Nava Atlas's Blog, page 35

September 24, 2021

Women’s Spiritual Journeys in Literature (and Life) Inspired by the Sea

This musing on women’s spiritual journeys inspired by the sea is excerpted from the essay “Women Who Swim” by Evan Atlas. Featuring the iconic real-life swimmer Gertrude (Trudy) Ederle, it moves into parallels with Marian Taylor in The Unicorn by Iris Murdoch, and Edna Pontellier in The Awakening by Kate Chopin:

The sea appears as this powerful source of perfection and self-transcendence in The Unicorn by Iris Murdoch (1987), whose character, Marian, is the subject of a sea-inspired spiritual journey. She arrives in an unfamiliar setting, immediately noticing that something is off:

“She found the vast dark coastline repellent and frightening. She had never seen a land so out of sympathy with man.”

She is to stay at a castle called Gaze (a symbol of Land, Order, Man — especially in the Gothic fiction Iris Murdoch draws from, with modern parallels in stories like Sleeping Beauty), to be a companion to another woman, Hannah, who never leaves the castle. Soheila Farhani Nejad writes:

“The name ‘Gaze Castle’ places a double emphasis on the idea of entrapment. As the staple architectural enclosure for Gothic fiction, the castle typically incarcerates its inhabitants or any character who enters it. The psychoanalytic notion of ‘the gaze’ as developed by Lacan, can be used to describe the way Hannah’s entrapment in Gaze empowers the onlookers while it signifies Hannah’s ‘otherness.’ As the lady of ‘the Gaze Castle,’ Hannah is the target of everybody’s obsessive ‘gaze’…

Almost everyone in the novels treats her as a beautiful object. She seems to exist for the purpose of satisfying the other characters’ idealistic fantasies and their delight in myth and legend … Projection of male fantasies on women is a recurrent theme in Murdoch’s fiction. This often leads to the loss of individuality on the part of female characters… That is to say that in these novels, the male power figures pose as romantic lovers who impose their own notions of ideal feminine identity on their victims.”

It’s important, therefore, that Marian questions her hosts about the sea, but is warned away from it:

“‘Are there good places to swim?’ said Marian. ‘I mean, can one get down to the sea?’

‘One can get down to the sea. But no one swims here.’

‘Why not?’

‘No one swims in this sea. It’s far too cold. And it is a sea that kills people.’

Marian, who was a strong swimmer, privately decided to swim all the same.”

From the moment of her arrival, her existence, agency and spiritual potential are eroded by men or male-coded symbols like Gaze itself. She ventures out to the sea anyway, but is overwhelmed by it:

“She did not know what was the matter with her now. The thought of entering the water gave her a frisson which was like a kind of sexual thrill, both unpleasant and distressingly agreeable. She found it suddenly hard to breathe, and had to stop and take deep regular breaths. She threw her bag down on the sand and advanced to the edge of the sea… It was a matter of pride; and she felt obscurely that if she started now to be afraid of the sea she would make some crack or fissure in her being through which other and worse fears might come.”

Through the rest of the novel, she does not return to swim in the sea. The Castle Gaze and its garden (a symbol of Nature restricted by Man) assert themselves over Marian — removing her from contact with the sea, with her potential source of wholeness:

“The garden was thick and magnetic behind her. Her desire to go out was gone. She was afraid to step outside.”

In the symbol-story complex, this is a warning not to lose touch with the those things which are sources of spiritual power. The estrangement can become permanent through an extended impoverishment of self-transcendence.

. . . . . . . . .

Analysis of The Awakening by Kate Chopin

. . . . . . . . .

In another woman’s dramatic encounter with herself, Edna Pontellier, the heroine of The Awakening by Kate Chopin (1899) is spiritually transformed by the sea, yet experiences social powerlessness. Like Murdoch’s story, it is a conflict of the social and spiritual quests, which we must now reconcile.

Not just for women, who can come into closer contact with more perfect versions of themselves, but in turn for us all, who until then suffer a society which is less than what we know it could be. Carol P. Christ observes in Diving Deep & Surfacing: Women Writers on Spiritual Quest:

“Edna’s suicide is a spiritual triumph but a social defeat. In it she states, even if only partially consciously, that no one will possess her body and soul, and affirms her awakening by returning to the sea where it occurred … But Edna’s suicide is also a social defeat in that by choosing death she admits that she cannot find a way to translate her spiritual awareness of her freedom and infinite possibilities into life and relationships with others. From this stand-point the real tragedy of the novel is that the spiritual and social quests cannot be realized together.”

Therefore, we can live in one of two worlds. In the first, “spirituality” makes women and girls think of religion in the sense of a patriarchal God. “Self-transcendence” sounds like something a charming cult leader would want you to do. And swimming is just one of the low-prestige sports women can participate in while men are honored and paid disproportionately for their athletics. Nobody in this world would have any reason to think that swimming had a deeper significance to women’s social-spiritual quest.

Alternatively, we can live in a world in which our symbol-story complex feeds forward, giving meaning to experiences like swimming in the sea. And the ritual of swimming-to-self-transcend feeds back to our stories and symbols. In this mutual strengthening, swimming becomes the radical act of asserting the need for a society with both justice and enlightenment.

. . . . . . . . .

Gertrude “Trudy” Ederle,

the first woman to swim the English Channel (1926)

. . . . . . . . .

It is both self-evidently beautiful and highly practical. All we need is a less haphazard approach — to bring the connection between swimming and social-spiritual growth to the surface. A young Trudy Ederle, in this world, would tell people how she loved the sea, and felt at one with it, and there would be people around her (parents, teachers, etc.) who could help her connect the dots.

The symbol-story complex would complement her joy of swimming and turn it into something greater, more significant. She would learn to connect it to the spiritual quest, which she understands as the sister-struggle of women’s social quest. This is why the “strong swimmer” like Marian in fiction or Gertrude Ederle in real life, is an archetype of spiritual fulfillment.

Women who dive and surface become more fully themselves, and with this inner strength they are more capable of extending enlightenment to others and advancing the social causes which affect us all, and women most acutely. And a stronger social movement, continuing the feedback loop, creates conditions for women to direct more attention beyond basic needs and towards greater wholeness.

Read the full essay, “Women Who Swim” here.

Contributed by Evan Atlas. Evan is a writer and political philosopher from New York’s Hudson Valley. His work confronts our most significant challenges, and develops a theory of change for the 21st century that is unlike anything you’ve heard before. He believes that the future of humanity can be more loving, more free, and more beautiful, but that this future is in danger. Join him at evanatlas.com and help create a more beautiful planet.

. . . . . . . . .

You might also like:

The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch

The post Women’s Spiritual Journeys in Literature (and Life) Inspired by the Sea appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 17, 2021

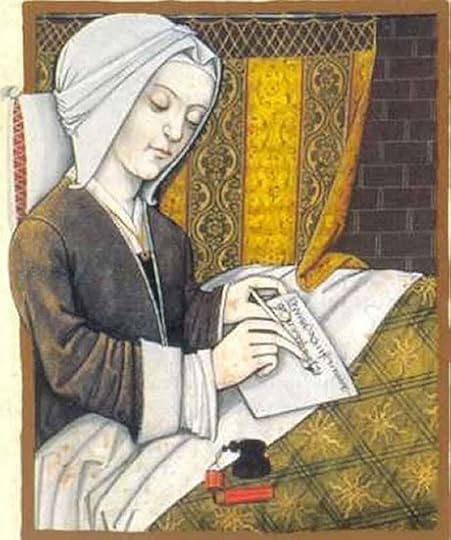

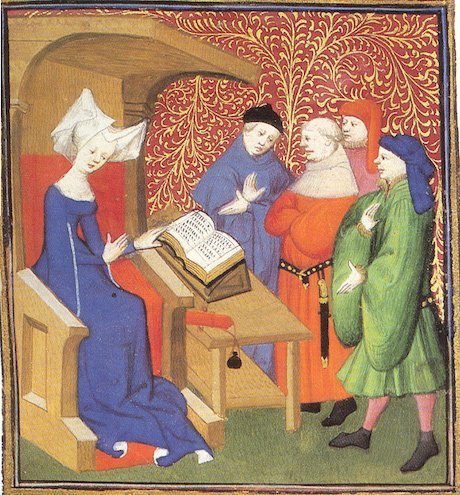

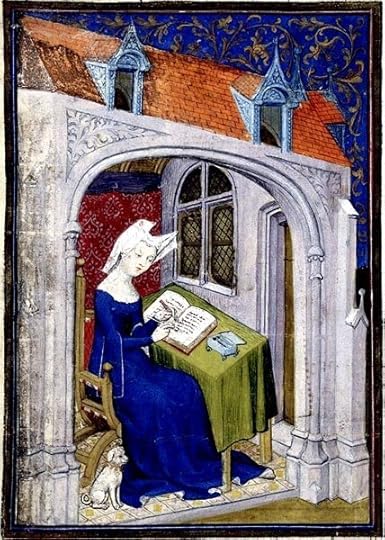

Christine de Pizan and The Book of the City of Ladies: An Introduction

Christine de Pizan (1364 – 1430) the French writer, is best known for her seminal work of literature by, about, and in support of women, Le Livre de la Cité des Dames (1405). Now known as The Book of the City of Ladies, it was first translated into English as The Boke of the Cyte of Ladyes and published in London in 1521, “in Paul’s churchyard at the sign of the Trinity by Henry Pepwell.”

