Nava Atlas's Blog, page 22

December 18, 2022

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1911)

Though Frances Hodgson Burnett (1849 – 1924) wrote more than forty novels, The Secret Garden (1911) remains one of her most enduring works, along with A Little Princess (1905).

Burnett was a poet and playwright in addition to her prolific output of novels and short stories for adults and children. Quite successful professionally, she had a difficult, sometimes tragic life.

The Secret Garden was published in 1911 after an original version was first serialized in The American Magazine in 1910. The story follows the journey of Mary Lennox, a sickly and unloved ten-year-old girl born to wealthy British parents in India.

After a cholera epidemic kills her parents, Mary is sent to England to live with her Uncle Archibald in an isolated, mysterious house. The tale follows the spoiled and sulky young girl as she slowly sheds her sour demeanor after discovering a secret, locked garden on the grounds of her uncle’s manor.

Mary befriends Dickon, one of the servant’s brother, a free spirit who was able to communicate with animals, and Colin, her uncle’s son, a neglected invalid. The Secret Garden has remained a timeless classic for its themes of friendship and the power of nature to heal the body and spirit.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett

. . . . . . . . .

An original 1911 review of The Secret GardenFrom the original review of The Secret Garden in The Times Dispatch, Richmond, VA, October 29, 1911:

Readers of all the many charming books that Frances Hodgson Burnett has written to delight the world and make it better will find The Secret Garden full of sweet and unexpected pleasures.

It’s a portrayal of the joyous laughter of childhood, the scents and sounds of fragrant growing things, and the bloom of roses, and the magic that heals and comforts and makes the weak and sick strong.

The titled garden was secret because the door to it had been locked and the key buried — along with its secrets. A long time before the book’s story began, the lady of the manor — a wife and mother — bent above its borders and tended its flowers. But because her life ended tragically early, it was barred, and the flowers were left untended and forsaken.

Introducing the contrary Mary Lennox

After years had passed, a little girl named Mary Lennox, whose parents had died in India from cholera, cat to Misselthwaite Manor in Yorkshire, England, the place were the secret garden stood.

Archibald Craven, the owner of the manor, was Mary’s uncle. She was a thin, sallow child, with thin light hair and a sour expression. She had never enjoyed any affection from her thoughtless, carefree young mother, and became a disagreeable child even before the untimely death of her parents.

Before Mary came to Misselthwaite Manor, she had had none of the amusements of a healthy childhood.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Discovering the secret garden and meeting Dickon

Soon after coming under the care of her uncle, Mary discovered the secret garden. She picked up the key, pushed aside an overhanging curtain of ivy, and went inside the ancient walls.

Once she had been working in the garden for a tie, her little peaked face began to grow round and rosy.

Mary found a playmate, a boy named Dickon, who was a brother of the housemaid. Dickon was the son of a kind, motherly woman named Susan Sowerby and was versed in all the nature lore of the Yorkshire moors.

Dickon had made friends with many of the wild things and taught Mary a great deal about the ways of birds and squirrels and lambs. He taught her how to plant and tend flowers, too.

. . . . . . . . . .

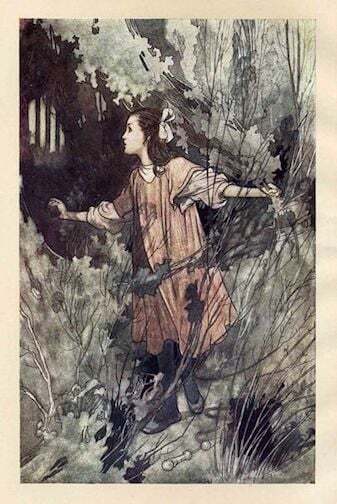

Charles Robinson illustration from The Secret Garden, 1911 edition

. . . . . . . . . .

Everyone finds their own contentment

Mary had begun to feel the good effects of her changed surroundings, thriving and growing in a natural, healthy way. Then, she happened upon her cousin Colin Craven, who was the son of her Uncle Archibald. An invalid, he was over-doctored, over-nursed, and over-indulged.

Colin was brought to the point of believing that he couldn’t walk, run, or participate in any of the games that children love. Instead, he had a highly developed set of nerves and an undeveloped spine due to lack of exercise and fresh air.

As to what the garden did for these two unhappy children, Mary and Colin, readers of the book will discover. Perhaps it did more for Colin’s father than for anyone else.

But it might not have done so much had it not been for Dickon and Susan Sowerby and the encouragement they gave in making the weak grow strong, and the unhappy to find contentment.

The Secret Garden will have a place in the affections of the world along with Little Lord Fauntleroy and A Little Princess.

More about The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett An analysis of a classic children’s book Full text on Project Gutenberg Audio recording on Librivox Various film adaptations listed on IMDBThe post The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1911) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 6, 2022

On Rereading A Wrinkle in Time: A Fifty-Year View

I gave myself the best holiday present ever: rereading A Wrinkle in Time by our new Christmas tree. Rereading Madeleine L’Engle’s masterpiece was like visiting my oldest and dearest friend.

A Wrinkle in Time is the book that ignited my reading obsession more than fifty years ago, and for that, I’m forever grateful.

I first experienced A Wrinkle in Time as it was read aloud by my fourth-grade teacher, Ms. Lloyd, at Overland Avenue elementary school. The book had received the Newbery Medal a few years earlier and captured the attention of thousands of elementary school librarians and teachers.

Ms. Lloyd must have been one of those teachers who welcomed the innovation of the outcast characters traveling in space — her rendition of A Wrinkle in Time was delightful and enthusiastic: after I listened to my teacher, I knew I had to reread the book on my own.

A Wrinkle in Time as constant companion

I wasn’t satisfied after Ms. Lloyd had finished reading A Wrinkle in Time nor did I want to return the book to the library. I needed A Wrinkle in Time to be my own to satisfy my own reading needs.

For $3.25 I bought my first book, the beautiful first edition of A Wrinkle in Time. The book had lime green tinted pages at the top, with the golden Newbery Medal seal on the blue cover that depicted Meg, Calvin, and Charles Wallace trapped in their own bright green concentric circles.

My first book became my first accessory. A Wrinkle in Time was always alongside my fifth- and sixth-grade homework papers. My dirty thumbprints were imprinted on the clean white back cover from playing basketball: this book accompanied me everywhere for the next few years.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle

. . . . . . . . . .

I was never a science fiction or fantasy enthusiast; I simply believed that everything in A Wrinkle in Time had the potential of being possible and real.

What compelled me about the story then, as it does now, is the thrilling adventure of being hurtled through space to find Meg and Charles Wallace’s missing father, hidden on the planet Camazotz.

Will the children and their dear friend Calvin O’Keefe find Mr. Murry before it’s too late to return to earth? Or, will they be consumed by the CENTRAL Central Intelligence Unit and their minds absorbed by the evil IT?

Such a thing as intergalactic travel was possible: all one had to do was master the art of “tessering” and become acquainted with Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which. Simply because most of us had not had this opportunity didn’t rule out that such a journey could be achieved.

The character of the always-impatient, slightly angry Meg Murry juxtaposed against the steadying calmness of her friend Calvin O’Keefe that had me turning the page. Everyone always loved the preternaturally brilliant and charming youngest Murry, Charles Wallace.

The prescient metaphors of Camazotz

What captured my attention in this latest reading was the planet Camazotz and its residents who were quite happy to substitute freedom for security: L’Engle created a prescient environment of blind submission to an evil authority.

The danger of Camazotz is with us today; not long ago, there was an American president who told us not to believe anything unless he says it; anything else; according to him, is fake news. And there were plenty of people who agreed with forfeiting one’s freedom in exchange for the illusion of comfort.

. . . . . . . . . .

Madeleine L’Engle’s Long Years of Literary Rejection

. . . . . . . . . .

The challenges of parenting are universal

My recent reading of Wrinkle offered another personal revelation: how parents unknowingly (and almost certainly) disappoint their children. Meg was angry that upon the rescue of their father, he couldn’t immediately solve their current crisis: rescuing Charles Wallace from the evil IT and safely returning to earth.

After a few bouts of meanness and insolence towards her father, Meg recognized that her unrealistic expectations — to make everything correct again and to do so immediately — weren’t possible. She apologized.

Meg confessed to him, “I wanted you to do it all for me. I wanted everything to be all easy and simple … So I tried to pretend that it was all your fault … because I was scared, and I didn’t want to do anything myself.”

“But I wanted to do it for you,” Mr. Murry said. “That’s what every parent wants.”

