Nava Atlas's Blog, page 16

September 11, 2023

John Redding Goes to Sea by Zora Neale Hurston (1921)

Presented here is the full text of “John Redding Goes to Sea,” the first story by Zora Neale Hurston to be published.

Launching what would become her typical style, with characters speaking in dialect, the story was first published in the May, 1921 issue of Stylus, Howard University’s literary magazine. A slightly edited version in the January, 1926, issue of Opportunity, a prominent literary journal associated with the Harlem Renaissance.

More recently, the story is included in Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick (2020) a collection of Zora’s rediscovered short stories.

Set in a nameless Florida location that recalls Eatonville, the incorporated Black town where Zora grew up, a young man named John Redding wants set off and “go roving about the world for a spell” — much to his mother’s distress.

The central message of the story is that individuals need to be free to pursue their dreams and desires, even if doing so puts them at risk and distresses those close to them.

Analyses and discussions of “John Redding Goes to Sea”

Literary Theory and Criticism Bitter Southerner University of Notre Dame. . . . . . . . . . .

Zora Neale Hurston in her younger days

. . . . . . . . . . .

The villagers said that John Redding was a queer child. His mother thought he was too. She would shake her head sadly, and observe to John’s father: “Alf, it’s too bad our boy’s got a spell on ’im.”

The father always met this lament with indifference, if not impatience.

“Aw, woman, stop dat talk ’bout conjure. Tain’t so nohow. Ah doan want Jawn tuh git dat foolishness in him.”

“Cose you allus tries tuh know mo’ than me, but Ah ain’t so ign’rant. Ah knows a heap mahself. Many and many’s the people been drove outa their senses by conjuration, or rid tuh deat’ by witches.”

“Ah keep on telling yuh, woman, tain’t so. B’lieve it all you wants tuh, but dontcha tell mah son none of it.”

Perhaps ten-year-old John was puzzling to the simple folk there in the Florida woods for he was an imaginative child and fond of day-dreams. The St. John River flowed a scarce three hundred feet from his back door. On its banks at this point grow numerous palms, luxuriant magnolias and bay trees with a dense undergrowth of ferns, cat-tails and rope-grass. On the bosom of the stream float millions of delicately colored hyacinths. The little brown boy loved to wander down to the water’s edge, and, casting in dry twigs, watch them sail away down stream to Jacksonville, the sea, the wide world and John Redding wanted to follow them.

Sometimes in his dreams he was a prince, riding away in a gorgeous carriage. Often he was a knight bestride a fiery charger prancing down the white shell road that led to distant lands. At other times he was a steamboat captain piloting his craft down the St. John River to where the sky seemed to touch the water. No matter what he dreamed or who he fancied himself to be, he always ended by riding away to the horizon; for in his childish ignorance he thought this to be farthest land.

But these twigs, which John called his ships, did not always sail away. Sometimes they would be swept in among the weeds growing in the shallow water, and be held there. One day his father came upon him scolding the weeds for stopping his sea-going vessels.

“Let go mah ships! You ole mean weeds you!” John screamed and stamped impotently. “They wants tuh go ’way. You let ’em go on!”

Alfred laid his hand on his son’s head lovingly. “What’s mattah, son?”

“Mah ships, pa,” the child answered weeping. “Ah throwed ’em in to go way off an’ them ole weeds won’t let ’em.”

“Well, well, doan cry. Ah thought youse uh grown up man. Men doan cry lak babies. You mustn’t take it too hard ’bout yo’ ships. You gotta git uster things gittin’ tied up. They’s lotser folks that ’ud go on off too ef somethin’ didn’ ketch ’em an’ hol’ ’em!”

Alfred Redding’s brown face grew wistful for a moment, and the child noticing it, asked quickly: “Do weeds tangle up folks too, pa?”

“Now, no, chile, doan be takin’ too much stock of what Ah say. Ah talks in parables sometimes. Come on, les go on tuh supper.”

Alf took his son’s hand, and started slowly toward the house. Soon John broke the silence.

“Pa, when Ah gets as big as you Ah’m goin’ farther than them ships. Ah’m goin’ to where the sky touches the ground.”

“Well, son, when Ah wuz a boy Ah said Ah wuz goin’ too, but heah Ah am. Ah hopes you have bettah luck than me.”

“Pa, Ah betcha Ah seen somethin’ in th’ woodlot you ain’t seen!”

“Whut?”

“See dat tallest pine tree ovah dere how it looks like a skull wid a crown on?”

“Yes, indeed!” said the father looking toward the tree designated. “It do look lak a skull since you call mah ’tention to it. You ’magine lotser things nobody else evah did, son!”

“Sometimes, Pa dat ole tree waves at me just aftah th’ sun goes down, an’ makes me sad an’ skeered, too.”

“Ah specks youse skeered of de dahk, thas all, sonny. When you gits biggah you won’t think of sich.”

Hand in hand the two trudged across the plowed land and up to the house, the child dreaming of the days when he should wander to far countries, and the man of the days when he might have—and thus they entered the kitchen.

Matty Redding, John’s mother, was setting the table for supper. She was a small wiry woman with large eyes that might have been beautiful when she was young, but too much weeping had left them watery and weak.

“Matty,” Alf began as he took his place at the table, “dontcha know our boy is different from any othah chile roun’ heah. He ’lows he’s goin’ to sea when he gits grown, an’ Ah reckon Ah’ll let ’im.”

The woman turned from the stove, skillet in hand. “Alf, you ain’t gone crazy, is you? John kain’t help wantin’ tuh stray off, cause he’s got a spell on ’im; but you oughter be shamed to be encouragin’ him.”

“Ain’t Ah done tol’ you forty times not tuh tahk dat low-life mess in front of mah boy?”

“Well, ef tain’t no conjure in de world, how come Mitch Potts been layin’ on his back six mont’s an’ de doctah kain’t do ’im no good? Answer me dat. The very night John wuz bawn, Granny seed ole Witch Judy Davis creepin outer dis yahd. You know she had swore tuh fix me fuh marryin’ you, ’way from her darter Edna. She put travel dust down fuh mah chile, dat’s whut she done, tuh make him walk ’way fum me. An’ evuh sence he’s been able tuh crawl, he’s been tryin tuh go.”

“Matty, a man doan need no travel dust tuh make ’im wanter hit de road. It jes’ comes natcheral fuh er man tuh travel. Dey all wants tuh go at some time or other but they kain’t all get away. Ah wants mah John tuh go an’ see cause Ah wanted to go mah self. When he comes back Ah kin see them furrin places wid his eyes. He kain’t help wantin’ tuh go cause he’s a man chile!”

Mrs. Redding promptly went off into a fit of weeping but the man and boy ate supper unmoved. Twelve years of married life had taught Alfred that far from being miserable when she wept, his wife was enjoying a bit of self-pity.

Thus John Redding grew to manhood, playing, studying and dreaming. He attended the village school as did most of the youth about him, but he also went to high school at the county seat where none of the villagers went. His father shared his dreams and ambitions, but his mother could not understand why he should wish to go strange places where neither she nor his father had been. No one of their community had ever been farther away than Jacksonville. Few indeed had ever been there. Their own gardens, general store, and occasional trips to the county seat—seven miles away—sufficed for all their needs. Life was simple indeed with these folk.

John was the subject of much discussion among the country folk. Why didn’t he teach school instead of thinking about strange places and people? Did he think himself better than any of the “gals” there about that he would not go a-courting any of them? He must be “fixed” as his mother claimed, else where did his queer notions come from? Well, he was always queer, and one could not expect the man to be different from the child. They never failed to stop work at the approach of Alfred in order to be at the fence and inquire after John’s health and ask when he expected to leave.

“Oh,” Alfred would answer. “Jes’ as soon as his mah gits reconciled to th’ notion. He’s a mighty dutiful boy, mah John is. He doan wanna hurt her feelings.”

The boy had on several occasions attempted to reconcile his mother to the notion, but found it a difficult task. Matty always took refuge in self-pity and tears. Her son’s desires were incomprehensible to her, that was all. She did not want to hurt him. It was love, mother love, that made her cling so desperately to John.

“Lawd knows,” she would sigh, “Ah nevah wuz happy an’ nevah specks tuh be.”

“An’ from yo’ actions,” put in Alfred hotly, “you’s determined not to be.”

