Nava Atlas's Blog, page 27

May 25, 2022

The Peacock Spring by Rumer Godden (1976)

The Peacock Spring by Rumer Godden is a 1976 novel by the British-born novelist and memoirist who was raised mainly in India at the height of colonial rule. Margaret Rumer Godden (1907 – 1998) led a life was as dramatic and colorful as the stories she so skillfully wrote.

Inspired by her personal experiences and love for the Indian continent, The Peacock Spring is a beautiful and heartbreaking novel of loss of innocence and coming-of-age from the acclaimed author of Black Narcissus and The River.

Despite Godden’s love for the Indian people and continent, it is certainly time to reconsider literature written from the perspective of British colonialism. However, she doesn’t shy away from the harsh realities of wealth and privilege, race and caste in colonial Indian society. As always, her prose is vivid and poetic.

The book was generally well received, and, like the majority of her works, was made into a film of the same title in 1996. Following is a plot summary and a brief review of The Peacock Spring from 1976, the year in which it was published.

A brief plot summary

By Jeanne Rose for the Baltimore Sun, March 28, 1976: Fifteen-year-old Una and her twelve-year-old sister Hal (Halcyon) have come from their English school to New Delhi at the bidding of their father, Sir Edward Gwithiam, a high official in the U.N.

He is lonely and has told their headmistress. But Una and Hal soon realize their presence fills another need: Alix, the beautiful Eurasian governess Edward has hired, is his mistress, and the girls are there as chaperones.

Alix, ambitious and unstable, cannot teach Una; she lacks the background she has claimed. Una, frustrated and ignored, soon drifts into friendship, then more, with her father’s gardener Ravi, a poet and student hiding from the police. When Edward marries Alix, Ravi and Una run away but are soon found. And Una’s “peacock spring” ends in disillusionment and grief.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Peacock Spring on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review by Barbara Hodge Hall in The Anniston Star, AL, Apr 4, 1976: Rumer Godden has abandoned the sunny peace of her last novel, In This House of Brede, to write a brilliant tragedy of color, passion, and violence.

She perhaps overworks the peacock symbolism — the dazzling bird stands for India itself and also for Ravi, splendid but flawed. creates vivid minor characters. No one who reads this book will soon forget it.

For English novelist Rumer Godden. as well as her sister Jon, another talented writer, India is a beloved childhood home, familiar and well-understood, a place of contrasts, beauty, and the same human emotions that govern us all.

Their never-to-be-forgotten Two Under the Indian Sun ten years ago captured their memories of colonial days there, and Rumer, in particular, has turned again and again to that fascinating subcontinent as a setting for her stories.

The Peacock Spring is Rumer Godden at her best, writing about India. young people, and the deep well-springs of love. At once somber and joyous, the novel will be wonderfully welcome after the long wait since In This House of Brede.

Two young sisters have been brought to India by their UN diplomat father, snatched up from boarding school shortly after the beginning of the term, and deposited in his palatial official residence under the questionable tutelage of a beautiful young governess.

It does not take long for Una, the wise. sensitive fifteen-year-old, to realize what is happening — her father, Edward, wants her and pretty twelve-year-old Hal to provide an excuse for Alix’s presence in his household. Edward and Alix are lovers, and New Delhi society is already buzzing with gossip.

The two girls, who are half-sisters, react in far different ways. Hal (short for Halcyon), is already beautiful, vivacious, and eager for life, and is enchanted by the whole arrangement — Alix, parties, horses, admiring boys, and the excitement of new experiences.

But Una, a brilliant student for whom her school had high hopes, is resentful and angry. She is being cheated on her studies. her chances for university, the quiet English way of life she loves. Alix does not fool her for a minute, and the social whirl is just a waste of time.

And then she meets Ravi. the young Brahmin poet masquerading as the second gardener on the estate, a handsome, well-educated boy who alone seems to understand her feelings. What happens is new only to Una, at once innocent and as old as Eve.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Peacock Spring (1996 film) is available to stream on Amazon*

More about The Peacock Spring Out of Time: Rumer Godden’s The Peacock Spring Reader Discussion on Goodreads Review: The Peacock Spring by Rumer Godden. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Peacock Spring by Rumer Godden (1976) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

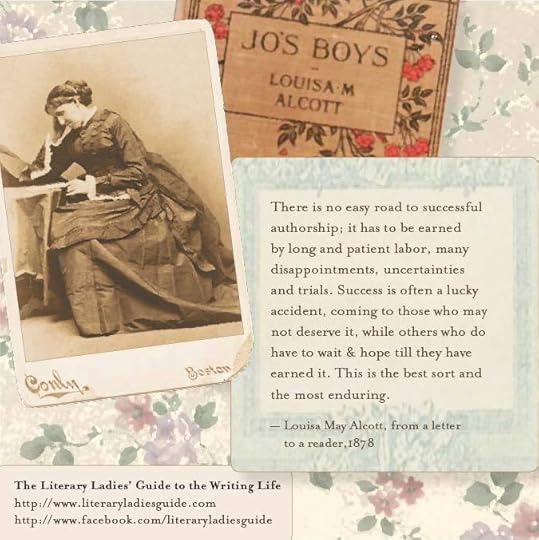

Jane Austen’s First Attempts at Publishing

Jane Austen’s talent was recognized early on and taken seriously by her entire family. Her father and brothers played key roles in getting her works published, as it wasn’t considered proper for a woman to do so herself in the early 1800s. This 19th-century view of Jane Austen’s first attempts at publishing illustrates the difficulties of the pursuit.

Austen longed to see her work in print, regardless of whether or not it would gain her fame or fortune — but getting it published was important to her, contrary to the myth about her extreme modesty.

Her father and brothers took it upon themselves to seek publication opportunities for Jane’s first works. It was clear that she didn’t write merely for her own amusement but was deeply invested in having her work published and read.

Jane Austen by Sarah Fanny Malden (1889) is an excellent resource as a 19th-century view of Jane Austen’s works. The publication was part of an Eminent Women series published by W.H. Allen & Co., London. The following analysis and plot summary of Sense and Sensibility (1811) focuses on this work, which was Jane Austen‘s first published novel. This excerpt is in the public domain:

……… ………

………

From about the age of twenty to twenty-five — that is, during the five last years of her life at Steventon—Jane had fairly taken up her pen and worked hard with it all the time.

At least three of her best-known novels were written during this period, although, from their not having been published till much later, there is difficulty in fixing the exact dates of their composition.

Pride and Prejudice, however, was begun in October 1796, when she was nearly twenty-one, and finished in August 1797. Three months after it was completed, she began upon what we now know as Sense and Sensibility, but with which, as has been already said, she incorporated a good deal of an earlier story, Elinor and Marianne, originally written in letters. She wrote Northanger Abbey in 1798, soon after finishing Sense and Sensibility.

Even in the quiet life at Steventon, it is difficult to understand how Jane managed to combine so much literary work with all her household and social occupations, for so little was writing a serious business to her that she never mentions it in her letters throughout those years.

It is provoking to read through the pages of correspondence with the sister to whom she told everything and to find them full of little everyday details of home life without a single word upon the subject which would be so interesting now to us.

Writing in the midst of comings and goings

It cannot have been from the shyness that she avoided the topic, for her own family knew of her stories when completed, and, wonderful to relate, she carried on all her writing in the little parsonage sitting room, with everyone coming in and out and pursuing occupations there.

This speaks volumes for the Austen family and their friends; for if even one of them had been a Mrs. Allen, or, worse still, a Miss Bates, all Elizabeth Bennett’s and Emma Woodhouse’s doings might have been forever lost to posterity. While perfectly free from shyness or false shame with her own family about her works, Jane was nevertheless careful to keep their knowledge of them from the outer world.

In spite of her writing being so openly carried on, one intimate friend of family wrote afterward that he “never suspected her of being an authoress.” She always used a little mahogany desk—still in existence—which was easily put away if necessary; and she wrote on very small sheets of paper, which could be quickly concealed without attracting any notice.

When we hear of so much steady work between 1795 and 1800, it seems incredible that she published nothing until 1811; but Jane Austen, like other people, was destined to work her way slowly to success, and her first attempts at getting into print were so disheartening that they deserve to be recorded for the benefit of all despairing young authors.

