Nava Atlas's Blog, page 17

July 24, 2023

Elsa Morante, author of Arturo’s Island

Before the advent of the mysterious, best-selling author Elena Ferrante there was the provocative Italian novelist and short story writer Elsa Morante (August 18, 1912 – November 25, 1985).

Morante portrayed life’s pain and perils, but her novels also detail the power of imagination that can transport us from cruel reality. Her four novels span the entire twentieth century and illuminate the lives and inner worlds of men, women, and children.

All of her novels detail the main character’s coming of age and their fear of leaving behind the safety of childhood for the potential dangers of adulthood, and the prospect of death. Morante acknowledged the dark, overarching theme of her novels:

“The transition from fantasy to consciousness (from youth to maturity) is a tragic and fundamental experience for everyone. For me that experience came early and took the form of war: my encounter with maturity was premature and hit me with devastating force.”

Early Life

Morante began and ended her life in the culturally and historically rich city of Rome, Italy. Born in obscurity, she would leave an indelible mark on the capital city’s literary heritage. Her early life was unhappy; her parents’ marriage was deeply troubled and she later found out that her biological father was a family friend.

By the age of five, Morante was writing poems and soon began creating plays and children’s stories that were extraordinarily inventive. She was supported in her early literary efforts by her wealthy godmother and a headmistress that proclaimed her “a genius.”

At the age of eighteen, she left her traumatic home environment, determined to support herself as a writer. Growing up in poverty in pre-war Rome, Morante never attended university. Instead, she continued to educate herself for the rest of her life and later befriended Rome’s leading intellectuals.

Her eventual personal and professional triumphs are even more remarkable since, like the esteemed Maya Angelou, Morante frequently supported herself as a sex worker to survive.

. . . . . . . . . .

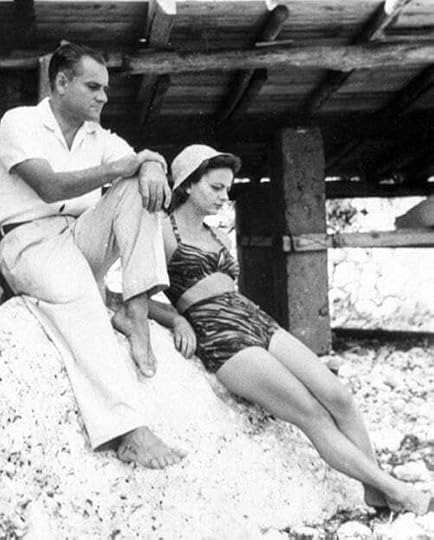

Alberto Moravia and Elsa in the 1940s

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

In 1957, at the age of twenty-five, Morante met fellow writer Alberto Moravia, who was ten years her senior. Struggling with ill health, he was slowly building a literary reputation.

He described Morante, his future wife, as “an angel fallen from heaven into the practical hell of daily living. But an angel armed with a pen.” He also described her as a person who “lived in the exceptional and not in the normal.” They married in 1941 and remained married for twenty-one years.

Lily Tuck, Morante’s biographer, described the couple’s love as “often expressed in an ambivalent, disingenuous, and belligerent fashion.” Although the fraught union eventually ended in divorce, the pair are still celebrated as Italy’s most famous literary couple.

Both Morante and Moravia were half-Jewish and were forced into hiding during World War II. Their harrowing experiences inspired works by each of them: Moravia’s Two Women (the basis of the Oscar-winning film starring Sophia Loren), and History (La Storia) which is being adapted into an eight-part miniseries.

. . . . . . . . . .

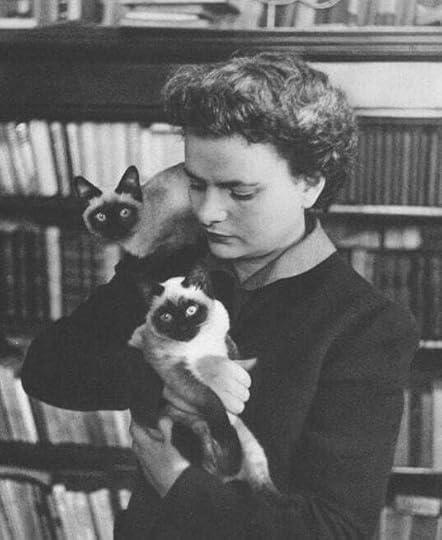

Elsa and her beloved cats

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

A known lover of cats, she was noted for her piercing, cat-like gaze, along with her style and singular beauty. Her personality was as unusual and compelling as her writing. She was emotionally volatile and could dazzle and repel those who were drawn to her in equal measure. Her biographer Lily Tuck notes that Morante possessed “a sharp and sensitive mind.”

Tuck makes special notes of her unique writing habits:

“Morante always wrote in longhand in large, black, unlined notebooks … she wrote on every other page, leaving the intervening pages blank for note and corrections … She used different colored pens and she often doodled or drew pictures of cats and stars on the side of the page.”

All her life, Morante drew eccentric people to her and was known for her loyalty and generosity. She was close friends with the controversial filmmaker and polymath and was broken-hearted by his murder, which has yet to be solved.

Perhaps influenced by her circle of friends and unconventional upbringing, she populated her novels with unconventional characters and societal outcasts. Each of her novels is highly original and utterly lacking in sentimentality.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Major worksMorante’s first novel was House of Liars (1948) which has been recently reprinted by the New York Review of Books and retitled Lies and Sorcery. A sprawling, multi-generational saga inspired by Leo Tolstoy and Marcel Proust, the plot is resolutely women-centric.

History (1974), despite its massive length and unusual structure, was one of the top international bestsellers of the 1970s, regarded as an extraordinary depiction of World War II. The plot of her final novel, Aracoeli (1982), is unusual in its psychological exploration of a son and his disturbed elderly mother.

Arturo’s Island (L’isolo di Arturo) is arguably Morante’s most popular novel, exquisitely translated most recently by Ann Goldstein, known for her translations of Elena Ferrante’s novels.

When first published in 1957, the novel ran counter to the contemporary literary trend of bleak neo-realism, but the tenderly-wrought, sun-drenched coming-of-age story immediately won over critics and audiences alike.

That year Morante won Italy’s most coveted literary award, the Strega Prize. Other famous winners include Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa‘s The Leopard and Umberto Eco‘s The Name of the Rose. Arturo’s Island was adapted as a film in 1962.

Later life and death

After a slow and painful decline due to hydroencephalitis, Morante passed away on November 25, 1985 at the age of seventy-three. A newspaper headline announcing her death read “GOOD-BYE ELSA OF A THOUSAND SPELLS.”

Her friend Cesare Garboli declared that “There does not exist in all of Italian literature a writer who is more loved and hated, more read and more ignored, than Morante.” Over time, her reputation has steadily grown while Moravia’s has declined.

Morante acknowledged that she was a deeply wounded, complicated, and unpredictable woman, and in her writing she set out to create a form of femininity that resisted conventional standards. Her female characters are anguished, passionate, and determined to survive and thrive in a man’s world. All her life Morante defied the strictures of Fascism and the crushing patriarchy of her time.

Morante’s novels and short stories have much to offer the reader, particularly for their originality and mythical quality. Tuck writes: “She was a passionate, deeply spiritual person who despised authority under any form … She was a serious artist who wanted, through her work, to change the world, even as she knew quite well that it was impossible.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Katharine Armbrester, who graduated from the MFA creative writing program at the Mississippi University for Women in 2022. She is a devotee of Flannery O’Connor and Margaret Atwood, and she loves periodicals, history, and writing.

More about Elsa MoranteFurther reading and sources

Woman of Rome: A Life of Elsa Morante by Lily TuckThe Lives of the Wives: Five Literary Marriages by Carmela CiuaruLiterary Landscapes, edited by John Sutherland Jewish Women’s ArchiveNovels

Diario 1938 (1938)Menzogna e sortilegio (1948) – House of Liars, translated by Adrienne Foulke, 1951;and as Lies and Sorcery, translated by Jenny McPhee, 2023L’isola di Arturo (1957) – Arturo’s Island, translated by Isabel Quigly, 1959;

translated by Ann Goldstein, 2019La storia (1974) – History: A Novel, translated by William Weaver, 1977Aracoeli (1982) – Aracoeli, translated by William Weaver, 1984

Short story collections

Il gioco segreto (1941)Le straordinarie avventure di Caterì dalla Trecciolina (1942)Lo scialle andaluso (1963)Racconti dimenticati (1937–1947)Aneddoti infantili (1939–1940)The post Elsa Morante, author of Arturo’s Island appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 22, 2023

Alliance of Sisters: The Complex Relationship of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell

Sisters Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell collaborated artistically, influenced each other’s work, shared friends, and were central figures in the Bloomsbury Group. They were also at the heart of one another’s family stories.

