Nava Atlas's Blog, page 18

June 21, 2023

Amy Lowell on How a Poet Learns the Craft

The American poet Amy Lowell (1874 – 1925) was best known for a form of poetry called Imagism. She dedicated her career to perfecting her craft as a poet, and was practically an evangelist for the art of poetry writing. Lowell produced poetry prolifically and spoke widely about its art and craft.

Lowell defined Imagism as the “concentration is of the very essence of poetry,” and she aspired to “produce poetry that is hard and clear, never blurred nor indefinite.”

The following is from the preface of her 1914 collection, Sword Blades and Poppy Seed, in which she argues that a poet is not born but made. The writer of poetry must learn what she called their “trade,” comparable to how a cabinet-maker or any other craftsperson first learns technique and then builds upon it.

And now, let’s let Amy Lowell speak for herself, as she does so eloquently, and glean her wisdom on how a poet learns her (or as is the case, his, which is often expressed as the generic default gender in this piece) craft.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Amy Lowell

. . . . . . . . . .

The poet is not born, but madeNo one expects a man to make a chair without first learning how, but there is a popular impression that the poet is born, not made, and that his verses burst from his overflowing heart of themselves.

As a matter of fact, the poet must learn his trade in the same manner, and with the same painstaking care, as the cabinet-maker. His heart may overflow with high thoughts and sparkling fancies, but if he cannot convey them to his reader by means of the written word he has no claim to be considered a poet.

A workman may be pardoned, therefore, for spending a few moments to explain and describe the technique of his trade. A work of beauty which cannot stand an intimate examination is a poor and jerry-built thing.

Poetry should not try to teachIn the first place, I wish to state my firm belief that poetry should not try to teach, that it should exist simply because it is a created beauty, even if sometimes the beauty of a gothic grotesque.

We do not ask the trees to teach us moral lessons, and only the Salvation Army feels it necessary to pin texts upon them. We know that these texts are ridiculous, but many of us do not yet see that to write an obvious moral all over a work of art, picture, statue, or poem, is not only ridiculous, but timid and vulgar.

We distrust a beauty we only half understand, and rush in with our impertinent suggestions. How far we are from “admitting the Universe!”

The Universe, which flings down its continents and seas, and leaves them without comment. Art is as much a function of the Universe as an Equinoctial gale, or the Law of Gravitation; and we insist upon considering it merely a little scroll-work, of no great importance unless it be studded with nails from which pretty and uplifting sentiments may be hung!

For the purely technical side I must state my immense debt to the French, and perhaps above all to the, so-called, Parnassian School, although some of the writers who have influenced me most do not belong to it.

High-minded and untiring workmen, they have spared no pains to produce a poetry finer than that of any other country in our time. Poetry so full of beauty and feeling, that the study of it is at once an inspiration and a despair to the artist …

Finding new and striking imagesThe poet with originality and power is always seeking to give his readers the same poignant feeling which he has himself. To do this he must constantly find new and striking images, delightful and unexpected forms.

Take the word “daybreak,” for instance. What a remarkable picture it must once have conjured up! The great, round sun, like the yolk of some mighty egg, BREAKING through cracked and splintered clouds.

But we have said “daybreak” so often that we do not see the picture any more, it has become only another word for dawn. The poet must be constantly seeking new pictures to make his readers feel the vitality of his thought.

. . . . . . . . . .

Amy Lowell on her “Vers Libre” poetry

. . . . . . . . . .

Many of the poems in this volume [here Amy Lowell is referring to Sword Blades and Poppy Seed, the book from which this essay comes] are written in what the French call “Vers Libre,”a nomenclature more suited to French use and to French versification than to ours.

I prefer to call them poems in “unrhymed cadence,” for that conveys their exact meaning to an English ear. They are built upon “organic rhythm,” or the rhythm of the speaking voice with its necessity for breathing, rather than upon a strict metrical system.

They differ from ordinary prose rhythms by being more curved, and containing more stress. The stress, and exceedingly marked curve, of any regular metre is easily perceived. These poems, built upon cadence, are more subtle, but the laws they follow are not less fixed.

Merely chopping prose lines into lengths does not produce cadence, it is constructed upon mathematical and absolute laws of balance and time. In the preface to his Poems, Henley speaks of “those unrhyming rhythms in which I had tried to quintessentialize, as (I believe) one scarce can do in rhyme.”

The desire to “quintessentialize,” to head-up an emotion until it burns white-hot, seems to be an integral part of the modern temper, and certainly “unrhymed cadence” is unique in its power of expressing this.

In conclusion: poems must speak for themselvesThree of these poems are written in a form which, so far as I know, has never before been attempted in English. M. Paul Fort is its inventor, and the results it has yielded to him are most beautiful and satisfactory.

Perhaps it is more suited to the French language than to English. But I found it the only medium in which these particular poems could be written. It is a fluid and changing form, now prose, now verse, and permitting a great variety of treatment.

But the reader will see that I have not entirely abandoned the more classic English metres. I cannot see why, because certain manners suit certain emotions and subjects, it should be considered imperative for an author to employ no others. Schools are for those who can confine themselves within them. Perhaps it is a weakness in me that I cannot.

In conclusion, I would say that these remarks are in answer to many questions asked me by people who have happened to read some of these poems in periodicals.

They are not for the purpose of forestalling criticism, nor of courting it; and they deal, as I said in the beginning, solely with the question of technique. For the more important part of the book, the poems must speak for themselves.

Amy Lowell, May 19, 1914.

More by Amy Lowell on this site

The Cremona Violin A Roxbury Garden Lilacs PatternsThe post Amy Lowell on How a Poet Learns the Craft appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 13, 2023

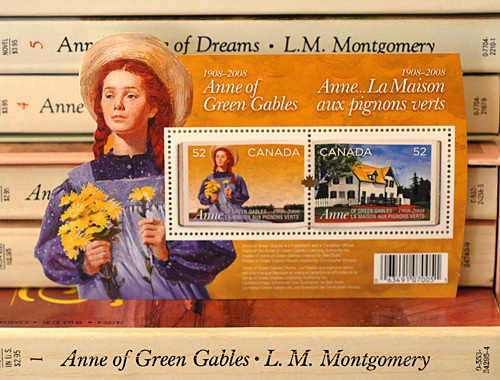

Zora Neale Hurston’s Seraph on the Suwanee: Views from 1948 & Beyond

Seraph on the Suwanee, Zora Neale Hurston’s fourth and last published novel (1948), was an outlier among her works, which included numerous short stories and ethnographic collections. The reason: it was her only book that was written about white people — specifically, Florida’s “white crackers.”

Exploring the cultural differences between the meek and colorless heroine, Arvay and her handsome, enterprising husband Jim, the novel received mixed-to-positive reviews by the white press.

Some reviewers bent over backwards to praise the fact that a Black writer produced a novel that wasn’t about race issues, bringing to light the lives and dialect of the turpentine people of Florida.

Kirkus Reviews’ succinct 1948 review read: “The colorful Florida ‘cracker’ language holds the mood throughout, and the total effect is one of charm and readability. Recommended.”

On the other hand, The New York Times titled their review “Freud in Turpentine” and wrote: “Arvay never heard of Freud … but she’s a textbook picture of a hysterical neurotic, right to the end of the novel.”

Black reviewers have been generally critical of the novel. I was unable to find full reviews of Seraph on the Suwanee in any Black newspapers from 1948, but commentary about the book by contemporary critics is readily available.

Professor John C. Charles, in a 2009 essay titled “Talk About the South: Unspeakable Things Unspoken in Zora Neale Hurston’s Seraph on the Suwanee” wrote that compared with Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora’s much lauded and studied, Serpaph:

“… has received a far chillier response and until recently often condemned or dismissed out of hand … Seraph has tended to baffle and disturb even Hurston’s most devoted readers. Critic Mary Helen Washington, for example, dismisses Seraph as ‘an awkward and contrived novel, as vacuous as a soap opera.’ And Bernard Bell expels it from his influential study on the African American novel because ‘[it] is neither comic, nor folkloric, nor about Blacks.’