Little did I know, over fifty years ago, that A Wrinkle in Time would bring me solace and insight into parenthood. Madeleine L’Engle’s brilliance never ceases to amaze me.

The last four pages of the book were particularly affecting. I had tears falling freely down my face — the same yet not the same tears spilled over fifty years ago — when Meg attempts to rescue Charles Wallace from the evil IT.

“Charles, I love you. Come back to me, Charles Wallace, come away from IT, come back, come home. Charles Wallace, you are my darling and my dear and the light of my life and the treasure of my heart.”

And thus, Charles Wallace is freed from IT, and he, Meg, Calvin, and their beloved father find themselves back on earth. The best part of a safe and happy childhood is the unconditional, pure love given to a child by their parent. Such love has the possibility to change everything that may plague you.

. . . . . . . . . .

Can a Wrinkle in Time Ever Be Successfully Filmed?

. . . . . . . . . .

From my first reading decades ago to my most recent rereading, I have seen myself as Meg. I have stayed angry at the social and economic injustices that permeate our world, perceiving my anger as a necessary element to challenge and overcome such injustice.

Meg Murry is an incredible character. However, I also admire the skills of Calvin O’Keefe as a great communicator and an incredibly calm person. I also aspire to the great intelligence of Charles Wallace, but remember the warnings of Mrs. Whatsit.

Charles’ magnificent mind may be accompanied by arrogance and pride, something we need to check ourselves of when we’re convinced our intelligence is infallible.

There was a great deal of anticipation for the 2018 film adaptation of A Wrinkle in Time. But despite its stellar cast and director, the movie failed to capture the essence of the book. I heard that there is another film, this time a musical, being developed, to which I respond, why bother? Read the book. The book is always better.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Nancy Snyder. Nancy Snyder retired from the City and County of San Francisco and as a union officer for SEIU Local 1021/790. She writes about books and women writers to understand the world and her place in it.

The post On Rereading A Wrinkle in Time: A Fifty-Year View appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 30, 2022

The Life and Letters of Madame de Sévigné

Who was Madame de Sévigné (1626 – 1696) and why are we still reading her collected letters more than three hundred years later? She lived in complicated times— during the reign of Louis XIV — and she was a gifted chronicler.

To this day, 1,372 of her letters survive, mostly written to her beloved daughter, Françoise-Marguerite de Sévigné.

Thanks to this correspondence, we have detailed insight into French history, politics, and culture, not to mention gossip — about the King’s love life, the Rennes tax revolt, or details of the corruption trial of finance minister Nicolas Fouquet.

Madame de Sévigné writes about the events of her life with flair, faith (she was a good Catholic), and spice. The true events of her life would make a juicy novel.

Early life and education

Born Marie de Rabutin Chantal in Paris at the Place des Vosges, her father was from an aristocratic Burgundian family, and her mother from the noble Coulanges. While still young, her father was killed in a battle against the English on the Ile de Rhe and her mother died a few years later.

After the death of her grandparents, at the age of ten, the young orphan was sent to live with her uncle Christophe de Coulanges, the Abbe of Livry. This proved fortuitous.

She was served well by her guardian; de Coulanges offered a good home, guarded her fortune, and made sure she was well-schooled in Christian values, Italian, Spanish, and Latin. Such an education was uncommon for women of the time.

Building on this solid foundation, young Marie studied philosophy, history, religion, and literature, including the works of Rabelais, Pascal, and La Fontaine.

An unhappy marriage and early widowhood

In 1644, at the age of eighteen, Marie was married off to Henri, Marquis de Sévigné, scion of a respected Breton family, as his third wife. Now, as Madame de Sévigné, she settled down to marital bliss and the raising of children. However, the bliss was short-lived — the Marquis was a gambler, spendthrift, and adulterer.

Seven years into the marriage, he was killed in a duel fought over his mistress, a prostitute named La Belle Lolo. At the age of twenty-five, the widow was left with two young children, a daughter named Francoise-Marguerite and a son named Charles.

In summing up her loveless and only marriage, de Sévigné wrote, “Matrimony is a very dangerous disorder; I had rather drink.”

Madame de Sévigné’s iconic correspondence begins

The correspondence for which she became famous started when her daughter, Françoise-Marguerite, moved to Provence with her husband Comte de Grignan, where he could serve as viceroy.

The separation from her daughter was shattering. Seeking solace, Madame de Sévigné often wrote to Françoise-Marguerite three times a week, twenty to thirty pages a day. The tone of the letters may seem hurried as she covered a lot of topics in each; however, she had to make the post on Wednesdays and Fridays.

The letters, covering some fifty years, were written either from her home in Paris (now the Musee Carnavalet), her estates in Burgundy and Provence, the homes of relatives and friends, or Versailles.

“My dear girl, don’t stop loving me, for love is my life and soul; as I said to you the other day, it makes all my joy and all my grief. I declare that the rest of my life is overshadowed by gloom and sadness when I think that so often I shall spend it away from you.”

At the time, letters were meant to be read aloud, and narrators could leave out anything personal about family and friends. Madame de Sévigné often parodies Corneille and Moliere in her writing, and she makes many historical and literary references throughout.

In letters to her daughter Francoise-Marguerite, Madame de Grignan, she alternated between offering loving advice on childrearing and health, and nagging her about how she and Comte Grignan spent and gambled too much (de Sévigné was always having to bail them out financially).

Similarly, in letters to her son Charles she offered kind, encouraging words when she wasn’t lecturing him on his unbecoming appetite for actresses and partying. In her correspondence, she gossiped about scandals at the Court, report on political events, or complain tediously about aches, pains, and loneliness.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Observations on Madame de Sévigné’s correspondenceMadame de Sévigné’s correspondence has been described as important and influential as that of Voltaire. Authors such as Elizabeth Gaskell, George Eliot, and Virginia Woolf considered her a model for future women writers.

It has been a joy to read these epistles, especially those in the Penguin Classics collection, Madame de Sevigne, Selected Letters, for which Professor Leonard Tancock translated and published fifty complete letters with excellent notes for historical context. This book presents many letters to her daughter as well as those to or from her son Charles (with whom she wasn’t as obsessed) and her cousin Roger de Rabutin, among others.

Readers can appreciate the colorful bon mots and turns of phrase: “Take chocolate so that the most unpleasant company seems good to you.” “I always think people can read my thoughts through my bodice.” “It is freezing fit to split a stone.”

It’s no wonder that Madame de Sévigné became a popular figure at Versailles as well as in Parisian salon society, and that her letters have become treasured literary gems.

The letters are not only observant and witty, but they’re written with lots of puns and epigrams. Moreover, she is considered a forerunner to the romantics, portraying the world of Mother Nature — its peace and spirituality. In one letter, she describes trees as being “decked in pearls and crystal.” In another letter:

“These woods are always beautiful; their greenness is a hundred times more beautiful than that of Livry. I do not know whether it is due to the quality of the trees or to the freshness of the rains, but there can be no comparison. Everything today has the same green it had during the month of May. The leaves which fall are dead but those holding on are still green. You have never gazed at such beauty.”

Despite the span of time between Madame de Sévigné’s and my own life, I can empathize with many of the emotions in her letters, particularly when she writes as a mother who misses her daughter (as I do mine).

I also appreciate her love and kindness as a grandmother and friend. De Sévigné was a genius in the art of friendship and counted respected wordsmiths Francois de La Rochefoucauld and Madame de La Fayette as among her closest friends.

As the late author Francine du Plessix Gray wrote in a review of Frances Mossiker’s biography, Madame de Sevigne, A Life and Letters, the correspondence reveals:

“… A woman whose need for solitude creates a constant tension with her love of society, a devout Catholic whose Jansenist brand of faith tends to austere pessimism, a bonne vivante whose conversation leans toward the bold and racy, a narcissistic coquette addicted to spa cures and dietary fads to maintain her figure, a flirtatious tease who enjoys men’s attention and yet is reported to be frigid.”

Modern-day critics are often harsh, judging Madame de Sévigné’s thoughts and attitudes by contemporary mores. Given the brutal times of torture and war that spanned her life, more context is needed.

When King Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes to deprive all Protestants of liberty unless they converted to Catholicism, she approved of their persecution and exile insofar as she considered them traitors. More than two hundred thousand Huguenots fled France during this period.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Preservation and destruction of Madame’s lettersHow did so many of her letters survive? Madame de Sevigne’s cousin Rabutin published many of them in a memoir he wrote just following her death. Over time, others published her correspondence, sometimes edited.