“Thas right, Alfred, go on an’ ’buse me. You allus does. Ah knows Ah’m ign’rant an’ all dat, but dis is mah son. Ah bred an’ born ’im. He kain’t help from wantin’ to go rovin’ cause travel dust been put down fuh him. But mebbe we kin cure ’im by disincouragin’ the idee.”

“Well, Ah wants mah son tuh go; an’ he wants tuh go too. He’s a man now, Matty. An’ we mus’ let John hoe his own row. If it’s travelin’ twon’t be foh long. He’ll come back to us bettah than when he went off. What do you say, son?”

“Mamma,” John began slowly, “it hurts me to see you so troubled over my going away; but I feel that I must go. I’m stagnating here. This indolent atmosphere will stifle every bit of ambition that’s in me. Let me go mamma, please. What is there here for me? Why, sometimes I get to feeling just like a lump of dirt turned over by the plow—just where it falls there’s where it lies—no thought or movement or nothing. I wanter make myself something—not just stay where I was born.”

“Naw, John, it’s bettah for you to stay heah and take over the school. Why don’t you marry and settle down?”

“I don’t want to, mamma. I want to go away.”

“Well,” said Mrs. Redding, pursing her mouth tightly, “you ainta goin’ wid mah consent!”

“I’m sorry mamma, that you won’t consent. I am going nevertheless.”

“John, John, mah baby! You wouldn’t kill yo’ po’ ole mamma, would you? Come, kiss me, son.”

The boy flung his arms about his mother and held her closely while she sobbed on his breast. To all of her pleas, however, he answered that he must go.

“I’ll stay at home this year, mamma, then I’ll go for a while, but it won’t be long. I’ll come back and make you and papa oh so happy. Do you agree, mamma dear?”

“Ah reckon tain’ nothin’ tall fuh me to do else.”

Things went on very well around the Redding home for some time. During the day John helped his father about the farm and read a great deal at night.

Then the unexpected happened. John married Stella Kanty, a neighbor’s daughter. The courtship was brief but ardent—on John’s part at least. He danced with Stella at a candy-pulling, walked with her home and in three weeks had declared himself. Mrs. Redding declared that she was happier than she had ever been in her life. She therefore indulged in a whole afternoon of weeping. John’s change was occasioned possibly by the fact that Stella was really beautiful; he was young and red-blooded, and the time was spring.

Spring-time in Florida is not a matter of peeping violets or bursting buds merely. It is a riot of color in nature—glistening green leaves, pink, blue, purple, yellow blossoms that fairly stagger the visitor from the north. The miles of hyacinths lie like an undulating carpet on the surface of the river and divide reluctantly when the slow-moving alligators push their way log-like across. The nights are white nights for the moon shines with dazzling splendor, or in the absence of that goddess, the soft darkness creeps down laden with innumerable scents. The heavy fragrance of magnolias mingled with the delicate sweetness of jasmine and wild roses.

If time and propinquity conquered John, what then? These forces have overcome older men.

The raptures of the first few weeks over, John began to saunter out to the gate to gaze wistfully down the white dusty road; or to wander again to the river as he had done in childhood. To be sure he did not send forth twig-ships any longer, but his thoughts would in spite of himself, stray down river to Jacksonville, the sea, the wide world—and poor home-tied John Redding wanted to follow them.

He grew silent and pensive. Matty accounted for this by her ever-ready explanation of “conjuration.” Alfred said nothing but smoked and puttered about the barn more than ever. Stella accused her husband of indifference and made his life miserable with tears, accusations and pouting. At last John decided to bring matters to a head and broached the subject to his wife.

“Stella, dear, I want to go roving about the world for a spell. Would you stay here with papa and mamma and wait for me to come back?”

“John, is you crazy sho’ nuff? If you don’t want me, say so an’ I kin go home to mah folks.”

“Stella, darling, I do want you, but I want to go away too. I can have both if you’ll let me. We’ll be so happy when I return . . .”

“Naw, John, you kain’t rush me off one side like that. You didn’t hafta marry me. There’s a plenty othahs that would have been glad enuff tuh get me; you know Ah wan’t educated befo’ han’.”

“Don’t make me too conscious of my weakness, Stella. I know I should never have married with my inclinations, but it’s done now, no use to talk about what is past. I love you and want to keep you, but I can’t stifle that longing for the open road, rolling seas, for peoples and countries I have never seen. I’m suffering too, Stella, I’m paying for my rashness in marrying before I was ready. I’m not trying to shirk my duty—you’ll be well taken care of in the meanwhile.”

“John, folks allus said youse queer and tol’ me not to marry yuh, but Ah jes’ loved yuh so Ah couldn’t help it, an’ now to think you wants tuh sneak off an’ leave me.”

“But I’m coming back, darling . . . listen Stella.”

But the girl would not. Matty came in and Stella fell into her arms weeping. John’s mother immediately took up arms against him. The two women carried on such an effective war against him for the next few days that finally Alfred was forced to take his son’s part.

“Matty, let dat boy alone, Ah tell you! Ef he wuz uh homebuddy he’d be drove ’way by you all’s racket.”

“Well, Alf, dat’s all we po’ wimmen kin do. We wants our husbands an’ our sons. John’s got uh wife now, an’ he ain’t got no business to be talkin’ ’bout goin’ nowheres. I ’lowed dat marryin’ Stella would settle him.”

“Yas, dat’s all you wimmen study ’bout —settlin’ some man. You takes all de get-up out of ’em. Jes’ let uh fellah mak uh motion lak gettin’ somewhere, an’ some ’oman’ll begin tuh hollah, ‘Stop theah! where’s you goin’? Don’t fuhgit you b’longs tuh me.’ ”

“My Gawd! Alf! Whut you reckon Stella’s gwine do? Let John walk off an’ leave huh?”

“Naw, git outer huh foolishness an’ go ’long wid him. He’d take huh.”

“Stella ain’t got no call tuh go crazy ’cause John is. She ain’t no woman tuh be floppin’ roun’ from place tuh place lak some uh dese reps follerin’ uh section gang.”

The man turned abruptly from his wife and stood in the kitchen door. A blue haze hung over the river and Alfred’s attention seemed fixed upon this. In reality his thoughts were turned inward. He was thinking of the numerous occasions upon which he and his son had sat on the fallen log at the edge of the water and talked of John’s proposed travels. He had encouraged his son, given him every advantage his own poor circumstances would permit. And now John was home-tied.

The young man suddenly turned the corner of the house and approached his father.

“Hello, papa.”

“’Lo, son.”

“Where’s mamma and Stella?”

The older man merely jerked his thumb toward the interior of the house and once more gazed pensively toward the river. John entered the kitchen and kissed his mother fondly.

“Great news, mamma.”

“What now?”

“Got a chance to join the Navy, mamma, and go all around the world. Ain’t that grand?”

“John, you shorely ain’t gointer leave me an’ Stella, is yuh?”

“Yes, I think I am. I know how both of you feel, but I know how I feel, also. You preach to me the gospel of self-sacrifice for the happiness of others, but you are unwilling to practice any of it yourself. Stella can stay here—I am going to support her and spend all the time I can with her. I am going—that’s settled, but I want to go with your good will. I want to do something worthy of a strong man. I have done nothing so far but look to you and papa for everything. Let me learn to strive and think—in short, be a man.”

“Naw, John, Ah’ll nevah give mah consent. I know yous hard-headed jes’ lak yo’ paw; but if you leave dis place ovah mah head, Ah nevah wants you tuh come back heah no mo. Ef Ah wuz laid on de coolin’ board, Ah doan want yuh standin’ ovah me, young man. Doan even come neah mah grave, you ongrateful wretch!”

Mrs. Redding arose and flung out of the room. For once, she was too incensed to cry. John stood in his tracks, gone cold and numb at his mother’s pronouncement. Alfred, too, was moved. Mrs. Redding banged the bed-room door violently and startled John slightly. Alfred took his son’s arm, saying softly: “Come, son, let’s go down to the river.”

At the water’s edge they halted for a short space before seating themselves on the log. The sun was setting in a purple cloud. Hundreds of mosquito hawks darted here and there, catching gnats and being themselves caught by the lightning-swift bullbats. John abstractly snapped in two the stalk of a slender young bamboo. Taking no note of what he was doing, he broke it into short lengths and tossed them singly into the stream. The old man watched him silently for a while, but finally he said: “Oh, yes, my boy, some ships get tangled in the weeds.”