This introduction to Christine de Pizan and The Book of the City of Ladies is excerpted fromKilling the Angel: Early Transgressive British Woman Writers by Francis Booth ©2021, reprinted by permission.

Pepwell’s printers in St Paul’s Churchyard published many of the new humanist works along with works of mysticism. In its English version, Christine’s message was well-timed and found a more receptive audience in Tudor Reformation England where printed books in English were leading to greater levels of education among women and creating in turn an appetite for books addressing women in English – Tyndale’s English language New Testament reached England in 1526.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

“Here beginneth the book of the city of ladies, the which book is divided into three parts. The first part telleth how and by whom the wall and the cloister about the city was made. The second part telleth how and by whom the city was builded within and peopled. The third part telleth how and by whom the high battlements of the towers were perfectly made, and what noble ladies were ordained to dwell in the high palaces and high dungeons.”

Like Julian of Norwich (see more about her in 5 Early English Women Writers to Discover), Christine was a nun who wrote to help women defend themselves against the world of men, though Christine only entered a convent for her own safety later in life after civil war broke out in France; for most of her life she was a professional writer.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

France’s first woman of lettersVirginia Woolf considered Aphra Behn to be the first professional woman writer but Christine, who is considered to be France’s first woman of letters also has a claim to the title. She wasn’t a professional writer in the modern sense of making money from selling books – there would not be any printed books for sale for a long time – her income came from wealthy patrons.

Transgressing the norms of medieval society, Christine wrote treatises on government and public affairs as well as the role of women in society; she also wrote poetry which included much autobiographical information, very unusual in an age when most poets rewrote traditional, impersonal courtly and romantic tales.

The Book of the City of Ladies, was written in response to some of the misogynist works of the time, especially the great mediaeval epic The Romance of the Rose. Christine tells how she a read a book:

“… which made me wonder why on earth it was that so many men, both clerks and others, have said and continue to say and write such awful, damning things about women and their ways. I was at a loss as to how to explain it. It is not just a handful of writers who do this … It is all manner of philosophers, poets and orators too numerous to mention, who all seem to speak with one voice and are unanimous in their view that female nature is wholly given up to vice.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Killing the Angel

on Amazon US*

Killing the Angel

on Amazon UK*

. . . . . . . . .

Christine claims to have had a vision from three ladies, “crowned and of majestic appearance.”They are Reason, Rectitude, and Justice, who have come to help her build a city in which women can live in safety and security. “The female sex has been left defenseless for a long time now, like an orchard without a wall, and bereft of a champion to take up arms in order to protect it.”

“We have come to vanquish from the world the same error into which you had fallen, so that from now on, ladies and all valiant women may have a refuge and defence against the various assailants, those ladies who have been abandoned for so long, exposed like a field without a surrounding hedge, without finding a champion to afford them an adequate defence, notwithstanding those noble men who are required by order of law to protect them, who by negligence and apathy have allowed them to be mistreated.

It is no wonder then that their jealous enemies, those outrageous villains who have assailed them with various weapons, have been victorious in a war in which women have had no defence. Now it is time for their just cause to be taken from Pharaoh’s hands.”

The three ladies tell Christine a large number of stories, which make up the bulk of the book, about famous and admirable women from history in various categories such as learning, invention, poetry, warfare and so on. This is a marvelous and exhaustive catalogue of transgressive, powerful woman from before the Middle Ages. Having built the city with all these exemplary women inhabiting it, Christine invites women to enter it.

“Most excellent, upstanding and worthy princesses of France and other countries, as well as all you ladies, maidens, and women of every estate, you who have ever in the past loved, or do presently love, or who will in the future love virtuous and moral conduct: raise your heads and rejoice in your new city.”

The principal resident of the new city and its supreme monarch will be the Virgin Mary, “she, in her humility, which surpasses that of all other women, coupled with her goodness, which is greater than that even of the angels, will not refuse to live in the City of Ladies. She will reside in the highest palace of all.”

At the age of forty Christine had written at least nineteen books, some of which were on public policy, advocating peace, and addressed to the king and the nobles of France in a transgressive tone which even most men would have been afraid of adopting.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Book of the City of Ladies on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

She then wrote a sequel to the Book of the City of Ladies called, confusingly Treasure of the City of Ladies. This is very different from its predecessor, being more of a practical manual for virtuous living; it is almost a religious etiquette manual aimed at princesses and noble women, though it still purports to be inspired by the same three ladies.

“From us three sisters, daughters of God, named Reason, Rectitude and Justice, to all princesses, empresses, queens, duchesses and high-born ladies ruling over the Christian world, and generally to all women: loving greetings.”

More than its predecessor, the book advocates, above all, that women should be faithful to God. Christine addresses all the issues facing wealthy women at all stages of life and constantly advocates modesty, prudence and harmony; she never advocates any form of transgressiveness, despite her own background.

“Do not be proud of yourselves, but always be meek, and by holding to this course you can drive your chariot up to the farthest reaches of glory that Almighty God bestows upon you.”

The nearest she comes to advocating transgression is in relation to a bad husband: although she stresses that a married woman should love her husband, care for him and live in peace with him, not all husbands deserve to be obeyed.

“But some may perhaps answer us here that we are not taking into account certain defects and that we are talking utter nonsense. They may argue that we are saying that come what may ladies ought to love their husbands very much and show the signs of it, but that we are not saying anything about whether they all deserve to be treated so well by their wives.

It is well known that there are some husbands who behave very distantly towards their wives and give no sign of love, or very little. We reply to them that our teaching in this present work is not addressed to men, although some of them need it if they would be well instructed. Because we speak so exclusively to women, we set out for their profit both to teach the valuable methods of avoiding dishonour and to give good advice for following the right course of action.”

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Christine de Pizan and The Book of the City of Ladies: An Introduction appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 15, 2021

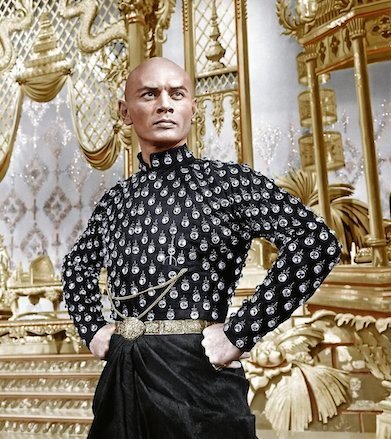

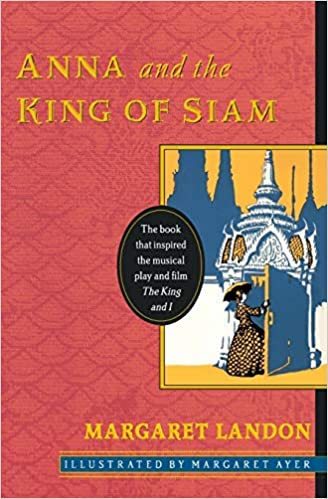

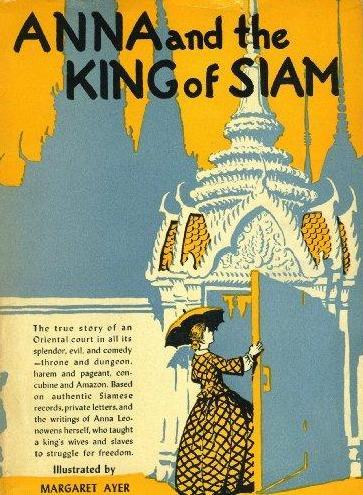

Marching Through the Years: Revisiting Anna and the King of Siam

When I was a girl, the only parts of grown-ups’ movies that I enjoyed were the parts with children in them. So, the first few times I watched the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical (based on the 1944 book Anna and the King of Siam by Margaret Landon) The King and I, only “The March of the Royal Siamese Children” appealed to me.

As an only child, families with more than one child seemed remarkable; the seemingly endless stream of offspring, parading through the court in this colorful musical number, fascinated me. And I was oblivious to the number of grown women—the mothers—also in attendance, felt no compulsion to multiply by nine, or to muse on multiple conceptions.

