Nava Atlas's Blog, page 24

August 7, 2022

Eulalie Spence, Playwright of the Harlem Renaissance Era

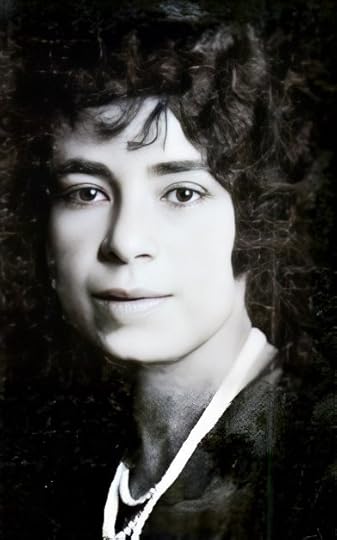

Eulalie Spence (June 11, 1894 – March 7, 1981) was an award-winning American playwright, stage director, actress, and educator. As a prolific Black writer in the first half of the twentieth century, Spence was most active during the Harlem Renaissance era.

She was so esteemed and prolific in her heyday that her relative obscurity today is unfathomable. Like many of her contemporaries who blossomed during the Harlem Renaissance years, she was multitalented — a writer and playwright, as well as an actress and teacher. She authored some fourteen plays, five of which were preserved in print; nearly all were staged.

An immigrant from the British West Indies, Spence went against the prevailing trend of her time among Black creatives, which was to use the arts in all forms to press for racial justice. She believed that plays were for entertainment and considered herself a “folk dramatist.”

She was a member of W.E.B. Du Bois’s Krigwa players from 1926 to 1928, and though she clashed with the eminent Du Bois about the purpose of theatre, she was a highly visible member of the Black arts community of the Harlem Renaissance, and one of its most popular.

Later, Spence became a mentor to one of her high school students who would later become a renowned theatrical producer. That was none other than Joseph Papp, founder of The Public Theater and Shakespeare in the Park theatre festival. Spence was the only Black teacher in his predominantly white high school, and he described her as “the most influential force” in his life.

As a playwright, Spence was most active from 1923 to 1929; her last and most controversial play, The Whipping, came out in 1934.

Early years—from the British West Indies to Brooklyn

Eulalie Spence was born in Nevis, British West Indies, to Robert and Eno Lake Spence. Her early childhood was spent on her father’s sugar cane plantation. When it was destroyed by a hurricane in 1902, the family moved to New York City. They briefly lived in Harlem before settling in Brooklyn.

Eulalie’s upbringing in a family of seven girls wasn’t easy under the family’s circumstances. Still, she maintained a gentle, loving spirit that helped keep the large family close-knit. Robert struggled to keep steady work, always dreaming of returning to his homeland. The family endured a hardscrabble life in a tiny Brooklyn apartment.

Despite the impoverished circumstances of her childhood in Brooklyn, Spence managed to draw positive inspiration from her parents. Her mother would often read to her, which strengthened their bond. She admired her mother’s strong and independent demeanor. These attributes would later inspire the female characters in her plays.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Eulalie Spence in the 1920s

. . . . . . . . . . .

Eulalie forged a path through school to get a good education. She graduated from the Wadleigh High School for Girls, which became the first all-girls’ public high school in New York City.

After Wadleigh, Eulalie attended and graduated from the New York Training School for Teachers. In 1924, she enrolled at National Ethiopian Art Theatre School, whose primary aim was to empower Black actors through training and employment.

Much later, she continued her education, culminating – with a Master of Arts in Speech from Teacher’s College, Columbia University in 1937.

She taught at the Eastern District High School in Brooklyn for more than thirty years, from 1927 to 1958, overlapping with her theatrical endeavors (she didn’t make a living from the latter). The only Black teacher in a predominantly white school, she taught dramatics, English, and elocution. As mentioned earlier, one of her students was Joseph Papp, who was greatly inspired by her.

. . . . . . . . . . .

RELATED CONTENT

Renaissance Women: 13 Female Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read7 Black Women Playwrights of the Early 20th Century

. . . . . . . . . .

Though she authored some fourteen plays, Spence’s creative journey wasn’t an easy one. Her star as a playwright shone brightest in the 1920s, in the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance era.

Most of Spence’s plays were performed by a theatre company known as Krigwa (Crisis Guild of Writers and Artists). She first affiliated with them when she won second place in the group’s 1926 playwriting competition. Her one-act play was titled Foreign Mail.

Krigwa (formerly known as Crigwa), was founded in 1925 by William Edward Burghardt (W.E.B.) Du Bois. It started with the mission of sponsoring an annual playwriting competition, and later transitioned into a theatre company for staging plays.

The primary aim of the Harlem-based theatre group was to create, nurture, develop, and promote budding writers, performers, actors, and directors housed in the black community.

That same year, a second play titled Her saw her win yet another second-place award in a literary contest hosted by Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life. Her received countless accolades for its skillful writing.

Her ushered in the second season of the Krigwa Players which had Spence’s two sisters, Olga and Doralene, take part in the productions. Later in 1927, another of Spence’s plays, The Hunch, came in second in yet another round of the Opportunity contests; Undertow tied for third place in a 1927 contest sponsored by The Crisis, the journal of the NAACP.

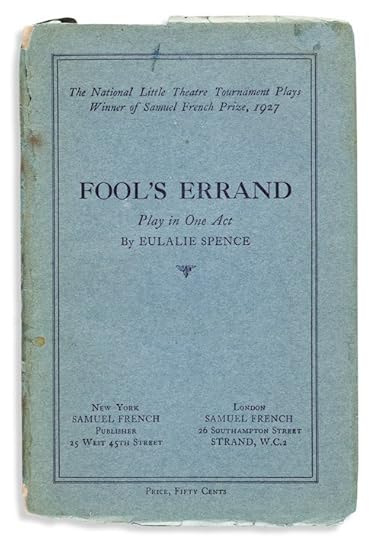

Fool’s Errand (1927) was a finalist in the International Little Tournament on behalf of the Krigwa Players; it was subsequently published by Samuel French.

In addition to these award-winning works, Spence wrote several other plays. On Being Forty is one of her best-known plays; it was staged on several occasions, including a production by the Bank Street Players and the National Ethiopian Art Theatre.

Spence had the privilege of directing two plays around this period for the Dunbar Garden Players. These were Joint Owners in Spain by Alice Brown and Before Breakfast by Eugene O’Neill.

Spence preferred to write comedies and drama and would avoid racial propaganda as much as possible. Her plays would often focus on the day-to-day domestic lives of African-Americans especially touching on typical love triangles where male characters tended to be weaker than female characters.

While her characters were typically Black, she preferred to steer clear of racial themes. What’s more, she made use of Black dialect, which often subjected her to criticism by some of her contemporaries in the Black arts community.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A major career falloutWhile Eulalie Spence was doing well as a playwright under the umbrella of Krigwa Players, she eventually experienced a career setback. Though she helped expand the visibility of this theatre group, Spence never saw eye to eye with W.E.B. Du Bois.

Du Bois insisted that theatre and other arts were for the purpose of positive propaganda, to elevate the stature of Black people. Spence felt that theatre was better leveraged as a vehicle for entertainment. She emphasized her stance in a widely read essay for Opportunity magazine. In it, she wrote: “We go to the theatre for entertainment, not to have old fires and hates rekindled.”

Since she refused to write the kind of dramas Du Bois thought she should, they came to a major fallout. In the 1927 Little Theatre Tournament, Du Bois decided to keep all the prize money to himself at the expense of paying Spence and other actors. This resulted in the disbandment of the Krigwa Players.

The Whipping — a controversial final play

In 1934, Eulalie Spence adapted The Whipping, a novel by Ron Flanagan. It would be her last play as well as her only three-act play, marking a significant milestone in her writing career.

The Whipping features a sensational plot that goes beyond the Black/white racial divide in a rather spectacular articulation. Spence went past the norm of that era and instead of writing about the lives of black people which most Black female writers in the Harlem Renaissance were accustomed to, she wrote about the theatrics of a white woman. It involved this character subverting the Klan.

Further fueling controversy around The Whipping, it was not only adapted from a story by a white author about a white character, Spence hired a white agent to represent her, further breaking the prevalent racial barriers at the time.

Nonetheless, despite a buildup to a striking performance, Spence suffered another setback. Her scheduled production was abruptly canceled without notice or explanation just a few days before it was to open.

As a result, a devastated Spence was forced to option her screenplay to Paramount Pictures. She did receive five thousand dollars, a significant sum at the height of the Depression, but it was never adapted to film, nor staged. And it was the only money she ever earned for her writing. Despite these setbacks, The Whipping remains a significant milestone in Spence’s writing career.

