality she applied to scientific prose to make it compelling and readable.

Not nearly as renowned as Carson’s classic Silent Spring (1962), Under the Sea Wind has in its quiet way also stood the test of time, having been reissued in several editions by various publishers since its debut. The 2007 Penguin Classics encapsulated it:

“Rachel Carson—pioneering environmentalist and author of Silent Spring—opens our eyes to the wonders of the natural world in her groundbreaking paean to the sea.

Celebrating the mystery and beauty of birds and sea creatures in their natural habitat, Under the Sea-Wind—Rachel Carson’s first book and her personal favorite—is the early masterwork of one of America’s greatest nature writers.

Evoking the special mystery and beauty of the shore and the open sea—its limitless vistas and twilight depths—Carson’s astonishingly intimate, unforgettable portrait captures the delicate negotiations of an ingeniously calibrated ecology.”

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Rachel Carson

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review of by Rachel Carson in The Louisville Courier-Journal, January 11, 1942: “The Sea’s Eternal Drama”

In beautiful lyrical prose, Rachel L. Carson in Under the Sea Wind stirs the imagination with her portrayal of the endlessness of life and death in the sea. For the sea was the cradle of all life, and still is a shelter for an endless array of living forms in the most eternal cycle of life that is to be found on earth.

Miss Carson is by training a zoologist; yet, unlike most scientists, she is a talented writer as she so thoroughly proves in this, her first book. A true lover of the sea, she tells with scientific accuracy of the life of the Atlantic coast, from the soaring gulls on high to the forms that creep over the continental slope and down into the perpetual darkness of the ocean’s abyss.

. . . . . . . . . . .

See also: The Sense of Wonder by Rachel Carson

. . . . . . . . . . .

Her style is as readable as that in any animal story, but without most of the anthropomorphism of which so many writers are guilty. She has tried to present the activities of typical oceanic animals from what may be imagined to be their point of view.

Upon reading the book one has the feeling of being an invisible spectator of an eternal drama that began million of years ago and which promises to continue indefinitely, heedless of man and his exploitation of the continents. It is the same feeling one achieves when alone on a starry night he gazes upward into the immensity of space.

Some biologists may scorn Miss Carson’s practice of writing particularly about one individual of a species of Scomber the mackerel, of Blackfoot the sanderling, and Anguilla the eel-but the reviewer believes that in so doing she has been better able to leave herself out of the picture.

Incidentally, it may be remarked that in recent years biological study has shifted largely from that of preserved specimens to that of animal communities, and Under the Sea Wind is one of the first popular books to present this newer knowledge to the layman. Included in the book are several artistic plates and an illustrated glossary with descriptions of more than a hundred plants and animals of the sea.

. . . . . . . . . .

Under the Sea Wind on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson (1942) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 19, 2022

The Sense of Wonder by Rachel Carson (1965)

The Sense of Wonder by Rachel Carson, best known for the environmental classic Silent Spring (1962) was published in 1965, a year after her death.

This widely praised book was intended to be enjoyed by children and parents together, was expanded from an essay Carson wrote in the 1950s. It’s designed to inspire families to explore and appreciate the wonders of nature together.

The book was originally embellished with black & white as well as color photographs by Charles Pratt, many of which were taken along the Maine coast, where Carson enjoyed spending summers.

Republished in 2017, the book is as fresh and relevant as it ever was — perhaps even more so, given the alarming state of the environment. The new edition features new photography by Nick Kelsh. The publisher, HarperCollins, offers this description of the new edition:

“First published a half-century ago, Rachel Carson’s award-winning The Sense of Wonder remains the classic guide to introducing children to the marvels of nature.

In 1955, acclaimed conservationist Rachel Carson began work on an essay that she would come to consider one of her life’s most important projects. Her grandnephew, Roger Christie, had visited Carson that summer at her cottage in Maine, and together they had wandered the surrounding woods and tide pools.

Teaching Roger about the natural wonders around them, Carson began to see them anew herself, and wanted to relate that same magical feeling to others who might hope to introduce a child to the beauty of nature. ‘If a child is to keep alive his inborn sense of wonder,’ writes Carson, “he needs the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with him the joy, excitement and mystery of the world we live in.’

The Sense of Wonder is a timeless volume that will be passed on from generation to generation, as treasured as the memory of an early-morning walk when the song of a whippoorwill was heard as if for the first time. Featuring serene color photographs from renowned photographer Nick Kelsh, this beautiful book “helps us all to tap into the extraordinary power of the natural world.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Rachel Carson

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review in the Alamogordo Daily News (NM), December 19, 1965: Many readers will remember Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which caused much discussion and alarm a few years past.

Some may have read this same text in magazines, but for the parent of small children I can think of no more exciting experience than reading and examining this new book— The Sense of Wonder. The title is exceptionally apt, and the text is both stimulating and delightful.

Through these pages Rachel Carson tells how she presented the wonders of nature to a small nephew and with what almost unbelievable results. She believes that a child has this natural wonder about life and nature, but that it soon becomes calloused over and crushed back until by the time we are grown up most of us have lost this priceless gift.

A child’s world is bright and shining-new and wonderful; it is only when we disregard their enthusiasm and show indifference that they begin to lose the freshness and delight of the world around them. In helping to keep their wonder alive, we will remind ourselves of its existence.

