Nava Atlas's Blog, page 20

April 13, 2023

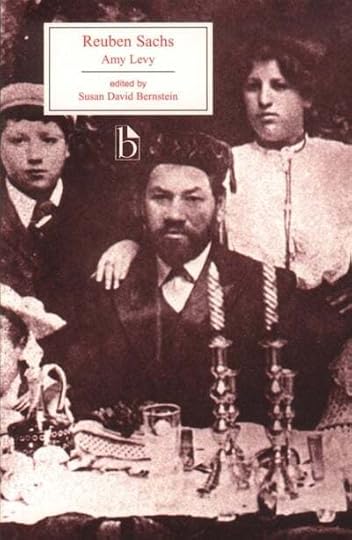

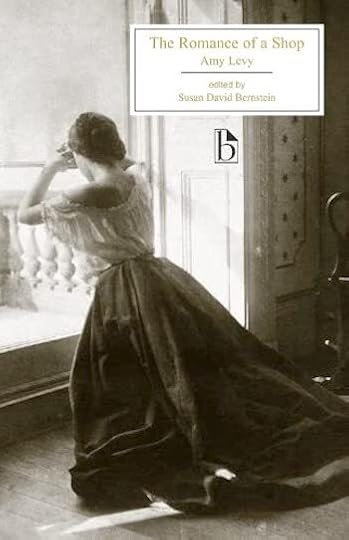

Amy Levy, Author of Reuben Sachs

Amy Levy (November 10, 1861 – September 9, 1889) was a British essayist, novelist, and poet who, despite talent and accomplishment, died by her own hand when not quite twenty-eight years old.

Her best-known work was Reuben Sachs, the 1888 novel that examined Jewish life in Victorian England, something quite unusual in its time. The following year, she published a significant collection of her poetry, A London Plane Tree and Other Poems.

Amy was the second Jewish woman at Cambridge University, and as the first Jewish student at Newnham College, Cambridge. She was becoming known for her feminist positions and friendships with others who would become known as “New Women.”

Amy had relationships with both men and women, though she seemed to prefer the latter. She associated with those who were politically active circles in London in the 1880s.

Early promise; a life cut short

She showed early promise as a poet, publishing A Minor Poet and Other Verse in 1884 when she was just shy of twenty-four. Some of the poems had been published in 1881 in a pamphlet she had printed while at Cambridge, titled Xantippe and Other Poems. Her early literary successes notwithstanding, the mood of her poems, many of which were melancholic and pessimistic, reflected a person of great sensitivity, with a tendency to depression.

Beginning in 1886, wrote several essays on Jewish culture and literature for The Jewish Chronicle. The best known is The Ghetto at Florence. Others included The Jew in Fiction, Jewish Humour, and Jewish Children.

What’s known of Amy Levy’s life confirms that she suffered from major depression from the time she was young. As she grew into womanhood, her depression deepened, in part due to the turmoil of her romantic relationships. She was also distressed by her increasing deafness.

On September 9, 1889, just two months shy of her twenty-eighth birthday, she committed suicide at her parents’ home in Endsleigh Gardens by inhaling carbon monoxide. The first Jewish woman to be cremated in England, her ashes are interred at Balls Pond Road Cemetery in London.

Amy Levy had written a few short stories for Oscar Wilde’s magazine, The Women’s World. He wrote an obituary for her published in that magazine, in which he extolled her talents.

Of her best-known work, the 1888 novel Reuben Sachs, Persephone Books wrote of the contemporary reissued edition:

“Oscar Wilde observed: ‘Its directness, its uncompromising truths, its depth of feeling, and above all, its absence of any single superfluous word, make Reuben Sachs, in some sort, a classic.”

Julia Neuberger writes in her Preface, ‘This is a novel about women, and Jewish women, about families, and Jewish families, about snobbishness, and Jewish snobbishness,” while in the Independent on Sunday Lisa Allardice said: “Sadder but no less sparkling than Miss Pettigrew, Reuben Sachs is another forgotten classic by an accomplished female novelist. Amy Levy might be described as a Jewish Jane Austen.”

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

A brief chronology Amy Levy’s life and workThe following brief biography appeared in Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, London: Smith, Elder, & Co. (1885–1900).

Amy Judith Levy (1861–1889), poet and novelist, second daughter of Mr. Lewis Levy, by his wife Isabelle (Levin), was born at Clapham on November 10, 1861. Her parents were of the Jewish faith. She was educated at Brighton, and afterward at Newnham College, Cambridge. She early showed decided talent, especially for poetry, pieces thought worthy of preservation having been written in her thirteenth year.

In 1881 a small pamphlet of verse from her pen, Xantippe and other Poems, was printed at Cambridge. Most of the contents were subsequently incorporated with her second publication, A Minor Poet and Other Verse, 1884. Xantippe is in many respects her most powerful production, exhibiting a passionate rhetoric and a keen, piercing dialectic, exceedingly remarkable in so young a writer.

It is a defense of Socrates’s maligned wife, from the woman’s point of view, full of tragic pathos, and only short of complete success from its frequent reproduction of the manner of both the Brownings.

The same may be said of A Minor Poet, a poem now more interesting than when it was written, from its evident prefigurement of the melancholy fate of the authoress herself. The most important pieces in the volume are in blank verse, too colloquial to be finely modulated, but always terse and nervous.

A London Plane Tree and Other Poems, 1889, is, on the other hand, chiefly lyrical. Most of the pieces are individually beautiful; as a collection they weary with their monotony of sadness.

The authoress responded more readily to painful than to pleasurable emotions, and this incapacity for pleasure was a more serious trouble than her sensitiveness to pain: it deprived her of the encouragement she might have received from the success which, after a fortunate essay with a minor work of fiction, The Romance of a Shop, attended her remarkable novel, Reuben Sachs, 1889.

This is a most powerful work, alike in the condensed tragedy of the main action, the striking portraiture of the principal characters, and the keen satire of the less refined aspects of Jewish society. It brought upon the authoress much unpleasant criticism, which, however, was far from affecting her spirits to the extent alleged. In the summer of 1889, she published a pretty and for once cheerful story, Miss Meredith.

Within a week after correcting her latest volume of poems for the press, she died by her own hand in her parents’ house in London, on September 10, 1889.

No cause can or need be assigned for this lamentable event except constitutional melancholy, intensified by painful losses in her own family, increasing deafness, and probably the apprehension of insanity, combined with a total inability to derive pleasure or consolation from the extraneous circumstances which would have brightened the lives of most others.

She was indeed frequently animated, but her cheerfulness was but a passing mood that merely gilded her habitual melancholy, without diminishing it by a particle, while sadness grew upon her steadily, in spite of flattering success and the sympathy of affectionate friends.

She was the anonymous translator of Pérés’s clever brochure, “Comme quoi Napoléon n’a jamais existé.”

Her writings offer few traces of the usual immaturity of precocious talent; they are carefully constructed and highly finished, and the sudden advance made in Reuben Sachs indicates a great reserve of undeveloped power.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Major Works

Xantippe and Other Verse (1881)A Minor Poet and Other Verse (1884)The Romance of a Shop (1888) novel (republished in 2005, Black Apollo Press)Reuben Sachs (1888) (republished by Broadview Press and Persephone Books )— See an e-pub of the original edition A London Plane-Tree and Other Verse (1889)Miss Meredith (1889; a novel)The Complete Novels and Selected Writings of Amy Levy: 1861–1889

(published in 1993 by Melvyn New)

Biography and Criticism

Amy Levy: Her Life and Letters by Linda Hunt Beckham (2000)Amy Levy: Critical Essays by Naomi Hetherington and Nadia Valman (2010)More information and sources

Jewish Women’s Archive Wikipedia Wikisource Victorian Web Amy Levy: A London Poet Full texts on Project Gutenberg Listen on LibrivoxThe post Amy Levy, Author of Reuben Sachs appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 7, 2023

“A Chat About the Hand” – A 1905 essay by Helen Keller

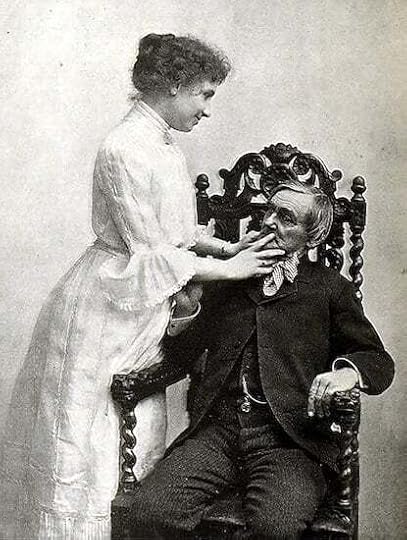

Helen Keller (1880 – 1968) was a prolific blind and deaf American author and disability rights activist. The 1905 essay by Helen Keller presented here, “A Chat About the Hand,” conveys in great detail how she communicated and sensed the world around her. At right, Helen Keller in 1904.