“Yes, papa, they certainly do. I guess I’m beaten—might as well surrender.”

“Nevah say die. Yuh nevah kin tell what will happen.”

“What can happen? I have courage enough to make things happen; but what can I do against mamma! What man wants to go on a long journey with his mother’s curses ringing in his ears? She doesn’t understand. I’ll wait another year, but I am going because I must.”

Alfred threw an arm about his son’s neck and drew him nearer but quickly removed it. Both men instantly drew apart, ashamed for having been so demonstrative. The father looked off to the woodlot and asked with a reminiscent smile: “Son, do you remember showin’ me the tree dat looked lak a skeleton head?”

“Yes, I do. It’s there still. I look at it sometimes when things have become too painful for me at the house, and I run down here to cool off and think. And every time I look at it, papa, it laughs at me like it had some grim joke up its sleeve.”

“Yuh wuz always imaginin’ things, John; things that nobody else evah thought on!”

“You know, papa, sometimes—I reckon my longing to get away makes me feel this way. . . . I feel that I am just earth, soil lying helpless to move myself, but thinking. I seem to hear herds of big beasts like horses and cows thundering over me, and rains beating down; and winds sweeping furiously over—all acting upon me, but me, well, just soil, feeling but not able to take part in it all. Then a soft wind like love passes over and warms me, and a summer rain comes down like understanding and softens me, and I push a blade of grass or a flower, or maybe a pine tree—that’s the ground thinking. Plants are ground thoughts, because the soil can’t move itself. Whenever I see little whirls of dust sailing down the road I always step aside—don’t want to stop ’em ’cause they’re on their shining way—moving! Oh, yes, I’m a dreamer. . . . I have such wonderfully complete dreams, papa. They never come true. But even as my dreams fade I have others.”

“Yas, son, Ah have them same feelings exactly, but Ah can’t find no words lak you do. It seems lak you an’ me see wid de same eyes, hear wid de same ears an’ even feel de same inside. Only thing you kin talk it an’ Ah can’t. But anyhow you speaks for me, so whut’s the difference?”

The men arose without more conversation. Possibly they feared to trust themselves to speech. As they walked leisurely toward the house Alfred remarked the freshness of the breeze.

“It’s about time the rains set in,” added his son. “The year is wearin’ on.”

After a gloomy supper John strolled out into the spacious front yard and seated himself beneath a China-berry tree. The breeze had grown a trifle stronger since sunset and continued from the south-east. Matty and Stella sat on the deep front porch, but Alfred joined John under the tree. The family was divided into two armed camps and the hostilities had reached that stage where no quarter could be asked or given.

About nine o’clock an automobile came flying down the dusty white road and halted at the gate. A white man slammed the gate and hurried up the walk toward the house, but stopped abruptly before the men beneath the China-berry. It was Mr. Hill, the builder of the new bridge that was to span the river.

“Howdy John, Howdy Alf. I’m mighty glad I found you. I am in trouble.”

“Well now, Mist’ Hill,” answered Alfred slowly but pleasantly. “We’se glad you foun’ us too. What trouble could you be having now?”

“It’s the bridge. The weather bureau says that the rains will be upon me in forty-eight hours. If it catches the bridge as it is now, I’m afraid all my work of the past five months will be swept away, to say nothing of a quarter of a million dollars’ worth of labor and material. I’ve got all my men at work now and I thought to get as many extra hands as I could t0 help out tonight and tomorrow. We can make her weather tight in that time if I can get about twenty more.”

“I’ll go, Mister Hill,” said John with a great deal of energy. “I don’t want papa out on that bridge—too dangerous.”

“Good for you, John!” cried the white man. “Now if I had a few more men of your brawn and brain, I could build an entirely new bridge in forty-eight hours. Come on and jump into the car. I am taking the men on down as I find them.”

“Wait a minute. I must put on my blue jeans. I won’t be long.”

John arose and strode to the house. He knew that his mother and wife had overheard everything, but he paused for a moment to speak to them.

“Mamma, I am going to work all night on the bridge.”

There was no answer. He turned to his wife.

“Stella, don’t be lonesome. I will be home at day-break.”

His wife was as silent as his mother. John stood for a moment on the steps, then resolutely strode past the women and into the house. A few minutes later he emerged clad in his blue overalls and brogans. This time he said nothing to the silent figures rocking back and forth on the porch. But when he was a few feet from the steps he called back: “Bye, mamma; bye, Stella,” and hurried on down the walk to where his father sat.

“So long, papa. I’ll be home around seven.”

Alfred roused himself and stood. Placing both hands upon his son’s broad shoulders he said softly: “Be keerful son, don’t fall or nothin’.”

“I will, papa. Don’t you get into a quarrel on my account.”

John hurried on to the waiting car and was whirled away.

Alfred sat for a long time beneath the tree where his son had left him and smoked on. The women soon went indoors. On the night breeze were borne numerous scents: of jasmine, of roses, of damp earth of the river, of the pine forest near by. A solitary whip-poor-will sent forth his plaintive call from the nearby shrubbery. A giant owl roared and boomed from the woodlot. The calf confined in the barn would bleat and be answered by his mother’s sympathetic “moo” from the pen. Away down in Lake Howell Creek the basso profundo of the alligators boomed and died, boomed and died.

Around ten o’clock the breeze freshened, growing stiffer until midnight when it became a gale. Alfred fastened the doors and bolted the wooden shutters at the windows. The three persons sat about a round deal table in the kitchen upon which stood a bulky kerosene lamp, flickering and sputtering in the wind that came in through the numerous cracks in the walls. The wind rushed down the chimney blowing puffs of ashes about the room. It banged the cooking utensils on the walls. The drinking gourd hanging outside by the door played a weird tattoo, hollow and unearthly, against the thin wooden wall.

The man and the women sat silently. Even if there had been no storm they would not have talked. They could not go to bed because the women were afraid to retire during a storm and the man wished to stay awake and think with his son. Thus they sat: the women hot with resentment toward the man and terrified by the storm; the man hardly mindful of the tempest but eating his heart out in pity for his boy. Time wore heavily on.

And now a new element of terror was added. A screech-owl alighted on the roof and shivered forth his doleful cry. Possibly he had been blown out of his nest by the wind. Matty started up at the sound but fell back in her chair, pale and trembling: “My Gawd!” she gasped, “dat’s a sho’ sign uh death.”

Stella hurriedly thrust her hand into the salt-jar and threw some into the chimney of the lamp. The color of the flame changed from yellow to blue-green but this burning of salt did not have the desired effect—to drive away the bird from the roof. Matty slipped out of her blue calico wrapper and turned it wrong side out before replacing it. Even Alfred turned one sock.

“Alf,” said Matty, “what do you reckon’s gonna happen from this?”

“How do Ah know, Matty?”

“Ah wisht John hadn’t went away from heah tuh night.”

“Humh.”

Outside the tempest raged. The palms rattled dryly and the giant pines groaned and sighed in the grip of the wind. Flying leaves and pine-mast filled the air. Now and then a brilliant flash of lightning disclosed a bird being blown here and there with the wind. The prodigious roar of the thunder seemed to rock the earth. Black clouds hung so low that the tops of the pines were among them moving slowly before the wind and made the darkness awful. The screech-owl continued his tremulous cry.

After three o’clock the wind ceased and the rain commenced. Huge drops clattered down upon the shingle roof like buckshot and ran from the eaves in torrents. It entered the house through the cracks in the walls and under the doors. It was a deluge in volume and force but subsided before morning.

The sun came up brightly on the havoc of the wind and rain calling forth millions of feathered creatures. The white sand everywhere was full of tiny cups dug out by the force of the falling raindrops. The rims of the little depressions crunched noisily underfoot.

At daybreak Mr. Redding set out for the bridge. He was uneasy. On arriving he found that the river had risen twelve feet during the cloudburst and was still rising. The slow St. John was swollen far beyond its banks and rushing on to sea like a mountain stream, sweeping away houses, great blocks of earth, cattle, trees—in short anything that came within its grasp. Even the steel framework of the new bridge was gone!

The siren of the fibre factory was tied down for half an hour, announcing the disaster to the country side. When Alfred arrived therefore he found nearly all the men of the district there.

The river, red and swollen, was full of floating debris. Huge trees were swept along as relentlessly as chicken coops and fence rails. Some steel piles were all that was left of the bridge.