We will regain our own “seeing eyes” and “hearing ears.” We may rediscover that the world is a marvelous place, full of exquisite sights and sounds and daily miracles all around us. From the tiniest insects to the rainbow, or the brilliant etching of the lightning against a black sky, she brings to mind all the enchantments of nature.

“If a child is to keep alive his inborn sense of wonder… he needs the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with him the joy, excitement and mystery of the world we live in,” says Miss Carson, and as in all other sharing, one soon finds that in helping the child to retain his own gift for discernment, we will have gained fully as much as we have given.

Some rare souls such as poets and artists never lose their appreciation for natural beauty, but for most of us, “the world is too much with us… late and soon, with getting and spending we lay waste our powers,” to quote another gifted writer.

We rush here, and dash there always in such a hurry that we miss half that transpires about us. The lively, unconscious rhythm of a bird’s flight, or its sweet and joyous call; the delicate tint of color in a sunset sky, or the sheen of sunlight on a leaf. All these things have a soothing quality for the heart of mankind, if he should take time to notice and ponder them.

As a gift for yourself, and one which you can share with many others, both young and old, take Rachel Carson’s lovely book and enjoy it. The photographer too, has given us a thing of beauty in his various mood-setting, graphic pictures of some of the beauties of nature such as dew-drops, leaves, and butterflies.

You will find in this book something of your lost childhood, and something of the great mystery of creation for which we should be thankful every day of our lives. If you enjoyed Miss Carson’s The Sea Around You. you will indeed be captivated by this one.

And when you take some small trusting hand in yours and go forth to explore together, you will thank her for reminding you that life is a wonderful experience and a that in keeping the joy of it in our hearts and lives will not only enrich ourselves, but all others with whom we come in contact.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Sense of Wonder on Bookshop* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Sense of Wonder by Rachel Carson (1965) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 15, 2022

The Sea Around Us by Rachel Carson (1951)

Rachel Carson’s long-term legacy rests on her environmental classic, Silent Spring (1962), so it’s surprising to learn that a decade earlier, she had another smash bestseller. The Sea Around Us by Rachel Carson (1951) is a gracefully written, meticulously researched work of nonfiction making the case for the primacy of the oceans, a plea that has gone unheeded.

In 1948, she completed the first chapter of The Sea Around Us. Marie Rodell, a fledgling agent, took Carson on as her first client. Portions of the book were first published as a series of long articles for The New Yorker.

By July of 1951, the entire book had been published and made its appearance on The New York Times’ bestseller list, where it stayed for 86 weeks. It won the National Book Award, in January 1952.

Oxford University Press reissued the book in 2018, providing this description:

“Originally published in 1951, The Sea Around Us is one of the most influential books ever written about the natural world. Rachel Carson’s ability to combine scientific insight with poetic prose catapulted her book to the top of The New York Times best-seller list, where it remained for more than a year and a half.

Ultimately it sold well over a million copies, was translated into twenty-eight languages, inspired an Academy Award-winning documentary, and won both the National Book Award and the John Burroughs Medal.

The Sea Around Us remains as fresh today as when it first appeared over six decades ago. Carson’s genius for evoking the power and primacy of the world’s bodies of water, combining the cosmic and the intimate, remains almost unmatched: the newly formed Earth cooling beneath an endlessly overcast sky …

The seas sustain human life and imperil it. Today, with the oceans endangered by the dumping of medical waste and ecological disasters such as the Exxon oil spill in Alaska, the gradual death of the Great Barrier Reef, and the melting of the polar ice caps, Carson’s book provides a timely reminder of both the fragility and the centrality of the ocean and the life that abounds within it. Anyone who loves the sea, or who is concerned about our natural environment, will want to read, or re-read, this classic work.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Rachel Carson

. . . . . . . . . .

The reviews for so unusual a work of nonfiction, presenting scientific fact with gorgeous language, were nearly universally laudatory. Here’s one typical review:

A 1951 review of The Sea Around Us by Rachel Carson

From the original review by E.H. Martin in the Baltimore, MD, Evening Sun, June 30, 1951: Brilliant Study of The Sea

That anyone should attempt within the covers of a book of only 216 pages to do justice to such a vast subject as the oceans of the earth in all of their aspects is remarkable enough. Even more remarkable is the fact that in The Sea Around Us, Miss Rachel Carson’s effort to accomplish this feat has resulted in not only a superb example of scientific reporting but also a work of art.

From the gray beginnings when “the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep.” Miss Carson tells the cosmic story of the origins of the seas and the continents, and of the creation in the primeval waters of the first living cells. This is a drama the span of which is measured in hundreds of millions of years. It is also a drama which comes alive under Miss Carson’s talent for compression and simplification without distortion of the facts.

Throughout this book the reader finds a prodigious amount of factual information, a solid body of scientific evidence, all handled with an almost casual ease.

. . . . . . . . .

See also: Silent Spring by Rachel Carson

. . . . . . . . .

When there is disagreement among experts, when alternative hypotheses must be balanced and weighed to explain matters in the absence of definite proof, Miss Carson says so. So compelling, however, is the whole, mighty evolutionary story as she tells it that one is disposed to accept her without question as guide to the chronicle of events which took place eons before man came upon the scene.

It is not, however, with how the oceans came to be that the author is primarily concerned. Rather the main body of the book deals with the seas and their mysteries as they now exist; with their teeming life, their effects on our climate and with those forces of the sea that are only just coming to be comprehended.