This entry in the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica illustrates how accomplished she was already (with decades to live yet ahead of her) at the age of thirty-one:

Helen Adams Keller was born in Tuscumbia, Alabama, in 1880. When barely two years old she was deprived of sight and hearing by an attack of scarlet fever. At the request of her parents, who were acquainted with the success attained in the case of Laura Bridgman, one of the graduates of the Perkins Institution at Boston, Miss Anne Sullivan was sent to instruct her at home …

From 1888 onwards, at the Perkins Institution, Boston, and under Miss Sarah Fuller at the Horace Mann school in New York, and at the Wright Humason school, Helen not only learned to read, write, and talk, but became proficient, to an exceptional degree, in the ordinary educational curriculum.

In 1900 she entered Radcliffe College, and successfully passed the examinations in mathematics, etc. for her degree of A.B. in 1904. Miss Sullivan, whose ability as a teacher was considered almost as marvelous as the talent of her pupil, was throughout her devoted companion.

The case of Helen Keller is the most extraordinary ever known in the education of blind deaf-mutes, her acquirements including several languages and her general culture being exceptionally wide.

She wrote The Story of My Life (1902), and volumes on Optimism (1903), and The World I Live in (1908), which both in literary style and in outlook on life are a striking revelation of the results of modern methods of educating those who have been so impacted by natural disabilities. (— Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911)

Helen Keller learned to communicate, as well as to sense the world, through her hand. Here, in an essay published in The Century Magazine, Volume 69, 1905. The photos presented here were part of the article, all of which are in the public domain.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Helen Keller

Photo by Whitman, 1905

. . . . . . . . . .

I have just touched my dog. He was rolling on the grass, with pleasure in every muscle and limb. I wanted to catch a picture of him in my fingers, and I touched him as lightly as I would cobwebs; but lo, his fat body revolved, stiffened and solidified into an upright position, and his tongue gave my hand a lick!

He pressed close to me, as if he were fain to crowd himself into my hand. He loved it with his tail, with his paw, with his tongue. If he could speak, I believe he would say with me that paradise is attained by touch; for in touch is all love and intelligence.

This small incident started me on a chat about hands, and if my chat is fortunate I have to thank my dog-star. In any case, it is pleasant to have something to talk about that no one else has monopolized; it is like making a new path in the trackless woods, blazing the trail where no foot has pressed before.

I am glad to take you by the hand and lead you along an untrodden way into a world where the hand is supreme. But at the very outset we encounter a difficulty. You are so accustomed to light, I fear you will stumble when I try to guide you through the land of darkness and silence.

The blind are not supposed to be the best of guides. Still, though I cannot warrant not to lose you, I promise that you shall not be led into fire or water, or fall in to a deep pit. If you will follow me patiently, you will find that “there ’s a sound so fine, nothing lives ’twixt it and silence,” and that there is more meant in things than meets the eye.

My hand is to me what your hearing and sight together are to you. In large measure we travel the same highways, read the same books, speak the same language, yet our experiences are different. All my comings and goings turn on the hand as on a pivot. It is the hand that binds me to the world of men and women.

The hand is my feeler with which I reach through isolation and darkness and seize every pleasure, every activity that my fingers encounter. With the dropping of a little word from another’s hand into mine, a slight flutter of the fingers, began the intelligence, the joy, the fullness of my life. Like Job, I feel as if a hand had made me, fashioned me together round about and molded my very soul.

In all my experiences and thoughts I am conscious of a hand. Whatever touches me, whatever thrills me, is as a hand that touches me in the dark, and that touch is my reality. You might as well say that a sight which makes you glad, or a blow which brings the stinging tears to your eyes, is unreal as to say that those impressions are unreal which I have accumulated by means of touch.

The delicate tremble of a butterfly’s wings in my hand, the soft petals of violets curling in the cool folds of their leaves or lifting sweetly out of the meadow-grass, the clear, firm outline of face and limb, the smooth arch of a horse’s neck and the velvety touch of his nose—all these, and a thousand resultant combinations, which take shape in my mind, constitute my world.

Ideas make the world we live in, and impressions furnish ideas. My world is built of touch-sensations, devoid of color and sound; but without color and sound it breathes and throbs with life.

Every object is associated in my mind with tactual qualities which, combined in countless ways, give me a sense of power, of beauty, or of incongruity: for with my hands I can feel the comic as well as the beautiful in the outward appearance of things. Remember that you, dependent on your sight, do not realize how many things are tangible.

. . . . . . . . . .

Helen Keller Reading Joseph Jefferson’s Speech

Photograph by C. M. Gilbert (1902)

. . . . . . . . . .

All palpable things are mobile or rigid, solid or liquid, big or small, warm or cold, and these qualities are variously modified. The coolness of a water-lily rounding into bloom is different from the coolness of an evening wind in summer, and different again from the coolness of the rain that soaks into the hearts of growing things and gives them life and body.

The velvet of the rose is not that of a ripe peach or of a baby’s dimpled cheek. The hardness of the rock is to the hardness of wood what a man’s deep bass is to a woman’s voice when it is low.

What I call beauty I find in certain combinations of all these qualities, and is largely derived from the flow of curved and straight lines which is over all things.

“What does the straight line mean to you?” I think you will ask.

It means several things. It symbolizes duty. It seems to have the quality of inexorableness that duty has. When I have something to do that must not be set aside, I feel as if I were going forward in a straight line, bound to arrive somewhere, or go on forever without swerving to the right or to the left.

That is what it means. To escape this moralizing you should ask, “How does the straight line feel?” It feels, as I suppose it looks, straight—a dull thought drawn out endlessly. It is unstraight lines, or many straight and curved lines together, that are eloquent to the touch.

They appear and disappear, are now deep, now shallow, now broken off or lengthened or swelling. They rise and sink beneath my fingers, they are full of sudden starts and pauses, and their variety is inexhaustible and wonderful. So you see I am not shut out from the region of the beautiful, though my hand cannot perceive the brilliant colors in the sunset or on the mountain, or reach into the blue depths of the sky.

Physics tells me that I am well off in a world which knows neither color nor sound, but is made in terms of size, shape, and inherent qualities; for at least every object appears to my fingers standing solidly right side up, and is not an inverted image on the retina which, I understand, your brain is at infinite though unconscious labor to set back on its feet.

A tangible object passes complete into my brain with the warmth of life upon it, and occupies the same place that it does in space; for, without egotism, the mind is as large as the universe. When I think of hills, I think of the upward strength I tread upon. When water is the object of my thought, I feel the cool shock of the plunge and the quick yielding of the waves that crisp and curl and ripple about my body.

The pleasing changes of rough and smooth, pliant and rigid, curved and straight in the bark and branches of a tree give the truth to my hand. The immovable rock, with its juts and warped surface, bends beneath my into all manner of grooves and hollows.

The bulge of a watermelon and the puffed-up rotundities of squashes that sprout, bud, and ripen in that strange garden planted somewhere behind my finger-tips are the ludicrous in my tactual memory and imagination.

My fingers are tickled to delight by the soft ripple of a baby’s laugh, and find amusement in the lusty crow of the barnyard autocrat. Once I had a pet rooster that used to perch on my knee and stretch his neck and crow. A bird in my hand was then worth two in the—barnyard.

My fingers cannot, of course, get the impression of a large whole at a glance; but I feel the parts, and my mind puts them together. I move around the house, touching object after object in order, before I can form an idea of the entire house.

In other people’s houses I can touch only what is shown me—the chief objects of interest, carvings on the wall, or a curious architectural feature, exhibited like the family album. Therefore a house with which I am not familiar has for me, at first, no general effect or harmony of detail.

It is not a complete conception, but a collection of object-impressions which, as they come to me, are disconnected and isolated. But my mind is full of associations, sensations, theories and with them it constructs the house.

The process reminds me of the building of Solomon’s temple, where was neither saw, nor hammer, nor any tool heard while the stones were being laid one upon another. The silent worker is imagination which decrees reality out of chaos.

Without imagination what a poor thing my world would be! My garden would be a silent patch of earth strewn with sticks of a variety of shapes and smells. But when the eye of my mind is opened to its beauty, the bare ground brightens beneath my feet, and the hedge-row bursts into leaf, and the rose-tree shakes its fragrance everywhere.

I know how budding trees look, and I enter into the amorous joy of the mating birds, and this is the miracle of imagination.

. . . . . . . . . .

Miss Sullivan reading to Helen by the hand

Photo by Whitman (n.d.)

. . . . . . . . . .

Twofold is the miracle when, through my fingers, my imagination reaches forth and meets the imagination of an artist which he has embodied in a sculptured form. Although, compared with the life-warm, mobile face of a friend, the marble is cold and pulseless and unresponsive, yet it is beautiful to my hand.

Its flowing curves and bendings are a real pleasure; only breath is wanting; but under the spell of the imagination the marble thrills and becomes the divine reality of the ideal. Imagination puts a sentiment into every line and curve, and the statue in my touch is indeed the goddess herself who breathes and moves and enchants.

It is true, however, that some sculptures, even recognized masterpieces, do not please my hand. When I touch what there is of the Winged Victory, it reminds me at first of a headless, limbless dream that flies toward me in an unrestful sleep.

The garments of the Victory thrust stiffly out behind, and do not resemble garments that I have felt flying, fluttering, folding, spreading in the wind. But imagination fulfills these imperfections, and straightway the Victory becomes a powerful and spirited figure with the sweep of sea-winds in her robes and the splendor of conquest in her wings.