Their relationship was a deep and unusual one: powerful, interdependent, with unsettling periods of jealousy and hostility, yet characterized by mutual support and devotion throughout their lives. Virginia was one of the most influential English authors of the twentieth century; Vanessa was a noted painter.

The sisters lived close to one another until Virginia’s death in 1941. Infusing both her writing and her life, it was the relationship that influenced Virginia more than any other except that with her husband, Leonard Woolf.

Photo above right, Virginia and Vanessa Bell playing cricket in 1894 (photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).

. . . . . . . . .

Virginia and her mother, Julia Stephen, 1884

(photo: Wikimedia Commons)

. . . . . . . . .

Virginia Woolf (1882 – 1941), born Adeline Virginia Stephen, and her older sister Vanessa Bell (1879 – 1961), born Vanessa Stephen, grew up in Hyde Park Gate, Westminster, London.

Virginia, in later life, would often recall memory in “scenes,” though she couldn’t do so with Vanessa: “My relation with Vanessa,” she wrote, “has been too deep for “scenes.”

One exception, however, was her first memory of her older sister, in which she recalled meeting Vanessa under the nursery table in the family home. Vanessa asked her, “Have black cats got tails?” to which Virginia replied, “‘NO,’ and was proud because she had asked me a question. Then we roamed off again into that vast space.”

As small children, she and Vanessa slept and bathed together. Vanessa, already the “little mother” though she was only three years older than Virginia, rubbed her with scented creams and put her to bed.

The closeness of their childhood relationship was perhaps inevitable. Their father, Leslie Stephen, was an intellectual and a voracious reader and writer. He had little time for children, especially for Vanessa, who showed scant interest in literature. Their mother, Julia Stephen, was worn thin by the demands of both her family and philanthropic work; the young sisters very rarely had time alone with her.

Virginia and Vanessa had two brothers, two half-brothers, and a half-sister and sisters (it was a second marriage for both parents). A constant atmosphere of rivalry discouraged any real closeness. The exception was their brother Thoby, with whom both sisters shared an affectionate bond.

They also both adored St. Ives in Cornwall, where the family spent thirteen summers until Julia’s untimely death in 1895, and the memories of it would both enchant and haunt them for years afterward.

It was during these nursery years — or so both sisters later claimed — that they each decided what they were going to be: Virginia would be the writer, Vanessa the painter. Vanessa later wrote, “It was a lucky arrangement, for it meant we went our own ways and one source of jealousy at any rate was absent.”

Unsurprisingly, this wasn’t always true. There was often a slight sense of jealous longing between the sisters, particularly from Vanessa, who felt as if she came off unfavorably compared to her sister.

She wrote to Virginia in 1908 that she felt “painfully incompetent to write letters and becoming more & more so as I see the growing strength of the exquisite literary atmosphere distilled by you,” while Virginia acknowledged that “Nessa has all that I should like to have.”

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

“An alliance so knit together”In the years following their mother’s death, both sisters were subject to sexual abuse by their half-brother George Duckworth. Virginia was relatively open about the damage it caused, both in her diary and in letters to friends, whereas Vanessa never spoke of it.

Later Virginia would blame her second and most serious breakdown (in 1904) on the family that was “tangled and matted with emotion” and maintained that her only savior was her sister: “Where should I have been if it hadn’t been for you, when Hyde Park Gate was at its worst?”

During “the worst,” Virginia and Vanessa “had an alliance that was so knit together that everything … was seen from the same angle; and took its shape from our own vantage point.”

Already preoccupied with art and literature, neither sister had much time for the social efforts that they had to make in the stifling upper-middle classes to which the Stephens belonged, and they resented the traditional expectations that were placed upon them.

They shared a firm belief that they could one day live in a different world, where they would be free to create a life of books and painting and friendship, without the constraints of the lingering Victorian-era expectations which were thrust upon them at Hyde Park Gate.

. . . . . . . . .

Vanessa in 1902 (photo: Wikimedia Commons)

. . . . . . . . .

Their father’s illness and death in February 1904 caused a divergence between them that Virginia felt especially strongly. She had always been closer to their father than Vanessa, enjoying a rapport with him that Vanessa never had. He appreciated her intellect and talents for reading and writing (despite his Victorian belief that women were meant only for the home), whereas he never understood Vanessa’s passion for painting and art.

It was largely Vanessa who had taken on the burden of his emotional demands and of helping to run the household after their mother’s death. When he died, Vanessa felt an unequivocal relief that Virginia couldn’t share. While Vanessa made almost immediate plans to clear out the family home and move house, to travel and to paint, Virginia was much less able to simply walk away.

It was the first time in her life that she felt she couldn’t confide in Vanessa. Instead, she confided some of her feelings to a family friend, Violet Dickinson: “You can’t think what a relief it is to have someone — that is you, because there isn’t anyone else to talk to.”

Later, in her 1928 diary, Virginia revisited some of the turmoil she had felt and the tangled feelings that emerged from this time, acknowledging that, “His life would have entirely ended mine. What would have happened? No writing, no books — inconceivable.”

She joined Vanessa in traveling — first to Italy, and then to Venice and France, returning home via Paris — but didn’t enjoy the experience. She found it noisy and irritating, and resented being unable to speak the language, feelings that were no doubt exacerbated by Vanessa’s exuberant joy at the art, sights, and newfound freedom.

By May, when they returned to London, Virginia was experiencing one of the worst periods of mental breakdown she would ever suffer. Over the next three months, she became suicidal, violent, and stubborn beyond reason, and suffered from hallucinations. The bulk of her care, outside of the nurses that became necessary, fell to Vanessa.

At this time, Vanessa was also arranging a move from Hyde Park Gate to Gordon Square in Bloomsbury, and when Virginia was deemed well enough, she was relieved to join her sister — along with their brother Thoby and his friends from Cambridge — in this new life that seemed so far removed from the old.

Early days of Bloomsbury; inevitability of marriage

In spring 1905 the sisters established regular “Thursday evenings,” on which Thoby’s friends from Cambridge were invited to drop in informally after dinner. This, Virginia believed, was the seed of the Bloomsbury group.

It made a refreshing change in that the intellectual conversation not only included both her and Vanessa, but placed them at the heart of it. The group included their younger brother Adrian, Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, Maynard Keynes, Leonard Woolf, Desmond and Molly MacCarthy, and Roger Fry.

In these early years of freedom, the two sisters presented such a unified front that when Leonard Woolf wrote in his autobiography of first meeting them together, he couldn’t help referring to the two of them as one entity:

“It was almost impossible for a man not to fall in love with them, and I think that I did at once.” Much later, in a 1930 letter to Ethel Smyth, Virginia would write, “He [Leonard] saw me it is true; and thought me an odd fish; and went off the next day to Ceylon, with a vague romance about us both.”

Indeed, it was Vanessa that Leonard first hoped to marry, but on hearing that Clive Bell had asked her and been accepted, Leonard switched his attention to Virginia instead. Similarly, Clive Bell had initially found himself drawn more to Virginia than to Vanessa.

With this new life, they had created a quasi-family. At the center of this group of engaging friends, Vanessa was like the doting mother and Virginia was the brilliant child.

Virginia saw no need for marriage at all, and was upset when Vanessa talked of its inevitability: she could feel “a horrible necessity impending over us; a fate would descend and snatch us apart just as we had achieved freedom and happiness.” It was, however, Vanessa who she feared losing more than anything.

Vanessa’s marriage to Clive Bell

In the summer of 1905, Clive Bell proposed to Vanessa. She immediately declined, saying to Virginia that she was “conceited enough to believe that my family wants me,” and to Clive that his proposal had come as a surprise because she had “always taken it for granted that you thought me rather stupid and quite illiterate …”

Clive persisted through the following year, but it was only after the sudden and tragic death of their brother Thoby in November 1906 that Vanessa changed her mind and accepted. This double loss, as she felt it to be, struck Virginia hard. She couldn’t even admit to Thoby’s death to family friend Violet Dickinson and kept up a pretense of his recovery for two months.