………..

………..

George Austen’s attempts to help Jane get publishedWhen Pride and Prejudice were finished and given to the family circle, Mr. Austen was much struck by the story and determined to make an effort to get it published. Accordingly, in November 1797, he wrote to Mr. Cadell, the well-known London publisher, as follows:

Sir,

I have in my possession a manuscript novel, comprising 3 vols., about the length of Miss Burney‘s Evelina. As I am well aware of what consequence it is that a work of this sort shd make its first appearance under a respectable name, I apply to you. I shall be much obliged therefore if you will inform me whether you choose to be concerned in it, what will be the expense of publishing it at the author’s risk, and that you will venture to advance for the property of it if on perusal it is approved of. Should you give any encouragement I will send you the work.

I am, Sir, your humble servant,

George Austen.

Steventon, near Overton, Hants,

1st Nov. 1797.

Was Mr. Cadell already overwhelmed with novels in imitation of Evelina, or had he made some unlucky ventures in that line, or was he offended by the epithet “respectable” which Mr. Austen applied to him? It is impossible to tell now; but by the return of the post, and without having seen a line of the book, he declined to undertake it on any terms, and Pride and Prejudice remained unknown to the public till sixteen years later.

Probably Mr. Austen made a mistake in not sending the MS. direct to the publisher at first, for if Mr. Cadell had glanced at the first chapter of it, he must have seen it was no ordinary novel.

……….

……….

Not the first unsuccessful attemptNevertheless, this was not the only unsuccessful attempt at a publication that befell Jane Austen. Six years later, in 1803, while living at Bath, she offered Northanger Abbey, which had then undergone careful revision, to a local publisher, who accepted it and gave her—ten pounds!

On second thoughts the worthy man seems to have repented of his bargain, for he never brought it out, and the MS. remained in oblivion for thirteen years longer. By that time Jane Austen had begun to recognize her position as a successful authoress, and thought with justice that if she could recover the MS. it might be published without detracting from her fame.

Henry Austen, her third brother, who often helped her in her communicating with publishers and printers, undertook the errand and found no difficulty whatever in regaining the work, copyright and all, by repaying the original ten pounds.

On this occasion the publisher learned of his error (which Mr. Cadell probably never did); for as soon as Henry Austen had safely concluded the bargain, and gained possession of the MS., he quietly informed the unlucky man that it was by the author of Pride and Prejudice, and left him, we may hope, raging at himself over the opportunity which he had missed of making so good a stroke of business.

Sorrow at the prospect of a move

In 1801 the state of her father’s health brought about the first important change in Jane’s life, for the old home was given up, and she was destined never to spend so much of her life in any other.

The change was a great sorrow to her, but she was allowed very little time to dwell upon it, for Mr. George Austen was a man of prompt decision and rapid action, and having made up his mind, while Jane was away on a visit, that he would leave Steventon, she found, when she returned, that the preparations for departure were being carried on.

Mr. Austen was then upwards of seventy and felt himself no longer fit for the active duties of a clergyman. He did not resign his living but installed his eldest son in them as a kind of perpetual curate, and this arrangement lasted till Mr. Austen’s death in 1805.

At first, the idea of a move was a great grief to Jane, but she was always resolute in seeing the bright side of life, and so she repressed her regrets, and could soon write gaily to her sister:

“I am becoming more and more reconciled to the idea of departure. We have lived long enough in this neighborhood; the Basingstoke balls are certainly on the decline; there is something interesting in the bustle of going away, and the prospect of spending future summers by the sea or in Wales is very delightful.

For a time we shall now possess many of the advantages which I have often thought of with envy in the wives of sailors or soldiers. It must not be generally known, however, that I am not sacrificing a great deal in quitting the country, or I can expect to inspire no tenderness, no interest in those we leave behind.”

A move to Bath

It was fortunate that she had a hopeful disposition to bear her up throughout the worries of house-hunting, and the inevitable discomforts of “a move,” for Cassandra was away at the time, and Mrs. Austen being in delicate health, all the burden fell upon Jane.

Mr. Austen wished to live in Bath, where Mrs. Austen had a married sister, Mrs. Leigh Perrot; so in May 1801 Jane and her parents moved to Bath, where they were to stay with their relatives till they found a house.

Jane’s account of the journey brings before us the gap that railroads have made between her days and ours, for “our journey was perfectly free from accident or event; we changed horses at the end of every stage and paid at almost every turnpike. We had charming weather, hardly any dust, and were exceedingly agreeable as we did not speak above once in three miles.

“We had a very neat chaise from Devizes; it looked almost as well as a gentleman’s, at least as a very shabby gentleman’s. In spite of this advantage, however, we were above three hours coming from thence to the Paragon, and it was half after seven by your clocks before we entered the house. We drank tea as soon as we arrived; and so ends the account of our journey, which my mother bore without any fatigue.”

Composing nothing of importance at Bath

In spite of its dullness, Bath suited both Mr. and Mrs. Austen in many ways, and before long they and their daughters were settled at 4 Sydney Terrace. Sometime later they moved to Green Park Buildings and were there till Mr. Austen’s death in the spring of 1805, when, after a short residence in lodgings in Gay Street, his widow and daughters left Bath “for good.”

Whether the life there had been too full of small bustles for authorship to be easy, or whether the declining health of her parents occupied her too fully for writing, the fact remains that Jane Austen composed nothing of importance while at Bath; perhaps the failure of Northanger Abbey in 1803 disheartened her for a time from further efforts.

One story she did begin, but it was never finished, nor even divided into chapters, so that she cannot have thought seriously of publishing it, and it certainly would not have satisfied her in its present state.

Moving once again, to Southampton

Her next home was in Southampton, where her mother took a house with a garden in Castle Square, and there, Jane was established for four more years of her fast-shortening life.

A friend of hers, Martha Lloyd, to whom she constantly refers in her letters, came to live with them, and this was a source of great happiness to Jane, who frequently mentions her in terms of warm affection. Ultimately Miss Lloyd married Frank Austen, Jane’s youngest brother; but this connection, which would have given her so much pleasure, did not take place till several years after Jane herself had passed away.

The Southampton house was a pleasant one, but the Austens never took root comfortably there, and it is significant of how little Jane felt at home in it, that she wrote absolutely nothing during her four years of Southampton life; not even as much as she had accomplished at Bath.

She had come under circumstances of loss and sorrow which would probably have made any place unattractive to her, and her mother and sister evidently shared her feeling, for as soon as an opportunity occurred of changing their home they gladly seized it.

For some time, Jane had felt herself only a sojourner in strange towns, not really “at home” anywhere; and though she seldom complained of this feeling, it showed itself in the way she had dropped her favorite home pursuit of writing. Now, after the move to Chawton, she dwelt among her own people, and to such a domestic nature as hers, this was a great boon.

A brother comes through

Edward Austen—or Edward Knight as he had now become—deserves the warm gratitude of all Jane Austen’s readers for the arrangement by which his sister found herself again in a real “home,” and felt able to take up once more the writing that she had almost entirely laid aside after leaving Steventon.

As one would like to know whether, on leaving her first home, she ever realized that in that quiet parsonage she had laid the foundations of worldwide fame, so one longs to know whether, on settling at Chawton, she guessed that she should there attain the zenith of her powers and see at least some measure of her future success.

Probably neither idea ever occurred to her; she was too simple-minded to think much of herself and her works at any time, and her principal feeling would have been a peaceful satisfaction at finding herself once more in a house that she could really call “home,” blessed with the continual companionship of her sister, as well as her dearest friend, and enjoying the country life that was associated with her earliest childish recollections.