. . . . . . . . . .

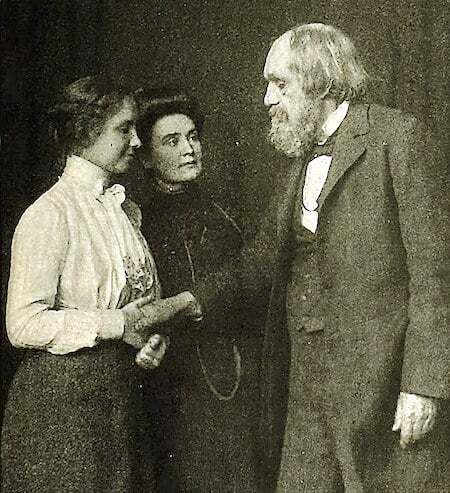

Helen, Anne Sullivan, and Edward Everett Hale

From a photograph by Marshall, n.d., early 1900s

. . . . . . . . . .

I find in a beautiful statue, beside perfection of bodily form, the qualities of balance and completeness. The Minerva, hung with a web of poetical allusion, gives me a sense of exhilaration that is almost physical; and I like the luxuriant, wavy hair of Bacchus and Apollo, and the wreath of ivy, so suggestive of pagan holidays.

So imagination crowns the experience of my hands. And they learned their cunning from the wise hand of another, which, itself guided by imagination, led me safely in paths that I knew not, made darkness light before me, and made crooked ways straight.

The warmth and protectiveness of the hand are most home felt to me who have always looked to it for aid and joy. I understand perfectly how the Psalmist can lift up his voice with strength and gladness, singing, “I put my trust in the Lord at all times, and his hand shall uphold me, and I shall dwell in safety.” In the strength of the human hand, too, there is something divine. I am told that the glance of a beloved eye thrills one from a distance; but there is no distance in the touch of a beloved hand. Even the letters I receive are

“Kind letters that betray the heart’s deep history,

In which we feel the presence of a hand.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Helen by the Piano

From a photograph by Whitman, n.d., early 1900s

. . . . . . . . . .

It is interesting to observe the differences in the hands of people. They show all kinds of vitality, energy, stillness, and cordiality. I never realized how living the hand is until I saw those chill plaster images in Mr. Hutton’s collection of casts. The hand I know in life has the fullness of blood in its veins, and is elastic with spirit.

How different dear Mr. Hutton’s hand was from its dull, insensate image! To me the cast lacks the very form of the hand. Of the many casts in Mr. Hutton’s collection I did not recognize any, not even my own. But a loving hand I never forget. I remember in my fingers the large hands of Bishop Brooks, brimful of tenderness and a strong man’s joy.

If you were deaf and blind, and could hold Mr. Jefferson’s hand, you would see in it a face and hear a kind voice unlike any other you have known. Mark Twain’s hand is full of whimsies and the drollest humors, and while you hold it the drollery changes to sympathy and championship.

I am told that the words I have just written do not “describe” the hands of my friends, but merely endow them with the kindly human qualities which I know they possess, and which language conveys in abstract words.

The criticism implies that I am not giving the primary truth of what I feel; but how otherwise do descriptions in books I read, written by men who can see, render the visible look of a face? I read that a face is strong, gentle; that it is full of patience, of intellect; that it is fine, sweet, noble, beautiful.

Have I not the same right to use these words in describing what I feel as you have in describing what you see? They express truly what I feel in the hand. I am seldom conscious of physical qualities, and I do not remember whether the fingers of a hand are short or long, or the skin is moist or dry. No more can you, without conscious effort, recall the details of a face, even when you have seen it many times.

. . . . . . . . . .

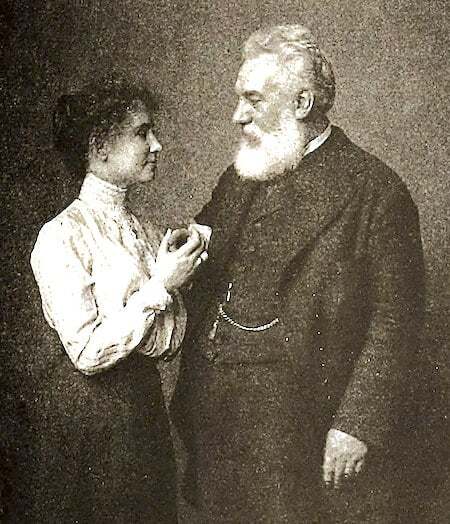

Helen and Alexander Graham Bell

Photograph by Marshall, n.d., early 1900s

. . . . . . . . . .

If you do recall the features, and say that an eye is blue, a chin sharp, a nose short, or a cheek sunken, I fancy that you do not succeed well in giving the impression of the person,—not so well as when you interpret at once to the heart the essential moral qualities of the face—its humor, gravity, sadness, spirituality.

If I should tell you in physical terms how a hand feels, you would be no wiser for my account than a blind man to whom you describe a face in detail.

Remember that when a blind man recovers his sight, he does not recognize the commonest thing that has been familiar to his touch, the dearest face intimate to his fingers, and it does not help him at all that things and people have been described to him again and again.

So you, who are untrained of touch, do not recognize a hand by the grasp; and so, too, any description I might give would fail to make you acquainted with a friendly hand which my fingers have often folded about, and which my affection translates to my memory.

I cannot describe hands under any class or type; there is no democracy of hands. Some hands tell me that they do everything with the maximum of bustle and noise. Other hands are fidgety and unadvised, with nervous, fussy fingers which indicate a nature sensitive to the little pricks of daily life.

Sometimes I recognize with foreboding the kindly but stupid hand of one who tells with many words news that is no news. I have met a bishop with a jocose hand, a humorist with a hand of leaden gravity, a man of pretentious valor with a timorous hand, and a quiet, apologetic man with a fist of iron.

When I was a little girl I was taken to see a woman who was blind and paralyzed. I shall never forget how she held out her small, trembling hand and pressed sympathy into mine. My eyes fill with tears as I think of her. The weariness, pain, darkness, and sweet patience were all to be felt in her thin, wasted, groping, loving hand.

. . . . . . . . . .

Helen exercising the sense of touch

From a photograph by Whitman, n.d., early 1900s

. . . . . . . . . .

Few people who do not know me will understand, I think, how much I get of the mood of a friend who is engaged in oral conversation with somebody else. My hand follows his motions; I touch his hand, his arm, his face. I can tell when he is full of glee over a good joke which has not been repeated to me, or when he is telling a lively story.

One of my friends is rather aggressive, and his hand always announces the coming of a dispute. By his impatient jerk I know he has argument ready for some one. I have felt him start as a sudden recollection or a new idea shot through his mind. I have felt grief in his hand.

I have felt his soul wrap itself in darkness majestically as in a garment. Another friend has positive, emphatic hands which show great pertinacity of opinion. She is the only person I know who emphasizes her spelled words and accents them as she emphasizes and accents her spoken words when I read her lips.

I like this varied emphasis better than the monotonous pound of unmodulated people who hammer their meaning into my palm.

Some hands, when they clasp yours, beam and bubble over with gladness. They throb and expand with life. Strangers have clasped my hand like that of a long-lost sister. Other people shake hands with me as if with the fear that I may do them mischief.

Such persons hold out civil finger-tips which they permit you to touch, and in the moment of contact they retreat, and inwardly you hope that you will not be called upon again to take that hand of “dormouse valor.”

It betokens a prudish mind, ungracious pride, and not seldom mistrust. It is the antipode to the hand of those who have large, lovable natures.

The handshake of some people makes you think of accident and sudden death. Contrast this ill-boding hand with the quick, skilful, quiet hand of a nurse whom I remember with affection because she took the best care of my teacher. I have clasped the hands of some rich people that spin not and toil not, and yet are not beautiful. Beneath their soft, smooth roundness what a chaos of undeveloped character!

All this is my private science of palmistry, and when I tell your fortune it is by no mysterious intuition or Gipsy witchcraft, but by natural, explicable recognition of the embossed character in your hand.

Not only is the hand as easy to recognize as the face, but it reveals its secrets more openly and unconsciously. People control their countenances, but the hand is under no such restraint. It relaxes and becomes listless when the spirit is low and dejected; the muscles tighten when the mind is excited or the heart glad; and permanent qualities stand written on it all the time.

As there are many beauties of the face, so the beauties of the hand are many. Touch has its ecstasies. The hands of people of strong individuality and sensitiveness are wonderfully mobile. In a glance of their finger-tips they express many shades of thought.

Now and again I touch a fine, graceful, supple-wristed hand which spells with the same beauty and distinction that you must see in the handwriting of some highly cultivated people. I wish you could see how prettily little children spell in my hand. They are wild flowers of humanity, and their finger motions wild flowers of speech.

Look in your “Century Dictionary,” or, if you are blind, ask your teacher to do it for you, and learn how many idioms are made on the idea of hand, and how many words are formed from the Latin root manus—enough words to name all the essential affairs of life.

“Hand,” with quotations and compounds, occupies twenty-four columns, eight pages of this dictionary, in all ten times as long as this essay. The hand is defined as “the organ of apprehension.”