After all the drama surrounding The Whipping, Spence withdrew from the public limelight and focused her attention on teaching at Eastern District High School. She continued to write and act for Columbia University’s Laboratory Players.

The Legacy of Eulalie Spence

Spence remains one of the most influential and prolific African-American female writers of the Harlem Reconnaissance era. In the eleven years of her most active writing phase, she successfully authored enduring masterpieces, from The Starter (1923) to The Whipping (1934).

In addition to her plays, Spence wrote noteworthy essays for Opportunity including “Negro Art Players in Harlem” and “A Criticism of the Negro Drama as it Relates to the Negro Dramatist and Artist” (both published in 1928).

Spence’s plays showed sensitivity to race and gender, drawing their emotional tenor from her family’s experiences as immigrants. She stood firm in writing what she called “folk plays,” which emphasized the daily lives of Black people, resisting Du Bois’s call for “race plays.” Her plays showcased strong female characters and sometimes featured love triangles.

Spence died at the age of eighty-six in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. At the time of her death, she had been living with her niece, Patricia Hart. Her obituary described her only as a retired schoolteacher, neglecting to mention her career as a significant playwright.

More about Eulalie SpenceMajor Works (plays)

The Starter (1923)On Being Forty (1924)Foreign Mail (1926)Fool’s Errand (1927)Her (1927)Hot Stuff (1927)The Hunch (1927)Undertow (1927)Episode (1928)La Divina Pastora (1929)The Whipping (1934)More information and sources

Wikipedia Eulalie Spence Papers — New York Public Library Lost Voices in Black History Talking B(l)ack: Construction of Gender and Race in the Plays of Eulalie SpenceThe post Eulalie Spence, Playwright of the Harlem Renaissance Era appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 1, 2022

China Court by Rumer Godden (1961)

At first glimpse, China Court by Rumer Godden, the prolific British author, seems fairly straightforward. But this 1961 novel is a book of subtlety and many layers. The grand house that is called China Court is almost a character in itself, developing alongside its human inhabitants.

Though not as widely read as she was during her lifetime, Rumer Godden’s books still resonate with contemporary readers. Though there are some mixed reviews, overall, China Court ranks highly in this reader discussion on Goodreads.

Originally subtitled The Hours of a Country House, here it’s described by the publisher of the 2021 edition (Open Road Media):

“A New York Times-bestselling novel of the lives, loves, and foibles of five generations of a British family occupying a manor house in Wales.

For nearly one hundred and fifty years the Quin family has lived at China Court, their magnificent estate in the Welsh countryside. The land, gardens, and breathtaking home have been maintained, cherished, and ultimately passed along–from Eustace and Adza in the early nineteenth century to village-girl-turned-lady-of-the-manor Ripsie Quin, her children, and her granddaughter, Tracy, in the twentieth.

Brilliantly intermingling the past and the present, China Court is a sweeping family saga that weaves back and forth through time. The story begins at the end, in 1960, with the death of the indomitable Ripsie, whose dream of a life at the grand estate was realized through her marriage to the steadfast Quin brother who loved her–though he wasn’t the one she had always loved.

With thrilling literary leaps across the decades, the story of a British dynasty is told in enthralling detail. It is a chronicle of wives and husbands; of mothers, sons, and daughters; of those who could never stray far from the lush grounds of China Court and the outcasts and outsiders who would never truly belong.

Bearing comparison to One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, Rumer Godden’s novel relates the history of a family with sensitivity, wit, compassion, and a compelling touch of magical realism.

A family’s loves, pains, triumphs, and scandals are laid bare, forming an intricate tapestry of heart-wrenching humanity, in a remarkable work of fiction from one of the most acclaimed British novelists of the twentieth century.”

A 1961 review of China Court by Rumer Godden

From the original review of China Court in the Daily News Leader (Staunton, Virginia), February 26, 1961:

Whether she is writing of India, where she spent her childhood — as in The River, Black Narcissus, and Kingfishers Catch Fire; or of her native England, as in A Candle for St. Jude, An Episode of Sparrows; or of France, as in The Greengage Summer, Rumer Godden writes not only with great skill but with a strong feeling for place and an obvious affection for people.

China Court is a lovely old Cornish manor house: “It must have looked very plain, quite uncompromising, when it was first built. It is a granite house; naturally, granite is the local stone.”

As Miss Godden tells its story, this great house, built and lived in with such pride in the 19th century, has become an anachronism — inefficient, uneconomical, wholly impractical. Only old Mrs. Quin and her 21-year-old granddaughter, Tracy, love. To them it’s more than a house, it’s their home.

Other members of the family — Mrs. Quin’s daughters and their husbands, Tracy’s aunts and uncles — believe emphatically that the place should be disposed of: “It’s ridiculous, Mother, you living alone in that great house … It has no amenities … If you sold it, even as it is now, you could have a much bigger income and comfortable little flat. You would be far more free.”

To all such arguments, Mrs. Quin replies firmly, “I don’t wish to be free. Even in this generation a few people do not wish to be free of their house.”

In her beautifully worked-out story, one ranging back and forth across five generations, Miss Godden tells of China Court and of the people who have filled it with warmth and life. In the end it is the eccentricity of one generation which comes to the rescue of another, and which makes it possible to save the house for future descendants of the Quins.

. . . . . . . . . .

China Court on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post China Court by Rumer Godden (1961) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 29, 2022

10 Classic Women Authors and Their Cats

In this site’s overview of classic women authors and their dogs and cats, it seems like dogs have the clear edge as writers’ preferred furry friends. But digging deeper, I’m no longer so sure of that! As it turns out, women authors and their cats are just as companionable, which this roundup will amply demonstrate.

I got to thinking about this when I heard that my friend and colleague Bob Eckstein had produced The Complete Book of Cat Names (That Your Cat Won’t Answer to, Anyway). Bob is a New Yorker cartoonist and a wonderful watercolorist. You may also enjoy this excerpt from his book, Footnotes from the World’s Greatest Bookstores.

On the subject of naming cats, Bob observes:

Online studies from respected cat blogs have shown that 80% of cat owners regret the name they gave their kitten. Number one reason? “It became too popular.” (Number two reason given was “Too stupid to say in front of company.”)

It’s hard to say how much thought our classic women authors gave to naming their cats, or whether they would have gone with some of Bob’s often hilarious suggestions (Catsy Cline, Mick Jaguar, Purradise Lost). I was unable to find out what most of the following authors named their cats, but here’s hoping they came up with something more creative than “boots” and “fluffy.”

. . . . . . . . .

The Complete Book of Cat Names by Bob Eckstein

is available on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . . .

French author Colette, best known for Gigi and the Claudine stories, was a noted cat lover. Her 1936 novella, La Chatte, is about a love triangle of sorts — between a woman, her husband, and the cat that he seems to favor over her. She famously wrote, “Time spent with a cat is never wasted.”

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Margaret Mitchell

In this photo of the young and beautiful Margaret Mitchell, (author of Gone With the Wind) it’s not clear whether this is actually her cat, but it’s one of those photos you see everywhere.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

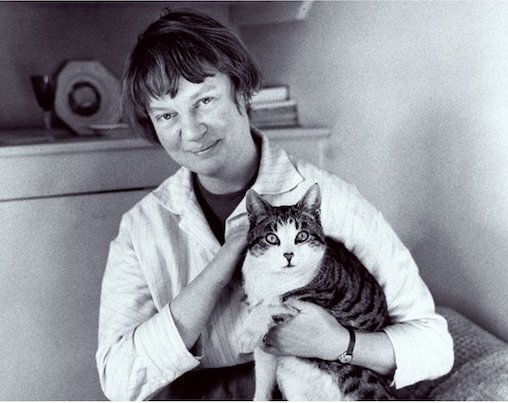

Beverly Cleary

Anyone who has an office or studio that their cat has access to knows that he or she just can’t wait to walk all over your papers. Here’s prolific children’s book author Beverly Cleary(known for the Ramona Quimby series and many others) and her feline companion, around 1955.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Barbara Pym

Barbara Pym became known for her novels about the small comforts of mid-twentieth-century Englishwomen’s daily lives (Excellent Women and many others). In her real life she apparently found comfort in a cat.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Patricia Highsmith

Patricia Highsmith, who broke into print with the classic thriller Strangers on a Train (and later The Talented Mr. Ripley, among many others), was famously a people-hater. But she loved animals, especially cats. A biographer wrote that her relationship with cats “often counted as her longest and most successful emotional connection.”