The post Jane Austen’s First Attempts at Publishing appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 17, 2022

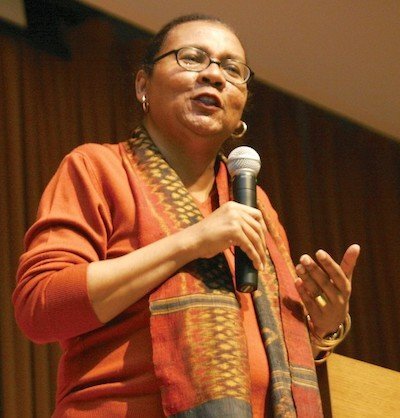

bell hooks, Poet, Essayist, & Public Intellectual

In her lifetime of sixty-nine years, bell hooks (born Gloria Jean Watkins, September 25, 1952 – December 15, 2021) became internationally recognized and highly acclaimed as a prolific writer, beloved poet, university professor, public intellectual, social activist, and cultural critic.

Her legacy of written work (which included forty books) and her contributions to the public discourse on the intersectionality of race, gender, love, feminism, and capitalism is inestimable.

Margaret Atwood, author of The Handmaid’s Tale stated, “Her impact extended far beyond the United States; many women from all over the world owe her a great debt.”

The influential writer and thinker Roxane Gay tweeted, “Oh, my heart, bell hooks. May she rest in power. Her loss is incalculable.”

Since 2004, hooks had served as the Distinguished Professor in Residence at Berea College, a liberal arts institution near Lexington, Kentucky that offers its students free tuition. In 2014, she established the bell hooks Institute at Berea College and three years later, in 2017, she donated her papers to its collection.

“The family is honored that Gloria received numerous awards, honors, and international fame for her works as a poet, author, feminist, professor, cultural critic, and social activist. We are proud to just call her sister, friend, confidante, and influencer,” the family’s statement concluded.

“Poetry sustains life … Of this I am certain. There is no doubt in my mind that the pain of poverty, whether material or emotional lack, can be eased by the power of language. For in that misunderstood childhood of mine, I found that sanctuary of poetry. It restored me, allowed me to come back from the place of roundedness and sadness to a recognition of beauty.” (from Wounds of Passion: A Writing Life by bell hooks, 1999)

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Early life and educationHopkinsville, Kentucky, where bell hooks was born on September 25, 1952, is a small rural town located in the southwestern corner of the state. Her father was a janitor and postal worker. Her mother worked as a maid for white families, and later as a homemaker.

When hooks was growing up, every aspect of Hopkinsville was segregated. She didn’t attend any non-segregated schools until nearly the end of high school.

hooks learned the intricacies of her Southern town’s racist and sexist structure and how to function within those boundaries from the close-knit African American community of Hopkinsville. From an early age, she knew she had to leave Hopkinsville and considered the liberating possibilities of education as her ticket out of town.

hooks’ family didn’t understand her need for an inner life, which included her compulsion to write in her journal, her passion for words, and obsessive reading. For hooks, writing was a needed relief to shield her from criticism.

“Living as we did — on the edge — we developed a particular way of seeing reality. We looked both from the outside in and from the inside out.” (from Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center by bell hooks, 2000)

Literary influences

By the time she left Kentucky for Stanford in 1971, hooks’ literary influences were Zora Neale Huston, William Wordsworth, Gwendolyn Brooks, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Lorraine Hansberry, Virginia Woolf, Emily Dickinson, Langston Hughes, Buddhism, and the Beat poets.

She distinguished herself at Stanford with a degree in English Literature in 1974. She then furthered her academic credentials with a master’s degree in English Literature from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1976 and a doctorate in English Literature from the University of California at Santa Cruz in 1983. Her doctoral thesis was on Toni Morrison.

Becoming bell hooks

In the late 1970s in Northern California, hooks began to write and publish poetry and defined herself as a “cultural worker on the left.”

She began to use the pen name bell hooks. The name was chosen in honor of her maternal great-grandmother, Bell Blair Hooks. The lowercase spelling signified for the reader to pay attention to the substance of the book and not the writer.

Beginning in 1976, hooks began her professorial career teaching Ethnic studies and English Literature at the University of Southern California. hooks had an extraordinary career as a university professor.

After teaching at the University of Southern California, hooks taught at Stanford University, Yale University, Oberlin College in Ohio, and the City College of New York. In 2014 she became the Distinguished Professor in Residence Berea College near Lexington, Kentucky.

“As long as women are using class or race power to dominate other women, feminist sisterhood cannot be fully realized.” (from Feminism is for Everybody by bell hooks, 2000)

. . . . . . . . . .

bell hooks in 2009

. . . . . . . . . .

In 1981, the nonfiction book she began during her undergraduate days at Stanford, was completed and published. Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism remains a landmark book of progressive ideas that seem commonplace now: the idea of recognizing and reconciling how the historical intersections of race, gender, and feminism are inextricably intertwined and how these factors have inhibited our roles in the present time.

hooks was referring to the reluctance of many Black women to form an alliance with a movement that had been alienated from: the leaders of the early Women’s movement were invariably white, were disinclined to mention Gay and Lesbian Rights, and were dismissive of the experiences of poorer women and women of color.

Ain’t I a Woman? has become a classic: hooks examines the history of slavery in the United States and the continuing dehumanization of Black women. It critiques the revolutionary politics that have risen against white supremacy.

“A devaluation of Black womanhood occurred as a result of the sexual exploitation of Black women during slavery that has not altered in the course of hundreds of years.” (bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman by bell hooks, 1981)

The “oppositional gaze is another of hooks’ most prominent analyses. In 1992 hooks published a collection of essays Black Looks: Race and Representation that critically looked at the significance and hierarchies of power structures by the way human beings simply look at one another.

In the days of American slavery, slaves were mercilessly beaten if their white slave owners thought they had dared to even look at them. The “oppositional gaze” has become one tool to challenge the historic power dynamic between the races. Personal agency and dignity are attained when a Black man or Black woman meet and hold the gaze of their oppressors.

. . . . . . . . . .

bell hooks page on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

“Everywhere I go, people want to feel more connected. They want to feel more connected to their neighbors. They want to feel more connected to the world. And when we learn that through love we can have that connection, we can see the stranger as ourselves. And I think that it would be absolutely fantastic to have that sense of ‘Let’s return to kind of a utopian focus on love, not unlike the sort of hippie focus on love.’

Because I always say to people, you know, the 60’s focus on love had its stupid sentimental dimensions, but then it had these life-transforming dimensions … I tell this to young people, you know, that we can love in a deep and profound way that transforms the political world in which we live in.” (from a 2000 NPR interview)

The comments above are from an interview hooks gave in 2000 on her recently published book, All About Love: New Visions. All About Love has become a classic book on the varying natures of love: ideas on how to reverse our cultural training and become more open to giving and receiving love.

hooks defines the aspects of love: affection, respect, recognition, commitment, trust, care, and open and honest communication. However, the aspects of customary and accepted aspects of love that stem from historic gender stereotypes i.e., domination, control, ego, and aggression, remain in place. Love cannot survive in a power struggle. Love is a verb, not a noun: how we act and carry ourselves through the world is always more lasting, more beautiful and profound, when we recognize that love is the core of ourselves.

All About Love has become another bell hooks classic. It is the book she felt she needed to write — a book to recommend to men when she was asked about love.

bell hooks’ legacy

The legions of bell hooks readers were invariably saddened to hear of her passing at an age that is considered far too young. bell hooks gave the world an influential and monumental legacy that is timeless, altering the way people view themselves and their place in society for generations.

bell hooks wanted her work to be about healing: she has more than accomplished that goal. It is hooks’ perception of herself that she shared with the Buddhist magazine, Tricycle in 1992 that has become encoded within myself:

“If I were really asked to define myself, I wouldn’t start with race; I wouldn’t start with gender; I wouldn’t start with feminism. I would start with stripping down to what fundamentally informs my life, which is that I’m a seeker on the path. I think of feminism, and I think of anti-act struggles as part of it. But where I stand spiritually is, steadfastly, on a path about love.”

bell hooks’ accomplishments are too numerous to list. Here is her filmography; list of awards; and of course, her numerous published books.

Contributed by Nancy Snyder, who writes about women writers and labor women. After working for the City and County of San Francisco for thirty years, she is now learning everything about Henry David Thoreau in Los Angeles.