How perfectly the definition fits my case in both senses of the word “apprehend”! With my hand I seize and hold all that I find in the three worlds—physical, intellectual, and spiritual.

Think how man has regarded the world in terms of the hand. All life is divided between what lies on one hand and on the other. The products of skill are manufactures. The conduct of affairs is management.

History seems to be the record—alas for our chronicles of war!—of the manœuvers of armies. But the history of peace, too, the narrative of labor in the field, the forest, and the vineyard, is written in the victorious sign manual—the sign of the hand that has conquered the wilderness. The laborer himself is called a hand.

The minor idioms are myriad; but I will not recall too many, lest you cry, “Hands off!” I cannot desist, however, from this word-game until I have set down a few. Whatever is not one’s own by first possession is second-hand. That is what I am told my knowledge is.

But my well-meaning friends come to my defense, and, not content with endowing me with natural first-hand knowledge which is rightfully mine, ascribe to me a preternatural sixth sense and credit to miracles and heaven-sent compensations all that I have won and discovered with my good right hand. And with my left hand too; for with that I read, and it is as true and honorable as the other.

By what half-development of human power has the left hand been neglected? When we arrive at the acme of civilization shall we not all be ambidextrous, and in our hand-to-hand contests against difficulties shall we not be doubly triumphant?

It occurs to me, by the way, that when my teacher was training my unreclaimed spirit, her struggle against the powers of darkness, with the stout arm of discipline and the light of the manual alphabet, was in two senses a hand-to-hand conflict.

No essay would be complete without quotations from Shakspeare. In the field which, in the presumption of my youth, I thought was my own he has reaped before me. In almost every play there are passages where the hand plays a part Lady Macbeth’s heartbroken soliloquy over her little hand, from which all the perfumes of Arabia will not wash the stain, is the most pitiful moment in the tragedy.

Mark Antony rewards Scarus, the bravest of his soldiers, by asking Cleopatra to give him her hand: “Commend unto his lips thy favoring hand.” In a different mood he is enraged because Thyreus, whom he despises, has presumed to kiss the hand of the queen, “my playfellow, the kingly seal of high hearts.”

When Cleopatra is threatened with the humiliation of gracing Cæsar’s triumph, she snatches a dagger, exclaiming, “I will trust my resolution and my good hands.” With the same swift instinct, Cassius trusts to his hands when he stabs Cæsar:

“Speak, hands, for me!” “Let me kiss your hand,” says the blind Gloster to Lear. “Let me wipe it first,” replies the broken old king; “it smells of mortality.” How charged is this single touch with sad meaning! How it opens our eyes to the fearful purging Lear has undergone, to learn that royalty is no defense against ingratitude and cruelty!

Gloster’s exclamation about his son, “Did I but live to see thee in my touch, I ’d say I had eyes again,” is as true to a pulse within me as the grief he feels. The ghost in “Hamlet” recites the wrongs from which springs the tragedy:

“Thus was I, sleeping, by a brother’s hand

At once of life, of crown, of queen dispatch’d.”

How that passage in “Othello” stops your breath—that passage full of bitter double intention in which Othello’s suspicion tips with evil what he says about Desdemona’s hand; and she in innocence answers only the innocent meaning of his words: “For ’t was that hand that gave away my heart.”

Not all Shakspeare’s great passages about the hand are tragic. Remember the light play of words in Romeo and Juliet where the dialogue, flying nimbly back and forth, weaves a pretty sonnet about the hand. And who knows the hand, if not the lover?

The touch of the hand is in every chapter of the Bible. Why, you could almost rewrite Exodus as the story of the hand. Everything is done by the hand of the Lord and of Moses.

The oppression of the Hebrews is translated thus: “The hand of Pharaoh was heavy upon the Hebrews.” Their departure out of the land is told in these vivid words: “The Lord brought the children of Israel out of the house of bondage with a strong hand and a stretched-out arm.”

At the stretching out of the hand of Moses the waters of the Red Sea part and stand all on a heap. When the Lord lifts his hand in anger, thousands perish in the wilderness. Every act, every decree in the history of Israel, as indeed in the history of the human race, is sanctioned by the hand. Is it not used in the great moments of swearing, blessing, cursing, smiting, agreeing, marrying, building, destroying?

Its sacredness is in the law that no sacrifice is valid unless the sacrificer lay his hand upon the head of the victim. The congregation lay their hands on the heads of those who are sentenced to death. How terrible the dumb condemnation of their hands must be to the condemned! When Moses builds the altar on Mount Sinai, he is commanded to use no tool, but rear it with his own hands.

Earth, sea, sky, man, and all lower animals are holy unto the Lord because he has formed them with his hand. When the Psalmist considers the heavens and the earth, he exclaims: “What is man, O Lord, that thou art mindful of him? For thou hast made him to have dominion over the works of thy hands.” The supplicating gesture of the hand always accompanies the spoken prayer, and with clean hands goes the pure heart.

Christ comforted and blessed and healed and wrought many miracle with his hands. He touched the eyes of the blind, and they were opened. When Jairus sought him, overwhelmed with grief, Jesus went and laid his hands on the ruler’s daughter, and she awoke from the sleep of death to her father’s love.

You also remember how he healed the crooked woman. He said to her, “Woman, thou art loosed from thine infirmity,” and he laid his hands on her, and immediately she was made straight, and she glorified God.

Look where we will, we find the hand in time and history, working, building, inventing, bringing civilization out of barbarism. The hand symbolizes power and the excellence of work.

The mechanic’s hand, that minister of elemental forces, the hand that hews, saws, cuts, builds, is useful in the world equally with the delicate hand that paints a wild flower or molds a Grecian urn, or the hand of a statesman that writes a law. The eye cannot say to the hand, “I have no need of thee.” Blessed be the hand! Thrice blessed be the hands that work!

See more full texts of classic works on this site.

The post “A Chat About the Hand” – A 1905 essay by Helen Keller appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

April 6, 2023

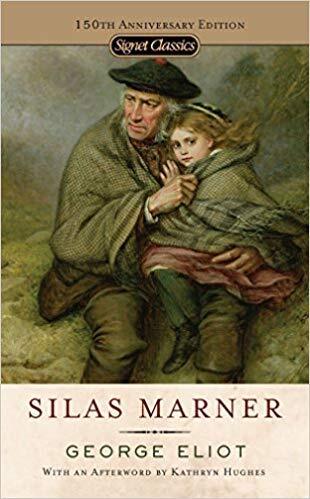

George Eliot’s Fictional Women: A 19th-Century Overview

George Eliot (1819 – 1880; pen name of Mary Ann Evans) has been recognized for her probing Victorian novels. Middlemarch is her arguably her greatest achievement, though most all of her novels were met with great critical and public acclaim.

Eliot’s writing was politically and socially driven, with many characters who are small-town individuals, some free thinkers, some eccentrics, others learned intellectuals. She drew her characters with great psychological depth whether they played major or minor parts in her narratives.

George Eliot’s heroines were no exception. From Adam Bede (1859), her first novel, through Daniel Deronda (1876), her last, her female characters were imagined fully formed, with dreams and desires of their own.

The following overview of Eliot’s fictional women is from Littell’s Living Age, Volume12, March 18, 1876. Alas, this insightful essay (which is in the public domain) is by an unidentified author.

. . . . . . . . . .

Middlemarch

. . . . . . . . . .

All of George Eliot’s most brilliant studies of female character display, like her writings in general, a certain definiteness of bent, in which one characteristic is uppermost, and is painted with a distinctness of outline and clearness of touch which make the character containing it memorable.

She is very fond of dwelling on the deep conventional vein in women, and has sometimes even made it attractive, though much oftener the reverse. In Middlemarch there were two such characters, Celia Brooke and Rosamond Vincy.

Though Rosamond was by far the deeper study of the two, and presented a picture of conventional sweetness, prettiness, selfishness, and superficiality, such as it will not be easy to find a companion for in the whole range of English literature, Celia’s character was, at least, equally definitely drawn in its more amiable and natural conventionalism, and in proportion to the care and space given to it, the trait of conventionalism was quite equally prominent.

Again, in the admirable sketch of Nancy Lammeter — the heroine, if there be a heroine, in Silas Marner — George Eliot has given us the same vein of character, though there in connection with it a depth of inherited traditional prepossession and a warmth of womanly disinterestedness, which make it lovable, instead of even faintly unpleasing.

. . . . . . . . . .

Romola

. . . . . . . . . .

On the other hand, in Romola, as well as in Maggie Tulliver of The Mill on the Floss, and in Dorothea Brooke of Middlemarch, she has made a study of women the current of whose nature runs against this conventionalism.

Their live are in some degree a war with it, either in the moral or the intellectual region and here, again, the depth and intensity of the purpose which was in the author’s mind are equally conspicuous.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Gwendolen HarlethIf Gwendolen Harleth (Daniel Deronda) is meant to succumb to the conventional limits imposed on selfishness by social influence, George Eliot has certainly struck a wrong note at starting. The idea of the character is indeed intellectual ambition without originality, but it is moral self-will of a sort which must end in transgressing conventional limits as the pressure of life increases.