Late literary critic Claudia Tate, in a 1997 essay titled “Zora Neale Hurston’s Whiteface Novel” wrote, “Despite the tremendous popularity of the works of Zora Neale Hurston over the last two decades, Seraph on the Suwanee is still a marginal work.”

Zora dedicated the book “To Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Mrs. Spessard L. Holland with loving admiration.” Find a full plot summary and character list here.

Following are three 1948 sample reviews from the perspective of white reviewers.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

In the Turpentine CountryFrom the original review by Virginia Oakey in the Richmond (VA) Times-Dispatch, October 24, 1948: Arvay Meserve, heroine of Seraph on the Suwanee, is not a woman one would choose to spend a single evening with, for she is without humor or perception and suffers from pathological timidity. Yet the story of her life is definitely worth an evening or two.

This unenviable creature was born in the turpentine country of West Florida where life, as described by Miss Hurston, is a mean and degrading mistake. A few chapters into the book, Harvey is seduced by and married to (in the space of a summer afternoon) the most sought-after young man in the county, Jim Meserve.

Arvay’s suffering from her near-psychopathic feeling of inferiority is only increased by her excellent marriage. She takes a feeling of guilt to her wedding bed, for she has lived in mental adultery with her sister’s husband for several years. Now she lives in fear of the exposure of her secret.

The first of Arvay’s children is an imbecile. She believes this to be her punishment, so she decides the boy must remain with her — a decision that results in one of the most tragic incidents in the story.

Two other children are born to Arvay and her “high-toned, independent, money-making” husband. They are handsome, intelligent children; Arvay never believes herself worth of them, nor of her husband.

This goes on for twenty years. Jim Meserve’s patience is exhausted; yours certainly will be, too. However, those years aren’t without drama, and occasionally, in spite of Arvay, considerable humor. Arvay is forced to face herself. This she does with her customary cowardice until a death and a storm intervene —and she is equal to both.

Miss Hurston writes authoritatively of the “teppentine” (turpentine) country, the citrus belt, and life aboard a shrimping boat, all of which provide a background for Arvay’s “high-Christian” humility. The author has caught the patois of those areas; it’s colorful, often crude, and frequently poetic.

She writes of “the raw-head-and-bloody-bones of lonesomeness” and of a young girl dressed in her best clothes “looking as if she had wallowed in a rainbow.” In one instance “the hours stumbled by on rusty ankles.” In another, hours were like “raw, bony, homeless dogs — whining of their emptiness.”

“Teppentine” people do not say “She has eaten humble pie.” They say, “She has been to hell’s kitchen and licked out all the pots.” Indirect action they describe as “hitting a straight blow with a crooked stick.” A person who is living beyond his means is “giving a mighty high kick for a low cow.”

Despite Arvay’s meagre spirit, Miss Hurston has written a book that is extremely pleasant company.

Way Down Upon the Suwanee River

From the original review of Seraph On The Suwanee by Lewis Gannett in The Mirror (Los Angeles), October 18, 1948: I wish that Zora Neale Hurston had more to say in her new novel, for I love the speech rhythm with which she can make anything she writes a delight.

This is a story about a Florida cracker girl named Arvay and her ways of loving Jim Merserve. You could say about Miss Hurston’s story what Jim says about Arvay: she “took long enough to stumble round the teacup to get to the handle.”

Sawley on the Suwanee, where courting was public

Down in Sawley on the Suwanee, courting was public. The doings were something like a well-trained hound dog tackling a bobcat, and everyone looked on.

Jim Meserve had a face full of grin, and when he was around, Arvay just couldn’t make her face look like she’d been feasting off green persimmons. For the first time in her life, her vanity put on a little flesh. While Jim was talking, she almost forgot that she had given up the world after her sister snatched the Rev. Carl Middleton away from her.

Sawley, they said, was a town that wore out the knees of its breeches sliding to the Cross and wore out the seat of its pants backsliding, but outside of Arvay, few Sawleyites got thin thinking about the Reverend Middleton.

Some of them said you couldn’t even raise a tune if you put a wagonload of good compost under him and ten sacks of commercial fertilizer.

The world seems sad and dreary

Arvay just couldn’t believe how happy she was, married to Jim. She couldn’t get over what Jim called that old missionary distemper. She was afraid of admitting she was herself. And there came a time when Jim shouted at her that he didn’t want a standstill kind of love; he wanted a knowing and doing love, and Arvay loved like a coward.

Sometimes Miss Hurston, whose father was Mayor of the all-Negro town of Eatonville, Florida, hasn’t much use for people of any color who lack get-up-and-go and spend their spare time bewailing bad luck.

Lightning bugs in daytime

Arvay tries to disapprove of Jim, but her resolutions are:

“… just like the lightning bugs holding a convention.They met at night and made scorning speeches against the sun and swore to do away with it and light up the world themselves. But the sun came up the next morning and they all went under the leaves and owned up that the sun was boss-man in the world.”

Arvay was always throwing the rabbit into the briar patch.

Unfortunately, the lightning bugs don’t hold a convention on every one of Miss Hurston’s pages her boss-man is a little too perfect, and the Rev. Carl Middleton sits a little lower in the grass than the lowest insect along tobacco road. Even with Miss Hurston’s imagery flashing all about him, one gets a little tired of Jim Meserve’s he-man loving and Arvay’s stumbling around the teacup.

One hopes that Miss Hurston will put into her next novel more solid soup stock. She has a rare talent for cooking with words — as she proved with Jonah’s Gourd Vine and Mules and Men. But in Seraph On The Suwanee, she is wasting it on wilted turnip greens.

. . . . . . . . .

Books by Zora Neale Hurston: Fiction, Folklore & More

. . . . . . . . .

A Novel About Poor Whites in the South, Without a Racial IssueFrom the original review by Carter Brooke Jones in The Evening Star, Washington DC, October 17, 1948: It might be pointed out, before considering other merits of this novel, that Miss Hurston has done at least one thing noteworthy in these times.

She has written about the much-chronicled poor whites of the South without condescension, pity, or sentimentality.

She has presented a group of poor Southerners as recognizable human beings. Her characters aren’t fools because they have little formal education and speak a form of English that approaches a patois.

Some of them, indeed, are exceedingly shrewd, make money, and do well enough for themselves. Others are dumb, lazy, and hopeless. But so are some college graduates.

If the successful ones are underprivileged, they haven’t heard about it. They aren’t oblivious to the advantages of schooling, and most of their sons and daughters go to college. Their problems and emotions are pretty much those of people everywhere, which may come as a surprise to readers of Caldwell, Faulkner, and their disciples.

Miss Hurston has managed to write of the contemporary, or recently past South without bringing in a lynching or touching on the race problem. In fact, the friendship of a Southern white man and a black man is an outstanding phase of this story. All this sidestepping of social and economic issues no doubt will disturb Marxist critics if they bother to examine the book.

In the citrus belt

The story starts in a little town on the West Coast of Florida when Arvay Henson, daughter of a bedraggled poor family abandons her intentions of dedicating her life as a Baptist missionary and marries Jim Meserve. Jim is the strongest and best-looking young man in the turpentine camp. He moves Arvay and their baby south to the citrus belt.

Before long, he is the owner of a nice piece of land. He ends up owning a fleet of fishing boats, a citrus grove, and part of a swanky real estate development.

It’s essentially the story of Arvay and her struggle to understand and utilize a world strange to her. She is narrow and afraid of anything new. Jim, with little more education than she had, is daring, clever, and resourceful. He is also domineering, and Arvay sees only his obvious traits, overlooking the sacrifices he makes and the changes he takes for her and their children.

Years pass before she appreciates Jim, and her awakening comes almost too late, for his patience has worn out at last.

What about the war?

Earthy humor and the pathos of groping and misunderstanding mingle in Miss Hurston’s narrative. A novel of considerable merit should be allowed some deficiencies. In Seraph on the Suwanee, some minor episodes are overdeveloped, while others are passed over quickly.

The characters she describes might have had little interest in the outside world, but sure more than she indicates. The story starts in the early 1900s and continues for more than twenty years; yet the First World War, which must have had a measure of influence on some of the people in the story, isn’t even mentioned.