Alfred went down to a group of men who were fishing members of the ill-fated construction gang out of the water. Many were able to swim ashore unassisted. Wagons backed up and were hurriedly driven away loaded with wet shivering men. Two men had been killed outright, others seriously wounded. Three men had been drowned. At last all had been accounted for except John Redding. His father ran here and there asking for him, or calling him. No one knew where he was. No one remembered seeing him since daybreak.

Dozens of women had arrived at the scene of the disaster by this time. Matty and Stella, wrapped in woolen shawls, were among them. They rushed to Alfred in alarm and asked where was John.

“Ah doan know,” answered Alfred impatiently, “that’s what Ah’m trying to fin’ out now.”

“Do you reckon he’s run away?” asked Stella thoughtlessly.

Matty bristled instantly.

“Naw,” she answered sternly, “he ain’t no sneak.”

The father turned to Fred Mimms, one of the survivors and asked him where John was and how had the bridge been destroyed.

“Yuh see,” said Mimms, “when dat turrible win’ come up we wuz out ’bout de middle of de river. Some of us wuz on de bridge, some on de derrick. De win’ blowed so hahd we could skeercely stan’ and Mist’ Hill tol’ us tuh set down fuh a spell. He’s ’fraid some of us mought go overboard. Den all of a sudden de lights went out—guess de wires wuz blowed down. We wuz all skeered tuh move for slippin’ overboard. Den dat rain commenced—an’ Ah nevah seed such a down-pour since de flood. We set dere and someone begins tuh pray. Lawd how we did pray tuh be spared! Den somebody raised a song an’ we sung, you hear me, we sung from de bottom of our hearts till daybreak. When the first light come we couldn’t see nothin’ but fog everywhere. You couldn’t tell which wuz water an’ which wuz lan’. But when de sun come up de fog begin to liff, an’ we could see de water. Dat fog wuz so thick an’ heavy dat it wuz huggin’ dat river lak a windin’ sheet. And when it rose we saw dat de river had rose way up durin’ the rain. My Gawd, Alf! it wuz runnin’ high—so high it nearly teched de span of de bridge—an’ red as blood! So much clay, you know from lan’ she done overflowed. Comin’ down stream, as fas’ as ’press train wuz three big pine trees. De first one wuzn’t fohty feet from us and there wasn’t no chance to do nothin’ but pray. De fust one struck us and shook de whole works an’ befo’ it could stop shakin’ the other two hit us an’ down we went. Ah thought Ah’d never see home again.”

“But, Mimms, where’s John?”

“Ah ain’t seen him, Alf, since de logs struck us. Mebbe he’s swum ashore, mebbe dey picked him up. What’s dat floatin’ way out dere in de water?”

Alfred shaded his eyes with his gnarled brown hand and gazed out into the stream. Sure enough there was a man floating on a piece of timber. He lay prone upon his back. His arms were outstretched, and the water washed over his brogans but his feet were lifted out of the water whenever the timber was buoyed up by the stream. His blue overalls were nearly torn from his body. A heavy piece of steel or timber had struck him in falling for his left side was laid open by the thrust. A great jagged hole wherein the double fists of a man might be thrust, could plainly be seen from the shore. The man was John Redding.

Everyone seemed to see him at once. Stella fell to the wet earth in a faint. Matty clung to her husband’s arm, weeping hysterically. Alfred stood very erect with his wife clinging tearfully to him, but he said nothing. A single tear hung on his lashes for a time then trickled slowly down his wrinkled brown cheek.

“Alf! Alf!” screamed Matty, “dere’s our son. Ah knowed when Ah heard dat owl las’ night. . . .”

“Ah see ’im, Matty,” returned her husband softly.

“Why is yuh standin’ heah? Go git mah boy.”

The men were manning a boat to rescue the remains of John Redding when Alfred spoke again.

“Mah po’ boy, his dreams never come true.”

“Alf,” complained Matty, “why doantcher hurry an’ git my boy—doantcher see he’s floatin’ on off?”

Her husband paid her no attention but addressed himself to the rescue-party.

“You all stop! Leave my boy go on. Doan stop ’im. Doan’ bring ’im back for dat ole tree to grin at. Leave him g’wan. He wants tuh go. Ah’m happy ’cause dis mawnin’ mah boy is goin’ tuh sea, he’s goin’ tuh sea.”

Out on the bosom of the river, bobbing up and down as if waving good bye, piloting his little craft on the shining river road, John Redding floated away toward Jacksonville, the sea, the wide world—at last.

The post John Redding Goes to Sea by Zora Neale Hurston (1921) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 1, 2023

The Chosen Place, The Timeless People by Paule Marshall (1969)

The Chosen Place, The Timeless People, was the second full-length novel by Paule Marshall (1929 – 2019). Following her first novel, Brown Girl, Brownstones (1959), she published a collection of four novellas in Soul Clap Hands and Sing (1961).

In its recognition of the intersectionality of race, class, and colonialism,The Chosen Place, The Timeless People was ahead of its time.

A New York Times reviewer called it “the best novel to be written by an American Black woman” when it was published in 1969. Such praise sounds patronizing in the present day, but let’s discount the reviewer’s limitations and focus on the recognition the comment represented.

Despite the many good reviews Marshall received, she never achieved the kind of celebrity afforded other Black writers, according to Donna Hill of the Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College.

Marshall saw herself as the product of a triangular identity that included Africa, the Caribbean, and Brooklyn. The Chosen Place, the Timeless People thus appropriately revolves around three characters who come together on the fictional Caribbean island of Bourne “a hundred-and-seventy square miles of sugar cane stuck in the middle of nowhere.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Paule Marshall

(fair use image from BlackPast.org)

. . . . . . . . . .

The first character we meet is Merle Kinbona (though we don’t learn her name right away). Kinbona is a native of Bourne who has a past in London and a future in East Africa. She is the fulcrum of the story. She is a powerful woman:

“… her eyes … gave the impression of being lighted from deep within (it was as if she had been endowed with her own small sun), and they were an unusually clear tawny shade of brown, an odd, even eerie, touch in a face that was the color of burnt sugar.”

In the course of the novel, we will learn that Merle is the daughter of a white British man, descended from the founder of the sugar plantation, and a Black West Indian woman who was murdered when Merle was a toddler.

Merle is headed toward middle age, but she dresses “like a much younger woman.” She wears “strange but beautiful earrings that had been given to her years ago in England by the woman who had been, some said, her benefactress; others, her lover.”

Along with the beautiful and finely made earrings, she wears numerous bracelets, “crudely made.” The contrast between these items, along with other aspects of Merle’s appearance, reveals Merle’s “diversity and disunity within herself” and that she has suffered “some profound and frightening loss.”

Saul Amron and Harriet Shippen

Even as we meet Merle, who is having car trouble due to the poor condition of the roads on the island, a small plane carrying four passengers is about to land and upend life within this community.

The passengers include the other two major characters of the novel: Saul Amron, an American anthropologist and a Jew, along with Harriet Shippen, his wife of one year, a mainline Philadelphia WASP whose family profited from the slave trade.

Saul is on his way to the island to undertake a research project that he hopes will help alleviate the extreme poverty of Bournehills, the community on the island where Merle and most of the other characters live. Harriet has influenced the foundation that is funding the project to bankroll Saul’s efforts.

Minor but Important Characters

We are introduced to Saul and Harriet through the eyes of another passenger on that plane, Saul’s statistician, Allen Fuso. A white American whose working-class background is very different from Harriet’s wealthy upbringing, he is the product of “the whole of Europe from Ireland to Italy.” Fuso, a closeted gay man, plays an important supporting role in the story.

The fourth passenger on the plane is Vere (Vereson Walkes). His tragic story is crucial to our understanding of Bournehills. He is a native of Bourne who is returning to the island after three years in the Farm Labor Scheme in the United States.

While working in the cane fields of Florida, Vere faced brutality and humiliation. Now he fantasizes about winning love and respect by building a race car and impressing everyone with its beauty and speed at the races on Whitsun.

Whitsun, a shortened form of White Sunday, is a Christian holiday that is widely observed in Britain and many of its former colonies with races, parades, and festivals. It occurs seven weeks after Easter Sunday. It is called White Sunday because traditionally people wore white clothing on that day, but Marshall is obviously drawing on another meaning of “white” in her emphasis on the festival in this novel.