As a teenager, I accepted my discovery of Margaret Landon’s Anna and the King of Siam as the “true story,” just as I accepted that The Sound of Music was based on the well-worn paperback copies of ’s memoirs that had long resided in my grandmother’s bookshelves. This is to say that I understood, in theory, there were real-life figures behind these musicals, but I preferred the song-and-dance inventions.

A construction of a construction

Had I read the author’s note at the end of Margaret Landon’s narrative (though I likely dismissed it as the kind of thing one read for “homework,” not for fun), I would have realized that Anna’s story was not being chronicled directly even there—that Margaret was constructing a story about Anna’s life based on Anna’s previous construction.

Margaret first became fascinated by Anna Leonowens’ (1831–1915) 19th-century experiences teaching in Siam when she herself taught there several decades later. A family friend loaned her copies of Leonowens’ memoirs—The English Governess at the Siamese Court (1870) and The Romance of the Harem (1872)—which were difficult to obtain given the Siamese government’s disapproval of some of Leonowens’ characterizations.

This is how Margaret describes her friend Dr. McDaniel’s introduction to the works in her author’s note:

“Here’s something you ought to read. The Siamese government did everything in their power to keep it from being published. I’ve been told they even tried to buy the whole edition to prevent its distribution. In fact there has been so much feeling against the book that I still keep my copy out of sight, just to be on the safe side.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Anna Leonowens (1831 – 1915)

. . . . . . . . . .

After the Landon family returned to the U.S.and Margaret located personal copies of the books, she began to study Anna in detail. But she found it impossible to reassemble her narratives completely and sequentially, even after eliminating much of the description and heavily detailed material, so she proceeded with a third-person narrative: “seventy-five percent fact, and twenty-five percent fiction based on fact.”

Both Anna Leonowens’ The English Governess at the Siamese Court and Margaret Landon’s Anna and the King of Siam open in 1862, onboard a steamer docking in Bangkok. Both writers are concerned with setting a scene, with inviting readers into an unfamiliar space, but even the first dozen pages reveal the stark difference in style, content, and perspective.

Anna immediately focuses on the sunrise, which she admires on deck, then shifts to descriptions of flora and fauna, the river and fishing industry, and the islands and architecture visible from her perspective. From her “early glimpse of this strange land,” it is the land she seeks to display, along with the culture of that land’s inhabitants, including some native language.

The human-interest elements (dogs and circus personnel), and the emotional details surrounding uncertainty about her accommodations, pique readers’ interest, but Anna’s personal record is more travelogue than entertainment.

Margaret begins with the circus and the dogs, then quickly puts Anna in the spotlight: her clothing and hairstyle, her bearing and tone, her reassurance to her son about their journey’s end. Anna is the story: after a deftly sketched scene that showcases her courage and conviction, she prepares to leave the ship. Margaret then ventures into material unrecognizable from Anna’s memoir.

Contextualizing Anna

In Margaret’s research, she initially lacked context for Anna’s actual experiences beyond her publications. And although Margaret found Anna’s “long descriptions far from dull,” she recognized that not everyone shared her interest in South Asia. She hoped to “piece together” Anna’s “own writings without alternation in language or style,” and depend upon her personal experience of Siam and its history to more swiftly engage western readers.

Then, in 1939, Margaret’s access to information broadened when she attended a luncheon with her husband, whose mission work had originally taken the couple to Siam. One of the other ministers in attendance, who was familiar with the couple’s work there, mentioned to Margaret that his mother would love to discuss a long-ago correspondence that she had had, years before, with another woman who had also taught there.

Gerald Gratton Moore’s mother had not only corresponded with Anna Leonowens, but she was able to connect Margaret Landon with Anna’s granddaughter, Miss Fyshe, then living in Montreal. The documents that Miss Fyshe possessed included an account that Anna had prepared to describe her pre-Bangkok years.

Margaret’s second chapter veers into fresh territory and casts a backward glance at what Anna describes as youthful experiences in Wales and India. Margaret understood these to have prepared Anna for travels far from her home. With these additional materials, Margaret was able to develop her fictionalized version of a strident teacher, whose integrity and faith could serve as an example for American women in wartime and beyond.

These materials, however, were described by biographer Alfred Habegger as a “publicity release,” though Margaret could not have known they were “utterly unreliable.”

Developing a personal vision

Though Margaret was dedicated to research and accuracy, she fundamentally trusted Anna’s recounting of events and became increasingly committed to her personal vision of Anna. Even in the face of editorial doubts, for instance, Margaret insisted that Anna’s religiosity remain prominent in the story. She doubled down on elements of the imagination that presented Anna as a valiant and worthy heroine.

Habegger, for instance, refers to the evolution of Margaret’s drafts, which widened the gap between the characters of Anna and the King of Siam. “Loyalty to the one meant defacement of the other,” he explains. Above all, Margaret was loyal to her view of Anna as an infallible heroine.

In an early draft, Habegger observes, Margaret paraphrases Anna in her description of King Mongkut (the ruler of Siam from 1851 to 1868), who “in many grave considerations displayed a soundness of understanding and clearness of judgment, a genuine nobility of mind, established on ethics and philosophic reason, that were wholly admirable.”

Habegger observes that “nothing resembling the sentence” remains in the published volume, however; ultimately “paraphrase had yielded to fiction” and “gone…was the respect for Mongkut’s intellectual character.”

For me, as a young viewer, it was all about Anna. Once the adults began to interest me, Anna occupied the heart of the story (largely because of her hoop skirts but also the sentimentality of the film’s ending!) but, over the years, the King captured my interest.

. . . . . . . . . .

Yul Brynner, 1956. ©20th Century Fox Film Corp. Courtesy: Everett

. . . . . . . . . .

The King who commanded my attention was not the King as presented by Anna or Margaret or the 1946 Twentieth Century Fox dramatic film production (titled Anna and the King, starring Irene Dunne and Rex Harrison). But it was Yul Brynner who would captivate me; he first played the King in the original stage musical in 1951 with Gertrude Lawrence as Anna, then starred opposite Deborah Kerr in the 1956 musical film (Kerr had voiced Anna in the 1949 radio production).

Brynner was also cast in the 1972 Twentieth-Century Fox television series on CBS, based on the film and also titled Anna and the King, opposite Samantha Eggar. It lasted only one season and provoked litigation from Margaret Landon. This perhaps explains why the Twentieth-Century Fox Anna and the King, released in 1999 and starring Jodie Foster and Chow Yun-Fat, was said to have been based on Anna’s writing — not Margaret’s. That same year, Walt Disney released an animated version.

For me, the King is personified by Yul Brynner. In a 1981 interview, Brynner discussed his belief that the story has endured because the figures were based on real people — not stereotypes, but rather, archetypes. The King, he elaborated, is the archetypal father, presented as both dangerous and loving, possessing seemingly contradictory traits, like roughness and innocence.

Although Brynner portrayed the King in both television and film, in the interview he referred to his stage performances—eight per week over many years, and around the world. One moment fascinated Brynner in particular, a moment of violent emotion in which the King’s inherited totalitarian value system conflicts with Anna’s democratic value system. Brynner discussed the evolution of his representation of this internal turmoil.

Even after performing the role thousands, of times, he found new meaning in the King’s contradictions and complexity. And, in the same interview, he agreed that the most moving piece of music is the “March of the Children.” Because, he explained, it represents “respect for the individual human being,” a simple but powerful truth, that children will grow up and become unique individuals.

. . . . . . . . .

Anna and the King of Siam on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

When I was a girl, just beginning to watch this story, I always imagined myself as one of two girls: she who presents Anna with a flower, or she who forgets the court protocol and rushes in for a hug from her father, only to be rebuffed but quickly reassured by a not-quite-concealed playful smirk when she takes her proper place in the court.

Neither of these girls appears in the story as told in Anna Leonowens’ The English Governess at the Siamese Court or Margaret Landon’s Anna and the King of Siam, but were it not for these women’s narratives, I would have had one fewer pantomime to play at in my only child’s repertoire; I would have been doomed to endless hours of “playing” The Sound of Music in Europe’s mountains, without the opportunity to imagine myself as a young princess in Siam.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

Stage and film adaptations of Anna and the King of Siam Anna and the King of Siam (1946 film) The King and I (1951 stage musical)The King and I (1956 film musical)Anna and the King (1972 TV series)The King and I (1999 animated film musical) Anna and the King (1999 film). . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Marching Through the Years: Revisiting Anna and the King of Siam appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 14, 2021

A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1905)— a Timeless Tale

Frances Hodgson Burnett (1849—1924) was a beloved, poet, playwright, and children’s book author. She penned more than forty novels, plays, and dozens of poems and short stories throughout her lifetime. She’s perhaps best remembered as the author of The Secret Garden and A Little Princess, though her prolific output went far beyond these now-classic works.