Of Vanessa’s engagement, she wrote, “I shall want all my sweetness to gild Nessa’s happiness. It does seem strange and intolerable sometimes …” A frank and fairly astonishing letter, written on the eve of Vanessa’s wedding, shows how possessive and jealous Virginia felt:

“We have been your humble Beasts since we first left our Isles, which is before we can remember, and during that time we have wooed you and sung many songs of winter and summer and autumn in the hope that thus enchanted you would condescend one day to marry us. But as we no longer expect this honour we entreat that you keep us still for your lovers, should you have need of such, and in that capacity we promise to abide well content always adoring you now as before.”

“A most amorous intercourse” — Clive, Vanessa, and Virginia

While the marriage had initially been a very happy one, the birth of their first son Julian, on February 4, 1908, marked the beginning of a detachment in Vanessa’s relationship with Clive. He struggled with fatherhood and couldn’t bear the noise, the disruption, and the deflection of attention from himself.

Virginia, too, felt displaced by and jealous of the new arrival, writing in 1908 to Violet Dickinson, “Nessa comes tomorrow — what one calls Nessa: but it means husband and baby, and of sister there is less than there used to be.”

Still, the letters that she wrote to Vanessa during this time are some of the most passionate and admiring that she ever wrote, fueled not only by jealousy but by Vanessa’s immediate blossoming into marriage and motherhood — a state that Virginia both longed for and dreaded for herself.

Vanessa wrote, “I read your letters over and decided with Clive that when they are published without their answers people will certainly think that we had a most amorous intercourse. They read more like love-letters than anything else…”

In the spring of 1908, against this heightened emotional backdrop and the preoccupation of Vanessa with the new baby, an affair of sorts began between Clive and Virginia — a sensual, intellectual flirtation that never became physical, but that still caused a great deal of pain to all involved.

While Clive was, and always had been, attracted to Virginia, Virginia herself was effectively attempting to seduce her sister through her husband, beseeching him in a letter, “Kiss her, most passionately, in all her private places … and tell her — what new thing is there to tell her? How fond I am of her husband?”

At the time Virginia was also working intensely on the novel that would become The Voyage Out, and Clive provided her with invaluable criticism, support, and encouragement. While vital for Virginia, this intellectual intimacy excluded Vanessa, who felt largely cut off from the worlds of art and literature by the demands of domesticity and motherhood.

Vanessa said nothing of how hurt and angry she felt but appeared to be accepting and understanding of the attraction Virginia held for Clive. Only much later did she come close to admitting her jealousy, while for Virginia, the affair would have lasting consequences: in 1952, she wrote to her friend Gwen Reverat that “my affair with Clive and Nessa … turned more of a knife in me that anything else has ever done.”

The affair continued intermittently until Vanessa fell in love with art critic and painter Roger Fry in 1911, and Virginia married Leonard Woolf the year after.

. . . . . . . . . .

Leonard and Virginia, 1912

. . . . . . . . . .

When Virginia became engaged to Leonard Woolf, Vanessa experienced some of what Virginia had gone through when she became engaged to Clive. She wrote to Virginia that “although it was somehow so bewildering and upsetting when I did actually see you & Leonard together, I do now feel quite happy for you.”

It was Vanessa to whom both Leonard and Virginia turned when the subject of children was raised (despite the sexual side of the marriage not being what either had hoped for). Leonard maintained that it was a bad idea, given what he saw as Virginia’s inclination towards mental instability, while she was hopeful; Vanessa could see no reason why not.

Leonard prevailed, and twenty years later Virginia would write to a friend, “I’m always angry at myself for not having forced Leonard to take the risk in spite of doctors.”

That Vanessa had three children and a bustling family life at Charleston in Sussex would later be a source of both envy and contentment for Virginia.

In her 1928 diary, while sitting in the garden at Rodmell (her and Leonard’s house close to Charleston), she wrote, “Children playing: yes, & interrupting me; yes, & I have no children of my own; & Nessa has & yet I don’t want them any more, since my ideas so possess me & I detest more & more interruption …”

Virginia grew fond of Vanessa’s children, particularly Angelica who was born in 1918. She later admitted to Vanessa that “Angelica has become essential to me. An awful kind of spurious maternal feeling has taken possession of me.”

The Hogarth PressWhen Virginia and Leonard first established The Hogarth Press in 1917, Vanessa was interested in the possibilities for artists from her sister’s new venture. She suggested that they should publish a book of woodcuts by herself, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant. She clashed with Leonard, however, over the extent of artistic control, and the book never came to be.

Two years later, there was also friction over the printing of Vanessa’s woodcuts that were used as a frontispiece and endpaper for Virginia’s story, Kew Gardens. Vanessa felt that the printing was badly executed and didn’t hesitate to say so.

With her dependence on Vanessa’s good opinion, this threw Virginia into a state of nervous depression that took some weeks to lift. Despite this rocky beginning, Vanessa went on to design every dust jacket for Virginia’s books.

Mutual respect and inspiration

Throughout their lives, and despite intermittent jealousies and petty squabbles, the sisters were steadfast in their support for and admiration of each other’s work. They both took their art seriously, and each was a constant source of inspiration to the other.

Virginia created version after version of her sister in letters and diaries and as characters in her fiction: Helen Ambrose in The Voyage Out, Katharine Hilbery in Night and Day, Mrs Ramsay in To the Lighthouse, Susan in The Waves, and Maggie Pargiter in The Years.

It was always Vanessa whose approval mattered most to Virginia, and after the publication of The Waves, she wrote, “Nobody except Leonard matters to me as you matter, and nothing would ever make up for it if you didn’t like what I did … I always feel I’m writing more for you than for anybody.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West’s

Love Affair & Friendship

. . . . . . . . . .

Leonard was a stable force in Virginia’s life; a source of solid love and affection and of much of the maternal care that she had always sought from Vanessa. Romantic passion, however, was reserved for her relationships with women.

She never excluded her sister explicitly from this. When they were both nearly, fifty she wrote to Vanessa, “With you I am deeply passionately unrequitedly in love, and thank goodness your beauty is ruined, for my incestuous feeling may then be cooled — yet it has survived half a century of indifference..”

Virginia also admitted that her attraction to Vita Sackville-West, which flared into a brief affair in 1925, then cooled into a lasting friendship, was partly because Vita reminded her in some ways of Vanessa.

Vanessa once more became jealous and felt left out: she wrote to Virginia in 1926, “Give my humble respects to Vita, who treats me as an Arab Steed looking from the corner of its eye on some long-eared mule — but then you do your best to stir up jealousy between us, so what can one expect?”

She was also jealous of the inspiration Vita seemed to give Virginia in her writing. Having been the central inspiration for characters in The Voyage Out, Night and Day, and To the Lighthouse, she now had to contend with the figure behind Orlando. “Don’t expend all your energies in letter-writing on her,” she wrote pettily to Virginia, “I consider I have first claim.”

Even Vita, however, could not be a real challenge for Vanessa’s preeminence in Virginia’s life. When Vita was abroad for four months, Virginia admitted that “I miss her, I suppose, not very intimately.” When Vanessa returned home from the South of France, however, Virginia wrote, “Mercifully, Nessa is back. My earth is watered again.”

“Madness is terrific”: the boundaries of emotion

While the sisters divided roles for themselves in life and in art, so they did in the realm of sanity. Virginia was cast as the unstable sister, a stereotype that has formed a great deal of her posthumous legacy and which she played up to during her lifetime.

In 1930, she wrote to Ethel Smyth, “Madness is terrific I can assure you, and not to be sniffed at; and in its lava I still find most of the things I write about.”

This left Vanessa, who was naturally disinclined to emotional displays, to be cast as the sane and stable one. It was not an entirely truthful separation, in that Vanessa did indeed experience strong emotion but was adept at concealing it. Even Leonard, in the early days of his courtship of Virginia, recognized that “the tranquility was to some extent superficial …”

The only time Vanessa fully allowed the mask to slip was at the death of her son Julian in the Spanish Civil War. Then, the sisters experienced a role reversal of the most extreme sort, with Vanessa incapacitated for several weeks, and Virginia caring for her nearly around the clock.

When she was largely recovered, Vanessa was unable to tell Virginia just how vital her care had been. Instead, she turned to Vita to tell Virginia on her behalf: “I cannot ever say how Virginia has helped me. Perhaps some day, not now, you will be able to tell her it’s true.”

. . . . . . . . . .

