Nava Atlas's Blog, page 39

June 8, 2021

Caresse Crosby, Patron of the Literary Lost Generation

Caresse Crosby (born Mary Phelps Jacob; April 20, 1892 – January 24, 1970) was known as a patron to the Lost Generation and other expatriate writers in Paris of the late 1920s. With her second husband, Harry Crosby, she founded Black Sun Press, publishing early works of writers who would have a lasting impact.

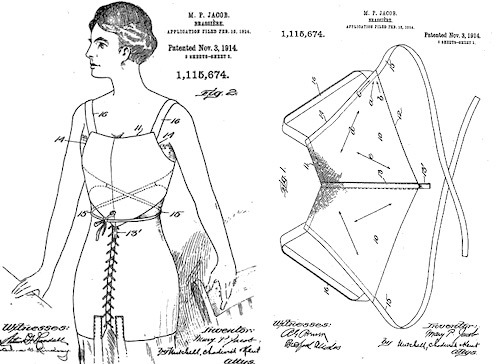

And in an offbeat yet impactful turn of events, in 1914, Crosby became the first person to receive a patent for the modern bra in 1914. The following appreciation of Crosby’s Paris years is excerpted from Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

Diarist and novelist Anaïs Nin on Caresse Crosby:

“Caresse Crosby enters with the buoyancy of a powder puff, caressing voice (was this how she gained the nickname of Caresse from Harry Crosby?), her fur hat, her eyelashes, her smile all glittery with animation. The word on her lips is always yes, and all her being says yes yes yes to all that is happening and all that is offered her. She trails behind her, like the plume of a peacock, a fabulous legend. She ran the Black Sun Press in Paris, lived in a converted windmill, knew D.H. Lawrence, Ezra Pound, André Breton, painters, writers. At the Quatre Arts Ball she once rode on a horse as Lady Godiva.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Harry Crosby in 1919

. . . . . . . . . .

Caresse’s husband Harry was the Harvard-educated nephew of J.P. Morgan. Together Caresse and Harry ran the Black Sun Press and were publishers, supporters and patrons of many young writers, including Kay Boyle, D.H. Lawrence, Hart Crane, Ernest Hemingway, Henry Miller, and Anaïs Nin; they published James Joyce’s Tales Told of Shem and Shaun and issued his Pomes Penyeach in a special edition, illustrated by James’ daughter Lucia.

As publishers and patrons they were magnificent, as writers less so, though it is hard to agree with Robert McAlmon when, with his usual sexist tone he describes Caresse as “an attractive, smartly-dressed woman but I did not take her literary interests or tastes seriously.”

The publishing house got its name because, as Caresse said, “black was Harry’s favorite color and he worshipped the sun.”

D.H. Lawrence

It was sun worship – in the atavistic sense not in the modern sense of sunbathing – that first led the Crosbys to D.H. Lawrence, an apostle of the sun himself. By 1929, Lawrence was looking for a publisher for Lady Chatterley’s Lover but without success; he was prepared to underwrite the costs himself but he was still having difficulty.

Lawrence was reluctant to leave his home in the warmth of the south of France in March, but decided he would have to go to Paris. While he was there the Crosbys invited him and Frieda to stay at their mill outside the city. Harry and Caresse had first seen and fallen in love with the mill, the scene of so many literary stories, while they were staying with the Duc de la Rochefoucauld in his château – being the nephew of J.P. Morgan assured Harry the best invitations.

Strolling around the vast estate they saw the old mill, semi-derelict but beautifully located. They immediately told the owner that they wanted to buy it; Harry did not have his check book on him so he ripped the cuff off the sleeve of Caresse’s white blouse and wrote him a check on that.

James Joyce

Caresse and Harry heard about James Joyce through his publisher Sylvia Beach, as did most people; they were just starting the Black Sun Press and they “yearned for a piece of the rich Irish cake then baking on the Paris fire.’

But when they first met him, “Joyce was uncommunicative and seemed bored with us, retreating behind those thick mysterious lenses until something was said about Sullivan’s concert the evening before, then suddenly he came to life – talking all the while about great Irish tenors.” Joyce was a tireless supporter of John Sullivan and the talk brought him to life. Harry and Caresse joined him in his enthusiasm, ostensibly anyway.

Joyce invited them back the next week for a concert and finally they worked up the courage to ask him if they could print some of what he was then calling Work in Progress, which eventually became part of Finnegan’s Wake. Joyce agreed, if only because they did not want many pages and they promised unlimited corrections – something Sylvia Beach had unwisely offered Joyce some years earlier. Caresse and Harry also agreed to pay Joyce whatever he asked for in advance; Joyce was always short of money.

The Crosbys began to visit Joyce regularly, when he gave them his ‘corrections and additions’. Harry noted in his diary “I liked the flash of triumph when Caresse asked him how much he enjoyed doing this new work, the same flash of triumph as when one is sleeping with a woman one loves, the same flash of triumph when one bets high on a horse and sees him gallop past the winning post a winner.”

Joyce signed a contract for the publication on April 3, 1929; the Crosbys paid him $1,000 as a half-payment. Joyce went through the proof sheets in mid-April, mostly at the Crosbys’ Paris apartment, but only after they had assured him that they would tie up and muzzle their dog Narcisse while he was there. He worked in their library which had a lamp with “an enormous lightbulb” in deference to the weakness of Joyce’s eyes. As he had been with Harry earlier, Joyce was always keen to show off his cleverness. Caresse wrote about this time in The Passionate Years:

“Now, Mr and Mrs Crosby,” Joyce said, “I wonder if you understand why I made that change?” All this in a blarney-Irish key.

“No, why?” We chorused, and there ensued one of the most intricate and erudite twenty minutes of explanation that it has ever been my luck to hear but unfortunately I hardly understood a word, his references were far too esoteric. Harry fared better, but afterward we both regretted that we did not have a dictaphone behind the lamp so that later we could have studied all that had escaped us. Joyce stayed three hours, he did not want to drink, and by eight he hadn’t got through with a page and a half. It was illuminating.

The Crosbys wanted to commission Picasso to do a portrait of Joyce for the book. Harry noted in his diary for May 3, 1929:

“C. spends the morning with Picasso I with Joyce. Picasso told her he wouldn’t do a portrait of Joyce because he never did portraits anymore but that sometime he would do a drawing for the Black Sun Press.”

Caresse asked the sculptor Brancusi for a drawing instead; he agreed and did several sketches. They were good likenesses but the Crosbys really wanted something more abstract. Brancusi agreed provided he was given complete freedom. The resulting “portrait” is just three vertical lines of various lengths and a spiral; not a literal portrait in any sense but the Crosbys and Joyce loved it, though Sylvia Beach thought it was “a bit too basic.”

When the book was finally ready for publication the printer had to come back to the Crosbys, very embarrassed, to tell them that the final page only had two lines; could Mr. Joyce perhaps provide an additional eight lines. Caresse was too frightened to ask him but the printer went behind her back directly to Joyce and got the lines; apparently Joyce had wanted to add more but was too frightened of Caresse to ask her.

. . . . . . . . .

[image error]

Everybody I Can Think of Ever on Amazon U.S.*

Everybody I Can Think of Ever on Amazon U.K*

. . . . . . . . .

Caresse first met Picasso’s friend and patron Gertrude Stein in 1928; they were not received warmly.

“To Gertrude Stein’s we went but once. I do not recall that Harry ever met her again. We were only three or four. She wanted to look at our editions and we wanted to look at her Picassos. We did both. Her portrait is well-known now, but then it had not yet met the public. The story goes that a friend complained to Picasso, ‘it doesn’t look like her.’ ‘It will,’ he replied.”

Harry and Caresse did meet Stein again, in the Midi in France in 1934 when it was Alice Toklas who was the ‘star’ of the luncheon. ‘She was in top form and led us through many a merry adventure, as she told us tales of her travels with Gertrude while Gertrude sat smiling upon us all like a happy Buddhess.’