The story of A Little Princess follows a young girl with a vivid imagination as she faces abandonment at a posh boarding school in London with a cruel headmistress. The novel is an expansion of Burnett’s novella, Sara Crewe: or, What Happened at Miss Minchin’s Boarding School, first published in December 1887.

The riches-to-rags story was so successful that in 1902, Burnett adapted the story of Sara Crewe into a three-act stage play under the title, A Little Un-Fairy Princess. After a successful production of the play on Broadway, Burnett’s publisher urged her to expand the story of Sara Crewe into a full-length novel.

The book was published in September 1905 with the title A Little Princess: Being the Whole Story of Sara Crewe Now Being Told for the First Time. The novel has since been adapted into several film versions, TV shows, musicals, and other theatrical productions.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also like: Quotes from A Little Princess

. . . . . . . . . .

From the 2004 Sterling Publishing edition of A Little Princess: When Sara Crewe first arrived at her private English boarding school, she was treated like a little princess. The richest and best-dressed girl in the school, she was given the prettiest room, her own pony, a maid to wait on her, and the fawning attention of the headmistress, Miss Minchin.

Then news arrives that changes Sara’s life entirely. No more would Sara have nice things and fancy ways. Now she was compelled to work in the school and live as a servant.

But Sarah remains her kind, courageous self. Abused by Miss Minchin and tormented by jealous students, she never wavers in her firm belief in her worth. Instead, Sarah supposes herself a real princess and uses her vivid imagination to make over in her mind her bleak surroundings and even bleaker life.

Throughout her ordeals, she holds her head high and manages to be charitable to those even less fortunate than herself.

One wonderful night the tired and hungry little princess awakens to find her life mysteriously and magically transformed. What brings about the sudden changes, and how they affect the life of this brave and compassionate girl, have readers spellbound for more than a century.

Burnett’s surprising inspiration

It’s worth mentioning that Burnett’s novel has been suspected of being inspired partly by Charlotte Brontë’s unfinished novel, Emma. (not to be confused by the famed novel of the same name by Jane Austen). Only the first two chapters of Brontë’s book were published in 1860.

Brontë’s brief and unfinished novel featured a young, rich heiress abandoned at a boarding school, much like Sara Crewe in A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett.

Best-known film adaptations

of A Little Princess

1939: The second screen adaptation of the beloved novel, produced by 20th Century Fox, was released on March 10, 1939 (the first was the 1917 silent film starring Mary Pickford as Sara). Slightly retitled The Little Princess, it was directed by Walter Lang and starred Shirley Temple as Sara Crewe. The film was the first Shirley Temple movie filmed completely in Technicolor and cost over $1 million in production.

Many lengths were taken to make sure every aspect of the film was true to the story’s setting and time, set in 1899 Britain. Everything from special props made with exact specifications of that time to wardrobes had to be precise. Although strangely enough, the 1939 adaptation introduced several new characters and storylines, and the film’s ending was drastically different from the book.

The film earned an approval rating of 88% on Rotten Tomatoes, with an average rating of 6.6/10. Critical reviews for The Little Princess say that the film features a “heart-tugging Temple with a payoff ending” and an “irresistible Shirley Temple showcase vehicle.”

. . . . . . . . .

1995: The most recent film adaptation of A Little Princess, produced by Warner Brothers Entertainment, was released on May 10, 1995. The film was directed by Alfonso Cuarón and starred Liesel Matthews as Sara Crewe. This adaptation was heavily influenced by the 1939 cinematic version of The Little Princess, but the film takes many of its own creative liberties with Burnett’s original story.

The 1955 film was critically acclaimed and received two Academy Award nominations for its achievements in art direction and cinematography. While not a huge box office success (earning a gross of only $10 million), the film earned an approval rating of 97% based on 35 reviews from Rotten Tomatoes, receiving an average rating of 8.2/10.

The critics’ consensus states, “Alfonso Cuarón adapts Frances Hodgson Burnett’s novel with a keen sense of magic realism, vividly recreating the world of childhood as seen through the characters.” Other critics said the film was, “an exemplary version of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s novel,” and “a bright, beautiful, and enchantingly childlike vision.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Frances Hodgson Burnett books on Bookshop.org*

Frances Hodgson Burnett page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

More about A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett

A Little Princess on Wikipedia Reader Discussion of A Little Princess on Goodreads The Complete Works of Frances Hodgson Burnett A Little Princess on Biblio A Little Princess (1995 film) on Amazon*. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1905)— a Timeless Tale appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 9, 2021

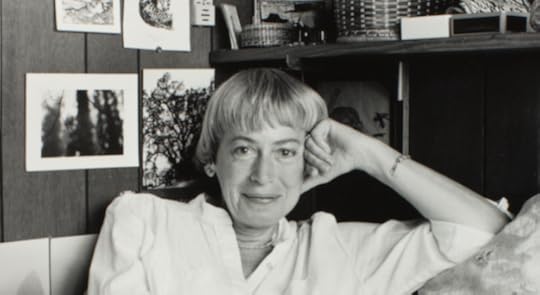

Margaret Landon, author of Anna and the King of Siam

Famed for Anna and the King of Siam (1944), which inspired a variety of adaptations, including the musical “The King and I,” American writer Margaret Landon (September 7, 1903 – December 4, 1993) spent more than a decade studying Siam (now Thailand) and a lifetime writing about it.

Anna and the King of Siam was Margaret Landon’s crowning achievement. It sold over one million copies and has been translated into more than twenty languages. Based on the true story of Anna Leonowens, who served as governess to the King Mongkut, in the 19th century, it introduced Western readers to a world of Asian culture.

Family and Childhood

Margaret Dorothea Mortenson was born in Somers, Wisconsin. Her father, Annenus Duabus Mortenson, was born in Racine, Wisconsin to a Norwegian mother and a Danish father. As a young man, he worked as an office manager in advertising for Curtis Publishing Company in Chicago and, later, in the business department of the Saturday Evening Post.

Her mother, Adelle Johanne Estberg, was born in Franksville, Wisconsin to Danish parents. She didn’t work outside the home until after her husband died in 1925. She then began working as a secretary at a college.

Annenus and Adelle married in 1902 and, after Margaret, had two more daughters: Evangeline, two years younger than Margaret, and Elizabeth, seven years younger.

The Gift of Words

Margaret attended Evanston Township High School in Illinois. Her English teacher there once told her: “You have the gift of words. Do something with it!”

She was also interested in sports, and later served as captain of the women’s baseball, basketball, and tennis teams at Wheaton College, a Christian school in Wheaton, Illinois.

After graduating in 1925, she taught English and Latin in Bear Lake, Wisconsin, an experience she described as “an agonizing year” having “soon discovered that I disliked teaching.”

In1926, she married Kenneth Perry Landon, whom she’d met at college. He was a seminary student, a graduate of Wheaton College and subsequently, Princeton Theological Seminary. The following year he went to Siam, to work as a Presbyterian missionary accompanied by Margaret.

In Siam

After spending most of 1927 and 1928 in Bangkok, where they learned Siamese, the Landons were stationed at Nakhon Si Thammarat and, afterwards, Trang.

Kenneth earned his master’s degree at the University of Chicago in the 1931-1932 academic year but, otherwise, from 1927 to 1937, their missionary work in Siam was all-consuming. Often the Landons were the only non-Siamese people in their environs.

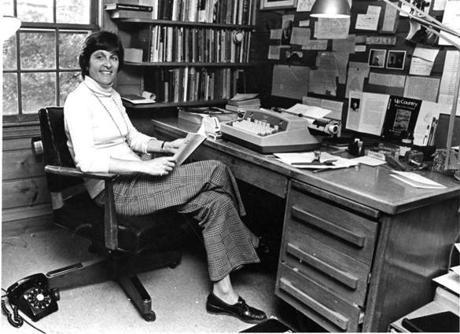

Margaret served as principal of Trang Christian school for girls at her husband’s mission for five years, according to her Washington Post obituary.

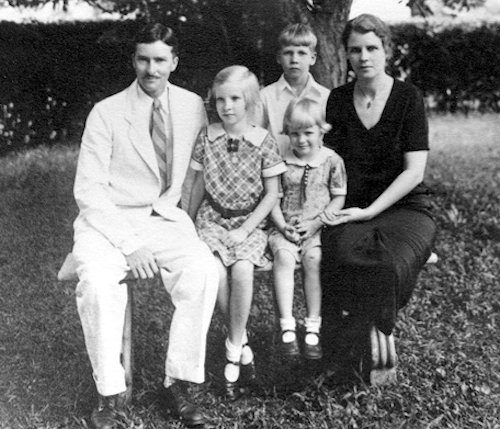

While living in Siam, the couple had three children: Margaret Dorothea, William Bradley II, and Carol Elizabeth. These children learned Siamese before they learned English and were issued passports there. After the couple returned to America, they had one more son, Kenneth Perry, Jr.