It would be quite contrary to George Eliot’s manner to lay so much stress on this as she has done, and then merge this feature of Gwendolen’s character in conventional traits.

We do not know a case in which George Eliot has carefully drawn a feminine character without an emphasis, without a stress, without a certain concentration of manner which make it impossible to miss her purpose, or to doubt that that purpose is part and parcel of her sketch.

Witty and humorous women in minor rolesShe has, of course, made many clever sketches of witty or humorous women like Mrs. Poyser, or Mrs. Cadwallader (Middlemarch), and in her degree, too, Nancy Lammeter, already referred to.

But the lightness of touch here applies rather to their sayings than to the portraiture of their characters, and if we were asked what Mrs. Cadwallader or Mrs. Poyser (Adam Bede) would be in themselves, if the mother-wit which is the principal feature in them could be conceived as dormant for a time, we doubt if any reader, however careful, could form a very distinct impression.

So far as their liveliness or sagacity, it is a voice which somewhat conceals the real bent of the mind within. You see that in their case George Eliot was not giving us a lightly-touched character — indeed, she has little interest in women, unless she has enough interest either to sympathize with or dislike them — but rather diversifying her story by their vivacious sayings.

Rarely sketched with a light hand

We may take it almost as a general rule, that when George Eliot paints a woman’s character at all, she herself regards it with some very strongly marked feeling, and cannot, therefore, paint it with a light hand.

The sketch of Celia is, perhaps, the nearest thing to the display of a light hand in her female characters, but she cannot at all conceal her profound though kindly contempt for Celia, and she brings it out here and there so as to produce on the reader something like the effect of a dissonance.

Hence it seems to us that if Gwendolen Harleth is not going to be a very carefully elaborated study, she will be a flaw in the art of the story. There is too much purpose and point displayed already in the initial sketch of her to render it possible, with any true regard to art, to shade the character off into a new type of purely conventional selfishness.

The stress laid on her self-will and imperiousness has already gone too far to admit of these qualities being confined within the limits which social convention imposes.

George Eliot has indeed studied these limits carefully, and well knows how powerful they are. But she has as carefully prepared us in this character for a selfishness which should pass the limits of the conventional, and hurry on into flagrant evil, or even crime.

Eliot’s heroines will endure in literary history

It is quite true, we suppose, that many of the women of this great novelist will be the delights of English literature as long as the language endures.

The spiritual beauty of Dinah (Adam Bede), the childish and almost involuntary selfishness and love of ease which give a strange pathos to the tragic fate of Hetty, the vague ardor of Dorothea, the thin amiability but thorough unlovability of Rosamond.

All these, and many other feminine paintings by the same hand, will be historic pictures in our literature, if human foresight be worth anything, at least as long as Sir Walter Scott’s studies of James, and Baby Charles, and Elizabeth, and Mary Stuart, and Leicester are regarded as historic pictures in this land.

But George Eliot’s fictional women are certainly never likely to be remarkable for airiness of touch. It is not Sir Joshua Reynolds, but rather Van Dyck, or even Rembrandt, among the portrait-painters whom she resembles. She is always in earnest about her women, and makes the reader in earnest too, — you cannot pass her characters by with mere amusement, as you can many of Shakespeare’s and some of Scott’s, and not a few of Jane Austen‘s.

There is the Puritan intensity of feeling, the Miltonic weight of thought, in all George Eliot’s drawings of women. If they are superficial in character and feeling, the superficiality is insisted on as a sort of crime.

. . . . . . . . . .

Silas Marner

. . . . . . . . . .

If they are not superficial, the depth is brought out with an energy that is sometimes almost painful. We have the same kind of exaltation of tone which Milton so dearly loved in most of George Eliot’s poems; indeed, these poems have a distinctly Miltonic weight both of didactic feeling and of the rhythm which comes of it …

Thus her world of women, at all events, is a world of larger stature than the average world we know; indeed, she can hardly sketch the shadows and phantoms by which so much of the real world is peopled, without impatience and scorn. She cannot laugh at the world — of women at least — as other writers equally great can.

Where is there such a picture as Miss Austen’s of Lydia Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, or Mrs. Elton in Emma, or even Emma herself, or Miss Crawford in Mansfield Park; or even such pictures as Sir Walter Scott’s Di Vernon and Catharine Seyton?

With men, it is true, George Eliot can deal somewhat more lightly. Mr. Brooke, for instance, and Mr. Cadwallader in Middlemarch, and the admirable parish clerk, Mr. Macey, in Silas Marner, and the rector and his son in the new tale of Daniel Deronda, are touched off with comparative lightness of manner.

More neutrality in her portrayal of menOur author probably indulges more neutrality of feeling in relation to men than she does in relation to women. She does not regard them as beings whose duty it is to be very much in earnest, and who are almost contemptible or wicked if they are otherwise.

And yet she handles even men more gravely than most novelists. She has more of the stress and assiduity of Richardson than of the ease of Fielding in her drawing. Nevertheless, there are many of her male creations — Fred Vincy (Middlemarch) is an excellent example — who have really but little earnestness in them, and yet who are not so consciously weighed in the balance and found wanting as the woman in the same condition.

There is something of the large and grave statuesque style in all George Eliot’s studies of women. She cannot bear to treat them with indifference.

If they are not what she approves, she makes it painfully, emphatically evident. If they are, she dwells upon their earnestness and aspiration with an almost Puritanic moral intensity, which shows how eagerly she muses on her ideal of woman’s life.

The post George Eliot’s Fictional Women: A 19th-Century Overview appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 30, 2023

Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons (1932)

Cold Comfort Farm by British author Stella Gibbons (1902– 1989) is a comic novel that satirized the over-romanticized rural novel of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

It was said to be a send-up of what was called the “loam and lovechild” genre, poking fun at purple prose by deliberately including passages even more purple. The book was an immediate critical and popular success.

In 1933, the novel won the prestigious French literary prize, the Prix Femina, which angered fellow British author Virginia Woolf, who felt that her friend, Elizabeth Bowen, was more deserving of that year’s prize.

Christmas at Cold Comfort Farm (1940), a collection of short stories, was actually more of a prequel. Conference at Cold Comfort Farm (1949) was a proper sequel; it received reviews that were more mixed than the original novel.

Gibbons considered herself more of a serious poet than a comic writer, but it’s Cold Comfort Farm that took a foremost place in her legacy.

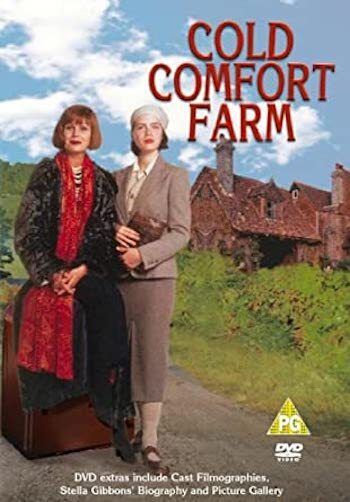

In 1995, a BBC-produced feature film of Cold Comfort Farm starring Kate Beckinsale in the lead as Flora Post was released. Many viewers and critics have lauded this adaptation for capturing the spirit of the book. Before that, there was a 1968 three-part serial made for television and in 1981, a four-part radio adaptation.

In 2019, Cold Comfort Farm was included in the BBC’s list of 100 Most Inspiring Novels.

A brief summary of Cold Comfort Farm

From the publisher of the 2012 edition (BN):

“In Gibbons’s classic tale, a resourceful young heroine finds herself in the gloomy, overwrought world of a Hardy or Brontë novel and proceeds to organize everyone out of their romantic tragedies into the pleasures of normal life.

Flora Poste, orphaned at 19, chooses to live with relatives at Cold Comfort Farm in Sussex, where cows are named Feckless, Aimless, Pointless, and Graceless, and the proprietors, the dour Starkadder family, are tyrannized by Flora’s mysterious aunt, who controls the household from a locked room.

Once there she discovers they exist in a state of chaos and feels it is up to her to bring order. Flora’s confident and clever management of an alarming cast of eccentrics is only half the pleasure of this novel.

The other half is Gibbons’s wicked sendup of romantic cliches, from the mad woman in the attic to the druidical peasants with their West Country accents and mystical herbs.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

An original 1933 review of Cold Comfort FarmFrom the original review in the Montclair Times, Montclair, NJ, June 2, 1933: Stella Gibbons gives us her first novel, Cold Comfort Farm, or a Good Woman’s Influence.

This is the sort of book you want to tell somebody about, but only a very certain somebody whose taste in humor runs in a parallel vein with your own.

To recommend it publicly in a newspaper column seems almost unkind to the book, for many people certainly will find nothing funny about it. But we shall just disregard such persons, which all they deserve, and go on and recommend the book anyway.

The passionate novel of the soil, whose characters are always very one-purposed and usually perverted in some way or other, has been with us just long enough to be parodied, and just the right person has arisen from nowhere (or perhaps the lady would rather have it said that she from a newspaper once in London) to parody it. The result is all that might be asked for. And then some more.

The ridiculous touches which Miss Gibbons administers with a light and knowing hand are scattered extravagantly throughout the book.

She has a habit of marking with two and sometimes three asterisks (as in Baedecker) the passages which she herself considers especially fine. She says in the preface that she’s always a little in doubt as to whether a sentence is literature or just sheer flapdoodle, so she evolved this plan to aid her readers.