More about Seraph on the Suwanee Zora Neale Hurston and the WPA in Florida On the official Zora Neale Hurston website Reader discussion on Goodreads

The post Zora Neale Hurston’s Seraph on the Suwanee: Views from 1948 & Beyond appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 12, 2023

Six Novels by Shirley Jackson: Psychological Thrillers by a Master

American author Shirley Jackson (1916 – 1965) was known for fiction and nonfiction works that have influenced generations of writers who came after her. Presented here are the six novels by Shirley Jackson published in her lifetime. If you’re looking for where to begin with Shirley Jackson’s books, start anywhere — they’re all engrossing reads.

Jackson remains best known for “The Lottery” (1948), her widely anthologized (and also widely banned) short story. This controversial work, published the same year as her first novel, put her on the literary map.

It’s not easy to categorize Jackson’s work. Psychological terror or thriller may come close, if one considers that Stephen King and Neil Gaiman have cited her as an influence. Her six novels and scores of short stories uncover the evil and ugliness that lurk just under the surface of propriety and social mores.

In addition to her six novels, she wrote dozens of short stories and was also known for her wryly humorous (and idealized) accounts of family life, Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons.

Jackson’s two last finished novels, The Haunting of Hill House (1959) and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962) are considered her masterworks. Following each of the brief introductions to the novels, you’ll find a link to a full review and/or analysis.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Road Through the Wall (1948)

The Road Through the Wall was Shirley Jackson’s first novel. That was also the year when her short story, “The Lottery,” was published, making her instantly famous (as well as infamous).

Jackson claimed that the novel was loosely based on her childhood in a well-to-do neighborhood in California. Admitting that it was somewhat of a revenge novel, she asserted that a first novel’s purpose, after all, was to get back one’s parents.

As in several of Jackson’s stories and novels, we do indeed see the world – and in this case Pepper Street is its own world – largely through children and their mothers; Jackson didn’t – possibly couldn’t – ever write a sympathetic male character.

Fourteen-year-old Harriet lives in a middle-class suburb in California – not completely unlike the one where Jackson herself was born – where everyone knows everyone else’s business.

This a chamber piece where many characters have an equal part and Harriet is simply one of the actors in the drama. Nevertheless, she is drawn in great detail and the novel does show her awkwardly coming of age, at least in one sense.

An analysis of The Road Through the Wall.

. . . . . . . . . .

Hangsaman (1952)

Shirley Jackson occasionally turned to true crime news stories as jumping-off points for her novels of psychological terror and suspense. This was apparently the case for her second novel, Hangsaman (1951).

Jackson, her husband, and their four children were living in North Bennington when 18-year-old Bennington College freshman Paula Jean Weldon disappeared. She went out for a hike on December 1, 1946, and simply never returned.

There were, and have since been, theories about what might have happened to Weldon, but neither she —nor her body — were ever found.

Hangsaman is the dark and unsettling tale of a young woman named Natalie Waite as she sets off into the world of college. This brief synopsis is from the 2013 reissue edition (Penguin):

“Seventeen-year-old Natalie Waite longs to escape home for college. Her father is a domineering and egotistical writer who keeps a tight rein on Natalie and her long-suffering mother. When Natalie finally does get away, however, college life doesn’t bring the happiness she expected. Little by little, Natalie is no longer certain of anything—even where reality ends and her dark imaginings begin.”

A review of Hangsaman An analysis of Hangsaman. . . . . . . . . .

The Bird’s Nest (1954)

Elizabeth Richmond, the novel’s main character, has multiple personality disorder. As she splinters, these beings become Bess, Beth, and Betsy. You’ll find a thorough plot summary here.

In this post, we’ll see three of the reviews of the novel, which received wide coverage. Views of the novel were decidedly mixed. Some of the reviews found the subject fresh and intriguing; others found Jackson’s treatment of a complex psychological condition too simplistic, and the resolution inexplicably neat.

The multiple personality trope was pretty unique at the time, leaving some reviewers baffled by the shifting personalities. The New York Times reviewer opined that the plot of The Bird’s Nest was “too bizarre for the necessary suspension of disbelief.”

Contemporary reconsiderations have been kinder to the novel. In a 2014 review in Flavorwire, Tyler Coates wrote, “The Bird’s Nest is a monumental work, not just for spurring a renewed interest into the multiple-personality story, but because its inventive storytelling structure gives a powerful look at a young woman trapped within her own body and mind.”

Three 1954 reviews of The Bird’s Nest

. . . . . . . . . .

The Sundial (1958)

Though The Sundial was generally well received, Jackson had yet to reach her peak with her fourth novel. A 1958 Chicago Tribune review called it “entertaining, absorbing, and disturbing,” and encapsulated the plot succinctly:

“An oddly assorted group dwells in the Halloran mansion, on a vast, walled estate. It is dominated ruthlessly by Mrs. Halloran, wife of the sickly heir of the founder, who may have murdered her own son to assure her control. Assorted relatives, a governess, and a young man of vague duties are the original entourage to which some random members are added.

To spinsterish Aunt Fanny, the founder’s daughter, a revelation is vouchsafed from her deceased father. The dreadful, fiery end of the world is imminent. All those in the safety of the father’s house will survive, to emerge to a new world.

Through successive revelations, the truth of this apocalypse impresses itself on all the group. The novel follows their preparations for the majestic even as the hour draws near. The suspense becomes great, the events are surprising, but how Miss Jackson plays out her end game is classified information.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Haunting of Hill House (1959)

The Haunting of Hill House is a novel in the gothic horror genre, though it might be more accurately described as a literary ghost story. A finalist for the National Book Award, it’s a masterful story of psychological terror.

Hill House is a mansion built by Hugh Crain, who long ago passed away. Dr. John Montague, an investigator of the supernatural, wishes to conduct a study there to find the existence of spirits.

With him are three young companions including Luke, the young heir to the mysterious house, and two young women, Eleanor and Theordora. Eleanor is unquestionably the central character, and a close reading of the novel is an exploration of her essential loneliness and psychological breakdown.

Numerous contemporary writers have sung the praises of The Haunting of Hill House and/or cited it as an influence on their own work. Here is Neil Gaiman, in a New York Times interview (2018):

“The books that have profoundly scared me when I read them … But Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House beats them all: a maleficent house, real human protagonists, everything half-seen or happening in the dark. It scared me as a teenager and it haunts me still, as does Eleanor, the girl who comes to stay.”

A review and analysis of The Haunting of Hill House

. . . . . . . . .

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962) was Jackson’s last published work in her lifetime. The narrator, Mary Katherine “Merricat” Blackwood, lives with her sister and uncle on an isolated estate in rural Vermont.

The Blackwoods have been shunned by the neighbors in the nearby village due to a tragedy — murder by poisoning — that occurred some years earlier. This critically acclaimed novel has been an inspiration to authors that came after who write in the thriller and mystery genres.

The opening paragraph of We Have Always Lived in the Castle is iconic, and pure Shirley Jackson:

“My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantaganet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in my family is dead.”

A review of We Have Always Lived in the Castle An analysis of We Have Always Lived in the Castle Shirley Jackson’s books on Bookshop.org*

Shirley Jackson’s books on Bookshop.org*

. . . . . . . . . .*This is a Bookshop.org affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps us to continue to grow.

The post Six Novels by Shirley Jackson: Psychological Thrillers by a Master appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 10, 2023

The Bird’s Nest by Shirley Jackson — three 1954 reviews

Of Shirley Jackson’s six novels completed within her lifetime, The Bird’s Nest (1954) is less known and read than her 1948 short story, “The Lottery,” or her late novels, The Haunting of Hill House (1959) and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962).

Yet like all of Jackson’s works, this one is deserving of reconsideration. Though just forty-nine when she died, she left behind a large body of fiction and nonfiction works that have influenced generations of writers who came after her.

Elizabeth Richmond, the novel’s main character, has multiple personality disorder. As she splinters, these beings become Bess, Beth, and Betsy. You’ll find a thorough plot summary here.

Presented here are three reviews of this widely publicized novel, which reflect the decidedly mixed coverage. Some critics found its subject fresh and intriguing; others found the treatment of a complex psychological condition too simplistic and the resolution inexplicably neat.