We meet other characters through Vere: Leesy is the old aunt who raised Vere after his mother died in childbirth. Leesy lost her husband in a sugar-processing plant accident, and she has some prophetic powers, at least when it comes to Vere. She anticipates his return even though he has not been able to communicate his coming to her.

Another character we learn about through Vere is the (unnamed) woman who bore his child—a child who died of apparent neglect—and who now survives through prostitution.

Another significant, though minor, character is Lyle Hutson, the successful and popular barrister. Hutson is also a businessman. He is building a yacht club for successful Black people on the island such as himself who are barred from the Bourne Island Yacht Club because of their color.

Lyle is known for his adulterous affairs with white women. And he will be the friction that blocks Saul’s progress—and the instigator of Harriet’s tragic end.

. . . . . . . . . .

See Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones

. . . . . . . . . .

All these characters, and many others, are fully delineated and brought to life through Marshall’s skillful prose. Each has her or his aspirations and motives; each has her or his sources of pain and disappointment.

In the unfolding of the story, we will learn that Merle’s ex-husband left her after learning of her affair with the white British woman who gave her those beautiful earrings. When he left, he took their daughter.

Saul is wracked with guilt over the death of his first wife, who died while they were doing anthropological field research in Honduras. Harriet, the least sympathetic of the three principals, is portrayed as a well-meaning though misguided white woman.

She is desperate to take on meaningful work despite an upbringing that raised her to exist purely as an ornamental accessory. But her belief that she knows best for all concerned, including those of a different culture, alienates Saul and places her in peril.

Saul is portrayed extremely sympathetically (though the repeated references to the size and shape of his nose suggest certain anti-Semitic tropes). His Jewish heritage is central to his identity, and the title of the novel evokes the idea of the chosen people. Saul, as a white American, had privileges not available to the Black people of Bournehills, and yet Bournehills is his chosen place.

Marshall offers parallels in the ancient histories and experiences of oppression of Africans and Jews. Like Africans, Jews have an ancient history. Both are arguably timeless in their traditions and awareness of the past.

The history and spirit of Cuffee Ned, leader of a briefly successful slave uprising, haunts the island and is mentioned again and again as well as re-enacted. Merle, in fact, loses her position as a teacher because of her insistence on relating the tale of Cuffee Ned to her students. (Marshall might have been anticipating the current situation in many U.S. schools.)

The scourge of sugar—widely regarded as the source of the slave trade in the Americas—hangs over the island as well. The working conditions are brutal. The workers are at the mercy of those who own the land and the processing equipment. And everyone on the island is diabetic.

Needless to say, the arrival of the American research team disrupts the balance of power in the Bournehills community. While the status quo was neither just or idyllic, the disruptions highlight the ongoing effects of British imperialism as well as the more recent imposition of U.S. capitalism.

Accusations of Homophobia

In her 2019 LitHub essay “Mourning Paule Marshall, the Foremother Who Didn’t Always Love Me Back,” Rosamond S. King, a self-described “queer Caribbean writer and critic,” tackles the issue of Marshall’s attitude toward queer love and identities.

There are certainly negative descriptions of gay people: early in the novel, when Merle takes Saul to the club known as Sugar’s, she indicates “that bunch out on the balcony” and says that no boy “over the age of three is safe” from them.

Yet closeted Allen is portrayed sympathetically, if sadly. He denies his sexual attraction to Vere until he finds himself unable to respond to the young woman Vere provides to him. It’s only when he realizes that he can reach orgasm only by masturbating to the sound of Vere having sex with a woman in the next room that he is able to recognize his own sexual identity.

Merle is filled with self-hatred as a result of her lesbian affair with the unnamed wealthy British woman in London. Yet I want to argue that while Marshall may not have always been the most enlightened writer regarding queer characters (in her LitHub essay, King traces an evolution in Marshall’s attitude in later novels), one can argue that at least part of Merle’s self-hatred might arise from the fact that her affair led her to lose access to her daughter after her husband left her.

Further, her unnamed lover was white and wealthy, and thus able to manipulate her. There are indeed no healthy and egalitarian same-sex relationships in this novel, but one might say the same about heterosexual relationships.

A Healing Connection

There is one exception to my statement above. While many of the characters come to a tragic end, Merle and Saul find a sexual connection that heals. To be sure, this is no happily-ever-after story. Yet these two are able to share an intimacy that is not just physical, but emotional as well.

They recognize that in the world in which they live, a relationship between the two of them is impossible, yet as a result of their connection they both come to understand what it is they must do next.

Saul is finished with fieldwork. The program to address poverty in Bournehills will continue, though in diminished form and without Saul. He hopes to go back to Stanford to “recruit and train young social scientists from overseas … that’s the best way: to have people … carry out their own development programs.”

Merle is bound for Africa, to find her daughter, even though she doesn’t know whether her former husband will “chase [her] from his door.” But she knows as well that she will eventually return to Bournehills.

“A person can run for years but sooner or later he has to take a stand in the place which for better or worse, he calls home,” she says, “and do what he can to change things there.”

It’s very much a conclusion and a recognition for our times—a time in which so many of us recognize that the work of change has to begin at the local level and with full recognition of and respect for the diversity that surrounds us.

But the conclusion of the novel takes me back to the story of Allen. He is the one who drives first Merle and then Saul to the airstrip so they can embark on the next stage of their respective lives. Allen has decided to stay behind on the island after they leave, for reasons that are not clear to Saul or Merle.

But we have seen Allen struggling with his own past—his upbringing of small-minded conformity—following the death of Vere and Allen’s recognition of his love for him. One senses that although he remains on the island, Allen will embark on his own quite profound and possibly joyous journey without ever leaving Bourne.

We might even think of those men out on the balcony who Merle points out to Saul near the beginning of the novel. Merle described them in negative terms, but Allen may see them differently. He may see in them the possibility of embracing his true identity and achieving an acceptance he has never had.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside of Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

See also: Inspiration from Classic Caribbean Women Writers.

The post The Chosen Place, The Timeless People by Paule Marshall (1969) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 25, 2023

Walking with Anne Brontë: Insights and Reflections

Walking with Anne Brontë: Insights and Reflections (edited by Tim Whittome, 2023) makes a passionate case for elevating the youngest of the Brontë sisters to her rightful place in English literature.

A collection of essays and personal reflections by Anne Brontë scholars and aficionados, this book will go a long way to the understanding and appreciation of Anne’s fortitude as a woman and her genius as a writer.

The following is excerpted from Tim Whittome’s Introduction to Walking with Anne Brontë, reprinted with permission.

. . . . . . . . . .

“It is a sad fact that Anne Brontë has come to be regarded by posterity as the Cinderella of the famous trio of sisters. Critics have been off-hand about her two novels, tending to dismiss them as mere talent against her sisters’ genius.” (Arnold Craig Bell, The Novels of Anne Brontë, 1992)

. . . . . . . . . .

“[Anne Brontë] has been passed over—both as a writer and as an individual—by successive Brontë biographers as less than nothing, or dismissed with a gesture of condescension as affording only a pale replica of her sisters’ genius … For in the last resort Anne Brontë must be judged by the high character which she displayed not only at the end but at every turning in her life. It is for what she was, quite as much as for what she created, that one wants to know more of her.” (Winifred Gérin, Anne Brontë, 1959)

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Anne Brontë

. . . . . . . . . .

“Dear gentle Anne,” as Charlotte Brontë’s friend Ellen Nussey viewed the youngest Brontë sibling, has traditionally been many people’s impressions of Anne Brontë. In recent decades, however, there has been far more of a focus on what Juliet Barker has referred to in her seminal biography of the Brontës as Anne’s “core of steel.”

This has been coupled with an admiration for Anne’s own stated desire to “tell the truth” in her two novels and a sense that her personal attributes of courage and duty may well have exceeded those exhibited by Charlotte and Emily.

These enduring qualities have steadily come to replace much of the frequently dismissive personal comments and ambiguous literary commentary that bizarrely defined Anne’s reputation in the writings of early Brontë biographers and interpreters.

. . . . . . . . . .

Walking with Anne Brontë is available

on Amazon US and Amazon UK

. . . . . . . . . .

Discarding unfair commentary and grudging admirationI decided to open this introduction with commentary from some of the writers who have chosen to highlight some of this denigration, if only to destroy it.

Even some of Anne’s own early biographers such as W. T. Hale were apparently not too sure how far they could go in admiring her. In life, things were never easy for Anne Brontë; and in death, her legacy has frequently been dismissed as if it has been all too much and too unreal to have three talents in one family.