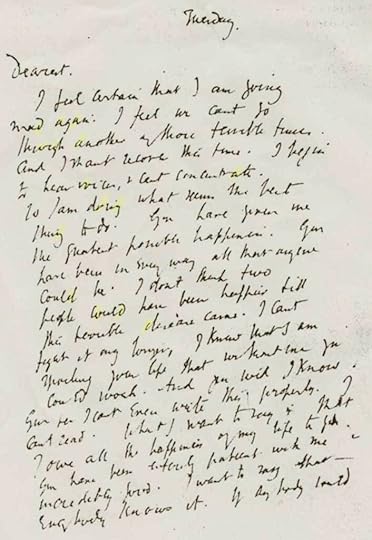

Virginia’s suicide letter to Leonard

. . . . . . . . . .

In 1941, Virginia began to suffer from the kind of dark depression that she knew was associated with complete mental breakdown.

With the terrors of war never far away, her despair over being able to write, and being “buried” at the country house in Rodmell (and unable to get to London), her mind returned obsessively to the idea of family — to her parents, her dead brother Thoby, the children she never had, and her sister. Concerned, Vanessa wrote to her,

“You must not go and get ill just now. What shall we do when we’re invaded if you are a helpless invalid? … What should I have done all these last 3 years if you hadn’t been able to keep me alive and cheerful. You don’t know how much I depend on you.”

But even this plea from her beloved sister couldn’t prevent Virginia’s determination to avoid the plunge into madness that she so feared. The only way she could see to do that was to end her life.

She wrote two letters, one to Leonard and one to Vanessa. To Vanessa, she wrote, “If I could I would tell you what you and the children have meant to me. I think you know.” The letters were left together in the house on March 28, 1941, before Virginia walked the short distance to the River Ouse.

It was the Woolf’s gardener who telephoned Vanessa to tell her that Virginia was missing and feared drowned. She arrived at Rodmell to find Leonard “amazingly self-controlled and calm.” She, too, displayed her usual stoicism, saying that “Now we can only wait until the first horrors are over which somehow make it impossible to feel much.”

Vanessa didn’t attend Virginia’s cremation, which Leonard arranged and attended alone. He did, however, ask Vanessa’s advice about a memorial to Virginia:

“Leonard told me that there are two great elms at Rodmell which she always called Leonard and Virginia … He is going to bury her ashes under one and have a tablet on the tree with a quotation … He was afraid I’d think him sentimental but it seems so appropriate that I could only think it right.”

Vanessa continued to live at Charleston for the rest of her life, and also continued her working relationship with the Hogarth Press by designing the jackets for the books by Virginia that were published posthumously.

Vanessa Bell died at Charleston on April 7, 1961, nearly twenty years to the day since her sister walked into the River Ouse.

Further reading

Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell: A Very Close Conspiracy by Jane Dunn (2000)Virginia Woolf by Hermione Lee (1997)Virginia Woolf: Selected Diaries, edited by Anne Olivier Bell (2008)Virginia Woolf: Selected Letters, edited by Joanne Trautmann Banks (2008)Vanessa Bell: Portrait of the Bloomsbury Artist by Frances Spalding, Tauris Parke (2018)Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

The post Alliance of Sisters: The Complex Relationship of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 21, 2023

10 Unforgettable Books by South African Women Authors

Presented here is a survey of ten unforgettable books by South African women authors, including novels, narrative nonfiction, poetry, and more.

From The Story of an African Farm set in the nineteenth century to Circles in a Forest from the Knysna forests, South Africa has long been an interesting place for authors to situate fiction and nonfiction.

Rich with history and exploring both the good and evil in humanity, works from Southern Africa can take the reader on an unforgettable journey through space and time.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Story of an African Farmby Olive Schreiner (1883)

The Story of an African Farm is an intimate portrayal of family life on a South African farm in the 19th century. First published under the pseudonym Ralph Iron, Olive Schreiner’s debut novel explores themes of Victorian culture intertwined with the South African experience.

Olive Schreiner (1855 – 1920) applied to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, but became a writer when her health prevented her from continuing medical studies. She used her personal experience spent as a governess on several South African farms to inform The Story of an African Farm.

Subtle themes throughout the book include portrayals of intimate relationships and feminism, two subjects that were especially controversial for women of its time. A near-epic, the original novel spanned 644 pages, over two volumes.

More about The Story of an African Farm.

. . . . . . . . . . .

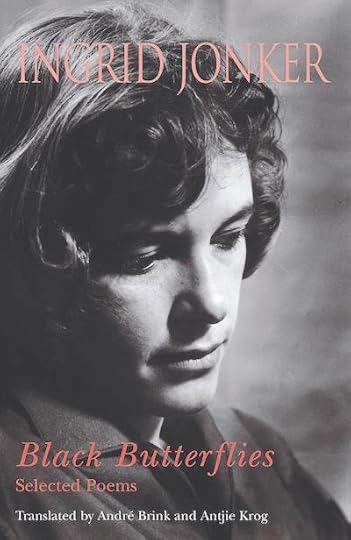

Black Butterflies: Selected Poemsby Ingrid Jonker (2007)

Black Butterflies collects some of author and anti-apartheid activist Ingrid Jonker’s (1933 – 1965) selected poems, translated into English from the Afrikaans language original.

Partially edited by her Sixtiers-counterparts Jack Cope and Andre P. Brink with Antije Krog and Ingrid de Kok, Black Butterflies is kept as truthful as translation could get. Considered one of the most important though tragic South African poets, Jonker often drew comparisons to Sylvia Plath.

Most poems in this volume are taken from her second collection, Smoke and Ocre (Rook en Oker), published in 1963. It includes one of her most internationally famous poems, The child who was shot dead by soldiers at Nyanga.

More about Black Butterflies.

. . . . . . . . . . .

And They Didn’t Die by Lauretta Ngcobo (1990)

And They Didn’t Die is a novel by South African activist and author Lauretta Ngcobo (1931 – 2015). Born in Ixopo, she attended Inanda Seminary School in Kwazulu-Natal (Durban) and went on to become a teacher, activist, and writer.

With a storyline set in 1950s South Africa, the book has become famous as a portrayal of women who lived under the Apartheid regime.

Ngcobo spent the years 1963 to 1994 in exile, though both her major novels were to be set in her home country. After her period in exile, she returned to Durban with her family and lived there until her death in 2015.

More about And They Didn’t Die.

. . . . . . . . . . .

We’re Not All Like Thatby Jeanne Goosen (1990)

Jeanne Goosen (1938 – 2020) was a prominent Afrikaans poet and academic. She debuted her first poetry collection `n Uil vlieg weg (An owl flies away) in 1971.

We’re not all like that was first published in Afrikaans, and translated into English by author Andre P. Brink. The novel explores the theme of poverty. Portraying an average white family and set in the 1950s, it was a topic that until then had been relatively unexplored in South African fiction.

Also notable is that the book is told from the perspective of Gertie, the youngest family member. Goosen credited reading Crime & Punishment as a teenager as her initial motivation to write. She later studied radiography and branched out into the formal study of piano playing.

More about We’re not all like that.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Pickup by Nadine Gordimer (2001)

One of the most acclaimed South African authors, Nadine Gordimer (1923 – 2014) won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1991. The Pickup was chosen as the winner of the 2002 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for the Best Book from Africa.

The Pickup is a complex love story between Julie, a South African, and Abdu, an immigrant from an Arab country that remains unnamed throughout the book. The novel is divided into two parts, with the first set in South Africa. The second part takes Julie into a country where she becomes the outsider.

Gordimer’s work explored themes of alienation, oppression, and other moral issues displayed through her fiction and characters.

She was a political activist for most of her adult life and was one of the first people Nelson Mandela reportedly asked to see upon his 1990 release from imprisonment. Her last novel, No Time Like the Present, was published in 2012.

More about The Pickup.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Long Journey of Poppie Nongenaby Elsa Joubert (1978, translated 1980)

The long journey of Poppie Nongena was first published in Afrikaans (1978) and translated into English two years later. The book tells the story of the title character, Poppie, as she finds her way through South Africa after being classified as an illegal citizen due to the death of her husband.

The book documents the character’s travels, from when she is uprooted from Lambert’s Bay to a safer destination. The story was also adapted into a stage production and later a movie titled Poppie Nongena.

Elsa Joubert (1922 – 2020) was a full-time author who documented her travel experiences from Uganda to Western Europe for several of her nonfiction books.