It’s understandable that Margaret found little time to write anything beyond the mission newsletter and correspondence but, while in Siam, in 1930, she discovered the story which inspired the novel she would write after the family returned to America.

A family friend, Dr. Edwin Bruce McDaniel, had copies of two books written by Anna Leonowens, a widowed woman who describes traveling from Wales to Siam in 1862—both to teach English to King Mongkut’s many children and his favored concubines and to present Western political ideologies.

Both these volumes—The English Governess at the Siamese Court (1870) and The Romance of the Harem (1872)—were viewed by the Siamese government as disrespectful to the regent and thus banned. Even after the King’s son, Prince Chulalongkorn, became King and abolished the custom of prostration before superiors in the court and freed his slaves (both acts evidence of Leonowens’ influence, she asserted), Anna’s books remained forbidden. But Margaret found her story fascinating.

. . . . . . . . . .

Kenneth and Margaret Landon and their children

. . . . . . . . . .

Back in America, Margaret finally found her own copies of Leonowens’ books, when she visited second-hand bookstores in Chicago. One of her assignments in the night school classes she attended in 1937–38, at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism in Evanston, Illinois, reflected her ongoing interest in the widow’s life story.

Her first published work was a magazine article titled “Hollywood Invades Siam,” inspired by Leonowens’ writing, for which Margaret was paid fifteen dollars.

She began writing Anna and the King of Siam in 1939 in Richmond, Indiana, where her family lived until 1942, when Kenneth began working for the State Department as a southeast Asia specialist in Washington D.C. Kenneth would publish three books himself, all on southeast Asia, as well as numerous articles. In addition, he lectured nationally.

Margaret’s close friend from college, Muriel Fuller, who worked in the publishing industry, encouraged Margaret to combine and rewrite the stories in Leonowens’ books, to reduce the lengthy descriptions and refine the timeline. In July 1943, just a few hours before Kenneth Jr.’s birth, Margaret finished her book.

. . . . . . . . .

Anna and the King of Siam on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

Margaret rewrote some sections of her book as many as twenty times, and her research was meticulous, assisted by her husband’s connections in the State department. Nonetheless, while exploring the story, she didn’t have access to overseas archives and was primarily dependent upon Anna’s published versions of events.

Although two publishers rejected Margaret’s finished manuscript, John Day Company was encouraged by Kenneth Landon’s conversations with key figures there to accept it for publication. John Day had been founded in 1926 by Edwin Walsh, who was married to the novelist Pearl S. Buck. Her writing, including the best-selling The Good Earth (1931), had demonstrated the marketability of western writers’ narratives about Eastern lives.

As biographer Alfred Habegger observes, however, the editor of the publishing house’s monthly magazine (Asia and the Americas) was concerned about the work’s tone. Editor Elsie Weil worked with Margaret to prepare select chapters for publication in the firm’s magazine.

Weil felt it smacked “a little too much of juvenile Sunday school literature.” In fact, Margaret had relied on Anna’s published children’s stories for particular scenes; she also remained committed to Anna’s “deep religious feelings” and believed they were essential to the story.

Walsh instructed Margaret: “Stick as closely as possible to recorded facts. But no doubt you have to invent or reconstruct in many places.” What Weil called the “fictionizing” of the piece was a way to engage readers but, ultimately, the work was published as a biography.

As time passed and more complex Eastern stories were made available to Western readers, Margaret’s imaginative flair would come to overshadow her scholarly intentions. Margaret dedicated the book to her younger sister Evangeline, who had been killed in a car crash in 1941. The book became a best-seller and was also distributed to WWII troops in an Armed Services Edition.

. . . . . . . . . .

Cover of the original UK edition

. . . . . . . . . .

Margaret struggled to continue writing. In 1946, a serious bout with rheumatic fever interfered with her work for two years. She published Never Dies the Dream in 1949, a novel, also with substantial detail about Siamese life. The story told of a missionary running a school in Bangkok in the 1930s, whom Habegger describes as an “honest, idealistic, white American woman”—but it wasn’t as successful as The King and I.

Staying with her perceived expertise, Margaret shifted to non-fiction and began compiling a textbook for high school students on Southeast Asian history.

According to her Washington Post obituary, Margaret’s poor health and family responsibilities are cited as reasons for her slowed writing output. She is described as having “entertained foreign dignitaries” and being a member of “such groups as the Literary Society.” Her textbook, Pageant of Malayan History, remained unfinished.

Death and Legacy

Landon died after a stroke on December 4, 1993 in Alexandria, Virginia, in the Hermitage Retirement Home. Her husband had died there earlier that year, and the couple are now buried together in Wheaton Cemetery in Illinois.

The original manuscript of Anna and the King of Siam and related material is housed in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. The rest of the Landons’ papers are in the Special Collections Department of Wheaton College. Personal papers, correspondence, other manuscripts, and dozens of CDs of oral history interviews with Margaret and Kenneth fill 348 boxes there.

Anna and the King of Siam sold over one million copies and has been translated into more than twenty languages. Through Landon’s work, many Westerners who lacked experience with Eastern culture and society gained some understanding.

It seems unlikely that Leonowens’ memoirs would have remained available without Landon’s interest in her life and work. Biographer Susan Morgan notes that Margaret’s novel “introduced Thailand, which is to say, Margaret and Ken’s vision of Thailand, to the American people.” And it further inspired retellings on film, stage, radio and television.

The best-known adaptation was the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I, which opened on Broadway on March 29, 1951. It starred Gertrude Lawrence and Yul Brynner, The show had a budget of $250,000, which was the largest Rodgers and Hammerstein production at the time. It continues to charm audiences and is regularly and enthusiastically revived on stages around the world. As recently as 2015, a Broadway revival won a Tony Award.

The 1956 film based on the musical, with Deborah Kerr playing Anna, with Yul Brynner reprising his stage role as the King, was tremendously popular and critically acclaimed. Also titled The King and I, it was nominated for nine Academy Awards and won five. Songs like “Getting to Know You” and “Shall We Dance” wound their way into repertoire albums for decades to come.

There were several other film and television adaptations both before and after the stage and screen versions, none as successful or iconic.

Just as Anna Leonowens transformed her personal history and reinvented herself through the narratives she published during her lifetime, Margaret Landon reimagined Anna’s life on the page. Others reimagined those stories on the stage and screen. Multiple interpretations of compelling stories remind us of the power of narrative to open us, as readers, to new worlds of experience.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

More about Margaret LandonMajor works

Anna and the King of Siam (1944)Never Dies the Dream (1949)Stage and film adaptations

Anna and the King of Siam (1946 film) The King and I (1951 stage musical)The King and I (1956 film musical)Anna and the King (1972 TV series)The King and I (1999 animated film musical) Anna and the King (1999 film)More information

Margaret and Kenneth P. Landon Papers at Wheaton College Reader discussion on Goodreads New York Times Obituary. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Margaret Landon, author of Anna and the King of Siam appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 6, 2021

An Analysis of The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin (1974)

Ursula K. Le Guin is one of the most influential science fiction and fantasy writers of the twentieth century. Her 1974 novel, The Dispossessed, was written as a political tale, with themes that include freedom and the corruption of capitalist societies. It won the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus awards in 1975.

Le Guin uses her novel as a moral principle of anarchism based on political theories and ideas of collective societies to challenge modes of radical thinking. Discussing these philosophies will determine if she was successful in delivering a convincing narrative that overcomes conflicting notions of a perfect society

A concept of oppositesLe Guin uses a concept of opposites with the use of two planets to write of a society governed by principles free from state rule on the planet Anarres. She compares that with a capitalist regime on the planet Urras. Le Guin created the planet Anarres intending to promote what she deemed to be new ideas, where water and heat would be rationed and where nothing goes to waste.

Everything was to be recycled and they would use the wind to generate energy. All this may sound rather familiar, as some of the ideas that Le Guin posits were already in existence when she wrote her story. The oil shortages of the 1970s changed the energy environment for the world. It was because of this, those alternative ways of using energy sources were developed such as wind energy which had been around for thousands of years beforehand.

The same is true of recycling, which was also in existence since the early nineteenth century. Le Guin wasn’t exploring anything that wasn’t already being utilized in this world, let alone another world. However, the following quote from her book could be a possible foreshadowing of recent events that have occurred in our world where she describes the whole planet as “a great prison camp, cut off from other worlds and other men, in quarantine.” (3)

. . . . . . . . . .

Ursula K. Le Guin

. . . . . . . . . .

Unfortunately, Le Guin’s ideas were not fresh or new at the time of her writing the novel and her imagined planet of Anarres isn’t without some serious issues. Not least of all that she describes it as “a barren sixty-acre field . . . a place where nothing grows.” (4)

However, without any grass there would be no herbivores, without herbivores, there are no carnivores, nor insect or plant life. Thus far, Anarres isn’t promoting the congeniality intended, which is to foster sharing and equality.