The Starkadders, reigned over by a mad grandmother Who never leaves her room, live in a triangular house on an octagonal farm on a stark, bare cliff.

There is Judith, the mother, who spends a great deal of time “telling her cards.” Seth, her son; the male; the father, who preaches the horrors of hell-fire to the villagers, and Reuben, Seth’s brother, who waits impatiently for Amos to die so that he may run the farm, which is his only passion.

Other examples of type characters too numerous to enumerate include Meriam, the servant girl, who is frequently having babies in the cowshed; Mark and Urk and Caraway, who persist in pushing each other down wells, and Adam. love is for the four cows, Aimless, Graceless, Pointless, and Feckless.

Into this charming family circle comes Flora Poste, the cousin from London, whose knowledge of life comes from current literature. She has a great yearning for tidiness in all things and sets to work toted up the lives at Cold Comfort Farm.

So she leaves her friend Mrs. Smiling, whose chief interest in life is her unequaled collection of brassiere, which she seeks frantically and collects assiduously, and goes to Sussex to stay on the decaying farm. We leave it to the reader to find out what she, and the rest of the cast of characters, does from there.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The 1995 film adaptation

. . . . . . . . . . .

“The education bestowed on Flora Poste by her parents had been expensive, athletic and prolonged; and when they died within a few weeks of one another during the annual epidemic of the influenza or Spanish Plague which occurred in her twentieth year, she was discovered to possess every art and grace save that of earning her own living.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Flora inherited, however, from her father a strong will and from her mother a slender ankle.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“She liked Victorian novels. They were the only kind of novel you could read while eating an apple.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“On the whole, I dislike my fellow beings; I find them so difficult to understand. But I have a tidy mind and untidy lives irritate me. Also, they are uncivilized.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Like all really strong-minded women, on whom everybody flops, she adored being bossed about. It was so restful.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“One of the disadvantages of almost universal education was the fact that all kinds of persons acquired a familiarity with one’s favorite writers. It gave one a curious feeling; it was like seeing a drunken stranger wrapped in one’s dressing gown.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Well, when I am fifty-three or so I would like to write a novel as good as Persuasion but with a modern setting, of course. For the next thirty years or so I shall be collecting material for it. If anyone asks me what I work at, I shall say, ‘Collecting material’. No one can object to that.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“There are some things (like first love and one’s first reviews) at which a woman in her middle years does not care to look too closely.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

“Curious how Love destroys every vestige of that politeness which the human race, in its years of evolution, has so painfully acquired.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Cold Comfort Farm Reader discussion on Goodreads Expert (Chapter One) FictionFan’s Book Reviews The Modern Novel (review) Beyond Cold Comfort Farm — Stella Gibbons’ Other WorksThe post Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons (1932) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

March 21, 2023

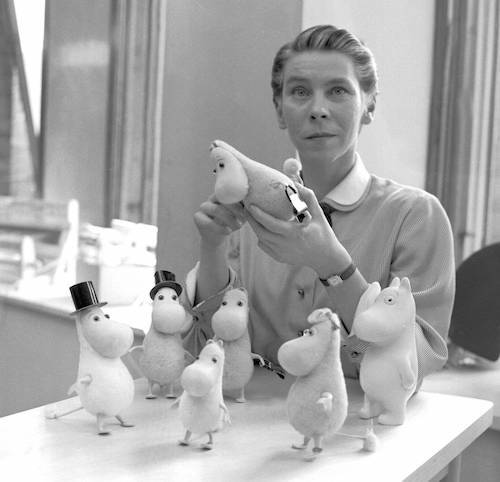

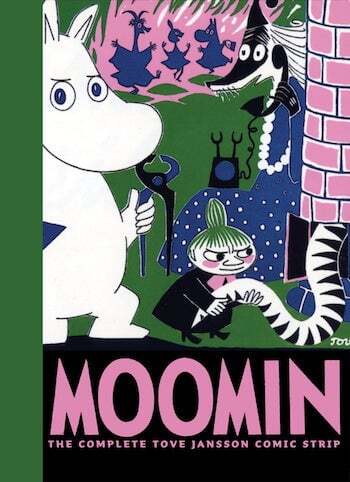

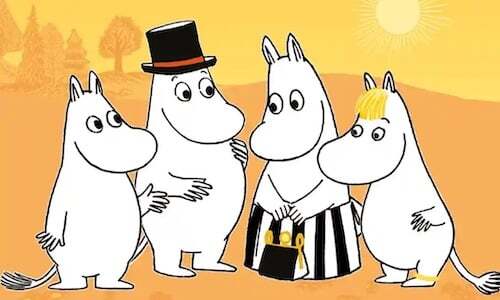

A Strange Journey: Tove Jansson and The Moomins

The Moomins (Mumintroll in Swedish) were the most famous creation of Finnish-Swedish author and artist Tove Jannson. Though this beloved creator wrote and illustrated many other works for both children and adults, the names of Tove Jansson and The Moomins will be forever linked.

The family of round, white fairytale creatures — which resemble hippopotamuses — first appeared in 1946, and were the central characters in a total of nine novels, four picture books, and a comic strip that ran for more than twenty years.

Although Tove was a prolific illustrator, painter, and writer for adults, the Moomins are her enduring legacy, beloved across Finland and the world, and still hugely popular today.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Tove Jansson

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Moomins had their origins in the grey, dreary days of World War II, when Tove was struggling to paint, longing for an escape, and was “feeling depressed and scared of the bombing and wanted to get away from my gloomy thoughts to something else entirely …”

She turned to writing and drawing, and what emerged during the Winter War of 1939 – 1940 was the first story of Moomintroll, Moominmamma, and Moominpappa — a story of adventure, loss, and longing for safety.

Moomintroll and his mother are looking for a home for the winter, as well as for Moominpappa, who has disappeared. Along the way they find a friend, the animal “sniff,” and a new little family is formed.

The theme of displacement, the anxiety and danger inherent in the story, and the hope of change for the better all came out of Tove’s experiences of war, but her inclinations still lay towards happiness, towards a brighter future. She referred to this in her letters to her friend Eva Konikoff:

“For a whole year, Eva, I’ve not been able to paint. The war finally destroyed my pleasure in my painting … It took time to realize that what matters is a path, not a goal. Now I want my painting to be something that springs naturally from myself, preferably from my happiness. And I am determined to be happy…”

In the new world that she created, Moomintroll’s journey ends in such a place of happiness: a beautiful valley laden with fruit and flowers and sunshine, which Tove named Moominvalley. The book was a creation story of sorts, explaining the habits of Moomintrolls (such as hibernating from November to April).

It also establishes Moominpappa as an “unusual Moomintroll” because of his restlessness and longing for adventure, and Moominmamma as a central character of strength who holds the family together.

The original title of this first Moomin story was Moomintroll’s Strange Journey, but it is not mentioned in letters or notes until 1944, when Tove’s brother Per Olav was home on leave from the eastern front.

Tove then wrote in her diary, “I felt I wanted to write a fair copy of Moomintroll’s Strange Journey and change it.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

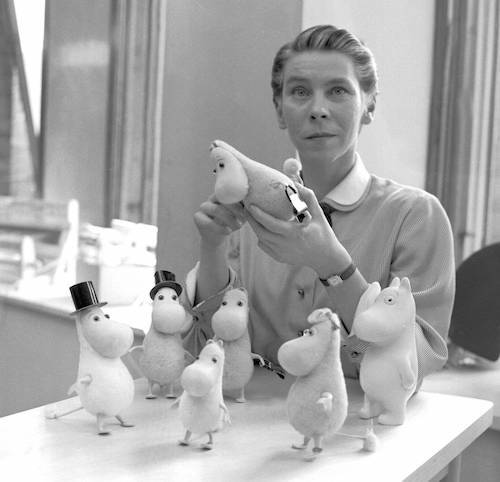

Tove Jansson with 3-dimensional Moomins in 1956

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . . .

In a fit of joyous enthusiasm, she finished the new version in a few days and handed it in at Söderströms Publishers in May 1944. She celebrated by buying a new hat for spring, blue and flowery, “my first really feminine and idiotic one.”

However, it was a year later, in June 1945, that she noted in her diary, “Received the proofs of The Moomins and the Great Flood [the new working title for Moomintroll’s Strange Journey] and made a sort of start on the next Moomin book.”

The book, ultimately published under the title The Little Trolls and the Great Flood, rather than went largely unnoticed. There was just one review, by Gudrun Mörne in Arbetarbladet in January 1946, which was largely positive, but the book sold just 246 copies in that year.

The name Moomintroll itself came from her Swedish maternal uncle, Einar. In an interview in 1947, Tove explained:

“… When I was a small child I used to steal food from the larder. And then my uncle said, ‘Watch out for the cold Moomintrolls. They rush out of their hideyholes the moment a larder thief shows herself and begin to rub their snouts against her legs and then she begins to freeze so that everyone can see that there goes someone who’s been stealing jam and liver pâté.’”