More about bell hooks & sources Trailblazing feminist author, critic and activist bell hooks has died at 69 bell hooks, Pathbreaking Black Feminist, Dies at 69 Five bell hooks Quotes To Carry With You … What bell hooks had to say about the state of feminism in 1999 bell hooks Will Always be a Foundational Force in Black Feminist Thought Poets.org The Revolutionary Writing of bell hooks Reader discussion of bell hooks’ books on Goodreads Wikipedia. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post bell hooks, Poet, Essayist, & Public Intellectual appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 14, 2022

Enigmatic Recluse or Sheltered Genius? A Tribute to Emily Dickinson

While scrolling through social media, it’s not usual for me to stop because a word or words caught my attention, and I simply had to go back and read the poem that caught my eye. More often than not, it turned out to be one of Emily Dickinson’s poems.

They’re light in the sense that she tended to use simple, everyday words, and often sparingly; yet, the images spring out from them to grab hold of one’s imagination. Or her deep concepts compressed into a few lines oblige one to delve deeper into her poems.

Her verses aren’t pretentious, though she was as well-read as any man of her era. Yet, it seems she didn’t choose grandiose words to impress anyone, especially as most of her poems went unpublished during her lifetime.

. . . . . . . . .

White Quill

Paddling for meanings were critics’ boats.

Hero, or champion, for rebels, and misfits?

Decriers? Supporters? There were wide rifts.

Her words used in world in countless quotes.

Water-shed poet, was worthy; of note.

She died thinking was wasted rare gift.

Yet, on gold spirals her name’s been writ.

A thousand critiques her verse set afloat.

Does mystical sub-text peers from beneath?

With the widest palette, so finely she drew.

Colours abound in wisdom’s white sheath.

Fresh breezes, soft chills, a green so blue,

Broad issues, sweeping scenes, minute details,

For centuries they’ll uncover more veils.

(by Sultana Raza, inspired by Emily Dickinson)

. . . . . . . . .

More about Emily Dickinson

. . . . . . . . .

My path crossed with Emily Dickinson’s verse when I was a teenager growing up in India, and I must confess that I wasn’t exactly taken in by her words. Perhaps because at that time we had to read her poems related to death and mortality at school, which aren’t the main pre-occupations of most teenagers.

Somehow, an image of an aging lady with one foot in the grave formed in my mind. One of my mentors tried to get me into her poems, but at that time I couldn’t understand why she used to admire Dickinson’s lines so much. On the other hand, I could understand Sylvia Plath’s works with frightening ease. Her words talked to me much more than those of Dickinson.

While I still appreciate Plath’s poems, my admiration for Dickinson has grown by leaps and bounds. It would be impossible to outline all the facets of her poems, since they’re so varied and deep at the same time. It’s amazing how much she could write about the vast canvas of life and beyond with so few words, while ensconced in her room.

Perhaps it’s ironic that someone so reclusive, who had traveled very little beyond her own State of Massachusetts could know so much about the evolution of humanity. Possibly, some writers and artists need to be outsiders to be able to observe all the layers of society critically from afar.

Are all women social animals?

Although plenty of authors or poets loved to be in the thick of things, even in the limelight, which helped to build their reputation. In stark contrast to Emily Dickinson, Colette (1873 –1954) preferred being on stage to scratching with her pen on an obstinate sheet of paper in an isolated room.

For another example, Edith Wharton (1862 – 1937) came into the world about thirty-two years after Emily and was able to distill her experiences of socializing in the upper-class circles of New York and travels in Europe in her insightful novels. However, Wharton wasn’t exactly a typical socialite. Both Wharton and Dickinson used to write in their bedrooms, except that the former wrote while sitting in bed in the morning. She used to drop her finished sheets of paper to the floor, which an employee would pick up and assemble later.

Jane Austen (1775 – 1817) didn’t mingle all that much in society, especially when she was obliged to reside in Bath with her family. Though her keen wit and pithy observations were present from an early age, possibly she didn’t find inane rounds of socializing to be quite as interesting as it was for most young girls, unless they provided fodder for her novels.

The Brontë sisters led an even more secluded life at Haworth than Jane Austen, except for their forays in Brussels and in other households in England to work as governesses. Their novels focus on a slice of society different from that in Austen’s novels. At the same time, their works are often praised for their intensity.

Apparently, Emily Dickinson was interested in Charlotte Brontë’s (1816 – 1855) biography, according to biographer Alfred Habegger. It seems to denote that Emily was aware of, or sensible to the role a female writer could play in society.

She could have published using a male pseudonym, as was the case of the Brontë sisters who initially published under the names of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. Or she could have followed the example of George Eliot (1819 – 1880), or the French writer George Sand (1804 –1876).

Reticence

Why she chose to publish so little during her lifetime is one of the enduring mysteries surrounding Emily Dickinson. Only about ten or eleven poems managed to trickle onto the pages of newspapers while she was still wielding her plume. Unlike her, another genius, John Keats, died regretting that his works would never become well known.

Though Keats didn’t formulate the phrase inscribed on his grave, “Here lies One Whose Name was writ on Water,” it encapsulates his thoughts to a certain degree. Both Keats and Emily Dickinson found nature to be a great source of inspiration and penned numerous poems exploring it mysteries.

Through a bird’s eye

Curiously enough, Dickinson’s poem, “A Bird, came down the Walk –” is reminiscent of Keats’s letter #XXII, to Benjamin Bailey. written on November 22, 1817, where he wrote: “I scarcely remember counting upon any Happiness—I look not for it if it be not in the present hour, — nothing startles me beyond the moment. The Setting Sun will always set me to rights, or if a Sparrow come before my Window, I take part in its existence and pick about the gravel.”

Dickinson seems to be seeing the world through the existence of a bird in her poem as well:

A Bird, came down the Walk –

He did not know I saw –

He bit an Angle Worm in halves

And ate the fellow, raw,

And then, he drank a Dew

From a convenient Grass –

And then hopped sidewise to the Wall

To let a Beetle pass –

He glanced with rapid eyes,

That hurried all abroad –

They looked like frightened Beads, I thought,

He stirred his Velvet Head. –

Like one in danger, Cautious,

I offered him a Crumb,

And he unrolled his feathers,

And rowed him softer Home –

Than Oars divide the Ocean,

Too silver for a seam,

Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon,

Leap, plashless as they swim.

Both of these poets seem to become part of another sentient being, the better to live in its reality or experience existence through its mind, or lens. This merging of the self with an organic entity of nature is part of a mystical phenomena. It also represents a cutting off from human reality, an escape from the humdrum business of daily routines, or a foray into another dimension.

Dickinson may have locked herself in her room towards the end of her life, but the entire world was spilling out from her quill onto her pages. Keats did not travel to Italy or Greece when he was still composing poetry, but his explorations of antiquity through his surreal forays into dreamscapes could lead the readers to believe he knew of these places firsthand.

Dickinson may have had a limited social circle, yet her poems appeal to all sorts of people. Both these poets died thinking their work would be read by a limited number of people, yet their work grew deep roots and flourished all over the world. While Keats was quite ambitious, it’s not known how Dickinson intended for her poems to be treated after her demise.

Ensconced genius

It seems that Dickinson was writing as a way of self-expression. It’s rare for a writer of such skill to practice their craft without keeping an eye on potential readers. Many writers do scribble away for fame, riches, or glory.

After Oscar Wilde was exiled to France, he couldn’t come to terms with his notoriety and relative obscurity since he had enjoyed the limelight for many years in England and America. His literary output dwindled and his greatest works are those created while he was hobnobbing with well-known names in London. His most famous (though unverified) quote is “I have nothing to declare but my genius,” when questioned by a customs officer in New York in 1882.

Pure outpourings

In stark contrast, Emily Dickinson kept her genius hidden even from her own family for her entire life. It’s a pity that she didn’t feel that her immediate social circle would be receptive enough to share her oeuvres with them. But since she didn’t have any pressure from her peers, critics, or even friends, she was free to explore and experiment.

Though she may not have experimented consciously, she wrote what came naturally to her. Keats said in his letter (XXXIX) to John Taylor written on 27 February 1818, “Another axiom — That if poetry comes not as naturally as the leaves to a tree, it had better not come at all,” yet he revised his poems many times before sending them to friends or publishers.