More about The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Circles in a Forestby Dalene Matthee (1984)

Dalene Matthee (1938 – 2005) is one of the most widely translated authors to emerge from South Africa, with her Forest Books series arguably the best known. Circles in a Forest explores the theme of nature conservation from the viewpoint of the inhabitants of the Knysna Forest.

Circles in a Forest focused on the Knysna woodcutters and the impact surrounding their exploitation of the environment and Knysna elephants.

Matthee followed Circles in a Forest with Fiela’s Child, The Mulberry Forest, and Dreamforest (later republished as Karoelina’s Forest). She was meticulous about translating the initial versions of her novels into English and did most of her own research for her novels. Circles in a Forest was first adapted to film in 1989.

More about Circles in a Forest.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Between Two Worlds by Miriam Tlali (1975)

Between Two Worlds is a novel by Miriam Tlali (1933 – 2017), one of the first Black female authors to publish an English-language novel in Southern Africa. In this novel, race relationships are explored, as told from the perspective of Muriel, a bookkeeper who works in a store selling electronics.

The story explores interactions between the oppressed Muriel, who shares her world with the mostly white customers. Between Two Worlds is an honest and sensitive portrayal of daily life in 1960s South Africa.

While the novel doesn’t focus on atrocities and violence, it also doesn’t shy away from a candid portrayal of bygone times that many people still remember.

More about Between Two Worlds.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Cape Malay Cookbook by Faldela Williams (1988)

The Cape Malay Cookbook by South African author and chef Faldela Williams (1952 – 2014) is considered one of the first truly comprehensive guides to Cape Malay recipes, featuring a mixture of traditional recipes that were mostly unknown until the book’s publication.

Williams was born in District Six and began her career in cuisine as a wedding caterer. Later, she realized that her recipes could be an inspiration to others for years to come.

She wrote two more cookbooks — More Cape Malay Cooking (1991) and The Cape Malay Illustrated Cookbook (2007).

More about The Cape Malay Cookbook.

. . . . . . . . . . .

My 100 Favourite Herbs by Margaret Roberts (2018)

Margaret Roberts (1937 – 2017) was known in South Africa as an author and herbalist. She wrote more than forty books about herbs and their practical use. She licensed her name to the Margaret Roberts Herbal Centre, which continues to honor her memory.

My 100 Favourite Herbs is a clear, comprehensive look at her personal favourites in the garden — with more about how to plant and care for each. She wrote about plants with the ardor of a romance author, in love with nature.

Roberts was also one of the foremost lavender experts and cultivated the Margaret Roberts lavender from South Africa.

More about My 100 Favourite Herbs.

Contributed by Alex J. Coyne, a journalist, author and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

The post 10 Unforgettable Books by South African Women Authors appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 17, 2023

Ingrid Jonker, South African Poet and Anti-Apartheid Activist

Ingrid Jonker (September 19, 1933 – July 19, 1965) was a South African poet and founder of the emerging counterculture literary movement. The daughter of a Member of Parliament for the National Party, her views and work strongly opposed the apartheid government of the time.

Jonker has been compared to some of the most iconic modern female artists and poets, including Sylvia Plath. Her poetry, written in Afrikaans, has been more recently translated into English, as well as German, Dutch, French, Polish, Hindi, and other languages.

Jonker’s poem, “The child who was shot dead by soldiers at Nyanga” was recited by Nelson Mandela on May 24, 1994, signifying the past impact and end of the Apartheid-regime.

The poem begins:

The child is not dead

the child raises his fists against his mother

who screams Africa screams the smell

of freedom and heather

in the locations of the heart under siege

(Translation: Antjie Krog & André Brink, from Black Butterflies, published by Human & Rousseau, Cape Town, 2007. Read the rest of the poem here.)

Early life and literary beginnings

Ingrid Jonker was born in Douglas, Eastern Cape, South Africa to Beatrice Cilliers and Abraham Jonker, a Member of Parliament for the National Party. She had one sister, Anna Jonker.

After being accused of an affair, Beatrice left with the children and stayed on a neighboring farm. Ingrid and Anna would spend their childhoods moving between farms owned by her grandfather, Fanie Cilliers.

Her grandfather’s death brought more change for the family, and they moved again, from Strand to Gordon’s Bay. In 1944, her mother died from cancer, and Ingrid would spend time between her father’s home and a local boarding house.

Ingrid began to find her own way from 1951, asking to leave the family home in Plumstead. She wrote from a young age, sending her first collected poetry manuscript to NB Publishers at sixteen.

Poet and literary professor D.J. Opperman noticed her work, encouraging her to press ahead with her writing even when the collection was rejected for publication.

Shortly after her move from Plumstead, she found employment at a publishing house in Cape Town, though continued to write and correspond with other literary minds.

. . . . . . . . . .

Jonker in 1956

. . . . . . . . . .

Ingrid married Pieter Venter in 1956, the same year as the publication of her debut poetry collection entitled Ontvlugting (Escape). Their daughter, Simone Celliers-Jonker, was born in December, 1957. The couple separated soon after.

In the early 1960s, Ingrid would join the Sixtiers literary movement (‘Sestigers’): a counterculture of authors, poets, and others who embraced alternative values – and rejected the Apartheid system of the time. Rook en Oker (Smoke and Ochre), her second collection of poems, published in 1963.

Ingrid’s relationship with her father, who was still a supporter of arcane values, would remain under great strain until her death.

Death at an early age

Ingrid Jonker died on July 19, 1965 by suicide, walking into the ocean at Three Anchor Bay, Cape Town. She was not quite thirty-two.

While a formal, church-run funeral was held on 22 July, her closest friends held a private memorial event three days after (July 25) that allowed for her poetry to be read against the banning orders of the time.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Posthumous acclaim and legacyMost of Ingrid Jonker’s critical acclaim would take place years after her death. Remaining friends and associates would institute the Ingrid Jonker Prize for debut poetry in Afrikaans and English. The Collected Works of Ingrid Jonker, including one of her plays, was published in 1975.

As mentioned earlier, “The child who was shot dead by soldiers at Nyanga” was recited by Nelson Mandela on 24 May 1994, signifying the past impact and end of the Apartheid-regime.

In 2004, the South African government posthumously awarded Ingrid with the Order of Ikhamanga for excellence in arts, culture, literature, music, journalism and sport.

Several works have been produced about her life and death, including a 2001 documentary and the film Black Butterfly in 2011.

Contributed by Alex J. Coyne, a journalist, author and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo and the weird. His features, posts, articles and interviews have been published in People Magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

More about Ingrid JonkerMajor Works

Ontvlugting (Escape), 1956Rook en Oker (Smoke and Ochre), 1963Collected Works, 1975Poems by Ingrid Jonker

Several poems by Ingrid Jonker translated into English are available online:

“You Have Tricked Me” “Daisies in Namaqualand” “ Little Grain of Sand” Several Jonker poems in English translation on AllPoetry.comMore Information

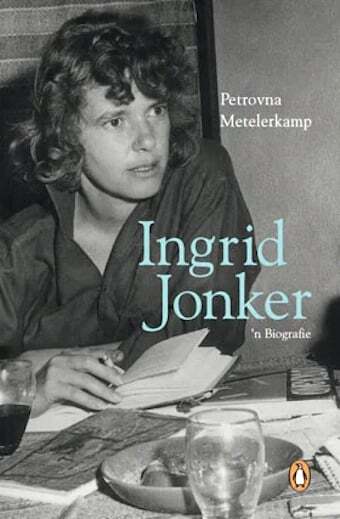

Official Website South African Government: Ingrid Jonker South African History Online SA History Ingrid Jonker: A Biography (Petrovna Metelerkamp)Learn more about classic women poets and their poetry.

The post Ingrid Jonker, South African Poet and Anti-Apartheid Activist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 16, 2023

The Blue Castle by L.M. Montgomery — Two 1926 Reviews

L.M. Montgomery (1874 – 1942), the Canadian author best known for her Anne of Green Gables and Emily of New Moon series, wrote just two novels intended for adults — A Tangled Web (1931) and The Blue Castle (1926). Presented here are two reviews from the year of the book’s initial publication.

Now in the public domain, The Blue Castle has been published and republished in numerous editions in print and audio. While the book may not be as beloved as Montgomery’s more famous series, it did make its mark.

For the first time, the story is being adapted for film. It’s hard to say when (or ultimately if) it will be released, but here’s the news of its potential adaptation.