As Miss Carson notes, after we have subtracted the shallow areas of the continental shelves and the scattered banks and shoals where at least the pale ghost of sunlight moves over the underlying bottom, about half the earth remains covered by miles-deep, lightless water, that has been dark since the world began.

This is the area of mystery which has withheld its secrets longer than any other. The story of what the abyssal depths are beginning to yield in the way of information as to their nature and the life they contain is one of the most fascinating the author has to tell.

With a happy combination of poetic, economical prose and sober grasp of the facts. Miss Carson deals with such diverse topics as how waves are formed, their length of “fetch” and their awesome power; the fabulous variety of life in the seas; the influence of tides and the role of the sea in the making of weather.

This last topic. treated in detail in a chapter entitled “The Global Thermostat,” throws some fresh light on the climatological phenomenon of increasing warmth in the Arctic first noted by the Swedish glaciologist Hans Ahlmann.

Miss Carson, whose first published work appeared in The Sunday Sun, taught for a few years at the Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland. She now holds the position of editor-in-chief of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

On the basis of just one chapter of her book, which appeared in the Yale Review, she won the George Westinghouse Science Writing Award for 1950. It only needs to be added that The Sea Around Us as a whole is written as admirably and fascinatingly as was that particular excerpt.

. . . . . . . . .

The Sea Around Us on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Sea Around Us by Rachel Carson (1951) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 13, 2022

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson (1962): An Environmental Classic

Silent Spring (1962) is the most enduring work of nonfiction by Rachel Carson (1907–1964), the noted American marine biologist and groundbreaking environmentalist.

In this book, Carson made a passionate argument for protecting the environment from manmade pesticides. Written with grace as well as passion, it’s an indictment of the pesticide industry that arose in the late 1950s. It lays out a disturbing view of the damage these chemicals can cause to birds, bees, wildlife, and plant life.

Rachel Carson’s official website recognizes how prescient she was: “Silent Spring inspired the modern environmental movement, which began in earnest a decade later. It is recognized as the environmental text that changed the world.”

From this site’s biography of Rachel Carson:

“The public’s growing awareness of the dangers of chemicals created a natural readership for Silent Spring, serialized in The New Yorker beginning June 16, 1962, and published as a book on September 27, 1962.

Silent Spring sold more than 100,000 copies in the first week and was on the bestseller list by Christmas. By now it has sold more than two million copies and has been translated into more than twenty languages.”

. . . . . . . .

Learn more about Rachel Carson

. . . . . . . .

Carson was subject to backlash and attacks from the pesticide industry, which conspired to discredit her. A 2012 article in Yale Environment 360 titled “Fifty Years After Silent Spring, Attacks on Science Continue” observed:

“When Silent Spring was published in 1962, author Rachel Carson was subjected to vicious personal assaults that had nothing do with the science or the merits of pesticide use. Those attacks find a troubling parallel today in the campaigns against climate scientists who point to evidence of a rapidly warming world.”

Rachel Carson has been more than vindicated for her contributions to contemporary environmentalism. Newspaper reviews were generally positive, if genuinely surprised and disturbed by the case she laid out about pesticides, particularly DDT. Here is one such review from when the book was published, after it was serialized.

. . . . . . . . .

See also:

27 Quotes from Silent Spring by Rachel Carson

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review of Silent Spring in the Calgary Herald, October 6, 1962: In Silent Spring, Rachel Carson tells a story that intelligent citizens will find both illuminating and disturbing. Imagine a spring season without bird song. Miss Carson writes:

“On the morning that had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, wrens and scores of other bird voices, there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marsh.

On the farms the hens brooded, but no chicks hatched. The farmers complained that they were unable to raise any pigs the litters were small and the young survived only a few days. The apple trees were coming into bloom but no bees droned among the blossoms, so there was no pollination and there would be no fruit.”

Such a sterile, silent world, of course, does not exist. But some day it may, Miss Carson warns, because of care less and indiscriminate use of insecticides and other chemicals. Poisons of this kind are often more effective than the users realize: if they kill insects, weeds, rodents and other pests, they may also kill other forms of life and even penetrate human germ cells to alter the structure of heredity, thereby initiating a chain of evil that is in part irreparable and irreversible.

Many of them are capable of destroying the enzymes that protect the body from harm, of blocking the oxidation process, of causing malignancies.

It is not Miss Carson’s contention that such chemicals should never be used. She argues only that their ultimate effect upon the environment must be thoroughly studied and understood.

For example, in large areas throughout the U.S. midwest and New England a certain DDT spray was used to combat Dutch elm disease. The spray seeped into the earth and was absorbed by the cutworms, which in turn were eaten by robins: The result was thousands of dead robins-and meanwhile the Dutch elm disease continued largely unchecked, because the truly effective means of curbing it seems to be scientific pruning or the destruction of diseased trees.

Similarly, in the 1950s the Canadian government attempted to protect forests from the ravages of the spruce budworm by extensive aerial spraying. Millions of salmon were killed when the spray contaminated rivers and streams, but each year budworms reappeared in great numbers.

Miss Carson makes it clear that insect pests, insect-borne diseases and such cannot be ignored, but she questions whether even carefully controlled lethal spraying with chemicals is the answer. Scientists should look rather for a biological solution of the problem she indicates.