Mixed reviews, and a contemporary reconsideration

Kirkus Reviews offered more of a brief plot summary than a substantive review in 1954, but concluded that for “a special audience, an exploratory of precarious and unpredictable variations, this has a certain fascination.”

The multiple personality trope was pretty unique at the time, leaving some reviewers baffled by the shifting personalities. The 1957 film (based on the book of the same year) The Three Faces of Eve, and later Sybil (1973) and its subsequent television movie would bring the subject to the mainstream.

The New York Times reviewer opined that the plot of The Bird’s Nest was “too bizarre for the necessary suspension of disbelief.” He and other reviewers wondered if psychiatric disorder were a worthy subject for fiction in the first place. Jackson was perturbed by reviewers’ interpretation of Elizabeth’s condition as schizophrenia, which isn’t what she had intended.

Contemporary reconsiderations have been kinder to the novel. In a 2014 review in Flavorwire, Tyler Coates wrote, “The Bird’s Nest is a monumental work, not just for spurring a renewed interest into the multiple-personality story, but because its inventive storytelling structure gives a powerful look at a young woman trapped within her own body and mind.”

A misbegotten film adaptation

1957 saw the release of the film adaptation of The Bird’s Nest, retitled Lizzie. Jackson was thrilled with her first sale of film rights but was unhappy with the outcome. Jackson called the movie “Abbott and Costello meet a multiple personality.”

Ruth Franklin, in Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, wrote:

“… She found it more unnerving than she expected to have her characters come to life on the screen in a way utterly different from how she had imagined them …

Elizabeth, transformed into ‘Lizzie’ (a character that does not exist in the novel), becomes a drunken slut; Aunt Morgen is bawdy and flirtatious; and the doctor cures his patient with an incoherent combination of Rorschach inkblots, Freudian analysis, and Jungian therapy.

The film was rushed to open ahead of The Three Faces of Eve. But while Eve went on to win an Academy Award, critics were lukewarm on Lizzie. The Newsweek reviewer offered an apt summary: ‘Major mental muddle melodramatized.’”

Following are three reviews that represent varying views of critics. As you’ll see, even these reviews are neither pans nor raves, but fall somewhere in the mixed range. In the tradition of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, recognizing that a human can contain multitudes, Shirley Jackson’s mid-twentieth-century eye view is well worth exploring.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: The Haunting of Hill House

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review by Florence Zetlin in The Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, June 20, 1954: The Bird’s Nest is an extension of the horror themes in Shirley Jackson’s superb story, “The Lottery.”

The hints of black magic and psychological nightmare are here developed into a full-length novel that dwells on the ultimate terror — that the most horrifying of all experiences are those that lie deep within the human psyche and cause one to fear oneself.

Within the personality of one nice, dull young woman we read of an underground conspiracy of antagonistic elements resulting, at first, in a cold war and phony peace. And later, in horrible civil warfare.

At some time lost to conscious memory, Elizabeth R. has forsaken herself as she was meant to be because she had been so terribly frightened by her life, and had managed to contrive for herself an artificial neutrality in which she appears as a listless, amenable, stupid girl.

To stave off the ultimate terror, she invented a number of minor hells for herself: headaches, backaches, and stupidity. At twenty-four, she had no friends, no plans, and no life except her routine job at the Owenstown Museum and a dreary second-hand social life provided by her maiden aunt with whom she lived.

It was when the museum underwent repairs and a gaping hole next to Elizabeth’s desk revealed the decaying skeleton of the old structure that Elizabeth began to behave strangely.

She received a series of disconcerting anonymous letters, which she cherished in spite of their obscene nature. Her headaches grew worse, and most frightening of all, she embarrassed her aunt Morgen by insulting her and her friends with no after-memory of these lapses of decorum.

The museum, with its ill-assorted antiquities, is the metaphor for Elizabeth’s personality. And the gaping fissure that runs through the wall presages the fate of her disrupted mind.

When her alarmed Aunt Morgen got her to a doctor for treatment, Elizabeth’s eyes “held the mute appeal of an animal, hurt beyond understanding and crying for help.” But like an animal, she wouldn’t communicate except with the face of distress. Words would not come.

Dr. Wright tried hypnosis, and to his horror saw her personality spring apart into four separate, independent beings, each struggling for control. Each personality could — and did — take over, involving Elizabeth in episodes of mounting fearfulness.

The author’s equal attraction to the explanations offered by black magic and psychiatry adds to the confusion of the reader in trying to understand what is going on. “Each life,” says Elizabeth, “asks the devouring of other lives for its continuance, the radical aspect of ritual sacrifice … sharing the victim was so eminently practical.”

Shirley Jackson has chosen to write this novel in as many styles as Elizabeth had personalities. The vivid, absorbing writing of “The Lottery” alternated with almost clinical reporting, diffuse dullness, and pompous reflections in the manner of Thackeray. Sometimes the book seems serious, sometimes frivolous.

The author is frequently condescending to her pitiable heroine, contemptuous of her physician, and careless with her readers. No explanation is offered for Elizabeth’s final integration. It just happens and is not at all believable.

Although the book dribbles away at the end, the first half is excellent with one remarkable section that makes for absorbing and moving reading.

. . . . . . . . . .

Analysis of We Have Always Lived in the Castle

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review in Wisconsin State Journal, June 20, 1954: Most men are at least two people, let’s say modified versions of Jekyll and Hyde. So, it’s quite appropriate that women, who are twice as complicated as men, should be allowed a four-part disharmony.

Shirley Jackson has written a novel about Elizabeth Richmond, who under hypnotic psychotherapy peels off like an artichoke into disturbing yet highly believable alter egos: Beth, Betsy, and Bess. As any writer who has attempted any such assignment will testify, there is probably no greater challenge to the psychological insight of a dramatist or novelist.

Jackson, it seems to me, has done superlatively in her minute vivisection of her complicated heroine. Writing of a contemporary young woman of upper New York State who seems to be nothing more than a shy and mousy orphan holding down a dull job at the local museum, she soon reveals that Elizabeth is at least as complicated and as fascinating as any multi-role actress.

Elizabeth has a dark secret buried deep in her subconscious — which will not be revealed in this review. Like so many other traumatic experiences from childhood, it’s actually far less sinful than it seems. Layer upon layer of protective substance has been secreted by her Ego to encase this excessive irritant until we have as an end product the flawed, discolored pearl that is Elizabeth Richmond.

When Elizabeth begins to act very strangely, she is taken by her Aunt Morgen (an earthy, sensible soul) to Dr. Wright, an old-fashioned psychiatrist who is dubious of the clap-trap and pompous terminology introduced by the Viennese neurotic, Dr. Freud.

Dr. Wright, whose literary style stems from the Victorian novelists, and who suffered from his own variety of pomposity, begins to unravel the intriguing and exasperating riddle. At varying depths of hypnosis, Elizabeth becomes at least three additional characters.

To quote Dr. Wright’s breakdown of his schizophrenic patient:

“… They were figures in a charade, my four girls: Elizabeth, the numb, the stupid, the inarticulate, but somehow enduring, since she had remained behind to carry on when the rest went under; Beth, the sweet and susceptible; Betsy the wanton and wild, and Bess, the arrogant and cheap.”

It was obvious to the wise old doctor that none of these could be allowed to assume the complete role of Elizabeth Richmond.

If you will think for a few moments of the problem confronting any psychiatrist, novelist, or dramatist faced with such a shattered personality, it will be evident that the two most likely solutions of any such dilemma are either the murder of the other “selves” by the temporarily dominant one (meaning suicide) or eventual understanding and integration.

The “obligatory scene,” as it is called in dramaturgy, cannot avoid being the head-on collision (and its resolution) between the strongest these opposing forces.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A problem goes unresolved — a skeptic’s reviewFrom the original review in The Daily Record (Long Branch, NJ), June 24, 1954: Elizabeth, Bess, Beth, and Betsy — she is the heroine, they are the heroines of this novel by the author of, among other books, The Road Through the Wall and “The Lottery.”