This present work is unfortunately littered with unfair commentary about the youngest Brontë sibling by other writers—I consider May Sinclair (The Three Brontës, 1912) to be among the worst of the early writers along with Ellis Chadwick who saw only two geniuses (Emily and Charlotte) in the family and everyone else as contributing to making them sound even better.

Another early Brontë biographer, Clement Shorter, opened a description of Anne in The Brontës and Their Circle (1914) by proclaiming that both “Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall would have long since fallen into oblivion but for the inevitable association with the romances of her two greater sisters” (my emphasis added).

While some of Anne Brontë’s more recent biographers and critics have successfully emulated the earlier panache of these earlier Brontë scholars and have emerged with fully engaging accounts, others have demonstrated the tactical aplomb of good defense lawyers with strength-based assessments of their “client.”

In a similar way, my coauthors and I have also chosen to shine a spotlight on Anne’s earlier critics if only swiftly to destroy their potential reach and acceptance with fairer academic and personal assessments—assessments designed (with hopefully some panache added) to override the hasty conclusions of former prejudiced judges and to convince the jury of current readers with a more judicial-minded reasoning behind our loyalty to Anne.

Even today, some of the older and more prejudiced opinions prevail; and it is reasonable to add, since I live here, that Anne Brontë is not very well known in the United States.

In the context of the Brontë family

For those who are familiar with Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen, it would not be entirely inaccurate to suggest that Anne’s profile here is not that much greater than that of Margaret Dashwood, the younger sister of Elinor and Marianne—in other words, Anne has a tendency to be viewed as a character of marginal interest who occasionally distracts the otherwise disengaged reader with her prattle.

Working down the age range from the eldest to the youngest of the Brontë siblings who survived childhood, it has often seemed to me that the exhaustion that surrounds intense literary and other critical attention on members of the Brontë family typically stops at Emily.

In the process, Branwell Brontë is largely dismissed as too great a problem while their elder siblings Maria and Elizabeth sadly died too young to leave much of a trail for biographers and critics.

It is almost superfluous to say that this paradigm has led to Anne inevitably becoming overshadowed or just “included” in other critical works that primarily focus on Charlotte and Emily. I am surely not the only admirer of the Brontës who has found this highly annoying and irritating.

If instead of working our way down from Charlotte’s undeniable literary achievements, we were to work ourselves up from looking into the literary and personal world of the youngest to the eldest surviving sibling, what would the literary world think if we were still to stop after admiring Emily’s life and achievements and decided to ignore Charlotte? The idea would be unthinkable, right?

Forgetting the brilliant writer of Jane Eyre and Villette would seem irrational and even criminal in literary circles. It seems superfluous to point out that their troubled brother, Branwell, is typically viewed sparingly in both directions.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Impressive Lessons of Agnes Grey

. . . . . . . . . .

In short, my fellow authors and I feel that it should be just as unthinkable to ignore Anne’s literary legacy as the compelling writer of Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, fifty-nine beautiful poems, two self-penned “diary papers,” and five interesting or heartbreaking letters as it would be to ignore Charlotte’s.

Biographer Edward Chitham, at the 1994 Anne Brontë conference organized by the Brontë Society in Scarborough, had every reason for saying at the outset of one of the talks that he was an “Anne person.” He still is, as am I, and several writing here would assert the same.

Taking Mr. Chitham’s memorable comment as the inspiration for much of my own devotion to the memory of Anne, I wanted to put together an anthology of like-minded admirers of the youngest Brontë.

Our goal has been to bring together a “Team Anne” approach toward showcasing Anne’s literary talents and interesting personality to those that either have not heard of her, avoid thinking too much about her achievements if they have, or who have too often been wary of declaring their deep affection for her in company otherwise disposed to revere Charlotte and Emily as the only writers of consequence in the family.

We also hope that Walking with Anne Brontë will be viewed as a worthy addition to the growing body of work written by those who have already absorbed the lessons of Anne Brontë’s life and who understand the literary power of her novels and poetry.

In this regard, I was very struck by a comment that Samantha Ellis wrote in Take Courage in which she was surprised to discover that “most of the volunteers” who work for the Brontë Parsonage and Museum “say that Anne is their favorite.”

Ms. Ellis is one of my favorite interpreters of Anne’s life and work, and she goes on to wonder:

“Why she is ignored, or written off as boring? Why isn’t she read as much as her sisters? Why was her work suppressed, why is it underrated even now, and what does that say about what women still are and aren’t allowed to say? And what can I learn from her life and from her afterlife?” (Samantha Ellis, Take Courage, 2017)

These are typical reflections when it comes to thinking about Anne Brontë. As we walk with Anne and listen to some of her own insights and reflections in the pages ahead, readers will hopefully come to understand more of why Ms. Ellis was prompted to ask these questions.

Most of the time when many of us look at the Brontë literary landscape, we find ourselves wanting to learn as much about Anne as scientists eager to study some interesting geological formation in a hitherto undiscovered or overlooked country …

. . . . . . . . . .

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

. . . . . . . . . .

I need to make it clear to our readers from the outset that while everyone writing in this book fully admires the literary achievements of Charlotte and Emily Brontë and is as devoted to them as they are to Anne, we do rightly feel a mixture of surprise and sense of aggrievement that Anne is the overshadowed sibling among the three sisters.

We feel this loss as unwarranted, and like Elizabeth Langland has said in a memorable conclusion to her study of Anne in Anne Brontë: The Other One, we really need to flip Mary Ward’s earlier assessment of Anne as “like them [Emily and Charlotte], yet not with them” to “unlike them, yet with them.”

I have always remembered and cherished this defiant and memorable observation and it helped to shape my subsequent appreciation of Anne in the years since.

Those who do end up reading Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall could be forgiven for asking why it has seemed so hard for others to see the intricacies of this unique “geological” literary formation: Is it because one or both dusty books can only be seen on a hard-to-reach upper shelf or are only available to the knowing reader online as is the case with my local library system?

Anne Brontë used to love the “distant prospects” on the moor above Haworth according to Charlotte in a letter she wrote to her literary reader, William S. Williams, May 22, 1850.

Maybe this is how not Anne’s, but Emily’s and Charlotte’s literary reputations have been seen by those who choose to focus their effortless attention on the brightest of the distant stars and not on the more intricate shades of the abundant life nearby that maybe requires a variety of instruments and tools to see.

For me, either I can find Anne in those same distant prospects of sunrises, sunsets, and bright stars or I can find her close by requiring my closest attention. Rewardingly so, it has to be said, and I would argue that it is better to view the achievements of all three sisters in the same way.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Tim Whittome: Tim is originally from England and spent all of his childhood and early adulthood there, and now lives in Washington State. He first “walked” with Anne Brontë when he was in his late twenties; and he has been inspired by her ever since. Tim is devoted to honoring the memory of not just Anne Brontë, but also those of Anne and Margot Frank. In 2021, Tim edited and published “Meeting” Anne Frank, which he has donated many copies of to those who knew Anne and Margot, to members of the British and Dutch royal families, various luminaries in the Anne Frank world, and school and public libraries.

The post Walking with Anne Brontë: Insights and Reflections appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 21, 2023

Thus Far and No Further by Rumer Godden (1946)

Thus Far and No Further by Rumer Godden is this prolific midcentury novelist and memoirist’s first memoir, published in 1946. It chronicles her brief sojourn in Kashmir India, where she lived briefly with her two young daughters on a tea plantation.

Though not as enduring as her novels nor her other memoirs, this slim book, her sixth overall, was well received by readers and critics.

Godden’s characteristically evocative writing captures the time she spent in Rungli Rungliot in Darjeeling in Northeast India. Some of the editions of this now rather obscure book are, in fact, titled Rungli Rungliot.

A beautiful story, delightfully illustrated, it is filled with gentle wisdom. One of the well-known passages is as follows:

“In good company your thoughts run, in solitude your thought is still; it goes deeper and makes for itself a deeper groove, delves. Delve means ‘dig with a spade;’ it means hard work. In talk your mind can be stretched, widened, exhilarated to heights but it cannot be deepened; you have to deepen it yourself.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Rumer Godden

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review by John C. Goodbody in The Boston Globe, May 9, 1946: “Living Away from Crowds and Liking It”

Fleeing from complex, war-ruffled Calcutta of 1941, British novelist Rumer Godden escaped for six months to the Himalaya foothills where she conducted her own experiment of living away from the crowds and liking it.

