Nava Atlas's Blog, page 31

January 3, 2022

The Daring Fiction of Maude Hutchins

Maude Phelps McVeigh Hutchins (1899 –1991) was raised in an upper-class environment, born to wealthy parents in New York City. She was orphaned at a young age and brought up by her grandparents, prominent members Long Island society.

This introduction to Maude Hutchins’ creative life, first in the visual arts and then more predominantly as the author of fiction considered daring even by mid-twentieth-century standards, is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

A 1935 article about Hutchins (in her then role as a sculptor in Chicago) makes it clear just how aristocratic her family was. “Mrs. Hutchins’ mother was a Phelps, of a New England family that made their advent in Massachusetts in 1632. It was her Phelps grandparents who brought her up after her parents died.”

What upper class women could and couldn’t do

Women of Hutchins’ class had to contend with expectations as to what they could and couldn’t do, though being artistic wasn’t necessarily a problem. Critic Maxwell Geismar, in his 1962 introduction to Hutchins’ collection of stories The Elevator, called her “this country-bred, inherently ‘upper-class,’ and offbeat virtuoso (for Maude Hutchins is certainly that; while like most native aristocrats, she is profoundly democratic in her instincts).” Further:

It was nice for young ladies of fashion in her girlhood circles on Long Island to paint and draw. So Maude Phelps Hutchins had no traditional background of stern family objections thrown into her way of following her instincts to be an artist. Painting or drawing was one of the “accomplishments,” like playing the piano and doing needlework (as distinguished from sewing).

Her only problem when trying to be taken seriously as an artist was ‘the suspicion of being a dilettante,’ even though she did have an art degree from Yale University. But even there, women were treated differently. The main focus of the degree course was to get students on the Prix de Rome, but women were not allowed to apply for that so “the girls are allowed to develop pretty much as they please.”

The back cover blurb for Hutchins’ penultimate novel, Blood on the Doves, 1965 – an untypical, multi-voiced, Faulkneresque narrative – describes her background very nicely, underneath a photograph of Hutchins smiling broadly, sitting at the controls of the plane that she flew solo across America and looking nowhere near her age, which was then sixty-six. The logo on the side of the plane reads Super Cat, perhaps appropriately.

Although Maude Hutchins was born in New York and brought up on Long Island, she is half Virginian and half New Englander. Tutored, as she says, by a Connecticut Yankee, her grandfather, and a Virginian great aunt, she realized early that “I was always wrong.” This bringing up accounted also for her formal education ending at sixteen (grandfather said ladies do not go to college), and for her matriculation in the Yale School of Fine Arts after her marriage.

She received a B.F.A. from Yale University, but “piling clay on an armature in the basement of that University was not exactly an intellectual pursuit. I learned how to read, however,” she adds, “and had read most of ‘The Great Books’ before that term was invented.” She also learned to fly, and pilots her own plane.

. . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

For Hutchins’ family, being an artist was just about respectable – though she did cause a stir in Chicago by exhibiting life-size nude male statues – being a writer was something else.

Long before she thought about writing novels Hutchins collaborated on an illustrated 1932 book called Diagrammatics, for which she provided lightly erotic, neoclassical line drawings of young, nude women – they are rather like more minimal versions of Picasso’s Vollard Suite, the first of which appeared in 1930 or his illustrations for Ovid’s Metamorphoses, published in 1931.

They also resemble the erotic, Beardsleyesque illustrations of young girls that Willy Pogány, by then a well-known illustrator and set designer living in New York, provided for a 1926 English-language translation of Pierre Louÿs’ Songs of Bilitis, which Louÿs had originally claimed were his French translations of Greek manuscripts from the same era and sexual orientation as Sappho.

It seems that Hutchins herself initiated this project and, not yet herself a writer, asked Mortimer J. Adler, a professor from Chicago University, of which her husband was then president, to write the words. Adler provided a truly terrible sub-Gertrude Stein text; it is not obvious whether the text is a spoof and the whole thing was a joke. The volume was privately published in a luxurious, limited edition. Although it was not widely distributed, Hutchins’ family was not amused.

“When I was fourteen and visiting a great-aunt, I was late to luncheon,” Mrs. Hutchins relates, “and I said, ‘But I beat Sylvia at tennis.’ My aunt looked at me coldly and said, ‘We have never had an athlete in the family before.’ Three years ago, I sent a copy of Diagrammatics to an elderly cousin. In a letter to me, he said, ‘We have never had an author in the family before.’”

Much worse, from her family’s, and her then ex-husband’s point of view, was to come when she started to write novels; though Hutchins did not publish anything until after her divorce, she wrote under her married name. Hutchins’ first novel was published in 1948, when she was forty-nine, the age Shirley Jackson was when she died.

The respective ages of their daughters when they were writing their novels may partly explain why Shirley Jackson’s teenagers are almost entirely sex-free – except Natalie Waite of Hangsaman (1951), whose one experience of sex is so awful she erases it from her mind and Jackson erases it from the novel – while Hutchins’ teen girls embrace sex and sensuality with great joy and a total lack of inhibition.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Despite the aloof toughness her upbringing had given her, Hutchins is an example of a creative woman overshadowed – temporarily at least – by a dominant, alpha male. In 1921 she had married Robert Maynard Hutchins, who was to become the youngest dean of Yale Law School and then the youngest president of the University of Chicago. He was called Golden Boy even at the time.

Maude already had a moderately successful career as an artist and sculptor and was a rather glamorous figure: beautiful and striking, she was almost as tall as him. They were a golden couple and were compared to Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald; later they might have been compared to JFK and Jackie: it was at one time assumed that Robert Hutchins would either end up in the Supreme Court or running for president, though he did neither, partly at least because of the “trouble” he had with his wife.

In a memoir about Robert Hutchins, his former colleague Milton Mayer called Maude the “multifariously talented daughter of the editor of the New York Sun,” and said of her that, “her schooling was fashionable and her artistic talents were encouraged. She meant to have her own career – not her husband’s – and she had it. If he was shy, or stand-offish, she was genuinely aloof. She wasn’t meant to be a schoolteacher’s wife. (Perhaps she wasn’t meant to be anyone’s wife.)”

Scandalous stories

In a story published long after their divorce, “The Man Next Door,” published in her story collection The Elevator (1962), Hutchins writes a description of a man who seems to be a dead ringer for her ex-husband; it is by no means an unkind or unflattering portrait.

I am a country girl born and bred but my husband lives and thinks in a tiny city that he carries around inside his head. His handsome skull encloses very tall buildings and subways and elevators, and the buildings and subways and elevators are full of tiny cell-like people, each with his franchise, his exemption, and his problem. My husband is emperor, prince, chancellor, and his influence is like the handwriting on the wall.

In another story, Innocents,” in Love is a Pie (1952), a collection of stories and playlets (for which Andy Warhol designed multiple covers), Hutchins describes the relationship of a nameless couple that might possibly be a portrait of herself and Bob.

His outbursts of anger against her, which she feared, but which she preserved her strength for and which she made every effort to meet with the community, failing always, with the only “conclusions” he ever made. She was always fresh and he was always fatigued because it was her idea, not his; she was the artist. Unrequited love only comes to those who want it and even then it is not simple.

Artistic, creative, offbeat Maude never fit into her husband’s stuffy social milieu and caused him endless headaches. To “keep Maude quiet” and keep her busy, “poor old Bob” encouraged his wealthy friends to commission sculpted heads and busts from her – for enormous fees which many of his friends seriously resented – but this was never enough.

Maude scandalously paid undergraduates from her husband’s university, male and female, to model nude for her. She also produced family Christmas cards based on her own mildly erotic drawings that were sent to faculty and trustees; as one friend of Bob’s said about them in a memoir:

On at least one occasion with the nude figure of a going-on nubile girl holding a Christmas candle – the model was sensationally reported around town and gown to be the Hutchinses’ fourteen-year-old daughter Franja.