The biggest blow to historical preservation was when Madame de Simiane (daughter of Françoise-Marguerite, and granddaughter of de Sévigné) printed her grandmother’s letters and reportedly burned most of her mother’s responses. Evidently, de Simiane was troubled by her mother’s unorthodox Cartesian views espoused by René Descartes, the controversial rationalist.

“You ask me, my dear child, whether I am still fond of life. I admit that I think it has some acute sorrows. But I am even more repelled by death, and I feel that I am so unfortunate to have to finish all this by death, and that if I could go backwards I would ask for nothing better.”

Madame de Sévigné died of smallpox at her daughter’s chateau on April 17, 1696. Her daughter, fearing the disease, was not at her deathbed, the sad irony being that she died nine years later from smallpox as well.

Further reading and sources

The Sun King: Louis XIV at Versailles by Nancy Mitford (1966)King of the World, The Life of Louis XIV by Philip Mansel (2019) Britannica Madame de Sevigne, Selected Letters, with an introduction by Leonard Tancock (1982) Quotes by Madame de SévignéContributed by Tyler Scott, who has been writing essays and articles since the early 1980s for various magazines and newspapers. In 2014 she published her novel The Excellent Advice of a Few Famous Painters. She lives in Blackstone, Virginia where she and her husband renovated a Queen Anne Revival house and enjoy small town life.

More by Tyler Scott on this site:

A Tribute to Claudia Emerson, Poet and Friend Anita Brookner, Author of Hotel du LacThe post The Life and Letters of Madame de Sévigné appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 25, 2022

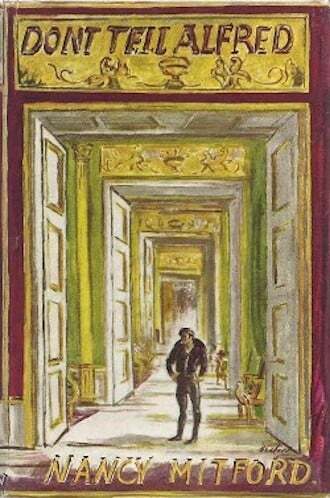

Don’t Tell Alfred By Nancy Mitford (1960)

Don’t Tell Alfred (1960) was the last novel by British author Nancy Mitford (1904 –1973) and the final installment of the loose trilogy encompassing The Pursuit of Love (1945) and Love in a Cold Climate (1949).

Like the two previous novels, Don’t Tell Alfred is narrated by Frances (“Fanny”) Wincham. It takes place some twenty years after the previous two (whose timelines were more or less concurrent) and focuses on the narrator herself.

The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate are told from her perspective but have different main characters, both of whom are cousins of Fanny.

And like most of Mitford’s other novels, Don’t Tell Alfred gently satirizes the mores and manners of the British upper classes.

As the novel begins, Fanny is middle aged with two teenage sons. Alfred, her stable, staid husband is still an Oxford don, but has suddenly been appointed as the British ambassador to France. The family moves to Paris, and from there, various complications ensue.

. . . . . . . . .

See also: The Pursuit of Love by Nancy Mitford

. . . . . . . . .

A brief description of Don’t Tell AlfredFrom the publisher of the 2010 edition (Vintage books): In this delightful comedy, Fanny—the quietly observant narrator of Nancy Mitford’s two most famous novels—finally takes center stage.

Fanny Wincham—last seen as a young woman in The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate—has lived contentedly for years as housewife to an absent-minded Oxford don, Alfred. But her life changes overnight when her beloved Alfred is appointed English Ambassador to Paris.

Soon she finds herself mixing with royalty and Rothschilds while battling her hysterical predecessor, Lady Leone, who refuses to leave the premises.

When Fanny’s tender-hearted secretary begins filling the embassy with rescued animals and her teenage sons run away from Eton and show up with a rock star in tow, things get entirely out of hand. Gleefully sending up the antics of mid-century high society, Don’t Tell Alfred is classic Mitford.

. . . . . . . . .

See also: Love in a Cold Climate by Nancy Mitford

. . . . . . . . .

A 1960 review of Don’t Tell AlfredFrom the original review by Harriet Hill in The Gazette, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, December 10, 1960: Like snails, Nancy Mitford is a cultivated taste. Once a reader has acquired the taste. almost anything that comes from her pen proves edible. Sometimes she drips acid, at others, honey.

In her latest she moves in ambassadorial circles. (She frequented them in Paris for a good many years and now maybe she feels safe in paying off a few old scores.) Somebody once said, “You can tell a person almost anything if you smile when you say it.”

Nancy Mitford smiles blandly when pinpointing her attack on the foibles of the upper crust. Her Majesty’s Government pitched Fanny Wincham’s husband, Alfred, from the bucolic simplicity of Oxford into the UK Embassy in Paris.

Fanny embarks on her new wifely career in the world’s most chic capital with misgivings, ranging from her lack of smartness to absence of mental swiftness.

From then on, the Winchams take hold of problems ambassadorial and sons who keep appearing and converting the embassy into as outlandish a “home from home” as any reader would wish.

Fanny, a permissive parent in her own view (and certainly she could be called that in the view of others) has to put up with a son who starts to make quick money escorting elderly English people to the Costa Brava, another who is a Zen Buddhist and appears at the embassy complete with new wife and Chinese baby (not theirs) and two young teenagers who take French leave from Eton.

The other young problem — beautiful Northey who comes to Paris as Lady Wincham’s secretary and from then on has a string of elderly French parliamentarians to contend with as well as such unlikely pets as a rescued badger in the Embassy garden.

The Winchams move from crisis to crisis, public and private, in hilarious succession. The duel between the generations is as funny as anything in modern writing. If at times the nonsense threatens to become top heavy. remember this is Nancy Mitford and nobody else moves in her highly specialized groove as well.

. . . . . . . . . .

Original cover of the 1960 edition

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Don’t Tell Alfred by Nancy Mitford

Review by Evelyn Waugh in London Magazine Review in Kirkus Reviews Reader discussion on GoodreadsThe post Don’t Tell Alfred By Nancy Mitford (1960) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 23, 2022

Love in a Cold Climate by Nancy Mitford (1949)

Love in a Cold Climate (1949) was the follow-up novel to The Pursuit of Love (1945) by British novelist, biographer, and journalist Nancy Mitford (1904 – 1973). Not a sequel but a companion volume of sorts to its predecessor, like Mitford’s other novels, it satirized upper-class life in England.

The Pursuit of Love was Mitford’s fifth novel but her first breakaway success, selling two hundred thousand copies within the first year. It set the stage for Love in a Cold Climate, which proved to be equally successful.

The two novels established Mitford as a bestselling author, and both have both been reprinted and adapted for television multiple times, among others the miniseries Love in a Cold Climate (2001) and The Pursuit of Love (2021).

Though published a few years later, Love in a Cold Climate isn’t considered a sequel of The Pursuit of Love, due to its fairly concurrent timeframe. Frances “Fanny” Wincham is the narrator of both. She is the cousin and close friend of Linda, the protagonist of The Pursuit of Love, and a distant cousin of Polly, the main character of Love in a Cold Climate.

Fanny appears once again in Don’t Tell Alfred (1960), which focuses more on herself and her marriage. Together, the three books form a loose trilogy.

A brief synopsis of Love in a Cold Climate

From the 2010 Vintage books edition (2010):

“A sparkling romantic comedy that vividly evokes the lost glamour of aristocratic life in England between the wars.

Polly Hampton has long been prepared for the perfect marriage by her mother, the fearsome and ambitious Lady Montdore. But Polly, with her stunning good looks and impeccable connections, is bored by the monotony of her glittering debut season in London.

Having just come from India, where her father served as Viceroy, she claims to have hoped that society in a colder climate would be less obsessed with love affairs.

The apparently aloof and indifferent Polly has a long-held secret, however, one that leads to the shattering of her mother’s dreams and her own disinheritance.

When an elderly duke begins pursuing the disgraced Polly and a callow potential heir curries favor with her parents, nothing goes as expected, but in the end all find happiness in their own unconventional ways.”

. . . . . . . . .

See also: The Pursuit of Love by Nancy Mitford

. . . . . . . . .

In the teeth of grim headlines about economic collapse and further austerities … Nancy Mitford’s characters, desperately happy and utterly conscienceless, inhabit that cloud land of eight-course dinners, enormous balls, countless servants, and nonstop weekends that the English country gentry hold sacred.