It seems that Dickinson didn’t do a lot of revisions to her poems. Perhaps the sheer, staggering number of them— about 1800 — wouldn’t have allowed for extensive revisions. She composed about 800 poems in her most productive period from 1861 to 1865.

There’s a natural flow in her poems, punctuated by long dashes, giving the impression that they were written impulsively, or unrestrainedly, as opposed to deliberate crafting, which could have resulted in an interruption of that flow.

Her output can be seen as “pure,” since her motivations don’t seem to be affected by recognition from her peers, critics, the public, or monetary gain. She didn’t need to please anyone, nor was she afraid of any critical reception. In that sense, her poems can be seen as a rare expression of the authentic self.

Self-seclusion

Dickinson possessed a self that seemed to be detached from worldly concerns, while still living with her family in a civilized (and religious) town with intellectual leanings. However, she must have had some inkling of her own genius.

Her seclusion can also be interpreted in symbolic terms: she was conscious of the fact that she was different from the others. Her visions and mystical journeys set her apart, as did her acute observations about humanity, nature, and mortality. Some of her poems seem to be forays and explorations of her unconscious self, and inquiries into the mysteries of the universe.

The ties that bind

According to biographer Alfred Habegger, since her father discouraged women from expressing themselves in public, that may have curbed any impulse to publish, or at least share, her poems. However, even after he passed away in 1874, she still didn’t take any initiative to see them in print.

It’s ironic that her father and brother are now known in the world because they were her relatives, and not the other way around, though at the time, the men in the family were supposed to be the most important. Often, childless women were supposed to take care of their elderly parents, and even now, unless an artist/writer can make a living from their work, it’s not taken seriously by those around them.

It’s a pity that attitudes haven’t changed all that much. Few women are lucky to be supported by others at the beginning of their creative journey.

. . . . . . . . .

10 Well-Loved Poems by Emily Dickinson

. . . . . . . . .

Could it be that Dickinson didn’t think the world was ready to receive her poems? This is reminiscent of the steps taken by Swedish artist Hilma Af Klint (1862 – 1944), who packed away her paintings because she believed that the Swedish society of her time wasn’t ready for her works.

Both Dickinson and Klint portray mystical ideas in their works, albeit in different mediums and ways. Klint was one of the first artists in the Western world to depict abstract, often geometrical forms as a way to channel spiritual concepts gleaned from her association with the Theosophical Society (a spiritual movement inspired by Eastern philosophy).

Though Dickinson grew distant from organized religion, however, her deeply spiritual and mystical side comes across in numerous poems, such as “You’ll know it — as you know ’tis Noon —,” or “One Blessing had I than the rest,” “As Watchers hang upon the East,” “A Tongue — to tell Him I am true!”

Eastern threads

In her vast body of works, some of her verses seem to express Sufi ideas in the sense that the poem or the lyrics can be interpreted on at least two levels. For example, in “Fitter to see Him, I may be,” the poet could be referring to another mortal. At a deeper level, the person referred to could be the Creator of the universe. “I’ve nothing else — to bring, You know —” and “I think to Live — may be a Bliss” could be about the Creator as well.

Her Master poems, such as “The Master / He fumbles at your spirit” can be interpreted via the Sufi philosophy of expressing love for the Creator through romantic, mystical poetry. Rumi, Hafez, Sa’adi, Kabir, or Hazrat Inayat Khan are some well-known Sufi poets. A comparison of famous Sufi poems with those Dickinson’s verses would be an onerous research project yet would yield delightful and fruitful results.

While Rumi and Omar Khayyam are the best-known Sufi poets in the West, Sufi poetry has been written in many languages, including Persian, Arabic, Urdu, and Punjabi. Its appeal is universal. The fact that Dickinson’s works can be compared to so many schools of thought is a testimony to the pervasiveness of her ideas across cultures.

A vast universe waiting to be explored

While Dickinson collected some of her poems into small hand-sewn books she called fascicles, the poems written later in life did not get this special treatment. Fortunately, she didn’t destroy her compositions; she simply left them hidden in her room.

That seemed to say that she’d given these poems to the world — now, what was the world going to do with them? Though it took a while for critical reception to warm up to her unconventional style, critics in the 1920s finally caught up with her avant-garde, experimental structures.

No matter how many research papers or books are published about Dickinson’s work, there’s still a vast universe waiting to be explored in her hand-sewn fascicles. More gems are waiting to surface, as readers are still grappling with her enormous output. For example, if a researcher started following her treatment on the subject of birds in her poems, they would need to cover a lot of ground.

The pages on which Dickinson wrote could be compared to feathers that allowed her to fly. She painted each sheet with extraordinary ideas and images; examining each one in detail would require many lifetimes. Her work invites as wide a readership as possible, as it lends itself to multiple interpretations. No wonder she’s soared above so many poets, not only from her lifetime, but also ours.

Hilma Af Klint passed away in 1944, leaving instructions that the boxes containing her paintings should be opened twenty years after her death. It turned out she’d been a prolific painter and had left nearly 1,200 paintings as her legacy to an unappreciative world. It took another twenty years before her paintings gained some traction with an international audience.

Both Emily Dickinson and Hilma Af Klint were hugely productive, yet had to be secretive about their respective oeuvres for various reasons. Their works had mystical overtones, and both turned out to be ahead of their times.

While they can teach us innumerable concepts, perhaps one thing we can learn from them is to indulge in creative expression regardless of the circumstances, or the potential reception of the work. What would the world have been like if Emily lived for many more fruitful years, rather than passing away at age fifty-five?

Contributed by Sultana Raza: Of Indian origin, Sultana Raza’s creative non-fiction has appeared in countercurrents.org, Litro, Gnarled Oak, Kashmir Times, and A Beautiful Space. Her 100+ articles (on art, theatre, film, and humanitarian issues) have appeared in English and French. An independent scholar, Sultana Raza has presented many papers related to Romanticism (Keats) and Fantasy (Tolkien & GRR Martin) in international conferences.

Her poems have appeared in numerous journals, including Columbia Journal, The New Verse News, London Grip, Classical Poetry Society, spillwords, Poetry24, Dissident Voice, and The Peacock Journal. Her fiction has received an Honorable Mention in Glimmer Train Review (USA), and has been published in Coldnoon Journal, Szirine, apertura, Entropy, and ensemble (in French). She has read her fiction/poems in India, Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, England, Ireland, the U.S.

The post Enigmatic Recluse or Sheltered Genius? A Tribute to Emily Dickinson appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 10, 2022

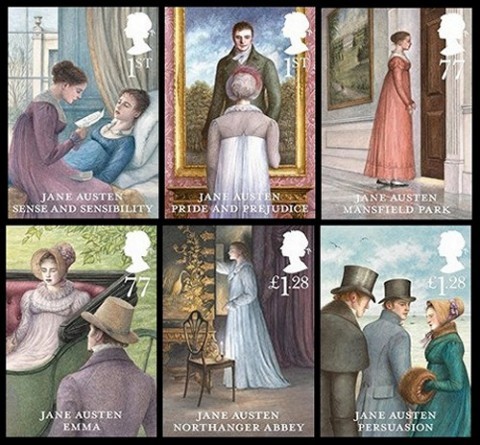

Analysis and plot summary of Persuasion by Jane Austen

Jane Austen by Sarah Fanny Malden (1889) offers a detailed 19th-century view of Jane Austen’s life and works. The following analysis and plot summary of Persuasion focuses on the novel that many have judged to be Austen’s most mature and accomplished work.

Persuasion, the last novel Austen wrote, and Northanger Abbey, her first completed novel, were both published six months after her death in 1817.

Mrs. Malden said of her sources, “The writer wishes to express her obligations to Lord Brabourne and Mr. C. Austen Leigh for their kind permission to make use of the Memoir and Letters of their gifted relative, which have been her principal authorities for this work.”

The 1889 publication of Malden’s Jane Austen was part of an Eminent Women series published by W.H. Allen & Co., London. The following excerpt is in the public domain.

Arguably the greatest of Jane Austen’s works

In approaching Persuasion, we have to deal with the last, and, in my opinion, the greatest of Jane Austen’s works, for though Emma usually holds the first place in her writings, and although there are unquestionably one or two weak points in Persuasion from which Emma is free, I cannot but heartily concur with Dr. Whewell that “Persuasion is the most beautiful of all Jane Austen’s stories.”