For example, it was discovered that a Canadian shrew devours sawfly cocoons, Newfoundland was plagued with sawflies, and when these shrews were introduced to the island, the end of the sawfly problem was in sight. There is, Miss Carson believes, a whole battery of such solutions awaiting scientists patient enough to look for them. Miss Carson says:

“If the Bill of Rights contains no guarantee that a citizen shall be secure against lethal poisons distributed either by private individuals or by public officials, it is surely only because our forefathers, despite their considerable wisdom and foresight, could conceive of no such problem.”

U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, in a report on Silent Spring, adds: “We need a Bill of Rights against the Twentieth Century poisoners of the human race. The book is a call for immediate action and for effective control of all merchants of poison.”

Rachel Carson is a graduate of Pennsylvania College for Women and has taken an advanced degree in zoology at Johns Hopkins University. At first associated with the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries in Washington, she was later appointed editor-in-chief for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Her best-known book is The Sea Around Us (1951), a tremendous popular and critical success for which she won the Gold Medal of the New York Zoological Society, the John Burroughs Medal, the Gold Medal of the Geographical Society of Philadelphia and the National Book Award.

Much of the material in Silent Spring has been drawn from about 2,000 pages of testimony submitted in connection with a suit brought by Robert Cushman Murphy and other Long Island citizens against the State of New York for “needless and highly destructive” spraying of sections of Long Island. The case finally reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to hear it on technicality.

Using this material as a point of departure, Miss Carson spent some four years gathering further relevant data from scientists all over the world. Only then did she begin the formidable job of organizing her facts in a continuous and readable narrative.

The result has been called “an eloquent protest in behalf of the unity of all nature, a protest in behalf of life.”

. . . . . . . . .

Silent Spring on Bookshop.org*

Silent Spring on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Silent Spring by Rachel Carson (1962): An Environmental Classic appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 12, 2022

“Oho, What Next?” Stella Benson’s Edit of Pull Devil, Pull Baker (1933)

In the third chapter of Pull Devil, Pull Baker, “Oho, What Next? …” Stella Benson questions her role in this book: “Sometimes, I wonder whether I am editing the Count de Savine or he me. What seems to me the extreme remoteness of his point of view makes me quite giddy.”

This excerpt is from Nicola Darwood’s Afterword to Pull Devil, Pull Baker, originally published in 1933 and reissued by Boiler House Press (2022). All quotations come from the latter edition. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

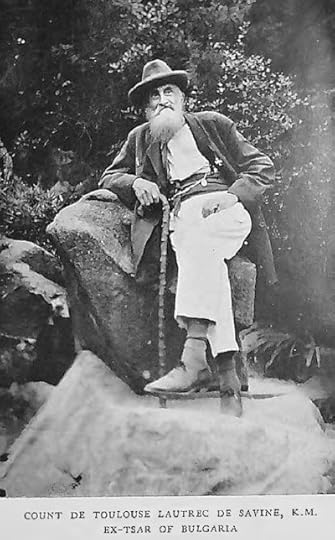

Editing Count de Toulouse Lautrec de Savine

Benson’s thoughts on being an editor are illuminating as she occasionally edits, but often reproduces verbatim, Count Nicolas de Toulouse Lautrec de Savine’s accounts of his extraordinary and often outrageous escapades, escapades which might lead a reader to question that such a man existed.

His existence is not in doubt for Benson or for “hundreds of persons all over China.” What she does wonder about, though, is his veracity as she highlights the apparent unreliable nature of the Count de Savine’s narrative:

“It would be difficult,” Benson states, “to say how many of his stories are literally true. He is a symbol — not only in our eyes but in his own, and to insist of the literal truth from a living symbol would be ungracious.”

Some of these doubts arise, perhaps, from the Count’s loquacious description of his lineage. Descended from both French and Russian aristocracy, he belongs “to one of the most distinguiched aristocratic famelys of Europe” (Benson preserves the Count’s misspellings, though she occasionally provides a clarifying footnote).

. . . . . . . . .

Stella Benson in 1931

. . . . . . . . .

He cites one ancestor whose dying words at the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745 were “on moeur mais on ne se rend pas” (which can translate as “we moan but we don’t surrender”), a fitting motto for the Count, I would argue. Benson continues to question the complete truthfulness of the Count’s stories, although acknowledging that they derive from fact:

How much of it must we believe? Surely, very catholic memories imply a catholic experience. To take an ell, one must at least have been given the first inch. Nobody could tell a good fish story without having once caught at least a stickleback. There is no smoke without fire─no hot air without a spark of flame somewhere. Something must have happened to the Count de Savine, to enable him to describe everything.

She encourages the reader to indulge in an act of “spontaneity” when reading the Count’s stories, whether we believe him or not for, as Benson states, ‘he has hit upon a manner conspicuously appropriate to the story he has to tell.”

Stella Benson and the Count are “unnatural collaborators”

Benson first met the Count on Monday, April 13, 1931, in the Matilda Hospital in Hong Kong where he supplied her with a wealth of stories written in his own inimitable style, together with a cache of photographs of women.

Following Benson’s faithful transcription, The English Review agreed to publish some of the Count’s stories, and additional material was published in Adelphia, Everyman, Fortnightly Review, Review of Reviews, Spectator, Vanity Fair and the New Yorker, bringing the stories to the attention of a wide readership in the UK and the USA.