The last time Caresse met Gertrude “I liked her best of all.” It was autumn 1945, in Paris, immediately after the war; Caresse was one of the first Americans to return. She had brought over drawings by American artists that she arranged to show in a gallery on the Rue Furstemburg.

“Paris was starving for contact with the American world of art and everyone flocked. Gertrude Stein came stalking in with her white poodle at her heels. She sat in the centre of the tiny room and almost stole the show, my show, but even when she walked off with the best-looking G.I. in the place, I forgave her. As Picasso had foreseen, his portrait now looks just like her.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

F. Scott FitzgeraldIn The Passionate Years, Caresse also tells a nice story of how she first met F. Scott Fitzgerald: she was passing through Baltimore on her way to the ship that would take her to Europe. She had never met him before but had been given his number and phoned him to introduce herself.

It went beautifully. He would wear a red carnation. He would meet me in the bar of the Lord Baltimore at twelve, he would take me to lunch, he would see that I reached the pier by two … I confidently entered the bar. It was 12:15 but no Scott – so I sat down and told the waiter I would order when the gentleman arrived – but no gentleman arrived.

Then someone who was no gentleman insisted on joining me. I got up flurried and went to the telephone. I had forgotten the number which I had had from a friend in New York. The operator could find no record of Scott Fitzgerald whatsoever. I was furious, and then I heard my name being paged. I was wanted on the telephone.

My barroom friend retreated. It was Scott full of apologies, he had been working he said, forgot the time etc. etc. Would I jump in a cab and come to the house. Did I like beer? I didn’t, but I answered, ‘Love it.’ If it hadn’t been for the barroom beau I’d have gone back and had a snifter myself.”

We drew up in front of a rather sinister-looking house, and as I remember, I had to go around to the back to get in. Scott answered the door in a flapping dressing-gown, hair tousled, but with a smile that unlatched my heart. “So you’re Caresse Crosby,” he said.

“And you are you.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Caresse Crosby’s patent. She was the first recipient of a patent for the modern bra,

patent number 1,115,674, granted on November 3, 1914, titled m. p. jacob–brassière:

. . . . . . . . . .

One of Caresse and Harry Crosby’s greatest successes as publishers came when they acted as midwives at the birth of one of the great American poems: they bullied, blackmailed and kidnapped Hart Crane into finishing his monumental poem sequence The Bridge – which, along with Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and William Carlos Williams’ Paterson, is one of the great pillars of American twentieth century epic poetry.

Crane and the Crosbys were introduced in Paris by Eugène Jolas, Joyce’s French translator, whom they had met though Sylvia Beach and who had also introduced them to Joyce. Jolas published Crane’s poems in transition, including some early parts of The Bridge; he called the Crosbys the “mad millionaires.”

They were certainly eccentric; among other things, they had dogs named Clytoris and Narcisse Noir. Crane describes his first meeting with them in a letter to Malcolm Cowley dated February 4, 1929.

“Have just returned from a weekend at Ermenonville (near Chantilly) on the estate of the Duc du Rochefoucauld where an amazing millionaire by the name of Harry Crosby has fixed up an old mill (with stables and a stockade all about) . . . I’m invited to return at any time for any period to finish The Bridge, but I’ve an idea that I shall soon wear off my novelty.”

Crane’s novelty did wear off, though not immediately. By the time the Crosbys met Crane they had already read what then existed of The Bridge. They were impressed. But the poem still needed some additions; the Crosbys decided to help Crane finish it, whatever the cost, personal and financial. It turned out to be a high price to pay.

While they were in New York and planning to force Crane to finish The Bridge, Harry and Caresse had been decorating their daughter Polleen’s room ready for when she came home from Swiss boarding school. She was due home on the Monday but on Saturday Harry brought Hart Crane home for the night. They had no guest room so had to put him up with his ‘sailor’s duffel bag and his hobnailed shoes’ in Polleen’s newly decorated room. Caresse describes that night in The Passionate Years:

“We were aware of Hart’s midnight prowlings and also aware, to our dismay, of his nocturnal pickups. He said he’d go out for a nightcap so it was with great relief that I heard him come in about 2 am and softly close the stairway door. Thereafter it was quiet. But in the morning, what a hideous awakening!”

Crane had completely wrecked Polleen’s room.

“On the wallpaper and across the pale pink spread, up and down the curtains and over the white chenille rug were the blackest footprints and handprints I have ever seen, hundreds of them. No wonder, for I heard to my fury that he had brought a chimney-sweep home for the night.”

At least it made a change from sailors, who were Crane’s preferred partners. Caresse forgave him and stuck with him through to the publication of The Bridge, going so far as to lock him in and forcing him to write. The tough love strategy worked and Crane finally finished the poem. On December 7, 1930 they held a party to mark the completion of The Bridge under the shadow of the actual bridge which it celebrates. Harry and Caresse were due to sail for France on the 13th. They never made it.

The demise of Harry Crosby

During the night of December 8, 1929 Harry Crosby suddenly told Caresse he wanted them both to leap from their hotel window and achieve a “Sun-Death” on this winter day. Caresse ignored him; he was drunk. It was six weeks after the Wall Street Crash and many financiers did in fact jump from tall buildings.

On the 10th Harry met his mistress, whom Caresse called the Fire Princess. He was supposed to meet Caresse later at the Lyceum Theatre, with Hart Crane and others. When there was no sign of Harry the party went into the theatre but Crane left his number at the box office in case a call came. It did. Crosby and his mistress were dead in a hotel room. They each had a bullet to the head and Harry still had a gun in his hand. Harry’s last entry in his diary was December 9:

And again my Invulnerability is put to the test.

One is not in love unless one desires

to die with one’s beloved

there is only one happiness

it is to love and to be loved

Caresse thought she was Harry’s beloved but she was obviously wrong. Their friends rallied around Caresse. Kay Boyle wrote to her on December 17, 1929 from Neuilly:

“dear darling child – I want to be near you and kiss you 1000 times and tell you how enormous how magnificent you are – I cannot say anything to you that is in my heart – but I see you like a fiery little steed and I worship you for it. Here is my devotion and my love and my homage forever and ever – your / Kay”

As if that weren’t enough for Caresse to bear, Hart Crane killed himself two years after Harry, on April 27, 1932, jumping from a boat on the way back to America from Havana.

After Harry’s and Hart Crane’s suicides Caresse Crosby continued her work and continued to meet new people. In her autobiography, The Passionate Years, she remembers meeting Ezra Pound for the first time; he had the same striking effect on her as on everyone else. It was in the early spring of 1930 and he had been living in Rapallo in Italy for some time. She had already had many letters from Pound ‘interlarded with his vivid designs and graphic flourishes’ but had not yet met him in person. Caresse found Pound interesting but socially awkward.

Anaïs Nin’s impressions

Anaïs Nin’s memories of first meeting Caresse, at a party at the surrealist painter Yves Tanguy’s house in the winter of 1939, with which we started this extract, continued:

“The life of certain women dresses them in anecdotes which become more visible than fur coats or silk dresses. Stories surround Caresse like a perfume, a necklace, a feather. She always seems fresher and younger than all the women there, because of her mobility, ease, flowingness. D.H. Lawrence would have called it her ‘livingness.’ A pollen carrier, I thought, as she mixed, stirred, brewed, concocted her friendships by a constant flux and reflux of activity, by curiosity, avidity, amorousness.”

In her journals for the winter of 1954/55, Nin is still in awe of Caresse Crosby:

“The dress is airy, winged. It is of black but transparent material, it is inflated and crisp by new chemistries, as organdy once was by starch and ironing. It gives her the silhouette of a young woman. Her hair, though grey, is glossy, and brushed and also starched and the opposite of limp, because the spirit in Caresse is airy and alive …

Age can wrinkle her face, freckle her hands, ruthlessly drop the eyelids over opened eyes, can tire her, but it cannot kill her laughter, her enthusiasm, her mobility.

Her second husband, Harry Crosby, committed suicide at the side of another woman (but Caresse had been invited first to share the suicide pact). Her adored son Bill died asphyxiated by a faulty gas heater in Paris. She lost two fortunes, but she wears at her neck a huge bow because dress and body and hair reflect the alertness and the discipline of her spirit.”