. . . . . . . . . .

Maude and Robert Hutchins

. . . . . . . . . . .

In the end, Bob got tired of keeping Maude quiet; after twenty-seven years of marriage, he left her in 1948 and she divorced him. He never spoke to her again. Within a year he had married his secretary; worse still, she was called Vesta – for a wife to be left for a secretary twenty years younger and even considerably shorter than herself is one thing, but if the other woman is called Vesta the horror is unimaginable.

Maude moved with her two younger daughters to the backwaters of Southport, Connecticut and stayed there, never remarrying and never – at least publicly – having any other serious relationship with a man; despite their differences, Bob must have been a tough act for any man to follow. And Maude didn’t need to work: Bob, whose salary was $25,000 a year, paid her $18,000.

Still, Maude was something of an alpha female herself, and thrived as an independent woman: she soon got her pilot’s license, as we have seen. Being left without a husband also seems to have encouraged Maude to write novels rather than concentrating on her visual art. She published nine novels between 1948 (the year of her divorce, so she must have been writing while she was still married) and 1967, plus two collections of her short stories, many of which had been published in leading magazines and printed in anthologies, including New Directions.

None of her publications were the kind of thing that the wife – even the ex-wife – of a highly respected member of Chicago society would be expected to produce, and she probably delighted in that fact.

Robert Hutchins published around twenty books of educational and political theory from 1936, when he was thirty-seven, to 1972, but, as mentioned earlier, Maude Hutchins was forty-nine when her first novel was published. She was sixty years old in 1959 when Victorine was released, and sixty-eight when her final novel was published.

The critics are shocked (or at least, uncomfortable)

Older women writing about sex makes middle-aged, male critics squirm; as we shall see, Hutchins suffered at their hands for daring to suggest that the mature woman – indeed any woman – might have lascivious thoughts. The New York Times said of her, “the sensuous is her window on the world; sexuality is the sea for all her voyages.”

Unlike Anaïs Nin’s work, most critics saw the sexual rather than the sensual; there was far too much sex in Hutchins’ novels for many people. At this time censorship was still very much the norm: Hutchins’ second novel, A Diary of Love was nearly prosecuted for obscenity; even the title seems designed to upset the prurient.

Some of Hutchins’ novels were, indeed, republished with sleazy, pulp-fiction covers: A Diary of Love was issued in at least three different pulp covers, all of which had above the title the teaser: “the sexual awakening of a teen-age girl.” At the bottom of the book’s cover, readers were assured that this was “complete and unabridged” — it had been previously issued in a censored version.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Hands of Love (formerly titled Victorine)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Victorine was reissued as The Hands of Love, with the blurb, “a strange love transforms a young girl into womanhood,” and Maisie was issued by the Paris-based, erotic-novel specialist Olympia Press with the quote “the shockeroo of the literary season.” The cover featured a woman in bed who looked like she might be a prostitute in the saloon of a Western movie.

“Poor Bob” must have felt each of these as an arrow in the back; her family was likely not amused either. Maude could have used a pseudonym, but where would have been the fun in that? These trashy covers and blurbs are entirely misleading and readers would have been seriously disappointed. It is not obvious whether she approved the lurid covers for these reprints of her books – as we saw with the now-classic lesbian pulp novels, authors at that time had little to no control over titles and covers – though Maxwell Geismar implies that she would not have:

Mrs. Hutchins would resent, I know, any description of her work as “erotic.” The curious thing about her writing, so remarkably open about all forms of personal behavior, was the prevailing tone of candor. If nothing human was foreign to her, everything human was a constant source of delight, of pleasure and gaiety.

When her book was banned by those sagacious guardians of the public morals, the Chicago police, Mrs. Hutchins was quite naturally bewildered. “I can assure you that I have no desire to shock, disrupt the morals or undermine the conventions of the general public,” she wrote at the time. “My defense for A Diary of Love is that having written it, I published it; and that I would not willingly withdraw any of it. My intention was purely artistic, and the subject matter innocence.”

Yet some of Hutchins’ books are still in the list of the prestigious literary house New Directions with far more sober covers, though A Diary of Love has a very slightly naughty line drawing by Hutchins and Love is a Pie still has its original 1952 Andy Warhol line drawing of a woman as a cover. Surely no twentieth-century writer except Nabokov has been represented by such a range of cover art.

. . . . . . . . .

Maude Hutchins’ books on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Victorine has even been reissued recently as a New York Review of Books Classic, part of an eclectic list that ranges from Balzac to Leonora Carrington, and includes Colette‘s The Pure and the Impure. Hutchins is now becoming part of the American literary canon and moving slowly out of the ghetto of sex-obsessed writers, where she had been closeted, but the critics of the time were generally not kind to her, variously accusing her of being too experimental/literary on the one hand and of being too raunchy on the other.

A review of the short story collection Love is a Pie in the Saturday Review, for January 3, 1953, took the former line.

The stories, written in a prolix and often impenetrable prose, have the self-conscious literary stamp of the little magazines which first published several of them… For a book devoted to the tender human emotion, Love is a Pie seems curiously aloof and unemotional. It consists largely of strained and wearisome cerebral exercises.

Nine years later, a review of Honey on the Moon in the same magazine for February 29, 1964, slung at her the second kind of criticism.

According to all traditional criteria, the book is almost a complete failure. It has no core of moral significance; it takes place in no recognizable social context; most of the characters never come alive, and ninety percent of Mrs. Hutchins’s dialogue could never have been spoken by a human being.

But, although she never distinguishes between love and love-making, Hutchins writes about pure, animal sex with a genuine lyrical passion unmatched by any other contemporary American woman. And the blurry, schizoid interior monologues are almost as good – and hard to read – as those in Tender Is the Night.

If you are willing to endure a banal, pointless novel just for a few first-rate passages of good old you-know-what and a brief close-up of a personality tearing itself apart, you will like Honey on the Moon.

Even as late as 1964, critic Stanley Kaufmann was advising the then-sixty-five-year-old Hutchins to grow up and stop being so obsessed with sex; male critics have always tended to treat female novelists like naughty children – perhaps Hutchins was old enough to be his mother, and perhaps that was his problem with her. Male novelists, of course, never grow up and are allowed, even expected, to hang on to their obsession with sex their whole life.

Many novelists pass through such a period, but there comes a time when ‘then they went to bed’ suffices; or when the bed is to society what war was to von Clausewitz, a continuation of politics by other means. To remain as interested in sex as Colette was all her life long, and as Mrs. Hutchins continues to be, requires an almost monastic single-mindedness.

To be compared with Colette may be considered no insult: Anaïs Nin certainly meant it as a compliment; Colette wrote a series of novels that show the coming of age of her heroine Claudine, begun in 1900 with Claudine at School. Hutchins and Colette are probably the best exemplars of Nin’s ideal of an author who can write erotically without having any – or at least not very much – actual sex in her work.

The Memoirs of Maisie is a good example: despite the lurid picture on the cover of the pulp edition, which misleadingly shows a woman lying seductively on a bed in her underwear and despite the “shockeroo” quote in the blurb, Maisie is a grandmother on the verge of dementia, surrounded by her daughters and granddaughters (men are rarely at the center of Hutchins’ novels and here, they’re pushed way out to the periphery). Maisie does however have reveries of her younger, passionate self, almost like an older Molly Bloom.

The nearest Maisie gets to a sex scene is written erotically, but no actual sex happens – because of the man’s temporary impotence. Colin and Sissy are both married, but not to each other; she agrees to meet him. Colin returns to his wife, knowing that he “had been fooled. He felt as if he had been lifted out of a magician’s hat by the ears and exposed to ridicule, wet and slinky, pink-eyed rabbit.”