It is, I think, the only one of those stories to which the epithet “beautiful” can appropriately be given; not that it differs in style from her earlier works or contains any intentional sentiment beyond what all her stories have, but it possesses throughout a sort of tender, pathetic grace that appears nowhere else.

A reviewer who criticized Mansfield Park in 1821 asserted that the details of Fanny Price’s attachment could scarcely have come from any writer but a woman who had herself lived through such an attachment.

It is unnecessary and, as has been seen, would probably be incorrect, to say that Jane Austen ever described love from any experience except what her genius gave her, but I think Persuasion would be far stronger testimony to her having once loved than Mansfield Park is.

Fanny Price’s apparently hopeless attachment is followed through its course with the affectionate but critical interest of one who regards a touching phase of human nature. Persuasion is in the tone of a woman who looks back upon her own early romance with sorrowful tenderness and permits to her imaginary story the happy finale which she had not experienced herself.

The heroine has a sort of subdued charm about her; she makes no brilliant speeches, and exhibits no special gifts, but from first to last, we feel that with Anne Elliot we are in the presence of a high-bred, gracious, charming woman, and nothing better could be said of Captain Wentworth than that he is worthy of her.

Jane Austen was herself conscious of having evolved a superior heroine in her last novel, for in 1816 she wrote to her niece, Fanny Knight: “I have a something ready for publication which may, perhaps, appear about a twelvemonth hence You may, perhaps, like the heroine, as she is almost too good for me.”

From first to last the story may be said to strike a minor key, for it is no longer the bright picture of young love which Jane Austen gave us in her other novels; it is the coming together of sundered lovers after the difficulties and hindrances of eight years of separation, in which neither has ever been able to forget the other.

Introducing Anne Elliot

Anne Elliot, already well into her twenties, is the second of the three daughters of Sir Walter Elliot, of Kellynch Hall, Somersetshire. She has lost her mother early and has never had congenial society in her father or sisters. Sir Walter is an intensely conceited man, of an ancient family, very handsome, even in middle life, and inordinately vain both of his birth and his looks.

His eldest daughter, Elizabeth, is himself over again; and the youngest daughter, Mary, is a common-place, self-engrossed woman. There is no son, and the title and estate will, at Sir Walter’s death, devolve upon a cousin whom Elizabeth always intended to marry, but who, having chosen to make a mésalliance for the sake of money, has been ignored by the Kellynch Hall family ever since, although he has lately become a widower.

From such a father and such sisters, it is clear that Anne, cultivated, thoughtful, and refined, can gain no pleasant companionship, and, in fact, the only real companion she has is a very intimate friend of her mother who has settled near them.

Lady Russell is sensible, right-minded, and a little prosaic; she is not Anne’s equal intellectually, but she loves her for her mother’s sake and for her own; and Anne is thankful to be loved at all.

Enter Captain Wentworth

Frederick Wentworth makes the acquaintance of this attractive and neglected girl when she is nineteen, and in the full bloom of her beauty. He is a few years older, a young naval officer, full of spirit, energy, and brightness.

The natural consequences ensue, and for a short time the young people are rapturously happy; but both Sir Walter Elliot and Lady Russell regard the engagement with strong disfavor. He considers any untitled marriage as beneath his daughter’s acceptance, whilst Lady Russell objects to a long engagement, dislikes the uncertainty of the naval profession, and does not believe that Captain Wentworth will ever make a fortune. Thus the connection is severed.

An eight-year separation

A somewhat unexpected, yet—as in all Jane Austen’s books—apparently natural chain of circumstances brings about a meeting between the two former lovers after eight years of separation. Sir Walter Elliot, after his wife’s death, gets gradually deeper and deeper into debt.

Mr. Shepherd, Sir Walter’s confidential attorney, and Lady Russell are called upon to advise in the dilemma; and as neither Sir Walter nor Elizabeth will hear of any retrenchment which will affect their luxuries in any way, there is nothing for it but to let Kellynch Hall.

A tenant soon offers for it. Admiral Croft, and Anne remembers with a thrill at her heart that Mrs. Croft is Frederick Wentworth’s sister. Still, there is no particular likelihood of her seeing him, as Sir Walter and Elizabeth intend to go to Bath, and Anne is earnestly desirous of avoiding a meeting with her former lover.

But fate is too strong for her. Her youngest sister Mary is married to Charles Musgrove, the eldest son of a man of property living at Uppercross, about three miles from Kellynch.

Elizabeth is delighted to get rid of Anne, for she has lately struck up a violent friendship with a widowed daughter of Mr. Shepherd, a young Mrs. Clay, who is enchanted to act as hanger-on to Miss Elliot at Bath. Anne is glad to avoid Bath, which she dislikes, and to be of use to anyone. Her father, sister, and Mrs. Clay depart for Bath, and Anne is installed at the Musgroves for the summer.

A capital picture follows, in Jane Austen’s most characteristic style, of the relations between Charles Musgrove and his family, who live about a quarter of a mile from them.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Persuasion by Jane Austen

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Crofts take possession of Kellynch Hall; and Captain Wentworth comes there to visit his sister. Mr. Musgrove calls upon him at Kellynch; he is invited to dine at Uppercross, and Anne can no longer avoid meeting him. None of the Musgroves know anything of the former passages between her and Captain Wentworth, so no one thinks of screening her, and Anne can only struggle to keep her feelings to herself.

Whether Captain Wentworth remembers the past as she does, she has no means of discovering, but she has soon reason to believe that he is in no way anxious to recall it.

She keeps herself in the background, prepared to hear at any moment of her former lover being now engaged to a Miss Musgrove; and the struggle in her mind is all the more severe because, in the first place, Frederick Wentworth has deteriorated neither in mind nor person since the days of their early attachment. And, in the second place, she cannot help continually how much better she can understand and appreciate him than either Henrietta or Louisa Musgrove can.

Anne is yet unforgiven

He, on his side, is not at all anxious to renew the feeling which he believes he has completely conquered. He has not forgiven Anne for her desertion of him years ago; and though he intends to marry as soon as he can find a wife to his liking, he has no idea that that wife will be Anne Elliot.

Nothing in the story is better than his attempt to persuade himself into caring for one of the young ladies with whom he is thrown into contact; and the gradual way in which he finds himself turning, as of old, to Anne for the companionship and appreciation with which she only can supply him, while he is quite unconscious of the feeling slowly working in him.

Eventually Anne departs for Bath, and, as her absence leaves an insupportable blank for him, Captain Wentworth sets off as well. Anne has been there with her father and sister for some time before his arrival, and has found an ardent admirer in the cousin, William Elliot, who is the heir to her father’s baronetcy. Of course, the marriage would be an extremely suitable one for both parties, and Lady Russell, who is also at Bath, is delighted at the possibility of it and cannot resist speaking of it to Anne.

“I am no match-maker, as you well know,” said Lady Russell, “being much too well aware of the uncertainty of all human events and calculations. I only mean that if Mr. Elliot should some time hence pay his addresses to you, and if you should be disposed to accept him, I think there would be every possibility of your being happy together. A most suitable connection everybody must consider it, but I think it might be a very happy one.”

“Mr. Elliot is an exceedingly agreeable man, and, in many respects, I think highly of him,” said Anne, “but we should not suit.”

Anne herself cannot help believing, after Captain Wentworth has been in Bath for a short time, that she is his object there; but she is afraid to trust to this idea and is almost maddened by the quiet but unmistakable way in which Mr. Elliot monopolizes her. The moment of explanation comes at last and is one of the best and most touching scenes in all Jane Austen’s works.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You may enjoy: Jane Austen-inspired novels by Sonali Dev

. . . . . . . . . . .

Anne, going one day to call on Mrs. Musgrove, finds Captains Wentworth and Harville both in the room. The former goes to a writing-table to write letters, and the latter begins a conversation with Anne which drifts into a debate on the strength of feeling in men as against that of women. Captain Harville defends his own sex warmly.