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Doris Lessing

Nobel Prize-winning author Doris Lessing may have been known for the feminist classic, The Golden Notebook (and later, complex novels in the science fiction realm), but she was so enamored of her feline companions that she produced a little-known memoir, On Cats (2008).*

. . . . . . . . . . . .

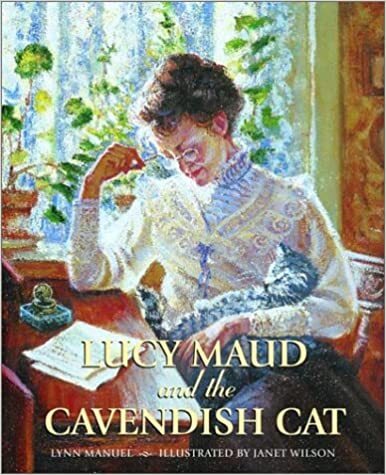

L.M. Montgomery

L.M. Montgomery, Canadian author of the beloved Anne of Green Gables series was a cat lover and a great observer of both human and cat nature. Drawn from her journals, Lucy Maud and the Cavendish Cat* tells of the constancy of her feline companion as she struggled to produce her first writings. In Anne of the Island, a character says of cats: “I love them, they are so nice and selfish. Dogs are TOO good and unselfish. They make me feel uncomfortable. But cats are gloriously human.”

. . . . . . . . . . . .

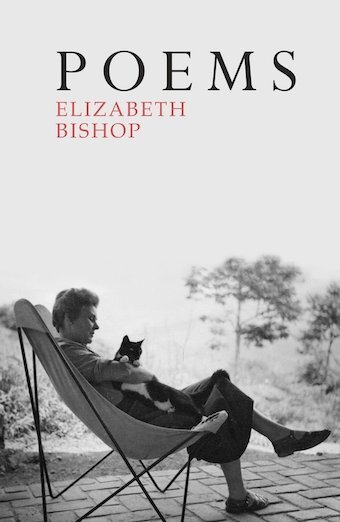

Elizabeth Bishop

Esteemed poet Elizabeth Bishop was a lifelong cat lover, starting with her childhood cat, Minnow. Here’s an early poem, “Lullaby for the Cat,” with the odd line, “Not a kitten shall be drowned / In the Marxist State.”

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Ursula K. Le Guin

When the brilliant fantasy writer Ursula K. Le Guin was alive, she wrote an online journal from the perspective of her black-and-white cat, Pard. Here are some of them. Le Guin expressed her love for felines in her children’s series, Catwings.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Iris Murdoch

Iris Murdoch, the Irish-born British novelist and philosopher is evidently quite cozy with this cat, but details about her feline friend are hard to come by.

. . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post 10 Classic Women Authors and Their Cats appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 28, 2022

“Wilder, Eve” – Else Lasker–Schüler’s Vision of Woman in Eden

Along with Nelly Sachs and Paul Celan, Else Lasker-Schüler (1869 – 1945) was one of the most important German-Jewish poets of the twentieth century. And along with August Stramm and Georg Trakl, she was one of the most important early German expressionist poets.

This look at one of her best-known works is adapted from the forthcoming Wilder, Eve, Some Early Poems of Else Lasker-Schüler, translated by Francis Booth. Reprinted by permission.

Born Elizabeth Schüler into a middle-class banking family in what is now Wuppertal, Germany in 1869, she began writing poetry very early, imagining herself as a child living in the Orient, a fantasy that persisted throughout her life.

Else Lasker-Schüler later lived a bohemian life among writers, artists, and intellectuals in Berlin, where she moved to train as an artist in 1894 with her first husband, physician, and chess master Jonathan Berthold Lasker.

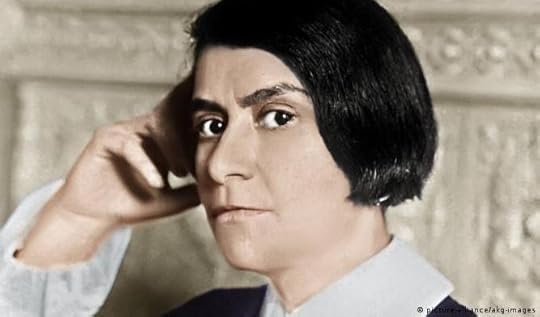

. . . . . . . . . .

Else in her youth

. . . . . . . . . .

Else and Jonathan divorced in 1903 and in the same year Lasker-Schüler married the artist Georg Lewin, who founded the seminal expressionist magazine Der Sturm, which pioneered the new art movement and published all of its leading figures, including Else herself. She called her new husband Herwarth Walden, after Thoreau’s Pond.

After their divorce, Lasker-Schüler was left in poverty and without an outlet for her art and poetry. She soon formed a close friendship with Franz Marc of the Blue Rider group of painters; they exchanged illustrated postcards and letters, many of which are still extant and have been published.

In a dedication in her 1917 Collected Poems, from which all the translations in this book are taken, Lasker-Schüler says. The cover, drawn by me, I give to Franz Marc.

In 1912 she also became close, both romantically and artistically, to the expressionist poet Gottfried Benn, formerly a pathologist who dissected hundreds of bodies in 1912/1913, around the time of the publication of his first volume, Morgue and other Poems.

While in Berlin, Lasker-Schüler embraced political activism, writing, and agitating against the publishing industry and in favor of animal rights, artists’ rights, and Jewish causes. Although not explicitly a feminist, she advocated and herself always used “gender-just” grammar, anticipating by over 100 years the recent debates over “das Gendern” / gendering.

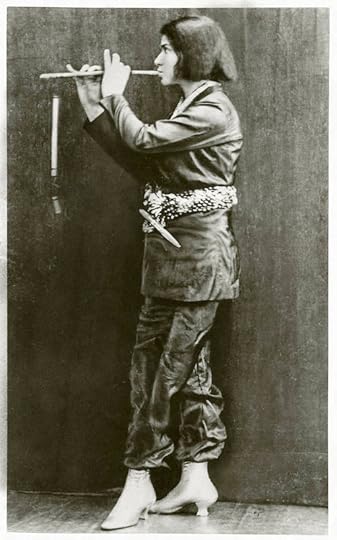

. . . . . . . . .

Else in 1932

. . . . . . . . .

Else lived in Berlin until 1933, when she fled Nazi persecution, despite having won the prestigious Kleist Prize in 1932, first living in Switzerland but finally settling in Jerusalem where she lived until her death in 1945.

In Israel, she lived a life of poverty and eccentricity, mocked by local children for her strange behavior and mode of dress. Lasker-Schüler formed a literary salon in Jerusalem called Kraal, which was opened by Martin Buber in 1942, but its meetings were banned since they were held in German.

This book of translations takes its title, Wilder, Eve – the comma is crucial – from the poem Die Stimme Edens / “The Voice of Eden,” where Lasker-Schüle addresses the “Wilder Eve,” or rather, where she advises Eve to be wilder, to embrace her ‘wild’ or independent self.

The German word Wilde has several implications here, all of which may be intended to portray Else’s original woman as the outsider, a role she advocates all women embracing: eine Wilde is a wild woman; wilde(r) can refer to a student who does not belong to any fraternity/sorority or to an independent official who does not belong to any party; wilderer means poacher. The word I have translated as “womb” in the third stanza (Schoß) can also mean lap or bosom.

Wilder, Eve

Wilder, Eve, confess to straying,

Your desire was the snake,

Its voice writhed over your lip

And bit at the hem of your cheek.

Wilder, Eve, confess to raging,

The day that you wrested from God

Since you saw the light too early

And into the blind chalice sank shame.

Colossal

Ascending out of your womb

At first like fulfilment fearfully,

Then gathering itself impetuously

Creating spontaneously

God’s soul . . .

And it wakes

Beyond the world,

Its beginnings lost,

Beyond all time,

And back to your thousand-heart,

End outstanding . . .

Sing, Eve, your anxious song alone,

Lonely, drop-heavy as your heart beats,

Loosen the dark cord of tears

That lays down on the neck of the world.

How the moonlight changes your countenance.

You are beautiful . . .

Sing, sing, hark, to the sound of carousing

Plays the night and knows nothing of events.

Everywhere the deaf roar —

Your fear rolls over the earth’s steps

Down God’s back.

There is hardly a space between him and you

Hide yourself deep in the eye of the night,

That your day may wear night-dark.

Stifle heaven, that bends itself towards stars

Eve, shepherdess, they coo

The blue doves in Eden.

Eve, turn round before the last hedge yet!

Do not cast shadows with yourself,

Bloom, seducer.

Eve, you are called eavesdropper

Oh you foam-white grape

Refugee still from the tip of your slenderest eyelash.