The full collection of stories, interspersed with Benson’s pithy commentary, was published in 1933 by Macmillan & Co in London and Harper & Brothers Publishers in New York.

Benson writes in Pull Devil, Pull Baker that she and the Count are “unnatural collaborators,” but we also get a sense in the opening chapter of the compassion that the Count evokes in her.

Benson recounts how her heart was ‘wrung’ on their first meeting, when it seemed to her “that the Count now, in the bleak freedom of old age, was less and less free,” but also that she recognises that the promise of the publication of his stories has revitalised him so that he has been “reborn as a literairy men.”

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

“Stories are his currency”By the time the Count and Benson met in 1931, he was seventy-seven years of age. Penniless and reliant on charity, his tales were, for him, invaluable: “Stories,” Benson tells us “are his currency” as he exchanges a tale for ten dollars, feeling quite aggrieved if he is offered a mere five dollars for his tale.

Those stories though are told with verve, and excitement, with the Count always portraying himself as the hero or the hour, as the “great admirer of ladies” or as a feminist. This last self-identification is predicated on the high regard in which he holds mothers who:

… give to us our birth and put us on our fiets, and before it, form us in their suffering, the blood of their blood, the boneses of their women’s bones—maternity, who take their beauty, their helth, and some times their lifes. That brogth me to my great appressiation of womens, make me an ardent and confessed feminist. More, will I say, brogth me to the Culte of Womens . . .

His stories veer from ones in which he extols the virtues of his numerous “sweathearts,” and swashbuckling stories which would seem almost unbelievable but while the Count’s stories, fantastical and written with flair and panache, are enjoyable tales, arguably what is of more interest are the ways in which Benson has both edited these stories and added her own commentary.

She often interrupts the Count’s version of events with witty asides, discussions of editing practices, the addition of a remark meant to clarify points made by the Count, an extra story which acts as a counterpoint to the Count’s story, or a tangential discussion, for example about the title of the book.

Benson provides an account of editing decisions

At various points in Pull Devil, Pull Baker, Benson provides an account of her editing decisions and her own relationship with the Count’s stories. In chapter twelve, “Analysis by the Devil of the Baker’s Wares,” she considers the stories that she’s accepted and those which she has refused. Benson also discusses her decision to refuse “to have the shortcomings of grammar, spelling and vocabulary improved away.”

This decision is not taken so that she can hold the Count up to ridicule (after all, the Count is not a native English speaker) nor on account of “their ‘quaintness’ and occasional amusement,” but rather because she believes that the Count’s style “has great individuality and ingenuity.”

The penultimate chapter contains the Count’s story of “The Bygame Lizaro, the Blue Barth of Our Days, Mitting in a Prisoner Train, by my Transport from the Steps of the Bulgarian Thron to Tsar’s Jail at Petrograd in a Jail Carr.”

It is a continuation of the story of the Count’s claim, enthronement and removal from the position of the Czar of Bulgaria told earlier in Pull Devil, Pull Baker, and Benson wonders whether it is “our autobiographer’s truly true story, in disguise,” with every other story being merely “wish-fulfillment […] a romance.”

. . . . . . . . .

Pull Devil, Pull Baker is available on Amazon U.S.*, Amazon UK,*

directly from Boiler House Press, and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . .

What, Benson wonders, counts as truth? Is it the stories that the Count tells? Is it the editor’s narrative, interruptions and retellings?

She also considers the reader’s need for stories, for romance in a world that has seen the ‘war to end all wars’ in which lives were destroyed or ruined, where people “have adjusted themselves to the feeling of a world crumbling beneath them” and who find themselves “wary of surprises, through living all our lives in such a quait and quait unexpected world.”

But in contrast, as Benson states, the Count was born into a well-regulated world; his excitement comes in defying that world, in ‘tumbling in and out of grooves at right angles.’

In chapter fifteen, “A Draw is Declared: Baker and Devil Shake Hands,” Benson writes very effectively, and compassionately, about the “tug-of-war” between Baker (the count) and Devil (the editor). Here, as Benson concludes:

are the adventures of an adventurer who made his own destinations in a world that was not round—and believed in the destinations, even after he had walked past them. Here are the memories of an old man who has never grown old enough to be ashamed of his youth—who has never been ashamed of Romance, or of anything else in capital letters—of Experience—of Danger—of Reform—of Manhood—of Womanhood—of the Soul—of Love—of Life . . .

Leaping from frying pans to fires

As Benson says of the Count: “The world for him was really nothing but a series of frying-pans and fires, and his whole career a mere leaping from one to the other.”

In Pull Devil, Pull Baker, the reader is given a ringside seat; we can watch the Count jump from the frying pan into the fire and marvel at his escapades. We are fortunate indeed that we can sit on the sidelines, reading Benson’s commentary and the Count’s stories, stories that are “expressed with dash and [which] must be read with dash.”

But while we may read “with dash,” we can also appreciate Benson’s skill in bringing the Count’s colourful stories to our attention, a collection of “fragmentary, odd and spicy words […] sugared with brittle romance.”

Pull Devil, Pull Baker is no mere sugared confection, nor, as Benson believed, a “stunt — because it is not written by a writer,” but rather an extraordinary text which demonstrates Benson’s wit and generosity, but also her ability to experiment with form and genre.