Twenty-year-old Elizabeth Richmond works in one of those all-purpose museums filled with assorted objetcs, mostly semi-rare, hardly ever rare. It’s a desk job, but the routine is broken by repairs made to the building, and also by the receipt of some mystifying, menacing, illiterate, and insulting letters.

In any case, however, it wouldn’t have taken much to throw her off stride, and we find her at home with her guardian and aunt, Morgen Jones, doing things about which she’s unaware, going to places she doesn’t know about, having inexplicable lapses of memory.

So Aunt Morgen calls in Dr. Wright, who proceeds to summon up the various identities battling for dominance in his patient. In his terms, they’re “Miss R,” “R1,” “R2,” “R3,” “good little girl,” “bad little girl,” and so on. One after another the Three Rs plus take over.

For the first time it seems to me, in the latest of her books, that Miss Jackson, who I would have thought could not falter, has faltered. The idea, for a fictional work, is original. But the confusion over the four-part character of Elizabeth, which remains properly confusing to Elizabeth, is too often confusing to the reader as well.

The abracadabra by which her problem is supposed to be solved does not work. An occasional phrase sounds quaint and old-hat, like something out of Wilkie Collins, and that, too, serves to muddle the author’s intent. This is bold psychological adventuring that doesn’t develop into a good novel.

More about The Bird’s Nest Reader discussion on Goodreads Maternity in Shirley Jackson’s The Bird’s Nest 746 Books. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from The Bird’s Nest by Shirley Jackson“Although she would sooner have given up thinking than eating, she resented being pushed into depriving herself of either.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I was thinking what it must feel like to be a prisoner going to die; you stand there looking at the sun and the sky and the grass and the trees, and because it’s the last time you’re going to see them they’re wonderful, full of colors you never noticed before, and bright and beautiful and terribly hard to leave behind.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Now I will be heard, and when I choose to be heard, the lowest legions of hell may turn in vain to silence me and when I choose to speak not all the winds of earth can drown my voice.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“No one ever remembers just a bad thing, they remember all around it, all that happened before it and after it, and of course, she told herself consolingly, one bad thing is probably enough.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“I reveal myself, then, at last: I am a villain, for I created wantonly, and a blackguard, for I destroyed without compassion; I have no excuse.”

. . . . . . . . . .

For a moment, staring, Betsy wanted frantically to rip herself apart, and give half to Lizzie and never be troubled again, saying take this, and take this and take this, and you can have this, and now get out of my sight, get away from my body, get away and leave me alone.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“The most important thing she had learned so far — and it was something to know, after only twelve hours – was that she need not pretend, always, to be competent or at home in a strange atmosphere. Other people, she had learned, were frequently uneasy and uncertain, lost their way or their money, were nervous at being approached by strangers or wary of officials.”

The post The Bird’s Nest by Shirley Jackson — three 1954 reviews appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 6, 2023

Charlotte Brontë’s Novels: Jane Eyre, Shirley, Villette, & The Professor

Charlotte Brontë’s novels reflected her romantic, yet deeply emotional approach to fiction writing. Coupled with her exquisite use of the English language, her brilliant novels — Jane Eyre, Shirley, and Villette — ensured her lasting stature in the world of literature.

This survey, which includes The Professor (her least-known, much-rejected work, written before Jane Eyre and published only after her death), includes links to analyses and plot summaries of these iconic works of literature.

Jane Eyre, Charlotte’s best-known novel, is the story of the title heroine’s love for the inscrutable and reclusive Mr. Rochester and her quest for independence. Shirley (1849) followed Jane Eyre two years after the latter was published. It’s the story set against the Luddite riots of the Yorkshire textile industry, 1807 to 1812.Villette (1853) is the story of Lucy Snowe, helplessly in love with Paul Emanuel. It’s a fairly autobiographical novel, based on Charlotte’s experiences in Brussels and her unrequited love for Professor Héger.The Professor (1857; posthumous), is considered a less-developed predecessor of Villette.Charlotte Brontë’s novels have in common a keen insight into human nature, and despite some questionable decisions in the realms of love, a fierce self-belief, personal integrity, and independence shared by the stories’ heroines.

Though she didn’t die quite as young as did her sisters Emily and Anne, Charlotte was not quite thirty-nine when she died of complications due to pregnancy. Who knows what more she and her sisters might have accomplish had they been granted more years to write.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Charlotte Brontë

. . . . . . . . . .

First, a little publishing history. Before attempting to publish novels, Charlotte, who seemed to be the front person for the trio of sisters, undertook the task of finding a home for a collaborative book of poems. They took masculine, or at least indeterminate, noms de plume.

Charlotte, Emily, and Anne were Currer, Ellis, and Acton respectively, all sharing the faux surname of Bell. In Charlotte’s own words:

“We had very early cherished the dream of one day becoming authors. This dream, never relinquished even when distance divided and absorbing tasks occupied us, now suddenly acquired strength and consistency: it took the character of a resolve. We agreed to arrange a small section of our poems, and, if possible, get them printed.

… The book was printed: it is scarcely known, was published and advertised at the sisters’ own expense and sold two copies) and all of it that merits to be known are the poems of Ellis Bell.”

“The book” referred to above was Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell’s Poems. It did finally did find a home and was published in 1846 to absolutely no fanfare and humiliating sales of two copies. Charlotte continues (from the Biographical Notice of Ellis and Acton Bell, 1850):

“Ill-success failed to crush us: the mere effort to succeed had given a wonderful zest to existence; it must be pursued. We each set to work on a prose tale: Ellis Bell produced Wuthering Heights, Acton Bell, Agnes Grey, and Currer Bell also wrote a narrative in one volume [this refers to The Professor].

These MSS. were perseveringly obtruded upon various publishers for the space of a year and a half; usually, their fate was an ignominious and abrupt dismissal …”

Charlotte Brontë’s “forlorn” manuscript for The Professor, submitted under her pen name, Currer Bell, was making its rounds, rejected by half a dozen London publishers. Each disappointment was crushing.

Adding to the frustration was that her sisters’ novels (Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey) found homes, even as hers didn’t. Yet Charlotte, instead of sitting idly by and waiting, worked on her next novel — Jane Eyre.

At last, a publisher, seeing promise in The Professor, requested the chance to see the pseudonymous author’s next book, which Charlotte had at the ready. the book was hastily brought out just six weeks after acceptance, and became an immediate bestseller. The Professor, meanwhile, continued to languish, and was published only after Charlotte’s death.

Read more about the Brontë sisters’ arduous path to publication.

. . . . . . . . .

Jane Eyre (1847)

Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë’s best-known novel, weaves the story of the title heroine’s love for the mysterious and reclusive Mr. Rochester with her quest for independence. First published under her pseudonym, Currer Bell, the novel was an immediate success, setting off a frenzy of speculation as to the true identity of its author.

Though considered a proto-feminist work, it also fits into the gothic novel genre due to that pesky little detail of Rochester’s mad wife locked away in an attic. Through the concise plot summary of Jane Eyre that follows, the reader will get an overview of the book that made Charlotte Brontë famous.

Jane, a young woman of unassuming background and appearance, searches for love and a sense of belonging while preserving her independence. The book sparked a fair amount of controversy when first published, which was fueled by critics and the public suspecting that “Currer Bell” (the author’s ambiguous pseudonym) was a woman.

Still, the novel was an immediate success, securing for Charlotte a place in the literary world of her time and for generations to come. Explore Charlotte Brontë’s iconic novel here:

Plot summary of Jane Eyre A Late 19th-Century Analysis Virginia Woolf’s Analysis of Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights Teaching Jane Eyre: A Professor’s Perspective Jane Eyre and I: A Love Affair for Life 39 Great Quotes from Jane Eyre Jane Eyre: The 1943 Film Based on the Novel Charlotte Brontë Before Jane Eyre. . . . . . . . .

Shirley (1849)

Shirley was Charlotte’s second published novel, still under the pseudonym Currer Bell, the mysterious author who had already achieved fame with Jane Eyre.

The lengthy novel has two female protagonists — the eponymous Shirley Keeldar and Caroline Helstone. Set in Charlotte’s native Yorkshire, it takes place against the background of the textile industry’s Luddite uprisings of 1811 and 1812.