Nin had been sent to interview Caresse for the magazine Eve. She still thought Caresse was “an extraordinary woman.” Anaïs is obviously infatuated with Caresse, with her “lively and gay blue eyes, her constant sparkling laughter, a short humorous nose, a warm manner which wins everyone and a gift for making friends … She never commands, but whatever she asks is immediately accomplished.”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Caresse Crosby The Extraordinary Life of Caresse Crosby, Inventor of the Bra Phelps Family History in America Inventing the Bra was the Least Interesting Thing This Blue-Blooded Bohemian DidContributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

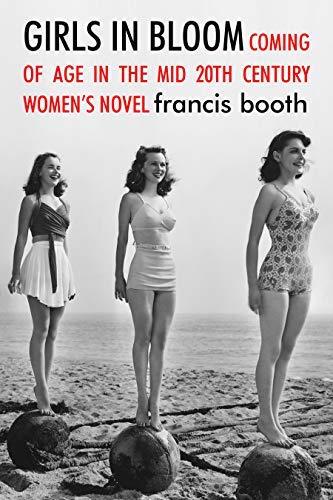

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Caresse Crosby, Patron of the Literary Lost Generation appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 5, 2021

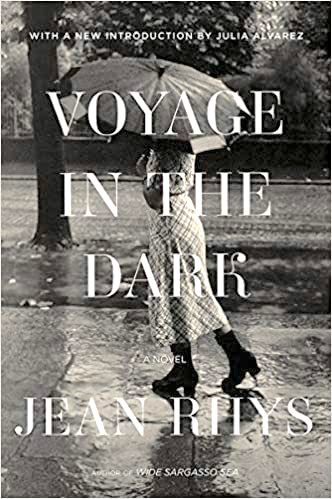

Voyage in the Dark by Jean Rhys (1934)

This review and analysis of Voyage in the Dark, a 1934 novel by Jean Rhys, is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

Jean Rhys (1890-1979) is best known for her novel Wide Sargasso Sea, a take on the Jane Eyre story from the point of view of the “madwoman in the attic,” Rochester’s wife, who, like Rhys, came from the Caribbean. It was finally published in book form in 1966 after years of tinkering and after a very long gap following her early novels, the first of which, Quartet, was published in 1928.

Voyage in the Dark doesn’t read at all like a pre-war novel. It feels far more like the British kitchen-sink novels and dramas of the late 1950s/early 1960s where amoral young women with either no parental influence or a very bad one float aimlessly through a world of seedy boarding houses and casual sex: A Taste of Honey by Shelagh Delaney (1958), The L-Shaped Room by Lynne Reid Banks (1960), which became the 1962 film, and Up the Junction by Nell Dunn (1962), which also became a film as well as a TV play.

Voyage in the Dark is to a large extent autobiographical, following an eighteen-year-old girl who has come to a cold, damp England from the warm, sunny Caribbean, as Rhys herself did.

Anna is no English rose; she has a totally opposite life experience to the upper-middle-class English girls of Rosamond Lehmann and her peers: she is traveling around England working as a showgirl, both in the sense of acting on the stage and in the pejorative sense the word had at the time of a “woman of easy virtue.”

Though by no means a prostitute, Anna certainly seems to be prepared to have relationships with men for money, as do all the women she knows, most of whom are older than her. One friend calls her “the Virgin,” though it is not absolutely clear whether at the start of the novel she is.

. . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

One of the men who gives her money believes she is a virgin but when she goes to his room she denies it; oddly, because virginity is presumably a very valuable commodity. “I’m not a virgin if that’s what’s worrying you,” she says. “You oughtn’t to tell lies about that,” the man replies. She denies that she is telling lies and says it does not matter anyway. The man replies: “Oh yes, it matters. It’s the only thing that matters.”

She tells him she wants to leave, but then she doesn’t. “When I got into bed there was warmth from him and I got close to him. Of course you’ve always known, always remembered, and then you forget so utterly, except that you’ve always known it. Always – how long is always?”

Anna is traveling and rooming with Maudie who is ten years older than her and highly cynical; hardly the ideal role model. She sees that Anna is reading Nana, Zola’s 1880 novel about an eighteen-year-old showgirl who becomes a highly successful prostitute, casually ruining all the men around her; Anna is of course an anagram of Nana. In its way, Nana is a coming of age novel, if an extremely dark one: “All of a sudden, in the good-natured child, the woman stood revealed, a disturbing woman with all the impulsive madness of her sex, opening the gates of the unknown world of desire.”

“That’s a dirty book, isn’t it?”

“Bits of it are all right,” I said.

Maudie said, “I know; it’s about a tart. I think it’s disgusting. I bet you a man writing a book about a tart tells a lot of lies one way and another. Besides, all books are like that – just somebody stuffing you up.”

In fact, apart from Nana and Alexandre Dumas’ Lady of the Camellias, most courtesan novels were written by women who actually were courtesans, such as Colette’s Chéri and Gigi, additions to the genre established by French nineteen century authors like Liane de Pougy, Céleste de Chabrillan and Valtesse de la Bigne.

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy …

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys

. . . . . . . . . .

Anna and Maudie always seem to be poor and always have trouble getting landladies to accommodate “professionals,” as one landlady calls them. Maudie encourages Anna; she is not entirely reluctant, has no qualms about accepting money from men, and is not even especially repulsed by the physical side of it.

“You shut the door and you pull the curtains over the windows and then it’s as long as a thousand years and yet so soon ended.” But Anna wonders when and how her life will change; how, even if, she will come of age as a woman, where she will end up; she has none of Nana’s or Dumas’ Marguerite Gautier’s single-minded drive to become rich through exploiting men and just seems to have fallen into this way of life.

“Of course, you get used to things, you get used to anything. It was as if I had always lived like that. Only sometimes, when I got back home and was undressing to go to bed, I would think, ‘my God, this is a funny way to live. My God, how did this happen?’”

‘But it isn’t always going to be like this, is it?’ I thought. ‘It would be too awful if it were always going to be like this. It isn’t possible. Something must happen to make it different’ and I thought, ‘yes, that’s all right. I’m poor and my clothes are cheap and perhaps it will always be like this. And that’s all right too.’ It was the first time in my life I’d thought that.

The ones without any money, the ones with beastly lives. Perhaps I’m going to be one of the ones with beastly lives. They swarm like woodlice when you push a stick into a woodlice-nest at home. And their faces are the colour of woodlice.”

In a way, Anna cannot wait to get old; when an older woman says to her that this is no way for a young girl to live, she thinks: “people say ‘young’ as though being young were a crime, and they are always scared of getting old. I thought, ‘I wish I were old and the whole damned thing were finished; that I shouldn’t get this depressed feeling for nothing at all.’”

But in Anna’s way of life, youth is the most valuable commodity, as a male acquaintance tells her in a letter informing her that Walter, one of the men who has been giving her money, and of whom she has become quite fond, cannot see her again; it is a rather standard Dear Jane letter, telling her she would be better off without him.

“I’m quite sure you are a nice girl and that you will be understanding about this. Walter is still very fond of you but he doesn’t love you like that anymore, and after all you must always have known that the thing could not go on forever and you must remember too that he is nearly 20 years older than you are. I’m sure that you are a nice girl and that you will think it over calmly and see that there is nothing to be tragic or unhappy or anything like that about.

You are young and youth as everybody says is the great thing, the greatest gift of all. The greatest gift, everybody says. And so it is. You got everything in front of you, lots of happiness. Think of that. Love is not everything – especially that sort of love – and the more people, especially girls, put it right out of their hands and do without it the better… Walter has asked me to enclose this cheque for £20 for your immediate expenses because he thinks you may be running short of cash. He will always be your friend and he wants to arrange that you should be provided for and not have to worry about money (for a time at any rate).”

In this demimonde everything has a price, though not necessarily a high price; life is cheap, and women are cheaper: £20 to buy off Anna must have seemed a reasonable amount, though at least one man “gave me fifteen quid” for a single experience.