Some of the short stories collected in Hutchins’ The Elevator also contain wonderful examples of erotic but sex-free writing. Hutchins can even make a description of a bride’s bouquet at her wedding crackle with an erotic charge. This is from ‘The Wedding,’ also in The Elevator.

The bride looked at the bouquet and saw that it was beginning to droop. One of the topaz roses turned brown, Violette began to shrink and a pink carnation trembled as if in a convulsion. A number of petals detached themselves and floated aimlessly in the still air and a hatch of yellow pollen, riding some tiny updraft, shone like powdered gold. She felt the stems grow feverish and then cold.

A pair of stamens detached themselves and floated downward, a pistil was bathed in perspiration, and the Shasta daisies, as if they were guillotined, lost their heads. She felt what remained of the bouquet struggling to be free of her hands, the flowers were delirious and the pulses in her own wrists began to beat like drums.

In The Future of the Novel, Nin points out perceptively that Hutchins tended to center her works around and see the world through the eyes of young people, especially adolescent girls, who are set against their awful parents while we see them coming of age:

Some of her parents resemble the parents of Cocteau’s Les parents terrible. It is the adolescents in her book who carry the burden of clairvoyance. They see, they know. It is not a battle between innocence and evil but between awareness and hypocrisy. Her adults are hypocritical. The novels are requests for truth, and this truth is usually uttered by those at the beginning of their lives. The work is unique, rich, animated by a sprightly intelligence and verve.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Daring Fiction of Maude Hutchins appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 28, 2021

Joan Didion: A Tribute to the Writer’s Writer

On December 23, 2021, when I learned that writer extraordinaire Joan Didion had passed away at the age of 87, I did what any friend would do: I canceled the day’s planned activities and concentrated on everything Didion.

For forty-four years, Joan Didion had been my own constant and portable companion: of course I needed to devote time to adjusting to the news of Didion’s passing. Our friendship was, obviously, one way. I can proclaim to know piles of intimate Didion facts and details, but of course Didion never knew me.

But that’s besides the point. Didion will remain one of the most significant influences on my writing life: what one remembers about her is the strength and authority of her writing. No one could imitate her; indeed, whenever anyone tried to channel Didion they were detected immediately.

My longterm Joan Didion love affair began in 1977. One of my very favorite English professors at San Francisco State University held up a copy of Slouching Towards Bethlehem. “We learn best from what is good,” Professor Ritter stated, “and Joan Didion is the best.”

Our class was being introduced to the “New Journalism.” Professor Ritter had no problem in declaring that Joan Didion’s nonfiction easily surpassed the New Journalism of Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson. Tom Wolfe needed his white suit and Hunter S. Thompson demanded personal physical excess to showcase the New Journalism.

Joan Didion had her sublime sentences filled with a myriad of details to convey her personal and wholly authentic stories. She wrote about nearly every cultural and political upheaval that transformed the U.S. from the 1960s to the present day.

Didion was compelled to find the story behind the story: what was meant by the “disparate images” that was presented to the American public as news.

. . . . . . . . . .

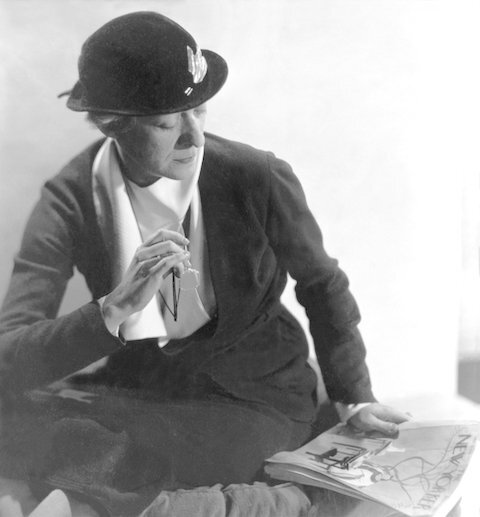

Joan Didion in 1977 (AP photo)

. . . . . . . . . .

“Didion often uses a detail that has stuck with her from a certain moment, which many seem extraneous nut which she uses for a purposes,” fellow writer Sara Davidson explained. “A hallmark of her work is that she repeats those details, almost like a phrase that recurs in a symphony.”

When Davidson asked Didion why the repetition of details, Didion responded with the advice, “I do it to remind the reader to make certain connections. Technically, it’s almost a chant. You could read it as an attempt to cast a spell.”

And cast a spell she did. The writer reads a few paragraphs where Didion does her repetition of fascinating and beguiling — nearly lyrical — phrases as she may describe a wholly depressing scene of heartbreak. Didion is the writer’s writer: her writing may appear deceptively easy, but she’s the prose master other writers return to in hopes that they can do what she does: explain the world with an authentic perception that cannot be imitated.

“Writers are always selling someone out”

Another Didion lesson that I have used for forty-four years came from a phrase — explained by SFSU Professor Ritter for over ninety minutes — of this oft-repeated sentence of Didion’s: “Writers are always selling someone out.”

It’s a line that Didion critics and detractors dislike and disparage for its hint of arrogance. I understood this line as the writer’s only compulsion is the search for truth, the story behind the story, and if the reader is uncomfortable with the outcome, the writer bears no responsibility. The writer need not pay attention to someone’s discomfort: there is too much going on in the world for the writer to stop reporting.

Didion’s husband, John Gregory Dunne, explained that line this way: “No one sees oneself as others do, and if you truly write how you see an individual, that person may be disturbed.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Joan Didion books on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Thus, it is the writer’s solemn duty to write the story behind the story in search of the truth. And, to write that story well in their own authentic style — or, what was the point in writing at all if one avoids the reality of our times.

Forty-four years ago I first read these lines from Slouching Towards Bethlehem from the essay On Keeping a Notebook:

“It all comes back. Perhaps it is difficult to see the value in having one’s self back in that kind of mood, but I do see it; I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering to the mind’s door at 4am and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends.”

Thinking about Didion and the tremendous legacy that she gave to her readers, I turn to that phrase in gratitude. I like to re-visit my younger writer self who waited for the release of The White Album and was inspired to write the found details in my own 1960s tale. Or, I go forward two more decades and I find myself still searching for some hidden truth, the story behind the story, and I find it.

I credit Joan Didion for that. Often Didion would state that she dreaded going to her writing desk every morning but she knew she must. And that is the another lesson that Didion gave to me: you just keep on writing because you are committed to the stories that need to be told.

“I’m not telling you to make the world better, because I don’t think that progress is necessarily part of the package, I’m just telling you to live in it. Not just to endure it, not just to suffer it, not just to pass through it, but to live in it. To look at it. To try to get the picture. To live recklessly. To take chances. To make your own work and take pride in it. To seize the moment …” (from a 1975 Commencement Speech at University of California Riverside)

Contributed by Nancy Snyder, who writes about women writers and labor women. After working for the City and County of San Francisco for thirty years, she is now learning everything about Henry David Thoreau in Los Angeles.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Center Will Not Hold is the excellent

2017 documentary on Joan Didion

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Joan Didion: A Tribute to the Writer’s Writer appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Bread Givers by Anzia Yezierska (1925)

Bread Givers by Anzia Yezierska (1880 – 1970) is the best-known novel by this immigrant writer whose work reflected the Jewish immigrant experience in America of the early 1900s. To set this kind of story down with a female perspective was a rarity in her time, reflecting the author’s chutzpah and determination.

At the age of ten, in 1890, Yezierska arrived with her family to New York City’s Lower East Side. A product of the immigration wave of the late 1800s, she never quite shed the feeling of being an outsider.

Longing to rise above her circumstances, she was somewhat hampered by her brittle personality and a measure of self-loathing. In her final book, the autobiographical Red Ribbon on a White Horse (1950), she wrote: “With a sudden sense of clarity, I realized the battle I thought I was waging against the world had been against myself, against the Jew in me.”