Love is the only social problem that looms on the horizon of Hampton, where Polly Hampton, heiress of a very rich and grand old family has reached the marriageable age and to the horror of her mother, Lady Mountdore, a tremendous snob, shows no interest in men.

Polly confides to her friend, Fanny Logan, who tells the story, that she had noticed in India, where her father was viceroy, a great preoccupation with love affairs, but she had thought perhaps in a cold climate … She is, of course, utterly wrong.

Polly, beautiful as the morning and bright as an English mist, unaccountably fixes her choice on her newly widowed uncle, Boy Dougdale, an aging and lecherous lecturer whose custom it is to dispense “great sexy pinches” among the girls of the countryside.

Polly’s marriage leaves a frightful gloom at Hampton, which is dispelled, for Lady Mountdore at least, by the arrival of a family heir from Nova Scotia, a “dragonfly of a man” who subscribes to Vogue, decks himself in jewels, and induces Lady Mountdore to paint, powder, reduce, and wear terribly smart clothes.

Fanny, the storyteller, is in to way taken back by these strange proceedings. She is well conditioned to eccentricity. Here mother was called “the Bolter” for her habit of leaving husbands and lovers.

Her Uncle Matthew writes the names of his enemies (“sewers,” he calls them) on pieces of paper which he puts in drawers in the hope it will bring on their deaths within a year.

Miss Mitford’s account of decadent diversions with with wicked repartee is marked by a charmingly witty and literate style. Love in a Cold Climate is amusing, if slightly anachronistic. But English readers evidently welcome the escape into an unchanged world where there is no message and little meaning.

. . . . . . . . .

1980 BBC miniseries adaptation

. . . . . . . . .

“Remember that love cannot last; it never, never does; but if you marry all this it’s for your life. One day, don’t forget, you’ll be middle-aged and think what that must be like for a woman who can’t have, say, a pair of diamond earrings. A woman of my age needs diamonds near her face, to give a sparkle.”

. . . . . . . . .

“And I might offer you a little advice, Fanny, it would be to read fewer books, dear, and make your house slightly more comfortable. That is what a man appreciates in the long run.”

. . . . . . . . .

“She had all the sentimentality of her generation, and this sentimentality, growing like a green moss over her spirit, helped to conceal its texture of stone, if not from others, at any rate from herself. She was convinced that she was a woman of profound sensibility.”

. . . . . . . . .

“But beauty is more, after all, than bones, for, while bones belong to death and endure after decay, beauty is a living thing.”

. . . . . . . . .

“There was a movement among the women. They turned their heads like dogs who think they hear somebody unwrapping a piece of chocolate.”

. . . . . . . . .

“They were respected by their neighbours for their conformity to the fashion of the day, for their morals, for their wealth, and for their excellence at all kinds of sport.”

. . . . . . . . .

“I tried to cheer her up by telling her, what, in fact, proved to be the case, that in a very short time the fields would be covered with sheep, the trees with birds, and the barrows with fruit just as usual. But though the future did not disturb me I found the present most disagreeable, that winter should set in again so late in the spring, at a time when it would not be unreasonable to expect delicious weather, almost summer-like, warm enough to sit out of doors for an hour or two.”

. . . . . . . . .

More about Love in a Cold Climate Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads Still Sparkling, Despite its Age (The Guardian) Kirkus ReviewsThe post Love in a Cold Climate by Nancy Mitford (1949) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 17, 2022

The Pursuit of Love by Nancy Mitford (1945)

The Pursuit of Love (1945) was British author Nancy Mitford’s fifth novel, and her first breakout success. The first of what was to become a trilogy, it was followed by Love in a Cold Climate (1949; arguably the best known of her many works) and Don’t Tell Alfred (1960).

The Pursuit of Love sold two hundred thousand copies within the first year, making Nancy Mitford financially independent for the first time in her life.

Adapted as a television miniseries in 2021, The Pursuit of Love marked the directorial debut of Emily Mortimer (who also had the role of Fanny’s mother, “the Bolter”). This well-received three-part series revitalized interest in Mitford’s work, much as earlier adaptations of Love in a Cold Climate had done.

The 2010 Alfred A. Knopf edition of The Pursuit of Love summed it up as follows:

“ … A classic comedy about growing up and falling in love among the privileged and eccentric.

Mitford modeled her characters on her own famously unconventional family. We are introduced to the Radletts through the eyes of their cousin Fanny, who stays with them at Alconleigh, their Gloucestershire estate.

Uncle Matthew is the blustering patriarch, known to hunt his children when foxes are scarce; Aunt Sadie is the vague but doting mother; and the seven Radlett children, despite the delights of their unusual childhood, are recklessly eager to grow up.

The first of three novels featuring these characters, The Pursuit of Love follows the travails of Linda, the most beautiful and wayward Radlett daughter, who falls first for a stuffy Tory politician, then an ardent Communist, and finally a French duke named Fabrice.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Nancy Mitford

. . . . . . . . . . .

From the original review in The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) by Elizabeth Norrie, April 20, 1946:

The Radlett women and their kin pursued love with as wholehearted abandon as ever a bloodhound tracked down his quarry. It was not always what they wanted when they got it, but this did not dishearten them. Philosophically, they paused for a second wind and then started off on the trail once more.

There was Fanny’s mother known as the “Bolter” because of her frequent excursions into and out of marriage and the other thing; there was Fanny herself, teller of the tale, for whom one venture was enough, because it was the right one.

There was Emily, the Bolter’s sister, who found what wanted in Davey, the hypochondriac; there was Louisa, who was inclined to suspect that she had been short-changed but who did nothing about it except bring children into the world; and there was Linda.

Fanny makes clear that this is really Linda’s tale with the rest of the family thrown in for background. Linda’s heart was so tender that she wept over the death of Fanny’s smelly pet mouse.

It was Linda also who carried her love of animals over into marriage and shocked her conventional German-English in-laws by producing a dormouse from her pocket whenever conversation became boring. Of course, this first marriage didn’t last long. which undoubtedly saved the in-laws from dying of apoplexy or shock.

The next venture, however, had its problems. As the successor to Tony, the solid citizen, Linda chose Christian, the Communist, who expected her to be able to do housework.

“How dreadful it is, cooking, I mean,” says Linda to Fanny. She continues:

“That oven—Christian puts things in and says, “Now you take it out in about half an hour.” I don’t dare him how terrified I am, and at the end of half an hour I summon up all my courage and open the oven and there is that awful hot blast hitting one in the face …

“Oh dear, and I wish you could have seen the Hoover running away with me, it suddenly took the bit between its teeth and made for the lift shaft. How I shrieked—Christian only just rescued me in time.

I think housework is far more tiring and frightening than hunting, no comparison, and yet after hunting, we had eggs for tea and were made to rest for hours, but after housework people expect one to go on just as if nothing special had happened …”

And so Christian faded out of the picture, giving the entrance cue to Fabrice. With Fabrice, Linda embarked on a series of highly improbable adventures.

When the call came for the sweet-tempered, gentle Linda herself to make an exit, she left in such a state of happiness that Fanny was prompted to say to the Bolter: “I think she would have been happy with Fabrice. He was the great love of her life, you know.”

But the Bolter. from the depth of her experience said sadly, “Oh, dulling, one always thinks that. Every, every time”

The Pursuit of Love is built upon tragedy, but Nancy Mitford has chosen to paint the canvas with the glowing colors of comedy. The result is irresistibly charming.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Pursuit of Love (2021 miniseries)

official trailer

. . . . . . . . . .

“The great advantage of living in a large family is that early lesson of life’s essential unfairness.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I have often noticed that when women look at themselves in every reflection, and take furtive peeps into their looking-glasses, it is hardly ever, as is generally supposed, from vanity, but much more often from a feeling that all is not quite as it should be.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Even if I take him out for three hours every day, and go and chat to him for another hour, that leaves twenty hours for him all alone with nothing to do. Oh, why can’t dogs read?”

. . . . . . . . . .

“… Always either on a peak of happiness or drowning in black waters of despair they loved or they loathed, they lived in a world of superlatives.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Left-wing people are always sad because they mind dreadfully about their causes, and the causes are always going so badly.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“One’s emotions are intensified in Paris—one can be more happy and also more unhappy here than in any other place. But it is always a positive source of joy to live here, and there is nobody so miserable as a Parisian in exile from his town.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The really important thing, if a marriage is to go well, without much love, is very very great niceness—gentillesse—and very good manners.”