Maudie tells Anna that a man said to her, “have you ever thought that a girl’s clothes cost more than the girl inside them?… You can get a very nice girl for five pounds, a very nice girl indeed; you can even get a very nice girl for nothing if you know how to go about it. But you can’t get a very nice costume for her for five pounds.”

Anna is not deeply upset about Walter and she has no hesitation in asking him for more money later when she needs an abortion, illegal and very dangerous in those days, and costing £50. But even this does not seem to make Anna want to change her way of life; everything in grey, miserable England seems like a bad dream to her anyway, even though the dream is interspersed with pleasant interludes.

“Sometimes not being able to get over the feeling that it was a dream. The light and the sky and the shadows and the houses and the people – all parts of the dream, all fitting in and all against me. But there were other times when a fine day, or music, or looking in the glass and thinking I was pretty, made me start again imagining that there was nothing I couldn’t do, nothing I couldn’t become. Imagining God knows what. Imagining Carl would say, ‘When I leave London, I’m going to take you with me.’ And imagining it although his eyes had that look – this is just for while I’m here, and I hope you get me.

‘I picked up a girl in London and she … Last night I slept with a girl who … ’ That was me.

Not ‘girl’ perhaps. Some other word, perhaps. Never mind.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Voyage in the Dark on Bookshop.org

Voyage in the Dark on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Voyage in the Dark by Jean Rhys (1934) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 4, 2021

The Literary Friendship of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings & Zora Neale Hurston

This musing on the friendship of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Zora Neale Hurston, two complex literary personalities, is excerpted and adapted from The Life She Wished to Live: A Biography of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Author of “The Yearling,” © 2021 Ann McCutchan. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

In the summer of 1942, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was invited to speak at historically black Florida Memorial College in St. Augustine. One of the instructors that term was Zora Neale Hurston. At the time, Zora was completing her memoir, Dust Tracks on a Road, covering her childhood in Eatonville, Florida’s first all-black incorporated city.

A budding friendship in a complicated era

Marjorie had just published Cross Creek, her memoir of the north-central Florida hamlet she had, fourteen years earlier, adopted as home. The two women became acquainted, and when Marjorie returned to Castle Warden, the St. Augustine hotel her husband, Norton Baskin, owned and operated, she told him she’d “met the most wonderful woman.”

In fact, she had immediately invited Zora to tea at their hotel apartment. But as soon she told Norton about it, she regretted the offer. She suggested she meet Zora elsewhere, not at the hotel, where white regulars might frown on a fashionably dressed black woman passing through the lobby and withdraw their business.

Marjorie’s concerns were real. Florida was an entrenched pocket of the Deep South; Jim Crow laws ruled. Lynchings still occurred, especially in the area between the Georgia-Florida line and north-central Florida, once home to plantations. There had been five plantations in Alachua County, 70 miles west of St. Augustine, where Cross Creek was tucked away.

Marjorie was herself ambivalent about black-white relations. Growing up in Washington, D.C., she had absorbed conventional racist attitudes and in 1928, when she bought a run-down Florida orange grove and moved there to write, she had hired several black workers to tend the grove and run her household. Some were lodged in a tenant shack behind her farmhouse. The maid who served Marjorie breakfast in bed wore a uniform and headpiece. “Mrs. Rawlings, kind as she was, never asked her workers to do anything,” Idella Parker, her longest-serving housekeeper, remembered. “She told them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

. . . . . . . . . .

Yet Marjorie paid higher wages than the going rate, covered her workers’ medical bills, and was considered liberal by her white Cracker neighbors. By the time she met Zora, she had won a Pulitzer Prize for The Yearling and begun moving in elite, highly educated white circles. She had been Eleanor Roosevelt’s guest at the White House. She was awakening to the twin causes of civil and human rights.

Norton, an Alabama native, assured Marjorie Zora was welcome and instructed a black assistant to watch for Zora at the appointed hour and “get her through this lobby the fastest you ever seen and get on the elevator, and get her up there.”

The hour came, but neither Norton nor his assistant saw anything of Zora. Marjorie’s guest had foreseen the situation, entered the hotel through the kitchen, and found her way to the Baskin apartment. When Norton checked with his wife on the hotel phone, she told him what Zora had done. “We’re having tea and having more fun than you’ve ever heard of,” she told him. “And if you’ve got any sense, you’ll come on up here.”

To a friend, Marjorie described Zora as “a lush, fine-looking café au lait woman with the most ingratiating personality, a brilliant mind, and the fundamental wisdom that shames most whites. She puts the full responsibility for Negro advancement on the Negroes themselves and has no use for the left-wingers who consider her a traitor, nor for the ‘advanced’ Negroes who belong to what she calls the fur-coat peerage.

“She says that both ‘advanced’ whites and ‘advanced’ negroes make a mistake in handling the Negro problem with kid gloves, each afraid of the other.”

What Zora told her squared with Carla Kaplan’s assertion that Zora “staked out a conservative position on race that grew from her fierce pride in black institutions and her suspicion of any mask unless it were her own.” Zora, from birth negotiating race, sex, and class to achieve artistry and serve ambition, wore many masks, and as friendly as she and Marjorie became, she modulated her behavior at first, observing the Southern code of manners, in which blacks adopted what Hilton Als has described as “theatrical modesty and duplicity” to manage their inferior position.

Marjorie might have found ease in the idea that the oppressed are responsible for their condition. Yet the meeting challenged her tendency toward what James Baldwin would call “the lie of pretended humanism.”

Marjorie’s ambivalence was apparent in “Black Shadows,” a chapter in Cross Creek, in which she highlighted several “reasonably accurate” clichés about Negroes: they were childlike, carefree, religious “in an amusing way,” liars, undependable. At the same time, she called these clichés superficial, pointing to the Negro population’s African heritage, the unspeakably difficult adjustments to slavery and, since Reconstruction, to “so-called civilization.” The Negro is “left to shift for himself for the most part instead of being cared for,” she wrote.

. . . . . . . . .

The Life She Wished to Live on Bookshop.org*

The Life She Wished to Live on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . .

After meeting Zora, Marjorie’s understanding of race relations began to shift significantly, though not without the interior conflicts, the steps forward, back, and sideways, that monumental change entails. That she had been urged to break custom by her Alabama-born husband led to the couple’s discussions about racial prejudice and Negro rights for many months to come.

Marjorie and Norton were not alone in this; their changing views corresponded with a pro-civil rights movement among educated whites as a whole, sparked by World War II. Nazism had forced some white Americans to own up to their racist policies and behaviors, while across the sea in the armed forces, men and women of many ethnicities served shoulder-to-shoulder, softening racial divisions.

As the United States emerged to lead the “free world,” it would have to embrace civil rights reform as bedrock — both as proper ideal, and as defense, for as the Cold War began, Soviet propagandists keen on locating the “free world’s” weaknesses, found an easy target in racism, particularly in the South.

. . . . . . . . .

Zora Neale Hurston

. . . . . . . . .

Early in 1943, Zora read Cross Creek and sent Marjorie an enthusiastic response. “Twenty-one guns!” she wrote. “It is a most remarkable piece of work. You turned your inside light on that community life, and it broke like day.

“Whether it pleases you or not, you are my sister. You look at plants and animals and people in the way I do. You are conscious of the three layers of life, instead of the obvious thing before your nose. You see and feel the immense past, what is now, and feel inside you something of what is to come. Therefore, you are not pacing the cell of the current hour. You are free, because you have made your peace with the universe, and its laws. You are deep and fine.”

“You did a thing I like in dealing with your Negro characters,” Zora continued, referencing “Black Shadows.”

“You looked at them and saw them as they are, instead of slobbering all over them as all of the other authors do. They talk real too, and act as I know them. You have done a remarkably able thing with the Negro idiom. It is so accurate. I am so sick and tired of that blackface minstrel patter that is put out as Negro dialect. I am not objecting to the bad grammar but the lack of imagination. You catch this thing as it is. You note the “picture talk” that’s something of a linguistic hieroglyphics. I am tickled to death with you, Sugar. I love your description of the women’s behinds. “Box” and “shingle” and they fit the thing so beautifully. You were thinking in hieroglyphics your ownself. You have written the best thing on Negroes of any white writer who has ever lived.”