Contributed by Nicola Darwood, a senior lecturer in English Literature at the University of Bedfordshire, UK. Her research focuses mainly on twentieth-century women writers; she has published work on Elizabeth Bowen, including A World of Lost Innocence: the fiction of Elizabeth Bowen (2012), and Stella Benson.

She is the co-editor of Interwar Women’s Fiction: ‘Have Women a sense of Humour?’ (2020) and Fiction and ‘The Woman Question from 1850 to 1930 (2020) and Retelling Cinderella: Cultural and Creative Transformations (2020) and is co-chair of the Elizabeth Bowen Society and co-editor of The Elizabeth Bowen Review.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post “Oho, What Next?” Stella Benson’s Edit of Pull Devil, Pull Baker (1933) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 10, 2022

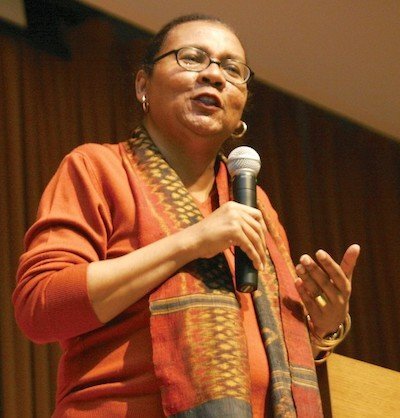

Love, Resistance, & Hope: 25 quotes by bell hooks

The selection of quotes by bell hooks presented here are arranged by her favored themes of a new vision of love; the intersection of race, patriarchy, feminism, and capitalism, demonstrate how these elements determine lives and the hope that comes with resistance.

When the extraordinarily prolific and brilliant writer bell hooks passed away in December 2021, she left behind a tremendous gift for her countless readers: a legacy of thirty adult non-fiction works that will satisfy every reader of this deep thinker and cultural commentator.

While researching the life of bell hooks, I discovered the wisdom in her work that provides the potential to change every reader’s life and perspective.

Love in its many forms“The wounded heart learns self-love by first overcoming low self-esteem.” (All About Love: New Visions, 1999)

. . . . . . . . . .

“All too often women believe it is a sign of commitment, an expression of love, to endure unkindness or cruelty, to forgive and forget. In actuality, when we love rightly we know that the healthy, loving response to cruelty and abuse is putting ourselves out of harm’s way.” (All About Love: New Visions, 1999)

. . . . . . . . . .

“But many of us seek community solely to escape the fear of being alone. Knowing how to be solitary is central to the art of loving. When we can be alone, we can be with others without using them as a means of escape.” (All About Love: New Visions, 1999)

. . . . . . . . . .

“The word ‘love’ is most often defined as a noun, yet all the more astute theorists of love acknowledge that we would all love better if we used it as a verb.” (All About Love: New Visions, 1999)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Time and time again when I talk to individuals about approaching love with will and intentionality, I hear the fear expressed that this will bring an end to romance. This is simply not so. Approaching romanic love from foundation of care, knowledge, and respect actually intensifies romance.” (All About Love: New Visions, 1999)

. . . . . . . . . .

“When we understand love as the will to nurture our own and another’s spiritual growth, it becomes clear that we cannot claim to love if we are hurtful and abusive. Love and abuse cannot coexist. Abuse and neglect are, by definition, the opposite of nurturance and care.” (All About Love: New Visions, 1999)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Reviewing the literature on love I noticed how few writers, male or female, talk about the impact of patriarchy, the way in which male domination of women and children stands in the ways of love.” (All About Love: New Visions, 1999)

. . . . . . . . . .

“The one person who will never leave us, whom we will never lose, is ourself. Learning to love our female selves is where our search for love must begin.” (Communion: The Search for Female Love, 2002)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Love is a combination of care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect and trust.” -(Communion: The Female Search for Love, 2002)

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about bell hooks

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

“The soul of our politics is the commitment to ending domination.” (Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics, 2000)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Once upon a time black male ‘cool’ was defined by the ways in which black men confronted hardships of life without allowing their spirits to be ravaged. They took the pain of it and used it alchemically to turn the pain into gold. That burning process required high heat. Black male cool was defined by the ability to withstand the heat and remain centered.” (We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, 2003)

. . . . . . . . . .

“…The struggle to end sexist oppression that focuses on destroying the cultural basis for such domination strengthens other liberation struggles. Individuals who fight for the eradication of sexism with struggles to end racism or classism undermine their own efforts. Individuals who fight for the eradication of racism or classism while supporting sexist oppression are helping to maintain the cultural basis of all forms of group oppression.” (Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, 2014)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Any black person who clings to the misguided notion that white people represent the embodiment of all that is evil and black people all that is good remains wedded to the very logic of Western metaphysical dualism that is the heart of racist binary thinking. Such thinking is not liberatory. Like the racist educational ideology it mirrors and imitates, it invites a closing of the mind.” (Rock My Soul: Black People and Self-Esteem, 2003)

. . . . . . . . . .

“No black woman writer in this culture can write ‘too much.’ Indeed, no woman writer can write ‘too much’… No woman has ever written enough.” (Remembered Rapture: the Writer at Work, 1999)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Why is it so difficult for many white folks to understand that racism is oppressive not because white folks have prejudicial feelings about blacks (they could have such feelings and leave us alone) but because it is a system that promotes domination and subjugation? (Killing Rage: Ending Racism, 1995)

. . . . . . . . . .