A new passion

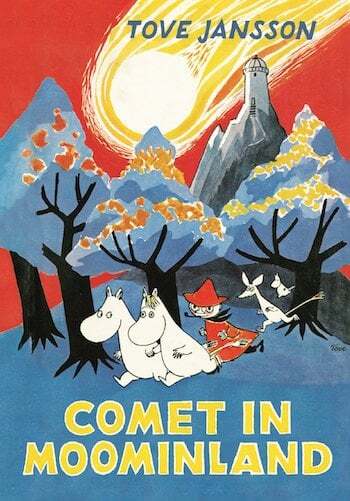

Tove herself became enthralled with the Moomins, and often had to force herself to stop working on them in order to do other things. The second book, Comet in Moominland, was written in the summer of 1945 and accepted for publication in spring of 1946.

This was quickly followed by The Hobgoblin’s Hat, which she wrote in summer 1946. These first three Moomin books established Tove’s reputation as a “double artist,” one who worked with both images and words.

She took a lot of inspiration for the natural world of Moominvalley (and the other landscapes of the Moomin books) from her summers spent on the Pellinge archipelago.

From the time she was born, Tove had spent weeks each year at the family’s various summer houses, where wild weather and the power of the sea were forces that couldn’t be escaped. Her father had a passion for the wildness of the archipelago and its seascapes, and this passion would later be shared by Moominpappa.

Storms and bad weather also feature heavily in the various catastrophes and disasters that the Moomin family face throughout the books, and some of the descriptions of the natural world that surrounds the Moomins read like prescient warnings of climate change:

“… the great gap that had been the sea in front of them, the dark red sky overhead, and behind, the forest panting in the heat.”

Söderströms also published Comet in Moominland, with a glowing blurb on the back cover which spoke of Tove as a “talented and imaginative woman who knows just what children like to hear.”

Commercially, it was no more of a success than the first book, but Finland-Swedish reviews were generally positive. Already, the Moomin books were talked about as books that held appeal for both children and adults, and were compared to Winnie-the-Pooh.

First Moomin success: The Hobgoblin’s Hat

The Hobgoblin’s Hat, the third book in the Moomin series, was published by Schildts and was the first commercial success. While writing it, Tove fell violently in love with Vivica Bandler, a theatre director, and this new Moomin story left behind the anxiety and tension of the first two war-time books.

Instead, Tove explored love, friendship, and the affinity between two creatures — Thingumy and Bob, also the pet names that she and Vivica had for each other — who wander into Moominvalley one summer’s day bearing a mysterious suitcase. In 1947, Tove wrote to Vivica:

“The Moomin book’s finished. Thingumy and Bob had now run riot at the end and definitely overcome the Groke [the name Tove and Vivica gave to the “enemy of love,” the laws and social conventions that outlawed homosexuality]. They are inseparable and sleep together in a desk drawer. No one understands their language, but that doesn’t matter so long as they themselves know what it’s all about…”

Tove also continued to be inspired by her love for the islands of the archipelago on which she spent so many summers; by the landscape and the seas and the wild weather. The Hobgoblin’s Hat features storms that turn the sky yellow, thunder and lightning and rain, and crashing waves that keep the character Snufkin awake.

At the same time Tove also made far more use of color in her illustrations: in contrast to the gloomy Indian ink that she used to illustrate the first two books, the Moomin summer of The Hobgoblin’s Hat is as “gaudy as an engagement bouquet.”

The book was published in 1948 and received several good reviews. In a survey of children’s books for Christmas 1948, Solveig von Schoultz devoted a large amount of space to The Hobgoblin’s Hat, writing that, “Pictures and text belong organically together and have the same qualities; one can’t talk about illustrations in the normal sense, but rather of an artist with two native languages.”

It was also the first Moomin book to be translated into English: in spring of 1950, The Hobgoblin’s Hat was published in the UK as Finn Family Moomintroll.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Hell’s growl-jumps: a theatrical triumphOn 29th December 1949, the first Moomin theatre play was performed. Moomintroll and the Comet drew on Comet in Moominland, The Hobgoblin’s Hat, and also the fourth book in the series, The Exploits of Moominpappa (a kind of biography of Moominpappa’s early life, which was a great success with the critics).

It was directed by Vivica Bandler, and Tove worked on the script as well as the costumes and scenery. She was determined to experience every aspect of working in the theatre, and after the dress rehearsal wrote to Eva: “It was so appallingly awful that there must be a good chance the first night will go well. Snufkin overslept after a party and didn’t turn up at all…”

Her prediction was right. The opening performance received generally good reviews although some parents complained of the play’s “strong language.”

Expressions such as “begrowled” and “hell’s growl-jumps” had largely passed over the children’s heads, but caused consternation among the adults. One father wrote, “…in its present form, with its boozing prophets and strong expletives, I cannot recommend it.”

This theatrical experience would later be turned into the book Moominsummer Madness, published in 1954, in which the dress rehearsal of Moominpappa’s tragic play is full of errors and poor performances.

“Moomin duties” and international fame

Even before The Exploits of Moominpappa, the Moomins had begun to expand beyond the books. Various “Moomin duties” were beginning to take up Tove’s time. She wrote to Eva in the spring of 1950:

“These Moomin duties seem to be swamping me….there are constant interviews and arrangements to do with the books … Moomin ceramics and Moomin slides you look at through special viewers and whatnot. And then the Moomin opposition, help! — all those aggressive people who scold me about the poor troll …”

Moomin illustrations were appearing outside of the books. Two short Moomin stories appeared in newspapers, while Tove was invited to exhibit Moomin illustrations in Norway.

The Moomins even advanced into academic circles: there were invitations from Helsinki University, the Helsinki School of Economics, and the universities of Lund, Oslo, and Gothenburg to discuss “the new children’s literature.”

The Moomins, it seemed, were everywhere, but Tove remained protective of her creation and famously turned down the advances of the Walt Disney company to make Moomin cartoons.

The Book About Moomin, Mymble and Little My was the first full Moomin picture book. It used cut-out methods and startling combinations of colors to great effect. It won Tove her first award, the Nils Holgersson Plaque awarded by the General Association of Swedish Libraries.

This was followed, after Moominland Midwinter in 1957, by the Elsa Beskow Plaque, the Rudolf Koivu Prize, and the Swedish Literature Association’s Prize.

The Moomins traveled even further with the introduction of a comic strip in the London Evening News. After several months of back and forth over contracts, the first strip was published in September 1954, and within two years was running in twenty countries.

It was both exciting and draining for Tove. Having regular income was a huge improvement to her previous ever-desperate finances, but the amount of work involved was overwhelming.

“This is no bit of fun on the side,” she wrote. Each week she would send off six “daily episodes” to London, for a strip that overall would last three months. Her contract was for seven years.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

The end of a love affairAfter several years, the pleasure and excitement of the comic strips, and the opportunities they gave Tove to develop the characters, were far outweighed by the stress of constantly having to find new ideas.

She noted sarcastically, “It’s going so well I can’t help getting rich even if they keep cheating me.” But she often spoke of how creating the strips had become constraining, turning the pleasure of creating art into the stress of a deadline and the encumbrance of duty.

She had financial freedom, but the associated contracts, correspondence, appearances, and interviews drained her time and energy and left her with little desire to work. She began to feel ambivalent towards the Moomins, and increasingly frustrated and angry with what felt like a living creature beyond her control that also prevented her from painting.

As early as 1955, she was complaining: “I can’t recall exactly when I became hostile to my work, or how it happened and what I should do to recapture my natural pleasure in it …” She felt hidden behind the Moomins and her identity as “troll-mother.”

By 1957 Tove was in negotiations over contracts and rights to see if she could end the arrangement early. Eventually, it was agreed that Tove would continue for two more years, up to the end date of the original contract. However, the newspapers were keen to continue the strips beyond that time, and it was agreed that a successor would have to be found.

For Tove, this was no problem: she had already collaborated with her brother Lars (also a writer and artist) on several other books, and he was the natural choice. In 1960, Lars officially took over the Moomin strip series, along with the financial side of the “Moomin business.” The strip ran under his direction until 1975.

A company was also founded, Moomin Characters, to look after rights and production of merchandise (which by this time included wallpaper, cards, puzzles, crockery, ties, mugs, bookmarks, calendars, dolls, and braces and suspenders).

. . . . . . . . . . .

Moomin Shop in Itis Mall, Helskinki

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . . .

After leaving behind the Moomin strips, she made as much of a clean break as she could. In letters to friends, she was almost brutally dismissive of the characters and the world she had created, saying that she had “forced her brain to work with trivial ideas which made real ideas disappear,” and that working on the comic strips had been like a “threadbare marriage.”

Almost with relief, she noted her belief that the demand for the Moomins was at last abating: “It won’t be long before no one will ever again want trolls made of marzipan or soap, or wear them pinned to their bosoms.”

In January 1961 she wrote that she would never again “be able to write about those happy idiots who forgive one another and never realize they’re being fooled.”