By July, Norton Baskin was en route to India with the American Field Service. Soon afterward, Marjorie heard from Zora, whom she had written about trouble starting a new book, using it as an excuse to decline Zora’s invitation to take a river trip together. The truth was, Marjorie was embroiled in a lawsuit brought against her by a white neighbor who’d been offended by Marjorie’s depiction of her in Cross Creek. Marjorie was reluctant to travel openly with a black friend, as it might prejudice a critical segment of the public — such as white Crackers sitting on a jury — against her.

Zora replied with an enthusiastic desire to help. “How I wish that I were not doing a book too at this time! I would be so glad to come and take everything off your hands until you are through with yours …”

Deeply moved, Marjorie wrote to Norton, not knowing when or where he would receive the letter.

“The Negro writer, Zora Neal Hurston, has done one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever known,” she said, referring to Zora’s impulse. ”When she and I have finished our present books, I shall take the trip with her if it costs me the lawsuit and your business, not, God knows, in any spirit of condescension but with a desire to learn and to know.”

A surprise visitShortly before Christmas, Marjorie wrote Zora to confirm her Daytona Beach mailing address; she would ship her a holiday box of fruit. Again, she expressed frustration with her writing, and Zora immediately drove the one hundred miles from Daytona to the Creek to give Marjorie a boost. When Zora arrived, Marjorie was in Gainesville, Christmas shopping. Martha Mickens and her daughter Sissy, two of Marjorie’s black housekeepers, invited Zora to wait. Zora carried her bags to the women’s crowded tenant house.

For Norton, Marjorie described Zora’s surprise appearance:

“Well, I had the most mixed emotions. I was so touched by her doing it, as I was touched by her offer to do my housekeeping while I worked — and it was supper time, and it was nighttime and bedtime — and dat old debbil prejudice fair stuck a needle in me. I was ashamed, and I was worried, and I thought this would probably be the evening Mrs. Glisson [a white neighbor] would come up to ask me something, and the word would go out [that Marjorie had a Negro guest], and I would lose the lawsuit!”

But — “Damn it, now is the time for all good men to come to the aid of a moral principle!”

Zora’s bags were brought to the farmhouse guest room. The women would share the home as equals. “I was amazed to find that my own prejudices were so deep,” she admitted to her husband. “But I felt that if I ever was to prove my humanitarian and moral beliefs, even if it cost me the lawsuit, I must do it then.”

Grappling with prejudice

In spring 1944, Marjorie’s young friend Julia Scribner (the publisher’s daughter) visited Cross Creek; the two women asked Idella Parker to take them to a black church — an effort to step inside the black community, to understand it. The trio found “an old shack of a church” and Marjorie gave Idella three dollars for the pastor, with a request to hear some singing.

“It seemed awful to walk into someone’s church and buy their songs,” she wrote to Norton, though she wasn’t sorry to have played the cultural tourist — it was a start. A day or two later, Marjorie took Julia to a cocktail party in Ocala, drank too much, and when a guest made a racist remark, Marjorie held forth on “moral principles” until everyone except Julia turned against her. A friend told Marjorie, “You have never been hated in your life as you are hated here tonight.”

About this incident, Norton responded:

“… you will gain nothing by trying to convince the hidebound Southerner. Their beliefs on the question are firmly congealed and they are determined to keep them intact … Trying to argue the question with them merely increases their hate of the movement and plants the idea that the problem is getting out of hand and something has to be done.”

And that something, Norton suggested, was more violence against the Negroes.

Now Marjorie was reading Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, a comprehensive analysis of the racial divide, which might have influenced, in April, her advice to Idella about income taxes. Idella wanted to pay hers, but Marjorie asserted no one would catch her if she didn’t.

A tax-paying citizen should have the right to vote, Marjorie said, along with all other privileges; she was well aware that the fifteenth amendment, passed nearly 75 years before, was routinely circumvented in the South, through white primaries, poll taxes, literacy tests, long residency requirements, and other obstacles. She was upset that blacks were drafted in wartime: “You can’t force men into military service for their country, without giving them the same rights as anyone else,” she wrote Norton.

But it was one thing for Marjorie to take a stand on paper or at a party, another to continue wrestling with personal prejudice, revealed in her own language and behavior. A few days later, Marjorie admitted to Norton her revulsion to black skin. “I still have to fight a lingering prejudice, and when little black Martha [Sissy’s daughter] touches me, as she loves to do, I cringe. But if one recognizes it for a prejudice and a hang-over from one’s prejudiced training, it will pass.”

Norton came home that fall. Marjorie began publicly addressing the racial divide. At historically black Florida A & M College in Tallahassee, she was the principal speaker for a two-day celebration honoring black educator/activist Mary McLeod Bethune. Marjorie’s address, “A Floridian’s View of Mary McLeod Bethune” is lost to history, but, she wrote to a friend, “It was a fascinating experience and I am more than ever ashamed of the people who try to hold the Negroes back.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Yearling

. . . . . . . . . . .

Still, Marjorie’s position was fraught with contradictions. In the post-war era, The Yearling had been called out for offensive language, primarily a few uses of the “n” word. In January 1946, the book was withdrawn from required reading at the predominantly black Morris High School in the Bronx, after irate citizens deemed it a “poison” book for its portrayal of Negroes.

Members of the National Equal Rights League protested The Yearling’s spot on a summer reading list for James Monroe High School, also in the Bronx, with the same objections. Upset, Marjorie wrote to the Rev. Frank Glenn White, director of the People’s Institute of Applied Religion, which espoused social activism and equal rights in particular, and to People’s Voice, addressing her use of the “n” word in The Yearling. The newspaper published part of her letter, introducing her as someone considered “a staunch supporter of Negroes.” She wrote:

“I approve with all my heart the policy of laying a taboo on the use of the word, not because any word is in itself offensive, since all words are only their connotations, but because those who use the word in ordinary speech or casually in print are those who have the wrong attitude, not only toward Negroes, but toward all of life and Christian living.

But in your zeal, you must not see things out of proportion. This is one cause of my weeping for the Negro race, for it is inevitable that intelligent Negroes are likely to be psychologically touchy. As you know, this is not solely a Negro characteristic. Probably ninety-nine out of the hundred human beings, anywhere and everywhere, have been conditioned by circumstances to be touchy about something.

Now it is a great deal to ask of Negroes who have borne up so nobly under inconceivable injustices, not to be unduly touchy. Yet it seems to me extremely important that your race rise to difficult heights and prove itself above trivialities.”

Marjorie pointed out that The Yearling’s time period, 1870-71, called for the “n” word.“It would have been an unpardonable anachronism to have used the word ‘Negro” instead, in a book of this date.” This was the stronger argument; evidently, she could not hear the condescension in her chief message: “don’t be so touchy.” That message echoed Zora’s attitude; It’s possible that in 1946, Marjorie was taking cues from the friend who first galvanized her.

In May, the lawsuit trial occurred, with public support going to Marjorie. (The saga would drag out two more years behind closed doors, ending in a kind of stalemate.) Marjorie was pleased when she heard Zora had written to a friend:

“I could have saved all kinds of trouble if she [Marjorie] had just plain let me kill that poor white trash” who initiated the lawsuit. “If you hear of the tramp getting a heavy load of rock salt and fat-back in her rump, and I happen to be in Fla at the time, you will know who loaded the shell…”

Later years

The few extant letters between Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Zora Neale Hurston fall away after the trial. In 1947, Zora moved to Honduras for research, and Marjorie bought a new writing retreat in Van Hornesville, New York. She continued arguing for civil rights. In 1948, Scribners published Zora’s last novel, Seraph on the Suwanee, dedicated to Mary Holland, wife of Florida’s former governor and U.S. Senator Spessard Holland, and Marjorie. (All of Zora’s books were dedicated to white friends and patrons.)