. . . . . . . . .

Else Lasker-Schüler as her character Prince Yussuf, 1912

. . . . . . . . .

Quotes by Else Lasker-Schüler“I was born in Thebes (Egypt), though I also came into the world in Elberfeld, in the Rhineland. I went to school until I was 11, became a Robinson, lived in the Orient for 5 years, and I have been vegetating ever since.” (Mankind’s Twilight, 1920)

. . . . . . . . . .

“At the age of five I wrote my best poems; my mother always found the scribbled scraps of paper that came out of my clothes pocket when I took out the favorite buttons from my button collection.” (Collected Works)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Whether one plays with green, purple, and blue stones or whether one writes poems, it is exactly the same. (Letters to Karl Kraus)”

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post “Wilder, Eve” – Else Lasker–Schüler’s Vision of Woman in Eden appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 11, 2022

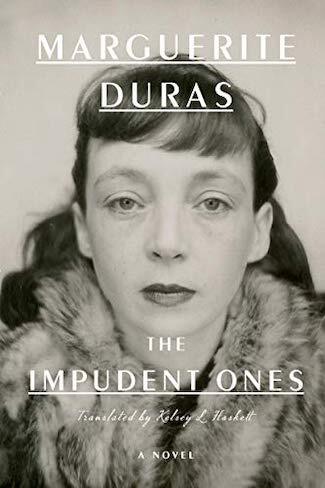

Marguerite Duras, author of The Lover

Marguerite Duras (April 4, 1914 – March 3, 1996), born Marguerite Germaine Marie Donnadieu, was a French novelist, screenwriter, playwright, filmmaker, and essayist.

Her work was largely shaped by her childhood in present-day Vietnam and received several awards, including the Prix Goncourt for her novel The Lover, and an Academy Award nomination for the screenplay of Hiroshima Mon Amour.

Early life and education

Duras was born in Gia Định, just north of Saigon in Vietnam (then known as French Indochina) in 1914. Her mother Marie was headmistress of the local girl’s school, and her father Henri was a math teacher. She also had two older brothers, Pierre and Paul.

Soon after the family had settled there, her father became ill with amoebic dysentery and returned to France, where he died shortly afterward. Her mother decided to stay to raise her children in Indochina, but the family struggled financially: a bad investment in a rice farm that flooded regularly left them in poverty (something Duras later wrote about in her novel The Sea Wall).

Her childhood in Vietnam and the experience of colonial living was a profound influence on her later writing: in a 1985 interview, she said, “It’s as if I had no birthplace — I did have one, but it’s far away. I’ve never been able to go back … But the past is perhaps here in the present. This place is already in the past. I can use it to say exactly what I want, about life, I mean.”

Duras attended the French lycée (high school) in Saigon, then moved to France at the age of seventeen to complete her education. She started by studying math, then switched to law and politics. She earned her degree in public law from the Sorbonne in 1937 and found a job working for the Ministry of the Colonies.

. . . . . . . . .

Photo: Le Temps

. . . . . . . . .

In 1939, she met and married her first husband, Robert Antelme, also a writer. Their only child was stillborn in 1942.

During World War II, Duras worked for the Vichy government, then, from 1943 both she and Robert were active members of the French Resistance. They were part of a small group called Richelieu which included the future president François Mitterand, who remained a lifelong friend.

In 1944, her husband was arrested for his Resistance activities and was sent to Buchenwald and Dachau. He survived, but barely: according to Duras, he weighed a terrifying 38 kilos (84 pounds) when he returned to France. She nursed him back to health but was already in love with Dionys Mascolo, who became her second husband and father of her only child, Jean. She divorced Robert not long after the war.

It was around this time that Duras also became a member of the French Communist Party. She was later expelled in 1950 for protesting against the Prague Uprising but remained a politically active Marxist throughout her life.

She protested against the Algerian War, and later, in 1971, signed the Manifesto of 343, a petition signed by that number of French women stating that they’d had an abortion. At the time, when abortion was illegal in France, signing was considered an act of political and civil disobedience. The text of the manifesto, written by Simone de Beauvoir, read:

“One million women in France have abortions every year. Condemned to secrecy, they do so in dangerous conditions, while under medical supervision, this is one of the simplest procedures. Society is silencing these millions of women. I declare that I am one of them. I declare that I have had an abortion. Just as we demand free access to contraception, we demand the freedom to have an abortion.”

The manifesto was published in Le Nouvel Observateur and influenced a change in the law that legalized abortion in 1975.

Writing, and The Lover

Duras’s true passion lay in writing. Her first novel, Les Impudents, was published in 1943, and it was then that she began using the name Duras, after the town that her father originated from in the region of Lot-et-Garonne.

Her most famous novels include The Sea Wall, Moderato Cantabile, The Ravishing of Lol Stein, and The Lover. The latter, published in 1984, is the story of a teenager falling in love with a Chinese man. It became her most well-known novel, winning the Prix Goncourt and selling over three million copies in France alone. It was translated into forty languages.

The Lover is an elusive, hazy story, like faded snapshots of the past, and Duras’s claim that it was almost entirely autobiographical cemented its notoriety. But the New York Times noted that “truth, in the Durasian universe, is a slippery entity.”

Truth is perhaps blended with fiction: Duras did most likely have a Chinese lover at the age of fifteen, but it was not the sexual and romantic awakening that the novel portrays, and she was writing the book at the age of seventy when the details may have been (deliberately or otherwise) blurred.

Duras often claimed to be surprised at the praise the book received, saying that she herself never liked it that much. She even went so far as to rewrite it, in the form of notes to a film, as The North China Lover.

“The Lover is a load of sh–,” she once said. “It’s an airport novel. I wrote it when I was drunk.” This, however, could be taken with a pinch of salt and as another example of the “slipperiness” of her version of the truth: later she would claim, “People who say they don’t like their own books, if such people exist, do so because they haven’t learned to resist the attraction to humiliation. I love my books. They interest me.”

For Duras, writing was both a substitute for living and a way of engaging with the world. “In my life,” she once said, “I am more of a writer than someone who lives.” Things happened to her “that she never experienced.” She often spoke and wrote about herself in the third person, particularly in her journals.

She resisted labels for her writing and dismissed trends in literature: instead, much of her work is focused on human sexuality, the erotic, and the nature of desire.

Film adaptations and filmmaking

Many of Duras’ books were made into films. The Sea Wall was first adapted as This Angry Age in 1958 directed by René Clement, and then again in 2008 as The Sea Wall directed by Rithy Panh.

Moderato Cantabile was the inspiration for the 1960 film Seven Days… Seven Nights by Peter Brook, while The Lover was made into a film in 1994, a decade after it was published, directed by Jean Jacques Annaud.

Duras was also a screenwriter and filmmaker herself, and during her life directed a total of eighteen films. She wrote the play India Song and directed the film of it in 1975.

She also wrote the screenplay for the 1959 film Hiroshima Mon Amour, directed by Alain Resnais, which tells the story of a French woman’s relationship with a Japanese man during World War II. It was nominated for an Oscar, but the critics were not convinced: the New York Times called it a “Proustian tour de force,” but Films in Review lamented: “That a film so amateur should receive so much critical acclaim is a sad commentary on the state of Western culture…”

Duras’ fluidity between novel and film, prose and screenplay, was an important part of her style and her work. Rachel Kushner, in The New Yorker, wrote that “all of Duras’s work is novelistic in its breadth and profundity, and all of it can be poured from one flask to another, from play to novel to film, without altering its Duras-ness.”

She was much admired by many twentieth-century intellectuals. Jacques Lacan (the noted French psychoanalyst) wrote about her work, and Samuel Beckett said that her radio play, “The Square,” was a significant moment in his own creative life.

Her style was not always appreciated. Particularly in the 1950s, Duras encountered misogyny in publishing, with male critics calling her writing “masculine,” “hardball,” and “virile” (meant as insults, though we might not take them as such today). Even she freely admitted that her natural boldness and forthrightness could be difficult to deal with, saying “I’m not sure I could put up with Duras.”

. . . . . . . . .

Marguerite Duras page on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Duras had a difficult personality, which was compounded by health problems. She suffered from alcoholism and claimed that it had been a problem since she tasted her first alcoholic drink as a teenager. This was exacerbated by her second husband, Mascolo, who also drank to excess.

By the time The Lover was published in 1984 she had separated from him and was living with a much younger man, Yann Andréa Steiner. He had sought her out after reading many of her novels, and despite his homosexuality, became her lover and secretary. It was Steiner who encouraged her to seek treatment for her alcoholism, and who wrote about the rehab experience in a book titled M.D.