Bread Givers, an autobiographical novel, delves into the well-trodden theme of an immigrant family whose children strain against Old World parents. The father, Reb. Smolinsky might be learned in the holy Torah, but he’s childish, impractical, and inflexible when it comes to his daughters. One 1925 reviewer described his character as “Dickensian.”

The three daughters chafe under their father’s domination. The youngest and feistiest is Sara, oddly nicknamed “Blut und Eisen” (Blood and Iron) from the time she is tiny. She rebels from the start, fighting for her autonomy, seeking self-determination. We can imagine that she is Anzia, through and through. The process of breaking away from her father’s domination is painful. Some of her strivings are awkward and uncomfortable, but she emerges as a person (mostly) in command of her world.

. . . . . . . . .

Anzia Yezierska

. . . . . . . . . .

Bread Givers bestowed a greater measure of success to Yezierska, who three years earlier had published the novel Salome of the Tenements. She wrote many fine short stories and even had a stint as a Hollywood writer. Hungry Hearts (1920), her first collection of short stories, was made into a successful 1922 silent film. Yezierska came to be known in Hollywood as “the Sweatshop Cinderella.” though she resented this rags-to-riches stereotype.

Long before her death in 1980, she all but disappeared from the literary world. The mid-1970s brought a wave of reconsiderations of her stories and novels. Bread Givers was reissued in 1975 and 2003, and some of her stories were anthologized, introducing them to new audiences.

In a 1925 essay in the Salt Lake Telegraph, Yezierska mused on what prompted her to write Bread Givers:

“I have always wondered why the people I know and lived with were never found in stories. Whatever I read of the poor were not my poor; not the life I had lived. They were dressed up in romance, in drama, in colorful climaxes that made fine literature …

The living people in their everyday working clothes with all the lines and wrinkles of work and worry were not there. The brutal fight over pennies at the pushcart, the cheap cafeterias where the hungry working girl goes for food only to come out hungrier after her meal than before; the terror of the poor on the first of the month when the rent has to be paid: these realities were too trivial, too sordid for stories.

And yet I knew that in this grinding waste of the dull everyday lay buried rich drama, more colorful than any false heroics of fiction. This conviction that the poorest life is rich enough for the greatest story, that the real struggle of the washerwoman, the shop girl, the fishwife, no matter how sordid, how ugly, throbs with dramatic beauty, is what goaded me to write.”

Despite occasional awkward and overwrought prose, Bread Givers is still eminently readable, and was highly praised upon its publication. In its 1925 review, the New York Times praised the novel for “enabling us to see our life more clearly, to test its values, to reckon up what it is that our aims and achievements may mean. It has a raw, uncontrollable poetry and a powerful, sweeping design.”

. . . . . . . . . .

See also:

How I Found America by Anzia Yezierska

. . . . . . . . . .

From the original review in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 5, 1925: When Anzia Yezierska wrote Salome Of the Tenements, all applauded. New York has a ghetto, a legendary yet pitifully and stubbornly real maze of dingy brick walls, where cobblestones make wagons rattle and trucks bounce; where every one of long rows of pushcarts has its screaming peddler and haggling customers; where streets are crowded and each fire escape has its ragged washline and show of bedding airing …

… Where basements are gloomy and attics are fetid and men and women and squalling children cling despairingly to traditions that are worn out even in the Old World. as they reach out eager hands for the milk and honey of the Promised Land. this America of ours.

It has been in this ghetto that the sociologist has written his books and quarreled with his brothers, jealous, as though the place belonged to him, and, because it did not suit his purpose, angry if anyone suggested the same sightless urge people for color and beauty was fermenting along with the disease and living blight, in the melting pot.

Anzia Yezierska, however. dared to find poetry, ideals, and even a measure of grimy contentment on Old Hester Street. The Russian immigrant Jew, to her, is a person and not a specimen for study.

Bread Givers, the latest Yezierska panorama of ghetto lives, published by Doubleday, Page & Co., has its human feeling, the divine comedy of the dreadful commonplace, and the glory of achievement, small to who inherited North America from our ancestors. but great to the family of circumstance reduced in Europe, poverty-stricken here and risen again from the basement by the second generation.

The ghetto has its flavor. Flavors being so much a matter of odor, he rest of New York City avoids its Lower East Side as much as possible. Stomachs that can stand herring and rye bread three times a day make it so. Yet Yezierska does not grow hysterical over these, her people. There is a saving sense of humor in Bread Givers.

The reader is looking at real people, living with them, suffering their little scandals, dreading the arrival of the rent lady, stuffing butter-less bread to ease the gnawing pangs of hunger, Papa shouting Hebraic invocations to Jehovah. while his daughters fight to keep him supplied with soup and the roof over his head.

Papa dabbles in his weak business ventures and his moments of religious elation while the landlady bangs at the door; selling his daughters to fine husbands—or at least. to any husbands—for the sake of his old age and sold out by his own bargaining—it would be sardonic if there were less feeling and filial affection woven into the tale.

. . . . . . . . .

Bread Givers on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Marrying off Bessie to the fish merchant, for instance, the fish merchant who was so carried away by his wrath that he threw dollars’ worth of change into a distracted woman’s face in a mutually greedy argument over the price of flounder. Papa, who chanted from the Torah and who worshiped Jeremiah, drove the bread from his mouth by breaking the hearts of his daughters and wearing out that stolid machine, his wife.

The naked simplicity of the poor which strips them of all inhibitory reserves and leaves them free to climb upward, since they cannot sink lower, comes to life in Bread Givers. Anzia Yezierska does what Fannnie Hurst tries to do. One admired the expert craftsmanship of Lummox, but it was, after all, only a somber piece of storytelling. The rise of little “Blut und Eisen” (Blood and Iron) — what Papa calls Sara, his most stubborn, determined daughter, comes only from a deep suffering and a great experience.

Chanting the Torah did not pay the rent but it did drive Sara from her Papa. As the dean of her college told her, she was a pioneer. And she was an immigrant, escaping from the ghetto to the other side of town. There are many like her, all over. We do not always like their presence, but that is because we fail to understand them.

We have not taken into account the brave adventure they set out upon, uprooting themselves from the tenements and pushing painfully into a new land of sunshine, grass, and sky, a paradise that to us means only a lawn to be cut, storm windows to be put on, and a commutation ticket to be bought the end of every month.

Going so high that she married a school teacher made Sara a success in her world. It is a crude world. too. But the author, wringing the story out of the depths of her heart, somehow transforms herself into a stately Druid priestess, singing sagas.

Bread Givers belongs among those few books that are of contemporary America, a faithful picture without monotony, an exciting account without cheapness. It lacks cant and it lacks prejudice. It is a perfect example of high art in heartthrobs. “It wasn’t my father. but the generations who made my father whose weight was still upon me,” concludes the story.

. . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

Jewish Women in Novels by Early Jewish Female Writers

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Bread Givers by Anzia Yezierska (1925) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 24, 2021

Jewish Women in Novels by Early Jewish Female Writers

Depictions of Jewish women in fiction or memoir by Jewish female writers prior in the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th were exceedingly rare, whether in English or translation. That makes the works discussed ahead rare gems, even if they weren’t brilliant by the highest of literary standards. All are eminently readable, however, and completely fascinating.

Working back from Vera Caspary’s Thicker Than Water (1932) to Amy Levy’s controversial Reuben Sachs (1888), these novels, often autobiographical (as well as one memoir) offer gritty, realistic glimpses into Jewish family and romantic life of their times.

Excerpted from the forthcoming book A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Novels of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth, reprinted with permission.

. . . . . . . . . .