“I am praying that this book will have a big sale so that I can return the sum you so generously loaned me,” Zora wrote Marjorie, indicating her tenuous financial state. That year, she had been arrested in New York and charged with molesting a ten-year-old boy; the charge was dropped after she proved she had been in Honduras. Marjorie was struggling in other ways; ill health, complicated by alcoholism, hampered progress on her last novel. She died in 1953, a year following The Sojourner’s publication.

After Marjorie’s death, Zora wrote to Mary Holland. “I am deprived of the warmth of the association, and … I feel that I failed her in her last extremity.” Marjorie had told Zora she was ill, but by then, Zora couldn’t have come to Marjorie’s aid. She had no car. “I could not bear to admit it to her,” Zora confided, “lest she feel sorry for me.”

Contributed by Ann McCutchan. Ann is the author of six books of memoir, essay, and biography. The founding director of the University of Wyoming Creative Writing MFA program, she was also a professor of creative writing at the University of North Texas and editor of American Literary Review. Awards and fellowships have come from the Rockefeller Foundation, Cornell University, the MacDowell Colony, and others. For more information, visit AnnMcCutchan.com.

More literary friendships George Eliot & Harriet Beecher Stowe Virginia Woolf & Vita Sackville-West Lillian Hellman & Dorothy Parker

. . . . . . . . . .

*This post contains Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post The Literary Friendship of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings & Zora Neale Hurston appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

June 3, 2021

May Sinclair, British Novelist, Philosopher, and Suffragist

May Sinclair, (born Mary Amelia St. Clair Sinclair; August 24, 1863 – November 14, 1946) was a British novelist, philosopher, poet, and suffragist who was regarded as England’s “leading woman novelist between the death of George Eliot and the rise of Virginia Woolf,” according to David Williams, a critic who wrote for Punch.

She explored the inner lives of ordinary women in some twenty-three novels, while also publishing two works of philosophy, a biography of the Brontës, several collections of poetry, and dozens of short stories.

May Sinclair is largely forgotten today. All of her works had fallen out of print when Virago Press, the noted British feminist publishing house, reissued three of her most significant novels in the early 1980s. At present, however, only The Life and Death of Harriett Frean (1922), which many regard as her masterpiece, is in print.

She combined an interest in philosophical idealism and Freud and was an early adherent of modernism, which rejected traditional narrative structures. She was the first critic to use the term “stream of consciousness” to describe a narrative technique, and the first British writer to champion the work of T.S. Eliot.

Her 1919 novel, Mary Olivier: A Life, employed second-person narration and took numerous risks, including an attempt to portray the world through the eyes of an infant, as it traced the protagonist’s struggle to achieve spiritual and intellectual independence.

Early life and education

May Sinclair was the youngest of six children and the only surviving daughter. Her father, William Sinclair, was an alcoholic who died in 1881. Sinclair’s mother, Amelia Sinclair, was rigidly and intolerantly Christian. May Sinclair described her as exerting a “cold, bitter, narrow tyranny” over her household.

While Sinclair was able to pursue only one year of formal education at Cheltenham Ladies College, while she was there she won the attention of the noted educator Dorothy Beale, who encouraged her to pursue philosophy. Sinclair left college to care for her ailing brothers and mother.

While Sinclair published her first novel in 1897, it wasn’t until the death of her mother, in 1901, that her writing took off. Her 1904 novel, The Divine Fire, was a best-seller in both the U.K. and the United States. She went on to publish numerous novels that examined the ways in which women’s lives were constricted by social expectations, marriage, patriarchy, and repression.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A suffragist and modernistThe Divine Fire was so successful that Sinclair embarked on a book tour of the eastern United States. In the course of her travels, she met literary figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Mark Twain, and Sarah Orne Jewett. Back in London, she became active in the Women’s Freedom League, and met and befriended figures such as Thomas Hardy, with whom she undertook a bicycling trip, as well as Ezra Pound and H.D.

In 1912 she published a 48-page pamphlet, Feminism, in which she argued on behalf of women’s suffrage and economic equality. At around this time, she also began writing for The Egoist, considered England’s most important modernist periodical for its publication of Imagist poetry and early excerpts of James Joyce’s Ulysses. She also became interested in the works of Sigmund Freud — as were many of the modernists — and Carl Jung. She also became a major financial supporter of the Medico-Psychological Clinic, the first training program in psychoanalysis in Britain.

Sinclair became fascinated by the Brontë sisters and wrote introductions to new editions of their work as well as a critical examination of her own, The Three Brontës. She also produced a novel inspired by their lives, The Three Sisters. When the latter was reissued in 1985, Publisher’s Weekly said that Sinclair “brings to this novel psychological acuity reminiscent of D.H. Lawrence, as well as remarkable skill as raconteur.”

Her fascination with the Brontës led in turn to an interest in the macabre, and thus to the ghost stories that comprised her 1910 collection, Uncanny Stories.

The Great War

When World War I began, Sinclair went to Belgium out of a desire to be helpful. While some sources say she returned home because there wasn’t much for her to do, others claim that she was overwhelmed by what she saw and left the field for that reason. Whatever her reason for returning to England, her Journal of Impressions in Belgium was one of the first accounts of the war written by a British woman.

Stream of consciousness

It was in 1918, while reviewing Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrim series for The Egoist, that Sinclair applied the term “stream of consciousness” to Richardson’s technique of describing the inner life of her protagonist Miriam Henderson.

Apparently influenced by Richardson, Sinclair wrote Mary Olivier: A Life, a coming-of-age novel that is believed to be semi-autobiographical, and which has been described as “a portrait of the artist as a young (wo)man,” appearing as it did at the same time that James Joyce and Virginia Woolf were employing the stream of consciousness technique in their work.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Falling into obscurityDespite her impressive output and significant contributions, Sinclair is little known today. According to critic Joanna Kavenna, in her review of Suzanne Raitt’s May Sinclair: A Modern Victorian (2001), Sinclair’s personality did not endear her to the modernists or the Bloomsbury crowd, though she worked among them.

While she had thoroughly rejected her mother’s rigid Christianity to become a confirmed agnostic, she was neat and hard-working. Older than many of the Modernists, she was dismissed as “prim” by Virginia Woolf and did not encourage intimate friendships. To employ some of Sinclair’s own techniques of psychological inquiry, these characteristics might have resulted from the tyranny of her mother and the alcoholism of her father, combined with the tragic loss of several brothers to early death.

Further, while Sinclair lived until 1946, she suffered from Parkinson’s disease for nearly two decades before her death and lost touch with her public as well as with her former friends and colleagues. Much like the protagonist of The Life and Death of Harriet Frean, she died in obscurity and isolation, with only the company of her companion and housekeeper, Florence Bartrop.

Fast cars and a love of the road

Yet Sinclair was very much a living woman, even in the final years of her life. The discovery of a Rolls Royce that she purchased around 1935 revealed her love of cars and driving. She bought her first car in 1919, and often urged her chauffeur, Ernest Williams, to drive faster and overtake other cars on the road. She, Bartrop, and Williams took several long road trips through Britain in the 1930s.

. . . . . . . . . .

May Sinclair in 1921

. . . . . . . . . .

While all of Sinclair’s work, except for Harriet Frean, has fallen out of print, much of her work, including her war essays, her biography of the Brontës, some of her short stories, and most of her novels are available on Project Gutenberg.

The May Sinclair Society was founded in July 2013. The society is in the process of bringing Sinclair’s work back into print through the Edinburgh Critical Editions of the Works of May Sinclair.

The Society will host its third international conference, Networking May Sinclair on June 24–25, 2021 via Zoom. Registration for the online conference is free; for more information and to reserve go to Networking May Sinclair.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, she has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.org.