Duras was honest and shrewd enough to realize that her alcoholism would have been less of a problem in social terms had she been a man:

“Alcoholism is scandalous in woman … it’s a slur on the divine in our nature.” She could also be honest with herself about the nature of the condition, saying, “It’s always too late when people tell someone they drink too much. You never know yourself that you’re an alcoholic. In one hundred percent of cases, it’s taken as an insult.”

Duras died in Paris on March 3, 1996, and is buried in the Montparnasse Cemetery. Bertrand Poirot-Delpech wrote in Le Monde: “When this diminutive character with the large spectacles and a morning-after voice gets involved … she does so with guts, without restraint.”

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online, and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Marguerite DurasMajor works (Duras’ complete works, including her fiction, essays, and theatrical works is vast; link to her full bibliography here)

The Lover The Ravishing of Lol SteinThe DarkroomDestroy, She Said Wartime Notebooks & PracticalitiesWritingMe & Other WritingThe North China Lover The Impudent OnesBiography

Marguerite Duras: A Life by Laure Adler (W&N, 2000)More information

Marguerite Duras: Worn Out with Desire To Write (video) “On Marguerite Duras” by Rachel Kushner (The New Yorker, 2017) Reader discussion on Goodreads 10 Interesting Facts About French Writer Marguerite Duras. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Marguerite Duras, author of The Lover appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 10, 2022

Books by Rachel Carson: Before and After Silent Spring

Through the gracefully written books by Rachel Carson (1907 – 1964), the noted American marine biologist, conservationist, the public was gifted with a view of the natural world. Undoubtedly, her research and writings shaped the environmental movement.

She wrote eloquently in her nonfiction works, conveying how every living entity interacts with the broader web of life. Though Rachel Carson is known more as a scientist and environmentalist than as a writer, there’s no question that her passion for literature fueled her impassioned writings.

Silent Spring (1962) was her best known work, boldly opening awareness of the harmful use of pesticides. She also wrote three volumes about the oceans, which became known as the “Sea Trilogy” and a book that encouraged families to discover the wonders of nature together.

In addition to her five major works of nonfiction (all of which were bestsellers), a posthumous collection titled Lost Woods: The Discovered Writing of Rachel Carson was published in 1998.

Here, in order of publication, are books by Rachel Carson; all are as relevant as ever, if not even more so.

. . . . . . . . . .

Under the Sea Wind (1942)

Under the Sea Wind was Carson’s first book and the first of what was known as her “Sea Trilogy.” Even in her debut publication, reviewers noted the lyrical quality of prose that she applied to scientific concepts to make them compelling and readable. One such review observed:

“In beautiful lyrical prose, Rachel Carson in Under the Sea Wind stirs the imagination with her portrayal of the endlessness of life and death in the sea. For the sea was the cradle of all life, and still is a shelter for an endless array of living forms in the most eternal cycle of life that is to be found on earth.

… A true lover of the sea, she tells with scientific accuracy of the life of the Atlantic coast, from the soaring gulls on high to the forms that creep over the continental slope and down into the perpetual darkness of the ocean’s abyss.”

Learn more about Under the Sea Wind.

. . . . . . . . .

The Sea Around Us (1951)

First serialized in The New Yorker, by July of 1951, the entirety of The Sea Around Us was published. It made its appearance on The New York Times’ bestseller list, where it stayed for 86 weeks. It won the National Book Award, in January 1952. It was the second book in Carson’s “Sea Trilogy.”

Oxford University Press reissued the book in 2018, providing this description:

“The Sea Around Us is one of the most influential books ever written about the natural world. Rachel Carson’s ability to combine scientific insight with poetic prose catapulted her book to the top of The New York Times best-seller list, where it remained for more than a year and a half.

Ultimately it sold well over a million copies, was translated into twenty-eight languages, inspired an Academy Award-winning documentary, and won both the National Book Award and the John Burroughs Medal.”

Learn more about The Sea Around Us.

. . . . . . . . .

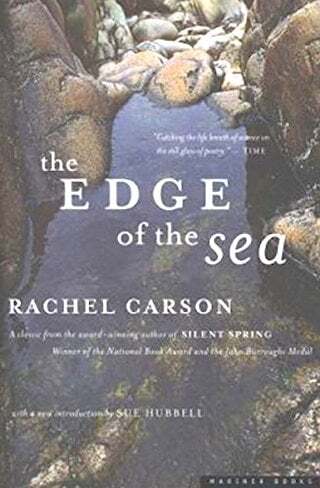

The Edge of the Sea (1955)

The Edge of the Sea was the last book of Carson’s “Sea Trilogy.” A description of The Edge of the Sea from the publisher of the 1998 edition, Mariner Books:

“With all the hallmarks of Rachel Carson’s luminous prose combined with a scientifically accurate exploration of the Atlantic seashore comes a hauntingly beautiful account of what one can find at the edge of the sea.

‘The edge of the sea is a strange and beautiful place.’ Focusing on the plants and invertebrates surviving in the Atlantic zones between the lowest and the highest tides, between Newfoundland and the Florida Keys, The Edge of the Sea is a book to be read for pleasure as well as a practical identification guide.”

Learn more about The Edge of the Sea.

. . . . . . . . . .

Silent Spring (1962)

Silent Spring is the most enduring work of nonfiction by Rachel Carson. In this book, Carson made a passionate argument for protecting the environment from manmade pesticides.

Written with grace as well as passion, it’s an indictment of the pesticide industry that arose in the late 1950s. It lays out a disturbing view of the damage these chemicals can cause to birds, bees, wildlife, and plant life.

Rachel Carson’s official website recognizes how prescient she was: “Silent Spring inspired the modern environmental movement, which began in earnest a decade later. It is recognized as the environmental text that changed the world.”

Learn more about Silent Spring.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Sense of Wonder (1965)

Rachel Carson’s last full-scale book was published a year after her death. Intended to be enjoyed by children and parents together, it was designed to inspire families to explore and appreciate the wonders of nature together.

The book was originally embellished with black & white as well as color photographs by Charles Pratt, many of which were taken along the Maine coast, where Carson enjoyed spending summers. Republished in 2017, the book is as fresh and relevant as it ever was — perhaps even more so, given the alarming state of the environment.

Learn more about The Sense of Wonder.

. . . . . . . . . .

Rachel Carson page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Books by Rachel Carson: Before and After Silent Spring appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

The Edge of the Sea by Rachel Carson (1955)

The Edge of the Sea by Rachel Carson (1955), was the last book of what became known as her “Sea Trilogy,” preceded by Under the Sea Wind (1942) and The Sea Around Us (1951). Her meticulously researched nonfiction writing was known for its graceful and poetic style.

Carson (1907 – 1964) was a noted American marine biologist, conservationist, and writer whose research and graceful writing about the natural world shaped today’s environmental movement.

Her best-known book, Silent Spring (1962), raised awareness about the use of pesticides and contributed to the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

A description of The Edge of the Sea from the publisher of the 1998 edition, Mariner Books:

“With all the hallmarks of Rachel Carson’s luminous prose combined with a scientifically accurate exploration of the Atlantic seashore comes a hauntingly beautiful account of what one can find at the edge of the sea.

‘The edge of the sea is a strange and beautiful place.’ Focusing on the plants and invertebrates surviving in the Atlantic zones between the lowest and the highest tides, between Newfoundland and the Florida Keys, The Edge of the Sea is a book to be read for pleasure as well as a practical identification guide. Its appendix and index make it a great reference tool for those interested in plant and animal life around tide pools.

A new generation of readers is already discovering why Rachel Carson’s books have become cornerstones of the environmental and conservation movements.”

. . . . . . . .

See also: Under the Sea Wind

. . . . . . . .

From the original review of The Edge of the Sea in The Virginian-Pilot, October 30, 1955: It’s hard to imagine anyone on the face of this earth not being enthralled by Rachel Carson’s The Edge of the Sea.

We say the face of the earth advisedly, for while her earlier book, The Sea Around Us, opened up a whole fascinating new world, it was a world only a few could penetrate by actual experience.

The edge of the sea we do know, or may think we know, until we have read her book; for it is marginal land. But, as she herself points out, “For no two days is the shore line precisely the same … always the edge of the sea remains an elusive and indefinable boundary.”

Specifically, she writes of our own Atlantic coastline, which she divides into The Rocky Shore at the north, The Rim of Sand from Cape Cod southward, and The Coral Coast, with its jagged reefs, mangroves, and brilliant sea gardens, off Florida.