“All of our silences in the face of racist assault are acts of complicity.” (Killing Rage: Ending Racism, 1995)

. . . . . . . . . .

bell hooks page on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

“The process begins with the individual woman’s acceptance that American women, without exception, are socialized to be racist, classist and sexist, in varying degrees, and that labeling ourselves feminists does not change the fact that we must consciously work to rid ourselves of the legacy of negative socialization.” (Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, 1981)

. . . . . . . . . .

“It is obvious that many women have appropriated feminism to serve their own ends, especially those white women who have been at the forefront of the movement; but rather than resigning myself to this appropriation I choose to re-appropriate the term ‘feminism’, to focus on the fact that to be ‘feminist’ in any authentic sense of the term is to want for all people, female and male, liberation from sexist role patterns, domination, and oppression.” (Ain’t I A Woman: Black Women and Feminism, 1981)

. . . . . . . . . .

“The moment we choose to love we begin to move against domination, against oppression. The moment we choose to love we begin to move towards freedom, to act in ways that liberate ourselves and others.” (Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations, 2012)

. . . . . . . . . .

“We can’t combat white supremacy unless we can teach people to love justice. You have to love justice more than your allegiance to your race, sexuality and gender. It is about justice.” (Interview with Jet magazine, 2013)

. . . . . . . . . .

“The first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves. If an individual is not successful in emotionally crippling himself, he can count of patriarchal men to enact rituals of power that will assault his self-esteem.” (The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, 2004)

. . . . . . . . . .

“The function of art is to do more than tell it like it is — it’s to imagine what is possible.” (Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations, 2012)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Dominator culture has tried to keep us all afraid, to make us choose safety instead of risk, sameness instead of diversity. Moving through that fear, finding out what connects us, reveling in our differences; this is the process that brings us closer, that gives us a world of shared values, of meaningful community.” (Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope, 2003)

. . . . . . . . . .

“To build community requires vigilant awareness of the work we must continually do to undermine all the socialization that leads us to behave in ways that perpetuate domination.” (Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope, 2002)

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Nancy Snyder, who writes about women writers and labor women. After working for the City and County of San Francisco for thirty years, she is now learning everything about Henry David Thoreau in Los Angeles.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Love, Resistance, & Hope: 25 quotes by bell hooks appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 8, 2022

Mansfield Park by Jane Austen (1814) — Plot summary and analysis

Jane Austen by Sarah Fanny Malden (1889) offers a 19th-century view of Jane Austen’s works. The following analysis and plot summary of Mansfield Park by Jane Austen (1814) focuses on her third published novel, and the one considered most controversial.

Mansfield Park is the story of Fanny Price, sent by her impoverished family to be raised in the household of a wealthy aunt and uncle. The story follows her into adulthood and is a commentary on class, family ties, marriage, and the status of women.

The novel went through two editions before Jane Austen’s death (1817) but didn’t receive any public reviews until 1821. Critical reception for this novel, from that time forward, has been the most mixed among Austen’s works.

In an introduction to a contemporary edition, Kathryn Sutherland portrays Mansfield Park as a darker work than Austen’s other novels, because it challenges “the very values (of tradition, stability, retirement, and faithfulness) it appears to endorse.”

The 1889 publication of Malden’s Jane Austen was part of an Eminent Women series published by W.H. Allen & Co., London. The following excerpt is in the public domain:

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Jane Austen

. . . . . . . . .

When Pride and Prejudice came out in 1813, it completed the series of Jane Austen’s earlier writings, excepting only Northanger Abbey, which was not then in her hands for publication.

The two novels that had already appeared were finished before she was four-and-twenty; those that followed were not begun till she was well over thirty, and I think that, even without the authority of dates, no one could doubt that Mansfield Park, Emma, and Persuasion belong to a later stage of authorship than Sense and Sensibility or Pride and Prejudice.

They are no less brilliant, but they are more mature; the motives and actions of the dramatic personæ are more complex; there is less rapidity in the working out (rapidity is usually a sure sign of youth), and the satire is a little softened.

The feelings expressed, too, are more womanly and less girlish. In both the earlier novels, the predominant passion is the love of the sisters for each other; the lovemaking is gracefully worked out and properly adjusted, but on the lady’s side it is left very much to our imagination, and it is scrupulously kept under till the gentleman has revealed his devotion.

Mansfield Park: Its residents and relatives

Mansfield Park is the ancestral home of the Bertram family, and Sir Thomas Bertram is the worthy, aristocratic, and high-bred, albeit somewhat pompous and formal, owner of the property, which is a very good one. He has two sons, Tom and Edmund, and two daughters, Maria and Julia.

Lady Bertram is “a woman of very tranquil feelings, and a temper remarkably easy and indolent.” She has two married sisters, Mrs. Norris and Mrs. Price. Mrs. Norris has married a clergyman, to whom Sir Thomas has given the family living of Mansfield, and, as she has a decided “spirit of activity,” no children, and nothing particular to do, she finds ample occupation in presiding over other people’s affairs, especially in the Bertram family.

Mrs. Price’s marriage has been unfortunate; she “married, in the common phrase, to disoblige her family, and, by fixing on a lieutenant of marines without education, fortune, or connections, did it very thoroughly.”