The story’s heroine, Valancy Stirling, is considered a hopeless old maid at age twenty-nine. Infantilized and controlled by her prim and eccentric family, she takes refuge in daydreams of her “Blue Castle” and reading nature books by an author known as John Foster.

When Valancy is diagnosed with a heart ailment that she is told will kill her within a year, she suddenly feels liberated from her family, their judgements, and low expectations. She sets out to do just as she pleases, and so, the real story of Valancy’s life begins.

Though this story was originally intended for adults, there’s no reason why readers of middle grade and up wouldn’t enjoy this story of a young woman taking matters of her life into her own hands.

While it’s best to read the book without knowing too much of the story in advance so that it can delight and surprise as it unfolds without spoilers, here’s a detailed plot summary for those who might want one.

A Story Set in Ontario’s Muskoka Country

From the original review in The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec, Canada, October23, 1926): The author of the Anne of Green Gables books sets this story in Ontario, in the Muskoka country. Light is shed on the life of a small community and its individuals, with their smugness and pride and little family concerts.

Though intolerant in the matter of religion, at heart they are mostly good souls, overly fearful about what the world may think of improprieties done by one of their relatives.

The heroine of The Blue Castle is Valancy Stirling, called “Doss,” is twenty-nine regarded as an old maid. She’s thin, far from good looking, subject to colds, has a heart malady, and altogether is a poor risk.

Valancy has been repressed by her relatives all her life and her spirit has reached the point of rebellion when she reads something about fear being the worst sin. She goes to a doctor and is informed that her heart is bad and that she has but a year to live.

Strange as it may seem, Valancy is relieved and decides to hit out and have her fill of life. Her proper relatives are aghast. But in reality, she’s making a sacrifice and doing a real Christian Samaritan act.

Into her life comes an apparent rascal of a fellow, Barney Snaith, with a bad name in the community. A lonely Muskoka Island dweller, he’s not what he seems, and Valancy perceives that there’s no real evil in him.

Valancy’s path run together with Barney’s, causing a tremendous scandal. Then comes a strange romance and an even stranger denouement. The scalawag is unmasked and even Valancy is astounded. But it’s nothing to the shock of her relatives, when Barney Snaith’s true identity is revealed. It’s a skillful conclusion to a solid Canadian story.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Blue Castle & A Tangled Web

are available in a combined volume on Bookshop.org*

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review in the Edmonton Journal (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, November 23, 1926): The Blue Castle by L.M. Montgomery is the story of Valancy Stirling, who, at the age of twenty-nine, is told that she has only a year to live.

Valancy, who is generally known as “Doss,” the nickname bestowed on her by her irrepressible Uncle Benjamin, has lived her girlhood days in mouse-like seclusion, the unhappy puppet of her dull and respectable family.

Her only release — and that a temporary one — comes from her dreams of a shimmering blue castle in Spain. The turning point comes when she is told by Dr. Trent that she has a very dangerous form of heart disease — that she can not possibly live more than a year.

The discovery shocks her into the realization of the fact that she has never enjoyed one hour of real happiness in her life, and she determines to have one fling before she dies. She astounds her relatives by insisting that they shall call her “Valancy” in the future, and by defying them on occasion.

In the end she leaves her house and goes to the cottage of the drunken carpenter, Abel Gay, to look after his daughter Cissy, who is wasting away in the last stages of consumption.

A Hardy Rebel

Of course, her relatives are scandalized, but Valancy has made up her mind to live her own life, and a little later she throws her bonnet over the mill by going with Abel to a dance at Chidley Corners.

There she suffers considerable annoyance from the persistent attentions of one or two of the male dancers and is extricated from a somewhat awkward predicament by Barney Snaith, whom she had first met at Abel’s cottage.

Snaith is a man of mystery in the village. As he does not work at a trade, he is reputed to be anything from a jail-breaker to a forger and defaulter. Consequently, when on the way home, his car runs out of gas and he stops the first motorist who passes by — it happens to be Valancy’s Uncle Wellington —the fat is in the fire.

“The next thing the Stirlings heard was that Valancy had been seen with Barney Snaith in a movie theater in Port Lawrence and after it at supper in a Chinese restaurant there.” Of course after that, any shred of reputation which she might have retained was lost to her forever.

The Northern Retreat

Of Valancy’s marriage to Barney, and the happy days she spent with him on an unnamed island in a remote northern lake; her unconscious entrance into the “secret room;” the tragic consequences that result from the visit of Barney’s uncle — these things must be left for the reader to find out.

It is all told in the author’s happiest and most sympathetic manner, and those who enjoyed Montgomery’s earlier books will doubtless be delighted with The Blue Castle.

The attitude taken by Valancy’s family appears to be a somewhat antiquated one for the times in which we live and in some ways the heroine seems to overact her part. These are small blemishes, however, which will in no way deter L.M. Montgomery’s many readers from her latest offering.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Blue Castle is available in several audio adaptations,

including this one on Audible*

. . . . . . . . . .

These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased, Literary Ladies receives a modest commission, which helps us to grow.

The post The Blue Castle by L.M. Montgomery — Two 1926 Reviews appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 13, 2023

Five Novels by Carson McCullers: Classic Southern Gothic Fiction

Presented here is an overview of five novels by Carson McCullers (1917 – 1967), representing her body of long form fiction. Though known primarily for these books, she also wrote two plays, a number of short stories, children’s poetry, and other works.

Carson McCullers has earned a place among classic southern writers, along with William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Tennessee Williams. Following each brief overview of these major works is a link to more in-depth reviews or analyses.

Most of McCullers’ work is set in the American South, centering on characters who struggle with loneliness and isolation. Her writing is associated with the genre known as Southern Gothic, defined by the Oxford Research Encyclopedia:

“Characteristics of Southern Gothic include the presence of irrational, horrific, and transgressive thoughts, desires, and impulses; grotesque characters; dark humor, and an overall angst-ridden sense of alienation.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter (1940)

Carson McCullers was just twenty-three when The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, her first novel, was published in 1940, but her insights into human nature demonstrated wisdom beyond her years. The book was acclaimed as the work of a prodigy by critics and fellow writers.

Through its characters, the story delves into their struggle to build bridges between their separate islands of loneliness. The central characters all, in some odd way or another, seek answers to their confused desires from Singer, a deaf mute. He appears to them a man of mystical understanding.

Some of the unforgettable characters include Mick, an adolescent girl who longs to express herself in music; Jake Blount, a wild, blundering reformer; and Dr. Copeland, the African-American patriarch. Their appeal to Singer is the appeal of all humanity to a silent, cryptic universe. (— from the 1940 edition, Houghton Mifflin Co.).

More about The Heart is a Lonely Hunter Quotes from The Heart is a Lonely Hunter Mick Kelly: The Tomboy Author and Her Tomboy Heroine. . . . . . . . . .

Reflections in a Golden Eye (1941)

Reflections in a Golden Eye suffered a common fate of sophomore efforts that follow hugely successful first novels. When The Heart is a Lonely Hunter came out just the year before (1940), it established McCullers as a literary wunderkind.

Many reviewers objected to the intertwined plots of obsession, dark secrets, and repressed sexuality — both gay and straight — of the novel. It was, in fact, one of the few breakthrough novels that included gay themes in the first half of the twentieth century. Perhaps, though, in the hands of such a young author, these themes were simply not well executed.

The convergence of obsessive desires and clandestine affairs leads to a murder at the climax of the novel. Despite the negative reception of Reflections in a Golden Eye, it was adapted to film in 1967 with an all-star cast that included Elizabeth Taylor, Marlon Brando, Julie Harris, and Brian Keith. Like the novel, to which it was quite faithful, it got mixed reviews.

More about Reflections in a Golden Eye

. . . . . . . . . .

The Member of the Wedding (1946)

The Member of the Wedding (1946), Carson McCullers’ third novel (more accurately, a novella), followed the incredibly successful The Heart is a Lonely Hunter and the far less successful Reflections in a Golden Eye. The Member of the Wedding re-established McCullers, still in her twenties, as a literary force.

The story centers on a lonely twelve-year-old girl, Frankie Addams, who prefers to be known as F. Jasmine. Her mother has died, and her father, a jeweler, treats her with benign neglect. The story takes place during a hot summer in a small Georgia town, finding Frankie consumed with worry that she doesn’t belong anywhere or with anyone.

Her dull existence is shaken up when her older brother Jarvis, an army veteran, announces that he is to be married. The slim novel is a portrait of the interior workings of F. Jasmine’s adolescent mind as she fixates on the wedding and contends with the insular small town that she inhabits.