Shirley: A Tale, as it was originally titled, is considered an example of the mid-19th century “social novel.” The social novels that emerged from that period were works of fiction dealing with themes like labor injustice, bias against women, and poverty.

Charlotte supposedly told Elizabeth Gaskell (who, not long after the former’s death would become her first biographer) that the character of Shirley was how she imagined her sister Emily might have turned out if she’d had the benefits of wealth and privilege.

More about Shirley …

Shirley by Charlotte Brontë: A Plot Summary Was Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley an Idealized Portrait of Her Sister Emily? Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley: The Power of Female Friendship Full text of Shirley on Project Gutenberg. . . . . . . . .

Villette (1853)

Jane Eyre notwithstanding, Villette is considered Charlotte Brontë’s true masterpiece. The analysis you’ll be linked to below is excerpted from Life and Works of the Sisters Brontë (1899) by Mary A. Ward, a 19th-century British novelist and literary critic. Ward wrote deeply and sensitively about the works of the Brontë sisters, and her direct language and insights still greatly inform the contemporary reader.

In her analysis, she also conveys the duress experienced by Charlotte, and the difficulties she had in writing Villette while grieving the deaths of her beloved sisters, Emily and Anne. Villette is the story of Lucy Snowe, of whom Mrs. Ward writes:

“Lucy Snowe is Jane Eyre again, the friendless girl, fighting the world as best she may, her only weapon a strong and chainless will, her constant hindrances, the passionate nature that makes her the slave of sympathy, of the first kind look or word, and the wild poetic imagination that forbids her all reconciliation with her own lot, the lot of the unbeautiful and obscure.

But though she is Jane Eyre over again there are differences, and all, it seems to me, to Lucy’s advantage. She is far more intelligible—truer to life and feeling. Morbid she is often; but Lucy Snows so placed, and so gifted, must have been morbid.”

More about Villette …

Villette by Charlotte Brontë: A Late 19th-Century Analysis Villette by Charlotte Brontë: A Portrait of Lucy Snowe. . . . . . . . .

The Professor (1857)

Though Jane Eyre was Charlotte Brontë‘s first published novel, The Professor was actually the first novel she completed. It wasn’t published until 1857, two years after her death, with her literary reputation secured.

The Professor was something of a roman à clef, based on Charlotte’s experiences while studying and teaching in Brussels.

The title character was based on Constantin Héger, the headmaster of the school, a married man with children with whom Charlotte had fallen in love. Usually no-nonsense and practical, if not entirely level-headed, she became obsessed with Héger and made something of a fool of herself — though that is a subject for a different post entirely.

When Charlotte returned to the theme of this work as a more mature writer, it grew into Villette, which, as mentioned earlier, is considered her true masterpiece.

Read more in The Professor by Charlotte Brontë: A Late 19th-Century Analysis.

The post Charlotte Brontë’s Novels: Jane Eyre, Shirley, Villette, & The Professor appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 3, 2023

Villette by Charlotte Brontë (1853): A Late 19th-Century Analysis

Presented here is a detailed analysis of Villette by Charlotte Brontë, the 1853 novel that, Jane Eyre notwithstanding, is considered her true masterpiece. It also conveys the duress experienced by Charlotte, and the difficulties she had in writing Villette, as she was grieving the deaths of her beloved sisters, Emily and Anne.

The following is excerpted from Life and Works of the Sisters Brontë (1899) by Mary A. Ward, (sometimes writing as Mrs. Humphrey Ward) a 19th-century British novelist and literary critic. Ward wrote deeply and sensitively about the works of the Brontë sisters, and her direct language and insights still greatly inform the contemporary reader.

Villette by Charlotte Brontë—an Introduction

During the year which followed the publication of Shirley, Charlotte Brontë seems to have been content to rest from literary labour—save for the touching and remarkable Preface that she contributed in the autumn of the year to the reprint of Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey—which had been happily rescued from Mr. Newby and were safe in Mr. Smith’s hands.

We hear nothing of any new projects. After the great success of Shirley and Jane Eyre, indeed, she turned back to think of the still unprinted manuscript of The Professor, and to plans of how work already done might be turned to account, now that the public knew her and the way was smoothed.

Towards the end of 1850, or in the first days of 1851, she wrote a fresh preface to The Professor, and suggested to her publishers that they should at last venture upon its publication.

They did not apparently refuse; but they advised her against the project; and as Mr. Nicholls says in a note which he added to his wife’s Preface, on the publication of The Professor after her death, she then made use of the materials in a subsequent work—Villette.

There is an interesting and, for the most part, unpublished letter to Mr. George Smith, still in existence, which throws light upon this disappointment of hers—a disappointment which to us is pure gain, since it produced Villette. In spite of her gaiety of tone, it is evident that she is sensitive in the matter, and a little wounded—

“Mr. Williams will have told you [she writes to Mr. Smith] that I have yielded with ignoble facility in the matter of The Professor. Still it may be proper to make some attempt towards dignifying that act of submission by averring that it was done ‘under protest.’

The Professor has now had the honour of being rejected nine times by the ‘Trade.’ (Three rejections go to your own share; you may affirm that you accepted it this last time, but that cannot be admitted; if it were only for the sake of symmetry and effect, I must regard this martyrized MS. as repulsed or at any rate withdrawn for the ninth time!)

Few—I flatter myself—have earned an equal distinction, and of course my feelings towards it can only be paralleled by those of a doting parent towards an idiot child. Its merits—I plainly perceive—will never be owned by anybody but Mr. Williams and me; very particular and unique must be our penetration, and I think highly of us both accordingly. You may allege that merit is not visible to the naked eye. Granted; but the smaller the commodity—the more inestimable its value.

You kindly propose to take The Professor into custody. Ah—no! His modest merit shrinks at the thought of going alone and unbefriended to a spirited publisher. Perhaps with slips of him you might light an occasional cigar—or you might remember to lose him some day—and a Cornhill functionary would gather him up and consign him to the repositories of waste paper, and thus he would prematurely find his way to the ‘butterman’ and trunkmakers.

No—I have put him by and locked him up—not indeed in my desk, where I could not tolerate the monotony of his demure quaker countenance, but in a cupboard by himself.”

In the same letter, she goes on to say—the passage has been already quoted by Mrs. Gaskell—that she must accept no tempting invitations to London, till she has ‘written a book.’ She deserves no treat, having done no work.

Early in 1851 then, having locked up The Professor as finally done with and set aside, Miss Brontë fell back once more on the material of the earlier book, holding herself free to use it again in a different and a better way.

With all the quickened and enriched faculty which these five years of labour and of fame had brought her, she returned to the scenes of her Brussels experience, and drew Villette from them as she had once drawn The Professor.

By the summer she had probably written the earlier chapters, and early in June she at last allowed herself the change and amusement of a visit to Mr. George Smith and his mother, who were then living in Gloucester Place.

Real-life incidents woven into VilletteThis visit contributed much to the growing book. In the first place the character of Graham Bretton—“Dr. John”—owed many characteristic features and details to Miss Brontë’s impressions, now renewed and completed, of her kind host and publisher, Mr. George Smith.

Mrs. Smith, Mr. George Smith’s mother, was even more closely drawn—sometimes to words and phrases which are still remembered—in the Mrs. Bretton of the book.

And further, two incidents at least of this London visit may be recognised in Villette; one connected with Thackeray’s second lecture on “The English Humourists,” to which Miss Brontë was taken by her hosts—the other a night at the theatre, when she saw Rachel act for the first time.

As to the lecture, after it was over, the great man himself came down from the platform, and making his way to the small, shy lady sitting beside Mrs. Smith, eagerly asked her “how she had liked it.” How many women would have felt the charm, the honour even, of the tribute implied! But the “very austere little person,” as Thackeray afterwards described Charlotte, thus approached, was more repelled than pleased …

With regard to the acting of the great, the “possessed” Rachel, it made as deep an impression on Charlotte Brontë, as it produced much about the same time on Matthew Arnold.