A breach takes place between her and her sisters in consequence; her home is many miles distant from theirs, and no communication is kept up, until, after struggling on for eleven years in poverty and difficulty, with a fast-increasing family, and an unemployed husband, she is compelled to apply to her sisters for help.

It is easy to guess after this what Mrs. Norris’s share of the undertaking will amount to, but Sir Thomas has not yet learned to see through his sister-in-law, and the arrangement is carried out as she has planned it, and in the full belief that she will take her fair share in it.

Fanny Price comes to live at Mansfield Park

Fanny Price is accordingly sent for; and Miss Austen has painted nothing more true than the sufferings of a sensitive, timid child suddenly removed from the home, and plunged into a thoroughly uncongenial atmosphere.

No one is unkind to her, but no one understands or shares her feelings; she has no companion among her cousins, and the elders, seeing her quiet and obedient, have no idea of all that she silently suffers.

Tom and Edmund Bertram, at sixteen and seventeen, are quite out of their little cousin’s reach, and Maria and Julia Bertram, having always been well taught, and accustomed to thinking much of their own attainments, are full of contempt for a cousin only two years younger than themselves, but far less well-informed.

Finding a friend in Edmund Bertram

Edmund Bertram is the only one in his family in whom Fanny finds a kind friend. He has all his father’s sterling qualities, with much more gentleness and tenderness than Sir Thomas ever shows, and, having surprised Fanny in tears one day, he finds out by degrees how readily she responds to any kindness, and how easily she can be made happy by it.

He devotes his leisure time to comforting her under the painful sense of her own deficiencies and bringing her forward as much as possible, for he has discovered that she is very timid and retiring, but has plenty of ability, and is far more intellectual in her tastes than his accomplished sisters.

He interests himself in her pursuits, devises little pleasures for her, directs her taste in readings, and as a reward for the affection and care he bestows upon her through the next five or six years, he makes her by degrees a very lovable and charming companion — far more like a sister to him than the highly accomplished Maria or Julia ever can be.

Edmund Bertram himself is an excellent specimen of a cultivated, thoughtful, right-minded young Englishman, not brilliant, but with plenty of sense, thoroughly good, and trustworthy.

Jane Austen once said of him that he was very far from being what she knew an English gentleman often was; but it is difficult for us to take this view of him, and, indeed, the only weak point in him is his clerical position, which, we must remember, was looked upon very different then from now.

. . . . . . . . .

Jane Austen Postage Stamps

. . . . . . . . .

When Fanny is fifteen, Mr. Norris dies; and Sir Thomas naturally supposes that Mrs. Norris will now take the opportunity of installing Fanny in her home.

Fanny is therefore left at Mansfield Park, much to her own thankfulness, as well as Mrs. Norris’s; and her position there as a constant companion to her aunt becomes well defined. Lady Bertram cannot do without someone at hand to help and advise her continually.

The Miss Bertrams do not care for the society of their mother, who has never interested herself in any of their pursuits; and, therefore, while they enter into all the society of the county under Mrs. Norris’s chaperonage, Fanny spends her hours quietly at home, delighted to be unnoticed and of use.

Just as his children are all grown up, Sir Thomas Bertram is obliged to go to the West Indies to see about some of his property there; a voyage which, of course, entails an absence of several months, and he is sincerely grieved at having to go, but, unfortunately, his absence is rather a relief than otherwise to his children.

With all his warm affection for them, he has never been able to win any of their hearts, except, perhaps, Edmund’s. The others feel real relief at his departure, all the more as some new acquaintances have lately appeared, with whom they can now be on terms of unrestrained intimacy.

Enter Henry and Mary Crawford

Henry and Mary Crawford are excellent pictures of the brilliant, worldly, amusing, clever young people, who are such well-known features of London society, but to the Bertrams, they are a novelty; and, as Mary Crawford has twenty thousand pounds, and is quite ready to be fallen in love with by Sir Thomas’s eldest son.

Julia Bertram is equally ready to make a conquest of Henry Crawford, matters seem likely to go on very comfortably. Unluckily everything does not quite fit in as it should. Maria Bertram, the eldest daughter, is already engaged to Mr. Rushworth — wealthy, well-born, and very dull, for whom she does not care in the least.

Maria, as she is the most handsome of the two sisters, it amuses Henry Crawford to carry on a flirtation with both, so that neither can say which is preferred; and Mr. Rushworth is kept in a continual state of irritation, while nothing is said or done that could give tangible grounds for jealousy.

Meanwhile, Tom Bertram, who is a mere man of pleasure, does not seem especially bewitched by Mary Crawford, and she, on her side, is unaccountably attracted by Edmund Bertram.

Mary has done her best to get rid of whatever heart she had to start with, but she has not wholly succeeded, and now, in spite of his being a younger son, and destined for Holy Orders, and of his not being nearly so polished or complimentary as the men she is accustomed to, his straightforwardness, high principle, and simple admiration for her fascinate the hardened coquette, and she is on the verge of caring for him as much as she is capable of caring for anyone.

The attraction is quite as great on Edmund’s side, and this is less wonderful, as Mary Crawford is beautiful, clever, and amusing; his taste cannot always approve of her, but he sets down much that pains him to the account of the society in which she has lived, and the sincere affection between her and her brother makes him believe her capable of real feeling.

Feelings begin to grow for Edmund