More about The Member of the Wedding Frankie Addams: Coming of Age in The Member of the Wedding. . . . . . . . . .

The Ballad of the Sad Café and Other Stories (1951)

When The Ballad of the Sad Café was first published in 1951, the original book included, in addition to the title novella, Carson’s other major works of fiction. In later editions, the title novella is presented with six short stories, as follows:

“The Ballad of the Sad Caf锓Wunderkind”“The Jockey”“Madame Zilensky and the King of Finland”“The Sojourner”, “A Domestic Dilemma”“A Tree, a Rock, a Cloud”The title story, written in the genre of Southern Gothic, concerns Miss Amelia, a masculine and eccentric woman (who is also a moonshiner), her purported cousin Lymon (a hunchback), and Marvin Macy, a recently released convict two whom Miss Amelia was briefly married.

In an isolated small town in rural Georgia in the 1930s, a stranger named Lymon approaches Miss Amelia, claiming to be her cousin. Uncharacteristically, she takes him into her home, setting rumors swirling. Once Macy returns, all hell breaks loose and the story culminates in a twist that even for its bizarre plot might be surprising.

More about The Ballad of the Sad Café

. . . . . . . . . .

Clock Without Hands (1961)

Clock Without Hands was McCullers’ final novel. It received mostly favorable reviews, but by the time of its publication, her greatest successes were behind her. A mixed view of the novel, noting nearly a decade gap between this and her previous published work, had this to say:

“Clock Without Hands reads like a plan for a novel or a flattened first draft, not the perfected expression of a writer who possesses moral concern and aesthetic awareness.

But, I suppose, we should remember that Hemingway wrote Across the River and Into the Trees and Faulkner wrote A Fable. If Clock Without Hands leads Carson McCullers beyond the present, it will serve a worthy purpose.”

Like in other McCullers novels and stories, this one contains queer themes, which may be one reason that reviewers in the 1960s weren’t always on board with her work. There are several plot lines in Clock Without Hands, each focusing on a major character:

J.T. Malone, proprietor of an old-fashioned drugstore in a small town is informed that he is fatally ill with leukemia. The heavy-drinking Judge Clane, who has a fantastic scheme to get himself re-elected to Congress after a long absence, while also making a fortune. Judge Clane’s grandson, Jester, and the mixed-race Sherman Pew, whom the judge engages as his secretary.

Learn more about Clock without Hands.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Carson McCullers and her work

Reader discussion of Carson McCuller’s books on Goodreads The Carson McCullers Project The Legacy Project Unhappy Endings: The Collected Carson McCullers The Closeting of Carson McCullersThe post Five Novels by Carson McCullers: Classic Southern Gothic Fiction appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 9, 2023

Reflections in a Golden Eye by Carson McCullers (1941)

Reflections in a Golden Eye (1941) by Carson McCullers suffered a fate common to sophomore efforts that follow hugely successful first novels. Just twenty-three when her first novel, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, came out the year before (1940), it established her as a literary wunderkind.

Reflections in a Golden Eye, conversely, received mostly poor reviews, critics unsure of what to make of the young author’s use of the literary device termed “the grotesque” in fiction — a hallmark of fellow Southern author Flannery O’Connor and others.

McCullers’ work was primarily associated with the genre of Southern Gothic, which the Oxford Research Encyclopedia defines as follows: “Characteristics of Southern Gothic include the presence of irrational, horrific, and transgressive thoughts, desires, and impulses; grotesque characters; dark humor, and an overall angst-ridden sense of alienation.”

Many reviewers objected to the intertwined plots of obsession, dark secrets, and repressed sexuality — both gay and straight — of the novel. It was, in fact, one of the few breakthrough novels that included gay themes in the first half of the twentieth century. Perhaps, though, in the hands of such a young author, these themes were simply not well executed.

In his syndicated “Literary Guideposts” column, John Selby griped that of that season’s new books, Reflections was “one of the most vulgar. Its presence on bookshelves makes one marvel at the fuss raised over Joyce’s Ulysses by those simple folk of the twenties. Ulysses at least had the recommendation of genius.”

Despite the negative reception of Reflections in a Golden Eye, it was adapted to film in 1967 with an all-star cast that included Elizabeth Taylor, Marlon Brando, Julie Harris, and Brian Keith. Like the novel, to which it was quite faithful, it got mixed reviews.

Perhaps audiences and reviewers were more ready in the late 1960s for the story’s themes than the previous generation had been in the early 1940s. Carson McCullers died in 1967, the year the film came out; it’s curious what she had thought of the adaptation.

A brief plot summary of Reflections in a Golden Eye

The story is situated in an army base in Georgia. Secretive, solitary Private Ellgee Williams does some work for Captain Penderton, happens to see the latter’s wife, Leonora, strolling around nude, and becomes obsessed with her.

Leonora’s lover (one of many she has had throughout her marriage) is Major Morris Langdon, who has a depressed wife, Alison, at home. Alison’s only comfort is her effeminate houseboy, Anacleto. Captain Penderton is a closeted homosexual who is attracted to Pvt. Ellgee Williams, unaware of the latter’s attraction to his wife.

This is a nutshell summary, but suffice it to say that the convergence of obsessive desires and clandestine affairs leads to a murder, which is the climax of the novel.

Following are two of the many reviews that appeared in 1941, when the novel was published. The first is basically a plot description that comes to a kinder conclusion than was typical of other reviews.

. . . . . . . . . . .

See also: The Heart is a Lonely Hunter

. . . . . . . . . . .

From the original review by H. Bruce Price in The Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY, March 9, 1941): Last spring Carson McCullers’ first novel, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, aroused a burst of glowing tribute. It was, you remember, a quiet, meditative, slow-moving book. Her second novel, Reflections In a Golden Eye, is a different sort of story.

Only two-thirds as long as the first, it moves swiftly with breath-taking tension. But time is still given for the study of a half-dozen characters, expertly created, and here again, many reflections in the mind’s eye of the reader are indelibly grotesque.

The locale is an army post down South. Among the enlisted men, there is Private Williams, an idiot boy from the backwoods. One night he looks through an open door of a house and sees Captain Penderton’s wife, Leonora, striding naked through the hall.

Private Williams had never seen a naked woman before, and his reaction to the sight impels a series of nightly vigils as strange and pathetic as a man ever kept. Leonora belongs not to the Captain but to his friend, Major Langdon, who is a stupid, healthy fellow, so unlike her husband.

Captain Penderton is brilliant. neurotic, and sexually perverted. He feels nothing but distaste for the Major’s wife, Alison. She is a sorrowful little creature, stricken with heart trouble and insane with grief over the loss of her only child. Her one comfort is the sensitive and aesthetic companionship of Anacleto, her Filipino servant.

We are told on the first page that all these people are participants in the tragedy of murder. However, only three of them, including the murderer and the victim, have any connection with it. Running parallel to the story of the murder is another story involving all but one of the characters. The two stories are quite independent of and superfluous to each other.

The total effect of each story is weakened by the total effect of the other. And yet they are so skillfully interwoven that the whole book seems to flow smoothly and naturally, and no reader could possibly tell them apart until reaching the end. Each story, taken separately, is constructed for suspense, surprise, drama, and curious irony. Every part of them, and the whole book, is exquisite.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers

. . . . . . . . . . .

The following piece isn’t so much a review as a rant. There is little description of the characters, themes, or plot. Instead, the critic devotes most of her pen to editorializing on the “depravity” of the novel. In a banal conclusion, she expresses her desire for the young author, Carson McCullers, to find more “pleasant” people and situations to write about (advice McCullers didn’t heed, fortunately).

Erroneous View of Army Life, Says Fort Banning Critic

From the original review by Phyllis Davis in The Columbus Enquirer (Columbus, GA), November 4, 1940): Every now and again, we find that a young writer, and perhaps a talented one, through unfortunate advice or a desire for instant recognition, is misled into confusing good literature with a type of writing that will “sell” temporarily.

It would appear that Carson McCullers has allowed such reasoning to color her early attempts at writing.

The men and women in this, her latest tale, as in the greatest part of her first book, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, are unfortunate ones — pitiful misfits in what she would have us believe is a whole world of misshapen personalities.

These characters, her editor told me when I shuddered at them, are “human beings, just like everybody else.” Human beings they certainly are, but just like everyone else — no! That idea is too alarming to contemplate at length.