“Ah,” cried Captain Harville, in a tone of strong feeling, “if I could but make you comprehend what a man suffers when he takes a last look at his wife and children and watches the boat that he has sent them off in, as long as it is in sight, and then turns away and says, “God knows whether we shall ever meet again!” …

“Oh,” cried Anne, eagerly, “I hope I do justice to all that is felt by you, and by those who resemble you. God forbid that I should undervalue the warm and faithful feelings of any of my fellow-creatures! I should deserve utter contempt if I dared to suppose that true attachment and constancy were known only by women. No, I believe you capable of everything great and good in your married lives. I believe you equal to every important exertion and to every domestic forbearance so long as—if I may be allowed the expression—so long as you have an object. I mean while the woman you love lives, and lives for you. All the privilege I claim for my own sex (it is not a very enviable one: you need not covet it) is that of loving longest when existence or when hope is gone.”

She could not immediately have uttered another sentence: her heart was too full, her breath too much oppressed … Their attention was called towards the others.

Captain Wentworth then drew out the letter he had been writing and “placed it before Anne with eyes of glowing entreaty fixed on her, and, hastily collecting his gloves, was again out of the room, almost before Mrs. Musgrove was aware of his being in it: the work of an instant.”

Anne manages to read the letter in the next five minutes, but the result is to upset her so much that the Musgroves all fancy her ill, and, instead of letting her go home quietly by herself to realize her own “overpowering happiness,” as Jane Austen calls it, Charles Musgrove insists on accompanying her. Fortunately, when halfway home, they encounter Captain Wentworth; and Charles, being anxious to keep an engagement elsewhere, puts Anne under his escort.

In half a minute Charles was at the bottom of Union Street again, and the other two proceeding together; and soon words enough had passed between them to decide their direction towards the comparatively quiet and retired gravel walk, where the power of conversation would make the present hour a blessing indeed, and prepare it for all the immortality which the happiest recollections of their own future lives could bestow.

There they exchanged again those feelings and those promises which had once before seemed to secure everything, but which had been followed by so many many years of division and estrangement; and there, as they slowly paced the gradual ascent, heedless of every group around them, seeing neither sauntering politicians, bustling housekeepers, flirting girls, nor nursery-maids and children, they could indulge in those retrospections and acknowledgments, and especially in those explanations of what had directly preceded the present moment, which were so poignant and so ceaseless in interest. All the little variations of the last week were gone through; and of yesterday and to-day there could scarcely be an end …

The evening came, the drawing-rooms were lighted up, the company assembled. It was but a card-party, it was but a mixture of those who had never met before and those who met too often: a commonplace business, too numerous for intimacy, too small for variety; but Anne had never found an evening shorter.

Glowing and lovely in sensibility and happiness, and more generally admired than she thought about or cared for, she had cheerful or forbearing feelings for every creature around her.

With the Musgroves there was the happy chat of perfect ease; with Captain Harville, the kind-hearted intercourse of brother and sister; with Lady Russell, attempts at conversation which a delicious consciousness cut short; with Admiral and Mrs. Croft, everything of peculiar cordiality and fervent interest, which the same consciousness sought to conceal; and with Captain Wentworth, some moments of communication continually occurring, and always the hope of more, and always the knowledge of his being there.

All ends well for dear Anne Elliot

Dear, charming Anne Elliot! We rejoice to feel that we are leaving her in the midst of such a tender, radiant Indian summer of happiness; and we safely predict a married life at blessedness for her and her husband; but even in this crowning hour of their felicity, there is the same tinge of pathos visible as throughout the book.

It does not seem intentional; it is rather as though the writer could no longer treat her subject with the bright gaiety of former days, and it is not wonderful that a dying woman could not.

Persuasion is the swan song of Jane Austen’s authorship, and, true to its character, the saddest and sweetest of her works. When she finished it, only a few months before her death, she had in fact laid down the pen for ever; and doubtless it was the consciousness of this which shaded the story to a more autumnal tone than anything she had yet written.

We could not wish it otherwise, for the group of novels would have been incomplete without some such story of comparatively late happiness.

In Northanger Abbey and Sense and Sensibility we have the brilliant, rather thoughtless happiness of early youth; in Mansfield Park, Emma, and Pride and Prejudice the love-story goes on in the usual way, though somewhat slowly, through the usual period of life; in Persuasion the attachment of early youth is abruptly checked, and only comes to its full perfection after eight years of separation.

The cycle is complete, and it seems as though Jane Austen would have been compelled to take some fresh departure, had she lived to write more. We regret that she did not, but we rejoice that her life was spared long enough to give us the immortal group we now possess, and we must all echo the already quoted lament of Sir Walter Scott, “What a pity such a gifted creature died so early.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Film versions of Persuasion

2022 – A Netflix production

2007 made for television film

1997 film (available to stream on Amazon*)

More about Persuasion by Jane Austen

Persuasion on Jane Austen Society of North America “I am half agony, half hope” Reader discussion on Goodreads Seeing the Light at Last (on re-reading Persuasion) Jane Austen’s Persuasion: A Study in Literary History Jane Austen’s Greatest Novel Turns 200. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Analysis and plot summary of Persuasion by Jane Austen appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 8, 2022

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen—plot summary and analysis

The first novel intended for publication by Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey was originally titled Susan. Completed in 1803, it wasn’t published until 1817, the year of the author’s death. This coming-of-age novel’s heroine, Catherine Morland, at first young and rather naïve, learns the ways of the world in the course of the narrative.

Set in Bath, England, the fashionable resort city where the Austens lived for a time, Jane Austen critiques young women who put too much stock in appearances, wealth, and social acceptance. Catherine values happiness but not at the cost of compromising one’s values and morals.

A brief synopsis from a 1995 edition

From the 1995 Wordsworth Limited edition of Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen: Northanger Abbey is the most joyous of Jane Austen’s novels and is an early work conceived as a pastiche of the melodramatic excesses of the Gothic novel (a type of romance popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries).

Jane Austen was temperamentally incapable of keeping her youthful sense of fun from bubbling over, and the result makes the social and romantic trials of young heroine, Catherine Morland, a delight to follow.

The story is set in fashionable Bath, where Catherine is taken to come out is society by her neighbors Mr. and Mrs. Allen. There she meets a young clergyman, Henry Tilney and his sister, the children of the eccentric General Tilney who resides at Northanger Abbey in nearby Gloucestershire.

Having been invited to Northanger Abbey by the General on mistaken grounds that she is extremely well-off, there follows the series of hilarious misunderstandings and the Gothic suspicions which are the essence of the book.

Northanger Abbey was actually the first novel that Jane Austen completed with the hopes of publication, in 1803. It was first titled Susan and she sold the copyright to a London publisher for a pittance.

The publisher held on to it for years without ever printing it. It was tied up until 1816 when Jane’s brother Henry managed to buy it back, after much dispute. Jane spent some time revising the original, renaming her heroine Catherine, but by the time it was published in 1817, she died. That year, another of her novels, Persuasion, was published as well.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

. . . . . . . . . .

Jane Austen by Sarah Fanny Malden (1889) offers an excellent 19th-century view of Jane Austen’s works. The following analysis and plot summary of Pride and Prejudice (1813) focuses on this beloved novel, which was Jane Austen‘s second to be published. It followed Sense and Sensibility, published two years earlier.

Mrs. Malden said of her sources, “The writer wishes to express her obligations to Lord Brabourne and Mr. C. Austen Leigh for their kind permission to make use of the Memoir and Letters of their gifted relative, which have been her principal authorities for this work.”

The 1889 publication of Malden’s Jane Austen was part of an Eminent Women series published by W.H. Allen & Co., London. The following excerpt is in the public domain:

Unlike her other novels

Although not published until after her death, Northanger Abbey was one of Jane Austen’s earliest works; and the scheme of it is so unlike her other novels that it may be said to occupy a place by itself.

It is so complete and so clever a parody of many of the novels of her day, that it can hardly be appreciated by those who do not recognize the originals of its situations and characters or understand the kind of sensational writing in which Samuel Richardson and Henry Fielding were leaders, followed at a considerable distance by a host of inferior writers.