“On Saturday (she writes) I went to see Rachel; a wonderful sight—terrible as if the earth had cracked deep at your feet, and revealed a glimpse of hell. I shall never forget it. She made me shudder to the marrow of my bones; in her some fiend has certainly taken up an incarnate home. She is not a woman; she is a snake; she is the—!”

And again—

“Rachel’s acting transfixed me with wonder, enchained me with interest, and thrilled me with horror … it is scarcely human nature that she shows you; it is something wilder and worse; the feelings and fury of a fiend.”

One has only to turn from these letters to the picture of the “great actress” in Villette, who holds the theatre breathless on the night when Dr. John and his mother take Lucy Snowe to the play, to see that the passage in the book, with all its marvelous though unequal power, its mingling of high poetry with extravagance and occasional falsity of note, is a mere amplification of the letters.

It shows how profoundly the fiery dæmonic element in Miss Brontë had answered to the like gift in Rachel; and it bears testimony once more to the close affinity between her genius and those more passionate and stormy influences let loose in French culture by the romantic movement. Rachel acted the classical masterpieces; but she acted them as a romantic of the generation of “Hernani”: and it was as a romantic that she laid a fiery hand on Charlotte Brontë.

. . . . . . . . . . .

See also: Villette—a Portrait of a Woman in Shadow

. . . . . . . . . . .

After the various visits and excitements of the summer Charlotte tried to make progress with the new story, during the loneliness of the autumn at Haworth. But Haworth in those days seems to have been a poisoned place. A kind of low fever—influenza—feverish cold—were the constant plagues of the parsonage and its inmates.

The poor story-teller struggled in vain against illness and melancholy. She writes to Mrs. Gaskell of “deep dejection of spirits,” and to Mr. Williams that it is no use grumbling over hindered powers or retarded work, “for no words can make a change.”

It is a matter between Currer Bell “and his position, his faculties, and his fate.” Was it during these months of physical weakness—haunted, too, by the longing for her sisters and the memory of their deaths—that she wrote the wonderful chapters describing Lucy Snowe’s delirium of fever and misery during her lonely holidays at the pensionnat?

The imagination is at least the fruit of the experience; for the poet weaves with all that comes to his hand. But there are degrees of delicacy and nobility in the weaving. Edmond de Goncourt noted, as an artist—for the public—every detail of his brother’s death, and his own sensations. Charlotte conceived the sacred things of kinship more finely.

Those veiled and agonized passages of Shirley are all that she will tell the world of woes that are not wholly her own. But of her personal suffering, physical and mental, she is mistress, and she has turned it to poignant and lasting profit in the misery of Lucy Snowe.

A misery, of which the true measure lies not in the story of Lucy’s fevered solitude in the Rue Fossette, of her wild flight through Brussels, her confession to Père Silas, her fainting in the stormy street, but rather in the profound and touching passage which describes how Lucy, rescued by the Brettons, comforted by their friendship and at rest, yet dares not let herself claim too much from that friendship, lest, like all other claims she has ever made, it should only land her in sick disappointment and rebuff at last.

“Do not let me think of them too often, too much, too fondly,” I implored: “Let me be content with a temperate draught of the living stream: let me not run athirst, and apply passionately to its welcome waters: let me not imagine in them a sweeter taste than earth’s fountains know. Oh! would to God I may be enabled to feel enough sustained by an occasional, amicable intercourse, rare, brief, unengrossing and tranquil: quite tranquil!

Still repeating this word, I turned to my pillow; and still repeating it, I steeped that pillow with tears.”

Words so desolately, bitterly true were never penned till the spirit that conceived them had itself drunk to the lees the cup of lonely pain.

But the spring of the following year brought renewing of life and faculty. Charlotte wrote diligently, refusing to visit or be visited, till again, in June, resolution and strength gave way. Her father, too, was ill; and in July she wrote despondently to Mr. Williams as to the progress of the book.

In September, though quite unfit for concentrated effort, she was stern with herself, would not let her friend, Ellen Nussey, come—vowed, cost what it might, “to finish.” In vain. She was forced to give herself the pleasure of her friend’s company “for one reviving week.” Then she resolutely sent the kind Ellen Nussey away, and resumed her writing.

Always the same pathetic “craving for support and companionship,” as she herself described it!—and always the same steadfast will, forcing both the soul to patience, and the body to its work. No dear comrades now beside her!—with whom to share the ardors or the glooms of composition.

She writes once to Mr. Williams of her depression “and almost despair, because there is no one to read a line, or of whom to ask a counsel. Jane Eyre was not written under such circumstances, nor were two-thirds of Shirley.”

During her worst time of weakness, as she confessed to Mrs. Gaskell, “I sat in my chair day after day, the saddest memories my only company. It was a time I shall never forget. But God sent it, and it must have been for the best.”—Language that might have come from one of the pious old maids of Shirley.

How strangely its gentle Puritan note mates with the exuberant, audacious power the speaker was at that moment throwing into Villette! But both are equally characteristic, equally true. And it is perhaps in the union of this self-governing English piety, submissive, practical, a little stern, with her astonishing range and daring as an artist, that one of Charlotte Brontë’s chief spells over the English mind may be said to lie.

One more patient effort, however, in this autumn of 1852, and the book at last was done. She sent the later portion of it, trembling, to her publishers.

Mr. Smith had already given her warm praise for the first half of the story; and though both he and Mr. Williams made some natural and inevitable criticisms when the whole was in their hands, yet she had good reason to feel that substantially Cornhill was satisfied, and she herself could rest, and take pleasure—and for the writer there is none greater—in the thing done, the task fulfilled. In January 1853 she was in London correcting proofs, and on the 24th of that month the book appeared.

Villette received with “one burst of acclamation”

“Villette,” says Mrs. Gaskell, “was received with one burst of acclamation.” There was no question then among “the judicious,” and there can be still less question now, that it is the writer’s masterpiece. It has never been so widely read as Jane Eyre; and probably the majority of English readers prefer Shirley.

The narrowness of the stage on which the action passes, the foreign setting, the very fullness of poetry, of visualising force, that runs through it, like a fiery stream bathing and kindling all it touches down to the smallest detail, are repellent or tiring to the mind that has no energy of its own responsive to the energy of the writer.

But not seldom the qualities which give a book immortality are the qualities that for a time guard it from the crowd—till its bloom of fame has grown to a safe maturity, beyond injury or doubt.

“I think it much quieter than Shirley,” said Charlotte, writing to Mrs. Gaskell just before the book’s appearance. “It will not be considered pretentious,” she says, in the letter that announces the completion of the manuscript. Strange!—as though it were her chief hope that the public would receive it as the more modest offering of a tamed muse.

Did she really understand so little of what she had done? For of all criticisms that can be applied to it, none has so little relation to Villette as a criticism that goes by negatives. It is the most assertive, the most challenging of books.

From beginning to end it seems to be written in flame; one can only return to the metaphor, for there is no other that renders the main, the predominant impression. The story is, as it were, upborne by something lambent and rushing.

Masterfully written detail and characterizations

Whether it be the childhood of Paulina, or the first arrival of the desolate Lucy in Villette, or those anguished weeks of fever and nightmare which culminated in the confession to the Père Silas, or the yearning for Dr. John’s letters, or the growth, so natural, so true, of the love between Lucy and Paul Emanuel on the very ruins and ashes of Lucy’s first passion, or the inimitable scene, where Lucy, led by the “spirit in her feet,” spirit of longing, spirit of passion, flits ghost-like through the festival-city, or the last pages of dear domestic sweetness, under the shadow of parting—there is nothing in the book but shares in this all-pervading quality of swiftness, fusion, vital warmth.

And the detail is as a rule much more assured and masterly than in the two earlier books. Here and there are still a few absurdities that recall the drawing-room scenes of Jane Eyre—a few unfortunate or irrelevant digressions like the chapter Cleopatra—little failures in eye and tact that scores of inferior writers could have avoided without an effort.

But they are very few; they spoil no pleasure. And as a rule the book has not only imagination and romance, it has knowledge of life, and accuracy of social vision, in addition to all the native shrewdness, the incisive force of the early chapters of Jane Eyre.