On the level this autobiographical record is an exquisite monument in prose, erected in memory of her days of isolation by one of the few really talented stylists of today.

On another level, half-hidden beneath the beguiling simplicity of the diary form, the book becomes an absorbing study of the value of solitude in contemporary society. It is easily Miss Godden’s greatest achievement, and a convincing demonstration that she is far more than the talented literary virtuoso revealed in her last novel, “Take Three Tenses.”

When you leave the stench and confusion of Calcutta and climb perilously up the winding Teesta River valley to Darjeeling, you find yourself in a new world-a fresh, green, windswept world of tea terraces, sprawled against the rugged foothills of the jagged Himalaya range.

Miss Godden went beyond Darjeeling to a bungalow on a tea plantation at Chinglam. With her she had her two small daughters, a Swiss governess, a small retinue of Indian servants and four Pekinese.

Most of the entries in her journal are concerned with the new everyday world in which the author found herself:

“There are only a few things in these notes, Chinglam and its hills and valleys, work, flowers, children, animals, servants; there is nothing else because there was nothing else.”

It was a world of quiet sounds and vivid colors and strange tastes firmly bounded by routine.

Miss Godden learned the meaning of the Hindu proverb: “You only grow when you are alone.” She discovered that she could ration worry by hard work.

“The Buddhists here put their prayer flags where the wind will blow them and their prayer wheels in the stream where the water will turn them and get on with their work while the prayers are said. I think that is wisdom.”

But in the end, she knows she must with her retreat. Her solitude is not an end in itself, but a reprieve. After a wonderful Christmas — perhaps the best sequence of the book — Miss Godden leaves Chinglam to face again the challenges of society in the lowlands.

The most rewarding quality in this book is the author’s style, which seems to thrive when removed from the compulsions of the novel form. It is simple, incisive, evocative; it makes skillful use of repetition; it appeals directly to the senses. It invests this slim book with the special aura of craftsmanship.

More memoirs and biographies by Rumer Godden

A Time to Dance, No Time to Weep (1987) A House with Four Rooms (1989) Two Under the Indian Sun (with sister Jon, 1966). . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Thus Far and No Further by Rumer Godden

Reader discussion on Goodreads Library Thing Full text on IssuuThe post Thus Far and No Further by Rumer Godden (1946) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 19, 2023

The Impressive Lessons of Agnes Grey by Anne Brontë (1847)

This analysis of Agnes Gray by Anne Brontë (1847) discusses the significance of the first novel by the youngest Brontë sister. Originally published in the Brontë Society Transactions (now titled Brontë Studies,Volume 21, 1993). Reprinted by permission of Timothy Whittome (Walking with Anne Brontë, 2023).

“It leaves no painful impression on the mind — some may think it leaves no impression at all.” Thus wrote one reviewer in the Atlas on January 22, 1848. I suspect that few of Anne Brontë’s readers would easily sympathize with this view, and it is the purpose of this essay to illustrate why I disagree with the Atlas.

The reviewer also states: “There is a want of distinctness in the character of Agnes, which prevents the reader from taking much interest in her fate.”

Yet, for all this skepticism, Agnes Grey does leave an impression on the mind, and it is one not altogether without a feeling of pain, as also does the fate of Agnes, herself; arouse interest and concern.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Anne Brontë

. . . . . . . . . . .

What is first necessary, though, is to detach the novel from both Jane Eyre (Charlotte Brontë) and Wuthering Heights (Emily Brontë) because a regular misjudgment is to compare the three novels as if they were all competing and tending towards the same end.

And, in this competition, Agnes Grey, it is said, either falls by the wayside or arrives a poor third. Yet Agnes Grey is not in competition with either novel, and even if one were to pursue that line of thinking, it would be fair to say that neither Jane Eyre nor Wuthering Heights reaches the clarity and personal vision aspired to by Anne Brontë in the unfolding of Agnes’s story.

Anne reaches for a separate, and no less distinct, voice from that demonstrated by both Emily and Charlotte, and she successfully acquires that distinctiveness.

Eschewing both the “remarkable events” of Jane Eyre and the robust and colorful passion of Wuthering Heights, Anne finds a voice that is firm, persuasive, quiet, and restrained, as well as uncluttered and clear.

Introducing Edward Weston

From the outset, Agnes’s tale unfolds in a calm and undistracted manner. As Anne herself so often did, Agnes keeps most of her inner thoughts and pleasures to herself. Thus can Agnes’s mother say: “Mr. Weston! I never heard of him before.”

She is assured by Agnes that she has, but her mother’s confusion still typifies so much of both Anne and Agnes’s inner sense of reserve, and to pass comment on Agnes’ self-control and self-possession is also to pass similar comment on Anne’s.

Edward Weston’s ultimate engagement to Agnes also illustrates the same quietly impassioned approach by Anne Brontë to her work:

“You must have known that it was not my way to flatter and talk soft nonsense, or even to speak the admiration that I felt; and that a single word or glance of mine meant more than the honied. phrases and fervent protestations of most other men.”

Edward Weston is certainly no Edward Rochester or Heathcliff, and Anne has no urgent feeling inside her that would have created him as such, and so despite her intermittent involvement in the intrigues of Gondal, she doesn’t aspire to the style of writing so fervently adopted by Emily and Charlotte.

This is not to denigrate the achievement of either of her sisters, merely to suggest that Anne had a morally different set of values to pursue and that she successfully whispers these into the ears of her readers throughout her writing of Agnes Grey.

Thus Weston is very much “a man of strong sense, firm faith, and ardent piety, but thoughtful and stern.” He is also a man of “true benevolence, and gentle, considerate kindness.”

In Agnes’s feelings for Hatfield’s curate, Anne herself, whether subconsciously or not, by shedding some of the more flirtatious attributes of her own father’s curate, William Weightman, arrives at a more refined portrait of Weightman that is based loosely, but recognizably, on his compassionate concern for the poor of Haworth.

The author’s real-life parallels with her character

It is with some interest that we can pursue the thought that Agnes is nearly twenty-three when she leaves Horton Lodge to help at her mother’s school. It is then September, and in 1842, after Anne Brontë had been with the Robinson family at Thorp Green for two and a half years, William Weightman died that autumn, when Anne was also nearly twenty-three.

Therefore, what happens subsequently to Agnes in Agnes Grey is surely, in the greater part, wish fulfillment. It is significant, also, that there is such a long break with virtually no news about Weston.

His reappearance, nearly nine months later, seems so sudden; it is almost as if Anne’s imagination was reverting to those happy moments with Emily of raising people from amongst Gondal’s sleeping dead. Charlotte’s novels reveal a similar self-indulgence.

Not that Edward Weston dies, of course, but William Weightman did, and if, as seems likely, Anne had strong feelings for him, these feelings surely resurface in Agnes’ subdued, but quite ardent love for Edward Weston.

Charlotte’s portrayal to Ellen Nussey in early 1842 of a shy Anne being watched in church by William Weightman is mirrored in Anne’s portrait of Agnes, herself, in church listening to and admiring Weston’s sermons and readings. How cruel it would have been for Agnes if he had died!

Anne, therefore, uses her powerful imagination to recreate the inner turmoil of her life — a turmoil often so painfully invisible to others. Agnes also has three children, and, as Edward Chitham demonstrates in his biography of Anne. Anne in her own life may have wished for children of her own that she could both love and teach.

Yet Anne’s suggested feelings for Weightman as revealed through Agnes’s feelings for Weston and her subsequent engagement to him in a scene of perfect quiet in the town of A– are not the only themes of interest in the novel, for there are three others, at least, which are no less important, and just as revealing of Anne’s thoughts and concerns.

The enviable Rosalie Murray

First, there is Agnes’s complex and vivid association with Rosalie Murray. Edward Chitham suggests that Anne toys with the personality of Rosalie as she might well have grappled with an unwanted, or perhaps yearned for, part of herself, just as Emily tackles her inner persistent self in the character of Heathcliff. It is worth examining this point.

Here is Agnes deliberating on the question of beauty:

“They that have beauty, let them be thankful for it, and make a good use of it, like any other talent … it is a gift of God, and not to be despised. Many will feel this, who have felt that they could love, and whose hearts tell them they are worthy to be loved again, while yet they are debarred, by the lack of this, or some such seeming trifle from giving and receiving that happiness they seem almost made to feel and impart.