She calls into account not only the differing physical realities of the coast, but the biological role played by the sea: “The ocean currents are not merely a movement of wanter; they are a stream of life, carrying always the eggs and young of countless sea creatures.”

Carson writes in detail of the teeming, complex lives of these millions of creatures, many of whom you will recognize — crabs, whelks, moon snails, coquinas, conches, seahorses, and even jellyfish.

Many you will never have dreamed of live as close to home as Virginia Beach, Nags Head, Myrtle Beach, and Sea Island.

. . . . . . . .

See also: The Sea Around Us

. . . . . . . .

Throughout there is a sense of the ancient oceanic past, the flow of time — to what unknown future? With these creatures who surge against the shifting shore, “seeking a foothold, establishing new colonies,” the pattern changes constantly, along with the inexorable drive for life.

Sand, seaweed, and the creatures of the shore will never seem the same to you again.

Drawings are abundant in this book and add immeasurably to its charm. In black and white by Bob Hines of the Fish and Wildlife Service, they more than overcome their lack of the colors Miss Carson so vividly conveys with words. They are sensitive, powerful drawings.

The Edge of the Sea is a handbook of knowledge, beautifully written — and a new insight into the enormous, mysterious life around us.

With all the hallmarks of Rachel Carson’s luminous prose combined with a scientifically accurate exploration of the Atlantic seashore comes a hauntingly beautiful account of what one can find at the edge of the sea.

“The edge of the sea is a strange and beautiful place.” Focusing on the plants and invertebrates surviving in the Atlantic zones between the lowest and the highest tides, between Newfoundland and the Florida Keys, The Edge of the Sea is a book to be read for pleasure as well as a practical identification guide.

Its appendix and index make it a great reference tool for those interested in plant and animal life around tide pools. A new generation of readers is already discovering why Rachel Carson’s books have become cornerstones of the environmental and conservation movements.

. . . . . . . .

The Edge of the Sea on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Edge of the Sea by Rachel Carson (1955) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 9, 2022

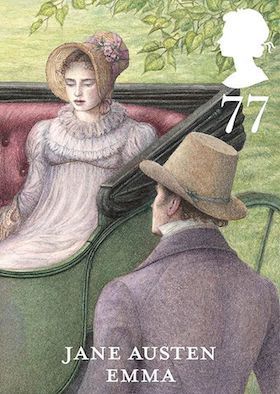

The Six Brilliant Novels of Jane Austen (plus Sanditon)

It’s a testament to an author when a relatively small body of work endures through the ages. The six brilliant novels of Jane Austen have not only stood the test of time, but have continued to be adapted for film and television (not to mention fanfiction by other authors, a list far too vast to enumerate).

With six exquisite novels displaying compassion, humor, and insight into the travails of the sexes and social classes, Jane Austen’s place in literary history is forever secured.

Despite the popular portrayal of her as all charm and modesty, she was a writer and observer of human nature with full mastery of her gifts. She cared deeply about getting published and being read, despite myths to the contrary.

Here is an overview of her six classic novels of Jane Austen (plus Sanditon, which was unfinished at the time of her death. At the end of each title’s entry, you’ll find a link to a full plot summary and analysis.

. . . . . . . . .

Sense and Sensibility (1811)

There can be little doubt that in Sense and Sensibility we have the first of Jane Austen’s revised and finished works. In several respects, it reveals an inexperienced author.

The action is too rapid, and there is a want of dexterity in getting the characters out of their difficulties. Mrs. Jennings is too vulgar, and in her, as in several of the minor characters, we see that Jane had not quite shaken off the turn for caricature, which in early youth she had possessed strongly.

Sense and Sensibility was originally called Elinor and Marianne, but it might as appropriately have been named The Dashwood Family, for it is really the history of one family, of whom two sisters are nominally the chief characters, but by no means the most interesting; and the other personages of the story, as was so usual with Jane Austen, only revolve round the central characters.

The disagreeable story of Willoughby’s earlier life is unnecessary to the plot, Colonel Brandon is too shadowy to be interesting, and Margaret Dashwood, the third sister, is an absolute nonentity.

Nevertheless, there is much in it that is good. The John Dashwoods; Elinor, Marianne, and their mother; the Middletons, and Mrs. Palmer are all excellent, and, remembering it as the work of a girl of twenty-one, its promise for her future success was very great.

It can never be put aside by anyone as wholly unworthy of her powers; all that the most severe critic could say is that it is not quite up to the mark of her later, more matured writing, and this is, indeed, a faint condemnation which would be praise for almost any other author.

Read more about Sense and Sensibility.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Pride and Prejudice (1813)

No admirer of Elizabeth Bennet will wonder that her delineator could not find a satisfactory portrait of her, for she is a vary rare type of character; indeed, it is a distinguishing characteristic of Pride and Prejudice that both the hero and heroine are uncommon in every respect, and yet thoroughly lifelike.

A shade more of gaiety would have made Elizabeth a flippant, amusing, commonplace girl, just as a degree less intellect would have made Darcy as intolerable as Mrs. Bennet thought him. But Jane Austen had shaken off all tendency to exaggeration by the time she brought out Pride and Prejudice, and henceforth her characters are kept well within bounds.

We see in Darcy the man who has had everything to spoil him yet is really superior of being spoilt. He is handsome, wealthy, well-born, and of powerful intellect, and the adulation and submission he has always had from everyone about him wearies him into receiving such homage with cold indifference and apparent haughtiness. Yet under this repellent exterior is a warm, generous, and tender heart, which is capable of great sacrifices for anyone he really loves.

Elizabeth Bennet is exactly the right wife for him, for, with a nature as capable of tenderness and constancy as his, she has all the simplicity, brightness, and playfulness which are wanting in him.

Yet from the day that she and Mr. Darcy first meet they take a mutual aversion to each other, and long after he has succumbed, and fallen in love with her, she is unconscious of his feelings, and continues to dislike him.

Read more about Pride and Prejudice.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Mansfield Park (1814)

Mansfield Park is the story of Fanny Price, sent by her impoverished family to be raised in the household of a wealthy aunt and uncle. The story follows her into adulthood and is a commentary on class, family ties, marriage, and the status of women.

The novel went through two editions before Jane Austen’s death (1817) but didn’t receive any public reviews until 1821. Critical reception for this novel, from that time forward, has been the most mixed among Austen’s works.

In an introduction to a contemporary edition, Kathryn Sutherland portrays Mansfield Park as a darker work than Austen’s other novels, because it challenges “the very values (of tradition, stability, retirement, and faithfulness) it appears to endorse.”

Mansfield Park is lengthy, but this can hardly be considered a blemish, as it was the deliberate intention of the author, and, after all, it is “readable from cover to cover.” The only part that could appear to anyone unnecessary is Fanny’s visit to her relations at Portsmouth, and no one would wish to lose so good a picture of the home mismanaged by the incapable wife and mother.

From first to last Fanny Price is charming, and, seeing how admirably her character is worked out, Mansfield Park cannot be considered too long for art, as it certainly is not too long for enjoyment.

Read more about Mansfield Park.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy …

Jane Austen’s Childhood and Glimpses as a Young Woman

First Attempts at Publishing

Jane Austen’s Final Days — Illness, Courage, and Death

. . . . . . . . . . .

Emma (1815)

Many readers of Jane Austen will agree in thinking that in Emma she reached the summit of her literary powers. She has given us quite as charming individual characters both in earlier and later writings, but it is impossible to name a flaw in Emma; there is not a page that could with advantage be omitted, nor could any additions improve it.

The story, as usual with Jane Austen, is a mere thread of the most everyday kind: the loves, hopes, fears, and rivalries of a dozen people, with all their home lives and surroundings. But every one of the characters stands out clearly from the canvas, and all are life-like and delightful.

It has all the brilliancy of Pride and Prejudice, without any immaturity of style, and it is as carefully finished as Mansfield Park, without the least suspicion of prolixity.

In Emma, too, as has been already noticed, she worked into perfection some characters which she had attempted earlier with less success, and she gave us two or three, such as Mr. Weston, Mrs. Elton, and Miss Bates, which we find nowhere else in her writings.

Moreover, in Emma, above all her other works, she achieved a task in which many a great writer has failed; for she gives us the portrait of a thorough English gentleman, drawn to the life.

Read more about Emma.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Northanger Abbey (1817)

The first novel intended for publication by Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey was originally titled Susan. Completed in 1803, it wasn’t published until 1817, the year of the author’s death. This coming-of-age novel’s heroine, Catherine Morland, at first young and rather naïve, learns the ways of the world in the course of the narrative.

Set in Bath, England, the fashionable resort city where the Austens lived for a time, Jane Austen critiques young women who put too much stock in appearances, wealth, and social acceptance. Catherine values happiness but not at the cost of compromising one’s values and morals.