More about May SinclairMore information and sources

List of Works Poetry Foundation Yale Modernism Lab May Sinclair Society – Sinclair Trivia May Sinclair: Readable ModernistRead and Listen Online

Project Gutenberg LibrivoxThe post May Sinclair, British Novelist, Philosopher, and Suffragist appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 31, 2021

Maureen Daly’s Seventeenth Summer and the Birth of the Teenage Novel

Maureen Daly (1921 – 2006) was an Irish-Born American author and journalist, best known for the novel Seventeenth Summer (1942). Though twenty-one at the time of its publication, she wrote it while in her teens. Originally intended it for adult readers, it drew an enthusiastic audience of teens, and as such, is considered one of the early entries into the genre of Young Adult fiction. This appreciation of Seventeenth Summer is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

The rise of the teenager in the 1940s was accompanied by the rise of the teenage novel: novels written for and about – and even by – teenage girls. The 1940s and 50s saw several series of books by female authors about girls in their “seventeenth summer,” intended to be read by girls of around that age or younger; the exact demographic for the Sub-Deb columns in teen magazines and Betty Cornell’s advice columns.

But unlike the Sub-Debs, these “practically seventeens” are generally not obsessed with their looks, their school peer group, their figure, or with dating boys; the girls in these novels are mostly bookish and shy – like, presumably, the girls who read them – though they often have more glamorous and more extroverted older sisters.

And, unlike the central characters in the more literary novels intended for adults that we are considering, the girls in these books usually have normal, loving, middle-class, middle-American parents, with whom they tend not to have angst-ridden, existential conflicts. The father is usually employed in a respectable job and the mother stays at home cooking and baking and so tends to be slightly overweight and homely, giving her daughters a comfortable shoulder to cry on.

Starting with “Fifteen” and “Sixteen”

One of the earliest examples of this genre was the short story “Sixteen” by Maureen Daly – later the editor of the Ladies’ Home Journal’s Sub-Deb column – which won first prize in a short story competition in 1938 when Daly was herself sixteen and still at school; the previous year she had entered a story called “Fifteen” and won third prize.

The narration foreshadows the knowing, conspiratorial tone of many of the subsequent novels about sixteen-year-old girls, many of which were influenced by it. The unnamed narrator is confident, modern, and independent; like some of her successors (and of course Cinderella), she has two older sisters as better or worse role models.

“Now don’t get me wrong. I mean, I want you to understand from the beginning that I’m not so really dumb. I know what a girl should do and what she shouldn’t. I get around. I read. I listen to the radio. And I have two older sisters. So, you see, I know what the score is … I’m not exactly small-town either. I read Winchell’s column.

You get to know what New York boy is that way about some pineapple Princess on the West Coast and what Paradise pretty is currently the prettiest. It gives you that cosmopolitan feeling. And I know that anyone who orders a strawberry sundae in a drugstore instead of a lemon Coke would probably be dumb enough to wear colored ankle-socks with high-heeled pumps or use Evening in Paris with a tweed suit. But I’m sort of drifting. This isn’t what I wanted to tell you. I just wanted to give you that the general idea of how I’m not so dumb. It’s important that you understand that.”

The narrator is ice-skating when a boy comes up and says, “Mind if I skate with you?” She agrees. “That’s all there was to it. Just that and then we were skating. It wasn’t that I’d never skated with a boy before. Don’t be silly. I told you before, I get around. But this was different. He was a big shot at school and he went to all the big dances and he was the best dancer in town.”

Afterward, walking home in the snow they talk, softly, “as if every little word were secret… A very respectable Emily Post sort of conversation and then finally – how nice I looked with snow in my hair and had I ever seen the moon so close?” As he leaves her at her door the boy says he will call her.

“And that was last Thursday. Tonight is Tuesday. Tonight is Tuesday and my homework is done and I darned some stockings that didn’t really need it, and worked a crossword puzzle, and I listened to the radio and now I’m just sitting. I’m sitting because I can’t think of anything, anything but snowflakes and ice skates and the yellow moon and Thursday night. The telephone is sitting on the corner table with its old black face turned to the wall so I can’t see its leer. I don’t even jump when it rings any more. My heart still prays but my mind just laughs …

And so I’m just sitting here and I’m not feeling anything. I’m not even sad because all of a sudden I know. All of a sudden I know. I can sit here now for ever and laugh and laugh and laugh while the tears run salty in the corners of my mouth. For all of a sudden I know. I know what the stars knew all the time – he’ll never never call – never.”

As a sixteen-year-old herself, Daly fully understands and beautifully communicates this life-altering tragedy in a way that no adult novelist could.

. . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom by Francis Booth on Amazon*

Girls in Bloom on Amazon UK*

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

One of the earliest full-length teen girl books of the 1940s, and arguably the first Young Adult novel, is Daly’s first novel, Seventeenth Summer. Since the category did not exist at that time it was issued as an adult novel, though Maureen Daly herself was still – just – a teenager, and still at college when she finished writing it.

It continues the theme of the short story ‘Sixteen’ and foreshadows many of the features of the later books aimed at teenage girls by Rosamond du Jardin and others, with its almost-seventeen narrator whose world consists entirely of her family – conventional middle-class father, mother, and three sisters – her school and her first boyfriend; the novel covers just the summer of their relationship.

It opens rather like Daly’s earlier “Sixteen”: ‘I don’t know just why am telling you all this. Maybe you think I’m being silly. But I’m not, really, because this is important. You see, it was different!’

Of course, it is only important within Angie’s small world and only different compared her previously very limited experience. She says to her date, Jack, “I just want to read a lot and learn everything I can,” but she is just trying to impress him. In return, he says he wants to go to an opera wearing a cape and white gloves, “I don’t know much about music,” he says. “I don’t even like it a lot but I could learn.”

Commentary on social class

But Jack’s family is socially one step down from Angie’s and she notices the difference even if he doesn’t. Her mother notices too. “It isn’t that my mother doesn’t like boys, as I explained, but because we are girls and because we are the kind of family who always uses top sheets on the beds and always eat our supper in the dining room and things like that – well, she just didn’t want us to go out with anybody.” Her mother probably reads Ladies Home Journal.

This social difference is put under the microscope the first time Jack comes for dinner. Angie’s older sister Lorraine shows off her knowledge of literature, deliberately – at least in Angie’s mind – to expose Jack; she asks him if he has read various books.

Jack looked at her in her embarrassment and his lips were awkward with his words. “I don’t read much,” he confessed and my heart slipped down a little “I don’t read at all as much as I’d like to,” he went on, “but, gee, with school and everything …” He looked at her in apology and then at me, adding feebly, ‘“ play a lot of basketball and things …”

Angie defends him, but only in her mind, she does not speak up in his defense. Her sisters do not realize, she thinks, that “he could dance to any kind of music at all, fast or slow, and that any girl in town would be glad to wear his basketball sweater even for one night.” But the disastrous meal is soon made even worse by Jack’s eating habits and even Angie starts to look down on him.

“In our house where we had never been allowed to eat untidily, even when we sat in highchairs! It all seemed so suddenly and sickeningly clear – I could just see his father in shirtsleeves, piling food onto his knife and never using napkins except where there was company. And probably they brought the coffee pot right in and set it on the table.

My whole mind was filled with a growing disdain and loathing. His family probably didn’t even own a butter knife! No girl has to stand for that. Never. If a boy gets red in the face, sputters salad dressing on the tablecloth, and hasn’t even read a single book to talk about when you ask him over for dinner, you don’t have to be nice to him – even if he has kissed you and said things to you that no one has ever said before!”

Maureen Daly became a journalist after leaving college – she graduated in English and Latin – working as a reporter and book reviewer on the Chicago Tribune and Saturday Evening Post as well as at one point editing the Sub-Deb column at the Ladies’ Home Journal. But, despite the success of Seventeenth Summer, which sold over a million copies, and was reissued in 2002, Daly wrote no more novels until the mid-1980s.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Seventeenth Summer on Bookshop.org*

Seventeenth Summer on Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Maureen Daly

Wikipedia New York Times Obituary Celebrating Maureen Daly in Fond du Lac. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*These are Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

The post Maureen Daly’s Seventeenth Summer and the Birth of the Teenage Novel appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

May 30, 2021

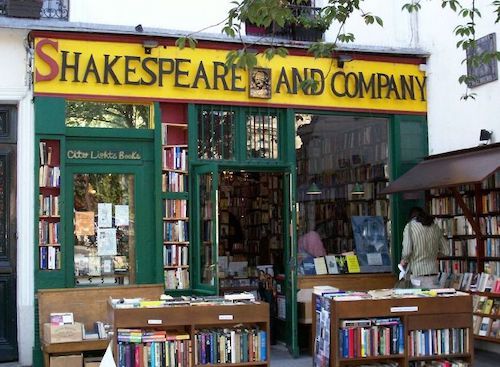

Sylvia Beach: Legendary Paris Bookseller and Publisher

Sylvia Beach (1887 – 1962) was the legendary owner of the legendary bookshop Shakespeare and Company the meeting place for all of literary Paris in the 1920s, and the publisher of James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922. This musing on her active years in literary Paris is excerpted from Everybody I Can Think Of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

Beach wrote her own résumé towards the end of her life in a letter dated April 23, 1951, to the American Library in post-war Paris, when she donated the remaining books from Shakespeare and Company to them.