The post The Pursuit of Love by Nancy Mitford (1945) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 16, 2022

Nancy Mitford, author of Love in a Cold Climate

Nancy Mitford (November 28, 1904 – June 30, 1973) was a British novelist, journalist, and biographer. She was best known for her novels depicting upper-class life in England, often with satirical and provocative humor.

She also wrote historical biographies, magazine articles, and essays.

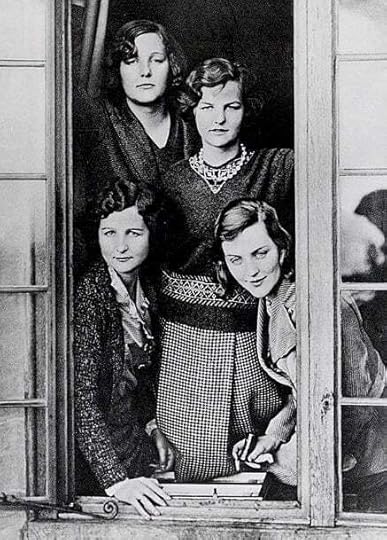

Nancy was the eldest of the six Mitford sisters, most of whom courted controversy in one way or another, and was considered one of the “Bright Young Things” on the London scene of the 1920s and 1930s.

Early lifeNancy Mitford was born in London in 1904. Her father, David Bertram Ogilvy Freeman-Mitford, the second Baron Redesdale, worked at The Lady magazine. In 1914, he and his wife, Sydney Bowles, moved their growing family to Asthall Manor near Swinbrook in Oxfordshire.

Nancy would eventually have five sisters — Pamela, Diana, Unity, Jessica, and Deborah — and one brother, Tom. He was largely overshadowed by his sister’s exploits and would later be killed in action in Burma in 1945.

Nancy and her siblings had an eccentric childhood, which revolved around the somewhat arbitrary rules their mother imposed on them: they were banned from eating certain foods; they had to be rinsed in cold water after their baths; windows were to be left open all year round, no medicines of any kind were allowed.

They were educated at home by governesses, leading Nancy to later joke that she “grew up ignorant as an owl,” and from the time her sister Pamela was born (when Nancy was three), sibling rivalries and jealousies dominated.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Mitford family in 1928. Nancy is in the back, left.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . . .

Nancy’s own brand of teasing humor formed the insular vocabulary that has since become known as “Mitfordian,” which included elaborate nicknames for the family and their friends. The index of nicknames in Charlotte Mosley’s The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters is incomplete, but is still two pages long.

Their mother and father were known as Marv and Farv, Diana was Bodley (because of her supposedly large skull, taken from the name of the publisher Bodley Head), Jessica was Decca, Unity was Bobo and Heart of Stone, Deborah was Debo, Nine, or Stubby, and Pamela was known simply as Woman.

Nancy, known as Koko, was known among her sisters for being honest, loyal, witty, and cunning, sometimes to the point of being cruel. Jessica once described her as “sharp-tongued and sarcastic,” and remembered that Nancy had once told her she looked like “the eldest and ugliest of the Brontë sisters.” Some of the worst insults were reserved for Deborah, and Nancy would often tell her that “everyone cried when you were born.”

As well as Farv, Nancy had her own nickname for her father: “Old Subhuman,” partly for his habit of eating calf brains for breakfast and partly for one of his favorite games called “child hunt.”

He would give Nancy and Pamela a head start to run across the fields near their manor house before he released the pack of bloodhounds. Whichever dog found a child first was rewarded with raw meat. She later used her father as the model for Uncle Matthew in The Pursuit of Love — a bad-tempered, eccentric, xenophobic bully.)

The “Bright Young Things” and first writings

Nancy’s eighteenth birthday in November of 1922 was marked by a grand “coming-out” ball, signifying her entrance into “Society.” In June 1923 she was presented as a debutante at Court. The following years were marked with round after round of social events, parties, and balls. Nancy mixed with the Bright Young Things of 1920s London and claimed that “we never saw the light of day, except at dawn.”

It was at this time that she met the writer Evelyn Waugh, who would remain a close friend. With his encouragement, she began writing to supplement the meager income allowed her by her father. Her first articles were largely unsigned contributions to society magazines until she was offered a regular column in The Lady in 1930.

Her first novel, Highland Fling, was published in 1931. A preview of what would become her typical style (a merciless satire of the upper classes, combined with an apparent fondness of prewar Britain and a humorous lightness of touch), it told the story of a house party at a grand, haunted castle. It made little impact, but this didn’t deter Nancy, who immediately started work on another, Christmas Pudding.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The wedding of Nancy Mitford and Peter Rodd, 1933

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . . .

Around the time that Nancy first began writing in earnest that she fell in love with James “Hamish” St Clair-Erskine, a homosexual who was introduced to her by her brother in 1928. They became unofficially engaged, despite criticism from family and friends, including Waugh who told her firmly to “dress better and catch a better man.”

Later Nancy admitted that she didn’t have “a single happy moment” with the narcissistic Erskine, and the affair ended abruptly in 1933 when he informed her that he intended to marry the daughter of a London banker.

Within a month of the breakup with Erskine, Nancy announced her engagement to Peter Rodd, known among her friends for being both clever and a horrendous bore (Nancy’s sisters dubbed him “The Old Toll-Gater,” referring to his habit of talking for hours on subjects such as medieval roads).

They were married in December 1933, but Rodd was a heavy drinker and compulsively unfaithful, draining Nancy of most of the small amounts of money she earned from magazines and her first four novels, none of which received much critical or public attention.

In 1941, after suffering repeated miscarriages, Nancy had a hysterectomy. She and Rodd separated after the war and were divorced in 1958.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Nancy (lower left), Diana, Unity, and Jessica Mitford, 1932

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . . .

The characters in Nancy’s novels were largely drawn from life. When her sister Jessica’s 1960 biography Hons and Rebels was published, Nancy wrote to Waugh complaining that the book drew more from her novels than from any actual memories of Jessica’s: “In some respects she has seen the family, quite without knowing it herself, through the eyes of my books.”

The Mitford family certainly gave her — and the newspapers — plenty of material. Pamela was known as “the boring one,” but it was relative to Jessica, who became a fervent Communist and journalist in America; Deborah, who became the Duchess of Devonshire; Diana, who left her first husband for the leader of the fascist party in Britain (Sir Oswald Mosley;) and Unity, who was a devoted fascist herself, and attempted suicide by shooting herself in the head when war was declared in 1939 (she failed, and spent the next few years brain damaged until her death in 1948).

Nancy, however, claimed to be largely indifferent to politics. She described her views as “vaguely socialist,” but according to biographer Lisa Hilton, “loathed people who were anti-Semitic and … anti-gay. She saw both as being deeply, deeply uncivilized.”

She volunteered in France to aid refugees from the Spanish Civil War and later helped Jewish refugees in London. Nancy called Diana’s husband Mosley “The Ogre” and refused to see her sister after she married him.

In case of any doubt, she made her feelings clear in her 1935 novel Wigs on the Green, a piercing satire of British fascism, as well as of Mosley, Diana, and Unity. Despite Diana’s pleas to remove some of the more critical parts of the book, Nancy refused.

Later, at the outbreak of war, she denounced her sister to the Home Office as “a ruthless and shrewd egotist, a devoted fascist and … an extremely dangerous person.” Diana was already considered a security threat, and after Nancy’s testimony was incarcerated in Holloway Prison for three years.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Pursuit of LoveDuring the World War II years, Nancy worked at Heywood Hill, a bookshop in Curzon Street, Mayfair. At the time, she was so hard up that she would often walk for an hour from her home in Maida Vale rather than take the bus.

She also volunteered as an ambulance driver, a canteen assistant, and a first aid worker, during which time one of her tasks was to write the names on the foreheads of the dead in indelible pencil.

However, she still found time to write, and finally found success in December 1945 with her fifth novel The Pursuit of Love. It sold two hundred thousand copies within the first year, and for the first time in her life, she became financially independent.

A 1948 sequel, Love in a Cold Climate, was equally successful. Together, the novels established Nancy Mitford as a bestselling author. Both have both been reprinted and adapted for television multiple times, among others the miniseries Love in a Cold Climate (2001) and The Pursuit of Love (2021).

A new start in Paris

In September 1942, Nancy met Colonel Gaston Palewski, General de Gaulle’s Chief of Staff and a Free French officer. Their affair continued through the war despite Palewski’s posting to Algeria in 1943. He became the love of her life, though her feelings were never fully reciprocated).