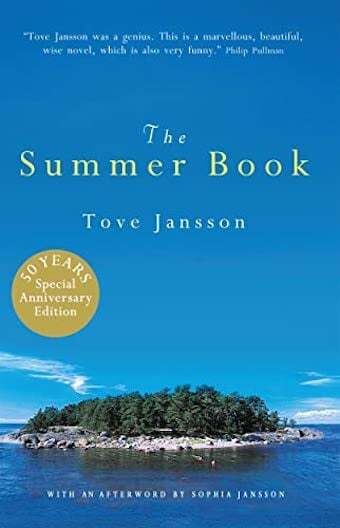

However, separating herself from the desire to tell stories was not so easy. She spoke of Tales from Moominvalley as her last Moomin book, published in 1962, but two more would follow: Moominpappa at Sea (1965) and Moominvalley in November (1970), in which the family has left Moominvalley. This final book had no Moomins in it at all.

Legacy of The Moomins

Tove would never be entirely free of the Moomins. Her belief that all the hype over the Moomins was waning was perhaps wishful thinking, and over the following decades there would be more plays, television adaptations, and hundreds of different items of merchandise.

Although Tove developed an equally strong reputation as an author of books for adults, any interviews that she granted would inevitably come around to the Moomins, and considerable correspondence — to which she diligently replied right up until her death in 2001 — was also largely from Moomin fans.

The Moomin books have been translated into some fifty languages. New stories continue to be written using original drawings and materials from Tove’s vast archive, control of which is managed by her niece Sophia.

There have been three feature films: Moomin and Midsummer Madness (2008), Moomins and the Comet Chase (2010), and Moomins on the Riviera (2014).

In addition, there is a Moomin theme park — Moomin World in Naantali, Finland — and a comprehensive, interactive Moomin website, where readers can explore Moominvalley, delve into the history of the books, find out all about the characters, and take the quiz to see which Moomin character they are (this reader is a proud Moominmamma).

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

Further reading and sourcesThe Moomins (available separately and in various collected editions)Tove Jansson: Life, Art, Words by Boel Westin (Sort of Books, 2018)Tove Jansson: Work and Love by Dr Tuula Karjalainen (Penguin, 2016)Letters from Tove, edited by Boel Westin and Helen Svensson (Sort Of Books, 2020) Moomins websiteTove Jansson website

The post A Strange Journey: Tove Jansson and The Moomins appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

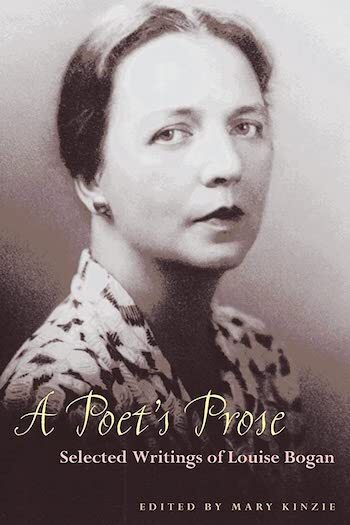

March 13, 2023

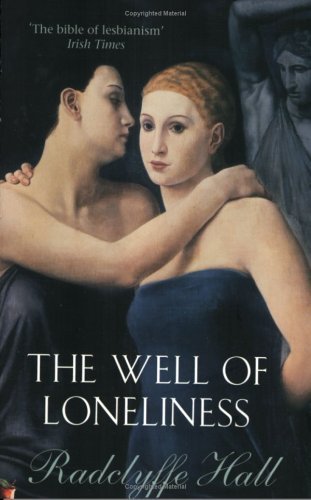

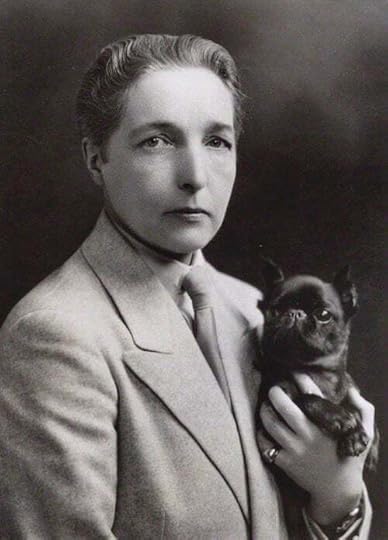

The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (1928)

Since its first appearance in 1928, The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (1880 – 1943) has spurred much discussion and controversy. The semi-autobiographical novel about a young woman’s coming to terms with her lesbian identity caused a furor when first published in England.

Once denounced as immoral, it has also been praised as a courageous work of literature. It shocked some members “proper” society and served as an awakening to others who felt isolated by repressive social mores.

The Well of Loneliness is a semiautobiographical story of Radclyffe Hall’s own life. Shockingly candid for its time, this novel was the very first to condemn homophobic society.

A book ahead of its timeAt the time it was published, the story of same-sex love between women was a topic that was rarely written about outside of scientific textbooks.

Banned outright in 1928 when first published in Britain, the novel went to trial for obscenity. Its publication marked an act of great courage by the publisher, which almost ruined Hall’s literary career. Although many decades have passed since its initial publication, the issued of prejudice and persecution that Radclyffe Hall addresses remain relevant today.

Receiving pushback from critics for her “sexually deviant” novel, Hall was swept into legal battles. Despite its early banning, the novel’s notoriety helped push narratives of lesbians in Western literature to the forefront. Hall made it clear to her publisher that she wanted the original text published, declaring:

“I have put my pen at the service of some of the most persecuted and misunderstood people in the world … So far as I know nothing of the kind has ever been attempted before in fiction.”

Surprisingly, The Well of Loneliness received more liberal treatment in American courts than it did in England. Justices dismissed charges of violation of Section 1141 of the Penal Law against Covici-Freide, Inc., American publishers of the book. The Court said:

“The book in question deals with a delicate social problem, which in itself cannot be said to be in violation of the law unless it is written in such a manner as to make it obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, or indecent, and tends to deprave and corrupt minds open to immoral influences.”

After Hall’s death in 1943, the ban on The Well of Loneliness was eventually overturned on appeal. Although she was vindicated by the American verdict, she steered clear of equal controversy in her subsequent literary works.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Radclyffe Hall

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

Hall described herself as a “congenital invert,” referring to an innate characteristic. The term comes from early 20th-century sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing and refers to a type of inborn gender reversal where women could be born with a masculine soul and vice versa.

Though at the time the term referred more to homosexuality, the concept seems more akin to what today is referred to as transgender or nonbinary.

Brief synopses of The Well of LonelinessWhat has remained Radclyffe Hall’s most famous work, The Well of Loneliness (1928), features a lesbian from an upper class family in England. Though born a daughter, her father bestows upon her the masculine name of Stephen.

The father is the epitome of kindness and understanding; Stephen’s mother Anna is more of the delicate society type, but though she doesn’t have the same understanding of her unusual daughter, is never unkind or uncaring.

After going through two intense, failed relationships, Stephen winds up with her partner, Mary Llewellyn. Their journey through a lesbian relationship during an era that rejected this expression of sexuality poses the setting and plot of the novel.

According to an introduction to an earlier edition of the book:

“The Well of Loneliness presents the life story of Stephen Gordon, the only child of Sir Philip and Lady Anna Gordon, who ardently desired a son in her place.

How this circumstance influenced a natural tendency towards masculinity in Stephen, her tortured adolescence, and her gradual development into maturity in this direction, with all its tragic implications, is the theme that is explored. Radclyffe Hall has treated this subject with delicacy and deep psychological insight, combined with frankness and sincerity.”

And more from a later edition of The Well of Loneliness (1990, Anchor Books/Doubleday):

“Originally published in 1928, Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness is the timeless story of a lesbian couple’s struggle to be accepted by ‘polite’ society. When an unconventional woman named Stephen Gordon falls in love with an ingenue named Mary, their love affair gives Stephen her first taste of happiness.

However, the pleasure the lovers find in each other is quickly tarnished by the disapproval of friends and family who refuse to welcome the scandalous couple into their homes. But the most difficult test of the women’s love for each other comes when a young man offers to give Mary the respectability that Stephen can not.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes by Radclyffe Hall, author of The Well of Loneliness.

. . . . . . . . .

Though considered bold and provocative for its time, many mainstream newspapers recoiled at the banning and censorship of this landmark book. Certainly, this echoes today’s emboldened attempts (often, alas, successful) to ban books with queer subject matter in libraries and schools.

Here is one of a number of such commentaries, expressing alarm over the censorship of The Well of Loneliness:

From the Daily Herald (London), August 24, 1928:

The question of literary censorship is brought to the forefront by the announcement that Miss Radclyffe Hall’s novel, The Well of Loneliness, has been withdrawn from publication at the request of the Home Secretary.

As the publishers had sent the book to Sir William Joynson-Hicks for judgment, they cannot very well ignore his request, but all who have at heart the interests of literature will be anxious that further light should be should be thrown on the subject.

The question is one which cannot be considered only as affecting the sale of a particular book. What the public is entitled to know is, on what grounds and by whose judgment are books banned or not banned? If the control of English literature is to be left to Sir Joynson-Hicks, authors and readers may well demand to know what qualifications he possessess as a judge of literature.

This is not by any means the first occasion on which a book or play dealing seriously with a grave social issue has been suppressed, while books and plays which are deliberately provocative in their sensual appeal pass unchallenged.

This question of censorship is one which calls for very grave consideration, and we hope that a full explanation will be forthcoming from the Home Office.

. . . . . . . . . .