Seventeen-year-old Catherine Morland is the heroine of Northanger Abbey. Her début is intentionally made unsuccessful to contrast with the outbursts of admiration that greeted Fanny Burney’s Evelina and Cecilia when they first appeared in public.

Enter Henry Tilney and the Thorpes

Soon Catherine meets her fate in the person of Henry Tilney, to whom she is introduced at a ball, and who is just the sort of brilliant, clever, cultivated young man to attract a girl of her age.

As is natural under the circumstances, she is much struck with him, and very ready to improve the acquaintance, but she sees nothing more of Henry for some time.

Meanwhile the Thorpes appear upon the scene. Mrs. Thorpe and Mrs. Allen were former school-friends, and Mrs. Thorpe’s eldest daughter, Isabella, professes a violent affection at first sight for Catherine, chiefly in hopes of renewing an old flirtation with Catherine’s brother James, who may come to Bath.

Catherine, quite unsuspicious of any double motive, is much flattered by Isabella’s warmth, and, being dazzled by her showy beauty, does not perceive her shallowness, vulgarity, and insincerity. A warm schoolgirl friendship is set up between them, in which Catherine’s simplicity and straightforwardness contrast much to her advantage with Isabella’s insufferably bad taste.

The acquaintance with Isabella Thorpe proves important for Catherine in more ways than one. James Morland comes to Bath, and—having, of course, light eyes and a sallow complexion—is very soon Isabella’s declared and accepted lover.

John Thorpe comes too; and having fallen in love—or supposing he has—with Catherine, she receives her first offer from him, though being quite unconscious of his admiration for her, which isn’t very intelligibly expressed, she doesn’t know, until later in the story, that he has offered himself. Last, but not least, Isabella introduces Catherine to the class of novels which are to influence her mind so powerfully.

Between these horrid novels and the society of Isabella Thorpe, Catherine is in danger of deterioration, but she is fortunately saved from any permanent ill effects.

An invitation to Northanger Abbey

Henry Tilney is in Bath with his father and sister; and General Tilney, under a mistaken impression of the amount of Catherine’s fortune, is quite willing to encourage his son’s dawning attachment for her. Elinor Tilney is charming, and Catherine has good taste enough to take greatly to her, and to be pleased and flattered by her notice.

Finally, to her unutterable delight, the Tilneys invite her to accompany them when they leave Bath. Their home is called Northanger Abbey; and Catherine, who has never seen an old house in her life, believes herself to be on the verge of similar adventures to those that befell her favorite heroines.

Henry Tilney discovers her expectations, and amuses himself with heightening them, having no idea that she will take his nonsense so seriously. The first sight of Northanger Abbey is disappointing to her, as it is modernized out of all picturesqueness or romance, and even her own room she finds very unlike the one by the description of which Henry had endeavored to alarm her.

Too influenced by gothic novels

Nevertheless, she has not been long in it, and is still occupied in dressing for the five o’clock dinner, when her eye suddenly fell on a large high chest, standing back in a deep recess on one side of the fireplace. The sight of it made her start; and, forgetting everything else, she stood gazing on it in motionless wonder while these thoughts crossed her:

“This is strange, indeed! I did not expect such a sight as this. An immense heavy chest! What can it hold? Why should it be placed here? Pushed back, too, as if meant to be out of sight! I will look into it; cost me what it may, I will look into it; and directly, too—by daylight. If I stay till evening, my candle may go out.”

She advanced, and examined it closely; it was of cedar, curiously inlaid with some darker wood, and raised about a foot from the ground on a carved stand of the same. The lock was silver, though tarnished from age; at each end were the imperfect remains of handles, also of silver, broken, perhaps prematurely, by some strange violence; and on the center of the lid was a mysterious cipher in the same metal.

Catherine has sense enough to be abashed at the perception of her own folly, but not quite enough to get immediately over the effects of being really in an abbey like one of Mrs. Radcliffe’s heroines; and that night her courage is again put to the test.

It is a very stormy night, quite “like what one reads about,” but Catherine, determined now to be brave, undresses very leisurely, and even resolves not to make up her fire. When daylight brought returning courage and cheerfulness, her first thought was for the manuscript:

… springing from her bed in the very moment of the maid’s going away, she eagerly collected every scattered sheet which had burst from the roll on its falling to the ground and flew back to enjoy the luxury of their perusal on her pillow.

She now plainly saw that she must not expect a manuscript of equal length with the generality of what she had shuddered over in books; for the roll, seeming to consist entirely of small, disjointed sheets, was altogether but of trifling size, and much less than she had supposed it to be at first.

Her greedy eyes glanced rapidly over a page. She started at its import. Could it be possible, or did not her senses play her false? An inventory of linen, in coarse and modern characters, seemed all that was before her! If the evidence of sight might be trusted, she held a washing-bill in her hand.

Instead of finding a manuscript revealing deep dark secrets about the Tilney family, all she finds are ordinary household accounts, receipts, and bills.

Another pointless flight of fancy

Now, her great anxiety now is to conceal her folly from Henry Tilney’s satirical observation, and for some time she succeeds; but her lively imagination leads her into another hallucination, from which she does not escape so easily.

She gathers from Miss Tilney that her mother had not been so fully valued by the General as she might have been, and thereupon jumps to three conclusions, first, that he had been unkind to his wife in her lifetime, secondly, that he had been in some way instrumental in causing her death, and, finally, as her fancy continues to run riot, that perhaps Mrs. Tilney was not really dead at all, but kept somewhere in close confinement by a cruel and tyrannical husband.

The successive stages by which this crowning point of absurd delusion is reached are very well worked out, and they culminate in intense anxiety on Catherine’s part to see Mrs. Tilney’s room, which, she hears, has been left exactly as it was at her death, and from which she thinks she may discover something; she scarcely knows what.

Miss Tilney is puzzled by her extreme desire to visit the room but is very willing to show it to her. The inopportune presence of the General, however, more than once prevents them; and Catherine, convinced that his interference is not accidental, determines to visit the important room by herself, and see what revelations it will make to her.

It was done; and Catherine found herself alone in the gallery before the clocks had ceased to strike. It was no time for thought; she hurried on, slipped with the least possible noise through the folding doors, and, without stopping to look or breathe, rushed forward to the one in question.

The lock yielded to her hand, and luckily with no sullen sound that could alarm a human being. On tiptoe she entered; the room was before her; but it was some minutes before she could advance another step.

She beheld what fixed her to the spot, and agitated every feature. She saw a large well-proportioned apartment, a handsome dimity bed, unoccupied, arranged with a housemaid’s care, a bright Bath stove, mahogany wardrobes, and neatly painted chairs, on which the warm beams of a western sun gaily poured through two sash-windows. Catherine had expected to have her feelings worked, and worked they were. Astonishment and doubt first seized them, and a shortly succeeding ray of common sense added some bitter emotions of shame …

Thereupon Henry Tilney presents himself, having returned a day before he is expected, and is much amazed at finding Catherine there by herself. She is unable wholly to conceal from him what her delusions had been, and she gets from him, in consequence, a half lover-like, half brotherly lecture, which makes her thoroughly ashamed of herself, and as she really is a nice girl, does her a world of good.

Now that her mind is cleared of all its strange delusions, she has time and opportunity to consider their origin, and her conclusions, are given us with some delightful touches.

Imaginary troubles end, real ones begin

Catherine’s imaginary troubles are at an end, but there are some very real ones in store for her. Her brother’s engagement with Isabella Thorpe is broken off through Isabella’s hoping to secure a better match for herself; and Catherine, who receives the news in a letter from James, feels his sorrow as if it were her own.

The affectionate sympathy of Henry and Eleanor has just restored her to some comfort, when a far greater blow falls. The young Tilneys have never been able to understand their father’s marked partiality for Catherine, being quite unaware that when in Bath he had received from John Thorpe a glowing account of her parents’ position and her future expectations.

Thorpe had at that time intended to marry her himself, and, as his sister was also on the eve of an engagement to her brother, his vanity had led him into telling the General a series of untruths, all tending to the glorification of the Morland family.

. . . . . . . . .

The Masterpiece adaptation of Northanger Abbey

to stream on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

General Tilney’s interventions