Sarah Fanny Malden, the 19th-century critic whose detailed plot summaries and analyses of Jane Austen’s works are reprinted on this site, felt that Northanger Abbey is inferior to the author’s other novels:

“I think that Catherine Morland, though in many respects attractive, is the most uninteresting of Jane Austen’s heroines, and betrays the writer’s youth. Emma Woodhouse (of Emma) Fanny Price (of Mansfield Park), and Elizabeth Bennet (of Pride and Prejudice) are all women we should like to have known. For Anne Elliot (of Persuasion), what words of praise are high enough?

But Catherine Morland is an obvious copy of Evelina: a good-hearted, simple-minded little goose … Perhaps Jane Austen felt this herself, for she closes the story with a playful account of their marriage, and makes no attempt to picture their future life together.”

Read more about Northanger Abbey.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Persuasion (1817)

Persuasion, the last novel Jane Austen wrote, along with Northanger Abbey, her first completed novel, were both published six months after her death in 1817.

In approaching Persuasion, we have to deal with the last, and, in my opinion, the greatest of Jane Austen’s works, for though Emma usually holds the first place in her writings, and although there are unquestionably one or two weak points in Persuasion from which Emma is free, I cannot but heartily state that “Persuasion is the most beautiful of all Jane Austen’s stories.”

Dear, charming Anne Elliot! We rejoice to feel that we are leaving her in the midst of such a tender, radiant Indian summer of happiness; and we safely predict a married life at blessedness for her and her husband; but even in this crowning hour of their felicity, there is the same tinge of pathos visible as throughout the book.

It does not seem intentional; it is rather as though the writer could no longer treat her subject with the bright gaiety of former days, and it is not wonderful that a dying woman could not.

Persuasion is the swan song of Jane Austen’s authorship, and, true to its character, the saddest and sweetest of her works. When she finished it, only a few months before her death, she had in fact laid down the pen for ever; and doubtless it was the consciousness of this which shaded the story to a more autumnal tone than anything she had yet written.

We could not wish it otherwise, for the group of novels would have been incomplete without some such story of comparatively late happiness.

Read more about Persuasion.

. . . . . . . . . . .

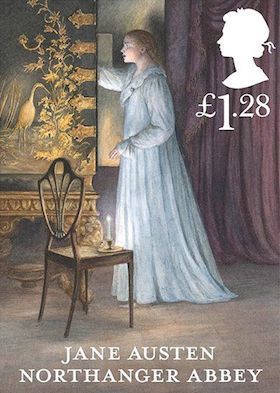

Sanditon: An unfinished novel

Contributor Adam Burgess begins his musing on Jane Austen’s unfinished novel as follows: Sanditon, though unfinished, is perhaps Jane Austen’s most exciting, unusual, and promising piece of literature. Unlike The Watsons, whose plot and ending can be relatively inferred, Sanditon, the novel she worked on in 1817, the year of her death, is quite different from any of her other stories.

The narrative of Sanditon could probably have followed a variety of paths, so predicting its resolution is difficult to do.

The story’s heroine, Charlotte Heywood, is a somewhat-exaggeratedly sensible young woman. She comes to the small coastal tourist town of Sanditon upon the urgings and guardianship of its proprietor, who is attempting to build the town’s reputation.

The rest of the story’s cast are also exaggerated, but in different ways, most of them being comic caricatures – folks obsessed with false ailments, shoddy business ventures, tourism, and the like.

Read more about Sanditon.

More about the novels of Jane Austen Complete Works of Jane Austen Austen’s Novels: An Overview Ranked: The Novels of Jane Austen

The post The Six Brilliant Novels of Jane Austen (plus Sanditon) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

July 1, 2022

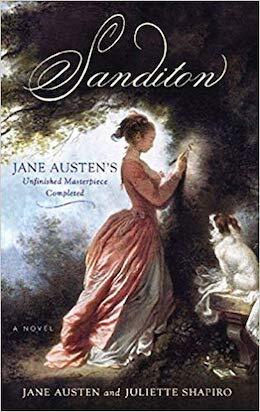

Anita Brookner, author of Hotel du Lac

Do you know of anyone who wrote twenty-six novels after a successful career as a professor and art historian? Or who won the prestigious Booker Prize for her fourth novel? All that is true of British author Anita Brookner (July 16, 1928 – March 10, 2016), which is why I enjoy her books so much — she entertains as well as educates.

I liken Brookner’s beautifully crafted stories to fine needlework, and I’ve recently started collecting her books, as I know I will reread them over the years.

Surprised by the Booker Prize; a prolific career

I discovered Anita Brookner in 1984 when she won the Booker Prize for Hotel du Lac, the story of a romance writer who commits an indiscretion and heads to Switzerland to sort herself out.

In researching Brookner’s life, one favorite moment was watching the BBC clip from the award ceremony where she sat at a table with other nominees, including J.G. Ballard (whose book Empire of the Sun was favored) and Julian Barnes.

When Brookner’s name was announced, she seemed utterly gobsmacked, made a short acceptance speech, and sat down again. Many critics thought her book was undeserving; however, the judges found her prose stellar, the plot ironic and witty. In all, the novel was deemed “a work of perfect artifice.”

For someone who was born at a time when females were judged by whom they married and what kind of mothers they were, she left a different mark. Brookner was an eminent art historian and professor who also wrote three respected tomes on the painters Greuze, Watteau, and David.

To this list, Brookner added more than two dozen novels (some romans a clef) numerous articles, and an e-book written near the end of her life.

She produced a novel a year for two decades, won many awards, including a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (one tier down from knighthood), and was nominated for a second Booker Prize for her novel The Next Big Thing (2002). (An elderly man is trying to decide on the final chapters of his life — should he travel? Should he marry?)

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo: Tyler Scott

. . . . . . . . . .

Anita Brookner was born in Herne Hill, a suburb of London, to Polish Jewish emigres in 1928. The family surname of her parents, Newson and Maude, was originally Bruckner. Her father decided he didn’t want to have a Germanic name in the World War I era, hence the change.

Her mother, Maude, was a professional classical singer. Her father fought in World War I for Britain. After the war, he started his own businesses, none of which were successful; he ended up working for his wealthy father-in-law, who owned a tobacco factory.

The Brookners lived in a villa with various relatives as well as refugees they’d taken to work as family servants. Anita was an only child. Her parents had a rocky marriage — her mother felt she had married beneath her — perhaps why missed signals, angst between the sexes, and the outsider status of foreigners figure so prominently in Brookner’s canon.

Despite his business problems, her father ran a lending library for a time, introducing his young daughter to classic authors like Charles Dickens and H.G. Wells. From a young age, Anita understood the joy and power of the written word.

Anita attended a girls’ school in Dulwich, then earned a bachelor’s degree in history from King’s College of London. Disliking most of her courses, she attended lectures at the nearby National Gallery and was enthralled. A lecturer noticed her interest and suggested she switch her focus to art history, much to her family’s chagrin.

Remember that all this took place at a time when a woman’s goal was to find a suitable husband. But Anita Brookner had other ideas. She changed her studies to art history and pursued a doctorate for several years at the Sorbonne. Her parents’ response to their independent daughter was to cut her off.

A distinguished career teaching art history

Undaunted, she carried on. By 1959, Brookner was teaching art history at Reading University. In 1964, she joined the staff of the Courtauld Institute of Art, where she was considered an authority on 18th and 19th-century art. Much admired by her students, Brookner became the first female Slade Professor of Art at Cambridge.

As Brookner passed the age of fifty, she realized her life had taken a different turn, with no husband, no children, and much time spent taking care of her aging parents. When she began to write fiction at age fifty-three, she described it as having taken place “in a moment of sadness and desperation.”

“My life seemed to be drifting in predictable channels, and I wanted to know how I deserved such a fate,” she was quoted as saying in her New York Times obituary. “I thought if I could write about it, I would be able to impose some structure on my experience. It gave me a feeling of being at least in control. It was an exercise in self-analysis, and I tried to make it as objective as possible — no self-pity and no self-justification. But what is interesting about self-analysis is that it leads nowhere — it is an art form in itself.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Photo: Tyler Scott

. . . . . . . . . .

Her first novel A Start in Life, whose main character is a lonely academic looking for a new hold on life, was published in 1981. Within three years she had won the Booker, England’s most prestigious prize for fiction.

Brooker writes about women, mostly, that are strong and interesting, but unlucky in love. They forge ahead anyway; usually the object of their affections is beneath them so maybe they will be better off.