Thicker Than Water by Vera Caspary (1932)

Vera Caspary’s Thicker Than Water (1932) is unlike any other of her novels: it is a family saga spanning forty-six years, starting in the 19th century and bringing us right up to date at the end of the 1920s twenties flapper era with no concern for tradition or history, only for the present. Caspary made it clear that the family in this story is her own family.

Out of memories awakened in Mama by my descriptions of the sister she had not seen for so many years came the notion of a novel. This was another novel I had to write. Nothing could keep me from it, neither fear nor practical considerations nor intimations of future gutters. I wrote as I had always wanted, completely absorbed in a tale of my mother’s generation, my sister’s girlhood and my own time, a novel that recorded the passing of forty-six years in a family; my family disguised, dramatized, but essentially the Casparys.

Caspary herself was a thoroughly modern working woman, earning unheard of sums of money for a woman her age. Unencumbered by family, religion, or husband, she traveled the world writing. As the review of Thicker Than Water in the New York Times said:

Writing is not necessarily a sedentary occupation – not when Vera Caspary is the writer. A new book, Thicker Than Water, announced for immediate publication by Liveright Inc., was started in Great Neck and continued on the boat en route to England. The first few chapters were thrown away in London, and the author started all over again in Paris. She continued writing on the boat coming back to the United States, finished the book in New York, corrected it in Chicago and proofread it in Brookfield, Conn.

The central character at the start of Thicker Than Water is Rosalia, the name of Caspary’s grandmother’s sister and an anagram of Solaria, the central character of Caspary’s first novel The White Girl. She herself is a modern woman by the standards of the end of the 19th century and has no wish to find a husband.

However, her younger brother wants to marry, and by family and social tradition, he cannot do so until his elder sister is married. Rosalia isn’t considered attractive, is rather old for the marriage market, and has very little money – she was adopted by her uncle when her father lost his fortune. She settles for a Jewish man of German extraction, despite her family – like Caspary’s family – looking down on any Jewish families not of Spanish or Portuguese descent. As Caspary wrote in her autobiography,

Indifferent though we were to religion, we were contemptuous of Jews who denied being Jewish or changed their names and contradicted ourselves with scorn for those whose names ended in -witz or -ski. Papa’s sister, my beloved Aunt Olga, the most merciful of women, would often tell me in a hushed voice, “They’re not the finest kind of Jewish people, dear.”

Rosalia’s husband takes a mistress. And then another. He buys Rosalia a house, where she feels stuck with her daughter, unable to fulfill all the dreams she had, most of which came from books. As the years go on, her daughter Beatrice leaves home and then leaves her husband; she goes off on her own to make a fortune in business which she then loses in the 1929 Wall Street crash.

And then there is a granddaughter called Rosalie, or Little Rosie, who marries an impecunious artist. In a gesture of reconciliation with both her granddaughter and the modern world, Rosalia gives Rosie a family heirloom which she has guarded zealously a whole life.

. . . . . . . . . .

Salome of the Tenements (1922) and Bread Givers (1925)by Anzia Yezierska

Anzia Yezierska was one of the precursors to Caspary’s saga of Jewish family life, Thicker Than Water. Like Caspary, but unlike most traditional Jewish writers, Yezierska put women at the center of her writing— those born into poverty-stricken Jewish families in New York’s Lower East side. Her stories were first collected in Hungry Hearts, 1920, and made into a silent movie in 1922.

Bread Givers (1925) remains Yezierska’s best-known works. The novel depicts the struggle of Sara Smolinsky and her three sisters with their orthodox father, a Torah scholar who refuses to work. He therefore earns no money and tries to force his daughters to marry against their will so they can support him.

Fortuitously, Sara wins a thousand dollars in an essay competition at her college and becomes a teacher, escaping from her slum background and the tyranny of her father, “the tyranny with which he tried to crush me as a child,” and comes of age as an independent single woman in America.

A triumphant sense of power filled me. Life was all before me because my work was before me. I, Sara Smolinsky, had done what I had set out to do. I was now a teacher in the public schools. And this was but the first step in the ladder of my new life. I was only at the beginning of things. The world outside was so big and vast. Now I’ll have the leisure and the quiet to go on and on, higher and higher.

Once I had been elated at the thought that a man had wanted me. How much more thrilling to feel that I had made my work wanted! This was the honeymoon of my career!

In Yezierska’s Salome of the Tenements (1922) Sonya Vrunsky is another poor but strong-minded, independent Jewish woman, another creation worthy of Caspary herself.

The title of the novel is a reference to the biblical Salome, who made her stepfather cut off the head of John the Baptist for her. In the New Testament gospels of Mark and Matthew however, it is her mother who makes Salome ask for the severed head.

A woman should be youth and fire and madness — the desire that reaches for the stars. A man should be wisdom, maturity, poise. (Anzia Yezierska, Salome of the Tenements)

Sonya Vrunsky decides she is going to escape poverty by marrying an “Anglo-Saxon” millionaire. She does, though in the end she decides he is not for her, goes off with someone else and carves out a career for herself as a fashion designer.

Manning, the millionaire husband, having previously always been “fastidiously aloof,” unravels when he realizes that Sonya has been deceiving him; this is her coming-of-age moment both as a woman and as a Jewish woman.

Dazed, struck into sudden awakening by her repulse, his burning gaze covered her from head to foot. Hair disheveled, waist torn away, revealing the heaving bosom, the white throbbing neck, she stood there, superb, ravishing in her fury … Her scorn stripped him naked, exposed him to himself.

“So this is Manning, the Anglo-Saxon gentleman, the saint, the philanthropist – the savior of humanity.”

Wonder was in her eyes and cold anger in her voice.

“You didn’t want me when I was burning for you,” she laughed harshly, remembering how she had lain beside him night after night, sleepless, nerves unstrung, hungering in vain for a kiss, for a breath of response, for a sign of his need of her. “Now I don’t want you.”

In the triumph of her sex which he had once so cruelly mortified she looked fully at him. This was her moment. She had it in her to bring this wreck back to life – to give him the warmth, the passion, the ardor that none of the women of his kind could give. There he stood perishing for her. . . Here was a child that needed comforting. And she was a woman. For the first time in all her life she was a woman.

. . . . . . . . . .

I Am a Woman — and a Jew by Leah Morton (1926)

I Am a Woman – and a Jew (1926) is an autobiographical novel by Leah Morton (1889 – 1954; born Elizabeth Gertrude Levin) repeats this idea of the superiority of Spanish and Portuguese descent and promotes the idea that there is an ancient Jewish race memory:

… we Jews are alike. We have the same … sensitiveness, poetry, bitterness, sorrow, the same humor, the same memories. The memories are not those we can bring forth from our minds: they are centuries old and are written in our features, in the cells of our brains.

Morton combines this idea with the anti-Polish racism of her family, identical to the racism of the Piera family in Thicker Than Water, although Morton herself was born in Poland.

I, very tall for my age, very thin, with enormous brown eyes, and excessively high forehead that we all thought the acme of homeliness, and a funny nose that had neither the exquisite delicate curve of Hannah’s, nor the round impudence of Simeon’s, but was only a sort of parody of the Polish noses servants had.

They called me the “Polak,” because I was quick and vivid, dreamy and intense, and sometimes obstinate as a stupid Polish servant who will not see what her bettors tell her. When my father said quietly, “Do thus,” and I asked, “Why?” he would look at me with his deep glance and reply, conclusively, “Do not be a little Polak.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The Promised Land by Mary Antin (1912)

Another female Jewish author to write of the experience of immigration was Mary Antin (1881–1949) born, like Yezierska in Polotsk (or Polotzk), then part of Russia and now in Belarus. Antin’s parents were trying to escape the rampant anti-Semitism in Russia:

… they considered it pious to hate and abuse us, insisting that we had killed their God. To worship the cross and to torment a Jew was the same thing to them. That is why we feared the cross. Another thing the Gentiles said about us was that we used the blood of murdered Christian children at the Passover festival.