Overview of the chief characters

Of all the characters, Dr. John no doubt is the least tangible, the least alive. Here the writer was drawing enough from reality to spoil the freedom of imagination that worked so happily in the creation of Paulina, and not enough to give to her work that astonishing and complex truth which marks the portrait of Paul Emanuel.

Dr. John occasionally reminds us of the Moores; and it is not just that he should do so; there is inconsistency and contradiction in the portrait—not much, perhaps, but enough to deprive it of the ‘passionate perfection,’ the vivid rightness that belong to all the rest.

Yet the whole picture of his second love—the subduing of the strong successful man to modesty and tremor by the sudden rise of true passion, by the gentle, all-conquering approach of the innocent and delicate Paulina—is most subtly felt, and rendered with the strokes, light and sweet and laughing, that belong to the subject.

As to Paul Emanuel, we need not repeat all that Mr. Swinburne has said; but we need not try to question, either, his place among the immortals:

“Magnificent-minded, grand-hearted, dear faulty little man!” It may be true as Mr. Leslie Stephen contends, that—in spite of his relation to the veritable M. Héger—there are in him elements of femininity, that he is not all male. But he is none the less man and living, for that; the same may be said of many of his real brethren.

And what variety, what invention, what truth, have been lavished upon him! and what a triumph to have evolved from such materials,—a schoolroom, a garden, a professor, a few lessons, conversations, walks,—so rich and sparkling a whole!

Madame Beck and Ginevra Fanshawe are in their way equally admirable. They are conceived in the tone of satire; they represent the same sharp and mordant instinct that found so much play in Shirley. But the mingled finesse and power with which they are developed is far superior to anything in Shirley; the curates are rude, rough work beside them.

Lucy SnoweAnd Lucy Snowe? Well—Lucy Snowe is Jane Eyre again, the friendless girl, fighting the world as best she may, her only weapon a strong and chainless will, her constant hindrances, the passionate nature that makes her the slave of sympathy, of the first kind look or word, and the wild poetic imagination that forbids her all reconciliation with her own lot, the lot of the unbeautiful and obscure.

But though she is Jane Eyre over again there are differences, and all, it seems to me, to Lucy’s advantage. She is far more intelligible—truer to life and feeling. Morbid she is often; but Lucy Snows so placed, and so gifted, must have been morbid.

There are some touches that displease, indeed, because it is impossible to believe in them. Lucy Snowe could never have broken down, never have appealed for mercy, never have cried “My heart will break!” before her treacherous rival, Madame Beck, in Paul Emanuel’s presence.

A reader, by virtue of the very force of the effect produced upon him by the whole creation, has a right to protest “incredible!”

No woman, least of all Lucy Snowe, could have so understood her own cause, could have so fought her own battle. But in the main nothing can be more true or masterly than the whole study of Lucy’s hungering nature, with its alternate discords and harmonies, its bitter-sweetness, its infinite possibilities for good and evil, dependent simply on whether the heart is left starved or satisfied, whether love is given or withheld.

She enters the book pale and small and self-repressed, trained in a hard school, to stern and humble ways, like Jane Eyre—like Charlotte Brontë herself. But Charlotte has given to her more of her own rich inner life, more of her own poetry and fiery distinction, than to Jane Eyre.

She is weak, but except perhaps in that one failure before Madame Beck, she is always touching, human, never to be despised. She is in love with loving when she first appears; and she loves Dr. John because he is kind and strong, and the only man she has yet seen familiarly.

What can be more natural?—or more exquisitely observed than the inevitable shipwreck of this first romance, and the inevitable anguish, so little known or understood by any one about her, that it brings with it? It passes away, like a warm day in winter, not the true spring, only its herald.

And then slowly, almost unconsciously, there grows up the real affinity, the love “venturing diffidently into life after long acquaintance, furnace-tried by pain, stamped by constancy.” The whole experience is life itself, as a woman’s heart can feel and make it.

Harriet Martineau’s criticism

Harriet Martineau’s criticism of Villette—and it is one which hurt the writer sorely—shows a singular, yet not surprising blindness. Even more sharply than in her Daily News review, she expresses it in a private letter to Miss Brontë:—

“I do not like the love,”—she says—“either the kind or the degree of it,” —and she maintains that “its prevalence in the book, and effect on the action of it,” go some way to explain and even to justify the charge of ‘coarseness’ which had been brought against the writer’s treatment of love in Jane Eyre.

The remark is curious, as pointing to the gulf between Miss Martineau’s type of culture—which alike in its strength and its weakness is that of English provincial Puritanism—and that more European and cosmopolitan type, to which, for all her strong English and Yorkshire qualities, and for all her inferiority to her critic in positive knowledge, Charlotte Brontë, as an artist, really belonged.

The truth is, of course, that it is precisely in and through her treatment of passion—mainly, no doubt, as it affects the woman’s heart and life—that she has earned and still maintains her fame. And that brings us to the larger question with which Charlotte Brontë’s triumph as an artist is very closely connected.

What may be said to be the main secret, the central cause not only of her success, but, generally, of the success of women in fiction, during the present century? In other fields of art they are still either relatively amateurs, or their performance, however good, awakens a kindly surprise. Their position is hardly assured; they are still on sufferance.

Whereas in fiction the great names of the past, within their own sphere, are the equals of all the world, accepted, discussed, analyzed, by the masculine critic, with precisely the same keenness and under the same canons as he applies to Thackeray or Stevenson, to Balzac or Loti.

The reason perhaps lies first in the fact that, whereas in all other arts they are comparatively novices and strangers, having still to find out the best way in which to appropriate traditions and methods not created by women, in the art of speech, elegant, fitting, familiar speech, women are and have long been at home.

They have practiced it for generations, they have contributed largely to its development. The arts of society and of letter-writing pass naturally into the art of the novel.

Literary predecessors and contemporaries

Madame de Sévigné and Madame du Deffand are the precursors of George Sand; they lay her foundations, and make her work possible. In the case of poetry, one might imagine, a similar process is going on, but it is not so far advanced. In proportion, however, as women’s life and culture widen, as the points of contact between them and the manifold world multiply and develop, will Parnassus open before them.

At present those delicate and noble women who have entered there look a little strange to us. Mrs. Browning, George Eliot, Emily Brontë, Marcelline Desbordes-Valmore—it is as though they had wrested something that did not belong to them, by a kind of splendid violence.

As a rule, so far, women have been poets in and through the novel-Cowper-like poets of the common life like Miss Austen, or Mrs. Gaskell, or Mrs. Oliphant; Lucretian or Virgilian observers of the many-colored web like George Eliot, or, in some phases, George Sand; romantic or lyrical artists like George Sand again, or like Charlotte and Emily Brontë. Here no one questions their citizenship; no one is astonished by the place they hold; they are here among the recognized “masters of those who know.”

Why? For, after all, women’s range of material, even in the novel, is necessarily limited. There are a hundred subjects and experiences from which their mere sex debars them. Which is all very true, but not to the point.

Love, as a woman understands itFor the one subject which they have eternally at command, which is interesting to all the world, and whereof large tracts are naturally and wholly their own, is the subject of love—love of many kinds indeed, but pre-eminently the love between man and woman. And being already free of the art and tradition of words, their position in the novel is a strong one, and their future probably very great.

But it is love as the woman understands it. And here again is their second strength. Their peculiar vision, their omissions quite as much as their assertions, make them welcome. Balzac, Flaubert, Anatole France, Paul Bourget, dissect a complex reality, half physical, half moral; they are students, psychologists, men of science first, poets afterwards.

They veil their eyes before no contributory fact, they carry scientific curiosity and veracity to the work; they must see all and they must tell all. A kind of honor seems to be involved in it—at least for the Frenchman, as also for the modern Italian and Spaniard.

On the other hand, English novels by men—with the great exceptions of Richardson in the last century, and George Meredith in this, from Fielding and Scott onwards, are not, as a rule, studies of love. They are rather studies of manners, politics, adventure.

Is it the development of the Hebraist and Puritan element in the English mind—so real, for all its attendant hypocrisies—that has debarred the modern Englishman from the foreign treatment of love, so that, with his realistic masculine instinct, he has largely turned to other things? But, after all, love still rules “the camp, the court, the grove!”