Brookner’s themes embrace the trenches of life, the pas de deux between the sexes, and the interior life of the lonely. Hers weren’t cozy domestic novels, yet she has been compared to Jane Austen and Barbara Pym (in addition to Henry James).

Jonathan Yardley, former book critic for The Washington Post (and Pulitzer Prize winner) wrote, “Anita Brookner’s novels are miniatures containing within their brief space worlds of feeling, wisdom, and compassion, not to mention quiet, understated wit and seamless prose.”

In his book, Second Reading, Notable and Neglected Books Revisited (2011), Yardley says Brookner’s Look at Me was one of the finest novels written during the last 25 years.

One of the passages he cites in this book describes a lonely reference librarian who works in a medical research laboratory. She befriends a glamorous couple, to her detriment:

“What interested me … was their intimacy as a married couple. I sensed that it was in this respect that they found my company necessary: they exhibited their marriage to me, while sharing it only with each other. I soon learned to keep a pleasant noncommittal smile on my face when they looked into each other’s eyes or caressed each other; I felt lonely and excited. I was there because some element in that marriage was deficient, because ritual demonstrations were needed to maintain a level of arousal which they were too complacent, perhaps too spoilt, even too lazy, to supply for themselves, out of their own imaginations. I was the beggar at their feast, reassuring them by my very presence that they were richer than I was. Or indeed could ever hope to be.”

Added Yardley, “Brookner’s style of narrative – reflective, measured, expository – is, in her hands, exactly right; her prose alone, is quite simply, exquisite. I cherish her novels almost without reservation and I cherish Look at Me above all.”

An often misunderstood novelist

Julian Barnes, the novelist and a friend of Brookner’s, believes the critics and press, mostly males, seem to have misunderstood her work.

Dubbing her “Modest Anita” they decided to pigeonhole her as a lonely spinster whose life had not worked out and who consoled herself by writing novels, once a year, as a regular act of comfort. They also tended to ignore her brilliant career as an art historian.

“There is often a moral antithesis in her fiction,” observed Barnes, “opposing those who are virtuous, truthful, genteel, and stylish to those who are monied, course, and careless.” He also wondered if the press would not have been kinder to Brookner if she had published novels every two years rather than each year.

According to Barnes, Brookner refused to live the life of a literary celebrity. She wasn’t an aggressive self-promoter; if she went to a book signing event, she was more inclined to sign several copies and then leave before too many people showed up.

Her novels tend to be short, usually around two hundred pages. They engage the reader from the first line. Fraud (1992) begins, “When Anna Durrant disappears, it is months before anyone notices. . . “) Yet her plots are neither formulaic nor depressing. Some of her novels are written from a male point of view.

. . . . . . . . .

Anita Brookner page on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Anita Brookner was a talented writer, a monument to hard work and discipline. She smoked a lot, read five newspapers a day, wrote in longhand, and her favorite novel was Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov, a satiric story about a ne’er-do-well nobleman.

She didn’t ascribe to any religion; she had been raised in a secular Jewish family at a time when it was perilous to be Jewish in Europe. A stoic, she kept her private life to herself. She admitted that there had been marriage proposals over the years, just not the right ones. She always regretted not having children.

She once said of writing fiction, “I don’t like writing fiction much; it’s like being on the end of a bad telephone line – but it’s addictive.”

An excerpt from Hotel du Lac, arguably her best-known work:

“You are wrong if you think you cannot live without love. I cannot live without it. I do not mean that I go into a decline, develop odd symptoms, become a caricature. I mean that I cannot live well without it. I cannot think or act or speak or write or even dream with any kind of energy in the absence of love. I feel excluded from the living world. I become cold, fish-like, immobile. I implode. My idea of absolute happiness is to sit in a hot garden all day, reading or writing, utterly safe in the knowledge that the person I love will come home safe to me in the evening. Every evening.”

To read and enjoy Brookner, you have to be on alert: Don’t read her when you’re tired; you need to pay attention. The sentences are expertly laid out and she writes for smart readers who may yet have to look up the occasional word in the dictionary. Her characters may read Proust, think about Stendhal, wonder about Freud, or climb in bed with The Great Gatsby. If a character happens to be in Paris, she may even throw in a few simple French phrases.

Over the years Brookner has been called “the mistress of doom,” and was once asked if she was in love with melancholy. She responded, “I don’t think it’s melancholy. I think it’s seriousness. I think there’s a difference. I think people are frightened of seriousness.”

Anita Brookner died peacefully in her sleep in the spring of 2016 at the age of eighty-seven. She left money and paintings to her friends (she even owned a Manet sketch) and instructed her agent to keep any books, letters, and manuscripts, finished or unfinished, and to destroy the rest. She left the bulk of her estate to Doctors Without Borders, and her final wish, after donating her body to science and cremation, was not to have a funeral.

Contributed by Tyler Scott, who has been writing essays and articles since the early 1980s for various magazines and newspapers. In 2014 she published her novel The Excellent Advice of a Few Famous Painters. She lives in Blackstone, Virginia where she and her husband renovated a Queen Anne Revival house and enjoy small town-life. Her website is Tyler Scott | Pour the Coffee, Time to Write.

More about Anita BrooknerMajor Works

Find Anita Brookner’s complete, prolific bibliography here .More information

Julian Barnes Remembers His Friend Anita Brookner (The Guardian) In Praise of Anita Brookner (NY Times) Encyclopedia of Jewish Women Anita Brookner, the Art of Fiction (Paris Review) Wikipedia Reader discussion of Brookner’s books on Goodreads. . . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Anita Brookner, author of Hotel du Lac appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 29, 2022

Brown Girl, Brownstones by Paule Marshall (1959)

Brown Girl, Brownstones was the first novel by Paule Marshall, a semi-autobiographical story about the Barbadian immigrant community in 1930s and 1940s Brooklyn. Published in 1959, it remained the best-known work in Marshall’s distinguished career.

Paule Marshall (1929 – 2019) was born Valenza Pauline Burke. As a young teen, she became enamored of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poetry and changed her name to reflect his. Her long career was marked by major awards, including the Guggenheim and MacArthur Fellowships; she taught at several universities as well. In the end, her renown circled back and landed at the place where she began — in her first, and very fine novel.

A brief plot summary

The 2009 reprint edition of Brown Girl, Brownstones encapsulates the book:

“Selina’s mother wants to stay in Brooklyn and earn enough money to buy a brownstone row house, but her father dreams only of returning to his island home. Torn between a romantic nostalgia for the past and a driving ambition for the future, Selina also faces the everyday burdens of poverty and racism.

Written by and about a daughter of Barbadian immigrants, this coming-of-age story unfolds during the Great Depression and World War II. Its setting — a close-knit community of immigrants from Barbados — is drawn from the author’s own experiences, as are the lilting accents and vivid idioms of the characters’ speech.

Paule Marshall’s 1959 novel was among the first to portray the inner life of a young Black female, as well as depicting the cross-cultural conflict between West Indian immigrants and African Americans. It remains a vibrant, compelling tale of self-discovery.”

A 1959 review of Brown Girl, Brownstones by Paule Marshall

From the original review in the Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, FL, September 2, 1959: “Brooklyn Author’s Novel is Certain Bestseller”: Like another tree that famously grew in Brooklyn, a new, vigorous and generally captivating one takes root and eventually blooms over there in this first novel titled Brown Girl, Brownstones by Paule Marshall. If a prediction is in order this day, we may all be delighting in it for a long time to come.

Paule Marshall is Brooklyn-born and bred, but in a special world within that tumultuous world of numerous races, many churches and the shades of departed trolleys and Dodgers. The Barbadian colony is her province, to which her parents came from the West Indies sometime before her own first look at this or any other part of the world thirty years ago.

How much of this tender, smoldering tale is her own and her family’s story is not a matter of public report. A good deal of it, one must guess offhand, since she like the remarkable heroine of her novel learned about life in the roar of Fulton St., and went on from there to build a career of her own as a first-generation American. But the parallel doesn’t really matter, except as it stamps these pages with that special conviction of experience truly recaptured.

The first thing about “Brown Girl, Brownstones” that matters, and it strikes you as early as page one, is style. Mrs. Marshall has it. It is a fine, flexible one, relaxing into the rhythms of Barbadian American speech, tense and driving when the Barbadian blood stirs into action, an instrument always under the full control of one to whom the use of language seems as natural as breathing.

“In the somnolent July afternoon the unbroken line of brownstone houses down the long Brooklyn street resembled an army massed at attention,” the story begins. Long ago, in one of those stately, mirrored homes, old Dutch and English families lived. Now it is 1939, and times and tenants have changed.