In an ideal world where everyone is on the same level; a life without hierarchy may seem an attractive option. Unfortunately, these ideas tend to develop a lack of focus and leadership. Everyone “has” and nobody “owns;” there are no profiteers. Consequently, there is nothing to gain or work towards and without incentives, the ambition to succeed is rendered non-existent.

Le Guin’s novel is littered with stylistic prose. Written in a non-linear style, she plays with shifts of time, a technique used as a vehicle to drive her narrative forward. She transports her readers back into the past life of her protagonist Shevek by alternating chapters with his present life; a literary approach that may not appeal to everyone.

The opening chapter uses a clichéd plot device describing a symbolic wall between two planets which is central to the novel. This is aptly illustrated with the line “what was inside it and what was outside it depended upon which side of it you were on.” (4) The wall is being used as a symbol of global inequality that demonstrates the idiom “the haves and the have-nots.”

Le Guin is endeavoring to reveal how people will always demonstrate dissatisfaction with their lives and consider the other side of the wall to be more desirable. Her use of symbolism is intended to proposition the reader to consider their ideals. Questioning the reasoning behind hope for a perfect society explores whether the perfection of a collective civilization is ever realistic.

Contrasting Anarres with Urras

She contrasts the planet of Anarres with a parallel universe of capitalism on the planet Urras. This is an attempt at harmony and if it can be achieved through anarchistic principles. Her novel offers the possibility of freedom in a perfect civilization and she makes vain attempts to represent Anarres as an ideal society that exhibits deficiencies of capitalism.

Unfortunately, this interpretation is arguably flawed. Her narrative meanders somewhat, resulting in a portrayal of both societies exhibiting deficiencies. Neither planet displays an ideal civilization and it becomes unclear as to what the author is attempting to demonstrate.

Le Guin depicts Anarres as an ideal collective society with anarchistic principles but describes it as “grimy and mournful.” Her choice of the word “mournful” is significant as it contradicts any ideas of being ideal; instead, it suggests an unattractive place beset with misery.

In contrast, the planet Urras offers a capitalist regime which she portrays as an appealing land of “innumerable patches of green.” It is given further credibility through Shevek when he arrives on the planet Urras. Captivated by its beauty he reflects upon “how the world is supposed to look.” (5)

However, irrespective of the appeal of the lustrous landscape on Urras, there is a sense of overindulgence suggesting feigned enthusiasm. Problematically, Le Guin’s figurative language may be masking less attractive traits beneath its pleasing exterior which threatens to send out an unclear message.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Dispossessed on Bookshop.org* & Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Critic Tom Moylan writes in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction that Le Guin’s novel falls into the trap of endorsing a system of capitalism that it aims to condemn. (1) The result is a contradictory narrative that leaves Le Guin’s imagery unconvincing. It implies that confidence in the realization of a perfect society hasn’t been achieved on either planet. To realize confidence that inspires hope of a flawless society requires the narrative to overcome contradictions, which so far it fails to do.

Unfortunately, Le Guin’s attempts to offer greater confidence in making hopes and dreams of a better society appear conceivable, remain unpersuasive. The question of who has the authority to create, implement and control the rules in a free society remains under scrutiny “freedom is never very safe.”(6) Without effective leadership, the freedom of a collective society will crumble within a fractured civilization.

This further questions, if anyone would like to live in a society where its population was free of responsibility but their liberty was denied. Le Guin writes “would you really want to go and live in prison,” illustrating the lack of autonomy in a utopian society where people are unable to think independently of one another. (7) Le Guin’s narrative illustrates how free thought is something that is being denied suggesting that freedom and utopia cannot co-exist.

Utopias and their ideologies for a flawless existence date to the Renaissance period in 1516 with Thomas More’s Utopia written as a tale of social criticism. More says in his book that there were many things within the commonwealth of utopia he wished the country would imitate but lamented by saying, “though I don’t really expect it will.” (2)

More’s remark further supports the existence of historical aspirations that question hopes of a perfect society and the dreams for a better future. Writer Victor Urbanowicz claims in his science fiction article “Personal and political in The Dispossessed” that Le Guin had said that anarchism is “the most idealistic … the most interesting, of all political theories.”

He went on to say that Le Guin had also claimed the purpose of writing The Dispossessed was so she could embody it [anarchism] in a novel, that “had not been done before.” The claims of an anarchist utopian novel not being previously written are misguided. William Morris had written his novel titled News from Nowhere almost a century before Le Guin, in 1890. Both novels are remarkably similar, based on past revolutions that abandon capitalism and profit-orientated organizations. Both authors aim to provide an alternative to a capitalist command whilst attempting to fulfill the hopes of an ideal society.

Considering both novels with More’s highlights the significance of persistent efforts being made by authors writing comparable texts. This would suggest that aspirations to strive for a utopian society have been the hope of many throughout history. It poses the question of why the freedom that is envisaged through a utopian ideal still eludes society.

A utopian anarchist society raises optimism but it cannot be endured. It questions if anyone would desire a life of restriction. By presenting a contrasting environment to allow for an exploration of new ideas highlights social failings that are still prevalent today. Le Guin emphasized the cultural downfall of seeking a utopia that everyone would be happy with which confirmed the failure of the coexistence of freedom within a utopia.

Fantasy creates worlds that can originally explore social challenges and conventions but they need to offer a realistic possibility of achievement. Le Guin fails to offer this assurance in her narrative. As each generation evolves, they would only know the lackluster existence of a place such as Anarres.

Without experiencing the discourse and unrest that ‘can’ occur in a world like Urras, there is nothing to compare it with, and the potential for anarchy is likely to occur once again. To offer the dream or hope of a better future narratives need to be supported with strong characters who are living through real experiences.

If the possibility of realization isn’t attainable it will foster an ever-turning circle of disappointment. The result of Le Guin’s novel leaves a population with no ambition and little to motivate beyond a daily existence. Maybe Le Guin was telling us that it’s time to dispense with this idea of utopia.

Notes

1. Andrew Milner, “Tom Moylan” The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction ed by John Clute, David Langford, Peter Nicholls and Graham Sleight (London: Gollancz, updated 12 August 2018) [Accessed 29 August 2021].

2. Thomas More, ‘UTOPIA’, in Utopia (New Haven: Yale University Press 2017) pp. 1–2.

3. Ursula. K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed (London: Gollancz. SF Masterworks 2017) p 13.

4. Le Guin,p.11.

5. Le Guin, p.68.

6. Le Guin, p.354.

7. Le Guin, p.50.

8. Le Guin, p.12.

9. Victor Urbanowicz, ‘Personal and Political in “The Dispossessed”’, Science-fiction studies, 5(2), (1978) pp. 110–117.

Bibliography

Le Guin Ursula. K, The Dispossessed (London: Gollancz. SF Masterworks 2017)Milner Andrew, ‘Tom Moylan’ The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction ed by John Clute, David Langford, Peter Nicholls and Graham Sleight (London: Gollancz, updated 12 August 2018) http://www.sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/moylan_tom [Accessed 29 August 2021]More, Thomas, ‘UTOPIA’, in Utopia (New Haven: Yale University Press 2017)Morris William, Asa Briggs, and Graeme Shankland, News From Nowhere (London: Penguin Books, 1987)Urbanowicz, Victor ‘Personal and Political in “The Dispossessed”’, Science-fiction studies, 5(2), (1978)Contributed by Suzanne Bajor: Suzanne is a working-class writer in her third year of an English Literature and Creative Writing degree. Originally from Liverpool, she now lives in Greater Manchester. Writing has always been a hobby, but it wasn’t until she took early retirement in 2017 that Suzanne felt that she could develop her interest. She embarked upon a degree with the Open University and has just completed her level two with distinction (2021).

Since retiring, Suzanne has been actively submitting her work and has been shortlisted and published online with several of her short fictional pieces. When she is not writing and studying, Suzanne relaxes through her love of art and says drawing and painting allow her to switch off from outside distractions. This also helps her focus and develop ideas for her writing.

Developing techniques and learning how to write a substantial piece of work through her degree, has allowed Suzanne to gain confidence in sharing her work with others. Connect with Suzanne Bajor on Twitter.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post An Analysis of The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin (1974) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

September 2, 2021

Murder on the Orient Express by Agatha Christie (1934)

Agatha Christie (1890—1976) was the most widely published and best-selling author of all time. She authored sixty-six crime novels and short story collections, fourteen plays, and six other romance novels. Murder on the Orient Express, an intricate crime fiction novel, is one of Christie’s greatest mystery novels featuring the illustrious Belgian detective Hercule Poirot.