She moved with Palewski to Paris in 1946 and remained in France for the rest of her life. It was from this period onward that most of her letters to her sisters and friends in England were written — thousands of letters that form an important part of her literary legacy, perhaps equal to her books.

Paris not only marked a new start for Nancy’s personal life but gave her fresh impetus in her writing. It was here that she completed Love in a Cold Climate and her next novel, The Blessing (1951). The latter was praised by Waugh as “admirable, deliciously funny, consistent and complete, by far the best of your writings.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Nancy Mitford drawing by William Aston, 1938

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . . .

In the 1950s, Nancy turned her attention to historical biographies, in particular of French historical characters. Her first serious work in this vein was a biography of Madame de Pompadour, published to much critical acclaim in 1954. Her biography of Louis XIV, The Sun King, was an international bestseller.

In 1960, Nancy published another sequel to The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate, Don’t Tell Alfred.

She also wrote a regular column for the Sunday Times and was in demand as a journalist and reviewer. One article in particular, written for Encounter magazine as a deliberately teasing, provocative guide to the etiquette of language, proved so popular that it was later expanded into a book, Noblesse Oblige: An Enquiry into the Identifiable Characteristics of the English Aristocracy.

In it, she detailed the correct “U” (upper-class) way of speaking, as well as offering the “non-U” (non-upper-class) alternative. The book cemented her reputation as a snob, but when asked in a 1970 BBC interview whether she was “grieved” by what the public thought of her, she replied “Not in the least bit. I don’t care.”

Although Nancy was often disparaging about her own writing, especially her “indifferent novels,” Zoë Heller, who wrote the introduction to a 2010 edition of The Pursuit of Love, described Nancy as “a genius.”

Heller wrote that “beneath the brittle surface of Mitford’s wit there is something infinitely more melancholy at work — something that is apt to snag you and pull you into its dark undertow when you are least expecting it.”

Biographer Laura Thompson wrote that Nancy Mitford’s books “read like an enchantingly clever woman telling stories down the telephone.”

Last years

In 1972 Nancy was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur and a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). She was delighted by the first and amused by the second, which she remembered Waugh had once turned down as an “insult.”

By this time, however, she was suffering from a rare form of Hodgkin’s Disease that attacked her spine, the pain from which she once described as “something close to torture,” and which debilitated her for almost four years before she died at home in Versailles on 30 June 1973.

Nancy Mitford’s ashes are buried at the Church of St Mary’s in Swinbrook, Oxfordshire, alongside her parents and her sisters Pamela, Diana, and Unity, although she specifically requested that no cross appeared on her gravestone. She believed it to be a symbol of violence, and instead, a mole was carved like one that she had printed at the top of her writing paper.

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Nancy MitfordNovels

Highland Fling (1931)Christmas Pudding (1932)Wigs on the Green (1935)Pigeon Pie (1940)The Pursuit of Love (1945)Love in a Cold Climate (1949)The Blessing (1951)Don’t Tell Alfred (1960)Biographies (written by Nancy Mitford)

Madame de Pompadour (1954)Voltaire in Love (1957)The Sun King: Louis XIV at Versailles (1966)Frederick the Great (1970)Biographies about Nancy Mitford and the Mitford family

Nancy Mitford by Selina Hastings (2002)Life in a Cold Climate: Nancy Mitford, The Biography by Laura Thompson (2015)The Sisters: The Saga of the Mitford Family by Mary S. Lovell (2003)Nancy Mitford by Harold Acton (2019)The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters by Charlotte Mosley (2008)More information

Portraits of Nancy Mitford at the National Portrait Gallery Wikipedia Reader discussion of Mitford’s works on Goodreads In Pursuit of Nancy Mitford (Vanity Fair)The post Nancy Mitford, author of Love in a Cold Climate appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

November 6, 2022

Early Poems by Alice Dunbar-Nelson (from Violets and Other Tales)

Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875 – 1935; also known as Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson) was a poet, short story writer, essayist, and journalist associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Presented here are poems from Violets and Other Tales (1895), her first collection, when she was still Alice Ruth Moore, her original name.

Published when she was just twenty, Violets and Other Tales includes short stories interspersed with the poems. Some of this early work hints at feminism and social justice, in a preview of the kind of writing that would become her hallmark.

Dunbar-Nelson would later become at least as well known for her short stories and searingly honest essays as for her poetry, if not more so. More of her short stories, which have come to be known as the Creole stories, have recently come to light.

Her mixed heritage of Black, Creole, European, and Native American gave her a broad perspective on race. She explored racial issues in tandem with the varied and complex issues faced by women of color.

As her reputation grew, despite a brief and disastrous marriage to poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, she continued to explore sexism, racism, women’s work, and sexuality in the various genres in which she wrote.

Poems in this selection:

Three ThoughtsA PlaintImpressionsLegend of the NewspaperPaul to VirginiaIn MemoriamAt Bay St. LouisNew Year’s DayFarewellIf I Had KnownChalmetleThe IdlerLove and the ButterflyAmid the Roses More about the life and poetry of Alice Dunbar-Nelson Poetry Foundation Georgetown University: Classroom Issues and Struggles Women Writers You Should Know This Harlem Renaissance Writer Seemed to Live an Ordinary Life. . . . . . . . . . .

A Selection of Poems by Alice Dunbar-Nelson

highlights some of her later poetry

. . . . . . . . . . .

Three ThoughtsFIRST

How few of us

In all the world’s great, ceaseless struggling strife,

Go to our work with gladsome, buoyant step,

And love it for its sake, whate’er it be.

Because it is a labor, or, mayhap,

Some sweet, peculiar art of God’s own gift;

And not the promise of the world’s slow smile

of recognition, or of mammon’s gilded grasp.

Alas, how few, in inspiration’s dazzling flash,

Or spiritual sense of world’s beyond the dome

Of circling blue around this weary earth,

Can bask, and know the God-given grace

Of genius’ fire that flows and permeates

The virgin mind alone; the soul in which

The love of earth hath tainted not.

The love of art and art alone.

SECOND

“Who dares stand forth?” the monarch cried,

“Amid the throng, and dare to give

Their aid, and bid this wretch to live?

I pledge my faith and crown beside,

A woeful plight, a sorry sight,

This outcast from all God-given grace.

What, ho! in all, no friendly face,

No helping hand to stay his plight?

St. Peter’s name be pledged for aye,

The man’s accursed, that is true;

But ho, he suffers. None of you

Will mercy show, or pity sigh?”

Strong men drew back, and lordly train

Did slowly file from monarch’s look,

Whose lips curled scorn. But from a nook

A voice cried out, “Though he has slain

That which I loved the best on earth,

Yet will I tend him till he dies,

I can be brave.” A woman’s eyes

Gazed fearlessly into his own.

THIRD

When all the world has grown full cold to thee,

And man—proud pygmy—shrugs all scornfully,

And bitter, blinding tears flow gushing forth,

Because of thine own sorrows and poor plight,

Then turn ye swift to nature’s page,

And read there passions, immeasurably far

Greater than thine own in all their littleness.

For nature has her sorrows and her joys,

As all the piled-up mountains and low vales

Will silently attest—and hang thy head

In dire confusion, for having dared

To moan at thine own miseries

When God and nature suffer silently.

. . . . . . . . . . .

A PlaintDear God, ’tis hard, so awful hard to lose

The one we love, and see him go afar,

With scarce one thought of aching hearts behind,

Nor wistful eyes, nor outstretched yearning hands.

Chide not, dear God, if surging thoughts arise.

And bitter questionings of love and fate,

But rather give my weary heart thy rest,

And turn the sad, dark memories into sweet.

Dear God, I fain my loved one were anear,

But since thou will’st that happy thence he’ll be,

I send him forth, and back I’ll choke the grief

Rebellious rises in my lonely heart.

I pray thee, God, my loved one joy to bring;

I dare not hope that joy will be with me,

But ah, dear God, one boon I crave of thee,

That he shall ne’er forget his hours with me.

. . . . . . . . . . .

ImpressionsTHOUGHT.

A swift, successive chain of things,

That flash, kaleidoscope-like, now in, now out,

Now straight, now eddying in wild rings,

No order, neither law, compels their moves,

But endless, constant, always swiftly roves.

HOPE.

Wild seas of tossing, writhing waves,

A wreck half-sinking in the tortuous gloom;

One man clings desperately, while Boreas raves,

And helps to blot the rays of moon and star,

Then comes a sudden flash of light, which gleams on shores afar.