“I am the daughter of the late Rev. Sylvester Woodbridge Beach who was pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Princeton, New Jersey:

Opened an American bookshop-lending library on the left bank, Paris in 1919 – called Shakespeare and Company: which was rather famous as a result of writers. Some of those who were connected with it from the beginning and as you might say grew up with it, were Robert McAlmon, Ernest Hemingway, Thornton Wilder, Scott Fitzgerald, Archibald McLeish, Kay Boyle – to name only a few: their elders were Sherwood Anderson, Gertrude Stein, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Ezra Pound.

Shakespeare and Company brought out James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922, which had been suppressed in the United States, Ireland, and England.”

Beach’s partner, Adrienne Monnier, had her own, French-language, bookshop across the street, La Société des Amis du Livre [The Society of Friends of the Book]. Monnier published her own French-language literary magazine Le Navire d’Argent [The Silver Ship] and published the French translation of Ulysses. It was not just writers who haunted Sylvia’s bookshop: the American composer Virgil Thomson ‘often loafed at Sylvia Beach’s shop, where I had the privilege of borrowing books free;’ Thomson contrasts the two women in his autobiography.

“If angular Sylvia, in her boxlike suits, was Alice in Wonderland at forty, pink and white, buxom Adrienne in her grey-blue uniform, bodiced, with peplum and a long full skirt, was a French milkmaid from the 18th-century.”

Adrienne Monnier

Adrienne had her bookshop on the Rue d l’Odéon first; that was where she met Sylvia, who had moved from New Jersey to Paris via Spain in 1917.

Beach had found a reference in the National Library to a volume of verse by Paul Fort and was told the book could be purchased at A. Monnier’s bookshop at Rue d l’Odéon. She did not know the district but set out across the Seine to find it. As soon as she entered the street it reminded her of the colonial houses in Princeton, where she had grown up.

She peered in through the shop window, excitedly looking at the “shelves containing volumes in the glistening ‘crystal paper’ overcoats that French books wear while waiting, often for a long time, to be taken to the binders,” In her autobiography, Shakespeare and Company, Beach described their first meeting.

“At a table sat a young woman. A. Monnier herself, no doubt. As I hesitated at the door, she got up quickly and opened it, and, drawing me into the shop, greeted me with much warmth. This was surprising in France, where people are as a rule reserved with strangers, but I learned that it was characteristic of Adrienne Monnier, particularly if the strangers were Americans.

I was disguised in a Spanish cloak and hat, but Adrienne knew at once that I was American. ‘I like America very much,’ she said. I replied that I liked France very much. And, as our future collaboration proved, we meant it.”

. . . . . . . . .

[image error]

Everybody I Can Think of Ever on Amazon U.S.*

Everybody I Can Think of Ever on Amazon U.K*

. . . . . . . . .

Beach was still standing by the open door when the wind blew her hat into the middle of the street. Adrienne rushed after it, “going very fast for a person in such a long skirt. She pounced on it just as it was about to be run over, and, after brushing it off carefully, handed it to me. Then we both burst out laughing.”

Sylvia describes Adrienne at that time as “stoutish, her coloring fair, almost like a Scandinavian’s, her cheeks pink, her hair straight and brushed back from her fine forehead. Most striking were her eyes. They were blue-grey and slightly bulging, and reminded me of William Blake’s. She looked extremely alive.” They started to talk about books, immediately became friends and later lovers, a partnership that lasted until Adrienne’s death and survived Sylvia opening her own bookshop across the street.

Another New Jersey native, the poet William Carlos Williams first met Adrienne when he visited Shakespeare and Company in 1924 while on a trip to Paris with his wife; he found her “extremely cordial.”

“Adrienne Monnier, a woman completely unlike Sylvia, very French, very solid, whose earthy appetites, from what she told us, made her seem to stand up to her very knees in heavy loam, came in from across the street to make our acquaintance. Somehow we got to talking of Breughel, whose grotesque work she loved – the fish swallowing a fish that itself was swallowing another.

She enjoyed the thought, she said, of pigs screaming as they were being slaughtered, contempt for the animal – a woman toward whom it was strange to see the mannishly dressed Sylvia so violently drawn. Adrienne gave no quarter to any man.

Once, when Bob [McAlmon] in a taxi had taken her in his arms and kissed her, she sunk her teeth into his lips so that he expected to have a piece torn out before she released him. A woman, however, of unflinching kindness.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Gertrude SteinOne of Shakespeare and Company’s earliest visitors was art collector and avant-garde writer Gertrude Stein. In The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, speaking in her partner Alice’s voice, she describes how they first encountered it.

“Someone told us, I have forgotten whom, that an American woman had started a lending library of English books in our quarter. We had in those days of economy given up Mudie’s, but there was the American Library which supplied us a little, but Gertrude Stein wanted more. We investigated and we found Sylvia Beech [sic]. Sylvia Beech was very enthusiastic about Gertrude Stein and they became friends. She was Sylvia Beech’s first annual subscriber and Sylvia Beech was proportionately proud and grateful.”

But Sylvia wasn’t always so hospitable or so welcoming to strangers, preferring to protect the people she already knew. One writer who got Sylvia’s cold shoulder was Morley Callaghan, a Canadian writer who had been a reporter with Ernest Hemingway in Toronto.

He had gone to Paris knowing Hemingway was there but not knowing how to contact him. He knew of Shakespeare and Company and Sylvia Beach. In That Summer in Paris Callaghan tells the story of how he went there, hoping she would put the two writers in touch again. She didn’t.

“Approaching the desk, I introduced myself and wondered if she could give me Hemingway’s address. Without batting an eyelash, she told me she wasn’t sure whether Hemingway was in town, nor if he were, whether she would be able to locate him before she heard from him. But if I would leave my own address she would make an effort to see that it was passed on.”

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

James Joyce and UlyssesCallaghan suspected Beach was not going to pass his details to Hemingway and he was right. She was so protective of her flock that one day, when James Joyce was in the back of the shop, the Irish writer George Moore appeared, looking for him. She told him she didn’t know where Joyce was. Joyce was very upset; he had never met Moore and very much wanted to.

Beach remembers, in Shakespeare and Company, her first meeting with Joyce in the summer of 1920, when her bookshop was in its first year; Beach had had A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in the window of her shop not long before and she loved Joyce’s writing. They met at the apartment of a poet friend, André Spire, at 34, Rue du Bois de Boulogne. Joyce had not been invited or expected but her host whispered to her: “The Irish writer James Joyce is here.”

“I worshipped James Joyce, and on hearing the unexpected news that he was present, I was so frightened I wanted to run away, but Spire told me it was the Pounds who had brought the Joyces – we could see Ezra through the open door. I knew the Pounds, so I went in.”

Before the formal meal Sylvia talked to the wives of Ezra Pound – Dorothy Shakespear – and Joyce – Nora Barnacle – but not to the great man himself; Spire sat them all down for supper before she had a chance to meet him. Afterwards she went into “a little room lined to the ceiling with books.”

“Trembling, I asked: ‘is this the great James Joyce?’

‘James Joyce,’ he replied.

We shook hands; that is, he put his limp, boneless hand in my tough little paw – if you can call that a handshake.