The title of Antin’s memoir, The Promised Land (1912) is not ironic: unlike the fictional Sonya in Salome of the Tenements, the autobiographical Mary transcends the poverty into which her new life in Boston plunges her family, at first in her own head and later in the achievements of her life. For her, America really is the promised land, where everything is possible.

Antin describes herself in the book as “striving against the odds of foreign birth and poverty, and winning, through the use of abundant opportunity, a place as enviable as that of any native child.” Mary’s family live among the slums of Dover Street in Boston’s ethnic South End but, in her head, Mary is in a different place altogether.

Dover Street was my fairest garden of girlhood, a gate of paradise, a window facing on a broad avenue of life. Dover Street was a prison, a school of discipline, a battlefield of sordid strife. The air in Dover Street was heavy with evil odors of degradation, but a breath from the uppermost heavens rippled through, whispering of infinite things.

In Dover Street the dragon poverty gripped me for a last fight, but I overthrew the hideous creature, and sat on his neck as on a throne. In Dover Street I was shackled with a hundred chains of disadvantage, but with one free hand I planted little seeds, right there in the mud of shame, that blossomed into the honeyed rose of widest freedom.

In Dover Street there was often no loaf on the table, but the hand of some noble friend was ever in mine. The night in Dover Street was rent with the cries of wrong, but the thunders of truth crashed through the pitiful clamor and died out in prophetic silences.

Antin did break free of poverty and of the prejudice against her creed, by her own efforts. She attended the Girls’ Latin School in Boston, married a scientist and went to the women-only Barnard College in New York.

There I took all the honors that I deserved; and if I did not learn to write poetry, as I once supposed I should, I learned at least to think in English without an accent. Did I get rich? you may want to know, remembering my ambition to provide for the family.

I can reply that I have earned enough to pay Mrs. Hutch the arrears and satisfy all my wants. And where have I lived since I left the slums? My favorite abode is a tent in the wilderness, where I shall be happy to serve you a cup of tea out of a tin kettle and answer further questions.

Yezierska’s stories and Antin’s memoir are set among deep poverty in New York and Boston, from which the heroines attempt to escape in their various ways, whereas Caspary’s Jewish family, both the real-life version recounted in The Secrets of Grown-Ups and the fictional Thicker Than Water are bourgeois and living in Chicago.

. . . . . . . . . .

Reuben Sachs by Amy Levy (1888)

Closer to Caspary’s fictional family in social standing if not in geography are the wealthy Sachs family in Reuben Sachs (1888) by Amy Levy (1861 – 1889). Sachs, a British novelist and feminist essayist, was the first Jewish woman at Cambridge University, Levy lived the life of the “New Woman” with a circle of literary and sometimes lesbian friends, especially her probable lover Vernon Lee.

Levy’s novel The Romance of a Shop (also published in 1888), is a “New Woman” novel about four sisters trying to make it in business. In 1886, Levy had published “The Jew in Fiction,” in the British Jewish Chronicle. She said that no novelist so far had succeeded in “grappling in its entirety with the complex problems of Jewish life and Jewish character. The Jew, as we know him today … has been found worthy of none but the most superficial observation.”

Levy took her own life at the age of twenty-seven and became the first Jewish woman to be cremated in England; Oscar Wilde, who had published her stories in his Woman’s World, wrote an obituary for her.

The Sachs family lives in the most prestigious parts of London, England (Levy’s own parents lived in Bloomsbury). The Sachses are “a family of Portuguese merchants, the vieille noblesse of the Jewish community.” Both Caspary’s real family and her fictional family in Thicker Than Water share this pride in their ancient Portuguese heritage, especially compared to more recent German and Polish Jewish immigrants, on whom they look down.

In the Sachses’ London Jewish community, “with its innumerable trivial class differences, its sets within sets, its fine-drawn distinctions of caste, utterly incomprehensible to an outsider, they held a good, though not the best position.”

Levy’s short novel, subtitled An Essay, was written in response to what she considered the over-sentimental treatment of the Jewish characters and what she considered the naïve, romantic view of Zionism in George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda (1876) with its “little group of enthusiasts, with their yearnings after the Holy Land.” When Daniel finds out that his mother has hidden his Jewish heritage from him, Daniel is ashamed of her rather than of being Jewish:

It would always have been better that I should have known the truth. I have always been rebelling against the secrecy that looked like shame. It is no shame to have Jewish parents—the shame is to disown it.

But his mother is unrepentant.

I rid myself of the Jewish tatters and gibberish that make people nudge each other at the sight of us, as if we were tattooed under our clothes, though our faces are as whole as theirs. I delivered you from the pelting contempt that pursues Jewish separateness.

Despite the man’s name in the title of Levy’s Reuben Sachs, the novel is at least as much about Reuben’s cousin Judith Quixano, a Caspary woman in the making, similar in some ways to Rosalia, her counterpart in Thicker Than Water and to Solaria in The White Girl. Judith’s patrician Portuguese ancestry comes out in her looks.

She was twenty-two years of age, in the very prime of her youth and beauty; a tall, regal-looking creature, with an exquisite dark head, features like those of a face cut on gem or cameo, and wonderful, lustrous, mournful eyes, entirely out of keeping with the accepted characteristics of their owner.

Judith (whose name references the Biblical story of Judith and Holofernes), who has been adopted by her aunt and uncle after her family lose their money, doesn’t have a financial inheritance of her own and, despite her good looks, she knows her adoptive parents will find it difficult to marry her off into another good Jewish family.

Judith is in love with Rueben and vice versa, although they are first cousins. It looks for a while as if they will marry, but Judith receives a marriage proposal from the non-Jewish, wealthy Bertie. She reluctantly accepts.

Material advantage; things that you could touch and see and talk about; that these were the only things which really mattered, had been the unspoken gospel of her life.

Now and then you allowed yourself the luxury of a fine sentiment in speech, but when it came to the point, to take the best that you could get for yourself was the only course open to a person of sense.

The push, the struggle, the hunger and greed of her world rose vividly before her. Wealth, power, success—a flaunting success for all men to see; had she not believed in these things as the most desirable on earth? Had she not always wished them to fall to the lot of the person dearest to her? Did she not believe in them still? Was she not doing her best to secure them for herself?

Judith regrets her decision almost immediately and wishes she had held out for Reuben. Then she hears that Rueben has died. The novel ends on a low note, with Judith’s dark thoughts.

It seemed to her, as she sat there in the fading light, that this is the bitter lesson of existence: that the sacred serves only to teach the full meaning of sacrilege; the beautiful of the hideous; modesty of outrage; joy of sorrow; life of death.

Although it was a commercial success on both sides of the Atlantic, the British Jewish press hated Reuben Sachs, with its merciless portrayal of such shallow, unsympathetic characters. Jewish World said of Levy: “She apparently delights in the task of persuading the general public that her own kith and kin are the most hideous types of vulgarity.”

The Jewish Chronicle didn’t even review it, despite having published Levy’s earlier essay, but referred to it as being “intentionally offensive.”

In an interesting coda, Reuben Sachs was responsible for another novel about a young Jewish woman coming of age, though the novel itself was fictional, a novel within a novel. The year after Reuben Sachs appeared, and soon after Levy’s death, the future Zionist campaigner Israel Zangwill, who coined the phrase “melting pot” in the title of a play, was commissioned by the Jewish Publication Society of America to write Children of the Ghetto, concerning a group of characters in the Jewish East End of London.