LOVE.

A bed of roses, pleasing to the eye,

Flowers of heaven, passionate and pure,

Upon this bed the youthful often lie,

And pressing hard upon its sweet delight,

The cruel thorns pierce soul and heart, and cause a woeful blight.

DEATH.

A traveller who has always heard

That on this journey he some day must go,

Yet shudders now, when at the fatal word

He starts upon the lonesome, dreary way.

The past, a page of joy and woe,—the future, none can say.

FAITH.

Blind clinging to a stern, stone cross,

Or it may be of frailer make;

Eyes shut, ears closed to earth’s drear dross,

Immovable, serene, the world away

From thoughts—the mind uncaring for another day.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Alice Dunbar-Nelson

. . . . . . . . . . .

Poets sing and fables tell us,

Or old folk lore whispers low,

Of the origin of all things,

Of the spring from whence they came,

Kalevala, old and hoary,

Æneid, Iliad, Æsop, too,

All are filled with strange quaint legends,

All replete with ancient tales,—

How love came, and how old earth,

Freed from chaos, grew for us,

To a green and wondrous spheroid,

To a home for things alive;

How fierce fire and iron cold,

How the snow and how the frost,—

All these things the old rhymes ring,

All these things the old tales tell.

Yet they ne’er sang of the beginning,

Of that great unbreathing angel,

Of that soul without a haven,

Of that gracious Lady Bountiful,

Yet they ne’er told how it came here;

Ne’er said why we read it daily,

Nor did they even let us guess why

We were left to tell the tale.

Came one day into the wood-land,

Muckintosh, the great and mighty,

Muckintosh, the famous thinker,

He whose brain was all his weapons,

As against his rival’s soarings,

High unto the vaulted heavens,

Low adown the swarded earth,

Rolled he round his gaze all steely,

And his voice like music prayed:

“Oh, Creator, wondrous Spirit,

Thou who hast for us descended

In the guise of knowledge mighty,

And our brains with truth o’er-flooded;

In the greatness of thy wisdom,

Knowest not our limitations?

Wondrous thoughts have we, thy servants,

Wondrous things we see each day,

Yet we cannot tell our brethren,

Yet we cannot let them know,

Of our doings and our happenings,

Should they parted be from us?

Help us, oh, Thou Wise Creator,

From the fulness of thy wisdom,

Show us how to spread our knowledge,

And disseminate our actions,

Such as we find worthy, truly.”

Quick the answer came from heaven;

Muckintosh, the famous thinker,

Muckintosh, the great and mighty,

Felt a trembling, felt a quaking,

Saw the earth about him open,

Saw the iron from the mountains

Form a quaint and queer machine,

Saw the lead from out the lead mines

Roll into small lettered forms,

Saw the fibres from the flax-plant,

Spread into great sheets of paper,

Saw the ink galls from the green trees

Crushed upon the leaden forms;

Muckintosh, the famous thinker,

Muckintosh, the great and mighty,

Felt a trembling, felt a quaking,

Saw the earth about him open,

Saw the flame and sulphur smoking,

Came the printer’s little devil,

Far from distant lands the printer,

Man of unions, man of cuss-words,

From the depths of sooty blackness;

Came the towel of the printer;

Many things that Muckintosh saw,—

Galleys, type, and leads and rules,

Presses, press-men, quoins and spaces,

Quads and caps and lower cases.

But to Muckintosh bewildered,

All this passed as in a dream,

Till within his nervous hand,

Hand with joy and fear a-quaking,

Muckintosh, the great and mighty,

Muckintosh, the famous thinker,

Held the first of our newspapers.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Paul to VirginiaFIN DE SIECLE.

I really must confess, my dear,

I cannot help but love you,

For of all girls I ever knew,

There’s none I place above you;

But then you know it’s rather hard,

To dangle aimless at your skirt,

And watch your every movement so,

For I am jealous, and you’re a flirt.

There’s half a score of fellows round,

You smile at every one,

And as I think to pride myself for basking in the sun

Of your sweet smiles, you laugh at me,

And treat me like a lump of dirt,

Until I wish that I were dead,

For I am jealous, and you’re a flirt.

I’m sorry that I’ve ever known

Your loveliness entrancing,

Or ever saw your laughing eyes,

With girlish mischief dancing;

‘Tis agony supreme and rare

To see your slender waist a-girt

With other fellows’ arms, you see,

For I am jealous, and you’re a flirt.

Now, girlie, if you’ll promise me,

To never, never treat me mean,

I’ll show you in a little while,

The best sweetheart you’ve ever seen;

You do not seem to know or care,

How often you’ve my feelings hurt,

While flying round with other boys,

For I am jealous, and you’re a flirt.

. . . . . . . . . . .

In MemoriamThe light streams through the windows arched high,

And o’er the stern, stone carvings breaks

In warm rich gold and crimson waves,

Then steals away in corners dark to die.

And all the grand cathedral silence falls

Into the hearts of those that worship low,

Like tender waves of hushed nothingness,

Confined nor kept by human earthly walls.

Deep music in its thundering organ sounds,

Grows diffuse through the echoing space,

Till hearts grow still in sadness’ mighty joy,

Or leap aloft in swift ecstatic bounds.

Mayhap ’twas but a dream that came to me,

Or but a vision of the soul’s desire,

To see the nation in one mighty whole,

Do homage on its bended, worshipping knee.

Through time’s heroic actions, the soul of man,

Alone proves what that soul without earth’s dross

Could be, and this, through time’s far-searching fire,

Hath proved thine white beneath the deepest scan.

A woman’s tribute, ’tis a tiny dot,

A merest flower from a frail, small hand,

To lay among the many petaled wreaths

About thy form,—a tribute soon forgot.

But if in all the incense to arise

In fragrance to the blue empyrean

The blended sweetness of the womens’ love

Goes pouring too, in all their heartfelt sighs.

And if one woman’s sorrow be among them too,

One woman’s joy for labor past

Be reckoned in the mighty teeming whole,

It is enough, there is not more to do.

Within the hearts of heroes small and great

There ‘bides a tenderness for weakling things

Within thy heart, the sorrowing country knows

These passions, bravest and the tenderest mate.

When man is dust, before the gazing eyes

Of all the gaping throng, his life lies wide

For all to see and whisper low about

Or let their thoughts in discord’s clatter rise.

But thine was pure and undefiled,

A record of long brilliant, teeming days,

Each thought did tend to further things,

But pure as the proverbial child.

Oh, people, that thy grief might find express

To gather in some vast cathedral’s hall,

That then in unity we might kneel and hear

Sublimity in sounds, voice our distress.

Peace, peace, the men of God cry, ye be bold,

The world hath known, ’tis Heaven who claims him now,

And in our railings we but cast aside

The noble traits he bid us hold.

So though divided through the land, in dreams

We see a people kneeling low,

Bowed down in heart and soul to see

This fearful sorrow, crushing as it seems.

And all the grand cathedral silence falls

Into the hearts of these that worship low,

Like tender waves of hushed nothingness,

Confined, nor kept by human earthly walls.

. . . . . . . . . . .

At Bay St. LouisSoft breezes blow and swiftly show

Through fragrant orange branches parted,

A maiden fair, with sun-flecked hair,

Caressed by arrows, golden darted.

The vine-clad tree holds forth to me

A promise sweet of purple blooms,

And chirping bird, scarce seen but heard

Sings dreamily, and sweetly croons

At Bay St. Louis.

The hammock swinging, idly singing,

Lissome nut-brown maid

Swings gaily, freely, to-and-fro;

The curling, green-white waters casting cool, clear shade,

Rock small, shell boats that go

In circles wide, or tug at anchor’s chain,

As though to skim the sea with cargo vain,

At Bay St. Louis.

The maid swings slower, slower to-and-fro,

And sunbeams kiss gray, dreamy half-closed eyes;

Fond lover creeping on with foot steps slow,

Gives gentle kiss, and smiles at sweet surprise.

The lengthening shadows tell that eve is nigh,

And fragrant zephyrs cool and calmer grow,

Yet still the lover lingers, and scarce breathed sigh,

Bids the swift hours to pause, nor go,

At Bay St. Louis.

. . . . . . . . . . .

New Year’s DayThe poor old year died hard; for all the earth lay cold

And bare beneath the wintry sky;

While grey clouds scurried madly to the west,

And hid the chill young moon from mortal sight.