Murder on the Orient Express was first published in the United Kingdom in 1934, and soon after in the United States, retitled Murder on the Calais Coach. Christie drew inspiration for the plot from recent headlines.

Around the time when Murder on the Orient Express was published, the murder of Charles Lindbergh’s son had yet to be solved. This real-life mystery, coupled with Christie’s first journey on the Orient Express in 1928, inspired the iconic detective story.

Christie wrote Murder on the Orient Express in her room at the Pera Palace Hotel in Istanbul, Turkey, near the southern end of the Orient Express railway. As a memorial to the famed author, the hotel has continued to maintain Christie’s room.

A brief introductionHere’s a brief introduction to the book from the 1960 Dodd, Mead edition, by which time it was retitled Murder on the Orient Express to match the classic U.K. edition. Link here to a complete plot summary.

Thundering along on its three-day journey across Europe, the famous Orient Express suddenly came to a stop in the night. Snowdrifts blocked the line. Surrounded by the silent Balkan hills, the passengers slept unheeding.

But Hercule Poirot had not slept well. He awoke in the small hours, wondering at the silence and immobility of the train. He was startled by a loud groan which seemed to come from the next compartment. Footsteps sounded in the corridor, and there was a tap on a door.

Then someone said, It was nothing, a mistake. Poirot heard no more, and after a while dozed off uneasily. But in the morning the man in the next compartment lay dead — stabbed, viciously and frenziedly, over and over again. And since the snow outside was unbroken, the murderer was still on the train.

Thus begins one of the incomparable Christie’s most memorable suspense masterpieces — a mystery baffler considered by many connoisseurs to be her finest. Mistress of the surprise ending, the Queen of Crime” has never offered a more astonishing (and as always, completely logical) solution to a murder puzzle.

The basis of a record-breaking, all-star motion picture, Murder on the Orient Express continues to thrill audiences everywhere who agree that an intriguing mystery is the ultimate in entertainment.

. . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

Celebrating the Centenary of The Mysterious Affair at Styles

. . . . . . . . .

Considering that Murder on the Orient Express, as it came to be known, is one of Christie’s best-known Poirot novels, it received modest attention, and reviews, on both sides of the Atlantic. Here are two reviews from American newspapers from 1933, the year it was first published in the U.S.

Agatha Christie’s Latest Thriller

From The Baltimore Sun, November 2, 1933: “Agatha Christie’s latest thriller, The Murder in the Calais Coach, deals with the murder of a kidnapper on the Orient Express, the murder being done by twelve persons variously associated with the family of the child who had been kidnapped and murdered.

That Miss Christie and her famous French detective seem to accept this murder as an approximation of justice, and its provocation as reason enough for the detective to advance a fake solution to the authorities, makes it plain that this English authoress thinks that it would be bad form in a story for American readers to apprehend the avengers of a kidnapping.

And the participation of twelve murderers, being a sort of lethal approximation of the jury system, salves the conscience of an English writer opposed to lynch law.”

Agatha Christie Writes Another Poirot Thriller

From The Sacramento Bee, February 24, 1934: M. Hercule Pierot, the famous Belgian detective, finds himself confronted with the most puzzling crime of his long career when the body of an American is found stabbed to death in the sleeping coach of the Stamboul-Paris express. As the train has been stalled in a snowbank in the mountains of Yugoslavia, it has been impossible for the killer or killers to have escaped from the train.

Moreover, the murder is given a greater significance when it is discovered that the victim is a notorious kidnapper, head of a gang which has committed a crime as brutal as the Lindbergh baby case.

Thus does the curtain go up on the Murder in the Calais Coach. It becomes even more mystifying as the investigation proceeds. For everyone in the coach appears to have an air-tight alibi, and yet one or more of them must’ve done the killing.”

. . . . . . . . .

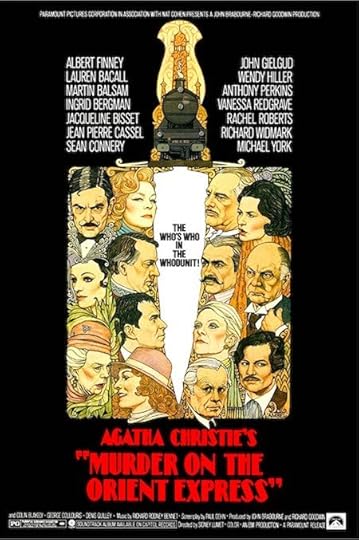

Film adaptations of Murder on the Orient Express

1974 Film Adaptation: The first adaptation of Christie’s novel, directed by Sidney Lumet, was released in 1974. A critical and audience hit, it starred Albert Finney as Poirot and Ingrid Bergman as Greta Ohlsson. Sean Connery and Lauren Bacall were featured as well. The film won nine Academy Awards, including Ingrid Bergman’s for Best Supporting. The film was financially successful as well, earning a total of $35 million at the box office.

The film earned an approval rating of 90% based on 39 reviews from Rotten Tomatoes, receiving an average rating of 7/10. The website’s critics consensus says that the “production of Murder on the Orient Express is one of the best Agatha Christie film adaptations to see the silver screen”.

Murder on the Orient Express was remade into a slightly altered version for TV in 2001, with Alfred Molina starring as Poirot. Agatha Christie, who died fourteen months after the 1974 film was released, said that this film was one of the only movie adaptations of her books that she liked.

. . . . . . . . .

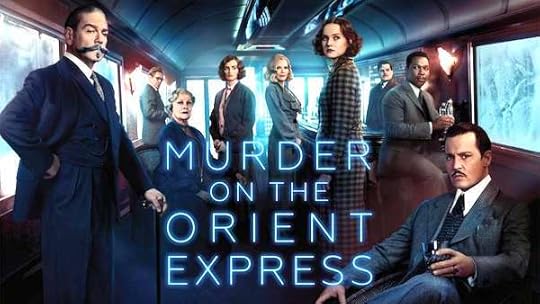

2017 Film Adaptation: The 20th Century Fox 2017 feature film version of Murder on the Orient Express was the fourth screen adaptation of Christie’s novel. Directed by Kenneth Branagh, he also starred as Poirot, with supporting cast members Penelope Cruz, Tom Bateman, and Johnny Depp.

The film was nominated for eighteen movie awards including several Critic’s Choice Awards and Teen Choice Awards and did quite well at the box office, earning a worldwide gross of $350 million. The film earned an approval rating of 60% based on 295 reviews from Rotten Tomatoes, receiving an average rating of 6/10.

You can stream the 1974 film*and the 2017 film on Amazon*.

A film adaptation of Death on the Nile, another Poirot mystery, is being positioned as a sequel to the 2017 film adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express, though it has a different (and diverse) all-star cast. The filming of Death on the Nile underwent several delays in production but is to be released on February 11, 2022. The new film is expected to spur an interest in Christie’s novel as well as other previous film adaptations.

Quotes from Murder on the Orient Express“The impossible could not have happened, therefore the impossible must be possible in spite of appearances.”

. . . . . . . . .

“The body—the cage—is everything of the most respectable—but through the bars, the wild animal looks out.”

. . . . . . . . .

“I like to see an angry Englishman,” said Poirot. “They are very amusing. The more emotional they feel the less command they have of language.”

. . . . . . . . .

“Because, you see, if the man were an invention—a fabrication—how much easier to make him disappear!”

. . . . . . . . .

“What’s wrong with my proposition?” Poirot rose. “If you will forgive me for being personal—I do not like your face.”

. . . . . . . . .

“I have learned to save myself useless emotion.”

. . . . . . . . .

“I believe, Messieurs, in loyalty—to one’s friends and one’s family and one’s caste.”

. . . . . . . . .

“The happiness of one man and one woman is the greatest thing in all the world.”

. . . . . . . . .

Agatha Christie books on Bookshop.org*

Agatha Christie page on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Murder on the Orient Express by Agatha Christie

Wikipedia Reader discussion on Goodreads Murder on the Orient Express: All the Versions and Their Differences The Home of Agatha Christie: Murder on the Orient Express. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Murder on the Orient Express by Agatha Christie (1934) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 30, 2021

Gone With the Wind’s Melanie Wilkes, and the Woman Who Portrayed Her

It’s a talented fiction writer who can make you believe that she has written your story. And what if you’ve been named for a fictional heroine because your father loved her character traits? Then, it’s almost an umbilical cordlike connection that stays with you throughout your life. This is how I came to be named Melanie, after the character of Melanie Wilkes from Gone With the Wind.

My father had read the book in engineering college, when I was nowhere in the picture. He tucked the name away in his head for future use. After my birth, as is wont in families, many suggestions for names came up from family members. The name Melanie encountered a bit of resistance, being a Christian name in an Indian home, but my father stood his ground.