In the novel, Esther Ansell, many of whose views seem to echo Zangwill’s own, writes a novel, Mordecai Josephs, under a male pseudonym; no one knows she is the author; her novel seems to be based on Reuben Sachs. Everyone in Esther’s set hates the book and the way it betrays the mercenary and unspiritual bourgeois Jewish inhabitants of London, exactly the criticism the Jewish press had of Reuben Sachs.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture: Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Jewish Women in Novels by Early Jewish Female Writers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 15, 2021

Recalling the Bobbsey Twins and Their Fictional Author, “Laura Lee Hope”

There are certain authors from one’s schoolgirl years who acquire an aura with their ability to hook the reader, leave her asking for more, and linger in the memory. One such author was Laura Lee Hope, with her many adventure tales featuring the Bobbsey Twins — two sets of fraternal twins, Nan and Bert, and the younger Flossie and Freddie.

Whilst the older twins are dark-haired and of serious disposition, the younger two are impish and blond. My favorite, as I recall, was Flossie. Her father often referred fondly to her as “my fat fairy.” In today’s children’s literature, it might not go down well for a child to be referred to as fat, even affectionately.

In the early stories, the twins begin to grow older. Perhaps the idea of them overtaking the age of their readers was too risky. And so, the older twins were given the permanent age of twelve, while the younger twins remained forever six years old.

As fictional characters, it was easy for them to be the same age chronologically and it never struck their young readers that they would one day go beyond those idyllic childhood years to face the realities of adulthood.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

No real “Laura Lee Hope”Imagine the surprise when a faithful Bobbsey Twins reader discovers that there isn’t, and never was, a real Laura Lee Hope. This name was a part of the Stratemeyer Syndicate, which successfully published these stories for the long-running spell of seventy-five years! The first of the seventy-two volume series was said to have been written by Edward Stratemeyer (The Bobbsey Twins; or, Merry Days Indoors and Out, 1904). The series in its original form concluded in 1979.

Two subsequent efforts at restarting the series didn’t meet with the same level of publishing success, possibly because times had changed, along with reader expectations.

Stratemeyer set the ball rolling and was joined by other authors credited with writing the books, including Lilian Garis, Elizabeth Ward, Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, Andrew Svenson, June Dunn, Grace Grote and Nancy Axelrad, to name a few. Other writers also collaborated in the writing and editing.

In today’s terminology, they would likely be called ghost-writers and relegated to oblivion. Yet it’s a blessing to be able to credit the many authors of the Bobbsey Twin series, which were so much a part of young readers’ lives, including my own. In those innocent years, I had no way to tell writing styles apart, or perhaps all the authors followed the template of “Laura Lee Hope” quite precisely.

Interestingly, the same syndicate published the Nancy Drew books under the name “Carolyn Keene” and the Hardy Boys series under the name of “Franklin W. Dixon” —these names also represented a number of contributing authors. (There was a first “Carolyn Keene” who helped establish the Nancy Drew series, though, and that was Mildred Wirt Benson.)

Trying to stay relevant

The twins’ father, Mr. Bobbsey, is a lumberyard owner in Lakeport; their mother, Mary, is a stay-at-home mom, as was common in those times. Other characters included their black cook Dinah Johnson and her husband, Sam Johnson, the Bobbsey family’s Man Friday.

The characters also included various friends and foes, like the school bully. There were also a whole host of pets — a couple of dogs, a duck, and Snoop the cat. The latter is worthy of mention because “he” starts off male until being lost at a circus and then returns as a “she,” likely as a result of the next tale being written by another author in the syndicate.

In the 1960s, the Stratameyer Syndicate attempted to rewrite and update the series to keep up with the changing times. Automobiles replaced buggies, and the lovable Mrs. Bobbsey was now holding a part-time job. The most significant of all the changes is in the portrayal of Dinah and Sam, the two Black characters, who had to be dealt with differently, to factor in changing social mores.

. . . . . . . . . .

Bobbsey Twins books on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

It was interesting for me to discover that the term “Bobbsey Twins” came to be used as a synonym for sincere do-gooder duos, or two people who are inseparable. The books showcased a world of perfect parents, ample creature comforts, and enough adventure and excitement to balance the realization of a secure home environment.

The books are said to have sold millions of copies and still adorn bookshelves in America, yet there could be a message in its appeal to children from other parts of the world, like faraway India.

Today, the world is a global village with technology connecting citizens through social media platforms. You can be friends with people from all over the world, even before you wind up meeting them in person (if you ever do).

But perhaps stories like the Bobbsey Twins were precursors in this regard, as they tapped into what was of universal appeal to children across the world —a sense of well-being that comes from being part of the life of a wholesome family, joined by their adventures. In a country of disparities like India, that can only belong to those children who are privileged enough to have an education and are blessed with parents who encourage their imagination to soar, providing them access to books in an acquired language about people who live in other lands.

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar: Melanie is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about The Bobbsey Twins series All of the Bobbsey Twins books in order Public domain works by “Laura Lee Hope” Further info on Encyclopedia.com Audio versions of the Bobbsey Twins books on Librivox. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Recalling the Bobbsey Twins and Their Fictional Author, “Laura Lee Hope” appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

Beverly Cleary, prolific author of children’s novels

Beverly Cleary (April 12, 1916–March 25, 2021) was an American author of children’s and middle-grade fiction. Extraordinarily prolific and beloved by young readers worldwide, sales of her books have exceeded 91 million copies, and many are still in print.

Starting with the series featuring Henry Huggins and his dog Ribsy in 1950, she went on to create many unforgettable characters, including Ramona Quimby and Ralph S. Mouse.

So, how does a person go from living on a humble little farm in an obscure town in the Pacific Northwest to someone who had an undeniable flair for creating books that generations of children have loved to read? Let’s start finding out.

Childhood and early education

Born Beverly Atlee Bunn in McMinnville, Oregon, until the age of six she lived on the family’s farm in Yamhill just a few miles from her birthplace. An only child, Beverly loved roaming freely about on the farm, eating apples in the shade of the apple tree, watching her father milk the cow and the farmhands thresh the wheat, helping her mother bring in the cow, and gathering wildflowers.

Yamhill lacked a library. Mrs. Bunn took it upon herself to acquire some borrowed space in a building downtown, organize fundraisers, and procured children’s books from the state library in Salem in order to build Yamhill’s first, much-needed library.

Beverly loved listening to the books being read to her and the pictures in the stories. There were so many children’s books available at the Yamhill library now, Mrs. Bunn begged Beverly to let her teach her to read, but Beverly wanted to wait and learn to read in school with the other children, rather than in her mother’s kitchen.

By the time Beverly was six years old, the family farm fell deeply into debt. The Bunns moved to Portland, where Beverly’s father got a job at a federal reserve bank as a night guard. First grade was going along well for Beverly until she contracted chickenpox and missed more than a week of school.

Upon her return, not only did she fail to receive any more of the gold stars she was used to getting for her schoolwork, she began to fail miserably at reading. Her teacher was becoming mean enough to make her fear going to school. Beverly caught smallpox from a neighbor, missed even more school, and grew hopeless at reading. Her mother continued to read aloud to her and encouraged Beverly to choose the stories she wanted to hear.

Beverly disliked reading and it wasn’t until the third grade when, according to her biography, A Girl from Yamhill, she:

“… picked up The Dutch Twins by Lucy Fitch Perkins planning to look at the pictures and I discovered that I was reading and enjoying what I read! It was a miracle. I was happy in a way I had not been happy since starting school. I read all afternoon until I had finished the book. Then I read The Swiss Twins. For once mother postponed bedtime, until I finished the book.”

From then on, Beverly Bunn read countless books for pleasure, to combat boredom, for escape, to kill time while waiting for the rain to cease, and to learn about all matter of things from animals to people and everything in between. Over the next decade or so, some of her favorite stories would include Les Miserables as it was told to her seventh-grade healthy living class by a teacher apparently bored with the standard curriculum, along with Peter Pan, Tom Sawyer, and Jane Eyre.