As well might the humble glow-worm despise that· power of giving light, without which the roving fly might pass her and repass her a thousand times and never light beside her; … the fly must seek another mate, the worm must live and die alone.”

Rosalie, according to Agnes, believes that Agnes would have wished to have been like her. However, although Agnes notes Rosalie’s “heartless vanity,” there is some, perhaps subconscious, envy in her words “I did not – at least, 1 firmly believe 1 did not.”

As with a number of other emotions expressed in the novel, Agnes’s strong feelings need to be rationalized down to something both sensible and constructive. Any envy that Agnes may have felt, therefore, is very much qualified. She goes on to wonder:

“… why so much beauty should be given to those who made so bad a use of it, and denied to some who would make it a benefit to both themselves and others.”

So Agnes admires her pupil’s beauty and is convinced that she would have used the corresponding attraction better. Yet this is clearly not all she admires about her. Earlier on, while musing on her visits to Nancy Brown and hearing of all the goodwill towards Weston, Agnes reflects on the influence she suffers from the Murray girls:

“And I, as 1 could not make my young companions better, feared exceedingly that they would make me worse —would gradually bring my feelings, habits, capacities to the level of their own, without, however, imparting to me their light-heartedness and cheerful vivacity.”

Agnes goes on to chronicle what she calls the “gross vapours of earth,” and her own supposed debasement which Weston’s presence helps to alleviate as “the morning star in my horizon, to save me from the fear of utter darkness.”

Needless to say, the most crucial point is Rosalie’s “cheerful vivacity.” and this Agnes feels she won’t impart, though it has to be the one, of all Rosalie’s qualities, Agnes would most have liked to feel.

Now we know that Anne Brontë was not, herself, a fluent and easy talker, so we can infer from many of Agnes’s remarks on Rosalie that Anne might have admired those qualities but shrank from seeing them misused in the hands of the wrong people.

Later on, Agnes was to be amazed at Matilda’s easy-flowing discourse, while finding her own conversation with Weston to be difficult. Their strength belongs to a different sort of communion, and unlike a very bitter Lady Ashby, Agnes has no cause to repent her own marriage. Subject to Agnes’s cautionary remarks about her visit to Rosalie at Ashby Park, we feel most sympathy towards this difficult pupil at this point.

Anne’s writing, which leaves so much to the imagination, is more vivid for what it doesn’t say, and we are left to fill in in our minds the sheer vastness of Rosalie’s isolation at Ashby Park.

There is little doubt that Anne is at her most lively when she is involved with Rosalie and there is a sparkle and a vivacity which contrasts markedly with the quieter tone of the rest of the novel. Rosalie’s liveliness, it has to be said, does envelop Agnes as well, as we follow Agnes in looking for Weston both at church and amongst the villagers.

Agnes cannot, for example, avoid glancing towards the door when she is visiting Nancy Brown, and she also wishes not to be seen as the equivalent of a domestic! Perhaps Anne is pointing here towards her leniency towards the flirtatious extravagance of the Robinson girls?

. . . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy …

The Brontë Sisters’ Path to Publication

. . . . . . . . . . .

The shy Agnes, like Anne, may in part have wished to share in this “cheerful vivacity,” but even so, it is also true that Agnes is desperate both to guide Rosalie and to teach her an awareness of her faults. It is clear to Agnes — as it was to Anne — that “excessive vanity, like drunkenness, hardens the heart, enslaves the faculties, and perverts the feelings …”

Agnes assumes the mantle of a teacher determined to achieve some good in the world, or, as Anne puts it when prefacing the second edition of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall:

“I would fain contribute my humble quota towards so good an aim, and if I can gain the public ear at all, I would rather whisper a few wholesome truths therein than much soft nonsense.”

There are obvious echoes of Edward Weston’s engagement to Agnes here, but, even if Agnes fails to change Rosalie, the fact of the determination is still important in helping us to understand Anne’s real-life efforts concerning the Robinson girls, including some success in helping to prevent a disastrous engagement for one of them.

Perhaps as a final point on Agnes’s involvement with Rosalie Murray — in which Anne most assumes the mantle of a writer’s task of amusing the reader, and the teacher’s mantle of instructing the same. It can be said that Charlotte may have recreated the character of Rosalie in Ginevra Fanshawe in Villette.

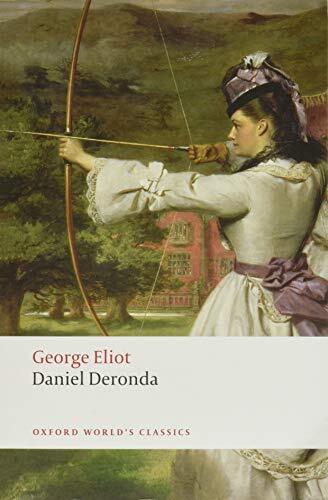

It is also possible that George Eliot may have mused over her for the creation of Gwendolen Harleth in Daniel Deronda. This may well be running with an idea and taking it too far, but, despite the difficulty of proving anything, there are similarities between Gwendolen and Rosalie in their self-confident mastery before marriage and their helpless despair afterward.

Agnes’s deep isolation as a governess

The second area of interest in Agnes Grey is the deep isolation of Agnes in both her governess positions. Deprived of kindness, surrounded by brutal hostility at the Bloomfields, and deprived of satisfying friendships at the Murrays, Agnes becomes very isolated.

She observes, rather than participates in, what goes on around her. In describing the friends of Rosalie and Matilda, Agnes observes that they “talked. over me or across, and if their eyes, in speaking, chanced to fall on me, it seemed as if they looked on vacancy …”

Anne builds up an image, here, of the discreet governess lingering slightly behind, always listening, and rarely talking or taken much notice of. The shutting of a carriage door in Agnes’s face by Hatfield would seem to illustrate the thoughtless insensitivity meted out to governesses at the time.

Agnes then says, with emphasis, “I was lonely.” She goes on to detail how she had seen no one:

“… to whom I could open my heart, or freely speak my thoughts with any hope of sympathy, or even comprehension; … whose conversation was calculated to render me better, wiser, happier than before, or who, as far as I could see, could be greatly benefited by mine. My only companions had been unamiable children, and ignorant, wrong-headed girls …”

Excluded from church and meeting Weston there, Agnes seeks refuge in poetry — her own or others’ — and chronicles the loneliness and isolation of her life in “pillars of witness.”

Anne’s handling of Agnes’s isolation is both sensitive and impressive. Her economy of language is as different from Charlotte’s handling of Jane Eyre’s flight from Rochester after their aborted wedding day as it is as powerful and effective.

It is worth comparing the writing of both Anne and Charlotte to illustrate the difference and also the power of both. Here is Agnes, and one may suggest Anne as well, speaking of her inner sense of turmoil, and of her response to her crisis:

“I was a close and resolute dissembler … My prayers, my tears, my wishes, fears, and lamentations were witnessed by myself and Heaven alone. When we are harassed by sorrows or anxieties, or .long oppressed by any powerful feelings which we must keep to ourselves, for which we can obtain and seek no sympathy from any living creature, and which yet we cannot, or will not wholly crush, we often naturally seek relief in poetry — and often find it too — whether in the effusions of others, which seem to harmonize with our existing case, or in our own attempts to give utterance to those thoughts and feelings in strains less musical … but more appropriate, and therefore more penetrating and sympathetic, and, for the time, more soothing, or more powerful to rouse and to unburden the oppressed and swollen heart.”

Agnes’s poetry comforts her, and she manages to deal with her crisis without plunging to the depths of Jane Eyre’s poverty, or Heathcliff’s self-destruction. We may deduce from this that Anne, herself, would have similarly dealt with her feelings for William Weightman.

Agnes’s response is wholly in keeping with Anne’s personality, and is further illustration of the way Anne projects her interests, concerns, and shy voice into her subject matter.

Agnes, as has been shown, avoids the extremity of manifesting her despair. in degradation, and avoids, too, pushing Edward Weston towards a similar abyss of self-destruction. Agnes conceals her agitation by calmly showing her self-sufficiency in going to help in her mother’s school.

The role of religion in Agnes Grey

Yet another way that we can listen to Anne’s beating heart comes in her depiction of religion, the third of the main areas of interest in Agnes Grey. Agnes, after her arrival at Horton Lodge, finds herself quickly rejecting Hatfield’s idea of God as a “terrible taskmaster.”