In this story, Mrs. McCullers has selected the army for the background, and there, she has struck many a technical snag, for her knowledge of army life, its customs, and official military etiquette is slim indeed.

One wonders if all the professions so intimately represented in modern fiction — the law, medicine, and literature — must not suffer the twinges of righteous indignation when the inexperienced and uninformed hand attempts to pain such weird and surrealistic pictures of its lives and habits.

Surely, anyone in the army reading this story must have felt irked at first, but as the plot unfolds and becomes more and more foreign to any semblance of military or post life, there can be no particular reason for feeling other than an amused irritation and genuine amazement at the whole fantastic thing.

It’s to be wondered if, in this troubled world, when things look dark indeed, the younger writers might not find real inspiration and discover a deeper talent by exploring what is normal for a change!

Surely, such words as beauty, honor, loyalty, kindliness, and humor have not become too banal or unsophisticated to be written into the modern story. We shall come to the point where Pollyanna and all five of the Little Peppers will seem a welcome escape from the fruits of this neurotic school that seems to delve into volumes of medical research of schizophrenia and the like horrors for its inspiration.

Mrs. McCullers is young, with an untold amount of perseverance. She decided to write, and write she did. She has developed a style of her own that will gain in strength and power as she progresses in her career, and it would be a pleasant thing if her next book were to concern itself with pleasant people — for these are some, somewhere.

But let the joys be understandable and the sorrows those with which we can sympathize and share, and not those which thrive in the tortured minds of near depravity.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967 film)

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The post Reflections in a Golden Eye by Carson McCullers (1941) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 5, 2023

Proto-Zionist Themes in George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda

Daniel Deronda (1876)the last novel completed by British author George Eliot (pen name of Mary Ann Evans, 1819 – 1880), is widely regarded as a proto-Zionist work, and one of the first works of literature sympathetic to Jews in 19th-century Britain.

Like many of George Eliot’s novels, Daniel Deronda is considered a masterpiece. The examination of the novel’s Jewish themes presented here is from George Eliot by Mathilde Blind. Eliot wasn’t Jewish, but as this essayist points out:

“When she undertook to write about the Jews, George Eliot was deeply versed in Hebrew literature, ancient and modern. She had taught herself Hebrew when translating the Leben Jesu, and this knowledge stood her in good stead.”

The novel has two intertwining plot lines. One concerns Daniel Deronda, who, as an adult, discovers his Jewish origins, and the other concerns the beautiful, willful, and complex Gwendolen Harleth. Link through for a complete plot summary.

Through its characters, the expression of desire for a Jewish homeland made it both remarkable and controversial. Even Eliot’s partner, the editor and literary critic George Henry Lewes, opined that: “The Jewish element seems to me likely to satisfy nobody.”

The following is adapted for length and clarity from Chapter 14 of George Eliot by Mathilde Blind (public domain):

Daniel Deronda — George Eliot’s Proto-Zionist Novel

Daniel Deronda, which appeared five years after Middlemarch, occupies a place apart among George Eliot’s novels. In the spirit which animates it, it has perhaps the closest affinity with the Spanish Gypsy.

Speaking of this work to a young friend of Jewish extraction (in whose career George Eliot felt keen interest), she expressed surprise at the amazement which her choice of a subject had created. She remarked:

“I wrote about the Jews because I consider them a fine old race who have done great things for humanity. I feel the same admiration for them as I do for the Florentines. Only lately I have heard to my great satisfaction that an influential member of the Jewish community is going to start an emigration to Palestine.”

Mordecai’s ardent desire for a new Jewish stateThese observations are valuable as affording a key to the leading motive of Daniel Deronda. The character Mordecai’s ardent desire to found a new national state in Palestine is not simply the author’s dramatic realization of the feeling of an enthusiast, but expresses her own very definite sentiments on the subject.

The Jewish apostle is, in fact, more or less the mouthpiece of George Eliot’s own opinions on Judaism. For so great a master in the art of creating character, this type of the loftiest kind of man is curiously unreal.

Mordecai delivers himself of the most eloquent and exalted views and sentiments, yet his own personality remains so vague and nebulous that it has no power of kindling the imagination. Mordecai is meant for a Jewish Mazzini. Within his consciousness he harbours the future of a people.

He feels himself destined to become the saviour of his race; yet he does not convince us of his greatness. He convinces us no more than he does the mixed company at the “Hand and Banner,”which listens with pitying incredulity to his passionate harangues.

Nevertheless the first and final test of the religious teacher or of the social reformer is the magnetic force with which his own intense beliefs become binding on the consciences of others, if only of a few.

It is true Mordecai secures one disciple—the man destined to translate his thought into action, Daniel Deronda, as shadowy, as puppet-like, as lifeless as Ezra Mordecai Cohen himself.

These two men, of whom the one is the spiritual leader and the other the hero destined to realise his aspirations, are probably the two most unsuccessful of George Eliot’s vast gallery of characters. They are the representatives of an idea, but the idea has never been made flesh. A succinct expression of it may be gathered from the following passage:

“Which among the chief of the Gentile nations has not an ignorant multitude? They scorn our people’s ignorant observance; but the most accursed ignorance is that which has no observance—sunk to the cunning greed of the fox, to which all law is no more than a trap or the cry of the worrying hound.

There is a degradation deep down below the memory that has withered into superstition. For the multitude of the ignorant on three continents who observe our rites and make the confession of the Divine Unity the Lord of Judaism is not dead. Revive the organic centre: let the unity of Israel which has made the growth and form of its religion be an outward reality.

Looking towards a land and a polity, our dispersed people in all the ends of the earth may share the dignity of a national life which has a voice among the peoples of the East and the West; which will plant the wisdom and skill of our race, so that it may be, as of old, a medium of transmission and understanding.

Let that come to pass, and the living warmth will spread to the weak extremities of Israel, and superstition will vanish, not in the lawlessness of the renegade, but in the illumination of great facts which widen feeling, and make all knowledge alive as the young offspring of beloved memories.”

This notion that the Jews should return to Palestine in a body, and once more constitute themselves into a distinct nation, is curiously repugnant to modern feelings.

. . . . . . . . . .

Daniel Deronda: A splendid 2002 BBC miniseries

. . . . . . . . . .

As repugnant as that other doctrine, which is also implied in the book, that Jewish separateness should be still further insured by strictly adhering to their own race in marriage—at least Mirah, the most faultless of George Eliot’s heroines, whose character expresses the noblest side of Judaism, “is a Jewess who will not accept any one but a Jew.”

Mirah Lapidoth and the Princess Halm-Eberstein, Deronda’s mother, are drawn with the obvious purpose of contrasting two types of Jewish women.

Whereas the latter, strictly brought up in the belief and most minute observances of her Hebrew father, breaks away from the “bondage of having been born a Jew,” from which she wishes to relieve her son by parting from him in infancy, Mirah, brought up in disregard, “even in dislike of her Jewish origin,” clings with inviolable tenacity to the memory of that origin and to the fellowship of her people.

The author leaves one in little doubt as towards which side her own sympathies incline to. She is not so much the artist here, impartially portraying different kinds of characters, as the special pleader proclaiming that one set of motives are righteous, just, and praiseworthy, as well as that the others are mischievous and reprehensible …

Sympathies for a Jewish homelandConsidering that George Eliot was convinced of this modern tendency towards fusion, it is all the more singular that she should, in Daniel Deronda, have laid such stress on the reconstruction, after the lapse of centuries, of a Jewish state; singular, when one considers that many of the most eminent Jews, far from aspiring towards such an event, hardly seem to have contemplated it as a desirable or possible prospect.

The sympathies of Spinoza, the Mendelssohns, Heinrich Heine, and many others, are not distinctively Jewish but humanitarian. And the grandest, as well as truest thing that has been uttered about them is that saying of Heine’s: “The country of the Jews is the ideal, is God.”

Indeed, to have a true conception of Jewish nature and character, of its brilliant lights and deep shadows, of its pathos, depth, sublimity, degradation, and wit; of its infinite resource and boundless capacity for suffering—one must go to Heine and not to Daniel Deronda.

In Jehuda-ben-Halevy, Heine expresses the love and longing of a Jewish heart for Jerusalem in accents of such piercing intensity that compared with it, Mordecai’s fervid desire fades into mere abstract rhetoric.

Nature and experience were the principal sources of George Eliot’s inspiration. And though she knew a great deal about the Jews, her experience had not become sufficiently incorporated with her consciousness.