Deep, dying groans the aged year breathed forth,

In soughing winds that wailed a requiem sad

In dull crescendo through the mournful air.

The new year now is welcomed noisily

With din and song and shout and clanging bell,

And all the glare and blare of fiery fun.

Sing high the welcome to the New Year’s morn!

Le roi est mort. Vive, vive le roi! cry out,

And hail the new-born king of coming days.

Alas! the day is spent and eve draws nigh;

The king’s first subject dies—for naught,

And wasted moments by the hundred score

Of past years rise like spectres grim

To warn, that these days may not idly glide away.

Oh, New Year, youth of promise fair!

What dost thou hold for me? An aching heart?

Or eyes burnt blind by unshed tears? Or stabs,

More keen because unseen?

Nay, nay, dear youth, I’ve had surfeit

Of sorrow’s feast. The monarch dead

Did rule me with an iron hand. Be thou a friend,

A tender, loving king—and let me know

The ripe, full sweetness of a happy year.

. . . . . . . . . . .

FarewellFarewell, sweetheart, and again farewell;

To day we part, and who can tell

If we shall e’er again

Meet, and with clasped hands

Renew our vows of love, and forget

The sad, dull pain.

Dear heart, ’tis bitter thus to lose thee

And think mayhap, you will forget me;

And yet, I thrill

As I remember long and happy days

Fraught with sweet love and pleasant memories

That linger still

You go to loved ones who will smile

And clasp you in their arms, and all the while

I stay and moan

For you, my love, my heart and strive

To gather up life’s dull, gray thread

And walk alone.

Aye, with you love the red and gold

Goes from my life, and leaves it cold

And dull and bare,

Why should I strive to live and learn

And smile and jest, and daily try

You from my heart to tare?

Nay, sweetheart, rather would I lie

Me down, and sleep for aye; or fly

To regions far

Where cruel Fate is not and lovers live

Nor feel the grim, cold hand of Destiny

Their way to bar.

I murmur not, dear love, I only say

Again farewell. God bless the day

On which we met,

And bless you too, my love, and be with you

In sorrow or in happiness, nor let you

E’er me forget.

. . . . . . . . . . .

If I Had KnownIf I had known

Two years ago how drear this life should be,

And crowd upon itself all strangely sad,

Mayhap another song would burst from out my lips,

Overflowing with the happiness of future hopes;

Mayhap another throb than that of joy.

Have stirred my soul into its inmost depths,

If I had known.

If I had known,

Two years ago the impotence of love,

The vainness of a kiss, how barren a caress,

Mayhap my soul to higher things have soarn,

Nor clung to earthly loves and tender dreams,

But ever up aloft into the blue empyrean,

And there to master all the world of mind,

If I had known.

. . . . . . . . . . .

ChalmetleWreaths of lilies and immortelles,

Scattered upon each silent mound,

Voices in loving remembrance swell,

Chanting to heaven the solemn sound.

Glad skies above, and glad earth beneath;

And grateful hearts who silently

Gather earth’s flowers, and tenderly wreath

Woman’s sweet token of fragility.

Ah, the noble forms who fought so well

Lie, some unnamed, ‘neath the grassy mound;

Heroes, brave heroes, the stories tell,

Silently too, the unmarked mounds,

Tenderly wreath them about with flowers,

Joyously pour out your praises loud;

For every joy beat in these hearts of ours

Is only a drawing us nearer to God.

Little enough is the song we sing,

Little enough is the tale we tell,

When we think of the voices who erst did ring

Ere their owners in smoke of battle fell.

Little enough are the flowers we cull

To scatter afar on the grass-grown graves,

When we think of bright eyes, now dimmed and dull

For the cause they loyally strove to save.

And they fought right well, did these brave men,

For their banner still floats unto the breeze,

And the pæans of ages forever shall tell

Their glorious tale beyond the seas.

Ring out your voices in praises loud,

Sing sweet your notes of music gay,

Tell me in all you loyal crowd

Throbs there a heart unmoved to-day?

Meeting together again this year,

As met we in fealty and love before;

Men, maids, and matrons to reverently hear

Praises of brave men who fought of yore.

Tell to the little ones with wondering eyes,

The tale of the flag that floats so free;

Till their tiny voices shall merrily rise

In hymns of rejoicing and praises to Thee.

Many a pure and noble heart

Lies under the sod, all covered with green;

Many a soul that had felt the smart

Of life’s sad torture, or mayhap had seen

The faint hope of love pass afar from the sight,

Like swift flight of bird to a rarer clime

Many a youth whose death caused the blight

Of tender hearts in that long, sad time.

Nay, but this is no hour for sorrow;

They died at their duty, shall we repine?

Let us gaze hopefully on to the morrow

Praying that our lives thus shall shine.

Ring out your bugles, sound out your cheers!

Man has been God-like so may we be.

Give cheering thanks, there dry up those tears,

Widowed and orphaned, the country is free!

Wreathes of lillies and immortelles,

Scattered upon each silent mound,

Voices in loving remembrance swell,

Chanting to heaven the solemn sound,

Glad skies above, and glad earth beneath,

And grateful hearts who silently

Gather earth’s flowers, and tenderly wreath

Woman’s sweet token of fragility.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The IdlerAn idle lingerer on the wayside’s road,

He gathers up his work and yawns away;

A little longer, ere the tiresome load

Shall be reduced to ashes or to clay.

No matter if the world has marched along,

And scorned his slowness as it quickly passed;

No matter, if amid the busy throng,

He greets some face, infantile at the last.

His mission? Well, there is but one,

And if it is a mission he knows it, nay,

To be a happy idler, to lounge and sun,

And dreaming, pass his long-drawn days away.

So dreams he on, his happy life to pass

Content, without ambitions painful sighs,

Until the sands run down into the glass;

He smiles—content—unmoved and dies.

And yet, with all the pity that you feel

For this poor mothling of that flame, the world;

Are you the better for your desperate deal,

When you, like him, into infinitude are hurled?

. . . . . . . . . . .

Love and the ButterflyI heard a merry voice one day

And glancing at my side,

Fair Love, all breathless, flushed with play,

A butterfly did ride.

“Whither away, oh sportive boy?”

I asked, he tossed his head;

Laughing aloud for purest joy,

And past me swiftly sped.

Next day I heard a plaintive cry

And Love crept in my arms;

Weeping he held the butterfly,

Devoid of all its charms.

Sweet words of comfort, whispered I

Into his dainty ears,

But Love still hugged the butterfly,

And bathed its wounds with tears.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Amid the RosesThere is tropical warmth and languorous life

Where the roses lie

In a tempting drift

Of pink and red and golden light

Untouched as yet by the pruning knife.

And the still, warm life of the roses fair

That whisper “Come,”

With promises

Of sweet caresses, close and pure

Has a thorny whiff in the perfumed air.

There are thorns and love in the roses’ bed,

And Satan too

Must linger there;

So Satan’s wiles and the conscience stings,

Must now abide—the roses are dead.

The post Early Poems by Alice Dunbar-Nelson (from Violets and Other Tales) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

October 28, 2022

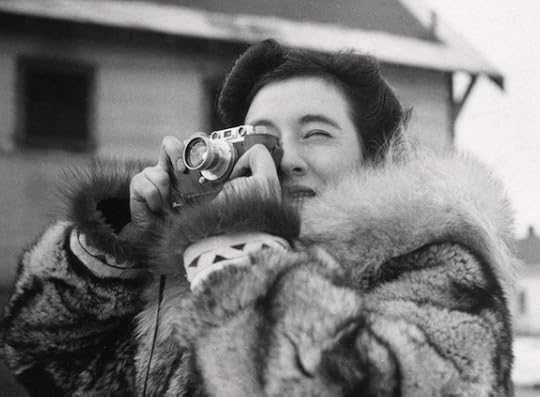

Worth a Thousand Words: 4 Trailblazing Women Photojournalists

Though Margaret Bourke-White and Dorothea Lange were two of the most influential pioneering modern photojournalism, the field is still male dominated today. As we learn more about them, along with the two other trailblazing American women photojournalists presented here (Jessie Tarbox Beals and Ruth Gruber), it’s worth musing on why this is.

A photojournalist is a reporter with a camera. Some photojournalists (past and present) have only taken pictures, and a different reporter writes the text that goes with them. Others take photos as well as write articles.

The challenges of photojournalismIn some ways, a photojournalist’s job can be trickier than that of a text-only reporter. They need to consider whether a photo might be an invasion of privacy — for example, a shot of someone who’s injured, or even dead.