He had loved what Melanie from Gone with the Wind stood for and hoped that the daughter named after her would in some way reflect her “qualities of charm and devotion.” He even wrote a letter to the British Council in the city that I was born in to check on the genus of the name, after verification with the Oxford Book of English Names. The British Council replied promptly enough, congratulating him and saying that since they didn’t have that book in their library, they were ordering a copy.

. . . . . . . . .

Olivia de Havilland as Melanie in the film adaptation of

Gone With the Wind, 1939

. . . . . . . . .

In Margaret Mitchell’s award-winning novel, Melanie is the quintessential good girl, compared to the feisty and spirited Scarlett O’Hara. They make a perfect foil for one another and become best friends, with Melanie rising to Scarlett’s defense when people spoke ill of her.

Melanie is full of admiration for Scarlett and tells her, “I’ve always admired you so. I wish I could be more like you.” Ironically, Melanie’s husband, Ashley realizes his wife’s true worth only when she is dying and says to Scarlett, “I can’t live without her. I can’t. Everything I ever had is going with her … She’s the only dream I ever had that didn’t die in the face of reality.”

In essence, that sums up what Melanie’s character stands for. She is compassion personified and steadfast in her convictions about what’s right. Despite being demure, she is able to display courage when the going gets tough, so much so that at various points in the novel, each of the characters turns to her in times of need, and she winds up playing a pivotal role in the story.

. . . . . . . . .

Olivia de Havilland

. . . . . . . . .

Here is how the difference between the characters of Melanie and Scarlett is summed up in the pages of Gone With the Wind:

“What Melanie did was no more than all Southern girls were taught to do: to make those about them feel at ease and pleased with themselves. It was this happy feminine conspiracy which made Southern society so pleasant. Women knew that a land in which men were contented, uncontradicted, and safe in possession of unpunctured vanity was likely to be a very pleasant place for women to live.

So from the cradle to the grave, women strove to make men pleased with themselves, and the satisfied men repaid lavishly with gallantry and adoration. In fact, men willingly gave the ladies everything in the world, except credit for having intelligence.

Scarlett exercised the same charms as Melanie but with a studied artistry and consummate skill. The difference between the two girls lay in the fact that Melanie spoke kind and flattering words from a desire to make people happy, if only temporarily, and Scarlett never did it except to further her own aims.”

Olivia de Havilland embodies Melanie

One cannot speak of Melanie without mentioning , who plays the role in the faithful 1939 film adaptation of Gone with the Wind. The role got so under her skin that she wrote a piece titled “To Parents, Who Name Their Daughter Melanie.”

When Selznick approached Olivia to play a part in Gone with the Wind, Warner Bros., with whom she had then been under contract, wouldn’t release her. She wangled it by inviting Warner’s wife to tea. Mrs. Warner was able to persuade her husband to loan her for the film.

Much to everyone’s surprise, Olivia insisted that she wanted to play Melanie in the movie, when every actress was vying to win the role of Scarlett O’Hara. She felt that she knew what it was to be a Scarlett but “Melanie had very deeply feminine qualities, which I felt were very endangered at that time and from generation to generation, and that somehow they should be kept alive. And one way I could contribute to that, was to play Melanie.”

By feminine qualities, de Havilland wasn’t referring just to physical attributes. She clarified by saying, “Melanie was other-people oriented. She was always thinking of the other person.”

For me, the most important observation that Olivia de Havilland made is: “The interesting thing to me is that Melanie was happy. Scarlett wasn’t a happy woman, all self-generated and preoccupied. But there’s Melanie, loving, compassionate. She had this marvelous capacity to relate to people with whom she would normally have no relationship.”

. . . . . . . . .

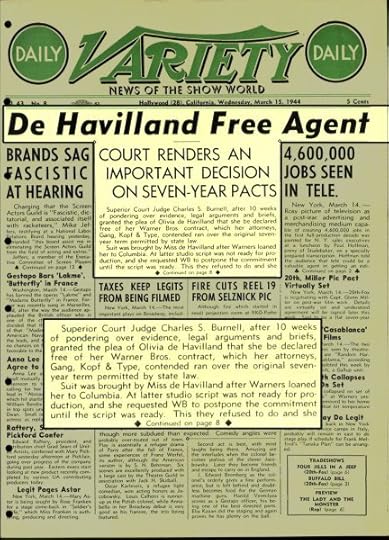

Variety (March 15, 1944)

. . . . . . . . .

In addition to being remembered as Melanie all of her acting life, Olivia needs to be acknowledged and thanked for the De Havilland Law, which was a victory for all the creative people of Hollywood.

When Olivia entered the film business, the studios enjoyed all the power, and signed actors up to work on long-term contracts involving six-day work weeks and long hours. If they refused to be loaned out to another studio or to play a particular role, they were liable for suspension without pay, with the length of the suspension extending the period of contract.

Under contract to Warner Bros., Olivia grew dissatisfied with the roles assigned to her and wished to break free. She longed to play a role like that of Melanie (for which she ultimately won an Oscar nomination) and knew she had an audience who would want to see her movies. “I had a responsibility to them,” she said in an interview.

In 1943, when her contract with Warner Bros. ended, the studio refused to release her, saying that she had to serve them for another six months to factor in a period of suspension. When Olivia decided to legally take on Warner Bros., she put a budding career on the line to fight an unjust system.

The courts ruled finally in favor of Olivia in a landmark judgement, which came to be known as the De Havilland Law, with one newspaper Variety boldly splashing the headline “de Havilland Free Agent.”

Olivia lived on till the age of 104 but fought this case at a young age. It’s hard to know where this courage came from and whether playing the role of Melanie had anything to do with it. Certainly, if I could have one wish as a way to live up to my name, it would be to do something as bold and brave as Olivia de Havilland, who epitomized the character of Melanie Wilkes.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy:

Gone With the Wind — Echoing Through the Ages

. . . . . . . . .

Melanie P. Kumar is a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

The post Gone With the Wind’s Melanie Wilkes, and the Woman Who Portrayed Her appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

August 25, 2021

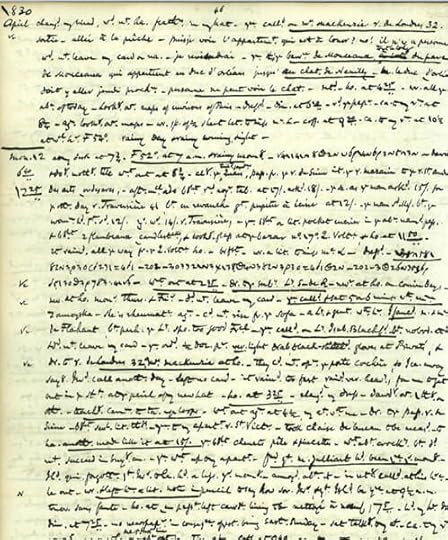

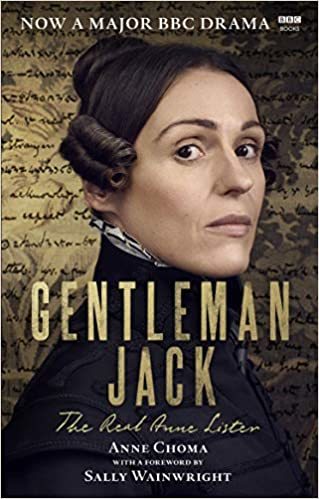

Glimpses into the Secret Diaries of Anne Lister (“Gentleman Jack”)

The fascinating and highly transgressive Englishwoman Anne Lister (1791 – 1840) of Shibden Hall in Yorkshire wasn’t a writer of published books, but was a committed diarist with a lot to write about. This introduction to the secret diaries of Anne Lister is excerpted from Killing the Angel: Early Transgressive British Woman Writers by Francis Booth ©2021, reprinted by permission.

Known in her local environs as “Gentleman Jack,” Lister’s enormous journals, only recently published, run to twenty six volumes and four million words – which possibly makes her in terms of word count one of the most prolific of woman writers in this book – but were never meant to be read by anyone.

These diaries, written primarily between 1817 and the mid-1820s, are partly in code to hide Lister’s lesbian sexuality. Once decoded, they are perfectly unambiguous, at least today.

I am resolved not to let my life pass without some private memorial that I may hereafter read, perhaps with a smile, when Time has frozen up the channel of those sentiments which flow so freely now. (19th February 1819)

I owe a good deal to this journal. By unburdening my mind on paper I feel, as it were, to get rid of it; it seems made over to a friend that hears it patiently, keeps it faithfully, and by never forgetting anything, is always ready to compare the past & present & thus to cheer & edify the future. (22nd June 1821)

Lister was born at an extraordinary time in history: her father served on the British side in the American War of Independence and was wounded at Lexington, returning unwilling to run the family business. But, as well as being the time of the American Revolution, this was the white heat of the British Industrial Revolution, which was led by the mills of Yorkshire.