In the seventh grade, Beverly had a reading teacher who would inspire her to become a librarian and a writer. Miss Smith was the first teacher to allow the students to read for enjoyment (without answering questions about the books, etc.) and a kind librarian who let Beverly into the library first on the days St. Nicholas Magazine³ was delivered.

A popular publication for children that launched in 1873 (Mary Mapes Dodge was its first editor), it was filled with stories, illustrations, and information of interest to children of all ages. To get an idea of what inspired Beverly Bunn, open the link below, click on the thumbnail, select “images” above Material Information.

The effects of the Great Depression were felt by the Bunn family in Portland, much like millions of other families at home and abroad. Adjustments and sacrifices were made by all. Beverly’s father lost his job and her mother picked up work by cold calling from their living room. They had to sell their car, the tension was thick, and laughter was a memory, as she recalled in My Own Two Feet: A Memoir. Somehow, the family muddled through.

. . . . . . . . .

Beverly in 1938, as a senior in college

. . . . . . . . .

Beverly turned eighteen in 1934 and moved to California to attend Chaffey Junior College. Eventually, she would go on to complete her master’s degree at the University of California at Berkeley. She had worked her way through college and began to date the man who would become her husband, Clarence Cleary.

Although it was a tradition, in that era, for women to attend college to catch a man, that wasn’t Beverly’s motivation for getting an education. She wanted to be able to stand on her own two feet. She wanted to accomplish her dual goals; earning a librarianship degree and writing books. Catching a man was left to chance, as it were. She planned to work for a year after college before getting married.

Beverly attended the school of librarianship at the University of Washington in Seattle and upon graduation took a job as a children’s librarian in Yakima. She soon discovered the local boys weren’t interested in reading the books available to them, as they often asked her where to find the books about “kids like us.”

Beverly turned this into something of a personal quest. She spent hours memorizing stories from books for a lively retelling during story hour in the library and, during the summer, in the park. All told, Beverly memorized a total of sixty-two stories during her time in Yakima, The Five Chinese Brothers by Claire Huchet Bishop being the most popular among them.

Marriage to Clarence Cleary, and starting to write

On October 6, 1940, almost a year to the day after beginning her job in Yakima, Beverly Bunn headed to California to marry Clarence Cleary. When she left Yakima, the head librarian commented that she didn’t understand why the children liked her so much. But the secret was that she treated them with respect, just as she treated adults.

Beverly embraced her role as a housewife and spent the first holiday season working at a bookstore. With the murmur of war on everyone’s lips, the Cleary’s decided against starting a family, as Clarence could be drafted despite his high draft notice number. Beverly began working at a library position for the Army, a job she held until the end of the war.

Post-war, the Clearys moved to Berkeley and Beverly found herself staring at her typewriter with nothing to say. She’d always known she wanted to be a writer and, hoping that someday she’d have life’s necessities taken care of, the opportunity to write would finally present itself. The problem was she didn’t know what to write.

Thank goodness Beverly had a great imagination! After waiting and planning for the time to write for nearly twenty years, without ever having written a word of fiction, she recalled the children in the Yakima library who wanted to read stories about “kids like us.” Now age thirty-three, she thought of the kids on her street in Portland riding skates and playing along Klickitat Street.

Though she was unsure of how to begin writing, once she did, she had a knack for telling an interesting story — and so, the world of Henry Huggins was born. Thanks to her imagination, dreams, and goals, when she finally did start to write, the stories poured from her with such ease that was able to skip the typical long rejection process.

. . . . . . . . .

Beverly and friend, around 1955

. . . . . . . . .

Beverly’s years as a children’s librarian proved useful in stepping into her writing career. She had a firm handle on what children enjoyed reading. Her first book, Henry Huggins, was published in 1950 and became the first in a long-running series about the boy and his dog, Ribsy.

Henry’s neighbor girls, Beezus and her younger sister Ramona, soon became stars in a series of their own. Beezus and Ramona was the title of the first of the books about the Quimby sisters, published in 1955. The last of her novels for children, Ramona’s World, was published in 1999.

In between, dozens of books were published, both as part of these series and outside of them. Some of the best known include several books about Ralph S. Mouse, starting with The Mouse and the Motorcycle, and the critically acclaimed Dear Mr. Henshaw, a stand-alone chapter book for middle grade.

Beverly Cleary also produced two memoirs. A Girl from Yamhill (1888) covered her childhood, and My Own Two Feet (1995) detailed her college years and young adulthood. She was an author who very much enjoyed her career. In a 2011 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Beverly, then 95 years old said, “I’ve had an exceptionally happy career.” Beverly Cleary was just three weeks shy of her 105th birthday when she passed away in March 2021.

. . . . . . . . .

Beverly Cleary page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Beverly Cleary’s books have been enjoyed by generations of children, with her gift for writing books that children wanted to read. Her books have been translated into twenty-nine languages, have sold, as mentioned, more than 91 million copies, and received numerous awards, including the prestigious John Newbery Award in 1984 for Dear Mr. Henshaw.

Her books are considered culturally significant for depicting everyday details of middle-class American childhood in a humorous yet respectful way. Here are some comments from literary critics:

“Cleary’s books have lasted because she understands her audience. She knows they’re sometimes confused or frightened by the world around them, and that they feel deeply about things that adults can dismiss.” (Pat Pfliger, professor of children’s literature)

“Cleary is funny in a very sophisticated way. She gets very close to satire, which I think is why adults like her, but she’s still deeply respectful of her characters—nobody gets a laugh at the expense of another. I think kids appreciate that they’re on a level playing field with adults.” (Roger Sutton, Horn Book magazine)

“Cleary’s books are addictive for young readers. Learn to read just well enough, and off you go, like Ralph S. Mouse going pb-pb-b-b-b and zooming down the hallway of the Mountain View Inn.” (Sarah Larson, The New Yorker)

“When you’re the right age to read Cleary’s books you’re likely at your most impressionable time in life as a reader. Her books both entertain children and give them courage and insight into what to expect from their lives.” (Leonard S. Marcus, children’s literature historian)

. . . . . . . . . .

Selected books for children

This is a partial list of books by this very prolific writer. Link through for a complete bibliography.

Henry Huggins series (1950 – 1964)

Henry Huggins (1950)Henry and Beezus (1952)Henry and Ribsy (1954)Henry and the Paper Route (1957)Henry and the Clubhouse (1962)Ribsy (1964)Ramona series (1955–1999)

Beezus and Ramona (1955)Ramona the Pest (1968)Ramona the Brave (1975)Ramona and Her Father (1977)Ramona and Her Mother (1979)Ramona Quimby, Age 8 (1981)Ramona Forever (1984)The Ramona Quimby Diary (1984)Ramona’s World (1999)Other well-known books (selected)

Ellen Tebbits (1951)Otis Spofford (1953)The Mouse and the Motorcycle (1965)Runaway Ralph (1970)Ralph S. Mouse (1982)Dear Mr. Henshaw (1983)Memoirs

A Girl from Yamhill (1988)My Own Two Feet (1995)More information

Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads 100 Things You Might Not Know About Beverly Cleary Beverly Cleary, Age 100 (The New Yorker) New York Times obituary. . . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Beverly Cleary, prolific author of children’s novels appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

December 13, 2021

Her First Time: Seduction and Loss of Innocence in 1920s Women’s Novels

How was seduction, loss of virginity, unplanned pregnancy, unbidden passion, and occasional betrayal portrayed in English and American novels of nearly one hundred years ago? This sampling of seduction and loss of innocence in 1920s women’s novels — by women authors — is fascinating and illuminating.

Here we’ll explore works by Vera Caspary, Viña Delmar, Ellen Glasgow, Edna Ferber, and Rosamond Lehmann. Excerpted from the forthcoming A Girl Named Vera can Never Tell a Lie: The Novels of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth. Reprinted with permission.

. . . . . . . . .

Music in the Street by Vera Caspary (1929)